a237b71ecd0b8f2bbd8f2ded326ea7d4.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 36

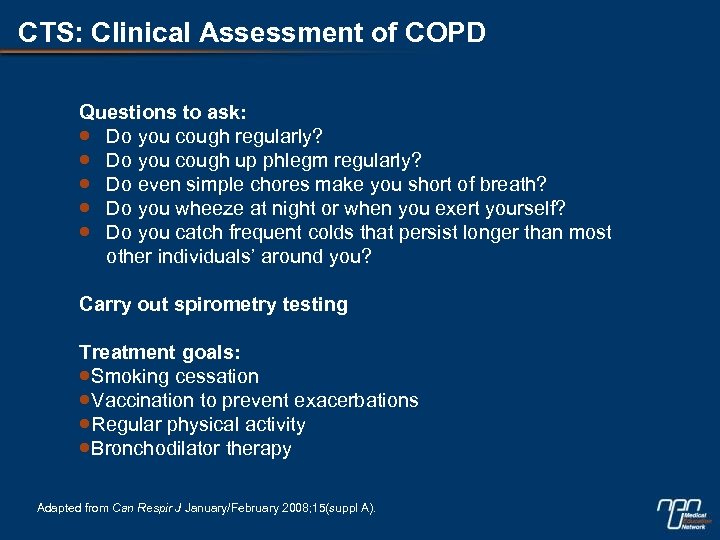

CTS: Clinical Assessment of COPD Questions to ask: Do you cough regularly? Do you cough up phlegm regularly? Do even simple chores make you short of breath? Do you wheeze at night or when you exert yourself? Do you catch frequent colds that persist longer than most other individuals’ around you? Carry out spirometry testing Treatment goals: Smoking cessation Vaccination to prevent exacerbations Regular physical activity Bronchodilator therapy Adapted from Can Respir J January/February 2008; 15(suppl A).

CTS: Clinical Assessment of COPD Questions to ask: Do you cough regularly? Do you cough up phlegm regularly? Do even simple chores make you short of breath? Do you wheeze at night or when you exert yourself? Do you catch frequent colds that persist longer than most other individuals’ around you? Carry out spirometry testing Treatment goals: Smoking cessation Vaccination to prevent exacerbations Regular physical activity Bronchodilator therapy Adapted from Can Respir J January/February 2008; 15(suppl A).

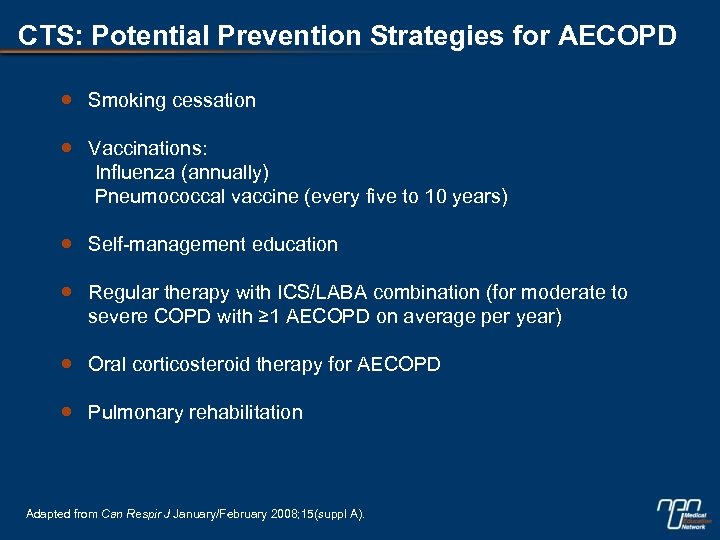

CTS: Potential Prevention Strategies for AECOPD Smoking cessation Vaccinations: Influenza (annually) Pneumococcal vaccine (every five to 10 years) Self-management education Regular therapy with ICS/LABA combination (for moderate to severe COPD with ≥ 1 AECOPD on average per year) Oral corticosteroid therapy for AECOPD Pulmonary rehabilitation Adapted from Can Respir J January/February 2008; 15(suppl A).

CTS: Potential Prevention Strategies for AECOPD Smoking cessation Vaccinations: Influenza (annually) Pneumococcal vaccine (every five to 10 years) Self-management education Regular therapy with ICS/LABA combination (for moderate to severe COPD with ≥ 1 AECOPD on average per year) Oral corticosteroid therapy for AECOPD Pulmonary rehabilitation Adapted from Can Respir J January/February 2008; 15(suppl A).

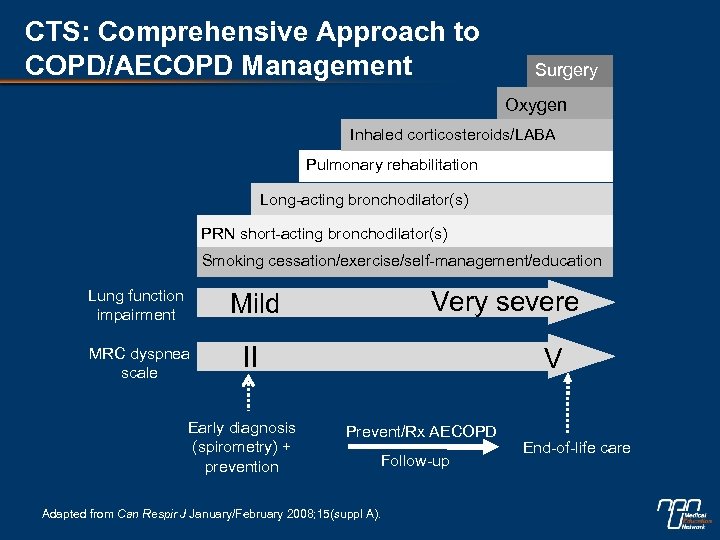

CTS: Comprehensive Approach to COPD/AECOPD Management Surgery Oxygen Inhaled corticosteroids/LABA Pulmonary rehabilitation Long-acting bronchodilator(s) PRN short-acting bronchodilator(s) Smoking cessation/exercise/self-management/education Lung function impairment Very severe Mild MRC dyspnea scale II Early diagnosis (spirometry) + prevention V Prevent/Rx AECOPD Follow-up Adapted from Can Respir J January/February 2008; 15(suppl A). End-of-life care

CTS: Comprehensive Approach to COPD/AECOPD Management Surgery Oxygen Inhaled corticosteroids/LABA Pulmonary rehabilitation Long-acting bronchodilator(s) PRN short-acting bronchodilator(s) Smoking cessation/exercise/self-management/education Lung function impairment Very severe Mild MRC dyspnea scale II Early diagnosis (spirometry) + prevention V Prevent/Rx AECOPD Follow-up Adapted from Can Respir J January/February 2008; 15(suppl A). End-of-life care

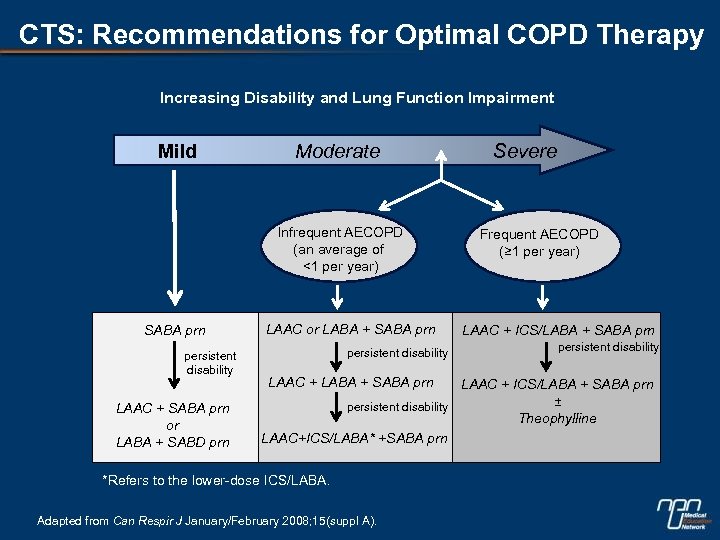

CTS: Recommendations for Optimal COPD Therapy Increasing Disability and Lung Function Impairment Mild Moderate Infrequent AECOPD (an average of <1 per year) SABA prn persistent disability LAAC + SABA prn or LABA + SABD prn LAAC or LABA + SABA prn persistent disability LAAC + LABA + SABA prn Severe Frequent AECOPD (≥ 1 per year) LAAC + ICS/LABA + SABA prn persistent disability LAAC + ICS/LABA + SABA prn ± persistent disability Theophylline LAAC+ICS/LABA* +SABA prn *Refers to the lower-dose ICS/LABA. Adapted from Can Respir J January/February 2008; 15(suppl A).

CTS: Recommendations for Optimal COPD Therapy Increasing Disability and Lung Function Impairment Mild Moderate Infrequent AECOPD (an average of <1 per year) SABA prn persistent disability LAAC + SABA prn or LABA + SABD prn LAAC or LABA + SABA prn persistent disability LAAC + LABA + SABA prn Severe Frequent AECOPD (≥ 1 per year) LAAC + ICS/LABA + SABA prn persistent disability LAAC + ICS/LABA + SABA prn ± persistent disability Theophylline LAAC+ICS/LABA* +SABA prn *Refers to the lower-dose ICS/LABA. Adapted from Can Respir J January/February 2008; 15(suppl A).

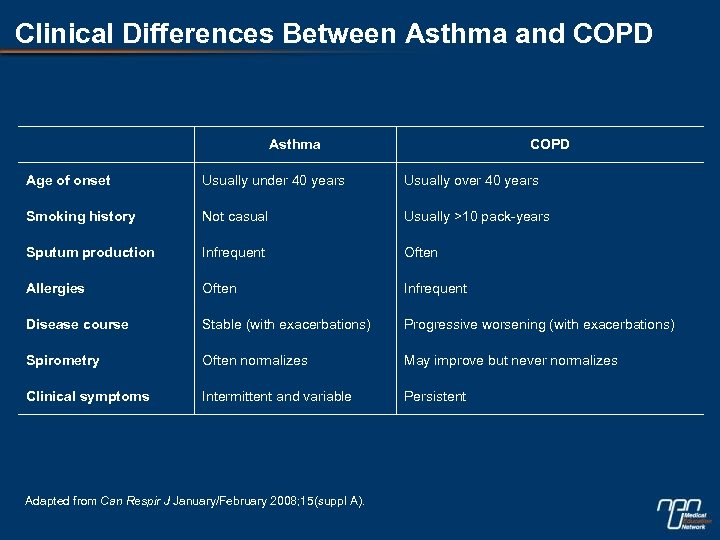

Clinical Differences Between Asthma and COPD Asthma COPD Age of onset Usually under 40 years Usually over 40 years Smoking history Not casual Usually >10 pack-years Sputum production Infrequent Often Allergies Often Infrequent Disease course Stable (with exacerbations) Progressive worsening (with exacerbations) Spirometry Often normalizes May improve but never normalizes Clinical symptoms Intermittent and variable Persistent Adapted from Can Respir J January/February 2008; 15(suppl A).

Clinical Differences Between Asthma and COPD Asthma COPD Age of onset Usually under 40 years Usually over 40 years Smoking history Not casual Usually >10 pack-years Sputum production Infrequent Often Allergies Often Infrequent Disease course Stable (with exacerbations) Progressive worsening (with exacerbations) Spirometry Often normalizes May improve but never normalizes Clinical symptoms Intermittent and variable Persistent Adapted from Can Respir J January/February 2008; 15(suppl A).

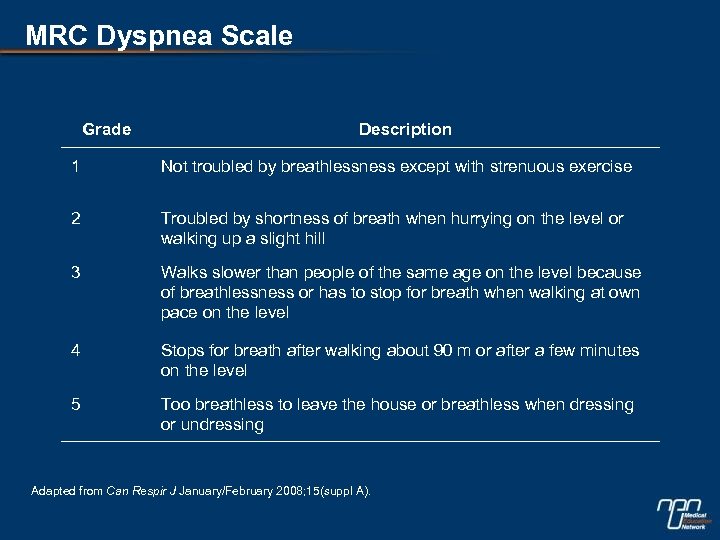

MRC Dyspnea Scale Grade Description 1 Not troubled by breathlessness except with strenuous exercise 2 Troubled by shortness of breath when hurrying on the level or walking up a slight hill 3 Walks slower than people of the same age on the level because of breathlessness or has to stop for breath when walking at own pace on the level 4 Stops for breath after walking about 90 m or after a few minutes on the level 5 Too breathless to leave the house or breathless when dressing or undressing Adapted from Can Respir J January/February 2008; 15(suppl A).

MRC Dyspnea Scale Grade Description 1 Not troubled by breathlessness except with strenuous exercise 2 Troubled by shortness of breath when hurrying on the level or walking up a slight hill 3 Walks slower than people of the same age on the level because of breathlessness or has to stop for breath when walking at own pace on the level 4 Stops for breath after walking about 90 m or after a few minutes on the level 5 Too breathless to leave the house or breathless when dressing or undressing Adapted from Can Respir J January/February 2008; 15(suppl A).

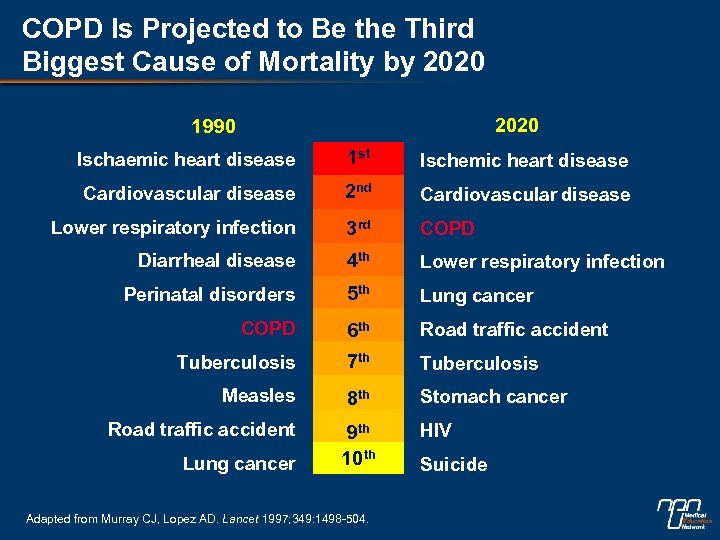

COPD Is Projected to Be the Third Biggest Cause of Mortality by 2020 1990 Ischaemic heart disease 1 st Ischemic heart disease Cardiovascular disease 2 nd Cardiovascular disease Lower respiratory infection 3 rd COPD Diarrheal disease 4 th Lower respiratory infection Perinatal disorders 5 th Lung cancer COPD 6 th Road traffic accident Tuberculosis 7 th Tuberculosis Measles 8 th Stomach cancer Road traffic accident 9 th 10 th HIV Lung cancer Adapted from Murray CJ, Lopez AD. Lancet 1997; 349: 1498 -504. Suicide

COPD Is Projected to Be the Third Biggest Cause of Mortality by 2020 1990 Ischaemic heart disease 1 st Ischemic heart disease Cardiovascular disease 2 nd Cardiovascular disease Lower respiratory infection 3 rd COPD Diarrheal disease 4 th Lower respiratory infection Perinatal disorders 5 th Lung cancer COPD 6 th Road traffic accident Tuberculosis 7 th Tuberculosis Measles 8 th Stomach cancer Road traffic accident 9 th 10 th HIV Lung cancer Adapted from Murray CJ, Lopez AD. Lancet 1997; 349: 1498 -504. Suicide

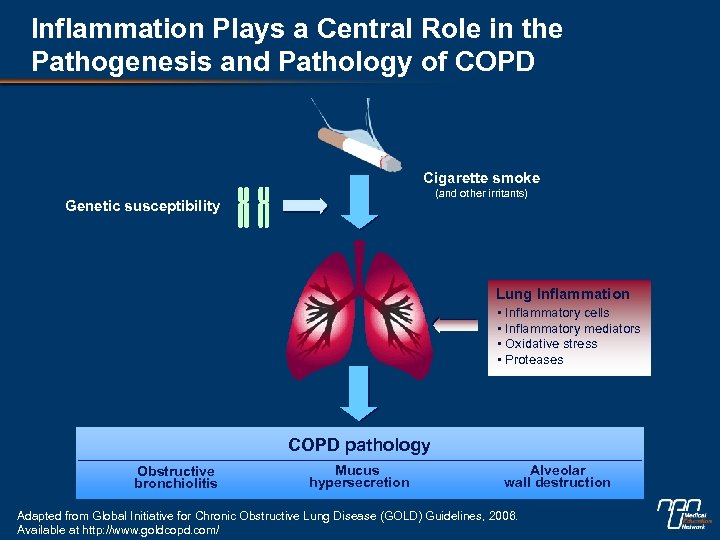

Inflammation Plays a Central Role in the Pathogenesis and Pathology of COPD Cigarette smoke (and other irritants) Genetic susceptibility Lung Inflammation • Inflammatory cells • Inflammatory mediators • Oxidative stress • Proteases COPD pathology Obstructive bronchiolitis Mucus hypersecretion Alveolar wall destruction Adapted from Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) Guidelines, 2006. Available at http: //www. goldcopd. com/

Inflammation Plays a Central Role in the Pathogenesis and Pathology of COPD Cigarette smoke (and other irritants) Genetic susceptibility Lung Inflammation • Inflammatory cells • Inflammatory mediators • Oxidative stress • Proteases COPD pathology Obstructive bronchiolitis Mucus hypersecretion Alveolar wall destruction Adapted from Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) Guidelines, 2006. Available at http: //www. goldcopd. com/

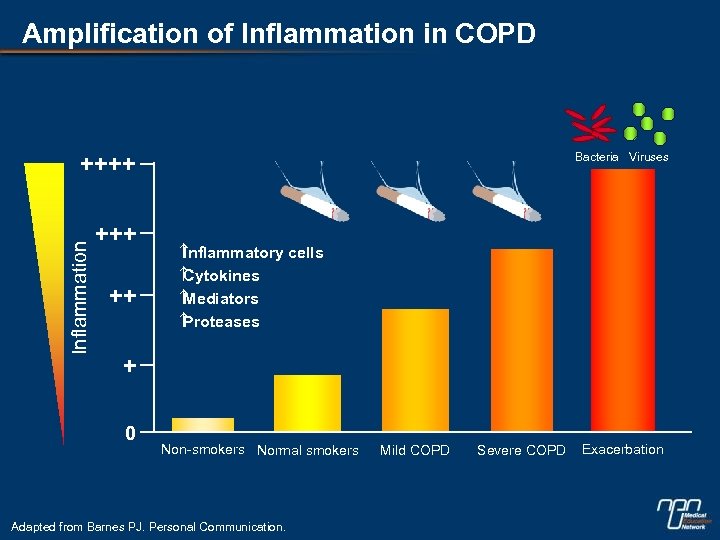

Amplification of Inflammation in COPD Bacteria Viruses Inflammation ++++ ++ Inflammatory cells Cytokines Mediators Proteases + 0 Non-smokers Normal smokers Adapted from Barnes PJ. Personal Communication. Mild COPD Severe COPD Exacerbation

Amplification of Inflammation in COPD Bacteria Viruses Inflammation ++++ ++ Inflammatory cells Cytokines Mediators Proteases + 0 Non-smokers Normal smokers Adapted from Barnes PJ. Personal Communication. Mild COPD Severe COPD Exacerbation

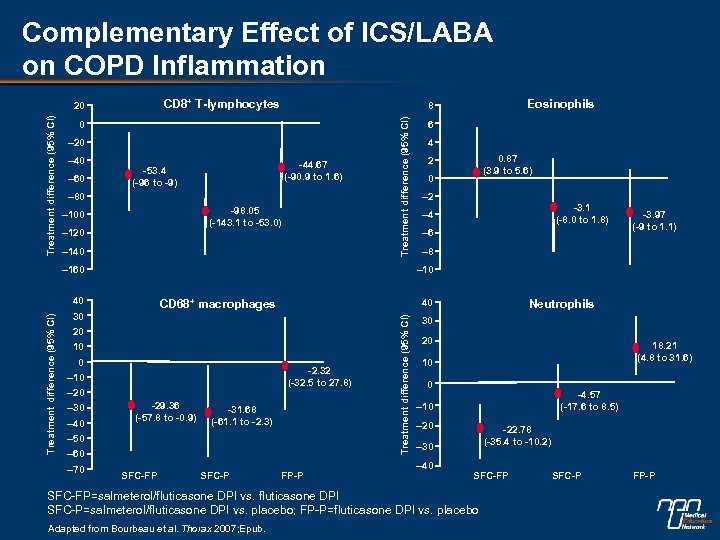

Complementary Effect of ICS/LABA on COPD Inflammation CD 8+ T-lymphocytes 0 – 20 – 40 – 60 -44. 67 (-90. 9 to 1. 6) -53. 4 (-96 to -9) – 80 -98. 05 (-143. 1 to -53. 0) – 100 – 120 – 140 – 160 20 10 0 -2. 32 (-32. 5 to 27. 8) – 10 – 20 -29. 36 (-57. 8 to -0. 9) -31. 68 (-61. 1 to -2. 3) – 50 – 60 – 70 4 0. 87 (3. 9 to 5. 6) 2 0 – 2 -3. 1 (-8. 0 to 1. 8) – 4 – 6 -3. 97 (-9 to 1. 1) – 8 SFC-FP SFC-P Neutrophils 40 FP-P Treatment difference (95% CI) CD 68+ macrophages 30 – 40 6 – 10 40 – 30 Eosinophils 8 Treatment difference (95% CI) 20 30 20 18. 21 (4. 8 to 31. 6) 10 0 -4. 57 (-17. 6 to 8. 5) – 10 – 20 -22. 78 (-35. 4 to -10. 2) – 30 – 40 SFC-FP=salmeterol/fluticasone DPI vs. fluticasone DPI SFC-P=salmeterol/fluticasone DPI vs. placebo; FP-P=fluticasone DPI vs. placebo Adapted from Bourbeau et al. Thorax 2007; Epub. SFC-P FP-P

Complementary Effect of ICS/LABA on COPD Inflammation CD 8+ T-lymphocytes 0 – 20 – 40 – 60 -44. 67 (-90. 9 to 1. 6) -53. 4 (-96 to -9) – 80 -98. 05 (-143. 1 to -53. 0) – 100 – 120 – 140 – 160 20 10 0 -2. 32 (-32. 5 to 27. 8) – 10 – 20 -29. 36 (-57. 8 to -0. 9) -31. 68 (-61. 1 to -2. 3) – 50 – 60 – 70 4 0. 87 (3. 9 to 5. 6) 2 0 – 2 -3. 1 (-8. 0 to 1. 8) – 4 – 6 -3. 97 (-9 to 1. 1) – 8 SFC-FP SFC-P Neutrophils 40 FP-P Treatment difference (95% CI) CD 68+ macrophages 30 – 40 6 – 10 40 – 30 Eosinophils 8 Treatment difference (95% CI) 20 30 20 18. 21 (4. 8 to 31. 6) 10 0 -4. 57 (-17. 6 to 8. 5) – 10 – 20 -22. 78 (-35. 4 to -10. 2) – 30 – 40 SFC-FP=salmeterol/fluticasone DPI vs. fluticasone DPI SFC-P=salmeterol/fluticasone DPI vs. placebo; FP-P=fluticasone DPI vs. placebo Adapted from Bourbeau et al. Thorax 2007; Epub. SFC-P FP-P

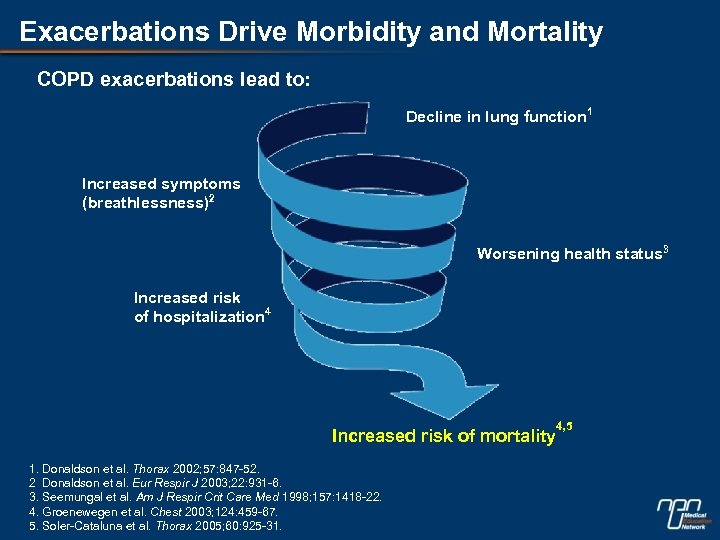

Exacerbations Drive Morbidity and Mortality COPD exacerbations lead to: Decline in lung function 1 Increased symptoms (breathlessness)2 Worsening health status 3 Increased risk of hospitalization 4 Increased risk of mortality 1. Donaldson et al. Thorax 2002; 57: 847 -52. 2 Donaldson et al. Eur Respir J 2003; 22: 931 -6. 3. Seemungal et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998; 157: 1418 -22. 4. Groenewegen et al. Chest 2003; 124: 459 -67. 5. Soler-Cataluna et al. Thorax 2005; 60: 925 -31. 4, 5

Exacerbations Drive Morbidity and Mortality COPD exacerbations lead to: Decline in lung function 1 Increased symptoms (breathlessness)2 Worsening health status 3 Increased risk of hospitalization 4 Increased risk of mortality 1. Donaldson et al. Thorax 2002; 57: 847 -52. 2 Donaldson et al. Eur Respir J 2003; 22: 931 -6. 3. Seemungal et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998; 157: 1418 -22. 4. Groenewegen et al. Chest 2003; 124: 459 -67. 5. Soler-Cataluna et al. Thorax 2005; 60: 925 -31. 4, 5

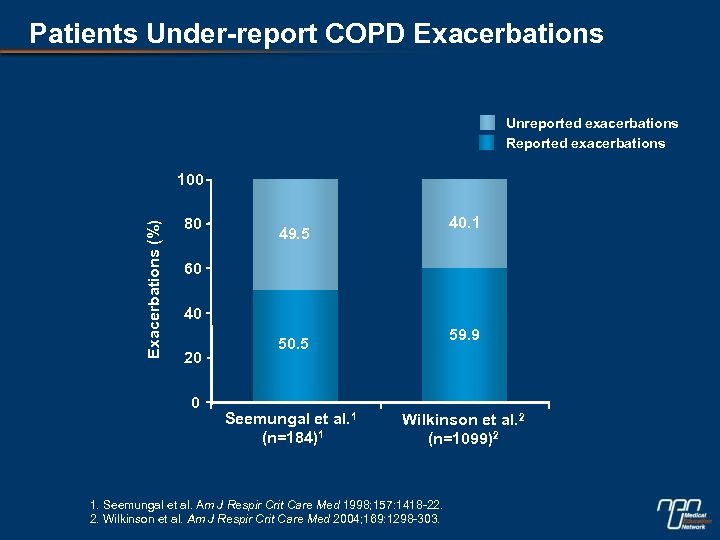

Patients Under-report COPD Exacerbations Unreported exacerbations Reported exacerbations Exacerbations (%) 100 80 40. 1 49. 5 60 40 20 0 59. 9 50. 5 Seemungal et al. 1 (n=184)1 Wilkinson et al. 2 (n=1099)2 1. Seemungal et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998; 157: 1418 -22. 2. Wilkinson et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2004; 169: 1298 -303.

Patients Under-report COPD Exacerbations Unreported exacerbations Reported exacerbations Exacerbations (%) 100 80 40. 1 49. 5 60 40 20 0 59. 9 50. 5 Seemungal et al. 1 (n=184)1 Wilkinson et al. 2 (n=1099)2 1. Seemungal et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998; 157: 1418 -22. 2. Wilkinson et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2004; 169: 1298 -303.

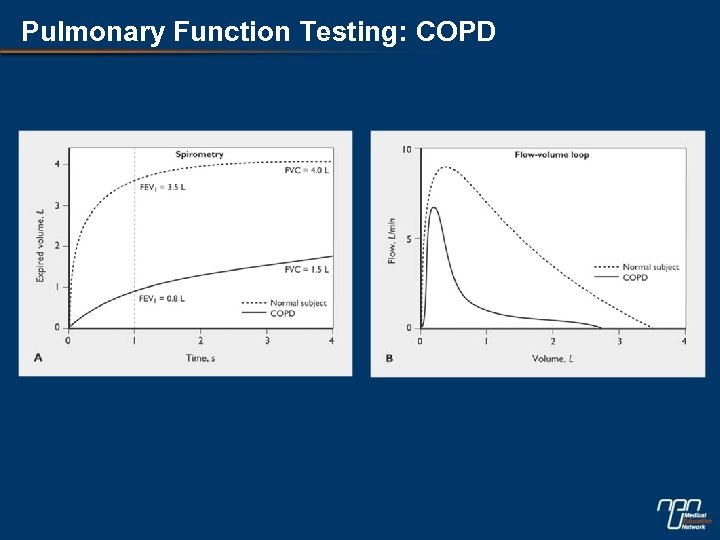

Pulmonary Function Testing: COPD

Pulmonary Function Testing: COPD

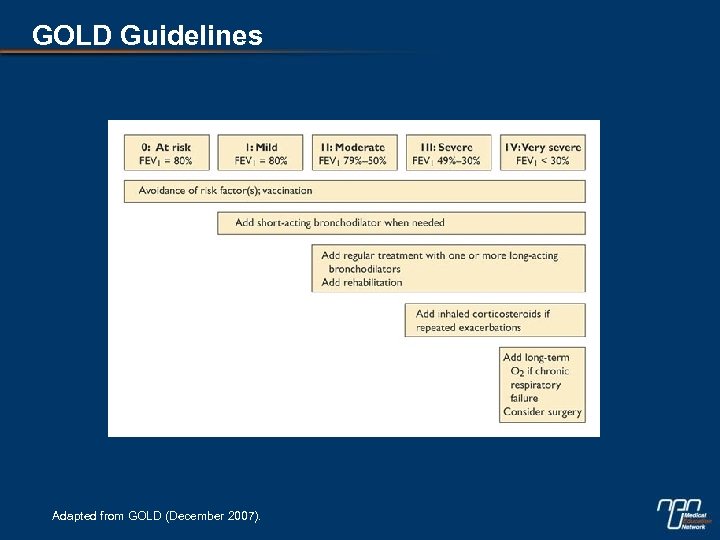

GOLD Guidelines Adapted from GOLD (December 2007).

GOLD Guidelines Adapted from GOLD (December 2007).

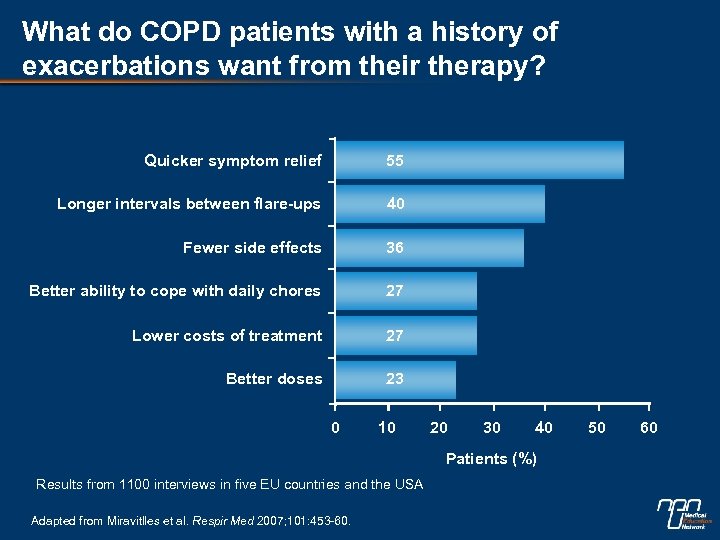

What do COPD patients with a history of exacerbations want from their therapy? Quicker symptom relief 55 Longer intervals between flare-ups 40 Fewer side effects 36 Better ability to cope with daily chores 27 Lower costs of treatment 27 Better doses 23 0 10 20 30 40 Patients (%) Results from 1100 interviews in five EU countries and the USA Adapted from Miravitlles et al. Respir Med 2007; 101: 453 -60. 50 60

What do COPD patients with a history of exacerbations want from their therapy? Quicker symptom relief 55 Longer intervals between flare-ups 40 Fewer side effects 36 Better ability to cope with daily chores 27 Lower costs of treatment 27 Better doses 23 0 10 20 30 40 Patients (%) Results from 1100 interviews in five EU countries and the USA Adapted from Miravitlles et al. Respir Med 2007; 101: 453 -60. 50 60

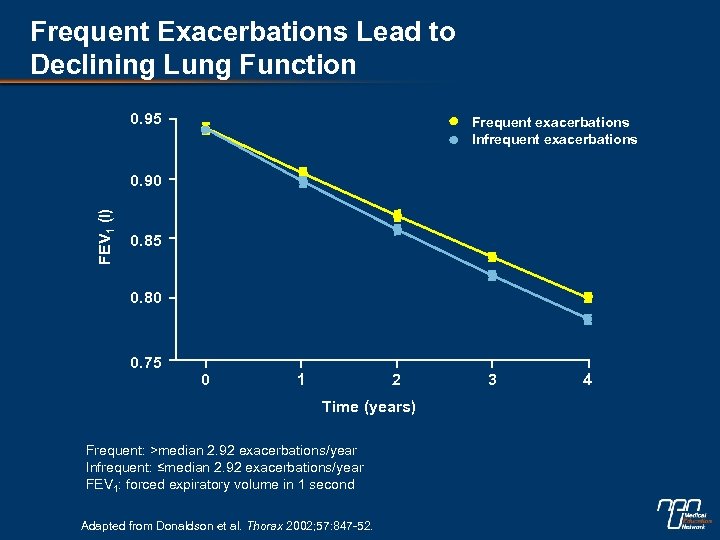

Frequent Exacerbations Lead to Declining Lung Function 0. 95 Frequent exacerbations Infrequent exacerbations FEV 1 (l) 0. 90 0. 85 0. 80 0. 75 0 1 2 Time (years) Frequent: >median 2. 92 exacerbations/year Infrequent: ≤median 2. 92 exacerbations/year FEV 1: forced expiratory volume in 1 second Adapted from Donaldson et al. Thorax 2002; 57: 847 -52. 3 4

Frequent Exacerbations Lead to Declining Lung Function 0. 95 Frequent exacerbations Infrequent exacerbations FEV 1 (l) 0. 90 0. 85 0. 80 0. 75 0 1 2 Time (years) Frequent: >median 2. 92 exacerbations/year Infrequent: ≤median 2. 92 exacerbations/year FEV 1: forced expiratory volume in 1 second Adapted from Donaldson et al. Thorax 2002; 57: 847 -52. 3 4

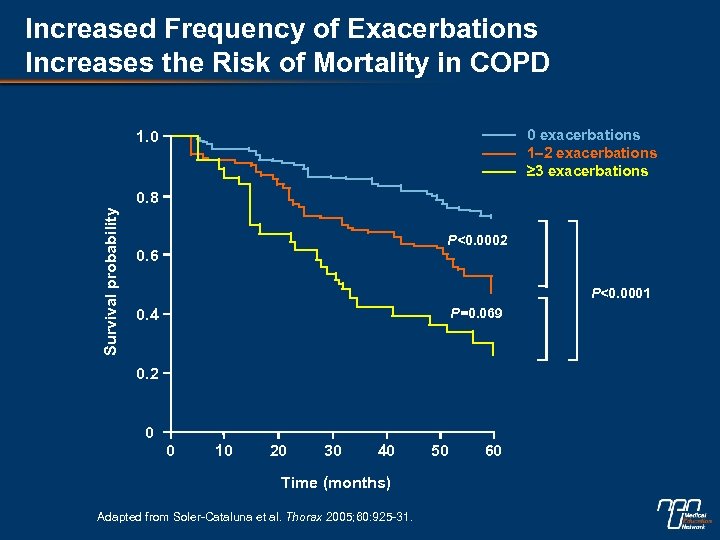

Increased Frequency of Exacerbations Increases the Risk of Mortality in COPD 0 exacerbations 1– 2 exacerbations ≥ 3 exacerbations 1. 0 Survival probability 0. 8 P<0. 0002 0. 6 P<0. 0001 P=0. 069 0. 4 0. 2 0 0 10 20 30 40 Time (months) Adapted from Soler-Cataluna et al. Thorax 2005; 60: 925 -31. 50 60

Increased Frequency of Exacerbations Increases the Risk of Mortality in COPD 0 exacerbations 1– 2 exacerbations ≥ 3 exacerbations 1. 0 Survival probability 0. 8 P<0. 0002 0. 6 P<0. 0001 P=0. 069 0. 4 0. 2 0 0 10 20 30 40 Time (months) Adapted from Soler-Cataluna et al. Thorax 2005; 60: 925 -31. 50 60

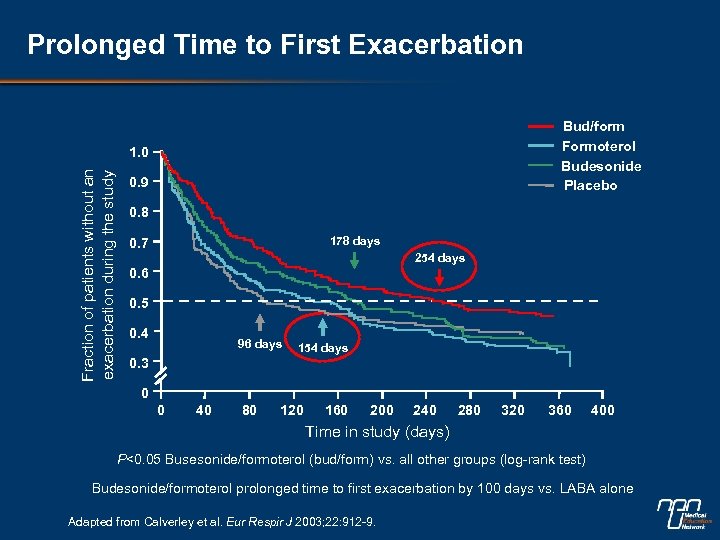

Prolonged Time to First Exacerbation Bud/form Formoterol Budesonide Placebo Fraction of patients without an exacerbation during the study 1. 0 0. 9 0. 8 178 days 0. 7 254 days 0. 6 0. 5 0. 4 96 days 154 days 0. 3 0 0 40 80 120 160 200 240 280 320 360 400 Time in study (days) P<0. 05 Busesonide/formoterol (bud/form) vs. all other groups (log-rank test) Budesonide/formoterol prolonged time to first exacerbation by 100 days vs. LABA alone Adapted from Calverley et al. Eur Respir J 2003; 22: 912 -9.

Prolonged Time to First Exacerbation Bud/form Formoterol Budesonide Placebo Fraction of patients without an exacerbation during the study 1. 0 0. 9 0. 8 178 days 0. 7 254 days 0. 6 0. 5 0. 4 96 days 154 days 0. 3 0 0 40 80 120 160 200 240 280 320 360 400 Time in study (days) P<0. 05 Busesonide/formoterol (bud/form) vs. all other groups (log-rank test) Budesonide/formoterol prolonged time to first exacerbation by 100 days vs. LABA alone Adapted from Calverley et al. Eur Respir J 2003; 22: 912 -9.

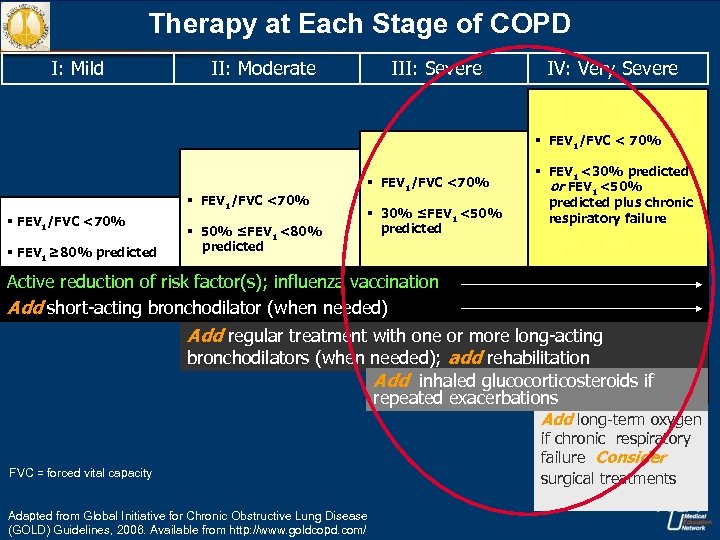

Therapy at Each Stage of COPD I: Mild II: Moderate III: Severe IV: Very Severe § FEV 1/FVC < 70% § FEV 1/FVC <70% § FEV 1 ≥ 80% predicted § 50% ≤FEV 1 <80% predicted § FEV 1/FVC <70% § 30% ≤FEV 1 <50% predicted § FEV 1 <30% predicted or FEV 1 <50% predicted plus chronic respiratory failure Active reduction of risk factor(s); influenza vaccination Add short-acting bronchodilator (when needed) Add regular treatment with one or more long-acting bronchodilators (when needed); add rehabilitation Add inhaled glucocorticosteroids if repeated exacerbations Add long-term oxygen FVC = forced vital capacity Adapted from Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) Guidelines, 2006. Available from http: //www. goldcopd. com/ if chronic respiratory failure Consider surgical treatments

Therapy at Each Stage of COPD I: Mild II: Moderate III: Severe IV: Very Severe § FEV 1/FVC < 70% § FEV 1/FVC <70% § FEV 1 ≥ 80% predicted § 50% ≤FEV 1 <80% predicted § FEV 1/FVC <70% § 30% ≤FEV 1 <50% predicted § FEV 1 <30% predicted or FEV 1 <50% predicted plus chronic respiratory failure Active reduction of risk factor(s); influenza vaccination Add short-acting bronchodilator (when needed) Add regular treatment with one or more long-acting bronchodilators (when needed); add rehabilitation Add inhaled glucocorticosteroids if repeated exacerbations Add long-term oxygen FVC = forced vital capacity Adapted from Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) Guidelines, 2006. Available from http: //www. goldcopd. com/ if chronic respiratory failure Consider surgical treatments

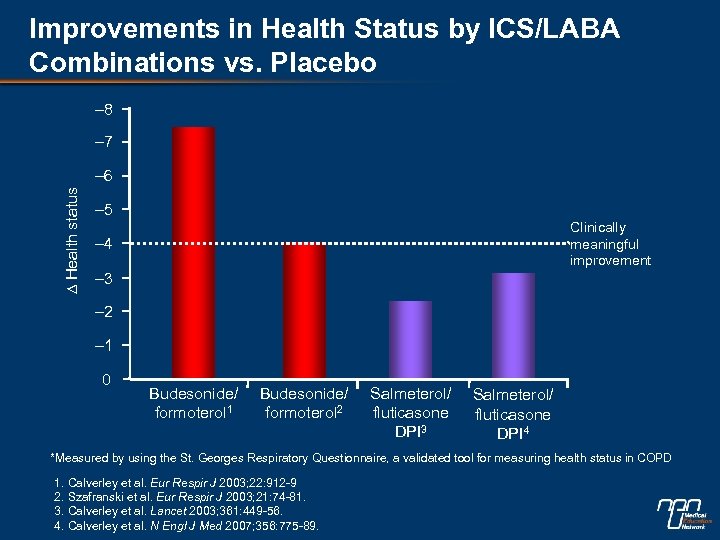

Improvements in Health Status by ICS/LABA Combinations vs. Placebo – 8 – 7 ∆ Health status – 6 – 5 Clinically meaningful improvement – 4 – 3 – 2 – 1 0 Budesonide/ formoterol 1 Budesonide/ formoterol 2 Salmeterol/ fluticasone DPI 3 Salmeterol/ fluticasone DPI 4 *Measured by using the St. Georges Respiratory Questionnaire, a validated tool for measuring health status in COPD 1. Calverley et al. Eur Respir J 2003; 22: 912 -9 2. Szafranski et al. Eur Respir J 2003; 21: 74 -81. 3. Calverley et al. Lancet 2003; 361: 449 -56. 4. Calverley et al. N Engl J Med 2007; 356: 775 -89.

Improvements in Health Status by ICS/LABA Combinations vs. Placebo – 8 – 7 ∆ Health status – 6 – 5 Clinically meaningful improvement – 4 – 3 – 2 – 1 0 Budesonide/ formoterol 1 Budesonide/ formoterol 2 Salmeterol/ fluticasone DPI 3 Salmeterol/ fluticasone DPI 4 *Measured by using the St. Georges Respiratory Questionnaire, a validated tool for measuring health status in COPD 1. Calverley et al. Eur Respir J 2003; 22: 912 -9 2. Szafranski et al. Eur Respir J 2003; 21: 74 -81. 3. Calverley et al. Lancet 2003; 361: 449 -56. 4. Calverley et al. N Engl J Med 2007; 356: 775 -89.

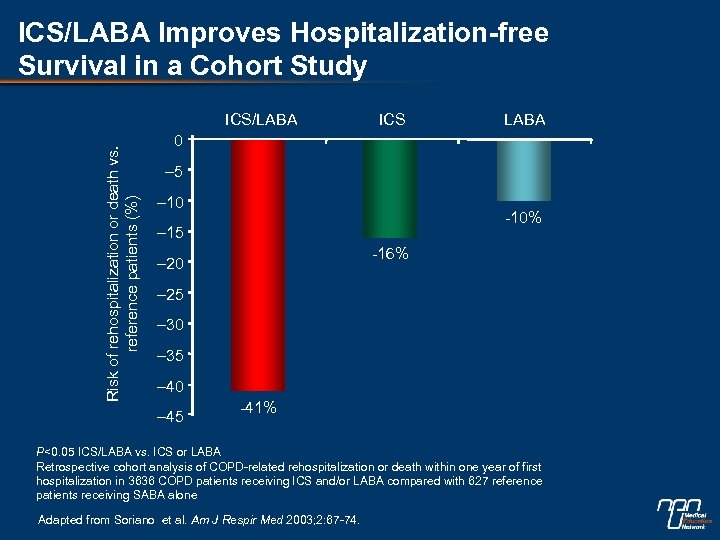

ICS/LABA Improves Hospitalization-free Survival in a Cohort Study Risk of rehospitalization or death vs. reference patients (%) ICS/LABA ICS LABA 0 – 5 – 10 -10% – 15 -16% – 20 – 25 – 30 – 35 – 40 – 45 -41% P<0. 05 ICS/LABA vs. ICS or LABA Retrospective cohort analysis of COPD-related rehospitalization or death within one year of first hospitalization in 3636 COPD patients receiving ICS and/or LABA compared with 627 reference patients receiving SABA alone Adapted from Soriano et al. Am J Respir Med 2003; 2: 67 -74.

ICS/LABA Improves Hospitalization-free Survival in a Cohort Study Risk of rehospitalization or death vs. reference patients (%) ICS/LABA ICS LABA 0 – 5 – 10 -10% – 15 -16% – 20 – 25 – 30 – 35 – 40 – 45 -41% P<0. 05 ICS/LABA vs. ICS or LABA Retrospective cohort analysis of COPD-related rehospitalization or death within one year of first hospitalization in 3636 COPD patients receiving ICS and/or LABA compared with 627 reference patients receiving SABA alone Adapted from Soriano et al. Am J Respir Med 2003; 2: 67 -74.

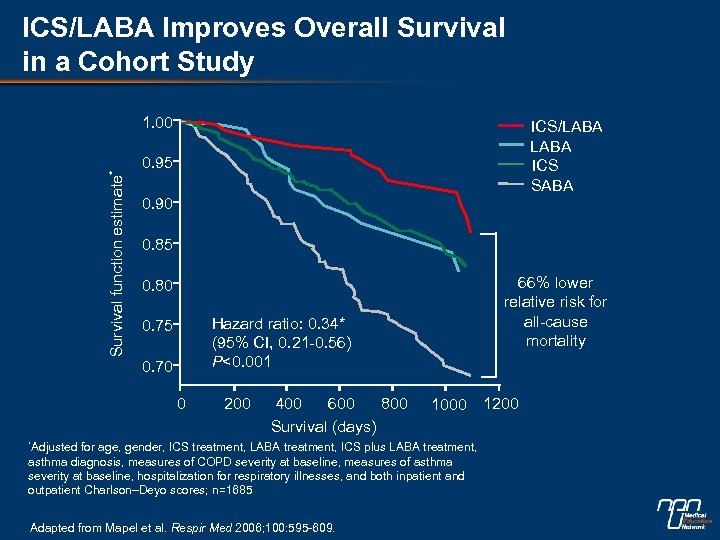

ICS/LABA Improves Overall Survival in a Cohort Study Survival function estimate* 1. 00 ICS/LABA ICS SABA 0. 95 0. 90 0. 85 66% lower relative risk for all-cause mortality 0. 80 Hazard ratio: 0. 34* (95% CI, 0. 21 -0. 56) P<0. 001 0. 75 0. 70 0 200 400 600 800 Survival (days) *Adjusted 1000 for age, gender, ICS treatment, LABA treatment, ICS plus LABA treatment, asthma diagnosis, measures of COPD severity at baseline, measures of asthma severity at baseline, hospitalization for respiratory illnesses, and both inpatient and outpatient Charlson–Deyo scores; n=1685 Adapted from Mapel et al. Respir Med 2006; 100: 595 -609. 1200

ICS/LABA Improves Overall Survival in a Cohort Study Survival function estimate* 1. 00 ICS/LABA ICS SABA 0. 95 0. 90 0. 85 66% lower relative risk for all-cause mortality 0. 80 Hazard ratio: 0. 34* (95% CI, 0. 21 -0. 56) P<0. 001 0. 75 0. 70 0 200 400 600 800 Survival (days) *Adjusted 1000 for age, gender, ICS treatment, LABA treatment, ICS plus LABA treatment, asthma diagnosis, measures of COPD severity at baseline, measures of asthma severity at baseline, hospitalization for respiratory illnesses, and both inpatient and outpatient Charlson–Deyo scores; n=1685 Adapted from Mapel et al. Respir Med 2006; 100: 595 -609. 1200

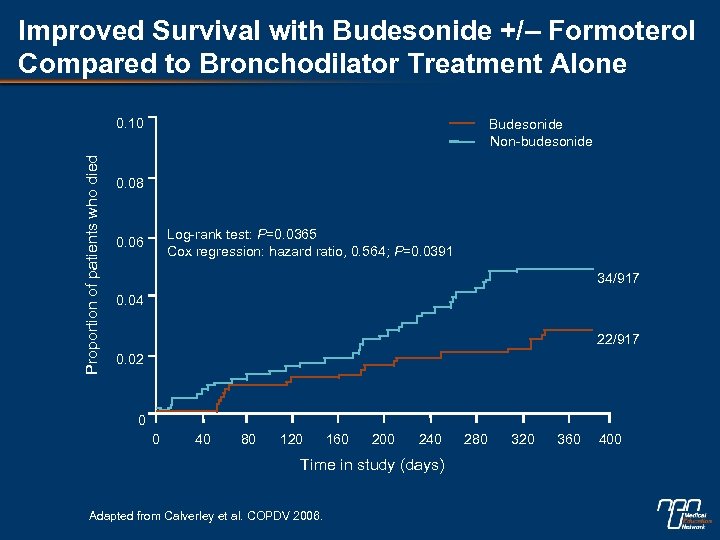

Improved Survival with Budesonide +/– Formoterol Compared to Bronchodilator Treatment Alone Proportion of patients who died 0. 10 Budesonide Non-budesonide 0. 08 Log-rank test: P=0. 0365 Cox regression: hazard ratio, 0. 564; P=0. 0391 0. 06 34/917 0. 04 22/917 0. 02 0 0 40 80 120 160 200 240 Time in study (days) Adapted from Calverley et al. COPDV 2006. 280 320 360 400

Improved Survival with Budesonide +/– Formoterol Compared to Bronchodilator Treatment Alone Proportion of patients who died 0. 10 Budesonide Non-budesonide 0. 08 Log-rank test: P=0. 0365 Cox regression: hazard ratio, 0. 564; P=0. 0391 0. 06 34/917 0. 04 22/917 0. 02 0 0 40 80 120 160 200 240 Time in study (days) Adapted from Calverley et al. COPDV 2006. 280 320 360 400

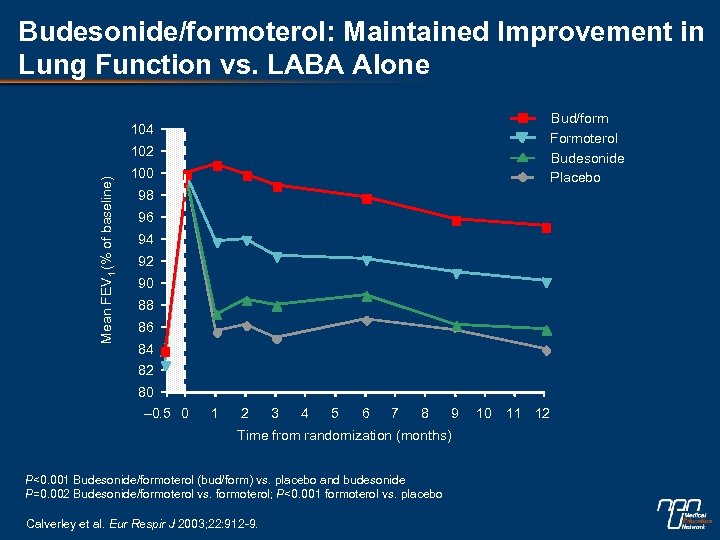

Budesonide/formoterol: Maintained Improvement in Lung Function vs. LABA Alone Bud/form Formoterol Budesonide Placebo 104 Mean FEV 1 (% of baseline) 102 100 98 96 94 92 90 88 86 84 82 80 – 0. 5 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Time from randomization (months) P<0. 001 Budesonide/formoterol (bud/form) vs. placebo and budesonide P=0. 002 Budesonide/formoterol vs. formoterol; P<0. 001 formoterol vs. placebo Calverley et al. Eur Respir J 2003; 22: 912 -9. 10 11 12

Budesonide/formoterol: Maintained Improvement in Lung Function vs. LABA Alone Bud/form Formoterol Budesonide Placebo 104 Mean FEV 1 (% of baseline) 102 100 98 96 94 92 90 88 86 84 82 80 – 0. 5 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Time from randomization (months) P<0. 001 Budesonide/formoterol (bud/form) vs. placebo and budesonide P=0. 002 Budesonide/formoterol vs. formoterol; P<0. 001 formoterol vs. placebo Calverley et al. Eur Respir J 2003; 22: 912 -9. 10 11 12

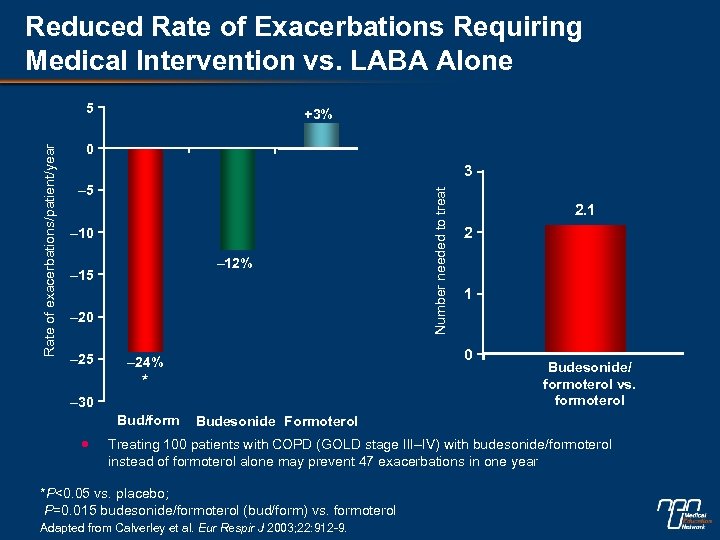

Reduced Rate of Exacerbations Requiring Medical Intervention vs. LABA Alone +3% 0 3 – 5 – 10 – 12% – 15 – 20 – 25 * – 30 2. 1 2 1 0 – 24% Bud/form Number needed to treat Rate of exacerbations/patient/year 5 Budesonide/ formoterol vs. formoterol Budesonide Formoterol Treating 100 patients with COPD (GOLD stage III–IV) with budesonide/formoterol instead of formoterol alone may prevent 47 exacerbations in one year *P<0. 05 vs. placebo; P=0. 015 budesonide/formoterol (bud/form) vs. formoterol Adapted from Calverley et al. Eur Respir J 2003; 22: 912 -9.

Reduced Rate of Exacerbations Requiring Medical Intervention vs. LABA Alone +3% 0 3 – 5 – 10 – 12% – 15 – 20 – 25 * – 30 2. 1 2 1 0 – 24% Bud/form Number needed to treat Rate of exacerbations/patient/year 5 Budesonide/ formoterol vs. formoterol Budesonide Formoterol Treating 100 patients with COPD (GOLD stage III–IV) with budesonide/formoterol instead of formoterol alone may prevent 47 exacerbations in one year *P<0. 05 vs. placebo; P=0. 015 budesonide/formoterol (bud/form) vs. formoterol Adapted from Calverley et al. Eur Respir J 2003; 22: 912 -9.

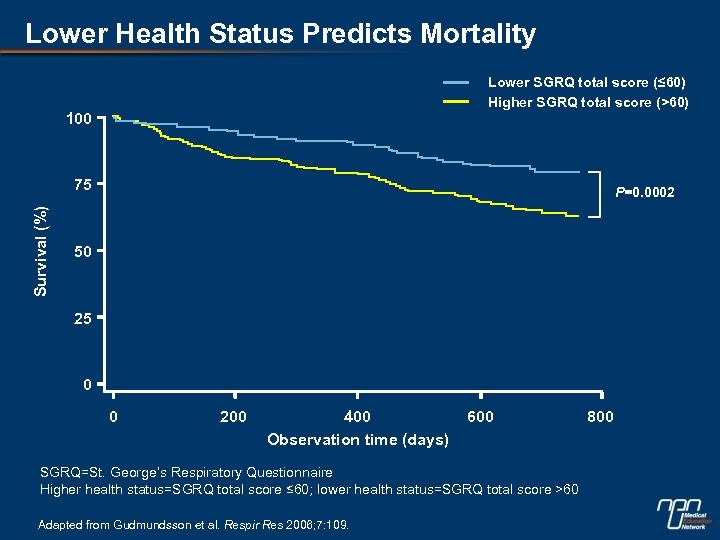

Lower Health Status Predicts Mortality Lower SGRQ total score (≤ 60) Higher SGRQ total score (>60) 100 Survival (%) 75 P=0. 0002 50 25 0 0 200 400 Observation time (days) 600 SGRQ=St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire Higher health status=SGRQ total score ≤ 60; lower health status=SGRQ total score >60 Adapted from Gudmundsson et al. Respir Res 2006; 7: 109. 800

Lower Health Status Predicts Mortality Lower SGRQ total score (≤ 60) Higher SGRQ total score (>60) 100 Survival (%) 75 P=0. 0002 50 25 0 0 200 400 Observation time (days) 600 SGRQ=St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire Higher health status=SGRQ total score ≤ 60; lower health status=SGRQ total score >60 Adapted from Gudmundsson et al. Respir Res 2006; 7: 109. 800

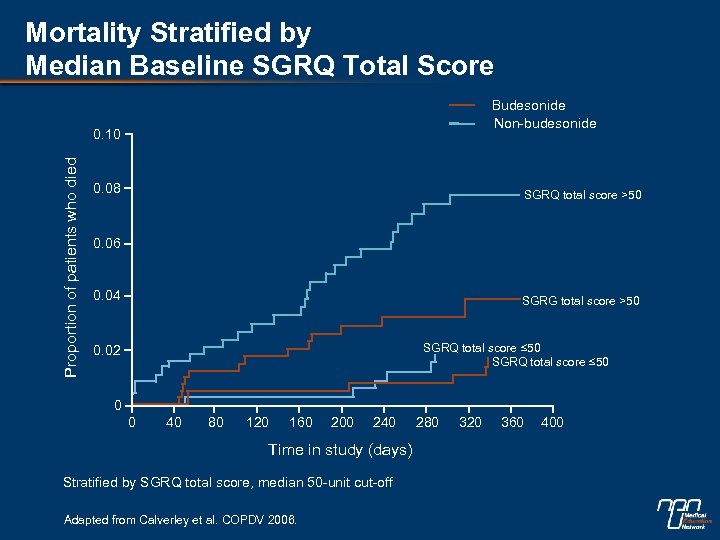

Mortality Stratified by Median Baseline SGRQ Total Score Budesonide Non-budesonide Proportion of patients who died 0. 10 0. 08 SGRQ total score >50 0. 06 0. 04 SGRG total score >50 SGRQ total score ≤ 50 0. 02 0 0 40 80 120 160 200 240 Time in study (days) Stratified by SGRQ total score, median 50 -unit cut-off Adapted from Calverley et al. COPDV 2006. 280 320 360 400

Mortality Stratified by Median Baseline SGRQ Total Score Budesonide Non-budesonide Proportion of patients who died 0. 10 0. 08 SGRQ total score >50 0. 06 0. 04 SGRG total score >50 SGRQ total score ≤ 50 0. 02 0 0 40 80 120 160 200 240 Time in study (days) Stratified by SGRQ total score, median 50 -unit cut-off Adapted from Calverley et al. COPDV 2006. 280 320 360 400

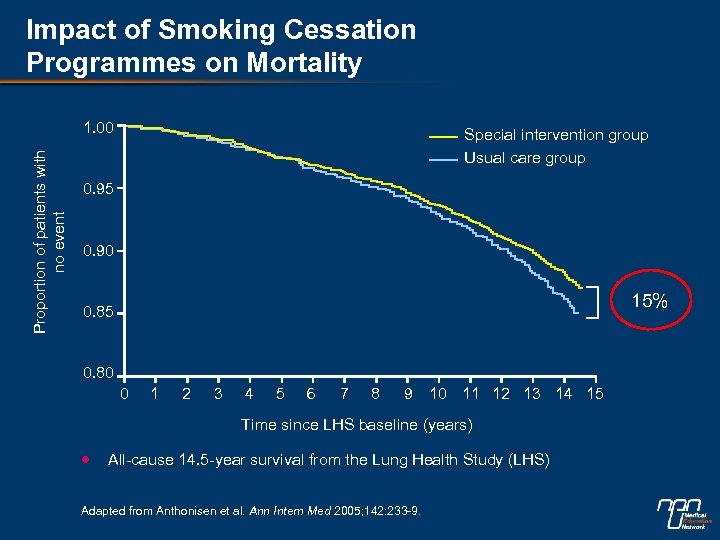

Impact of Smoking Cessation Programmes on Mortality Proportion of patients with no event 1. 00 Special intervention group Usual care group 0. 95 0. 90 15% 0. 85 0. 80 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Time since LHS baseline (years) All-cause 14. 5 -year survival from the Lung Health Study (LHS) Adapted from Anthonisen et al. Ann Intern Med 2005; 142: 233 -9.

Impact of Smoking Cessation Programmes on Mortality Proportion of patients with no event 1. 00 Special intervention group Usual care group 0. 95 0. 90 15% 0. 85 0. 80 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Time since LHS baseline (years) All-cause 14. 5 -year survival from the Lung Health Study (LHS) Adapted from Anthonisen et al. Ann Intern Med 2005; 142: 233 -9.

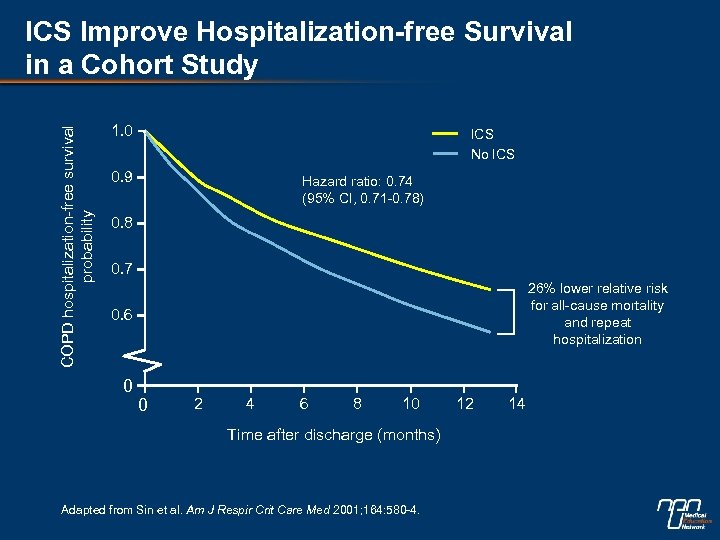

COPD hospitalization-free survival probability ICS Improve Hospitalization-free Survival in a Cohort Study 1. 0 ICS No ICS 0. 9 Hazard ratio: 0. 74 (95% CI, 0. 71 -0. 78) 0. 8 0. 7 26% lower relative risk for all-cause mortality and repeat hospitalization 0. 6 0 0 2 4 6 8 10 Time after discharge (months) Adapted from Sin et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001; 164: 580 -4. 12 14

COPD hospitalization-free survival probability ICS Improve Hospitalization-free Survival in a Cohort Study 1. 0 ICS No ICS 0. 9 Hazard ratio: 0. 74 (95% CI, 0. 71 -0. 78) 0. 8 0. 7 26% lower relative risk for all-cause mortality and repeat hospitalization 0. 6 0 0 2 4 6 8 10 Time after discharge (months) Adapted from Sin et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001; 164: 580 -4. 12 14

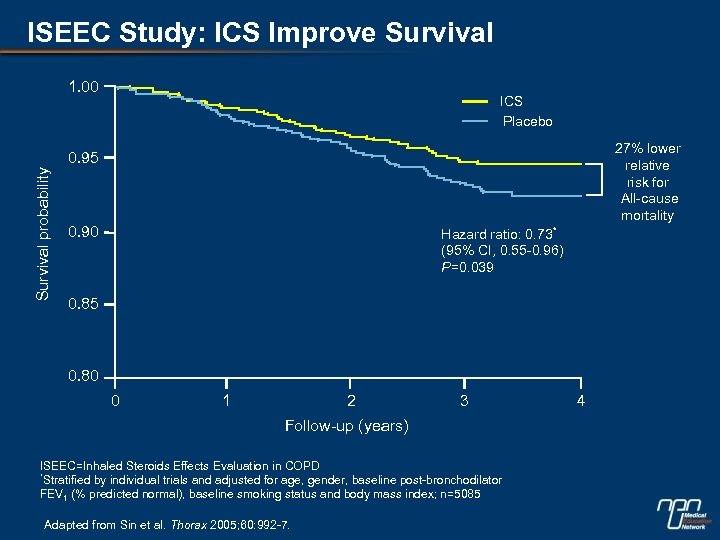

ISEEC Study: ICS Improve Survival 1. 00 ICS Placebo 27% lower relative risk for All-cause mortality Survival probability 0. 95 0. 90 Hazard ratio: 0. 73* (95% CI, 0. 55 -0. 96) P=0. 039 0. 85 0. 80 0 1 2 3 Follow-up (years) ISEEC=Inhaled Steroids Effects Evaluation in COPD *Stratified by individual trials and adjusted for age, gender, baseline post-bronchodilator FEV 1 (% predicted normal), baseline smoking status and body mass index; n=5085 Adapted from Sin et al. Thorax 2005; 60: 992 -7. 4

ISEEC Study: ICS Improve Survival 1. 00 ICS Placebo 27% lower relative risk for All-cause mortality Survival probability 0. 95 0. 90 Hazard ratio: 0. 73* (95% CI, 0. 55 -0. 96) P=0. 039 0. 85 0. 80 0 1 2 3 Follow-up (years) ISEEC=Inhaled Steroids Effects Evaluation in COPD *Stratified by individual trials and adjusted for age, gender, baseline post-bronchodilator FEV 1 (% predicted normal), baseline smoking status and body mass index; n=5085 Adapted from Sin et al. Thorax 2005; 60: 992 -7. 4

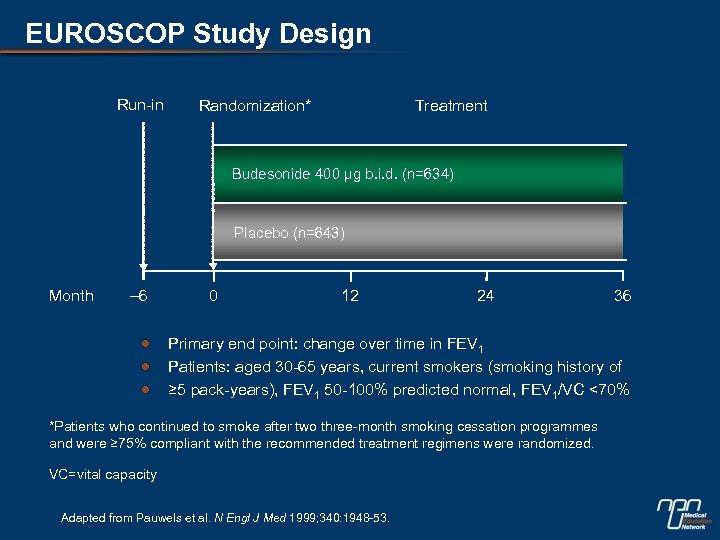

EUROSCOP Study Design Run-in Treatment Randomization* Budesonide 400 µg b. i. d. (n=634) Placebo (n=643) Month – 6 0 12 24 36 Primary end point: change over time in FEV 1 Patients: aged 30 -65 years, current smokers (smoking history of ≥ 5 pack-years), FEV 1 50 -100% predicted normal, FEV 1/VC <70% *Patients who continued to smoke after two three-month smoking cessation programmes and were ≥ 75% compliant with the recommended treatment regimens were randomized. VC=vital capacity Adapted from Pauwels et al. N Engl J Med 1999; 340: 1948 -53.

EUROSCOP Study Design Run-in Treatment Randomization* Budesonide 400 µg b. i. d. (n=634) Placebo (n=643) Month – 6 0 12 24 36 Primary end point: change over time in FEV 1 Patients: aged 30 -65 years, current smokers (smoking history of ≥ 5 pack-years), FEV 1 50 -100% predicted normal, FEV 1/VC <70% *Patients who continued to smoke after two three-month smoking cessation programmes and were ≥ 75% compliant with the recommended treatment regimens were randomized. VC=vital capacity Adapted from Pauwels et al. N Engl J Med 1999; 340: 1948 -53.

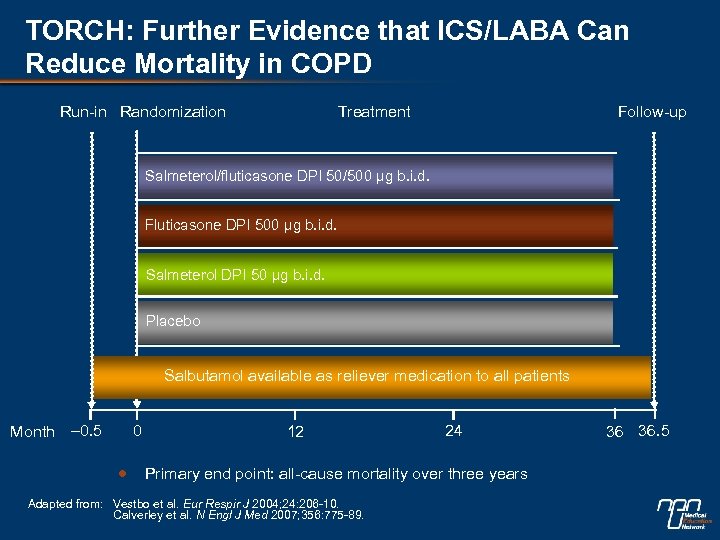

TORCH: Further Evidence that ICS/LABA Can Reduce Mortality in COPD Run-in Randomization Treatment Follow-up Salmeterol/fluticasone DPI 50/500 µg b. i. d. Fluticasone DPI 500 µg b. i. d. Salmeterol DPI 50 µg b. i. d. Placebo Salbutamol available as reliever medication to all patients Month – 0. 5 0 12 24 Primary end point: all-cause mortality over three years Adapted from: Vestbo et al. Eur Respir J 2004; 24: 206 -10. Calverley et al. N Engl J Med 2007; 356: 775 -89. 36 36. 5

TORCH: Further Evidence that ICS/LABA Can Reduce Mortality in COPD Run-in Randomization Treatment Follow-up Salmeterol/fluticasone DPI 50/500 µg b. i. d. Fluticasone DPI 500 µg b. i. d. Salmeterol DPI 50 µg b. i. d. Placebo Salbutamol available as reliever medication to all patients Month – 0. 5 0 12 24 Primary end point: all-cause mortality over three years Adapted from: Vestbo et al. Eur Respir J 2004; 24: 206 -10. Calverley et al. N Engl J Med 2007; 356: 775 -89. 36 36. 5

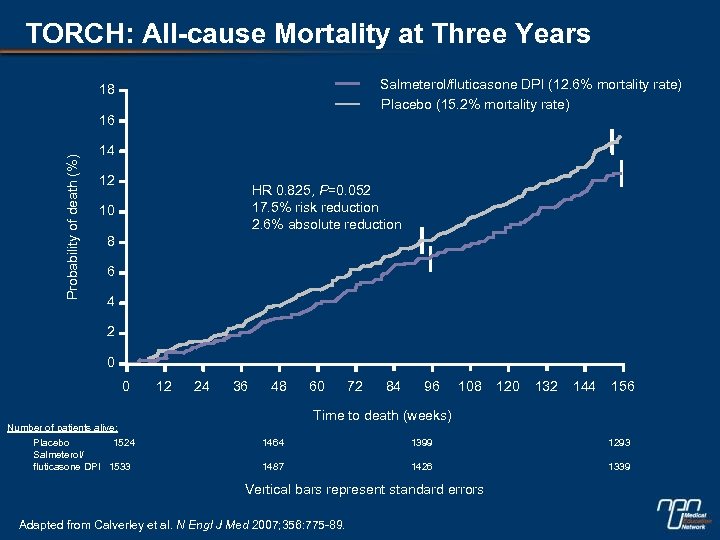

TORCH: All-cause Mortality at Three Years Salmeterol/fluticasone DPI (12. 6% mortality rate) Placebo (15. 2% mortality rate) 18 Probability of death (%) 16 14 12 HR 0. 825, P=0. 052 17. 5% risk reduction 2. 6% absolute reduction 10 8 6 4 2 0 0 12 24 36 48 72 84 96 108 120 132 144 156 Time to death (weeks) Number of patients alive: Placebo 1524 Salmeterol/ fluticasone DPI 1533 60 1464 1399 1293 1487 1426 1339 Vertical bars represent standard errors Adapted from Calverley et al. N Engl J Med 2007; 356: 775 -89.

TORCH: All-cause Mortality at Three Years Salmeterol/fluticasone DPI (12. 6% mortality rate) Placebo (15. 2% mortality rate) 18 Probability of death (%) 16 14 12 HR 0. 825, P=0. 052 17. 5% risk reduction 2. 6% absolute reduction 10 8 6 4 2 0 0 12 24 36 48 72 84 96 108 120 132 144 156 Time to death (weeks) Number of patients alive: Placebo 1524 Salmeterol/ fluticasone DPI 1533 60 1464 1399 1293 1487 1426 1339 Vertical bars represent standard errors Adapted from Calverley et al. N Engl J Med 2007; 356: 775 -89.

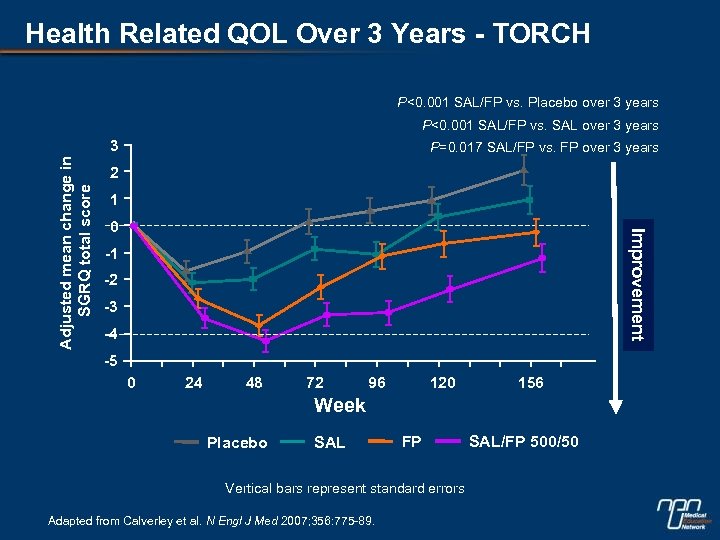

Health Related QOL Over 3 Years - TORCH P<0. 001 SAL/FP vs. Placebo over 3 years P<0. 001 SAL/FP vs. SAL over 3 years P=0. 017 SAL/FP vs. FP over 3 years 2 1 0 Improvement Adjusted mean change in SGRQ total score 3 -1 -2 -3 -4 -5 0 24 48 72 96 120 156 Week Placebo SAL FP Vertical bars represent standard errors Adapted from Calverley et al. N Engl J Med 2007; 356: 775 -89. SAL/FP 500/50

Health Related QOL Over 3 Years - TORCH P<0. 001 SAL/FP vs. Placebo over 3 years P<0. 001 SAL/FP vs. SAL over 3 years P=0. 017 SAL/FP vs. FP over 3 years 2 1 0 Improvement Adjusted mean change in SGRQ total score 3 -1 -2 -3 -4 -5 0 24 48 72 96 120 156 Week Placebo SAL FP Vertical bars represent standard errors Adapted from Calverley et al. N Engl J Med 2007; 356: 775 -89. SAL/FP 500/50

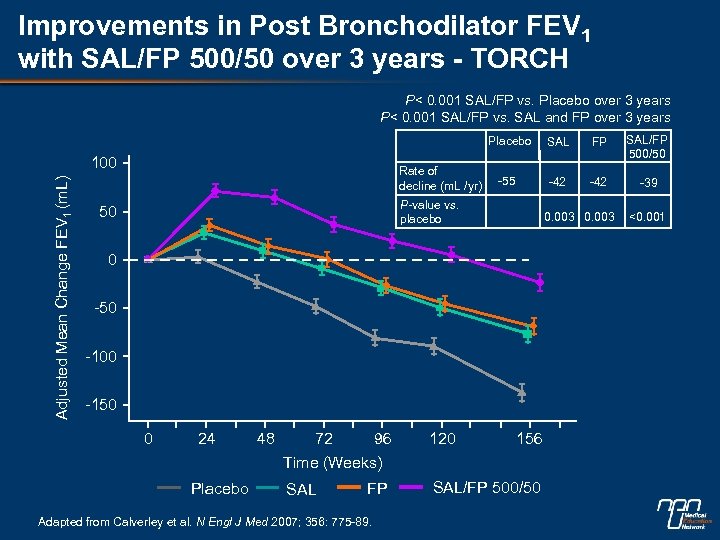

Improvements in Post Bronchodilator FEV 1 with SAL/FP 500/50 over 3 years - TORCH P< 0. 001 SAL/FP vs. Placebo over 3 years P< 0. 001 SAL/FP vs. SAL and FP over 3 years Placebo Adjusted Mean Change FEV 1 (m. L) 100 Rate of decline (m. L /yr) SAL FP SAL/FP 500/50 -55 -42 -39 P-value vs. placebo 50 0. 003 0 -50 -100 -150 0 24 Placebo 48 72 96 Time (Weeks) SAL FP Adapted from Calverley et al. N Engl J Med 2007; 356: 775 -89. 120 156 SAL/FP 500/50 <0. 001

Improvements in Post Bronchodilator FEV 1 with SAL/FP 500/50 over 3 years - TORCH P< 0. 001 SAL/FP vs. Placebo over 3 years P< 0. 001 SAL/FP vs. SAL and FP over 3 years Placebo Adjusted Mean Change FEV 1 (m. L) 100 Rate of decline (m. L /yr) SAL FP SAL/FP 500/50 -55 -42 -39 P-value vs. placebo 50 0. 003 0 -50 -100 -150 0 24 Placebo 48 72 96 Time (Weeks) SAL FP Adapted from Calverley et al. N Engl J Med 2007; 356: 775 -89. 120 156 SAL/FP 500/50 <0. 001

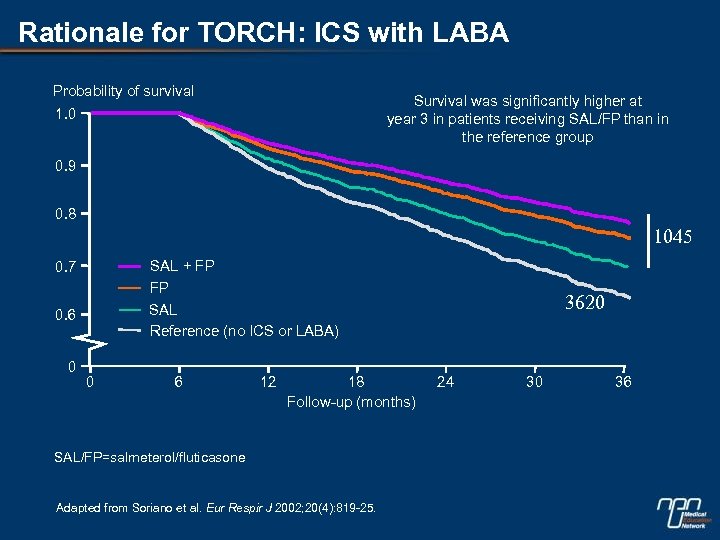

Rationale for TORCH: ICS with LABA Probability of survival 1. 0 Survival was significantly higher at year 3 in patients receiving SAL/FP than in the reference group 0. 9 0. 8 1045 0. 7 SAL + FP 0. 6 FP SAL Reference (no ICS or LABA) 0 0 6 12 18 Follow-up (months) SAL/FP=salmeterol/fluticasone Adapted from Soriano et al. Eur Respir J 2002; 20(4): 819 -25. 3620 24 30 36

Rationale for TORCH: ICS with LABA Probability of survival 1. 0 Survival was significantly higher at year 3 in patients receiving SAL/FP than in the reference group 0. 9 0. 8 1045 0. 7 SAL + FP 0. 6 FP SAL Reference (no ICS or LABA) 0 0 6 12 18 Follow-up (months) SAL/FP=salmeterol/fluticasone Adapted from Soriano et al. Eur Respir J 2002; 20(4): 819 -25. 3620 24 30 36