2b78fe9c60151d43c75823dde5120666.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 65

CSCI 2210: Programming in Lisp ANSI Common Lisp, Chapters 5 -10 CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 1

CSCI 2210: Programming in Lisp ANSI Common Lisp, Chapters 5 -10 CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 1

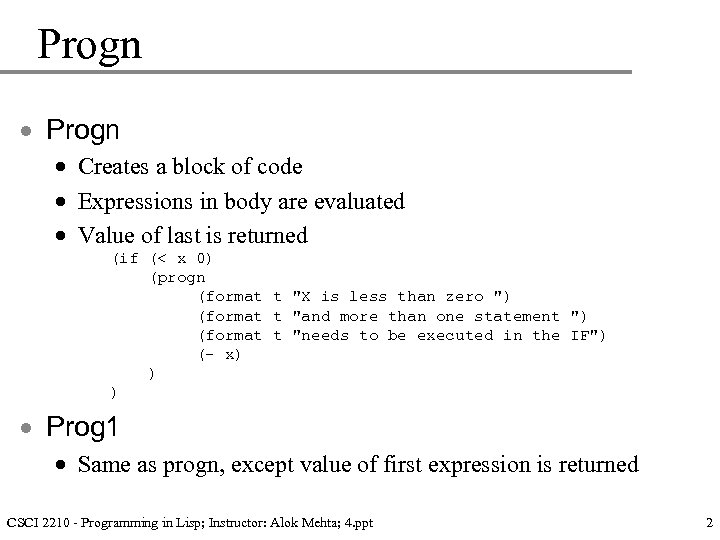

Progn · Creates a block of code · Expressions in body are evaluated · Value of last is returned (if (< x 0) (progn (format t "X is less than zero ") (format t "and more than one statement ") (format t "needs to be executed in the IF") (- x) ) ) · Prog 1 · Same as progn, except value of first expression is returned CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 2

Progn · Creates a block of code · Expressions in body are evaluated · Value of last is returned (if (< x 0) (progn (format t "X is less than zero ") (format t "and more than one statement ") (format t "needs to be executed in the IF") (- x) ) ) · Prog 1 · Same as progn, except value of first expression is returned CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 2

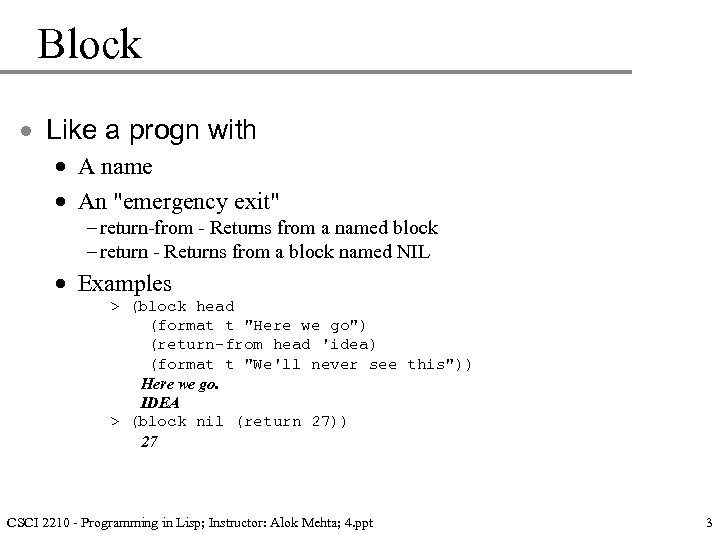

Block · Like a progn with · A name · An "emergency exit" – return-from - Returns from a named block – return - Returns from a block named NIL · Examples > (block head (format t "Here we go") (return-from head 'idea) (format t "We'll never see this")) Here we go. IDEA > (block nil (return 27)) 27 CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 3

Block · Like a progn with · A name · An "emergency exit" – return-from - Returns from a named block – return - Returns from a block named NIL · Examples > (block head (format t "Here we go") (return-from head 'idea) (format t "We'll never see this")) Here we go. IDEA > (block nil (return 27)) 27 CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 3

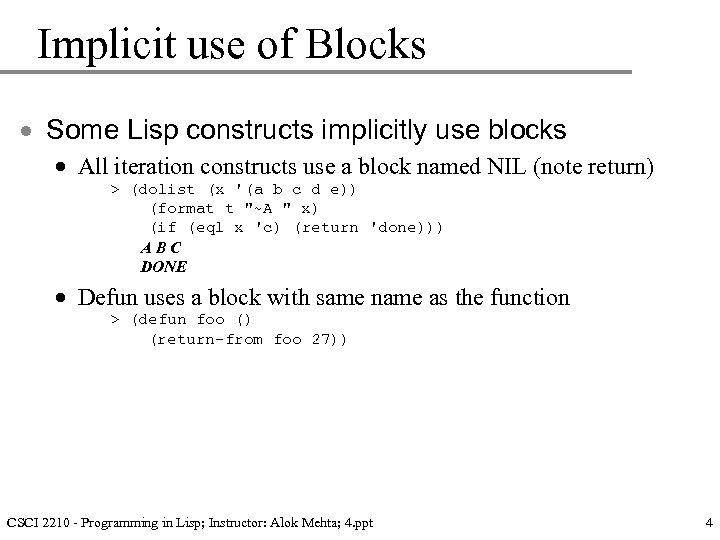

Implicit use of Blocks · Some Lisp constructs implicitly use blocks · All iteration constructs use a block named NIL (note return) > (dolist (x '(a b c d e)) (format t "~A " x) (if (eql x 'c) (return 'done))) ABC DONE · Defun uses a block with same name as the function > (defun foo () (return-from foo 27)) CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 4

Implicit use of Blocks · Some Lisp constructs implicitly use blocks · All iteration constructs use a block named NIL (note return) > (dolist (x '(a b c d e)) (format t "~A " x) (if (eql x 'c) (return 'done))) ABC DONE · Defun uses a block with same name as the function > (defun foo () (return-from foo 27)) CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 4

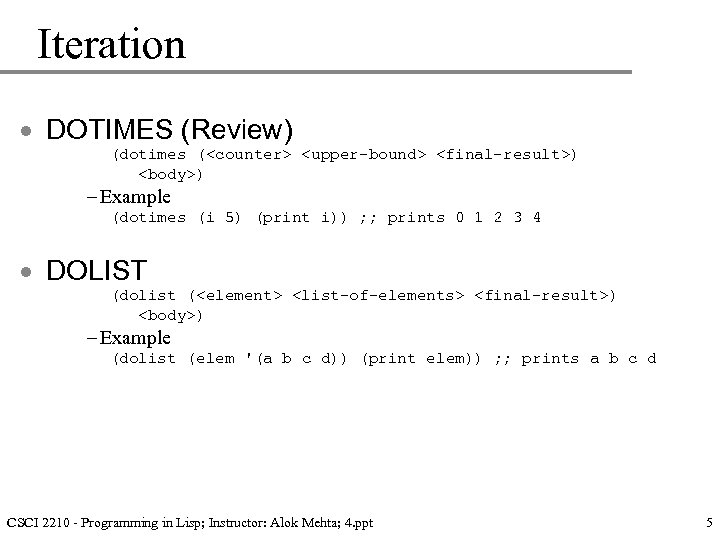

Iteration · DOTIMES (Review) (dotimes (

Iteration · DOTIMES (Review) (dotimes (

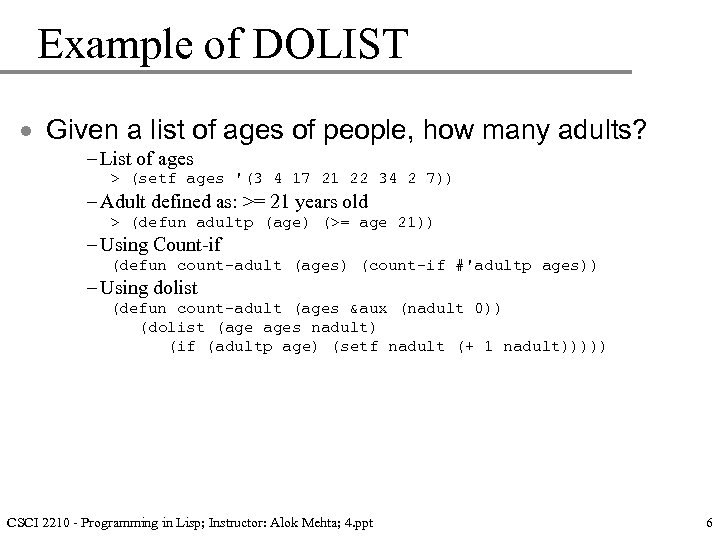

Example of DOLIST · Given a list of ages of people, how many adults? – List of ages > (setf ages '(3 4 17 21 22 34 2 7)) – Adult defined as: >= 21 years old > (defun adultp (age) (>= age 21)) – Using Count-if (defun count-adult (ages) (count-if #'adultp ages)) – Using dolist (defun count-adult (ages &aux (nadult 0)) (dolist (age ages nadult) (if (adultp age) (setf nadult (+ 1 nadult))))) CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 6

Example of DOLIST · Given a list of ages of people, how many adults? – List of ages > (setf ages '(3 4 17 21 22 34 2 7)) – Adult defined as: >= 21 years old > (defun adultp (age) (>= age 21)) – Using Count-if (defun count-adult (ages) (count-if #'adultp ages)) – Using dolist (defun count-adult (ages &aux (nadult 0)) (dolist (age ages nadult) (if (adultp age) (setf nadult (+ 1 nadult))))) CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 6

Example (cont. ) · Get the ages of the first two adults (defun first-two-adults (ages &aux (nadult 0) (adults nil)) (dolist (age ages) (if (adultp age) (progn (setf nadult (+ nadult 1)) (push age adults) (if (= nadult 2) (return adults)))))) · Notes · PROGN (and PROG 1) are like C/C++ Blocks { … } > (prog 1 (setf a 'x) (setf b 'y) (setf c 'z)) X > (progn (setf a 'x) (setf b 'y) (setf c 'z)) Z · RETURN exits the DOLIST block – Note: does not necessarily return from the procedure! – Takes an optional return value CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 7

Example (cont. ) · Get the ages of the first two adults (defun first-two-adults (ages &aux (nadult 0) (adults nil)) (dolist (age ages) (if (adultp age) (progn (setf nadult (+ nadult 1)) (push age adults) (if (= nadult 2) (return adults)))))) · Notes · PROGN (and PROG 1) are like C/C++ Blocks { … } > (prog 1 (setf a 'x) (setf b 'y) (setf c 'z)) X > (progn (setf a 'x) (setf b 'y) (setf c 'z)) Z · RETURN exits the DOLIST block – Note: does not necessarily return from the procedure! – Takes an optional return value CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 7

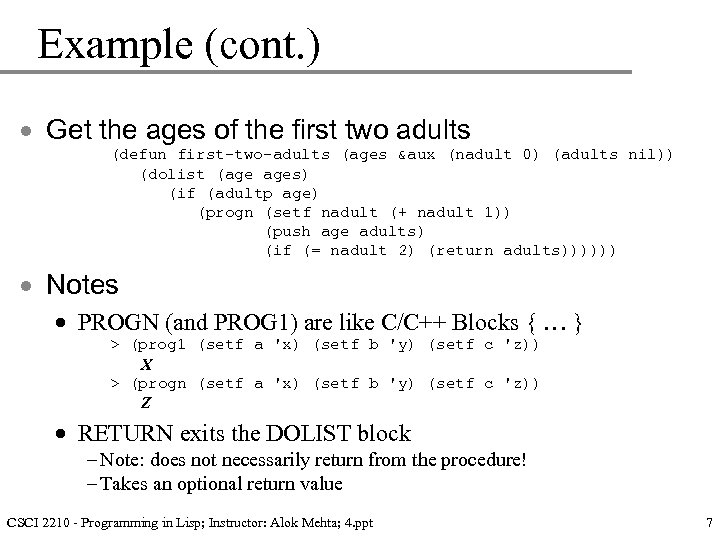

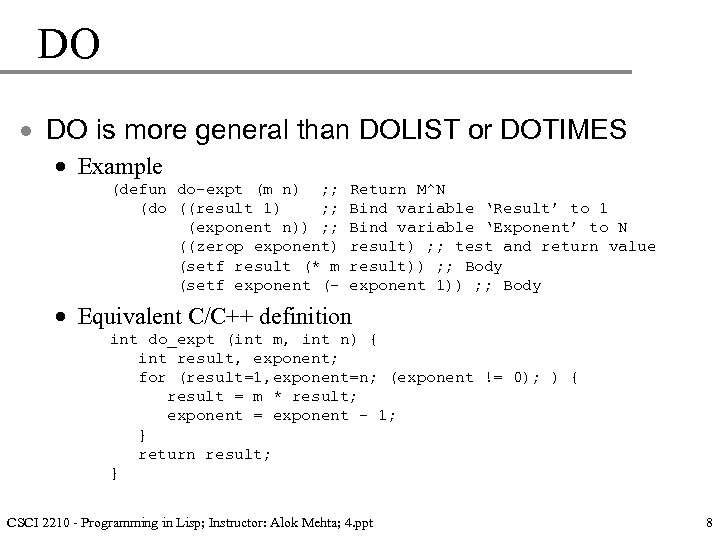

DO · DO is more general than DOLIST or DOTIMES · Example (defun do-expt (m n) ; ; (do ((result 1) ; ; (exponent n)) ; ; ((zerop exponent) (setf result (* m (setf exponent (- Return M^N Bind variable ‘Result’ to 1 Bind variable ‘Exponent’ to N result) ; ; test and return value result)) ; ; Body exponent 1)) ; ; Body · Equivalent C/C++ definition int do_expt (int m, int n) { int result, exponent; for (result=1, exponent=n; (exponent != 0); ) { result = m * result; exponent = exponent - 1; } return result; } CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 8

DO · DO is more general than DOLIST or DOTIMES · Example (defun do-expt (m n) ; ; (do ((result 1) ; ; (exponent n)) ; ; ((zerop exponent) (setf result (* m (setf exponent (- Return M^N Bind variable ‘Result’ to 1 Bind variable ‘Exponent’ to N result) ; ; test and return value result)) ; ; Body exponent 1)) ; ; Body · Equivalent C/C++ definition int do_expt (int m, int n) { int result, exponent; for (result=1, exponent=n; (exponent != 0); ) { result = m * result; exponent = exponent - 1; } return result; } CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 8

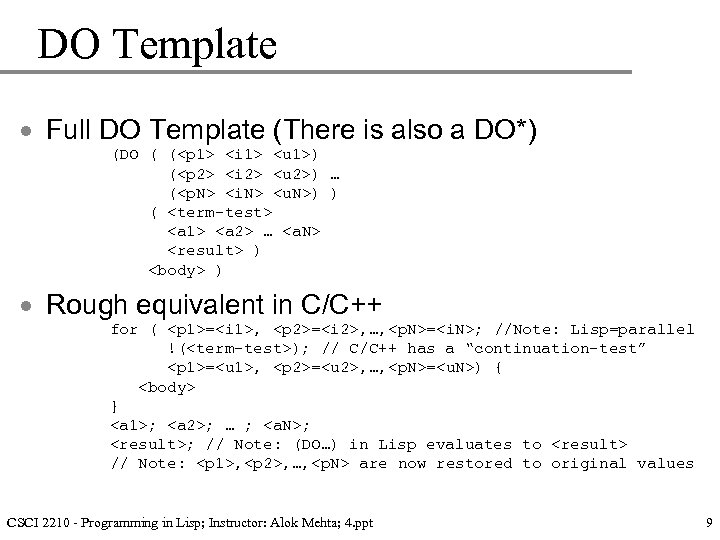

DO Template · Full DO Template (There is also a DO*) (DO ( (

DO Template · Full DO Template (There is also a DO*) (DO ( (

) (

) … ( =, =, …, =, =, …, , , …,

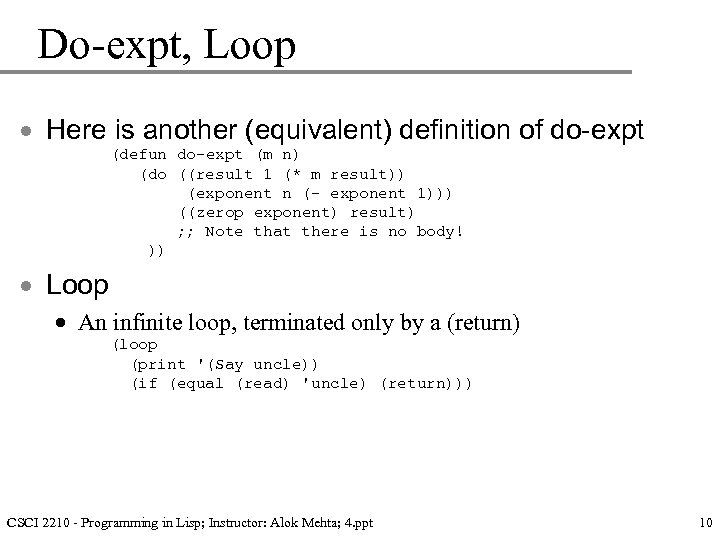

Do-expt, Loop · Here is another (equivalent) definition of do-expt (defun do-expt (m n) (do ((result 1 (* m result)) (exponent n (- exponent 1))) ((zerop exponent) result) ; ; Note that there is no body! )) · Loop · An infinite loop, terminated only by a (return) (loop (print '(Say uncle)) (if (equal (read) 'uncle) (return))) CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 10

Do-expt, Loop · Here is another (equivalent) definition of do-expt (defun do-expt (m n) (do ((result 1 (* m result)) (exponent n (- exponent 1))) ((zerop exponent) result) ; ; Note that there is no body! )) · Loop · An infinite loop, terminated only by a (return) (loop (print '(Say uncle)) (if (equal (read) 'uncle) (return))) CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 10

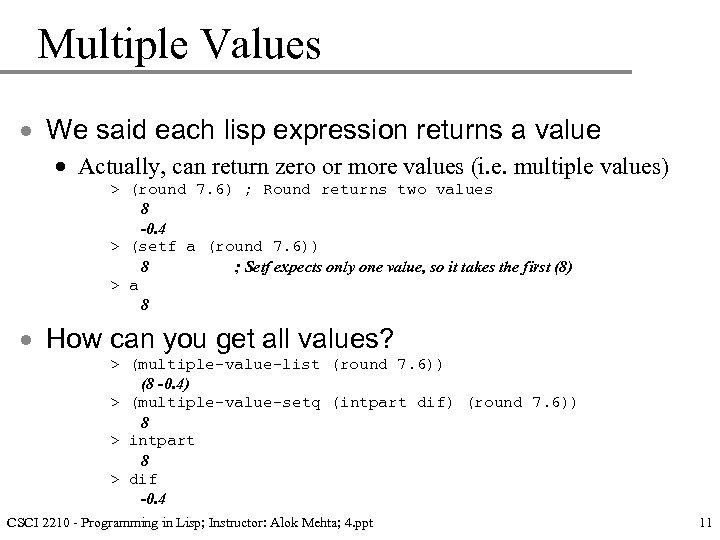

Multiple Values · We said each lisp expression returns a value · Actually, can return zero or more values (i. e. multiple values) > (round 7. 6) ; Round returns two values 8 -0. 4 > (setf a (round 7. 6)) 8 ; Setf expects only one value, so it takes the first (8) > a 8 · How can you get all values? > (multiple-value-list (round 7. 6)) (8 -0. 4) > (multiple-value-setq (intpart dif) (round 7. 6)) 8 > intpart 8 > dif -0. 4 CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 11

Multiple Values · We said each lisp expression returns a value · Actually, can return zero or more values (i. e. multiple values) > (round 7. 6) ; Round returns two values 8 -0. 4 > (setf a (round 7. 6)) 8 ; Setf expects only one value, so it takes the first (8) > a 8 · How can you get all values? > (multiple-value-list (round 7. 6)) (8 -0. 4) > (multiple-value-setq (intpart dif) (round 7. 6)) 8 > intpart 8 > dif -0. 4 CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 11

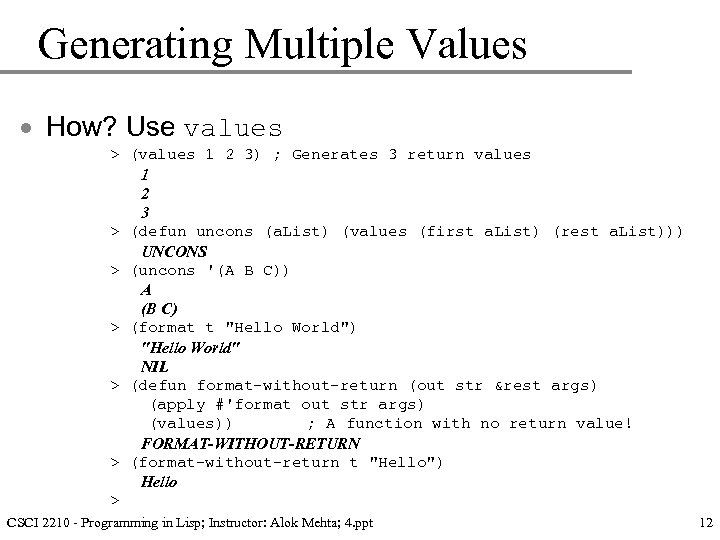

Generating Multiple Values · How? Use values > (values 1 2 3) ; Generates 3 return values 1 2 3 > (defun uncons (a. List) (values (first a. List) (rest a. List))) UNCONS > (uncons '(A B C)) A (B C) > (format t "Hello World") "Hello World" NIL > (defun format-without-return (out str &rest args) (apply #'format out str args) (values)) ; A function with no return value! FORMAT-WITHOUT-RETURN > (format-without-return t "Hello") Hello > CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 12

Generating Multiple Values · How? Use values > (values 1 2 3) ; Generates 3 return values 1 2 3 > (defun uncons (a. List) (values (first a. List) (rest a. List))) UNCONS > (uncons '(A B C)) A (B C) > (format t "Hello World") "Hello World" NIL > (defun format-without-return (out str &rest args) (apply #'format out str args) (values)) ; A function with no return value! FORMAT-WITHOUT-RETURN > (format-without-return t "Hello") Hello > CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 12

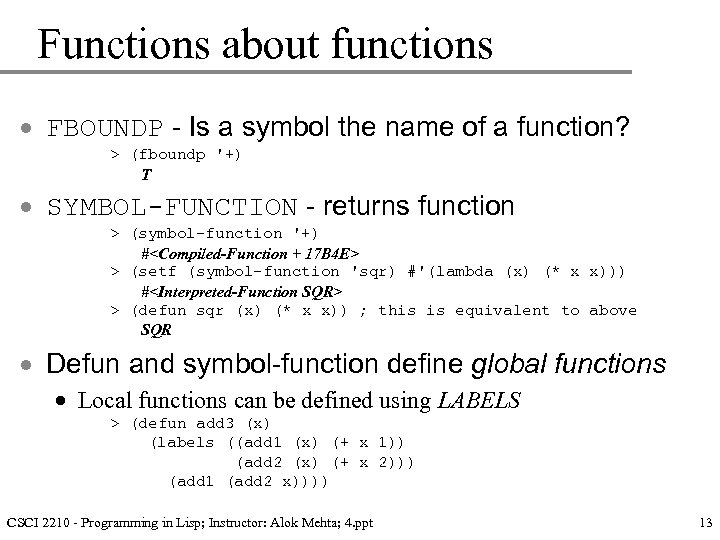

Functions about functions · FBOUNDP - Is a symbol the name of a function? > (fboundp '+) T · SYMBOL-FUNCTION - returns function > (symbol-function '+) #

Functions about functions · FBOUNDP - Is a symbol the name of a function? > (fboundp '+) T · SYMBOL-FUNCTION - returns function > (symbol-function '+) #

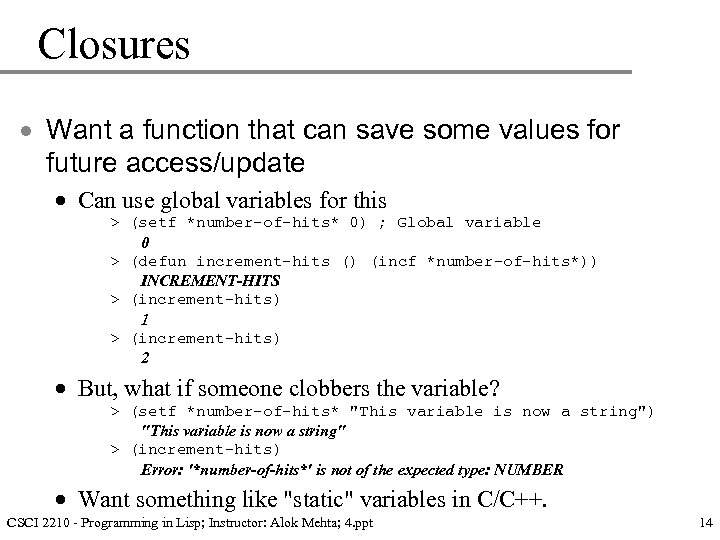

Closures · Want a function that can save some values for future access/update · Can use global variables for this > (setf *number-of-hits* 0) ; Global variable 0 > (defun increment-hits () (incf *number-of-hits*)) INCREMENT-HITS > (increment-hits) 1 > (increment-hits) 2 · But, what if someone clobbers the variable? > (setf *number-of-hits* "This variable is now a string") "This variable is now a string" > (increment-hits) Error: '*number-of-hits*' is not of the expected type: NUMBER · Want something like "static" variables in C/C++. CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 14

Closures · Want a function that can save some values for future access/update · Can use global variables for this > (setf *number-of-hits* 0) ; Global variable 0 > (defun increment-hits () (incf *number-of-hits*)) INCREMENT-HITS > (increment-hits) 1 > (increment-hits) 2 · But, what if someone clobbers the variable? > (setf *number-of-hits* "This variable is now a string") "This variable is now a string" > (increment-hits) Error: '*number-of-hits*' is not of the expected type: NUMBER · Want something like "static" variables in C/C++. CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 14

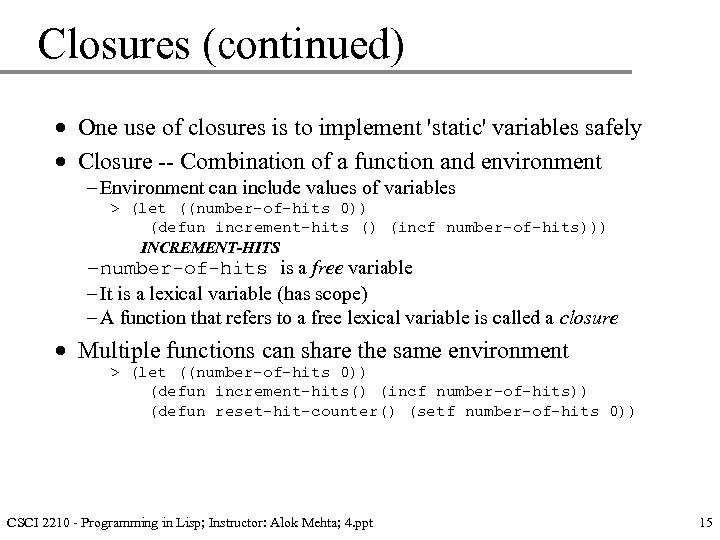

Closures (continued) · One use of closures is to implement 'static' variables safely · Closure -- Combination of a function and environment – Environment can include values of variables > (let ((number-of-hits 0)) (defun increment-hits () (incf number-of-hits))) INCREMENT-HITS – number-of-hits is a free variable – It is a lexical variable (has scope) – A function that refers to a free lexical variable is called a closure · Multiple functions can share the same environment > (let ((number-of-hits 0)) (defun increment-hits() (incf number-of-hits)) (defun reset-hit-counter() (setf number-of-hits 0)) CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 15

Closures (continued) · One use of closures is to implement 'static' variables safely · Closure -- Combination of a function and environment – Environment can include values of variables > (let ((number-of-hits 0)) (defun increment-hits () (incf number-of-hits))) INCREMENT-HITS – number-of-hits is a free variable – It is a lexical variable (has scope) – A function that refers to a free lexical variable is called a closure · Multiple functions can share the same environment > (let ((number-of-hits 0)) (defun increment-hits() (incf number-of-hits)) (defun reset-hit-counter() (setf number-of-hits 0)) CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 15

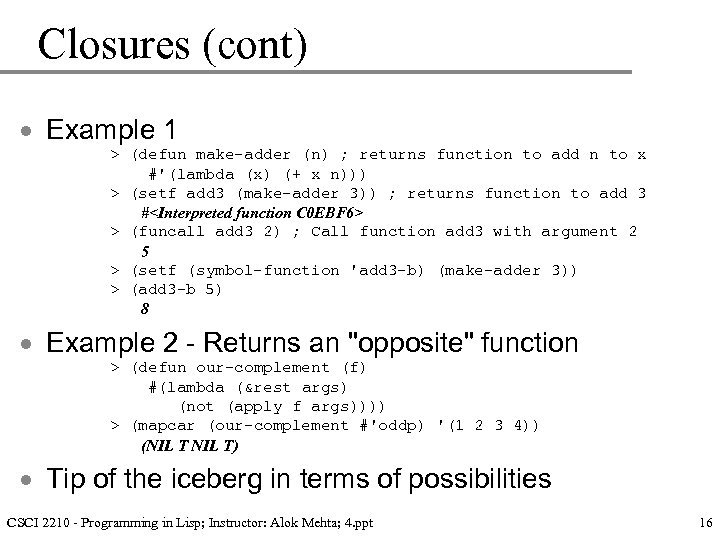

Closures (cont) · Example 1 > (defun make-adder (n) ; returns function to add n to x #'(lambda (x) (+ x n))) > (setf add 3 (make-adder 3)) ; returns function to add 3 #

Closures (cont) · Example 1 > (defun make-adder (n) ; returns function to add n to x #'(lambda (x) (+ x n))) > (setf add 3 (make-adder 3)) ; returns function to add 3 #

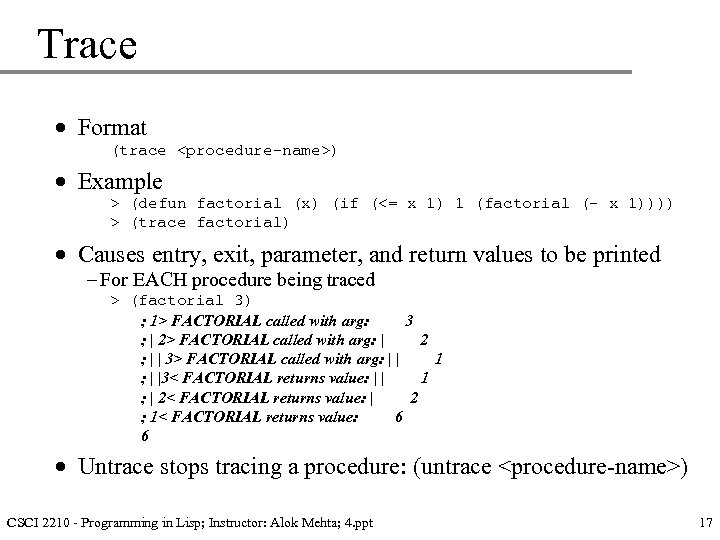

Trace · Format (trace

Trace · Format (trace

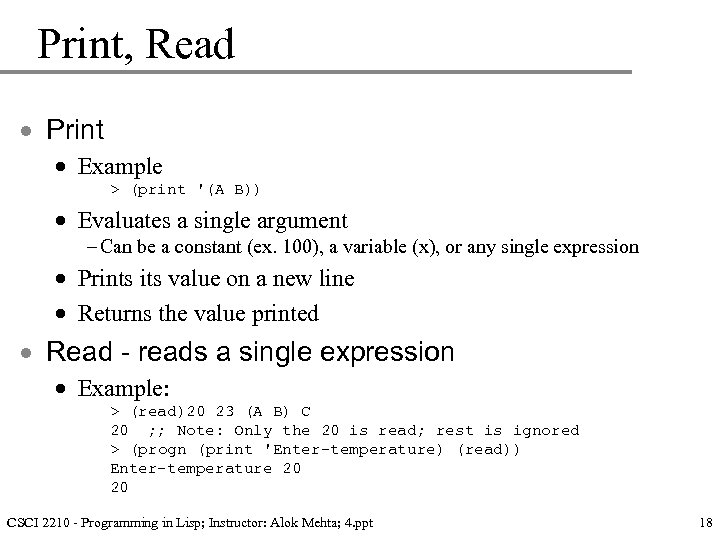

Print, Read · Print · Example > (print '(A B)) · Evaluates a single argument – Can be a constant (ex. 100), a variable (x), or any single expression · Prints its value on a new line · Returns the value printed · Read - reads a single expression · Example: > (read)20 23 (A B) C 20 ; ; Note: Only the 20 is read; rest is ignored > (progn (print 'Enter-temperature) (read)) Enter-temperature 20 20 CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 18

Print, Read · Print · Example > (print '(A B)) · Evaluates a single argument – Can be a constant (ex. 100), a variable (x), or any single expression · Prints its value on a new line · Returns the value printed · Read - reads a single expression · Example: > (read)20 23 (A B) C 20 ; ; Note: Only the 20 is read; rest is ignored > (progn (print 'Enter-temperature) (read)) Enter-temperature 20 20 CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 18

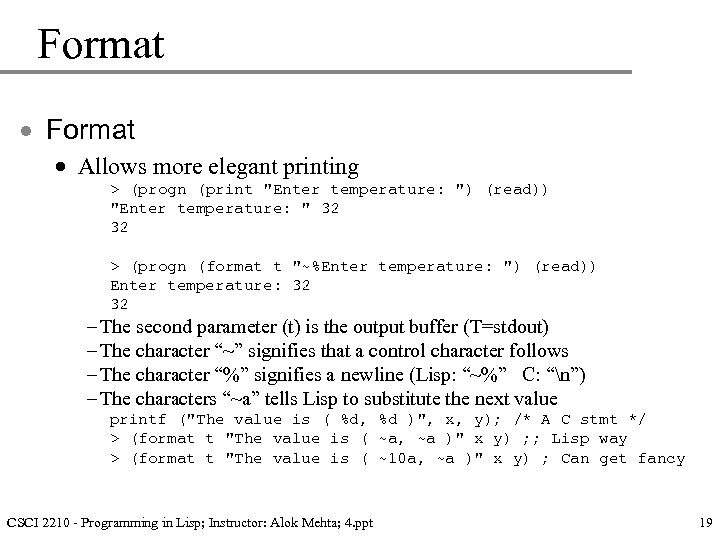

Format · Allows more elegant printing > (progn (print "Enter temperature: ") (read)) "Enter temperature: " 32 32 > (progn (format t "~%Enter temperature: ") (read)) Enter temperature: 32 32 – The second parameter (t) is the output buffer (T=stdout) – The character “~” signifies that a control character follows – The character “%” signifies a newline (Lisp: “~%” C: “n”) – The characters “~a” tells Lisp to substitute the next value printf ("The value is ( %d, %d )", x, y); /* A C stmt */ > (format t "The value is ( ~a, ~a )" x y) ; ; Lisp way > (format t "The value is ( ~10 a, ~a )" x y) ; Can get fancy CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 19

Format · Allows more elegant printing > (progn (print "Enter temperature: ") (read)) "Enter temperature: " 32 32 > (progn (format t "~%Enter temperature: ") (read)) Enter temperature: 32 32 – The second parameter (t) is the output buffer (T=stdout) – The character “~” signifies that a control character follows – The character “%” signifies a newline (Lisp: “~%” C: “n”) – The characters “~a” tells Lisp to substitute the next value printf ("The value is ( %d, %d )", x, y); /* A C stmt */ > (format t "The value is ( ~a, ~a )" x y) ; ; Lisp way > (format t "The value is ( ~10 a, ~a )" x y) ; Can get fancy CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 19

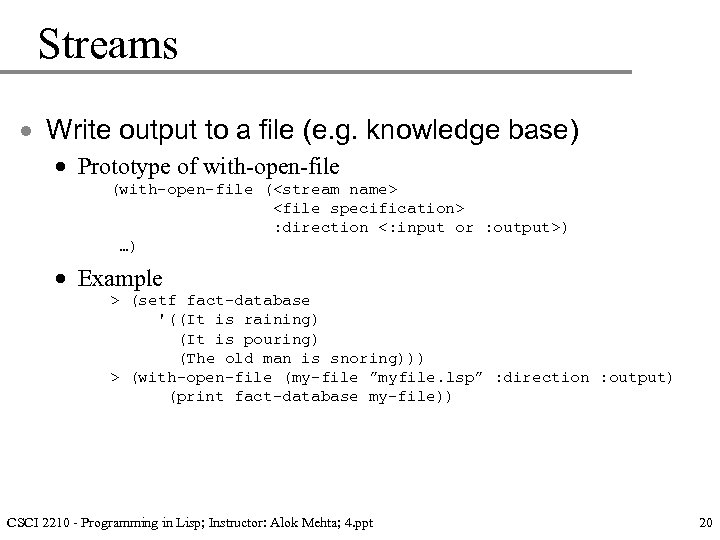

Streams · Write output to a file (e. g. knowledge base) · Prototype of with-open-file (

Streams · Write output to a file (e. g. knowledge base) · Prototype of with-open-file (

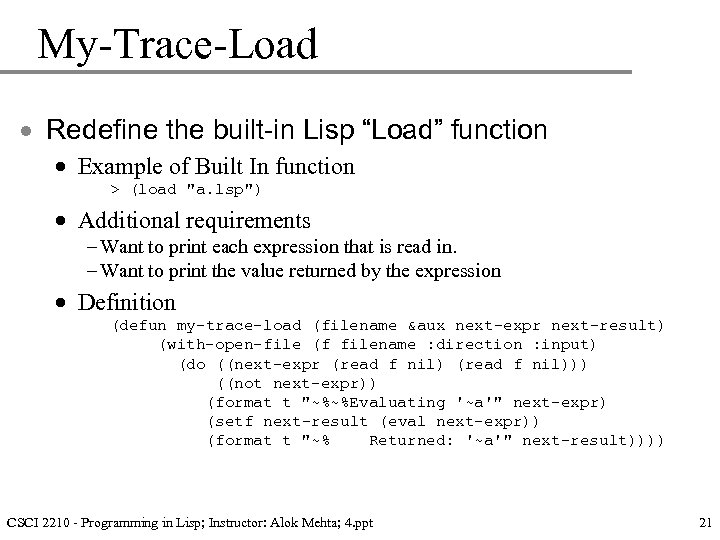

My-Trace-Load · Redefine the built-in Lisp “Load” function · Example of Built In function > (load "a. lsp") · Additional requirements – Want to print each expression that is read in. – Want to print the value returned by the expression · Definition (defun my-trace-load (filename &aux next-expr next-result) (with-open-file (f filename : direction : input) (do ((next-expr (read f nil))) ((not next-expr)) (format t "~%~%Evaluating '~a'" next-expr) (setf next-result (eval next-expr)) (format t "~% Returned: '~a'" next-result)))) CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 21

My-Trace-Load · Redefine the built-in Lisp “Load” function · Example of Built In function > (load "a. lsp") · Additional requirements – Want to print each expression that is read in. – Want to print the value returned by the expression · Definition (defun my-trace-load (filename &aux next-expr next-result) (with-open-file (f filename : direction : input) (do ((next-expr (read f nil))) ((not next-expr)) (format t "~%~%Evaluating '~a'" next-expr) (setf next-result (eval next-expr)) (format t "~% Returned: '~a'" next-result)))) CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 21

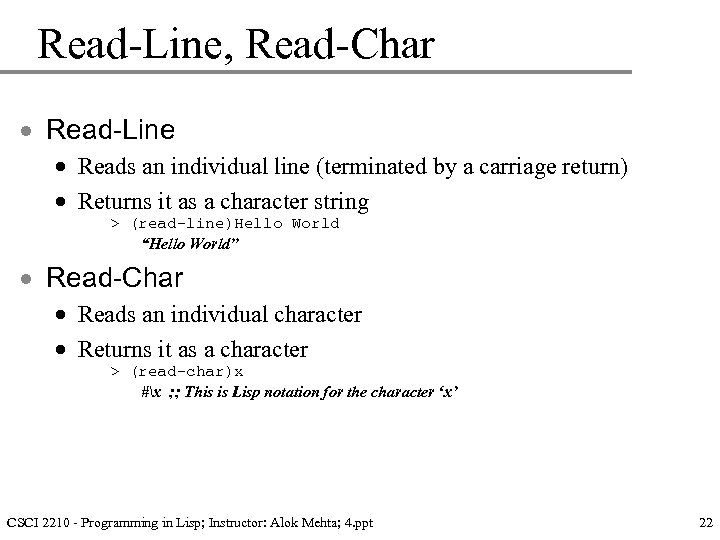

Read-Line, Read-Char · Read-Line · Reads an individual line (terminated by a carriage return) · Returns it as a character string > (read-line)Hello World “Hello World” · Read-Char · Reads an individual character · Returns it as a character > (read-char)x #x ; ; This is Lisp notation for the character ‘x’ CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 22

Read-Line, Read-Char · Read-Line · Reads an individual line (terminated by a carriage return) · Returns it as a character string > (read-line)Hello World “Hello World” · Read-Char · Reads an individual character · Returns it as a character > (read-char)x #x ; ; This is Lisp notation for the character ‘x’ CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 22

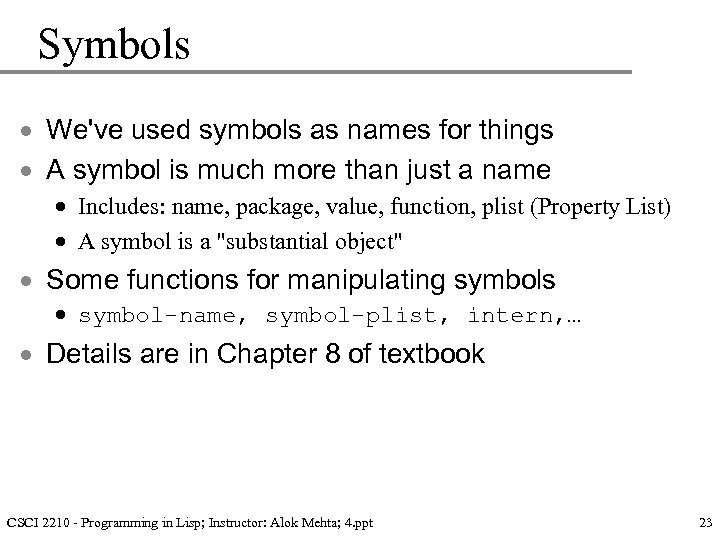

Symbols · We've used symbols as names for things · A symbol is much more than just a name · Includes: name, package, value, function, plist (Property List) · A symbol is a "substantial object" · Some functions for manipulating symbols · symbol-name, symbol-plist, intern, … · Details are in Chapter 8 of textbook CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 23

Symbols · We've used symbols as names for things · A symbol is much more than just a name · Includes: name, package, value, function, plist (Property List) · A symbol is a "substantial object" · Some functions for manipulating symbols · symbol-name, symbol-plist, intern, … · Details are in Chapter 8 of textbook CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 23

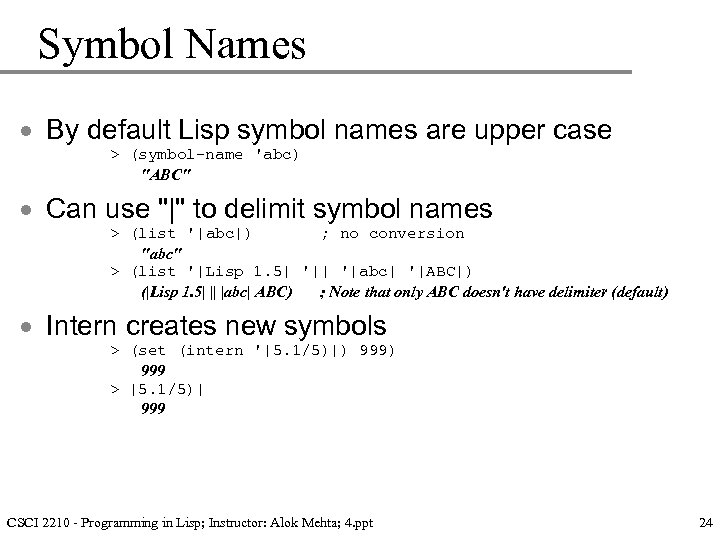

Symbol Names · By default Lisp symbol names are upper case > (symbol-name 'abc) "ABC" · Can use "|" to delimit symbol names > (list '|abc|) ; no conversion "abc" > (list '|Lisp 1. 5| '|abc| '|ABC|) (|Lisp 1. 5| || |abc| ABC) ; Note that only ABC doesn't have delimiter (default) · Intern creates new symbols > (set (intern '|5. 1/5)|) 999 > |5. 1/5)| 999 CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 24

Symbol Names · By default Lisp symbol names are upper case > (symbol-name 'abc) "ABC" · Can use "|" to delimit symbol names > (list '|abc|) ; no conversion "abc" > (list '|Lisp 1. 5| '|abc| '|ABC|) (|Lisp 1. 5| || |abc| ABC) ; Note that only ABC doesn't have delimiter (default) · Intern creates new symbols > (set (intern '|5. 1/5)|) 999 > |5. 1/5)| 999 CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 24

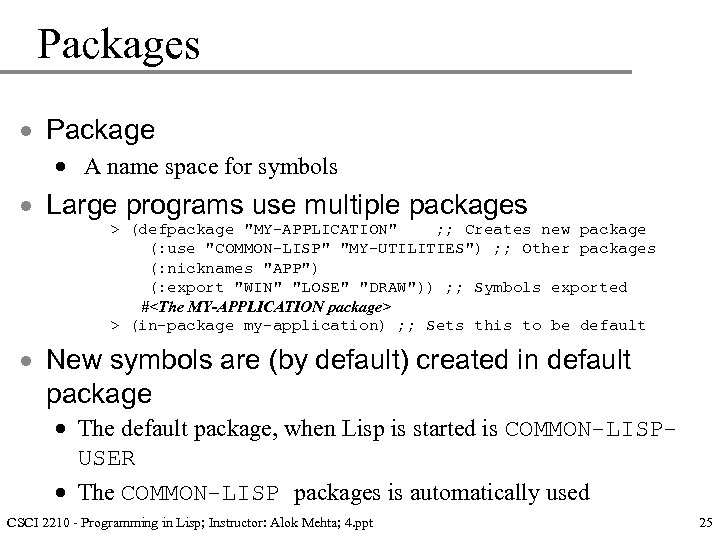

Packages · Package · A name space for symbols · Large programs use multiple packages > (defpackage "MY-APPLICATION" ; ; Creates new package (: use "COMMON-LISP" "MY-UTILITIES") ; ; Other packages (: nicknames "APP") (: export "WIN" "LOSE" "DRAW")) ; ; Symbols exported #

Packages · Package · A name space for symbols · Large programs use multiple packages > (defpackage "MY-APPLICATION" ; ; Creates new package (: use "COMMON-LISP" "MY-UTILITIES") ; ; Other packages (: nicknames "APP") (: export "WIN" "LOSE" "DRAW")) ; ; Symbols exported #

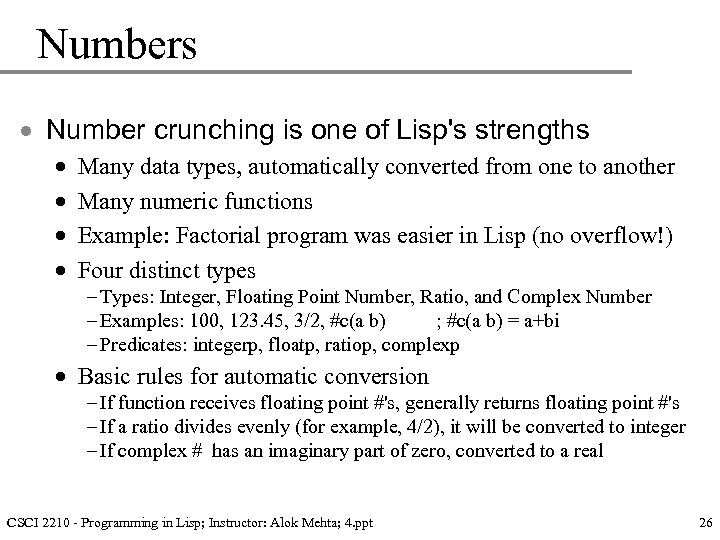

Numbers · Number crunching is one of Lisp's strengths · · Many data types, automatically converted from one to another Many numeric functions Example: Factorial program was easier in Lisp (no overflow!) Four distinct types – Types: Integer, Floating Point Number, Ratio, and Complex Number – Examples: 100, 123. 45, 3/2, #c(a b) ; #c(a b) = a+bi – Predicates: integerp, floatp, ratiop, complexp · Basic rules for automatic conversion – If function receives floating point #'s, generally returns floating point #'s – If a ratio divides evenly (for example, 4/2), it will be converted to integer – If complex # has an imaginary part of zero, converted to a real CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 26

Numbers · Number crunching is one of Lisp's strengths · · Many data types, automatically converted from one to another Many numeric functions Example: Factorial program was easier in Lisp (no overflow!) Four distinct types – Types: Integer, Floating Point Number, Ratio, and Complex Number – Examples: 100, 123. 45, 3/2, #c(a b) ; #c(a b) = a+bi – Predicates: integerp, floatp, ratiop, complexp · Basic rules for automatic conversion – If function receives floating point #'s, generally returns floating point #'s – If a ratio divides evenly (for example, 4/2), it will be converted to integer – If complex # has an imaginary part of zero, converted to a real CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 26

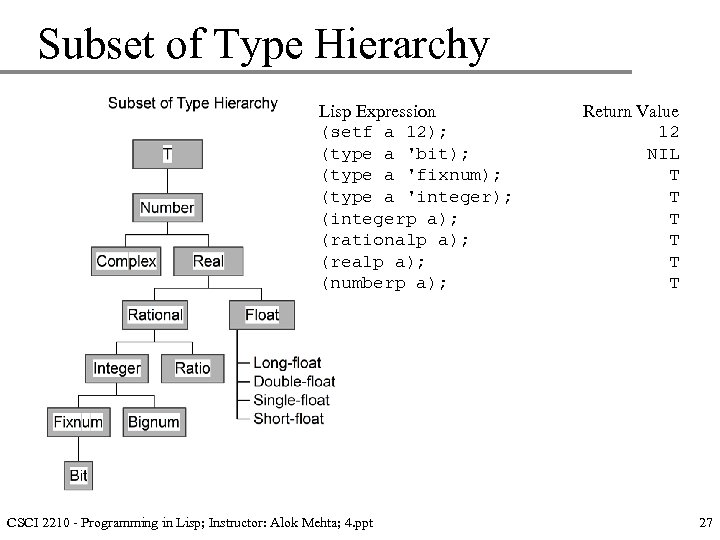

Subset of Type Hierarchy Lisp Expression (setf a 12); (type a 'bit); (type a 'fixnum); (type a 'integer); (integerp a); (rationalp a); (realp a); (numberp a); CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt Return Value 12 NIL T T T 27

Subset of Type Hierarchy Lisp Expression (setf a 12); (type a 'bit); (type a 'fixnum); (type a 'integer); (integerp a); (rationalp a); (realp a); (numberp a); CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt Return Value 12 NIL T T T 27

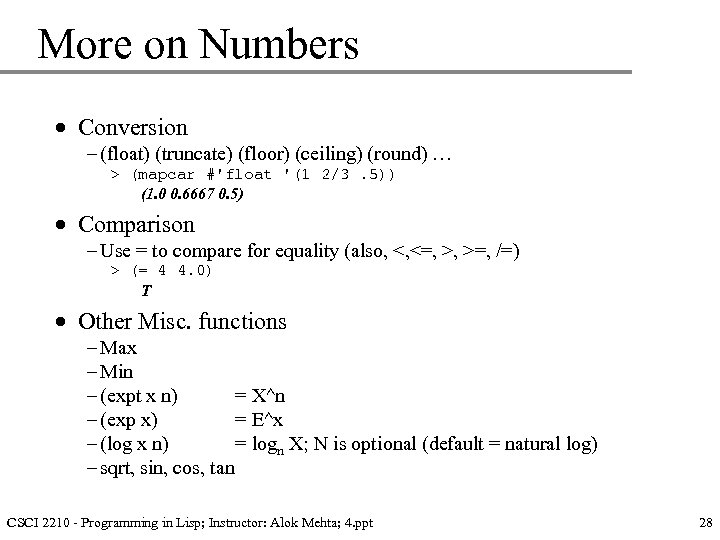

More on Numbers · Conversion – (float) (truncate) (floor) (ceiling) (round) … > (mapcar #'float '(1 2/3. 5)) (1. 0 0. 6667 0. 5) · Comparison – Use = to compare for equality (also, <, <=, >, >=, /=) > (= 4 4. 0) T · Other Misc. functions – Max – Min – (expt x n) = X^n – (exp x) = E^x – (log x n) = logn X; N is optional (default = natural log) – sqrt, sin, cos, tan CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 28

More on Numbers · Conversion – (float) (truncate) (floor) (ceiling) (round) … > (mapcar #'float '(1 2/3. 5)) (1. 0 0. 6667 0. 5) · Comparison – Use = to compare for equality (also, <, <=, >, >=, /=) > (= 4 4. 0) T · Other Misc. functions – Max – Min – (expt x n) = X^n – (exp x) = E^x – (log x n) = logn X; N is optional (default = natural log) – sqrt, sin, cos, tan CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 28

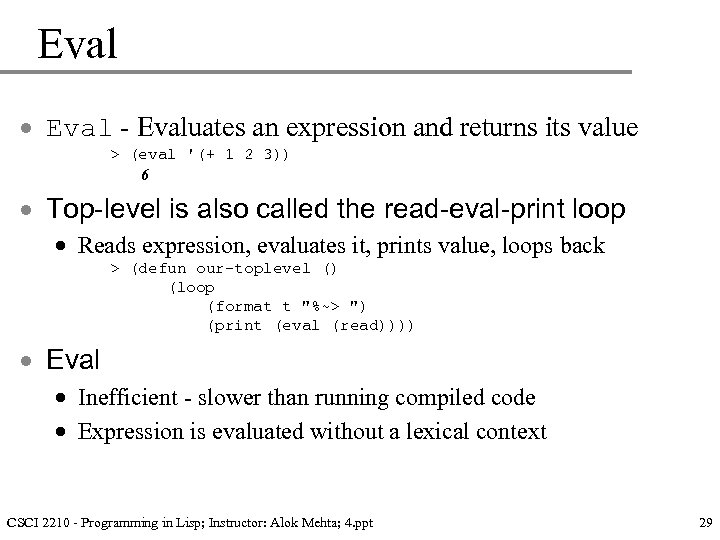

Eval · Eval - Evaluates an expression and returns its value > (eval '(+ 1 2 3)) 6 · Top-level is also called the read-eval-print loop · Reads expression, evaluates it, prints value, loops back > (defun our-toplevel () (loop (format t "%~> ") (print (eval (read)))) · Eval · Inefficient - slower than running compiled code · Expression is evaluated without a lexical context CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 29

Eval · Eval - Evaluates an expression and returns its value > (eval '(+ 1 2 3)) 6 · Top-level is also called the read-eval-print loop · Reads expression, evaluates it, prints value, loops back > (defun our-toplevel () (loop (format t "%~> ") (print (eval (read)))) · Eval · Inefficient - slower than running compiled code · Expression is evaluated without a lexical context CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 29

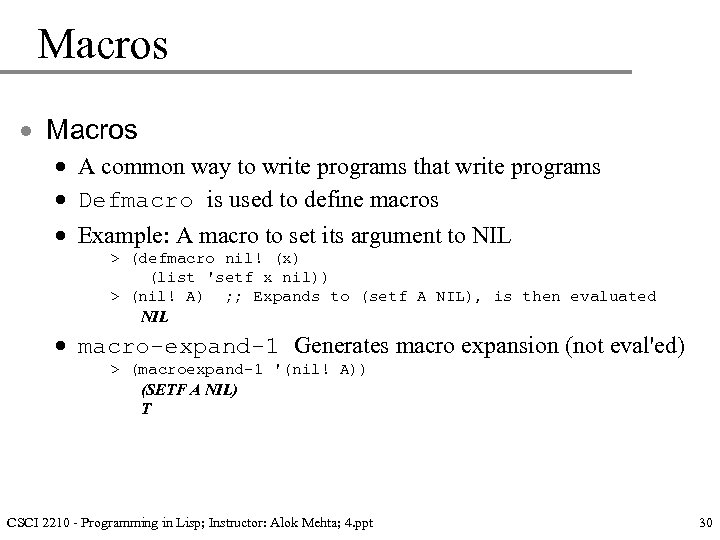

Macros · A common way to write programs that write programs · Defmacro is used to define macros · Example: A macro to set its argument to NIL > (defmacro nil! (x) (list 'setf x nil)) > (nil! A) ; ; Expands to (setf A NIL), is then evaluated NIL · macro-expand-1 Generates macro expansion (not eval'ed) > (macroexpand-1 '(nil! A)) (SETF A NIL) T CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 30

Macros · A common way to write programs that write programs · Defmacro is used to define macros · Example: A macro to set its argument to NIL > (defmacro nil! (x) (list 'setf x nil)) > (nil! A) ; ; Expands to (setf A NIL), is then evaluated NIL · macro-expand-1 Generates macro expansion (not eval'ed) > (macroexpand-1 '(nil! A)) (SETF A NIL) T CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 30

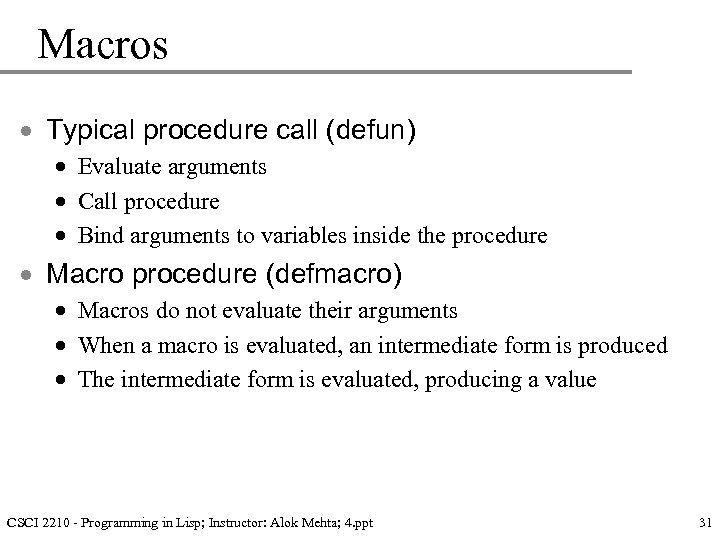

Macros · Typical procedure call (defun) · Evaluate arguments · Call procedure · Bind arguments to variables inside the procedure · Macro procedure (defmacro) · Macros do not evaluate their arguments · When a macro is evaluated, an intermediate form is produced · The intermediate form is evaluated, producing a value CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 31

Macros · Typical procedure call (defun) · Evaluate arguments · Call procedure · Bind arguments to variables inside the procedure · Macro procedure (defmacro) · Macros do not evaluate their arguments · When a macro is evaluated, an intermediate form is produced · The intermediate form is evaluated, producing a value CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 31

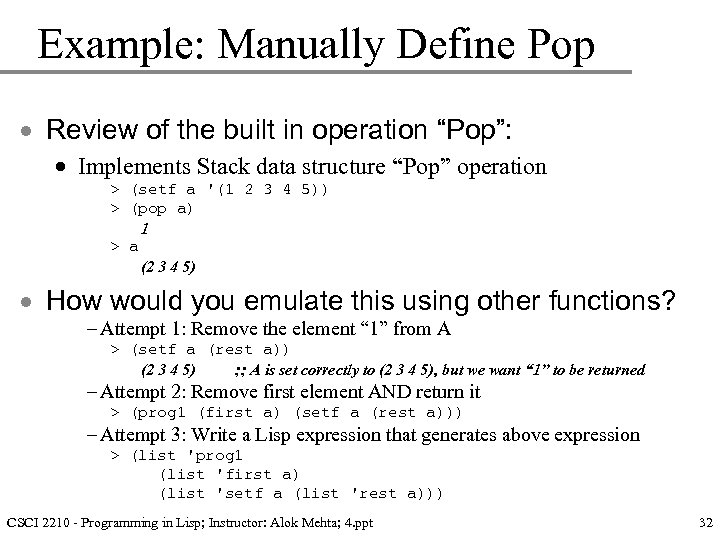

Example: Manually Define Pop · Review of the built in operation “Pop”: · Implements Stack data structure “Pop” operation > (setf a '(1 2 3 4 5)) > (pop a) 1 > a (2 3 4 5) · How would you emulate this using other functions? – Attempt 1: Remove the element “ 1” from A > (setf a (rest a)) (2 3 4 5) ; ; A is set correctly to (2 3 4 5), but we want “ 1” to be returned – Attempt 2: Remove first element AND return it > (prog 1 (first a) (setf a (rest a))) – Attempt 3: Write a Lisp expression that generates above expression > (list 'prog 1 (list 'first a) (list 'setf a (list 'rest a))) CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 32

Example: Manually Define Pop · Review of the built in operation “Pop”: · Implements Stack data structure “Pop” operation > (setf a '(1 2 3 4 5)) > (pop a) 1 > a (2 3 4 5) · How would you emulate this using other functions? – Attempt 1: Remove the element “ 1” from A > (setf a (rest a)) (2 3 4 5) ; ; A is set correctly to (2 3 4 5), but we want “ 1” to be returned – Attempt 2: Remove first element AND return it > (prog 1 (first a) (setf a (rest a))) – Attempt 3: Write a Lisp expression that generates above expression > (list 'prog 1 (list 'first a) (list 'setf a (list 'rest a))) CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 32

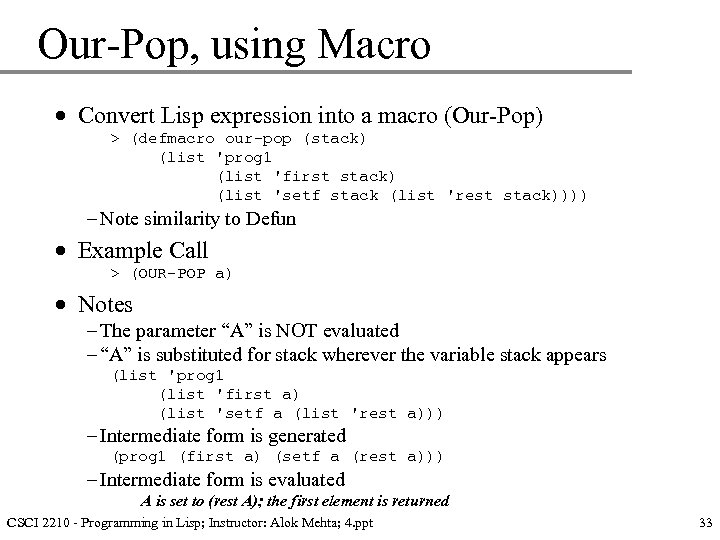

Our-Pop, using Macro · Convert Lisp expression into a macro (Our-Pop) > (defmacro our-pop (stack) (list 'prog 1 (list 'first stack) (list 'setf stack (list 'rest stack)))) – Note similarity to Defun · Example Call > (OUR-POP a) · Notes – The parameter “A” is NOT evaluated – “A” is substituted for stack wherever the variable stack appears (list 'prog 1 (list 'first a) (list 'setf a (list 'rest a))) – Intermediate form is generated (prog 1 (first a) (setf a (rest a))) – Intermediate form is evaluated A is set to (rest A); the first element is returned CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 33

Our-Pop, using Macro · Convert Lisp expression into a macro (Our-Pop) > (defmacro our-pop (stack) (list 'prog 1 (list 'first stack) (list 'setf stack (list 'rest stack)))) – Note similarity to Defun · Example Call > (OUR-POP a) · Notes – The parameter “A” is NOT evaluated – “A” is substituted for stack wherever the variable stack appears (list 'prog 1 (list 'first a) (list 'setf a (list 'rest a))) – Intermediate form is generated (prog 1 (first a) (setf a (rest a))) – Intermediate form is evaluated A is set to (rest A); the first element is returned CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 33

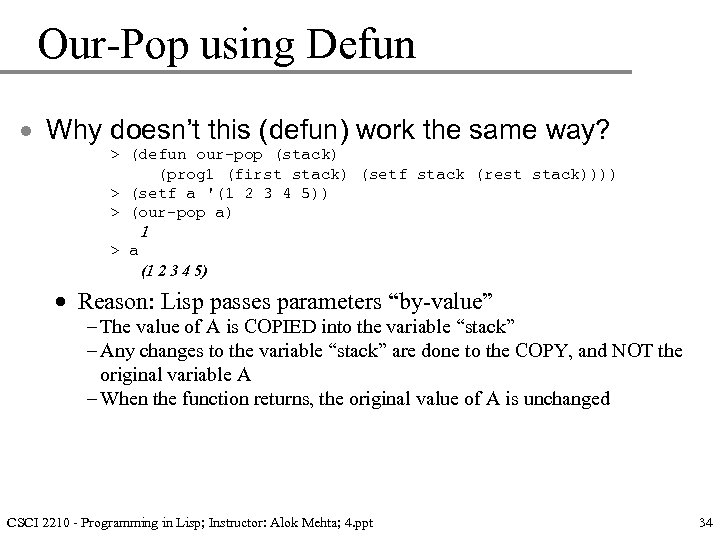

Our-Pop using Defun · Why doesn’t this (defun) work the same way? > (defun our-pop (stack) (prog 1 (first stack) (setf stack (rest stack)))) > (setf a '(1 2 3 4 5)) > (our-pop a) 1 > a (1 2 3 4 5) · Reason: Lisp passes parameters “by-value” – The value of A is COPIED into the variable “stack” – Any changes to the variable “stack” are done to the COPY, and NOT the original variable A – When the function returns, the original value of A is unchanged CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 34

Our-Pop using Defun · Why doesn’t this (defun) work the same way? > (defun our-pop (stack) (prog 1 (first stack) (setf stack (rest stack)))) > (setf a '(1 2 3 4 5)) > (our-pop a) 1 > a (1 2 3 4 5) · Reason: Lisp passes parameters “by-value” – The value of A is COPIED into the variable “stack” – Any changes to the variable “stack” are done to the COPY, and NOT the original variable A – When the function returns, the original value of A is unchanged CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 34

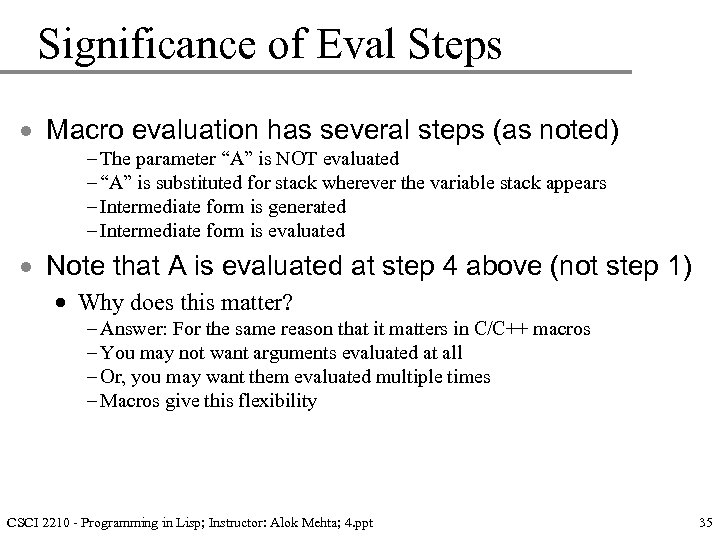

Significance of Eval Steps · Macro evaluation has several steps (as noted) – The parameter “A” is NOT evaluated – “A” is substituted for stack wherever the variable stack appears – Intermediate form is generated – Intermediate form is evaluated · Note that A is evaluated at step 4 above (not step 1) · Why does this matter? – Answer: For the same reason that it matters in C/C++ macros – You may not want arguments evaluated at all – Or, you may want them evaluated multiple times – Macros give this flexibility CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 35

Significance of Eval Steps · Macro evaluation has several steps (as noted) – The parameter “A” is NOT evaluated – “A” is substituted for stack wherever the variable stack appears – Intermediate form is generated – Intermediate form is evaluated · Note that A is evaluated at step 4 above (not step 1) · Why does this matter? – Answer: For the same reason that it matters in C/C++ macros – You may not want arguments evaluated at all – Or, you may want them evaluated multiple times – Macros give this flexibility CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 35

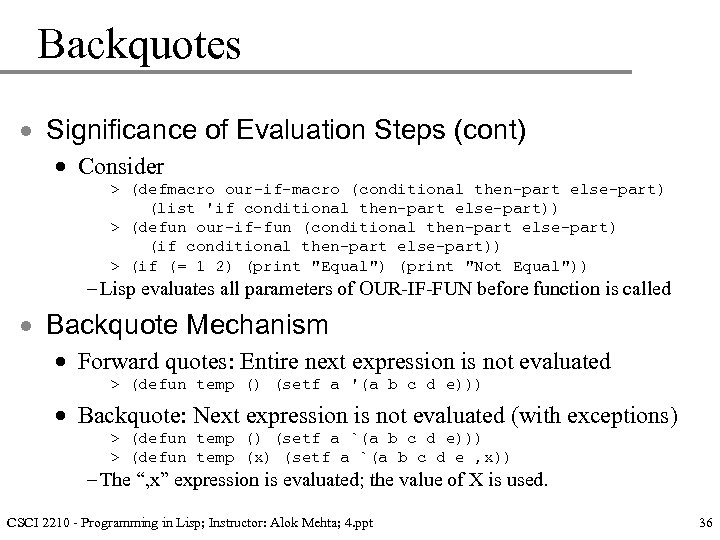

Backquotes · Significance of Evaluation Steps (cont) · Consider > (defmacro our-if-macro (conditional then-part else-part) (list 'if conditional then-part else-part)) > (defun our-if-fun (conditional then-part else-part) (if conditional then-part else-part)) > (if (= 1 2) (print "Equal") (print "Not Equal")) – Lisp evaluates all parameters of OUR-IF-FUN before function is called · Backquote Mechanism · Forward quotes: Entire next expression is not evaluated > (defun temp () (setf a '(a b c d e))) · Backquote: Next expression is not evaluated (with exceptions) > (defun temp () (setf a `(a b c d e))) > (defun temp (x) (setf a `(a b c d e , x)) – The “, x” expression is evaluated; the value of X is used. CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 36

Backquotes · Significance of Evaluation Steps (cont) · Consider > (defmacro our-if-macro (conditional then-part else-part) (list 'if conditional then-part else-part)) > (defun our-if-fun (conditional then-part else-part) (if conditional then-part else-part)) > (if (= 1 2) (print "Equal") (print "Not Equal")) – Lisp evaluates all parameters of OUR-IF-FUN before function is called · Backquote Mechanism · Forward quotes: Entire next expression is not evaluated > (defun temp () (setf a '(a b c d e))) · Backquote: Next expression is not evaluated (with exceptions) > (defun temp () (setf a `(a b c d e))) > (defun temp (x) (setf a `(a b c d e , x)) – The “, x” expression is evaluated; the value of X is used. CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 36

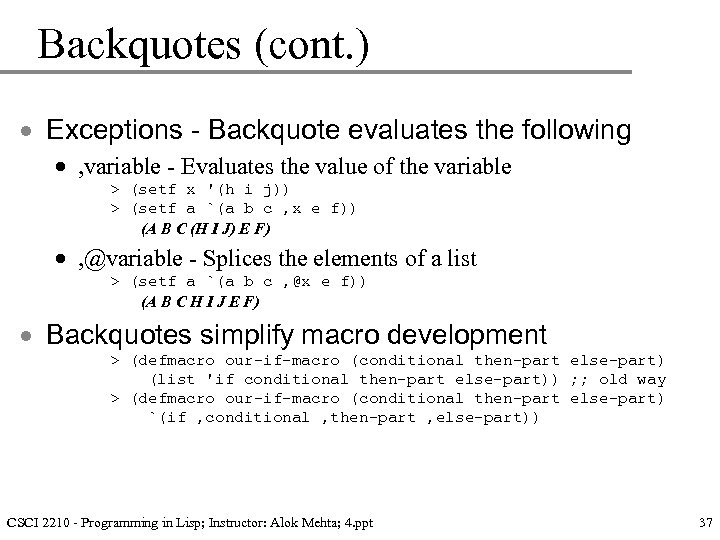

Backquotes (cont. ) · Exceptions - Backquote evaluates the following · , variable - Evaluates the value of the variable > (setf x '(h i j)) > (setf a `(a b c , x e f)) (A B C (H I J) E F) · , @variable - Splices the elements of a list > (setf a `(a b c , @x e f)) (A B C H I J E F) · Backquotes simplify macro development > (defmacro our-if-macro (conditional then-part else-part) (list 'if conditional then-part else-part)) ; ; old way > (defmacro our-if-macro (conditional then-part else-part) `(if , conditional , then-part , else-part)) CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 37

Backquotes (cont. ) · Exceptions - Backquote evaluates the following · , variable - Evaluates the value of the variable > (setf x '(h i j)) > (setf a `(a b c , x e f)) (A B C (H I J) E F) · , @variable - Splices the elements of a list > (setf a `(a b c , @x e f)) (A B C H I J E F) · Backquotes simplify macro development > (defmacro our-if-macro (conditional then-part else-part) (list 'if conditional then-part else-part)) ; ; old way > (defmacro our-if-macro (conditional then-part else-part) `(if , conditional , then-part , else-part)) CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 37

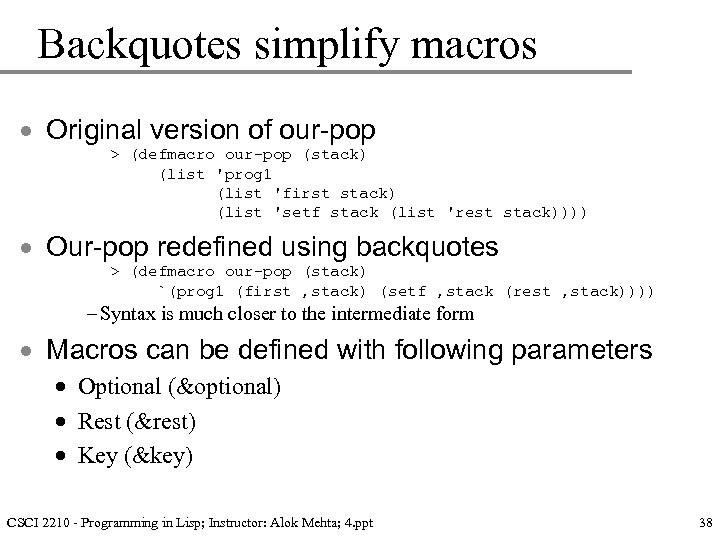

Backquotes simplify macros · Original version of our-pop > (defmacro our-pop (stack) (list 'prog 1 (list 'first stack) (list 'setf stack (list 'rest stack)))) · Our-pop redefined using backquotes > (defmacro our-pop (stack) `(prog 1 (first , stack) (setf , stack (rest , stack)))) – Syntax is much closer to the intermediate form · Macros can be defined with following parameters · Optional (&optional) · Rest (&rest) · Key (&key) CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 38

Backquotes simplify macros · Original version of our-pop > (defmacro our-pop (stack) (list 'prog 1 (list 'first stack) (list 'setf stack (list 'rest stack)))) · Our-pop redefined using backquotes > (defmacro our-pop (stack) `(prog 1 (first , stack) (setf , stack (rest , stack)))) – Syntax is much closer to the intermediate form · Macros can be defined with following parameters · Optional (&optional) · Rest (&rest) · Key (&key) CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 38

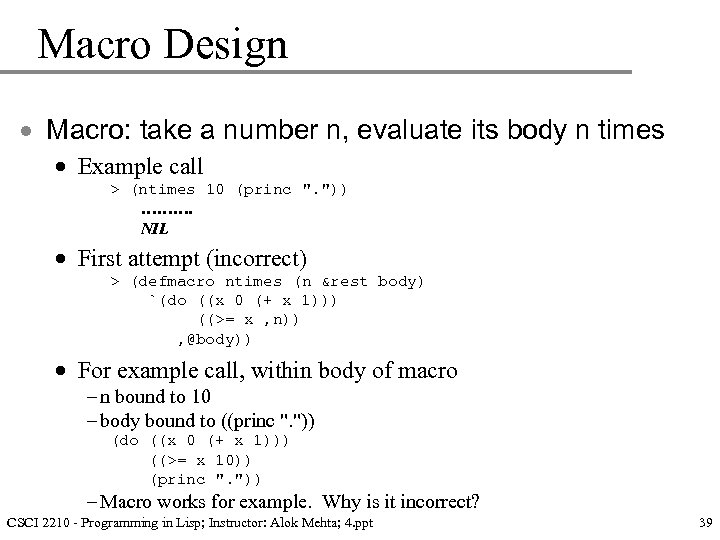

Macro Design · Macro: take a number n, evaluate its body n times · Example call > (ntimes 10 (princ ". ")) ………. NIL · First attempt (incorrect) > (defmacro ntimes (n &rest body) `(do ((x 0 (+ x 1))) ((>= x , n)) , @body)) · For example call, within body of macro – n bound to 10 – body bound to ((princ ". ")) (do ((x 0 (+ x 1))) ((>= x 10)) (princ ". ")) – Macro works for example. Why is it incorrect? CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 39

Macro Design · Macro: take a number n, evaluate its body n times · Example call > (ntimes 10 (princ ". ")) ………. NIL · First attempt (incorrect) > (defmacro ntimes (n &rest body) `(do ((x 0 (+ x 1))) ((>= x , n)) , @body)) · For example call, within body of macro – n bound to 10 – body bound to ((princ ". ")) (do ((x 0 (+ x 1))) ((>= x 10)) (princ ". ")) – Macro works for example. Why is it incorrect? CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 39

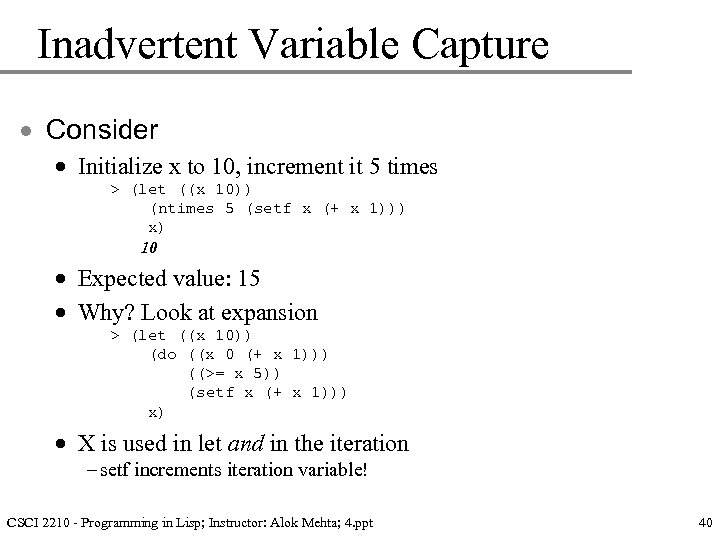

Inadvertent Variable Capture · Consider · Initialize x to 10, increment it 5 times > (let ((x 10)) (ntimes 5 (setf x (+ x 1))) x) 10 · Expected value: 15 · Why? Look at expansion > (let ((x 10)) (do ((x 0 (+ x 1))) ((>= x 5)) (setf x (+ x 1))) x) · X is used in let and in the iteration – setf increments iteration variable! CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 40

Inadvertent Variable Capture · Consider · Initialize x to 10, increment it 5 times > (let ((x 10)) (ntimes 5 (setf x (+ x 1))) x) 10 · Expected value: 15 · Why? Look at expansion > (let ((x 10)) (do ((x 0 (+ x 1))) ((>= x 5)) (setf x (+ x 1))) x) · X is used in let and in the iteration – setf increments iteration variable! CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 40

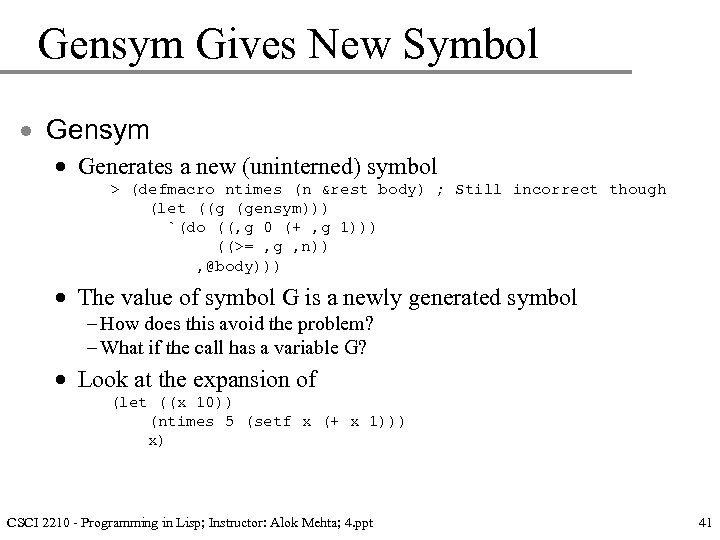

Gensym Gives New Symbol · Gensym · Generates a new (uninterned) symbol > (defmacro ntimes (n &rest body) ; Still incorrect though (let ((g (gensym))) `(do ((, g 0 (+ , g 1))) ((>= , g , n)) , @body))) · The value of symbol G is a newly generated symbol – How does this avoid the problem? – What if the call has a variable G? · Look at the expansion of (let ((x 10)) (ntimes 5 (setf x (+ x 1))) x) CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 41

Gensym Gives New Symbol · Gensym · Generates a new (uninterned) symbol > (defmacro ntimes (n &rest body) ; Still incorrect though (let ((g (gensym))) `(do ((, g 0 (+ , g 1))) ((>= , g , n)) , @body))) · The value of symbol G is a newly generated symbol – How does this avoid the problem? – What if the call has a variable G? · Look at the expansion of (let ((x 10)) (ntimes 5 (setf x (+ x 1))) x) CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 41

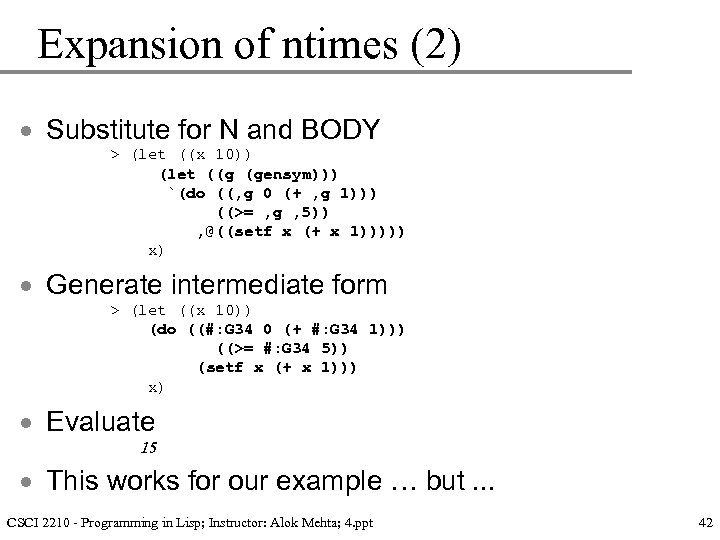

Expansion of ntimes (2) · Substitute for N and BODY > (let ((x 10)) (let ((g (gensym))) `(do ((, g 0 (+ , g 1))) ((>= , g , 5)) , @((setf x (+ x 1))))) x) · Generate intermediate form > (let ((x 10)) (do ((#: G 34 0 (+ #: G 34 1))) ((>= #: G 34 5)) (setf x (+ x 1))) x) · Evaluate 15 · This works for our example … but. . . CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 42

Expansion of ntimes (2) · Substitute for N and BODY > (let ((x 10)) (let ((g (gensym))) `(do ((, g 0 (+ , g 1))) ((>= , g , 5)) , @((setf x (+ x 1))))) x) · Generate intermediate form > (let ((x 10)) (do ((#: G 34 0 (+ #: G 34 1))) ((>= #: G 34 5)) (setf x (+ x 1))) x) · Evaluate 15 · This works for our example … but. . . CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 42

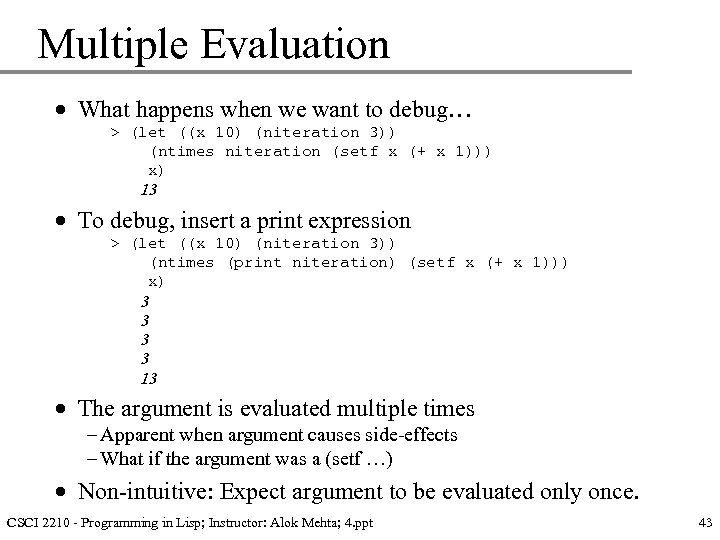

Multiple Evaluation · What happens when we want to debug… > (let ((x 10) (niteration 3)) (ntimes niteration (setf x (+ x 1))) x) 13 · To debug, insert a print expression > (let ((x 10) (niteration 3)) (ntimes (print niteration) (setf x (+ x 1))) x) 3 3 13 · The argument is evaluated multiple times – Apparent when argument causes side-effects – What if the argument was a (setf …) · Non-intuitive: Expect argument to be evaluated only once. CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 43

Multiple Evaluation · What happens when we want to debug… > (let ((x 10) (niteration 3)) (ntimes niteration (setf x (+ x 1))) x) 13 · To debug, insert a print expression > (let ((x 10) (niteration 3)) (ntimes (print niteration) (setf x (+ x 1))) x) 3 3 13 · The argument is evaluated multiple times – Apparent when argument causes side-effects – What if the argument was a (setf …) · Non-intuitive: Expect argument to be evaluated only once. CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 43

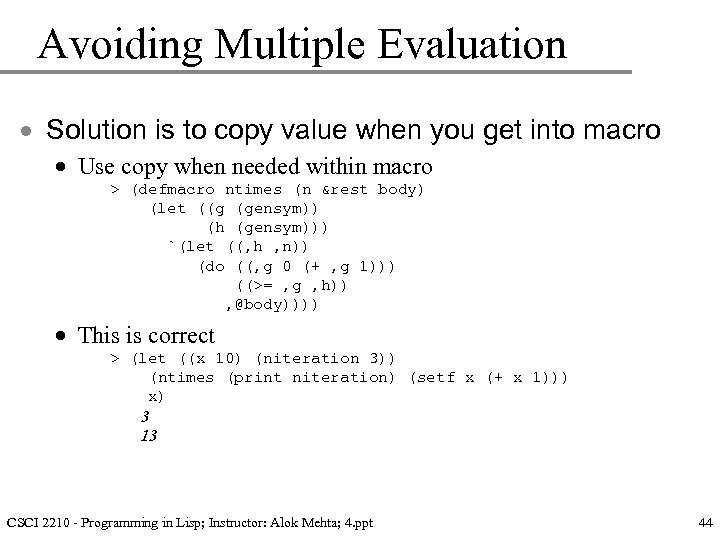

Avoiding Multiple Evaluation · Solution is to copy value when you get into macro · Use copy when needed within macro > (defmacro ntimes (n &rest body) (let ((g (gensym)) (h (gensym))) `(let ((, h , n)) (do ((, g 0 (+ , g 1))) ((>= , g , h)) , @body)))) · This is correct > (let ((x 10) (niteration 3)) (ntimes (print niteration) (setf x (+ x 1))) x) 3 13 CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 44

Avoiding Multiple Evaluation · Solution is to copy value when you get into macro · Use copy when needed within macro > (defmacro ntimes (n &rest body) (let ((g (gensym)) (h (gensym))) `(let ((, h , n)) (do ((, g 0 (+ , g 1))) ((>= , g , h)) , @body)))) · This is correct > (let ((x 10) (niteration 3)) (ntimes (print niteration) (setf x (+ x 1))) x) 3 13 CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 44

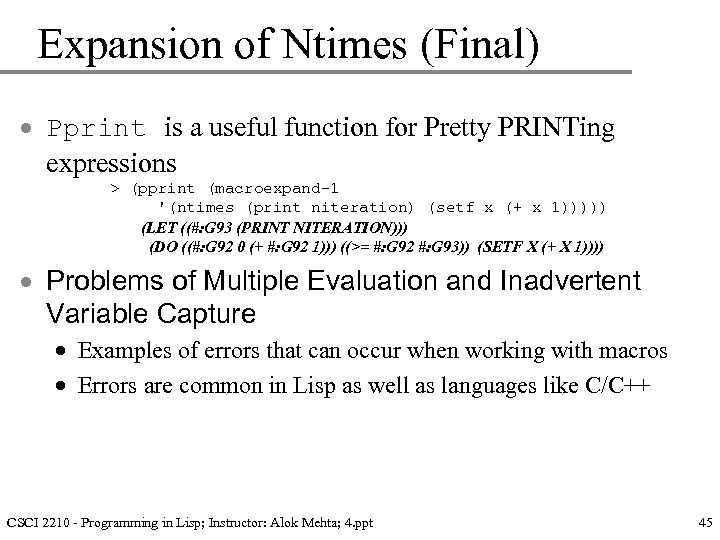

Expansion of Ntimes (Final) · Pprint is a useful function for Pretty PRINTing expressions > (pprint (macroexpand-1 '(ntimes (print niteration) (setf x (+ x 1))))) (LET ((#: G 93 (PRINT NITERATION))) (DO ((#: G 92 0 (+ #: G 92 1))) ((>= #: G 92 #: G 93)) (SETF X (+ X 1)))) · Problems of Multiple Evaluation and Inadvertent Variable Capture · Examples of errors that can occur when working with macros · Errors are common in Lisp as well as languages like C/C++ CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 45

Expansion of Ntimes (Final) · Pprint is a useful function for Pretty PRINTing expressions > (pprint (macroexpand-1 '(ntimes (print niteration) (setf x (+ x 1))))) (LET ((#: G 93 (PRINT NITERATION))) (DO ((#: G 92 0 (+ #: G 92 1))) ((>= #: G 92 #: G 93)) (SETF X (+ X 1)))) · Problems of Multiple Evaluation and Inadvertent Variable Capture · Examples of errors that can occur when working with macros · Errors are common in Lisp as well as languages like C/C++ CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 45

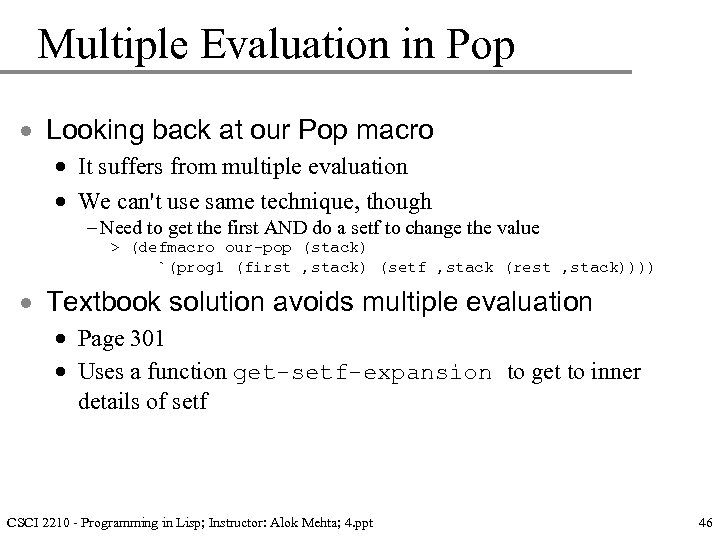

Multiple Evaluation in Pop · Looking back at our Pop macro · It suffers from multiple evaluation · We can't use same technique, though – Need to get the first AND do a setf to change the value > (defmacro our-pop (stack) `(prog 1 (first , stack) (setf , stack (rest , stack)))) · Textbook solution avoids multiple evaluation · Page 301 · Uses a function get-setf-expansion to get to inner details of setf CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 46

Multiple Evaluation in Pop · Looking back at our Pop macro · It suffers from multiple evaluation · We can't use same technique, though – Need to get the first AND do a setf to change the value > (defmacro our-pop (stack) `(prog 1 (first , stack) (setf , stack (rest , stack)))) · Textbook solution avoids multiple evaluation · Page 301 · Uses a function get-setf-expansion to get to inner details of setf CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 46

Case Study: Expert Systems · Overview of using Lisp for · Symbolic Pattern Matching · Rule Based Expert Systems and Forward Chaining · Backward Chaining and PROLOG · Motivational example · Given: – A set of Facts – A set of Rules · Desired result – Answer complex questions and queries CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 47

Case Study: Expert Systems · Overview of using Lisp for · Symbolic Pattern Matching · Rule Based Expert Systems and Forward Chaining · Backward Chaining and PROLOG · Motivational example · Given: – A set of Facts – A set of Rules · Desired result – Answer complex questions and queries CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 47

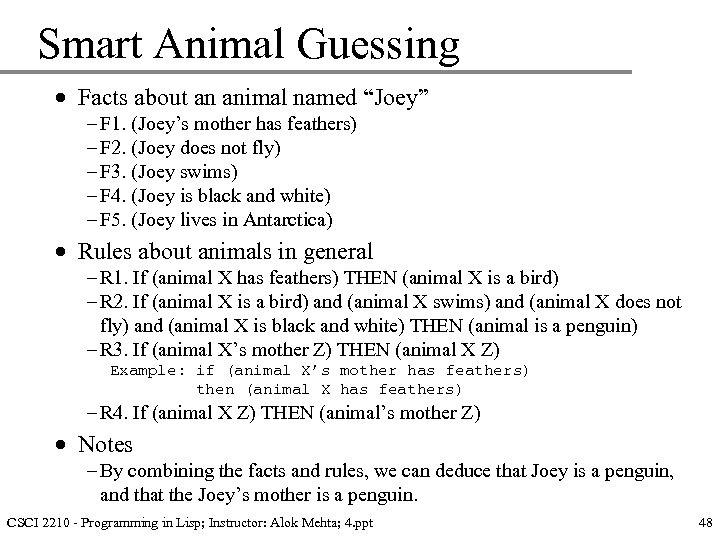

Smart Animal Guessing · Facts about an animal named “Joey” – F 1. (Joey’s mother has feathers) – F 2. (Joey does not fly) – F 3. (Joey swims) – F 4. (Joey is black and white) – F 5. (Joey lives in Antarctica) · Rules about animals in general – R 1. If (animal X has feathers) THEN (animal X is a bird) – R 2. If (animal X is a bird) and (animal X swims) and (animal X does not fly) and (animal X is black and white) THEN (animal is a penguin) – R 3. If (animal X’s mother Z) THEN (animal X Z) Example: if (animal X’s mother has feathers) then (animal X has feathers) – R 4. If (animal X Z) THEN (animal’s mother Z) · Notes – By combining the facts and rules, we can deduce that Joey is a penguin, and that the Joey’s mother is a penguin. CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 48

Smart Animal Guessing · Facts about an animal named “Joey” – F 1. (Joey’s mother has feathers) – F 2. (Joey does not fly) – F 3. (Joey swims) – F 4. (Joey is black and white) – F 5. (Joey lives in Antarctica) · Rules about animals in general – R 1. If (animal X has feathers) THEN (animal X is a bird) – R 2. If (animal X is a bird) and (animal X swims) and (animal X does not fly) and (animal X is black and white) THEN (animal is a penguin) – R 3. If (animal X’s mother Z) THEN (animal X Z) Example: if (animal X’s mother has feathers) then (animal X has feathers) – R 4. If (animal X Z) THEN (animal’s mother Z) · Notes – By combining the facts and rules, we can deduce that Joey is a penguin, and that the Joey’s mother is a penguin. CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 48

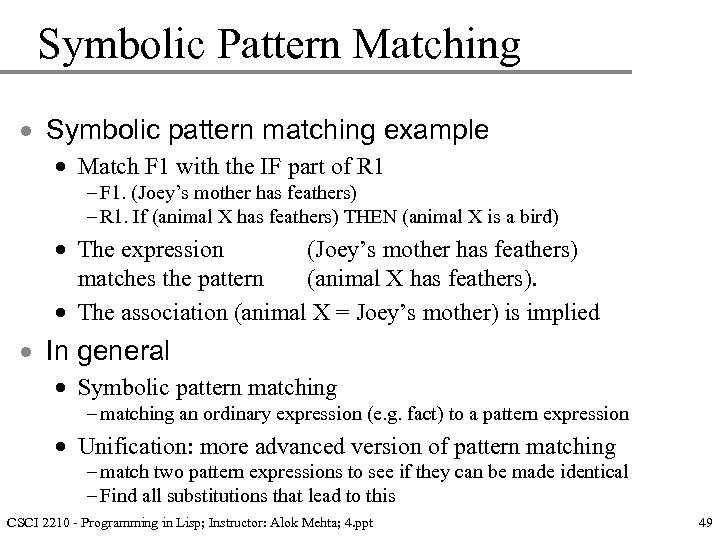

Symbolic Pattern Matching · Symbolic pattern matching example · Match F 1 with the IF part of R 1 – F 1. (Joey’s mother has feathers) – R 1. If (animal X has feathers) THEN (animal X is a bird) · The expression (Joey’s mother has feathers) matches the pattern (animal X has feathers). · The association (animal X = Joey’s mother) is implied · In general · Symbolic pattern matching – matching an ordinary expression (e. g. fact) to a pattern expression · Unification: more advanced version of pattern matching – match two pattern expressions to see if they can be made identical – Find all substitutions that lead to this CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 49

Symbolic Pattern Matching · Symbolic pattern matching example · Match F 1 with the IF part of R 1 – F 1. (Joey’s mother has feathers) – R 1. If (animal X has feathers) THEN (animal X is a bird) · The expression (Joey’s mother has feathers) matches the pattern (animal X has feathers). · The association (animal X = Joey’s mother) is implied · In general · Symbolic pattern matching – matching an ordinary expression (e. g. fact) to a pattern expression · Unification: more advanced version of pattern matching – match two pattern expressions to see if they can be made identical – Find all substitutions that lead to this CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 49

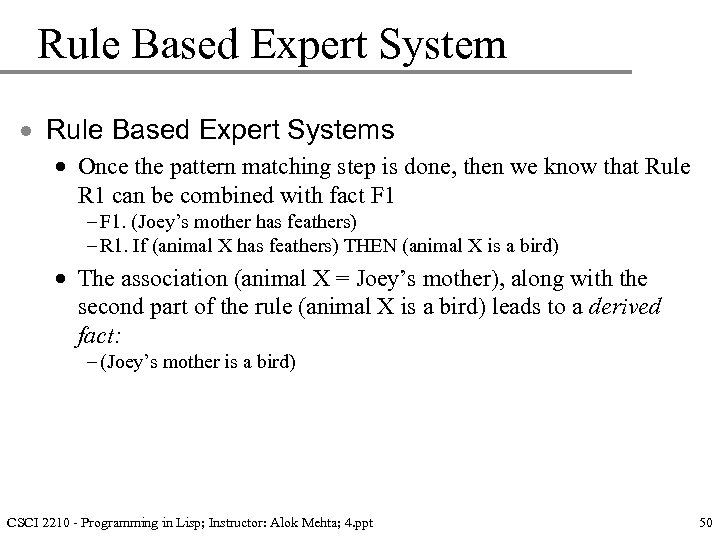

Rule Based Expert System · Rule Based Expert Systems · Once the pattern matching step is done, then we know that Rule R 1 can be combined with fact F 1 – F 1. (Joey’s mother has feathers) – R 1. If (animal X has feathers) THEN (animal X is a bird) · The association (animal X = Joey’s mother), along with the second part of the rule (animal X is a bird) leads to a derived fact: – (Joey’s mother is a bird) CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 50

Rule Based Expert System · Rule Based Expert Systems · Once the pattern matching step is done, then we know that Rule R 1 can be combined with fact F 1 – F 1. (Joey’s mother has feathers) – R 1. If (animal X has feathers) THEN (animal X is a bird) · The association (animal X = Joey’s mother), along with the second part of the rule (animal X is a bird) leads to a derived fact: – (Joey’s mother is a bird) CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 50

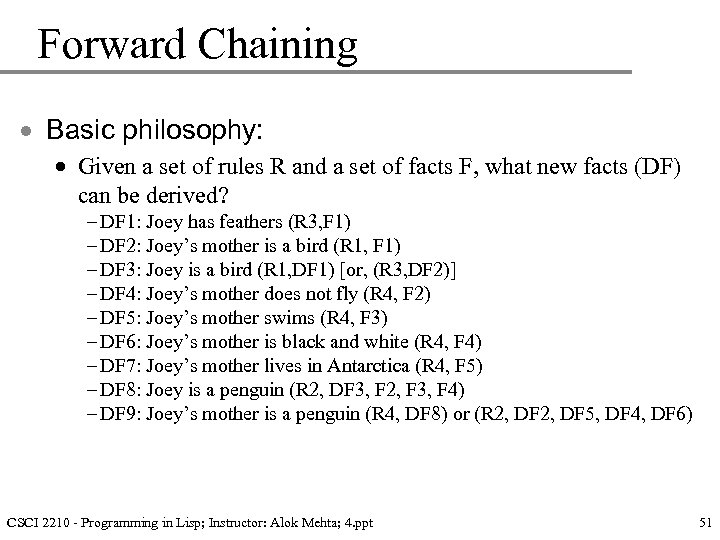

Forward Chaining · Basic philosophy: · Given a set of rules R and a set of facts F, what new facts (DF) can be derived? – DF 1: Joey has feathers (R 3, F 1) – DF 2: Joey’s mother is a bird (R 1, F 1) – DF 3: Joey is a bird (R 1, DF 1) [or, (R 3, DF 2)] – DF 4: Joey’s mother does not fly (R 4, F 2) – DF 5: Joey’s mother swims (R 4, F 3) – DF 6: Joey’s mother is black and white (R 4, F 4) – DF 7: Joey’s mother lives in Antarctica (R 4, F 5) – DF 8: Joey is a penguin (R 2, DF 3, F 2, F 3, F 4) – DF 9: Joey’s mother is a penguin (R 4, DF 8) or (R 2, DF 5, DF 4, DF 6) CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 51

Forward Chaining · Basic philosophy: · Given a set of rules R and a set of facts F, what new facts (DF) can be derived? – DF 1: Joey has feathers (R 3, F 1) – DF 2: Joey’s mother is a bird (R 1, F 1) – DF 3: Joey is a bird (R 1, DF 1) [or, (R 3, DF 2)] – DF 4: Joey’s mother does not fly (R 4, F 2) – DF 5: Joey’s mother swims (R 4, F 3) – DF 6: Joey’s mother is black and white (R 4, F 4) – DF 7: Joey’s mother lives in Antarctica (R 4, F 5) – DF 8: Joey is a penguin (R 2, DF 3, F 2, F 3, F 4) – DF 9: Joey’s mother is a penguin (R 4, DF 8) or (R 2, DF 5, DF 4, DF 6) CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 51

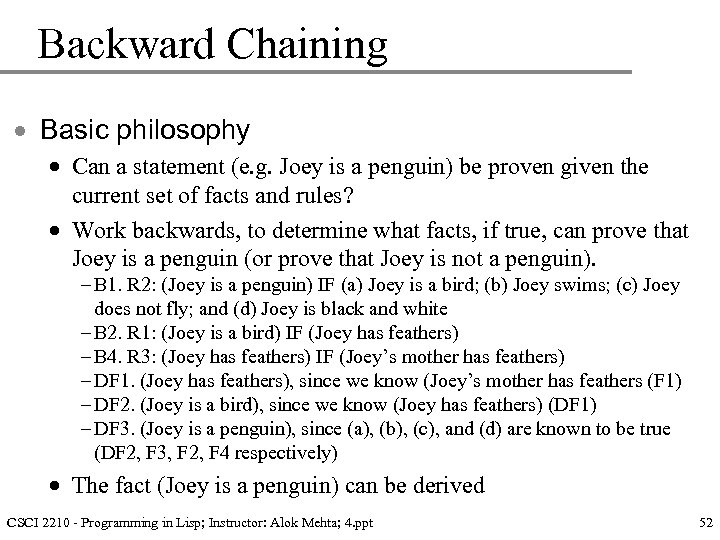

Backward Chaining · Basic philosophy · Can a statement (e. g. Joey is a penguin) be proven given the current set of facts and rules? · Work backwards, to determine what facts, if true, can prove that Joey is a penguin (or prove that Joey is not a penguin). – B 1. R 2: (Joey is a penguin) IF (a) Joey is a bird; (b) Joey swims; (c) Joey does not fly; and (d) Joey is black and white – B 2. R 1: (Joey is a bird) IF (Joey has feathers) – B 4. R 3: (Joey has feathers) IF (Joey’s mother has feathers) – DF 1. (Joey has feathers), since we know (Joey’s mother has feathers (F 1) – DF 2. (Joey is a bird), since we know (Joey has feathers) (DF 1) – DF 3. (Joey is a penguin), since (a), (b), (c), and (d) are known to be true (DF 2, F 3, F 2, F 4 respectively) · The fact (Joey is a penguin) can be derived CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 52

Backward Chaining · Basic philosophy · Can a statement (e. g. Joey is a penguin) be proven given the current set of facts and rules? · Work backwards, to determine what facts, if true, can prove that Joey is a penguin (or prove that Joey is not a penguin). – B 1. R 2: (Joey is a penguin) IF (a) Joey is a bird; (b) Joey swims; (c) Joey does not fly; and (d) Joey is black and white – B 2. R 1: (Joey is a bird) IF (Joey has feathers) – B 4. R 3: (Joey has feathers) IF (Joey’s mother has feathers) – DF 1. (Joey has feathers), since we know (Joey’s mother has feathers (F 1) – DF 2. (Joey is a bird), since we know (Joey has feathers) (DF 1) – DF 3. (Joey is a penguin), since (a), (b), (c), and (d) are known to be true (DF 2, F 3, F 2, F 4 respectively) · The fact (Joey is a penguin) can be derived CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 52

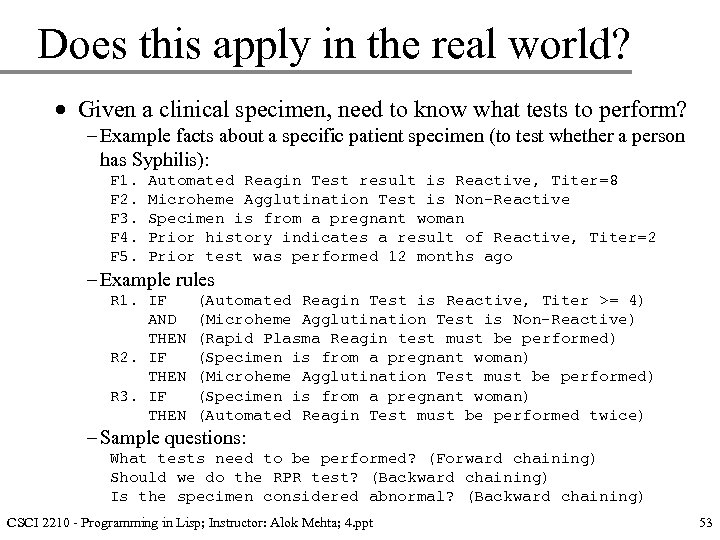

Does this apply in the real world? · Given a clinical specimen, need to know what tests to perform? – Example facts about a specific patient specimen (to test whether a person has Syphilis): F 1. F 2. F 3. F 4. F 5. Automated Reagin Test result is Reactive, Titer=8 Microheme Agglutination Test is Non-Reactive Specimen is from a pregnant woman Prior history indicates a result of Reactive, Titer=2 Prior test was performed 12 months ago – Example rules R 1. IF AND THEN R 2. IF THEN R 3. IF THEN (Automated Reagin Test is Reactive, Titer >= 4) (Microheme Agglutination Test is Non-Reactive) (Rapid Plasma Reagin test must be performed) (Specimen is from a pregnant woman) (Microheme Agglutination Test must be performed) (Specimen is from a pregnant woman) (Automated Reagin Test must be performed twice) – Sample questions: What tests need to be performed? (Forward chaining) Should we do the RPR test? (Backward chaining) Is the specimen considered abnormal? (Backward chaining) CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 53

Does this apply in the real world? · Given a clinical specimen, need to know what tests to perform? – Example facts about a specific patient specimen (to test whether a person has Syphilis): F 1. F 2. F 3. F 4. F 5. Automated Reagin Test result is Reactive, Titer=8 Microheme Agglutination Test is Non-Reactive Specimen is from a pregnant woman Prior history indicates a result of Reactive, Titer=2 Prior test was performed 12 months ago – Example rules R 1. IF AND THEN R 2. IF THEN R 3. IF THEN (Automated Reagin Test is Reactive, Titer >= 4) (Microheme Agglutination Test is Non-Reactive) (Rapid Plasma Reagin test must be performed) (Specimen is from a pregnant woman) (Microheme Agglutination Test must be performed) (Specimen is from a pregnant woman) (Automated Reagin Test must be performed twice) – Sample questions: What tests need to be performed? (Forward chaining) Should we do the RPR test? (Backward chaining) Is the specimen considered abnormal? (Backward chaining) CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 53

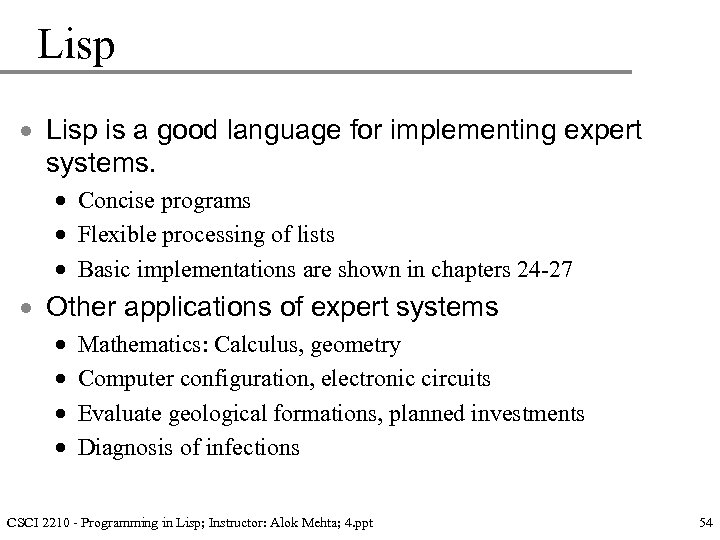

Lisp · Lisp is a good language for implementing expert systems. · Concise programs · Flexible processing of lists · Basic implementations are shown in chapters 24 -27 · Other applications of expert systems · · Mathematics: Calculus, geometry Computer configuration, electronic circuits Evaluate geological formations, planned investments Diagnosis of infections CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 54

Lisp · Lisp is a good language for implementing expert systems. · Concise programs · Flexible processing of lists · Basic implementations are shown in chapters 24 -27 · Other applications of expert systems · · Mathematics: Calculus, geometry Computer configuration, electronic circuits Evaluate geological formations, planned investments Diagnosis of infections CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 54

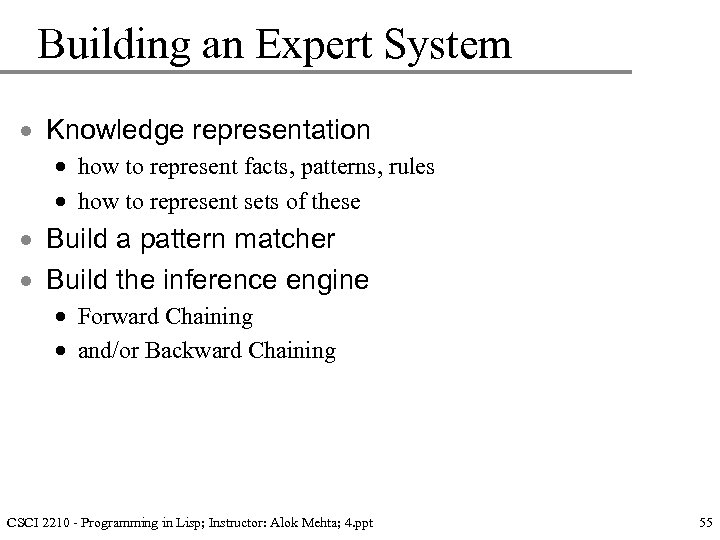

Building an Expert System · Knowledge representation · how to represent facts, patterns, rules · how to represent sets of these · Build a pattern matcher · Build the inference engine · Forward Chaining · and/or Backward Chaining CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 55

Building an Expert System · Knowledge representation · how to represent facts, patterns, rules · how to represent sets of these · Build a pattern matcher · Build the inference engine · Forward Chaining · and/or Backward Chaining CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 55

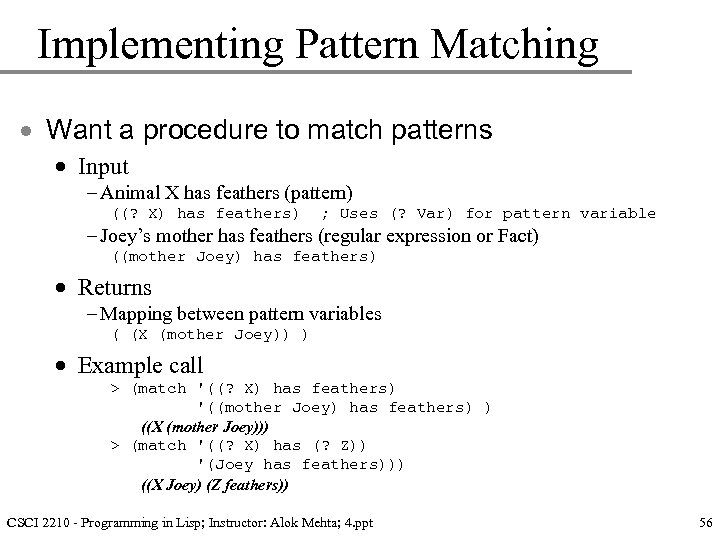

Implementing Pattern Matching · Want a procedure to match patterns · Input – Animal X has feathers (pattern) ((? X) has feathers) ; Uses (? Var) for pattern variable – Joey’s mother has feathers (regular expression or Fact) ((mother Joey) has feathers) · Returns – Mapping between pattern variables ( (X (mother Joey)) ) · Example call > (match '((? X) has feathers) '((mother Joey) has feathers) ) ((X (mother Joey))) > (match '((? X) has (? Z)) '(Joey has feathers))) ((X Joey) (Z feathers)) CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 56

Implementing Pattern Matching · Want a procedure to match patterns · Input – Animal X has feathers (pattern) ((? X) has feathers) ; Uses (? Var) for pattern variable – Joey’s mother has feathers (regular expression or Fact) ((mother Joey) has feathers) · Returns – Mapping between pattern variables ( (X (mother Joey)) ) · Example call > (match '((? X) has feathers) '((mother Joey) has feathers) ) ((X (mother Joey))) > (match '((? X) has (? Z)) '(Joey has feathers))) ((X Joey) (Z feathers)) CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 56

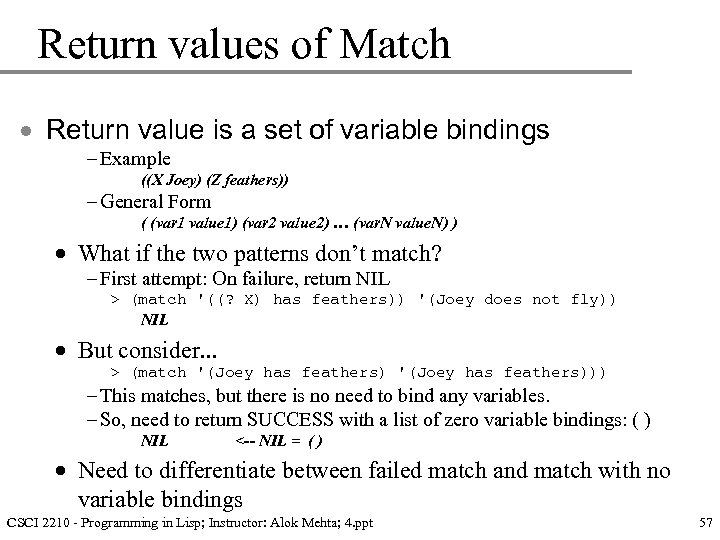

Return values of Match · Return value is a set of variable bindings – Example ((X Joey) (Z feathers)) – General Form ( (var 1 value 1) (var 2 value 2) … (var. N value. N) ) · What if the two patterns don’t match? – First attempt: On failure, return NIL > (match '((? X) has feathers)) '(Joey does not fly)) NIL · But consider. . . > (match '(Joey has feathers))) – This matches, but there is no need to bind any variables. – So, need to return SUCCESS with a list of zero variable bindings: ( ) NIL <-- NIL = ( ) · Need to differentiate between failed match and match with no variable bindings CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 57

Return values of Match · Return value is a set of variable bindings – Example ((X Joey) (Z feathers)) – General Form ( (var 1 value 1) (var 2 value 2) … (var. N value. N) ) · What if the two patterns don’t match? – First attempt: On failure, return NIL > (match '((? X) has feathers)) '(Joey does not fly)) NIL · But consider. . . > (match '(Joey has feathers))) – This matches, but there is no need to bind any variables. – So, need to return SUCCESS with a list of zero variable bindings: ( ) NIL <-- NIL = ( ) · Need to differentiate between failed match and match with no variable bindings CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 57

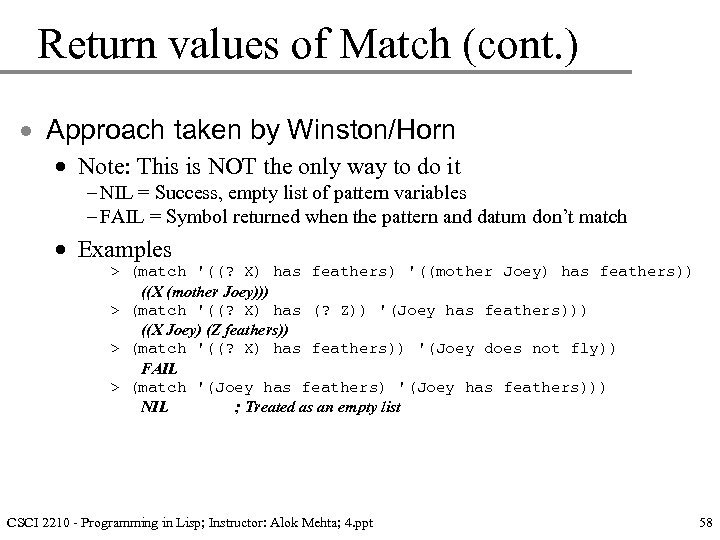

Return values of Match (cont. ) · Approach taken by Winston/Horn · Note: This is NOT the only way to do it – NIL = Success, empty list of pattern variables – FAIL = Symbol returned when the pattern and datum don’t match · Examples > (match '((? X) has feathers) '((mother Joey) has feathers)) ((X (mother Joey))) > (match '((? X) has (? Z)) '(Joey has feathers))) ((X Joey) (Z feathers)) > (match '((? X) has feathers)) '(Joey does not fly)) FAIL > (match '(Joey has feathers))) NIL ; Treated as an empty list CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 58

Return values of Match (cont. ) · Approach taken by Winston/Horn · Note: This is NOT the only way to do it – NIL = Success, empty list of pattern variables – FAIL = Symbol returned when the pattern and datum don’t match · Examples > (match '((? X) has feathers) '((mother Joey) has feathers)) ((X (mother Joey))) > (match '((? X) has (? Z)) '(Joey has feathers))) ((X Joey) (Z feathers)) > (match '((? X) has feathers)) '(Joey does not fly)) FAIL > (match '(Joey has feathers))) NIL ; Treated as an empty list CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 58

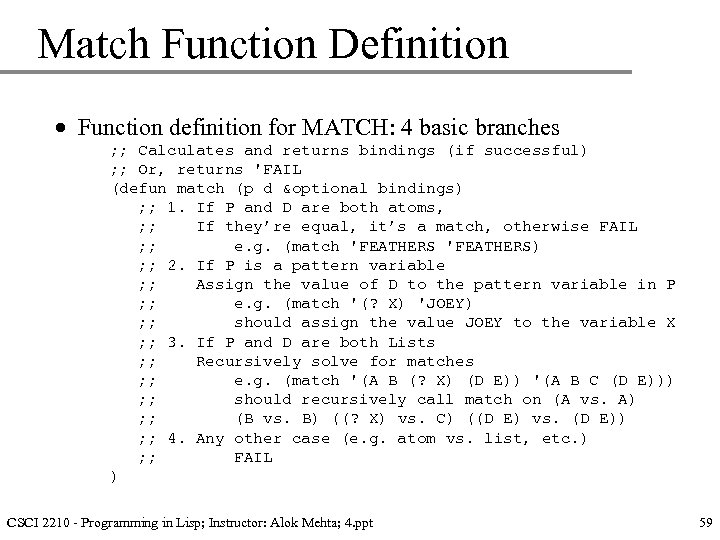

Match Function Definition · Function definition for MATCH: 4 basic branches ; ; Calculates and returns bindings (if successful) ; ; Or, returns 'FAIL (defun match (p d &optional bindings) ; ; 1. If P and D are both atoms, ; ; If they’re equal, it’s a match, otherwise FAIL ; ; e. g. (match 'FEATHERS) ; ; 2. If P is a pattern variable ; ; Assign the value of D to the pattern variable in P ; ; e. g. (match '(? X) 'JOEY) ; ; should assign the value JOEY to the variable X ; ; 3. If P and D are both Lists ; ; Recursively solve for matches ; ; e. g. (match '(A B (? X) (D E)) '(A B C (D E))) ; ; should recursively call match on (A vs. A) ; ; (B vs. B) ((? X) vs. C) ((D E) vs. (D E)) ; ; 4. Any other case (e. g. atom vs. list, etc. ) ; ; FAIL ) CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 59

Match Function Definition · Function definition for MATCH: 4 basic branches ; ; Calculates and returns bindings (if successful) ; ; Or, returns 'FAIL (defun match (p d &optional bindings) ; ; 1. If P and D are both atoms, ; ; If they’re equal, it’s a match, otherwise FAIL ; ; e. g. (match 'FEATHERS) ; ; 2. If P is a pattern variable ; ; Assign the value of D to the pattern variable in P ; ; e. g. (match '(? X) 'JOEY) ; ; should assign the value JOEY to the variable X ; ; 3. If P and D are both Lists ; ; Recursively solve for matches ; ; e. g. (match '(A B (? X) (D E)) '(A B C (D E))) ; ; should recursively call match on (A vs. A) ; ; (B vs. B) ((? X) vs. C) ((D E) vs. (D E)) ; ; 4. Any other case (e. g. atom vs. list, etc. ) ; ; FAIL ) CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 59

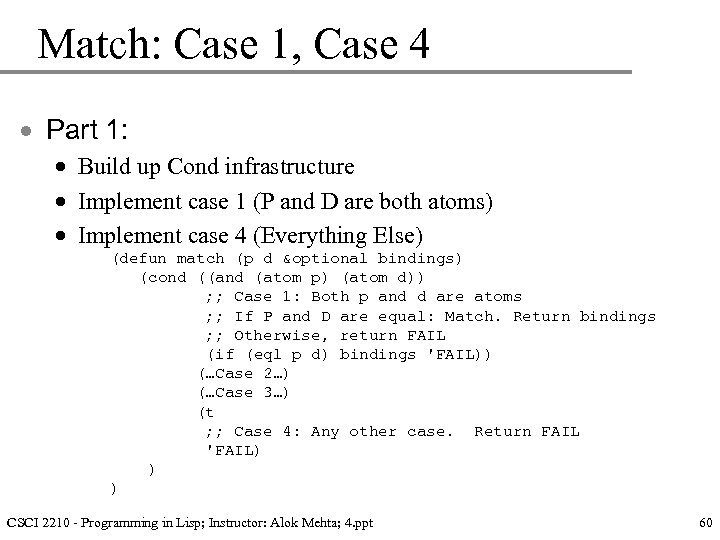

Match: Case 1, Case 4 · Part 1: · Build up Cond infrastructure · Implement case 1 (P and D are both atoms) · Implement case 4 (Everything Else) (defun match (p d &optional bindings) (cond ((and (atom p) (atom d)) ; ; Case 1: Both p and d are atoms ; ; If P and D are equal: Match. Return bindings ; ; Otherwise, return FAIL (if (eql p d) bindings 'FAIL)) (…Case 2…) (…Case 3…) (t ; ; Case 4: Any other case. Return FAIL 'FAIL) ) ) CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 60

Match: Case 1, Case 4 · Part 1: · Build up Cond infrastructure · Implement case 1 (P and D are both atoms) · Implement case 4 (Everything Else) (defun match (p d &optional bindings) (cond ((and (atom p) (atom d)) ; ; Case 1: Both p and d are atoms ; ; If P and D are equal: Match. Return bindings ; ; Otherwise, return FAIL (if (eql p d) bindings 'FAIL)) (…Case 2…) (…Case 3…) (t ; ; Case 4: Any other case. Return FAIL 'FAIL) ) ) CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 60

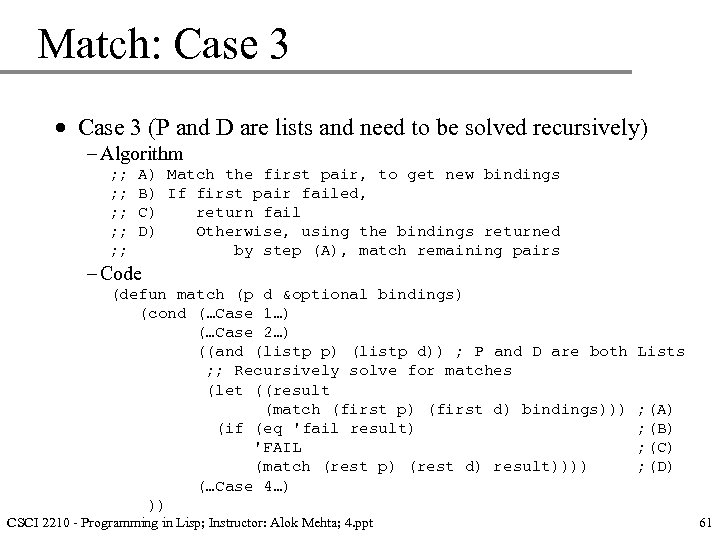

Match: Case 3 · Case 3 (P and D are lists and need to be solved recursively) – Algorithm ; ; ; ; ; A) Match the first pair, to get new bindings B) If first pair failed, C) return fail D) Otherwise, using the bindings returned by step (A), match remaining pairs – Code (defun match (p d &optional bindings) (cond (…Case 1…) (…Case 2…) ((and (listp p) (listp d)) ; P and D are both ; ; Recursively solve for matches (let ((result (match (first p) (first d) bindings))) (if (eq 'fail result) 'FAIL (match (rest p) (rest d) result)))) (…Case 4…) )) CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt Lists ; (A) ; (B) ; (C) ; (D) 61

Match: Case 3 · Case 3 (P and D are lists and need to be solved recursively) – Algorithm ; ; ; ; ; A) Match the first pair, to get new bindings B) If first pair failed, C) return fail D) Otherwise, using the bindings returned by step (A), match remaining pairs – Code (defun match (p d &optional bindings) (cond (…Case 1…) (…Case 2…) ((and (listp p) (listp d)) ; P and D are both ; ; Recursively solve for matches (let ((result (match (first p) (first d) bindings))) (if (eq 'fail result) 'FAIL (match (rest p) (rest d) result)))) (…Case 4…) )) CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt Lists ; (A) ; (B) ; (C) ; (D) 61

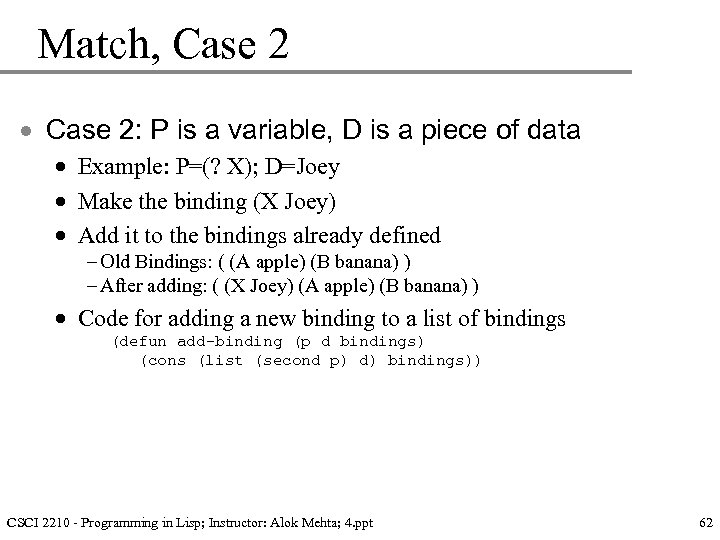

Match, Case 2 · Case 2: P is a variable, D is a piece of data · Example: P=(? X); D=Joey · Make the binding (X Joey) · Add it to the bindings already defined – Old Bindings: ( (A apple) (B banana) ) – After adding: ( (X Joey) (A apple) (B banana) ) · Code for adding a new binding to a list of bindings (defun add-binding (p d bindings) (cons (list (second p) d) bindings)) CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 62

Match, Case 2 · Case 2: P is a variable, D is a piece of data · Example: P=(? X); D=Joey · Make the binding (X Joey) · Add it to the bindings already defined – Old Bindings: ( (A apple) (B banana) ) – After adding: ( (X Joey) (A apple) (B banana) ) · Code for adding a new binding to a list of bindings (defun add-binding (p d bindings) (cons (list (second p) d) bindings)) CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 62

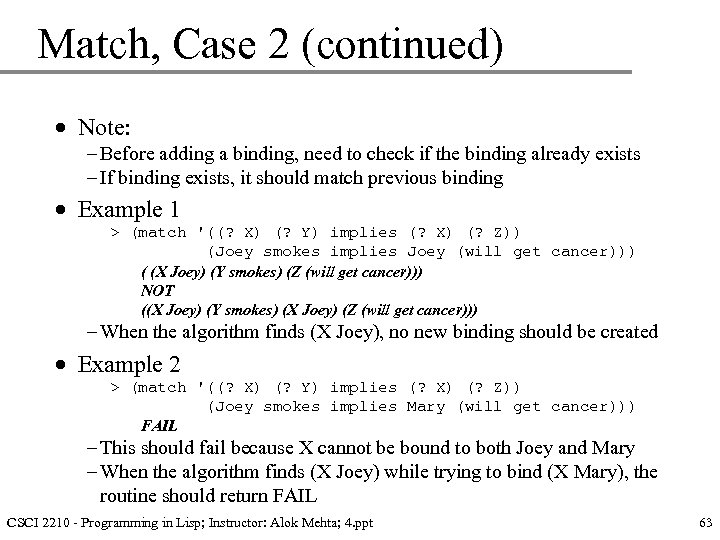

Match, Case 2 (continued) · Note: – Before adding a binding, need to check if the binding already exists – If binding exists, it should match previous binding · Example 1 > (match '((? X) (? Y) implies (? X) (? Z)) (Joey smokes implies Joey (will get cancer))) ( (X Joey) (Y smokes) (Z (will get cancer))) NOT ((X Joey) (Y smokes) (X Joey) (Z (will get cancer))) – When the algorithm finds (X Joey), no new binding should be created · Example 2 > (match '((? X) (? Y) implies (? X) (? Z)) (Joey smokes implies Mary (will get cancer))) FAIL – This should fail because X cannot be bound to both Joey and Mary – When the algorithm finds (X Joey) while trying to bind (X Mary), the routine should return FAIL CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 63

Match, Case 2 (continued) · Note: – Before adding a binding, need to check if the binding already exists – If binding exists, it should match previous binding · Example 1 > (match '((? X) (? Y) implies (? X) (? Z)) (Joey smokes implies Joey (will get cancer))) ( (X Joey) (Y smokes) (Z (will get cancer))) NOT ((X Joey) (Y smokes) (X Joey) (Z (will get cancer))) – When the algorithm finds (X Joey), no new binding should be created · Example 2 > (match '((? X) (? Y) implies (? X) (? Z)) (Joey smokes implies Mary (will get cancer))) FAIL – This should fail because X cannot be bound to both Joey and Mary – When the algorithm finds (X Joey) while trying to bind (X Mary), the routine should return FAIL CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 63

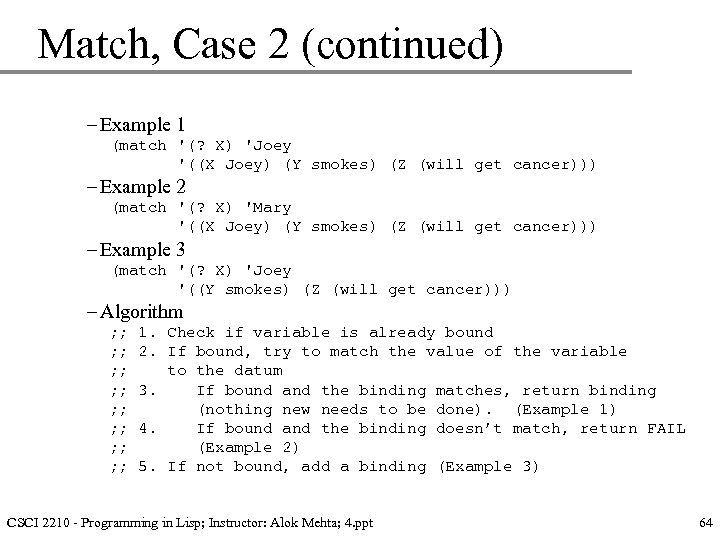

Match, Case 2 (continued) – Example 1 (match '(? X) 'Joey '((X Joey) (Y smokes) (Z (will get cancer))) – Example 2 (match '(? X) 'Mary '((X Joey) (Y smokes) (Z (will get cancer))) – Example 3 (match '(? X) 'Joey '((Y smokes) (Z (will get cancer))) – Algorithm ; ; ; ; 1. Check if variable is already bound 2. If bound, try to match the value of the variable to the datum 3. If bound and the binding matches, return binding (nothing new needs to be done). (Example 1) 4. If bound and the binding doesn’t match, return FAIL (Example 2) 5. If not bound, add a binding (Example 3) CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 64

Match, Case 2 (continued) – Example 1 (match '(? X) 'Joey '((X Joey) (Y smokes) (Z (will get cancer))) – Example 2 (match '(? X) 'Mary '((X Joey) (Y smokes) (Z (will get cancer))) – Example 3 (match '(? X) 'Joey '((Y smokes) (Z (will get cancer))) – Algorithm ; ; ; ; 1. Check if variable is already bound 2. If bound, try to match the value of the variable to the datum 3. If bound and the binding matches, return binding (nothing new needs to be done). (Example 1) 4. If bound and the binding doesn’t match, return FAIL (Example 2) 5. If not bound, add a binding (Example 3) CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 64

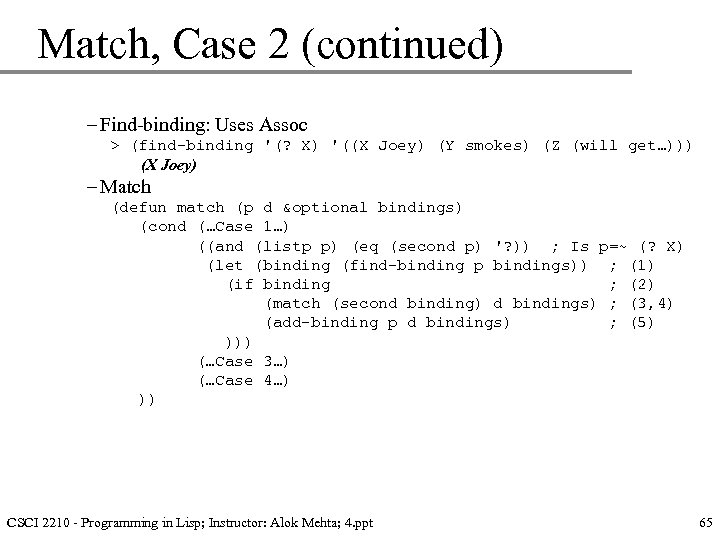

Match, Case 2 (continued) – Find-binding: Uses Assoc > (find-binding '(? X) '((X Joey) (Y smokes) (Z (will get…))) (X Joey) – Match (defun match (p d &optional bindings) (cond (…Case 1…) ((and (listp p) (eq (second p) '? )) ; Is p=~ (? X) (let (binding (find-binding p bindings)) ; (1) (if binding ; (2) (match (second binding) d bindings) ; (3, 4) (add-binding p d bindings) ; (5) ))) (…Case 3…) (…Case 4…) )) CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 65

Match, Case 2 (continued) – Find-binding: Uses Assoc > (find-binding '(? X) '((X Joey) (Y smokes) (Z (will get…))) (X Joey) – Match (defun match (p d &optional bindings) (cond (…Case 1…) ((and (listp p) (eq (second p) '? )) ; Is p=~ (? X) (let (binding (find-binding p bindings)) ; (1) (if binding ; (2) (match (second binding) d bindings) ; (3, 4) (add-binding p d bindings) ; (5) ))) (…Case 3…) (…Case 4…) )) CSCI 2210 - Programming in Lisp; Instructor: Alok Mehta; 4. ppt 65