d6aaa3f2e605dfb49b39bbb214ffdf9d.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 73

CS 432: Compiler Construction Lecture 5 Department of Computer Science Salisbury University Fall 2017 Instructor: Dr. Sophie Wang http: //faculty. salisbury. edu/~xswang 3/18/2018 1

CS 432: Compiler Construction Lecture 5 Department of Computer Science Salisbury University Fall 2017 Instructor: Dr. Sophie Wang http: //faculty. salisbury. edu/~xswang 3/18/2018 1

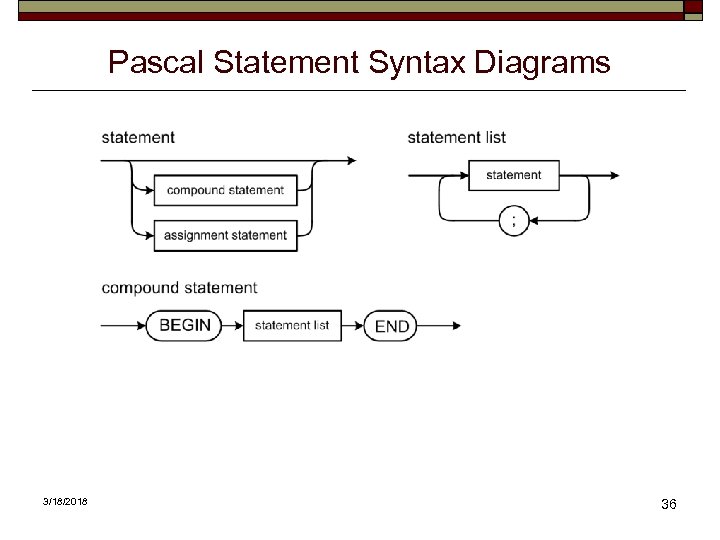

Goals and Approach The goals are ‒ Parsers in the front end for certain Pascal constructs: compound statements, assignment statements, and expressions. ‒ Flexible, language-independent intermediate code generated by the parsers to represent these constructs.

Goals and Approach The goals are ‒ Parsers in the front end for certain Pascal constructs: compound statements, assignment statements, and expressions. ‒ Flexible, language-independent intermediate code generated by the parsers to represent these constructs.

The approach is to: ‒ to begin with syntax diagrams for the Pascal constructs. ‒ you will create a conceptual design for the intermediate code structures, develop Java interfaces that represent the design, and write the Java classes that implement the interfaces. ‒ The syntax diagrams will guide the development of parsers that will generate the appropriate intermediate code. ‒ Finally, a syntax checker utility program will help verify the code you develop for this chapter.

The approach is to: ‒ to begin with syntax diagrams for the Pascal constructs. ‒ you will create a conceptual design for the intermediate code structures, develop Java interfaces that represent the design, and write the Java classes that implement the interfaces. ‒ The syntax diagrams will guide the development of parsers that will generate the appropriate intermediate code. ‒ Finally, a syntax checker utility program will help verify the code you develop for this chapter.

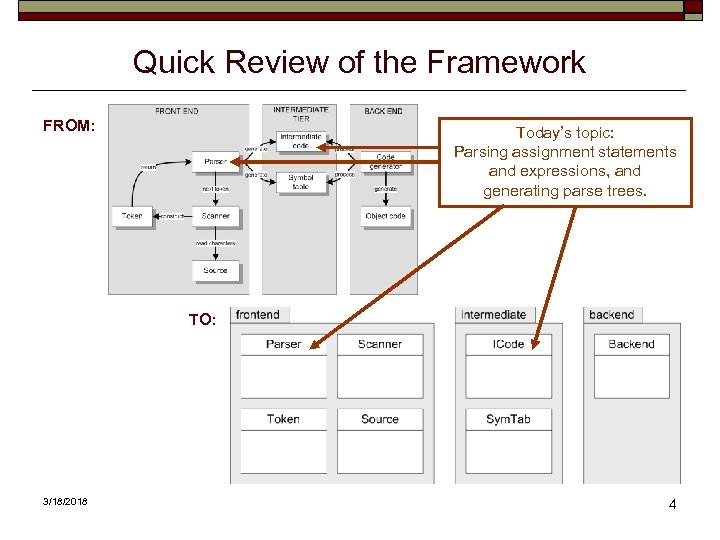

Quick Review of the Framework FROM: Today’s topic: Parsing assignment statements and expressions, and generating parse trees. TO: 3/18/2018 4

Quick Review of the Framework FROM: Today’s topic: Parsing assignment statements and expressions, and generating parse trees. TO: 3/18/2018 4

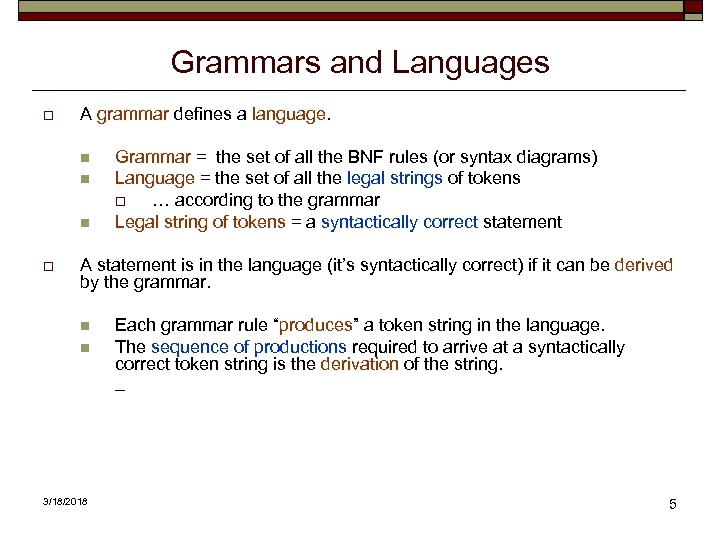

Grammars and Languages o A grammar defines a language. n n n o Grammar = the set of all the BNF rules (or syntax diagrams) Language = the set of all the legal strings of tokens o … according to the grammar Legal string of tokens = a syntactically correct statement A statement is in the language (it’s syntactically correct) if it can be derived by the grammar. n n 3/18/2018 Each grammar rule “produces” a token string in the language. The sequence of productions required to arrive at a syntactically correct token string is the derivation of the string. _ 5

Grammars and Languages o A grammar defines a language. n n n o Grammar = the set of all the BNF rules (or syntax diagrams) Language = the set of all the legal strings of tokens o … according to the grammar Legal string of tokens = a syntactically correct statement A statement is in the language (it’s syntactically correct) if it can be derived by the grammar. n n 3/18/2018 Each grammar rule “produces” a token string in the language. The sequence of productions required to arrive at a syntactically correct token string is the derivation of the string. _ 5

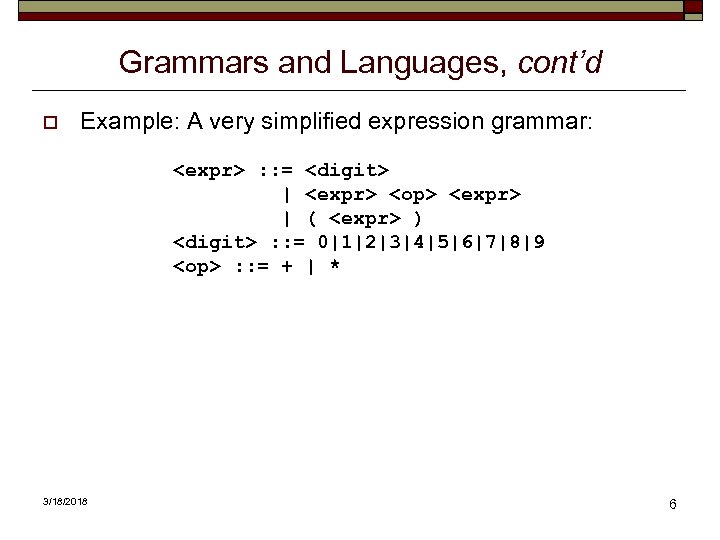

Grammars and Languages, cont’d o Example: A very simplified expression grammar:

Grammars and Languages, cont’d o Example: A very simplified expression grammar:

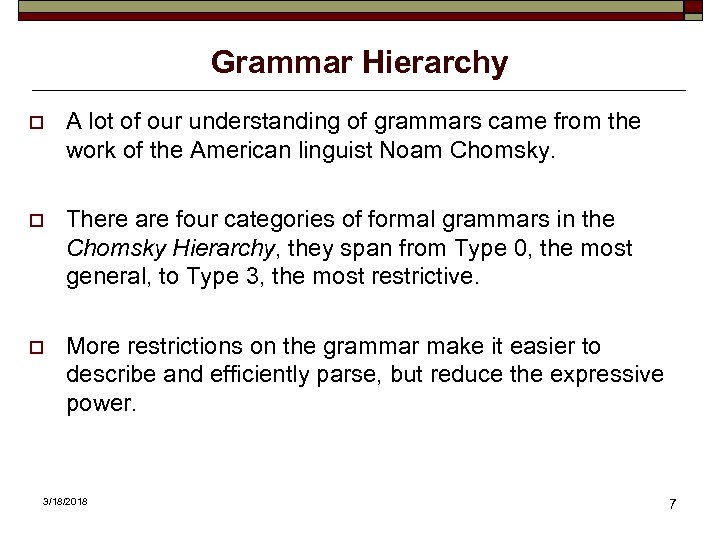

Grammar Hierarchy o A lot of our understanding of grammars came from the work of the American linguist Noam Chomsky. o There are four categories of formal grammars in the Chomsky Hierarchy, they span from Type 0, the most general, to Type 3, the most restrictive. o More restrictions on the grammar make it easier to describe and efficiently parse, but reduce the expressive power. 3/18/2018 7

Grammar Hierarchy o A lot of our understanding of grammars came from the work of the American linguist Noam Chomsky. o There are four categories of formal grammars in the Chomsky Hierarchy, they span from Type 0, the most general, to Type 3, the most restrictive. o More restrictions on the grammar make it easier to describe and efficiently parse, but reduce the expressive power. 3/18/2018 7

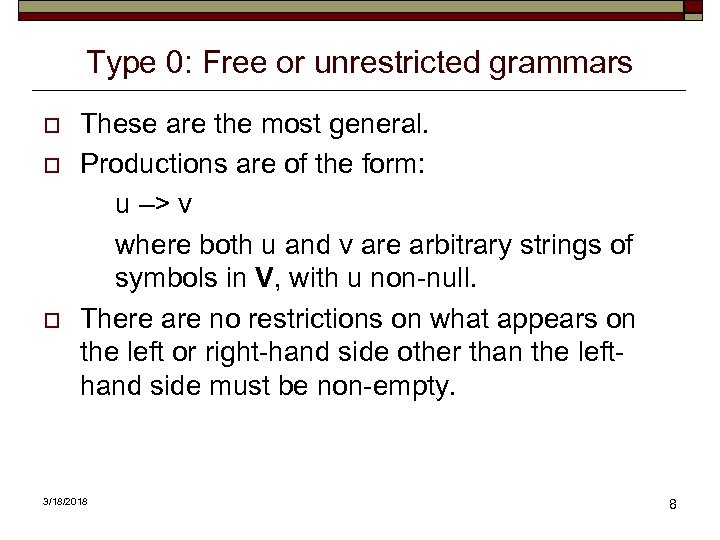

Type 0: Free or unrestricted grammars o o o These are the most general. Productions are of the form: u –> v where both u and v are arbitrary strings of symbols in V, with u non-null. There are no restrictions on what appears on the left or right-hand side other than the lefthand side must be non-empty. 3/18/2018 8

Type 0: Free or unrestricted grammars o o o These are the most general. Productions are of the form: u –> v where both u and v are arbitrary strings of symbols in V, with u non-null. There are no restrictions on what appears on the left or right-hand side other than the lefthand side must be non-empty. 3/18/2018 8

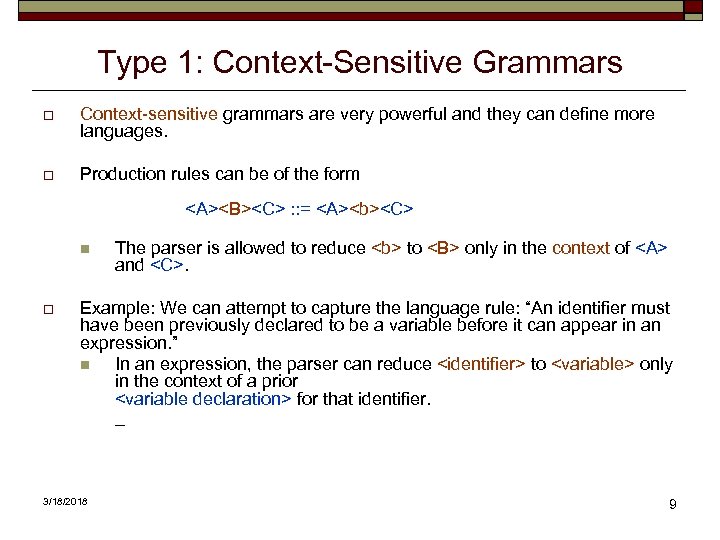

Type 1: Context-Sensitive Grammars o Context-sensitive grammars are very powerful and they can define more languages. o Production rules can be of the form

Type 1: Context-Sensitive Grammars o Context-sensitive grammars are very powerful and they can define more languages. o Production rules can be of the form

Context-Sensitive Grammars, cont’d o Context-sensitive grammars are extremely unwieldy for writing compilers. n Alternative: Use context-free grammars and rely on semantic actions such as building symbol tables to provide the context. _ 3/18/2018 10

Context-Sensitive Grammars, cont’d o Context-sensitive grammars are extremely unwieldy for writing compilers. n Alternative: Use context-free grammars and rely on semantic actions such as building symbol tables to provide the context. _ 3/18/2018 10

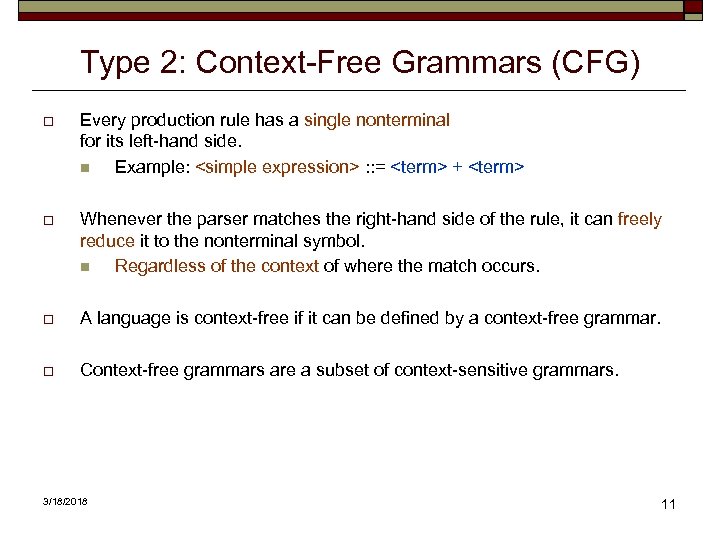

Type 2: Context-Free Grammars (CFG) o Every production rule has a single nonterminal for its left-hand side. n Example:

Type 2: Context-Free Grammars (CFG) o Every production rule has a single nonterminal for its left-hand side. n Example:

Type 3: Regular grammars o o o Productions are of the form X–> a. Y X–>ε where X and Y are nonterminals and a is a terminal. That is, the left-hand side must be a single nonterminal and the right-hand side can be either empty, a single terminal by itself or with a single nonterminal. These grammars are the most limited in terms of expressive power. 3/18/2018 12

Type 3: Regular grammars o o o Productions are of the form X–> a. Y X–>ε where X and Y are nonterminals and a is a terminal. That is, the left-hand side must be a single nonterminal and the right-hand side can be either empty, a single terminal by itself or with a single nonterminal. These grammars are the most limited in terms of expressive power. 3/18/2018 12

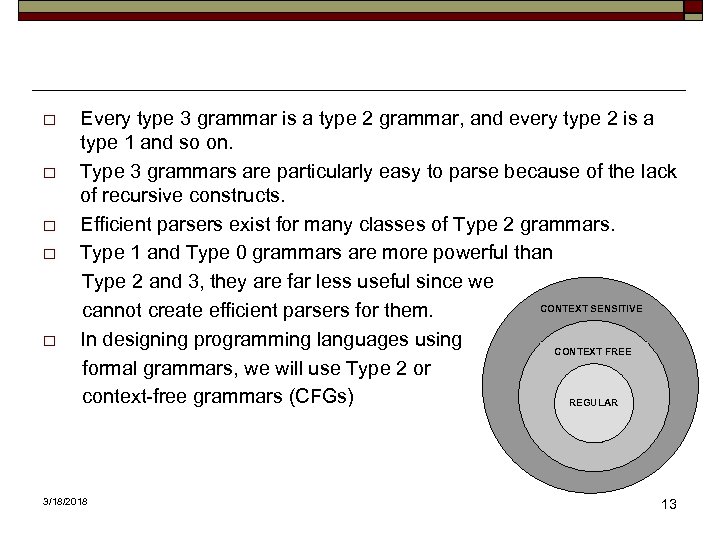

o o o Every type 3 grammar is a type 2 grammar, and every type 2 is a type 1 and so on. Type 3 grammars are particularly easy to parse because of the lack of recursive constructs. Efficient parsers exist for many classes of Type 2 grammars. Type 1 and Type 0 grammars are more powerful than Type 2 and 3, they are far less useful since we CONTEXT SENSITIVE cannot create efficient parsers for them. In designing programming languages using CONTEXT FREE formal grammars, we will use Type 2 or context-free grammars (CFGs) REGULAR 3/18/2018 13

o o o Every type 3 grammar is a type 2 grammar, and every type 2 is a type 1 and so on. Type 3 grammars are particularly easy to parse because of the lack of recursive constructs. Efficient parsers exist for many classes of Type 2 grammars. Type 1 and Type 0 grammars are more powerful than Type 2 and 3, they are far less useful since we CONTEXT SENSITIVE cannot create efficient parsers for them. In designing programming languages using CONTEXT FREE formal grammars, we will use Type 2 or context-free grammars (CFGs) REGULAR 3/18/2018 13

Issues in parsing context-free grammars o o o 3/18/2018 Ambiguity, Recursive rules, and Left-factoring. 14

Issues in parsing context-free grammars o o o 3/18/2018 Ambiguity, Recursive rules, and Left-factoring. 14

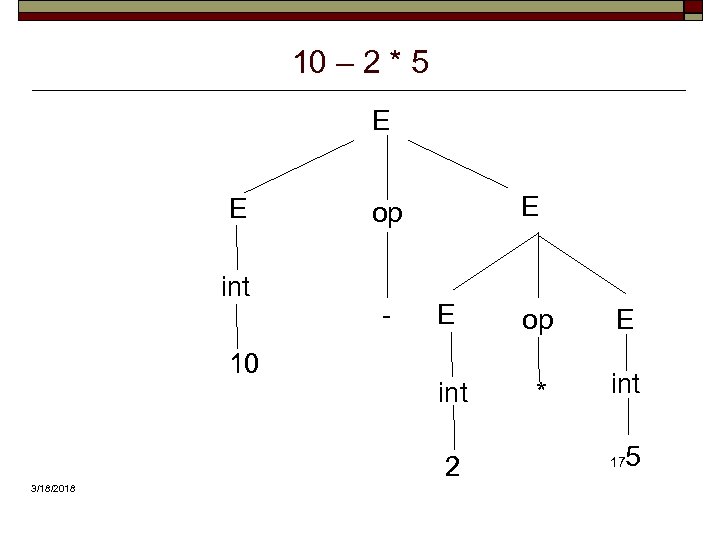

Ambiguity o o If a grammar permits more than one parse tree for some sentences, it is said to be ambiguous. For example, consider the following classic arithmetic expression grammar: E –> E op E | ( E ) | int op –> + | - | * | / int –> 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 3/18/2018 15

Ambiguity o o If a grammar permits more than one parse tree for some sentences, it is said to be ambiguous. For example, consider the following classic arithmetic expression grammar: E –> E op E | ( E ) | int op –> + | - | * | / int –> 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 3/18/2018 15

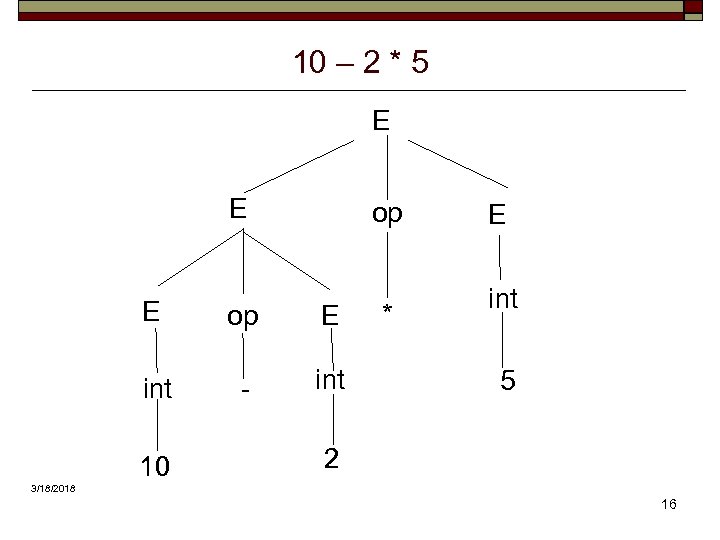

10 – 2 * 5 E E op E int - int 10 * E int 5 2 3/18/2018 16

10 – 2 * 5 E E op E int - int 10 * E int 5 2 3/18/2018 16

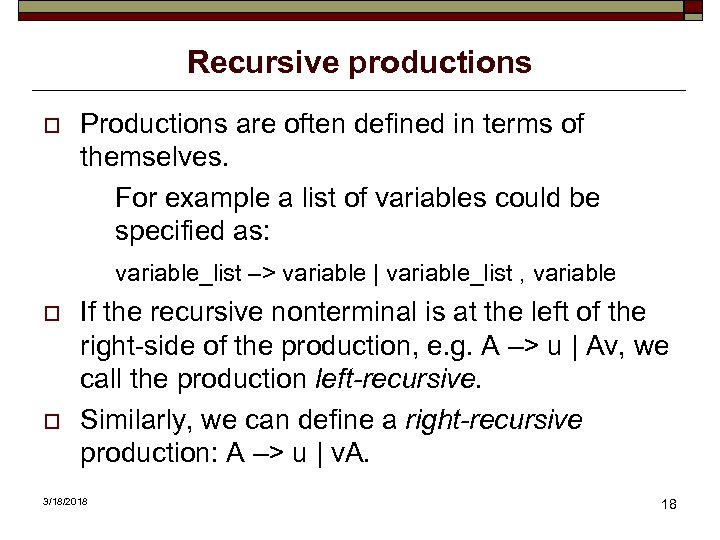

10 – 2 * 5 E E int 10 E op - E op E int * int 2 3/18/2018 5 17

10 – 2 * 5 E E int 10 E op - E op E int * int 2 3/18/2018 5 17

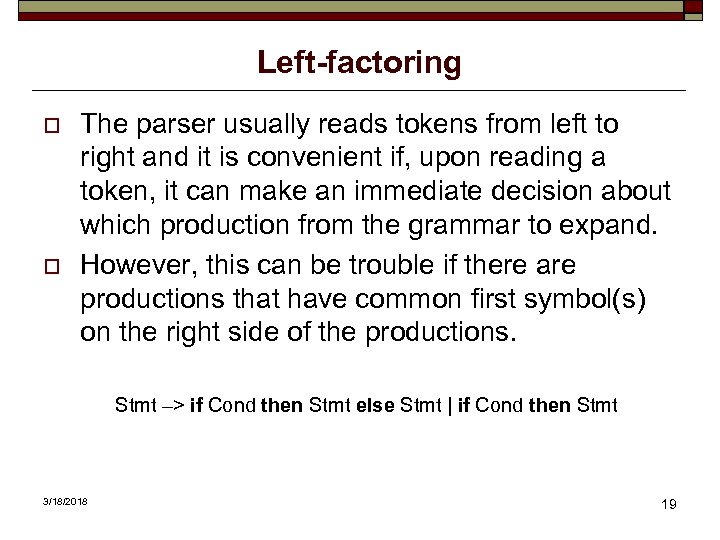

Recursive productions o Productions are often defined in terms of themselves. For example a list of variables could be specified as: variable_list –> variable | variable_list , variable o o If the recursive nonterminal is at the left of the right-side of the production, e. g. A –> u | Av, we call the production left-recursive. Similarly, we can define a right-recursive production: A –> u | v. A. 3/18/2018 18

Recursive productions o Productions are often defined in terms of themselves. For example a list of variables could be specified as: variable_list –> variable | variable_list , variable o o If the recursive nonterminal is at the left of the right-side of the production, e. g. A –> u | Av, we call the production left-recursive. Similarly, we can define a right-recursive production: A –> u | v. A. 3/18/2018 18

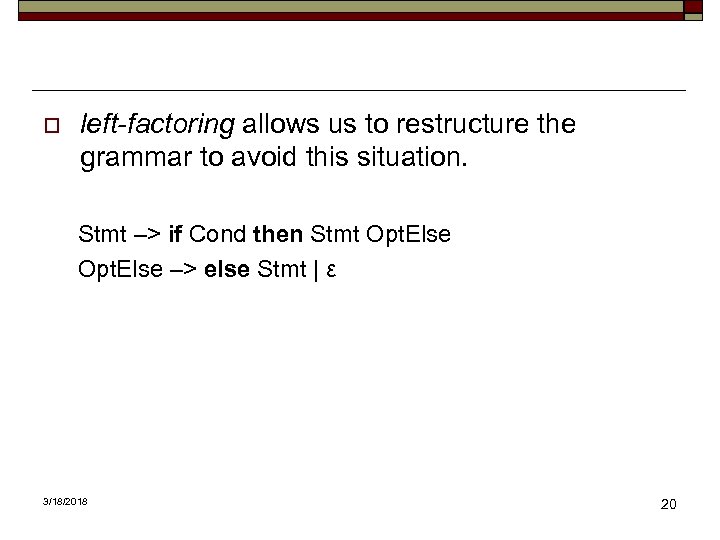

Left-factoring o o The parser usually reads tokens from left to right and it is convenient if, upon reading a token, it can make an immediate decision about which production from the grammar to expand. However, this can be trouble if there are productions that have common first symbol(s) on the right side of the productions. Stmt –> if Cond then Stmt else Stmt | if Cond then Stmt 3/18/2018 19

Left-factoring o o The parser usually reads tokens from left to right and it is convenient if, upon reading a token, it can make an immediate decision about which production from the grammar to expand. However, this can be trouble if there are productions that have common first symbol(s) on the right side of the productions. Stmt –> if Cond then Stmt else Stmt | if Cond then Stmt 3/18/2018 19

o left-factoring allows us to restructure the grammar to avoid this situation. Stmt –> if Cond then Stmt Opt. Else –> else Stmt | ε 3/18/2018 20

o left-factoring allows us to restructure the grammar to avoid this situation. Stmt –> if Cond then Stmt Opt. Else –> else Stmt | ε 3/18/2018 20

Top-Down Parsers o Start with the topmost nonterminal grammar symbol such as

Top-Down Parsers o Start with the topmost nonterminal grammar symbol such as

Top-Down Parsers, cont’d o Write a parse method for a production (grammar) rule. n n n o Each parse method “expects” to see tokens from the source program that match its production rule. o Example: Stmt –> if Cond then Stmt Opt. Else A parse method calls other parse methods that implement lower production rules. Parse methods consume tokens that match the production rules. A parse is successful if it’s able to derive the input string (i. e. , the source program) from the production rules. n All the tokens match the production rules and are consumed. _ 3/18/2018 22

Top-Down Parsers, cont’d o Write a parse method for a production (grammar) rule. n n n o Each parse method “expects” to see tokens from the source program that match its production rule. o Example: Stmt –> if Cond then Stmt Opt. Else A parse method calls other parse methods that implement lower production rules. Parse methods consume tokens that match the production rules. A parse is successful if it’s able to derive the input string (i. e. , the source program) from the production rules. n All the tokens match the production rules and are consumed. _ 3/18/2018 22

Top-down parsing o A top-down parsing program consists of a set of procedures, one for each non-terminal. o Execution begins with the procedure for the start symbol, which halts and announces success if its procedure body scans the entire input string. 23

Top-down parsing o A top-down parsing program consists of a set of procedures, one for each non-terminal. o Execution begins with the procedure for the start symbol, which halts and announces success if its procedure body scans the entire input string. 23

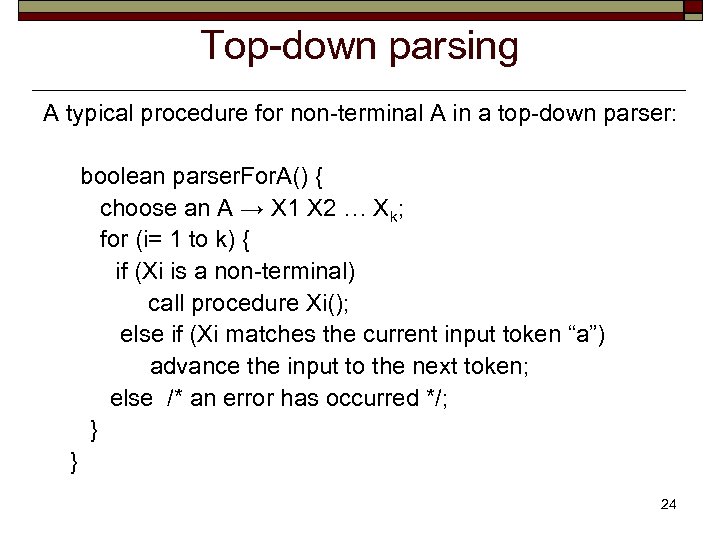

Top-down parsing A typical procedure for non-terminal A in a top-down parser: boolean parser. For. A() { choose an A → X 1 X 2 … Xk; for (i= 1 to k) { if (Xi is a non-terminal) call procedure Xi(); else if (Xi matches the current input token “a”) advance the input to the next token; else /* an error has occurred */; } } 24

Top-down parsing A typical procedure for non-terminal A in a top-down parser: boolean parser. For. A() { choose an A → X 1 X 2 … Xk; for (i= 1 to k) { if (Xi is a non-terminal) call procedure Xi(); else if (Xi matches the current input token “a”) advance the input to the next token; else /* an error has occurred */; } } 24

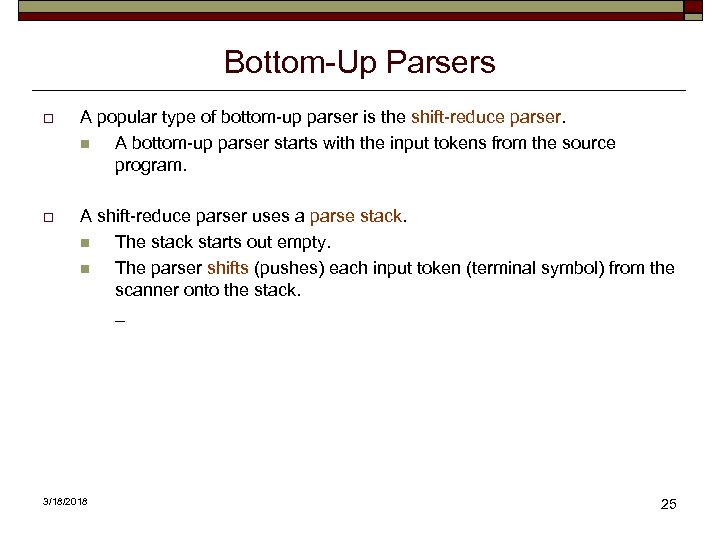

Bottom-Up Parsers o A popular type of bottom-up parser is the shift-reduce parser. n A bottom-up parser starts with the input tokens from the source program. o A shift-reduce parser uses a parse stack. n The stack starts out empty. n The parser shifts (pushes) each input token (terminal symbol) from the scanner onto the stack. _ 3/18/2018 25

Bottom-Up Parsers o A popular type of bottom-up parser is the shift-reduce parser. n A bottom-up parser starts with the input tokens from the source program. o A shift-reduce parser uses a parse stack. n The stack starts out empty. n The parser shifts (pushes) each input token (terminal symbol) from the scanner onto the stack. _ 3/18/2018 25

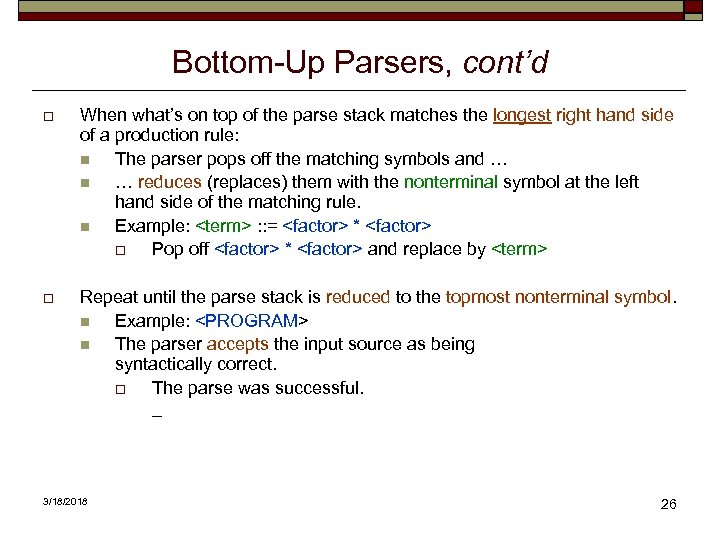

Bottom-Up Parsers, cont’d o When what’s on top of the parse stack matches the longest right hand side of a production rule: n The parser pops off the matching symbols and … n … reduces (replaces) them with the nonterminal symbol at the left hand side of the matching rule. n Example:

Bottom-Up Parsers, cont’d o When what’s on top of the parse stack matches the longest right hand side of a production rule: n The parser pops off the matching symbols and … n … reduces (replaces) them with the nonterminal symbol at the left hand side of the matching rule. n Example:

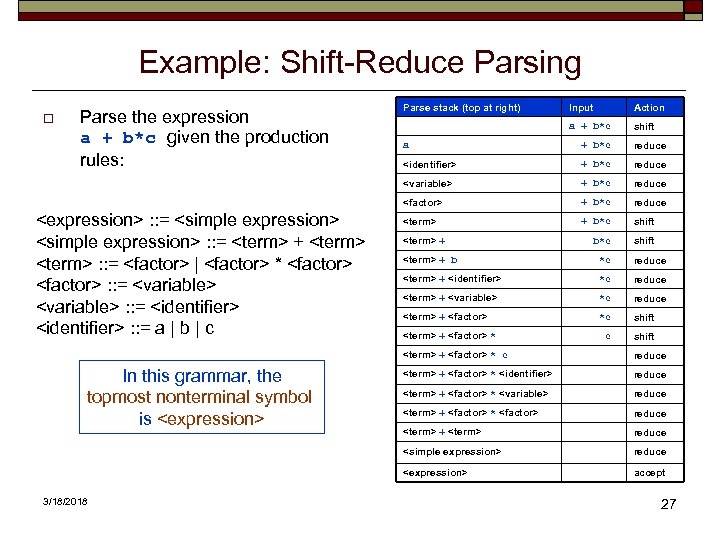

Example: Shift-Reduce Parsing o Parse the expression a + b*c given the production rules: Parse stack (top at right) Input Action a + b*c shift + b*c reduce

Example: Shift-Reduce Parsing o Parse the expression a + b*c given the production rules: Parse stack (top at right) Input Action a + b*c shift + b*c reduce

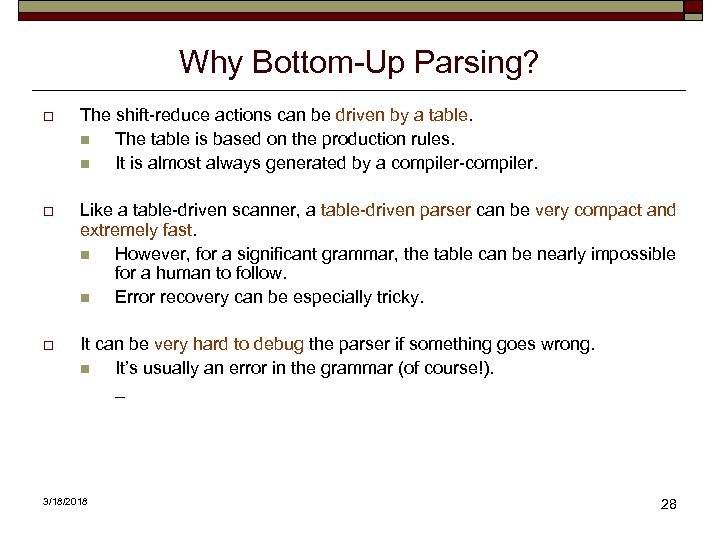

Why Bottom-Up Parsing? o The shift-reduce actions can be driven by a table. n The table is based on the production rules. n It is almost always generated by a compiler-compiler. o Like a table-driven scanner, a table-driven parser can be very compact and extremely fast. n However, for a significant grammar, the table can be nearly impossible for a human to follow. n Error recovery can be especially tricky. o It can be very hard to debug the parser if something goes wrong. n It’s usually an error in the grammar (of course!). _ 3/18/2018 28

Why Bottom-Up Parsing? o The shift-reduce actions can be driven by a table. n The table is based on the production rules. n It is almost always generated by a compiler-compiler. o Like a table-driven scanner, a table-driven parser can be very compact and extremely fast. n However, for a significant grammar, the table can be nearly impossible for a human to follow. n Error recovery can be especially tricky. o It can be very hard to debug the parser if something goes wrong. n It’s usually an error in the grammar (of course!). _ 3/18/2018 28

LL and LR Parsers o Parsers are classified LL or LR according to the way they operate while parsing. o The first L stands for left-to-right, the order a parser reads the source program. o If the second letter is also L, it means that whenever the parser is processing a production rule, it “expands” the leftmost nonterminal symbol first. _ 3/18/2018 29

LL and LR Parsers o Parsers are classified LL or LR according to the way they operate while parsing. o The first L stands for left-to-right, the order a parser reads the source program. o If the second letter is also L, it means that whenever the parser is processing a production rule, it “expands” the leftmost nonterminal symbol first. _ 3/18/2018 29

o o LL parsers begin at the start symbol and try to apply productions to arrive at the target string. An LL parser is a left-to-right, leftmost derivation. That is, we consider the input symbols from the left to the right and attempt to construct a leftmost derivation. This is done by beginning at the start symbol and repeatedly expanding out the leftmost nonterminal until we arrive at the target string. LR parsers begin at the target string and try to arrive back at the start symbol. An LR parse is a left-to-right, rightmost derivation, meaning that we scan from the left to right and attempt to construct a rightmost derivation. The parser continuously picks a substring of the input and attempts to reverse it back to a nonterminal. 3/18/2018 30

o o LL parsers begin at the start symbol and try to apply productions to arrive at the target string. An LL parser is a left-to-right, leftmost derivation. That is, we consider the input symbols from the left to the right and attempt to construct a leftmost derivation. This is done by beginning at the start symbol and repeatedly expanding out the leftmost nonterminal until we arrive at the target string. LR parsers begin at the target string and try to arrive back at the start symbol. An LR parse is a left-to-right, rightmost derivation, meaning that we scan from the left to right and attempt to construct a rightmost derivation. The parser continuously picks a substring of the input and attempts to reverse it back to a nonterminal. 3/18/2018 30

o o o During an LL parse, the parser continuously chooses between two actions: Predict: Based on the leftmost nonterminal and some number of lookahead tokens, choose which production ought to be applied to get closer to the input string. Match: Match the leftmost guessed terminal symbol with the leftmost unconsumed symbol of input. 3/18/2018 31

o o o During an LL parse, the parser continuously chooses between two actions: Predict: Based on the leftmost nonterminal and some number of lookahead tokens, choose which production ought to be applied to get closer to the input string. Match: Match the leftmost guessed terminal symbol with the leftmost unconsumed symbol of input. 3/18/2018 31

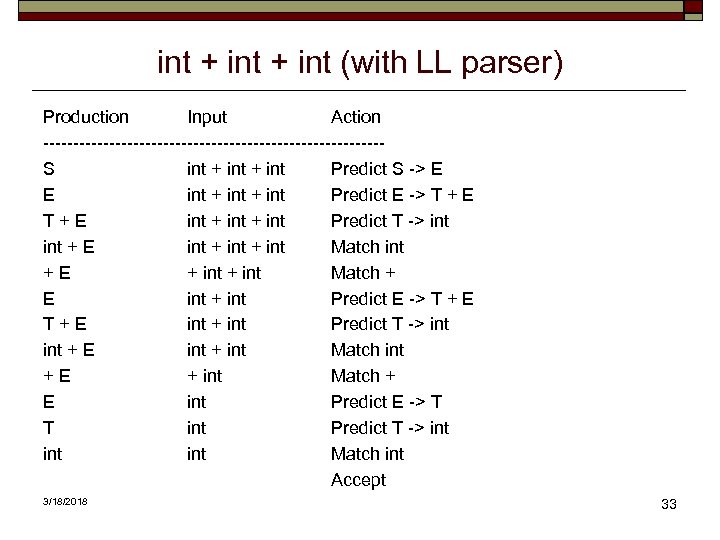

o As an example, given this grammar: n n o S→E E→T+E E→T T → int Notice that in each step LL parser look at the leftmost symbol in the production. If it's a terminal, we match it, and if it's a nonterminal, we predict what it's going to be by choosing one of the rules. 3/18/2018 32

o As an example, given this grammar: n n o S→E E→T+E E→T T → int Notice that in each step LL parser look at the leftmost symbol in the production. If it's a terminal, we match it, and if it's a nonterminal, we predict what it's going to be by choosing one of the rules. 3/18/2018 32

int + int (with LL parser) Production Input Action ----------------------------S int + int Predict S -> E E int + int Predict E -> T + E T+E int + int Predict T -> int + E int + int Match int +E + int Match + E int Predict E -> T T int Predict T -> int int Match int Accept 3/18/2018 33

int + int (with LL parser) Production Input Action ----------------------------S int + int Predict S -> E E int + int Predict E -> T + E T+E int + int Predict T -> int + E int + int Match int +E + int Match + E int Predict E -> T T int Predict T -> int int Match int Accept 3/18/2018 33

o o o In an LR parser, there are two actions: Shift: Add the next token of input to a buffer for consideration. Reduce: Reduce a collection of terminals and nonterminals in this buffer back to some nonterminal by reversing a production. 3/18/2018 34

o o o In an LR parser, there are two actions: Shift: Add the next token of input to a buffer for consideration. Reduce: Reduce a collection of terminals and nonterminals in this buffer back to some nonterminal by reversing a production. 3/18/2018 34

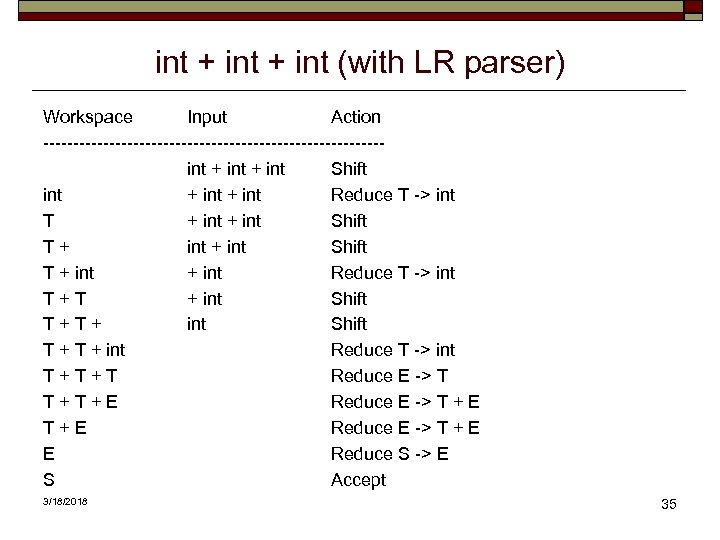

int + int (with LR parser) Workspace Input Action ----------------------------int + int Shift int + int Reduce T -> int T + int Shift T+ int Shift T + int Reduce T -> int T+T + int Shift T+T+ int Shift T + int Reduce T -> int T+T+T Reduce E -> T T+T+E Reduce E -> T + E E Reduce S -> E S Accept 3/18/2018 35

int + int (with LR parser) Workspace Input Action ----------------------------int + int Shift int + int Reduce T -> int T + int Shift T+ int Shift T + int Reduce T -> int T+T + int Shift T+T+ int Shift T + int Reduce T -> int T+T+T Reduce E -> T T+T+E Reduce E -> T + E E Reduce S -> E S Accept 3/18/2018 35

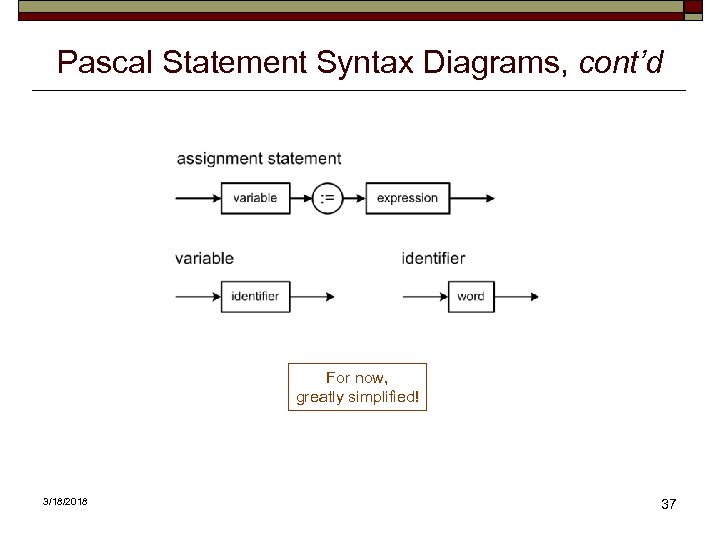

Pascal Statement Syntax Diagrams 3/18/2018 36

Pascal Statement Syntax Diagrams 3/18/2018 36

Pascal Statement Syntax Diagrams, cont’d For now, greatly simplified! 3/18/2018 37

Pascal Statement Syntax Diagrams, cont’d For now, greatly simplified! 3/18/2018 37

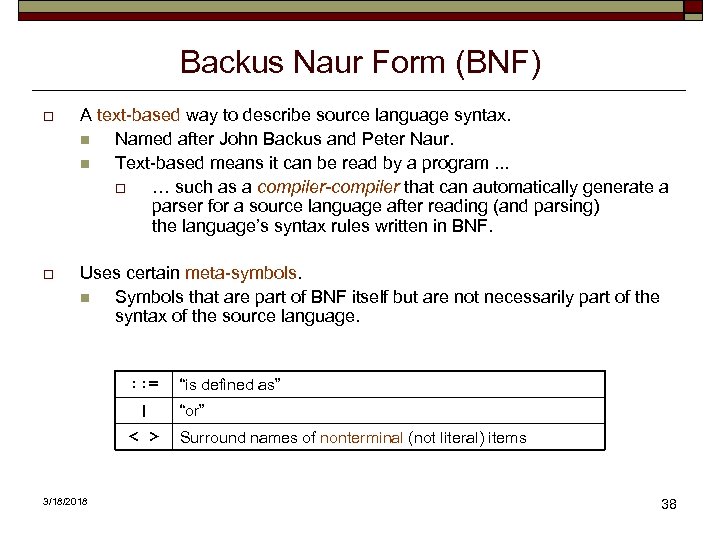

Backus Naur Form (BNF) o A text-based way to describe source language syntax. n Named after John Backus and Peter Naur. n Text-based means it can be read by a program. . . o … such as a compiler-compiler that can automatically generate a parser for a source language after reading (and parsing) the language’s syntax rules written in BNF. o Uses certain meta-symbols. n Symbols that are part of BNF itself but are not necessarily part of the syntax of the source language. : : = | < > 3/18/2018 “is defined as” “or” Surround names of nonterminal (not literal) items 38

Backus Naur Form (BNF) o A text-based way to describe source language syntax. n Named after John Backus and Peter Naur. n Text-based means it can be read by a program. . . o … such as a compiler-compiler that can automatically generate a parser for a source language after reading (and parsing) the language’s syntax rules written in BNF. o Uses certain meta-symbols. n Symbols that are part of BNF itself but are not necessarily part of the syntax of the source language. : : = | < > 3/18/2018 “is defined as” “or” Surround names of nonterminal (not literal) items 38

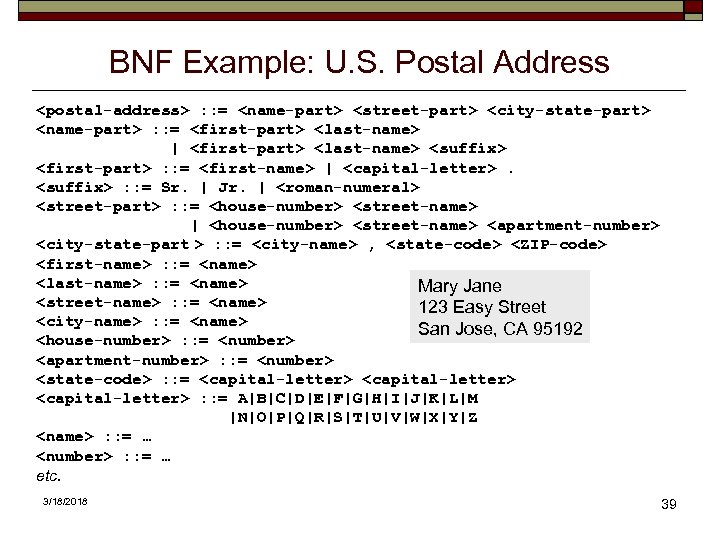

BNF Example: U. S. Postal Address

BNF Example: U. S. Postal Address

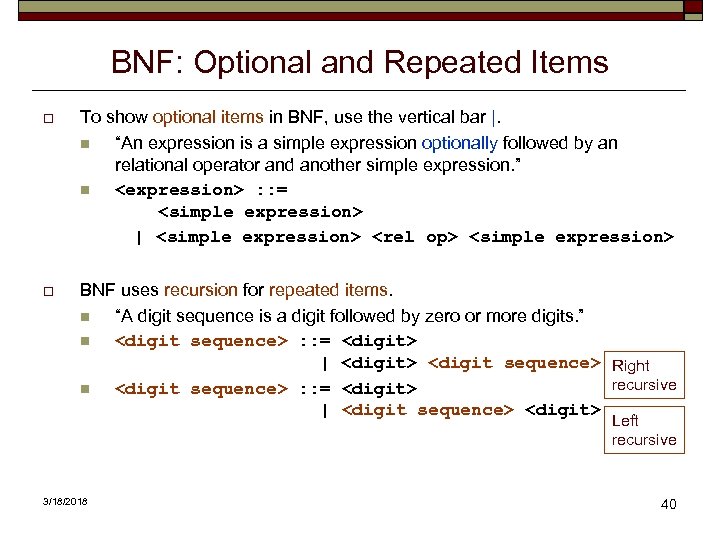

BNF: Optional and Repeated Items o To show optional items in BNF, use the vertical bar |. n “An expression is a simple expression optionally followed by an relational operator and another simple expression. ” n

BNF: Optional and Repeated Items o To show optional items in BNF, use the vertical bar |. n “An expression is a simple expression optionally followed by an relational operator and another simple expression. ” n

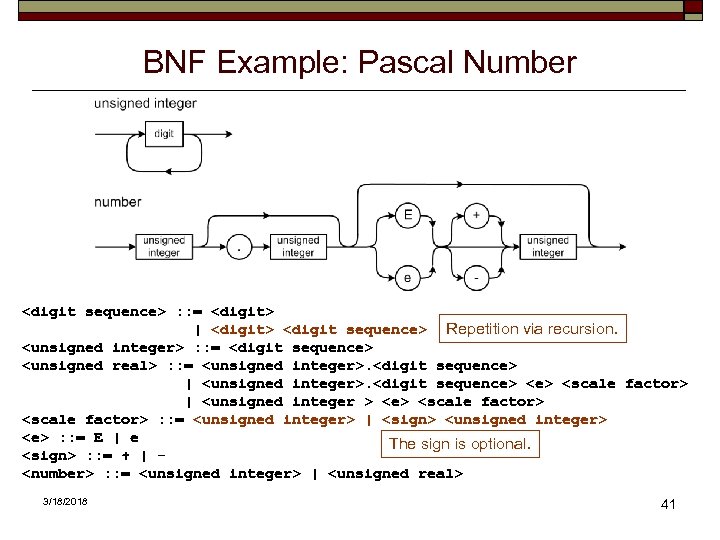

BNF Example: Pascal Number

BNF Example: Pascal Number

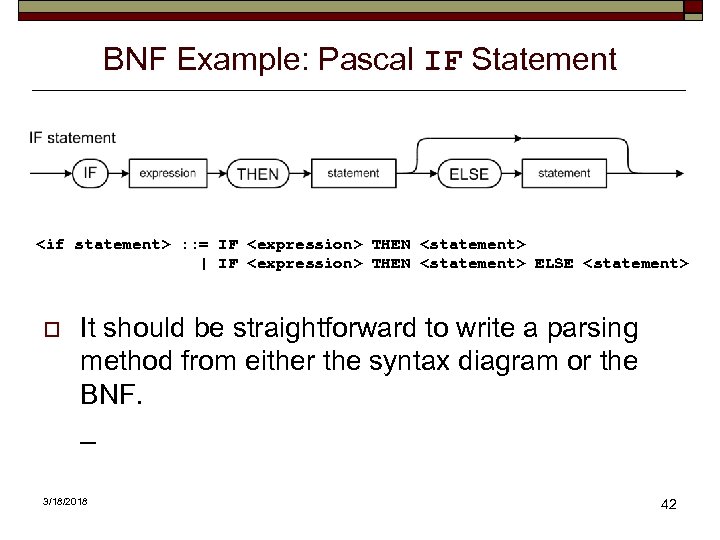

BNF Example: Pascal IF Statement

BNF Example: Pascal IF Statement

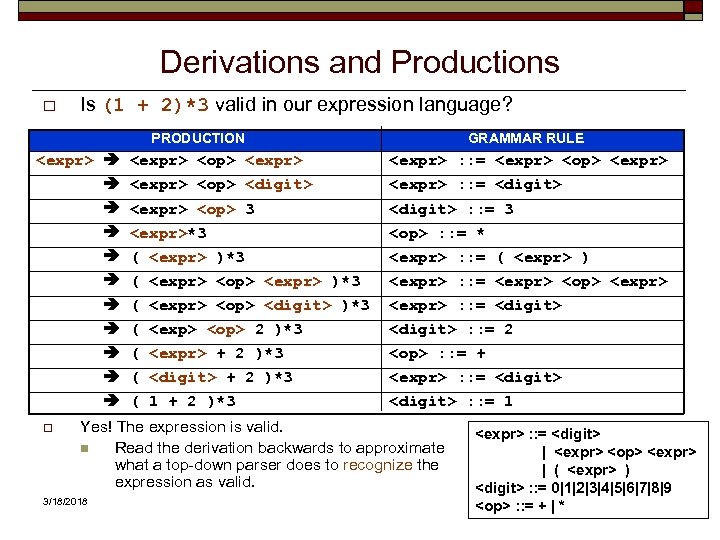

Derivations and Productions o Is (1 + 2)*3 valid in our expression language? PRODUCTION

Derivations and Productions o Is (1 + 2)*3 valid in our expression language? PRODUCTION

![Extended BNF (EBNF) o Extended BNF (EBNF) adds meta-symbols { } and [ ] Extended BNF (EBNF) o Extended BNF (EBNF) adds meta-symbols { } and [ ]](https://present5.com/presentation/d6aaa3f2e605dfb49b39bbb214ffdf9d/image-44.jpg) Extended BNF (EBNF) o Extended BNF (EBNF) adds meta-symbols { } and [ ] { } Surround items to be repeated zero or more times. [ ] Surround optional items. o Originally developed by Niklaus Wirth. n Inventor of Pascal. n Early user of syntax diagrams. o Repetition (one or more): n n 3/18/2018 BNF:

Extended BNF (EBNF) o Extended BNF (EBNF) adds meta-symbols { } and [ ] { } Surround items to be repeated zero or more times. [ ] Surround optional items. o Originally developed by Niklaus Wirth. n Inventor of Pascal. n Early user of syntax diagrams. o Repetition (one or more): n n 3/18/2018 BNF:

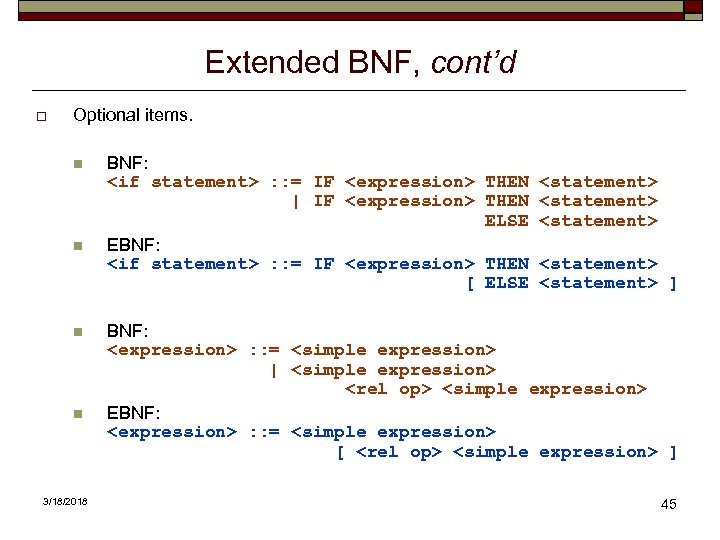

Extended BNF, cont’d o Optional items. n n 3/18/2018 BNF:

Extended BNF, cont’d o Optional items. n n 3/18/2018 BNF:

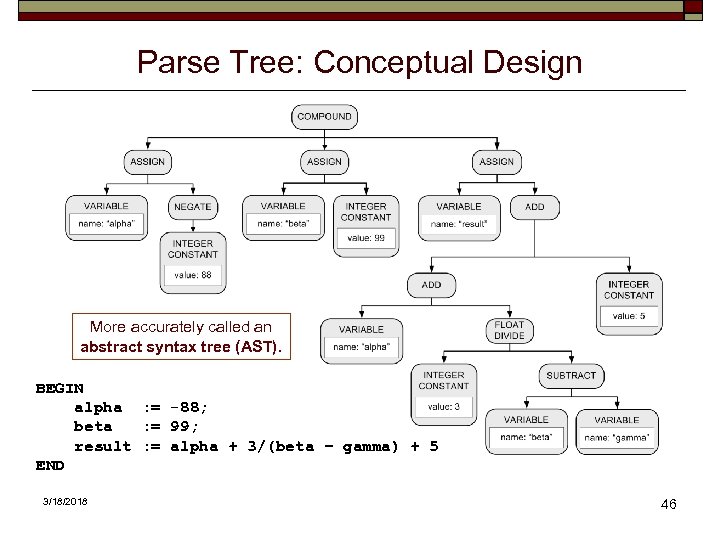

Parse Tree: Conceptual Design More accurately called an abstract syntax tree (AST). BEGIN alpha : = -88; beta : = 99; result : = alpha + 3/(beta – gamma) + 5 END 3/18/2018 46

Parse Tree: Conceptual Design More accurately called an abstract syntax tree (AST). BEGIN alpha : = -88; beta : = 99; result : = alpha + 3/(beta – gamma) + 5 END 3/18/2018 46

Parse Tree: Conceptual Design, cont’d o At the conceptual design level, we don’t care how we implement the tree. n o This should remind you of how we first designed the symbol table. Basic tree operations n n n n 3/18/2018 Create a new node. Create a copy of a node. Set and get the root node of a parse tree. Set and get an attribute value in a node. Add a child node to a node. Get the list of a node’s child nodes. Get a node’s parent node. 47

Parse Tree: Conceptual Design, cont’d o At the conceptual design level, we don’t care how we implement the tree. n o This should remind you of how we first designed the symbol table. Basic tree operations n n n n 3/18/2018 Create a new node. Create a copy of a node. Set and get the root node of a parse tree. Set and get an attribute value in a node. Add a child node to a node. Get the list of a node’s child nodes. Get a node’s parent node. 47

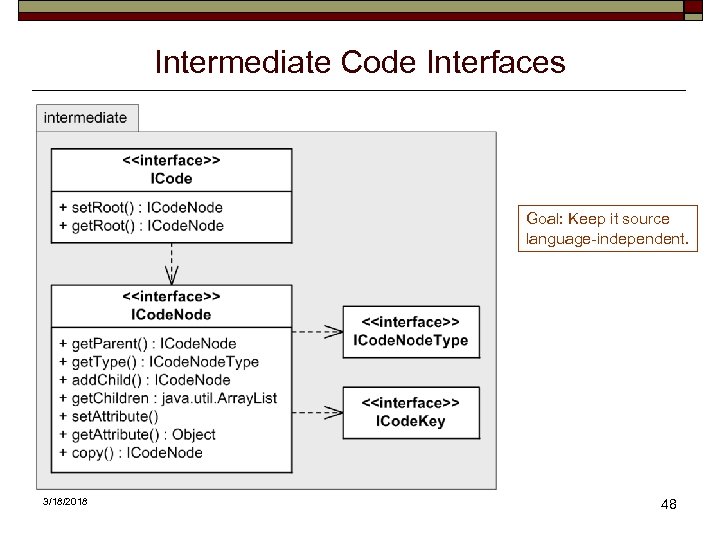

Intermediate Code Interfaces Goal: Keep it source language-independent. 3/18/2018 48

Intermediate Code Interfaces Goal: Keep it source language-independent. 3/18/2018 48

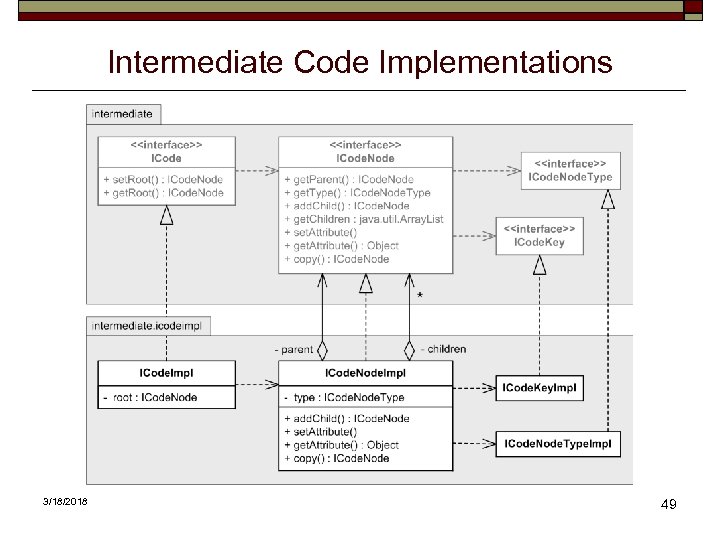

Intermediate Code Implementations 3/18/2018 49

Intermediate Code Implementations 3/18/2018 49

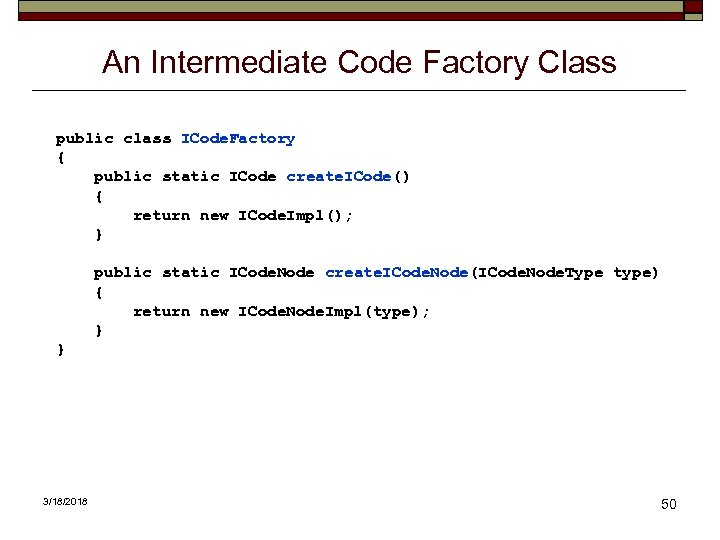

An Intermediate Code Factory Class public class ICode. Factory { public static ICode create. ICode() { return new ICode. Impl(); } public static ICode. Node create. ICode. Node(ICode. Node. Type type) { return new ICode. Node. Impl(type); } } 3/18/2018 50

An Intermediate Code Factory Class public class ICode. Factory { public static ICode create. ICode() { return new ICode. Impl(); } public static ICode. Node create. ICode. Node(ICode. Node. Type type) { return new ICode. Node. Impl(type); } } 3/18/2018 50

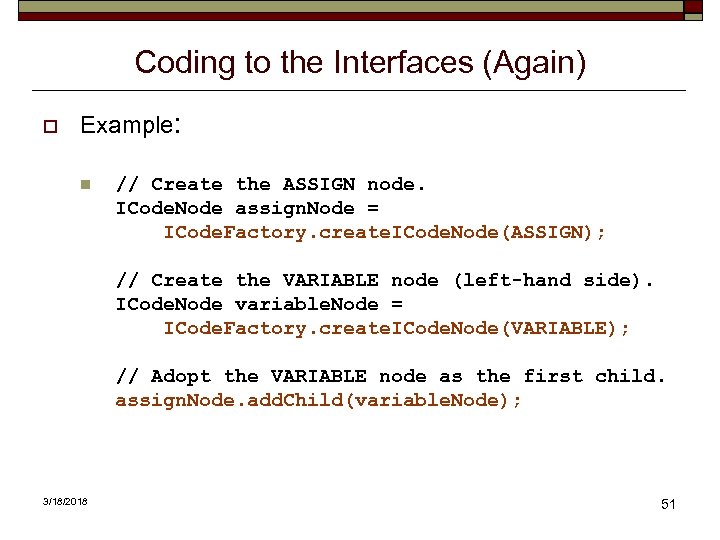

Coding to the Interfaces (Again) o Example: n // Create the ASSIGN node. ICode. Node assign. Node = ICode. Factory. create. ICode. Node(ASSIGN); // Create the VARIABLE node (left-hand side). ICode. Node variable. Node = ICode. Factory. create. ICode. Node(VARIABLE); // Adopt the VARIABLE node as the first child. assign. Node. add. Child(variable. Node); 3/18/2018 51

Coding to the Interfaces (Again) o Example: n // Create the ASSIGN node. ICode. Node assign. Node = ICode. Factory. create. ICode. Node(ASSIGN); // Create the VARIABLE node (left-hand side). ICode. Node variable. Node = ICode. Factory. create. ICode. Node(VARIABLE); // Adopt the VARIABLE node as the first child. assign. Node. add. Child(variable. Node); 3/18/2018 51

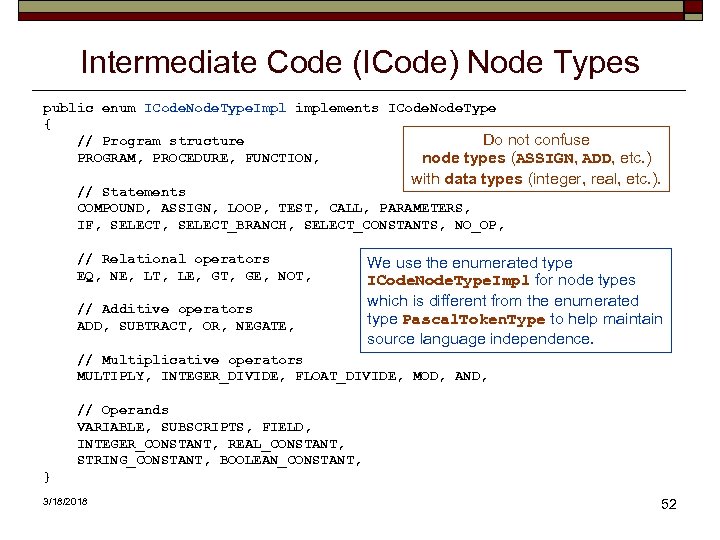

Intermediate Code (ICode) Node Types public enum ICode. Node. Type. Impl implements ICode. Node. Type { Do not confuse // Program structure PROGRAM, PROCEDURE, FUNCTION, node types (ASSIGN, ADD, etc. ) with data types (integer, real, etc. ). // Statements COMPOUND, ASSIGN, LOOP, TEST, CALL, PARAMETERS, IF, SELECT_BRANCH, SELECT_CONSTANTS, NO_OP, // Relational operators EQ, NE, LT, LE, GT, GE, NOT, // Additive operators ADD, SUBTRACT, OR, NEGATE, We use the enumerated type ICode. Node. Type. Impl for node types which is different from the enumerated type Pascal. Token. Type to help maintain source language independence. // Multiplicative operators MULTIPLY, INTEGER_DIVIDE, FLOAT_DIVIDE, MOD, AND, // Operands VARIABLE, SUBSCRIPTS, FIELD, INTEGER_CONSTANT, REAL_CONSTANT, STRING_CONSTANT, BOOLEAN_CONSTANT, } 3/18/2018 52

Intermediate Code (ICode) Node Types public enum ICode. Node. Type. Impl implements ICode. Node. Type { Do not confuse // Program structure PROGRAM, PROCEDURE, FUNCTION, node types (ASSIGN, ADD, etc. ) with data types (integer, real, etc. ). // Statements COMPOUND, ASSIGN, LOOP, TEST, CALL, PARAMETERS, IF, SELECT_BRANCH, SELECT_CONSTANTS, NO_OP, // Relational operators EQ, NE, LT, LE, GT, GE, NOT, // Additive operators ADD, SUBTRACT, OR, NEGATE, We use the enumerated type ICode. Node. Type. Impl for node types which is different from the enumerated type Pascal. Token. Type to help maintain source language independence. // Multiplicative operators MULTIPLY, INTEGER_DIVIDE, FLOAT_DIVIDE, MOD, AND, // Operands VARIABLE, SUBSCRIPTS, FIELD, INTEGER_CONSTANT, REAL_CONSTANT, STRING_CONSTANT, BOOLEAN_CONSTANT, } 3/18/2018 52

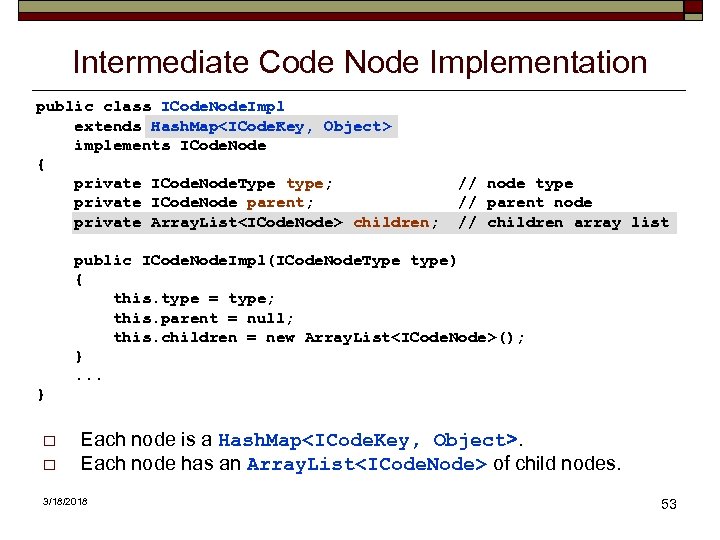

Intermediate Code Node Implementation public class ICode. Node. Impl extends Hash. Map

Intermediate Code Node Implementation public class ICode. Node. Impl extends Hash. Map

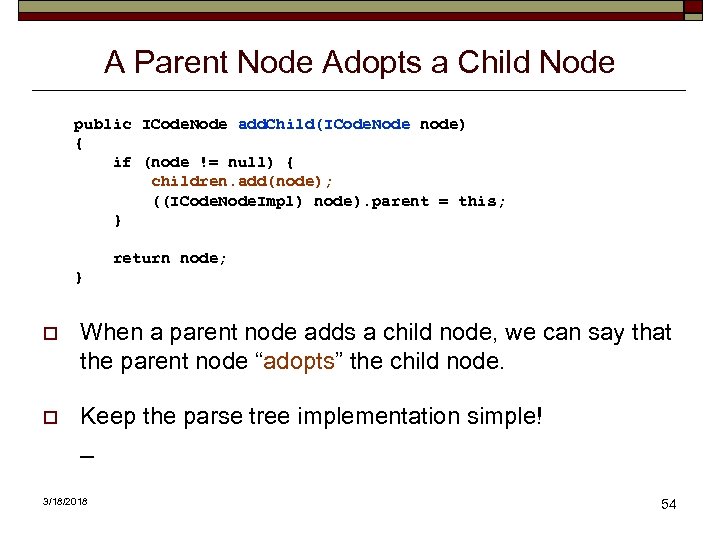

A Parent Node Adopts a Child Node public ICode. Node add. Child(ICode. Node node) { if (node != null) { children. add(node); ((ICode. Node. Impl) node). parent = this; } return node; } o When a parent node adds a child node, we can say that the parent node “adopts” the child node. o Keep the parse tree implementation simple! _ 3/18/2018 54

A Parent Node Adopts a Child Node public ICode. Node add. Child(ICode. Node node) { if (node != null) { children. add(node); ((ICode. Node. Impl) node). parent = this; } return node; } o When a parent node adds a child node, we can say that the parent node “adopts” the child node. o Keep the parse tree implementation simple! _ 3/18/2018 54

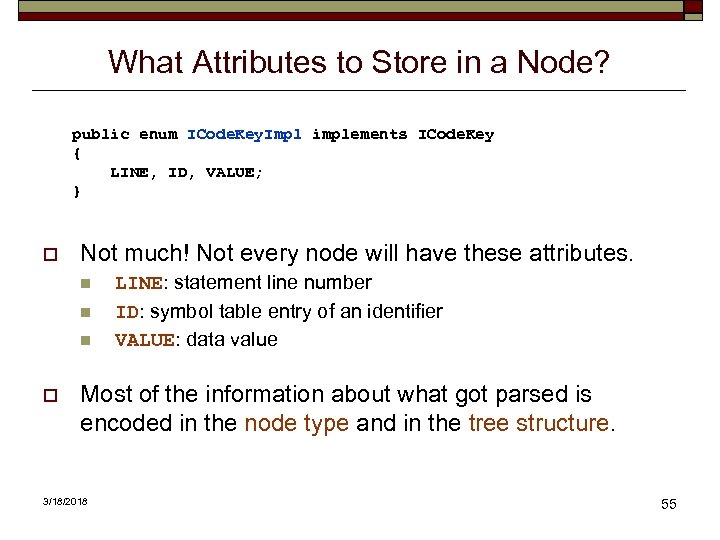

What Attributes to Store in a Node? public enum ICode. Key. Impl implements ICode. Key { LINE, ID, VALUE; } o Not much! Not every node will have these attributes. n n n o LINE: statement line number ID: symbol table entry of an identifier VALUE: data value Most of the information about what got parsed is encoded in the node type and in the tree structure. 3/18/2018 55

What Attributes to Store in a Node? public enum ICode. Key. Impl implements ICode. Key { LINE, ID, VALUE; } o Not much! Not every node will have these attributes. n n n o LINE: statement line number ID: symbol table entry of an identifier VALUE: data value Most of the information about what got parsed is encoded in the node type and in the tree structure. 3/18/2018 55

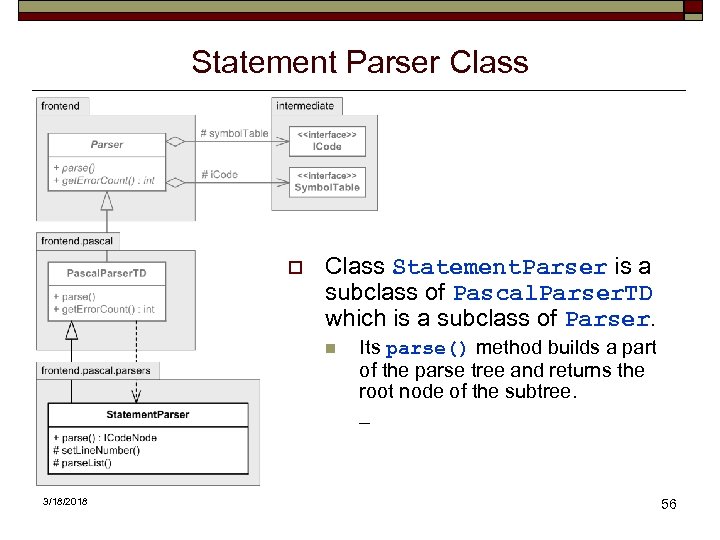

Statement Parser Class o Class Statement. Parser is a subclass of Pascal. Parser. TD which is a subclass of Parser. n 3/18/2018 Its parse() method builds a part of the parse tree and returns the root node of the subtree. _ 56

Statement Parser Class o Class Statement. Parser is a subclass of Pascal. Parser. TD which is a subclass of Parser. n 3/18/2018 Its parse() method builds a part of the parse tree and returns the root node of the subtree. _ 56

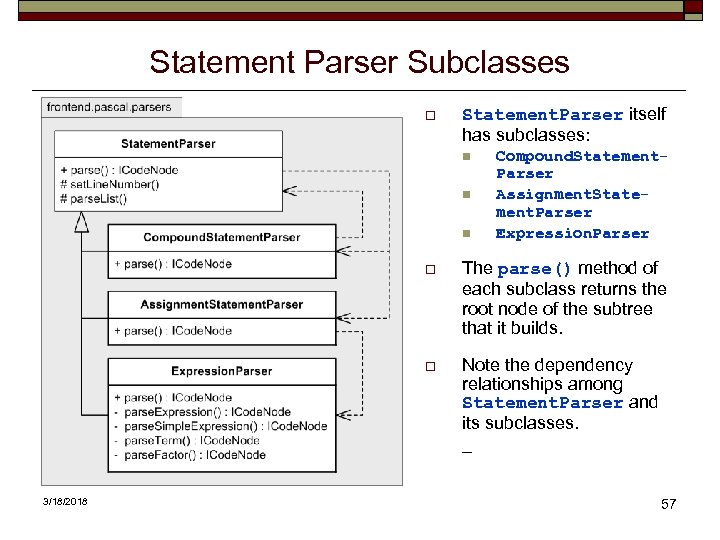

Statement Parser Subclasses o Statement. Parser itself has subclasses: n n n Compound. Statement. Parser Assignment. Statement. Parser Expression. Parser o o 3/18/2018 The parse() method of each subclass returns the root node of the subtree that it builds. Note the dependency relationships among Statement. Parser and its subclasses. _ 57

Statement Parser Subclasses o Statement. Parser itself has subclasses: n n n Compound. Statement. Parser Assignment. Statement. Parser Expression. Parser o o 3/18/2018 The parse() method of each subclass returns the root node of the subtree that it builds. Note the dependency relationships among Statement. Parser and its subclasses. _ 57

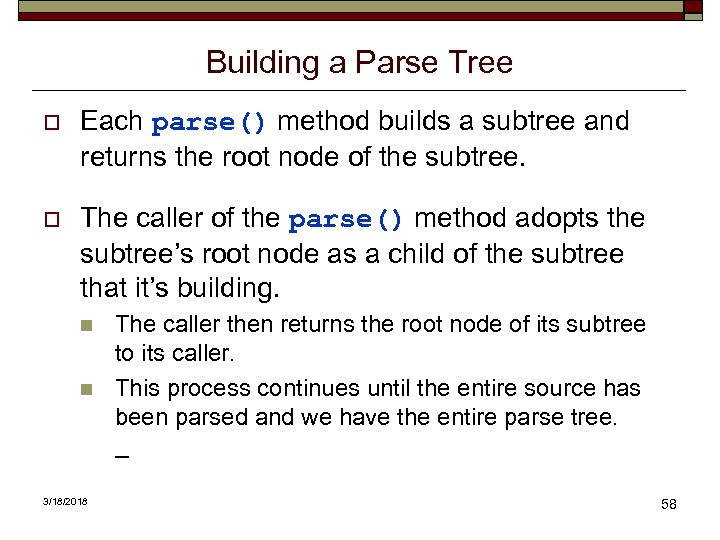

Building a Parse Tree o Each parse() method builds a subtree and returns the root node of the subtree. o The caller of the parse() method adopts the subtree’s root node as a child of the subtree that it’s building. n n 3/18/2018 The caller then returns the root node of its subtree to its caller. This process continues until the entire source has been parsed and we have the entire parse tree. _ 58

Building a Parse Tree o Each parse() method builds a subtree and returns the root node of the subtree. o The caller of the parse() method adopts the subtree’s root node as a child of the subtree that it’s building. n n 3/18/2018 The caller then returns the root node of its subtree to its caller. This process continues until the entire source has been parsed and we have the entire parse tree. _ 58

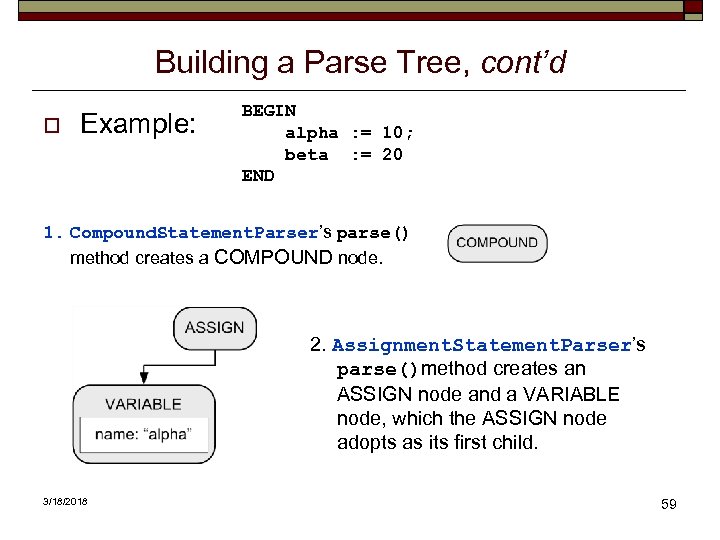

Building a Parse Tree, cont’d o Example: BEGIN alpha : = 10; beta : = 20 END 1. Compound. Statement. Parser’s parse() method creates a COMPOUND node. 2. Assignment. Statement. Parser’s parse()method creates an ASSIGN node and a VARIABLE node, which the ASSIGN node adopts as its first child. 3/18/2018 59

Building a Parse Tree, cont’d o Example: BEGIN alpha : = 10; beta : = 20 END 1. Compound. Statement. Parser’s parse() method creates a COMPOUND node. 2. Assignment. Statement. Parser’s parse()method creates an ASSIGN node and a VARIABLE node, which the ASSIGN node adopts as its first child. 3/18/2018 59

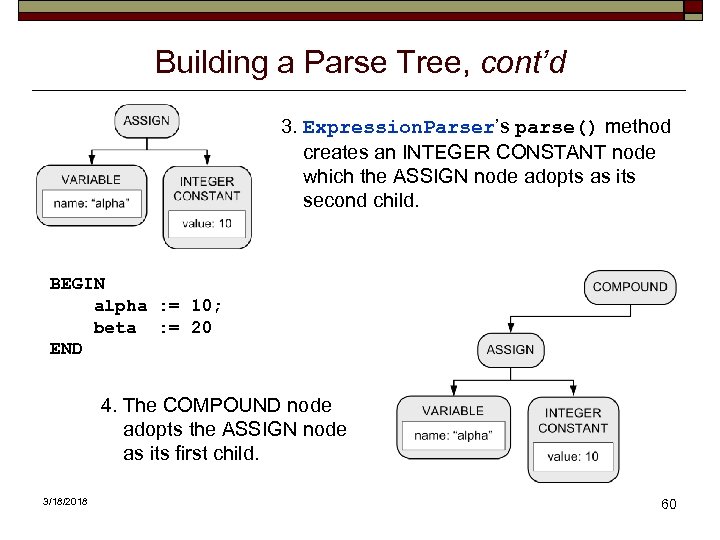

Building a Parse Tree, cont’d 3. Expression. Parser’s parse() method creates an INTEGER CONSTANT node which the ASSIGN node adopts as its second child. BEGIN alpha : = 10; beta : = 20 END 4. The COMPOUND node adopts the ASSIGN node as its first child. 3/18/2018 60

Building a Parse Tree, cont’d 3. Expression. Parser’s parse() method creates an INTEGER CONSTANT node which the ASSIGN node adopts as its second child. BEGIN alpha : = 10; beta : = 20 END 4. The COMPOUND node adopts the ASSIGN node as its first child. 3/18/2018 60

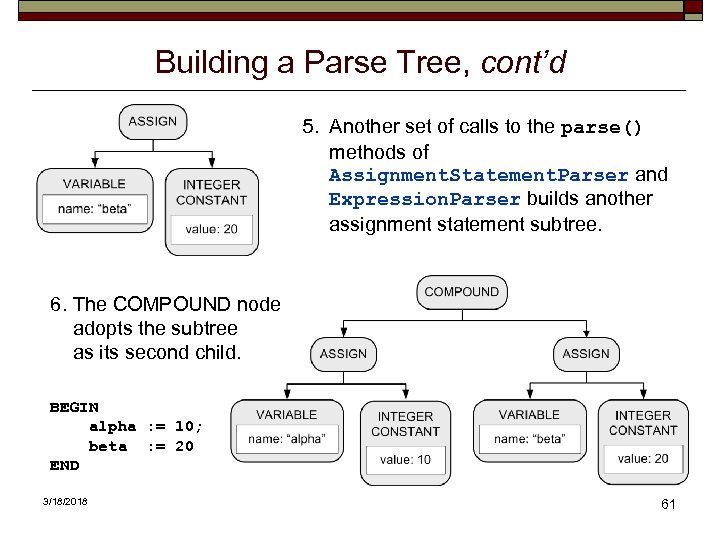

Building a Parse Tree, cont’d 5. Another set of calls to the parse() methods of Assignment. Statement. Parser and Expression. Parser builds another assignment statement subtree. 6. The COMPOUND node adopts the subtree as its second child. BEGIN alpha : = 10; beta : = 20 END 3/18/2018 61

Building a Parse Tree, cont’d 5. Another set of calls to the parse() methods of Assignment. Statement. Parser and Expression. Parser builds another assignment statement subtree. 6. The COMPOUND node adopts the subtree as its second child. BEGIN alpha : = 10; beta : = 20 END 3/18/2018 61

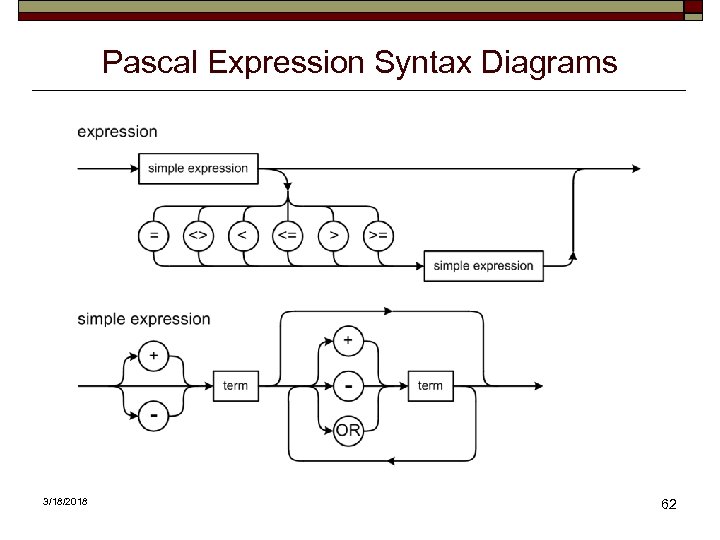

Pascal Expression Syntax Diagrams 3/18/2018 62

Pascal Expression Syntax Diagrams 3/18/2018 62

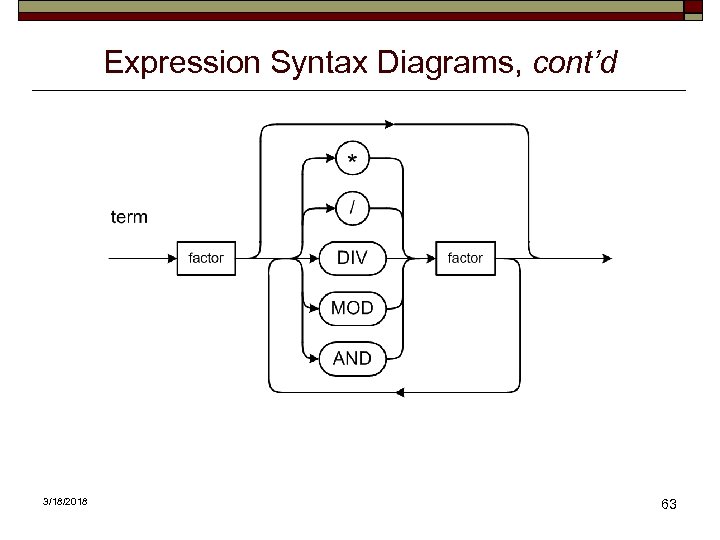

Expression Syntax Diagrams, cont’d 3/18/2018 63

Expression Syntax Diagrams, cont’d 3/18/2018 63

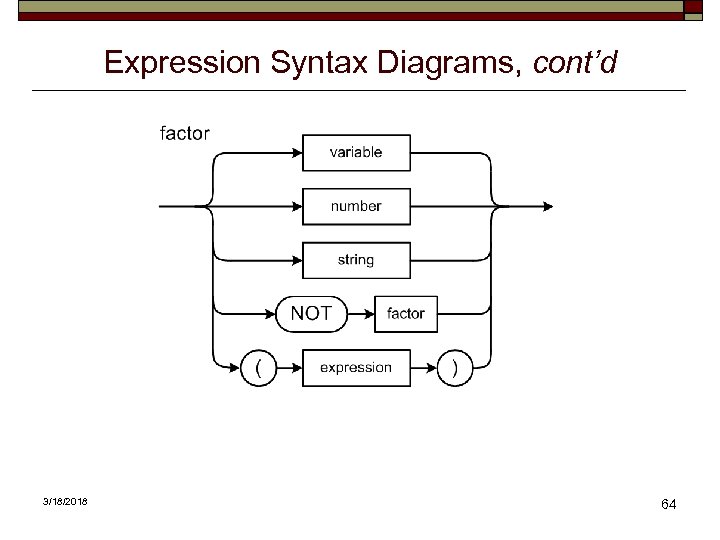

Expression Syntax Diagrams, cont’d 3/18/2018 64

Expression Syntax Diagrams, cont’d 3/18/2018 64

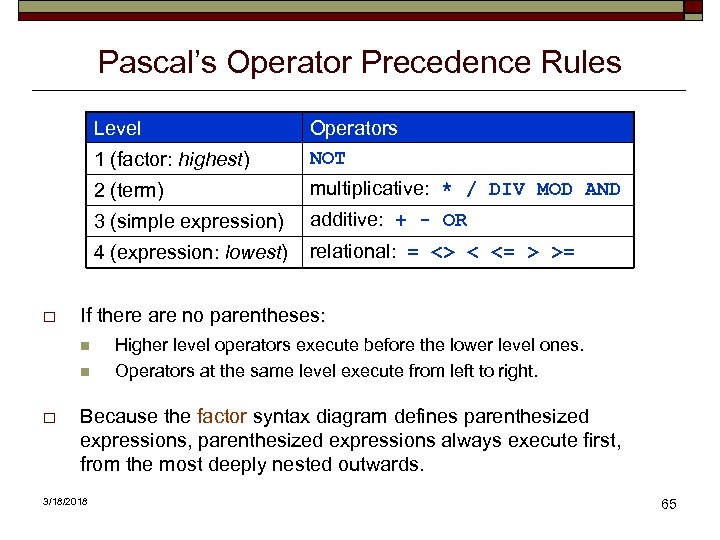

Pascal’s Operator Precedence Rules Level 1 (factor: highest) 2 (term) additive: + - OR 4 (expression: lowest) relational: = <> < <= > >= If there are no parentheses: n n o multiplicative: * / DIV MOD AND 3 (simple expression) o Operators NOT Higher level operators execute before the lower level ones. Operators at the same level execute from left to right. Because the factor syntax diagram defines parenthesized expressions, parenthesized expressions always execute first, from the most deeply nested outwards. 3/18/2018 65

Pascal’s Operator Precedence Rules Level 1 (factor: highest) 2 (term) additive: + - OR 4 (expression: lowest) relational: = <> < <= > >= If there are no parentheses: n n o multiplicative: * / DIV MOD AND 3 (simple expression) o Operators NOT Higher level operators execute before the lower level ones. Operators at the same level execute from left to right. Because the factor syntax diagram defines parenthesized expressions, parenthesized expressions always execute first, from the most deeply nested outwards. 3/18/2018 65

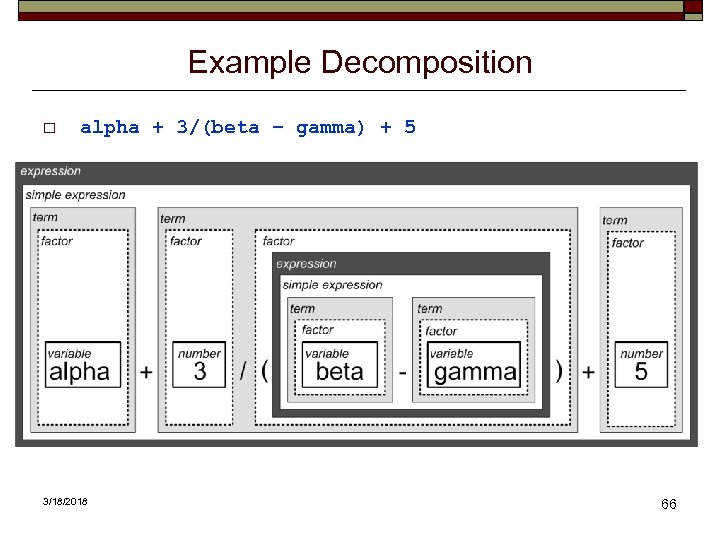

Example Decomposition o alpha + 3/(beta – gamma) + 5 3/18/2018 66

Example Decomposition o alpha + 3/(beta – gamma) + 5 3/18/2018 66

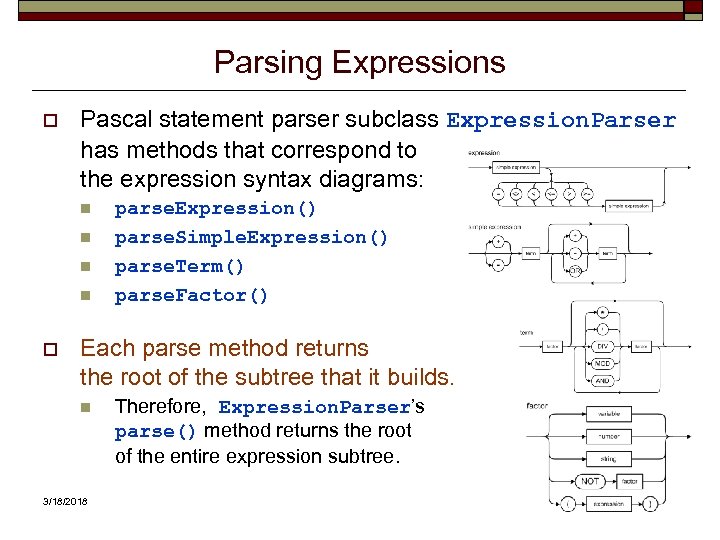

Parsing Expressions o Pascal statement parser subclass Expression. Parser has methods that correspond to the expression syntax diagrams: n n o parse. Expression() parse. Simple. Expression() parse. Term() parse. Factor() Each parse method returns the root of the subtree that it builds. n 3/18/2018 Therefore, Expression. Parser’s parse() method returns the root of the entire expression subtree. 67

Parsing Expressions o Pascal statement parser subclass Expression. Parser has methods that correspond to the expression syntax diagrams: n n o parse. Expression() parse. Simple. Expression() parse. Term() parse. Factor() Each parse method returns the root of the subtree that it builds. n 3/18/2018 Therefore, Expression. Parser’s parse() method returns the root of the entire expression subtree. 67

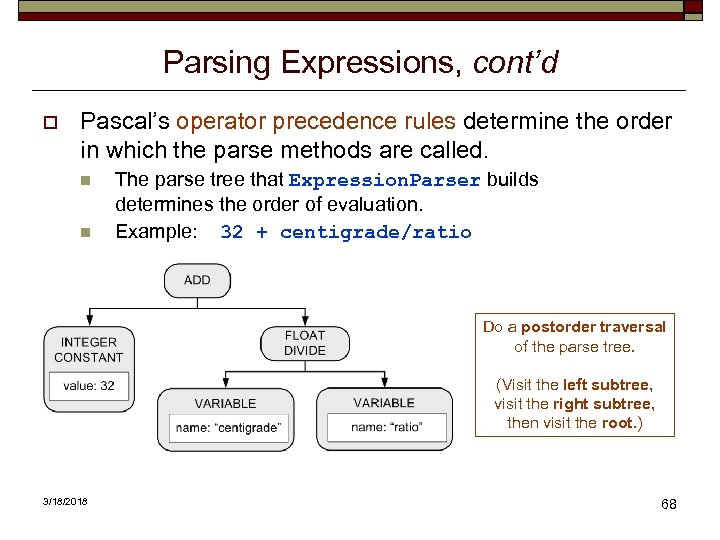

Parsing Expressions, cont’d o Pascal’s operator precedence rules determine the order in which the parse methods are called. n n The parse tree that Expression. Parser builds determines the order of evaluation. Example: 32 + centigrade/ratio Do a postorder traversal of the parse tree. (Visit the left subtree, visit the right subtree, then visit the root. ) 3/18/2018 68

Parsing Expressions, cont’d o Pascal’s operator precedence rules determine the order in which the parse methods are called. n n The parse tree that Expression. Parser builds determines the order of evaluation. Example: 32 + centigrade/ratio Do a postorder traversal of the parse tree. (Visit the left subtree, visit the right subtree, then visit the root. ) 3/18/2018 68

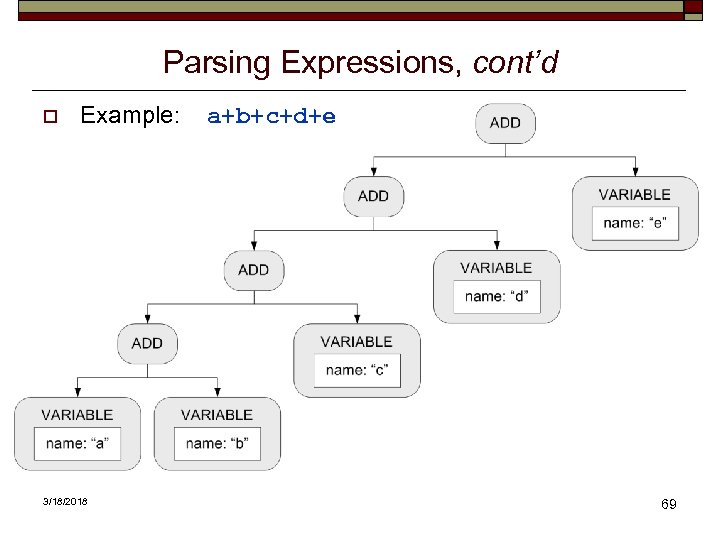

Parsing Expressions, cont’d o Example: 3/18/2018 a+b+c+d+e 69

Parsing Expressions, cont’d o Example: 3/18/2018 a+b+c+d+e 69

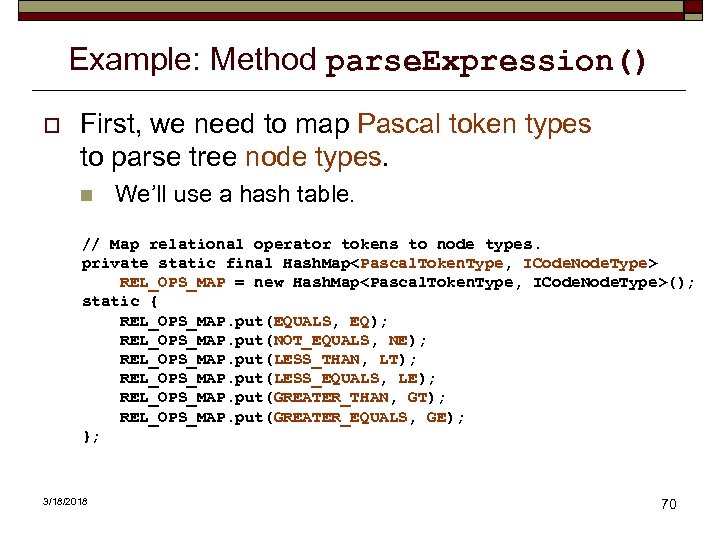

Example: Method parse. Expression() o First, we need to map Pascal token types to parse tree node types. n We’ll use a hash table. // Map relational operator tokens to node types. private static final Hash. Map

Example: Method parse. Expression() o First, we need to map Pascal token types to parse tree node types. n We’ll use a hash table. // Map relational operator tokens to node types. private static final Hash. Map

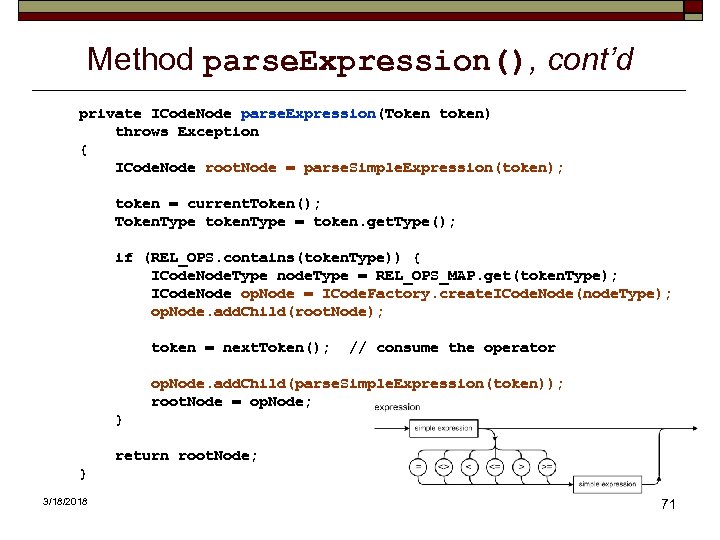

Method parse. Expression(), cont’d private ICode. Node parse. Expression(Token token) throws Exception { ICode. Node root. Node = parse. Simple. Expression(token); token = current. Token(); Token. Type token. Type = token. get. Type(); if (REL_OPS. contains(token. Type)) { ICode. Node. Type node. Type = REL_OPS_MAP. get(token. Type); ICode. Node op. Node = ICode. Factory. create. ICode. Node(node. Type); op. Node. add. Child(root. Node); token = next. Token(); // consume the operator op. Node. add. Child(parse. Simple. Expression(token)); root. Node = op. Node; } return root. Node; } 3/18/2018 71

Method parse. Expression(), cont’d private ICode. Node parse. Expression(Token token) throws Exception { ICode. Node root. Node = parse. Simple. Expression(token); token = current. Token(); Token. Type token. Type = token. get. Type(); if (REL_OPS. contains(token. Type)) { ICode. Node. Type node. Type = REL_OPS_MAP. get(token. Type); ICode. Node op. Node = ICode. Factory. create. ICode. Node(node. Type); op. Node. add. Child(root. Node); token = next. Token(); // consume the operator op. Node. add. Child(parse. Simple. Expression(token)); root. Node = op. Node; } return root. Node; } 3/18/2018 71

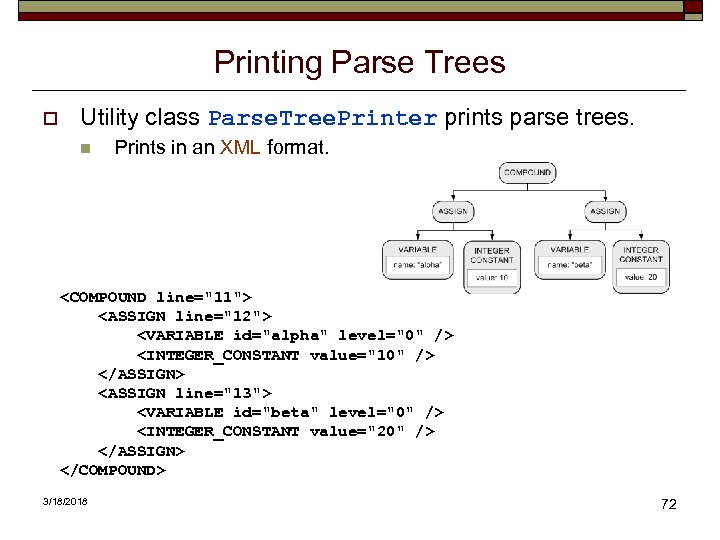

Printing Parse Trees o Utility class Parse. Tree. Printer prints parse trees. n Prints in an XML format.

Printing Parse Trees o Utility class Parse. Tree. Printer prints parse trees. n Prints in an XML format.

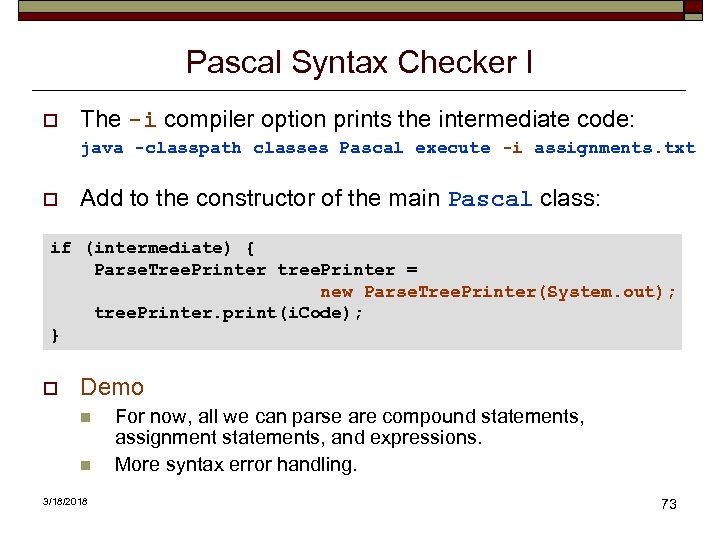

Pascal Syntax Checker I o The -i compiler option prints the intermediate code: java -classpath classes Pascal execute -i assignments. txt o Add to the constructor of the main Pascal class: if (intermediate) { Parse. Tree. Printer tree. Printer = new Parse. Tree. Printer(System. out); tree. Printer. print(i. Code); } o Demo n n 3/18/2018 For now, all we can parse are compound statements, assignment statements, and expressions. More syntax error handling. 73

Pascal Syntax Checker I o The -i compiler option prints the intermediate code: java -classpath classes Pascal execute -i assignments. txt o Add to the constructor of the main Pascal class: if (intermediate) { Parse. Tree. Printer tree. Printer = new Parse. Tree. Printer(System. out); tree. Printer. print(i. Code); } o Demo n n 3/18/2018 For now, all we can parse are compound statements, assignment statements, and expressions. More syntax error handling. 73