1d074fc00be779bb957d3cdeb132abda.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 34

CS 395 T: Program Synthesis for Heterogeneous Parallel Computers

CS 395 T: Program Synthesis for Heterogeneous Parallel Computers

Administration • Instructor: Keshav Pingali – Professor (CS, ICES) – Office: POB 4. 126 A – Email: pingali@cs. utexas. edu • TA: Michael He – Graduate student (CS) – Office: POB 4. 104 – Email: hejy@cs. utexas. edu Website for course http: //www. cs. utexas. edu/users/pingali/CS 395 T-2017/index. html

Administration • Instructor: Keshav Pingali – Professor (CS, ICES) – Office: POB 4. 126 A – Email: pingali@cs. utexas. edu • TA: Michael He – Graduate student (CS) – Office: POB 4. 104 – Email: hejy@cs. utexas. edu Website for course http: //www. cs. utexas. edu/users/pingali/CS 395 T-2017/index. html

Meeting times • Lecture: – TTh 12: 30 -2: 00 PM, GDC 2. 210 • Office hours: – Keshav Pingali: Tuesday 3 -4 PM, POB 4. 126

Meeting times • Lecture: – TTh 12: 30 -2: 00 PM, GDC 2. 210 • Office hours: – Keshav Pingali: Tuesday 3 -4 PM, POB 4. 126

Prerequisites • Compilers and architecture – Graduate level knowledge – Compilers: CS 380 C, Architecture: H&P book • Software and math maturity – Able to implement large programs – Familiarity with concepts like SAT solvers and if not, the ability to learn that material on your own • Research maturity – Ability to read papers on your own and understand the key ideas

Prerequisites • Compilers and architecture – Graduate level knowledge – Compilers: CS 380 C, Architecture: H&P book • Software and math maturity – Able to implement large programs – Familiarity with concepts like SAT solvers and if not, the ability to learn that material on your own • Research maturity – Ability to read papers on your own and understand the key ideas

Course organization • This is a paper reading course • Papers: – In every class, we will discuss one or two papers – One student will give a 30 min-45 min presentation of the content of these papers at the beginning of each class – Rest of class time will be devoted to a discussion of the paper(s) – Website will have the papers and discussion order

Course organization • This is a paper reading course • Papers: – In every class, we will discuss one or two papers – One student will give a 30 min-45 min presentation of the content of these papers at the beginning of each class – Rest of class time will be devoted to a discussion of the paper(s) – Website will have the papers and discussion order

Coursework • Writing assignments (20% of grade) – Everyone is expected to read all papers – Reading reports: submit as private note to Michael on Piazza. See Michael’s sample on website. – Deadline: Sunday 11: 59 PM for papers that we will discuss on the following Tuesday and Thursday. • Class participation (20% of grade) • Term project (60% of grade) – Substantial implementation project – Based on our ideas or yours – Work alone or in pairs

Coursework • Writing assignments (20% of grade) – Everyone is expected to read all papers – Reading reports: submit as private note to Michael on Piazza. See Michael’s sample on website. – Deadline: Sunday 11: 59 PM for papers that we will discuss on the following Tuesday and Thursday. • Class participation (20% of grade) • Term project (60% of grade) – Substantial implementation project – Based on our ideas or yours – Work alone or in pairs

Course concerns • Two main concerns in programming – Performance – Productivity • These concerns are often in tension • Performance – Modern processors are very complex – Getting performance may require low-level programming • Productivity – Improving productivity requires higher levels of abstraction in application programs • How can we get both productivity and performance? – Need powerful approaches to convert high-level abstract programs to low-level efficient programs

Course concerns • Two main concerns in programming – Performance – Productivity • These concerns are often in tension • Performance – Modern processors are very complex – Getting performance may require low-level programming • Productivity – Improving productivity requires higher levels of abstraction in application programs • How can we get both productivity and performance? – Need powerful approaches to convert high-level abstract programs to low-level efficient programs

Performance

Performance

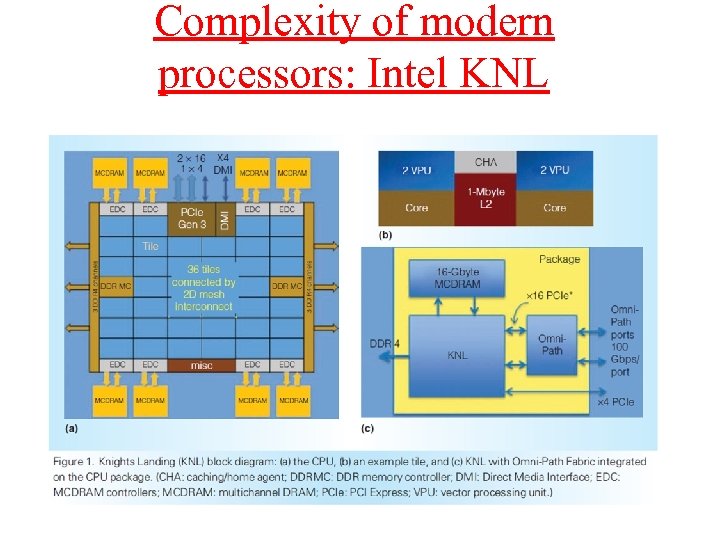

Complexity of modern processors: Intel KNL

Complexity of modern processors: Intel KNL

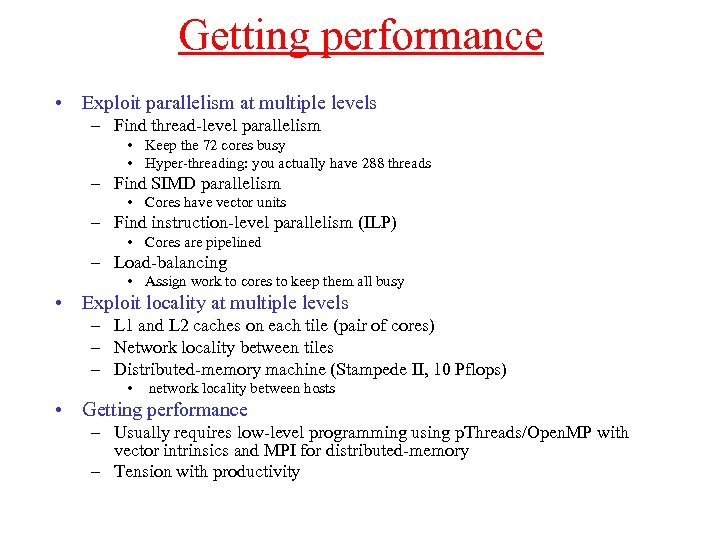

Getting performance • Exploit parallelism at multiple levels – Find thread-level parallelism • Keep the 72 cores busy • Hyper-threading: you actually have 288 threads – Find SIMD parallelism • Cores have vector units – Find instruction-level parallelism (ILP) • Cores are pipelined – Load-balancing • Assign work to cores to keep them all busy • Exploit locality at multiple levels – L 1 and L 2 caches on each tile (pair of cores) – Network locality between tiles – Distributed-memory machine (Stampede II, 10 Pflops) • network locality between hosts • Getting performance – Usually requires low-level programming using p. Threads/Open. MP with vector intrinsics and MPI for distributed-memory – Tension with productivity

Getting performance • Exploit parallelism at multiple levels – Find thread-level parallelism • Keep the 72 cores busy • Hyper-threading: you actually have 288 threads – Find SIMD parallelism • Cores have vector units – Find instruction-level parallelism (ILP) • Cores are pipelined – Load-balancing • Assign work to cores to keep them all busy • Exploit locality at multiple levels – L 1 and L 2 caches on each tile (pair of cores) – Network locality between tiles – Distributed-memory machine (Stampede II, 10 Pflops) • network locality between hosts • Getting performance – Usually requires low-level programming using p. Threads/Open. MP with vector intrinsics and MPI for distributed-memory – Tension with productivity

Productivity

Productivity

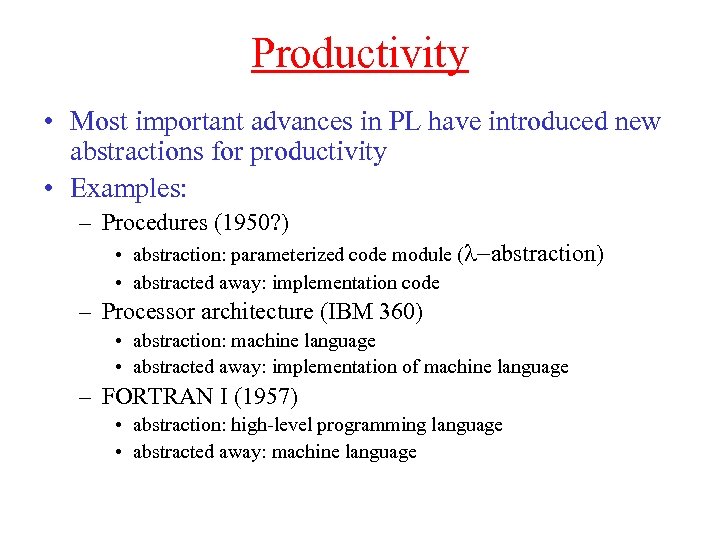

Productivity • Most important advances in PL have introduced new abstractions for productivity • Examples: – Procedures (1950? ) • abstraction: parameterized code module (l-abstraction) • abstracted away: implementation code – Processor architecture (IBM 360) • abstraction: machine language • abstracted away: implementation of machine language – FORTRAN I (1957) • abstraction: high-level programming language • abstracted away: machine language

Productivity • Most important advances in PL have introduced new abstractions for productivity • Examples: – Procedures (1950? ) • abstraction: parameterized code module (l-abstraction) • abstracted away: implementation code – Processor architecture (IBM 360) • abstraction: machine language • abstracted away: implementation of machine language – FORTRAN I (1957) • abstraction: high-level programming language • abstracted away: machine language

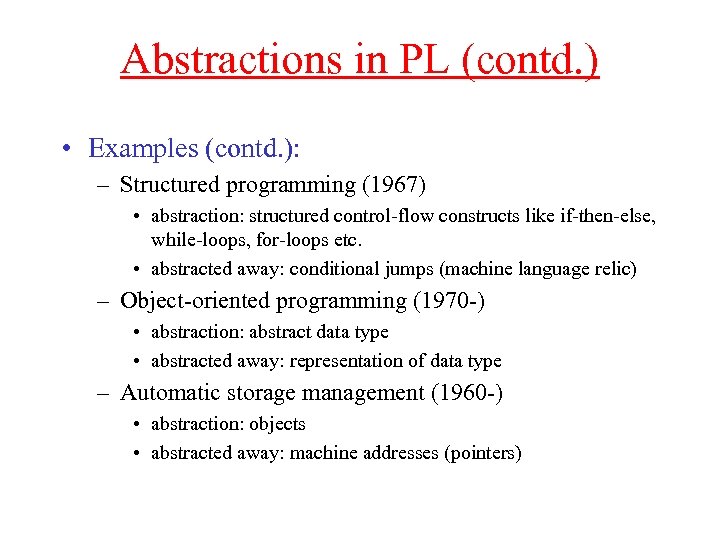

Abstractions in PL (contd. ) • Examples (contd. ): – Structured programming (1967) • abstraction: structured control-flow constructs like if-then-else, while-loops, for-loops etc. • abstracted away: conditional jumps (machine language relic) – Object-oriented programming (1970 -) • abstraction: abstract data type • abstracted away: representation of data type – Automatic storage management (1960 -) • abstraction: objects • abstracted away: machine addresses (pointers)

Abstractions in PL (contd. ) • Examples (contd. ): – Structured programming (1967) • abstraction: structured control-flow constructs like if-then-else, while-loops, for-loops etc. • abstracted away: conditional jumps (machine language relic) – Object-oriented programming (1970 -) • abstraction: abstract data type • abstracted away: representation of data type – Automatic storage management (1960 -) • abstraction: objects • abstracted away: machine addresses (pointers)

Abstractions for parallelism? • What are the right abstractions for parallel programming? – Very difficult problem: roughly 50 years of work but no agreement – Lots of proposals: • • • Functional languages, dataflow languages: Dennis, Arvind Logic programming languages: Warren, Ueda Concurrent Sequential Processes (CSP): Hoare Bulk-synchronous parallel (BSP) programming: Valiant Unity: Chandy/Misra

Abstractions for parallelism? • What are the right abstractions for parallel programming? – Very difficult problem: roughly 50 years of work but no agreement – Lots of proposals: • • • Functional languages, dataflow languages: Dennis, Arvind Logic programming languages: Warren, Ueda Concurrent Sequential Processes (CSP): Hoare Bulk-synchronous parallel (BSP) programming: Valiant Unity: Chandy/Misra

What we will study • Domain-independent abstraction – Operator formulation of algorithms (my group) – Motto: Parallel program = Operator + Schedule + Parallel data structures • Domain-specific abstractions – most problem domains have some underlying computational algebra (e. g. databases and relational algebra) – programs are expressions in that algebra and can be optimized using algebraic identities

What we will study • Domain-independent abstraction – Operator formulation of algorithms (my group) – Motto: Parallel program = Operator + Schedule + Parallel data structures • Domain-specific abstractions – most problem domains have some underlying computational algebra (e. g. databases and relational algebra) – programs are expressions in that algebra and can be optimized using algebraic identities

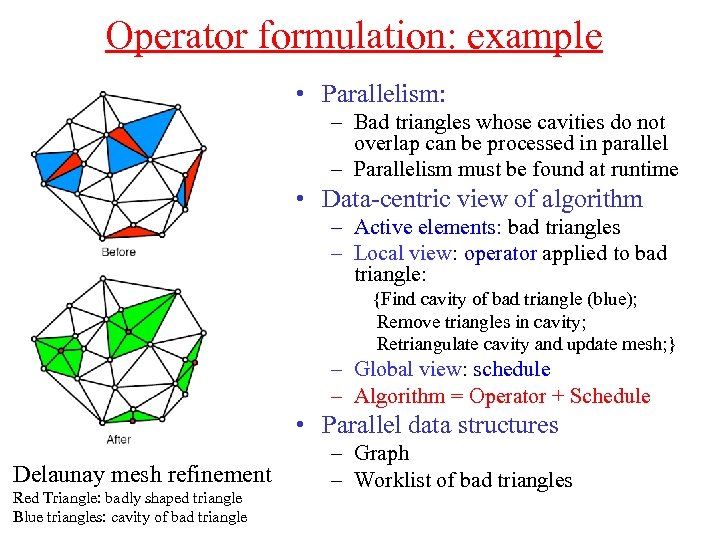

Operator formulation: example • Parallelism: – Bad triangles whose cavities do not overlap can be processed in parallel – Parallelism must be found at runtime • Data-centric view of algorithm – Active elements: bad triangles – Local view: operator applied to bad triangle: {Find cavity of bad triangle (blue); Remove triangles in cavity; Retriangulate cavity and update mesh; } – Global view: schedule – Algorithm = Operator + Schedule • Parallel data structures Delaunay mesh refinement Red Triangle: badly shaped triangle Blue triangles: cavity of bad triangle – Graph – Worklist of bad triangles

Operator formulation: example • Parallelism: – Bad triangles whose cavities do not overlap can be processed in parallel – Parallelism must be found at runtime • Data-centric view of algorithm – Active elements: bad triangles – Local view: operator applied to bad triangle: {Find cavity of bad triangle (blue); Remove triangles in cavity; Retriangulate cavity and update mesh; } – Global view: schedule – Algorithm = Operator + Schedule • Parallel data structures Delaunay mesh refinement Red Triangle: badly shaped triangle Blue triangles: cavity of bad triangle – Graph – Worklist of bad triangles

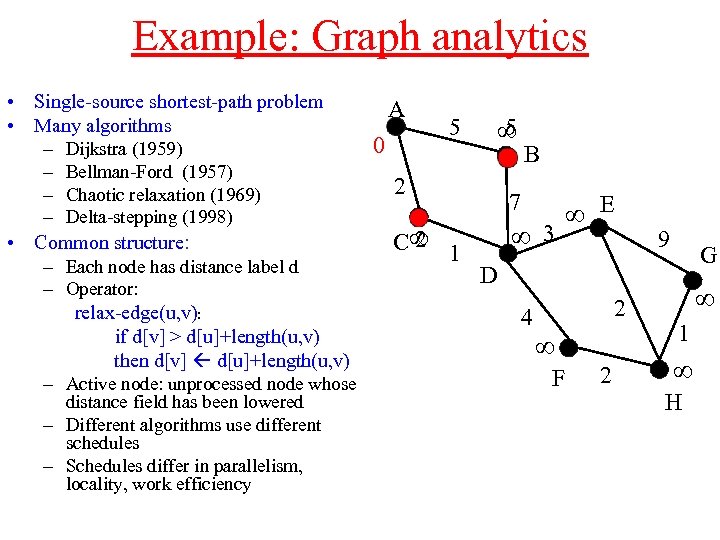

Example: Graph analytics • Single-source shortest-path problem A • Many algorithms 5 5 ∞ 0 – Dijkstra (1959) B – Bellman-Ford (1957) 2 – Chaotic relaxation (1969) 7 – Delta-stepping (1998) ∞ E ∞ 3 2 • Common structure: C∞ 1 – Each node has distance label d D – Operator: 2 relax-edge(u, v): 4 if d[v] > d[u]+length(u, v) ∞ then d[v] d[u]+length(u, v) F 2 – Active node: unprocessed node whose distance field has been lowered – Different algorithms use different schedules – Schedules differ in parallelism, locality, work efficiency 9 G ∞ 1 ∞ H

Example: Graph analytics • Single-source shortest-path problem A • Many algorithms 5 5 ∞ 0 – Dijkstra (1959) B – Bellman-Ford (1957) 2 – Chaotic relaxation (1969) 7 – Delta-stepping (1998) ∞ E ∞ 3 2 • Common structure: C∞ 1 – Each node has distance label d D – Operator: 2 relax-edge(u, v): 4 if d[v] > d[u]+length(u, v) ∞ then d[v] d[u]+length(u, v) F 2 – Active node: unprocessed node whose distance field has been lowered – Different algorithms use different schedules – Schedules differ in parallelism, locality, work efficiency 9 G ∞ 1 ∞ H

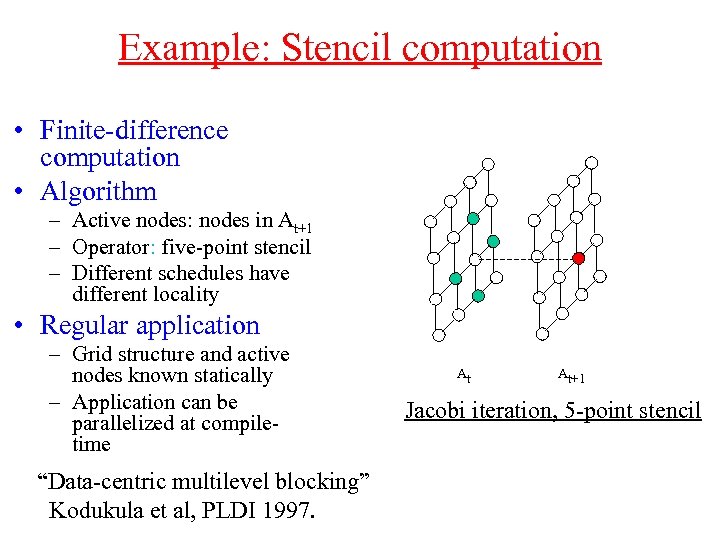

Example: Stencil computation • Finite-difference computation • Algorithm – Active nodes: nodes in At+1 – Operator: five-point stencil – Different schedules have different locality • Regular application – Grid structure and active nodes known statically – Application can be parallelized at compiletime “Data-centric multilevel blocking” Kodukula et al, PLDI 1997. At At+1 Jacobi iteration, 5 -point stencil

Example: Stencil computation • Finite-difference computation • Algorithm – Active nodes: nodes in At+1 – Operator: five-point stencil – Different schedules have different locality • Regular application – Grid structure and active nodes known statically – Application can be parallelized at compiletime “Data-centric multilevel blocking” Kodukula et al, PLDI 1997. At At+1 Jacobi iteration, 5 -point stencil

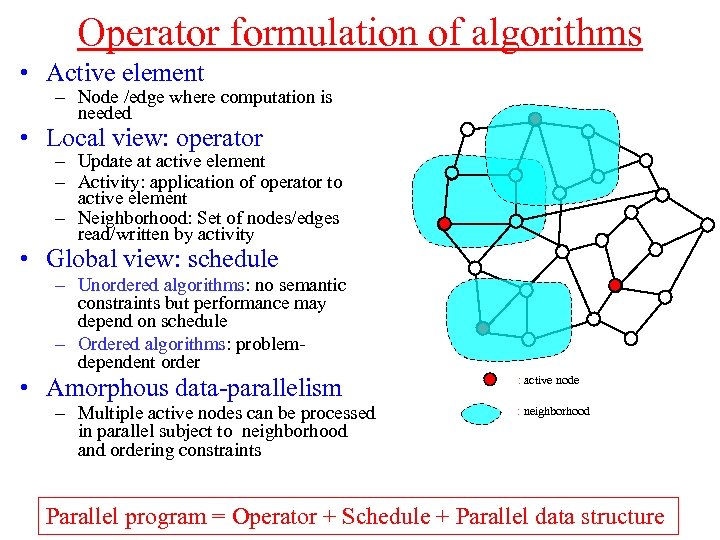

Operator formulation of algorithms • Active element – Node /edge where computation is needed • Local view: operator – Update at active element – Activity: application of operator to active element – Neighborhood: Set of nodes/edges read/written by activity • Global view: schedule – Unordered algorithms: no semantic constraints but performance may depend on schedule – Ordered algorithms: problemdependent order • Amorphous data-parallelism – Multiple active nodes can be processed in parallel subject to neighborhood and ordering constraints : active node : neighborhood Parallel program = Operator + Schedule + Parallel data structure

Operator formulation of algorithms • Active element – Node /edge where computation is needed • Local view: operator – Update at active element – Activity: application of operator to active element – Neighborhood: Set of nodes/edges read/written by activity • Global view: schedule – Unordered algorithms: no semantic constraints but performance may depend on schedule – Ordered algorithms: problemdependent order • Amorphous data-parallelism – Multiple active nodes can be processed in parallel subject to neighborhood and ordering constraints : active node : neighborhood Parallel program = Operator + Schedule + Parallel data structure

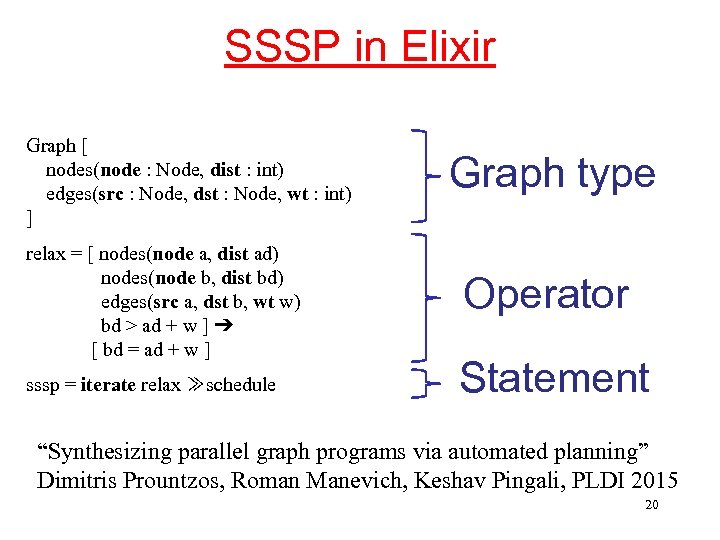

SSSP in Elixir Graph [ nodes(node : Node, dist : int) edges(src : Node, dst : Node, wt : int) ] relax = [ nodes(node a, dist ad) nodes(node b, dist bd) edges(src a, dst b, wt w) bd > ad + w ] ➔ [ bd = ad + w ] sssp = iterate relax ≫schedule Graph type Operator Statement “Synthesizing parallel graph programs via automated planning” Dimitris Prountzos, Roman Manevich, Keshav Pingali, PLDI 2015 20

SSSP in Elixir Graph [ nodes(node : Node, dist : int) edges(src : Node, dst : Node, wt : int) ] relax = [ nodes(node a, dist ad) nodes(node b, dist bd) edges(src a, dst b, wt w) bd > ad + w ] ➔ [ bd = ad + w ] sssp = iterate relax ≫schedule Graph type Operator Statement “Synthesizing parallel graph programs via automated planning” Dimitris Prountzos, Roman Manevich, Keshav Pingali, PLDI 2015 20

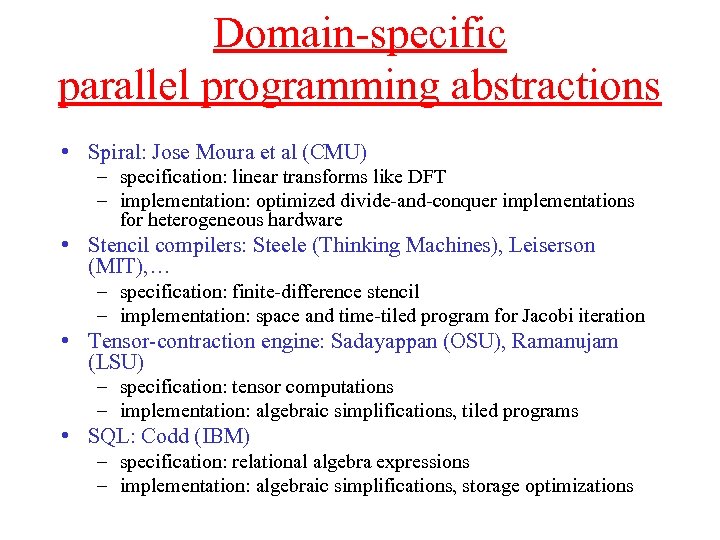

Domain-specific parallel programming abstractions • Spiral: Jose Moura et al (CMU) – specification: linear transforms like DFT – implementation: optimized divide-and-conquer implementations for heterogeneous hardware • Stencil compilers: Steele (Thinking Machines), Leiserson (MIT), … – specification: finite-difference stencil – implementation: space and time-tiled program for Jacobi iteration • Tensor-contraction engine: Sadayappan (OSU), Ramanujam (LSU) – specification: tensor computations – implementation: algebraic simplifications, tiled programs • SQL: Codd (IBM) – specification: relational algebra expressions – implementation: algebraic simplifications, storage optimizations

Domain-specific parallel programming abstractions • Spiral: Jose Moura et al (CMU) – specification: linear transforms like DFT – implementation: optimized divide-and-conquer implementations for heterogeneous hardware • Stencil compilers: Steele (Thinking Machines), Leiserson (MIT), … – specification: finite-difference stencil – implementation: space and time-tiled program for Jacobi iteration • Tensor-contraction engine: Sadayappan (OSU), Ramanujam (LSU) – specification: tensor computations – implementation: algebraic simplifications, tiled programs • SQL: Codd (IBM) – specification: relational algebra expressions – implementation: algebraic simplifications, storage optimizations

From productivity to performance

From productivity to performance

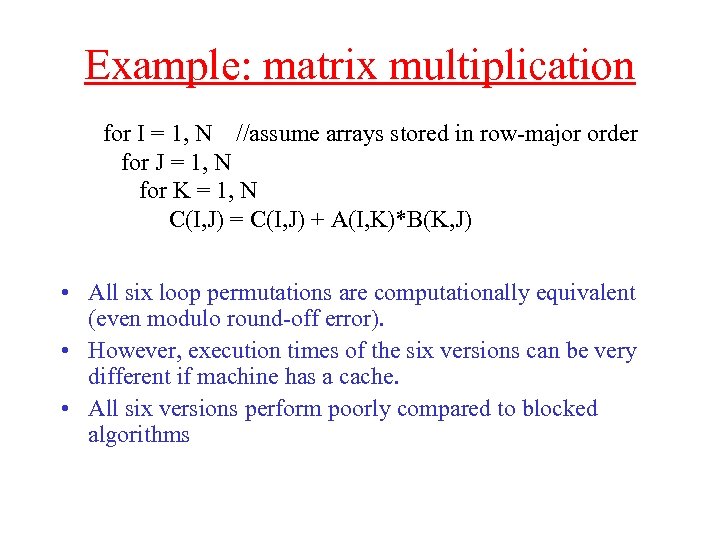

Example: matrix multiplication for I = 1, N //assume arrays stored in row-major order for J = 1, N for K = 1, N C(I, J) = C(I, J) + A(I, K)*B(K, J) • All six loop permutations are computationally equivalent (even modulo round-off error). • However, execution times of the six versions can be very different if machine has a cache. • All six versions perform poorly compared to blocked algorithms

Example: matrix multiplication for I = 1, N //assume arrays stored in row-major order for J = 1, N for K = 1, N C(I, J) = C(I, J) + A(I, K)*B(K, J) • All six loop permutations are computationally equivalent (even modulo round-off error). • However, execution times of the six versions can be very different if machine has a cache. • All six versions perform poorly compared to blocked algorithms

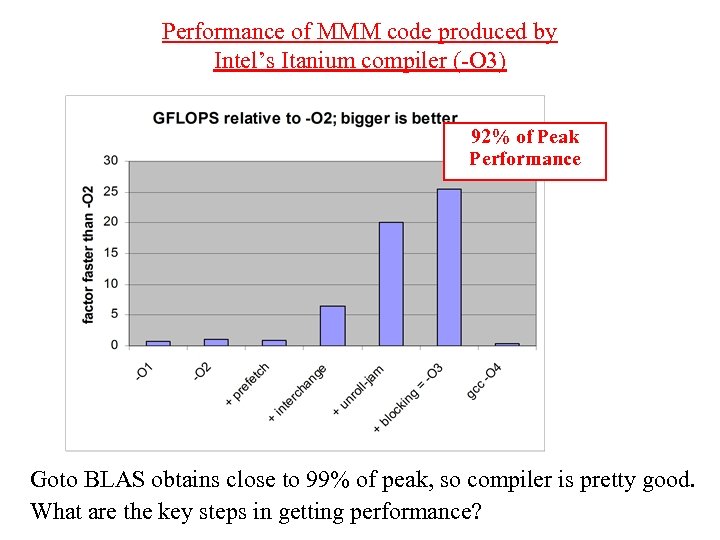

Performance of MMM code produced by Intel’s Itanium compiler (-O 3) 92% of Peak Performance Goto BLAS obtains close to 99% of peak, so compiler is pretty good. What are the key steps in getting performance?

Performance of MMM code produced by Intel’s Itanium compiler (-O 3) 92% of Peak Performance Goto BLAS obtains close to 99% of peak, so compiler is pretty good. What are the key steps in getting performance?

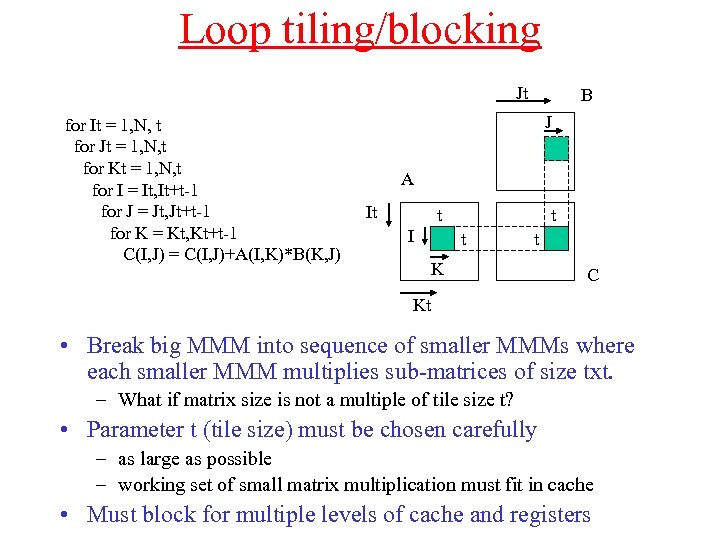

Loop tiling/blocking Jt for It = 1, N, t for Jt = 1, N, t for Kt = 1, N, t for I = It, It+t-1 for J = Jt, Jt+t-1 for K = Kt, Kt+t-1 C(I, J) = C(I, J)+A(I, K)*B(K, J) B J A It t I t t t K C Kt • Break big MMM into sequence of smaller MMMs where each smaller MMM multiplies sub-matrices of size txt. – What if matrix size is not a multiple of tile size t? • Parameter t (tile size) must be chosen carefully – as large as possible – working set of small matrix multiplication must fit in cache • Must block for multiple levels of cache and registers

Loop tiling/blocking Jt for It = 1, N, t for Jt = 1, N, t for Kt = 1, N, t for I = It, It+t-1 for J = Jt, Jt+t-1 for K = Kt, Kt+t-1 C(I, J) = C(I, J)+A(I, K)*B(K, J) B J A It t I t t t K C Kt • Break big MMM into sequence of smaller MMMs where each smaller MMM multiplies sub-matrices of size txt. – What if matrix size is not a multiple of tile size t? • Parameter t (tile size) must be chosen carefully – as large as possible – working set of small matrix multiplication must fit in cache • Must block for multiple levels of cache and registers

Choosing block/tile sizes • Two problems – Dependences may prevent some kinds of tiling – Optimal tile size depends on cache capacity and line size • Abstraction: constrained optimization problem – Constraint: tiling must not violate program dependences – Optimization: find best-performing one from among these

Choosing block/tile sizes • Two problems – Dependences may prevent some kinds of tiling – Optimal tile size depends on cache capacity and line size • Abstraction: constrained optimization problem – Constraint: tiling must not violate program dependences – Optimization: find best-performing one from among these

What we will study • Approaches to solving these kinds of constrained optimization problems – Auto-tuning: generate program variants and run on machine to find the best one • Useful for library generators – Modeling: build models of machine using analytical or machine learning techniques and use model to find best program variant • Both approaches require heuristic search over the space of program variants

What we will study • Approaches to solving these kinds of constrained optimization problems – Auto-tuning: generate program variants and run on machine to find the best one • Useful for library generators – Modeling: build models of machine using analytical or machine learning techniques and use model to find best program variant • Both approaches require heuristic search over the space of program variants

Deductive synthesis • Systems we have discussed so far perform deductive synthesis – Input is a complete specification of the computation – Knowledge base of domain properties and machine architecture in system – Use knowledge base to lower the level of program and optimize it • Difference from classical compilers – Classical compilers use some fixed sequence of transformations to generate code – Simple analytical models for performance – No notion of searching over program variants

Deductive synthesis • Systems we have discussed so far perform deductive synthesis – Input is a complete specification of the computation – Knowledge base of domain properties and machine architecture in system – Use knowledge base to lower the level of program and optimize it • Difference from classical compilers – Classical compilers use some fixed sequence of transformations to generate code – Simple analytical models for performance – No notion of searching over program variants

Inductive synthesis • Starting point is incomplete specification of what is to be computed • We will study several approaches – Programming by examples: Gulwani (MSR) and others – Sketching: Solar-Lezama (MIT), Bodik(UW) – English language specifications: Gulwani (MSR), Dillig (UT), …

Inductive synthesis • Starting point is incomplete specification of what is to be computed • We will study several approaches – Programming by examples: Gulwani (MSR) and others – Sketching: Solar-Lezama (MIT), Bodik(UW) – English language specifications: Gulwani (MSR), Dillig (UT), …

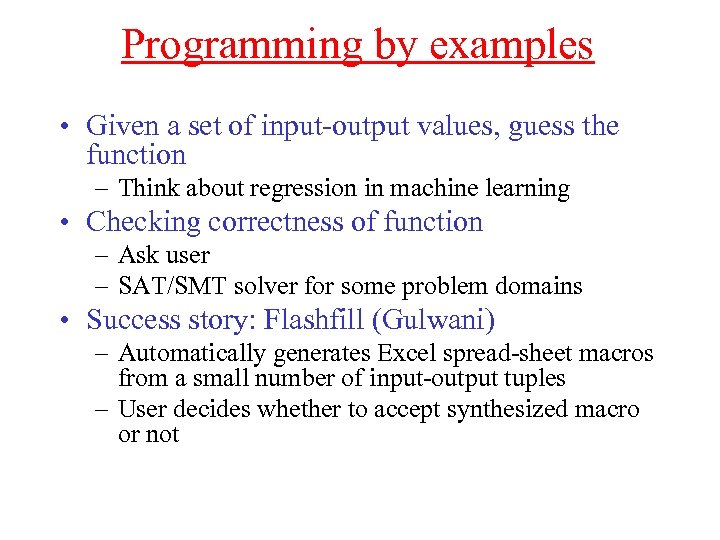

Programming by examples • Given a set of input-output values, guess the function – Think about regression in machine learning • Checking correctness of function – Ask user – SAT/SMT solver for some problem domains • Success story: Flashfill (Gulwani) – Automatically generates Excel spread-sheet macros from a small number of input-output tuples – User decides whether to accept synthesized macro or not

Programming by examples • Given a set of input-output values, guess the function – Think about regression in machine learning • Checking correctness of function – Ask user – SAT/SMT solver for some problem domains • Success story: Flashfill (Gulwani) – Automatically generates Excel spread-sheet macros from a small number of input-output tuples – User decides whether to accept synthesized macro or not

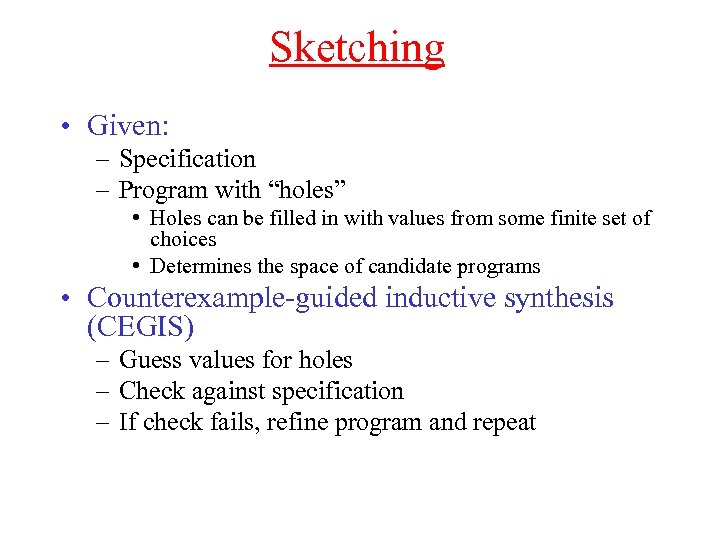

Sketching • Given: – Specification – Program with “holes” • Holes can be filled in with values from some finite set of choices • Determines the space of candidate programs • Counterexample-guided inductive synthesis (CEGIS) – Guess values for holes – Check against specification – If check fails, refine program and repeat

Sketching • Given: – Specification – Program with “holes” • Holes can be filled in with values from some finite set of choices • Determines the space of candidate programs • Counterexample-guided inductive synthesis (CEGIS) – Guess values for holes – Check against specification – If check fails, refine program and repeat

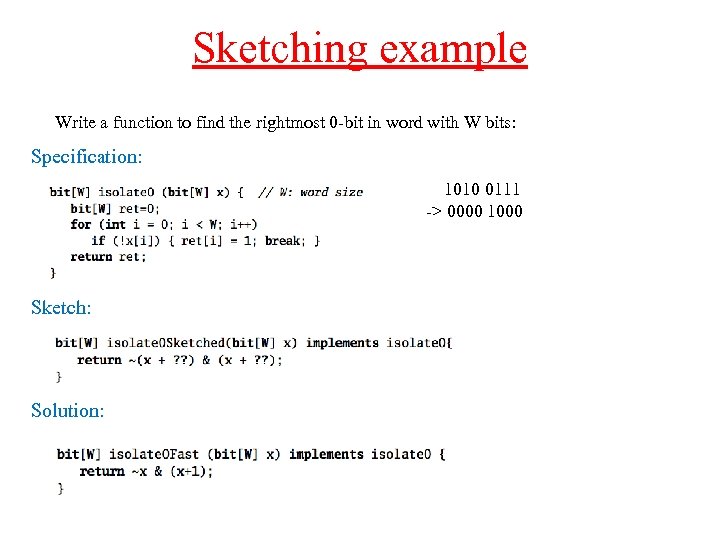

Sketching example Write a function to find the rightmost 0 -bit in word with W bits: Specification: 1010 0111 -> 0000 1000 Sketch: Solution:

Sketching example Write a function to find the rightmost 0 -bit in word with W bits: Specification: 1010 0111 -> 0000 1000 Sketch: Solution:

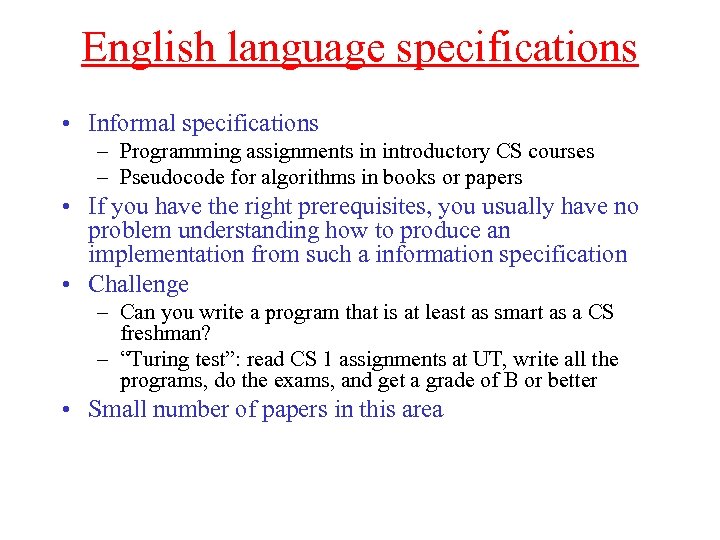

English language specifications • Informal specifications – Programming assignments in introductory CS courses – Pseudocode for algorithms in books or papers • If you have the right prerequisites, you usually have no problem understanding how to produce an implementation from such a information specification • Challenge – Can you write a program that is at least as smart as a CS freshman? – “Turing test”: read CS 1 assignments at UT, write all the programs, do the exams, and get a grade of B or better • Small number of papers in this area

English language specifications • Informal specifications – Programming assignments in introductory CS courses – Pseudocode for algorithms in books or papers • If you have the right prerequisites, you usually have no problem understanding how to produce an implementation from such a information specification • Challenge – Can you write a program that is at least as smart as a CS freshman? – “Turing test”: read CS 1 assignments at UT, write all the programs, do the exams, and get a grade of B or better • Small number of papers in this area

To-do items for you • Class website has papers and discussion order – Subject to change – I will assign presentation assignments in the next few days – Use the papers as a starting point for your study • If you find other papers that you would like us to read before your presentation, let Michael know and he will add links • Take a look at papers to get an idea of what we will talk about in course • If you are not yet registered for course, send mail to Michael so we know who you are

To-do items for you • Class website has papers and discussion order – Subject to change – I will assign presentation assignments in the next few days – Use the papers as a starting point for your study • If you find other papers that you would like us to read before your presentation, let Michael know and he will add links • Take a look at papers to get an idea of what we will talk about in course • If you are not yet registered for course, send mail to Michael so we know who you are