Crime in JAPAN.pptx

- Количество слайдов: 64

CRIME IN JAPAN

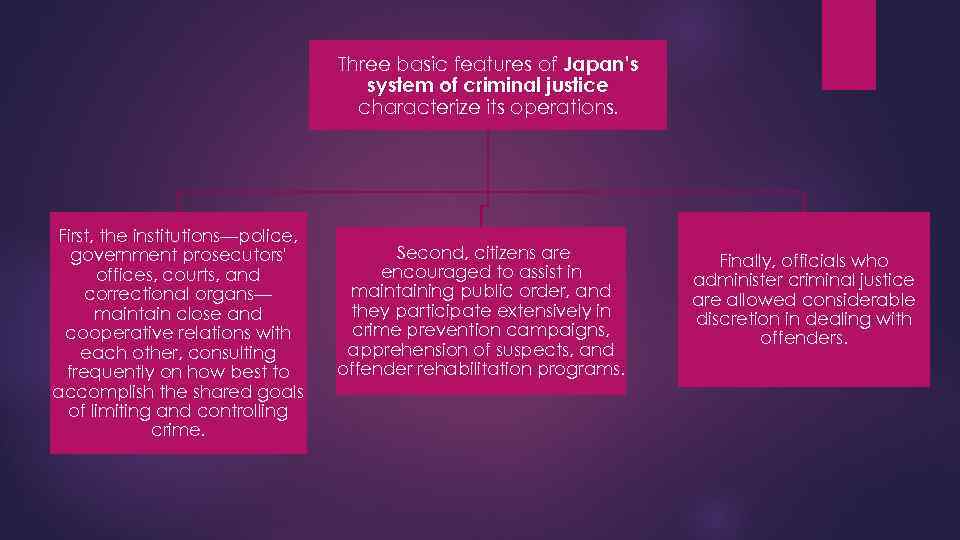

Three basic features of Japan’s system of criminal justice characterize its operations. First, the institutions—police, government prosecutors' offices, courts, and correctional organs— maintain close and cooperative relations with each other, consulting frequently on how best to accomplish the shared goals of limiting and controlling crime. Second, citizens are encouraged to assist in maintaining public order, and they participate extensively in crime prevention campaigns, apprehension of suspects, and offender rehabilitation programs. Finally, officials who administer criminal justice are allowed considerable discretion in dealing with offenders.

History

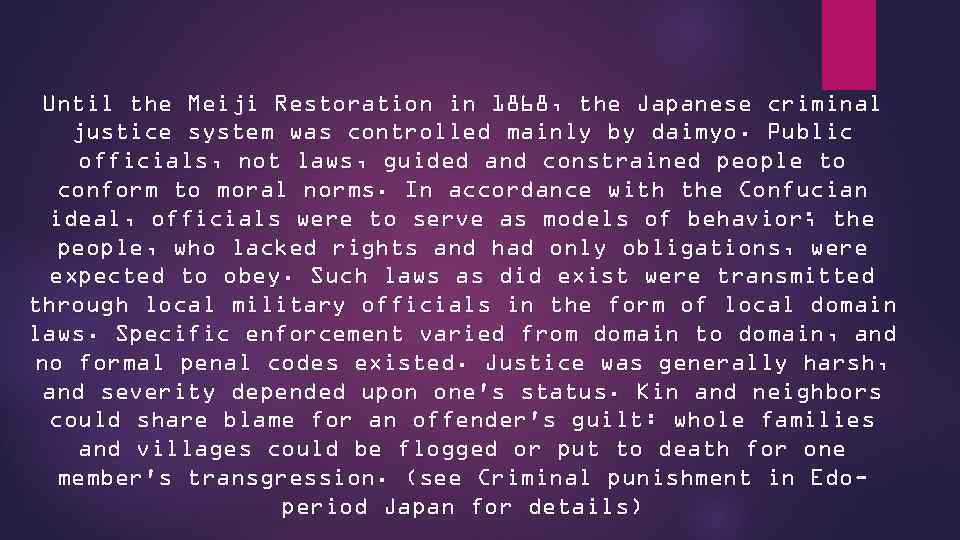

Until the Meiji Restoration in 1868, the Japanese criminal justice system was controlled mainly by daimyo. Public officials, not laws, guided and constrained people to conform to moral norms. In accordance with the Confucian ideal, officials were to serve as models of behavior; the people, who lacked rights and had only obligations, were expected to obey. Such laws as did exist were transmitted through local military officials in the form of local domain laws. Specific enforcement varied from domain to domain, and no formal penal codes existed. Justice was generally harsh, and severity depended upon one's status. Kin and neighbors could share blame for an offender's guilt: whole families and villages could be flogged or put to death for one member's transgression. (see Criminal punishment in Edoperiod Japan for details)

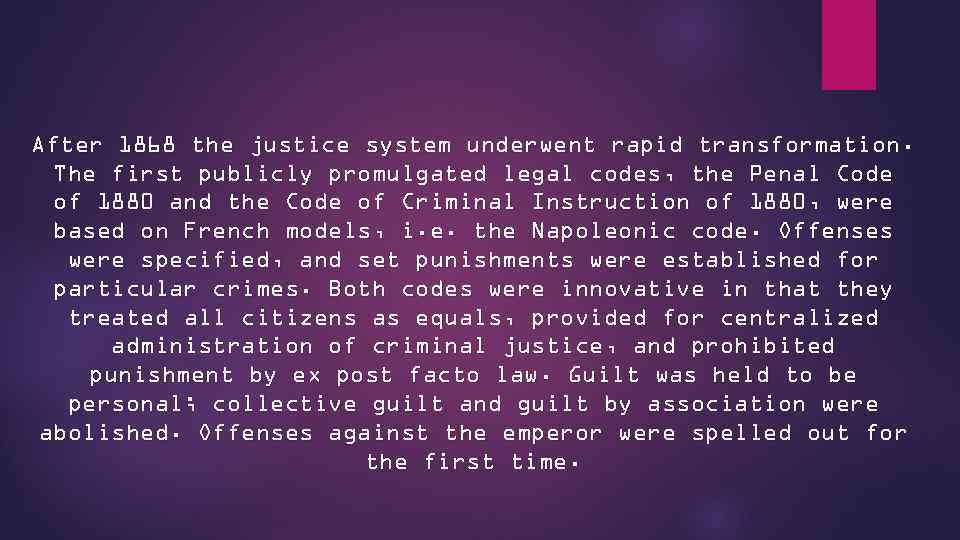

After 1868 the justice system underwent rapid transformation. The first publicly promulgated legal codes, the Penal Code of 1880 and the Code of Criminal Instruction of 1880, were based on French models, i. e. the Napoleonic code. Offenses were specified, and set punishments were established for particular crimes. Both codes were innovative in that they treated all citizens as equals, provided for centralized administration of criminal justice, and prohibited punishment by ex post facto law. Guilt was held to be personal; collective guilt and guilt by association were abolished. Offenses against the emperor were spelled out for the first time.

Innovative aspects of the codes notwithstanding, certain provisions reflected traditional attitudes toward authority. The prosecutor represented the state and sat with the judge on a raised platform—his position above the defendant and the defense counsel suggesting their relative status. Under a semi-inquisitorial system, primary responsibility for questioning witnesses lay with the judge, and defense counsel could question witnesses only through the judge. Cases were referred to trial only after a judge presided over a preliminary factfinding investigation in which the suspect was not permitted counsel. Because in all trials available evidence had already convinced the court in a preliminary procedure, the defendant's legal presumption of innocence at trial was undermined, and the legal recourse open to his counsel was further weakened.

The Penal Code was substantially revised in 1907 to reflect the growing influence of German law in Japan, and the French practice of classifying offenses into three types was eliminated. More important, where the old code had allowed very limited judicial discretion, the new one permitted the judge to apply a wide range of subjective factors in sentencing.

After World War II, occupation authorities initiated reform of the constitution and laws in general. Except for omitting offenses relating to war, the imperial family, and adultery, the 1947 Penal Code remained virtually identical to the 1907 version. The criminal procedure code, however, was substantially revised to incorporate rules guaranteeing the rights of the accused. The system became almost completely accusatorial, and the judge, although still able to question witnesses, decided a case on evidence presented by both sides. The preliminary investigative procedure was suppressed. The prosecutor and defense counsel sat on equal levels, below the judge. Laws on indemnification of the wrongly accused and laws concerning juveniles, prisons, probation, and minor offenses were also passed in the postwar years to supplement criminal justice administration.

Criminal procedure

The nation's criminal justice officials follow specified legal procedures in dealing with offenders. Once a suspect is arrested by national or prefectural police (See Prefectures of Japan), the case is turned over to attorneys in the Supreme Public Prosecutors Office, who are the government's sole agents in prosecuting lawbreakers. Under the Ministry of Justice's administration, these officials work under Supreme Court rules and are career civil servants who can be removed from office only for incompetence or impropriety. Prosecutors presented the government's case before judges in the Supreme Court and the four types of lower courts: high courts, district courts, summary courts, and family courts. Penal and probation officials administer programs for convicted offenders under the direction of public prosecutors (see Judicial System of Japan).

After identifying a suspect, police have the authority to exercise some discretion in determining the next step. If, in cases pertaining to theft, the amount is small or already returned, the offense petty, the victim unwilling to press charges, the act accidental, or the likelihood of a repetition not great, the police can either drop the case or turn it over to a prosecutor. Reflecting the belief that appropriate remedies are sometimes best found outside the formal criminal justice mechanisms, in 1990 over 70 percent of criminal cases were not sent to the prosecutor.

Juveniles Police also exercise wide discretion in matters concerning juveniles. Police are instructed by law to identify and counsel minors who appear likely to commit crimes, and they can refer juvenile offenders and non-offenders alike to child guidance centers to be treated on an outpatient basis. Police can also assign juveniles or those considered to be harming the welfare of juveniles to special family courts. These courts were established in 1949 in the belief that the adjustment of a family's situation is sometimes required to protect children and prevent juvenile delinquency. Family courts are run in closed sessions, try juvenile offenders under special laws, and operate extensive probationary guidance programs. The cases of young people between the ages of fourteen and twenty can, at the judgment of police, be sent to the public prosecutor for possible trial as adults before a judge under the general criminal law

Citizens

Arrest Police have to secure warrants to search for or seize evidence. A warrant is also necessary for an arrest, although if the crime is very serious or if the perpetrator is likely to flee, it can be obtained immediately after arrest. Within forty-eight hours after placing a suspect under detention, the police have to present their case before a prosecutor, who is then required to apprise the accused of the charges and of the right to counsel. Within another twenty-four hours, the prosecutor has to go before a judge and present a case to obtain a detention order. Suspects can be held for ten days (extensions are granted in almost all cases when requested)[citation needed], pending an investigation and a decision whether or not to prosecute. In the 1980 s, some suspects were reported to have been mistreated during this detention to exact a confession. These detentions often occur at cells within police stations, called daiyo kangoku.

Daiyo kangoku (daiyō kangoku 代用 監獄) is a Japanese legal term meaning "substitute prison. " Daiyō kangoku are detention cells found in police stations which are used as legal substitutes for detention centers, or prisons. The practical difference lies in the supervision of daiyō kangoku by the police forces responsible for investigations, whereas detention centers are supervised by a professional corps of prison guards who are not involved in the investigative processes.

Prosecution can be denied on the grounds of insufficient evidence or on the prosecutor's judgment. Under Article 248 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, after weighing the offender's age, character, and environment, the circumstances and gravity of the crime, and the accused's rehabilitative potential, public action does not have to be instituted, but can be denied or suspended and ultimately dropped after a probationary period. Because the investigation and disposition of a case can occur behind closed doors and the identity of an accused person who is not prosecuted is rarely made public, an offender can successfully reenter society and be rehabilitated under probationary status without the stigma of a criminal conviction.

Inquest of prosecution Institutional safeguards check the prosecutors' discretionary powers not to prosecute. Lay committees are established in conjunction with branch courts to hold inquests on a prosecutor's decisions. These committees meet four times yearly and can order that a case be reinvestigated and prosecuted. Victims or interested parties can also appeal a decision not to prosecute.

Trial Most offenses are tried first in district courts before one or three judges, depending on the severity of the case. Defendants are protected from self-incrimination, forced confession, and unrestricted admission of hearsay evidence. In addition, defendants have the right to counsel, public trial, and cross-examination. Trial by jury was authorized by the 1923 Jury Law but was suspended in 1943. A new lay judge law was enacted in 2004 and came into effect in May 2009, but it only applies to certain serious crimes.

The judge conducts the trial and is authorized to question witnesses, independently call for evidence, decide guilt, and pass sentence. The judge can also suspend any sentence or place a convicted party on probation. Should a judgment of not guilty be rendered, the accused is entitled to compensation by the state based on the number of days spent in detention.

Criminal cases from summary courts, family courts, and district courts can be appealed to the high courts by both the prosecution and the defense. Criminal appeal to the Supreme Court is limited to constitutional questions and a conflict of precedent between the Supreme Court and high courts.

The criminal code sets minimum and maximum sentences for offenses to allow for the varying circumstances of each crime and criminal. Penalties range from fines and short-term incarceration to compulsory labor and the death penalty. Heavier penalties are meted out to repeat offenders. Capital punishment consists of death by hanging and is usually imposed for multiple homicides.

After a sentence is finalized, the only recourse for a convict to gain an acquittal is through a retrial. A retrial can be granted if the convicted person or their legal representative show reasonable doubt about the finalized verdict, such as clear evidence that past testimony or expert opinions in the trial were false.

Yakuza

The yakuza had existed in Japan well before the 1800 s and followed codes similar to the bushido of the samurai. Their early operations were usually close-knit, and the leader and gang members had father-son relationships. Although this traditional arrangement continues to exist, yakuza activities are increasingly replaced by modern types of gangs that depend on force and money as organizing concepts. Nonetheless, yakuza often picture themselves as saviors of traditional Japanese virtues in a postwar society, sometimes forming ties with rightwing groups espousing the same views and attracting dissatisfied youths to their ranks.

Yakuza groups in 1990 were estimated to number more than 3, 300 and together contained more than 88, 000 members. Although concentrated in the largest urban prefectures, yakuza operate in most cities and often receive protection from highranking officials. After concerted police pressure in the 1960 s, smaller gangs either disappeared or began to consolidate in syndicate-type organizations. In 1990, three large syndicates (Yamaguchi-gumi, Sumiyoshi-kai, Inagawa-kai) dominated organized crime in the nation and controlled more than 1, 600 gangs and 42, 000 gangsters. Their number have since swelled and shrunk, often coinciding with economic conditions.

The yakuza tradition also spread to the Okinawa Island in the 20 th century. The Kyokuryu-kai and the Okinawa Kyokuryu-kai are the two largest known yakuza groups in Okinawa Prefecture and both have been registered as designated boryokudan groups under the Organized Crime Countermeasures Law since 1992.

Statistics In 1990 the police identified over 2. 2 million Penal Code violations. Two types of violations — larceny (65. 1 percent of total violation) and negligent homicide or injury as a result of accidents (26. 2%) — accounted for over 90 percent of criminal offenses. In 1989 Japan experienced 1. 3 robberies and 1. 1 murders per 100, 000 population. Japanese authorities also solve 75. 9% of robbery cases and 95. 9% of homicide cases.

In recent years, the number of crimes in Japan has decreased. In 2002, the number of crimes recorded was 2, 853, 739. This number halved by 2012 with 1, 382, 154 crimes being recorded. In 2013, the overall crime rate in Japan fell for the 11 th straight year and the number of murders and attempted murders also fell to a postwar low.

Legal deterrents Ownership of handguns is forbidden to the public, hunting rifles and ceremonial swords are registered with the police, and the manufacture and sale of firearms are regulated. The production and sale of live and blank ammunition are also controlled, as are the transportation and importation of all weapons. Crimes are seldom committed with firearms, yet knives remain a problem that the government is looking into, especially after the Akihabara massacre.

Crimes Of particular concern to the police are crimes associated with modernization. Increased wealth and technological sophistication has brought new white collar crimes, such as computer and credit card fraud, larceny involving coin dispensers, and insurance fraud. Incidence of drug abuse is minuscule, compared with other industrialized nations and limited mainly to stimulants. Japanese law enforcement authorities endeavor to control this problem by extensive coordination with international investigative organizations and stringent punishment of Japanese and foreign offenders. Traffic accidents and fatalities consume substantial law enforcement resources. There is also evidence of foreign criminals travelling from overseas to take advantage of Japan's lax security. In his autobiography Undesirables, British criminal Colin Blaney stated that English thieves have targeted the nation due to the low crime rate and because Japanese people are unprepared for crime. Pakistani, Russian, Sri Lankan and Burmese car theft gangs have also been known to target the nation.

List of major crimes in Japan

Date Name 1893 Location Summary 13 Kawachi Jūningiri Osaka Kumataro Kido and Yagoro Tani murdered ten people including an infant. The homicide was motivated by grudges against the victims. They committed suicide after the murders. 6? Kantō and Chūbu Serial killer Sataro Fukiage raped and murdered six girls. He also raped and murdered a girl in 1906. Exact victim estimates are unknown but one theory puts the number at 93 while another put it at more than 100. Fukiage was executed in 1926. 1923 - Sataro 1924 Fukiage Death

Date Name 1936 Sada Abe 1938 Tsuyama massacre Death Location Summary 1 Tokyo Sada Abe and Kichizo Ishida (her lover) engaged in Erotic asphyxiation resulting in his death. When he died she then cut off his penis and testicles and carried them around with her in a handbag. Because her way of killing him was erotic, her crime gave inspiration to Japanese films, such as Nagisa Oshima's In the Realm of the Senses. 31 rural hamlets near Tsuyama Okayama After cutting off electricity to his village, 21 -year-old Mutsuo Toi proceeded to go on a latenight killing spree with a hunting rifle, sword, and axe before killing himself.

Date Name Death Location Summary 1941 1942 Hamamatsu serial murders 9 -11 near Hamamats u, Shizuoka A deaf boy Seisaku Nakamura murders people in Shizuoka. He attempts to rape women and murder his family. He is arrested for nine murders in 1942. He admits two other murders. He is sentenced to death. 1944 1948 Kotobuki maternity hospital incident 103? Tokyo A hospital director Miyuki Ishikawa fatally neglects about a hundred babies. There accomplices and the Shinjuku ward office is suspected of giving approval for the murders.

Law enforcement in Japan

Law enforcement in Japan is provided by the Prefectural Police under the oversight of the National Police Agency or NPA. The NPA is headed by the National Public Safety Commission thus ensuring that Japan's police are an apolitical body and free of direct central government executive control. They are checked by an independent judiciary and monitored by a free and active press.

Japanese Police logo

National Police Agency Criminal Investigati on Bureau National organization Police Administration Bureau National Public Safety Commission

National Public Safety Commission The mission of the National Public Safety Commission is to guarantee the neutrality of the police by insulating the force from political pressure and to ensure the maintenance of democratic methods in police administration. The commission's primary function is to supervise the National Police Agency, and it has the authority to appoint or dismiss senior police officers. The commission consists of a chairman, who holds the rank of minister of state, and five members appointed by the prime minister with the consent of both houses of the Diet. The commission operates independently of the cabinet, but liaison and coordination with it are facilitated by the chairman's being a member of that body

National Police Agency As the central coordinating body for the entire police system, the National Police Agency determines general standards and policies; detailed direction of operations is left to the lower echelons. In a national emergency or largescale disaster, the agency is authorized to take command of prefectural police forces. In 1989 the agency was composed of about 1, 100 national civil servants, empowered to collect information and to formulate and execute national policies. The agency is headed by a commissioner general who is appointed by the National Public Safety Commission with the approval of the prime minister. The Central Office includes the Secretariat, with divisions for general operations, planning, information, finance, management, and procurement and distribution of police equipment, and five bureaus.

The National Police Agency (警察庁 Keisatsu-chō? ) is an agency administered by the National Public Safety Commission of the Cabinet Office in the cabinet of Japan, and is the central coordinating agency of the Japanese police system. Unlike comparable bodies like the U. S. Federal Bureau of Investigation, the NPA does not have any police officers of its own. Instead, its role is to determine general standards and policies, although in national emergencies or large-scale disasters the agency is authorized to take command of prefectural police forces. Policy for the NPA in turn is set by the National Public Safety Commission.

National Police Agency 警察庁 Keisatsu-chō Abbreviation NPA Logo of the National Police Agency.

Agency overview Formed 1954 Employees 7, 721 { 2013} Annual budget ¥ 258, 344 M (FY 2005/6) Legal personality Governmental: Government agency

Organiza

o Commissioner-General of the National Police Agency, the Highest ranking police officer (警察庁長官 Keisatsuchō Chōkan? ) o Deputy Commissioner-General (次長 Jichō? ) o Commissioner-General's Secretariat (長官官房 Chōkan Kanbō? ) o Community Safety Bureau (生活安全局 Seikatsu Anzenkyoku? ) o Criminal Investigation Bureau (刑事局 Keiji-kyoku? ) o Organized Crime Department (組織犯罪対策部 Soshiki Hanzai Taisaku-bu? )

o. Foreign Affairs and Intelligence Department (外事 情報部 Gaiji Jōhō-bu? ) o. Info-Communications Bureau (情報通信局 Jōhō Tsūshin-kyoku? ) o. National Police Academy (警察大学校 Keisatsu Dai -gakkō? ) o. National Research Institute of Police Science (科 学警察研究所 Kagaku Keisatsu Kenkyū-sho? ) o. Imperial Guard Headquarters (皇宮警察本部 Kōgū-

o Tohoku Regional Police Bureau (東北管区警察局 Tōhoku Kanku Keisatsu-kyoku? ) o Kanto Regional Police Bureau (関東管区警察局 Kantō Kanku Keisatsu-kyoku? ) o Chubu Regional Police Bureau (中部管区警察局 Chūbu Kanku Keisatsu-kyoku? ) o Kinki Regional Police Bureau (近畿管区警察局 Kinki Kanku Keisatsu-kyoku? ) o Chugoku Regional Police Bureau (中国管区警察局 Chūgoku Kanku Keisatsu-kyoku? ) o Shikoku Regional Police Bureau (四国管区警察局 Shikoku Kanku Keisatsu-kyoku? )

RANK

Commissioner General (Japanese: 警察庁長官 Keisatsu-chō Chōkan? ): The Chief of National Police Agency. The rank outside. 1 capacity. Assistant Police Inspector or Lieutenant (警部補 Keibuho? ): Squad Sub-Commander of Police Station, Leader of Riot Platoon. National Police Officer 1 st class's career start from this rank. Police Sergeant (巡査部長 Junsabuchō? ): Field supervisor, Leader of Police box. National Police Officer 2 nd class's career start from this rank. Superintendent General (警視総監 Keishi-sōkan? ): The Chief of Metropolitan Police Department. 1 capacity. Police Inspector or Captain (警部 Keibu? ): Squad Commander of Police Station, Leader of Riot Company. Senior Police Officer or Corporal ( 巡査長 Junsa-chō? ): Honorary rank of Police Officer Superintendent Supervisor (警視監 Keishi-kan? ): Deputy Commissioner General, Deputy Superintendent General, The Chief of Regional Police Bureau, The Chief of Prefectural Police Headquarters, others. 38 capacity Superintendent (警視 Keishi? ): The Chief of Police Station(small or middle), The Vice Commanding Officer of Police Station, Commander of Riot Unit. Police officer, old Patrolman (巡査 Junsa? ): Prefectural Police Officer's career start from this rank. Chief Superintendent (警視長 Keishi -chō? ): The Chief of Prefectural Police Headquarters. Senior Superintendent (警視正 Keishi-sei? ): The Chief of Police Station(large). More than this rank, all police officer join to National Police Agency.

The NPA Commissioner General holds the highest position of the Japanese police. His title is not a rank, but rather denotes his position as head of the NPA. On the other hand, the MPD Superintendent General represents not only the highest rank in the system but also assignment as head of the Tokyo Metropolitan Police Department.

Transportation

Ground In Japan, there about 40, 000 police vehicles nationwide with the average patrol cruisers being Toyota Crowns and Nissan Crews and similar large sedans, although small compact and micro cars are used by rural police boxes and in city centers where they are much more maneuverable. Pursuit vehicles depend on prefectures with the Honda NSX, Subaru Impreza, Subaru Legacy, Mitsubishi Lancer, Nissan Skyline, Mazda RX-7, and Nissan Fairlady Z are all used in various prefectures for highway patrols and pursuit uses. With the exception of unmarked traffic enforcement vehicles, all Japanese police forces are painted and marked in the same ways. Japanese police vehicles are painted black and white with the upper parts of the vehicle painted white. Motorcycles are usually all white and riot control and rescue vehicles are painted a steel blue.

Daihatsu Atrai Police Kei van Mitsubishi Diamante Police Car Daihatsu Mira Police Kei car Honda NSX Police Car

Aviation Helicopters are extensively used for traffic control surveillance, pursuit of suspects, rescue and disaster relief. Total of 80 small and medium-sized helicopters are being operated in 47 prefectures nationwide.

Tokyo Metropolitan Police Department, Agusta. Westland EH 101 Hokkaidō Police, Agusta A 109 E Osaka Police, Eurocopter AS 365 N 2 Hokkaidō Police, Bell 412 EP

Watercraft Japanese police boats are deployed to major ports, remote islands and lakes, where they are used for water patrol and control of illegal immigration, smuggling and poaching. Ranging from five to 23 meters long, there about 190 police boats nationwide.

Hokkaido Police Nagasaki Prefectural Police Hyōgo Police

Police Administration Bureau The Administration Bureau is concerned with police personnel, education, welfare, training, and unit inspections.

Criminal Investigation Bureau The Criminal Investigation Bureau is in charge of research statistics and the investigation of nationally important and international cases. This bureau's Safety Department is responsible for crime prevention, combating juvenile delinquency, and pollution control. In addition, the Criminal Investigation Bureau surveys, formulates, and recommends legislation on firearms, explosives, food, drugs, and narcotics. The Communications Bureau supervises police communications systems.

There also nine active field police squads 1 st division: Homicide or unregistered weapons. 2 nd division: Robbery. 3 rd division: Controlled substances or organized crime. 4 th division: Burglary, kidnapping or blackmail. 5 th division: Bombs or explosives. 6 th and 8 th division: Rapid reaction units. 7 th division: Financial crimes. 9 th division: Cybercrimes. Two task-force-grouped centers include: Forensic Science Center: Forensic Section (Criminalistics Office). Forensic Biology Office (Medical Examiner Office). Fingerprint Office High-Technology Crime Prevention Center. Electronic surveillance and monitoring center Information management office.

Traffic Bureau The Traffic Bureau licenses drivers, enforces traffic safety laws, and regulates traffic. Intensive traffic safety and driver education campaigns are run at both national and prefectural levels. The bureau's Expressway Division addresses special conditions of the nation's growing system of express highways.

Security Bureau The Security Bureau formulates and supervises the execution of security policies. It conducts research on equipment and tactics for suppressing riots and oversees and coordinates activities of the riot police. The Security Bureau is also responsible for security intelligence on foreigners and radical political groups, including investigation of violations of the Alien Registration Law and administration of the Entry and Exit Control Law. The bureau also implements security policies during national emergencies and natural disasters.

Police’s uniform in Japan

Crime in JAPAN.pptx