CORPUS LINGUISTICSCorpora When the first entirely corpus-based dictionary

CORPUS LINGUISTICS

Corpora When the first entirely corpus-based dictionary – COBUILD – came out in 1987, it was on the basis of a corpus of around 20 million words of connected text. Now all major British dictionary publishers use corpora of at least one hundred million words of text. Harrap/Chambers, Longman, and Oxford University Press have built the 100 million word British National Corpus (BNC). Harper-Collins has the 200 million-plus word Cobuild Bank of English (BoE). Cambridge University Press has compiled the 100 million word Cambridge Language Survey corpus (CLS).

The Development of Corpus Linguistics Modern computerized corpus linguistics began in an era when mainstream linguistics showed no interest in performance data at all. While in early sixties most linguists were engrossed in the theoretical (competence) abstractions of generative transformational grammar. Nelson Francis and Henry Kucera (both at Brown University) began compiling the first computer corpus of American English, the "Brown Corpus" a collection of about one million words in the form of 500 stretches of written text, approximately 2000 words each

The Development of Corpus Linguistics By the end of the 1960s, Randolph Quirk had set up a collection of transcribed spoken (British) English texts, the Survey of Modern English Educated Usage, which was later transformed into a computerized corpus—the "London-Lund Corpus”. The 1970s saw the compilation and computerization of the Lancaster-Oslo-Bergen (LOB) Corpus as the British English counterpart of the Brown Corpus.

The objectives of Corpus Linguistics Corpus Linguistics - the study of language on the basis of textual or acoustic corpora, always involving computer at some phase of storage, processing, and analysis of this data.

The objectives of Corpus Linguistics Textual corpora usually refer to the written aspect. Acoustic corpora refer to the research of spoken language with application to speech technology. Since the computer is involved, Corpus Linguistics is concerned not only with the analysis and interpretation of language, but also with computational techniques and methodology for the analysis of these texts.

The objectives of Corpus Linguistics The main task of Corpus Linguistics is the creation of machine-readable corpora and involving associative computational techniques as the basis for linguistic investigation.

The objectives of Corpus Linguistics CCL focuses its attention on: linguistic performance, rather than competence; quantitative, as well as qualitative models of language; linguistic description rather than linguistic universals; more empiricist, rather than a rationalist view of scientific investigation.

The methodology of CL The methodology of CL can be regarded like quantificational analysis of language that uses corpora as the basis from which the adequate language models may be built. The term language model’ is typically associated with notions like probabilistic part-of-speech taggers and parsers. A tagger assigns syntactic categories to lexical items. Thus, the output of such program can be used to annotate a word-list with part-of-speech labels. A parse tree would represent the subcategorization information.

BNC vs COBILD BNC – SARA (SGML Aware Retrieval Application) – the output: a sentence COBUILD (The Bank of English) – KWIC (Key-Word in Context) – the output: concordance)

Corpus databases Such view of language analysis and processing involves a methodology for the derivation of lexical information from corpus processing and storage of this information in a permanent lexical structure, i.e. a suitable lexical database. The main functions of corpus databases are: frequency based account of word-distribution patterns; concordance-driven definition of context and word behavior; extracting and representing word collocations; acquisition of lexical semantics of verbs from sentence frames; derivation of lexicons for machine translation.

Applications of corpus data Applications of corpus data include the five following areas: 1. Providing real-life material, for instance, for use as examples: Views vary on the use of examples straight from the corpus. 2. Helping lexicographers decide on sense distinctions to be made: Viewing different occurrences of the same word or lemma in the form of on-screen concordance lines (i.e., with a bit of the surrounding contexts and with the possibility of looking up the wider original contexts in the corpus)

Applications of corpus data 3. Providing information on grammatical patterns, subcategorization, registers, etc. The kinds of constructions in which an item typically occurs may help the lexicographer to describe its grammatical behavior, while the type of texts in which a word tends to occur may suggest specific characteristics in terms of register, style, (in)formality, etc. 4. Providing frequency information: the frequency of occurrence of a given item, differentiated with regard to senses, part-of-speech status, and even inflectional form may help lexicographers in deciding in what order to list senses, whether to list an inflected form as a separate entry (e.g., amusing as an adjective as well as the ing-form of amuse), etc.

Applications of corpus data 5. Providing information on new words, new combinations of words, and collocations: Totally new words are rare. Usually they are produced by standard word-formation processes such as derivation and compounding. The ways in which words tend to co-occur in more or less fixed combinations is increasingly felt to be highly important for a proper understanding of how they really function), and in recent years a great deal of effort has gone into attempts to develop software that can trace collocations adequately.

Corpus-based investigations of language use The Refinement of Language Statistics The use of large, balanced corpora has made it possible for the first time to include reasonably reliable frequency information about individual words in dictionaries. While the statistics for individual words are reasonably straightforward, those for combinations of words are less so. The notion of "mutual information" of a collocation (MI-score) as a measure of the likelihood of words occurring together, given their individual frequencies in the corpus, appears to be really important for the corpus analysis.

Corpus-based investigations of language use (Semi-)automatic data selection Adequate statistics are clearly very important for the question of (semi-) automatic data-selection. With the enormous expansion of corpus size in recent years, the sheer volume of data could become a hindrance. Working through hundreds or thousands of concordance lines for one and the same word or lemma may in fact blunt rather than sharpen the lexicographer's awareness.

Corpus-based investigations of language use Sense distinctions and sense-marking More ambitious approaches to overcoming the "information overflow" problem in large corpora are based on the assumption that the key to a word's meaning and function is the company it keeps – the kinds of words and structures that typically surround it. Such approaches therefore attempt to determine (semi-) automatically the different senses of a word and, on the basis of that analysis, present the lexicographer with a representative sample for each putative sense.

Corpus-based analysis It is based on empirical analysis of a large and principled collection of natural texts, known as a corpus; It makes extensive use of computers for analysis, using both automatic and interactive techniques; It depends on both quantitative and qualitative (interpretive) analytical techniques.

Corpus-based investigation of individual words A variety of corpus-based investigations are useful to Applied Linguists studying lexical issues. For example, corpus-based analyses have been used in the following three areas: to disambiguate the functions of multifunctional words; to investigate the distribution and use of closely related words; to identify and characterize the use of relatively fixed lexical expressions.

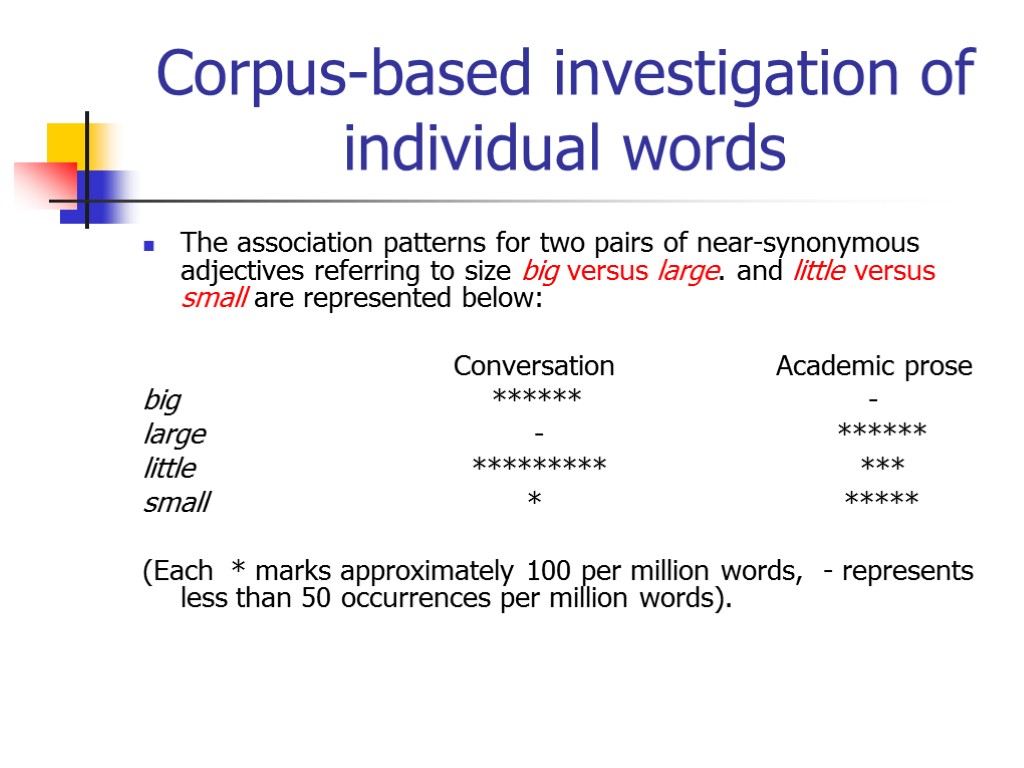

Corpus-based investigation of individual words The association patterns for two pairs of near-synonymous adjectives referring to size big versus large. and little versus small are represented below: Conversation Academic prose big ****** - large - ****** little ********* *** small * ***** (Each * marks approximately 100 per million words, - represents less than 50 occurrences per million words).

Corpus-based investigations of grammatical constructions Corpus-based analyses can also be used to investigate grammatical issues, addressing research questions such as the following: How is a grammatical construction used, and how are related constructions used differently? How rare or common are related constructions? Are constructions used more or less frequently in different registers? Are there particular words that a grammatical construction commonly co-occurs with? What factors in the discourse context are associated with the use of grammatical variants?

Corpus-based investigations of grammatical constructions To illustrate association patterns of this type, we briefly describe certain aspects of the grammar of complement clauses in English. The two most common types of complement clause are that-clauses and to-clauses. In some contexts, these two are similar in meaning. Thus compare: I hope that I can go. I hope to go.

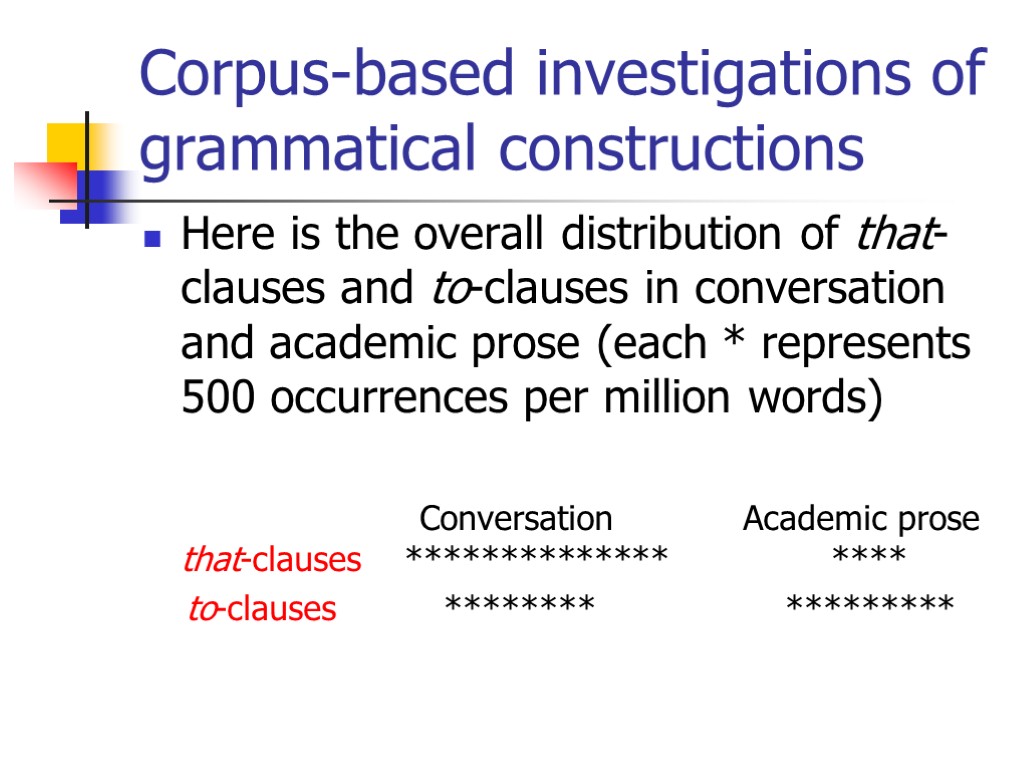

Corpus-based investigations of grammatical constructions Here is the overall distribution of that-clauses and to-clauses in conversation and academic prose (each * represents 500 occurrences per million words) Conversation Academic prose that-clauses ************** **** to-clauses ******** *********

Corpus-based investigations of grammatical constructions The difference in overall distribution noted above can be related in part to the differing lexical associations of the two types of complement clause. That is, while a few verbs can control both that-clauses and to-clauses (e.g., hope, decide, and wish), most verbs control only one or the other type of complement clause. For example, the verbs imagine, mention, suggest, conclude, guess and argue can control a that-clause but not a to-clause; the verbs begin, start, like, love, try and want can control a to-clause, but not a that-clause.

Corpus-based investigations of ESP and register variation Research on discourse and the linguistic characteristics of particular varieties of texts tends to be empirical, based on analysis of some collection of texts. In this regard, most discourse studies can be considered corpus-based. This trend in discourse analysis is seen both in ESP research in applied linguistics and in register variation research in sociolinguistics.

Corpus-based investigations of ESP and register variation A corpus-based approach enables comparative analyses of register variation. Using computational (semiautomatic techniques to analyze large text corpora, it is possible to investigate variation across a large number of registers with respect to a wide range of relevant linguistic characteristics. Such analyses provide an important foundation for work in ESP in that they characterize particular registers relative to the range of other registers, documenting the extent of linguistic differences across registers.

Corpus-based investigations of ESP and register variation This approach may be illustrated using D.Biber's multi-dimensional (MD) analytical approach (1994). Research in this framework analyzes the distribution of linguistic features in a computer corpus to identify text-based association patterns – sets of linguistic features that tend to co-occur in texts. Each grouping of linguistic features is referred to as a 'dimension.'

linguistic_corpora_and_lexicography.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 27