50a74e3fe020170af5b6a93c7996df0a.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 56

Cor Pulmonale Faculty of Medicine Universitas Brawijaya Malang

Cor Pulmonale • Right Sided Heart Disease, secondarily caused by abnormalities of lung parenchyme, airways, thorax, or respiratory control mechanisms. • Noevidence of other heart conditions, • Acute vs. Chronic

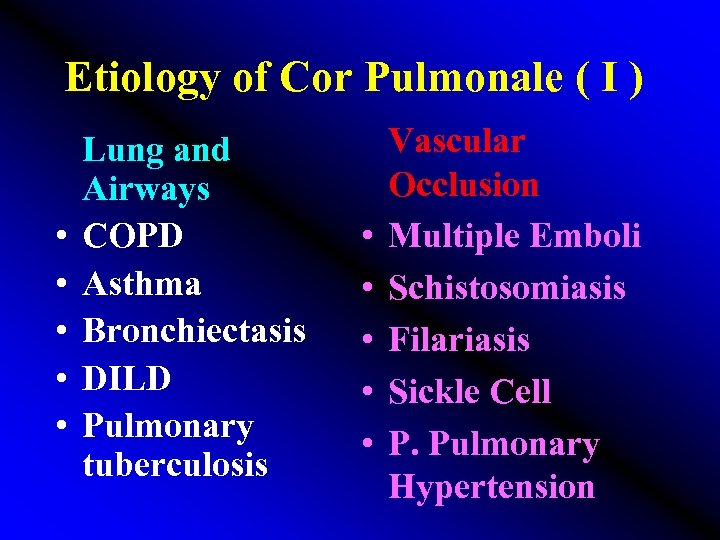

Etiology of Cor Pulmonale ( I ) • • • Lung and Airways COPD Asthma Bronchiectasis DILD Pulmonary tuberculosis • • • Vascular Occlusion Multiple Emboli Schistosomiasis Filariasis Sickle Cell P. Pulmonary Hypertension

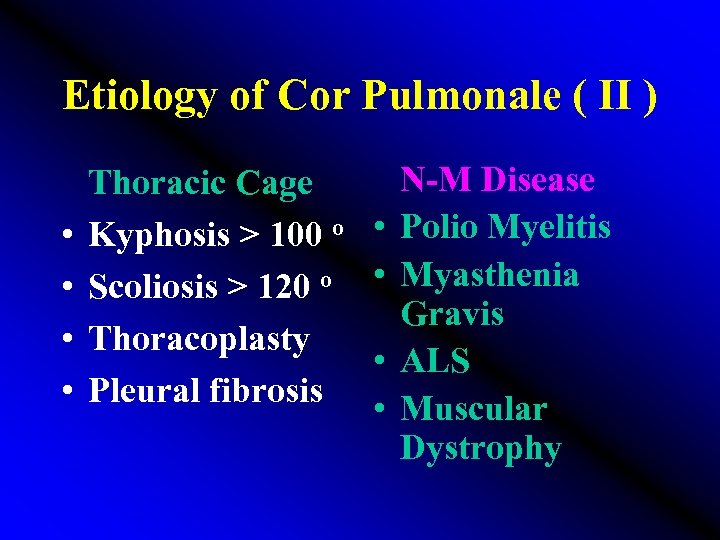

Etiology of Cor Pulmonale ( II ) • • N-M Disease Thoracic Cage Kyphosis > 100 o • Polio Myelitis Scoliosis > 120 o • Myasthenia Gravis Thoracoplasty • ALS Pleural fibrosis • Muscular Dystrophy

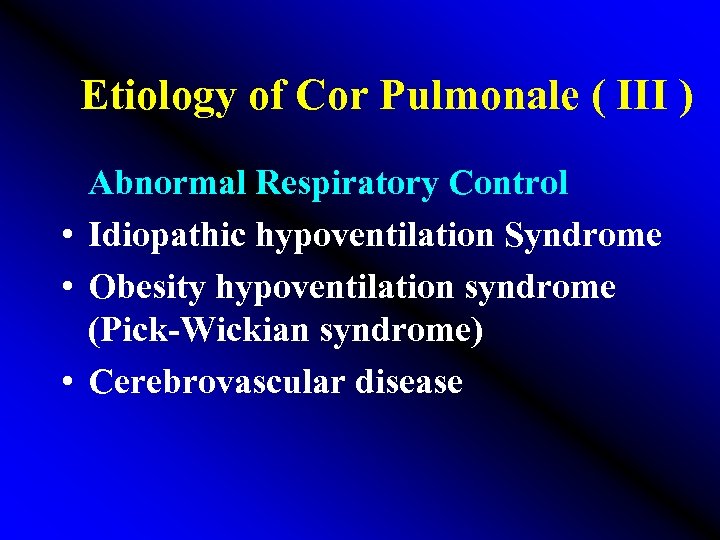

Etiology of Cor Pulmonale ( III ) Abnormal Respiratory Control • Idiopathic hypoventilation Syndrome • Obesity hypoventilation syndrome (Pick-Wickian syndrome) • Cerebrovascular disease

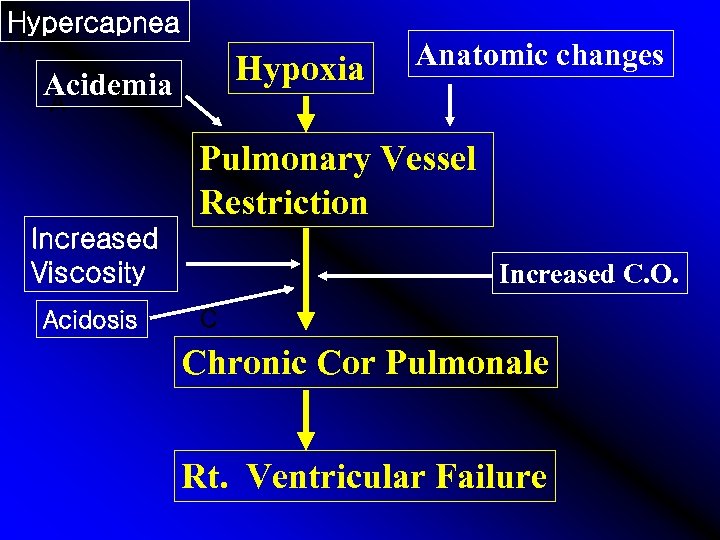

Hypercapnea H Hypoxia Acidemia Anatomic changes A Pulmonary Vessel Restriction Increased Viscosity Acidosis Increased C. O. C Chronic Cor Pulmonale Rt. Ventricular Failure

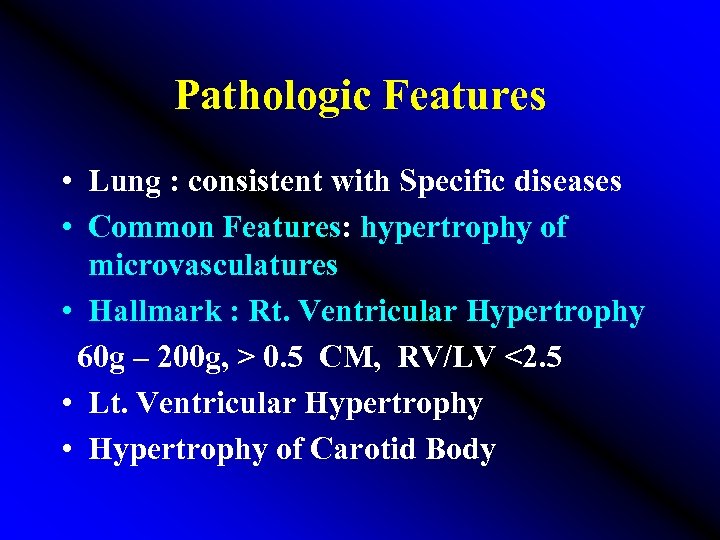

Pathologic Features • Lung : consistent with Specific diseases • Common Features: hypertrophy of microvasculatures • Hallmark : Rt. Ventricular Hypertrophy 60 g – 200 g, > 0. 5 CM, RV/LV <2. 5 • Lt. Ventricular Hypertrophy • Hypertrophy of Carotid Body

Natural History • Several months to years to develop • All ages from child to old people • Repeated infections aggravate RV strain into RV failure • Initilly respondes well to therapy but progressively becomes refractory

Prevalence • • Emphysema : less frequent Cronic bronchitis : more common US : 6 -7 % of Heart failure Delhi : 16% Sheffield in UK : 30 – 40% Autopsy in Chronic Bronchitis : 50% More prevalent in pollution area or smokers

Lab. Findings • X-Ray : Prominent pulmonary hilum pulmonary artery dilatation Rt MPA > 20 mm • EKG : P- pulmonale, RAD, RVH • Echocardiography : RVH, TR, Pulm. Hypertension • ABG : Hypoxemia, Hypercapnea, Respiratory acidosis • CBC : polycythemia • Cardiac catheterization

Treatment • Treat Underlying Disease : COPD Tx, Steroid, Infection control, theophylline, medroxyprogesterone, • Continuous O 2 : < 2 -3 L/min • Diuretics • Phlebotomy • Digoxin : controversial • Pul. Vasodilators • Beta adrenergic agents • Reduce Ventilation/Perfusion imbalance : Amitrine bimesylate

Prognosis • 1960 -1970 : 3 yr mortality 50 -60% • Recent times : 5 - 10 years or more

Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension (PAH) 13

PAH explained 14

What is PAH? • Progressive disease caused by narrowing or tightening of the pulmonary arteries • Right side of the heart becomes enlarged due to the increased strain of pumping blood through the lungs • Strain leads to the common symptoms of PAH (breathlessness, fatigue, weakness, angina and syncope)1 • PAH is characterised by; 1, 2 – mean PAP ≥ 25 mm. Hg at rest – mean PCWP ≤ 15 mm. Hg 15 1. Galiè N et al. Eur Heart J 2009; 2. Badesch DB et al. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009

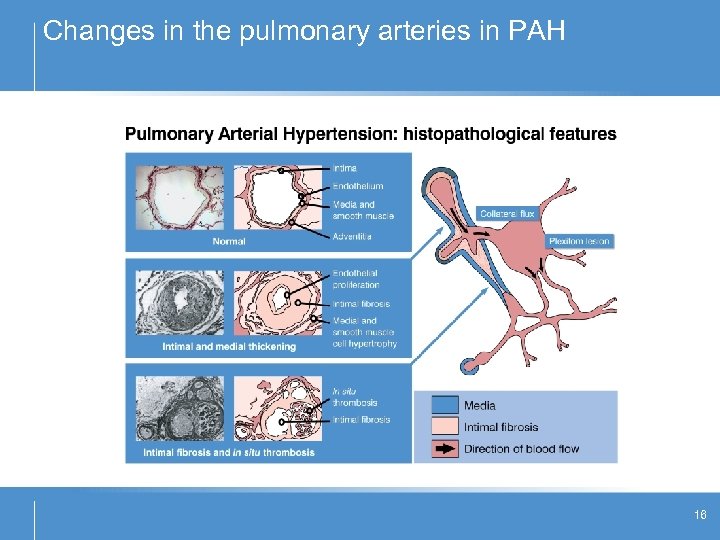

Changes in the pulmonary arteries in PAH 16

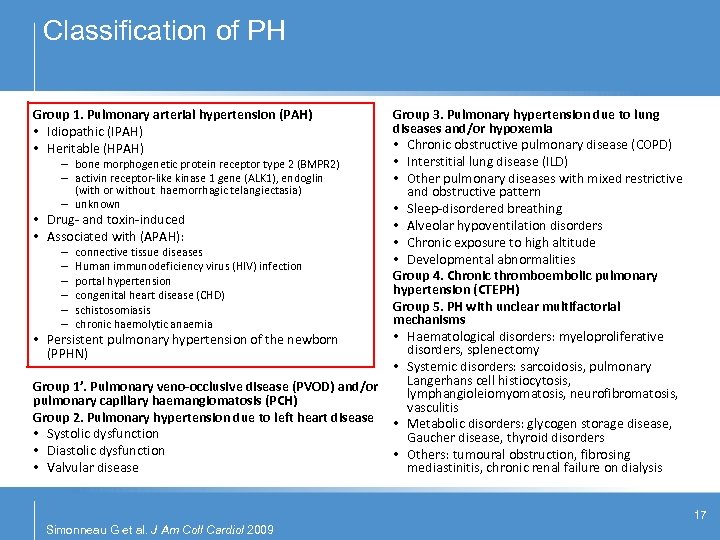

Classification of PH Group 1. Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) • Idiopathic (IPAH) • Heritable (HPAH) – bone morphogenetic protein receptor type 2 (BMPR 2) – activin receptor-like kinase 1 gene (ALK 1), endoglin (with or without haemorrhagic telangiectasia) – unknown • Drug- and toxin-induced • Associated with (APAH): – – – connective tissue diseases Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection portal hypertension congenital heart disease (CHD) schistosomiasis chronic haemolytic anaemia • Persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn (PPHN) Group 1’. Pulmonary veno-occlusive disease (PVOD) and/or pulmonary capillary haemangiomatosis (PCH) Group 2. Pulmonary hypertension due to left heart disease • Systolic dysfunction • Diastolic dysfunction • Valvular disease Group 3. Pulmonary hypertension due to lung diseases and/or hypoxemia • Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) • Interstitial lung disease (ILD) • Other pulmonary diseases with mixed restrictive and obstructive pattern • Sleep-disordered breathing • Alveolar hypoventilation disorders • Chronic exposure to high altitude • Developmental abnormalities Group 4. Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH) Group 5. PH with unclear multifactorial mechanisms • Haematological disorders: myeloproliferative disorders, splenectomy • Systemic disorders: sarcoidosis, pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis, lymphangioleiomyomatosis, neurofibromatosis, vasculitis • Metabolic disorders: glycogen storage disease, Gaucher disease, thyroid disorders • Others: tumoural obstruction, fibrosing mediastinitis, chronic renal failure on dialysis 17 Simonneau G et al. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009

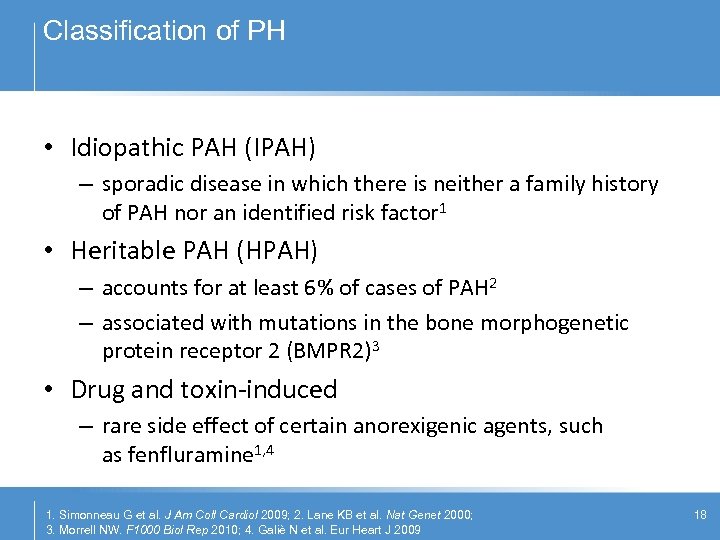

Classification of PH • Idiopathic PAH (IPAH) – sporadic disease in which there is neither a family history of PAH nor an identified risk factor 1 • Heritable PAH (HPAH) – accounts for at least 6% of cases of PAH 2 – associated with mutations in the bone morphogenetic protein receptor 2 (BMPR 2)3 • Drug and toxin-induced – rare side effect of certain anorexigenic agents, such as fenfluramine 1, 4 1. Simonneau G et al. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009; 2. Lane KB et al. Nat Genet 2000; 3. Morrell NW. F 1000 Biol Rep 2010; 4. Galiè N et al. Eur Heart J 2009 18

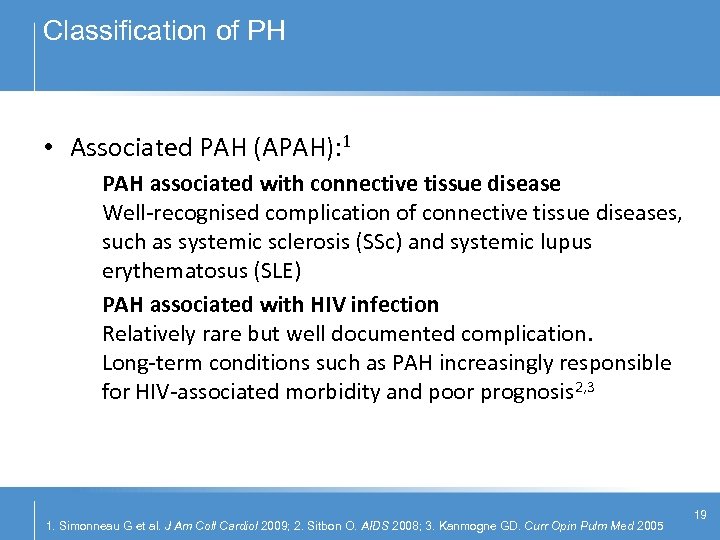

Classification of PH • Associated PAH (APAH): 1 PAH associated with connective tissue disease Well-recognised complication of connective tissue diseases, such as systemic sclerosis (SSc) and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) PAH associated with HIV infection Relatively rare but well documented complication. Long-term conditions such as PAH increasingly responsible for HIV-associated morbidity and poor prognosis 2, 3 1. Simonneau G et al. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009; 2. Sitbon O. AIDS 2008; 3. Kanmogne GD. Curr Opin Pulm Med 2005 19

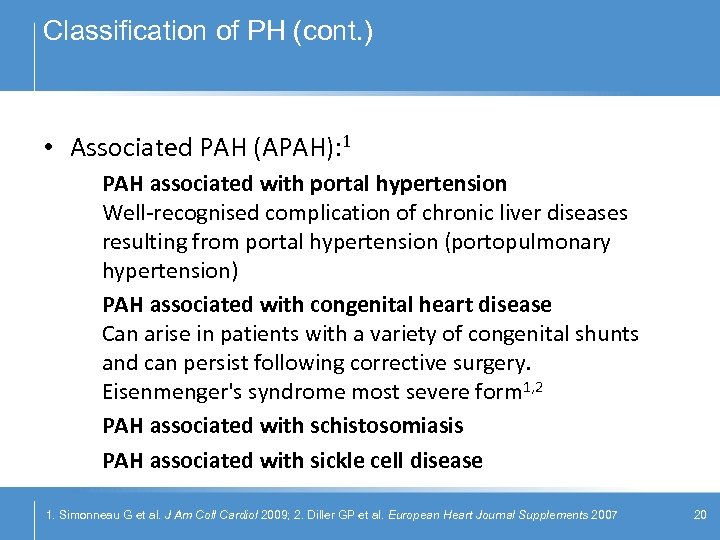

Classification of PH (cont. ) • Associated PAH (APAH): 1 PAH associated with portal hypertension Well-recognised complication of chronic liver diseases resulting from portal hypertension (portopulmonary hypertension) PAH associated with congenital heart disease Can arise in patients with a variety of congenital shunts and can persist following corrective surgery. Eisenmenger's syndrome most severe form 1, 2 PAH associated with schistosomiasis PAH associated with sickle cell disease 1. Simonneau G et al. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009; 2. Diller GP et al. European Heart Journal Supplements 2007 20

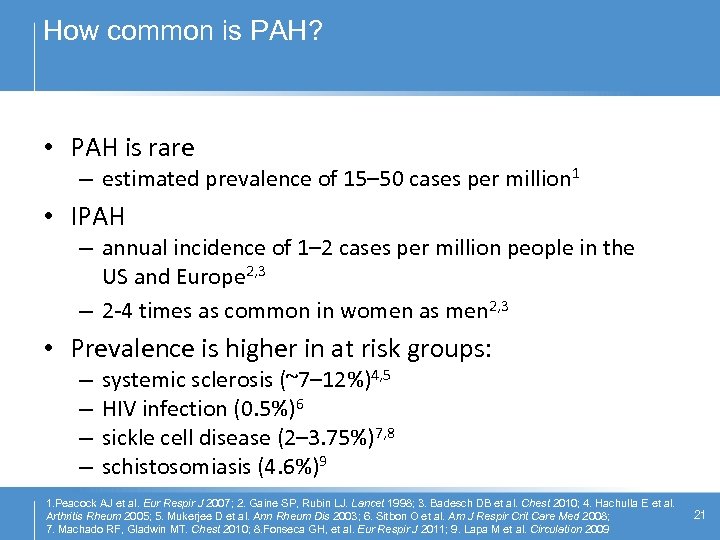

How common is PAH? • PAH is rare – estimated prevalence of 15– 50 cases per million 1 • IPAH – annual incidence of 1– 2 cases per million people in the US and Europe 2, 3 – 2 -4 times as common in women as men 2, 3 • Prevalence is higher in at risk groups: – – systemic sclerosis (~7– 12%)4, 5 HIV infection (0. 5%)6 sickle cell disease (2– 3. 75%)7, 8 schistosomiasis (4. 6%)9 1. Peacock AJ et al. Eur Respir J 2007; 2. Gaine SP, Rubin LJ. Lancet 1998; 3. Badesch DB et al. Chest 2010; 4. Hachulla E et al. Arthritis Rheum 2005; 5. Mukerjee D et al. Ann Rheum Dis 2003; 6. Sitbon O et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008; 7. Machado RF, Gladwin MT. Chest 2010; 8. Fonseca GH, et al. Eur Respir J 2011; 9. Lapa M et al. Circulation 2009 21

Why does PAH develop? • Exact causes unknown • Complex, multi-factorial condition 1, 2 • Endothelial dysfunction occurs early in disease pathogenesis and leads to 1: – – endothelial and smooth muscle proliferation remodelling of the vessel wall impaired production of vasodilators (NO, prostacyclin) overexpression of vasoconstrictors (endothelin-1) 1. Galiè N, Hoeper M, Humbert M, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension. Eur Heart J 2009; 30: 2493 – 537. 22 2. Mc. Laughlin VV, Archer SL, Badesch DB, et al. ACCF/AHA 2009 expert consensus document on pulmonary hypertension: 2009; 119: 2250– 94.

The role of endothelin • Endothelin-1 (ET-1) – elevated levels are seen in PAH patients 1 3 – levels correlate with disease severity 4 – deleterious effects mediated through ETA and ETB receptors 5 – fibrosis – hypertrophy and cell proliferation – inflammation – vasoconstriction – endothelin receptor antagonists can block these effects 6 1. Stewart DJ et al. Ann Inter Med 1991; 2. Vancheeswaran R et al. J Rheum 1994; 3. Yoshibayashi M et al. Circulation 1991; 4. Galiè N et al. Eur J Clin Invest 1996; 5. Humbert M et al. N Engl J Med 2004; 6. Channick RN et al. Lancet 2001 23

The role of prostacyclin • Prostacyclin 1, 2 – – potent vasodilator inhibitor of platelet activation low levels in patients with PAH therapy with prostacyclin or prostacyclin analogues can help to correct this deficiency 24 1. Humbert M et al. N Engl J Med 2004; 2. Mc. Goon MD, Kane GC. Mayo Clin Proc 2009; 84: 191– 207

The role of nitric oxide • Nitric oxide 1, 2 – – – potent vasodilator possesses anti-proliferative properties impaired production in PAH 3 vasodilatory effect is mediated by c. GMP rapidly degraded by phosphodiesterases (PDEs) therapy with oral PDE-5 inhibitors reduces degradation 4 1. Galiè N et al. Prog Cardiov Dis 2003; 2. Humbert M et al. N Engl J Med 2004; 3. Mc. Laughlin VV et al. Circulation 2009; 4. Galiè N et al. N Engl J Med 2005 25

What are the symptoms of PAH? • High resistance to blood flow through the lungs causes right heart dysfunction, decreased cardiac output and produces: 1– 3 – – – dyspnoea fatigue dizziness syncope peripheral oedema chest pain, particularly during physical exercise 1. Galiè N et al. Eur Heart J 2009; 2. Gaine SP et al. Lancet 1998; 3. Barst RJ et al. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004 26

What are the symptoms of PAH? • Early symptoms mild and non-specific • Commonly attributed to other conditions • Over time, symptoms become more severe and limit normal daily activities • Delayed diagnosis common: – symptom onset to disease diagnosis > 2 years 1, 2, 3 – frequently not recognised until the disease is relatively advanced 1, 3 1. Humbert M et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006; 2. Badesch DB et al. Chest 2010; 3. Gaine SP, Rubin LJ. Lancet 1998 27

Diagnosing PAH 28

How is PAH diagnosed? • PAH is a challenging disease to diagnose accurately; diagnosis cannot be made on symptoms alone • Series of investigations to: 1, 2 – determine whethere is a likelihood of PAH being present – confirm the diagnosis based on initial non-invasive testing – clarify the specific aetiology – evaluate the functional and haemodynamic impairment of the individual patient – determine an appropriate treatment category 29 1. Galiè N et al. Eur Heart J 2009; 2. Mc. Laughlin VV et al. Circulation 2009

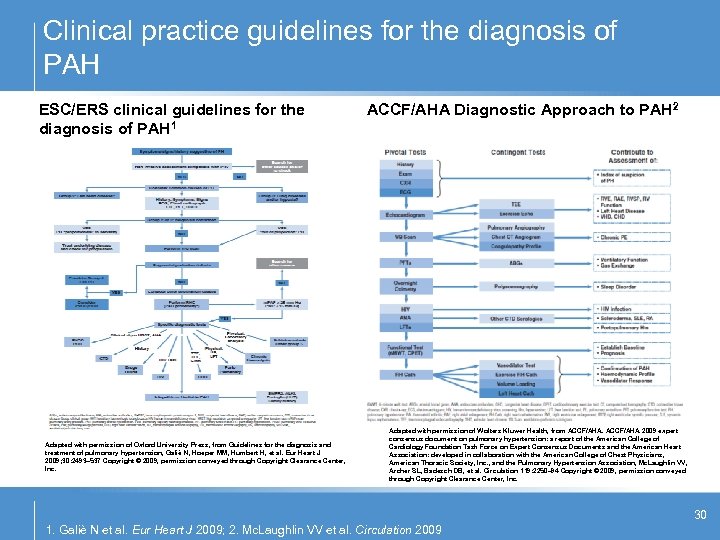

Clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis of PAH ESC/ERS clinical guidelines for the diagnosis of PAH 1 Adapted with permission of Oxford University Press, from Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension, Galiè N, Hoeper MM, Humbert H, et al. Eur Heart J 2009; 30: 2493– 537 Copyright © 2009, permission conveyed through Copyright Clearance Center, Inc. ACCF/AHA Diagnostic Approach to PAH 2 Adapted with permission of Wolters Kluwer Health, from ACCF/AHA 2009 expert consensus document on pulmonary hypertension: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Expert Consensus Documents and the American Heart Association: developed in collaboration with the American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, Inc. , and the Pulmonary Hypertension Association, Mc. Laughlin VV, Archer SL, Badesch DB, et al. Circulation 119: 2250– 94 Copyright © 2009, permission conveyed through Copyright Clearance Center, Inc. 30 1. Galiè N et al. Eur Heart J 2009; 2. Mc. Laughlin VV et al. Circulation 2009

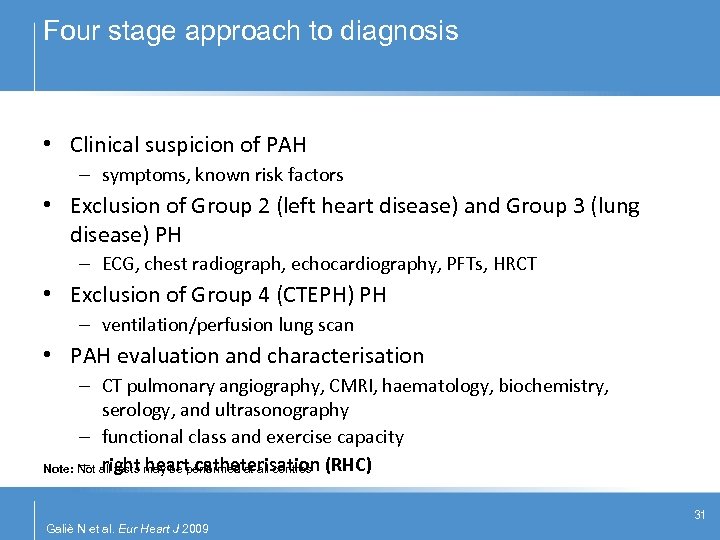

Four stage approach to diagnosis • Clinical suspicion of PAH – symptoms, known risk factors • Exclusion of Group 2 (left heart disease) and Group 3 (lung disease) PH – ECG, chest radiograph, echocardiography, PFTs, HRCT • Exclusion of Group 4 (CTEPH) PH – ventilation/perfusion lung scan • PAH evaluation and characterisation – CT pulmonary angiography, CMRI, haematology, biochemistry, serology, and ultrasonography – functional class and exercise capacity – right heart catheterisation Note: Not all tests may be performed at all centres (RHC) 31 Galiè N et al. Eur Heart J 2009

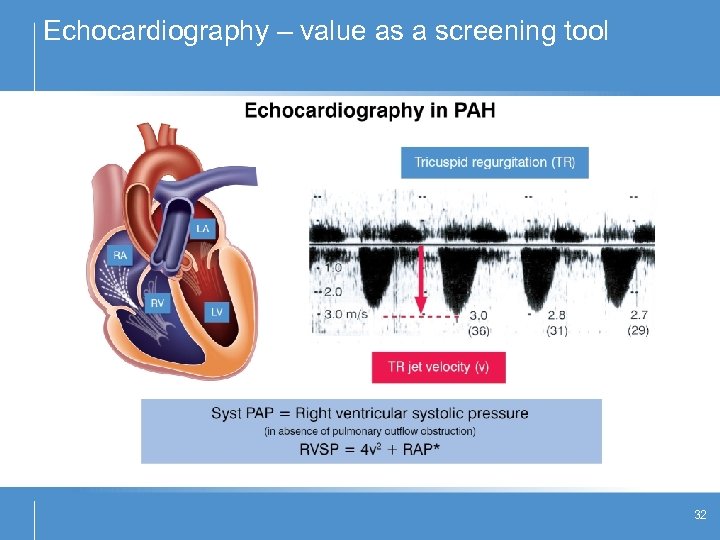

Echocardiography – value as a screening tool 32

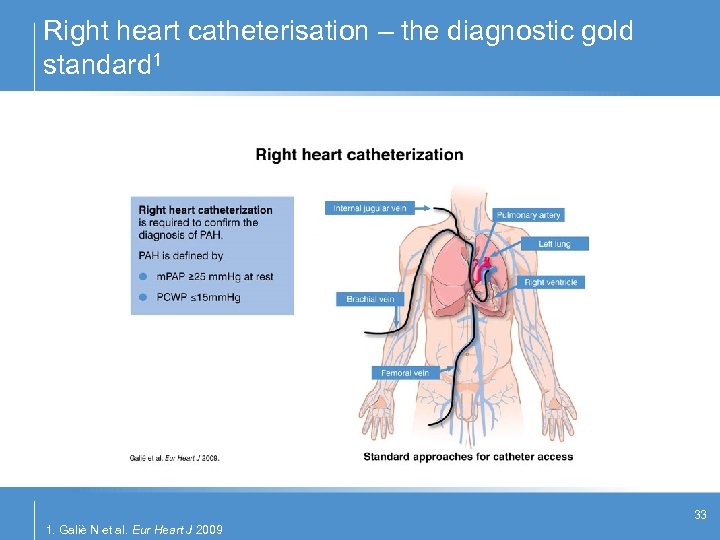

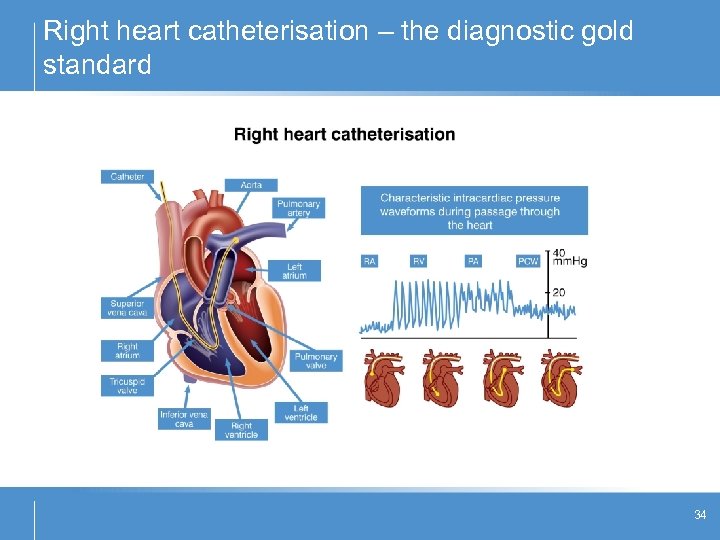

Right heart catheterisation – the diagnostic gold standard 1 33 1. Galiè N et al. Eur Heart J 2009

Right heart catheterisation – the diagnostic gold standard 34

Screening for PAH • Improving early diagnosis – screening high risk populations: – – – family members of a patient with heritable PAH (HPAH) patients with systemic sclerosis (SSc) patients with HIV patients with portopulmonary hypertension (Po. PH) patients with congenital heart disease • European and US guidelines recommend annual screening with Doppler echocardiography 1, 2 • Right heart catheterisation required for definitive diagnosis 35 1. Galiè N et al. Eur Heart J 2009; 2. Mc. Goon M et al. Chest 2004

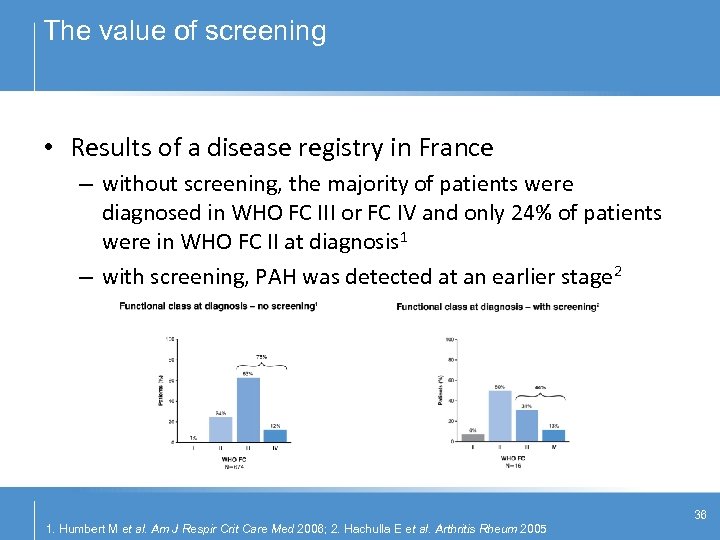

The value of screening • Results of a disease registry in France – without screening, the majority of patients were diagnosed in WHO FC III or FC IV and only 24% of patients were in WHO FC II at diagnosis 1 – with screening, PAH was detected at an earlier stage 2 36 1. Humbert M et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006; 2. Hachulla E et al. Arthritis Rheum 2005

Treating PAH 37

How is PAH treated? • Currently no cure for PAH • Modern advanced PAH therapies can markedly improve a patient’s symptoms and slow the rate of clinical deterioration 1, 2 • Management is complex, involving use of a range of treatment options: – – general measures conventional or supportive therapy advanced therapy (PAH-specific therapy) surgical intervention 38 1. Galiè N et al. Eur Heart J 2009; 2. Humbert M et al. Circulation 2010

General measures and supportive therapy • General measures 1– 3 – limit effects of external circumstances • avoid pregnancy • prevention and prompt treatment of chest infections • awareness of the potential effects of altitude • Conventional or supportive therapy 1– 3 – provide symptomatic benefit • • supplemental oxygen oral anticoagulants diuretics CCBs 1. Galiè N et al. Eur Heart J 2009; 2. Mc. Laughlin VV et al. Circulation 2009; 3. Badesch DB et al. Chest 2004 39

Advanced (PAH-specific) therapy • Endothelin receptor antagonists (ERAs) – oral treatments that act by blocking the binding of ET to either one (single antagonist) or both (dual antagonist) of its receptors 1 • Synthetic prostacyclins and prostacyclin analogues – act by helping to correct the deficiency of endogenous prostacyclin seen in patients with PAH – may be administered by intravenous infusion, 2 by subcutaneous infusion, 3, 4 or by inhalation 5 • Phosphodiesterase-5 (PDE-5) inhibitors – oral agents which act on NO pathway 1. Humbert M et al. N Engl J Med 2004; 2. Nicolas LB et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011; 3. Simonneau G et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002; 4. Barst RJ et al. Eur Respir J 2006; 5. Olschewski H et al. N Eng J Med 2002 40

Surgical intervention • Surgical intervention 1 – balloon atrial septostomy – lung or heart and lung transplantation 41 1. Galiè N et al. Eur Heart J 2009

Treatment guidelines: Goal-oriented therapy • Patients should be monitored regularly and response to therapy assessed using a range of parameters • Based on set goals, a patient’s condition at follow-up may be 1: – stable and satisfactory – stable but not satisfactory – unstable and deteriorating • ‘Stable but not satisfactory’ or ‘unstable and deteriorating’ → re-evaluation and consideration for escalation of treatment 42 1. Galiè N et al. Eur Heart J 2009

The importance of early identification and intervention in PAH • Early diagnosis and therapeutic intervention may offer an improved outlook for patients • Prognosis and response to treatment both shown to be better for patients with less severe disease (i. e. WHO Functional Class I/II)1 • Early diagnosis challenging: initial symptoms mild and non-specific • Many patients are not diagnosed until their disease is already quite severe 2 1. Sitbon O et al. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002; 2. Humbert M et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006 43

Assessing the patient 44

Assessing the severity of PAH • Assessment involves: – – – clinical assessment exercise tests biochemical markers echocardiographic assessment haemodynamic assessments 45

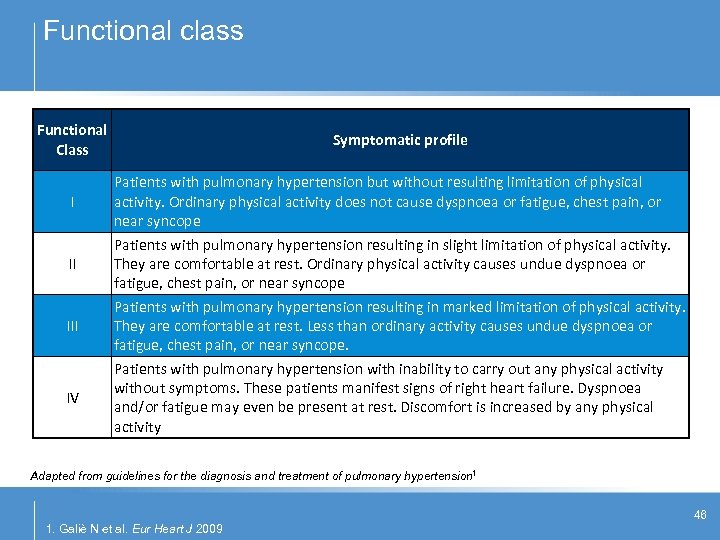

Functional class Functional Class I II IV Symptomatic profile Patients with pulmonary hypertension but without resulting limitation of physical activity. Ordinary physical activity does not cause dyspnoea or fatigue, chest pain, or near syncope Patients with pulmonary hypertension resulting in slight limitation of physical activity. They are comfortable at rest. Ordinary physical activity causes undue dyspnoea or fatigue, chest pain, or near syncope Patients with pulmonary hypertension resulting in marked limitation of physical activity. They are comfortable at rest. Less than ordinary activity causes undue dyspnoea or fatigue, chest pain, or near syncope. Patients with pulmonary hypertension with inability to carry out any physical activity without symptoms. These patients manifest signs of right heart failure. Dyspnoea and/or fatigue may even be present at rest. Discomfort is increased by any physical activity Adapted from guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension 1 46 1. Galiè N et al. Eur Heart J 2009

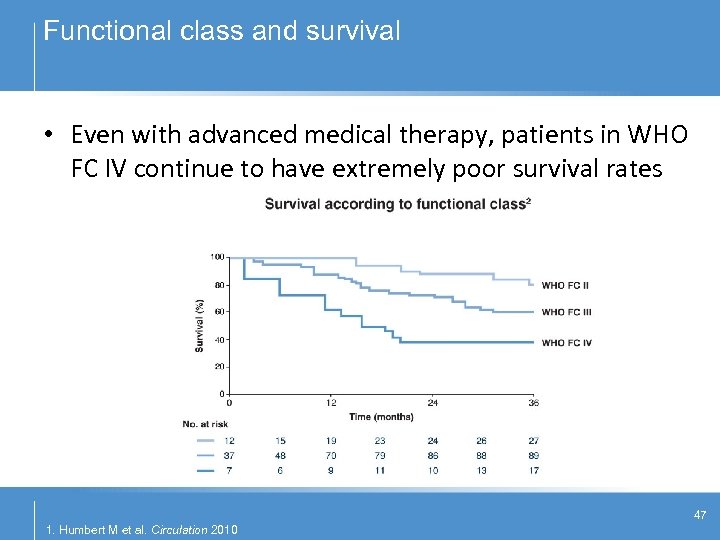

Functional class and survival • Even with advanced medical therapy, patients in WHO FC IV continue to have extremely poor survival rates 1 47 1. Humbert M et al. Circulation 2010

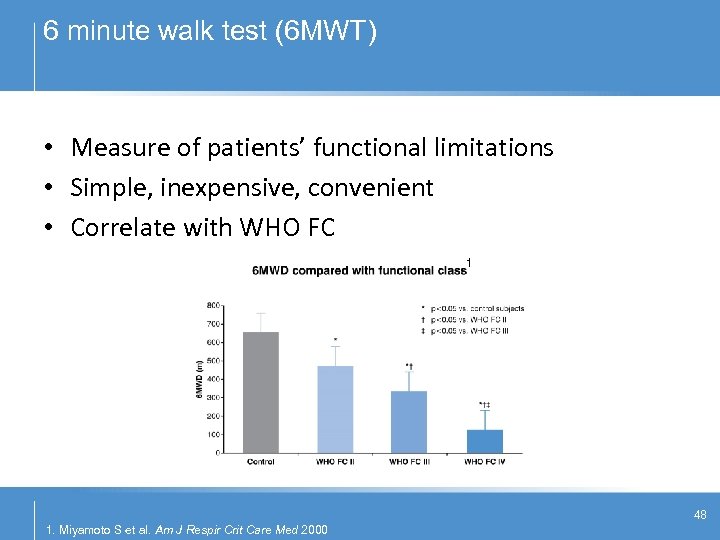

6 minute walk test (6 MWT) • Measure of patients’ functional limitations • Simple, inexpensive, convenient • Correlate with WHO FC 1 48 1. Miyamoto S et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000

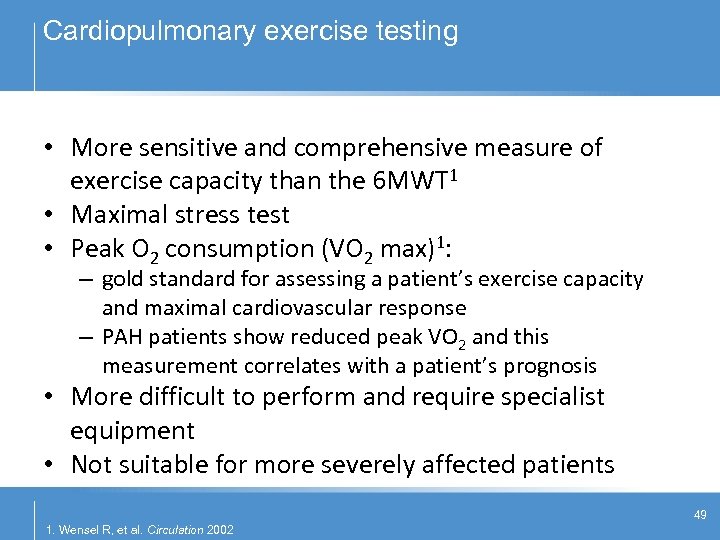

Cardiopulmonary exercise testing • More sensitive and comprehensive measure of exercise capacity than the 6 MWT 1 • Maximal stress test • Peak O 2 consumption (VO 2 max)1: – gold standard for assessing a patient’s exercise capacity and maximal cardiovascular response – PAH patients show reduced peak VO 2 and this measurement correlates with a patient’s prognosis • More difficult to perform and require specialist equipment • Not suitable for more severely affected patients 49 1. Wensel R, et al. Circulation 2002

Haemodynamic parameters • Measured by RHC • Correlate with clinical status, WHO FC, exercise capacity, and prognosis • Prognosis is significantly correlated with markers of right ventricular function 1, 2, 3 • Normalisation of haemodynamics may therefore be considered a suitable goal or treatment measure 1. Humbert M et al. Circulation 2010; 2. Mc. Laughlin VV et al. Circulation 2002; 3. Benza RL et al. Circulation 2010 . 50

Biochemical markers • Increases in serum NT-pro. BNP shown to be associated with prognosis in PAH 1 • Serum NT-pro. BNP < 1400 pg/m. L seems to identify patients with good prognosis 1, 2 • Cut-off levels still need to be verified in controlled trials 51 1. Galiè N et al. Eur Heart J 2009; 2. Fijalkowska A et al. Chest 2006

PAH-SSc explained 52

PAH in patients with SSc (PAH-SSc) • ~15 -25% of all cases of PAH are associated with connective tissue disease, particularly with SSc 1, 2 • Patients with SSc who develop PAH have poorer prognosis than those who do not 3, 4 • PAH accounts for more than 25% of all SSc-related deaths 5 • Need for early detection and timely treatment before patients show marked clinical and haemodynamic deterioration 6 1. Humbert M et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006; 2. Badesch DB et al. Chest 2010; 3. Hachulla E et al. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2009; 4. Steen VD, Medsger TA. Arthritis Rheum 2003; 5. Steen VD, Medsger TA. Ann Rheum Dis 2007. ; 6. Hachulla E et al. Arthritis Rheum 2005 53

How is PAH-SSc detected? • Diagnosis particularly challenging, especially in early stages • Symptoms of SSc such as fatigue and dyspnoea are also symptoms of PAH • Patients are often diagnosed late when they have advanced disease with severe clinical and haemodynamic impairment 1 • Screening for PAH in SSc is associated with improved outcomes 1 54 1. Humbert M et al. Arthritis Rheum 2011

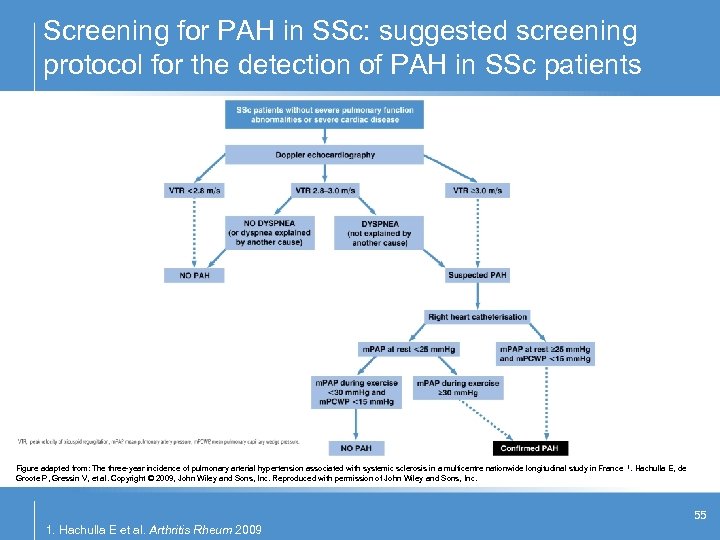

Screening for PAH in SSc: suggested screening protocol for the detection of PAH in SSc patients Figure adapted from: The three-year incidence of pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with systemic sclerosis in a multicentre nationwide longitudinal study in France 1. Hachulla E, de Groote P, Gressin V, et al. Copyright © 2009, John Wiley and Sons, Inc. Reproduced with permission of John Wiley and Sons, Inc. 55 1. Hachulla E et al. Arthritis Rheum 2009

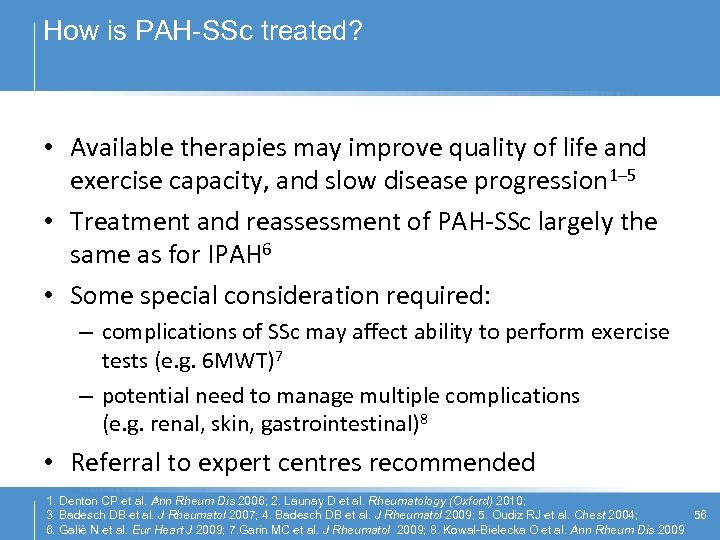

How is PAH-SSc treated? • Available therapies may improve quality of life and exercise capacity, and slow disease progression 1– 5 • Treatment and reassessment of PAH-SSc largely the same as for IPAH 6 • Some special consideration required: – complications of SSc may affect ability to perform exercise tests (e. g. 6 MWT)7 – potential need to manage multiple complications (e. g. renal, skin, gastrointestinal)8 • Referral to expert centres recommended 1. Denton CP et al. Ann Rheum Dis 2006; 2. Launay D et al. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2010; 3. Badesch DB et al. J Rheumatol 2007; 4. Badesch DB et al. J Rheumatol 2009; 5. Oudiz RJ et al. Chest 2004; 56 6. Galiè N et al. Eur Heart J 2009; 7. Garin MC et al. J Rheumatol 2009; 8. Kowal-Bielecka O et al. Ann Rheum Dis 2009

50a74e3fe020170af5b6a93c7996df0a.ppt