3458f294b6b866c8482131e5699ebfe6.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 61

Conversation Introducingthe analysis and Corpus Linguistics structure of spoken English Dr. Gloria Cappelli A/A 2006/2007 – University of Pisa

Conversation Introducingthe analysis and Corpus Linguistics structure of spoken English Dr. Gloria Cappelli A/A 2006/2007 – University of Pisa

Where are we? • We have seen the general features of spoken vs. written English (prof. Bruti); • We have seen that conversation is more than words; • We have considered the use of vague language; • We have seen narrative in conversation; • We have spoken about fillers and backchannels • We have spoken about ellipsis (dr. Bonsignori)

Where are we? • We have seen the general features of spoken vs. written English (prof. Bruti); • We have seen that conversation is more than words; • We have considered the use of vague language; • We have seen narrative in conversation; • We have spoken about fillers and backchannels • We have spoken about ellipsis (dr. Bonsignori)

What next? • We will talk about conversation analysis as a discipline • We will consider some structures of spoken language (adjacency pairs, insertion sequences, exchanges) • We will talk about tag questions

What next? • We will talk about conversation analysis as a discipline • We will consider some structures of spoken language (adjacency pairs, insertion sequences, exchanges) • We will talk about tag questions

Course Rational • With this second module, the students who want to obtain only 6 credits conclude the course. They will have learned the general features of spoken vs. written discourse and analysed some of these features in more detail.

Course Rational • With this second module, the students who want to obtain only 6 credits conclude the course. They will have learned the general features of spoken vs. written discourse and analysed some of these features in more detail.

Course Rational • The students who want to obtain 8 credits will attend 6 more lessons (12 hours), where they will get to know more on the way in which linguists study written and spoken discourse. This will give them some useful knowledge if they decide to write their final thesis in English Linguistics. ü corpus linguistics ü practical activities on DIY “corpora”

Course Rational • The students who want to obtain 8 credits will attend 6 more lessons (12 hours), where they will get to know more on the way in which linguists study written and spoken discourse. This will give them some useful knowledge if they decide to write their final thesis in English Linguistics. ü corpus linguistics ü practical activities on DIY “corpora”

We close the circle… • We actually started by presenting the premise that oral communication is structured in order to help us process information. • We then touched upon this matter when we talked about formulaic language in narratives. • Now that you can recognize certain other features of the spoken language that help the hearer recover the intended meaning, it seems appropriate to conclude this excursus with a deeper look at the features that can be used by speakers to structure conversation.

We close the circle… • We actually started by presenting the premise that oral communication is structured in order to help us process information. • We then touched upon this matter when we talked about formulaic language in narratives. • Now that you can recognize certain other features of the spoken language that help the hearer recover the intended meaning, it seems appropriate to conclude this excursus with a deeper look at the features that can be used by speakers to structure conversation.

Next year… … the course will focus on the way communication goes beyond structures and on how meaning is pragmatically construed.

Next year… … the course will focus on the way communication goes beyond structures and on how meaning is pragmatically construed.

Instinctive structure Spoken language = spontaneous there is no conscious plan to build a conversation. However… …speakers with similar knowledge work together at structuring and building the various types of conversation that we use daily.

Instinctive structure Spoken language = spontaneous there is no conscious plan to build a conversation. However… …speakers with similar knowledge work together at structuring and building the various types of conversation that we use daily.

Conversation Analysis Sacks, Schegloff and Jefferson (1974) C. A. derives from sociology and ethnomethodology. It argues that conversation has its own dynamic structure and rules. It looks at the methods used by speakers to structure conversation efficiently.

Conversation Analysis Sacks, Schegloff and Jefferson (1974) C. A. derives from sociology and ethnomethodology. It argues that conversation has its own dynamic structure and rules. It looks at the methods used by speakers to structure conversation efficiently.

Conversation Analysis Some fields of interest of CA: • The way people take turns • What turn-types there are CA. studies the organization of conversation. Conversation is organized in sequences.

Conversation Analysis Some fields of interest of CA: • The way people take turns • What turn-types there are CA. studies the organization of conversation. Conversation is organized in sequences.

Sequences and turns A sequence is a unit of conversation that consists of two or more and adjacent functionally related turns. A turn is a time during which a single participant speaks, within a typical, orderly arrangement in which participants speak with minimal overlap and gap between them.

Sequences and turns A sequence is a unit of conversation that consists of two or more and adjacent functionally related turns. A turn is a time during which a single participant speaks, within a typical, orderly arrangement in which participants speak with minimal overlap and gap between them.

Overlap in conversation • It seldom occurs - ”parties should talk one at a time” • Usually one drops out • Sometimes competition occurs • The speaker who upgrades most wins

Overlap in conversation • It seldom occurs - ”parties should talk one at a time” • Usually one drops out • Sometimes competition occurs • The speaker who upgrades most wins

Let’s start with an activity… As usual we start with a practical activity, which should help you experience in practice how conversation analysts work. Read the conversation in handout A and then answer the following questions…

Let’s start with an activity… As usual we start with a practical activity, which should help you experience in practice how conversation analysts work. Read the conversation in handout A and then answer the following questions…

• What appears to be the purpose of the conversation? • What topics are discussed? • How are topics introduced?

• What appears to be the purpose of the conversation? • What topics are discussed? • How are topics introduced?

Background information Two men, Andrew and David, in their early twenties, recorded this conversation while chatting to each other in David’s house.

Background information Two men, Andrew and David, in their early twenties, recorded this conversation while chatting to each other in David’s house.

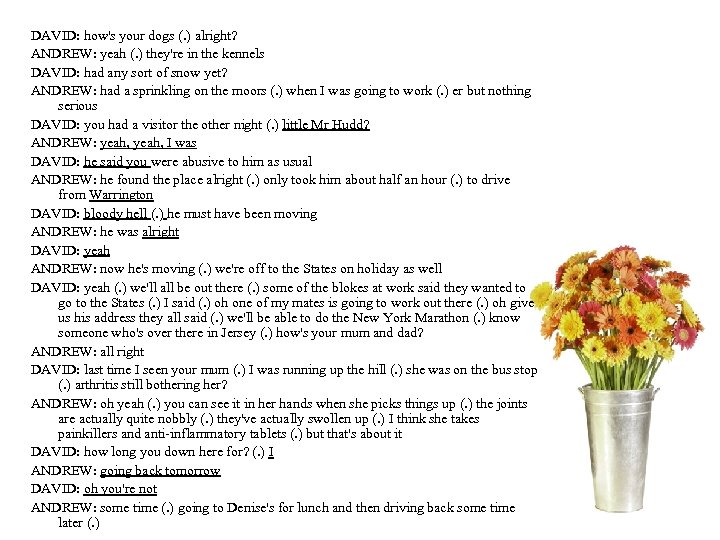

DAVID: how's your dogs (. ) alright? ANDREW: yeah (. ) they're in the kennels DAVID: had any sort of snow yet? ANDREW: had a sprinkling on the moors (. ) when I was going to work (. ) er but nothing serious DAVID: you had a visitor the other night (. ) little Mr Hudd? ANDREW: yeah, I was DAVID: he said you were abusive to him as usual ANDREW: he found the place alright (. ) only took him about half an hour (. ) to drive from Warrington DAVID: bloody hell (. ) he must have been moving ANDREW: he was alright DAVID: yeah ANDREW: now he's moving (. ) we're off to the States on holiday as well DAVID: yeah (. ) we'll all be out there (. ) some of the blokes at work said they wanted to go to the States (. ) I said (. ) oh one of my mates is going to work out there (. ) oh give us his address they all said (. ) we'll be able to do the New York Marathon (. ) know someone who's over there in Jersey (. ) how's your mum and dad? ANDREW: all right DAVID: last time I seen your mum (. ) I was running up the hill (. ) she was on the bus stop (. ) arthritis still bothering her? ANDREW: oh yeah (. ) you can see it in her hands when she picks things up (. ) the joints are actually quite nobbly (. ) they've actually swollen up (. ) I think she takes painkillers and anti-inflammatory tablets (. ) but that's about it DAVID: how long you down here for? (. ) I ANDREW: going back tomorrow DAVID: oh you're not ANDREW: some time (. ) going to Denise's for lunch and then driving back some time later (. )

DAVID: how's your dogs (. ) alright? ANDREW: yeah (. ) they're in the kennels DAVID: had any sort of snow yet? ANDREW: had a sprinkling on the moors (. ) when I was going to work (. ) er but nothing serious DAVID: you had a visitor the other night (. ) little Mr Hudd? ANDREW: yeah, I was DAVID: he said you were abusive to him as usual ANDREW: he found the place alright (. ) only took him about half an hour (. ) to drive from Warrington DAVID: bloody hell (. ) he must have been moving ANDREW: he was alright DAVID: yeah ANDREW: now he's moving (. ) we're off to the States on holiday as well DAVID: yeah (. ) we'll all be out there (. ) some of the blokes at work said they wanted to go to the States (. ) I said (. ) oh one of my mates is going to work out there (. ) oh give us his address they all said (. ) we'll be able to do the New York Marathon (. ) know someone who's over there in Jersey (. ) how's your mum and dad? ANDREW: all right DAVID: last time I seen your mum (. ) I was running up the hill (. ) she was on the bus stop (. ) arthritis still bothering her? ANDREW: oh yeah (. ) you can see it in her hands when she picks things up (. ) the joints are actually quite nobbly (. ) they've actually swollen up (. ) I think she takes painkillers and anti-inflammatory tablets (. ) but that's about it DAVID: how long you down here for? (. ) I ANDREW: going back tomorrow DAVID: oh you're not ANDREW: some time (. ) going to Denise's for lunch and then driving back some time later (. )

• What appears to be the purpose of the conversation? • Informal chat between two young men (they are catching up on each other’s news) • The purpose of the conversation is primarily INTERACTIONAL – Transactional = to obtain good or services, to organize some sort of action, to pass on real information vs. – Interactional = used when people relate to each other (Brown and Yule 1983)

• What appears to be the purpose of the conversation? • Informal chat between two young men (they are catching up on each other’s news) • The purpose of the conversation is primarily INTERACTIONAL – Transactional = to obtain good or services, to organize some sort of action, to pass on real information vs. – Interactional = used when people relate to each other (Brown and Yule 1983)

What topics are discussed? A range of topics are covered, e. g. dogs, snow, little Mr. Hudd, going to the States, Andrew’s mum, how long Andrew is going to stay. Each of the speakers speaks 8 times = 16 utterances and 6 topics! The topics change very quickly and in fact one topic is often dealt with in the space of 2 utterances.

What topics are discussed? A range of topics are covered, e. g. dogs, snow, little Mr. Hudd, going to the States, Andrew’s mum, how long Andrew is going to stay. Each of the speakers speaks 8 times = 16 utterances and 6 topics! The topics change very quickly and in fact one topic is often dealt with in the space of 2 utterances.

How are topics introduced? The topics are introduced in 2 ways: • statements – We’re off to the States on holiday as well • questions – You had a visitor the other night, little Mr Hudd?

How are topics introduced? The topics are introduced in 2 ways: • statements – We’re off to the States on holiday as well • questions – You had a visitor the other night, little Mr Hudd?

How are topics introduced? Even when the form of the utterance looks like a statement, the rising intonation at the end of the utterance implies to the listener that this is a question that needs answering.

How are topics introduced? Even when the form of the utterance looks like a statement, the rising intonation at the end of the utterance implies to the listener that this is a question that needs answering.

How are topics introduced? David introduces more topics. On line 6, D. ’s question functions as a device to check A’s interaction rather than a genuine enquiry. When A. replies “yeah, yeah I was” and seems to be ready to add more information, he’ interrupted by D. who wants to display what he already knows rather than to listen to what he might not know.

How are topics introduced? David introduces more topics. On line 6, D. ’s question functions as a device to check A’s interaction rather than a genuine enquiry. When A. replies “yeah, yeah I was” and seems to be ready to add more information, he’ interrupted by D. who wants to display what he already knows rather than to listen to what he might not know.

How are topics introduced? The same desire to HOLD THE TURN is shown later in the conversation when D. slips into retelling a conversation that he had already had at work. Though this story doesn’t last very long, this utterance of 62 words is by far the longest in the conversation, turning A. into a listener rather than a speaker.

How are topics introduced? The same desire to HOLD THE TURN is shown later in the conversation when D. slips into retelling a conversation that he had already had at work. Though this story doesn’t last very long, this utterance of 62 words is by far the longest in the conversation, turning A. into a listener rather than a speaker.

Building the conversation The two men, however, build the conversation together. • A. answers every question set by D. • He allows D. to interrupt him • After an interruption, he makes no attempt to return to his original topic • He continues with D. • D. appreciates the remark A. makes about the drive from Warrington wit his remark ‘bloody hell (. ) he must have been moving’ • He ads ‘yeah’ twice to encourage A. in what he’s saying.

Building the conversation The two men, however, build the conversation together. • A. answers every question set by D. • He allows D. to interrupt him • After an interruption, he makes no attempt to return to his original topic • He continues with D. • D. appreciates the remark A. makes about the drive from Warrington wit his remark ‘bloody hell (. ) he must have been moving’ • He ads ‘yeah’ twice to encourage A. in what he’s saying.

Building the conversation The conversation seems to have been structured with the willing cooperation of both partners and the basic structural device used to introduce topics and to build the conversation has been the adjacency pair of question-answer.

Building the conversation The conversation seems to have been structured with the willing cooperation of both partners and the basic structural device used to introduce topics and to build the conversation has been the adjacency pair of question-answer.

Types of sequences Adjacency pairs are a type of sequence, along with: • Insertion sequences • Pre-sequences • Post-sequences Conversational encounters can be described in terms of an overall organization, that is, a schematic description of the types and order of a conversation’s turns and sequences.

Types of sequences Adjacency pairs are a type of sequence, along with: • Insertion sequences • Pre-sequences • Post-sequences Conversational encounters can be described in terms of an overall organization, that is, a schematic description of the types and order of a conversation’s turns and sequences.

Adjacency pairs An adjacency pair is a unit of conversation that contains an exchange of one turn each by two speakers. The turns are functionally related to each other in such a fashion that the first turn requires a certain type or range of types of second turn. E. g. : – A greeting–greeting pair – A question–answer pair

Adjacency pairs An adjacency pair is a unit of conversation that contains an exchange of one turn each by two speakers. The turns are functionally related to each other in such a fashion that the first turn requires a certain type or range of types of second turn. E. g. : – A greeting–greeting pair – A question–answer pair

Functions of adjacency pairs • Adjacency pairs are used for starting and closing a conversation • Adjacency pairs are used for moves in conversations • First utterance in adjacency pair has the function of selecting next speaker • Adjacency pairs are used for remedial exchanges • Components in adjacency pairs can be used to build longer sequences

Functions of adjacency pairs • Adjacency pairs are used for starting and closing a conversation • Adjacency pairs are used for moves in conversations • First utterance in adjacency pair has the function of selecting next speaker • Adjacency pairs are used for remedial exchanges • Components in adjacency pairs can be used to build longer sequences

Adjacency pairs • Question – answer • Greeting – greeting • Offer – acceptance • Request – acceptance • Complaint - excuse

Adjacency pairs • Question – answer • Greeting – greeting • Offer – acceptance • Request – acceptance • Complaint - excuse

Adjacency pairs One speaker’s utterance makes a particular kind of response likely. A. P. are pairs of utterances that usually occur together. The most often used a. p. of the conversation analysed is question-answer. In our culture, a question is generally followed by an answer and is therefore a convenient way to introduce a new topic and to ensure a response.

Adjacency pairs One speaker’s utterance makes a particular kind of response likely. A. P. are pairs of utterances that usually occur together. The most often used a. p. of the conversation analysed is question-answer. In our culture, a question is generally followed by an answer and is therefore a convenient way to introduce a new topic and to ensure a response.

Question and answers The level of response varies according to the type of question used. Questions can be divided into closed and open questions. ‘Wh-’ questions and ‘how’ questions are generally opened, as they leave a fairly open agenda for the speaker who answers. Closed questions are also called yes-no questions.

Question and answers The level of response varies according to the type of question used. Questions can be divided into closed and open questions. ‘Wh-’ questions and ‘how’ questions are generally opened, as they leave a fairly open agenda for the speaker who answers. Closed questions are also called yes-no questions.

Types of questions The “openness” of a question varies with the context. DAVID: how's your dogs (. ) alright? ANDREW: yeah (. ) they're in the kennels David asks two questions in one turn, an open one and a closed one. While the first question seems an open, interested and genuine enquiry, the second is closed and signals that this is just a comment in passing. D. has probaby already assumed that the dogs are fine and is seeking for confirmation and nothing more.

Types of questions The “openness” of a question varies with the context. DAVID: how's your dogs (. ) alright? ANDREW: yeah (. ) they're in the kennels David asks two questions in one turn, an open one and a closed one. While the first question seems an open, interested and genuine enquiry, the second is closed and signals that this is just a comment in passing. D. has probaby already assumed that the dogs are fine and is seeking for confirmation and nothing more.

Type of questions Some questions, therefore, are not meant to get a real lenghty answer, but just to structure the conversation. How much a question throws open a topic depends on the nature of the question and on the context.

Type of questions Some questions, therefore, are not meant to get a real lenghty answer, but just to structure the conversation. How much a question throws open a topic depends on the nature of the question and on the context.

Tag Questions One of the most interesting types of questions are TAG QUESTIONS. The way in which they operate depends on the intonation used and on the context they appear in.

Tag Questions One of the most interesting types of questions are TAG QUESTIONS. The way in which they operate depends on the intonation used and on the context they appear in.

Tag Questions They can show tentativeness: – This is a good match, isn’t it? They can show assertiveness: – You’re not leaving, are you? You will learn more about tag questions on April 12.

Tag Questions They can show tentativeness: – This is a good match, isn’t it? They can show assertiveness: – You’re not leaving, are you? You will learn more about tag questions on April 12.

Questions and answers It is difficult to avoid answering repeated questions and as the urgency of the question increases, the length of the question decreases. In other words, short sharp questions are forceful in provoking a response.

Questions and answers It is difficult to avoid answering repeated questions and as the urgency of the question increases, the length of the question decreases. In other words, short sharp questions are forceful in provoking a response.

Activity Are the following open or closed questions? • Did you enjoy the spaghetti bolognese? • Do you love her? • I think the Labour candidate’s the best, don’t you? • Are you going to put up with that? • What plans have you for the next few years?

Activity Are the following open or closed questions? • Did you enjoy the spaghetti bolognese? • Do you love her? • I think the Labour candidate’s the best, don’t you? • Are you going to put up with that? • What plans have you for the next few years?

Possible types of answers • Answer • Assurance of ignorance • Suggestion for asking someone else (re-routing) • Postponement • Refusal to provide an answer • Challenge to presuppositions of question • Challenge to questioner’s sincerity

Possible types of answers • Answer • Assurance of ignorance • Suggestion for asking someone else (re-routing) • Postponement • Refusal to provide an answer • Challenge to presuppositions of question • Challenge to questioner’s sincerity

Breaking adjacency pairs As an accepted part of conversational structure, adjacency pairs have strong in-built expectations. Questions are generally answered, statements are acknowledged, complaints are replied to and greetings are exchanged.

Breaking adjacency pairs As an accepted part of conversational structure, adjacency pairs have strong in-built expectations. Questions are generally answered, statements are acknowledged, complaints are replied to and greetings are exchanged.

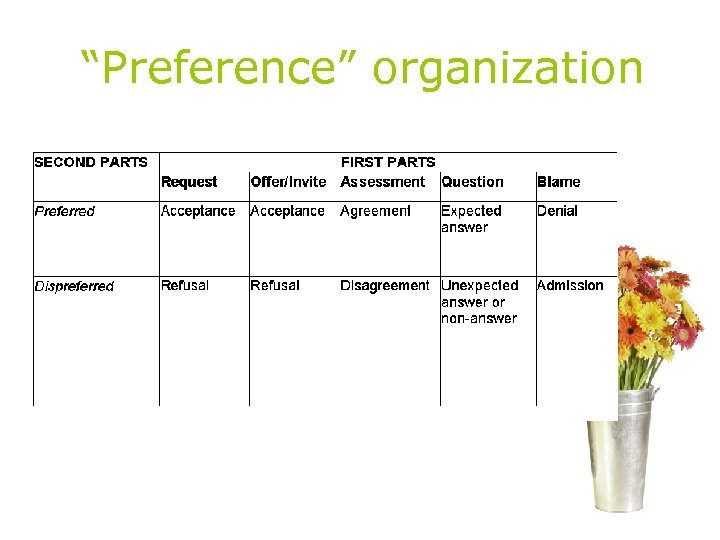

“Preference” organization Adjacency pairs have “preferences”: • Preferred response = granting • Dispreferred response = refusal Dispreferred responses are often – Delayed – Marked (preface marking dispreferred status)

“Preference” organization Adjacency pairs have “preferences”: • Preferred response = granting • Dispreferred response = refusal Dispreferred responses are often – Delayed – Marked (preface marking dispreferred status)

“Preference” organization AP are organized in first and second part. For any particular first part speech act (proposal, request), conversationalists show a preference for particular second parts in response (acceptance, grant). We can distinguish between preferred second parts and dispreferred second parts (rejection, refusal).

“Preference” organization AP are organized in first and second part. For any particular first part speech act (proposal, request), conversationalists show a preference for particular second parts in response (acceptance, grant). We can distinguish between preferred second parts and dispreferred second parts (rejection, refusal).

“Preference” organization

“Preference” organization

Breaking Adjacency Pairs If the rules are ignored and these patterns are broken (even by choosing the dispreferred second part), this immediately creates a response.

Breaking Adjacency Pairs If the rules are ignored and these patterns are broken (even by choosing the dispreferred second part), this immediately creates a response.

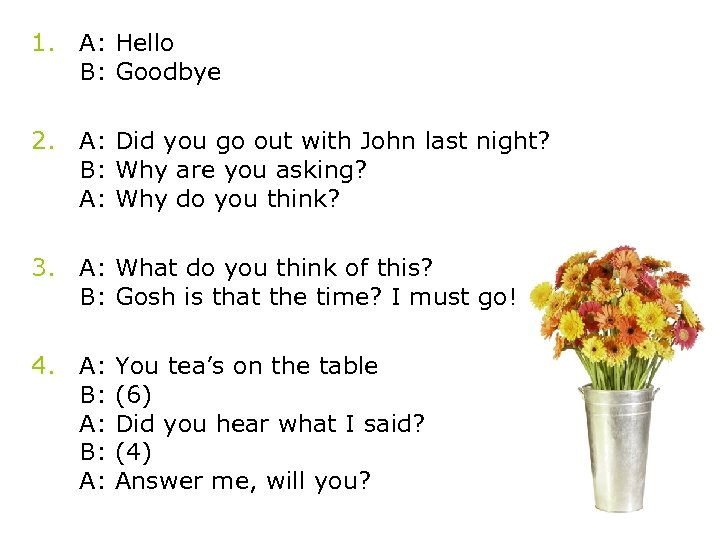

Activity Look at the following exchanges and discuss how they appear to flout the normal expectations of adjacency pairs. Can you imagine contexts which would explain these?

Activity Look at the following exchanges and discuss how they appear to flout the normal expectations of adjacency pairs. Can you imagine contexts which would explain these?

1. A: Hello B: Goodbye 2. A: Did you go out with John last night? B: Why are you asking? A: Why do you think? 3. A: What do you think of this? B: Gosh is that the time? I must go! 4. A: B: A: You tea’s on the table (6) Did you hear what I said? (4) Answer me, will you?

1. A: Hello B: Goodbye 2. A: Did you go out with John last night? B: Why are you asking? A: Why do you think? 3. A: What do you think of this? B: Gosh is that the time? I must go! 4. A: B: A: You tea’s on the table (6) Did you hear what I said? (4) Answer me, will you?

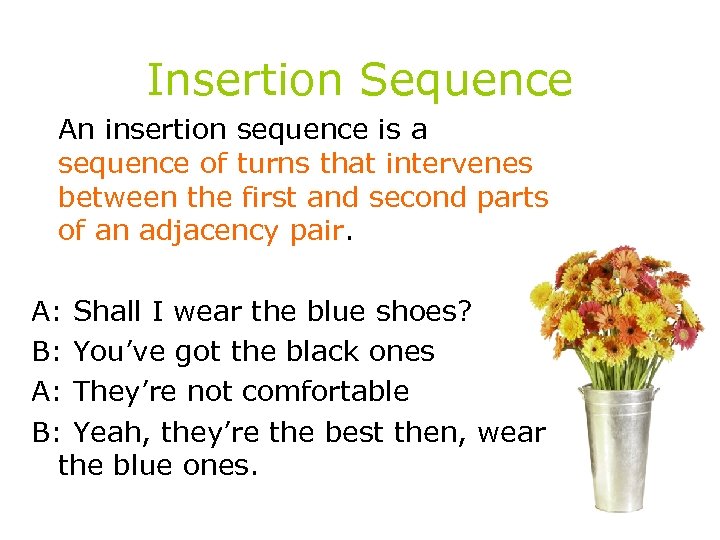

Insertion Sequence An insertion sequence is a sequence of turns that intervenes between the first and second parts of an adjacency pair. A: Shall I wear the blue shoes? B: You’ve got the black ones A: They’re not comfortable B: Yeah, they’re the best then, wear the blue ones.

Insertion Sequence An insertion sequence is a sequence of turns that intervenes between the first and second parts of an adjacency pair. A: Shall I wear the blue shoes? B: You’ve got the black ones A: They’re not comfortable B: Yeah, they’re the best then, wear the blue ones.

Insertion Sequence The topic of the insertion sequence is related to that of the main sequence in which it occurs and the question from the main sequence is returned to and answered after the insertion.

Insertion Sequence The topic of the insertion sequence is related to that of the main sequence in which it occurs and the question from the main sequence is returned to and answered after the insertion.

Insertion Sequence A: I wanted to order some more paint. (Request) B: Yes, how many tubes would you like, sir? (Question 1) A: Um, what's the price with tax? (Question 2) B: Er, I'll just work that out for you. (Hold) A: Thanks. (Acceptance) B: Three nineteen a tube, sir. (Answer 2) A: I'll have five, then. (Answer 1) B: Here you go. (Acceptance)

Insertion Sequence A: I wanted to order some more paint. (Request) B: Yes, how many tubes would you like, sir? (Question 1) A: Um, what's the price with tax? (Question 2) B: Er, I'll just work that out for you. (Hold) A: Thanks. (Acceptance) B: Three nineteen a tube, sir. (Answer 2) A: I'll have five, then. (Answer 1) B: Here you go. (Acceptance)

Insertion Sequences as a kind of Delay A delay is an item used to put off a dispreferred second part. A dispreferred second part is a second part of an adjacency pair that consists of a response to the first part that is generally to be avoided or not expected. – A refusal in response to a request, offer, or invitation – A disagreement in response to an assessment – An unexpected answer in response to a question – An admission in response to blame

Insertion Sequences as a kind of Delay A delay is an item used to put off a dispreferred second part. A dispreferred second part is a second part of an adjacency pair that consists of a response to the first part that is generally to be avoided or not expected. – A refusal in response to a request, offer, or invitation – A disagreement in response to an assessment – An unexpected answer in response to a question – An admission in response to blame

Insertion Sequences as a kind of Delay The following exchange contains delays as a repair initiation in the second turn, insertion sequences in the fourth and fifth turns, and the well, pause, and self-repair in the sixth turn: 1. A: Can you do it? 2. B: What? 3. A: Can you take care of it? 4. B: Now? 5. A: If that’s all right. 6. B: Well, [pause] I mean, no, I’m afraid not.

Insertion Sequences as a kind of Delay The following exchange contains delays as a repair initiation in the second turn, insertion sequences in the fourth and fifth turns, and the well, pause, and self-repair in the sixth turn: 1. A: Can you do it? 2. B: What? 3. A: Can you take care of it? 4. B: Now? 5. A: If that’s all right. 6. B: Well, [pause] I mean, no, I’m afraid not.

Fillers as a kind of Delay In conversation analysis they are also known as a ‘preface’, that is, an audible device, such as one of the following, used within a turn to put off a dispreferred response: • Items like well • Token agreement • Indications of appreciation, apology, or qualification • Self-repair E. g. : Um, yes, thanks, but you--I mean, I’ll just do it myself.

Fillers as a kind of Delay In conversation analysis they are also known as a ‘preface’, that is, an audible device, such as one of the following, used within a turn to put off a dispreferred response: • Items like well • Token agreement • Indications of appreciation, apology, or qualification • Self-repair E. g. : Um, yes, thanks, but you--I mean, I’ll just do it myself.

Exchange Structure Adjacency pairs can also be extended into adjacency triplets. Identified by Sinclair and Coulthard (1975) in their analysis of classroom conversations, and more commonly known as exchanges, they consist of three moves: • Initiation • Response • Follow-up or Feedback

Exchange Structure Adjacency pairs can also be extended into adjacency triplets. Identified by Sinclair and Coulthard (1975) in their analysis of classroom conversations, and more commonly known as exchanges, they consist of three moves: • Initiation • Response • Follow-up or Feedback

Hands-on work The following conversation took place in a chemistry lesson in the classroom of a sixth form college. SDR is a male teacher in his early fifties, FP is his pupil, a female 17 -year-old student. Read the following transcription of a classroom conversation and answer the questions:

Hands-on work The following conversation took place in a chemistry lesson in the classroom of a sixth form college. SDR is a male teacher in his early fifties, FP is his pupil, a female 17 -year-old student. Read the following transcription of a classroom conversation and answer the questions:

Hands-on work 1. What is the purpose behind the teacher's opening remarks? 2. Identify and explain the exchange in this conversation. 3. Explain the function of the adjacency pair at the end of the conversation. 4. How does the teacher pass on the turn and introduce the topics? 5. What is the reason for the repetition present in this conversation?

Hands-on work 1. What is the purpose behind the teacher's opening remarks? 2. Identify and explain the exchange in this conversation. 3. Explain the function of the adjacency pair at the end of the conversation. 4. How does the teacher pass on the turn and introduce the topics? 5. What is the reason for the repetition present in this conversation?

SDR: that's good (. ) that's excellent (. ) so you can answer the questions (1) Fiona (. ) if you heat up the reaction (. ) what happens? (. ) to the reaction FP: it goes quicker SDR: it goes quicker (. ) so the key to any reaction at all is that it goes quicker (. ) because all the molecules will be flying around faster (. ) so it speeds up a reaction (. ) but it speeds up a given (1) increase in temperature speeds of different reactions to different extents (1) Fiona (. ) exothermic reactions (. ) what is an exothermic reaction? (1) FP: one that gives out heat

SDR: that's good (. ) that's excellent (. ) so you can answer the questions (1) Fiona (. ) if you heat up the reaction (. ) what happens? (. ) to the reaction FP: it goes quicker SDR: it goes quicker (. ) so the key to any reaction at all is that it goes quicker (. ) because all the molecules will be flying around faster (. ) so it speeds up a reaction (. ) but it speeds up a given (1) increase in temperature speeds of different reactions to different extents (1) Fiona (. ) exothermic reactions (. ) what is an exothermic reaction? (1) FP: one that gives out heat

What is the purpose behind the teacher's opening remarks? The teacher's first three remarks, 'that's good', 'that's excellent' and 'so you can answer the questions', are concerned with the previous utterances made by the students. The evaluation offered here by the teacher is extremely positive and supportive in a way that could appear patronising in a normal situation.

What is the purpose behind the teacher's opening remarks? The teacher's first three remarks, 'that's good', 'that's excellent' and 'so you can answer the questions', are concerned with the previous utterances made by the students. The evaluation offered here by the teacher is extremely positive and supportive in a way that could appear patronising in a normal situation.

Identify and explain the exchange in this conversation. The exchange that follows is initiated by the teacher's question, 'if you heat up any reaction what happens? (. ) to the reaction (1)'. FP responds with the answer 'it goes quicker'. Then the teacher, as feedback, not only repeats the student's exact words but also reformulates the answer and summarises for the students what he hopes the exchange has taught them, 'so the key to any reaction at all is that it goes quicker'.

Identify and explain the exchange in this conversation. The exchange that follows is initiated by the teacher's question, 'if you heat up any reaction what happens? (. ) to the reaction (1)'. FP responds with the answer 'it goes quicker'. Then the teacher, as feedback, not only repeats the student's exact words but also reformulates the answer and summarises for the students what he hopes the exchange has taught them, 'so the key to any reaction at all is that it goes quicker'.

Explain the function of the adjacency pair at the end of the conversation. The adjacency pair at the end is asking the students to give a definition. This is a knownanswer question in the sense that the teacher already knows what he wants to hear and Fiona's answer comes quickly and fluently in a way that implies the definition has been learnt almost by heart.

Explain the function of the adjacency pair at the end of the conversation. The adjacency pair at the end is asking the students to give a definition. This is a knownanswer question in the sense that the teacher already knows what he wants to hear and Fiona's answer comes quickly and fluently in a way that implies the definition has been learnt almost by heart.

How does the teacher pass on the turn and introduce the topics? The teacher clearly dictates the turn by naming Fiona twice and the topics are introduced by two questions, 'if you heat up any reaction what happens? ' and 'what is an exothermic reaction? ' Interestingly, the final topic has already been signposted to the audience with the phrase, 'exothermic reactions'. Operating as a sub-heading would in a written text, the repetition of this phrase in the next sentence reflects the high amount of repetition already contained in the conversation.

How does the teacher pass on the turn and introduce the topics? The teacher clearly dictates the turn by naming Fiona twice and the topics are introduced by two questions, 'if you heat up any reaction what happens? ' and 'what is an exothermic reaction? ' Interestingly, the final topic has already been signposted to the audience with the phrase, 'exothermic reactions'. Operating as a sub-heading would in a written text, the repetition of this phrase in the next sentence reflects the high amount of repetition already contained in the conversation.

What is the reason for the repetition present in this conversation? The repetition shows the teacher’s constant awareness of his larger audience and his purpose – to make sure all his students learn, not just the student he appears to be having a conversation with. Throughout the conversation, therefore, he is at pains by repetition to confirm the class’ understanding.

What is the reason for the repetition present in this conversation? The repetition shows the teacher’s constant awareness of his larger audience and his purpose – to make sure all his students learn, not just the student he appears to be having a conversation with. Throughout the conversation, therefore, he is at pains by repetition to confirm the class’ understanding.

Summary Conversation is, therefore, a flexible text negotiated between the various participants in a conversation. The speakers and listeners support and evaluate each other using the known building blocks of adjacency pairs and exchanges and operating with pragmatic principles. Nonfluency features help signpost the structure of the conversation as do openers, discourse markers and closures. This signposting causes the participants to be aware of the conversation's structure, enabling a smooth progression from topic to topic and from speaker to speaker. Finally, the context and underlying purposes of a conversation make its meaning clear to all participants.

Summary Conversation is, therefore, a flexible text negotiated between the various participants in a conversation. The speakers and listeners support and evaluate each other using the known building blocks of adjacency pairs and exchanges and operating with pragmatic principles. Nonfluency features help signpost the structure of the conversation as do openers, discourse markers and closures. This signposting causes the participants to be aware of the conversation's structure, enabling a smooth progression from topic to topic and from speaker to speaker. Finally, the context and underlying purposes of a conversation make its meaning clear to all participants.

Food for thought We are left to consider whether conversation will develop or change due to the influence of new technology and the conversations that take place in emails and chat rooms. See handout.

Food for thought We are left to consider whether conversation will develop or change due to the influence of new technology and the conversations that take place in emails and chat rooms. See handout.