2bd0a756d88d129ddab638ed6e926738.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 55

Consumer Judgment and Decision Making Professor Charles Hofacker chofack@cob. fsu. edu Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker 0

Consumer Judgment and Decision Making Professor Charles Hofacker chofack@cob. fsu. edu Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker 0

The Persistence of Illusion Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker 1

The Persistence of Illusion Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker 1

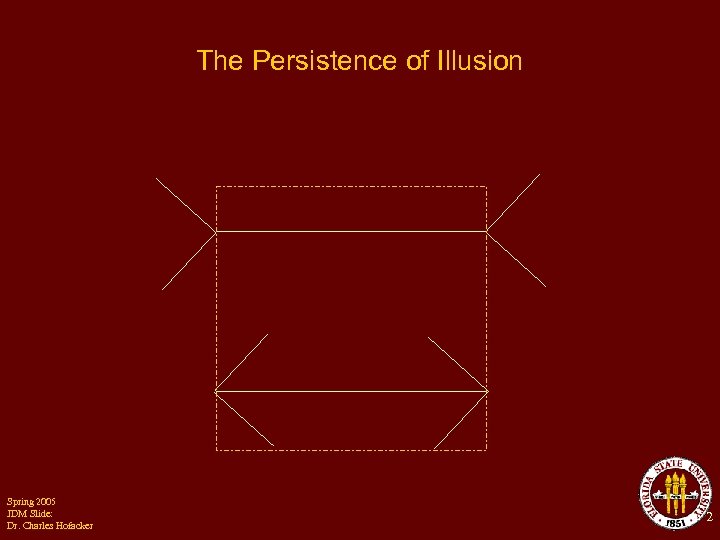

The Persistence of Illusion Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker 2

The Persistence of Illusion Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker 2

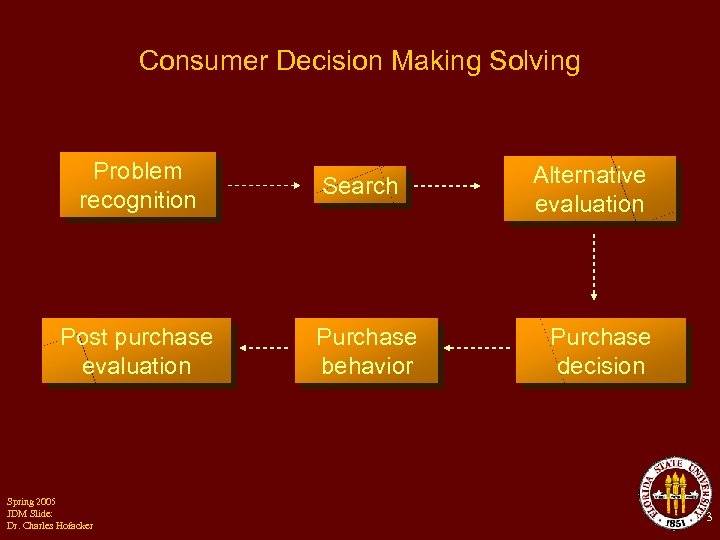

Consumer Decision Making Solving Problem recognition Search Post purchase evaluation Purchase behavior Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker Alternative evaluation Purchase decision 3

Consumer Decision Making Solving Problem recognition Search Post purchase evaluation Purchase behavior Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker Alternative evaluation Purchase decision 3

![Standard Economic Theory of Consumer Choice x = [x 1 x 2 ··· xn] Standard Economic Theory of Consumer Choice x = [x 1 x 2 ··· xn]](https://present5.com/presentation/2bd0a756d88d129ddab638ed6e926738/image-5.jpg) Standard Economic Theory of Consumer Choice x = [x 1 x 2 ··· xn] vector of goods available c = [c 1 c 2 ··· cn] prices for those goods u(x) consumer’s utility function I consumer’s income Max u(x) s. t. x Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker ci xi I i According to rational decision theory, the consumer picks the optimal bundle of goods from x. 4

Standard Economic Theory of Consumer Choice x = [x 1 x 2 ··· xn] vector of goods available c = [c 1 c 2 ··· cn] prices for those goods u(x) consumer’s utility function I consumer’s income Max u(x) s. t. x Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker ci xi I i According to rational decision theory, the consumer picks the optimal bundle of goods from x. 4

The Theory of Bounded Rationality Theory attributed to Herbert Simon as a critique of rational decision theory. The optimization process should take into account q q Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker cognitive limitations finite time availability Ratchford, Brian T. (1982), "Cost-Benefit Models for Explaining Consumer Choice and Information Seeking Behavior, " Management Science, 28 (2), 197 -212. 5

The Theory of Bounded Rationality Theory attributed to Herbert Simon as a critique of rational decision theory. The optimization process should take into account q q Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker cognitive limitations finite time availability Ratchford, Brian T. (1982), "Cost-Benefit Models for Explaining Consumer Choice and Information Seeking Behavior, " Management Science, 28 (2), 197 -212. 5

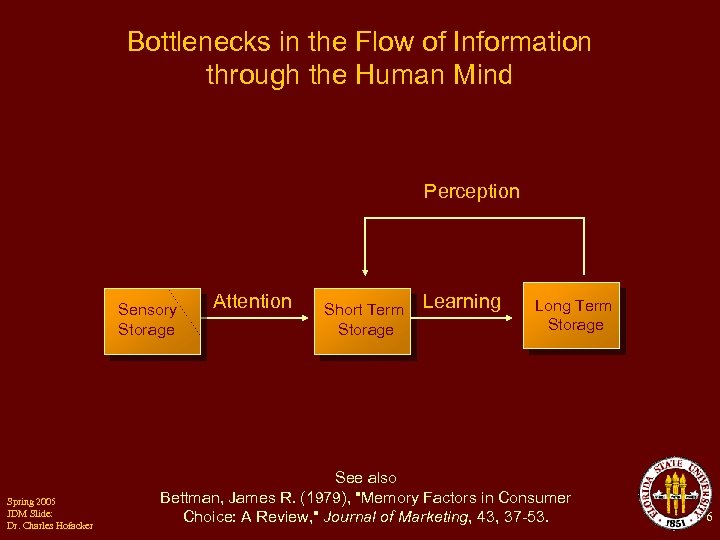

Bottlenecks in the Flow of Information through the Human Mind Perception Sensory Storage Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker Attention Short Term Storage Learning Long Term Storage See also Bettman, James R. (1979), "Memory Factors in Consumer Choice: A Review, " Journal of Marketing, 43, 37 -53. 6

Bottlenecks in the Flow of Information through the Human Mind Perception Sensory Storage Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker Attention Short Term Storage Learning Long Term Storage See also Bettman, James R. (1979), "Memory Factors in Consumer Choice: A Review, " Journal of Marketing, 43, 37 -53. 6

Satisficing Simon coined this term which means acting just rational enough It is a special case of bounded rationality applied to sequential decision w/ no objectively optimal stopping point A consumer might pick the first option that exceeds some key threshold cutoffs Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker 7

Satisficing Simon coined this term which means acting just rational enough It is a special case of bounded rationality applied to sequential decision w/ no objectively optimal stopping point A consumer might pick the first option that exceeds some key threshold cutoffs Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker 7

Choosing How to Choose A consumer must tradeoff the quality of the decision against the opportunity costs of the time and the effort Johnson, Eric J. and John W. Payne (1985), "Effort and Accuracy in Choice, " Management Science, 31 (4), 395 -414. Payne, John W. , James R. Bettman, and Eric J. Johnson (1988), "Adaptive Strategy Selection in Decision Making, " Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory and Cognition, 14 (3), 534 -52. Shugan, Steven M. (1980), "The Cost of Thinking, " Journal of Consumer Research, 7 (2), 99 -111. Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker 8

Choosing How to Choose A consumer must tradeoff the quality of the decision against the opportunity costs of the time and the effort Johnson, Eric J. and John W. Payne (1985), "Effort and Accuracy in Choice, " Management Science, 31 (4), 395 -414. Payne, John W. , James R. Bettman, and Eric J. Johnson (1988), "Adaptive Strategy Selection in Decision Making, " Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory and Cognition, 14 (3), 534 -52. Shugan, Steven M. (1980), "The Cost of Thinking, " Journal of Consumer Research, 7 (2), 99 -111. Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker 8

Thinking about the Utility Function u($) ? $ Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker 9

Thinking about the Utility Function u($) ? $ Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker 9

Uncertainty Reveals Interesting Aspects about Choice - Lotteries Would you rather have a sure $10, 000 or a 50% shot at $20, 250? Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker 10

Uncertainty Reveals Interesting Aspects about Choice - Lotteries Would you rather have a sure $10, 000 or a 50% shot at $20, 250? Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker 10

The Utility Function Is Nonlinear Would you rather have a sure $10, 000 or a 50% shot at $20, 250? EV =. 5($20, 250) = $10, 125 q q q Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker We have to replace Expected Value with Expected Utility The function u is concave (u'' < 0) Consumers tend to be risk averse 11

The Utility Function Is Nonlinear Would you rather have a sure $10, 000 or a 50% shot at $20, 250? EV =. 5($20, 250) = $10, 125 q q q Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker We have to replace Expected Value with Expected Utility The function u is concave (u'' < 0) Consumers tend to be risk averse 11

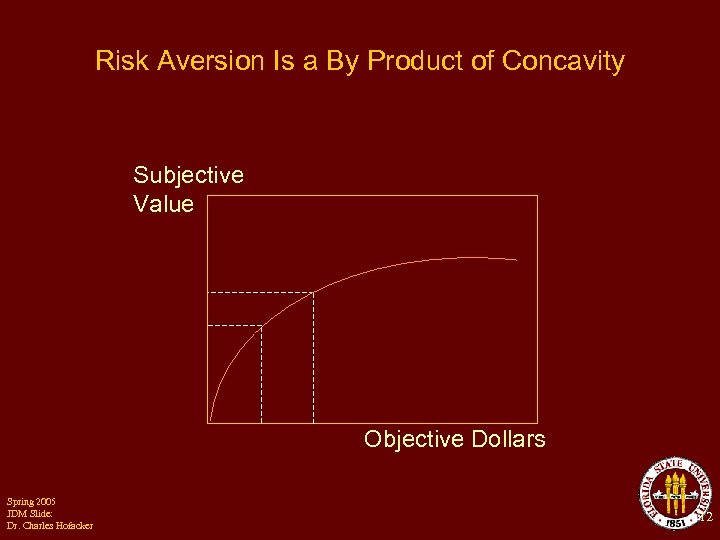

Risk Aversion Is a By Product of Concavity Subjective Value Objective Dollars Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker 12

Risk Aversion Is a By Product of Concavity Subjective Value Objective Dollars Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker 12

Uncertainty Reveals Interesting Aspects about Choice – the St. Petersburg Paradox How much would you pay to play a game in which a coin is tossed n times q q the coin is tossed until there is a Head you win $2 n The Expected Value of the game is infinite Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker 13

Uncertainty Reveals Interesting Aspects about Choice – the St. Petersburg Paradox How much would you pay to play a game in which a coin is tossed n times q q the coin is tossed until there is a Head you win $2 n The Expected Value of the game is infinite Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker 13

Using Lotteries to Establish the Utility of Money With probability p you win $50, 000 with probability 1 -p you lose $50, 000 EV(lottery) = p($50 k) + (1 -p)(-$50 k) Note that this lottery would be worth more than $30, 000 if p >. 8 Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker 14

Using Lotteries to Establish the Utility of Money With probability p you win $50, 000 with probability 1 -p you lose $50, 000 EV(lottery) = p($50 k) + (1 -p)(-$50 k) Note that this lottery would be worth more than $30, 000 if p >. 8 Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker 14

The Price of a Lottery Would you rather have $30, 000 or. 8 probability of winning $50, 000 and a. 2 probability of losing $50, 000? For most people, p must be closer to. 9. We look for a p which creates the indifference point Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker 15

The Price of a Lottery Would you rather have $30, 000 or. 8 probability of winning $50, 000 and a. 2 probability of losing $50, 000? For most people, p must be closer to. 9. We look for a p which creates the indifference point Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker 15

Creating the Utility Scale Arbitrarily set U(-$50, 000) = 0 U($50, 000) = 10 If the indifference point between the $30, 000 and the lottery is. 95, we have U(30, 000) = p · U($50, 000) + (1 -p) · U(-$50, 000) =. 95(10) +. 05(0) = 9. 5 We can vary the lottery buy-in price and use this method to establish the relationship between $ and U($). Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker 16

Creating the Utility Scale Arbitrarily set U(-$50, 000) = 0 U($50, 000) = 10 If the indifference point between the $30, 000 and the lottery is. 95, we have U(30, 000) = p · U($50, 000) + (1 -p) · U(-$50, 000) =. 95(10) +. 05(0) = 9. 5 We can vary the lottery buy-in price and use this method to establish the relationship between $ and U($). Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker 16

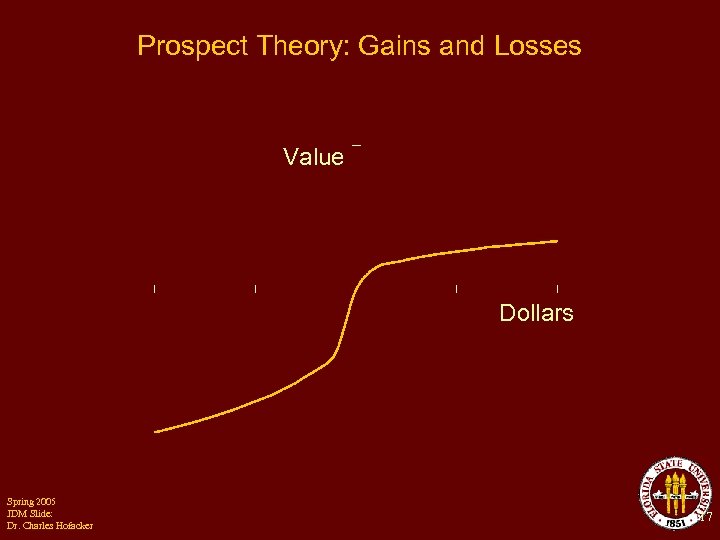

Prospect Theory: Gains and Losses Value Dollars Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker 17

Prospect Theory: Gains and Losses Value Dollars Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker 17

Prospect Theory q The disutility from a loss exceeds the utility from a comparatively sized gain q Differences, contrast or changes are more salient than absolute values (more on this later) Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker Kahneman, Daniel and Amos Tversky (1979), "Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk, " Econometrica, 47 (2), 263 -91. 18

Prospect Theory q The disutility from a loss exceeds the utility from a comparatively sized gain q Differences, contrast or changes are more salient than absolute values (more on this later) Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker Kahneman, Daniel and Amos Tversky (1979), "Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk, " Econometrica, 47 (2), 263 -91. 18

Loss Aversion The disutility of giving up a valued good is much higher than the utility gain associated with receiving the same good The endowment effect. A good’s utility appears to change when a good is incorporated into one’s endowment People don’t like to trade lottery tickets Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker 19

Loss Aversion The disutility of giving up a valued good is much higher than the utility gain associated with receiving the same good The endowment effect. A good’s utility appears to change when a good is incorporated into one’s endowment People don’t like to trade lottery tickets Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker 19

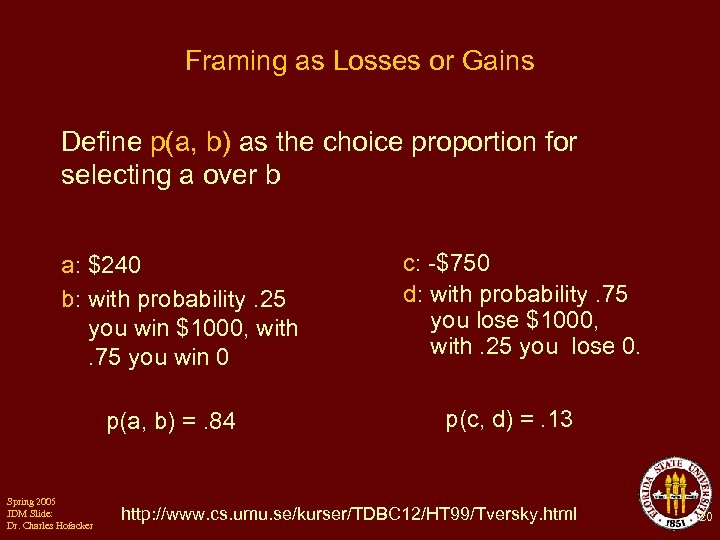

Framing as Losses or Gains Define p(a, b) as the choice proportion for selecting a over b a: $240 b: with probability. 25 you win $1000, with. 75 you win 0 p(a, b) =. 84 Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker c: -$750 d: with probability. 75 you lose $1000, with. 25 you lose 0. p(c, d) =. 13 http: //www. cs. umu. se/kurser/TDBC 12/HT 99/Tversky. html 20

Framing as Losses or Gains Define p(a, b) as the choice proportion for selecting a over b a: $240 b: with probability. 25 you win $1000, with. 75 you win 0 p(a, b) =. 84 Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker c: -$750 d: with probability. 75 you lose $1000, with. 25 you lose 0. p(c, d) =. 13 http: //www. cs. umu. se/kurser/TDBC 12/HT 99/Tversky. html 20

Imagine that the U. S. is preparing for the outbreak of a disease which is expected to kill 600 people. Two alternative programs to combat the disease have been proposed. Assume that the exact scientific estimates of the consequences of the programs are… Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker 21

Imagine that the U. S. is preparing for the outbreak of a disease which is expected to kill 600 people. Two alternative programs to combat the disease have been proposed. Assume that the exact scientific estimates of the consequences of the programs are… Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker 21

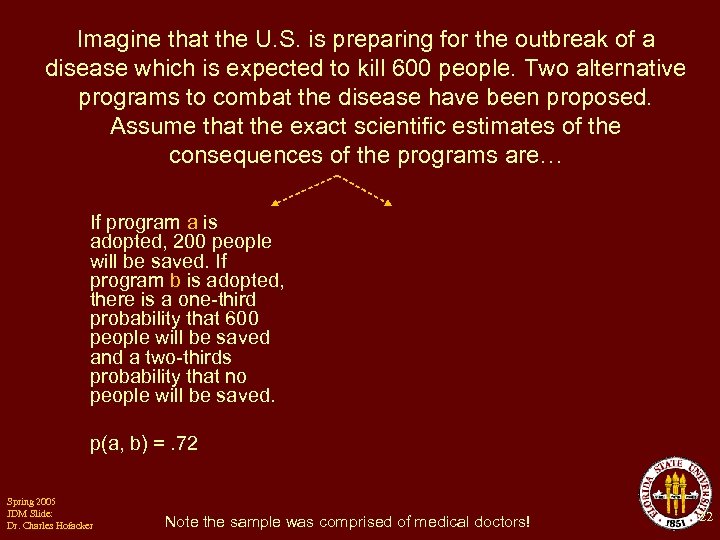

Imagine that the U. S. is preparing for the outbreak of a disease which is expected to kill 600 people. Two alternative programs to combat the disease have been proposed. Assume that the exact scientific estimates of the consequences of the programs are… If program a is adopted, 200 people will be saved. If program b is adopted, there is a one-third probability that 600 people will be saved and a two-thirds probability that no people will be saved. p(a, b) =. 72 Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker Note the sample was comprised of medical doctors! 22

Imagine that the U. S. is preparing for the outbreak of a disease which is expected to kill 600 people. Two alternative programs to combat the disease have been proposed. Assume that the exact scientific estimates of the consequences of the programs are… If program a is adopted, 200 people will be saved. If program b is adopted, there is a one-third probability that 600 people will be saved and a two-thirds probability that no people will be saved. p(a, b) =. 72 Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker Note the sample was comprised of medical doctors! 22

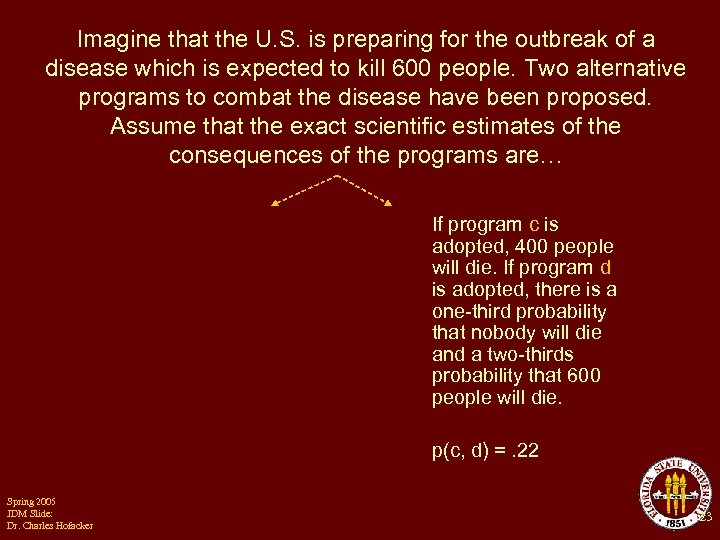

Imagine that the U. S. is preparing for the outbreak of a disease which is expected to kill 600 people. Two alternative programs to combat the disease have been proposed. Assume that the exact scientific estimates of the consequences of the programs are… If program c is adopted, 400 people will die. If program d is adopted, there is a one-third probability that nobody will die and a two-thirds probability that 600 people will die. p(c, d) =. 22 Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker 23

Imagine that the U. S. is preparing for the outbreak of a disease which is expected to kill 600 people. Two alternative programs to combat the disease have been proposed. Assume that the exact scientific estimates of the consequences of the programs are… If program c is adopted, 400 people will die. If program d is adopted, there is a one-third probability that nobody will die and a two-thirds probability that 600 people will die. p(c, d) =. 22 Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker 23

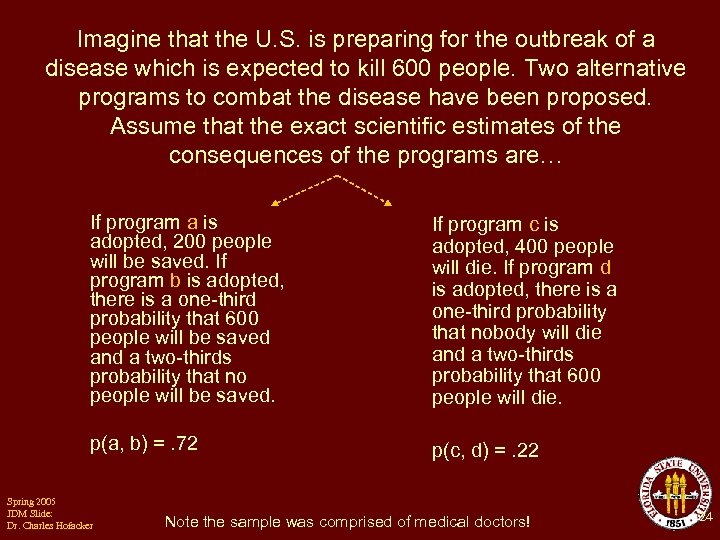

Imagine that the U. S. is preparing for the outbreak of a disease which is expected to kill 600 people. Two alternative programs to combat the disease have been proposed. Assume that the exact scientific estimates of the consequences of the programs are… If program a is adopted, 200 people will be saved. If program b is adopted, there is a one-third probability that 600 people will be saved and a two-thirds probability that no people will be saved. If program c is adopted, 400 people will die. If program d is adopted, there is a one-third probability that nobody will die and a two-thirds probability that 600 people will die. p(a, b) =. 72 p(c, d) =. 22 Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker Note the sample was comprised of medical doctors! 24

Imagine that the U. S. is preparing for the outbreak of a disease which is expected to kill 600 people. Two alternative programs to combat the disease have been proposed. Assume that the exact scientific estimates of the consequences of the programs are… If program a is adopted, 200 people will be saved. If program b is adopted, there is a one-third probability that 600 people will be saved and a two-thirds probability that no people will be saved. If program c is adopted, 400 people will die. If program d is adopted, there is a one-third probability that nobody will die and a two-thirds probability that 600 people will die. p(a, b) =. 72 p(c, d) =. 22 Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker Note the sample was comprised of medical doctors! 24

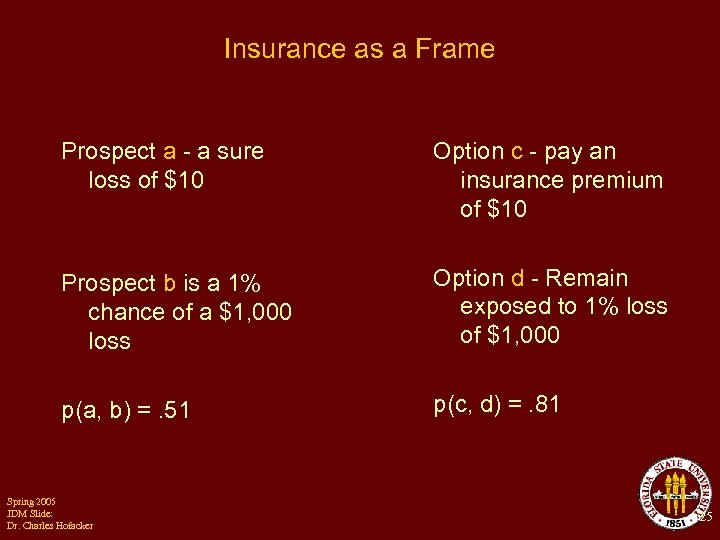

Insurance as a Frame Prospect a - a sure loss of $10 Option c - pay an insurance premium of $10 Prospect b is a 1% chance of a $1, 000 loss Option d - Remain exposed to 1% loss of $1, 000 p(a, b) =. 51 p(c, d) =. 81 Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker 25

Insurance as a Frame Prospect a - a sure loss of $10 Option c - pay an insurance premium of $10 Prospect b is a 1% chance of a $1, 000 loss Option d - Remain exposed to 1% loss of $1, 000 p(a, b) =. 51 p(c, d) =. 81 Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker 25

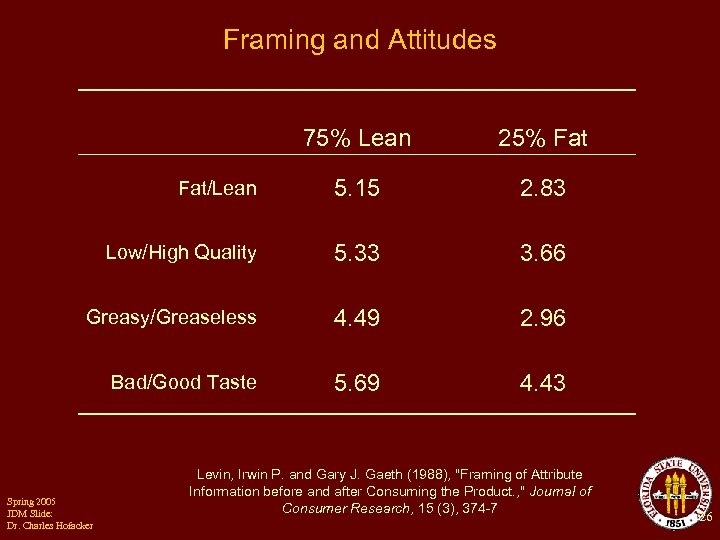

Framing and Attitudes 75% Lean 25% Fat/Lean 5. 15 2. 83 Low/High Quality 5. 33 3. 66 Greasy/Greaseless 4. 49 2. 96 Bad/Good Taste 5. 69 4. 43 Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker Levin, Irwin P. and Gary J. Gaeth (1988), "Framing of Attribute Information before and after Consuming the Product. , " Journal of Consumer Research, 15 (3), 374 -7 26

Framing and Attitudes 75% Lean 25% Fat/Lean 5. 15 2. 83 Low/High Quality 5. 33 3. 66 Greasy/Greaseless 4. 49 2. 96 Bad/Good Taste 5. 69 4. 43 Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker Levin, Irwin P. and Gary J. Gaeth (1988), "Framing of Attribute Information before and after Consuming the Product. , " Journal of Consumer Research, 15 (3), 374 -7 26

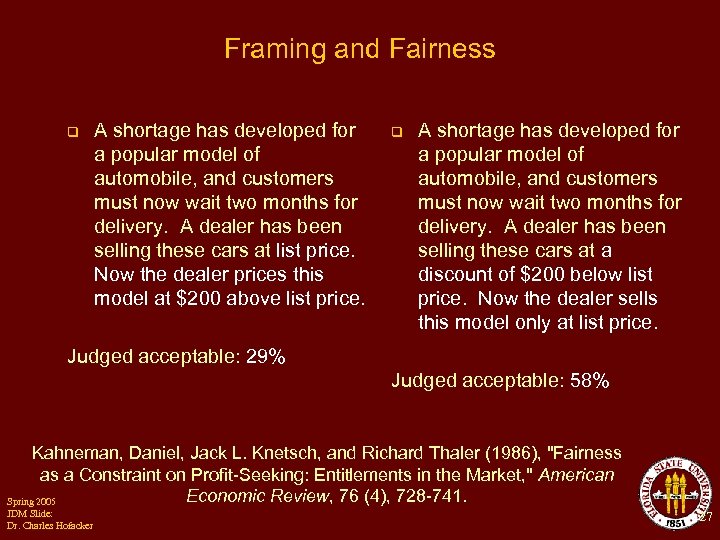

Framing and Fairness q A shortage has developed for a popular model of automobile, and customers must now wait two months for delivery. A dealer has been selling these cars at list price. Now the dealer prices this model at $200 above list price. q A shortage has developed for a popular model of automobile, and customers must now wait two months for delivery. A dealer has been selling these cars at a discount of $200 below list price. Now the dealer sells this model only at list price. Judged acceptable: 29% Judged acceptable: 58% Kahneman, Daniel, Jack L. Knetsch, and Richard Thaler (1986), "Fairness as a Constraint on Profit-Seeking: Entitlements in the Market, " American Economic Review, 76 (4), 728 -741. Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker 27

Framing and Fairness q A shortage has developed for a popular model of automobile, and customers must now wait two months for delivery. A dealer has been selling these cars at list price. Now the dealer prices this model at $200 above list price. q A shortage has developed for a popular model of automobile, and customers must now wait two months for delivery. A dealer has been selling these cars at a discount of $200 below list price. Now the dealer sells this model only at list price. Judged acceptable: 29% Judged acceptable: 58% Kahneman, Daniel, Jack L. Knetsch, and Richard Thaler (1986), "Fairness as a Constraint on Profit-Seeking: Entitlements in the Market, " American Economic Review, 76 (4), 728 -741. Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker 27

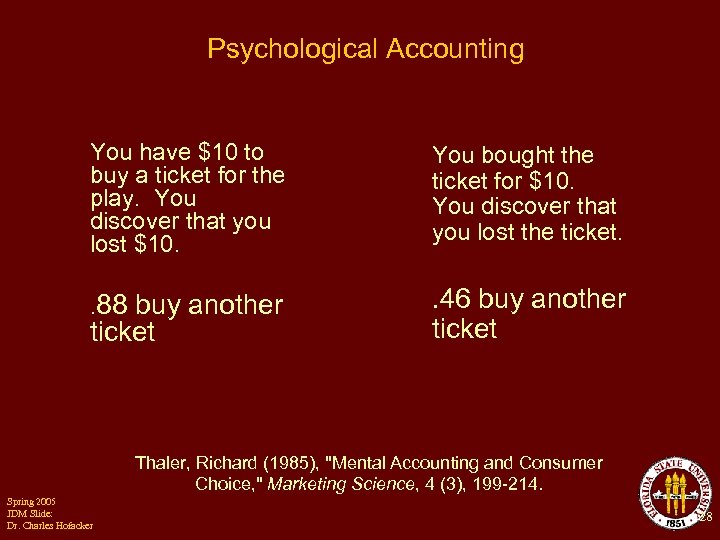

Psychological Accounting You have $10 to buy a ticket for the play. You discover that you lost $10. You bought the ticket for $10. You discover that you lost the ticket. . 88 buy another . 46 buy another ticket Thaler, Richard (1985), "Mental Accounting and Consumer Choice, " Marketing Science, 4 (3), 199 -214. Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker 28

Psychological Accounting You have $10 to buy a ticket for the play. You discover that you lost $10. You bought the ticket for $10. You discover that you lost the ticket. . 88 buy another . 46 buy another ticket Thaler, Richard (1985), "Mental Accounting and Consumer Choice, " Marketing Science, 4 (3), 199 -214. Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker 28

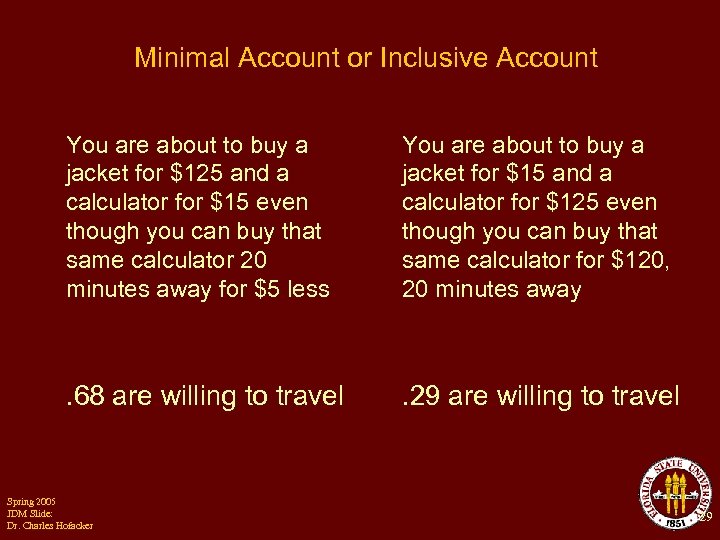

Minimal Account or Inclusive Account You are about to buy a jacket for $125 and a calculator for $15 even though you can buy that same calculator 20 minutes away for $5 less You are about to buy a jacket for $15 and a calculator for $125 even though you can buy that same calculator for $120, 20 minutes away . 68 are willing to travel . 29 are willing to travel Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker 29

Minimal Account or Inclusive Account You are about to buy a jacket for $125 and a calculator for $15 even though you can buy that same calculator 20 minutes away for $5 less You are about to buy a jacket for $15 and a calculator for $125 even though you can buy that same calculator for $120, 20 minutes away . 68 are willing to travel . 29 are willing to travel Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker 29

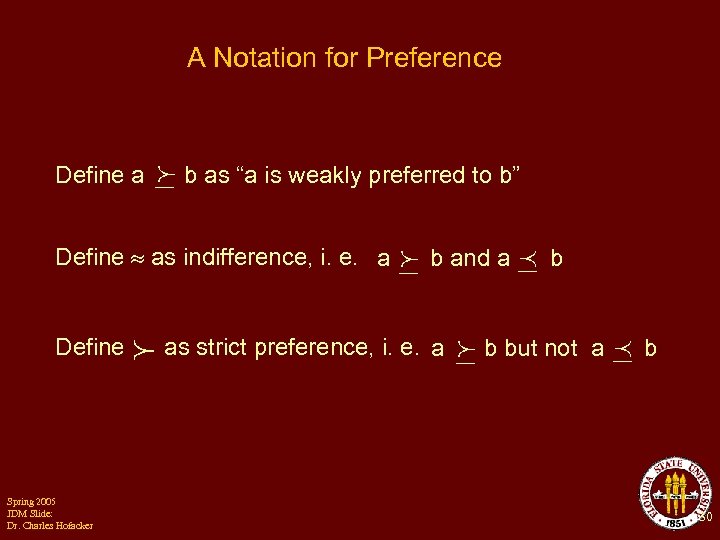

A Notation for Preference Define a b as “a is weakly preferred to b” Define as indifference, i. e. a Define Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker b and a as strict preference, i. e. a b b but not a b 30

A Notation for Preference Define a b as “a is weakly preferred to b” Define as indifference, i. e. a Define Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker b and a as strict preference, i. e. a b b but not a b 30

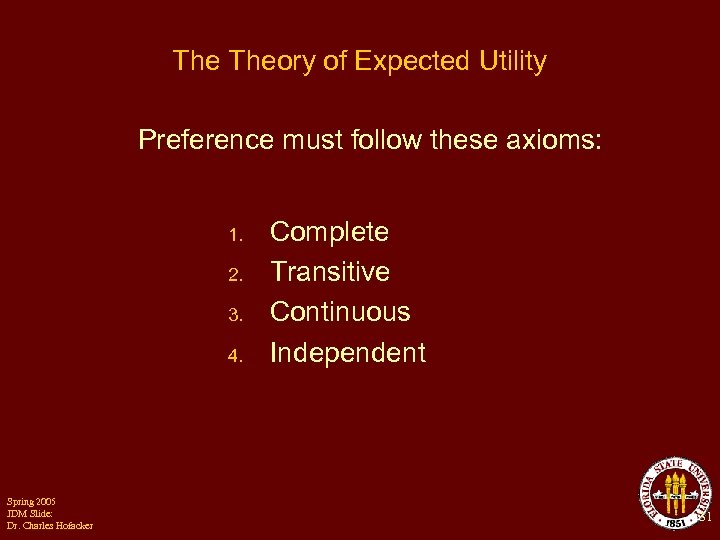

The Theory of Expected Utility Preference must follow these axioms: 1. 2. 3. 4. Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker Complete Transitive Continuous Independent 31

The Theory of Expected Utility Preference must follow these axioms: 1. 2. 3. 4. Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker Complete Transitive Continuous Independent 31

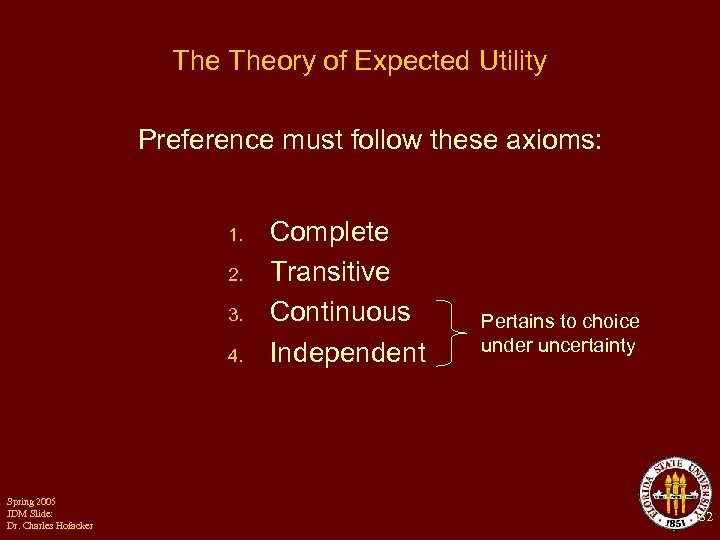

The Theory of Expected Utility Preference must follow these axioms: 1. 2. 3. 4. Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker Complete Transitive Continuous Independent Pertains to choice under uncertainty 32

The Theory of Expected Utility Preference must follow these axioms: 1. 2. 3. 4. Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker Complete Transitive Continuous Independent Pertains to choice under uncertainty 32

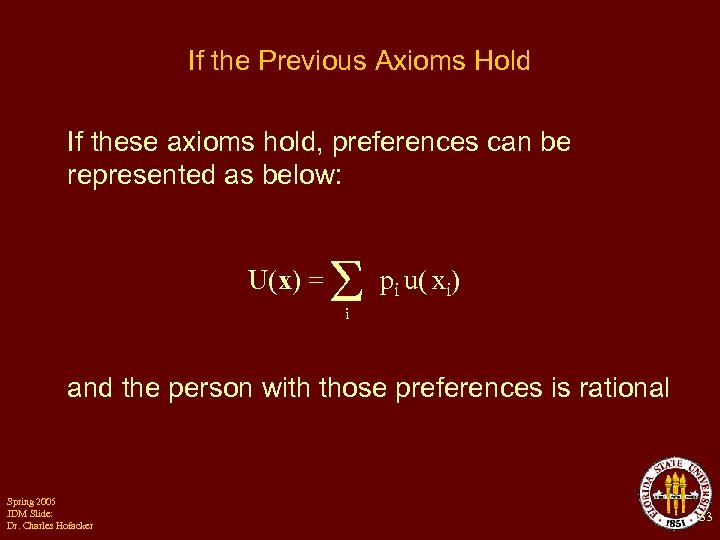

If the Previous Axioms Hold If these axioms hold, preferences can be represented as below: U(x) = p u( x ) i i i and the person with those preferences is rational Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker 33

If the Previous Axioms Hold If these axioms hold, preferences can be represented as below: U(x) = p u( x ) i i i and the person with those preferences is rational Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker 33

Completeness A preference relation is complete if for all a and b we have a b or both. Thus q The consumer is able to form an opinion about the relative merit of any pair of bundles q The consumer has well defined preferences between any pair of bundles Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker 34

Completeness A preference relation is complete if for all a and b we have a b or both. Thus q The consumer is able to form an opinion about the relative merit of any pair of bundles q The consumer has well defined preferences between any pair of bundles Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker 34

Choice Tends Be Constructed Not Revealed q Choosing is ad hoc and done on the spot q Differences, contrast or changes are more salient than absolute values q The choice process depends on contextual and situational factors Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker Bettman, James R. , Mary Frances Luce, and John W. Payne (1998), "Constructive Consumer Choice Processes, " Journal of Consumer Research, 25(3), 187 -217. 35

Choice Tends Be Constructed Not Revealed q Choosing is ad hoc and done on the spot q Differences, contrast or changes are more salient than absolute values q The choice process depends on contextual and situational factors Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker Bettman, James R. , Mary Frances Luce, and John W. Payne (1998), "Constructive Consumer Choice Processes, " Journal of Consumer Research, 25(3), 187 -217. 35

Assimilation and Contrast Assimilation - Consumers adjust their evaluation of an unfamiliar option in the direction of a context of familiar options Contrast – Consumers adjust their evaluation of an unfamiliar option in the direction opposite from a context of familiar options Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker Cooke, Alan D. J. , Harish Sujan, Mita Sujan, and Barton A. Weitz (2002), "Marketing the Unfamiliar: The Role of Context and Item-Specific Information in Electronic Agent Recommendations, " Journal of Marketing Research, 39 (4), 488 -97. 36

Assimilation and Contrast Assimilation - Consumers adjust their evaluation of an unfamiliar option in the direction of a context of familiar options Contrast – Consumers adjust their evaluation of an unfamiliar option in the direction opposite from a context of familiar options Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker Cooke, Alan D. J. , Harish Sujan, Mita Sujan, and Barton A. Weitz (2002), "Marketing the Unfamiliar: The Role of Context and Item-Specific Information in Electronic Agent Recommendations, " Journal of Marketing Research, 39 (4), 488 -97. 36

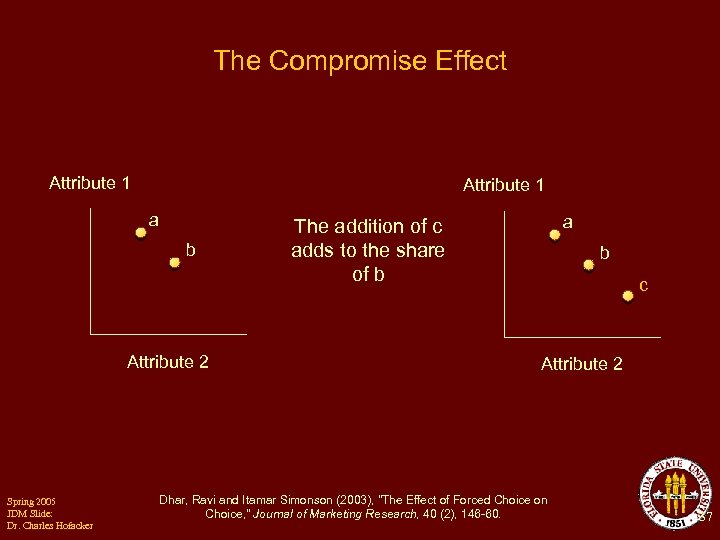

The Compromise Effect Attribute 1 a b Attribute 2 Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker a The addition of c adds to the share of b b c Attribute 2 Dhar, Ravi and Itamar Simonson (2003), "The Effect of Forced Choice on Choice, " Journal of Marketing Research, 40 (2), 146 -60. 37

The Compromise Effect Attribute 1 a b Attribute 2 Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker a The addition of c adds to the share of b b c Attribute 2 Dhar, Ravi and Itamar Simonson (2003), "The Effect of Forced Choice on Choice, " Journal of Marketing Research, 40 (2), 146 -60. 37

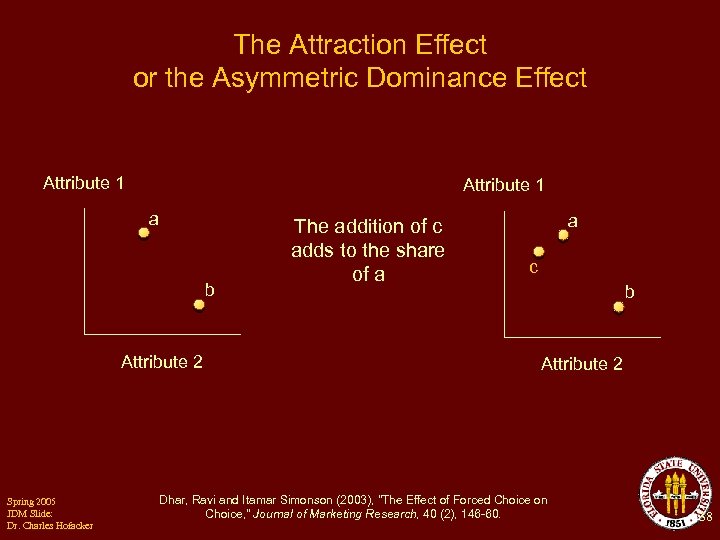

The Attraction Effect or the Asymmetric Dominance Effect Attribute 1 a b Attribute 2 Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker The addition of c adds to the share of a a c b Attribute 2 Dhar, Ravi and Itamar Simonson (2003), "The Effect of Forced Choice on Choice, " Journal of Marketing Research, 40 (2), 146 -60. 38

The Attraction Effect or the Asymmetric Dominance Effect Attribute 1 a b Attribute 2 Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker The addition of c adds to the share of a a c b Attribute 2 Dhar, Ravi and Itamar Simonson (2003), "The Effect of Forced Choice on Choice, " Journal of Marketing Research, 40 (2), 146 -60. 38

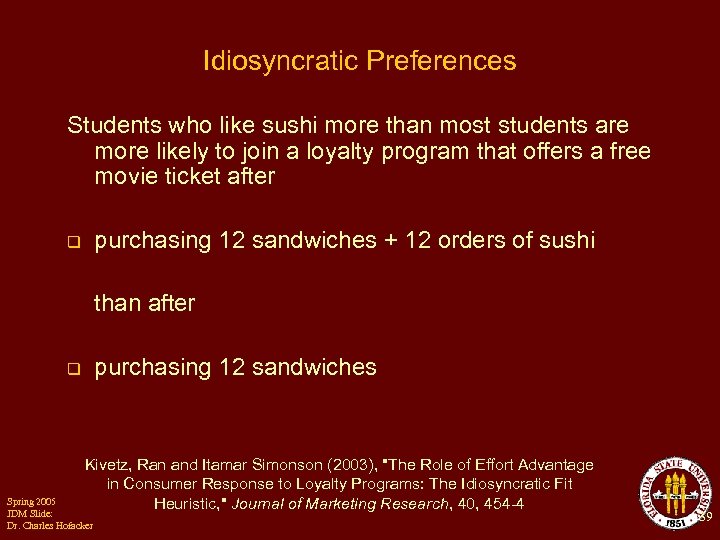

Idiosyncratic Preferences Students who like sushi more than most students are more likely to join a loyalty program that offers a free movie ticket after purchasing 12 sandwiches + 12 orders of sushi q than after purchasing 12 sandwiches q Kivetz, Ran and Itamar Simonson (2003), "The Role of Effort Advantage in Consumer Response to Loyalty Programs: The Idiosyncratic Fit Heuristic, " Journal of Marketing Research, 40, 454 -4 Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker 39

Idiosyncratic Preferences Students who like sushi more than most students are more likely to join a loyalty program that offers a free movie ticket after purchasing 12 sandwiches + 12 orders of sushi q than after purchasing 12 sandwiches q Kivetz, Ran and Itamar Simonson (2003), "The Role of Effort Advantage in Consumer Response to Loyalty Programs: The Idiosyncratic Fit Heuristic, " Journal of Marketing Research, 40, 454 -4 Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker 39

Transitivity a Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker b c 40

Transitivity a Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker b c 40

Definition of Transitivity if a then a Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker b and b c, c 41

Definition of Transitivity if a then a Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker b and b c, c 41

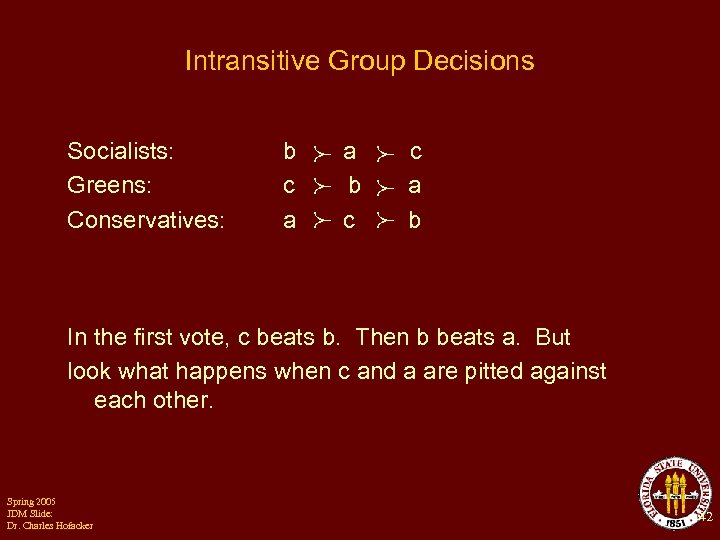

Intransitive Group Decisions Socialists: Greens: Conservatives: b c a a b c c a b In the first vote, c beats b. Then b beats a. But look what happens when c and a are pitted against each other. Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker 42

Intransitive Group Decisions Socialists: Greens: Conservatives: b c a a b c c a b In the first vote, c beats b. Then b beats a. But look what happens when c and a are pitted against each other. Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker 42

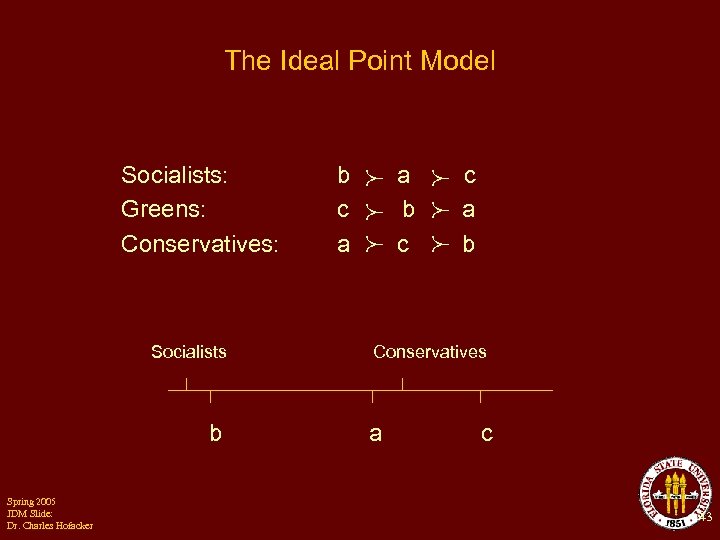

The Ideal Point Model Socialists: Greens: Conservatives: Socialists b Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker b c a a b c c a b Conservatives a c 43

The Ideal Point Model Socialists: Greens: Conservatives: Socialists b Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker b c a a b c c a b Conservatives a c 43

Weak Stochastic Transitivity if p(a, b) . 5 and p(b, c) . 5 then p(a, c) . 5 Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker 44

Weak Stochastic Transitivity if p(a, b) . 5 and p(b, c) . 5 then p(a, c) . 5 Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker 44

Continuity For a b c, there must exist a unique p s. t. p · a + (1 – p) · c b Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker 45

Continuity For a b c, there must exist a unique p s. t. p · a + (1 – p) · c b Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker 45

Independence If a b, then p · a + (1 – p) · c Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker p · b + (1 – p) · c 46

Independence If a b, then p · a + (1 – p) · c Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker p · b + (1 – p) · c 46

Another Way to Express Independence For four choice options a, b, c and d p(a, b) > p(c, b) iff p(a, d) > p(c, d) This is equivalent to Tversky & Kahneman’s (1986) cancellation Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker 47

Another Way to Express Independence For four choice options a, b, c and d p(a, b) > p(c, b) iff p(a, d) > p(c, d) This is equivalent to Tversky & Kahneman’s (1986) cancellation Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker 47

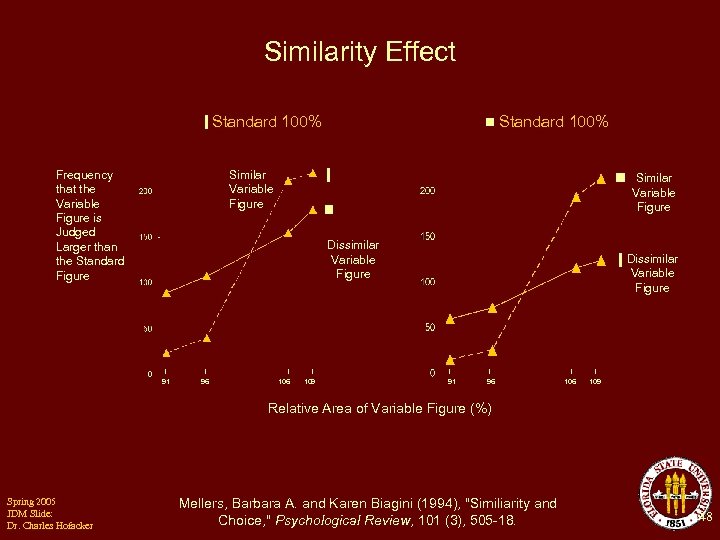

Similarity Effect Standard 100% Frequency that the Variable Figure is Judged Larger than the Standard Figure Standard 100% Similar Variable Figure Dissimilar Variable Figure 91 96 106 109 Relative Area of Variable Figure (%) Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker Mellers, Barbara A. and Karen Biagini (1994), "Similiarity and Choice, " Psychological Review, 101 (3), 505 -18. 48

Similarity Effect Standard 100% Frequency that the Variable Figure is Judged Larger than the Standard Figure Standard 100% Similar Variable Figure Dissimilar Variable Figure 91 96 106 109 Relative Area of Variable Figure (%) Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker Mellers, Barbara A. and Karen Biagini (1994), "Similiarity and Choice, " Psychological Review, 101 (3), 505 -18. 48

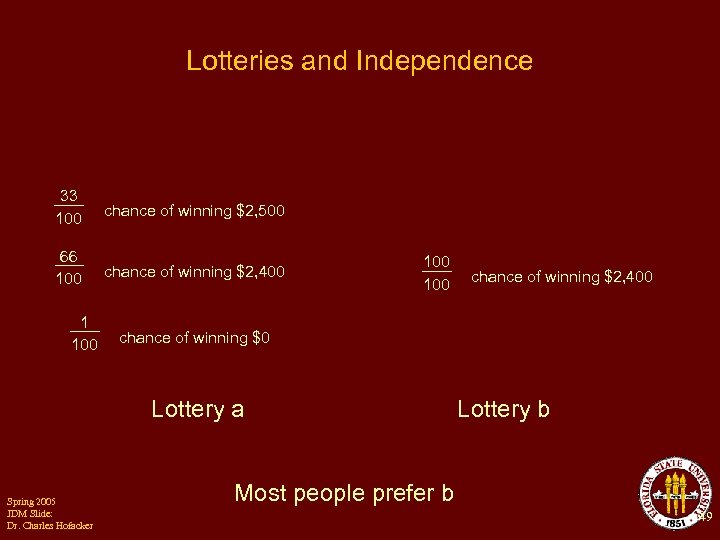

Lotteries and Independence 33 100 chance of winning $2, 500 66 100 chance of winning $2, 400 1 100 100 chance of winning $0 Lottery a Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker chance of winning $2, 400 Lottery b Most people prefer b 49

Lotteries and Independence 33 100 chance of winning $2, 500 66 100 chance of winning $2, 400 1 100 100 chance of winning $0 Lottery a Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker chance of winning $2, 400 Lottery b Most people prefer b 49

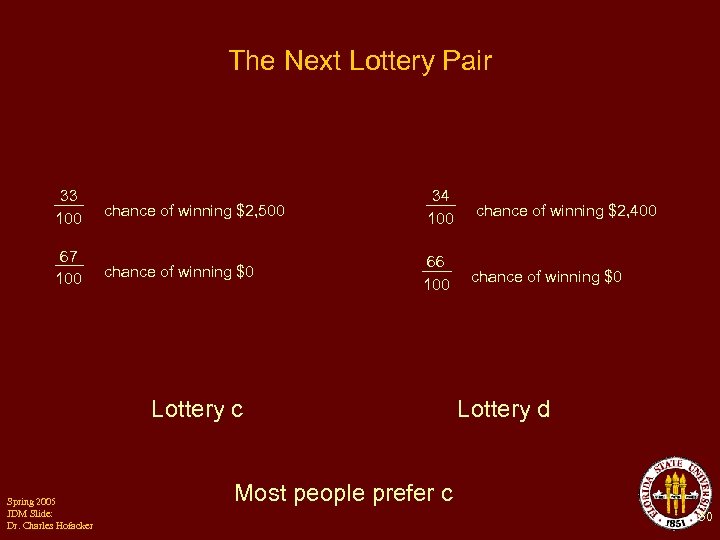

The Next Lottery Pair 33 100 67 100 chance of winning $2, 500 34 100 chance of winning $2, 400 chance of winning $0 66 100 chance of winning $0 Lottery c Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker Lottery d Most people prefer c 50

The Next Lottery Pair 33 100 67 100 chance of winning $2, 500 34 100 chance of winning $2, 400 chance of winning $0 66 100 chance of winning $0 Lottery c Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker Lottery d Most people prefer c 50

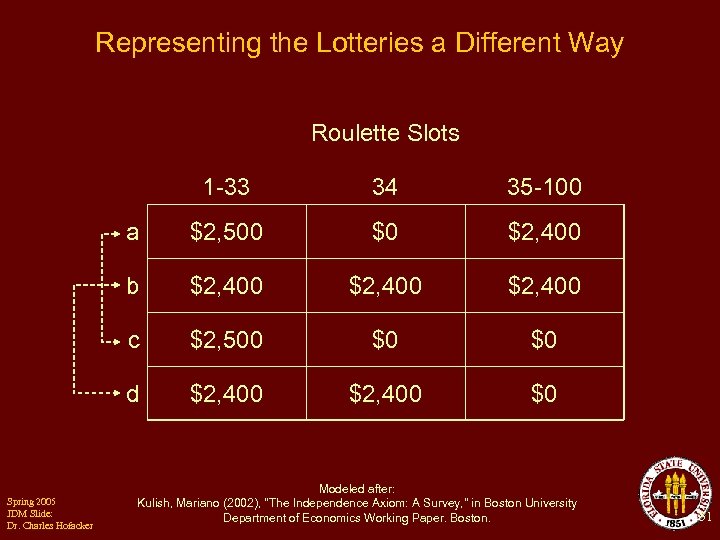

Representing the Lotteries a Different Way Roulette Slots 1 -33 35 -100 a $2, 500 $0 $2, 400 b $2, 400 c $2, 500 $0 $0 d Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker 34 $2, 400 $0 Modeled after: Kulish, Mariano (2002), "The Independence Axiom: A Survey, " in Boston University Department of Economics Working Paper. Boston. 51

Representing the Lotteries a Different Way Roulette Slots 1 -33 35 -100 a $2, 500 $0 $2, 400 b $2, 400 c $2, 500 $0 $0 d Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker 34 $2, 400 $0 Modeled after: Kulish, Mariano (2002), "The Independence Axiom: A Survey, " in Boston University Department of Economics Working Paper. Boston. 51

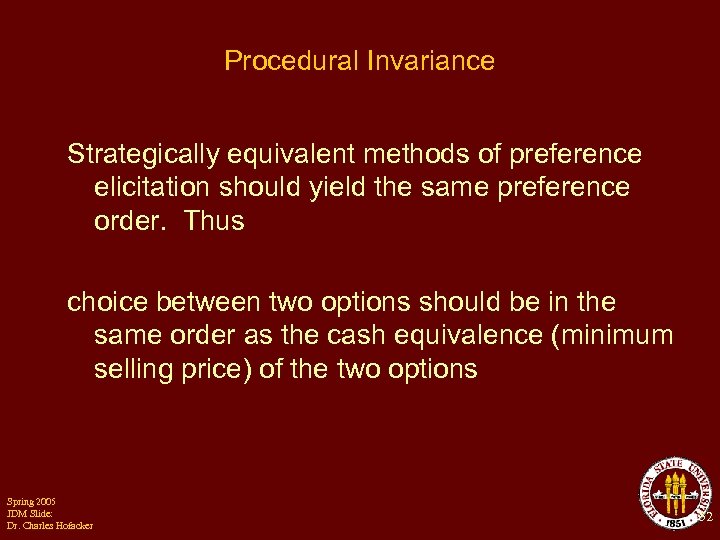

Procedural Invariance Strategically equivalent methods of preference elicitation should yield the same preference order. Thus choice between two options should be in the same order as the cash equivalence (minimum selling price) of the two options Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker 52

Procedural Invariance Strategically equivalent methods of preference elicitation should yield the same preference order. Thus choice between two options should be in the same order as the cash equivalence (minimum selling price) of the two options Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker 52

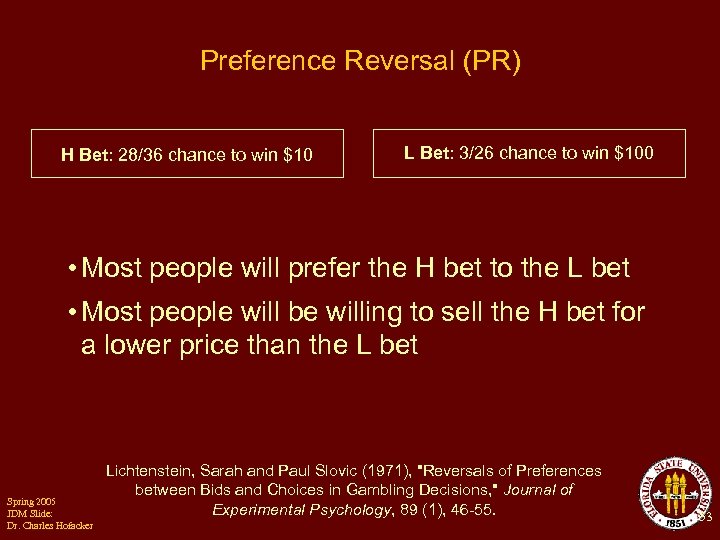

Preference Reversal (PR) H Bet: 28/36 chance to win $10 L Bet: 3/26 chance to win $100 • Most people will prefer the H bet to the L bet • Most people will be willing to sell the H bet for a lower price than the L bet Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker Lichtenstein, Sarah and Paul Slovic (1971), "Reversals of Preferences between Bids and Choices in Gambling Decisions, " Journal of Experimental Psychology, 89 (1), 46 -55. 53

Preference Reversal (PR) H Bet: 28/36 chance to win $10 L Bet: 3/26 chance to win $100 • Most people will prefer the H bet to the L bet • Most people will be willing to sell the H bet for a lower price than the L bet Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker Lichtenstein, Sarah and Paul Slovic (1971), "Reversals of Preferences between Bids and Choices in Gambling Decisions, " Journal of Experimental Psychology, 89 (1), 46 -55. 53

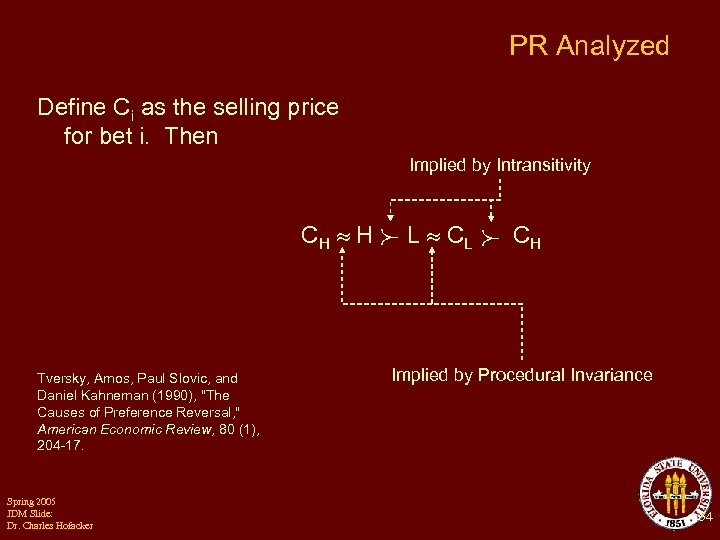

PR Analyzed Define Ci as the selling price for bet i. Then Implied by Intransitivity CH H Tversky, Amos, Paul Slovic, and Daniel Kahneman (1990), "The Causes of Preference Reversal, " American Economic Review, 80 (1), 204 -17. Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker L CL CH Implied by Procedural Invariance 54

PR Analyzed Define Ci as the selling price for bet i. Then Implied by Intransitivity CH H Tversky, Amos, Paul Slovic, and Daniel Kahneman (1990), "The Causes of Preference Reversal, " American Economic Review, 80 (1), 204 -17. Spring 2005 JDM Slide: Dr. Charles Hofacker L CL CH Implied by Procedural Invariance 54