3824b320b30a3a9e8f9d56db8b622a49.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 37

Computers for the Post-PC Era David Patterson University of California at Berkeley Patterson@cs. berkeley. edu UC Berkeley IRAM Group UC Berkeley ISTORE Group istore-group@cs. berkeley. edu May 2000 Slide 1

Computers for the Post-PC Era David Patterson University of California at Berkeley Patterson@cs. berkeley. edu UC Berkeley IRAM Group UC Berkeley ISTORE Group istore-group@cs. berkeley. edu May 2000 Slide 1

Perspective on Post-PC Era • Post. PC Era will be driven by 2 technologies: 1) “Gadgets”: Tiny Embedded or Mobile Devices – ubiquitous: in everything – e. g. , successor to PDA, cell phone, wearable computers 2) Infrastructure to Support such Devices – e. g. , successor to Big Fat Web Servers, Database Servers Slide 2

Perspective on Post-PC Era • Post. PC Era will be driven by 2 technologies: 1) “Gadgets”: Tiny Embedded or Mobile Devices – ubiquitous: in everything – e. g. , successor to PDA, cell phone, wearable computers 2) Infrastructure to Support such Devices – e. g. , successor to Big Fat Web Servers, Database Servers Slide 2

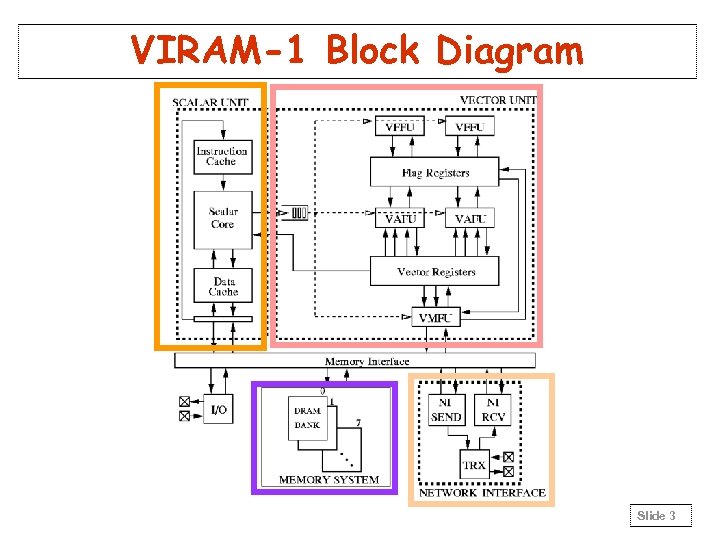

VIRAM-1 Block Diagram Slide 3

VIRAM-1 Block Diagram Slide 3

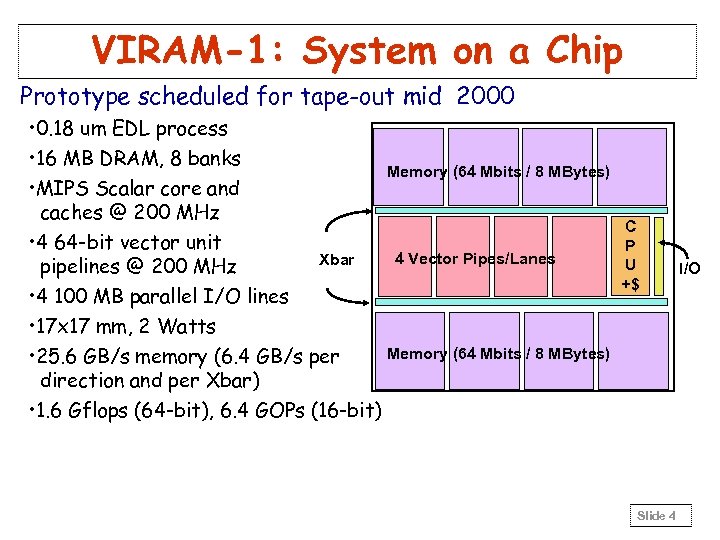

VIRAM-1: System on a Chip Prototype scheduled for tape-out mid 2000 • 0. 18 um EDL process • 16 MB DRAM, 8 banks Memory (64 Mbits / 8 MBytes) • MIPS Scalar core and caches @ 200 MHz • 4 64 -bit vector unit 4 Vector Pipes/Lanes Xbar pipelines @ 200 MHz • 4 100 MB parallel I/O lines • 17 x 17 mm, 2 Watts Memory (64 Mbits / 8 MBytes) • 25. 6 GB/s memory (6. 4 GB/s per direction and per Xbar) • 1. 6 Gflops (64 -bit), 6. 4 GOPs (16 -bit) C P U +$ Slide 4 I/O

VIRAM-1: System on a Chip Prototype scheduled for tape-out mid 2000 • 0. 18 um EDL process • 16 MB DRAM, 8 banks Memory (64 Mbits / 8 MBytes) • MIPS Scalar core and caches @ 200 MHz • 4 64 -bit vector unit 4 Vector Pipes/Lanes Xbar pipelines @ 200 MHz • 4 100 MB parallel I/O lines • 17 x 17 mm, 2 Watts Memory (64 Mbits / 8 MBytes) • 25. 6 GB/s memory (6. 4 GB/s per direction and per Xbar) • 1. 6 Gflops (64 -bit), 6. 4 GOPs (16 -bit) C P U +$ Slide 4 I/O

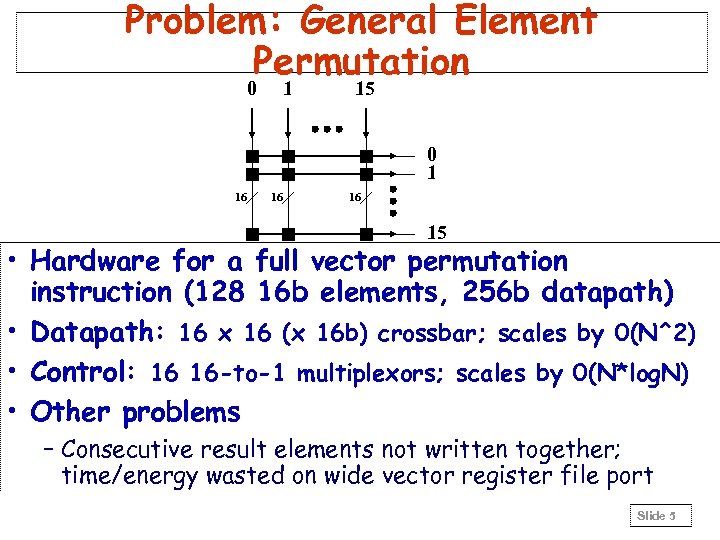

Problem: General Element Permutation 0 1 15 0 1 16 16 16 15 • Hardware for a full vector permutation instruction (128 16 b elements, 256 b datapath) • Datapath: 16 x 16 (x 16 b) crossbar; scales by 0(N^2) • Control: 16 16 -to-1 multiplexors; scales by 0(N*log. N) • Other problems – Consecutive result elements not written together; time/energy wasted on wide vector register file port Slide 5

Problem: General Element Permutation 0 1 15 0 1 16 16 16 15 • Hardware for a full vector permutation instruction (128 16 b elements, 256 b datapath) • Datapath: 16 x 16 (x 16 b) crossbar; scales by 0(N^2) • Control: 16 16 -to-1 multiplexors; scales by 0(N*log. N) • Other problems – Consecutive result elements not written together; time/energy wasted on wide vector register file port Slide 5

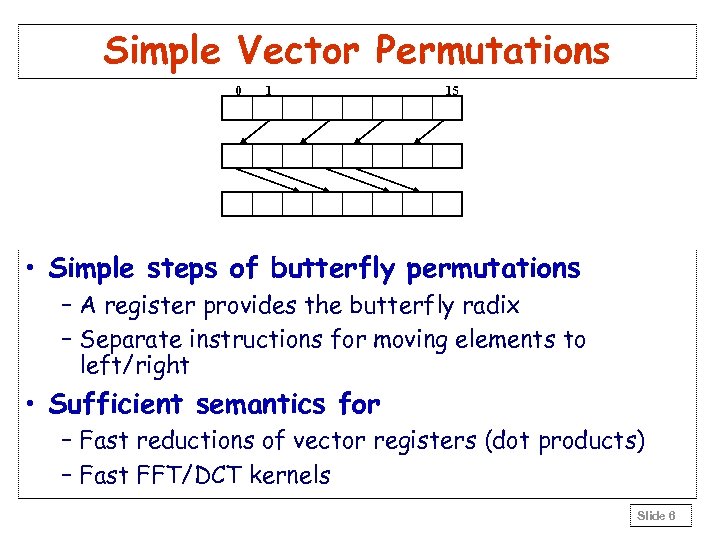

Simple Vector Permutations 0 1 15 • Simple steps of butterfly permutations – A register provides the butterfly radix – Separate instructions for moving elements to left/right • Sufficient semantics for – Fast reductions of vector registers (dot products) – Fast FFT/DCT kernels Slide 6

Simple Vector Permutations 0 1 15 • Simple steps of butterfly permutations – A register provides the butterfly radix – Separate instructions for moving elements to left/right • Sufficient semantics for – Fast reductions of vector registers (dot products) – Fast FFT/DCT kernels Slide 6

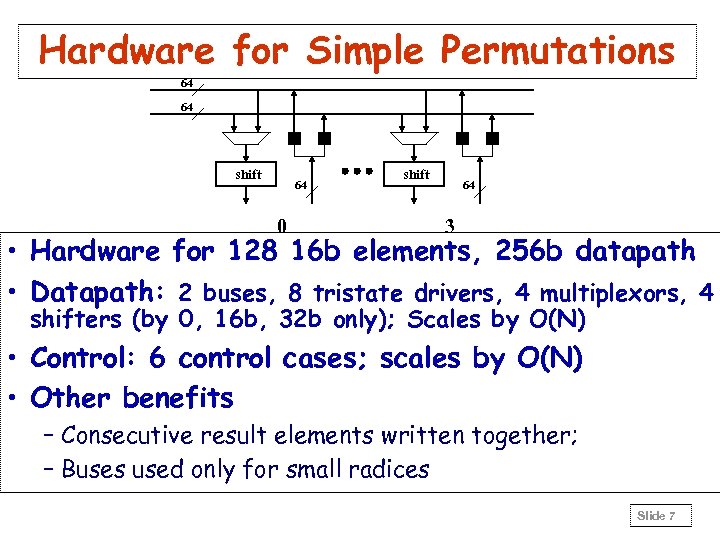

Hardware for Simple Permutations 64 64 shift 64 0 shift 64 3 • Hardware for 128 16 b elements, 256 b datapath • Datapath: 2 buses, 8 tristate drivers, 4 multiplexors, 4 shifters (by 0, 16 b, 32 b only); Scales by O(N) • Control: 6 control cases; scales by O(N) • Other benefits – Consecutive result elements written together; – Buses used only for small radices Slide 7

Hardware for Simple Permutations 64 64 shift 64 0 shift 64 3 • Hardware for 128 16 b elements, 256 b datapath • Datapath: 2 buses, 8 tristate drivers, 4 multiplexors, 4 shifters (by 0, 16 b, 32 b only); Scales by O(N) • Control: 6 control cases; scales by O(N) • Other benefits – Consecutive result elements written together; – Buses used only for small radices Slide 7

FFT: Straight forward Problem: most time spent in short vectors in later stages of FFT Slide 8

FFT: Straight forward Problem: most time spent in short vectors in later stages of FFT Slide 8

FFT: Transpose inside Vector Regs Slide 9

FFT: Transpose inside Vector Regs Slide 9

FFT: Straight forward Slide 10

FFT: Straight forward Slide 10

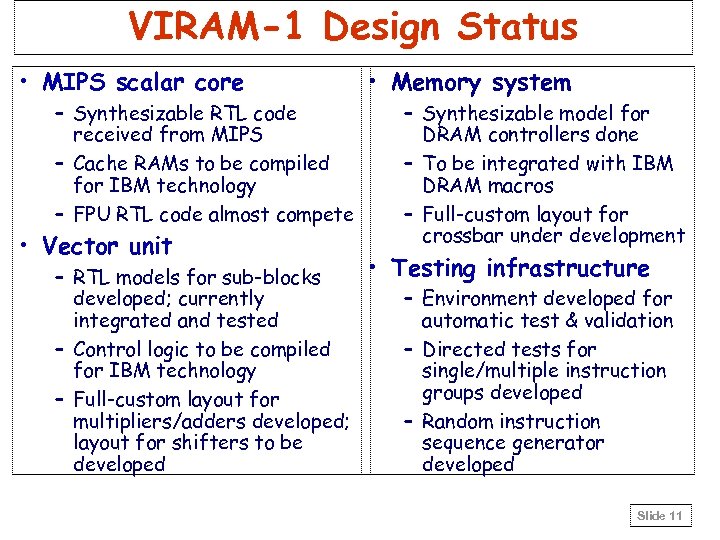

VIRAM-1 Design Status • MIPS scalar core – Synthesizable RTL code received from MIPS – Cache RAMs to be compiled for IBM technology – FPU RTL code almost compete • Vector unit • Memory system – Synthesizable model for DRAM controllers done – To be integrated with IBM DRAM macros – Full-custom layout for crossbar under development • Testing infrastructure – RTL models for sub-blocks developed; currently – Environment developed for integrated and tested automatic test & validation – Control logic to be compiled – Directed tests for IBM technology single/multiple instruction groups developed – Full-custom layout for multipliers/adders developed; – Random instruction layout for shifters to be sequence generator developed Slide 11

VIRAM-1 Design Status • MIPS scalar core – Synthesizable RTL code received from MIPS – Cache RAMs to be compiled for IBM technology – FPU RTL code almost compete • Vector unit • Memory system – Synthesizable model for DRAM controllers done – To be integrated with IBM DRAM macros – Full-custom layout for crossbar under development • Testing infrastructure – RTL models for sub-blocks developed; currently – Environment developed for integrated and tested automatic test & validation – Control logic to be compiled – Directed tests for IBM technology single/multiple instruction groups developed – Full-custom layout for multipliers/adders developed; – Random instruction layout for shifters to be sequence generator developed Slide 11

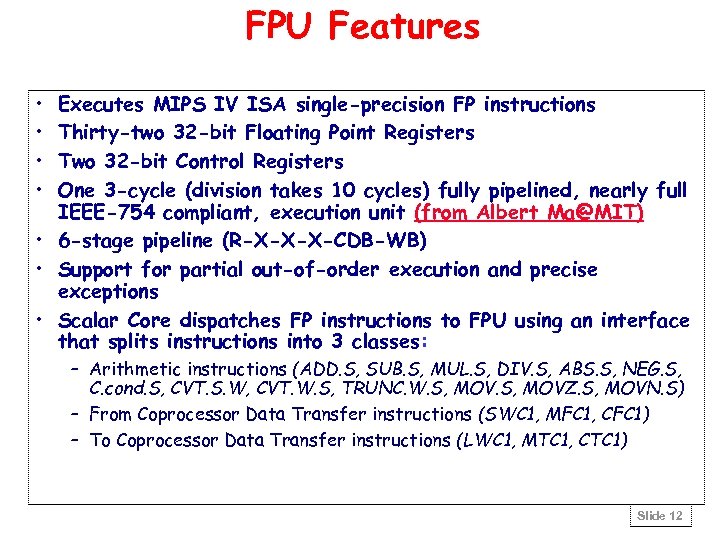

FPU Features • • Executes MIPS IV ISA single-precision FP instructions Thirty-two 32 -bit Floating Point Registers Two 32 -bit Control Registers One 3 -cycle (division takes 10 cycles) fully pipelined, nearly full IEEE-754 compliant, execution unit (from Albert Ma@MIT) • 6 -stage pipeline (R-X-X-X-CDB-WB) • Support for partial out-of-order execution and precise exceptions • Scalar Core dispatches FP instructions to FPU using an interface that splits instructions into 3 classes: – Arithmetic instructions (ADD. S, SUB. S, MUL. S, DIV. S, ABS. S, NEG. S, C. cond. S, CVT. S. W, CVT. W. S, TRUNC. W. S, MOVZ. S, MOVN. S) – From Coprocessor Data Transfer instructions (SWC 1, MFC 1, CFC 1) – To Coprocessor Data Transfer instructions (LWC 1, MTC 1, CTC 1) Slide 12

FPU Features • • Executes MIPS IV ISA single-precision FP instructions Thirty-two 32 -bit Floating Point Registers Two 32 -bit Control Registers One 3 -cycle (division takes 10 cycles) fully pipelined, nearly full IEEE-754 compliant, execution unit (from Albert Ma@MIT) • 6 -stage pipeline (R-X-X-X-CDB-WB) • Support for partial out-of-order execution and precise exceptions • Scalar Core dispatches FP instructions to FPU using an interface that splits instructions into 3 classes: – Arithmetic instructions (ADD. S, SUB. S, MUL. S, DIV. S, ABS. S, NEG. S, C. cond. S, CVT. S. W, CVT. W. S, TRUNC. W. S, MOVZ. S, MOVN. S) – From Coprocessor Data Transfer instructions (SWC 1, MFC 1, CFC 1) – To Coprocessor Data Transfer instructions (LWC 1, MTC 1, CTC 1) Slide 12

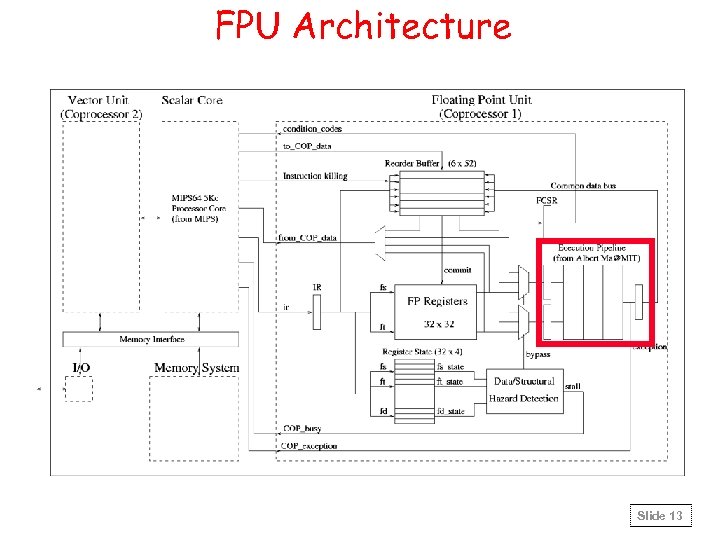

FPU Architecture Slide 13

FPU Architecture Slide 13

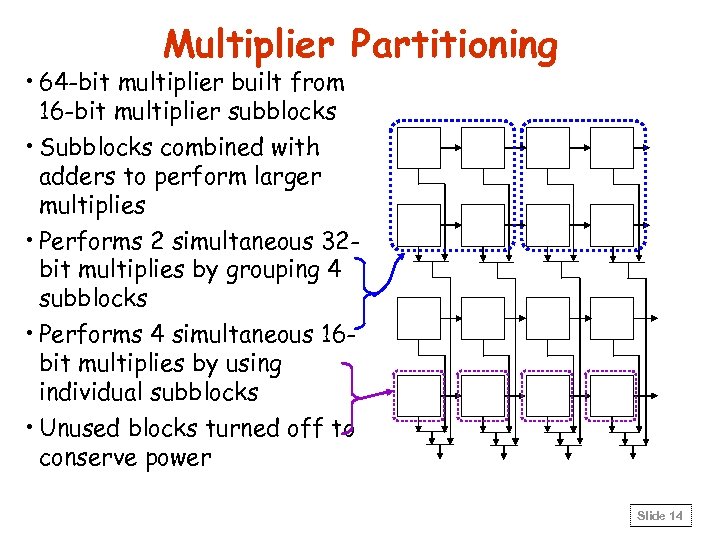

Multiplier Partitioning • 64 -bit multiplier built from 16 -bit multiplier subblocks • Subblocks combined with adders to perform larger multiplies • Performs 2 simultaneous 32 bit multiplies by grouping 4 subblocks • Performs 4 simultaneous 16 bit multiplies by using individual subblocks • Unused blocks turned off to conserve power Slide 14

Multiplier Partitioning • 64 -bit multiplier built from 16 -bit multiplier subblocks • Subblocks combined with adders to perform larger multiplies • Performs 2 simultaneous 32 bit multiplies by grouping 4 subblocks • Performs 4 simultaneous 16 bit multiplies by using individual subblocks • Unused blocks turned off to conserve power Slide 14

FPU Current Status • Current Functionality – Able to execute most instructions (all except C. cond. S, CFC 1 and CTC 1). – Supports precise exception semantics. – Functionality verification. » Used a random test generator that generates/kills instructions at random and compares the results from the RTL Verilog simulator against the results from an ISA Perl simulator. • What remains to be done – – – Instructions that use the Control Registers (C. cond. S, CFC 1 and CTC 1). Exception generation. Integrate execution pipeline with the rest of the design. Synthesize, place and route. Final assembly and verification of multiplier • Performance – Sustainable Throughput: 1 instruction/cycle (assuming no data hazards) – Instruction Latency: 6 cycles Slide 15

FPU Current Status • Current Functionality – Able to execute most instructions (all except C. cond. S, CFC 1 and CTC 1). – Supports precise exception semantics. – Functionality verification. » Used a random test generator that generates/kills instructions at random and compares the results from the RTL Verilog simulator against the results from an ISA Perl simulator. • What remains to be done – – – Instructions that use the Control Registers (C. cond. S, CFC 1 and CTC 1). Exception generation. Integrate execution pipeline with the rest of the design. Synthesize, place and route. Final assembly and verification of multiplier • Performance – Sustainable Throughput: 1 instruction/cycle (assuming no data hazards) – Instruction Latency: 6 cycles Slide 15

UC-IBM Agreement • Biggest IRAM Obstacle: Intellectual Property Agreement between University of California and IBM • Can university accept free fab costs ($2. 0 M to $2. 5 M) in return for capped non-exclusive patent licensing fees for IBM if UC files for IRAM patents? • Process started with IBM March 1999 • IBM won’t give full process info until contract • UC started negotiating seriously Jan 2000 • Agreement June 1, 2000! Slide 16

UC-IBM Agreement • Biggest IRAM Obstacle: Intellectual Property Agreement between University of California and IBM • Can university accept free fab costs ($2. 0 M to $2. 5 M) in return for capped non-exclusive patent licensing fees for IBM if UC files for IRAM patents? • Process started with IBM March 1999 • IBM won’t give full process info until contract • UC started negotiating seriously Jan 2000 • Agreement June 1, 2000! Slide 16

Other examples: IBM “Blue Gene” • 1 Peta. FLOPS in 2005 for $100 M? • Application: Protein Folding • Blue Gene Chip – 32 Multithreaded RISC processors + ? ? MB Embedded DRAM + high speed Network Interface on single 20 x 20 mm chip – 1 GFLOPS / processor • • 2’ x 2’ Board = 64 chips (2 K CPUs) Rack = 8 Boards (512 chips, 16 K CPUs) System = 64 Racks (512 boards, 32 K chips, 1 M CPUs) Total 1 million processors in just 2000 sq. ft. Slide 17

Other examples: IBM “Blue Gene” • 1 Peta. FLOPS in 2005 for $100 M? • Application: Protein Folding • Blue Gene Chip – 32 Multithreaded RISC processors + ? ? MB Embedded DRAM + high speed Network Interface on single 20 x 20 mm chip – 1 GFLOPS / processor • • 2’ x 2’ Board = 64 chips (2 K CPUs) Rack = 8 Boards (512 chips, 16 K CPUs) System = 64 Racks (512 boards, 32 K chips, 1 M CPUs) Total 1 million processors in just 2000 sq. ft. Slide 17

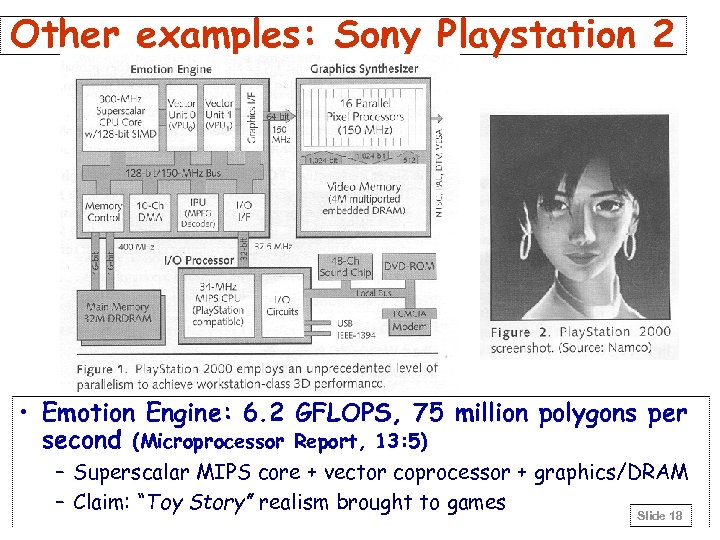

Other examples: Sony Playstation 2 • Emotion Engine: 6. 2 GFLOPS, 75 million polygons per second (Microprocessor Report, 13: 5) – Superscalar MIPS core + vector coprocessor + graphics/DRAM – Claim: “Toy Story” realism brought to games Slide 18

Other examples: Sony Playstation 2 • Emotion Engine: 6. 2 GFLOPS, 75 million polygons per second (Microprocessor Report, 13: 5) – Superscalar MIPS core + vector coprocessor + graphics/DRAM – Claim: “Toy Story” realism brought to games Slide 18

Outline 1) Example microprocessor for Post. PC gadgets 2) Motivation and the ISTORE project vision – AME: Availability, Maintainability, Evolutionary growth – ISTORE’s research principles – Benchmarks for AME • Conclusions and future work Slide 19

Outline 1) Example microprocessor for Post. PC gadgets 2) Motivation and the ISTORE project vision – AME: Availability, Maintainability, Evolutionary growth – ISTORE’s research principles – Benchmarks for AME • Conclusions and future work Slide 19

Lampson: Systems Challenges • Systems that work – Meeting their specs – Always available – Adapting to changing environment – Evolving while they run – Made from unreliable components – Growing without practical limit • • Credible simulations or analysis Writing good specs “Computer Systems Research Testing -Past and Future” Keynote address, Performance 17 th SOSP, – Understanding when it doesn’t matter Dec. 1999 Butler Lampson Microsoft Slide 20

Lampson: Systems Challenges • Systems that work – Meeting their specs – Always available – Adapting to changing environment – Evolving while they run – Made from unreliable components – Growing without practical limit • • Credible simulations or analysis Writing good specs “Computer Systems Research Testing -Past and Future” Keynote address, Performance 17 th SOSP, – Understanding when it doesn’t matter Dec. 1999 Butler Lampson Microsoft Slide 20

Hennessy: What Should the “New World” Focus Be? • Availability – Both appliance & service • Maintainability – Two functions: » Enhancing availability by preventing failure » Ease of SW and HW upgrades • Scalability – Especially of service “Back to the Future: Time to Return to Longstanding • Cost Problems in Computer Systems? ” – per device and per service transaction Keynote address, FCRC, • Performance May 1999 John Hennessy – Remains important, but its not SPECint Stanford Slide 21

Hennessy: What Should the “New World” Focus Be? • Availability – Both appliance & service • Maintainability – Two functions: » Enhancing availability by preventing failure » Ease of SW and HW upgrades • Scalability – Especially of service “Back to the Future: Time to Return to Longstanding • Cost Problems in Computer Systems? ” – per device and per service transaction Keynote address, FCRC, • Performance May 1999 John Hennessy – Remains important, but its not SPECint Stanford Slide 21

The real scalability problems: AME • Availability – systems should continue to meet quality of service goals despite hardware and software failures • Maintainability – systems should require only minimal ongoing human administration, regardless of scale or complexity • Evolutionary Growth – systems should evolve gracefully in terms of performance, maintainability, and availability as they are grown/upgraded/expanded • These are problems at today’s scales, and will only get worse as systems grow Slide 22

The real scalability problems: AME • Availability – systems should continue to meet quality of service goals despite hardware and software failures • Maintainability – systems should require only minimal ongoing human administration, regardless of scale or complexity • Evolutionary Growth – systems should evolve gracefully in terms of performance, maintainability, and availability as they are grown/upgraded/expanded • These are problems at today’s scales, and will only get worse as systems grow Slide 22

Principles for achieving AME (1) • No single points of failure • Redundancy everywhere • Performance robustness is more important than peak performance – “performance robustness” implies that real-world performance is comparable to best-case performance • Performance can be sacrificed for improvements in AME – resources should be dedicated to AME » compare: biological systems spend > 50% of resources on maintenance – can make up performance by scaling system Slide 23

Principles for achieving AME (1) • No single points of failure • Redundancy everywhere • Performance robustness is more important than peak performance – “performance robustness” implies that real-world performance is comparable to best-case performance • Performance can be sacrificed for improvements in AME – resources should be dedicated to AME » compare: biological systems spend > 50% of resources on maintenance – can make up performance by scaling system Slide 23

Principles for achieving AME (2) • Introspection – reactive techniques to detect and adapt to failures, workload variations, and system evolution – proactive techniques to anticipate and avert problems before they happen Slide 24

Principles for achieving AME (2) • Introspection – reactive techniques to detect and adapt to failures, workload variations, and system evolution – proactive techniques to anticipate and avert problems before they happen Slide 24

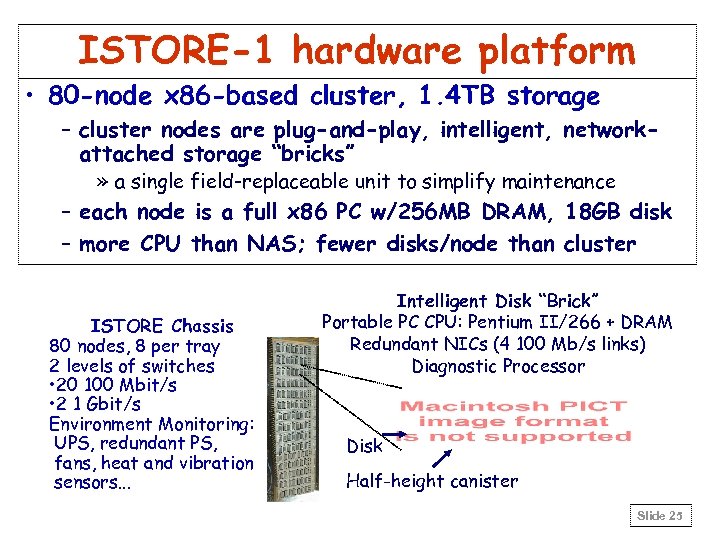

ISTORE-1 hardware platform • 80 -node x 86 -based cluster, 1. 4 TB storage – cluster nodes are plug-and-play, intelligent, networkattached storage “bricks” » a single field-replaceable unit to simplify maintenance – each node is a full x 86 PC w/256 MB DRAM, 18 GB disk – more CPU than NAS; fewer disks/node than cluster ISTORE Chassis 80 nodes, 8 per tray 2 levels of switches • 20 100 Mbit/s • 2 1 Gbit/s Environment Monitoring: UPS, redundant PS, fans, heat and vibration sensors. . . Intelligent Disk “Brick” Portable PC CPU: Pentium II/266 + DRAM Redundant NICs (4 100 Mb/s links) Diagnostic Processor Disk Half-height canister Slide 25

ISTORE-1 hardware platform • 80 -node x 86 -based cluster, 1. 4 TB storage – cluster nodes are plug-and-play, intelligent, networkattached storage “bricks” » a single field-replaceable unit to simplify maintenance – each node is a full x 86 PC w/256 MB DRAM, 18 GB disk – more CPU than NAS; fewer disks/node than cluster ISTORE Chassis 80 nodes, 8 per tray 2 levels of switches • 20 100 Mbit/s • 2 1 Gbit/s Environment Monitoring: UPS, redundant PS, fans, heat and vibration sensors. . . Intelligent Disk “Brick” Portable PC CPU: Pentium II/266 + DRAM Redundant NICs (4 100 Mb/s links) Diagnostic Processor Disk Half-height canister Slide 25

ISTORE-1 Status • • • 10 Nodes manufactured Boots OS Diagnostic Processor Interface SW complete PCB backplane: not yet designed Finish 80 node system: Summer 2000 Slide 26

ISTORE-1 Status • • • 10 Nodes manufactured Boots OS Diagnostic Processor Interface SW complete PCB backplane: not yet designed Finish 80 node system: Summer 2000 Slide 26

Hardware techniques • Fully shared-nothing cluster organization – truly scalable architecture – architecture that tolerates partial failure – automatic hardware redundancy Slide 27

Hardware techniques • Fully shared-nothing cluster organization – truly scalable architecture – architecture that tolerates partial failure – automatic hardware redundancy Slide 27

Hardware techniques (2) • No Central Processor Unit: distribute processing with storage – Serial lines, switches also growing with Moore’s Law; less need today to centralize vs. bus oriented systems – Most storage servers limited by speed of CPUs; why does this make sense? – Why not amortize sheet metal, power, cooling infrastructure for disk to add processor, memory, and network? – If AME is important, must provide resources to be used to help AME: local processors responsible for health and maintenance of their storage Slide 28

Hardware techniques (2) • No Central Processor Unit: distribute processing with storage – Serial lines, switches also growing with Moore’s Law; less need today to centralize vs. bus oriented systems – Most storage servers limited by speed of CPUs; why does this make sense? – Why not amortize sheet metal, power, cooling infrastructure for disk to add processor, memory, and network? – If AME is important, must provide resources to be used to help AME: local processors responsible for health and maintenance of their storage Slide 28

Hardware techniques (3) • Heavily instrumented hardware – sensors for temp, vibration, humidity, power, intrusion – helps detect environmental problems before they can affect system integrity • Independent diagnostic processor on each node – provides remote control of power, remote console access to the node, selection of node boot code – collects, stores, processes environmental data for abnormalities – non-volatile “flight recorder” functionality – all diagnostic processors connected via independent diagnostic network Slide 29

Hardware techniques (3) • Heavily instrumented hardware – sensors for temp, vibration, humidity, power, intrusion – helps detect environmental problems before they can affect system integrity • Independent diagnostic processor on each node – provides remote control of power, remote console access to the node, selection of node boot code – collects, stores, processes environmental data for abnormalities – non-volatile “flight recorder” functionality – all diagnostic processors connected via independent diagnostic network Slide 29

Hardware techniques (4) • On-demand network partitioning/isolation – Internet applications must remain available despite failures of components, therefore can isolate a subset for preventative maintenance – Allows testing, repair of online system – Managed by diagnostic processor and network switches via diagnostic network Slide 30

Hardware techniques (4) • On-demand network partitioning/isolation – Internet applications must remain available despite failures of components, therefore can isolate a subset for preventative maintenance – Allows testing, repair of online system – Managed by diagnostic processor and network switches via diagnostic network Slide 30

Hardware techniques (5) • Built-in fault injection capabilities – Power control to individual node components – Injectable glitches into I/O and memory busses – Managed by diagnostic processor – Used for proactive hardware introspection » automated detection of flaky components » controlled testing of error-recovery mechanisms – Important for AME benchmarking (see next slide) Slide 31

Hardware techniques (5) • Built-in fault injection capabilities – Power control to individual node components – Injectable glitches into I/O and memory busses – Managed by diagnostic processor – Used for proactive hardware introspection » automated detection of flaky components » controlled testing of error-recovery mechanisms – Important for AME benchmarking (see next slide) Slide 31

“Hardware” techniques (6) • Benchmarking – One reason for 1000 X processor performance was ability to measure (vs. debate) which is better » e. g. , Which most important to improve: clock rate, clocks per instruction, or instructions executed? – Need AME benchmarks “what gets measured gets done” “benchmarks shape a field” “quantification brings rigor” Slide 32

“Hardware” techniques (6) • Benchmarking – One reason for 1000 X processor performance was ability to measure (vs. debate) which is better » e. g. , Which most important to improve: clock rate, clocks per instruction, or instructions executed? – Need AME benchmarks “what gets measured gets done” “benchmarks shape a field” “quantification brings rigor” Slide 32

Availability benchmark methodology • Goal: quantify variation in Qo. S metrics as events occur that affect system availability • Leverage existing performance benchmarks – to generate fair workloads – to measure & trace quality of service metrics • Use fault injection to compromise system – hardware faults (disk, memory, network, power) – software faults (corrupt input, driver error returns) – maintenance events (repairs, SW/HW upgrades) • Examine single-fault and multi-fault workloads – the availability analogues of performance micro- and macro-benchmarks Slide 33

Availability benchmark methodology • Goal: quantify variation in Qo. S metrics as events occur that affect system availability • Leverage existing performance benchmarks – to generate fair workloads – to measure & trace quality of service metrics • Use fault injection to compromise system – hardware faults (disk, memory, network, power) – software faults (corrupt input, driver error returns) – maintenance events (repairs, SW/HW upgrades) • Examine single-fault and multi-fault workloads – the availability analogues of performance micro- and macro-benchmarks Slide 33

Benchmark Availability? Methodology for reporting results • Results are most accessible graphically – plot change in Qo. S metrics over time – compare to “normal” behavior? » 99% confidence intervals calculated from no-fault runs Slide 34

Benchmark Availability? Methodology for reporting results • Results are most accessible graphically – plot change in Qo. S metrics over time – compare to “normal” behavior? » 99% confidence intervals calculated from no-fault runs Slide 34

Example results: multiple-faults Windows 2000/IIS Linux/ Apache • Windows reconstructs ~3 x faster than Linux • Windows reconstruction noticeably affects application performance, while Linux reconstruction does not Slide 35

Example results: multiple-faults Windows 2000/IIS Linux/ Apache • Windows reconstructs ~3 x faster than Linux • Windows reconstruction noticeably affects application performance, while Linux reconstruction does not Slide 35

Conclusions (1): ISTORE • Availability, Maintainability, and Evolutionary growth are key challenges for server systems – more important even than performance • ISTORE is investigating ways to bring AME to large-scale, storage-intensive servers – via clusters of network-attached, computationallyenhanced storage nodes running distributed code – via hardware and software introspection – we are currently performing application studies to investigate and compare techniques • Availability benchmarks a powerful tool? – revealed undocumented design decisions affecting SW RAID availability on Linux and Windows 2000 Slide 36

Conclusions (1): ISTORE • Availability, Maintainability, and Evolutionary growth are key challenges for server systems – more important even than performance • ISTORE is investigating ways to bring AME to large-scale, storage-intensive servers – via clusters of network-attached, computationallyenhanced storage nodes running distributed code – via hardware and software introspection – we are currently performing application studies to investigate and compare techniques • Availability benchmarks a powerful tool? – revealed undocumented design decisions affecting SW RAID availability on Linux and Windows 2000 Slide 36

Conclusions (2) • IRAM attractive for two Post-PC applications because of low power, small size, high memory bandwidth – Gadgets: Embedded/Mobile devices – Infrastructure: Intelligent Storage and Networks • Post. PC infrastructure requires – New Goals: Availability, Maintainability, Evolution – New Principles: Introspection, Performance Robustness – New Techniques: Isolation/fault insertion, Software scrubbing – New Benchmarks: measure, compare AME metrics Slide 37

Conclusions (2) • IRAM attractive for two Post-PC applications because of low power, small size, high memory bandwidth – Gadgets: Embedded/Mobile devices – Infrastructure: Intelligent Storage and Networks • Post. PC infrastructure requires – New Goals: Availability, Maintainability, Evolution – New Principles: Introspection, Performance Robustness – New Techniques: Isolation/fault insertion, Software scrubbing – New Benchmarks: measure, compare AME metrics Slide 37