db77ab05f4aa6a674bf8e67649e8ea2f.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 133

COMPUTER ARITHMETIC Jehan-François Pâris jparis@uh. edu

COMPUTER ARITHMETIC Jehan-François Pâris jparis@uh. edu

Chapter Organization • • • Representing negative numbers Integer addition and subtraction Integer multiplication and division Floating point operations Examples of implementation – IBM 360, RISC, x 86

Chapter Organization • • • Representing negative numbers Integer addition and subtraction Integer multiplication and division Floating point operations Examples of implementation – IBM 360, RISC, x 86

A warning • Binary addition, subtraction, multiplication and division are very easy

A warning • Binary addition, subtraction, multiplication and division are very easy

ADDITION AND SUBTRACTION

ADDITION AND SUBTRACTION

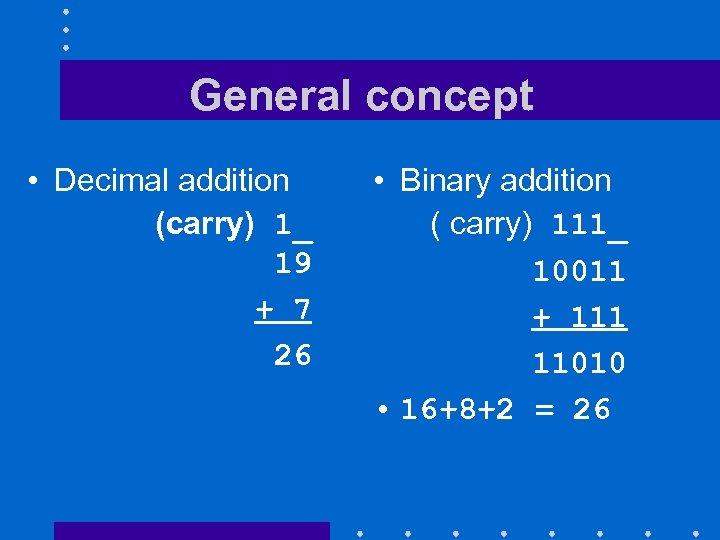

General concept • Decimal addition (carry) 1_ 19 + 7 26 • Binary addition ( carry) 111_ 10011 + 111 11010 • 16+8+2 = 26

General concept • Decimal addition (carry) 1_ 19 + 7 26 • Binary addition ( carry) 111_ 10011 + 111 11010 • 16+8+2 = 26

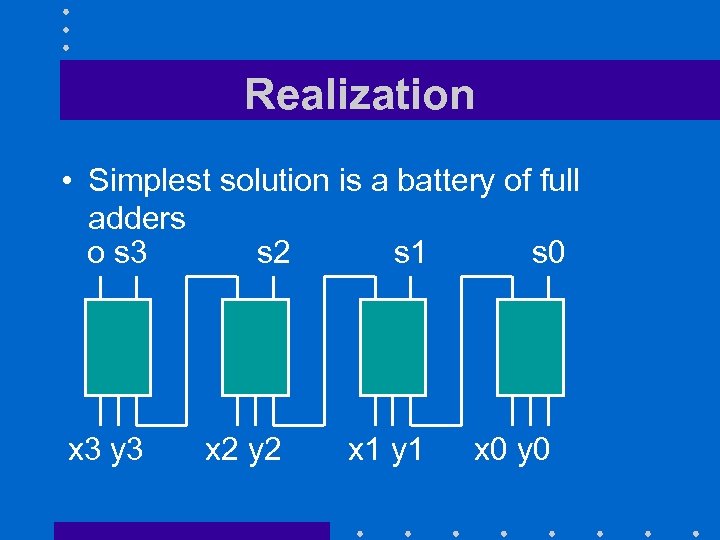

Realization • Simplest solution is a battery of full adders o s 3 s 2 s 1 s 0 x 3 y 3 x 2 y 2 x 1 y 1 x 0 y 0

Realization • Simplest solution is a battery of full adders o s 3 s 2 s 1 s 0 x 3 y 3 x 2 y 2 x 1 y 1 x 0 y 0

Observations • Adder add four-bit values • Output o indicates if there is an overflow – A result that cannot be represented using 4 bits – Happens when x + y > 15 • Operation is slowed down by carry propagation – Faster solutions (not discussed

Observations • Adder add four-bit values • Output o indicates if there is an overflow – A result that cannot be represented using 4 bits – Happens when x + y > 15 • Operation is slowed down by carry propagation – Faster solutions (not discussed

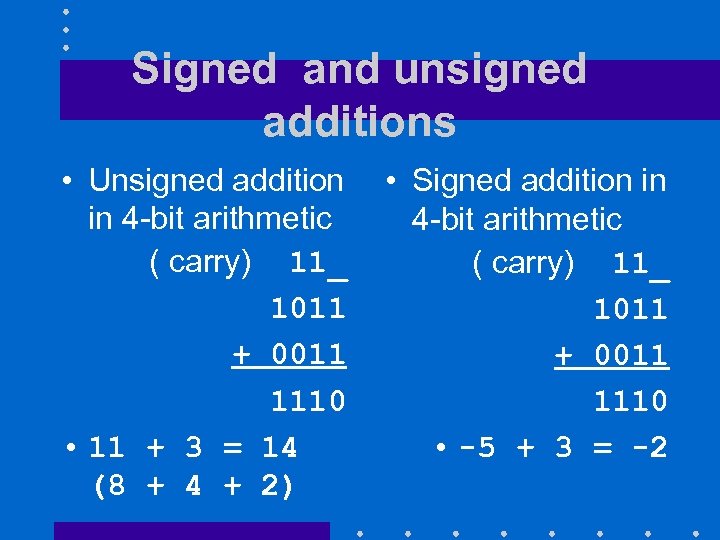

Signed and unsigned additions • Unsigned addition in 4 -bit arithmetic ( carry) 11_ 1011 + 0011 1110 • 11 + 3 = 14 (8 + 4 + 2) • Signed addition in 4 -bit arithmetic ( carry) 11_ 1011 + 0011 1110 • -5 + 3 = -2

Signed and unsigned additions • Unsigned addition in 4 -bit arithmetic ( carry) 11_ 1011 + 0011 1110 • 11 + 3 = 14 (8 + 4 + 2) • Signed addition in 4 -bit arithmetic ( carry) 11_ 1011 + 0011 1110 • -5 + 3 = -2

Signed and unsigned additions • Same rules apply even though bit strings represent different values • Sole difference is overflow handling

Signed and unsigned additions • Same rules apply even though bit strings represent different values • Sole difference is overflow handling

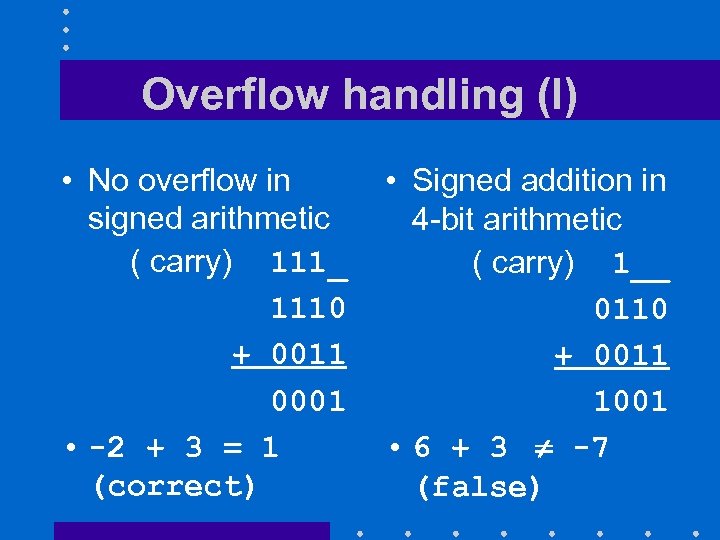

Overflow handling (I) • No overflow in signed arithmetic ( carry) 111_ 1110 + 0011 0001 • -2 + 3 = 1 (correct) • Signed addition in 4 -bit arithmetic ( carry) 1__ 0110 + 0011 1001 • 6 + 3 -7 (false)

Overflow handling (I) • No overflow in signed arithmetic ( carry) 111_ 1110 + 0011 0001 • -2 + 3 = 1 (correct) • Signed addition in 4 -bit arithmetic ( carry) 1__ 0110 + 0011 1001 • 6 + 3 -7 (false)

Overflow handling (II) • In signed arithmetic an overflow happens when – The sum of two positive numbers exceeds the maximum positive value that can be represented using n bits: 2 n – 1 – The sum of two negative numbers falls below the minimum negative value that can be represented using n

Overflow handling (II) • In signed arithmetic an overflow happens when – The sum of two positive numbers exceeds the maximum positive value that can be represented using n bits: 2 n – 1 – The sum of two negative numbers falls below the minimum negative value that can be represented using n

Example • Four-bit arithmetic: – Sixteen possible values – Positive overflow happens when result >7 – Negative overflow happens when result < -8 • Eight-bit arithmetic: – 256 possible values

Example • Four-bit arithmetic: – Sixteen possible values – Positive overflow happens when result >7 – Negative overflow happens when result < -8 • Eight-bit arithmetic: – 256 possible values

Overflow handling (III) • MIPS architecture handles signed and unsigned overflows in a very different fashion: – Ignores unsigned overflows • Implements modulo 2 n arithmetic – Generates an interrupt whenever it detects a signed overflows • Lets the OS handled the condition

Overflow handling (III) • MIPS architecture handles signed and unsigned overflows in a very different fashion: – Ignores unsigned overflows • Implements modulo 2 n arithmetic – Generates an interrupt whenever it detects a signed overflows • Lets the OS handled the condition

Why? • To keep the CPU as simple and regular as possible

Why? • To keep the CPU as simple and regular as possible

An interesting consequence • Most C compilers ignore overflows – C compilers must use unsigned arithmetic for their integer operations • Fortran compilers expect overflow conditions to be detected – Fortran compilers must use signed arithmetic for their integer operations

An interesting consequence • Most C compilers ignore overflows – C compilers must use unsigned arithmetic for their integer operations • Fortran compilers expect overflow conditions to be detected – Fortran compilers must use signed arithmetic for their integer operations

Subtraction • Can be implementing by – Specific hardware – Negating the subtrahend

Subtraction • Can be implementing by – Specific hardware – Negating the subtrahend

Negating a number • Toggle all bits then add one

Negating a number • Toggle all bits then add one

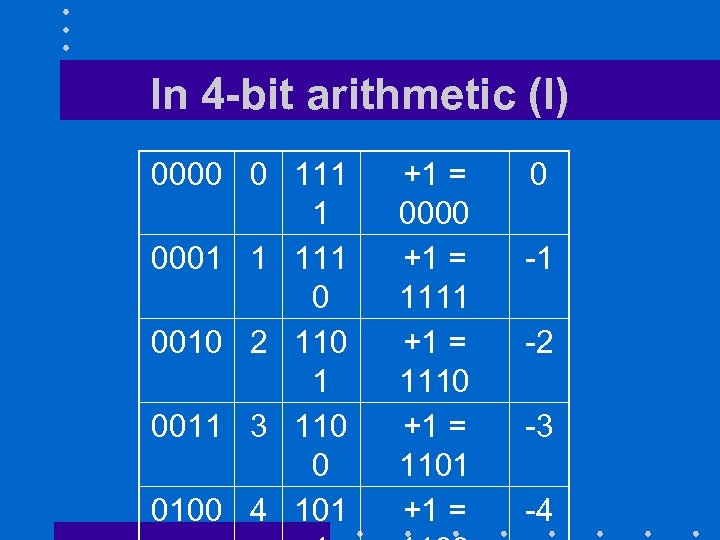

In 4 -bit arithmetic (I) 0000 0 111 1 0001 1 111 0 0010 2 110 1 0011 3 110 0 0100 4 101 +1 = 0000 +1 = 1111 +1 = 1110 +1 = 1101 +1 = 0 -1 -2 -3 -4

In 4 -bit arithmetic (I) 0000 0 111 1 0001 1 111 0 0010 2 110 1 0011 3 110 0 0100 4 101 +1 = 0000 +1 = 1111 +1 = 1110 +1 = 1101 +1 = 0 -1 -2 -3 -4

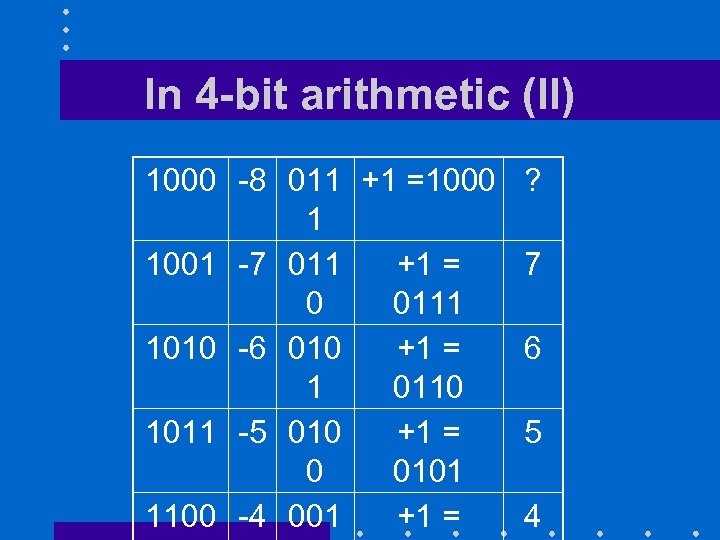

In 4 -bit arithmetic (II) 1000 -8 011 +1 =1000 1 1001 -7 011 +1 = 0 0111 1010 -6 010 +1 = 1 0110 1011 -5 010 +1 = 0 0101 1100 -4 001 +1 = ? 7 6 5 4

In 4 -bit arithmetic (II) 1000 -8 011 +1 =1000 1 1001 -7 011 +1 = 0 0111 1010 -6 010 +1 = 1 0110 1011 -5 010 +1 = 0 0101 1100 -4 001 +1 = ? 7 6 5 4

MULTIPLICATION

MULTIPLICATION

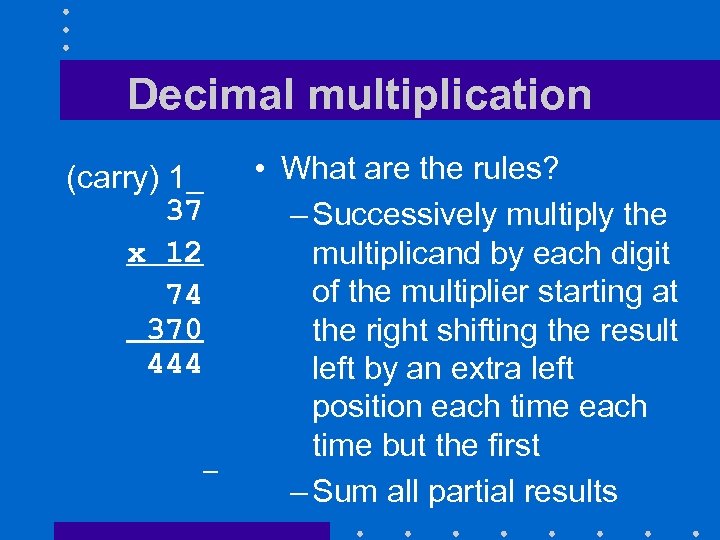

Decimal multiplication (carry) 1_ 37 x 12 74 370 444 • What are the rules? – Successively multiply the multiplicand by each digit of the multiplier starting at the right shifting the result left by an extra left position each time but the first – Sum all partial results

Decimal multiplication (carry) 1_ 37 x 12 74 370 444 • What are the rules? – Successively multiply the multiplicand by each digit of the multiplier starting at the right shifting the result left by an extra left position each time but the first – Sum all partial results

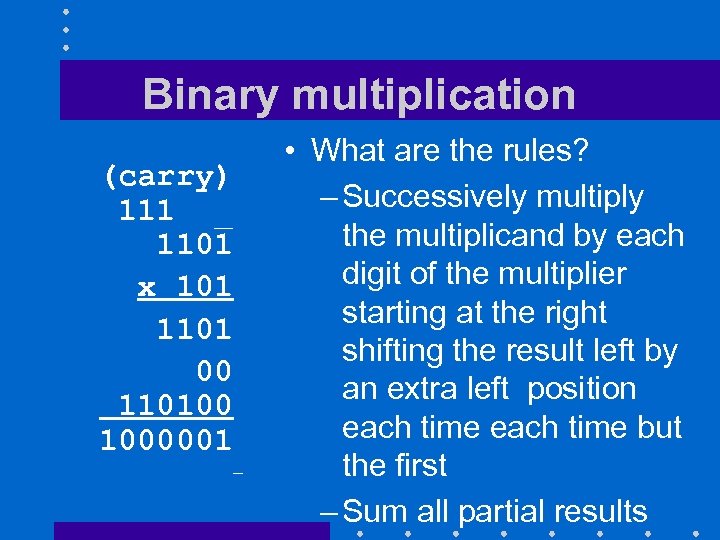

Binary multiplication (carry) 111 _ 1101 x 101 1101 00 110100 1000001 • What are the rules? – Successively multiply the multiplicand by each digit of the multiplier starting at the right shifting the result left by an extra left position each time but the first – Sum all partial results

Binary multiplication (carry) 111 _ 1101 x 101 1101 00 110100 1000001 • What are the rules? – Successively multiply the multiplicand by each digit of the multiplier starting at the right shifting the result left by an extra left position each time but the first – Sum all partial results

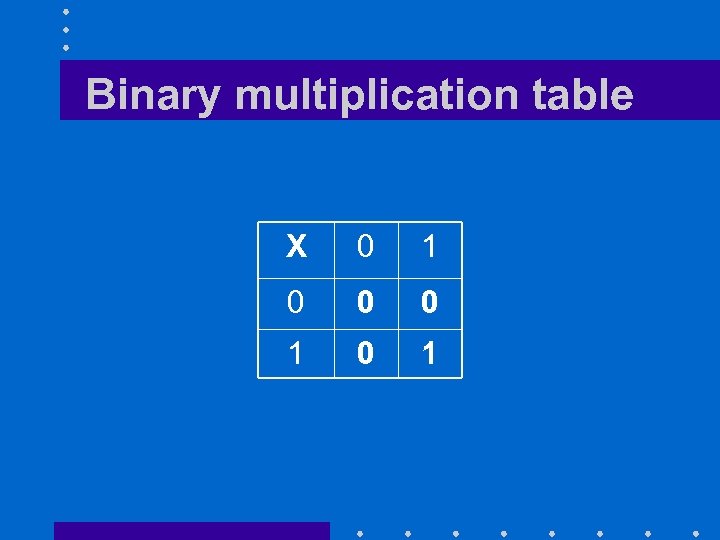

Binary multiplication table X 0 1 0 0 0 1

Binary multiplication table X 0 1 0 0 0 1

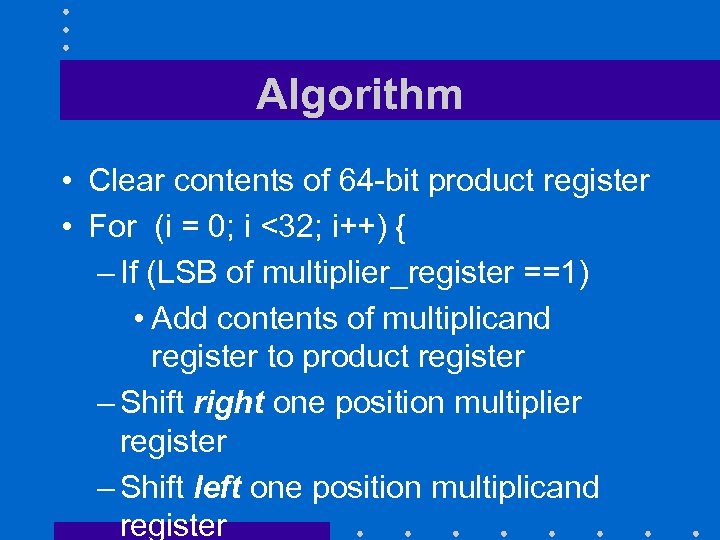

Algorithm • Clear contents of 64 -bit product register • For (i = 0; i <32; i++) { – If (LSB of multiplier_register ==1) • Add contents of multiplicand register to product register – Shift right one position multiplier register – Shift left one position multiplicand register

Algorithm • Clear contents of 64 -bit product register • For (i = 0; i <32; i++) { – If (LSB of multiplier_register ==1) • Add contents of multiplicand register to product register – Shift right one position multiplier register – Shift left one position multiplicand register

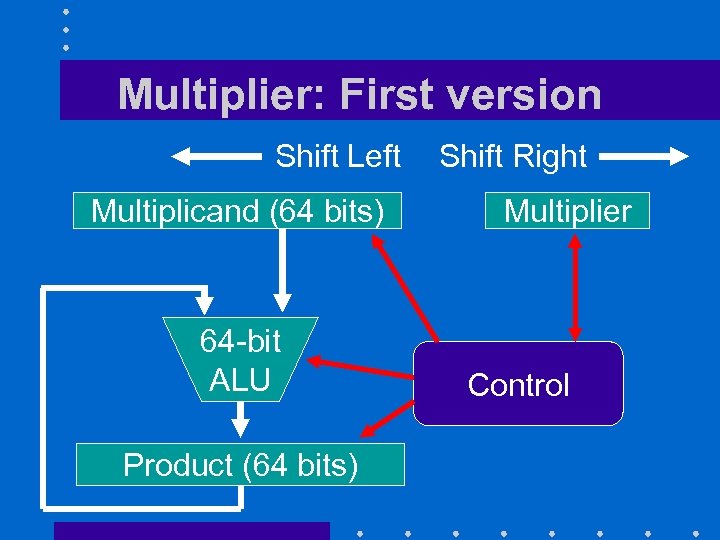

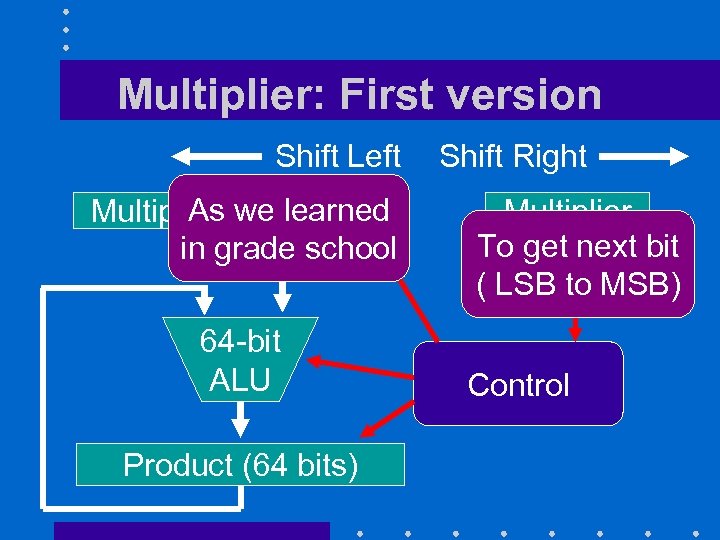

Multiplier: First version Shift Left Multiplicand (64 bits) 64 -bit ALU Product (64 bits) Shift Right Multiplier Control

Multiplier: First version Shift Left Multiplicand (64 bits) 64 -bit ALU Product (64 bits) Shift Right Multiplier Control

Multiplier: First version Shift Left As we learned Multiplicand (64 bits) in grade school 64 -bit ALU Product (64 bits) Shift Right Multiplier To get next bit ( LSB to MSB) Control

Multiplier: First version Shift Left As we learned Multiplicand (64 bits) in grade school 64 -bit ALU Product (64 bits) Shift Right Multiplier To get next bit ( LSB to MSB) Control

Explanations • Multiplicand register must be 64 -bit wide because 32 -bit multiplicand will be shifted 32 times to the left – Requires a 64 -bit ALU • Product register must be 64 -bit wide to accommodate the result • Contents of multiplier register is shifted 32 times to the right so that each bit successively becomes its least significant bit (LSB)

Explanations • Multiplicand register must be 64 -bit wide because 32 -bit multiplicand will be shifted 32 times to the left – Requires a 64 -bit ALU • Product register must be 64 -bit wide to accommodate the result • Contents of multiplier register is shifted 32 times to the right so that each bit successively becomes its least significant bit (LSB)

Example (I) • Multiply 0011 by 0011 • Start Multiplicand Multiplier Product 0011 0000 • First addition Multiplicand Multiplier Product 0011

Example (I) • Multiply 0011 by 0011 • Start Multiplicand Multiplier Product 0011 0000 • First addition Multiplicand Multiplier Product 0011

Example (II) • Shift right and left Multiplicand Multiplier Product 0110 0001 0011 • Second addition Multiplicand Multiplier Product 0110 0001 1001 – 0110 + 011 = 1001

Example (II) • Shift right and left Multiplicand Multiplier Product 0110 0001 0011 • Second addition Multiplicand Multiplier Product 0110 0001 1001 – 0110 + 011 = 1001

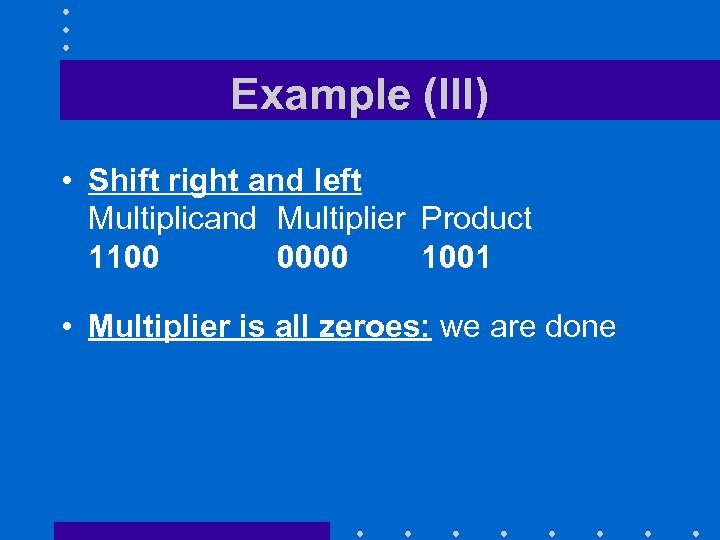

Example (III) • Shift right and left Multiplicand Multiplier Product 1100 0000 1001 • Multiplier is all zeroes: we are done

Example (III) • Shift right and left Multiplicand Multiplier Product 1100 0000 1001 • Multiplier is all zeroes: we are done

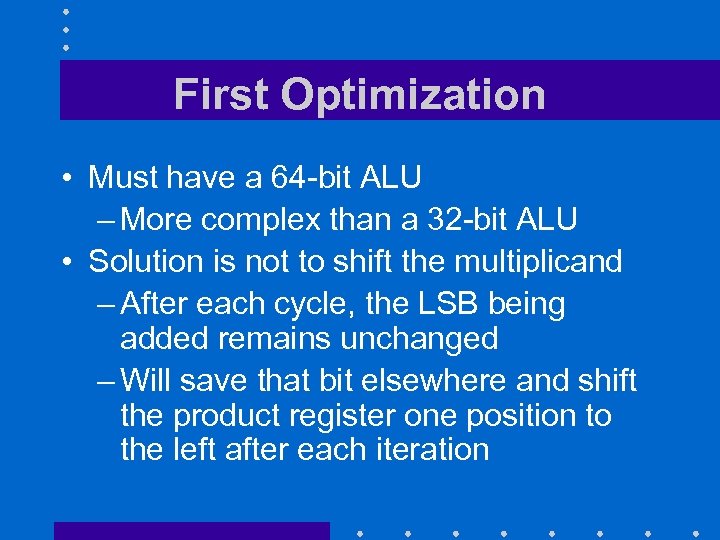

First Optimization • Must have a 64 -bit ALU – More complex than a 32 -bit ALU • Solution is not to shift the multiplicand – After each cycle, the LSB being added remains unchanged – Will save that bit elsewhere and shift the product register one position to the left after each iteration

First Optimization • Must have a 64 -bit ALU – More complex than a 32 -bit ALU • Solution is not to shift the multiplicand – After each cycle, the LSB being added remains unchanged – Will save that bit elsewhere and shift the product register one position to the left after each iteration

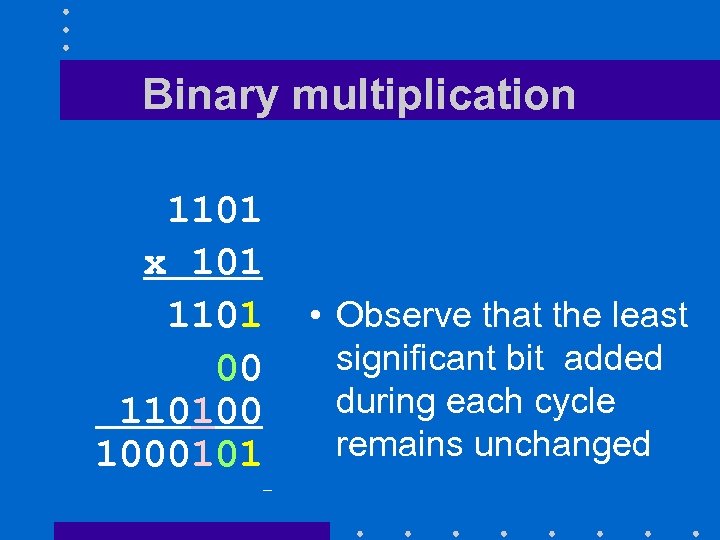

Binary multiplication 1101 x 101 1101 00 110100 1000101 • Observe that the least significant bit added during each cycle remains unchanged

Binary multiplication 1101 x 101 1101 00 110100 1000101 • Observe that the least significant bit added during each cycle remains unchanged

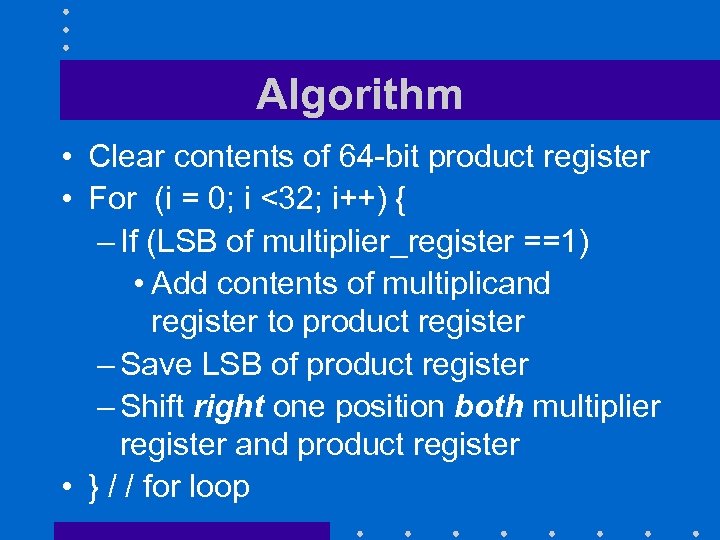

Algorithm • Clear contents of 64 -bit product register • For (i = 0; i <32; i++) { – If (LSB of multiplier_register ==1) • Add contents of multiplicand register to product register – Save LSB of product register – Shift right one position both multiplier register and product register • } / / for loop

Algorithm • Clear contents of 64 -bit product register • For (i = 0; i <32; i++) { – If (LSB of multiplier_register ==1) • Add contents of multiplicand register to product register – Save LSB of product register – Shift right one position both multiplier register and product register • } / / for loop

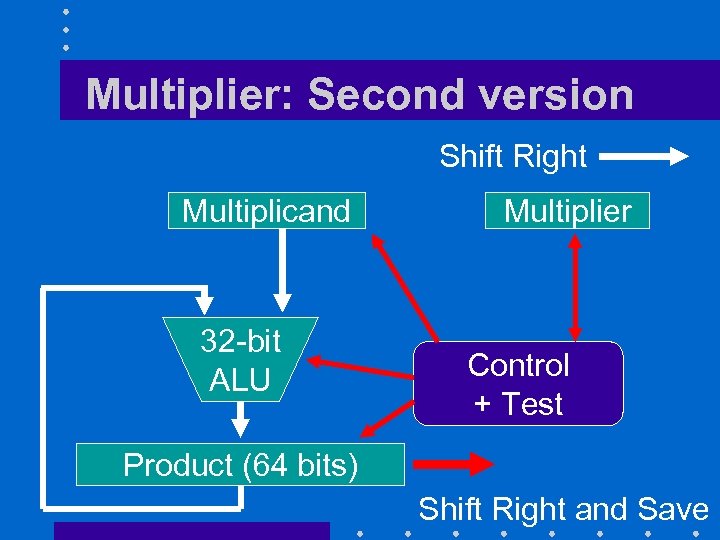

Multiplier: Second version Shift Right Multiplicand 32 -bit ALU Multiplier Control + Test Product (64 bits) Shift Right and Save

Multiplier: Second version Shift Right Multiplicand 32 -bit ALU Multiplier Control + Test Product (64 bits) Shift Right and Save

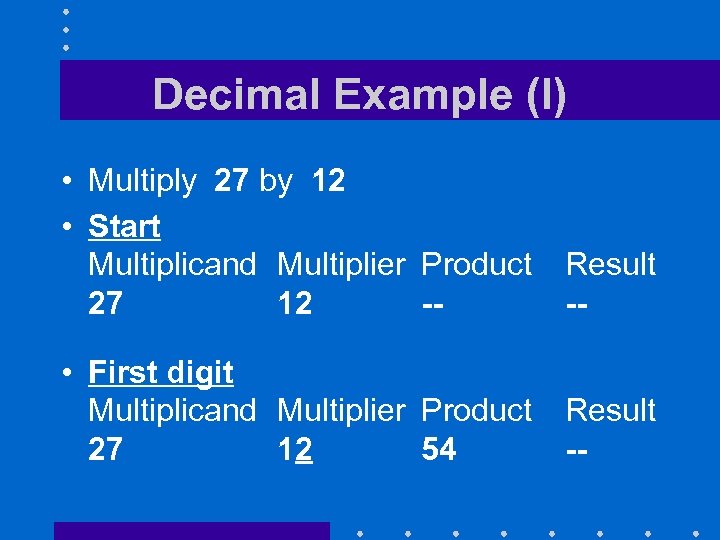

Decimal Example (I) • Multiply 27 by 12 • Start Multiplicand Multiplier Product 27 12 -- Result -- • First digit Multiplicand Multiplier Product 27 12 54 Result --

Decimal Example (I) • Multiply 27 by 12 • Start Multiplicand Multiplier Product 27 12 -- Result -- • First digit Multiplicand Multiplier Product 27 12 54 Result --

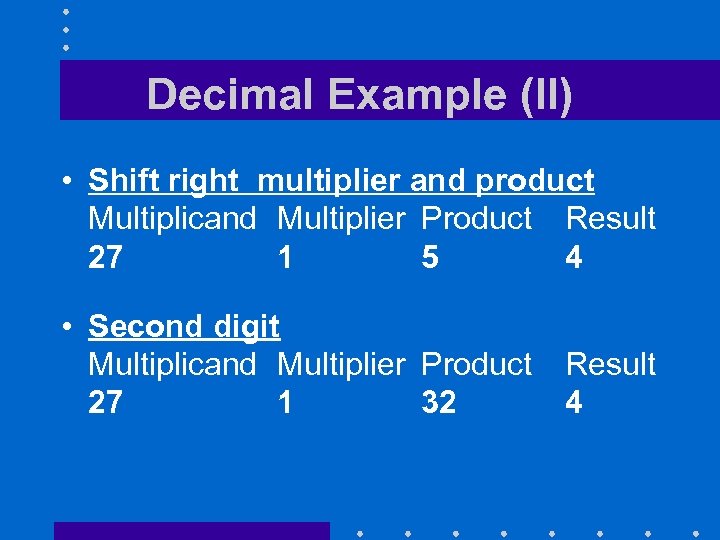

Decimal Example (II) • Shift right multiplier and product Multiplicand Multiplier Product Result 27 1 5 4 • Second digit Multiplicand Multiplier Product 27 1 32 Result 4

Decimal Example (II) • Shift right multiplier and product Multiplicand Multiplier Product Result 27 1 5 4 • Second digit Multiplicand Multiplier Product 27 1 32 Result 4

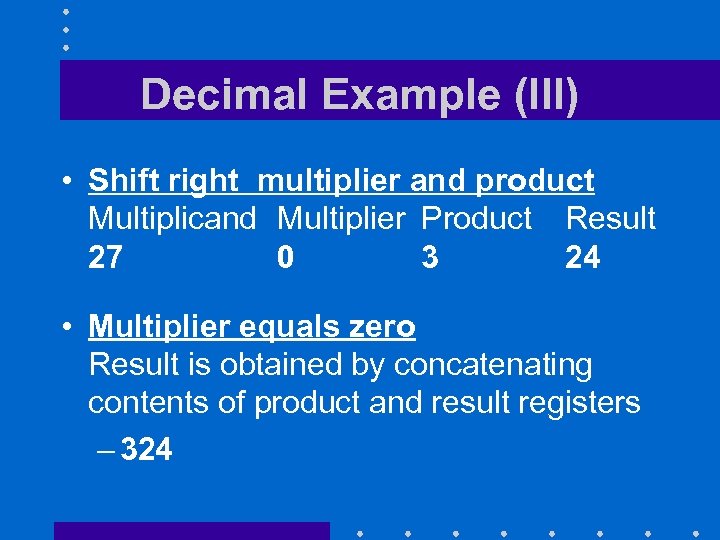

Decimal Example (III) • Shift right multiplier and product Multiplicand Multiplier Product Result 27 0 3 24 • Multiplier equals zero Result is obtained by concatenating contents of product and result registers – 324

Decimal Example (III) • Shift right multiplier and product Multiplicand Multiplier Product Result 27 0 3 24 • Multiplier equals zero Result is obtained by concatenating contents of product and result registers – 324

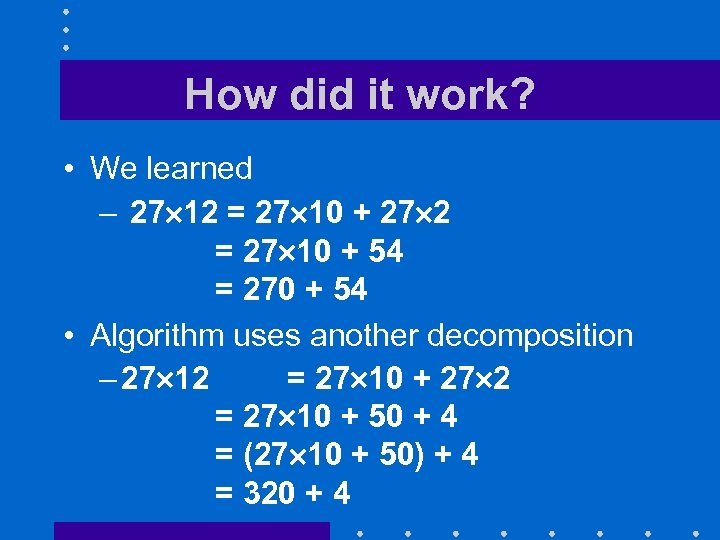

How did it work? • We learned – 27 12 = 27 10 + 27 2 = 27 10 + 54 = 270 + 54 • Algorithm uses another decomposition – 27 12 = 27 10 + 27 2 = 27 10 + 50 + 4 = (27 10 + 50) + 4 = 320 + 4

How did it work? • We learned – 27 12 = 27 10 + 27 2 = 27 10 + 54 = 270 + 54 • Algorithm uses another decomposition – 27 12 = 27 10 + 27 2 = 27 10 + 50 + 4 = (27 10 + 50) + 4 = 320 + 4

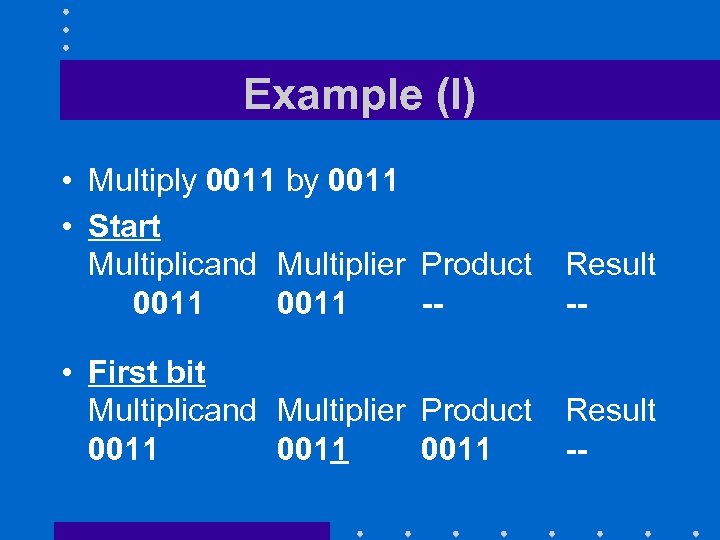

Example (I) • Multiply 0011 by 0011 • Start Multiplicand Multiplier Product 0011 -- Result -- • First bit Multiplicand Multiplier Product 0011 Result --

Example (I) • Multiply 0011 by 0011 • Start Multiplicand Multiplier Product 0011 -- Result -- • First bit Multiplicand Multiplier Product 0011 Result --

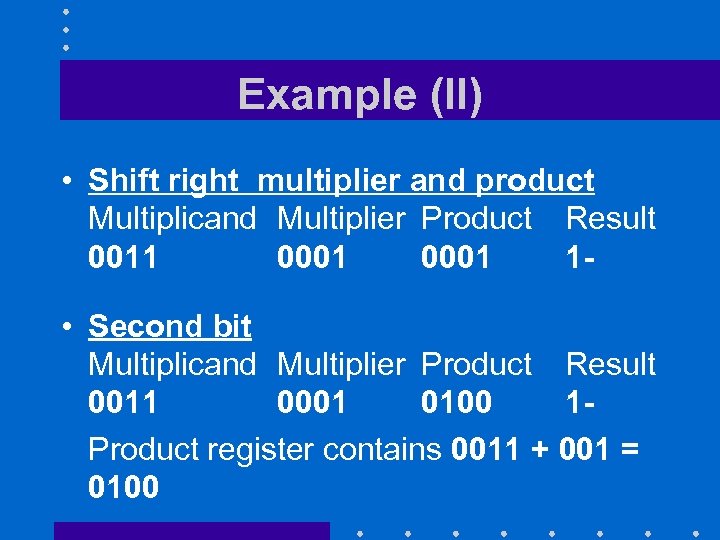

Example (II) • Shift right multiplier and product Multiplicand Multiplier Product Result 0011 0001 1 • Second bit Multiplicand Multiplier Product Result 0011 0001 0100 1 Product register contains 0011 + 001 = 0100

Example (II) • Shift right multiplier and product Multiplicand Multiplier Product Result 0011 0001 1 • Second bit Multiplicand Multiplier Product Result 0011 0001 0100 1 Product register contains 0011 + 001 = 0100

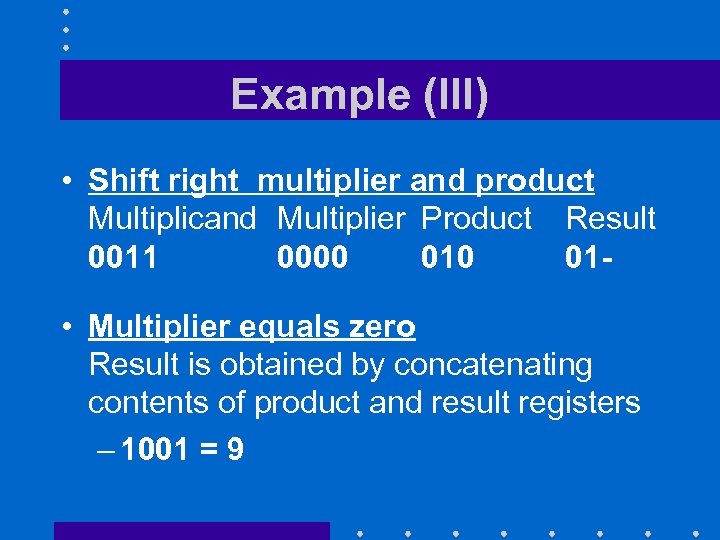

Example (III) • Shift right multiplier and product Multiplicand Multiplier Product Result 0011 0000 01 • Multiplier equals zero Result is obtained by concatenating contents of product and result registers – 1001 = 9

Example (III) • Shift right multiplier and product Multiplicand Multiplier Product Result 0011 0000 01 • Multiplier equals zero Result is obtained by concatenating contents of product and result registers – 1001 = 9

Second Optimization • Both multiplier and product must be shifted to one position to the right after each iteration • Both are now 32 -bit quantities • Can store both quantities in the product register

Second Optimization • Both multiplier and product must be shifted to one position to the right after each iteration • Both are now 32 -bit quantities • Can store both quantities in the product register

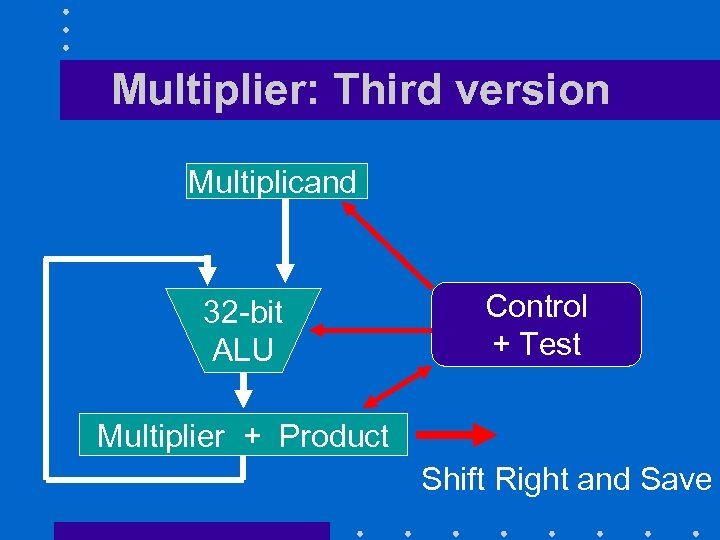

Multiplier: Third version Multiplicand 32 -bit ALU Control + Test Multiplier + Product Shift Right and Save

Multiplier: Third version Multiplicand 32 -bit ALU Control + Test Multiplier + Product Shift Right and Save

Third Optimization • Multiplication requires 32 additions and 32 shift operations • Can have two or more partial multiplications – One using bits 0 -15 of multiplier – A second using bits 16 -31 then add together the partial results

Third Optimization • Multiplication requires 32 additions and 32 shift operations • Can have two or more partial multiplications – One using bits 0 -15 of multiplier – A second using bits 16 -31 then add together the partial results

Multiplying negative numbers • Can use the same algorithm as before but we must extend the sign bit of the product

Multiplying negative numbers • Can use the same algorithm as before but we must extend the sign bit of the product

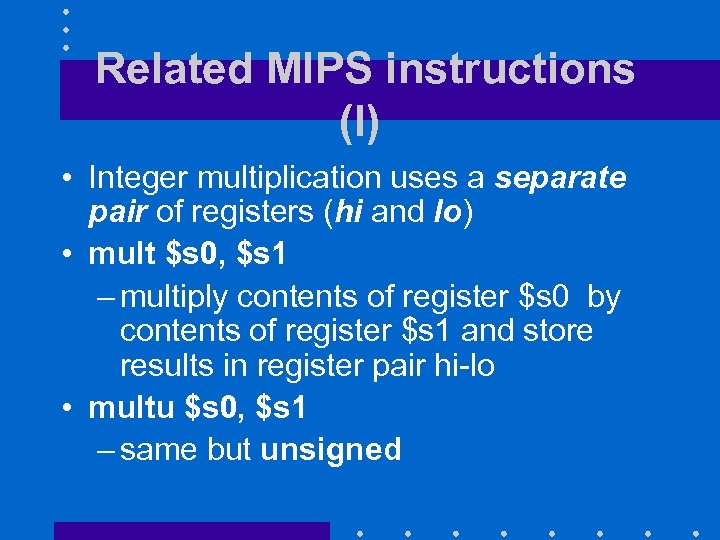

Related MIPS instructions (I) • Integer multiplication uses a separate pair of registers (hi and lo) • mult $s 0, $s 1 – multiply contents of register $s 0 by contents of register $s 1 and store results in register pair hi-lo • multu $s 0, $s 1 – same but unsigned

Related MIPS instructions (I) • Integer multiplication uses a separate pair of registers (hi and lo) • mult $s 0, $s 1 – multiply contents of register $s 0 by contents of register $s 1 and store results in register pair hi-lo • multu $s 0, $s 1 – same but unsigned

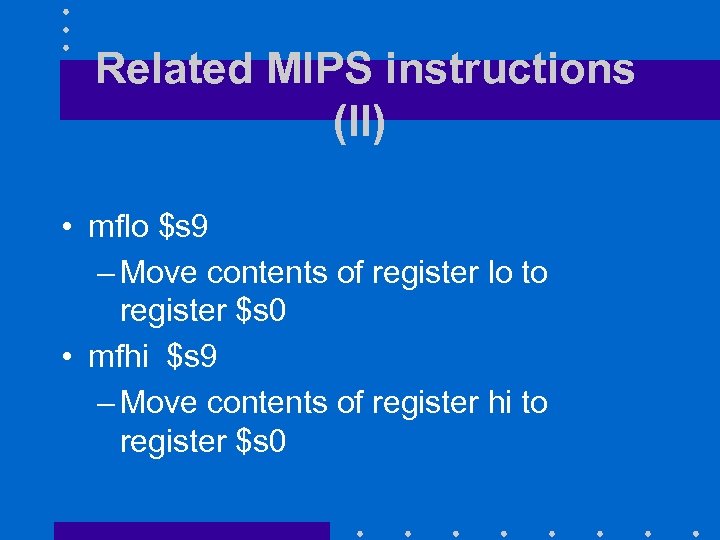

Related MIPS instructions (II) • mflo $s 9 – Move contents of register lo to register $s 0 • mfhi $s 9 – Move contents of register hi to register $s 0

Related MIPS instructions (II) • mflo $s 9 – Move contents of register lo to register $s 0 • mfhi $s 9 – Move contents of register hi to register $s 0

DIVISION

DIVISION

Division • Implemented by successive subtractions • Result must verify the equality Dividend = Multiplier× Quotient + Remainder

Division • Implemented by successive subtractions • Result must verify the equality Dividend = Multiplier× Quotient + Remainder

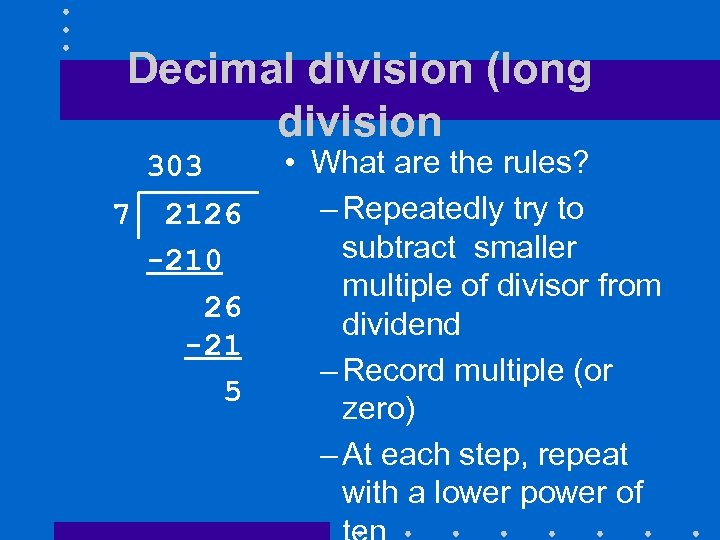

Decimal division (long division 303 7 2126 -210 26 -21 5 • What are the rules? – Repeatedly try to subtract smaller multiple of divisor from dividend – Record multiple (or zero) – At each step, repeat with a lower power of

Decimal division (long division 303 7 2126 -210 26 -21 5 • What are the rules? – Repeatedly try to subtract smaller multiple of divisor from dividend – Record multiple (or zero) – At each step, repeat with a lower power of

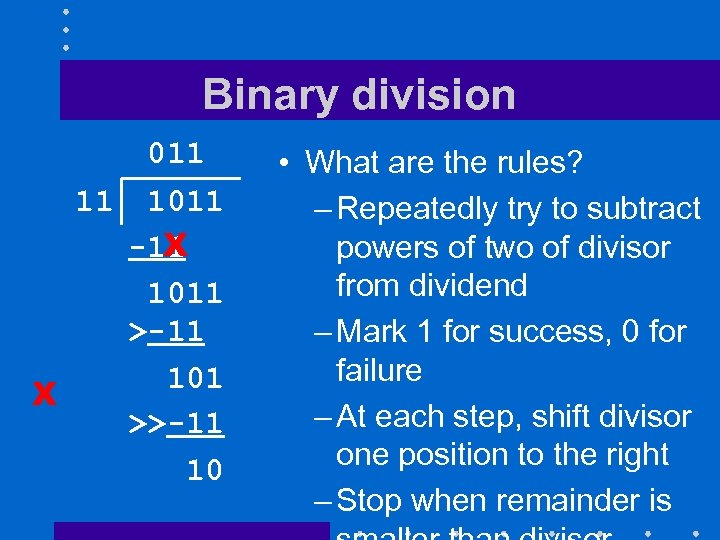

Binary division 011 11 1011 X -11 1011 >-11 101 X >>-11 10 • What are the rules? – Repeatedly try to subtract powers of two of divisor from dividend – Mark 1 for success, 0 for failure – At each step, shift divisor one position to the right – Stop when remainder is

Binary division 011 11 1011 X -11 1011 >-11 101 X >>-11 10 • What are the rules? – Repeatedly try to subtract powers of two of divisor from dividend – Mark 1 for success, 0 for failure – At each step, shift divisor one position to the right – Stop when remainder is

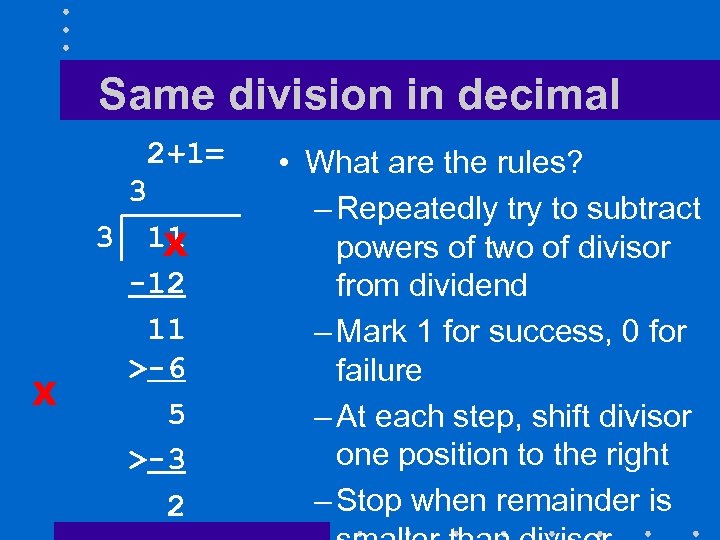

Same division in decimal 2+1= 3 3 X 11 X -12 11 >-6 5 >-3 2 • What are the rules? – Repeatedly try to subtract powers of two of divisor from dividend – Mark 1 for success, 0 for failure – At each step, shift divisor one position to the right – Stop when remainder is

Same division in decimal 2+1= 3 3 X 11 X -12 11 >-6 5 >-3 2 • What are the rules? – Repeatedly try to subtract powers of two of divisor from dividend – Mark 1 for success, 0 for failure – At each step, shift divisor one position to the right – Stop when remainder is

Observations • Binary division is actually simpler – We start with a left-shifted version of divisor – We try to subtract it from dividend • No need to find out which multiple to subtract – We mark 1 for success, 0 for failure – We shift divisor one position left after

Observations • Binary division is actually simpler – We start with a left-shifted version of divisor – We try to subtract it from dividend • No need to find out which multiple to subtract – We mark 1 for success, 0 for failure – We shift divisor one position left after

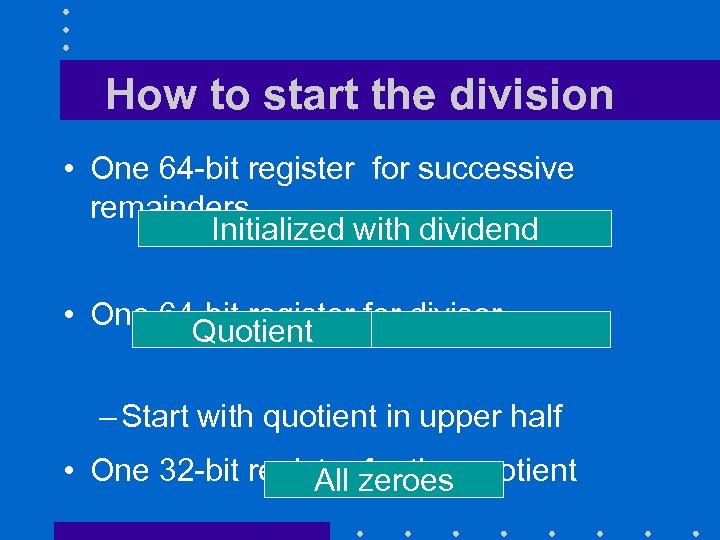

How to start the division • One 64 -bit register for successive remainders Initialized with dividend • One 64 -bit register for divisor Quotient – Start with quotient in upper half • One 32 -bit register zeroes quotient All for the

How to start the division • One 64 -bit register for successive remainders Initialized with dividend • One 64 -bit register for divisor Quotient – Start with quotient in upper half • One 32 -bit register zeroes quotient All for the

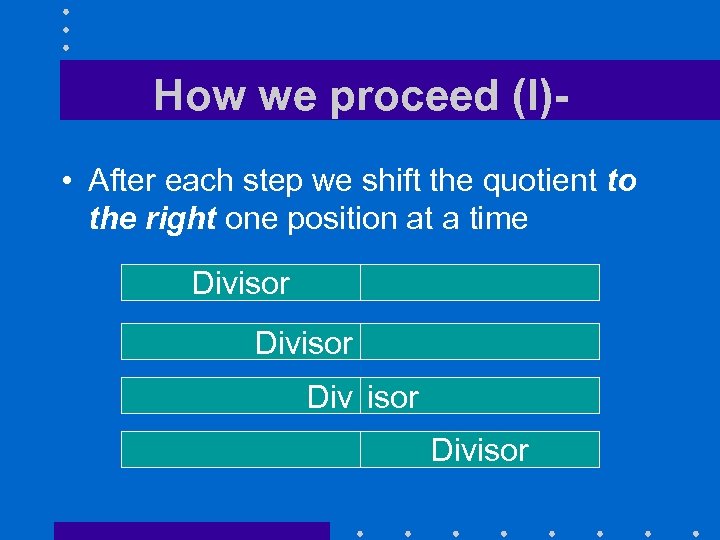

How we proceed (I) • After each step we shift the quotient to the right one position at a time Divisor Divisor

How we proceed (I) • After each step we shift the quotient to the right one position at a time Divisor Divisor

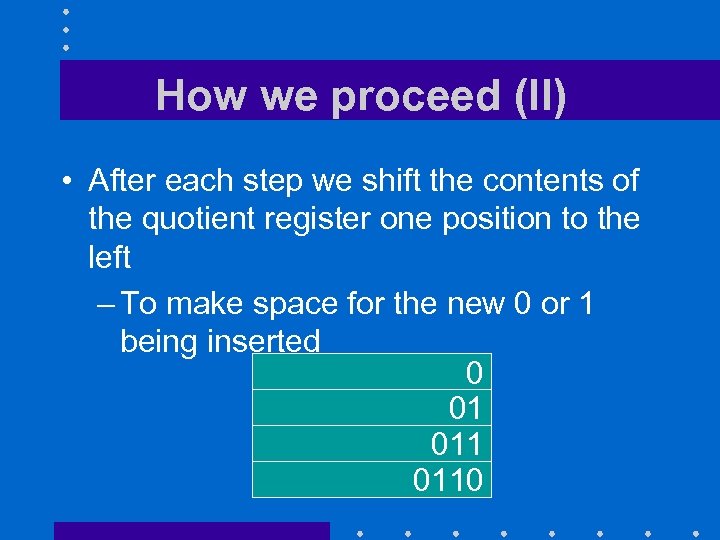

How we proceed (II) • After each step we shift the contents of the quotient register one position to the left – To make space for the new 0 or 1 being inserted 0 01 0110

How we proceed (II) • After each step we shift the contents of the quotient register one position to the left – To make space for the new 0 or 1 being inserted 0 01 0110

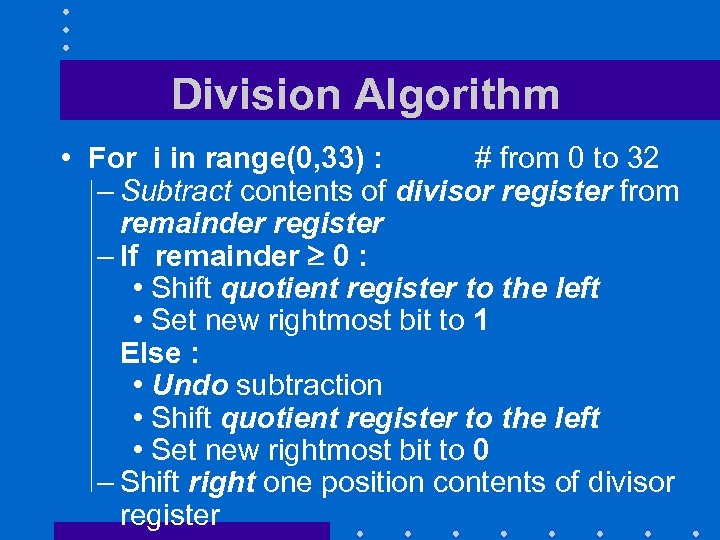

Division Algorithm • For i in range(0, 33) : # from 0 to 32 – Subtract contents of divisor register from remainder register – If remainder 0 : • Shift quotient register to the left • Set new rightmost bit to 1 Else : • Undo subtraction • Shift quotient register to the left • Set new rightmost bit to 0 – Shift right one position contents of divisor register

Division Algorithm • For i in range(0, 33) : # from 0 to 32 – Subtract contents of divisor register from remainder register – If remainder 0 : • Shift quotient register to the left • Set new rightmost bit to 1 Else : • Undo subtraction • Shift quotient register to the left • Set new rightmost bit to 0 – Shift right one position contents of divisor register

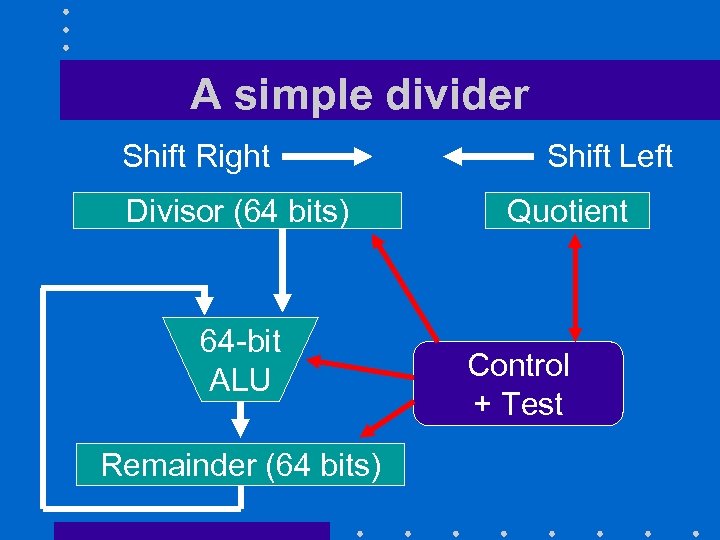

A simple divider Shift Right Divisor (64 bits) 64 -bit ALU Remainder (64 bits) Shift Left Quotient Control + Test

A simple divider Shift Right Divisor (64 bits) 64 -bit ALU Remainder (64 bits) Shift Left Quotient Control + Test

Signed division • Easiest solution is to remember the sign of the operands and adjust the sign of the quotient and remainder accordingly • A little problem: 5 2 = 2 and the remainder is 1 -5 2 = -2 and the remainder is -1 The sign of the remainder must match the sign of the quotient

Signed division • Easiest solution is to remember the sign of the operands and adjust the sign of the quotient and remainder accordingly • A little problem: 5 2 = 2 and the remainder is 1 -5 2 = -2 and the remainder is -1 The sign of the remainder must match the sign of the quotient

Related MIPS instructions • Integer division uses the same pair of registers (hi and lo) as integer multiplication • div $s 0, $s 1 – divide contents of register $s 0 by contents of register $s, leave the quotient in register lo and the remainder in register hi • divu $s 0, $s 1 – same but unsigned

Related MIPS instructions • Integer division uses the same pair of registers (hi and lo) as integer multiplication • div $s 0, $s 1 – divide contents of register $s 0 by contents of register $s, leave the quotient in register lo and the remainder in register hi • divu $s 0, $s 1 – same but unsigned

TRANSITION SLIDE • Here end the materials that were on the first fall 2012 midterm • Here start the materials that will be on the fall 2012 midterm To be moved to the right place

TRANSITION SLIDE • Here end the materials that were on the first fall 2012 midterm • Here start the materials that will be on the fall 2012 midterm To be moved to the right place

FLOATING POINT OPERATIONS

FLOATING POINT OPERATIONS

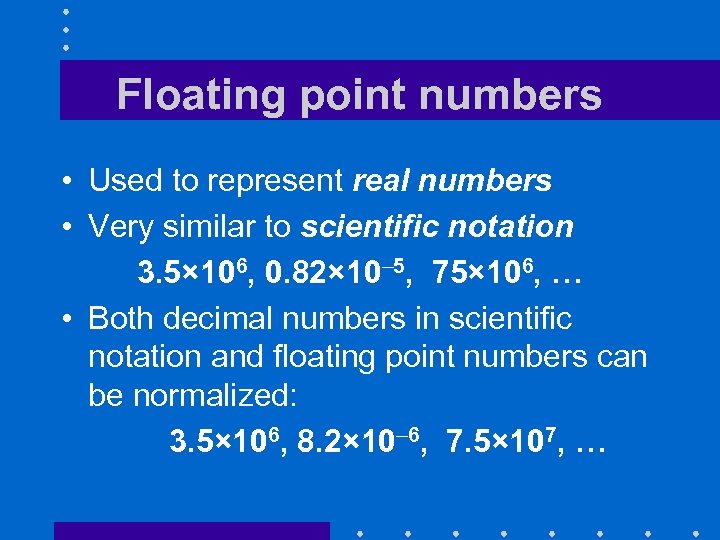

Floating point numbers • Used to represent real numbers • Very similar to scientific notation 3. 5× 106, 0. 82× 10– 5, 75× 106, … • Both decimal numbers in scientific notation and floating point numbers can be normalized: 3. 5× 106, 8. 2× 10– 6, 7. 5× 107, …

Floating point numbers • Used to represent real numbers • Very similar to scientific notation 3. 5× 106, 0. 82× 10– 5, 75× 106, … • Both decimal numbers in scientific notation and floating point numbers can be normalized: 3. 5× 106, 8. 2× 10– 6, 7. 5× 107, …

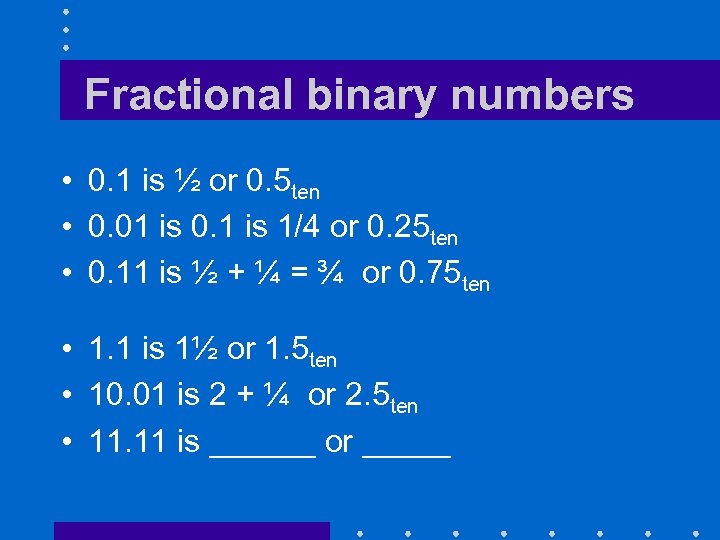

Fractional binary numbers • 0. 1 is ½ or 0. 5 ten • 0. 01 is 0. 1 is 1/4 or 0. 25 ten • 0. 11 is ½ + ¼ = ¾ or 0. 75 ten • 1. 1 is 1½ or 1. 5 ten • 10. 01 is 2 + ¼ or 2. 5 ten • 11. 11 is ______ or _____

Fractional binary numbers • 0. 1 is ½ or 0. 5 ten • 0. 01 is 0. 1 is 1/4 or 0. 25 ten • 0. 11 is ½ + ¼ = ¾ or 0. 75 ten • 1. 1 is 1½ or 1. 5 ten • 10. 01 is 2 + ¼ or 2. 5 ten • 11. 11 is ______ or _____

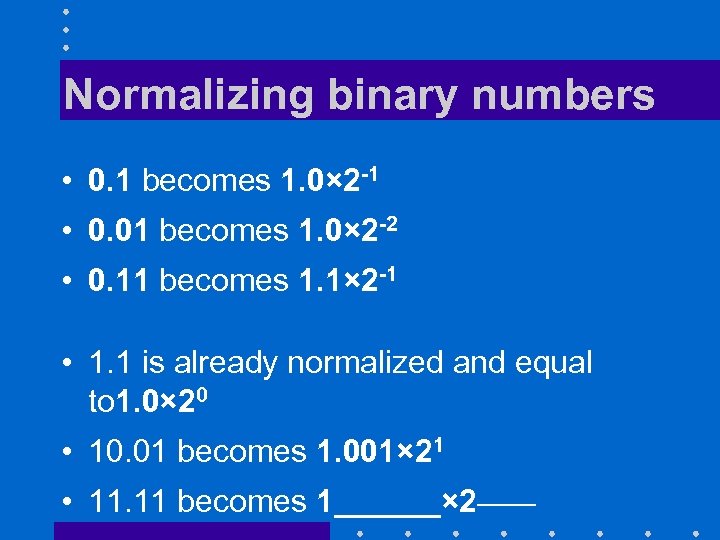

Normalizing binary numbers • 0. 1 becomes 1. 0× 2 -1 • 0. 01 becomes 1. 0× 2 -2 • 0. 11 becomes 1. 1× 2 -1 • 1. 1 is already normalized and equal to 1. 0× 20 • 10. 01 becomes 1. 001× 21 • 11. 11 becomes 1______× 2_____

Normalizing binary numbers • 0. 1 becomes 1. 0× 2 -1 • 0. 01 becomes 1. 0× 2 -2 • 0. 11 becomes 1. 1× 2 -1 • 1. 1 is already normalized and equal to 1. 0× 20 • 10. 01 becomes 1. 001× 21 • 11. 11 becomes 1______× 2_____

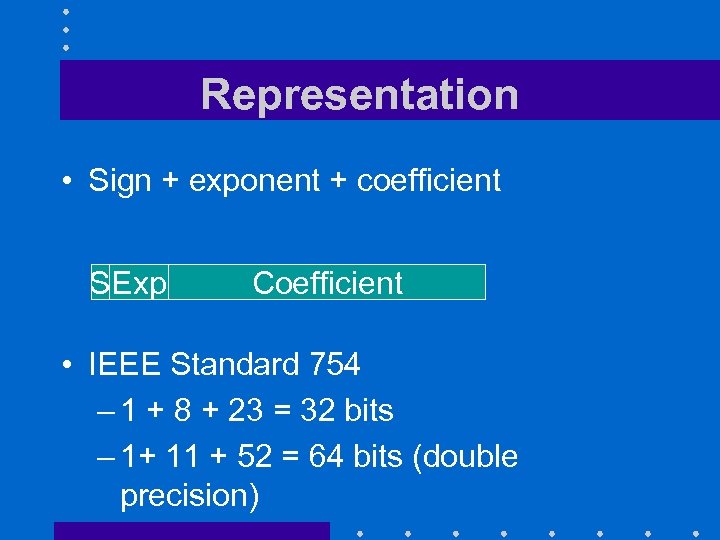

Representation • Sign + exponent + coefficient SExp Coefficient • IEEE Standard 754 – 1 + 8 + 23 = 32 bits – 1+ 11 + 52 = 64 bits (double precision)

Representation • Sign + exponent + coefficient SExp Coefficient • IEEE Standard 754 – 1 + 8 + 23 = 32 bits – 1+ 11 + 52 = 64 bits (double precision)

The sign bit • 0 indicates a positive number • 1 a negative number

The sign bit • 0 indicates a positive number • 1 a negative number

The exponent (I) – 8 bits for single precision – 11 bits for double precision • With 8 bits, we can represent exponents between -126 and + 127 – All-zeroes value is reserved for the zeroes and denormalized numbers – All-ones value are reserved for the infinities and Na. Ns (Not a Number)

The exponent (I) – 8 bits for single precision – 11 bits for double precision • With 8 bits, we can represent exponents between -126 and + 127 – All-zeroes value is reserved for the zeroes and denormalized numbers – All-ones value are reserved for the infinities and Na. Ns (Not a Number)

The exponent (II) • Exponents are represented using a biased notation – Stored value = actual exponent + bias • For 8 bit exponents, bias is 127 – Stored value of 1 corresponds to – 126 – 0 and 255 are reserved for special Stored value of 254 corresponds to values +127

The exponent (II) • Exponents are represented using a biased notation – Stored value = actual exponent + bias • For 8 bit exponents, bias is 127 – Stored value of 1 corresponds to – 126 – 0 and 255 are reserved for special Stored value of 254 corresponds to values +127

The exponent (III) • Biased notation simplifies comparisons: • If two normalized floating point numbers have different exponents, the one with the bigger exponent is the bigger of the two

The exponent (III) • Biased notation simplifies comparisons: • If two normalized floating point numbers have different exponents, the one with the bigger exponent is the bigger of the two

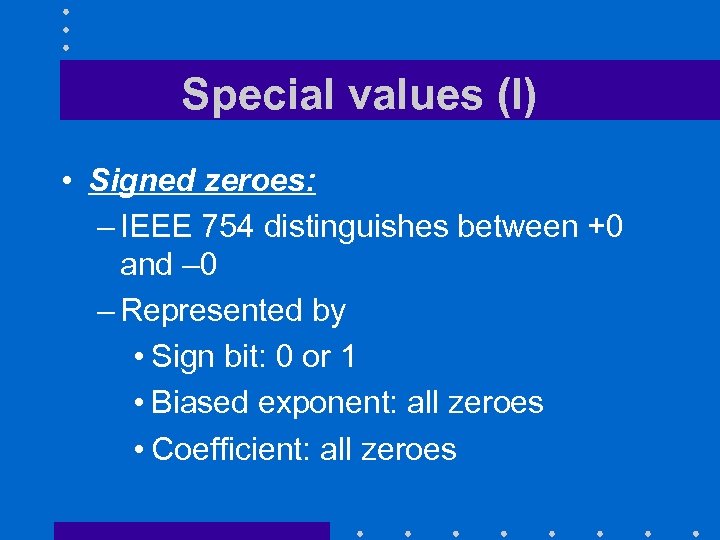

Special values (I) • Signed zeroes: – IEEE 754 distinguishes between +0 and – 0 – Represented by • Sign bit: 0 or 1 • Biased exponent: all zeroes • Coefficient: all zeroes

Special values (I) • Signed zeroes: – IEEE 754 distinguishes between +0 and – 0 – Represented by • Sign bit: 0 or 1 • Biased exponent: all zeroes • Coefficient: all zeroes

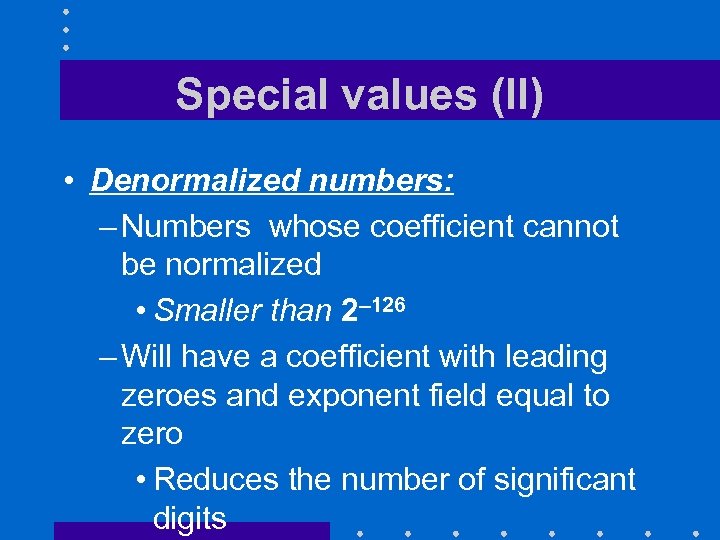

Special values (II) • Denormalized numbers: – Numbers whose coefficient cannot be normalized • Smaller than 2– 126 – Will have a coefficient with leading zeroes and exponent field equal to zero • Reduces the number of significant digits

Special values (II) • Denormalized numbers: – Numbers whose coefficient cannot be normalized • Smaller than 2– 126 – Will have a coefficient with leading zeroes and exponent field equal to zero • Reduces the number of significant digits

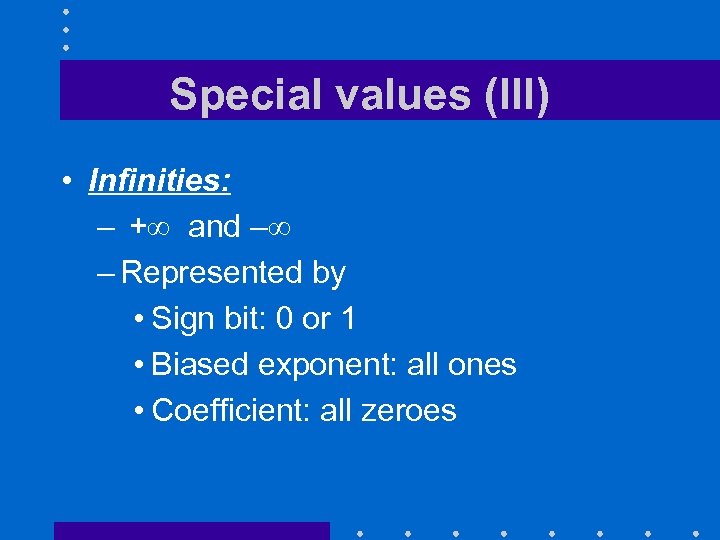

Special values (III) • Infinities: – + and – – Represented by • Sign bit: 0 or 1 • Biased exponent: all ones • Coefficient: all zeroes

Special values (III) • Infinities: – + and – – Represented by • Sign bit: 0 or 1 • Biased exponent: all ones • Coefficient: all zeroes

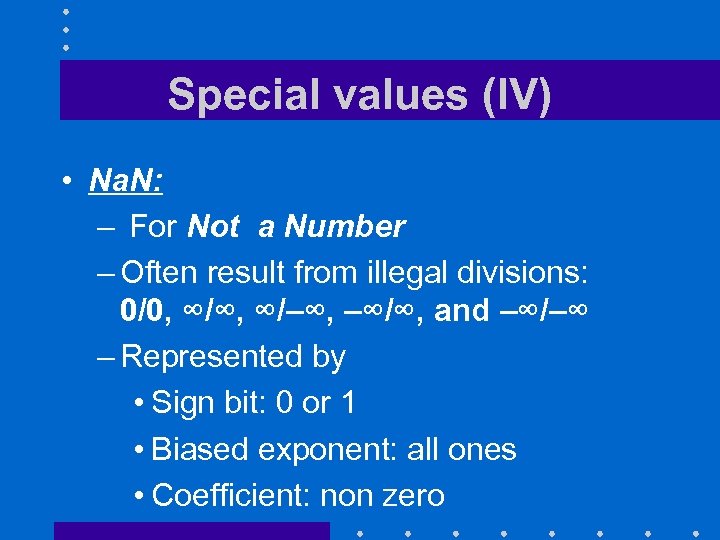

Special values (IV) • Na. N: – For Not a Number – Often result from illegal divisions: 0/0, ∞/∞, ∞/–∞, –∞/∞, and –∞/–∞ – Represented by • Sign bit: 0 or 1 • Biased exponent: all ones • Coefficient: non zero

Special values (IV) • Na. N: – For Not a Number – Often result from illegal divisions: 0/0, ∞/∞, ∞/–∞, –∞/∞, and –∞/–∞ – Represented by • Sign bit: 0 or 1 • Biased exponent: all ones • Coefficient: non zero

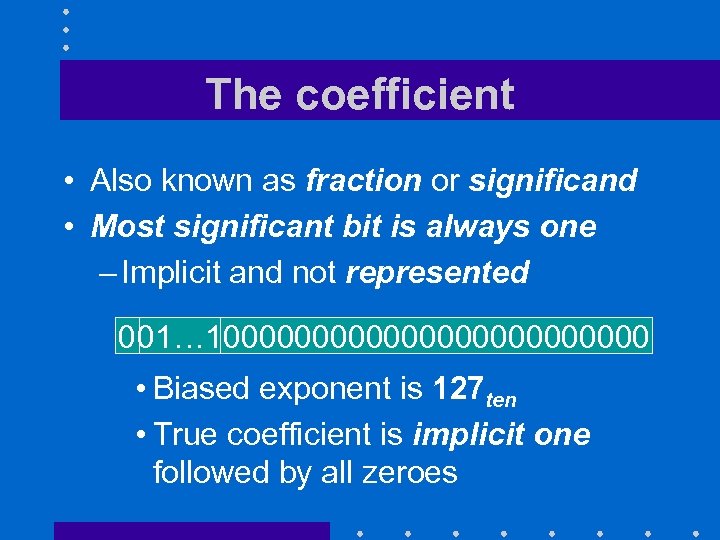

The coefficient • Also known as fraction or significand • Most significant bit is always one – Implicit and not represented 001… 1000000000000 • Biased exponent is 127 ten • True coefficient is implicit one followed by all zeroes

The coefficient • Also known as fraction or significand • Most significant bit is always one – Implicit and not represented 001… 1000000000000 • Biased exponent is 127 ten • True coefficient is implicit one followed by all zeroes

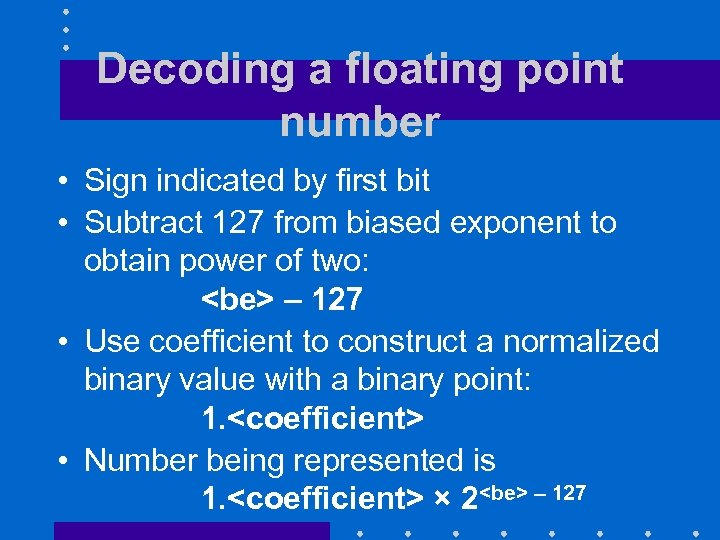

Decoding a floating point number • Sign indicated by first bit • Subtract 127 from biased exponent to obtain power of two:

Decoding a floating point number • Sign indicated by first bit • Subtract 127 from biased exponent to obtain power of two:

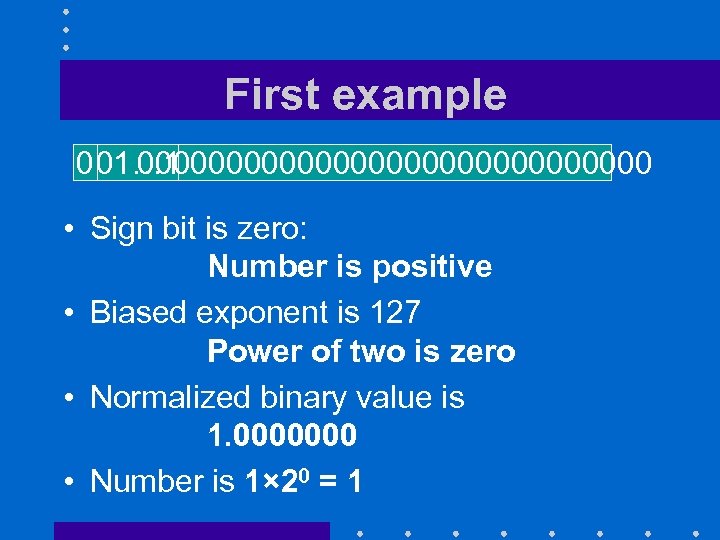

First example 001… 1 000000000000000 • Sign bit is zero: Number is positive • Biased exponent is 127 Power of two is zero • Normalized binary value is 1. 0000000 • Number is 1× 20 = 1

First example 001… 1 000000000000000 • Sign bit is zero: Number is positive • Biased exponent is 127 Power of two is zero • Normalized binary value is 1. 0000000 • Number is 1× 20 = 1

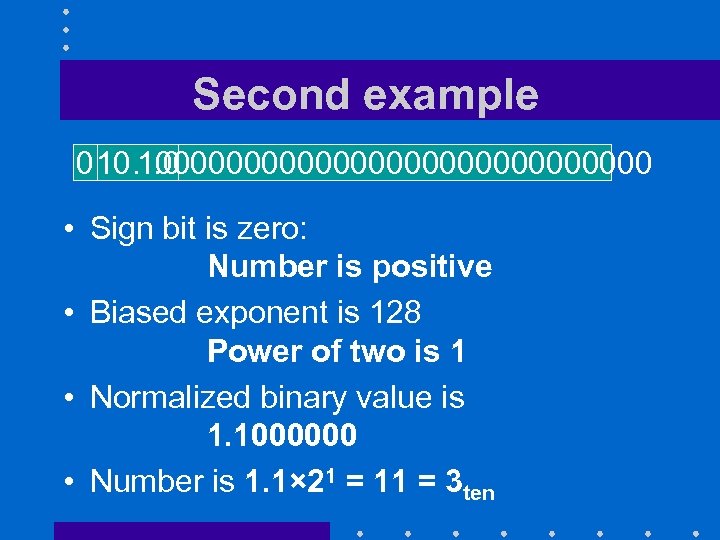

Second example 010… 0 100000000000000 • Sign bit is zero: Number is positive • Biased exponent is 128 Power of two is 1 • Normalized binary value is 1. 1000000 • Number is 1. 1× 21 = 11 = 3 ten

Second example 010… 0 100000000000000 • Sign bit is zero: Number is positive • Biased exponent is 128 Power of two is 1 • Normalized binary value is 1. 1000000 • Number is 1. 1× 21 = 11 = 3 ten

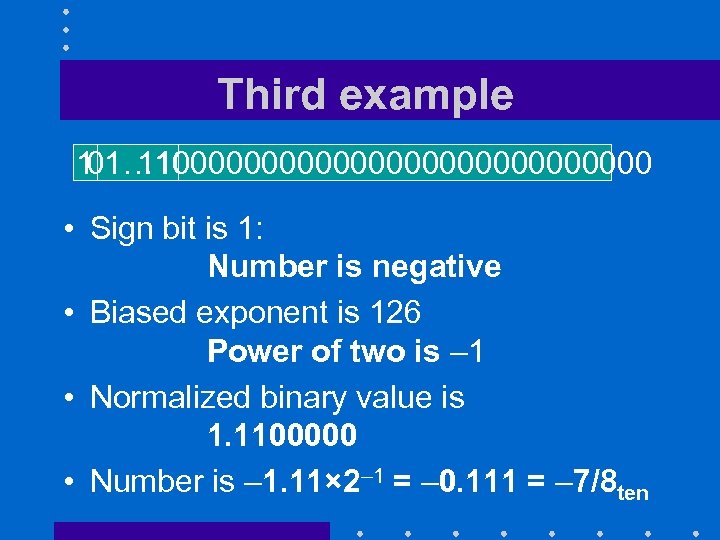

Third example 1 1100000000000000 01… 10 • Sign bit is 1: Number is negative • Biased exponent is 126 Power of two is – 1 • Normalized binary value is 1. 1100000 • Number is – 1. 11× 2– 1 = – 0. 111 = – 7/8 ten

Third example 1 1100000000000000 01… 10 • Sign bit is 1: Number is negative • Biased exponent is 126 Power of two is – 1 • Normalized binary value is 1. 1100000 • Number is – 1. 11× 2– 1 = – 0. 111 = – 7/8 ten

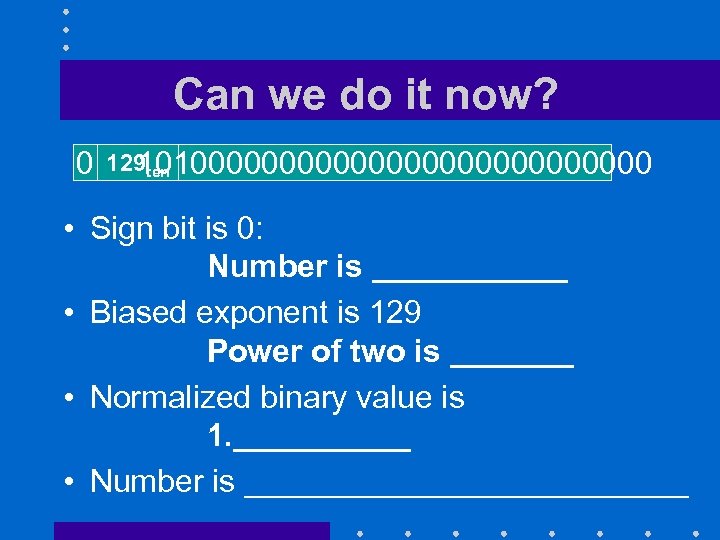

Can we do it now? 0 129 ten 1010000000000000 • Sign bit is 0: Number is ______ • Biased exponent is 129 Power of two is _______ • Normalized binary value is 1. _____ • Number is _____________

Can we do it now? 0 129 ten 1010000000000000 • Sign bit is 0: Number is ______ • Biased exponent is 129 Power of two is _______ • Normalized binary value is 1. _____ • Number is _____________

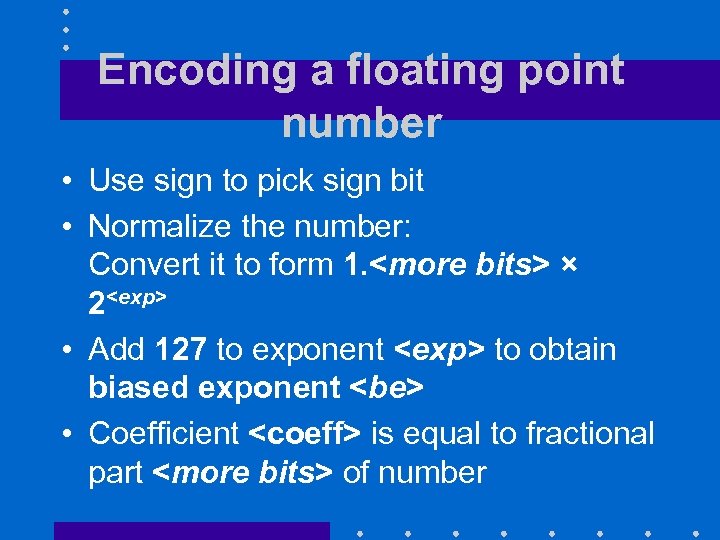

Encoding a floating point number • Use sign to pick sign bit • Normalize the number: Convert it to form 1.

Encoding a floating point number • Use sign to pick sign bit • Normalize the number: Convert it to form 1.

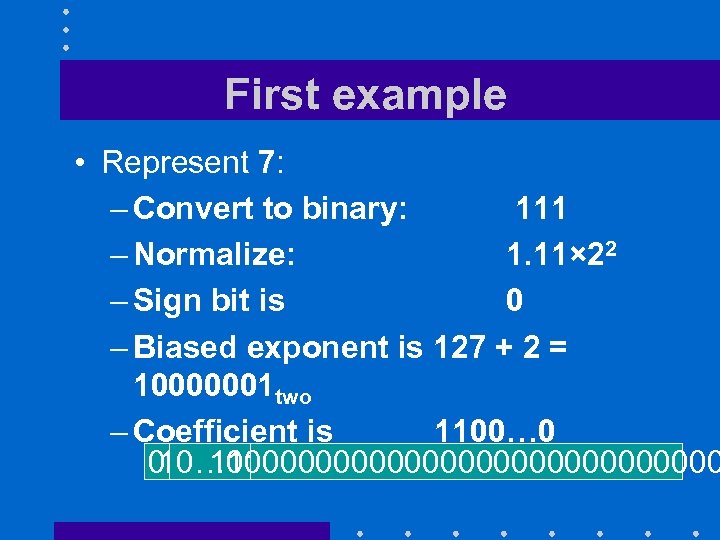

First example • Represent 7: – Convert to binary: 111 – Normalize: 1. 11× 22 – Sign bit is 0 – Biased exponent is 127 + 2 = 10000001 two – Coefficient is 1100… 0 0 1100000000000000 10… 01

First example • Represent 7: – Convert to binary: 111 – Normalize: 1. 11× 22 – Sign bit is 0 – Biased exponent is 127 + 2 = 10000001 two – Coefficient is 1100… 0 0 1100000000000000 10… 01

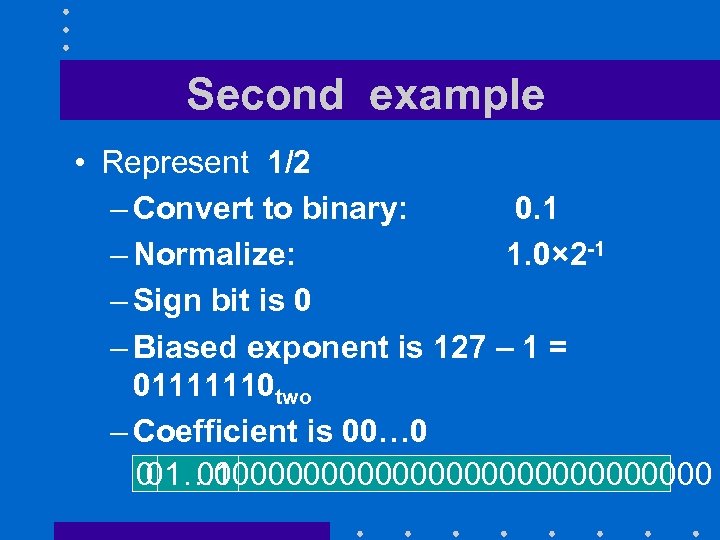

Second example • Represent 1/2 – Convert to binary: 0. 1 – Normalize: 1. 0× 2 -1 – Sign bit is 0 – Biased exponent is 127 – 1 = 01111110 two – Coefficient is 00… 0 0 000000000000000 01… 10

Second example • Represent 1/2 – Convert to binary: 0. 1 – Normalize: 1. 0× 2 -1 – Sign bit is 0 – Biased exponent is 127 – 1 = 01111110 two – Coefficient is 00… 0 0 000000000000000 01… 10

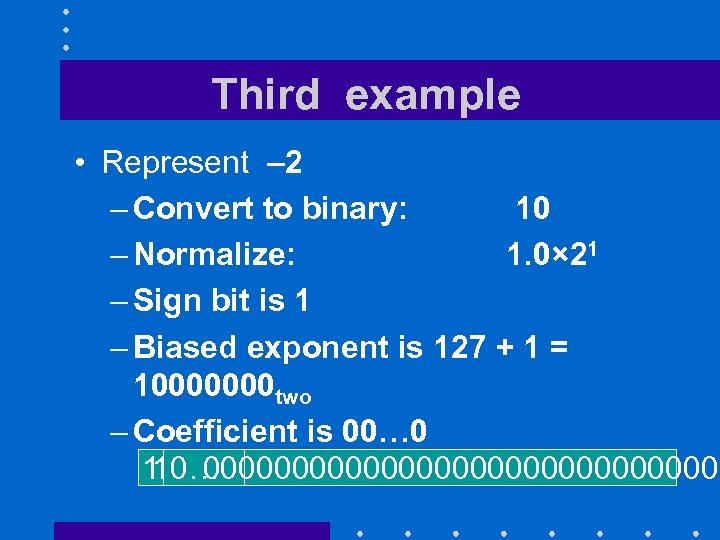

Third example • Represent – 2 – Convert to binary: 10 – Normalize: 1. 0× 21 – Sign bit is 1 – Biased exponent is 127 + 1 = 10000000 two – Coefficient is 00… 0 1 000000000000000 10… 00

Third example • Represent – 2 – Convert to binary: 10 – Normalize: 1. 0× 21 – Sign bit is 1 – Biased exponent is 127 + 1 = 10000000 two – Coefficient is 00… 0 1 000000000000000 10… 00

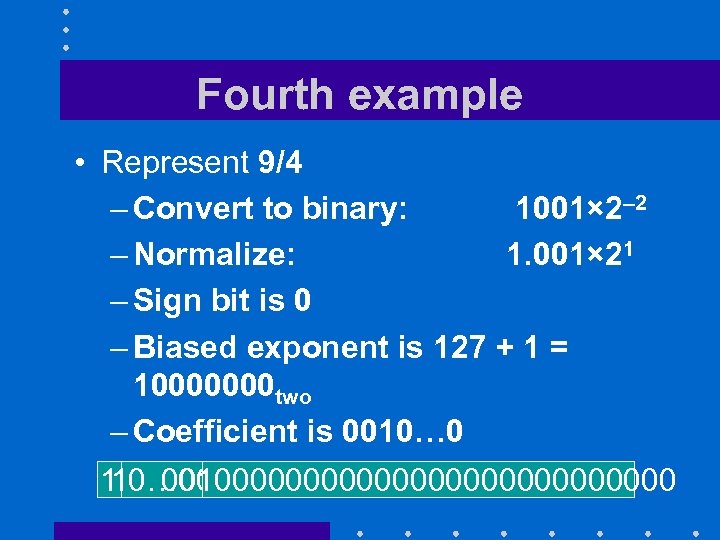

Fourth example • Represent 9/4 – Convert to binary: 1001× 2– 2 – Normalize: 1. 001× 21 – Sign bit is 0 – Biased exponent is 127 + 1 = 10000000 two – Coefficient is 0010… 0 1 0010000000000000 10… 00

Fourth example • Represent 9/4 – Convert to binary: 1001× 2– 2 – Normalize: 1. 001× 21 – Sign bit is 0 – Biased exponent is 127 + 1 = 10000000 two – Coefficient is 0010… 0 1 0010000000000000 10… 00

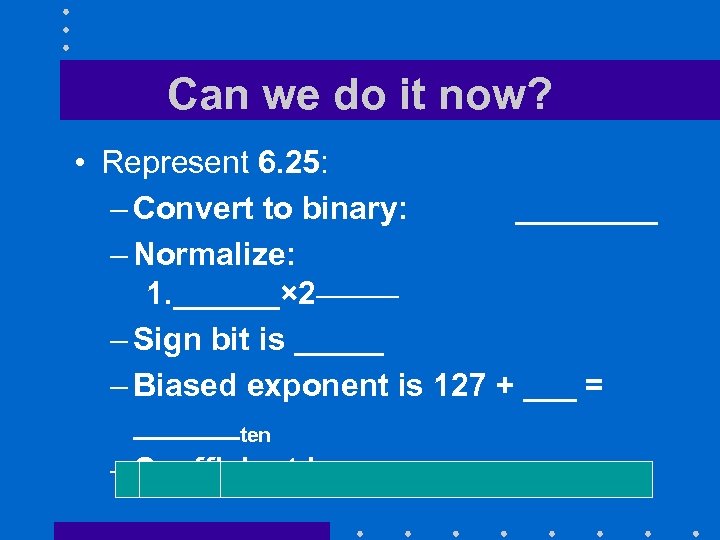

Can we do it now? • Represent 6. 25: – Convert to binary: ____ – Normalize: 1. ______× 2_______ – Sign bit is _____ – Biased exponent is 127 + ___ = ______ten – Coefficient is_____

Can we do it now? • Represent 6. 25: – Convert to binary: ____ – Normalize: 1. ______× 2_______ – Sign bit is _____ – Biased exponent is 127 + ___ = ______ten – Coefficient is_____

Range • Can represent numbers between 1. 00… 0× 2– 126 and 1. 11… 1× 2127 – Say between 2– 126 and 2128 • Observing that 210 103 we divide the exponents by 10 and multiply them by 3 to obtain the interval expressed in powers of 10 – Approximate range is 10– 38 to 1038

Range • Can represent numbers between 1. 00… 0× 2– 126 and 1. 11… 1× 2127 – Say between 2– 126 and 2128 • Observing that 210 103 we divide the exponents by 10 and multiply them by 3 to obtain the interval expressed in powers of 10 – Approximate range is 10– 38 to 1038

Accuracy • We have 24 significant bits – Theoretical precision of 1/224, that is, roughly 1/107 • Cannot add correctly billions or trillions • Actual situation is worse if we do too many computations – 1, 000 – 999, 999. 4875 = ? ? ?

Accuracy • We have 24 significant bits – Theoretical precision of 1/224, that is, roughly 1/107 • Cannot add correctly billions or trillions • Actual situation is worse if we do too many computations – 1, 000 – 999, 999. 4875 = ? ? ?

Guard bits • Do all arithmetic operations with two additional bits to reduce rounding errors

Guard bits • Do all arithmetic operations with two additional bits to reduce rounding errors

Double precision arithmetic (I) • Use 64 -bit double words • Allows us to have – One bit for sign – Eleven bits for exponent • 2, 048 possible values – Fifty-two bits for coefficient • Plus the implicit leading bit

Double precision arithmetic (I) • Use 64 -bit double words • Allows us to have – One bit for sign – Eleven bits for exponent • 2, 048 possible values – Fifty-two bits for coefficient • Plus the implicit leading bit

Double precision arithmetic (II) • Exponents are still represented using a biased notation – Stored value = actual exponent + bias • For 11 -bit exponents, bias is 1023 – Stored value of 1 corresponds to – 1, 022 – Stored value of 2, 046 corresponds to +1, 023

Double precision arithmetic (II) • Exponents are still represented using a biased notation – Stored value = actual exponent + bias • For 11 -bit exponents, bias is 1023 – Stored value of 1 corresponds to – 1, 022 – Stored value of 2, 046 corresponds to +1, 023

Double precision arithmetic (III) • Can now represent numbers between 1. 00… 0× 2– 1, 022 and 1. 11… 1× 21, 203 – Say between 2– 1, 022 and 21, 204 – Approximate range is 10– 307 to 10307 • In reality, more like 10– 308 to 10308

Double precision arithmetic (III) • Can now represent numbers between 1. 00… 0× 2– 1, 022 and 1. 11… 1× 21, 203 – Say between 2– 1, 022 and 21, 204 – Approximate range is 10– 307 to 10307 • In reality, more like 10– 308 to 10308

Double precision arithmetic (IV) • We now have 53 significant bits – Theoretical precision of 1/253. that is, roughly 1/1016 • Can now add correctly billions or trillions

Double precision arithmetic (IV) • We now have 53 significant bits – Theoretical precision of 1/253. that is, roughly 1/1016 • Can now add correctly billions or trillions

If that is now enough, … • Can use 128 -bit quad words • Allows us to have – One bit for sign – Fifteen bits for exponent • From – 16382 to +16383 – One hundred twelve bits for coefficient • Plus the implicit leading bit

If that is now enough, … • Can use 128 -bit quad words • Allows us to have – One bit for sign – Fifteen bits for exponent • From – 16382 to +16383 – One hundred twelve bits for coefficient • Plus the implicit leading bit

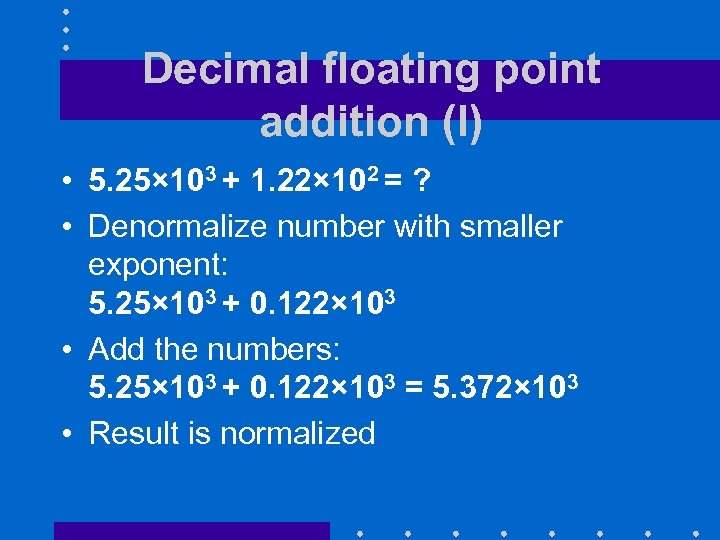

Decimal floating point addition (I) • 5. 25× 103 + 1. 22× 102 = ? • Denormalize number with smaller exponent: 5. 25× 103 + 0. 122× 103 • Add the numbers: 5. 25× 103 + 0. 122× 103 = 5. 372× 103 • Result is normalized

Decimal floating point addition (I) • 5. 25× 103 + 1. 22× 102 = ? • Denormalize number with smaller exponent: 5. 25× 103 + 0. 122× 103 • Add the numbers: 5. 25× 103 + 0. 122× 103 = 5. 372× 103 • Result is normalized

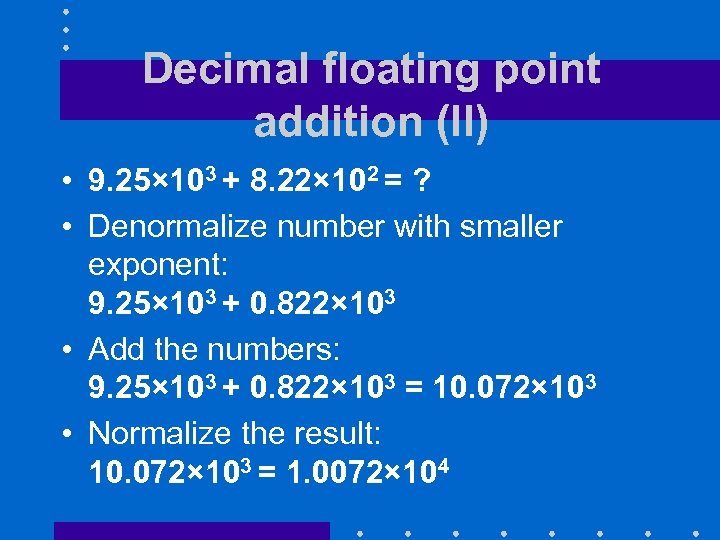

Decimal floating point addition (II) • 9. 25× 103 + 8. 22× 102 = ? • Denormalize number with smaller exponent: 9. 25× 103 + 0. 822× 103 • Add the numbers: 9. 25× 103 + 0. 822× 103 = 10. 072× 103 • Normalize the result: 10. 072× 103 = 1. 0072× 104

Decimal floating point addition (II) • 9. 25× 103 + 8. 22× 102 = ? • Denormalize number with smaller exponent: 9. 25× 103 + 0. 822× 103 • Add the numbers: 9. 25× 103 + 0. 822× 103 = 10. 072× 103 • Normalize the result: 10. 072× 103 = 1. 0072× 104

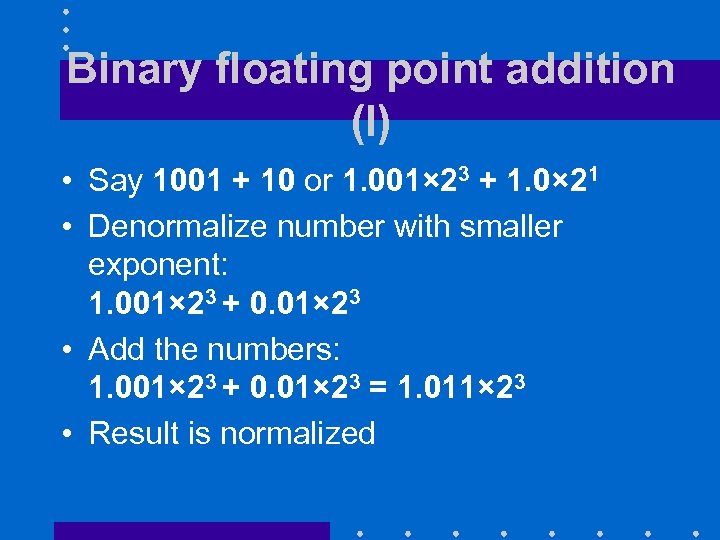

Binary floating point addition (I) • Say 1001 + 10 or 1. 001× 23 + 1. 0× 21 • Denormalize number with smaller exponent: 1. 001× 23 + 0. 01× 23 • Add the numbers: 1. 001× 23 + 0. 01× 23 = 1. 011× 23 • Result is normalized

Binary floating point addition (I) • Say 1001 + 10 or 1. 001× 23 + 1. 0× 21 • Denormalize number with smaller exponent: 1. 001× 23 + 0. 01× 23 • Add the numbers: 1. 001× 23 + 0. 01× 23 = 1. 011× 23 • Result is normalized

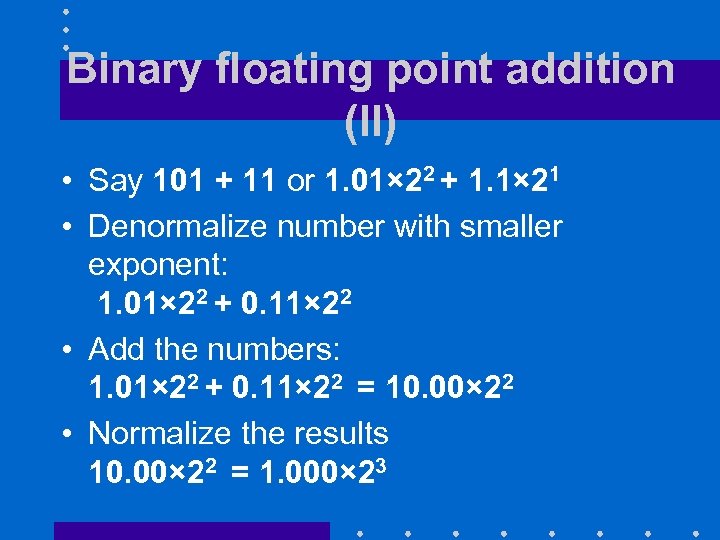

Binary floating point addition (II) • Say 101 + 11 or 1. 01× 22 + 1. 1× 21 • Denormalize number with smaller exponent: 1. 01× 22 + 0. 11× 22 • Add the numbers: 1. 01× 22 + 0. 11× 22 = 10. 00× 22 • Normalize the results 10. 00× 22 = 1. 000× 23

Binary floating point addition (II) • Say 101 + 11 or 1. 01× 22 + 1. 1× 21 • Denormalize number with smaller exponent: 1. 01× 22 + 0. 11× 22 • Add the numbers: 1. 01× 22 + 0. 11× 22 = 10. 00× 22 • Normalize the results 10. 00× 22 = 1. 000× 23

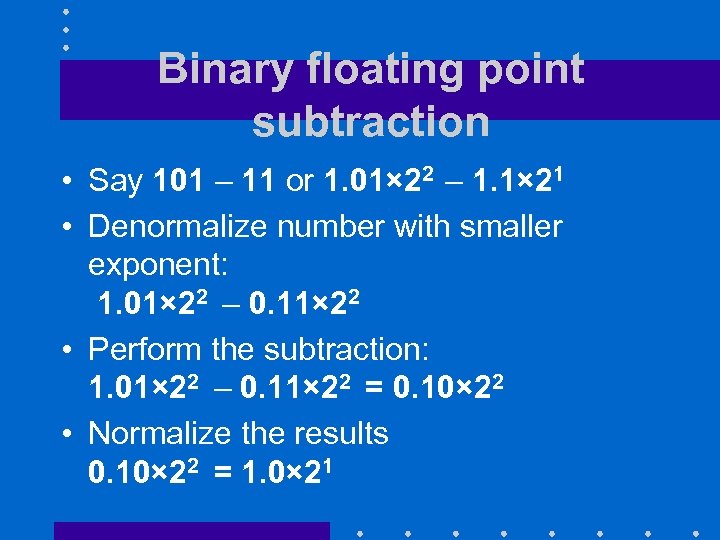

Binary floating point subtraction • Say 101 – 11 or 1. 01× 22 – 1. 1× 21 • Denormalize number with smaller exponent: 1. 01× 22 – 0. 11× 22 • Perform the subtraction: 1. 01× 22 – 0. 11× 22 = 0. 10× 22 • Normalize the results 0. 10× 22 = 1. 0× 21

Binary floating point subtraction • Say 101 – 11 or 1. 01× 22 – 1. 1× 21 • Denormalize number with smaller exponent: 1. 01× 22 – 0. 11× 22 • Perform the subtraction: 1. 01× 22 – 0. 11× 22 = 0. 10× 22 • Normalize the results 0. 10× 22 = 1. 0× 21

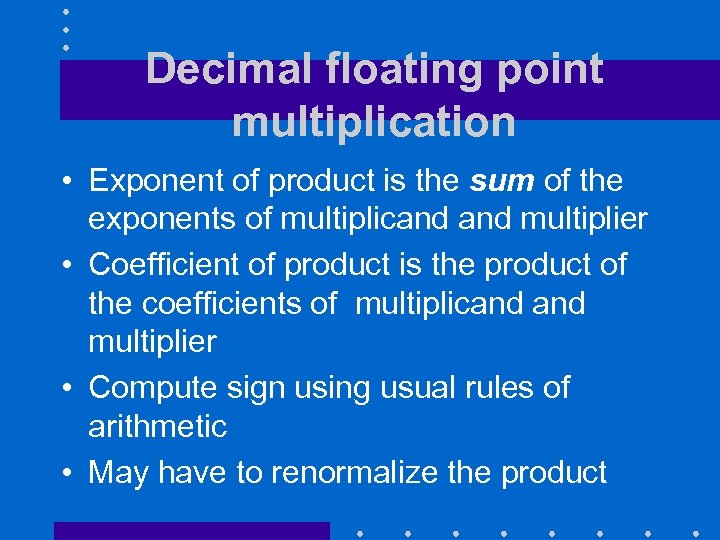

Decimal floating point multiplication • Exponent of product is the sum of the exponents of multiplicand multiplier • Coefficient of product is the product of the coefficients of multiplicand multiplier • Compute sign using usual rules of arithmetic • May have to renormalize the product

Decimal floating point multiplication • Exponent of product is the sum of the exponents of multiplicand multiplier • Coefficient of product is the product of the coefficients of multiplicand multiplier • Compute sign using usual rules of arithmetic • May have to renormalize the product

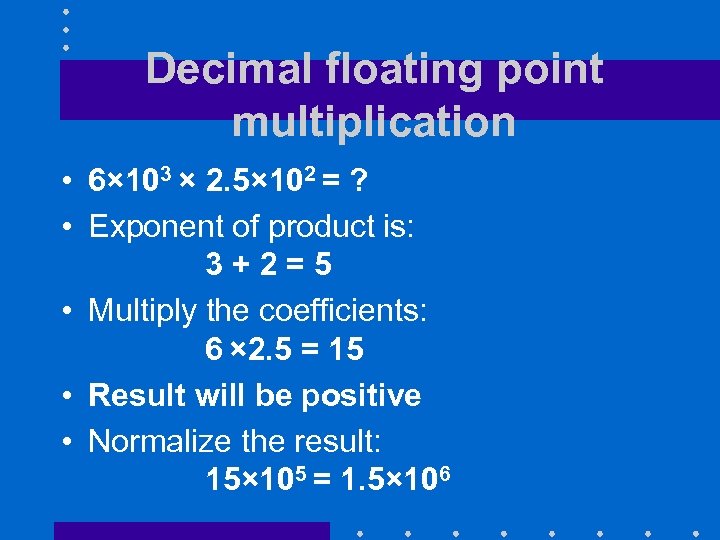

Decimal floating point multiplication • 6× 103 × 2. 5× 102 = ? • Exponent of product is: 3+2=5 • Multiply the coefficients: 6 × 2. 5 = 15 • Result will be positive • Normalize the result: 15× 105 = 1. 5× 106

Decimal floating point multiplication • 6× 103 × 2. 5× 102 = ? • Exponent of product is: 3+2=5 • Multiply the coefficients: 6 × 2. 5 = 15 • Result will be positive • Normalize the result: 15× 105 = 1. 5× 106

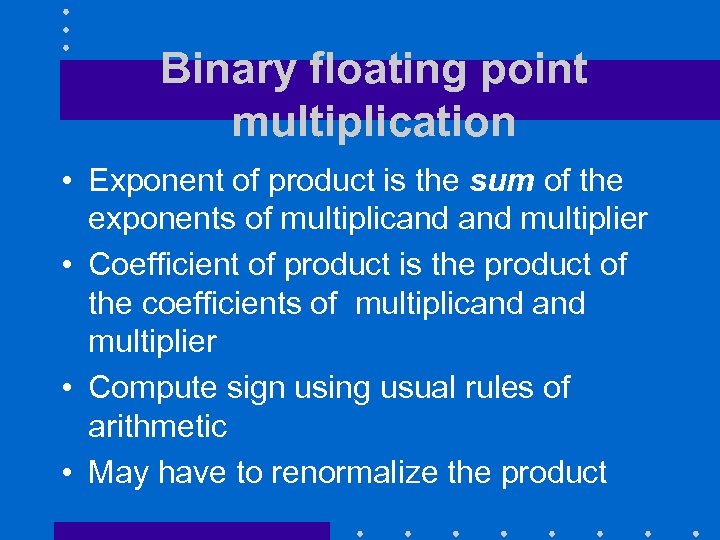

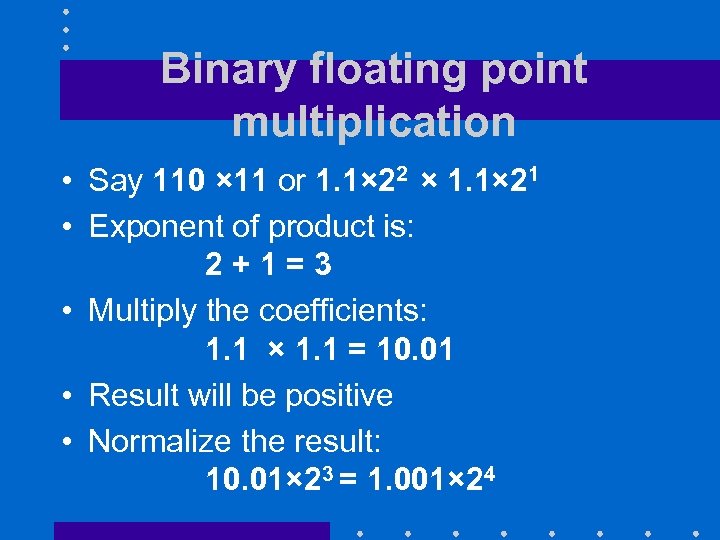

Binary floating point multiplication • Exponent of product is the sum of the exponents of multiplicand multiplier • Coefficient of product is the product of the coefficients of multiplicand multiplier • Compute sign using usual rules of arithmetic • May have to renormalize the product

Binary floating point multiplication • Exponent of product is the sum of the exponents of multiplicand multiplier • Coefficient of product is the product of the coefficients of multiplicand multiplier • Compute sign using usual rules of arithmetic • May have to renormalize the product

Binary floating point multiplication • Say 110 × 11 or 1. 1× 22 × 1. 1× 21 • Exponent of product is: 2+1=3 • Multiply the coefficients: 1. 1 × 1. 1 = 10. 01 • Result will be positive • Normalize the result: 10. 01× 23 = 1. 001× 24

Binary floating point multiplication • Say 110 × 11 or 1. 1× 22 × 1. 1× 21 • Exponent of product is: 2+1=3 • Multiply the coefficients: 1. 1 × 1. 1 = 10. 01 • Result will be positive • Normalize the result: 10. 01× 23 = 1. 001× 24

FP division • Very tricky • One good solution is to multiply the dividend by the inverse of the divisor

FP division • Very tricky • One good solution is to multiply the dividend by the inverse of the divisor

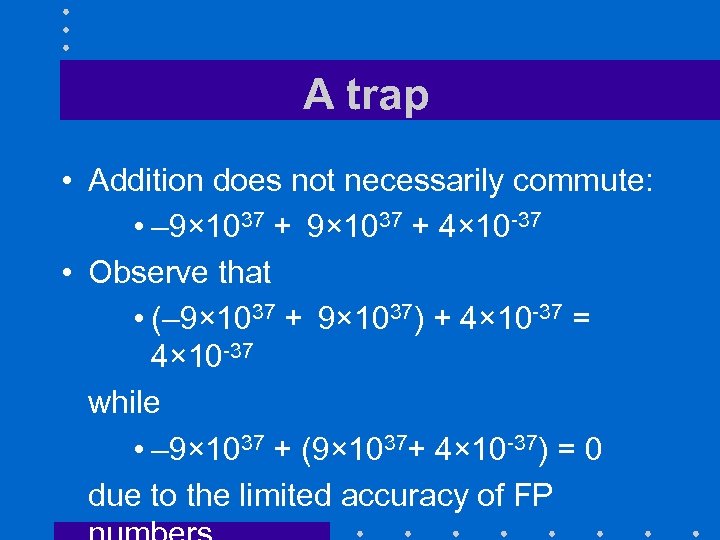

A trap • Addition does not necessarily commute: • – 9× 1037 + 4× 10 -37 • Observe that • (– 9× 1037 + 9× 1037) + 4× 10 -37 = 4× 10 -37 while • – 9× 1037 + (9× 1037+ 4× 10 -37) = 0 due to the limited accuracy of FP

A trap • Addition does not necessarily commute: • – 9× 1037 + 4× 10 -37 • Observe that • (– 9× 1037 + 9× 1037) + 4× 10 -37 = 4× 10 -37 while • – 9× 1037 + (9× 1037+ 4× 10 -37) = 0 due to the limited accuracy of FP

IMPLEMENTATIONS

IMPLEMENTATIONS

The floating-point unit (I) • Floating-point instructions were an optional feature – User had to buy a separate floatingpoint unit aka floating point coprocessor • Before Intel 80486, all Intel x 86 architectures the option to install a separate floating-point chip(8087, 80287, 80387)

The floating-point unit (I) • Floating-point instructions were an optional feature – User had to buy a separate floatingpoint unit aka floating point coprocessor • Before Intel 80486, all Intel x 86 architectures the option to install a separate floating-point chip(8087, 80287, 80387)

The floating-point unit (II) • Default solution was to simulate the missing floating-point instructions through assembly routines • As a result, many processor architectures use separate banks of registers for integer arithmetic and floating point arithmetic

The floating-point unit (II) • Default solution was to simulate the missing floating-point instructions through assembly routines • As a result, many processor architectures use separate banks of registers for integer arithmetic and floating point arithmetic

The floating-point unit (III) • Some older architectures implemented – Single-precision operations in hardware through the FPU – Double-precision operations by software • Made double-precession operations much costlier than single-precision operations.

The floating-point unit (III) • Some older architectures implemented – Single-precision operations in hardware through the FPU – Double-precision operations by software • Made double-precession operations much costlier than single-precision operations.

IBM 360 FP INSTRUCTIONS

IBM 360 FP INSTRUCTIONS

Overview • FPU offers a very familiar user interface – Eight general purpose FP registers • Distinct from the integer registers – Two-operand instructions in both RR and RX formats • Includes single-precision and doubleprecision versions or addition, subtraction, multiplication and division

Overview • FPU offers a very familiar user interface – Eight general purpose FP registers • Distinct from the integer registers – Two-operand instructions in both RR and RX formats • Includes single-precision and doubleprecision versions or addition, subtraction, multiplication and division

Examples of RR instructions • AFR f 1, f 2 add contents of floatingpoint register f 2 into f 1 • ADR f 1, f 2 add contents of doubleprecision register f 2 into f 1 • LFR f 1, f 2 load contents of floatingpoint register f 2 into f 1 • Also had load positive, load negative, load complement instructions for floating -point and double-precision operands

Examples of RR instructions • AFR f 1, f 2 add contents of floatingpoint register f 2 into f 1 • ADR f 1, f 2 add contents of doubleprecision register f 2 into f 1 • LFR f 1, f 2 load contents of floatingpoint register f 2 into f 1 • Also had load positive, load negative, load complement instructions for floating -point and double-precision operands

Examples of RX instructions • AF r 1, d(r 2) add contents of word at address d + contents(r 2) into register r 1 • AD r 1, d(r 2) …

Examples of RX instructions • AF r 1, d(r 2) add contents of word at address d + contents(r 2) into register r 1 • AD r 1, d(r 2) …

MIPS FP INSTRUCTIONS

MIPS FP INSTRUCTIONS

Overview • Thirty-two specialized single-precision registers: $f 0, $f 1, … $f 31 • Each pair of single-precision registers forms a double-precision register • *. s instructions apply to single precision format • *. d instructions apply to double precision format

Overview • Thirty-two specialized single-precision registers: $f 0, $f 1, … $f 31 • Each pair of single-precision registers forms a double-precision register • *. s instructions apply to single precision format • *. d instructions apply to double precision format

R-format instructions (I) • add. s f 1, f 2, f 3 f 1 = r 2 + f 3 (single precision) • add. d f 2, f 4, f 6 (f 2, f 2+1) = (f 4, f 4+1) + (f 6, f 6 +1) (double precision applies to register pairs) • sub. s f 1, f 2, f 3 f 1 = f 2 – f 3 (single precision) • sub. d f 2, f 4, f 6 (double precision)

R-format instructions (I) • add. s f 1, f 2, f 3 f 1 = r 2 + f 3 (single precision) • add. d f 2, f 4, f 6 (f 2, f 2+1) = (f 4, f 4+1) + (f 6, f 6 +1) (double precision applies to register pairs) • sub. s f 1, f 2, f 3 f 1 = f 2 – f 3 (single precision) • sub. d f 2, f 4, f 6 (double precision)

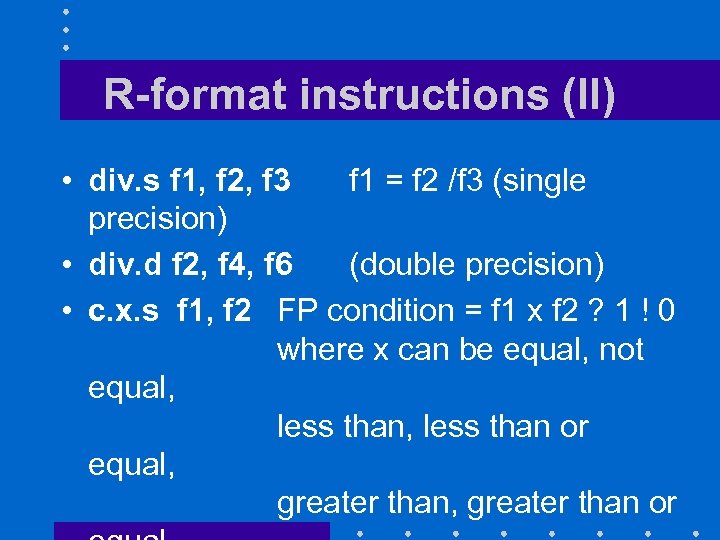

R-format instructions (II) • div. s f 1, f 2, f 3 f 1 = f 2 /f 3 (single precision) • div. d f 2, f 4, f 6 (double precision) • c. x. s f 1, f 2 FP condition = f 1 x f 2 ? 1 ! 0 where x can be equal, not equal, less than or equal, greater than or

R-format instructions (II) • div. s f 1, f 2, f 3 f 1 = f 2 /f 3 (single precision) • div. d f 2, f 4, f 6 (double precision) • c. x. s f 1, f 2 FP condition = f 1 x f 2 ? 1 ! 0 where x can be equal, not equal, less than or equal, greater than or

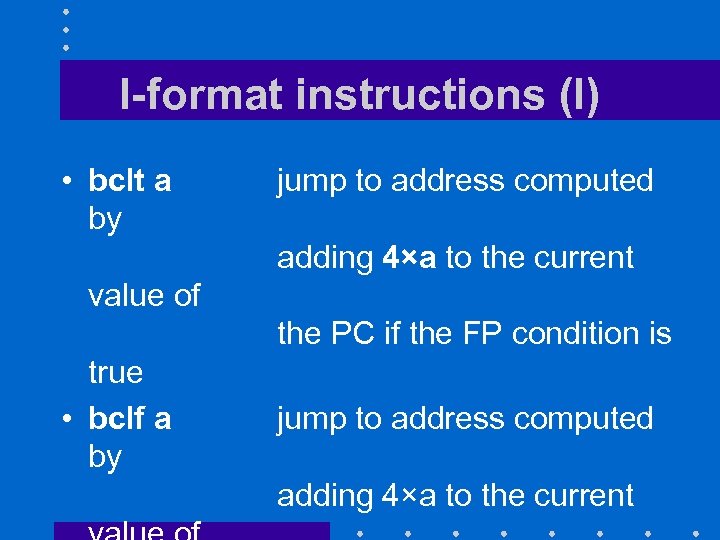

I-format instructions (I) • bclt a by jump to address computed adding 4×a to the current value of the PC if the FP condition is true • bclf a by jump to address computed adding 4×a to the current

I-format instructions (I) • bclt a by jump to address computed adding 4×a to the current value of the PC if the FP condition is true • bclf a by jump to address computed adding 4×a to the current

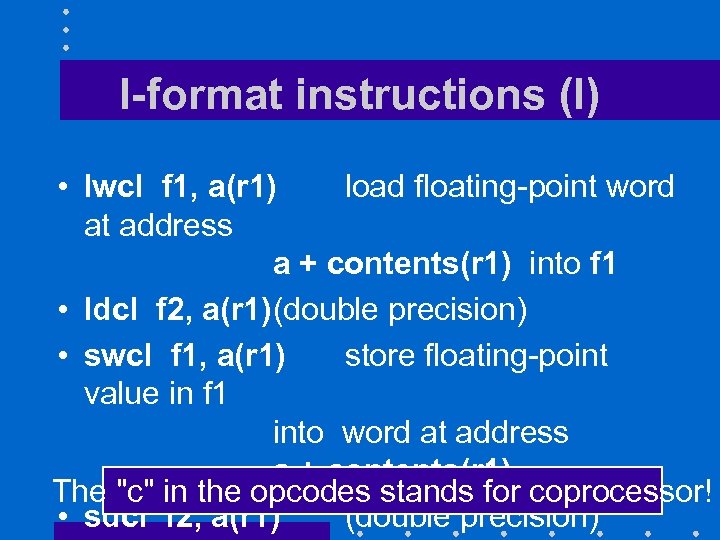

I-format instructions (I) • lwcl f 1, a(r 1) load floating-point word at address a + contents(r 1) into f 1 • ldcl f 2, a(r 1)(double precision) • swcl f 1, a(r 1) store floating-point value in f 1 into word at address a + contents(r 1) The "c" in the opcodes stands for coprocessor! • sdcl f 2, a(r 1) (double precision)

I-format instructions (I) • lwcl f 1, a(r 1) load floating-point word at address a + contents(r 1) into f 1 • ldcl f 2, a(r 1)(double precision) • swcl f 1, a(r 1) store floating-point value in f 1 into word at address a + contents(r 1) The "c" in the opcodes stands for coprocessor! • sdcl f 2, a(r 1) (double precision)

x 86 FP INSTRUCTIONS

x 86 FP INSTRUCTIONS

Overview • Original x 86 FP coprocessor had a stack architecture • Stack registers were 80 -bit wide as well as all internal registers – Better accuracy • Provided single and double precision operations

Overview • Original x 86 FP coprocessor had a stack architecture • Stack registers were 80 -bit wide as well as all internal registers – Better accuracy • Provided single and double precision operations

Stack operations (I) • Three types of operations: – Loads store an operand on the top of the stack – Arithmetic and comparison operations find two operands of the top of the stack and replace them by the result of the operation – Stores move the top of stack register into memory

Stack operations (I) • Three types of operations: – Loads store an operand on the top of the stack – Arithmetic and comparison operations find two operands of the top of the stack and replace them by the result of the operation – Stores move the top of stack register into memory

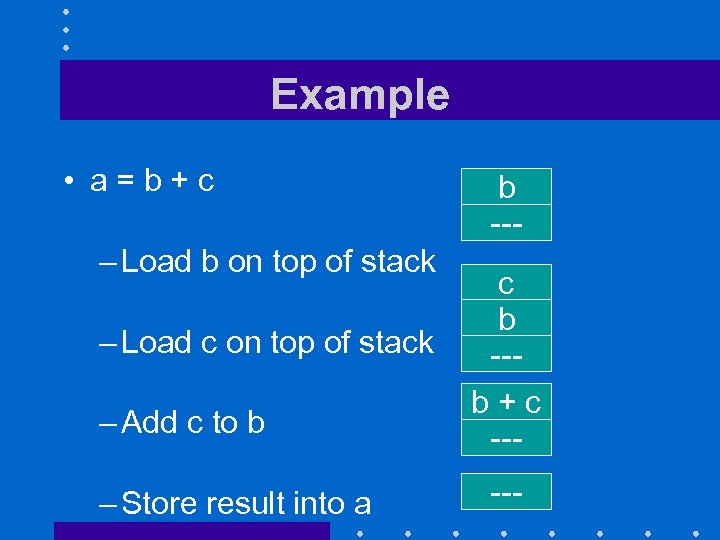

Example • a=b+c – Load b on top of stack – Load c on top of stack – Add c to b – Store result into a b --c b --b+c -----

Example • a=b+c – Load b on top of stack – Load c on top of stack – Add c to b – Store result into a b --c b --b+c -----

Stack operations (II) • Instruction set also allowed – Operations on top of stack register and the ith register below – Immediate operands – Operations on top of stack register and a memory location • Poor performance of FP unit architecture motivated an extension to the x 86 instruction set

Stack operations (II) • Instruction set also allowed – Operations on top of stack register and the ith register below – Immediate operands – Operations on top of stack register and a memory location • Poor performance of FP unit architecture motivated an extension to the x 86 instruction set

Intel SSE 2 FP Architecture (I) • SSE 2 Extension (2001) provided 8 floating point registers – Could hold either single precision or double precision values – Number extended to 16 by AMD, followed by Intel

Intel SSE 2 FP Architecture (I) • SSE 2 Extension (2001) provided 8 floating point registers – Could hold either single precision or double precision values – Number extended to 16 by AMD, followed by Intel

Intel SSE 2 FP Architecture (II) • Registers are now 128 -bit wide Wow! – Can hold • One quad precision value • Two double precision values • Four single precision values • Can perform same operation in parallel on all single/double precision values stored in the same register

Intel SSE 2 FP Architecture (II) • Registers are now 128 -bit wide Wow! – Can hold • One quad precision value • Two double precision values • Four single precision values • Can perform same operation in parallel on all single/double precision values stored in the same register

REVIEW QUESTIONS

REVIEW QUESTIONS

Review questions • How would you represent 0. 5 in double precision? • How would you convert this doubleprecision value into a single precision format? • When doing accounting, we could do all the computations in cents using integer arithmetic. What would we win? What

Review questions • How would you represent 0. 5 in double precision? • How would you convert this doubleprecision value into a single precision format? • When doing accounting, we could do all the computations in cents using integer arithmetic. What would we win? What

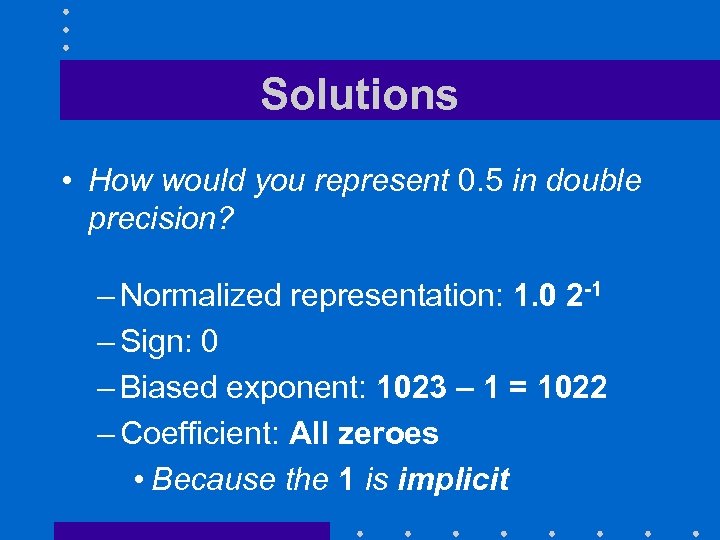

Solutions • How would you represent 0. 5 in double precision? – Normalized representation: 1. 0 2 -1 – Sign: 0 – Biased exponent: 1023 – 1 = 1022 – Coefficient: All zeroes • Because the 1 is implicit

Solutions • How would you represent 0. 5 in double precision? – Normalized representation: 1. 0 2 -1 – Sign: 0 – Biased exponent: 1023 – 1 = 1022 – Coefficient: All zeroes • Because the 1 is implicit

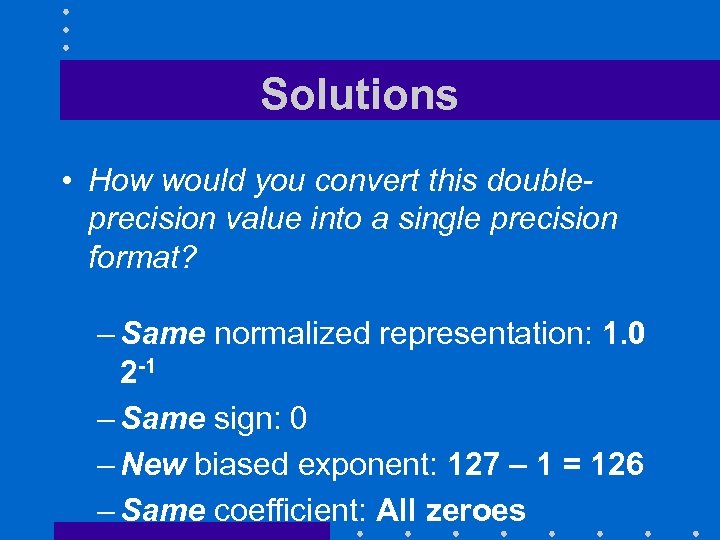

Solutions • How would you convert this doubleprecision value into a single precision format? – Same normalized representation: 1. 0 2 -1 – Same sign: 0 – New biased exponent: 127 – 1 = 126 – Same coefficient: All zeroes

Solutions • How would you convert this doubleprecision value into a single precision format? – Same normalized representation: 1. 0 2 -1 – Same sign: 0 – New biased exponent: 127 – 1 = 126 – Same coefficient: All zeroes

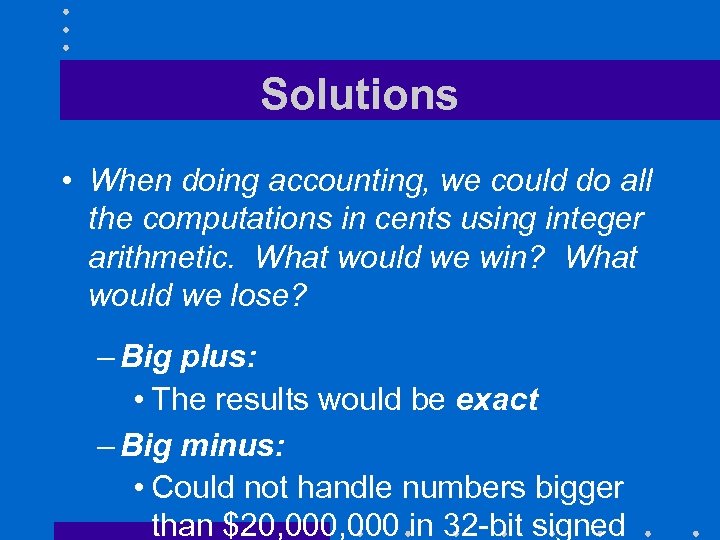

Solutions • When doing accounting, we could do all the computations in cents using integer arithmetic. What would we win? What would we lose? – Big plus: • The results would be exact – Big minus: • Could not handle numbers bigger than $20, 000 in 32 -bit signed

Solutions • When doing accounting, we could do all the computations in cents using integer arithmetic. What would we win? What would we lose? – Big plus: • The results would be exact – Big minus: • Could not handle numbers bigger than $20, 000 in 32 -bit signed

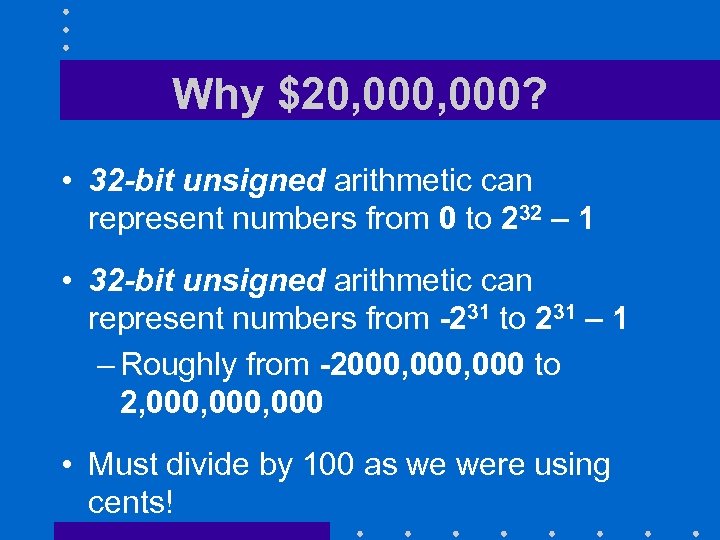

Why $20, 000? • 32 -bit unsigned arithmetic can represent numbers from 0 to 232 – 1 • 32 -bit unsigned arithmetic can represent numbers from -231 to 231 – Roughly from -2000, 000 to 2, 000, 000 • Must divide by 100 as we were using cents!

Why $20, 000? • 32 -bit unsigned arithmetic can represent numbers from 0 to 232 – 1 • 32 -bit unsigned arithmetic can represent numbers from -231 to 231 – Roughly from -2000, 000 to 2, 000, 000 • Must divide by 100 as we were using cents!

TRANSITION SLIDE • Here end the materials that were on the first fall 2012 midterm

TRANSITION SLIDE • Here end the materials that were on the first fall 2012 midterm