c5c82a7bf041dfb68cacdb55efc0ad8f.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 70

Complexity Theory Lecture 10 Lecturer: Moni Naor

Complexity Theory Lecture 10 Lecturer: Moni Naor

![Recap Last week: IP=PSPACE Start with #P in PSPACE Public vs. Private Coins IP[k]=AM Recap Last week: IP=PSPACE Start with #P in PSPACE Public vs. Private Coins IP[k]=AM](https://present5.com/presentation/c5c82a7bf041dfb68cacdb55efc0ad8f/image-2.jpg) Recap Last week: IP=PSPACE Start with #P in PSPACE Public vs. Private Coins IP[k]=AM Mechanism for showing non NP-Completeness This Week: Statistical zero-knowledge AM protocol for VC dimension Hardness and Randomness

Recap Last week: IP=PSPACE Start with #P in PSPACE Public vs. Private Coins IP[k]=AM Mechanism for showing non NP-Completeness This Week: Statistical zero-knowledge AM protocol for VC dimension Hardness and Randomness

Lack of certificate Bug or feature? Disadvantages clear, but: • Advantage: proof remains `property’ of prover and not automatically shared with verifier • Very important in cryptographic applications – Zero-knowledge Honest verifier perfect zero-knowledge • Many variants • Can be used to transform any protocol designed to work with benign players into one working with malicious ones – The computational variant is useful for this purpose • Can be used to obtain (plausible) deniability

Lack of certificate Bug or feature? Disadvantages clear, but: • Advantage: proof remains `property’ of prover and not automatically shared with verifier • Very important in cryptographic applications – Zero-knowledge Honest verifier perfect zero-knowledge • Many variants • Can be used to transform any protocol designed to work with benign players into one working with malicious ones – The computational variant is useful for this purpose • Can be used to obtain (plausible) deniability

Perfect or Statistical Zero-Knowledge An interactive protocol for proving that x 2 L is honest verifier perfect zero-knowledgeif for all x 2 L: there exists a probabilistic polynomial time simulator S such that S(x) generates an output identically distributedto the verifier’s view in a real execution: – transcript of (P, V) conversation – the random bits used by the verifier • assume no erasures, otherwise can get it trivially If the distributions are nearly identical – Statistical Zero-Knowledge Variation distance is negligible in program size Example: the protocol for GNI is honest verifier perfect zero-knowledge. The transcript consist of a graph H graph and a bit r The simulator: given (G 0, G 1) Pick random c 2 R {0, 1} and 2 R S|V| Output simulated view: transcript h. H = (Gc), r=ci random string: hc, i The distribution is identical to the one generated by an honest verifier Some precautions need to be taken if the verifier might not be following the protocol

Perfect or Statistical Zero-Knowledge An interactive protocol for proving that x 2 L is honest verifier perfect zero-knowledgeif for all x 2 L: there exists a probabilistic polynomial time simulator S such that S(x) generates an output identically distributedto the verifier’s view in a real execution: – transcript of (P, V) conversation – the random bits used by the verifier • assume no erasures, otherwise can get it trivially If the distributions are nearly identical – Statistical Zero-Knowledge Variation distance is negligible in program size Example: the protocol for GNI is honest verifier perfect zero-knowledge. The transcript consist of a graph H graph and a bit r The simulator: given (G 0, G 1) Pick random c 2 R {0, 1} and 2 R S|V| Output simulated view: transcript h. H = (Gc), r=ci random string: hc, i The distribution is identical to the one generated by an honest verifier Some precautions need to be taken if the verifier might not be following the protocol

Detour: Authentication One of the fundamental tasks of cryptography • Alice (sender) wants to send a message m to Bob (receiver). • They want to prevent Eve from interfering – Bob should be sure that the message he receives is indeed the message m Alice sent. Alice Bob Eve

Detour: Authentication One of the fundamental tasks of cryptography • Alice (sender) wants to send a message m to Bob (receiver). • They want to prevent Eve from interfering – Bob should be sure that the message he receives is indeed the message m Alice sent. Alice Bob Eve

![Authentication and Non-Repudiation • Key idea of modern cryptography [Diffie-Hellman]: can make authentication (signatures) Authentication and Non-Repudiation • Key idea of modern cryptography [Diffie-Hellman]: can make authentication (signatures)](https://present5.com/presentation/c5c82a7bf041dfb68cacdb55efc0ad8f/image-6.jpg) Authentication and Non-Repudiation • Key idea of modern cryptography [Diffie-Hellman]: can make authentication (signatures) transferable to third party - Non-repudiation. – Essential to contract signing, e-commerce… • Digital Signatures: last 25 years major effort in – Research • Notions of security • Computationally efficient constructions – Technology, Infrastructure (PKI), Commerce, Legal

Authentication and Non-Repudiation • Key idea of modern cryptography [Diffie-Hellman]: can make authentication (signatures) transferable to third party - Non-repudiation. – Essential to contract signing, e-commerce… • Digital Signatures: last 25 years major effort in – Research • Notions of security • Computationally efficient constructions – Technology, Infrastructure (PKI), Commerce, Legal

Is non-repudiation always desirable? Not necessarily so: • Privacy of conversation, no (verifiable) record. – Do you want everything you ever said to be held against you? • If Bob pays for the authentication, shouldn't be able to transfer it for free • Perhaps can gain efficiency

Is non-repudiation always desirable? Not necessarily so: • Privacy of conversation, no (verifiable) record. – Do you want everything you ever said to be held against you? • If Bob pays for the authentication, shouldn't be able to transfer it for free • Perhaps can gain efficiency

Deniable Authentication Setting: • Sender has a public key known to receiver • Want to come up with an (perhaps interactive) authentication scheme such that the receiver keeps no receipt of conversation. This means: • Any receiver could have generated the conversation itself. – There is a simulator that for any message m and verifier V* generates an indistinguishableconversation. – Similar to Zero-Knowledge! – An example where zero-knowledge is the ends, not the means! Proof of security consists of Unforgeability and Deniability

Deniable Authentication Setting: • Sender has a public key known to receiver • Want to come up with an (perhaps interactive) authentication scheme such that the receiver keeps no receipt of conversation. This means: • Any receiver could have generated the conversation itself. – There is a simulator that for any message m and verifier V* generates an indistinguishableconversation. – Similar to Zero-Knowledge! – An example where zero-knowledge is the ends, not the means! Proof of security consists of Unforgeability and Deniability

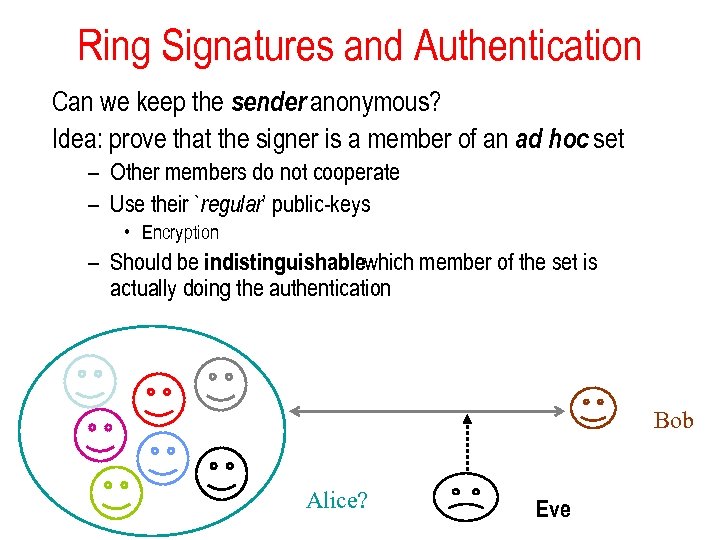

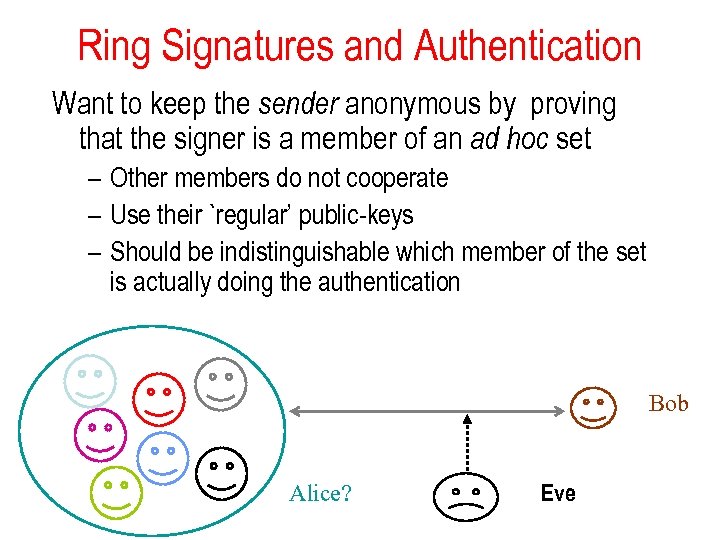

Ring Signatures and Authentication Can we keep the sender anonymous? Idea: prove that the signer is a member of an ad hoc set – Other members do not cooperate – Use their `regular’ public-keys • Encryption – Should be indistinguishablewhich member of the set is actually doing the authentication Bob Alice? Eve

Ring Signatures and Authentication Can we keep the sender anonymous? Idea: prove that the signer is a member of an ad hoc set – Other members do not cooperate – Use their `regular’ public-keys • Encryption – Should be indistinguishablewhich member of the set is actually doing the authentication Bob Alice? Eve

Deniable Ring Authentication Completeness: a good sender and receiver complete the authentication on any message m Unforgeability. Existential unforgeable against adaptive chosen message attack for any sequence of messages m 1, m 2, … mk Adversarially chosen in an adaptive manner Even if sender authenticates all of m 1, m 2, … mk Probability forger convinces receiver to accept a m { m 1, m 2, … mk } is negligible Properties of an interactive authentication scheme

Deniable Ring Authentication Completeness: a good sender and receiver complete the authentication on any message m Unforgeability. Existential unforgeable against adaptive chosen message attack for any sequence of messages m 1, m 2, … mk Adversarially chosen in an adaptive manner Even if sender authenticates all of m 1, m 2, … mk Probability forger convinces receiver to accept a m { m 1, m 2, … mk } is negligible Properties of an interactive authentication scheme

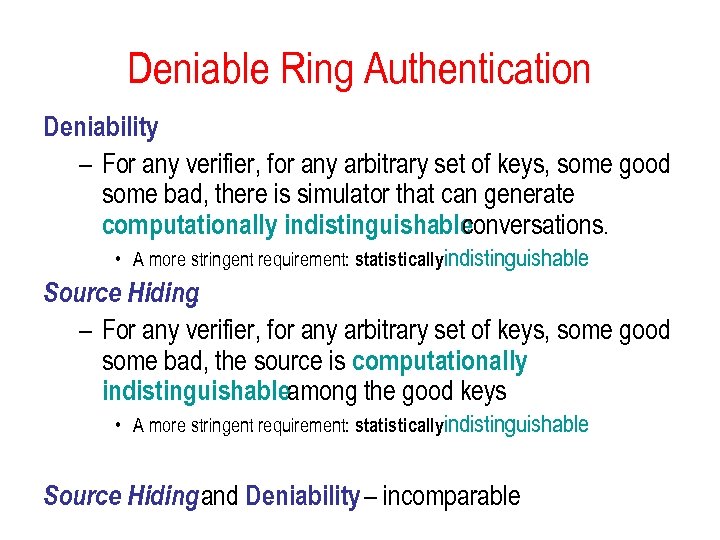

Deniable Ring Authentication Deniability – For any verifier, for any arbitrary set of keys, some good some bad, there is simulator that can generate computationally indistinguishable conversations. • A more stringent requirement: statisticallyindistinguishable Source Hiding: – For any verifier, for any arbitrary set of keys, some good some bad, the source is computationally indistinguishableamong the good keys • A more stringent requirement: statisticallyindistinguishable Source Hiding and Deniability – incomparable

Deniable Ring Authentication Deniability – For any verifier, for any arbitrary set of keys, some good some bad, there is simulator that can generate computationally indistinguishable conversations. • A more stringent requirement: statisticallyindistinguishable Source Hiding: – For any verifier, for any arbitrary set of keys, some good some bad, the source is computationally indistinguishableamong the good keys • A more stringent requirement: statisticallyindistinguishable Source Hiding and Deniability – incomparable

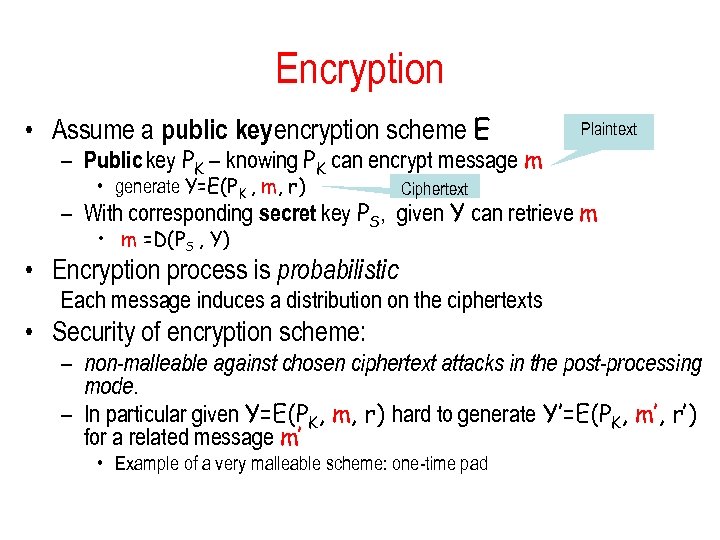

Encryption • Assume a public key encryption scheme E Plaintext – Public key PK – knowing PK can encrypt message m • generate Y=E(PK , m, r) Ciphertext – With corresponding secret key PS, given Y can retrieve m • m =D(PS , Y) • Encryption process is probabilistic Each message induces a distribution on the ciphertexts • Security of encryption scheme: – non-malleable against chosen ciphertext attacks in the post-processing mode. – In particular given Y=E(PK, m, r) hard to generate Y’=E(PK, m’, r’) for a related message m’ • Example of a very malleable scheme: one-time pad

Encryption • Assume a public key encryption scheme E Plaintext – Public key PK – knowing PK can encrypt message m • generate Y=E(PK , m, r) Ciphertext – With corresponding secret key PS, given Y can retrieve m • m =D(PS , Y) • Encryption process is probabilistic Each message induces a distribution on the ciphertexts • Security of encryption scheme: – non-malleable against chosen ciphertext attacks in the post-processing mode. – In particular given Y=E(PK, m, r) hard to generate Y’=E(PK, m’, r’) for a related message m’ • Example of a very malleable scheme: one-time pad

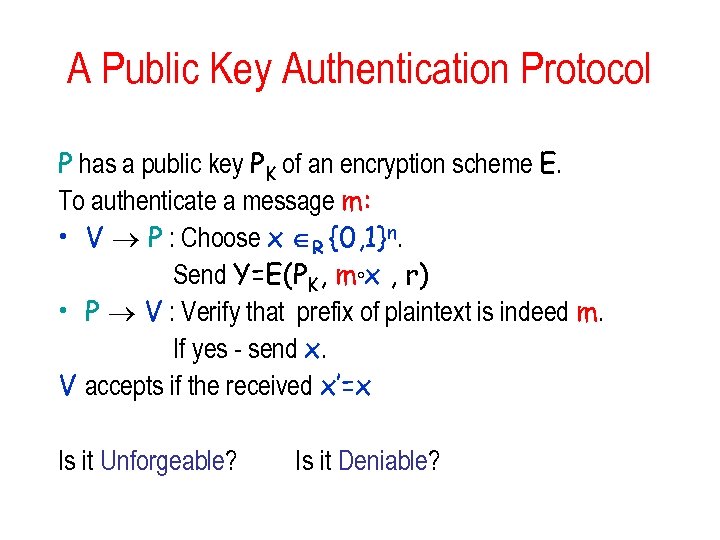

A Public Key Authentication Protocol P has a public key PK of an encryption scheme E. To authenticate a message m: • V P : Choose x R {0, 1}n. Send Y=E(PK, m°x , r) • P V : Verify that prefix of plaintext is indeed m. If yes - send x. V accepts if the received x’=x Is it Unforgeable? Is it Deniable?

A Public Key Authentication Protocol P has a public key PK of an encryption scheme E. To authenticate a message m: • V P : Choose x R {0, 1}n. Send Y=E(PK, m°x , r) • P V : Verify that prefix of plaintext is indeed m. If yes - send x. V accepts if the received x’=x Is it Unforgeable? Is it Deniable?

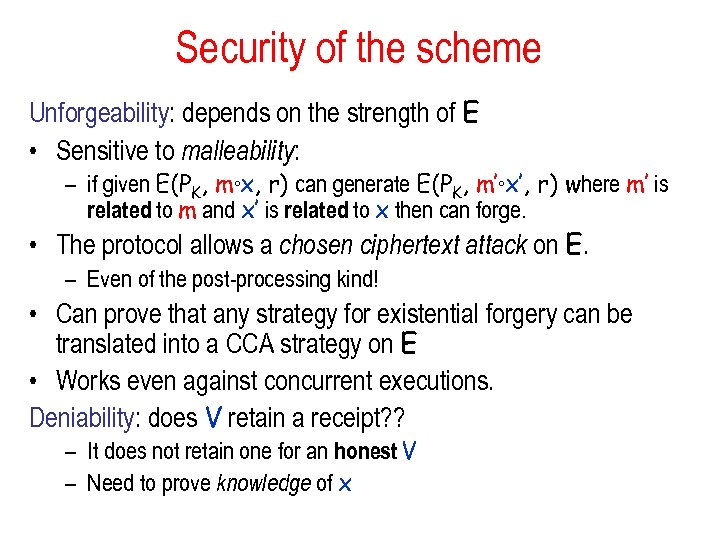

Security of the scheme Unforgeability: depends on the strength of E • Sensitive to malleability: – if given E(PK, m°x, r) can generate E(PK, m’°x’, r) where m’ is related to m and x’ is related to x then can forge. • The protocol allows a chosen ciphertext attack on E. – Even of the post-processing kind! • Can prove that any strategy for existential forgery can be translated into a CCA strategy on E • Works even against concurrent executions. Deniability: does V retain a receipt? ? – It does not retain one for an honest V – Need to prove knowledge of x

Security of the scheme Unforgeability: depends on the strength of E • Sensitive to malleability: – if given E(PK, m°x, r) can generate E(PK, m’°x’, r) where m’ is related to m and x’ is related to x then can forge. • The protocol allows a chosen ciphertext attack on E. – Even of the post-processing kind! • Can prove that any strategy for existential forgery can be translated into a CCA strategy on E • Works even against concurrent executions. Deniability: does V retain a receipt? ? – It does not retain one for an honest V – Need to prove knowledge of x

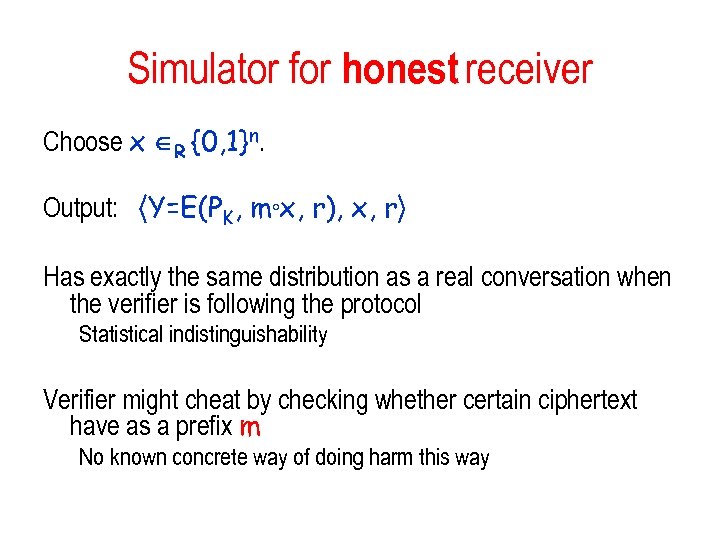

Simulator for honest receiver Choose x R {0, 1}n. Output: h. Y=E(PK, m°x, r), x, ri Has exactly the same distribution as a real conversation when the verifier is following the protocol Statistical indistinguishability Verifier might cheat by checking whether certain ciphertext have as a prefix m No known concrete way of doing harm this way

Simulator for honest receiver Choose x R {0, 1}n. Output: h. Y=E(PK, m°x, r), x, ri Has exactly the same distribution as a real conversation when the verifier is following the protocol Statistical indistinguishability Verifier might cheat by checking whether certain ciphertext have as a prefix m No known concrete way of doing harm this way

![Encryption: Implementation • Under any trapdoor permutation - rather inefficient [DDN]. • Cramer & Encryption: Implementation • Under any trapdoor permutation - rather inefficient [DDN]. • Cramer &](https://present5.com/presentation/c5c82a7bf041dfb68cacdb55efc0ad8f/image-16.jpg) Encryption: Implementation • Under any trapdoor permutation - rather inefficient [DDN]. • Cramer & Shoup: Under the Decisional DH assumption – Requires a few exponentiations. • With Random Oracles: several proposals – RSA with OAEP - same complexity as vanilla RSA [Crypto’ 2001] – Can use low exponent RSA/Rabin • With additional Interaction: J. Katz’s non malleable POKS?

Encryption: Implementation • Under any trapdoor permutation - rather inefficient [DDN]. • Cramer & Shoup: Under the Decisional DH assumption – Requires a few exponentiations. • With Random Oracles: several proposals – RSA with OAEP - same complexity as vanilla RSA [Crypto’ 2001] – Can use low exponent RSA/Rabin • With additional Interaction: J. Katz’s non malleable POKS?

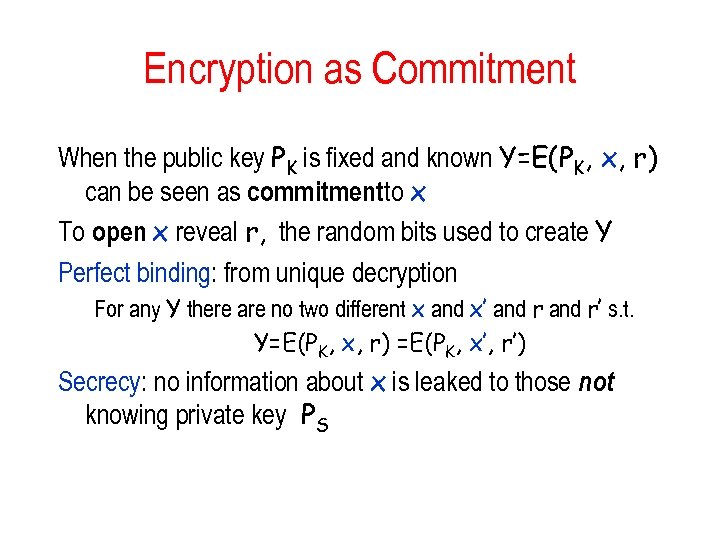

Encryption as Commitment When the public key PK is fixed and known Y=E(PK, x, r) can be seen as commitmentto x To open x reveal r, the random bits used to create Y Perfect binding: from unique decryption For any Y there are no two different x and x’ and r’ s. t. Y=E(PK, x, r) =E(PK, x’, r’) Secrecy: no information about x is leaked to those not knowing private key PS

Encryption as Commitment When the public key PK is fixed and known Y=E(PK, x, r) can be seen as commitmentto x To open x reveal r, the random bits used to create Y Perfect binding: from unique decryption For any Y there are no two different x and x’ and r’ s. t. Y=E(PK, x, r) =E(PK, x’, r’) Secrecy: no information about x is leaked to those not knowing private key PS

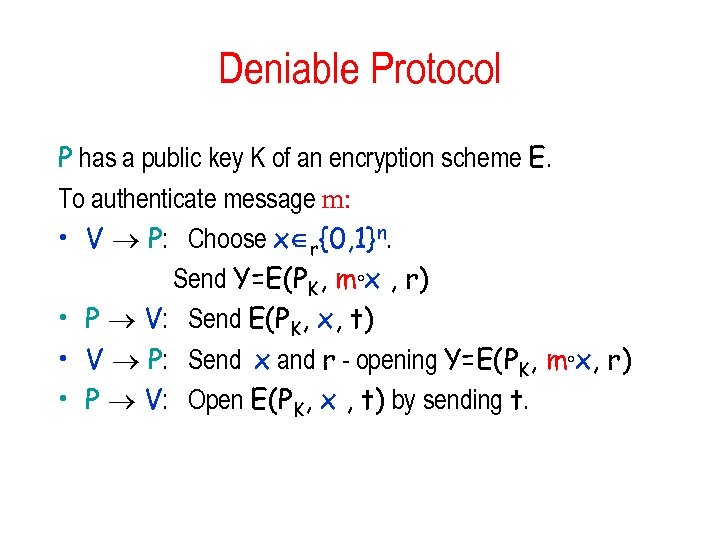

Deniable Protocol P has a public key K of an encryption scheme E. To authenticate message m: • V P: Choose x r{0, 1}n. Send Y=E(PK, m°x , r) • P V: Send E(PK, x, t) • V P: Send x and r - opening Y=E(PK, m°x, r) • P V: Open E(PK, x , t) by sending t.

Deniable Protocol P has a public key K of an encryption scheme E. To authenticate message m: • V P: Choose x r{0, 1}n. Send Y=E(PK, m°x , r) • P V: Send E(PK, x, t) • V P: Send x and r - opening Y=E(PK, m°x, r) • P V: Open E(PK, x , t) by sending t.

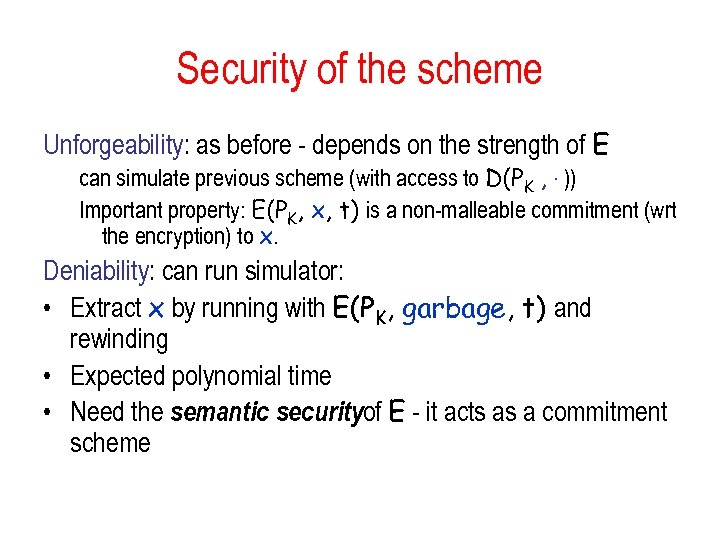

Security of the scheme Unforgeability: as before - depends on the strength of E can simulate previous scheme (with access to D(PK , . )) Important property: E(PK, x, t) is a non-malleable commitment (wrt the encryption) to x. Deniability: can run simulator: • Extract x by running with E(PK, garbage, t) and rewinding • Expected polynomial time • Need the semantic securityof E - it acts as a commitment scheme

Security of the scheme Unforgeability: as before - depends on the strength of E can simulate previous scheme (with access to D(PK , . )) Important property: E(PK, x, t) is a non-malleable commitment (wrt the encryption) to x. Deniability: can run simulator: • Extract x by running with E(PK, garbage, t) and rewinding • Expected polynomial time • Need the semantic securityof E - it acts as a commitment scheme

Ring Signatures and Authentication Want to keep the sender anonymous by proving that the signer is a member of an ad hoc set – Other members do not cooperate – Use their `regular’ public-keys – Should be indistinguishable which member of the set is actually doing the authentication Bob Alice? Eve

Ring Signatures and Authentication Want to keep the sender anonymous by proving that the signer is a member of an ad hoc set – Other members do not cooperate – Use their `regular’ public-keys – Should be indistinguishable which member of the set is actually doing the authentication Bob Alice? Eve

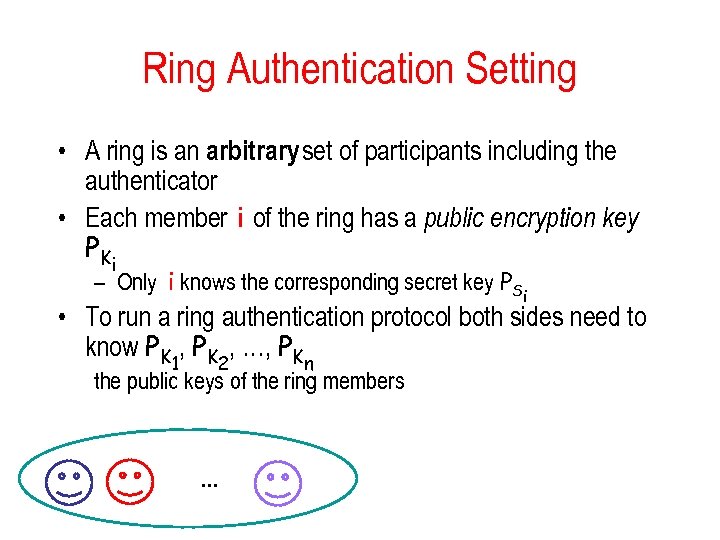

Ring Authentication Setting • A ring is an arbitrary set of participants including the authenticator • Each member i of the ring has a public encryption key PKi – Only i knows the corresponding secret key PSi • To run a ring authentication protocol both sides need to know PK 1, PK 2, …, PKn the public keys of the ring members . . .

Ring Authentication Setting • A ring is an arbitrary set of participants including the authenticator • Each member i of the ring has a public encryption key PKi – Only i knows the corresponding secret key PSi • To run a ring authentication protocol both sides need to know PK 1, PK 2, …, PKn the public keys of the ring members . . .

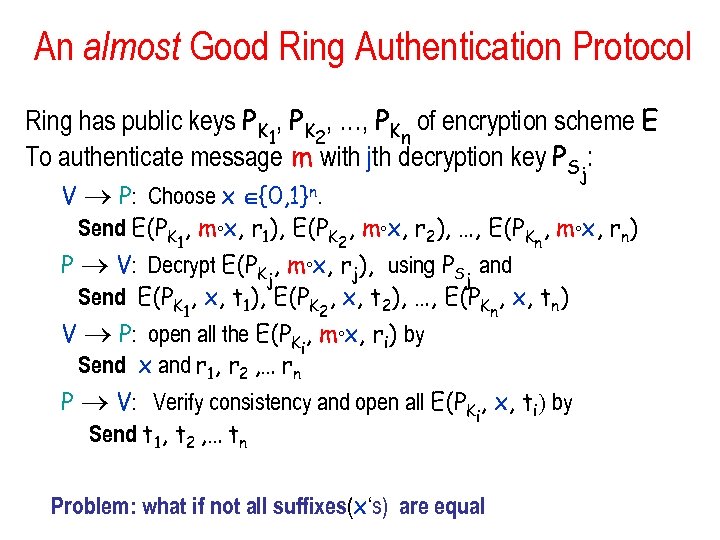

An almost Good Ring Authentication Protocol Ring has public keys PK 1, PK 2, …, PKn of encryption scheme E To authenticate message m with jth decryption key PSj: V P: Choose x {0, 1}n. Send E(PK 1, m°x, r 1), E(PK 2, m°x, r 2), …, E(PKn, m°x, rn) P V: Decrypt E(PKj, m°x, rj), using PSj and Send E(PK 1, x, t 1), E(PK 2, x, t 2), …, E(PKn, x, tn) V P: open all the E(PKi, m°x, ri) by Send x and r 1, r 2 , … rn P V: Verify consistency and open all E(PKi, x, ti) by Send t 1, t 2 , … tn Problem: what if not all suffixes(x‘s) are equal

An almost Good Ring Authentication Protocol Ring has public keys PK 1, PK 2, …, PKn of encryption scheme E To authenticate message m with jth decryption key PSj: V P: Choose x {0, 1}n. Send E(PK 1, m°x, r 1), E(PK 2, m°x, r 2), …, E(PKn, m°x, rn) P V: Decrypt E(PKj, m°x, rj), using PSj and Send E(PK 1, x, t 1), E(PK 2, x, t 2), …, E(PKn, x, tn) V P: open all the E(PKi, m°x, ri) by Send x and r 1, r 2 , … rn P V: Verify consistency and open all E(PKi, x, ti) by Send t 1, t 2 , … tn Problem: what if not all suffixes(x‘s) are equal

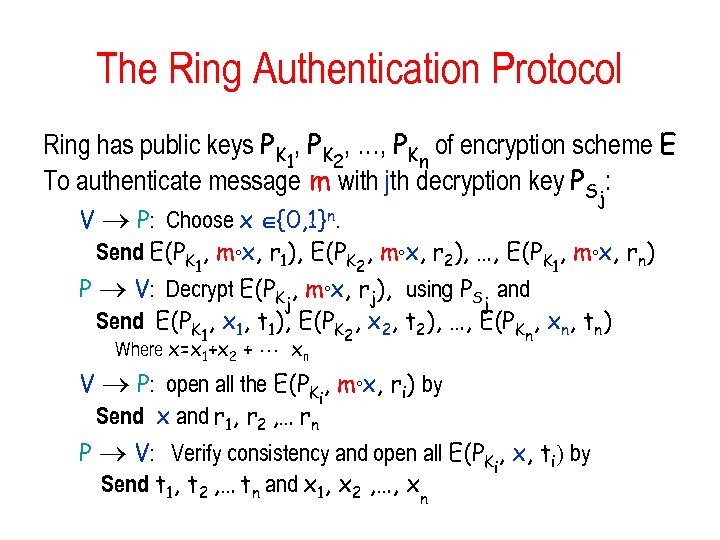

The Ring Authentication Protocol Ring has public keys PK 1, PK 2, …, PKn of encryption scheme E To authenticate message m with jth decryption key PSj: V P: Choose x {0, 1}n. Send E(PK 1, m°x, r 1), E(PK 2, m°x, r 2), …, E(PK 1, m°x, rn) P V: Decrypt E(PKj, m°x, rj), using PSj and Send E(PK 1, x 1, t 1), E(PK 2, x 2, t 2), …, E(PKn, xn, tn) Where x=x 1+x 2 + xn V P: open all the E(PKi, m°x, ri) by Send x and r 1, r 2 , … rn P V: Verify consistency and open all E(PKi, x, ti) by Send t 1, t 2 , … tn and x 1, x 2 , …, xn

The Ring Authentication Protocol Ring has public keys PK 1, PK 2, …, PKn of encryption scheme E To authenticate message m with jth decryption key PSj: V P: Choose x {0, 1}n. Send E(PK 1, m°x, r 1), E(PK 2, m°x, r 2), …, E(PK 1, m°x, rn) P V: Decrypt E(PKj, m°x, rj), using PSj and Send E(PK 1, x 1, t 1), E(PK 2, x 2, t 2), …, E(PKn, xn, tn) Where x=x 1+x 2 + xn V P: open all the E(PKi, m°x, ri) by Send x and r 1, r 2 , … rn P V: Verify consistency and open all E(PKi, x, ti) by Send t 1, t 2 , … tn and x 1, x 2 , …, xn

Complexity of the scheme Sender: single decryption, n encryptions and n encryption verifications Receiver: n encryptions and n encryption verifications Communication Complexity: O(n) public-key encryptions

Complexity of the scheme Sender: single decryption, n encryptions and n encryption verifications Receiver: n encryptions and n encryption verifications Communication Complexity: O(n) public-key encryptions

Security of the scheme Unforgeability: as before (assuming all keys are well chosen) since E(PK 1, x 1, t 1), E(PK 2, x 2, t 2), …, E(PK 1, xn, tn) where x=x 1+x 2 + xn is a non-malleable commitment to x Source Hiding: which key was used (among well chosen keys) is – Computationally indistinguishable during protocol – Statistically indistinguishable after protocol • If ends successfully Deniability: Can run simulator `as before’

Security of the scheme Unforgeability: as before (assuming all keys are well chosen) since E(PK 1, x 1, t 1), E(PK 2, x 2, t 2), …, E(PK 1, xn, tn) where x=x 1+x 2 + xn is a non-malleable commitment to x Source Hiding: which key was used (among well chosen keys) is – Computationally indistinguishable during protocol – Statistically indistinguishable after protocol • If ends successfully Deniability: Can run simulator `as before’

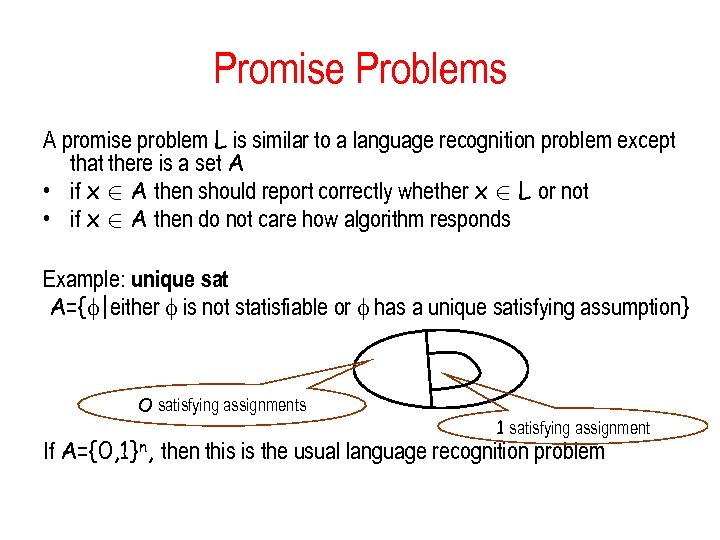

Promise Problems A promise problem L is similar to a language recognition problem except that there is a set A • if x 2 A then should report correctly whether x 2 L or not • if x 2 A then do not care how algorithm responds Example: unique sat A={ |either is not statisfiable or has a unique satisfying assumption} O satisfying assignments 1 satisfying assignment If A={0, 1}n, then this is the usual language recognition problem

Promise Problems A promise problem L is similar to a language recognition problem except that there is a set A • if x 2 A then should report correctly whether x 2 L or not • if x 2 A then do not care how algorithm responds Example: unique sat A={ |either is not statisfiable or has a unique satisfying assumption} O satisfying assignments 1 satisfying assignment If A={0, 1}n, then this is the usual language recognition problem

Statistical Zero-Knowledge So if statistical zero-knowledge is so good, why not use it all the time? Definition: L is a promise problem SZK={L|L has a statistical zero-knowledge protocol} HVSZK={L|L has an honest verifier statistical zeroknowledge protocol} Clearly: SZK µ HVSZK since any protocol good against all verifiers is good against honest ones as well

Statistical Zero-Knowledge So if statistical zero-knowledge is so good, why not use it all the time? Definition: L is a promise problem SZK={L|L has a statistical zero-knowledge protocol} HVSZK={L|L has an honest verifier statistical zeroknowledge protocol} Clearly: SZK µ HVSZK since any protocol good against all verifiers is good against honest ones as well

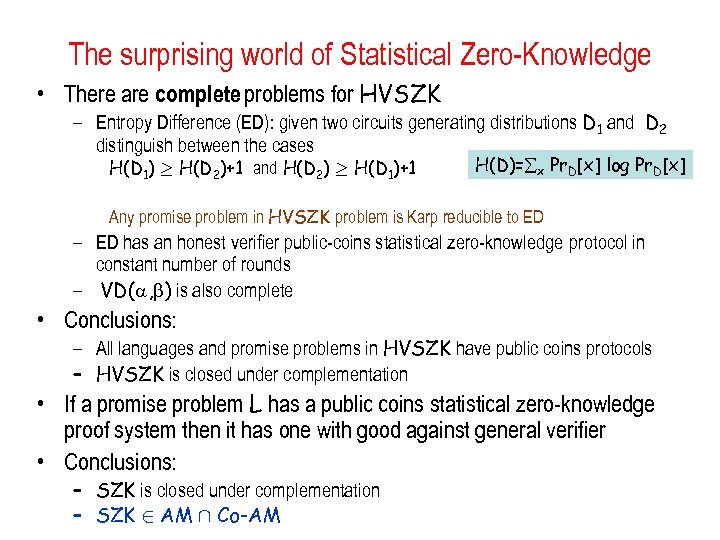

The surprising world of Statistical Zero-Knowledge • There are complete problems for HVSZK – Entropy Difference (ED): given two circuits generating distributions D 1 and D 2 distinguish between the cases H(D 1) ¸ H(D 2)+1 and H(D 2) ¸ H(D 1)+1 H(D)= x Pr. D[x] log Pr. D[x] Any promise problem in HVSZK problem is Karp reducible to ED – ED has an honest verifier public-coins statistical zero-knowledge protocol in constant number of rounds – VD( , ) is also complete • Conclusions: – All languages and promise problems in HVSZK have public coins protocols – HVSZK is closed under complementation • If a promise problem L has a public coins statistical zero-knowledge proof system then it has one with good against general verifier • Conclusions: – SZK is closed under complementation – SZK 2 AM Å Co-AM

The surprising world of Statistical Zero-Knowledge • There are complete problems for HVSZK – Entropy Difference (ED): given two circuits generating distributions D 1 and D 2 distinguish between the cases H(D 1) ¸ H(D 2)+1 and H(D 2) ¸ H(D 1)+1 H(D)= x Pr. D[x] log Pr. D[x] Any promise problem in HVSZK problem is Karp reducible to ED – ED has an honest verifier public-coins statistical zero-knowledge protocol in constant number of rounds – VD( , ) is also complete • Conclusions: – All languages and promise problems in HVSZK have public coins protocols – HVSZK is closed under complementation • If a promise problem L has a public coins statistical zero-knowledge proof system then it has one with good against general verifier • Conclusions: – SZK is closed under complementation – SZK 2 AM Å Co-AM

Homework • Show an AM protocol for Entropy Difference when the two distribution are promised also to be flat – For x and x’ such that Pr[x] ≠ 0 and Pr[x’] ≠ 0 we have Pr[x] = Pr[x’] Is the protocol SZK or HVSZK?

Homework • Show an AM protocol for Entropy Difference when the two distribution are promised also to be flat – For x and x’ such that Pr[x] ≠ 0 and Pr[x’] ≠ 0 we have Pr[x] = Pr[x’] Is the protocol SZK or HVSZK?

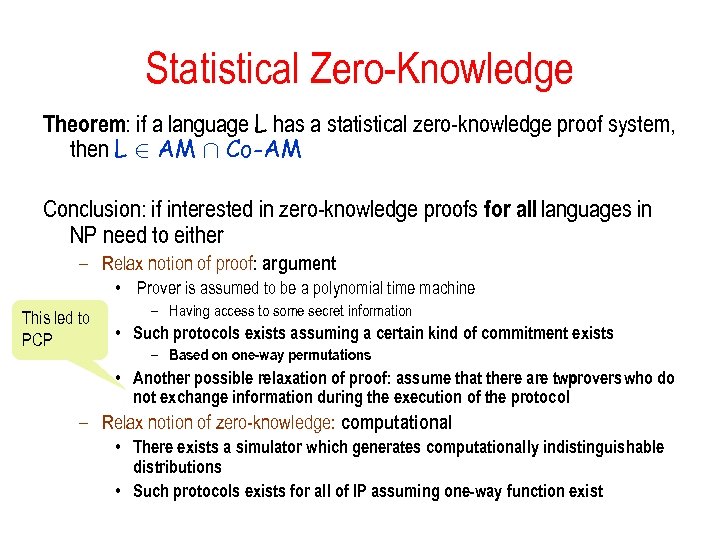

Statistical Zero-Knowledge Theorem: if a language L has a statistical zero-knowledge proof system, then L 2 AM Å Co-AM Conclusion: if interested in zero-knowledge proofs for all languages in NP need to either – Relax notion of proof: argument • Prover is assumed to be a polynomial time machine This led to PCP – Having access to some secret information • Such protocols exists assuming a certain kind of commitment exists – Based on one-way permutations • Another possible relaxation of proof: assume that there are two provers who do not exchange information during the execution of the protocol – Relax notion of zero-knowledge: computational • There exists a simulator which generates computationally indistinguishable distributions • Such protocols exists for all of IP assuming one-way function exist

Statistical Zero-Knowledge Theorem: if a language L has a statistical zero-knowledge proof system, then L 2 AM Å Co-AM Conclusion: if interested in zero-knowledge proofs for all languages in NP need to either – Relax notion of proof: argument • Prover is assumed to be a polynomial time machine This led to PCP – Having access to some secret information • Such protocols exists assuming a certain kind of commitment exists – Based on one-way permutations • Another possible relaxation of proof: assume that there are two provers who do not exchange information during the execution of the protocol – Relax notion of zero-knowledge: computational • There exists a simulator which generates computationally indistinguishable distributions • Such protocols exists for all of IP assuming one-way function exist

Sources for Statistical Zero-Knowledge • Salil Vadhan Thesis: www. eecs. harvard. edu/~salil/papers/phdthesis-abs. html • Results are due to Goldreich, Sahai and Vadhan • Building on – Fortnow and Aiello and Hastad: SZK µ AM Å Co-AM – Okamoto: SZK is closed under complementation

Sources for Statistical Zero-Knowledge • Salil Vadhan Thesis: www. eecs. harvard. edu/~salil/papers/phdthesis-abs. html • Results are due to Goldreich, Sahai and Vadhan • Building on – Fortnow and Aiello and Hastad: SZK µ AM Å Co-AM – Okamoto: SZK is closed under complementation

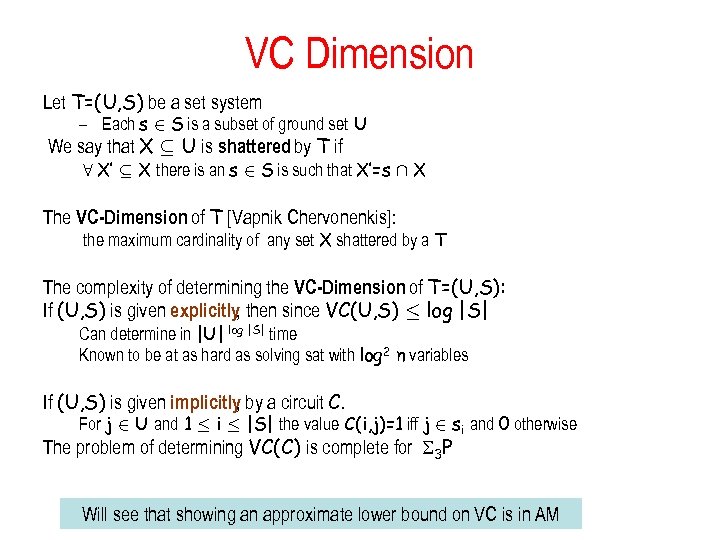

VC Dimension Let T=(U, S) be a set system – Each s 2 S is a subset of ground set U We say that X µ U is shattered by T if 8 X’ µ X there is an s 2 S is such that X’=s Å X The VC-Dimension of T [Vapnik Chervonenkis]: the maximum cardinality of any set X shattered by a T The complexity of determining the VC-Dimension of T=(U, S): If (U, S) is given explicitly then since VC(U, S) · log |S| , Can determine in |U| log |S| time Known to be at as hard as solving sat with log 2 n variables If (U, S) is given implicitly by a circuit C. , For j 2 U and 1 · i · |S| the value C(i, j)=1 iff j 2 si and 0 otherwise The problem of determining VC(C) is complete for 3 P Will see that showing an approximate lower bound on VC is in AM

VC Dimension Let T=(U, S) be a set system – Each s 2 S is a subset of ground set U We say that X µ U is shattered by T if 8 X’ µ X there is an s 2 S is such that X’=s Å X The VC-Dimension of T [Vapnik Chervonenkis]: the maximum cardinality of any set X shattered by a T The complexity of determining the VC-Dimension of T=(U, S): If (U, S) is given explicitly then since VC(U, S) · log |S| , Can determine in |U| log |S| time Known to be at as hard as solving sat with log 2 n variables If (U, S) is given implicitly by a circuit C. , For j 2 U and 1 · i · |S| the value C(i, j)=1 iff j 2 si and 0 otherwise The problem of determining VC(C) is complete for 3 P Will see that showing an approximate lower bound on VC is in AM

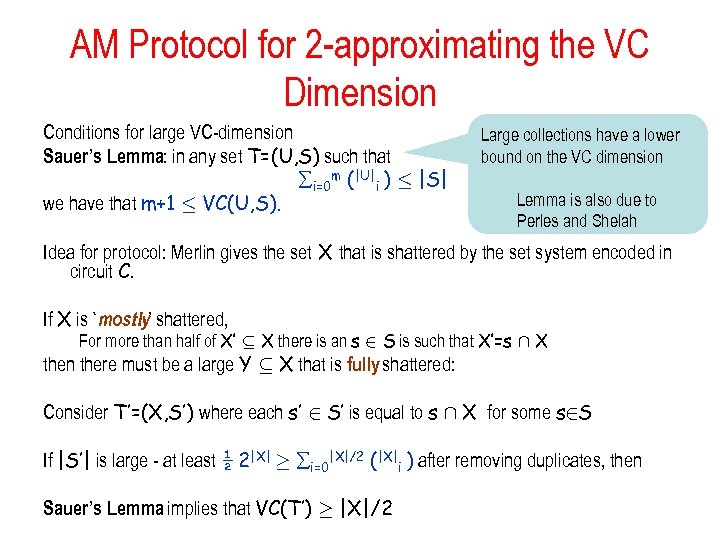

AM Protocol for 2 -approximating the VC Dimension Conditions for large VC-dimension Sauer’s Lemma: in any set T=(U, S) such that i=0 m (|U|i ) · |S| we have that m+1 · VC(U, S). Large collections have a lower bound on the VC dimension Lemma is also due to Perles and Shelah Idea for protocol: Merlin gives the set X that is shattered by the set system encoded in circuit C. If X is `mostly’ shattered, For more than half of X’ µ X there is an s 2 S is such that X’=s Å X then there must be a large Y µ X that is fully shattered: Consider T’=(X, S’) where each s’ 2 S’ is equal to s Å X for some s 2 S If |S’| is large - at least ½ 2|X| ¸ i=0|X|/2 (|X|i ) after removing duplicates, then Sauer’s Lemma implies that VC(T’) ¸ |X|/2

AM Protocol for 2 -approximating the VC Dimension Conditions for large VC-dimension Sauer’s Lemma: in any set T=(U, S) such that i=0 m (|U|i ) · |S| we have that m+1 · VC(U, S). Large collections have a lower bound on the VC dimension Lemma is also due to Perles and Shelah Idea for protocol: Merlin gives the set X that is shattered by the set system encoded in circuit C. If X is `mostly’ shattered, For more than half of X’ µ X there is an s 2 S is such that X’=s Å X then there must be a large Y µ X that is fully shattered: Consider T’=(X, S’) where each s’ 2 S’ is equal to s Å X for some s 2 S If |S’| is large - at least ½ 2|X| ¸ i=0|X|/2 (|X|i ) after removing duplicates, then Sauer’s Lemma implies that VC(T’) ¸ |X|/2

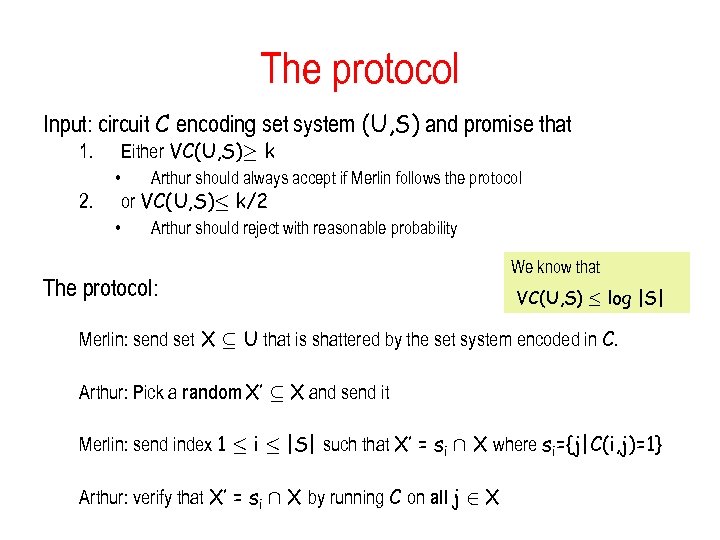

The protocol Input: circuit C encoding set system (U, S) and promise that Either VC(U, S)¸ k 1. • 2. • Arthur should always accept if Merlin follows the protocol or VC(U, S)· k/2 Arthur should reject with reasonable probability The protocol: We know that VC(U, S) · log |S| Merlin: send set X µ U that is shattered by the set system encoded in C. Arthur: Pick a random X’ µ X and send it Merlin: send index 1 · i · |S| such that X’ = si Å X where si={j|C(i, j)=1} Arthur: verify that X’ = si Å X by running C on all j 2 X

The protocol Input: circuit C encoding set system (U, S) and promise that Either VC(U, S)¸ k 1. • 2. • Arthur should always accept if Merlin follows the protocol or VC(U, S)· k/2 Arthur should reject with reasonable probability The protocol: We know that VC(U, S) · log |S| Merlin: send set X µ U that is shattered by the set system encoded in C. Arthur: Pick a random X’ µ X and send it Merlin: send index 1 · i · |S| such that X’ = si Å X where si={j|C(i, j)=1} Arthur: verify that X’ = si Å X by running C on all j 2 X

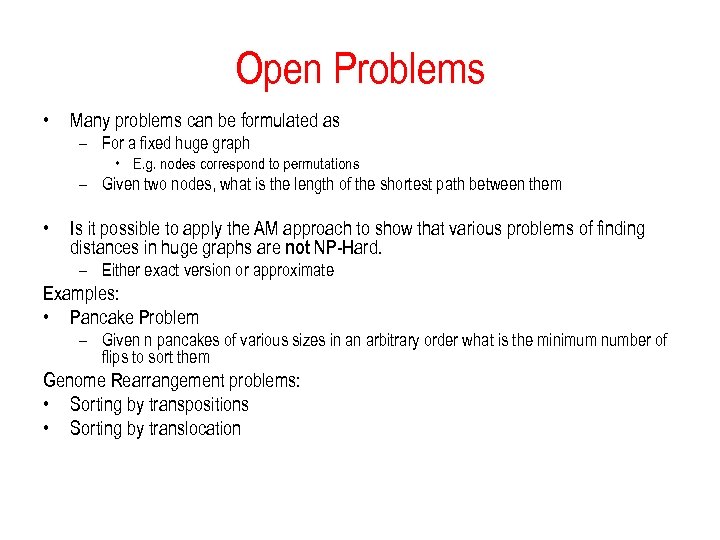

Open Problems • Many problems can be formulated as – For a fixed huge graph • E. g. nodes correspond to permutations – Given two nodes, what is the length of the shortest path between them • Is it possible to apply the AM approach to show that various problems of finding distances in huge graphs are not NP-Hard. – Either exact version or approximate Examples: • Pancake Problem – Given n pancakes of various sizes in an arbitrary order what is the minimum number of flips to sort them Genome Rearrangement problems: • Sorting by transpositions • Sorting by translocation

Open Problems • Many problems can be formulated as – For a fixed huge graph • E. g. nodes correspond to permutations – Given two nodes, what is the length of the shortest path between them • Is it possible to apply the AM approach to show that various problems of finding distances in huge graphs are not NP-Hard. – Either exact version or approximate Examples: • Pancake Problem – Given n pancakes of various sizes in an arbitrary order what is the minimum number of flips to sort them Genome Rearrangement problems: • Sorting by transpositions • Sorting by translocation

Idea for protocol Verifier • Pick at random one of the two nodes as a starting point • Make a random work of certain length and give prover end point Prover: • Determine the which node is the starting point

Idea for protocol Verifier • Pick at random one of the two nodes as a starting point • Make a random work of certain length and give prover end point Prover: • Determine the which node is the starting point

References • See Tzvika Hartman’s Ph. D thesis (Weizmann Institute) The diameter of the Pancake Graph Program – Bill Gates and Christos Papadimitriou: Bounds For Sorting By Prefix Reversal. Discrete Mathematics, vol 27, pp. 47 -57, 1979. – H. Heydari and H. I. Sudborough: On the Diameter of the Pancake Network. Journal of Algorithms, 1997

References • See Tzvika Hartman’s Ph. D thesis (Weizmann Institute) The diameter of the Pancake Graph Program – Bill Gates and Christos Papadimitriou: Bounds For Sorting By Prefix Reversal. Discrete Mathematics, vol 27, pp. 47 -57, 1979. – H. Heydari and H. I. Sudborough: On the Diameter of the Pancake Network. Journal of Algorithms, 1997

What’s next Natural development of Interactive Proofs: • PCP: Probabilistically Checkable Proofs – The prover sends the a polynomial sized proof – The verifier checks only small parts of it A new characterization of NP Can reduce any problem • Main applications: – – Inapproximability of many optimization problems Low communication cryptographic protocols Get back to it towards end of course

What’s next Natural development of Interactive Proofs: • PCP: Probabilistically Checkable Proofs – The prover sends the a polynomial sized proof – The verifier checks only small parts of it A new characterization of NP Can reduce any problem • Main applications: – – Inapproximability of many optimization problems Low communication cryptographic protocols Get back to it towards end of course

Derandomization A major research question: • How to make the construction of – Small Sample space `resembling’ large one – Hitting sets Efficient. Successful approach: randomness from hardness – (Cryptographic) pseudo-random generators – Complexity oriented pseudo-random generators

Derandomization A major research question: • How to make the construction of – Small Sample space `resembling’ large one – Hitting sets Efficient. Successful approach: randomness from hardness – (Cryptographic) pseudo-random generators – Complexity oriented pseudo-random generators

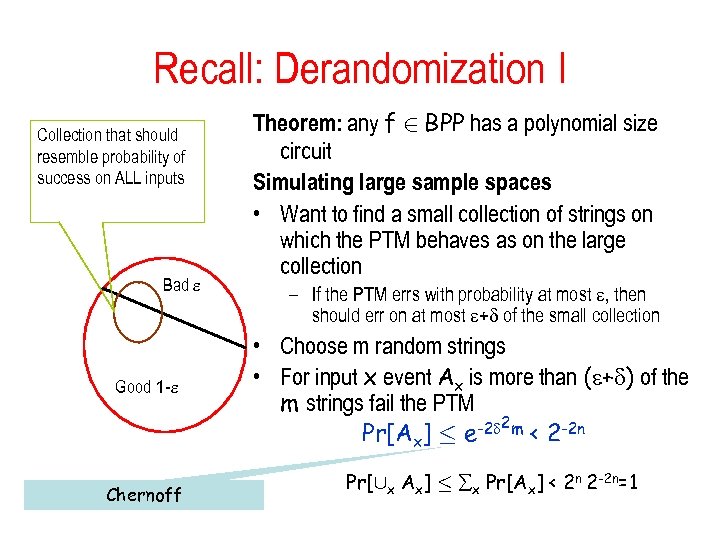

Recall: Derandomization I Collection that should resemble probability of success on ALL inputs Bad Good 1 - Chernoff Theorem: any f 2 BPP has a polynomial size circuit Simulating large sample spaces • Want to find a small collection of strings on which the PTM behaves as on the large collection – If the PTM errs with probability at most , then should err on at most + of the small collection • Choose m random strings • For input x event Ax is more than ( + ) of the m strings fail the PTM -2 2 m < 2 -2 n Pr[Ax] · e Pr[[x Ax] · x Pr[Ax] < 2 n 2 -2 n=1

Recall: Derandomization I Collection that should resemble probability of success on ALL inputs Bad Good 1 - Chernoff Theorem: any f 2 BPP has a polynomial size circuit Simulating large sample spaces • Want to find a small collection of strings on which the PTM behaves as on the large collection – If the PTM errs with probability at most , then should err on at most + of the small collection • Choose m random strings • For input x event Ax is more than ( + ) of the m strings fail the PTM -2 2 m < 2 -2 n Pr[Ax] · e Pr[[x Ax] · x Pr[Ax] < 2 n 2 -2 n=1

Pseudo-random generators • Would like to stretch a short secret (seed) into a long one • The resulting long string should be usable in any case where a long string is needed – In particular: cryptographic application as a one-time pad • Important notion: Indistinguishability Two probability distributions that cannot be distinguished – Statistical indistinguishability: distances between probability distributions – New notion: computational indistinguishability

Pseudo-random generators • Would like to stretch a short secret (seed) into a long one • The resulting long string should be usable in any case where a long string is needed – In particular: cryptographic application as a one-time pad • Important notion: Indistinguishability Two probability distributions that cannot be distinguished – Statistical indistinguishability: distances between probability distributions – New notion: computational indistinguishability

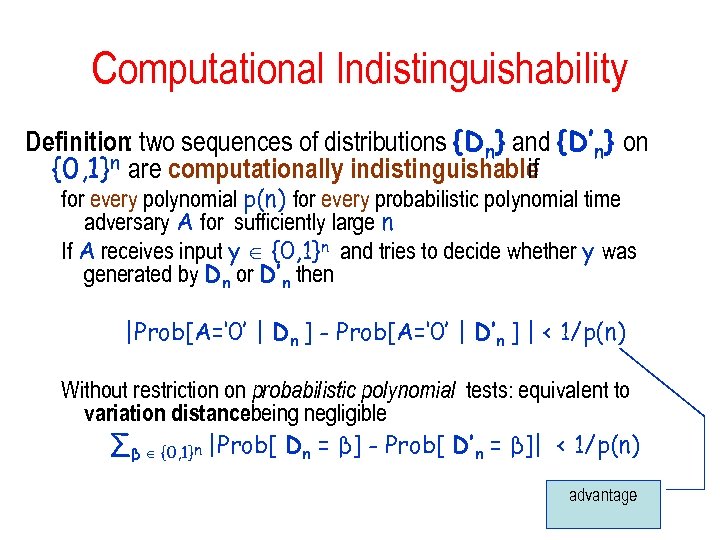

Computational Indistinguishability Definition: two sequences of distributions {Dn} and {D’n} on {0, 1}n are computationally indistinguishable if for every polynomial p(n) for every probabilistic polynomial time adversary A for sufficiently large n If A receives input y {0, 1}n and tries to decide whether y was generated by Dn or D’n then |Prob[A=‘ 0’ | Dn ] - Prob[A=‘ 0’ | D’n ] | < 1/p(n) Without restriction on probabilistic polynomial tests: equivalent to variation distancebeing negligible ∑β {0, 1}n |Prob[ Dn = β] - Prob[ D’n = β]| < 1/p(n) advantage

Computational Indistinguishability Definition: two sequences of distributions {Dn} and {D’n} on {0, 1}n are computationally indistinguishable if for every polynomial p(n) for every probabilistic polynomial time adversary A for sufficiently large n If A receives input y {0, 1}n and tries to decide whether y was generated by Dn or D’n then |Prob[A=‘ 0’ | Dn ] - Prob[A=‘ 0’ | D’n ] | < 1/p(n) Without restriction on probabilistic polynomial tests: equivalent to variation distancebeing negligible ∑β {0, 1}n |Prob[ Dn = β] - Prob[ D’n = β]| < 1/p(n) advantage

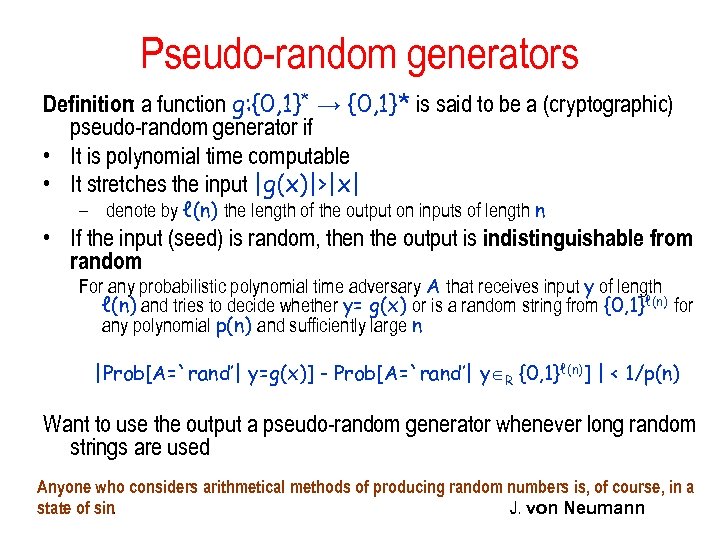

Pseudo-random generators Definition: a function g: {0, 1}* → {0, 1}* is said to be a (cryptographic) pseudo-random generator if • It is polynomial time computable • It stretches the input |g(x)|>|x| – denote by ℓ(n) the length of the output on inputs of length n • If the input (seed) is random, then the output is indistinguishable from random For any probabilistic polynomial time adversary A that receives input y of length ℓ(n) and tries to decide whether y= g(x) or is a random string from {0, 1}ℓ(n) for any polynomial p(n) and sufficiently large n |Prob[A=`rand’| y=g(x)] - Prob[A=`rand’| y R {0, 1}ℓ(n)] | < 1/p(n) Want to use the output a pseudo-random generator whenever long random strings are used Anyone who considers arithmetical methods of producing random numbers is, of course, in a state of sin. J. von Neumann

Pseudo-random generators Definition: a function g: {0, 1}* → {0, 1}* is said to be a (cryptographic) pseudo-random generator if • It is polynomial time computable • It stretches the input |g(x)|>|x| – denote by ℓ(n) the length of the output on inputs of length n • If the input (seed) is random, then the output is indistinguishable from random For any probabilistic polynomial time adversary A that receives input y of length ℓ(n) and tries to decide whether y= g(x) or is a random string from {0, 1}ℓ(n) for any polynomial p(n) and sufficiently large n |Prob[A=`rand’| y=g(x)] - Prob[A=`rand’| y R {0, 1}ℓ(n)] | < 1/p(n) Want to use the output a pseudo-random generator whenever long random strings are used Anyone who considers arithmetical methods of producing random numbers is, of course, in a state of sin. J. von Neumann

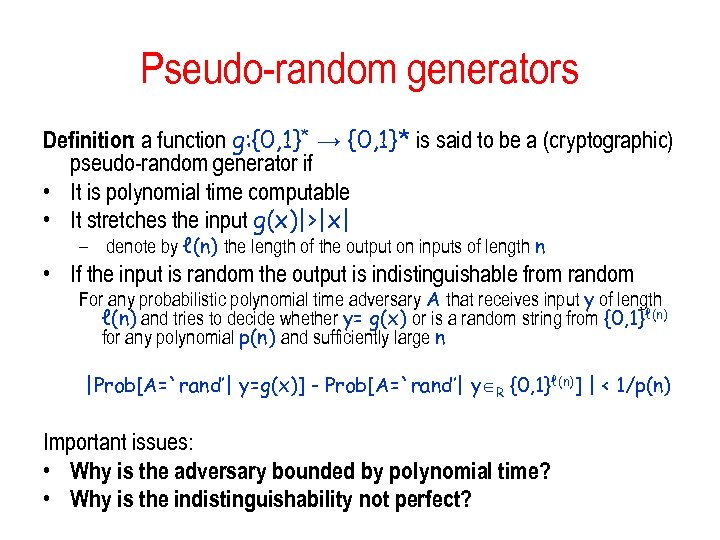

Pseudo-random generators Definition: a function g: {0, 1}* → {0, 1}* is said to be a (cryptographic) pseudo-random generator if • It is polynomial time computable • It stretches the input g(x)|>|x| – denote by ℓ(n) the length of the output on inputs of length n • If the input is random the output is indistinguishable from random For any probabilistic polynomial time adversary A that receives input y of length ℓ(n) and tries to decide whether y= g(x) or is a random string from {0, 1}ℓ(n) for any polynomial p(n) and sufficiently large n |Prob[A=`rand’| y=g(x)] - Prob[A=`rand’| y R {0, 1}ℓ(n)] | < 1/p(n) Important issues: • Why is the adversary bounded by polynomial time? • Why is the indistinguishability not perfect?

Pseudo-random generators Definition: a function g: {0, 1}* → {0, 1}* is said to be a (cryptographic) pseudo-random generator if • It is polynomial time computable • It stretches the input g(x)|>|x| – denote by ℓ(n) the length of the output on inputs of length n • If the input is random the output is indistinguishable from random For any probabilistic polynomial time adversary A that receives input y of length ℓ(n) and tries to decide whether y= g(x) or is a random string from {0, 1}ℓ(n) for any polynomial p(n) and sufficiently large n |Prob[A=`rand’| y=g(x)] - Prob[A=`rand’| y R {0, 1}ℓ(n)] | < 1/p(n) Important issues: • Why is the adversary bounded by polynomial time? • Why is the indistinguishability not perfect?

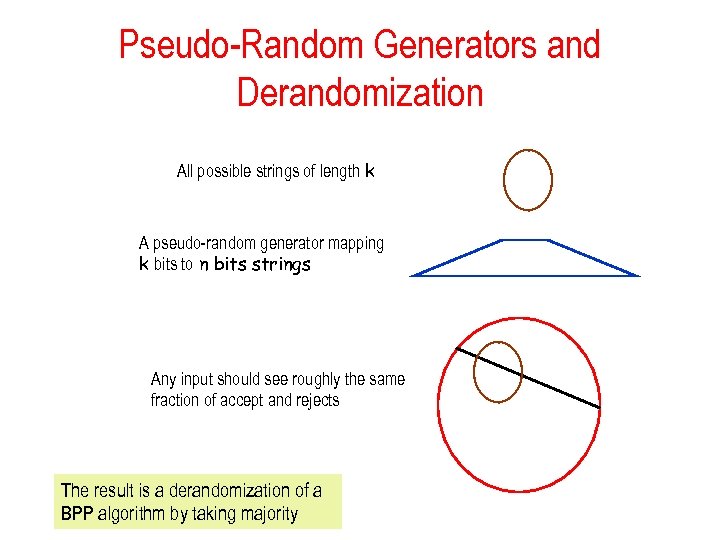

Pseudo-Random Generators and Derandomization All possible strings of length k A pseudo-random generator mapping k bits to n bits strings Any input should see roughly the same fraction of accept and rejects The result is a derandomization of a BPP algorithm by taking majority

Pseudo-Random Generators and Derandomization All possible strings of length k A pseudo-random generator mapping k bits to n bits strings Any input should see roughly the same fraction of accept and rejects The result is a derandomization of a BPP algorithm by taking majority

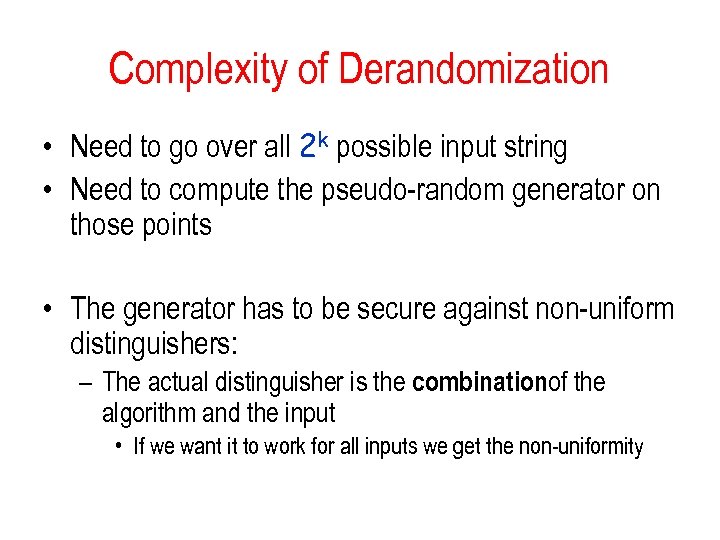

Complexity of Derandomization • Need to go over all 2 k possible input string • Need to compute the pseudo-random generator on those points • The generator has to be secure against non-uniform distinguishers: – The actual distinguisher is the combinationof the algorithm and the input • If we want it to work for all inputs we get the non-uniformity

Complexity of Derandomization • Need to go over all 2 k possible input string • Need to compute the pseudo-random generator on those points • The generator has to be secure against non-uniform distinguishers: – The actual distinguisher is the combinationof the algorithm and the input • If we want it to work for all inputs we get the non-uniformity

Construction of pseudo-random generators randomness from hardness • Idea: for any given a one-way function there must be a hard decision problem hidden there • If balanced enough: looks random • Such a problem is a hardcore predicate • Possibilities: – Last bit – First bit – Inner product

Construction of pseudo-random generators randomness from hardness • Idea: for any given a one-way function there must be a hard decision problem hidden there • If balanced enough: looks random • Such a problem is a hardcore predicate • Possibilities: – Last bit – First bit – Inner product

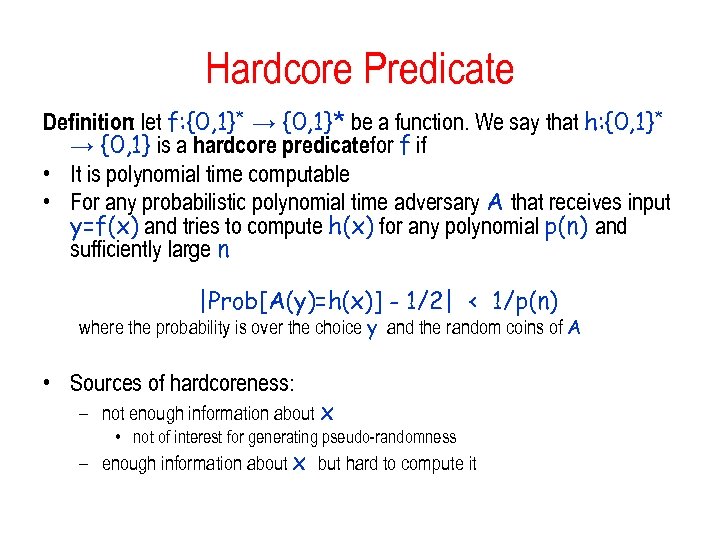

Hardcore Predicate Definition: let f: {0, 1}* → {0, 1}* be a function. We say that h: {0, 1}* → {0, 1} is a hardcore predicate for f if • It is polynomial time computable • For any probabilistic polynomial time adversary A that receives input y=f(x) and tries to compute h(x) for any polynomial p(n) and sufficiently large n |Prob[A(y)=h(x)] - 1/2| < 1/p(n) where the probability is over the choice y and the random coins of A • Sources of hardcoreness: – not enough information about x • not of interest for generating pseudo-randomness – enough information about x but hard to compute it

Hardcore Predicate Definition: let f: {0, 1}* → {0, 1}* be a function. We say that h: {0, 1}* → {0, 1} is a hardcore predicate for f if • It is polynomial time computable • For any probabilistic polynomial time adversary A that receives input y=f(x) and tries to compute h(x) for any polynomial p(n) and sufficiently large n |Prob[A(y)=h(x)] - 1/2| < 1/p(n) where the probability is over the choice y and the random coins of A • Sources of hardcoreness: – not enough information about x • not of interest for generating pseudo-randomness – enough information about x but hard to compute it

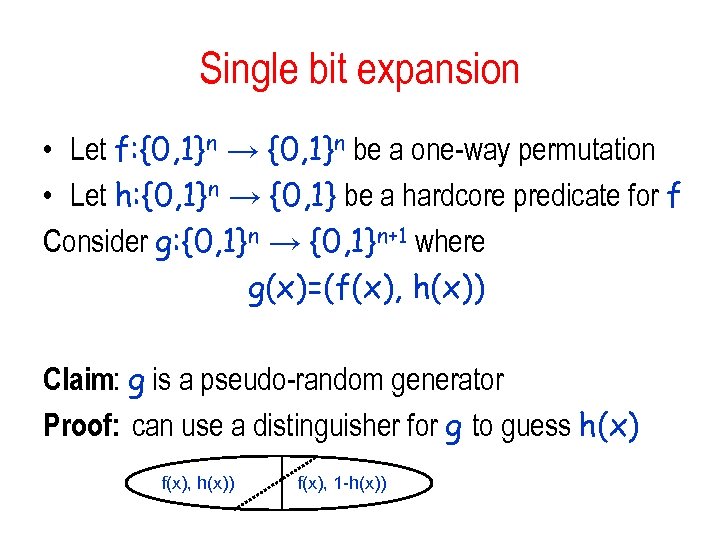

Single bit expansion • Let f: {0, 1}n → {0, 1}n be a one-way permutation • Let h: {0, 1}n → {0, 1} be a hardcore predicate for f Consider g: {0, 1}n → {0, 1}n+1 where g(x)=(f(x), h(x)) Claim: g is a pseudo-random generator Proof: can use a distinguisher for g to guess h(x) f(x), h(x)) f(x), 1 -h(x))

Single bit expansion • Let f: {0, 1}n → {0, 1}n be a one-way permutation • Let h: {0, 1}n → {0, 1} be a hardcore predicate for f Consider g: {0, 1}n → {0, 1}n+1 where g(x)=(f(x), h(x)) Claim: g is a pseudo-random generator Proof: can use a distinguisher for g to guess h(x) f(x), h(x)) f(x), 1 -h(x))

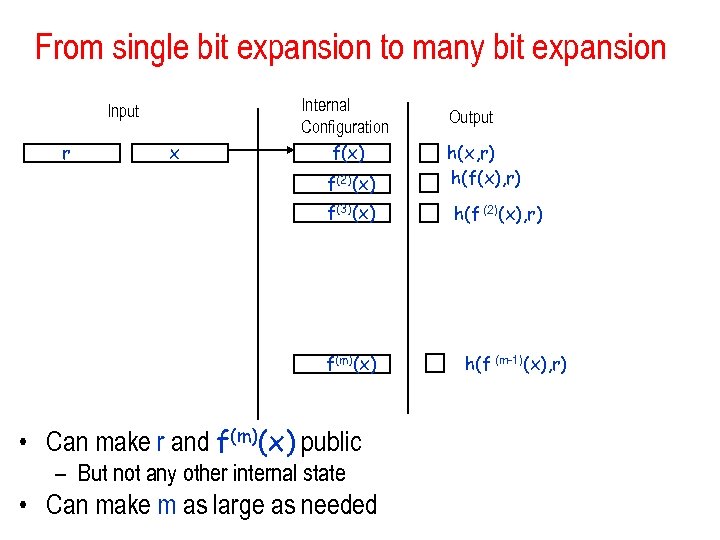

From single bit expansion to many bit expansion Input r x Internal Configuration f(x) f(2)(x) f(3)(x) f(m)(x) • Can make r and f(m)(x) public – But not any other internal state • Can make m as large as needed Output h(x, r) h(f(x), r) h(f (2)(x), r) h(f (m-1)(x), r)

From single bit expansion to many bit expansion Input r x Internal Configuration f(x) f(2)(x) f(3)(x) f(m)(x) • Can make r and f(m)(x) public – But not any other internal state • Can make m as large as needed Output h(x, r) h(f(x), r) h(f (2)(x), r) h(f (m-1)(x), r)

Two important techniques for showing pseudo-randomness • Hybrid argument • Next-bit prediction and pseudo-randomness

Two important techniques for showing pseudo-randomness • Hybrid argument • Next-bit prediction and pseudo-randomness

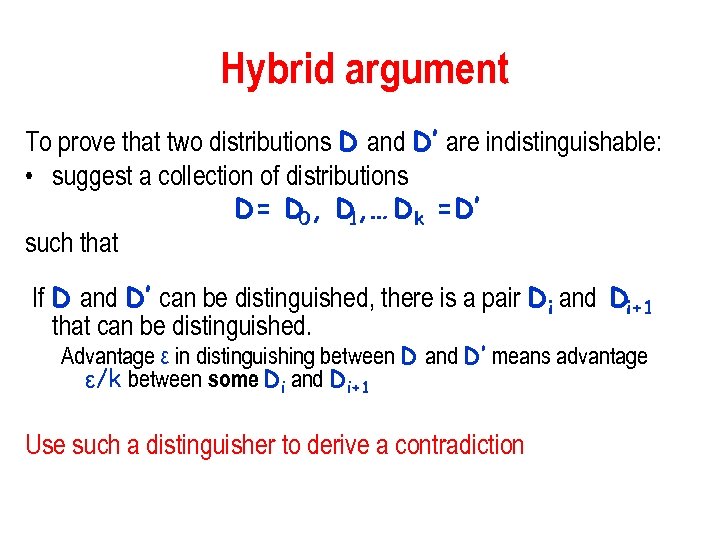

Hybrid argument To prove that two distributions D and D’ are indistinguishable: • suggest a collection of distributions D= D 0, D , … Dk =D’ 1 such that If D and D’ can be distinguished, there is a pair Di and Di+1 that can be distinguished. Advantage ε in distinguishing between D and D’ means advantage ε/k between some Di and Di+1 Use such a distinguisher to derive a contradiction

Hybrid argument To prove that two distributions D and D’ are indistinguishable: • suggest a collection of distributions D= D 0, D , … Dk =D’ 1 such that If D and D’ can be distinguished, there is a pair Di and Di+1 that can be distinguished. Advantage ε in distinguishing between D and D’ means advantage ε/k between some Di and Di+1 Use such a distinguisher to derive a contradiction

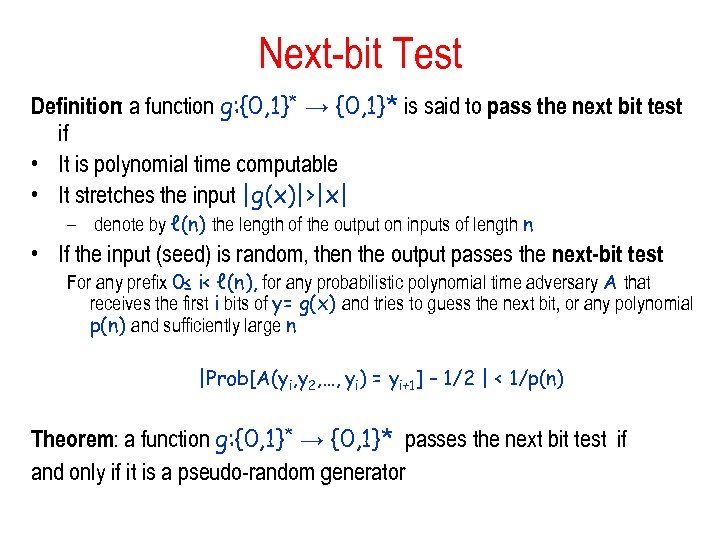

Next-bit Test Definition: a function g: {0, 1}* → {0, 1}* is said to pass the next bit test if • It is polynomial time computable • It stretches the input |g(x)|>|x| – denote by ℓ(n) the length of the output on inputs of length n • If the input (seed) is random, then the output passes the next-bit test For any prefix 0≤ i< ℓ(n), for any probabilistic polynomial time adversary A that receives the first i bits of y= g(x) and tries to guess the next bit, or any polynomial p(n) and sufficiently large n |Prob[A(yi, y 2, …, yi) = yi+1] – 1/2 | < 1/p(n) Theorem: a function g: {0, 1}* → {0, 1}* passes the next bit test if and only if it is a pseudo-random generator

Next-bit Test Definition: a function g: {0, 1}* → {0, 1}* is said to pass the next bit test if • It is polynomial time computable • It stretches the input |g(x)|>|x| – denote by ℓ(n) the length of the output on inputs of length n • If the input (seed) is random, then the output passes the next-bit test For any prefix 0≤ i< ℓ(n), for any probabilistic polynomial time adversary A that receives the first i bits of y= g(x) and tries to guess the next bit, or any polynomial p(n) and sufficiently large n |Prob[A(yi, y 2, …, yi) = yi+1] – 1/2 | < 1/p(n) Theorem: a function g: {0, 1}* → {0, 1}* passes the next bit test if and only if it is a pseudo-random generator

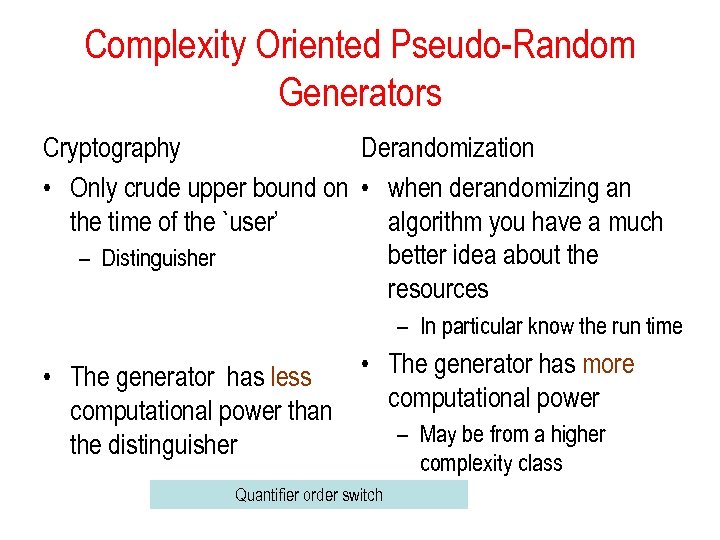

Complexity Oriented Pseudo-Random Generators Cryptography Derandomization • Only crude upper bound on • when derandomizing an the time of the `user’ algorithm you have a much better idea about the – Distinguisher resources – In particular know the run time • The generator has more • The generator has less computational power than – May be from a higher the distinguisher complexity class Quantifier order switch

Complexity Oriented Pseudo-Random Generators Cryptography Derandomization • Only crude upper bound on • when derandomizing an the time of the `user’ algorithm you have a much better idea about the – Distinguisher resources – In particular know the run time • The generator has more • The generator has less computational power than – May be from a higher the distinguisher complexity class Quantifier order switch

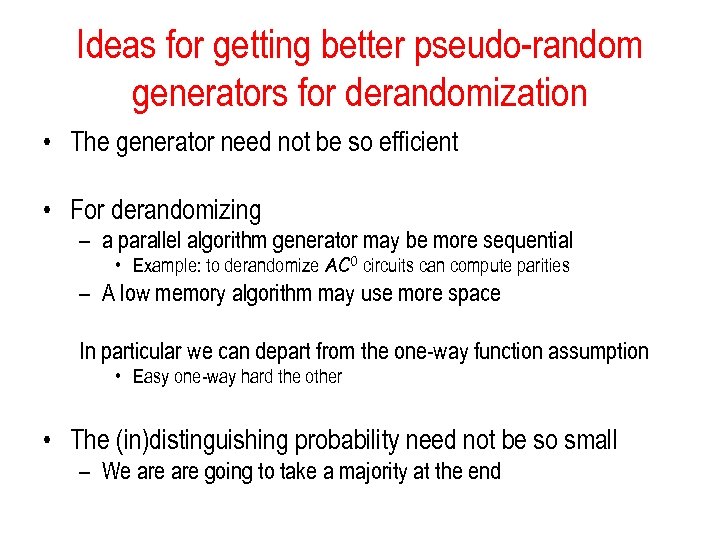

Ideas for getting better pseudo-random generators for derandomization • The generator need not be so efficient • For derandomizing – a parallel algorithm generator may be more sequential • Example: to derandomize AC 0 circuits can compute parities – A low memory algorithm may use more space In particular we can depart from the one-way function assumption • Easy one-way hard the other • The (in)distinguishing probability need not be so small – We are going to take a majority at the end

Ideas for getting better pseudo-random generators for derandomization • The generator need not be so efficient • For derandomizing – a parallel algorithm generator may be more sequential • Example: to derandomize AC 0 circuits can compute parities – A low memory algorithm may use more space In particular we can depart from the one-way function assumption • Easy one-way hard the other • The (in)distinguishing probability need not be so small – We are going to take a majority at the end

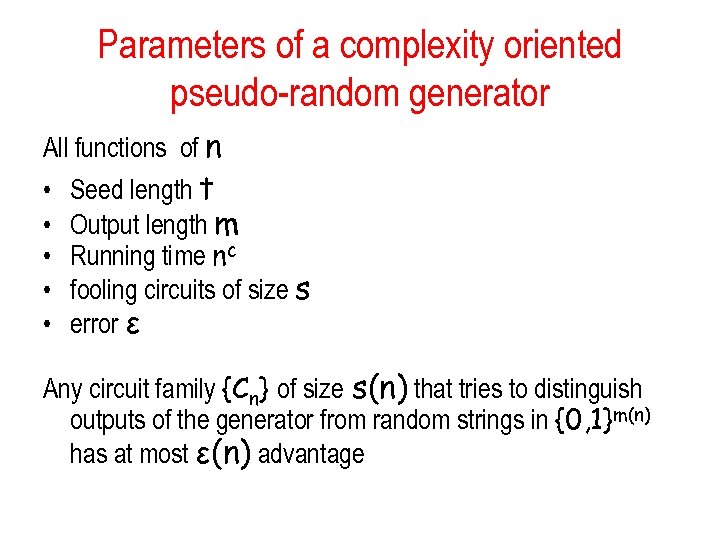

Parameters of a complexity oriented pseudo-random generator All functions of n • • • Seed length t Output length m Running time nc fooling circuits of size s error ε Any circuit family {Cn} of size s(n) that tries to distinguish outputs of the generator from random strings in {0, 1}m(n) has at most ε(n) advantage

Parameters of a complexity oriented pseudo-random generator All functions of n • • • Seed length t Output length m Running time nc fooling circuits of size s error ε Any circuit family {Cn} of size s(n) that tries to distinguish outputs of the generator from random strings in {0, 1}m(n) has at most ε(n) advantage

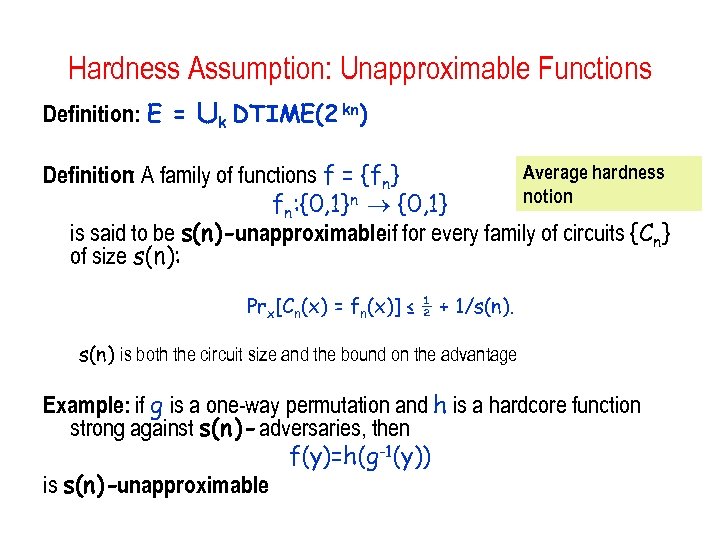

Hardness Assumption: Unapproximable Functions Definition: E = [k DTIME(2 kn) Average hardness Definition: A family of functions f = {fn} notion fn: {0, 1}n {0, 1} is said to be s(n)-unapproximableif for every family of circuits {Cn} of size s(n): Prx[Cn(x) = fn(x)] ≤ ½ + 1/s(n) is both the circuit size and the bound on the advantage Example: if g is a one-way permutation and h is a hardcore function strong against s(n)- adversaries, then f(y)=h(g-1(y)) is s(n)-unapproximable

Hardness Assumption: Unapproximable Functions Definition: E = [k DTIME(2 kn) Average hardness Definition: A family of functions f = {fn} notion fn: {0, 1}n {0, 1} is said to be s(n)-unapproximableif for every family of circuits {Cn} of size s(n): Prx[Cn(x) = fn(x)] ≤ ½ + 1/s(n) is both the circuit size and the bound on the advantage Example: if g is a one-way permutation and h is a hardcore function strong against s(n)- adversaries, then f(y)=h(g-1(y)) is s(n)-unapproximable

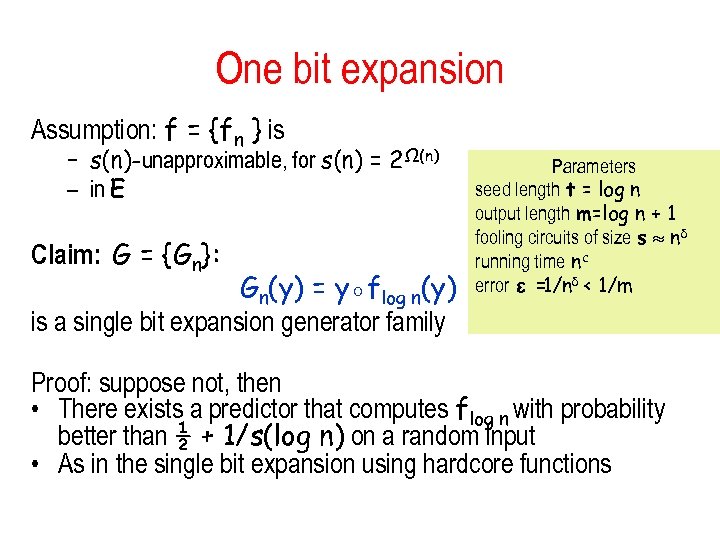

One bit expansion Assumption: f = {fn } is – s(n)-unapproximable, for s(n) = 2Ω(n) – in E Claim: G = {Gn}: Gn(y) = y◦flog n(y) is a single bit expansion generator family Parameters seed length t = log n output length m=log n + 1 fooling circuits of size s nδ running time nc error ε = δ < 1/m 1/n Proof: suppose not, then • There exists a predictor that computes flog n with probability better than ½ + 1/s(log n) on a random input • As in the single bit expansion using hardcore functions

One bit expansion Assumption: f = {fn } is – s(n)-unapproximable, for s(n) = 2Ω(n) – in E Claim: G = {Gn}: Gn(y) = y◦flog n(y) is a single bit expansion generator family Parameters seed length t = log n output length m=log n + 1 fooling circuits of size s nδ running time nc error ε = δ < 1/m 1/n Proof: suppose not, then • There exists a predictor that computes flog n with probability better than ½ + 1/s(log n) on a random input • As in the single bit expansion using hardcore functions

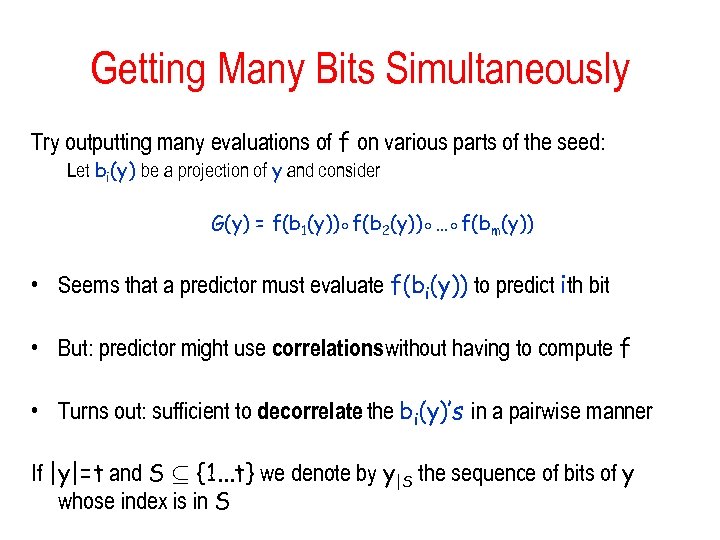

Getting Many Bits Simultaneously Try outputting many evaluations of f on various parts of the seed: Let bi(y) be a projection of y and consider G(y) = f(b 1(y))◦f(b 2(y))◦…◦f(bm(y)) • Seems that a predictor must evaluate f(bi(y)) to predict ith bit • But: predictor might use correlationswithout having to compute f • Turns out: sufficient to decorrelate the bi(y)’s in a pairwise manner If |y|=t and S µ {1. . . t} we denote by y|S the sequence of bits of y whose index is in S

Getting Many Bits Simultaneously Try outputting many evaluations of f on various parts of the seed: Let bi(y) be a projection of y and consider G(y) = f(b 1(y))◦f(b 2(y))◦…◦f(bm(y)) • Seems that a predictor must evaluate f(bi(y)) to predict ith bit • But: predictor might use correlationswithout having to compute f • Turns out: sufficient to decorrelate the bi(y)’s in a pairwise manner If |y|=t and S µ {1. . . t} we denote by y|S the sequence of bits of y whose index is in S

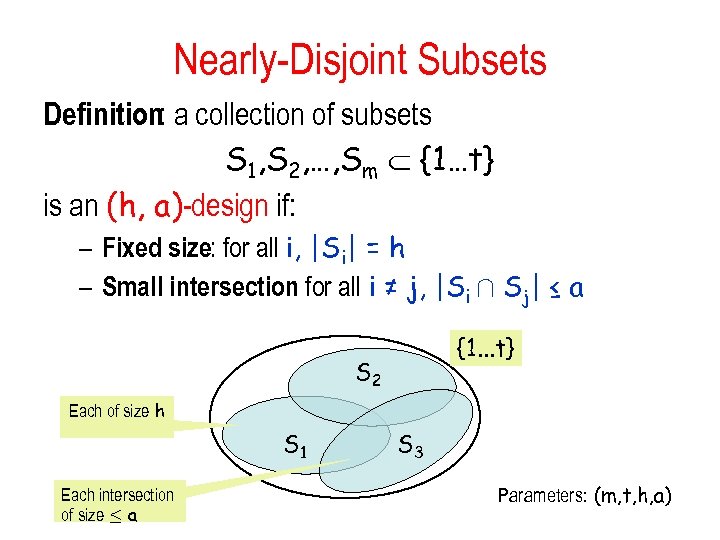

Nearly-Disjoint Subsets Definition: a collection of subsets S 1, S 2, …, Sm {1…t} is an (h, a)-design if: – Fixed size: for all i, |Si| = h – Small intersection for all i ≠ j, |Si Å Sj| ≤ a : {1. . . t} S 2 Each of size h S 1 Each intersection of size · a S 3 Parameters: (m, t, h, a)

Nearly-Disjoint Subsets Definition: a collection of subsets S 1, S 2, …, Sm {1…t} is an (h, a)-design if: – Fixed size: for all i, |Si| = h – Small intersection for all i ≠ j, |Si Å Sj| ≤ a : {1. . . t} S 2 Each of size h S 1 Each intersection of size · a S 3 Parameters: (m, t, h, a)

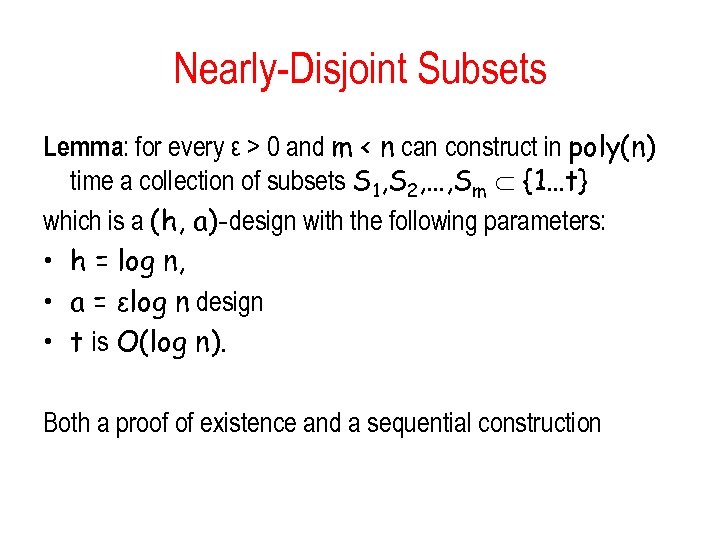

Nearly-Disjoint Subsets Lemma: for every ε > 0 and m < n can construct in poly(n) time a collection of subsets S 1, S 2, …, Sm {1…t} which is a (h, a)-design with the following parameters: • h = log n, • a = εlog n design • t is O(log n). Both a proof of existence and a sequential construction

Nearly-Disjoint Subsets Lemma: for every ε > 0 and m < n can construct in poly(n) time a collection of subsets S 1, S 2, …, Sm {1…t} which is a (h, a)-design with the following parameters: • h = log n, • a = εlog n design • t is O(log n). Both a proof of existence and a sequential construction

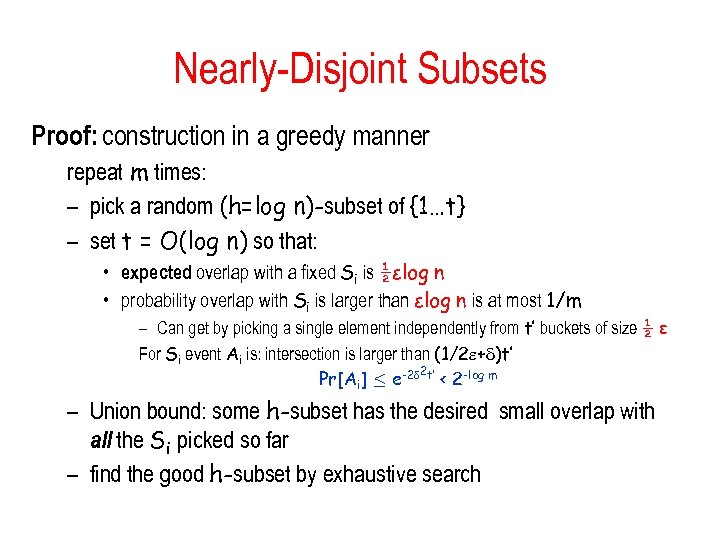

Nearly-Disjoint Subsets Proof: construction in a greedy manner repeat m times: – pick a random (h=log n)-subset of {1…t} – set t = O(log n) so that: • expected overlap with a fixed Si is ½εlog n • probability overlap with Si is larger than εlog n is at most 1/m – Can get by picking a single element independently from t’ buckets of size ½ ε For Si event Ai is: intersection is larger than (1/2 + )t’ 2 Pr[Ai] · e-2 t’ < 2 -log m – Union bound: some h-subset has the desired small overlap with all the Si picked so far – find the good h-subset by exhaustive search

Nearly-Disjoint Subsets Proof: construction in a greedy manner repeat m times: – pick a random (h=log n)-subset of {1…t} – set t = O(log n) so that: • expected overlap with a fixed Si is ½εlog n • probability overlap with Si is larger than εlog n is at most 1/m – Can get by picking a single element independently from t’ buckets of size ½ ε For Si event Ai is: intersection is larger than (1/2 + )t’ 2 Pr[Ai] · e-2 t’ < 2 -log m – Union bound: some h-subset has the desired small overlap with all the Si picked so far – find the good h-subset by exhaustive search

Other construction of designs • Based on error correcting codes • Simple construction: based on polynomials

Other construction of designs • Based on error correcting codes • Simple construction: based on polynomials

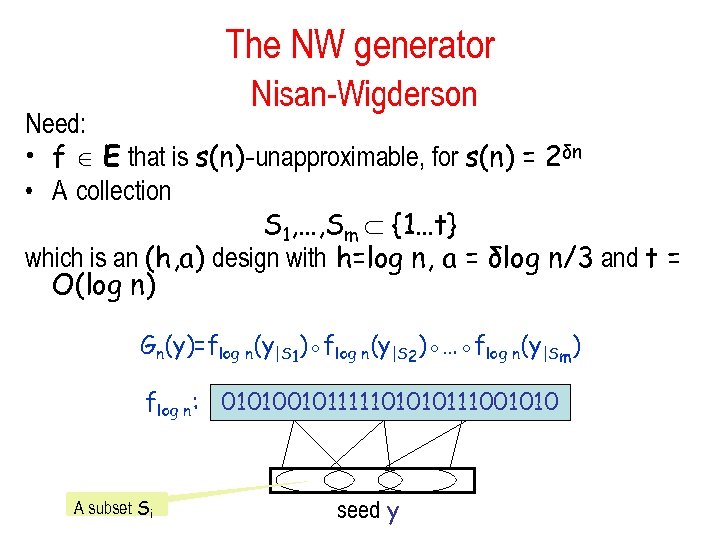

The NW generator Nisan-Wigderson Need: • f E that is s(n)-unapproximable, for s(n) = 2δn • A collection S 1, …, Sm {1…t} which is an (h, a) design with h=log n, a = δlog n/3 and t = O(log n) Gn(y)=flog n(y|S 1)◦flog n(y|S 2)◦…◦flog n(y|Sm) flog n: 010100101111101010111001010 A subset Si seed y

The NW generator Nisan-Wigderson Need: • f E that is s(n)-unapproximable, for s(n) = 2δn • A collection S 1, …, Sm {1…t} which is an (h, a) design with h=log n, a = δlog n/3 and t = O(log n) Gn(y)=flog n(y|S 1)◦flog n(y|S 2)◦…◦flog n(y|Sm) flog n: 010100101111101010111001010 A subset Si seed y

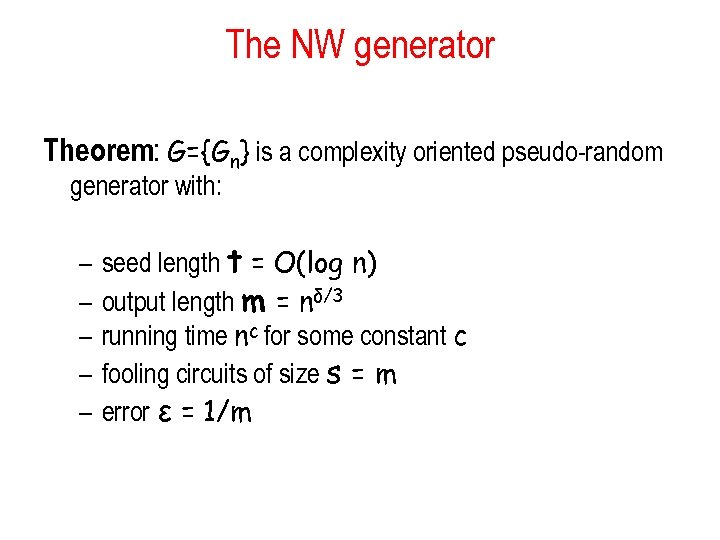

The NW generator Theorem: G={Gn} is a complexity oriented pseudo-random generator with: – – – seed length t = O(log n) output length m = nδ/3 running time nc for some constant c fooling circuits of size s = m error ε = 1/m

The NW generator Theorem: G={Gn} is a complexity oriented pseudo-random generator with: – – – seed length t = O(log n) output length m = nδ/3 running time nc for some constant c fooling circuits of size s = m error ε = 1/m

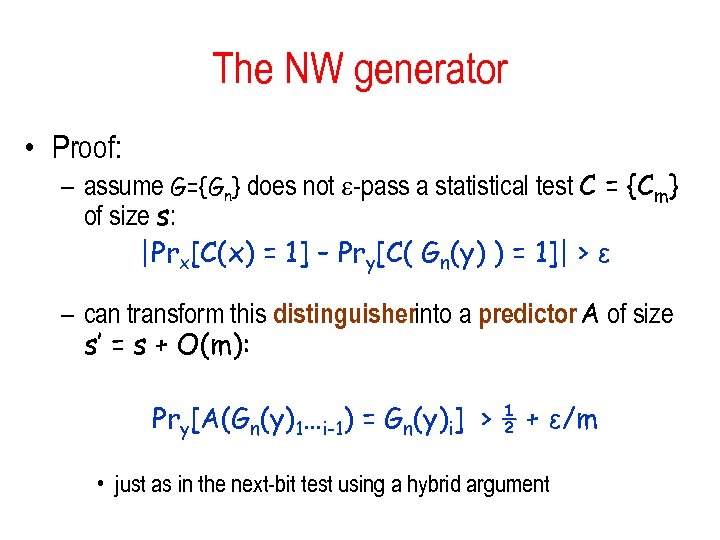

The NW generator • Proof: – assume G={Gn} does not -pass a statistical test C = {Cm} of size s: |Prx[C(x) = 1] – Pry[C( Gn(y) ) = 1]| > ε – can transform this distinguisherinto a predictor A of size s’ = s + O(m): Pry[A(Gn(y)1…i-1) = Gn(y)i] > ½ + ε/m • just as in the next-bit test using a hybrid argument

The NW generator • Proof: – assume G={Gn} does not -pass a statistical test C = {Cm} of size s: |Prx[C(x) = 1] – Pry[C( Gn(y) ) = 1]| > ε – can transform this distinguisherinto a predictor A of size s’ = s + O(m): Pry[A(Gn(y)1…i-1) = Gn(y)i] > ½ + ε/m • just as in the next-bit test using a hybrid argument

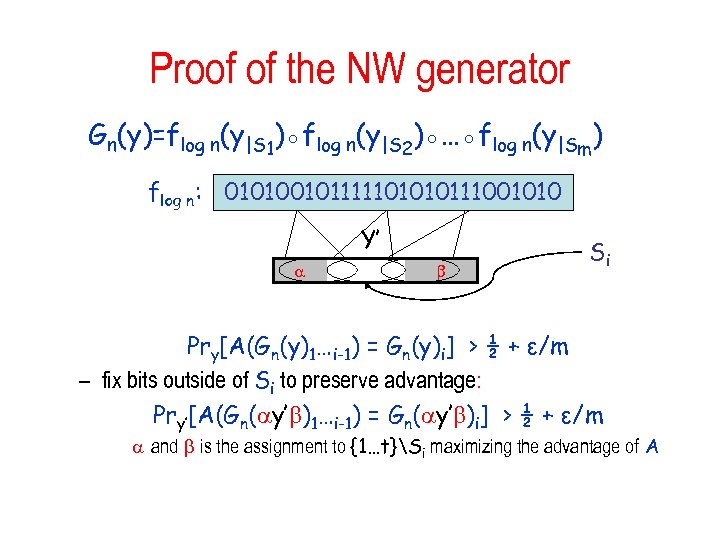

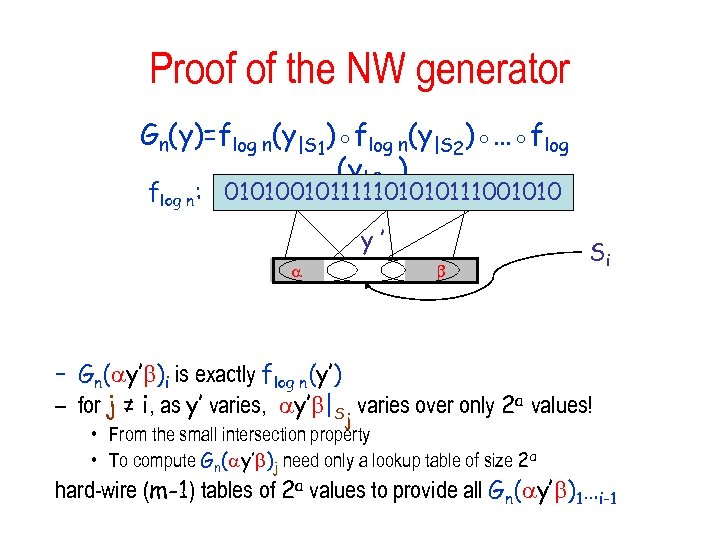

Proof of the NW generator Gn(y)=flog n(y|S 1)◦flog n(y|S 2)◦…◦flog n(y|Sm) flog n: 010100101111101010111001010 Y’ Si Pry[A(Gn(y)1…i-1) = Gn(y)i] > ½ + ε/m – fix bits outside of Si to preserve advantage: Pry’[A(Gn( y’ )1…i-1) = Gn( y’ )i] > ½ + ε/m and is the assignment to {1…t}Si maximizing the advantage of A

Proof of the NW generator Gn(y)=flog n(y|S 1)◦flog n(y|S 2)◦…◦flog n(y|Sm) flog n: 010100101111101010111001010 Y’ Si Pry[A(Gn(y)1…i-1) = Gn(y)i] > ½ + ε/m – fix bits outside of Si to preserve advantage: Pry’[A(Gn( y’ )1…i-1) = Gn( y’ )i] > ½ + ε/m and is the assignment to {1…t}Si maximizing the advantage of A

Proof of the NW generator Gn(y)=flog n(y|S 1)◦flog n(y|S 2)◦…◦flog n(y|Sm) flog n: 010100101111101010111001010 y’ Si – Gn( y’ )i is exactly flog n(y’) – for j ≠ i, as y’ varies, y’ |Sj varies over only 2 a values! • From the small intersection property • To compute Gn( y’ )j need only a lookup table of size 2 a hard-wire (m-1) tables of 2 a values to provide all Gn( y’ )1…i-1

Proof of the NW generator Gn(y)=flog n(y|S 1)◦flog n(y|S 2)◦…◦flog n(y|Sm) flog n: 010100101111101010111001010 y’ Si – Gn( y’ )i is exactly flog n(y’) – for j ≠ i, as y’ varies, y’ |Sj varies over only 2 a values! • From the small intersection property • To compute Gn( y’ )j need only a lookup table of size 2 a hard-wire (m-1) tables of 2 a values to provide all Gn( y’ )1…i-1

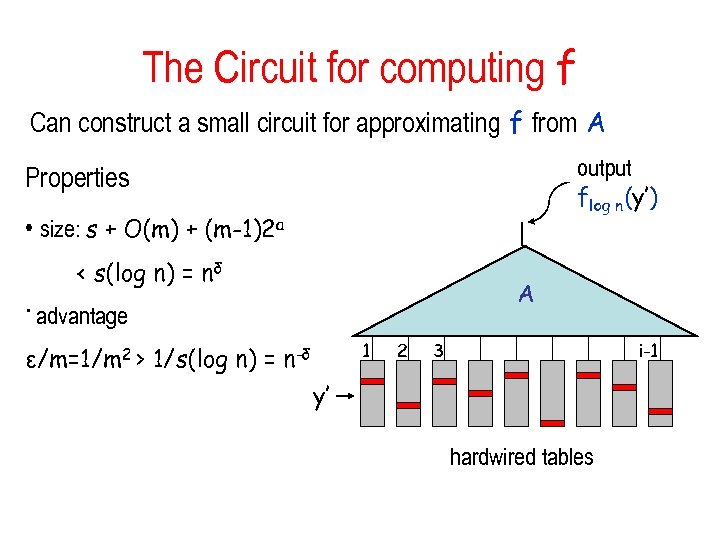

The Circuit for computing f Can construct a small circuit for approximating f from A output flog n(y’) Properties • size: s + O(m) + (m-1)2 a < s(log n) = nδ A • advantage 1 ε/m=1/m 2 > 1/s(log n) = n-δ 2 3 i-1 y’ hardwired tables

The Circuit for computing f Can construct a small circuit for approximating f from A output flog n(y’) Properties • size: s + O(m) + (m-1)2 a < s(log n) = nδ A • advantage 1 ε/m=1/m 2 > 1/s(log n) = n-δ 2 3 i-1 y’ hardwired tables

References • Theory of cryptographic Pseudo-randomness developed by: – Blum and Micali, next bit test, 1982 – Computational indistinguishability, Yao, 1982, • The NW generator: – Nisan and Wigderson, Hardness vs. Randomness, JCSS, 1994. – Some of the slides on the topic: Chris Umans’ course Lecture 9

References • Theory of cryptographic Pseudo-randomness developed by: – Blum and Micali, next bit test, 1982 – Computational indistinguishability, Yao, 1982, • The NW generator: – Nisan and Wigderson, Hardness vs. Randomness, JCSS, 1994. – Some of the slides on the topic: Chris Umans’ course Lecture 9