94aa47f07a6fe2e6808c9b9272b2398e.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 30

COMPETITION vs. COORDINATION: THE ANALYTICS OF OPEN ACCESS WITH ILLUSTRATIONS FROM RAILROADS José A. Gomez-Ibañez Annual Regulatory Conference of the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission, Surfers’ Paradise, Queensland July 29, 2010

COMPETITION vs. COORDINATION: THE ANALYTICS OF OPEN ACCESS WITH ILLUSTRATIONS FROM RAILROADS José A. Gomez-Ibañez Annual Regulatory Conference of the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission, Surfers’ Paradise, Queensland July 29, 2010

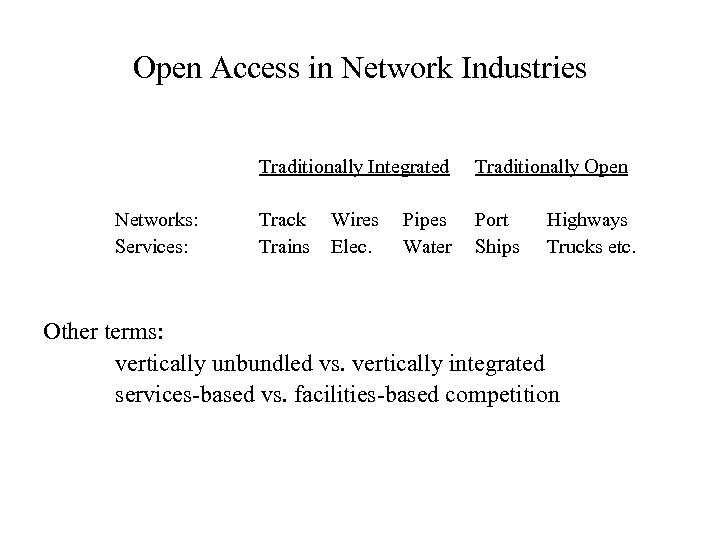

Open Access in Network Industries Traditionally Integrated Networks: Services: Traditionally Open Track Trains Port Ships Wires Elec. Pipes Water Highways Trucks etc. Other terms: vertically unbundled vs. vertically integrated services-based vs. facilities-based competition

Open Access in Network Industries Traditionally Integrated Networks: Services: Traditionally Open Track Trains Port Ships Wires Elec. Pipes Water Highways Trucks etc. Other terms: vertically unbundled vs. vertically integrated services-based vs. facilities-based competition

Competition-Coordination Tradeoff (Ronald Coase, 1927) Integration decision (make or buy) Buy normally preferred Make (integrate) if: • Durable, relationship-specific assets important • Needs too complex and uncertain to contract Forced open access or unbundling: competition-coordination tradeoff

Competition-Coordination Tradeoff (Ronald Coase, 1927) Integration decision (make or buy) Buy normally preferred Make (integrate) if: • Durable, relationship-specific assets important • Needs too complex and uncertain to contract Forced open access or unbundling: competition-coordination tradeoff

Outline • Simple Analytic Model of Tradeoff • Coordination costs important • The Tradeoff in Railroads • Published empirical estimates • Case studies of coordination costs – Australia: Complexity of the interface – Europe: Network capacity and user diversity – North America: Reciprocity and selectivity • Applications

Outline • Simple Analytic Model of Tradeoff • Coordination costs important • The Tradeoff in Railroads • Published empirical estimates • Case studies of coordination costs – Australia: Complexity of the interface – Europe: Network capacity and user diversity – North America: Reciprocity and selectivity • Applications

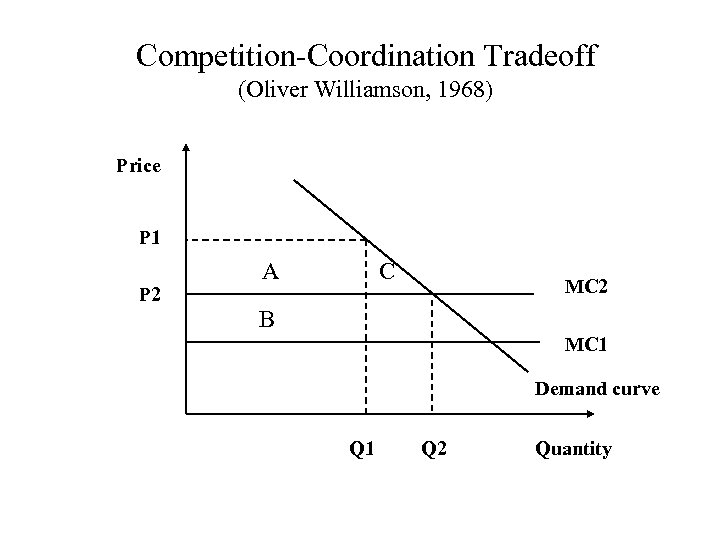

Competition-Coordination Tradeoff (Oliver Williamson, 1968) Price P 1 P 2 A C MC 2 B MC 1 Demand curve Q 1 Q 2 Quantity

Competition-Coordination Tradeoff (Oliver Williamson, 1968) Price P 1 P 2 A C MC 2 B MC 1 Demand curve Q 1 Q 2 Quantity

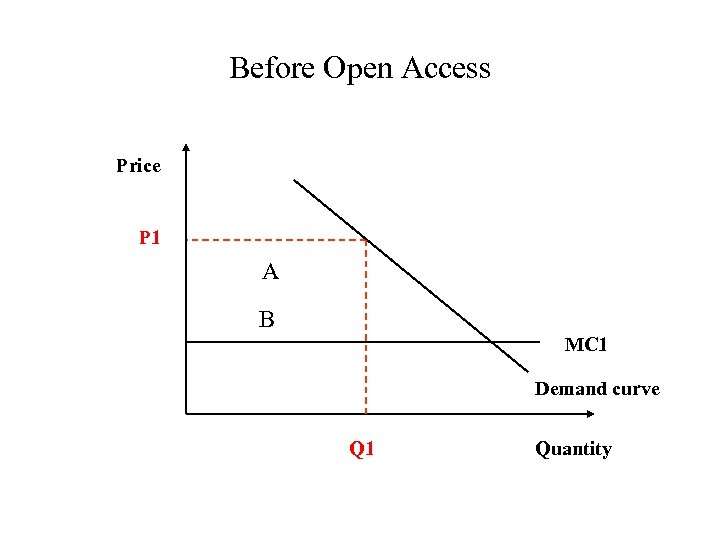

Before Open Access Price P 1 A B MC 1 Demand curve Q 1 Quantity

Before Open Access Price P 1 A B MC 1 Demand curve Q 1 Quantity

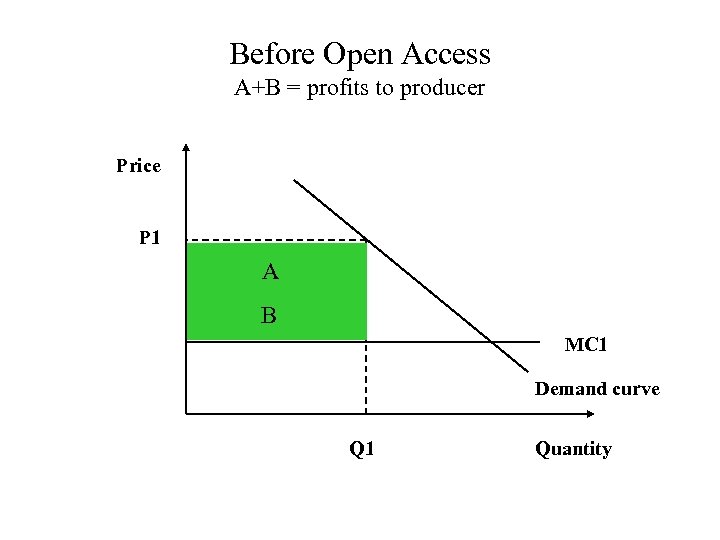

Before Open Access A+B = profits to producer Price P 1 A B MC 1 Demand curve Q 1 Quantity

Before Open Access A+B = profits to producer Price P 1 A B MC 1 Demand curve Q 1 Quantity

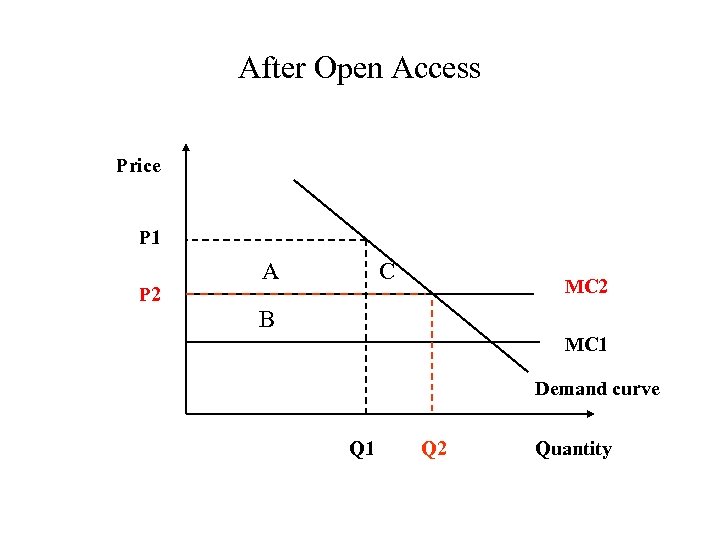

After Open Access Price P 1 P 2 A C MC 2 B MC 1 Demand curve Q 1 Q 2 Quantity

After Open Access Price P 1 P 2 A C MC 2 B MC 1 Demand curve Q 1 Q 2 Quantity

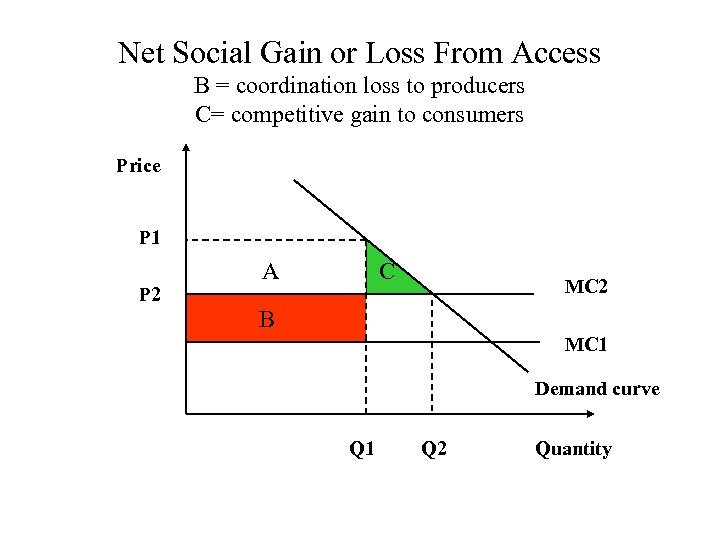

Net Social Gain or Loss From Access B = coordination loss to producers C= competitive gain to consumers Price P 1 P 2 A C MC 2 B MC 1 Demand curve Q 1 Q 2 Quantity

Net Social Gain or Loss From Access B = coordination loss to producers C= competitive gain to consumers Price P 1 P 2 A C MC 2 B MC 1 Demand curve Q 1 Q 2 Quantity

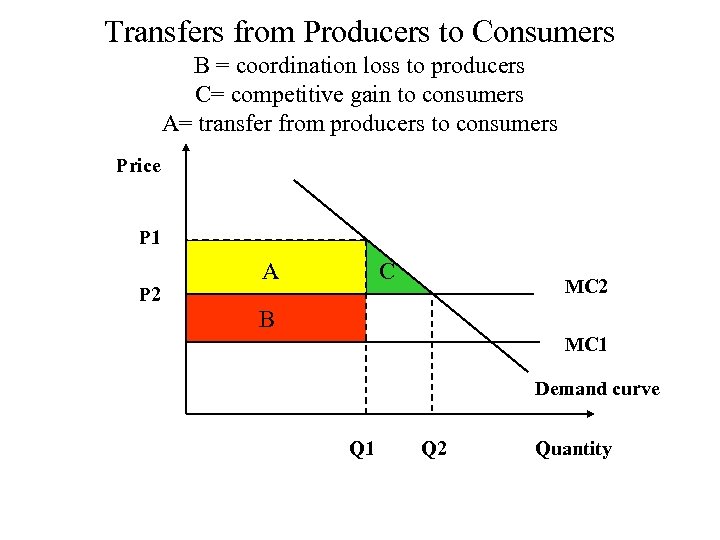

Transfers from Producers to Consumers B = coordination loss to producers C= competitive gain to consumers A= transfer from producers to consumers Price P 1 P 2 A C MC 2 B MC 1 Demand curve Q 1 Q 2 Quantity

Transfers from Producers to Consumers B = coordination loss to producers C= competitive gain to consumers A= transfer from producers to consumers Price P 1 P 2 A C MC 2 B MC 1 Demand curve Q 1 Q 2 Quantity

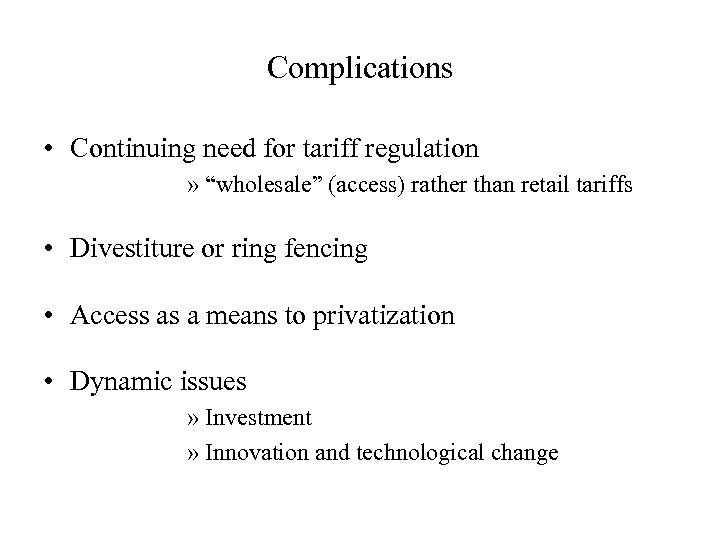

Complications • Continuing need for tariff regulation » “wholesale” (access) rather than retail tariffs • Divestiture or ring fencing • Access as a means to privatization • Dynamic issues » Investment » Innovation and technological change

Complications • Continuing need for tariff regulation » “wholesale” (access) rather than retail tariffs • Divestiture or ring fencing • Access as a means to privatization • Dynamic issues » Investment » Innovation and technological change

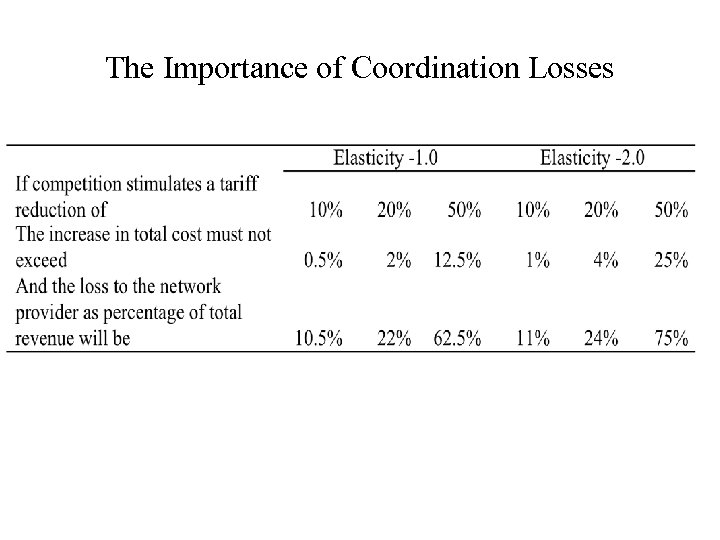

The Importance of Coordination Losses

The Importance of Coordination Losses

Railroads: Published Estimates • Competitive gains • US freight railroads: 10% to 20% tariff reduction if second carrier • Passenger railroads: no estimates because subsidies • Coordination losses • US freight railroads: 5% to 40% increase in costs • European railroads: mixed results

Railroads: Published Estimates • Competitive gains • US freight railroads: 10% to 20% tariff reduction if second carrier • Passenger railroads: no estimates because subsidies • Coordination losses • US freight railroads: 5% to 40% increase in costs • European railroads: mixed results

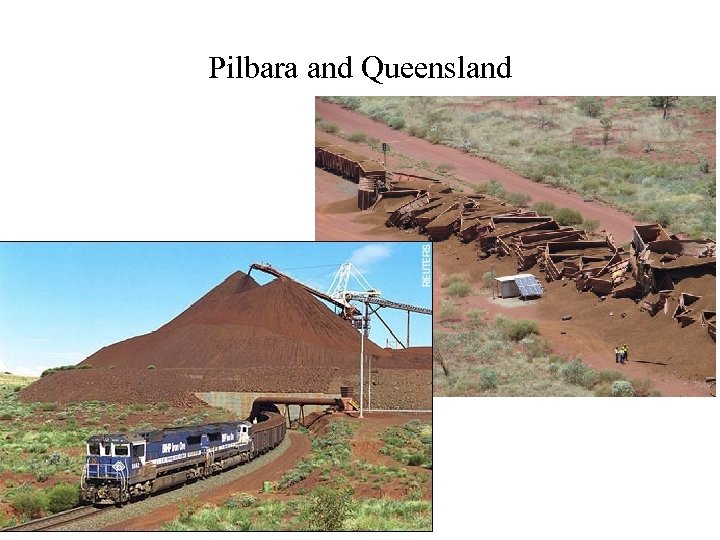

Australia: Interface Complexity • Access the norm beginning 1995 • Most track infrastructure still government owned • Most train operators now private • Pilbara iron ore railroads (integrated & private) • BHP and Rio Tinto • Smaller miners want access • Queensland coal railroads (integrated & government) • Miners oppose privatization as vertically integrated railroad

Australia: Interface Complexity • Access the norm beginning 1995 • Most track infrastructure still government owned • Most train operators now private • Pilbara iron ore railroads (integrated & private) • BHP and Rio Tinto • Smaller miners want access • Queensland coal railroads (integrated & government) • Miners oppose privatization as vertically integrated railroad

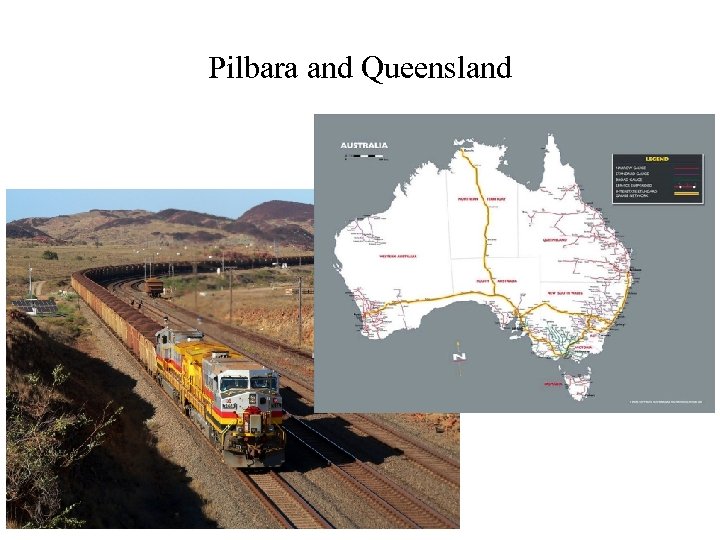

Pilbara and Queensland

Pilbara and Queensland

Pilbara and Queensland Heavy haul railroads • Heavy axle weights • 30 to 40 tons vs. 20 to 25 tons • Wheel-rail interface • Part of complex supply chain • Mines, stockpiles, ports, ships in addition to trains and track • Dispatching and capacity investment

Pilbara and Queensland Heavy haul railroads • Heavy axle weights • 30 to 40 tons vs. 20 to 25 tons • Wheel-rail interface • Part of complex supply chain • Mines, stockpiles, ports, ships in addition to trains and track • Dispatching and capacity investment

Pilbara and Queensland

Pilbara and Queensland

Europe: Network Capacity and User Diversity • EC requirements • Open access for many train services beginning 1991 • Separation of infrastructure from train operations • Continental Europe: few lessons • Relatively few added services • Infrastructure companies government owned and many heavily subsidized

Europe: Network Capacity and User Diversity • EC requirements • Open access for many train services beginning 1991 • Separation of infrastructure from train operations • Continental Europe: few lessons • Relatively few added services • Infrastructure companies government owned and many heavily subsidized

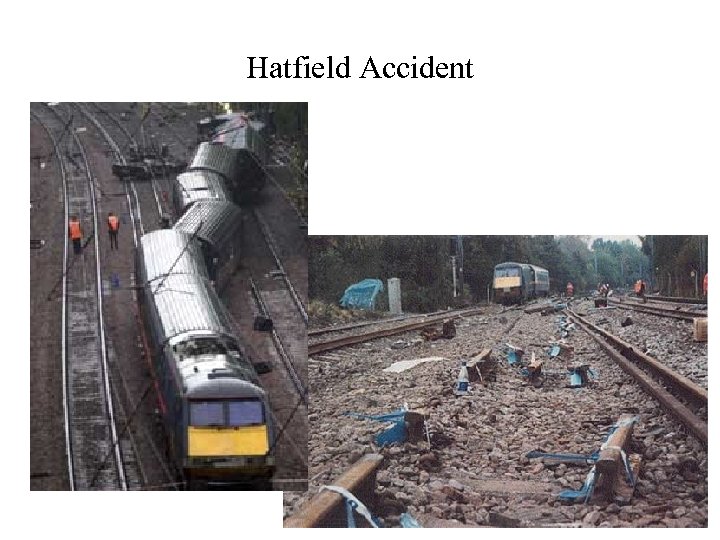

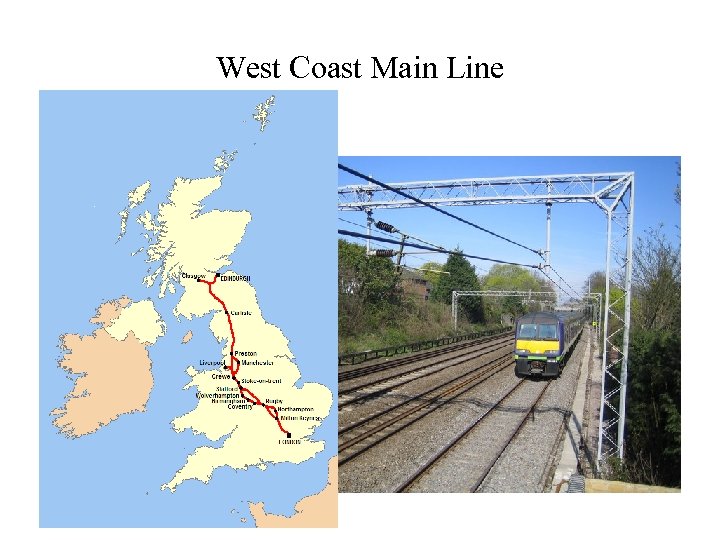

Britain • British Rail restructuring and privatization (1994 -97) • One infrastructure company (Railtrack), 25 passenger train companies, etc. • System of access charges and penalties • Low fee per added train encourages more trains • Industry regulator orders Railtrack and train operating companies to negotiate over capacity improvements • Railtrack bankruptcy (2000) • Hatfield accident • West Coast Main Line upgrade

Britain • British Rail restructuring and privatization (1994 -97) • One infrastructure company (Railtrack), 25 passenger train companies, etc. • System of access charges and penalties • Low fee per added train encourages more trains • Industry regulator orders Railtrack and train operating companies to negotiate over capacity improvements • Railtrack bankruptcy (2000) • Hatfield accident • West Coast Main Line upgrade

Hatfield Accident

Hatfield Accident

West Coast Main Line

West Coast Main Line

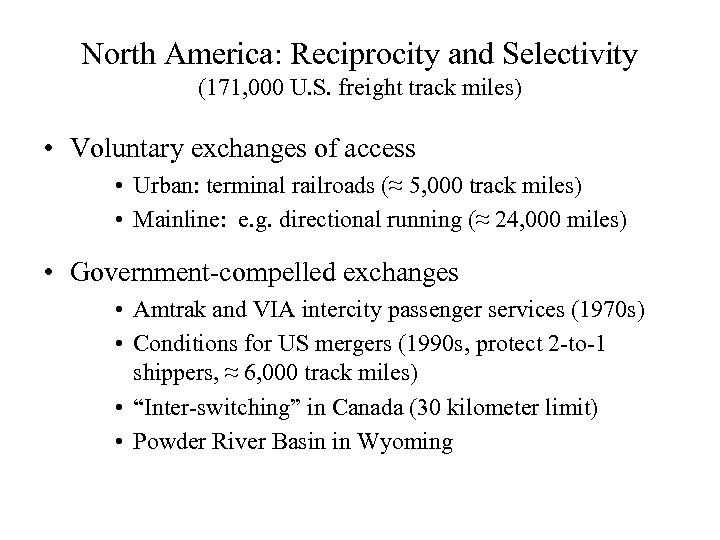

North America: Reciprocity and Selectivity (171, 000 U. S. freight track miles) • Voluntary exchanges of access • Urban: terminal railroads (≈ 5, 000 track miles) • Mainline: e. g. directional running (≈ 24, 000 miles) • Government-compelled exchanges • Amtrak and VIA intercity passenger services (1970 s) • Conditions for US mergers (1990 s, protect 2 -to-1 shippers, ≈ 6, 000 track miles) • “Inter-switching” in Canada (30 kilometer limit) • Powder River Basin in Wyoming

North America: Reciprocity and Selectivity (171, 000 U. S. freight track miles) • Voluntary exchanges of access • Urban: terminal railroads (≈ 5, 000 track miles) • Mainline: e. g. directional running (≈ 24, 000 miles) • Government-compelled exchanges • Amtrak and VIA intercity passenger services (1970 s) • Conditions for US mergers (1990 s, protect 2 -to-1 shippers, ≈ 6, 000 track miles) • “Inter-switching” in Canada (30 kilometer limit) • Powder River Basin in Wyoming

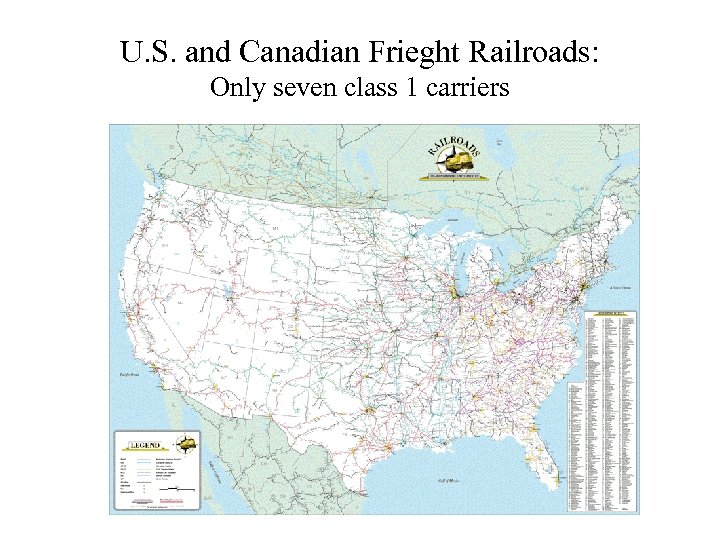

U. S. and Canadian Frieght Railroads: Only seven class 1 carriers

U. S. and Canadian Frieght Railroads: Only seven class 1 carriers

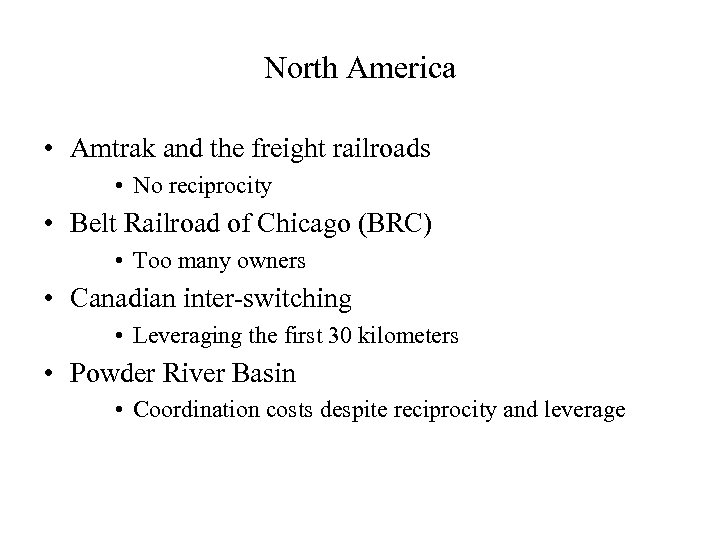

North America • Amtrak and the freight railroads • No reciprocity • Belt Railroad of Chicago (BRC) • Too many owners • Canadian inter-switching • Leveraging the first 30 kilometers • Powder River Basin • Coordination costs despite reciprocity and leverage

North America • Amtrak and the freight railroads • No reciprocity • Belt Railroad of Chicago (BRC) • Too many owners • Canadian inter-switching • Leveraging the first 30 kilometers • Powder River Basin • Coordination costs despite reciprocity and leverage

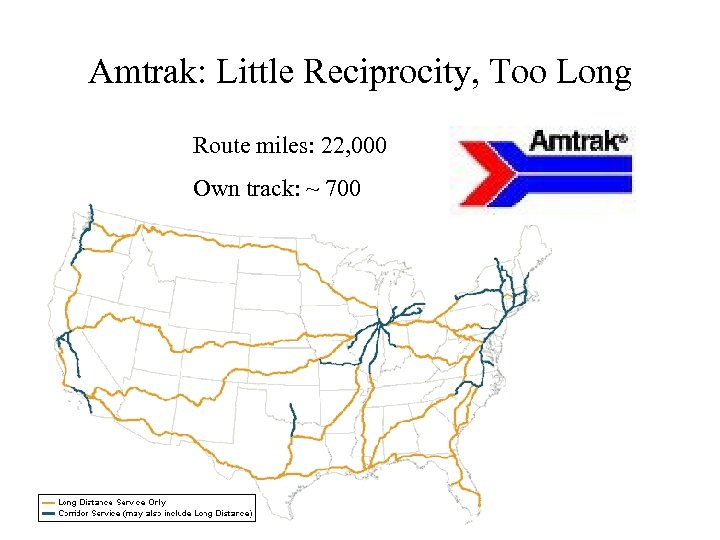

Amtrak: Little Reciprocity, Too Long Route miles: 22, 000 Own track: ~ 700

Amtrak: Little Reciprocity, Too Long Route miles: 22, 000 Own track: ~ 700

Belt Railway Company of Chicago: Six Owners

Belt Railway Company of Chicago: Six Owners

Canadian Inter-switching: Reciprocal, Short

Canadian Inter-switching: Reciprocal, Short

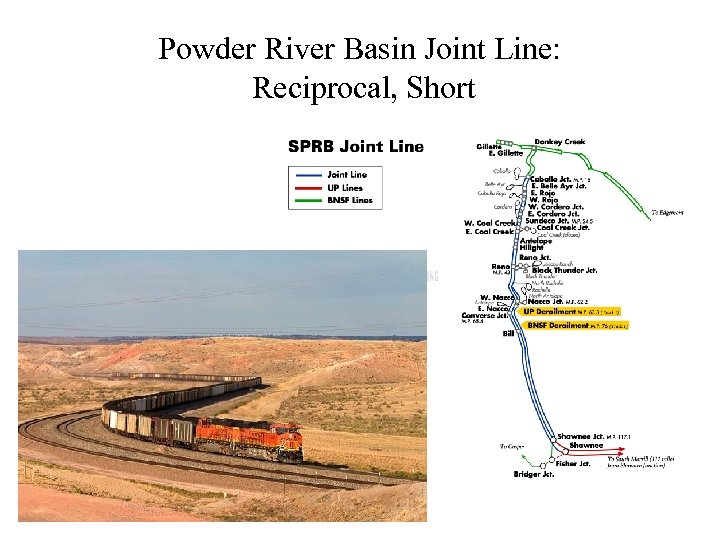

Powder River Basin Joint Line: Reciprocal, Short

Powder River Basin Joint Line: Reciprocal, Short

Conclusions • Access a competition-coordination tradeoff • Often significant competition already • A little lost coordination offsets a fair amount of increased competition • Coordination losses higher • • • More complex and sensitive the provider-user interface Network is close to capacity Access seekers have diverse needs Little reciprocity in access rights Rights are broad rather than selective

Conclusions • Access a competition-coordination tradeoff • Often significant competition already • A little lost coordination offsets a fair amount of increased competition • Coordination losses higher • • • More complex and sensitive the provider-user interface Network is close to capacity Access seekers have diverse needs Little reciprocity in access rights Rights are broad rather than selective

Applications to Other Industries • Road vs. rail • Vehicle-highway interface more forgiving • Competitive benefits of highway access greater • Telecommunications • “Short” access often important (poles and towers) • Voice telephony vs. broadband – Competitive benefit has declined significantly with both – Broadband greater pressure for capacity – Broadband interface more complex and changing

Applications to Other Industries • Road vs. rail • Vehicle-highway interface more forgiving • Competitive benefits of highway access greater • Telecommunications • “Short” access often important (poles and towers) • Voice telephony vs. broadband – Competitive benefit has declined significantly with both – Broadband greater pressure for capacity – Broadband interface more complex and changing