9351bcefc4f211fc9ee138be261d8530.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 82

Comparative analysis: principles and approaches Course European Social Policy J. R. Grote 27 April 2009 3 Comparative analysis

Comparative analysis: principles and approaches Course European Social Policy J. R. Grote 27 April 2009 3 Comparative analysis

Comparative analysis: principles and approaches n n n n Methods typically used to study policies Typical questions Comparative Politics defined Types of comparative analysis Why study Comparative Politics? Pre-history and history of Comparative Politics Different theoretical perspectives in comparing social policies Core problems of Comparative Analysis Analyzing Welfare States: different research strategies Methodological considerations Comparative Analysis Example 1: Varieties of Capitalism Comparative Analysis Example 2: Worlds and Families of Nations Comparative Analysis Example 3: Quality of Life in Europe Questions to be discussed 3 Comparative analysis 2

Comparative analysis: principles and approaches n n n n Methods typically used to study policies Typical questions Comparative Politics defined Types of comparative analysis Why study Comparative Politics? Pre-history and history of Comparative Politics Different theoretical perspectives in comparing social policies Core problems of Comparative Analysis Analyzing Welfare States: different research strategies Methodological considerations Comparative Analysis Example 1: Varieties of Capitalism Comparative Analysis Example 2: Worlds and Families of Nations Comparative Analysis Example 3: Quality of Life in Europe Questions to be discussed 3 Comparative analysis 2

Overview of methods frequently used to study (social) policies n n n n Case studies (in-depth „thick“ description) Event analysis Statistical data analysis Interviews Process analysis Representative surveys / Public opinion polls Expert surveys / Focus groups Comparative analysis (broad-based analysis of variables and patterns across policies, policy domains, national systems and regions) Case studies are more culturally specific, allow for more insight into idiosyncratic patterns and for inductive theoretical explanation. Comparative analysis enables learning from natural experiments. It tends to be more rigid and selective in terms of data to be processed. 3 Comparative analysis 3

Overview of methods frequently used to study (social) policies n n n n Case studies (in-depth „thick“ description) Event analysis Statistical data analysis Interviews Process analysis Representative surveys / Public opinion polls Expert surveys / Focus groups Comparative analysis (broad-based analysis of variables and patterns across policies, policy domains, national systems and regions) Case studies are more culturally specific, allow for more insight into idiosyncratic patterns and for inductive theoretical explanation. Comparative analysis enables learning from natural experiments. It tends to be more rigid and selective in terms of data to be processed. 3 Comparative analysis 3

Typical questions at the heart of the field of Comparative Politics n n n n Why are some countries poor and others wealthier? What enables some countries to "make it" in the modern world while others remain locked in poverty? Why are the poorer countries more inclined to be governed autocratically while the richer countries are democratic? What accounts for the regional, cultural, and geographic differences that exist? What are the politics of the transition from underdevelopment to development and what helps stimulate and sustain that process? What are the internal social and political conditions as well as the international situations of these various countries that explain the similarities as well as the differences? What are the patterns that help account for the emergence of democratic as distinct from Marxist-Leninist political systems? 3 Comparative analysis 4

Typical questions at the heart of the field of Comparative Politics n n n n Why are some countries poor and others wealthier? What enables some countries to "make it" in the modern world while others remain locked in poverty? Why are the poorer countries more inclined to be governed autocratically while the richer countries are democratic? What accounts for the regional, cultural, and geographic differences that exist? What are the politics of the transition from underdevelopment to development and what helps stimulate and sustain that process? What are the internal social and political conditions as well as the international situations of these various countries that explain the similarities as well as the differences? What are the patterns that help account for the emergence of democratic as distinct from Marxist-Leninist political systems? 3 Comparative analysis 4

Comparative Politics defined n Comparative Politics involves the systematic study and comparison of the world's political systems. n It seeks to explain differences between as well as similarities among countries. n It is particularly interested in exploring patterns, processes, and regularities among political systems. n It looks for trends, for changes in patterns; and it tries to develop general propositions or hypotheses that describe and explain these trends. n Comparative Politics covers a broad range of topics. The field has no one single focus. Different scholars have different preferences. 3 Comparative analysis 5

Comparative Politics defined n Comparative Politics involves the systematic study and comparison of the world's political systems. n It seeks to explain differences between as well as similarities among countries. n It is particularly interested in exploring patterns, processes, and regularities among political systems. n It looks for trends, for changes in patterns; and it tries to develop general propositions or hypotheses that describe and explain these trends. n Comparative Politics covers a broad range of topics. The field has no one single focus. Different scholars have different preferences. 3 Comparative analysis 5

Different kinds of study n Studies of one country or of a particular institution (political parties, militaries, parliaments, interest groups), political process (decision making), or public policy (e. g. , labor, welfare or social policy) in that country. q When we focus on a single country or institution it is necessary to put the study into a larger comparative framework. We should be able to say why the subject is important and where it fits in a larger context. n Studies of two or more countries - Provides for genuine comparative studies. q Usually harder and more expensive in terms of research and travel costs. n Regional or area studies - This may include studies of Africa, Latin America, the Middle East, East Asia, Southeast Asia, South Asia, Western Europe, Central and eastern Europe, etc. q Such studies are useful because they involve groups of countries that may have several things in common - e. g. , similar history, cultures, language, religion, colonial backgrounds, an so on. Regional or area studies allow you to hold common features constant, while examining or testing for certain other features. 3 Comparative analysis 6

Different kinds of study n Studies of one country or of a particular institution (political parties, militaries, parliaments, interest groups), political process (decision making), or public policy (e. g. , labor, welfare or social policy) in that country. q When we focus on a single country or institution it is necessary to put the study into a larger comparative framework. We should be able to say why the subject is important and where it fits in a larger context. n Studies of two or more countries - Provides for genuine comparative studies. q Usually harder and more expensive in terms of research and travel costs. n Regional or area studies - This may include studies of Africa, Latin America, the Middle East, East Asia, Southeast Asia, South Asia, Western Europe, Central and eastern Europe, etc. q Such studies are useful because they involve groups of countries that may have several things in common - e. g. , similar history, cultures, language, religion, colonial backgrounds, an so on. Regional or area studies allow you to hold common features constant, while examining or testing for certain other features. 3 Comparative analysis 6

n Studies across regions q Often expensive and difficult to carry out. Such studies might involve comparisons of the role of the military in Africa and the Middle East, or the quite different paths of development of the East Asian countries and Latin America. n Global comparisons q With the improved statistical data collected by the world bank, the UN, and other agencies, it is now possible to do comparisons on a global scale. n Thematic studies q Comparative politics focuses on themes as well as countries and regions. Possible themes are economic and political dependency, corporatism, the role of the state, the process of military professionalization. Thematic studies are often complex and are usually carried out by more senior scholars. 3 Comparative analysis 7

n Studies across regions q Often expensive and difficult to carry out. Such studies might involve comparisons of the role of the military in Africa and the Middle East, or the quite different paths of development of the East Asian countries and Latin America. n Global comparisons q With the improved statistical data collected by the world bank, the UN, and other agencies, it is now possible to do comparisons on a global scale. n Thematic studies q Comparative politics focuses on themes as well as countries and regions. Possible themes are economic and political dependency, corporatism, the role of the state, the process of military professionalization. Thematic studies are often complex and are usually carried out by more senior scholars. 3 Comparative analysis 7

Why study Comparative Politics? n n n n First, it's fun and interesting, and one learns a lot about other countries, regions, and the world. Second, studying Comparative Politics will help a person overcome ethnocentrism. Third, we study Comparative Politics because that enables us to understand how nations change and the patterns that exist. A fourth reason for studying Comparative Politics is that it is intellectually stimulating. E. g. : Why do some countries modernize and others not? Why are some countries democratic and others not? Fifth, Comparative Politics has a rigorous and effective methodology. The comparative method is sophisticated tool of analysis and one that is always open to new approaches. Sixth, Comparative politics is necessary for a proper understanding of international relations, of foreign policy and of European integration. Seventh, Comparative Politics provides us with a toolbox for guidance in the interest of designing better (social) policies. Eigth, Comparative Politics enables us to compare the status quo with desired future patterns of harmonization and coordination of national (social) policies within the European Union 3 Comparative analysis 8

Why study Comparative Politics? n n n n First, it's fun and interesting, and one learns a lot about other countries, regions, and the world. Second, studying Comparative Politics will help a person overcome ethnocentrism. Third, we study Comparative Politics because that enables us to understand how nations change and the patterns that exist. A fourth reason for studying Comparative Politics is that it is intellectually stimulating. E. g. : Why do some countries modernize and others not? Why are some countries democratic and others not? Fifth, Comparative Politics has a rigorous and effective methodology. The comparative method is sophisticated tool of analysis and one that is always open to new approaches. Sixth, Comparative politics is necessary for a proper understanding of international relations, of foreign policy and of European integration. Seventh, Comparative Politics provides us with a toolbox for guidance in the interest of designing better (social) policies. Eigth, Comparative Politics enables us to compare the status quo with desired future patterns of harmonization and coordination of national (social) policies within the European Union 3 Comparative analysis 8

The pre-history of Comparative Politics n n Comparative politics has a long history dating back to the very origins of systematic political studies in ancient Greece and Rome. The earliest systematic comparisons of a more modern sort -- with almost all the ingredients of today's Comparative Politics -- were carried out by the ancient Greeks. The two foremost political scientists were Plato and Aristotle. Plato's Republic and Aristotle's Politics are the beginning of political science as we know it today and are among the great books of all time. The authors cover almost all the key issues of politics: the nature of power and leadership, the different forms of government, public policy, and so on. Aristotle collected approximately 150 constitutions of his time. He studied these constitutions extensively. He wanted to know which form of government was most stable, so he began looking at the causes of instability. Both he and Plato arrived at a system or scheme for classifying then known world's political systems. A modified form of this classification of systems is still used today. Montesquieu, the 18 th century French philosopher, is the next great comparativist. Unlike Hobbes and Locke who focused on one country, but assumed it had universal validity, Montesquieu was a true comparativist. In his book The Spirit of the Laws Montesquieu attempted to move beyond the constitutional procedures of a country to examine its true culture and "spirit. " 3 Comparative analysis 9

The pre-history of Comparative Politics n n Comparative politics has a long history dating back to the very origins of systematic political studies in ancient Greece and Rome. The earliest systematic comparisons of a more modern sort -- with almost all the ingredients of today's Comparative Politics -- were carried out by the ancient Greeks. The two foremost political scientists were Plato and Aristotle. Plato's Republic and Aristotle's Politics are the beginning of political science as we know it today and are among the great books of all time. The authors cover almost all the key issues of politics: the nature of power and leadership, the different forms of government, public policy, and so on. Aristotle collected approximately 150 constitutions of his time. He studied these constitutions extensively. He wanted to know which form of government was most stable, so he began looking at the causes of instability. Both he and Plato arrived at a system or scheme for classifying then known world's political systems. A modified form of this classification of systems is still used today. Montesquieu, the 18 th century French philosopher, is the next great comparativist. Unlike Hobbes and Locke who focused on one country, but assumed it had universal validity, Montesquieu was a true comparativist. In his book The Spirit of the Laws Montesquieu attempted to move beyond the constitutional procedures of a country to examine its true culture and "spirit. " 3 Comparative analysis 9

The modern history of Comparative Politics n “Old” institutionalism q q Modern comparative politics, initially (until about 1950), has almost exclusively been an American enterprise and concentrated on only a handful of countries in Western Europe (Britain, France, and Germany; the Soviet Union was included later. Institutionalism focused on the comparison of formal institutions such as governments, parliamentary systems and, in particular, constitutions. The importance of the US and of refugees from Europe in the 1930 s and 1940 s: WW II and the Nazi genocidal policies brought about a wave of European emigration to the U. S. - including thousands of intellectuals and social scientists (among others, top comparativists such as Friedrich, Loewenstein, Franz Neumann, and Hannah Arendt). One of the driving motives of their work has been to analyze the root causes of fascism and, accordingly, to study totalitarianism comparatively. 3 Comparative analysis 10

The modern history of Comparative Politics n “Old” institutionalism q q Modern comparative politics, initially (until about 1950), has almost exclusively been an American enterprise and concentrated on only a handful of countries in Western Europe (Britain, France, and Germany; the Soviet Union was included later. Institutionalism focused on the comparison of formal institutions such as governments, parliamentary systems and, in particular, constitutions. The importance of the US and of refugees from Europe in the 1930 s and 1940 s: WW II and the Nazi genocidal policies brought about a wave of European emigration to the U. S. - including thousands of intellectuals and social scientists (among others, top comparativists such as Friedrich, Loewenstein, Franz Neumann, and Hannah Arendt). One of the driving motives of their work has been to analyze the root causes of fascism and, accordingly, to study totalitarianism comparatively. 3 Comparative analysis 10

The modern history of Comparative Politics In the 1960 s a combination of factors - the cold war, the sudden surge of a host of newly independent nations onto the world stage, and the internationalist posture of the Kennedy administration, a global preoccupation with "development, " availability of federal grants and opportunities for travel -- helped make comparative politics an attractive field. Many of the new leading scholars in the field began to be strongly critical of the institutional approach. They now turned to the study of interest group behavior, to political parties and election cycles, and to the more informal aspects of political behavior. Behavioralism q an approach in political science which seeks to provide an objective, quantified approach to explaining and predicting political behavior. It is associated with the rise of the behavioural sciences, modelled after the natural sciences. Prior to the "Behavioralist revolution", political science being a science at all was being disputed. Critics saw the study of politics as being primarily qualitative and normative, and claimed that it lacked a scientific method necessary to be deemed a science. Behavioralists would use strict methodology and empirical research to validate their study as a social science q n 3 Comparative analysis 11

The modern history of Comparative Politics In the 1960 s a combination of factors - the cold war, the sudden surge of a host of newly independent nations onto the world stage, and the internationalist posture of the Kennedy administration, a global preoccupation with "development, " availability of federal grants and opportunities for travel -- helped make comparative politics an attractive field. Many of the new leading scholars in the field began to be strongly critical of the institutional approach. They now turned to the study of interest group behavior, to political parties and election cycles, and to the more informal aspects of political behavior. Behavioralism q an approach in political science which seeks to provide an objective, quantified approach to explaining and predicting political behavior. It is associated with the rise of the behavioural sciences, modelled after the natural sciences. Prior to the "Behavioralist revolution", political science being a science at all was being disputed. Critics saw the study of politics as being primarily qualitative and normative, and claimed that it lacked a scientific method necessary to be deemed a science. Behavioralists would use strict methodology and empirical research to validate their study as a social science q n 3 Comparative analysis 11

The modern history of Comparative Politics n Functionalism: q Societies and social systems have ‘needs’. Institutions and practices can be explained in terms of the ‘functions’ they perform for the survival of the whole. Most functionalist accounts draw analogies between the biological organism and the social system, and view societies as made up of component parts whose interrelation contributes to the maintenance of the whole. q The focus is on the problem of order and on the analysis of forces that bring cohesion, integration, and equilibrium to society. The origins of modern functionalism can be traced to Comte, Durkheim and Malinowski. q General functionalism (with its distinction between ‘latent’ and ‘manifest’ functions) and General Systems Theory (with its cybernetic analysis of positive and negative feedback loops) are more recent attempts to develop the insights of functionalism whilst rejecting both the ‘over-socialized concept characteristic of normative functionalism and the teleology implicit in early functionalist explanation. 3 Comparative analysis 12

The modern history of Comparative Politics n Functionalism: q Societies and social systems have ‘needs’. Institutions and practices can be explained in terms of the ‘functions’ they perform for the survival of the whole. Most functionalist accounts draw analogies between the biological organism and the social system, and view societies as made up of component parts whose interrelation contributes to the maintenance of the whole. q The focus is on the problem of order and on the analysis of forces that bring cohesion, integration, and equilibrium to society. The origins of modern functionalism can be traced to Comte, Durkheim and Malinowski. q General functionalism (with its distinction between ‘latent’ and ‘manifest’ functions) and General Systems Theory (with its cybernetic analysis of positive and negative feedback loops) are more recent attempts to develop the insights of functionalism whilst rejecting both the ‘over-socialized concept characteristic of normative functionalism and the teleology implicit in early functionalist explanation. 3 Comparative analysis 12

The modern history of Comparative Politics n Structural Functionalism q As a form of functionalism - developed from the work of the social anthropologist A. R. Radcliffe-Brown (1881 -1955) and systematically formulated by the American sociologist Talcott Parsons (1902 -79) (The Structure of Social Action) - structural functionalism seeks out the ‘structural’ aspects of the social system under consideration, and then studies the processes which function to maintain social structures. q Structure primarily refers to normative patterns of behaviour (regularized patterns of action in accordance with norms), whilst function explains how such patterns operate as systems. A recurrent criticism of the structural functionalist view is that functions seem to determine structures, with the consequence that it becomes impossible to derive structure from function in a coherent manner. This tendency of structural functionalist explanation has led to a resurgence of interest in the rival tradition of structuralism. 3 Comparative analysis 13

The modern history of Comparative Politics n Structural Functionalism q As a form of functionalism - developed from the work of the social anthropologist A. R. Radcliffe-Brown (1881 -1955) and systematically formulated by the American sociologist Talcott Parsons (1902 -79) (The Structure of Social Action) - structural functionalism seeks out the ‘structural’ aspects of the social system under consideration, and then studies the processes which function to maintain social structures. q Structure primarily refers to normative patterns of behaviour (regularized patterns of action in accordance with norms), whilst function explains how such patterns operate as systems. A recurrent criticism of the structural functionalist view is that functions seem to determine structures, with the consequence that it becomes impossible to derive structure from function in a coherent manner. This tendency of structural functionalist explanation has led to a resurgence of interest in the rival tradition of structuralism. 3 Comparative analysis 13

The modern history of Comparative Politics n Structuralism q The structure of a system or organization is more important than the individual behaviour of its members. Structural inquiry has deep roots in Western thought and can be traced back to the work of Plato and Aristotle. Modern structuralism began with the Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure (1857 -1913). The French social anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss introduced Saussure's epistemology to social science, arguing that analysts should develop models to reveal the underlying structural mechanisms which order the surface phenomena of social life. q Within political science and international studies, structuralism has had an important influence. This is particularly evident in critical realist philosophies of social science which often claim that Marx's theory of exploitation is an example of an underlying causal mechanism at work in society. q In International Relations theory, structuralism has been introduced by scholars such as Kenneth Waltz. Instability and war were seen to be less the result of corrupt human nature or poorly constituted states than of changing distributions of power across states in an anarchical international system. Earlier realist explanations that had dwelt on the characteristics of individual states and their leaders were dismissed as reductionist. 3 Comparative analysis 14

The modern history of Comparative Politics n Structuralism q The structure of a system or organization is more important than the individual behaviour of its members. Structural inquiry has deep roots in Western thought and can be traced back to the work of Plato and Aristotle. Modern structuralism began with the Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure (1857 -1913). The French social anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss introduced Saussure's epistemology to social science, arguing that analysts should develop models to reveal the underlying structural mechanisms which order the surface phenomena of social life. q Within political science and international studies, structuralism has had an important influence. This is particularly evident in critical realist philosophies of social science which often claim that Marx's theory of exploitation is an example of an underlying causal mechanism at work in society. q In International Relations theory, structuralism has been introduced by scholars such as Kenneth Waltz. Instability and war were seen to be less the result of corrupt human nature or poorly constituted states than of changing distributions of power across states in an anarchical international system. Earlier realist explanations that had dwelt on the characteristics of individual states and their leaders were dismissed as reductionist. 3 Comparative analysis 14

The modern history of Comparative Politics n Political development theories q Seymour Martin Lipset's Political Man (1959) showed the interrelations between social modernization and political democracy and implying that the two went hand in hand. q As countries achieved greater literacy, were more strongly mobilized, and acquired more radio and television sets, they would also tend to become more politically developed - i. e. , liberal and democratic (just like the United States). q In the 1960 s the political development approach was very attractive. It was neat, coherent, intellectually and emotionally satisfying. q The problem with this approach was that it presumed that Western institutions and policies both would and ought to be present in developing nations. When they were not, it was the local developing nations that were usually thought to be problematic, not theory of development. q Because these countries had few and weak parties, trade unions, and similar institutions, they were frequently declared "dysfunctional. " In reality, while they may be dysfunctional in terms of the particular institutional arrangements of the West, they may be quite viable in their own terms. q Thus political and moral preferences began to distort scholarly analyses. 3 Comparative analysis 15

The modern history of Comparative Politics n Political development theories q Seymour Martin Lipset's Political Man (1959) showed the interrelations between social modernization and political democracy and implying that the two went hand in hand. q As countries achieved greater literacy, were more strongly mobilized, and acquired more radio and television sets, they would also tend to become more politically developed - i. e. , liberal and democratic (just like the United States). q In the 1960 s the political development approach was very attractive. It was neat, coherent, intellectually and emotionally satisfying. q The problem with this approach was that it presumed that Western institutions and policies both would and ought to be present in developing nations. When they were not, it was the local developing nations that were usually thought to be problematic, not theory of development. q Because these countries had few and weak parties, trade unions, and similar institutions, they were frequently declared "dysfunctional. " In reality, while they may be dysfunctional in terms of the particular institutional arrangements of the West, they may be quite viable in their own terms. q Thus political and moral preferences began to distort scholarly analyses. 3 Comparative analysis 15

The modern history of Comparative Politics n In 1968, in what many have called the last great integrating book in the field, Samuel P. Huntington provided a critical evaluation of the modernization literature and offered an alternative perspective. q Huntington argued that social mobilization and modernization, rather than being supportive of and correlated with democracy and institutional development, in fact served often to undermine them in developing nations. q Huntington's critique of theories of modernization came to be generally accepted in the field, though his alternative proposal for an emphasis on orderly stable institutions such as political parties or armed forces as the key agencies of development was often criticized as a conservative formulation. 3 Comparative analysis 16

The modern history of Comparative Politics n In 1968, in what many have called the last great integrating book in the field, Samuel P. Huntington provided a critical evaluation of the modernization literature and offered an alternative perspective. q Huntington argued that social mobilization and modernization, rather than being supportive of and correlated with democracy and institutional development, in fact served often to undermine them in developing nations. q Huntington's critique of theories of modernization came to be generally accepted in the field, though his alternative proposal for an emphasis on orderly stable institutions such as political parties or armed forces as the key agencies of development was often criticized as a conservative formulation. 3 Comparative analysis 16

The modern history of Comparative Politics n Dependency theories and other approaches q By the late 1960 s and early 1970 s, criticism of the dominant developmentalist paradigm was widespread. q The developmentalist approach was criticized as being biased, ethnocentric, and less than universal. It was accused of ignoring the phenomena of class and class conflict, the play of international market and economic forces, and dependency. q As the developmentalist approach began to loose its dominant position in comparative politics, a variety of alternative approaches began to emerge. q They included: the corporatist approach; the political economy approach (emphasizing) the economic constraints on politics) and the dependency approach. 3 Comparative analysis 17

The modern history of Comparative Politics n Dependency theories and other approaches q By the late 1960 s and early 1970 s, criticism of the dominant developmentalist paradigm was widespread. q The developmentalist approach was criticized as being biased, ethnocentric, and less than universal. It was accused of ignoring the phenomena of class and class conflict, the play of international market and economic forces, and dependency. q As the developmentalist approach began to loose its dominant position in comparative politics, a variety of alternative approaches began to emerge. q They included: the corporatist approach; the political economy approach (emphasizing) the economic constraints on politics) and the dependency approach. 3 Comparative analysis 17

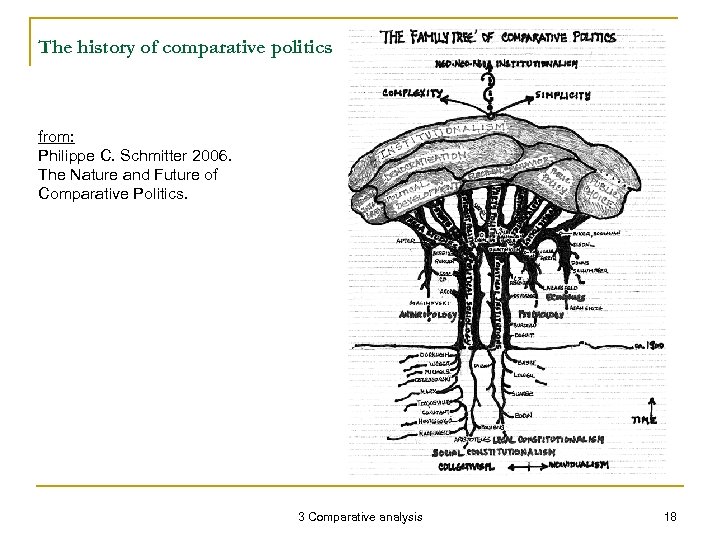

The history of comparative politics from: Philippe C. Schmitter 2006. The Nature and Future of Comparative Politics. 3 Comparative analysis 18

The history of comparative politics from: Philippe C. Schmitter 2006. The Nature and Future of Comparative Politics. 3 Comparative analysis 18

Different theoretical perspectives in comparing social policies n n n Socioeconomic moderni. Cultural values approach zation theories n Rimlinger Wilensky n King Cutwright n Caim-Caudle Jackmann n Almond The states respond to general n Verba processes of economic growth and The influence of deeply societal modernization with embedded cultural ideas and basically similar social policies patterns of behavior (e. g. , civic culture) arising from distinctive histories on Social Welfare 3 Comparative analysis 19

Different theoretical perspectives in comparing social policies n n n Socioeconomic moderni. Cultural values approach zation theories n Rimlinger Wilensky n King Cutwright n Caim-Caudle Jackmann n Almond The states respond to general n Verba processes of economic growth and The influence of deeply societal modernization with embedded cultural ideas and basically similar social policies patterns of behavior (e. g. , civic culture) arising from distinctive histories on Social Welfare 3 Comparative analysis 19

Different theoretical perspectives in comparing social policies A party government framework n Castles n Rose n Peters Capacities of political institutions (governments and political parties) to translate the preferences of citizens into social policies Political class struggle model n Gough n Offe n Stephens The Welfare State is shaped by the contest between the business forces driven by capitalist accumulation and labour and its representation 3 Comparative analysis 20

Different theoretical perspectives in comparing social policies A party government framework n Castles n Rose n Peters Capacities of political institutions (governments and political parties) to translate the preferences of citizens into social policies Political class struggle model n Gough n Offe n Stephens The Welfare State is shaped by the contest between the business forces driven by capitalist accumulation and labour and its representation 3 Comparative analysis 20

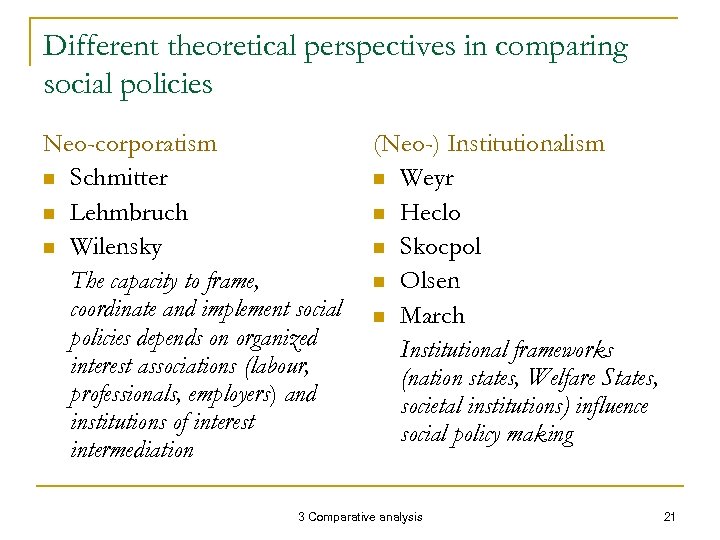

Different theoretical perspectives in comparing social policies Neo-corporatism n Schmitter n Lehmbruch n Wilensky The capacity to frame, coordinate and implement social policies depends on organized interest associations (labour, professionals, employers) and institutions of interest intermediation (Neo-) Institutionalism n Weyr n Heclo n Skocpol n Olsen n March Institutional frameworks (nation states, Welfare States, societal institutions) influence social policy making 3 Comparative analysis 21

Different theoretical perspectives in comparing social policies Neo-corporatism n Schmitter n Lehmbruch n Wilensky The capacity to frame, coordinate and implement social policies depends on organized interest associations (labour, professionals, employers) and institutions of interest intermediation (Neo-) Institutionalism n Weyr n Heclo n Skocpol n Olsen n March Institutional frameworks (nation states, Welfare States, societal institutions) influence social policy making 3 Comparative analysis 21

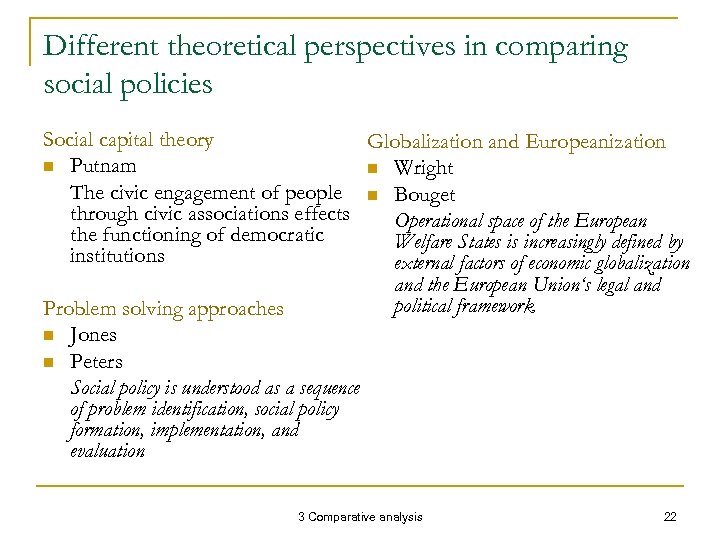

Different theoretical perspectives in comparing social policies Social capital theory Globalization and Europeanization n Putnam n Wright The civic engagement of people n Bouget through civic associations effects Operational space of the European the functioning of democratic Welfare States is increasingly defined by institutions external factors of economic globalization and the European Union‘s legal and political framework Problem solving approaches n Jones n Peters Social policy is understood as a sequence of problem identification, social policy formation, implementation, and evaluation 3 Comparative analysis 22

Different theoretical perspectives in comparing social policies Social capital theory Globalization and Europeanization n Putnam n Wright The civic engagement of people n Bouget through civic associations effects Operational space of the European the functioning of democratic Welfare States is increasingly defined by institutions external factors of economic globalization and the European Union‘s legal and political framework Problem solving approaches n Jones n Peters Social policy is understood as a sequence of problem identification, social policy formation, implementation, and evaluation 3 Comparative analysis 22

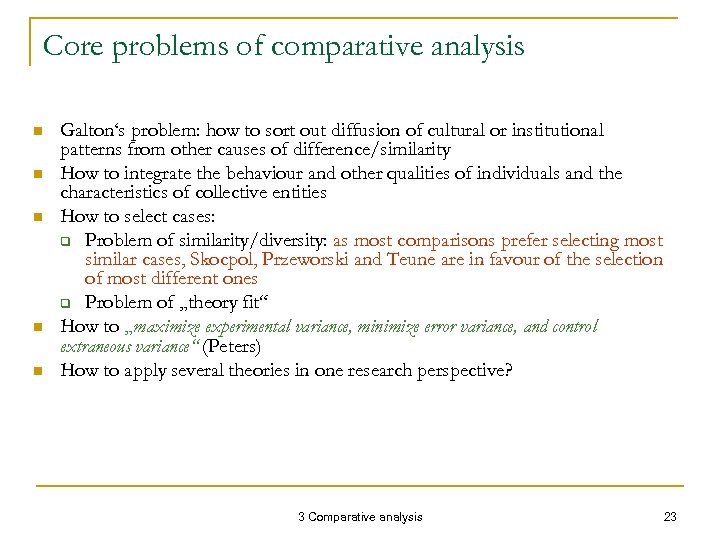

Core problems of comparative analysis n n n Galton‘s problem: how to sort out diffusion of cultural or institutional patterns from other causes of difference/similarity How to integrate the behaviour and other qualities of individuals and the characteristics of collective entities How to select cases: q Problem of similarity/diversity: as most comparisons prefer selecting most similar cases, Skocpol, Przeworski and Teune are in favour of the selection of most different ones q Problem of „theory fit“ How to „maximize experimental variance, minimize error variance, and control extraneous variance“ (Peters) How to apply several theories in one research perspective? 3 Comparative analysis 23

Core problems of comparative analysis n n n Galton‘s problem: how to sort out diffusion of cultural or institutional patterns from other causes of difference/similarity How to integrate the behaviour and other qualities of individuals and the characteristics of collective entities How to select cases: q Problem of similarity/diversity: as most comparisons prefer selecting most similar cases, Skocpol, Przeworski and Teune are in favour of the selection of most different ones q Problem of „theory fit“ How to „maximize experimental variance, minimize error variance, and control extraneous variance“ (Peters) How to apply several theories in one research perspective? 3 Comparative analysis 23

Comparing Welfare States: different research strategies n n Social expenditure approach (% of GDP) Wilenski, Mahler, Katz Data are mostly easily available. Nevertheless, this approach does not cover services in kind; it does not analyze the cost-efficiency of social schemes and programs and their real impact on clients‘ social situation Rights approach (benefits level, criteria of eligibility, the extent of selectivity/universal coverage) Korpi, Palme, Kangas Based on social rights theory; it is very demanding in terms of data availability. 3 Comparative analysis 24

Comparing Welfare States: different research strategies n n Social expenditure approach (% of GDP) Wilenski, Mahler, Katz Data are mostly easily available. Nevertheless, this approach does not cover services in kind; it does not analyze the cost-efficiency of social schemes and programs and their real impact on clients‘ social situation Rights approach (benefits level, criteria of eligibility, the extent of selectivity/universal coverage) Korpi, Palme, Kangas Based on social rights theory; it is very demanding in terms of data availability. 3 Comparative analysis 24

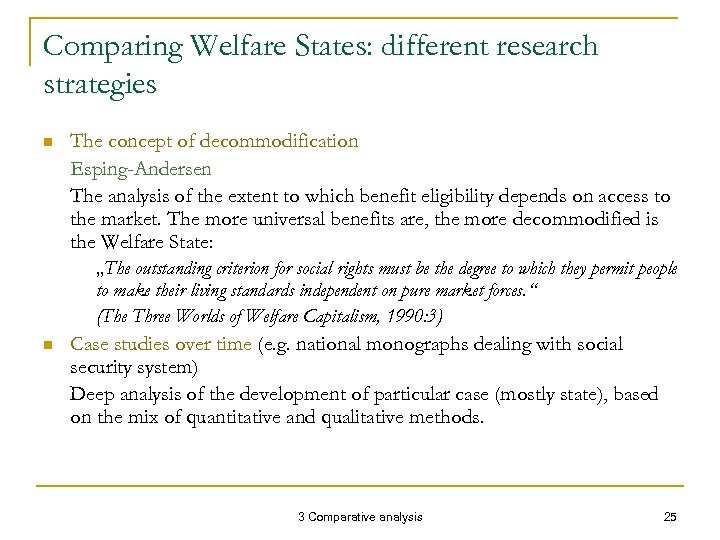

Comparing Welfare States: different research strategies n n The concept of decommodification Esping-Andersen The analysis of the extent to which benefit eligibility depends on access to the market. The more universal benefits are, the more decommodified is the Welfare State: „The outstanding criterion for social rights must be the degree to which they permit people to make their living standards independent on pure market forces. “ (The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism, 1990: 3) Case studies over time (e. g. national monographs dealing with social security system) Deep analysis of the development of particular case (mostly state), based on the mix of quantitative and qualitative methods. 3 Comparative analysis 25

Comparing Welfare States: different research strategies n n The concept of decommodification Esping-Andersen The analysis of the extent to which benefit eligibility depends on access to the market. The more universal benefits are, the more decommodified is the Welfare State: „The outstanding criterion for social rights must be the degree to which they permit people to make their living standards independent on pure market forces. “ (The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism, 1990: 3) Case studies over time (e. g. national monographs dealing with social security system) Deep analysis of the development of particular case (mostly state), based on the mix of quantitative and qualitative methods. 3 Comparative analysis 25

Comparing Welfare States: different research strategies n The mixed approach The selection of some key indicators corresponding to research questions, combined with institutional/right approach Example: set of variables to analyze the similarities and differences between social services delivery in Germany, Denmark, and the Netherlands q Regulatory structure q Financing structure q Delivery structure q Consumer power (Alber) Do you know what will be your research strategy in preparing your paper? 3 Comparative analysis 26

Comparing Welfare States: different research strategies n The mixed approach The selection of some key indicators corresponding to research questions, combined with institutional/right approach Example: set of variables to analyze the similarities and differences between social services delivery in Germany, Denmark, and the Netherlands q Regulatory structure q Financing structure q Delivery structure q Consumer power (Alber) Do you know what will be your research strategy in preparing your paper? 3 Comparative analysis 26

Methodological considerations What are the dimensions of a comparison: n Objects (nations, regions, „natural groups“, sectors of services, coverage, rights, expenditures, programmes, Welfare State regimes…) n Time periods n Combination of objects and time periods Core questions: n How to find identical entities to be compared in different countries (objects, language) n How to set up indicators able to represent analyzed social phenomena n How to cope with rapidly changing conditions n How to deal with the complexity of issues (in other words, how to simplify without unbearable distortions) 3 Comparative analysis 27

Methodological considerations What are the dimensions of a comparison: n Objects (nations, regions, „natural groups“, sectors of services, coverage, rights, expenditures, programmes, Welfare State regimes…) n Time periods n Combination of objects and time periods Core questions: n How to find identical entities to be compared in different countries (objects, language) n How to set up indicators able to represent analyzed social phenomena n How to cope with rapidly changing conditions n How to deal with the complexity of issues (in other words, how to simplify without unbearable distortions) 3 Comparative analysis 27

Possible applications and fields of inquiry n n n n n Democratization Development Studies Welfare states Poverty and exclusion Interest intermediation Labor quiescence and economic performance Women and Development Electoral Politics Ethics in Comparative Politics n n n n n Ethnic Studies Federalism Human Security Parliaments Political Leadership Migration and Refugees Nationalism Political Violence, Repression and Political Prisoners Succession and Separatist Movements 3 Comparative analysis 28

Possible applications and fields of inquiry n n n n n Democratization Development Studies Welfare states Poverty and exclusion Interest intermediation Labor quiescence and economic performance Women and Development Electoral Politics Ethics in Comparative Politics n n n n n Ethnic Studies Federalism Human Security Parliaments Political Leadership Migration and Refugees Nationalism Political Violence, Repression and Political Prisoners Succession and Separatist Movements 3 Comparative analysis 28

Comparative analysis – Example 1: “Varieties of Capitalism” (Peter A. Hall and David Soskice) 3 Comparative analysis 29

Comparative analysis – Example 1: “Varieties of Capitalism” (Peter A. Hall and David Soskice) 3 Comparative analysis 29

Comparative analysis – Example 1: Varieties of Capitalism (Peter A. Hall and David Soskice) n These two major proponents of this school of thought claim that the varieties of capitalism approach builds on prior scholarship but also goes beyond the three major established perspectives q The interventionist approach q The neo-corporatist approach q The social systems of production approach 3 Comparative analysis 30

Comparative analysis – Example 1: Varieties of Capitalism (Peter A. Hall and David Soskice) n These two major proponents of this school of thought claim that the varieties of capitalism approach builds on prior scholarship but also goes beyond the three major established perspectives q The interventionist approach q The neo-corporatist approach q The social systems of production approach 3 Comparative analysis 30

The interventionist approach (focus on the state): First developed by Sir Andrew Shonfield (Modern Capitalism, 1965); n n Focus on a set of actors with the strategic capacity to devise plans for industry and, hence, on institutional structures giving states leverage over the private sector Countries were often characterized in terms of “strong” versus “weak states” 3 Comparative analysis 31

The interventionist approach (focus on the state): First developed by Sir Andrew Shonfield (Modern Capitalism, 1965); n n Focus on a set of actors with the strategic capacity to devise plans for industry and, hence, on institutional structures giving states leverage over the private sector Countries were often characterized in terms of “strong” versus “weak states” 3 Comparative analysis 31

The neo-corporatist approach (focus on interest groups): First developed by Philippe Schmitter, Wolfgang Streeck and Gerhard Lehmbruch (1978) and subsequently refined by Goldthorpe, Alvarez, Pizzorno, Regini, Scharpf, Siaroff and many others; n Initial focus on the capacity of the trade union movement to strike bargains of national significance with employers and the state and on the capacities of all three major actors “to deliver” promised goods (. i. e. political exchange); subsequently, focus on interest systems in general and on patterns of interest intermediation between organized capital and labor; n In comparative accounts, countries have often been categorized by reference to the organization of their trade union movement (centralization, density, labor quiescence, etc. ) 3 Comparative analysis 32

The neo-corporatist approach (focus on interest groups): First developed by Philippe Schmitter, Wolfgang Streeck and Gerhard Lehmbruch (1978) and subsequently refined by Goldthorpe, Alvarez, Pizzorno, Regini, Scharpf, Siaroff and many others; n Initial focus on the capacity of the trade union movement to strike bargains of national significance with employers and the state and on the capacities of all three major actors “to deliver” promised goods (. i. e. political exchange); subsequently, focus on interest systems in general and on patterns of interest intermediation between organized capital and labor; n In comparative accounts, countries have often been categorized by reference to the organization of their trade union movement (centralization, density, labor quiescence, etc. ) 3 Comparative analysis 32

The social systems of production approach (focus on firms): Partly based on the French regulation school (Liepietz, Boyer, et. al. ): n Focus on sectoral governance arrangements, on national innovation systems, on flexible production regimes, on regional economies, and on diversified quality production, etc. n Emphasis on the way in which the institutional structures of a nation, region or sector (post-Fordist types of production) provide support for innovation or production regimes different from those traditionally associated with mass production (Fordism) n Categorizing nations by looking at regional or sectoral particularisms whose models of success lie in dynamic regions (3 rd Italy, i. e. Emilia-Romagna, Tuscany; Baden/Württemberg, etc. ) 3 Comparative analysis 33

The social systems of production approach (focus on firms): Partly based on the French regulation school (Liepietz, Boyer, et. al. ): n Focus on sectoral governance arrangements, on national innovation systems, on flexible production regimes, on regional economies, and on diversified quality production, etc. n Emphasis on the way in which the institutional structures of a nation, region or sector (post-Fordist types of production) provide support for innovation or production regimes different from those traditionally associated with mass production (Fordism) n Categorizing nations by looking at regional or sectoral particularisms whose models of success lie in dynamic regions (3 rd Italy, i. e. Emilia-Romagna, Tuscany; Baden/Württemberg, etc. ) 3 Comparative analysis 33

In the view of Hall and Soskice: n The interventionist approach … overstates the capacity of what governments can accomplish; n The neo-corporatist approach … underplays the role of firms and employer associations in the coordination of the economy; n The social systems of production approach … gives too much significance to regional and sectoral institutions and neglects the role of national institutional structures and regulatory regimes 3 Comparative analysis 34

In the view of Hall and Soskice: n The interventionist approach … overstates the capacity of what governments can accomplish; n The neo-corporatist approach … underplays the role of firms and employer associations in the coordination of the economy; n The social systems of production approach … gives too much significance to regional and sectoral institutions and neglects the role of national institutional structures and regulatory regimes 3 Comparative analysis 34

Hall and Soskice, on the contrary, suggest a focus on: n n n Institutions as socializing agencies that represent a particular set of norms or attitudes in those who operate within them; The effects of an institution as following from the power it confers on those within it via a “hierarchically allocating formal sanctions and authority or mobilizing capacity”; Institutions of the political economy as a matrix of sanctions and incentives. Going beyond the above three factors they also stress the role of n Strategic interactions central to the behavior of economic actors. The advantage of their varieties of capitalism approach is that it: “[…] integrates analytical perspectives central to microeconomics into the com political economies. Bringing the firm into the center of analysis, they build bridges between business studies, economics, and political science that are of interest to scholars in all of these disciplines. ” 3 Comparative analysis 35

Hall and Soskice, on the contrary, suggest a focus on: n n n Institutions as socializing agencies that represent a particular set of norms or attitudes in those who operate within them; The effects of an institution as following from the power it confers on those within it via a “hierarchically allocating formal sanctions and authority or mobilizing capacity”; Institutions of the political economy as a matrix of sanctions and incentives. Going beyond the above three factors they also stress the role of n Strategic interactions central to the behavior of economic actors. The advantage of their varieties of capitalism approach is that it: “[…] integrates analytical perspectives central to microeconomics into the com political economies. Bringing the firm into the center of analysis, they build bridges between business studies, economics, and political science that are of interest to scholars in all of these disciplines. ” 3 Comparative analysis 35

The basic six elements of their approach: 1. A relational view of the firm with a focus on coordination problems • • • [i. e. the quality of relationships the firm is able to establish both internally with its own employees and externally with suppliers, clients, collaborators, stakeholders, trade unions, business associations and governments]. industrial relations (coordination of bargaining over wages and working conditions) vocational training and education (problem of securing a workforce with suitable skills – how much to invest into skills – firm-specific or industry-wide training? ) corporate governance (types of access to finance, etc. ) inter-firm relations (to secure proper supplies of inputs and access to technology) coordination problems with employees (workers develop reservoirs of specialized information that they can share with or withhold from management) 3 Comparative analysis 36

The basic six elements of their approach: 1. A relational view of the firm with a focus on coordination problems • • • [i. e. the quality of relationships the firm is able to establish both internally with its own employees and externally with suppliers, clients, collaborators, stakeholders, trade unions, business associations and governments]. industrial relations (coordination of bargaining over wages and working conditions) vocational training and education (problem of securing a workforce with suitable skills – how much to invest into skills – firm-specific or industry-wide training? ) corporate governance (types of access to finance, etc. ) inter-firm relations (to secure proper supplies of inputs and access to technology) coordination problems with employees (workers develop reservoirs of specialized information that they can share with or withhold from management) 3 Comparative analysis 36

2. Liberal Market Economies (LME) and Coordinated Market Economies (CME) [i. e. national economies can be compared by reference to the way in which firms resolve the coordination problems they face in these spheres]. q LMEs: n predominance of market relationships (price signals as major mechanism of coordination) q CMEs: n (firms depending more heavily on non-market relationships to coordinate their endeavors with other actors and to construct their core competencies; i. e. networks of contracting and monitoring based on the exchange of information, more reliance on collaboration as opposed to purely competitive relationships, higher relevance of strategic interaction) 3 Comparative analysis 37

2. Liberal Market Economies (LME) and Coordinated Market Economies (CME) [i. e. national economies can be compared by reference to the way in which firms resolve the coordination problems they face in these spheres]. q LMEs: n predominance of market relationships (price signals as major mechanism of coordination) q CMEs: n (firms depending more heavily on non-market relationships to coordinate their endeavors with other actors and to construct their core competencies; i. e. networks of contracting and monitoring based on the exchange of information, more reliance on collaboration as opposed to purely competitive relationships, higher relevance of strategic interaction) 3 Comparative analysis 37

3. The role of institutions and organizations [i. e. institutions as a set of rules, formal or informal, that actors generally follow, whether for normative, cognitive or material reasons, and organizations as durable entities with formally-recognized members, whose rules also contribute to the institutions of the political economy] q Markets as the dominant institution of LMEs and Hierarchies as the major devices to correct for market failure q Embedded markets, i. e. “markets and networks” (i. e. powerful business or employer associations, strong trade unions, extensive networks of cross-shareholding, legal and regulatory systems for collaborative endeavors) as the major institutions in CMEs 3 Comparative analysis 38

3. The role of institutions and organizations [i. e. institutions as a set of rules, formal or informal, that actors generally follow, whether for normative, cognitive or material reasons, and organizations as durable entities with formally-recognized members, whose rules also contribute to the institutions of the political economy] q Markets as the dominant institution of LMEs and Hierarchies as the major devices to correct for market failure q Embedded markets, i. e. “markets and networks” (i. e. powerful business or employer associations, strong trade unions, extensive networks of cross-shareholding, legal and regulatory systems for collaborative endeavors) as the major institutions in CMEs 3 Comparative analysis 38

4. The role of culture and deliberation [i. e. formal institutions are important but they are rarely sufficient to ensure the functioning of a political economy]. Hence, the importance of including into the analysis: q Informal rules and understandings that manage to achieve equilibrium in the strategic interactions especially among firms in CMEs. This also includes history and culture since many actors have learned to follow a set of informal rules only by virtue of experience and of exposure to a common culture. q Devices for and the capacity for deliberation, i. e. institutions that encourage the relevant actors to engage in collective discussion and to reach agreement with each other. Such institutions can enhance the capacity of firms or other actors to act strategically when faced with new or unfamiliar challenges 3 Comparative analysis 39

4. The role of culture and deliberation [i. e. formal institutions are important but they are rarely sufficient to ensure the functioning of a political economy]. Hence, the importance of including into the analysis: q Informal rules and understandings that manage to achieve equilibrium in the strategic interactions especially among firms in CMEs. This also includes history and culture since many actors have learned to follow a set of informal rules only by virtue of experience and of exposure to a common culture. q Devices for and the capacity for deliberation, i. e. institutions that encourage the relevant actors to engage in collective discussion and to reach agreement with each other. Such institutions can enhance the capacity of firms or other actors to act strategically when faced with new or unfamiliar challenges 3 Comparative analysis 39

5. Institutional infrastructure and corporate strategy [i. e. the application of insights gained from micro-economics to problems of understanding the economy as a whole - not in terms of structure follows strategy (i. e. firms as creating the institutional structures most beneficial to them) but, rather, also in terms of strategy follows structure (many institutions cannot be easily changed by individual firms or groups of firms but have to be understood as givens)]. While the existing literature has taken account of this by focusing on specific sectoral and regional arrangements (Hollingsworth, Herrigel, Piore and Sabel, etc. ), q Hall and Soskice claim that many of these sectoral and regional devices for coordination are actually product of nationally-specific processes of development. There are important differences in corporate strategy at the national level because so much of the institutional framework on which firms rely remains nation—specific and is beyond the reach of individual actors. 3 Comparative analysis 40

5. Institutional infrastructure and corporate strategy [i. e. the application of insights gained from micro-economics to problems of understanding the economy as a whole - not in terms of structure follows strategy (i. e. firms as creating the institutional structures most beneficial to them) but, rather, also in terms of strategy follows structure (many institutions cannot be easily changed by individual firms or groups of firms but have to be understood as givens)]. While the existing literature has taken account of this by focusing on specific sectoral and regional arrangements (Hollingsworth, Herrigel, Piore and Sabel, etc. ), q Hall and Soskice claim that many of these sectoral and regional devices for coordination are actually product of nationally-specific processes of development. There are important differences in corporate strategy at the national level because so much of the institutional framework on which firms rely remains nation—specific and is beyond the reach of individual actors. 3 Comparative analysis 40

6. Institutional complementarities [i. e. drawing from the notion of “complementary goods” (an increase in the price of one depresses the demand for the other; bread and butter example), the authors develop a notion of “complementary institutions”]. q q q This has particular relevance for the study of comparative capitalism because it suggests “that institutional practices of various types should not be distributed randomly across nations. ” Instead, nations that have developed particular forms of coordination in one sphere should tend to develop complementary practices in others because the institutions that support coordination in one sphere can be used to support analogues forms of coordination in others (for instance, monitoring networks by business associations to support collaborative vocational training can also be employed to support cooperative standard setting). If this is correct, we should expect clustering along the dimensions that divide LMEs from CMEs in that nations should tend to group together as they converge on complementary practices across the multiple spheres of the economy 3 Comparative analysis 41

6. Institutional complementarities [i. e. drawing from the notion of “complementary goods” (an increase in the price of one depresses the demand for the other; bread and butter example), the authors develop a notion of “complementary institutions”]. q q q This has particular relevance for the study of comparative capitalism because it suggests “that institutional practices of various types should not be distributed randomly across nations. ” Instead, nations that have developed particular forms of coordination in one sphere should tend to develop complementary practices in others because the institutions that support coordination in one sphere can be used to support analogues forms of coordination in others (for instance, monitoring networks by business associations to support collaborative vocational training can also be employed to support cooperative standard setting). If this is correct, we should expect clustering along the dimensions that divide LMEs from CMEs in that nations should tend to group together as they converge on complementary practices across the multiple spheres of the economy 3 Comparative analysis 41

Once applied empirically, the above factors generate: Out of the large (22) OECD countries [total=30]: n Liberal Market Economies (LMEs): 6 countries q n Coordinated Market Economies (CMEs): 10 countries q n US, Britain, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, Ireland Germany, Japan, Switzerland, the Netherlands, Belgium, Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Finland Austria Intermediate and ambiguous position: 6 countries q France, Italy, Spain, Portugal, Greece, and Turkey 3 Comparative analysis 42

Once applied empirically, the above factors generate: Out of the large (22) OECD countries [total=30]: n Liberal Market Economies (LMEs): 6 countries q n Coordinated Market Economies (CMEs): 10 countries q n US, Britain, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, Ireland Germany, Japan, Switzerland, the Netherlands, Belgium, Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Finland Austria Intermediate and ambiguous position: 6 countries q France, Italy, Spain, Portugal, Greece, and Turkey 3 Comparative analysis 42

The authors claim: q that both LMEs and CMEs fare best in terms of meeting the challenges of internationalization and Europeanization q while the intermediate cases and hybrid mixtures have considerable more problems. q this raises the question, of course, where exactly CEE countries are likely to be located (problem: liberalism in economic dimension and certain amount of coordination in social dimension) and how their political economies are likely to perform 3 Comparative analysis 43

The authors claim: q that both LMEs and CMEs fare best in terms of meeting the challenges of internationalization and Europeanization q while the intermediate cases and hybrid mixtures have considerable more problems. q this raises the question, of course, where exactly CEE countries are likely to be located (problem: liberalism in economic dimension and certain amount of coordination in social dimension) and how their political economies are likely to perform 3 Comparative analysis 43

Comparative institutional advantage n n Starting from theory of comparative economic advantage (Adam Smith), the authors develop a notion of comparative institutional advantage. Availability of different modes of coordination conditions the efficiency with which firms can perform certain activities, thereby affecting the efficiency with which they can produce certain kinds of goods and services. In short, the national institutional frameworks provide nations with comparative advantages in particular activities and products. Among other things, they find out that there are pronounced differences between LMEs and CMEs in terms of modes of innovation. For instance. LMEs (example: US) tend to be good in radical innovation in fast moving technology sectors (medical engineering, biotechnology, semiconductors, telecommunications) while CMEs (example: Germany) tend to be better in incremental innovation in the production of capital goods (mechanical engineering, product handling, transport, consumer durables, machine tools) All this has to do with the relations studied among firms, within firms, and of firms with other actors. 3 Comparative analysis 44

Comparative institutional advantage n n Starting from theory of comparative economic advantage (Adam Smith), the authors develop a notion of comparative institutional advantage. Availability of different modes of coordination conditions the efficiency with which firms can perform certain activities, thereby affecting the efficiency with which they can produce certain kinds of goods and services. In short, the national institutional frameworks provide nations with comparative advantages in particular activities and products. Among other things, they find out that there are pronounced differences between LMEs and CMEs in terms of modes of innovation. For instance. LMEs (example: US) tend to be good in radical innovation in fast moving technology sectors (medical engineering, biotechnology, semiconductors, telecommunications) while CMEs (example: Germany) tend to be better in incremental innovation in the production of capital goods (mechanical engineering, product handling, transport, consumer durables, machine tools) All this has to do with the relations studied among firms, within firms, and of firms with other actors. 3 Comparative analysis 44

Implications for policy-making: Economic policies • In earlier research, the major question has been how to induce economic actors to cooperate with the government; • In Hall and Soskice’s view, the problem today is of how to induce firms to coordinate more effectively with each other (by using marketincentive policies or coordination-oriented policies) Social policies • Convention assumes that the development of social policies is contingent on organized labor and progressive political parties, while business generally opposes such initiatives; • Hall and Soskice claim that a relational approach to company competencies emphasizes the support social policy provides for the relationship that firms develop to advance their objectives and that business can indeed be interested in having a dense social policy network 3 Comparative analysis 45

Implications for policy-making: Economic policies • In earlier research, the major question has been how to induce economic actors to cooperate with the government; • In Hall and Soskice’s view, the problem today is of how to induce firms to coordinate more effectively with each other (by using marketincentive policies or coordination-oriented policies) Social policies • Convention assumes that the development of social policies is contingent on organized labor and progressive political parties, while business generally opposes such initiatives; • Hall and Soskice claim that a relational approach to company competencies emphasizes the support social policy provides for the relationship that firms develop to advance their objectives and that business can indeed be interested in having a dense social policy network 3 Comparative analysis 45

Comparative analysis – Example 2: “Worlds, Families, Regimes: Country Clusters in European and OECD Public Policy” (Francis G. Castles and Herbert Obinger, 2008) 3 Comparative analysis 46

Comparative analysis – Example 2: “Worlds, Families, Regimes: Country Clusters in European and OECD Public Policy” (Francis G. Castles and Herbert Obinger, 2008) 3 Comparative analysis 46

Comparative analysis – Example 2: Worlds, Families, Regimes: Country Clusters in European and OECD Public Policy (F. G. Castles and H. Obinger, 2008) n The comparative welfare states literature has developed quite independently from the varieties of capitalism literature. n Although there are many similar questions and overlaps, the two bodies of literature tend to mutually ignore each other. n This may be due, in particular, to the different foci chosen for analysis – firms and non -economic institutions for the coordination of economic activity on the one hand policies or policy regimes (especially social policies) on the other hand. n However, there is a quite recent innovative approach in the welfare states literature that tries to combine some of the major variables used by both strands of literature (Castles/Obinger) 3 Comparative analysis 47

Comparative analysis – Example 2: Worlds, Families, Regimes: Country Clusters in European and OECD Public Policy (F. G. Castles and H. Obinger, 2008) n The comparative welfare states literature has developed quite independently from the varieties of capitalism literature. n Although there are many similar questions and overlaps, the two bodies of literature tend to mutually ignore each other. n This may be due, in particular, to the different foci chosen for analysis – firms and non -economic institutions for the coordination of economic activity on the one hand policies or policy regimes (especially social policies) on the other hand. n However, there is a quite recent innovative approach in the welfare states literature that tries to combine some of the major variables used by both strands of literature (Castles/Obinger) 3 Comparative analysis 47

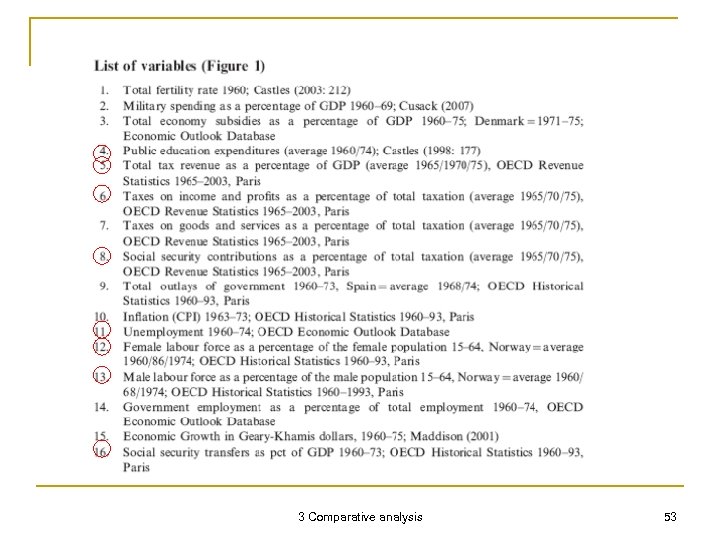

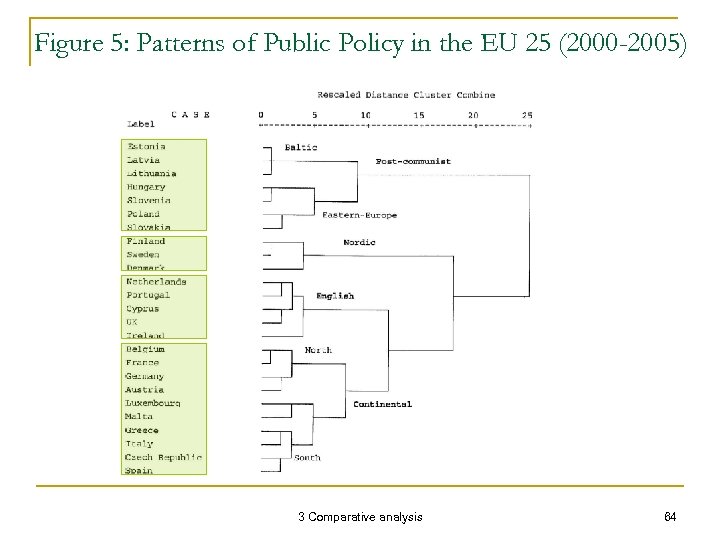

The recent (2008) analysis by Castles & Obinger is of particular interest because: n n n n It presents a dynamic/ diachronic account over time (1960 -2004) based on different waves of inquiry; It combines structural variables (party system, interest intermediation, etc. ) with variables of policy outcomes; It includes many indices that are important from a perspective of social policies It includes Central and Eastern European countries (2000 -2005) into the comparative study of families of nations (something that has hardly ever been done before in this type of macro-level analysis). Main questions: Whether distinct worlds persist in an era of policy convergence and globalization, Whether policy antecedents and structural variables cluster in the same ways as policy outcomes and Whether the enlargement of the EU has led to an increase in the number of worlds constituting the wider European polity 3 Comparative analysis 48

The recent (2008) analysis by Castles & Obinger is of particular interest because: n n n n It presents a dynamic/ diachronic account over time (1960 -2004) based on different waves of inquiry; It combines structural variables (party system, interest intermediation, etc. ) with variables of policy outcomes; It includes many indices that are important from a perspective of social policies It includes Central and Eastern European countries (2000 -2005) into the comparative study of families of nations (something that has hardly ever been done before in this type of macro-level analysis). Main questions: Whether distinct worlds persist in an era of policy convergence and globalization, Whether policy antecedents and structural variables cluster in the same ways as policy outcomes and Whether the enlargement of the EU has led to an increase in the number of worlds constituting the wider European polity 3 Comparative analysis 48

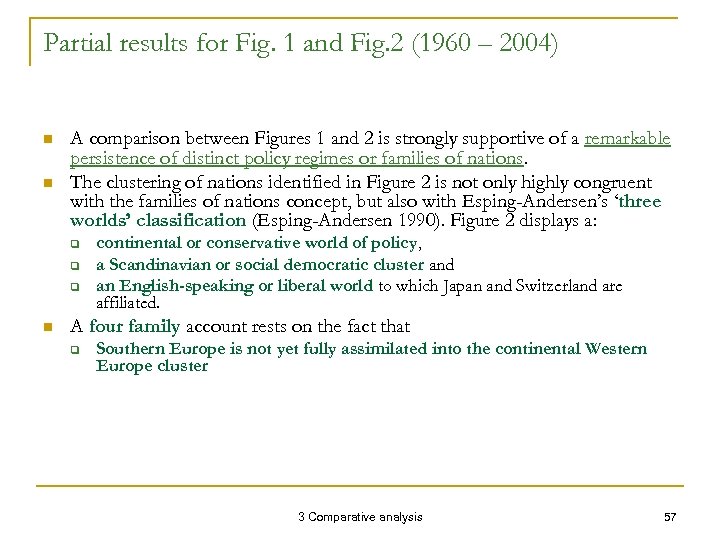

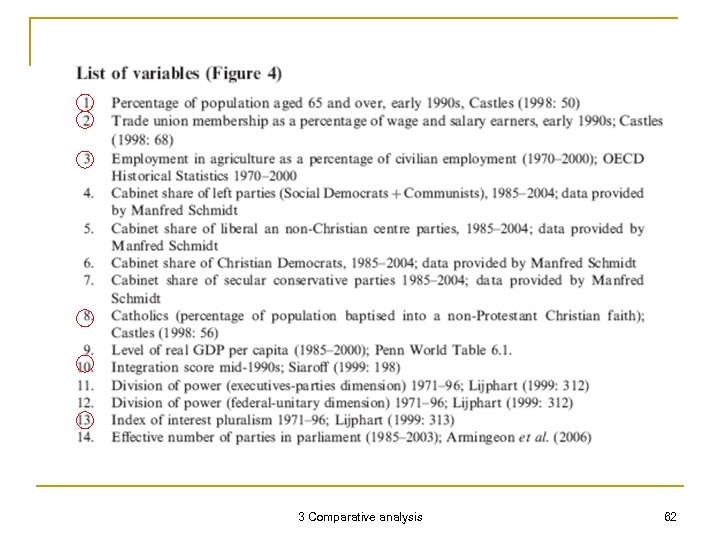

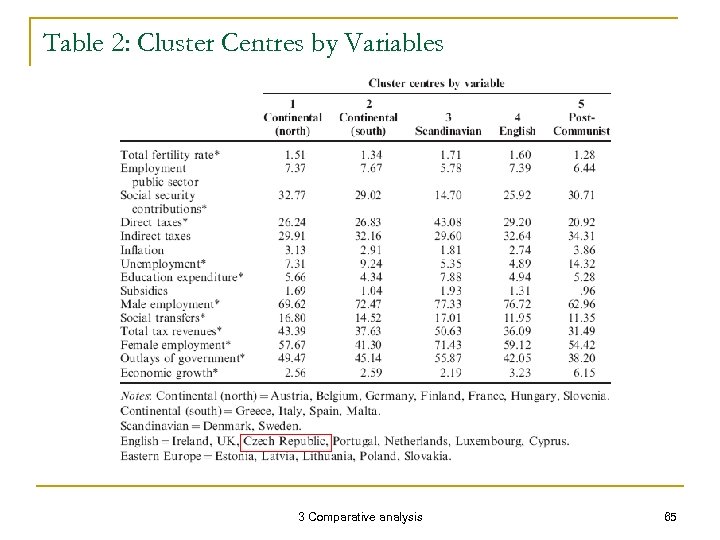

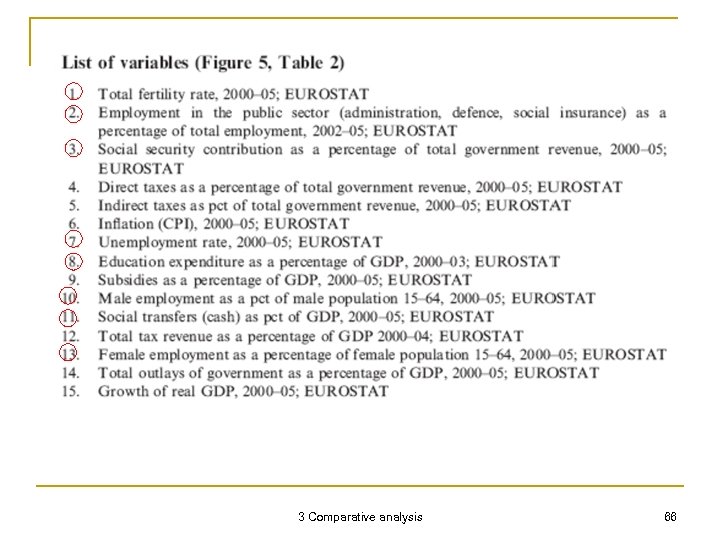

n Main Variables: For antecedent periods (1945 -1960): q n n n Social and cultural characteristics (demographics, ethno-linguistic fractionalization and religious adherence; levels of economic development (GDP per capita, agricultural employment); the distribution of power resources (partisan complexion of government, party system fractionalization, union density); the system of interest mediation; and the institutionally mediated horizontal and vertical division of power. For more recent periods (1960 -75) and present status quo (2000 -2004): q Size of government; distinct spending priorities of governments (e. g. spending on education, industrial subsidies, welfare and defense), the mode of public expenditure financing; economic and labor market performance; and gender-related outcomes Main Method: Study of the presence and persistence of distinct worlds of public policy by comparisons of 20 advanced OECD democracies over two separate time periods Use of the techniques of hierarchical cluster analysis 3 Comparative analysis 49

n Main Variables: For antecedent periods (1945 -1960): q n n n Social and cultural characteristics (demographics, ethno-linguistic fractionalization and religious adherence; levels of economic development (GDP per capita, agricultural employment); the distribution of power resources (partisan complexion of government, party system fractionalization, union density); the system of interest mediation; and the institutionally mediated horizontal and vertical division of power. For more recent periods (1960 -75) and present status quo (2000 -2004): q Size of government; distinct spending priorities of governments (e. g. spending on education, industrial subsidies, welfare and defense), the mode of public expenditure financing; economic and labor market performance; and gender-related outcomes Main Method: Study of the presence and persistence of distinct worlds of public policy by comparisons of 20 advanced OECD democracies over two separate time periods Use of the techniques of hierarchical cluster analysis 3 Comparative analysis 49

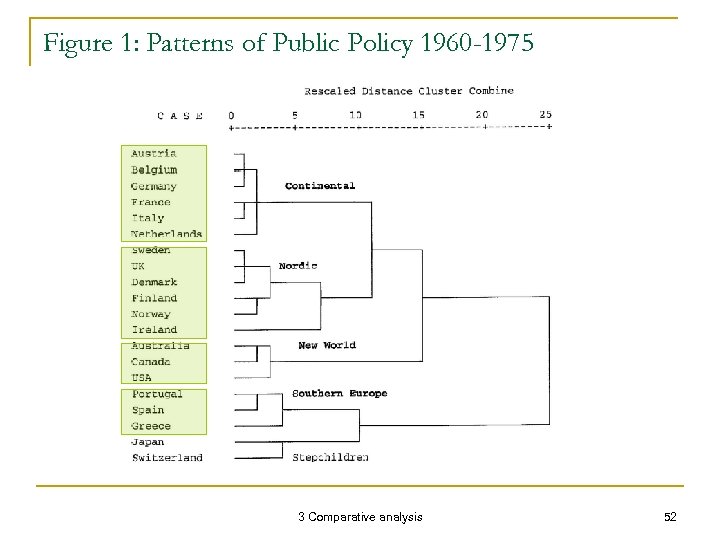

n n Hierarchical Cluster Analysis: A simple technique which seeks to discern clusters showing great internal homogeneity (here called “worlds”, “families” and “regimes”. The goal of HCA is to identify a set of clusters such that units of observations within a cluster are more similar to each other than they are to cases in other clusters. The advantage of HCA is that it does not predetermine the number of clusters. In consequence, the clustering obtained by this method is exclusively datadetermined. In the following figures, the more one moves to the right on the x-axis, the more dissimilar are the clusters. Hence, long cluster lines indicate marked dissimilarities between the clusters. 3 Comparative analysis 50

n n Hierarchical Cluster Analysis: A simple technique which seeks to discern clusters showing great internal homogeneity (here called “worlds”, “families” and “regimes”. The goal of HCA is to identify a set of clusters such that units of observations within a cluster are more similar to each other than they are to cases in other clusters. The advantage of HCA is that it does not predetermine the number of clusters. In consequence, the clustering obtained by this method is exclusively datadetermined. In the following figures, the more one moves to the right on the x-axis, the more dissimilar are the clusters. Hence, long cluster lines indicate marked dissimilarities between the clusters. 3 Comparative analysis 50

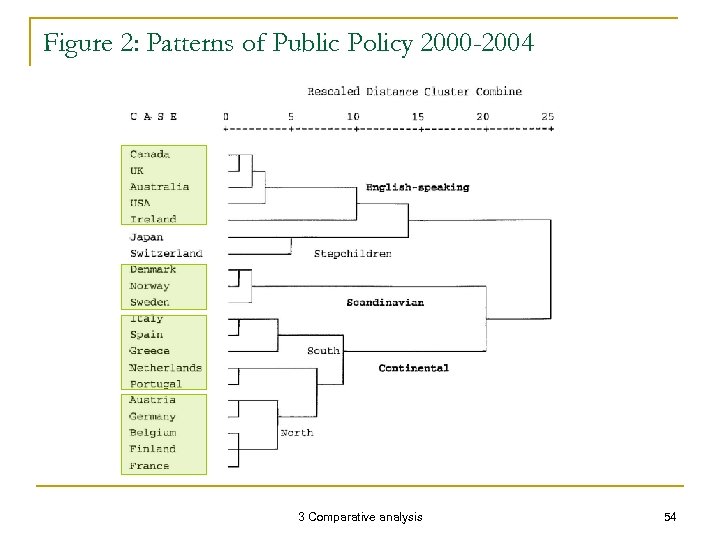

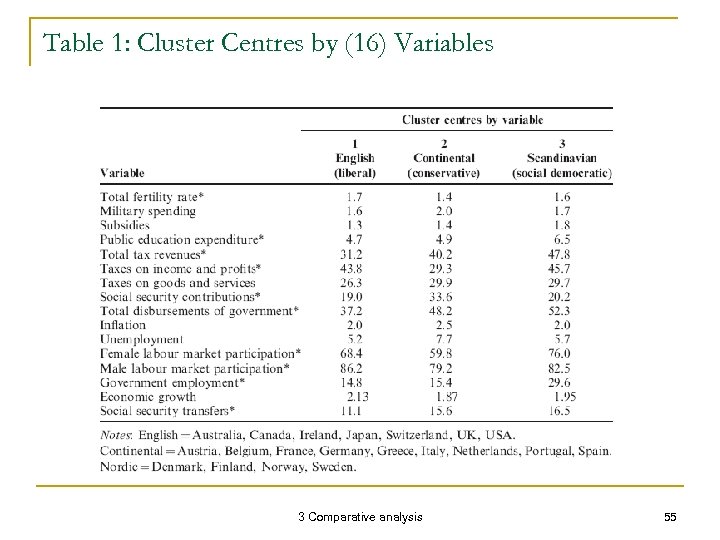

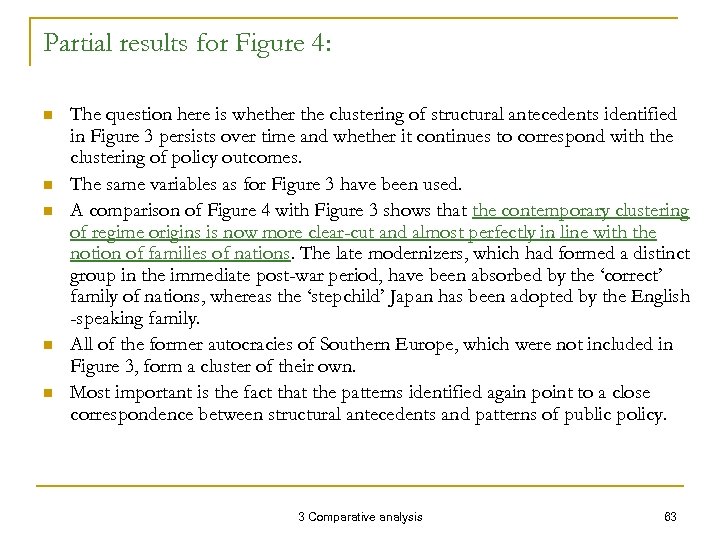

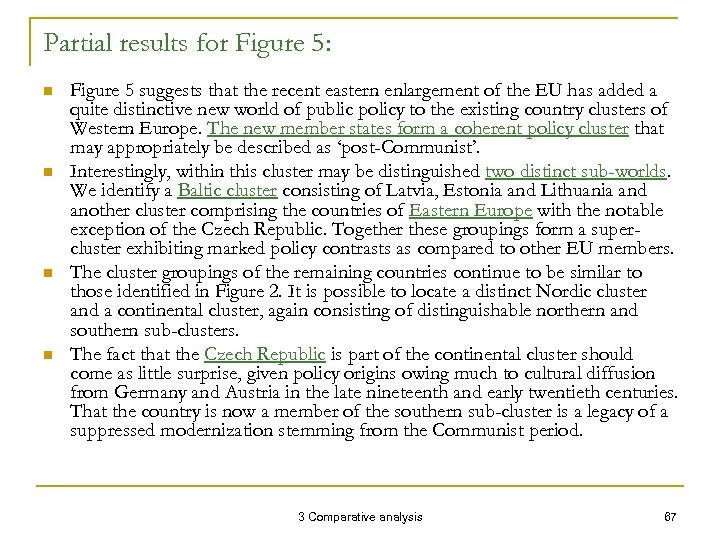

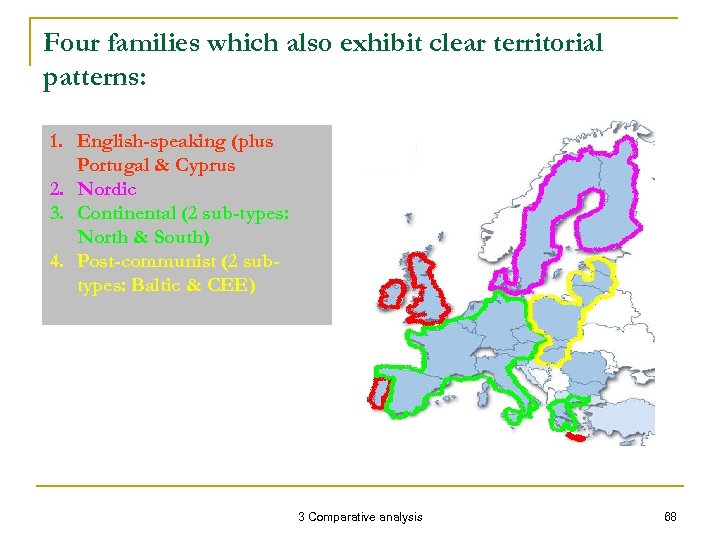

n n Main results: During the time span of approximately 25 years between the two periods of observation, the international political economy and the political landscape of Europe have undergone fundamental transformations. The period has witnessed the collapse of communism, a deepening European integration, a marked societal modernisation and an ever increasing economic globalisation. Contrary to visions of increasing convergence and of an „unfreezing“ (Stein Rokkan) of distinct worlds of public policy (resulting from economic internationalization and from political integration), country clustering is today more pronounced than it has been in the past; The clustering of policy outputs is, in large part, structurally determined; The EU now contains a quite distinct post-Communist family of nations; 3 Comparative analysis 51

n n Main results: During the time span of approximately 25 years between the two periods of observation, the international political economy and the political landscape of Europe have undergone fundamental transformations. The period has witnessed the collapse of communism, a deepening European integration, a marked societal modernisation and an ever increasing economic globalisation. Contrary to visions of increasing convergence and of an „unfreezing“ (Stein Rokkan) of distinct worlds of public policy (resulting from economic internationalization and from political integration), country clustering is today more pronounced than it has been in the past; The clustering of policy outputs is, in large part, structurally determined; The EU now contains a quite distinct post-Communist family of nations; 3 Comparative analysis 51

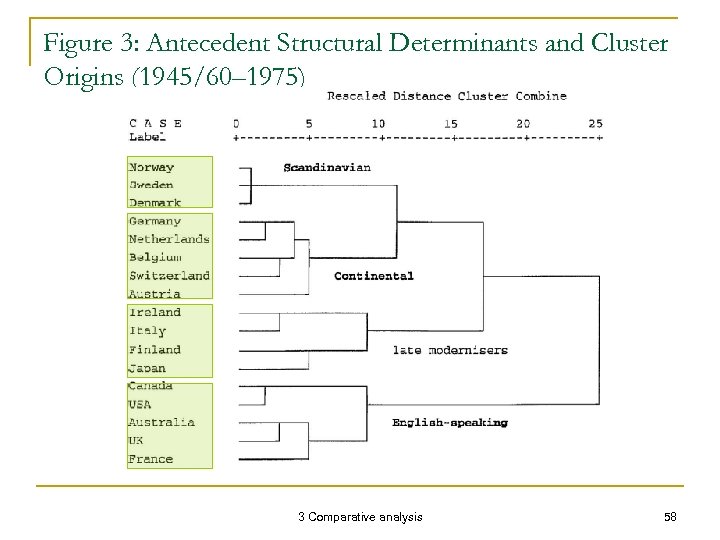

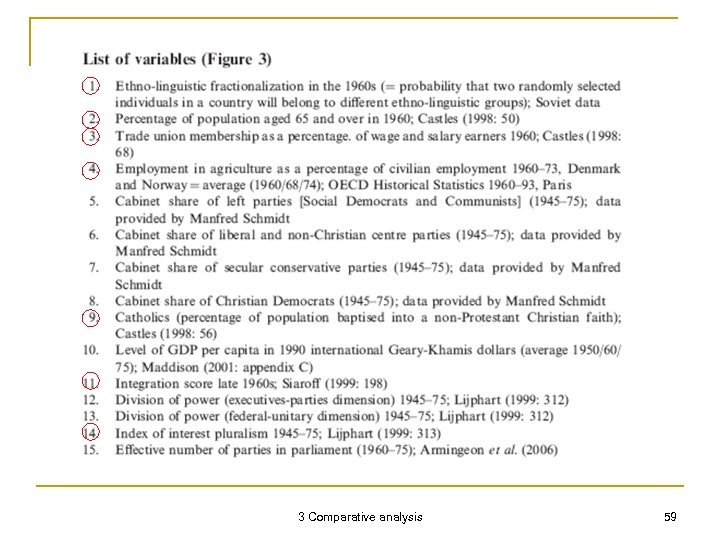

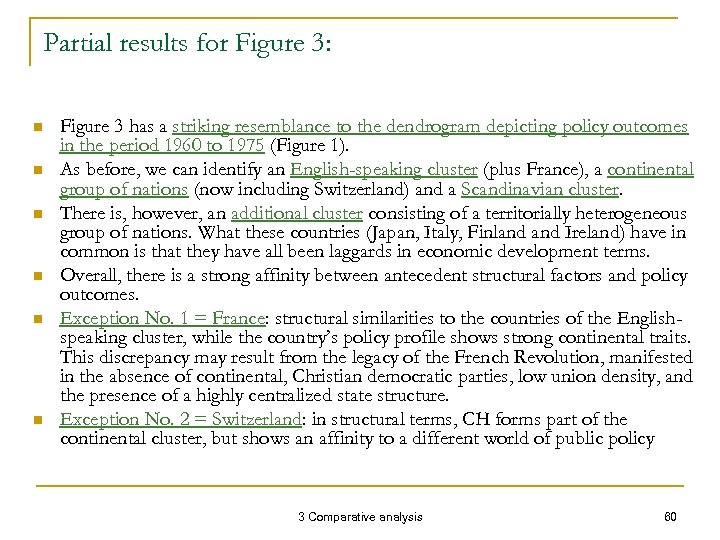

Figure 1: Patterns of Public Policy 1960 -1975 3 Comparative analysis 52

Figure 1: Patterns of Public Policy 1960 -1975 3 Comparative analysis 52

3 Comparative analysis 53

3 Comparative analysis 53

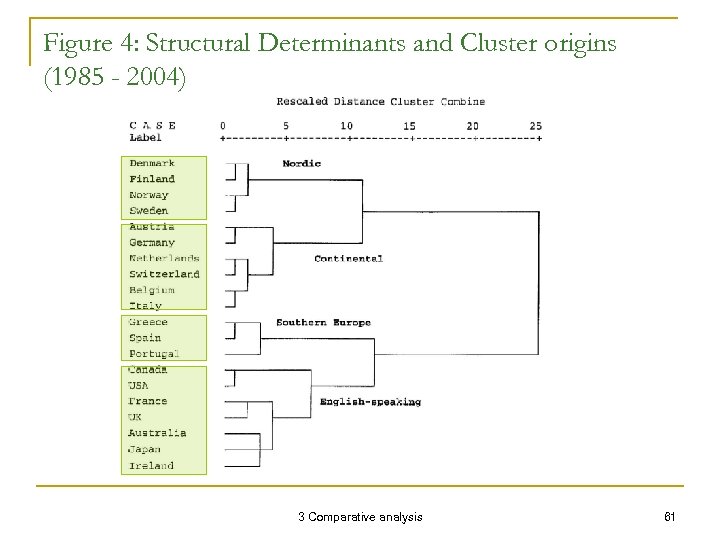

Figure 2: Patterns of Public Policy 2000 -2004 3 Comparative analysis 54

Figure 2: Patterns of Public Policy 2000 -2004 3 Comparative analysis 54

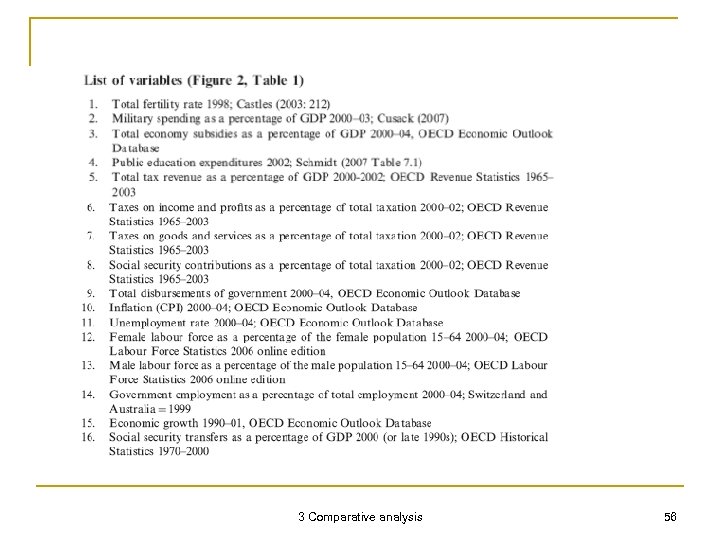

Table 1: Cluster Centres by (16) Variables 3 Comparative analysis 55

Table 1: Cluster Centres by (16) Variables 3 Comparative analysis 55

3 Comparative analysis 56

3 Comparative analysis 56