f257353320a095abf7ba1dae54c53dda.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 104

Class in the Baltic States: A Comparative Neo. Weberian Analysis Vaidas Morkevičius Policy and Public Administration Institute, Kaunas University of Technology Zenonas NORKUS Sociology Department, Faculty of Philosophy, Vilnius University The Presentation (ESA-882) at the ESA 11 th Conference, 28 - 31 August 2013 Torino, Italy RN 36 Sociology of Transformations: East and West, Session a 02 RN 36 - Varieties of Capitalism in New EU Countries , 29/8 16: 00 - 17: 30 - CLE, B 1 The research of Vaidas Morkevičius funded by the Research Council of Lithuania under Researcher teams’ project (contract No. MIP-022/2012) The research of Zenonas Norkus funded by the European Social Fund under the Global Grant measure (VP-1 3. 1 -ŠMM-07 -K-01 -010)

Why Class? Just look at the subject of our session: „Varieties of Capitalism in New EU“ No capitalism without classes! If you speak about capitalism but keep silent about classes, then there is no point in speaking about capitalism too. Speaking about capitalism commits to the socioeconomic analysis of social structure, where the distribution of the members of society among different occupations is considered as more important than their differences in sexual preferences or value-orientations If ones seriously applies the concept of capitalism to social change in the former communist countries, the analysis is incomplete without the picture of the emerging class structures There alternative – non-socio-economic ways - to analyze social structure, e. g. in terms of cultural milieus, life-styles (e. g. high-brows, low-brows; materialists, post-materialists; etc. ) – but they just belong into different session. Generally, diffferences and similarities between people in what they do during their working time (5 days each week) and how they earn their living still matter more than differences and similarities in what they do during weekends (2 days each week) or vacation (many work too : ) ). Maybe on weekends (? ? ) or during carnivals (!!!!!!!) there are no classes, but surely they are here on workdays. Are there no class differences what people can do on vacations, educate children etc. ?

Why class in the Baltic States? (I) • Dictionaries and encyclopaedias describe as central task of sociology analysis of social structure – differentiation of populations into interrelated groups • There is a lot of research on this subject in all Baltic States, using data of national statistics, but it almost never uses class concept. Besides, available research on socio-economic structure (1) Undertheorized (e. g. income strata are called “classes”), or (2) Is limited to single country or (3) lacks cumulativity (if theorized) So good analysis of social structure should be (1) theory-guided, (2) internationally comparative, and (3) contribute to some cumulative research agenda Main obstacle: lack of appropriate data: National census data usually are incomplete to answer theory-driven questions about social structure; survey data lack comparability and sometimes representativeness. So we know less than we may want to know about the social structure of Baltic States, and we have just nothing about their class structures in comparative way (!!!)

data VU, fakultetas

Data sources of internationally comparative class structure research Best data sources for internationally comparative social research, are, of course, continuing social surveys: Eurobarometer, European value survey (EVS) and ) World value survey (WVS), European Electoral Survey (EES), Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) etc. Of special value for research on social structure are data of International Social Survey Program (ISSP) and European Social Survey (ESS). According to expert consensus, biennal multi-country ESS data are best source of goals of internationally comparative social structure analysis. ESS Round 1 - 2002 ESS Round 2 - 2004 ESS Round 3 - 2006 ESS Round 4 – 2008 ESS Round 5 – 2010 ESS Round 6 – 2012 (Data not published yet) As a matter of principle, ESS questionnaires include core module and two rotating modules which change each round. Importantly, core module includes a set of questions designed to identify the class position of respondent!

Aim and data of contribution 2008 - ANNUS MIRABILIS for the comparative research on the class structures in the Baltic States Among all ESS rounds, only ESS 4 covers all three Baltic States. Lithuania did not participate in ESS 1 -3, and Latvia dropped in ESS 5 -6. The aim: to unveil of class structures of Baltic States against broad international background and explore of explanatory relevance of class for social inequality, ideological attitudes and political behaviour in Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and … Finland using the ESS 4 data (accessible at http: //ess. nsd. uib. no/ ) As a matter of fact, ESS 4 survey was conducted in Lithuania in 16. 10. 2009 - 12. 01. 2010, in Estonia – in 05. 11. 2008 - 11. 03. 2009, in Latvia – in 02. 04. 2009 -08. 09. 2009, in Finland – in 19. 09. 2008 - 05. 02. 2009. http: //ess. nsd. uib. no/streamer/? module=main&year=2009&country=null&download=%5 CSurvey+d ocumentation%5 C 2009%5 C 01%23 ESS 4+-+ESS 42008+Documentation+Report%2 C+ed. +5. 1%5 CLanguages%5 CEnglish%5 CESS 4 Data. Doc. Report_5. 1. pdf

Structure of Presentation 1. Explication of Conceptual Framework (what is Neo. Weberian analysis and why it is preferred to alternatives) 2. Presentation of the statistical tools of Neo-Weberian class analysis 3. Comparison and Discussion of the Models of Class Structure of 30 countries covered by ESS Round 4 4. Presentation of Some Findings of the Class Analysis of the Social Inequality, Ideological Attitudes, and Political Behavior in 4 Baltic States Why Finland? Actually, in the interwar time Finland was internationally perceived as one of Baltic countries. Presently, population of other Baltic countries (especially Estonians) consider Finland as a kind of “real utopia” – what could their countries become if not Soviet occupation in 1940 and what they will be like after catching up with more developed countries.

Weberian class analysis - what does it mean? By neo-Weberian class analysis we mean the application of the class schema elaborated by John Goldthorpe and Robert Erikson in 1980 s while working on the project Comparative Analysis of Social Mobility in Advanced Societies (CASMIN). According to established usage classes in question are called EGP classes, because it was published for the first time in the joint paper by three authors Robert Erikson; John Goldthorpe; Lucienne Portocarero. 1979. („Intergenerational Class Mobility in Three Western European Societies: England, France and Sweden“, The British Journal of Sociology, 1979 Vol. 30 (4), pp. 415 -441), EGP classes are neo-Weberian, because they elaborations of the Weber’s concepts of “Erwerbsklasse”, which can be freely translated as “labour market class”. As a matter of common knowledge, according to Max Weber there are three dimensions of social differentiation: market position, status (prestige), and political power. Market position is of paramount importance in the market or capitalist societies, while in precapitalist societies ascribed/inherited status may be much more important; and under state socialism access to political power did matter most What is capitalism or market society? A system of markets: capital market, land market, labour market etc. A human individual can take a position or role in a market. In capital market and land markets, there are owners, and not owners; in the labour market – employers and employees

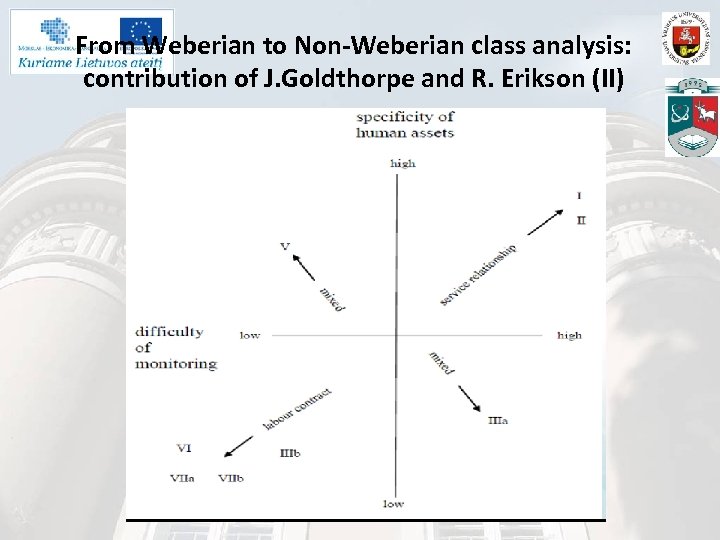

From Weberian to Non-Weberian class analysis: contribution of J. Goldthorpe and R. Erikson (I) Taking Max Weber by word, one can consider each occupation (profession) as labour market class, because professions (occupations) differ by their positions on the labour market. Occupation is a set of people occupying some specific labour market position. But are sociologists, locomotive drivers, plumbers etc. different classes? Obviously, such class concept is analytically useless. To get useful concept of labour market class, professions should be merged in a non-arbitrary way into limited number of units, which are internally homogeneous and externally heterogeneous (including most similar professions) J. Goldthorpe and R. Erikson accomplish this feat by supplementing Weberian analysis of occupations in terms of market positions by their comparison in terms of work positions of employees Classes=groupings of occupational positions defined by similar market and work situations Actually we are counting persons in positions, but are interested in persons

From Weberian to Non-Weberian class analysis: contribution of J. Goldthorpe and R. Erikson (II)

From Weberian to Non-Weberian class analysis: contribution of J. Goldthorpe and R. Erikson (III) Occupations differ as to specificity of human assets to working place – in some cases learning by doing or supplementary training is necessary Occupations differ depending on difficulty of solving principal-agent problem: how to make the employee to spend working time in the employers interest? Where both specificity of human assets is high and monitoring is difficult, employer and employee are related by trust or service relationship (job autonomy, prospect of promotion) Where specificity of human assets is low and monitoring is easy, they are related by work contract Intermediate cases: Monitoring easy, asset specificity high Monitoring difficult, asset specificity low + 3 more class-defining difference Superior/subordinate with subordinates or no (some superiors are superiors of suoperiors; others not) Agriculture/Non-Agriculture Manual/Non-Manual Work Total list of class-differentiating dimensions: (1) Labour market position (employer-employee); (2) Asset specificity; (3) Difficulty of monitoring; (4) Superior/subordinate (5) Economy Sector: Agriculture/non-Agriculture; (6) Manual /non-manual work

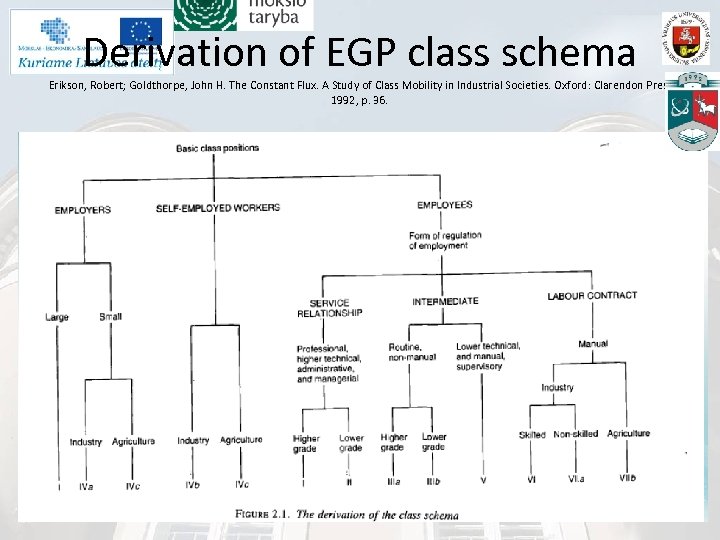

Derivation of EGP class schema Erikson, Robert; Goldthorpe, John H. The Constant Flux. A Study of Class Mobility in Industrial Societies. Oxford: Clarendon Pres, 1992, p. 36.

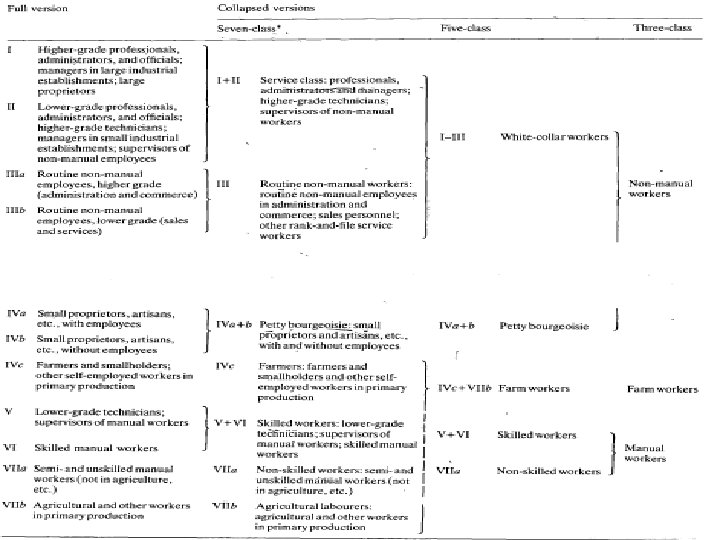

Full and collapsed versions of EGP schema data VU, fakultetas

EGP class models: pro et contra EGP class analysis can (and was) criticised both for neglecting important differences and for differentiating too much. E. g. why merging large employers with top employees in one class? Why not differentiating between small employers owners in the agriculture, while doing this in industry and services? Why services (tertiary sectory) merged with industry? Why farmers are considered as separate class even in most abstract three-class schema? Etc. etc. As a matter of principle, one can draw additional differences, getting even more increasing schema. However, increasingly differentiating scheme becomes increasingly difficult to apply because of lack appropriate data. While one can build three class models using census data, to apply 11 class models one needs purposely collected evidence. As a matter of principle, small classes are sociologically “invisible” in the surveys using representative samples. Even one “sees” them, it is difficult to have statistically significant findings, working with very small classes. This is one the reasons why J. Goldthorpe and his associates usually prefer to work with collapsed class models. So, in their famous social mobility in advanced Western societies research (CASMIN project) 7 class scheme is applied. We will follow their example in exploring explanatory relevance of class. However, ESS data provide unique opportunity to get even more differentiated picture of the class structure of Baltic societies after two decades of post-communist transformation.

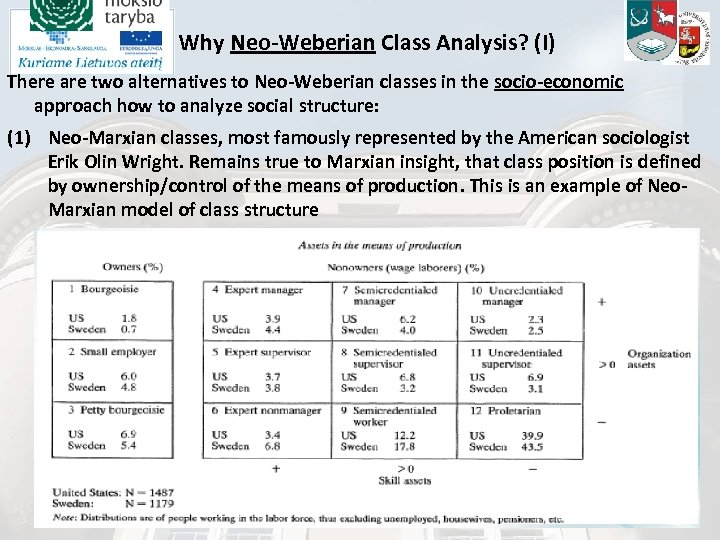

Why Neo-Weberian Class Analysis? (I) There are two alternatives to Neo-Weberian classes in the socio-economic approach how to analyze social structure: (1) Neo-Marxian classes, most famously represented by the American sociologist Erik Olin Wright. Remains true to Marxian insight, that class position is defined by ownership/control of the means of production. This is an example of Neo. Marxian model of class structure

Why Neo-Weberian Class Analysis? (II) (2) Classes as socioeconomic status (SES) categories (strata), derived from the measurement of socioeconomic status, defined by the three variables: (1) education (in years), (2) prestige of profession (ratings) and (3) income, agregated according to some specific formula. SES is atribute of persons (not positions), measured by continous variable. With SES scores for each member of population or its representative sample measured, population can divided into 3, 6, 10, … 100 hierarchically ordered strata (“classes”), according to the choice of cut-off values. Maximal possible number of classes is determined by the number of scores of the SES index. Most simple “class model” of this kind: lower class; middle class; upper class. E. g. Lower class: adult employed persons with 10≤SES≥ 30; middle 31≤SES≥ 70; upper 71≤SES≥ 100. We are not using SES “classes”, because they are no real classes (=sets of interrelated positions) , but just nominal arbitrary statistical aggregates. They may be useful for purposes of descriptive statistics, but not for „class analysis“ of classical type, where class position. There is no specific “class positions” in the “class structure” corresponding to some specific SES score or their range (say, 10≤SES≥ 30). Importantly, one cannot ask how income, prestige or education depends on class, because these variables are part of definition of SES. „Real“ classes are defined by the relations between class positions in a class structure, where representatives of different classes relate to each other as empoyers and employes, owners and non-owners, supervisors and subordinates etc. Weberian and Marxian class concepts have in common this „relational“ or “structural” view of classes. „Real“ classes are not „strata“ of human individuals, but sets of interrelated class positions (roles), which remain the same when some specific individuals take or leave them (=class mobility). Another shared insight: common class position defines (K. Marx) or may define common “class interest”. Obviously, all employers share interest to pay less for more work, and employees are “objectively interested” get more for less work

Statistical Tools of Neo-Weberian Class Analysis We prefer Neo-Weberian analysis because of two pragmatic reasons. (1) In the Baltic States, all “Marxian” things are rejected in advance and before any consideration (2) At this point of time, EGP schema is better operationalized and more broadly used as internationally standardized measure of occupational status. To apply its to ESS data, one should just to download from the website of Dutch sociologist Harry Ganzeboom: http: //home. fsw. vu. nl/hbg. ganzeboom/isco 88/index. htm This is the tool we use to derive from the ESS 4 data 11, 7, 5 and 3 classes models of 30 countries. For the analysis of the relationships between class position and social inequality, ideological orientations and political behaviour we employed statistical techniques known as Correspondence Analysis (CA) and Multiple Correspondence Analysis (MCA), famously used by Pierre Bourdieu in his books “Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste” and “Homo Academicus” with a similar goal – to analyse how class position determines person’s interests, likes, and dislikes

What MCA is and how to read its output Importantly, CA and MCA allows bivariate and multivariate statistical analyses with categorical variables and suits our analytic situation very well since the dependent variables – EGP class schemata - are built at the nominal level (and different in this respect form SES “classes”). One should not read Latin numerals I-VII in EGP class schemata as a reflection of order. Which class is at the “top” of the hierarchy, is an empirical research question, not part of its definition. Moreover, most of the variables measuring inequality of life chances and political attitudes/behaviour are also nominal or ordinal. Therefore, (M)CA is the best suited analytic approach in our situation. Its objectives are similar to those of MDS or factor analysis - to detect covariation between variables by identifying latent dimensions (factors) along which the most of the variance of the variables is explained. In most cases CA (simple or crossed-variables) was employed. We used weighted (with the exception of Lithuania where design weights are not available) data tables as input and also calculated Wald's statistical tests of association for bivariate analyses. MCA was used for exploring relations between EGP classes and distribution of life chances. In this case unweighted data were used since MCA for weighted data (to authors' knowledge) is not available. Both CA and MCA were performed with R (R Core Team, 2013) package Facto. Mine. R v 1. 25 (Husson, Josse, Le, Mazet, 2013).

What MCA is and how to read its output • Interpretation of the results of CA or MCA is very simple. It is a graphical method which allows to plot a joint graph of categories of variables (and individuals) or (in case of CA) of rows and columns of an input cross-tab. • Spatial locations of individuals (cases), categories of variables and row and column categories provide visual picture of the pattern of relationship between the variables that are analysed. • Simply put, the closer any two points (representing categories or individuals) are projected on the map the more related they are If two categories of different variables overlap, this means that exactly the same individuals selected the same two answer categories for these two questions. • Also, the more distant the points are from the origin, the more distinctive they are from the 'average‘. Therefore, points close to the origin of the map are not very 'interesting' during the interpretation of the results.

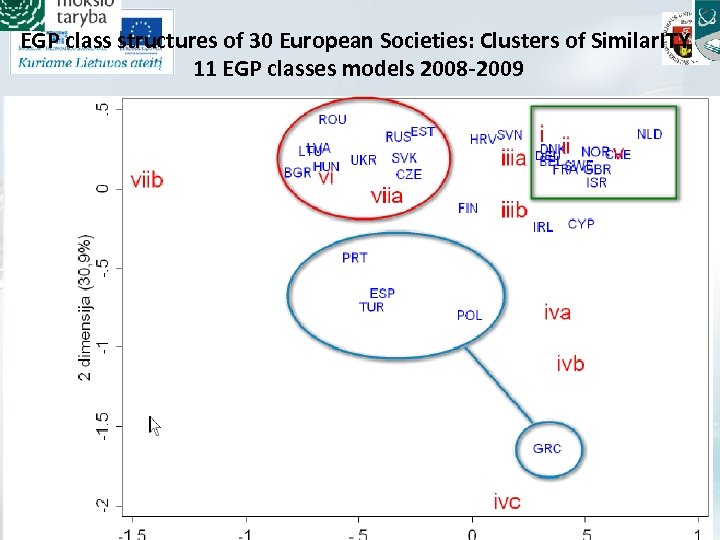

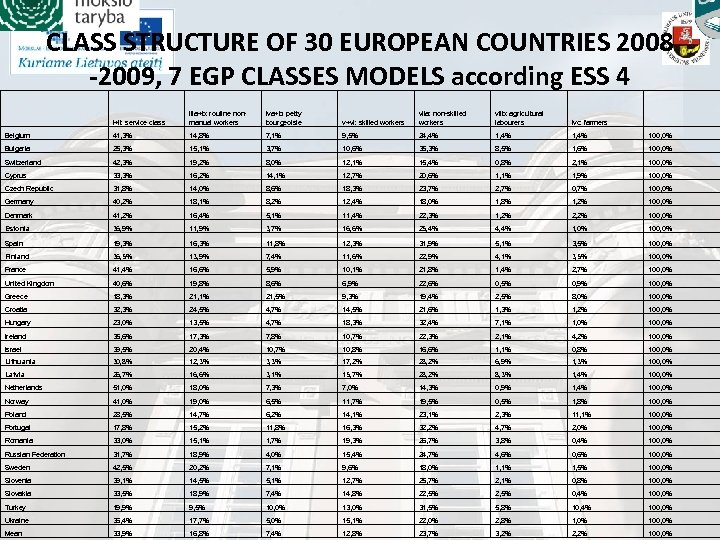

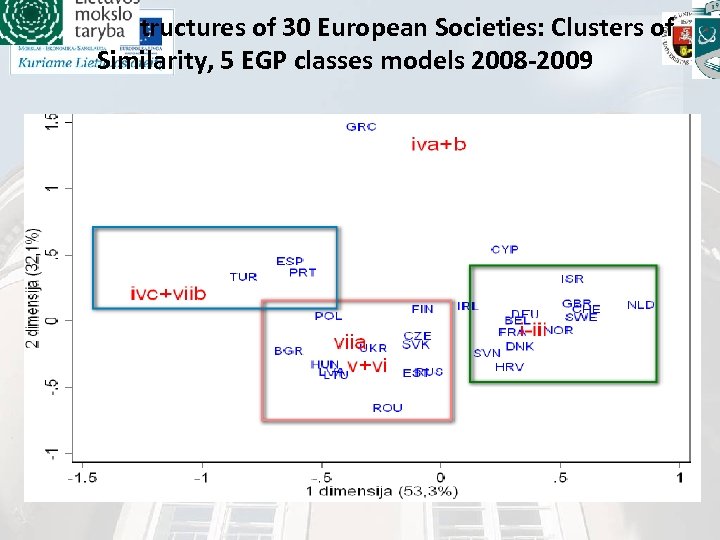

Some Findings of International Comparison of Class Structures : General Findings – Types of Class Societies (I) Applying MCA to 11, 7 and 5 EGP classes models we repeatedly detect three clusters of countries, and can identify basic similarities between them. This is the feature(s), which distinguish them from the sample mean. First cluster includes countries where service classes (or white collar classes) are quantitatively over-represented in comparison with mean (34% of service class; 50% of white collars). One can call the service class societies or, alternatively, white collar societies. They include mostly advanced technological frontier countries from Western and Northern Europe and Israel. Second cluster includes countries with relative predominance of manual worker (or blue collar) classes, for which 36, 5% is sample mean. Importantly, this cluster includes almost all former communist countries. Although there is no more “worker class dictatorship” in these countries , they remain worker class or blue collar society. Of course, there is no difficulty to interpret these findings from the standpoint of “grand sociological theory”. Alternatively, one can say that first cluster includes postindustrial economies and postindustrial societies, where manual workers are both relative and absolute minority. Differently, post-communist countries are still on the industrial stage and represent modern type of class structure.

Some Findings of International Comparison of Class Structures : General Findings – Types of Class Societies (II) There is some difficulty to place into this big picture countries from the third cluster, and to identify their common feature. It includes Southern European countries and, importantly, Poland. If one compares them in the framework of 11 and 7 class models, one is tempted to call these societies “petty bourgeois”. This does not mean that self-employed workers and small employers are in absolute or relative majority. In almost all European countries, petty bourgeois are in minority. Rather this would mean that the percentage of petty bourgeois classes is above the sample mean (7, 4%). Besides, other latent similaries and differences are taken into account. Therefore, the cluster of the “small bourgeois” countries in the comparison of 11 and 7 class models includes also Poland, where proportion of petty bourgeois is below the mean (6, 2%) and does not include Germany, which has 8, 2% of small employers and employees. When 5 EGP class models are compared, the deviation from the mean of the economically active population in the primary sector (5, 4%) emerges as crucial similarity. Membership in this cluster melts down to Turkey, Portugal, Spain, but Poland Bulgaria can also be included. One maybe can preliminary conclude by designating these countries as “undermodernized”. Intriguingly, in all three comparisons Greece emerges as an outlier, which can also be interpreted as extreme case of the “undermodernized” societies. With 21, 5% of self-employed and small employers in its economically active population, it can be designated as “petty bourgeois” society without reservations.

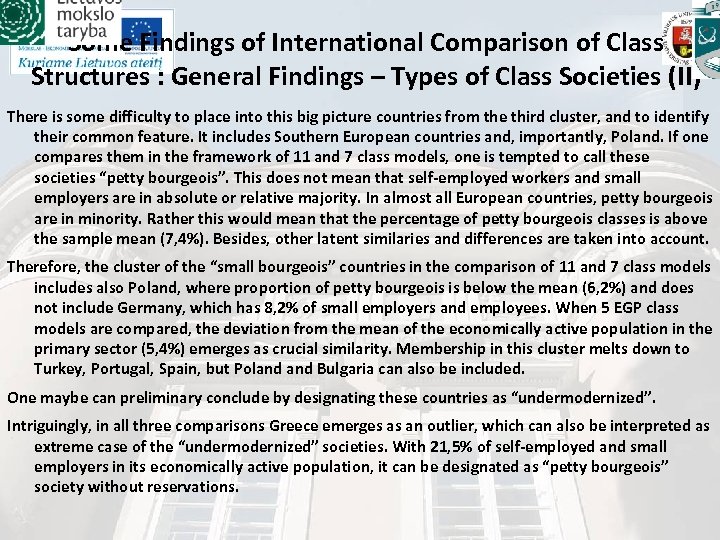

Social position (EGP 11) Total CLASS TRUCTURE OF 30 EUROPEAN COUNTRIES 2008 -2009, 11 EGP CLASSES MODELS according ESS 4 i: higher managerial ii: lower managerial iiia: routine clerical iiib: routine service-sales iva: self-empl. with empl. ivb: self-empl. no empl. v: manual supervisors vi: skilled worker viia: unskilled worker viib: agricultural labour ivc: self-empl. farmer Belgium 19, 2% 22, 1% 4, 9% 9, 9% 2, 8% 4, 3% 3, 0% 6, 4% 24, 4% 1, 4% 100, 0% Bulgaria 10, 4% 14, 9% 5, 1% 10, 0% 2, 0% 1, 6% 1, 2% 9, 3% 35, 3% 8, 5% 1, 6% 100, 0% Switzerland 15, 5% 26, 8% 11, 1% 8, 2% 3, 1% 4, 9% 4, 3% 7, 8% 15, 4% 0, 8% 2, 1% 100, 0% Cyprus 13, 4% 20, 0% 4, 9% 11, 3% 6, 2% 7, 9% 4, 4% 8, 3% 20, 6% 1, 1% 1, 9% 100, 0% Czech Republic 11, 0% 20, 8% 6, 7% 7, 4% 2, 4% 6, 3% 1, 6% 16, 7% 23, 7% 2, 7% 0, 7% 100, 0% Germany 18, 4% 21, 8% 9, 8% 8, 4% 3, 3% 4, 9% 4, 0% 8, 4% 18, 0% 1, 8% 1, 2% 100, 0% Denmark 18, 6% 22, 6% 7, 1% 9, 4% 3, 2% 1, 9% 3, 7% 7, 7% 22, 3% 1, 2% 2, 2% 100, 0% Estonia 21, 0% 15, 9% 3, 2% 8, 7% 1, 5% 2, 2% 3, 6% 13, 0% 25, 4% 4, 4% 1, 0% 100, 0% Spain 9, 2% 10, 0% 7, 5% 8, 8% 5, 0% 6, 8% 1, 9% 10, 4% 31, 9% 5, 1% 3, 5% 100, 0% Finland 16, 5% 20, 0% 4, 3% 9, 6% 3, 2% 4, 2% 1, 5% 10, 1% 22, 9% 4, 1% 3, 5% 100, 0% France 16, 5% 24, 9% 7, 0% 9, 5% 2, 4% 3, 5% 6, 7% 21, 8% 1, 4% 2, 7% 100, 0% United Kingdom 19, 6% 21, 0% 5, 3% 14, 6% 1, 8% 6, 8% 2, 8% 4, 1% 22, 6% 0, 5% 0, 9% 100, 0% Greece 7, 6% 10, 7% 5, 3% 15, 8% 6, 5% 15, 0% 1, 7% 7, 6% 19, 4% 2, 5% 8, 0% 100, 0% Croatia 14, 5% 17, 7% 10, 6% 13, 9% 2, 5% 2, 3% 3, 0% 11, 4% 21, 6% 1, 3% 1, 2% 100, 0% Hungary 8, 6% 14, 4% 5, 8% 7, 8% 1, 6% 3, 1% 2, 3% 15, 9% 32, 4% 7, 1% 1, 0% 100, 0% Ireland 16, 1% 19, 5% 3, 5% 13, 8% 3, 0% 4, 8% 3, 2% 7, 4% 22, 3% 2, 1% 4, 2% 100, 0% Israel 19, 2% 20, 3% 7, 9% 12, 5% 3, 2% 7, 5% 3, 3% 7, 5% 16, 6% 1, 1% 0, 8% 100, 0% Lithuania 13, 2% 17, 6% 4, 3% 8, 0% 1, 5% 1, 8% 0, 2% 16, 9% 28, 2% 6, 9% 1, 3% 100, 0% Latvia 11, 9% 14, 8% 7, 7% 9, 0% 1, 5% 1, 6% 2, 0% 13, 7% 28, 2% 8, 3% 1, 4% 100, 0% Netherlands 22, 8% 28, 3% 7, 5% 10, 5% 3, 2% 4, 1% 2, 7% 4, 3% 14, 3% 0, 9% 1, 4% 100, 0% Norway 17, 6% 23, 4% 9, 2% 9, 8% 2, 7% 3, 8% 4, 6% 7, 1% 19, 5% 0, 5% 1, 8% 100, 0% Poland 13, 7% 14, 8% 5, 0% 9, 7% 2, 3% 3, 9% 1, 8% 12, 3% 23, 1% 2, 3% 11, 1% 100, 0% Portugal 7, 7% 10, 1% 5, 9% 9, 3% 3, 3% 8, 6% 1, 7% 14, 5% 32, 2% 4, 7% 2, 0% 100, 0% Romania 20, 0% 13, 0% 3, 3% 11, 9% 1, 0% 0, 7% 1, 1% 18, 2% 26, 7% 3, 8% 0, 4% 100, 0% Russian Federation 16, 2% 15, 5% 7, 8% 11, 1% 1, 7% 2, 3% 1, 7% 13, 7% 24, 7% 4, 6% 0, 6% 100, 0% Sweden 16, 9% 25, 7% 5, 4% 14, 8% 2, 3% 4, 8% 1, 8% 7, 8% 18, 0% 1, 1% 1, 5% 100, 0% Slovenia 16, 8% 22, 3% 6, 4% 8, 1% 2, 0% 3, 1% 4, 0% 8, 7% 25, 7% 2, 1% 0, 8% 100, 0% Slovakia 16, 3% 17, 3% 10, 8% 8, 1% 3, 1% 4, 3% 2, 0% 12, 8% 22, 5% 0, 4% 100, 0% Turkey 7, 0% 13, 0% 2, 0% 7, 4% 3, 8% 6, 1% 1, 8% 11, 2% 31, 5% 5, 8% 10, 4% 100, 0% Ukraine 19, 1% 17, 3% 8, 1% 9, 6% 1, 5% 3, 5% 1, 6% 13, 5% 22, 0% 2, 8% 1, 0% 100, 0% Mean 15, 3% 18, 6% 6, 5% 10, 3% 2, 8% 4, 6% 2, 5% 10, 3% 23, 7% 3, 2% 2, 2% 100, 0%

EGP class structures of 30 European Societies: Clusters of Similar. ITY, 11 EGP classes models 2008 -2009

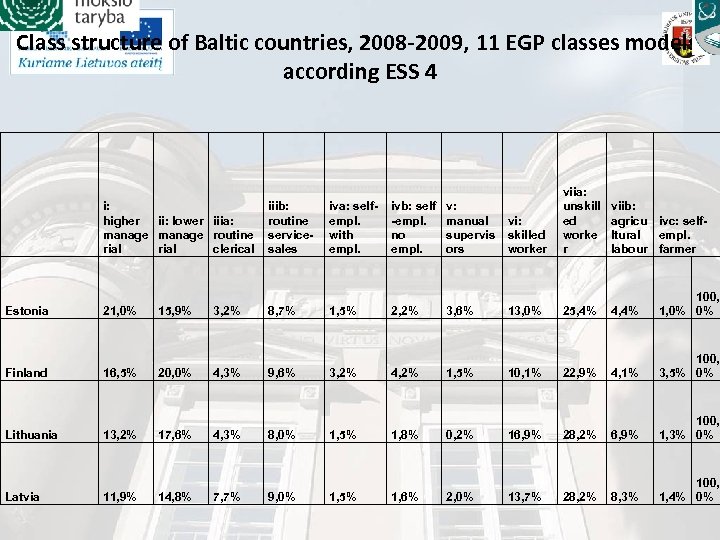

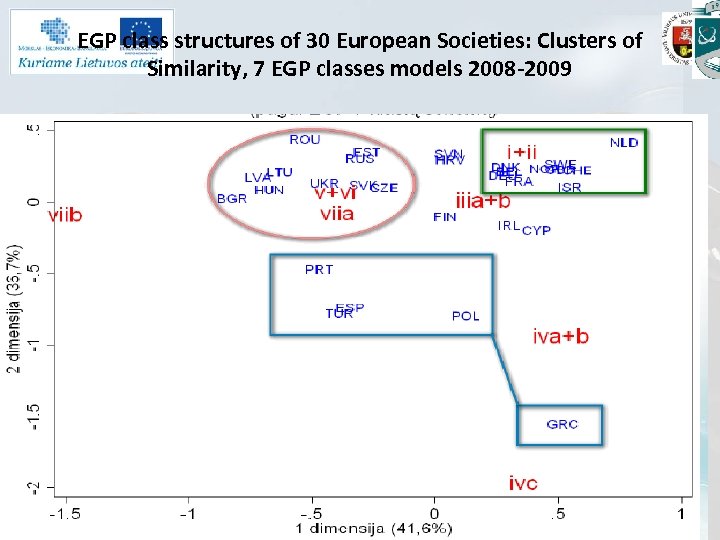

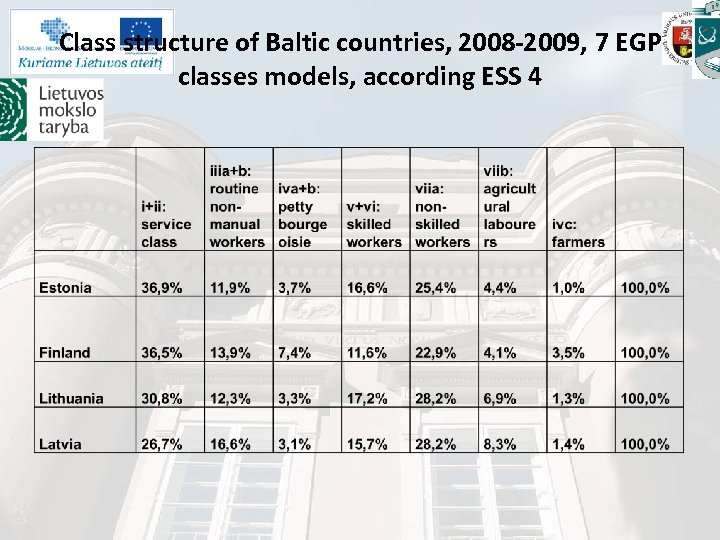

Class structure of Baltic countries, 2008 -2009, 11 EGP classes models, according ESS 4 i: higher ii: lower iiia: manage routine rial clerical Estonia iiib: routine servicesales iva: selfempl. with empl. ivb: self -empl. no empl. v: manual supervis ors vi: skilled worker viia: unskill ed worke r 21, 0% 8, 7% 1, 5% 2, 2% 3, 6% 13, 0% 25, 4% 15, 9% 3, 2% viib: agricu ivc: selfltural empl. labour farmer 4, 4% 100, 1, 0% 0% Finland 16, 5% 20, 0% 4, 3% 9, 6% 3, 2% 4, 2% 1, 5% 10, 1% 22, 9% 4, 1% 100, 3, 5% 0% Lithuania 13, 2% 17, 6% 4, 3% 8, 0% 1, 5% 1, 8% 0, 2% 16, 9% 28, 2% 6, 9% 100, 1, 3% 0% 8, 3% 100, 1, 4% 0% Latvia 11, 9% 14, 8% 7, 7% 9, 0% 1, 5% 1, 6% 2, 0% 13, 7% 28, 2%

CLASS STRUCTURE OF 30 EUROPEAN COUNTRIES 2008 -2009, 7 EGP CLASSES MODELS according ESS 4 i+ii: service class iiia+b: routine nonmanual workers iva+b: petty bourgeoisie v+vi: skilled workers viia: non-skilled workers viib: agricultural labourers ivc: farmers Belgium 41, 3% 14, 8% 7, 1% 9, 5% 24, 4% 1, 4% 100, 0% Bulgaria 25, 3% 15, 1% 3, 7% 10, 6% 35, 3% 8, 5% 1, 6% 100, 0% Switzerland 42, 3% 19, 2% 8, 0% 12, 1% 15, 4% 0, 8% 2, 1% 100, 0% Cyprus 33, 3% 16, 2% 14, 1% 12, 7% 20, 6% 1, 1% 1, 9% 100, 0% Czech Republic 31, 8% 14, 0% 8, 6% 18, 3% 23, 7% 2, 7% 0, 7% 100, 0% Germany 40, 2% 18, 1% 8, 2% 12, 4% 18, 0% 1, 8% 1, 2% 100, 0% Denmark 41, 2% 16, 4% 5, 1% 11, 4% 22, 3% 1, 2% 2, 2% 100, 0% Estonia 36, 9% 11, 9% 3, 7% 16, 6% 25, 4% 4, 4% 1, 0% 100, 0% Spain 19, 3% 16, 3% 11, 8% 12, 3% 31, 9% 5, 1% 3, 5% 100, 0% Finland 36, 5% 13, 9% 7, 4% 11, 6% 22, 9% 4, 1% 3, 5% 100, 0% France 41, 4% 16, 6% 5, 9% 10, 1% 21, 8% 1, 4% 2, 7% 100, 0% United Kingdom 40, 6% 19, 8% 8, 6% 6, 9% 22, 6% 0, 5% 0, 9% 100, 0% Greece 18, 3% 21, 1% 21, 5% 9, 3% 19, 4% 2, 5% 8, 0% 100, 0% Croatia 32, 3% 24, 5% 4, 7% 14, 5% 21, 6% 1, 3% 1, 2% 100, 0% Hungary 23, 0% 13, 5% 4, 7% 18, 3% 32, 4% 7, 1% 1, 0% 100, 0% Ireland 35, 6% 17, 3% 7, 8% 10, 7% 22, 3% 2, 1% 4, 2% 100, 0% Israel 39, 5% 20, 4% 10, 7% 10, 8% 16, 6% 1, 1% 0, 8% 100, 0% Lithuania 30, 8% 12, 3% 3, 3% 17, 2% 28, 2% 6, 9% 1, 3% 100, 0% Latvia 26, 7% 16, 6% 3, 1% 15, 7% 28, 2% 8, 3% 1, 4% 100, 0% Netherlands 51, 0% 18, 0% 7, 3% 7, 0% 14, 3% 0, 9% 1, 4% 100, 0% Norway 41, 0% 19, 0% 6, 5% 11, 7% 19, 5% 0, 5% 1, 8% 100, 0% Poland 28, 5% 14, 7% 6, 2% 14, 1% 23, 1% 2, 3% 11, 1% 100, 0% Portugal 17, 8% 15, 2% 11, 8% 16, 3% 32, 2% 4, 7% 2, 0% 100, 0% Romania 33, 0% 15, 1% 1, 7% 19, 3% 26, 7% 3, 8% 0, 4% 100, 0% Russian Federation 31, 7% 18, 9% 4, 0% 15, 4% 24, 7% 4, 6% 0, 6% 100, 0% Sweden 42, 5% 20, 2% 7, 1% 9, 6% 18, 0% 1, 1% 1, 5% 100, 0% Slovenia 39, 1% 14, 5% 5, 1% 12, 7% 25, 7% 2, 1% 0, 8% 100, 0% Slovakia 33, 5% 18, 9% 7, 4% 14, 8% 22, 5% 0, 4% 100, 0% Turkey 19, 9% 9, 5% 10, 0% 13, 0% 31, 5% 5, 8% 10, 4% 100, 0% Ukraine 36, 4% 17, 7% 5, 0% 15, 1% 22, 0% 2, 8% 1, 0% 100, 0% Mean 33, 9% 16, 8% 7, 4% 12, 8% 23, 7% 3, 2% 2, 2% 100, 0%

EGP class structures of 30 European Societies: Clusters of Similarity, 7 EGP classes models 2008 -2009

Class structure of Baltic countries, 2008 -2009, 7 EGP classes models, according ESS 4

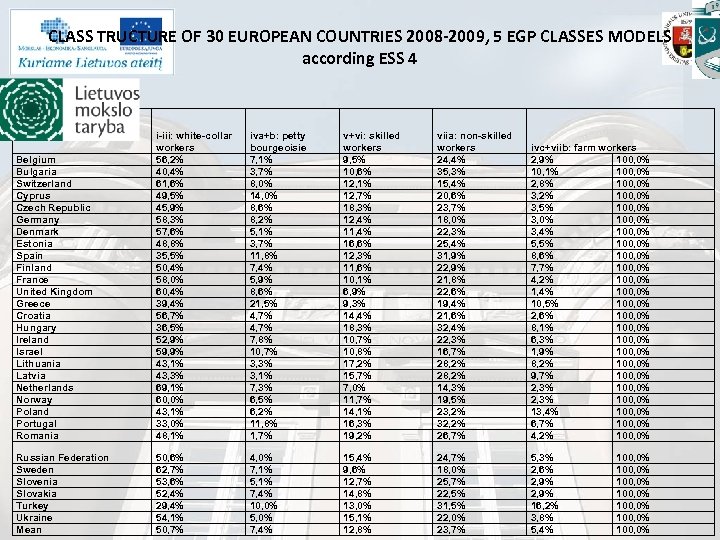

CLASS TRUCTURE OF 30 EUROPEAN COUNTRIES 2008 -2009, 5 EGP CLASSES MODELS according ESS 4 Belgium Bulgaria Switzerland Cyprus Czech Republic Germany Denmark Estonia Spain Finland France United Kingdom Greece Croatia Hungary Ireland Israel Lithuania Latvia Netherlands Norway Poland Portugal Romania i-iii: white-collar workers 56, 2% 40, 4% 61, 6% 49, 5% 45, 9% 58, 3% 57, 6% 48, 8% 35, 5% 50, 4% 58, 0% 60, 4% 39, 4% 56, 7% 36, 5% 52, 9% 59, 9% 43, 1% 43, 3% 69, 1% 60, 0% 43, 1% 33, 0% 48, 1% iva+b: petty bourgeoisie 7, 1% 3, 7% 8, 0% 14, 0% 8, 6% 8, 2% 5, 1% 3, 7% 11, 8% 7, 4% 5, 9% 8, 6% 21, 5% 4, 7% 7, 8% 10, 7% 3, 3% 3, 1% 7, 3% 6, 5% 6, 2% 11, 8% 1, 7% v+vi: skilled workers 9, 5% 10, 6% 12, 1% 12, 7% 18, 3% 12, 4% 11, 4% 16, 6% 12, 3% 11, 6% 10, 1% 6, 9% 9, 3% 14, 4% 18, 3% 10, 7% 10, 8% 17, 2% 15, 7% 7, 0% 11, 7% 14, 1% 16, 3% 19, 2% viia: non-skilled workers 24, 4% 35, 3% 15, 4% 20, 6% 23, 7% 18, 0% 22, 3% 25, 4% 31, 9% 22, 9% 21, 8% 22, 6% 19, 4% 21, 6% 32, 4% 22, 3% 16, 7% 28, 2% 14, 3% 19, 5% 23, 2% 32, 2% 26, 7% ivc+viib: farm workers 2, 9% 100, 0% 10, 1% 100, 0% 2, 8% 100, 0% 3, 2% 100, 0% 3, 5% 100, 0% 3, 0% 100, 0% 3, 4% 100, 0% 5, 5% 100, 0% 8, 6% 100, 0% 7, 7% 100, 0% 4, 2% 100, 0% 1, 4% 100, 0% 10, 5% 100, 0% 2, 6% 100, 0% 8, 1% 100, 0% 6, 3% 100, 0% 1, 9% 100, 0% 8, 2% 100, 0% 9, 7% 100, 0% 2, 3% 100, 0% 13, 4% 100, 0% 6, 7% 100, 0% 4, 2% 100, 0% Russian Federation Sweden Slovenia Slovakia Turkey Ukraine Mean 50, 6% 62, 7% 53, 6% 52, 4% 29, 4% 54, 1% 50, 7% 4, 0% 7, 1% 5, 1% 7, 4% 10, 0% 5, 0% 7, 4% 15, 4% 9, 6% 12, 7% 14, 8% 13, 0% 15, 1% 12, 8% 24, 7% 18, 0% 25, 7% 22, 5% 31, 5% 22, 0% 23, 7% 5, 3% 2, 6% 2, 9% 16, 2% 3, 8% 5, 4% 100, 0% 100, 0%

EGP class structures of 30 European Societies: Clusters of Similarity, 5 EGP classes models 2008 -2009

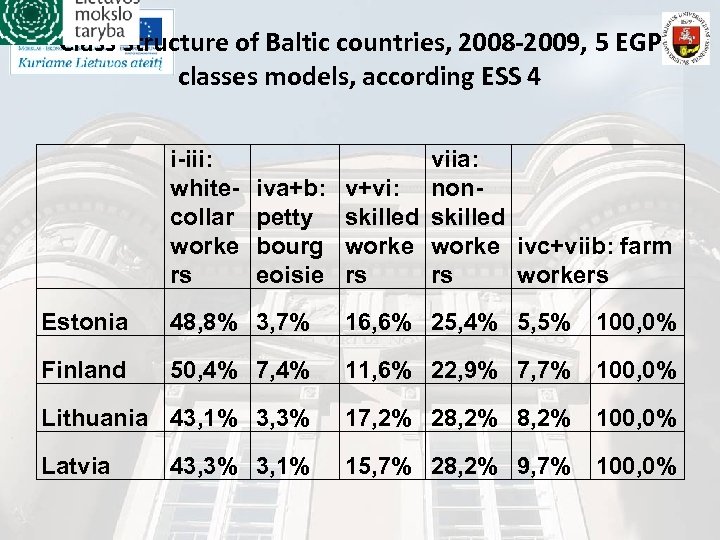

Class structure of Baltic countries, 2008 -2009, 5 EGP classes models, according ESS 4 i-iii: whitecollar worke rs viia: iva+b: v+vi: nonpetty skilled bourg worke ivc+viib: farm eoisie rs rs workers Estonia 48, 8% 3, 7% 16, 6% 25, 4% 5, 5% 100, 0% Finland 50, 4% 7, 4% 11, 6% 22, 9% 7, 7% 100, 0% Lithuania 43, 1% 3, 3% 17, 2% 28, 2% 100, 0% Latvia 15, 7% 28, 2% 9, 7% 100, 0% 43, 3% 3, 1%

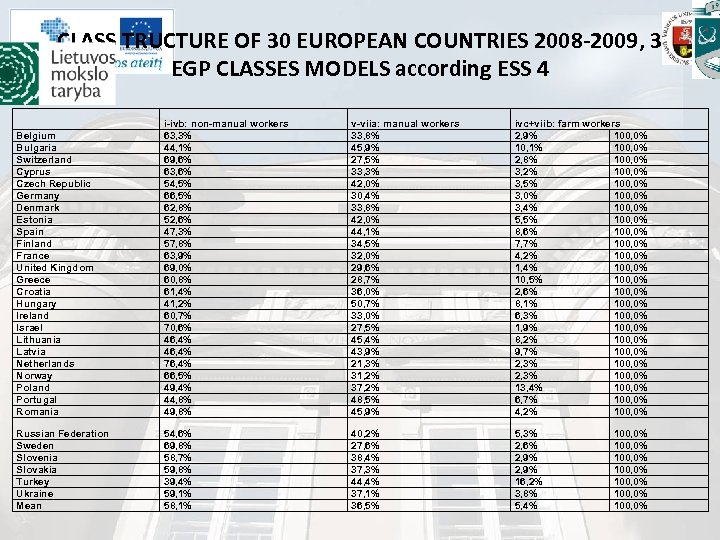

CLASS TRUCTURE OF 30 EUROPEAN COUNTRIES 2008 -2009, 3 EGP CLASSES MODELS according ESS 4 Belgium Bulgaria Switzerland Cyprus Czech Republic Germany Denmark Estonia Spain Finland France United Kingdom Greece Croatia Hungary Ireland Israel Lithuania Latvia Netherlands Norway Poland Portugal Romania i-ivb: non-manual workers 63, 3% 44, 1% 69, 6% 63, 6% 54, 5% 66, 5% 62, 8% 52, 6% 47, 3% 57, 8% 63, 9% 69, 0% 60, 8% 61, 4% 41, 2% 60, 7% 70, 6% 46, 4% 76, 4% 66, 5% 49, 4% 44, 8% 49, 8% v-viia: manual workers 33, 8% 45, 9% 27, 5% 33, 3% 42, 0% 30, 4% 33, 8% 42, 0% 44, 1% 34, 5% 32, 0% 29, 6% 28, 7% 36, 0% 50, 7% 33, 0% 27, 5% 45, 4% 43, 9% 21, 3% 31, 2% 37, 2% 48, 5% 45, 9% ivc+viib: farm workers 2, 9% 100, 0% 10, 1% 100, 0% 2, 8% 100, 0% 3, 2% 100, 0% 3, 5% 100, 0% 3, 0% 100, 0% 3, 4% 100, 0% 5, 5% 100, 0% 8, 6% 100, 0% 7, 7% 100, 0% 4, 2% 100, 0% 1, 4% 100, 0% 10, 5% 100, 0% 2, 6% 100, 0% 8, 1% 100, 0% 6, 3% 100, 0% 1, 9% 100, 0% 8, 2% 100, 0% 9, 7% 100, 0% 2, 3% 100, 0% 13, 4% 100, 0% 6, 7% 100, 0% 4, 2% 100, 0% Russian Federation Sweden Slovenia Slovakia Turkey Ukraine Mean 54, 6% 69, 8% 58, 7% 59, 8% 39, 4% 59, 1% 58, 1% 40, 2% 27, 6% 38, 4% 37, 3% 44, 4% 37, 1% 36, 5% 5, 3% 2, 6% 2, 9% 16, 2% 3, 8% 5, 4% 100, 0% 100, 0%

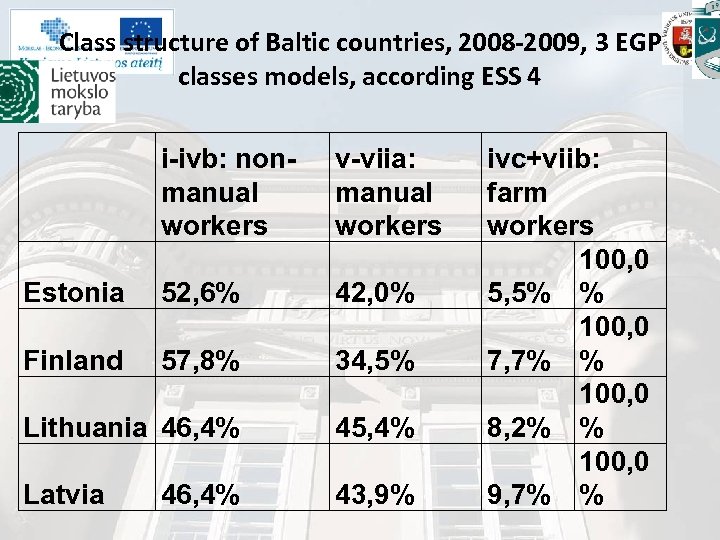

Class structure of Baltic countries, 2008 -2009, 3 EGP classes models, according ESS 4 i-ivb: nonmanual workers v-viia: manual workers Estonia 52, 6% 42, 0% Finland 57, 8% 34, 5% Lithuania 46, 4% 45, 4% Latvia 43, 9% 46, 4% ivc+viib: farm workers 100, 0 5, 5% % 100, 0 7, 7% % 100, 0 8, 2% % 100, 0 9, 7% %

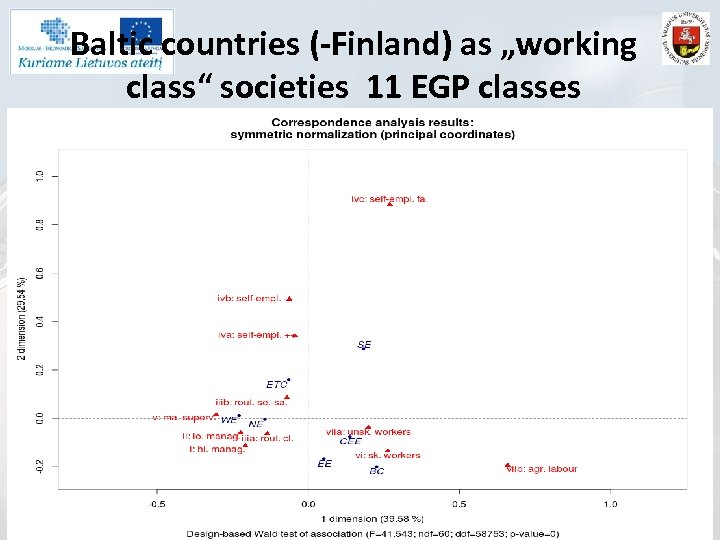

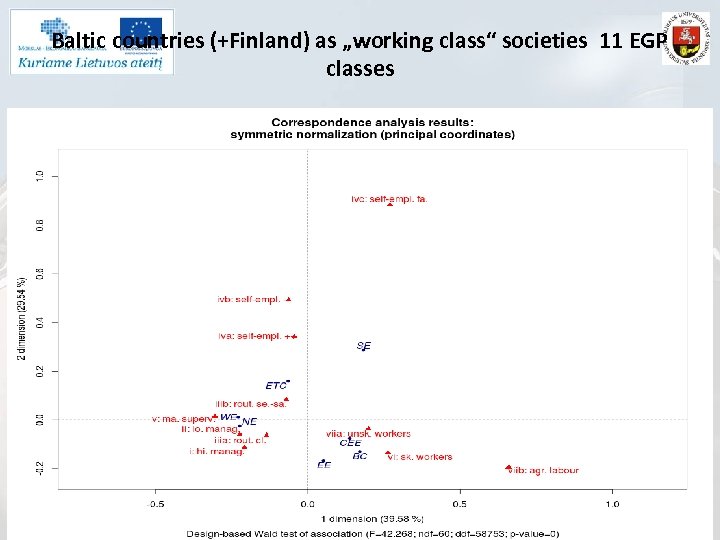

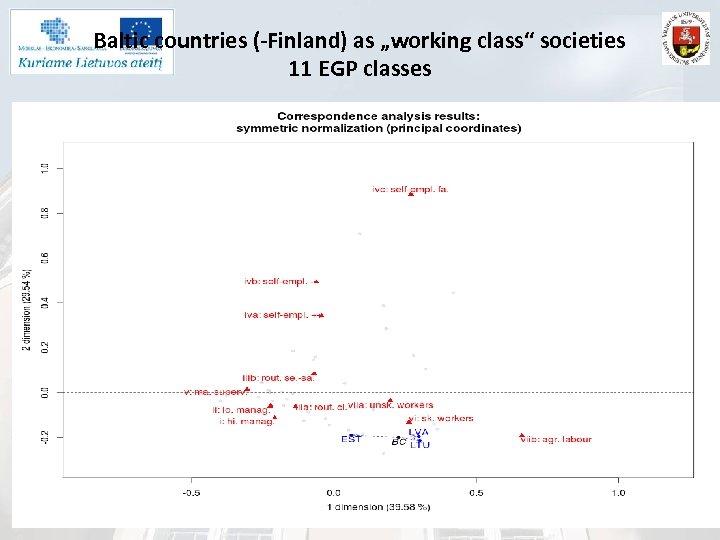

Some Findings of International Comparison of Class Structures : Specific Observations about Baltic States (I) • After 50 years of Soviet past, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, their economic and social structures were very similar at the very start of post-communist transformations. One cannot expect very much differences between them after 20 years transformation, as far as they pursued very similar economic policies, and represent the same “Baltic” model of postcommunist capitalism (or so one of the authors argues). • To provide comparison with more interesting variation, Finland is (re-)included into the list of Baltic States, as far as many Estonians and Latvians believe that their countries were on a par with Finland before WW II and now many of them consider this country as “reference country” or “real utopia” – what Lithuania, Latvia, Finland will look like after some 20 ? 30? . . . ? years.

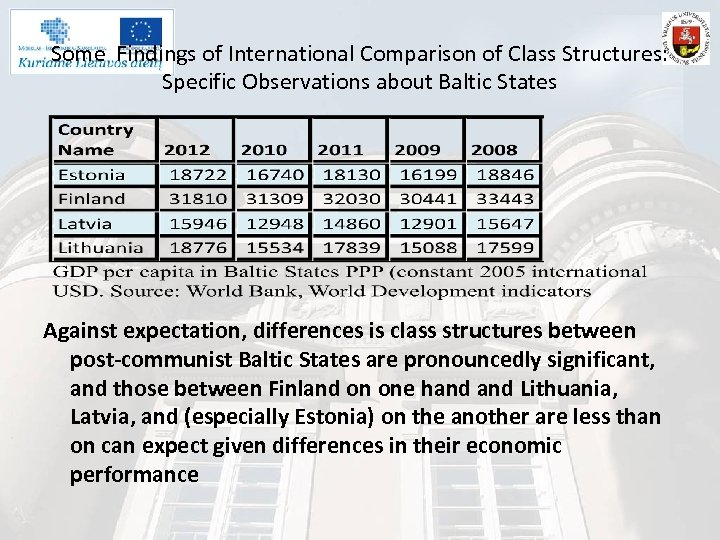

Some Findings of International Comparison of Class Structures: Specific Observations about Baltic States Against expectation, differences is class structures between post-communist Baltic States are pronouncedly significant, and those between Finland on one hand Lithuania, Latvia, and (especially Estonia) on the another are less than on can expect given differences in their economic performance

The relevance of general findings for “big” topics in research of post-communist transformation • The comparisons provide indirect evidence (despite Poland “strolling” with Southern European countries) that post-communist countries are “sui generis”, representing a specific variety of capitalism and capitalist class societies. • The comparisons help to bring clarity to the discussion about the “middle class” in post-communist countries which is reputed pillar of liberal democracy and overall stability. Is “middle class” already here, does it grow or diminish? • Looking to the problem from the viewpoint of EGP class theory, one can answer the question with resolute “yes”! Yes, there is middle class, and it is increasing. However, one should draw distinction between “old” and “new” middle classes. With partial exception for Poland, the “old” middle class (petty bourgeois) is (paradoxically) new in post-communist countries, and only slowly growing. • “New” middle class can be identified with service class, and in post-communist countries it is (paradoxically) old, because its growth was most rapid during the time of post-communist “turbomodernization”. Its rise was main cause of the breakdown of communism, because it was driving force of post-communist revolutions. Cp. Grzegorz Ekiert “The End of Communism in Central and Eastern Europe: The Last Middle Class Revolution? ” Political Power and Social Theory, Vol. 21, 2010, pp. 99 -123. • The doubts about the existence of middle class in post-communist countries express only trivial observation that service class in post-communist countries is less rich or affluent in comparison with its pendant in the “old West”. The problem is not the absence of middle class, but its lack of resources to live like members of service class in the more rich advanced Western countries are living.

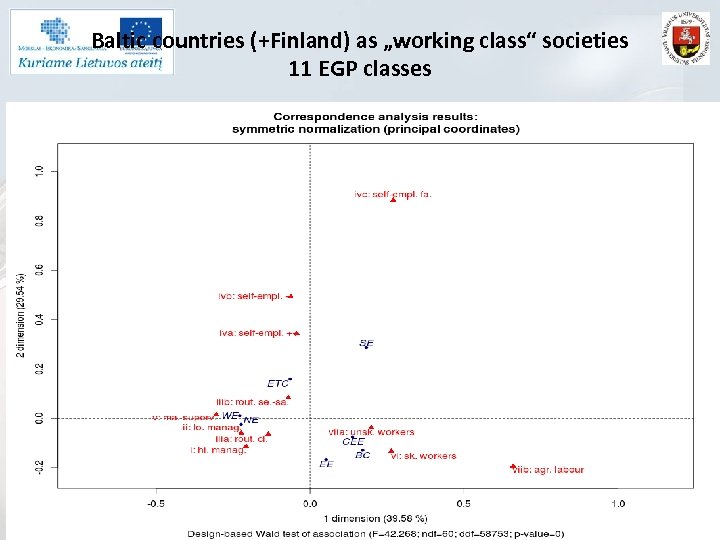

Baltic countries (-Finland) as „working class“ societies 11 EGP classes

Baltic countries (+Finland) as „working class“ societies 11 EGP classes data VU, fakultetas

Baltic countries (-Finland) as „working class“ societies 11 EGP classes

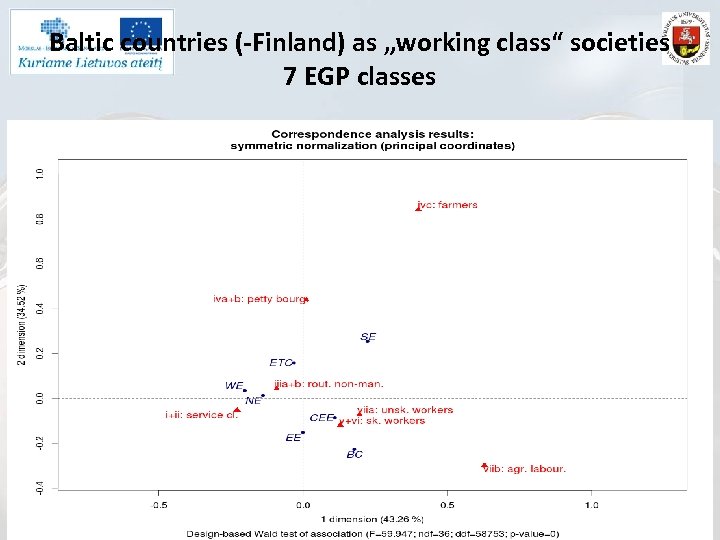

Baltic countries (-Finland) as „working class“ societies 7 EGP classes data VU, fakultetas

Baltic countries (-Finland) as „working class“ societies 7 EGP classes data VU, fakultetas

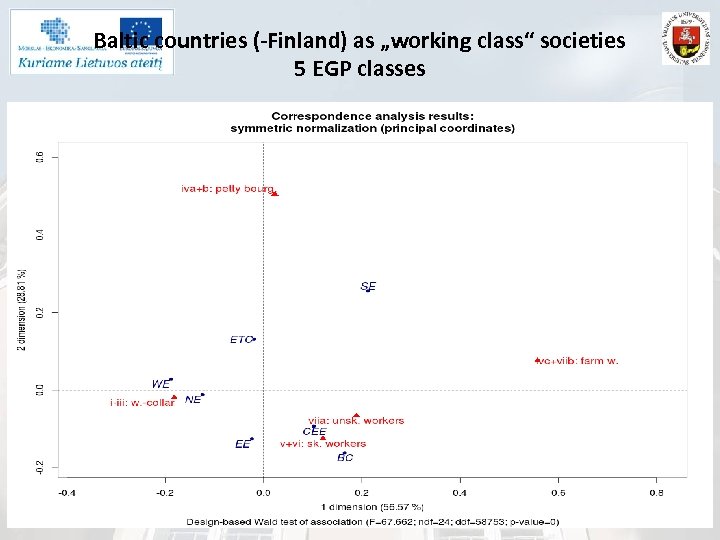

Baltic countries (-Finland) as „working class“ societies 5 EGP classes

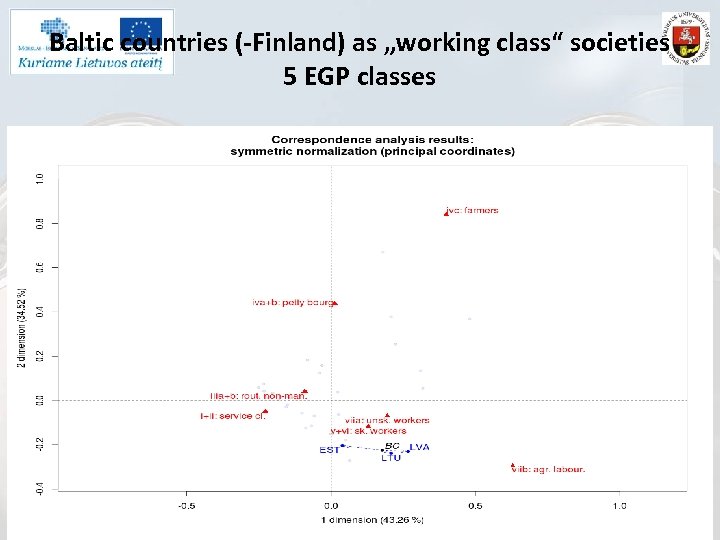

Baltic countries (-Finland) as „working class“ societies 5 EGP classes

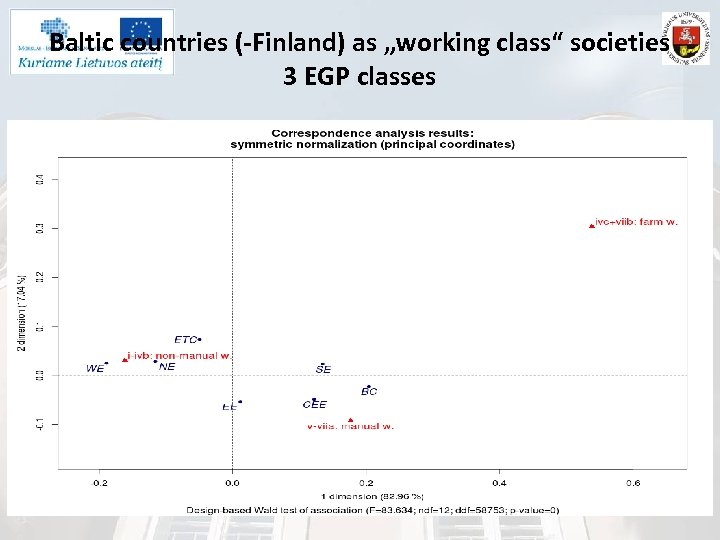

Baltic countries (-Finland) as „working class“ societies 3 EGP classes

Baltic countries (-Finland) as „working class“ societies 3 EGP classes

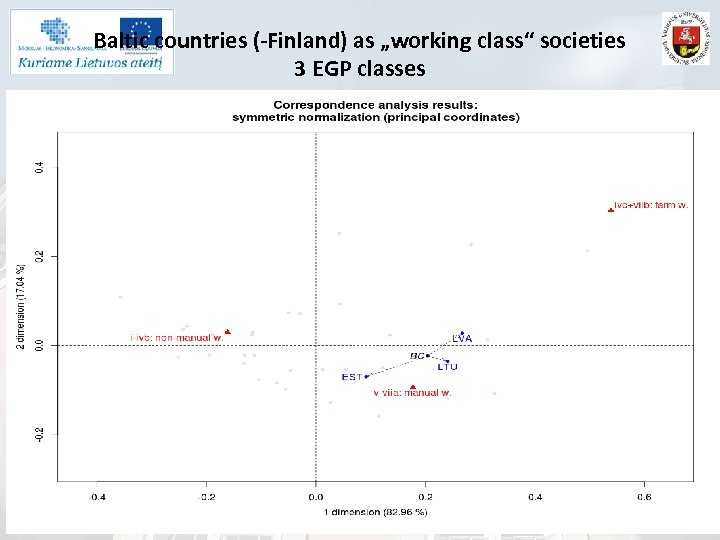

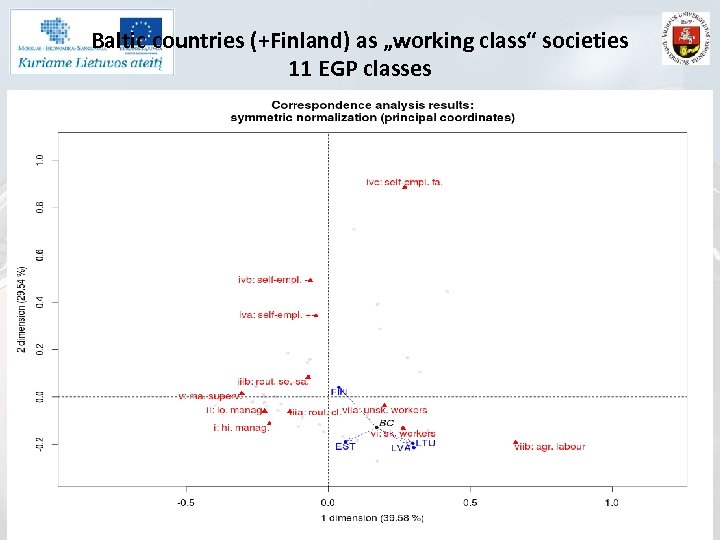

Baltic countries (+Finland) as „working class“ societies 11 EGP classes

Baltic countries (+Finland) as „working class“ societies 11 EGP classes data VU, fakultetas

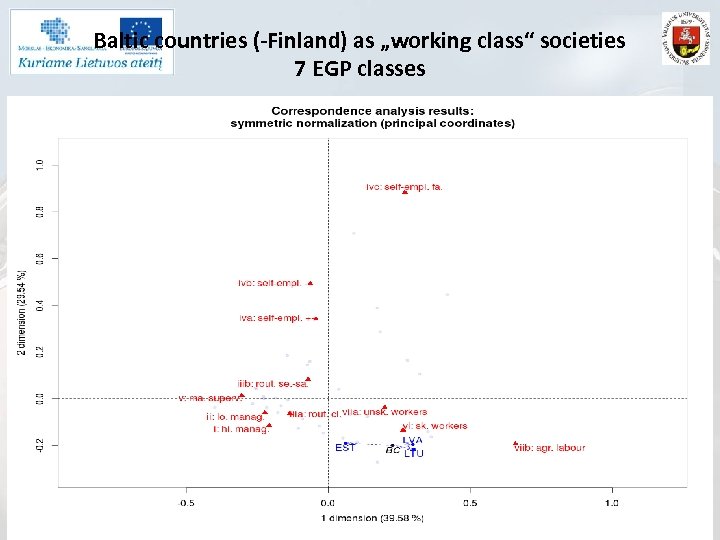

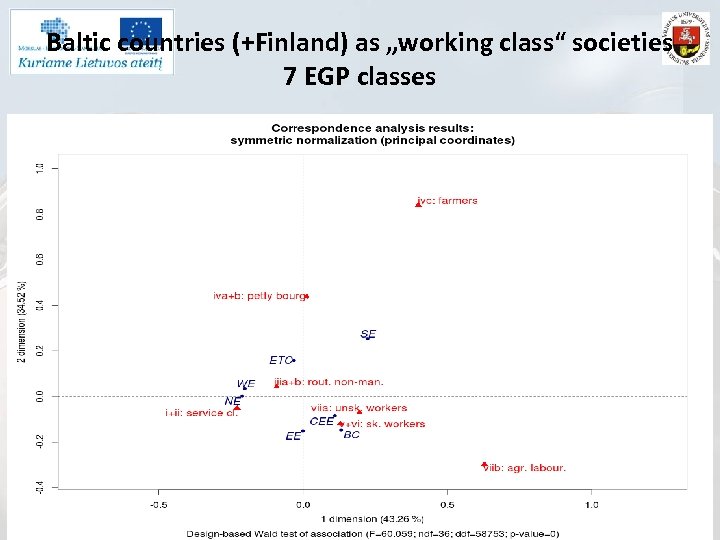

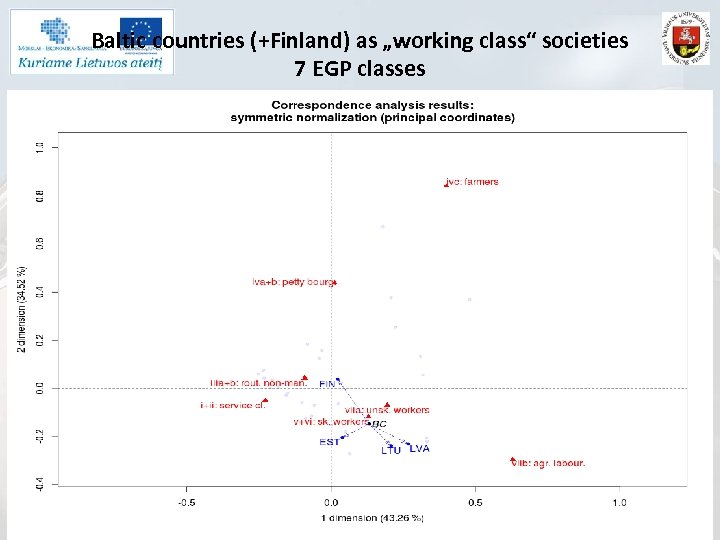

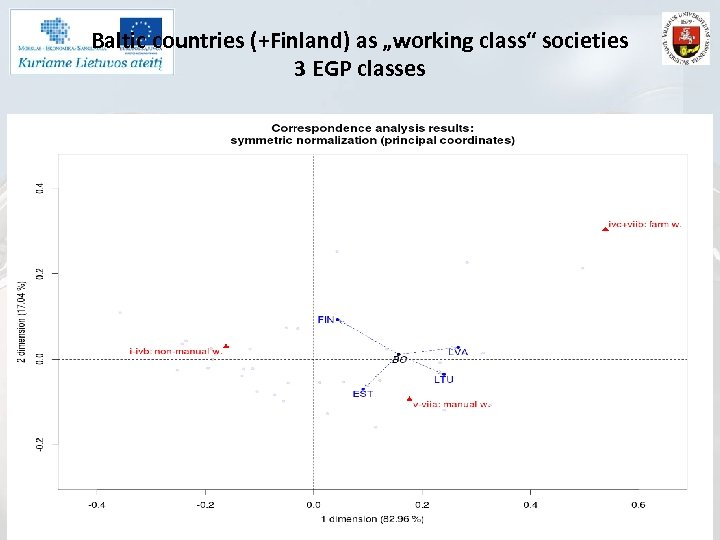

Baltic countries (+Finland) as „working class“ societies 7 EGP classes

Baltic countries (+Finland) as „working class“ societies 7 EGP classes

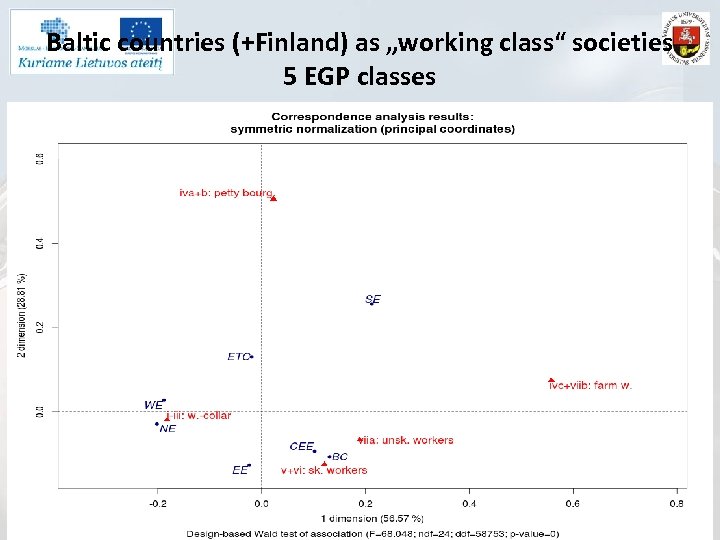

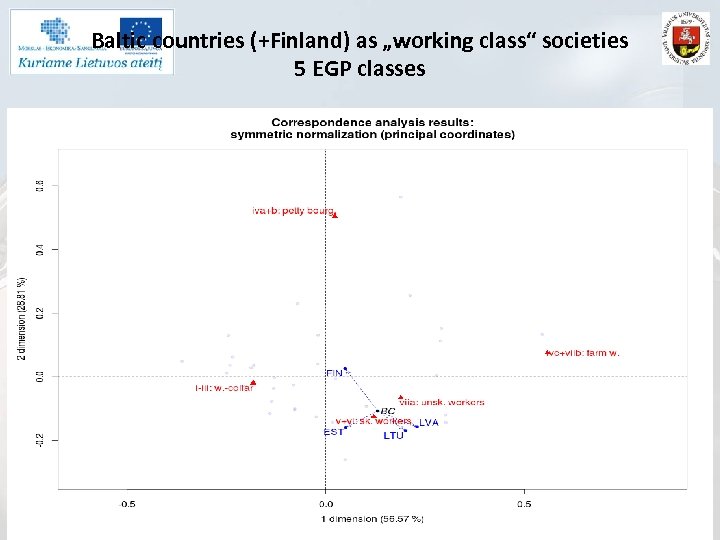

Baltic countries (+Finland) as „working class“ societies 5 EGP classes

Baltic countries (+Finland) as „working class“ societies 5 EGP classes

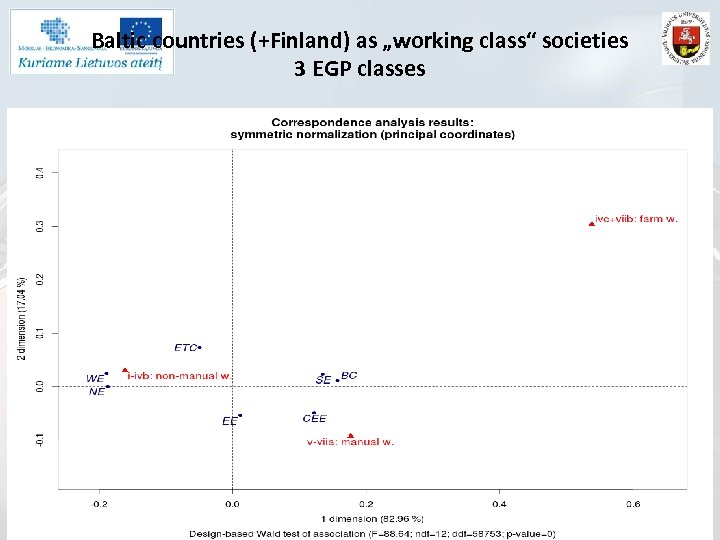

Baltic countries (+Finland) as „working class“ societies 3 EGP classes

Baltic countries (+Finland) as „working class“ societies 3 EGP classes

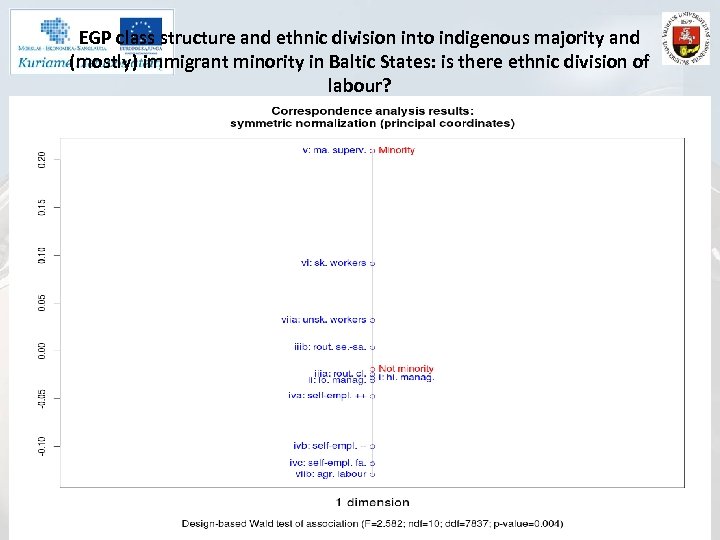

EGP class structure and ethnic division into indigenous majority and (mostly) immigrant minority in Baltic States: is there ethnic division of labour? data VU, fakultetas

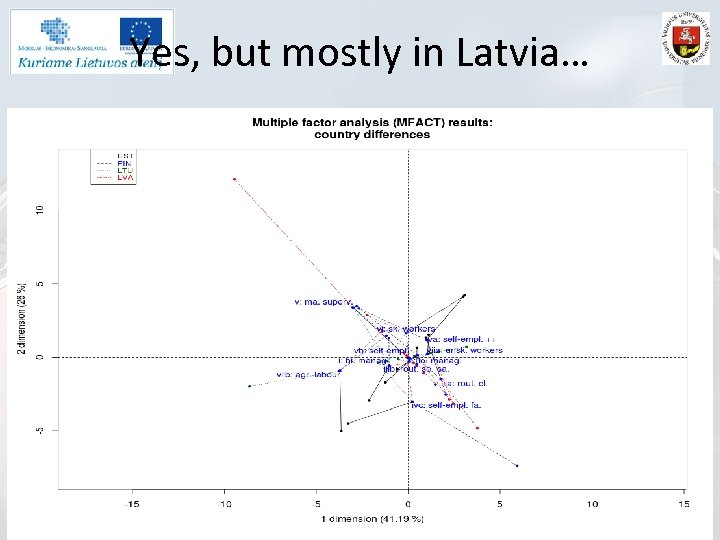

Yes, but mostly in Latvia…

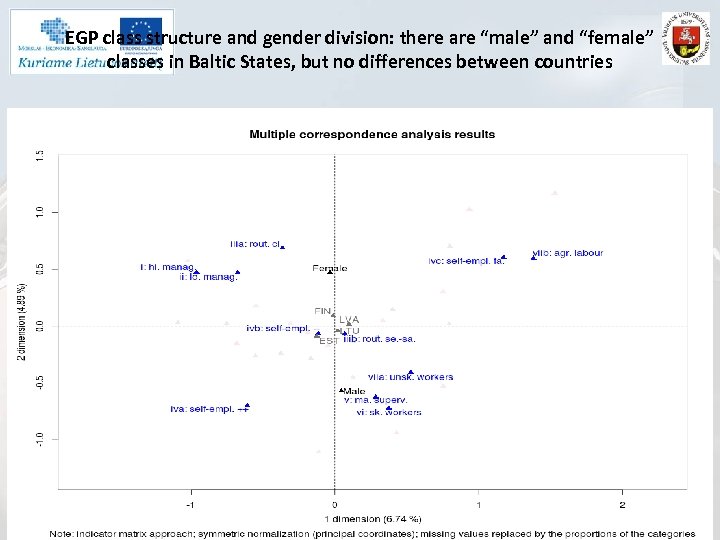

EGP class structure and gender division: there are “male” and “female” classes in Baltic States, but no differences between countries

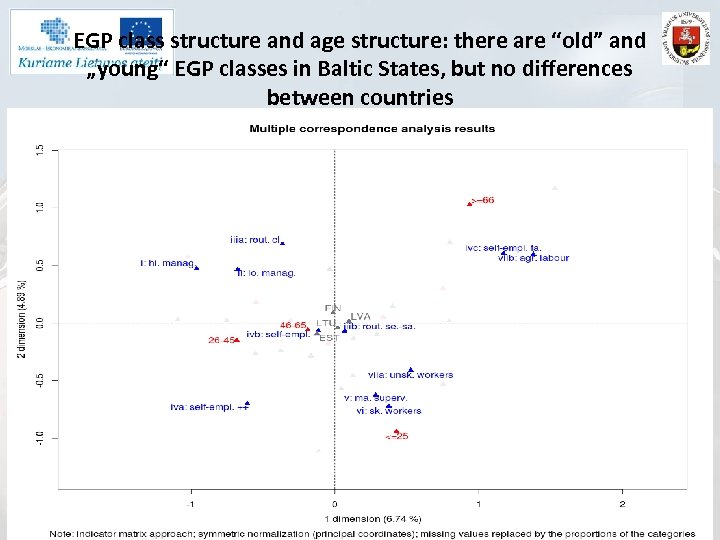

EGP class structure and age structure: there are “old” and „young“ EGP classes in Baltic States, but no differences between countries data VU, fakultetas

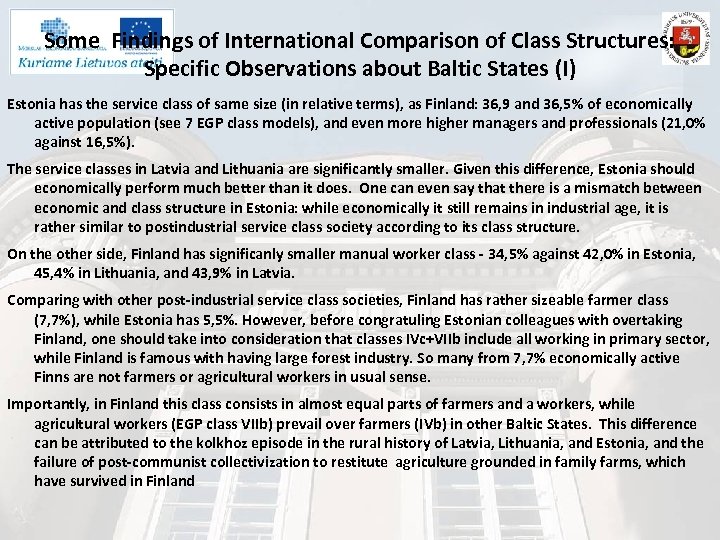

Some Findings of International Comparison of Class Structures: Specific Observations about Baltic States (I) Estonia has the service class of same size (in relative terms), as Finland: 36, 9 and 36, 5% of economically active population (see 7 EGP class models), and even more higher managers and professionals (21, 0% against 16, 5%). The service classes in Latvia and Lithuania are significantly smaller. Given this difference, Estonia should economically perform much better than it does. One can even say that there is a mismatch between economic and class structure in Estonia: while economically it still remains in industrial age, it is rather similar to postindustrial service class society according to its class structure. On the other side, Finland has significanly smaller manual worker class - 34, 5% against 42, 0% in Estonia, 45, 4% in Lithuania, and 43, 9% in Latvia. Comparing with other post-industrial service class societies, Finland has rather sizeable farmer class (7, 7%), while Estonia has 5, 5%. However, before congratuling Estonian colleagues with overtaking Finland, one should take into consideration that classes IVc+VIIb include all working in primary sector, while Finland is famous with having large forest industry. So many from 7, 7% economically active Finns are not farmers or agricultural workers in usual sense. Importantly, in Finland this class consists in almost equal parts of farmers and a workers, while agricultural workers (EGP class VIIb) prevail over farmers (IVb) in other Baltic States. This difference can be attributed to the kolkhoz episode in the rural history of Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia, and the failure of post-communist collectivization to restitute agriculture grounded in family farms, which have survived in Finland

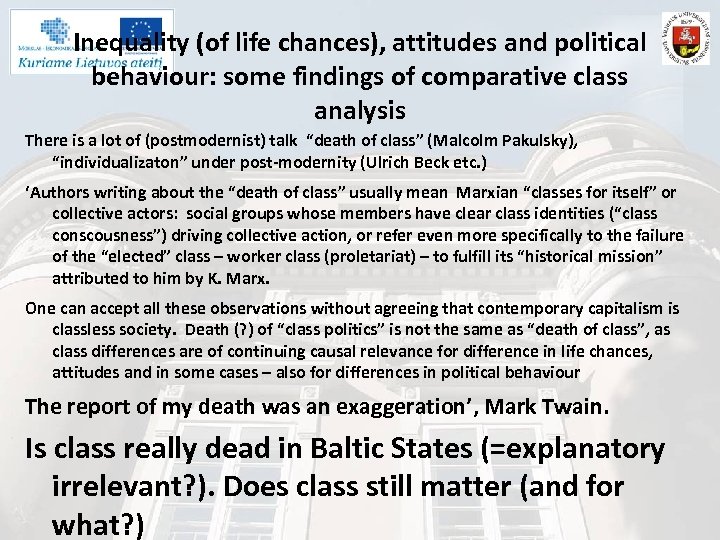

Inequality (of life chances), attitudes and political behaviour: some findings of comparative class analysis There is a lot of (postmodernist) talk “death of class” (Malcolm Pakulsky), “individualizaton” under post-modernity (Ulrich Beck etc. ) ‘Authors writing about the “death of class” usually mean Marxian “classes for itself” or collective actors: social groups whose members have clear class identities (“class conscousness”) driving collective action, or refer even more specifically to the failure of the “elected” class – worker class (proletariat) – to fulfill its “historical mission” attributed to him by K. Marx. One can accept all these observations without agreeing that contemporary capitalism is classless society. Death (? ) of “class politics” is not the same as “death of class”, as class differences are of continuing causal relevance for difference in life chances, attitudes and in some cases – also for differences in political behaviour The report of my death was an exaggeration’, Mark Twain. Is class really dead in Baltic States (=explanatory irrelevant? ). Does class still matter (and for what? )

Class and (good) life chances According to Max Weber, market position is main determinant of the (good) life chances of a person under conditions of capitalism (=market society). Social inequality=inequality of (good) life chances Before capitalism, to live a good life, you must have a luck of birth as offspring of high status group. Under capitalism, to have a good life, you need money, money and once more money: high income NB: in Marxian and Weberian class analysis classes ARE NOT income groups (this is SES view of class). You are not member of “top” class, because you are rich, but you are rich because you have advantageous class position (market position+work position). However, income is just intermediate variable in explanation of the (good) life chances. Income provides resources for (good) life, but can be badly spent (e. g. for drugs). Nevertheless, it is more easy to live good life with big income than live good life with small income. Importantly, not just size of income matters, but also steadiness of its stream. It is difficult to live good life without safety of its stream. Class positions differ in the social safety they provide. Important prediction of EGP theory: service class – most safe Indicators of good life: state of health (controlled for age); satisfaction with life; feeling of happiness etc. No possibility to test relation of class position and longevity using survey data

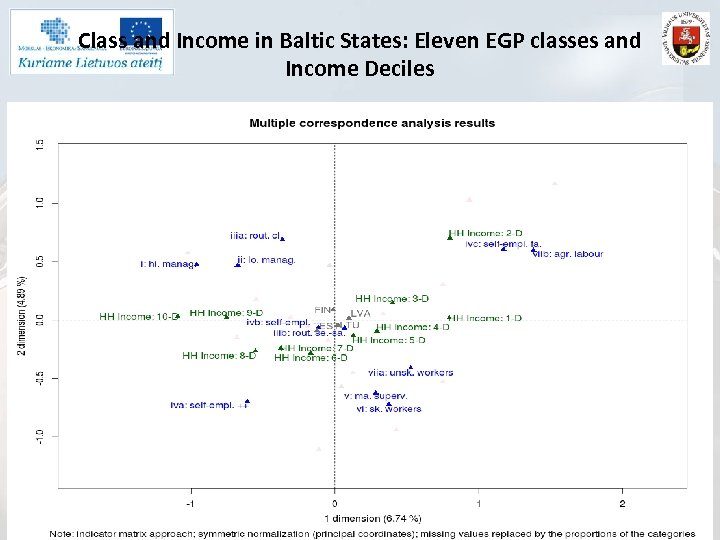

Class and Income in Baltic States: Eleven EGP classes and Income Deciles

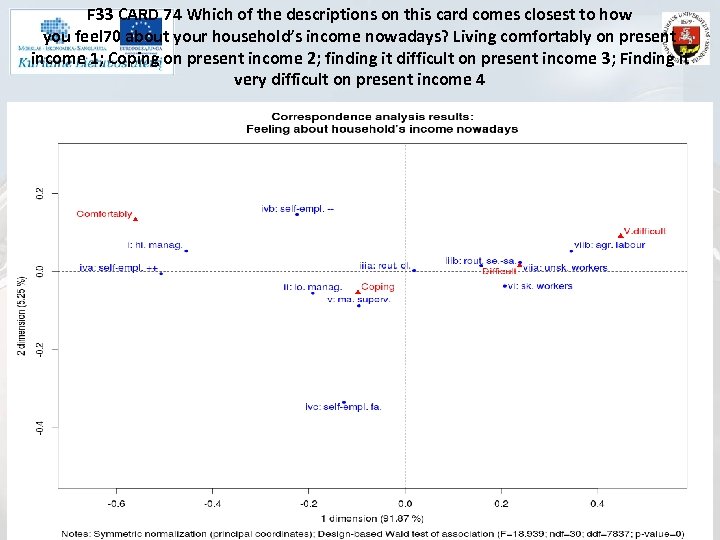

F 33 CARD 74 Which of the descriptions on this card comes closest to how you feel 70 about your household’s income nowadays? Living comfortably on present income 1; Coping on present income 2; finding it difficult on present income 3; Finding it very difficult on present income 4 data VU, fakultetas

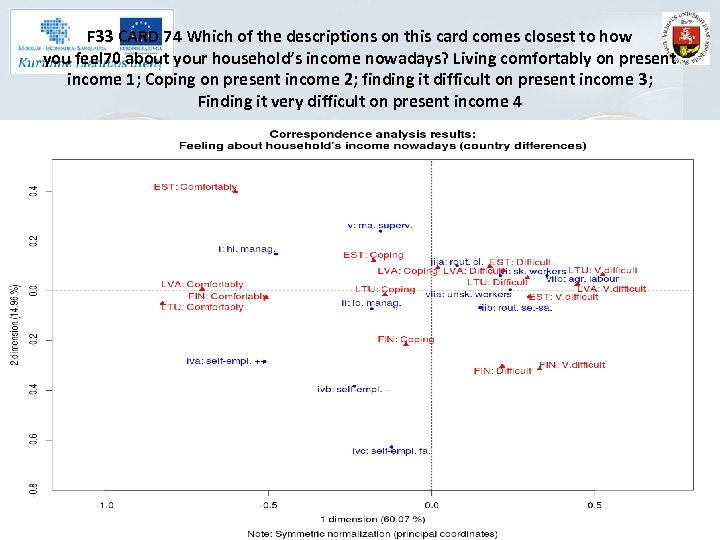

F 33 CARD 74 Which of the descriptions on this card comes closest to how you feel 70 about your household’s income nowadays? Living comfortably on present income 1; Coping on present income 2; finding it difficult on present income 3; Finding it very difficult on present income 4 data VU, fakultetas

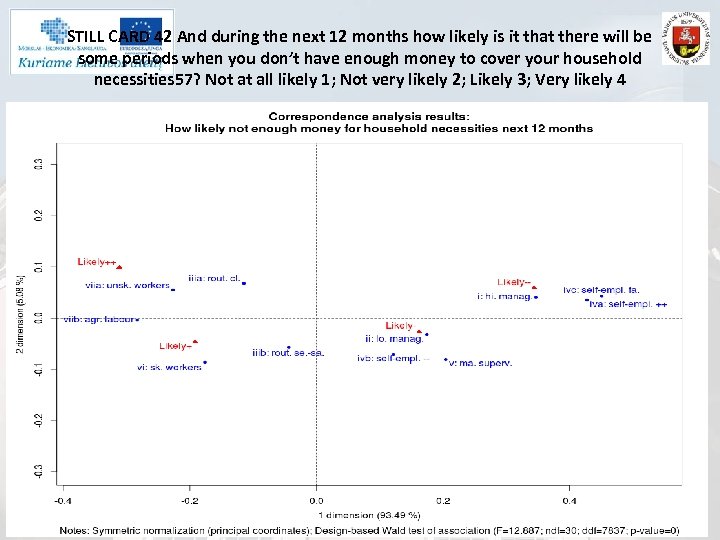

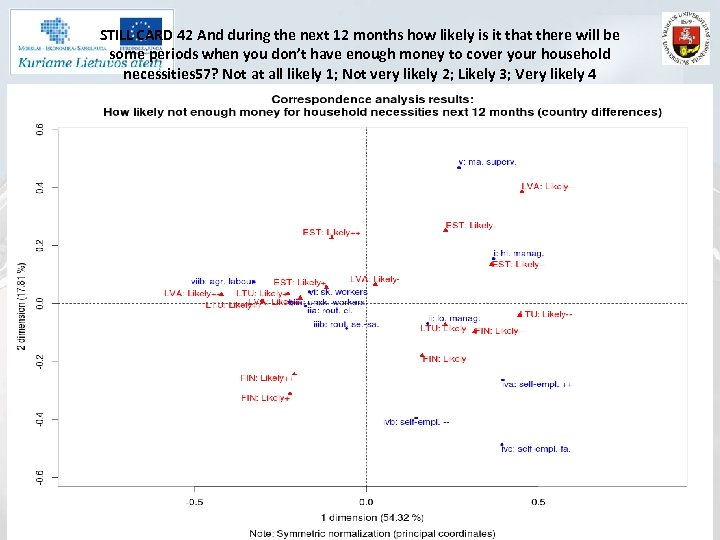

STILL CARD 42 And during the next 12 months how likely is it that there will be some periods when you don’t have enough money to cover your household necessities 57? Not at all likely 1; Not very likely 2; Likely 3; Very likely 4 data VU, fakultetas

STILL CARD 42 And during the next 12 months how likely is it that there will be some periods when you don’t have enough money to cover your household necessities 57? Not at all likely 1; Not very likely 2; Likely 3; Very likely 4 data VU, fakultetas

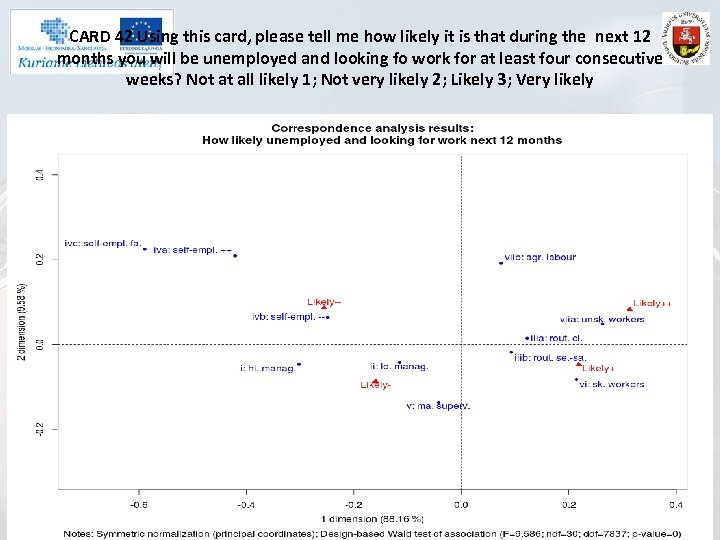

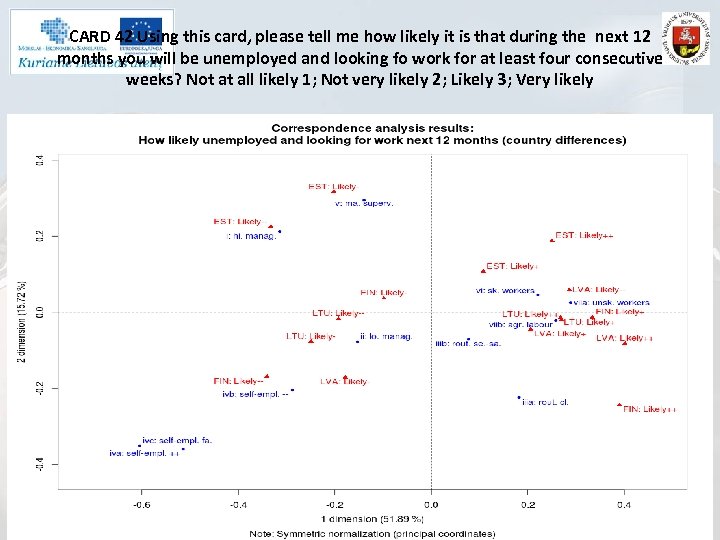

CARD 42 Using this card, please tell me how likely it is that during the next 12 months you will be unemployed and looking fo work for at least four consecutive weeks? Not at all likely 1; Not very likely 2; Likely 3; Very likely

CARD 42 Using this card, please tell me how likely it is that during the next 12 months you will be unemployed and looking fo work for at least four consecutive weeks? Not at all likely 1; Not very likely 2; Likely 3; Very likely data VU, fakultetas

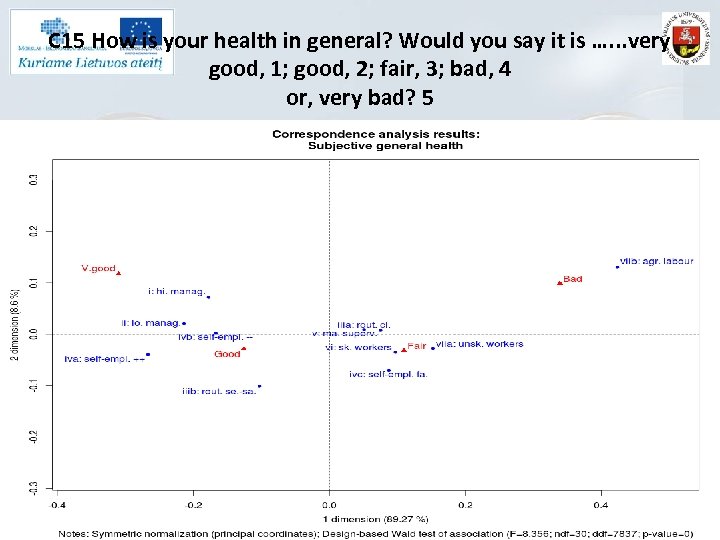

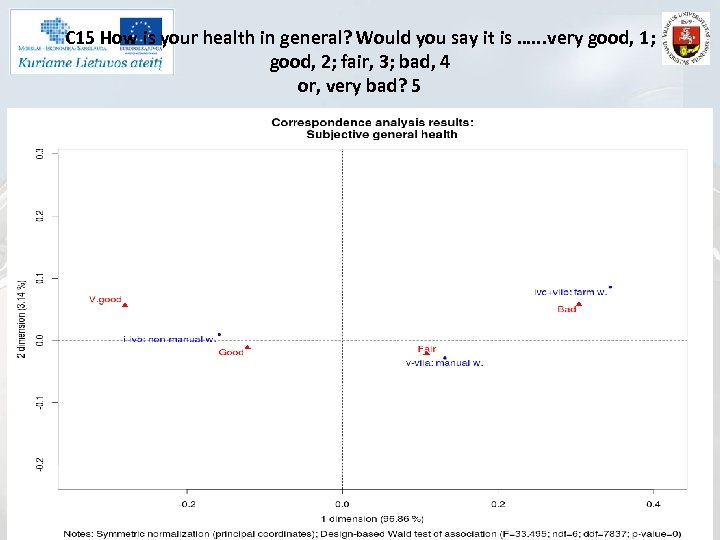

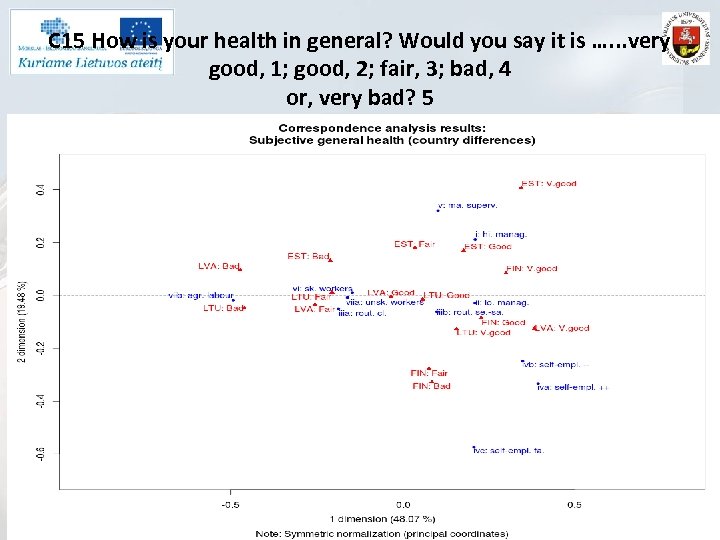

C 15 How is your health in general? Would you say it is …. . . very good, 1; good, 2; fair, 3; bad, 4 or, very bad? 5

C 15 How is your health in general? Would you say it is …. . . very good, 1; good, 2; fair, 3; bad, 4 or, very bad? 5 data VU, fakultetas

C 15 How is your health in general? Would you say it is …. . . very good, 1; good, 2; fair, 3; bad, 4 or, very bad? 5

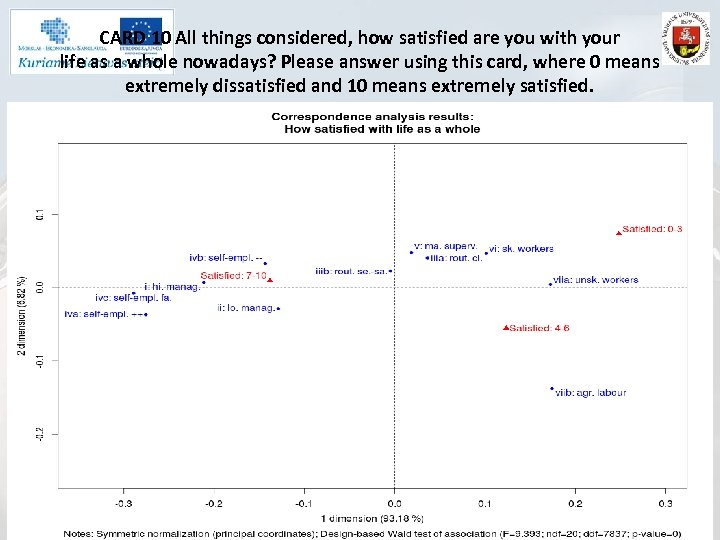

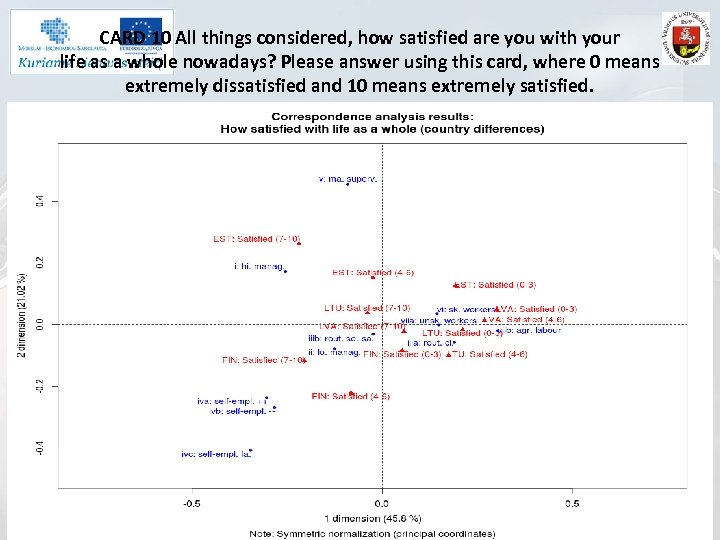

CARD 10 All things considered, how satisfied are you with your life as a whole nowadays? Please answer using this card, where 0 means extremely dissatisfied and 10 means extremely satisfied.

CARD 10 All things considered, how satisfied are you with your life as a whole nowadays? Please answer using this card, where 0 means extremely dissatisfied and 10 means extremely satisfied.

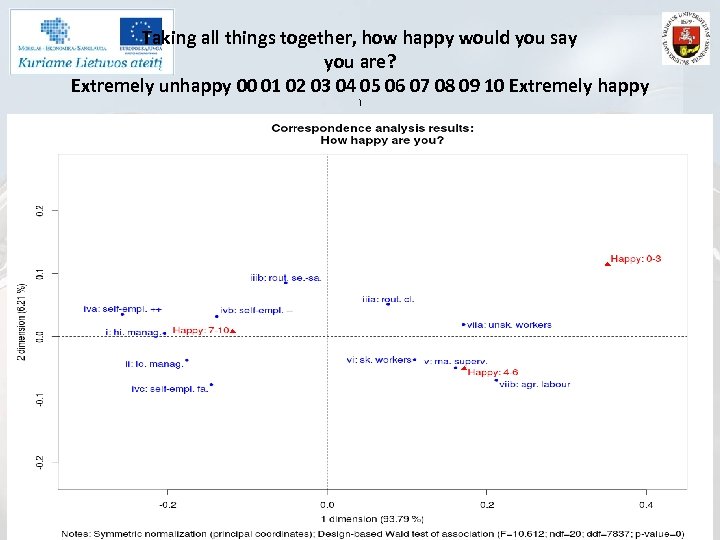

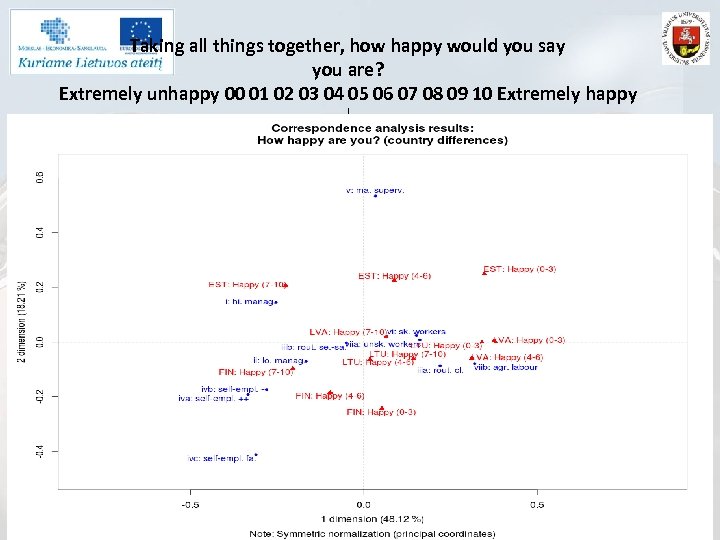

Taking all things together, how happy would you say you are? Extremely unhappy 00 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 Extremely happy )

Taking all things together, how happy would you say you are? Extremely unhappy 00 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 Extremely happy )

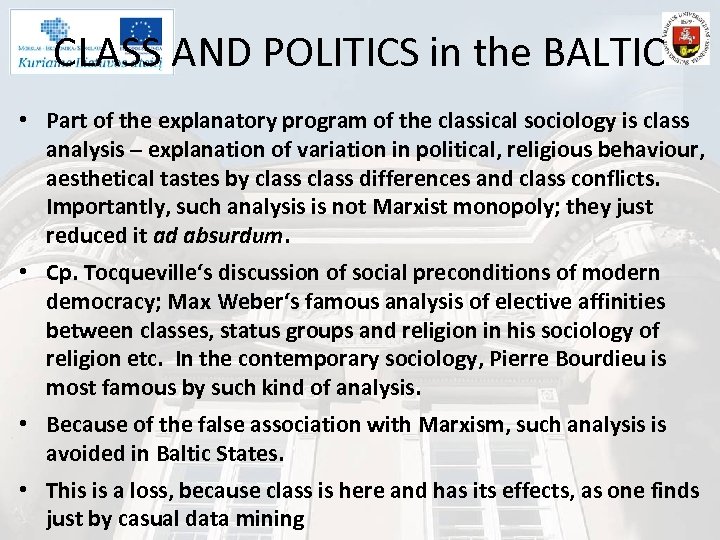

CLASS AND POLITICS in the BALTIC • Part of the explanatory program of the classical sociology is class analysis – explanation of variation in political, religious behaviour, aesthetical tastes by class differences and class conflicts. Importantly, such analysis is not Marxist monopoly; they just reduced it ad absurdum. • Cp. Tocqueville‘s discussion of social preconditions of modern democracy; Max Weber‘s famous analysis of elective affinities between classes, status groups and religion in his sociology of religion etc. In the contemporary sociology, Pierre Bourdieu is most famous by such kind of analysis. • Because of the false association with Marxism, such analysis is avoided in Baltic States. • This is a loss, because class is here and has its effects, as one finds just by casual data mining

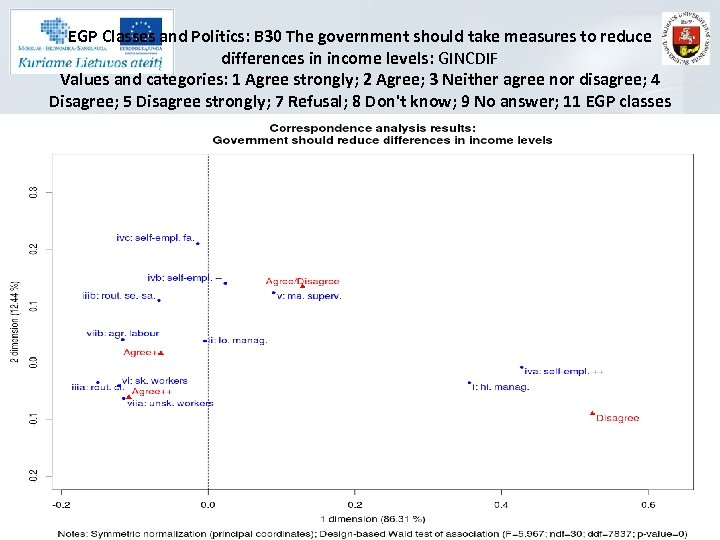

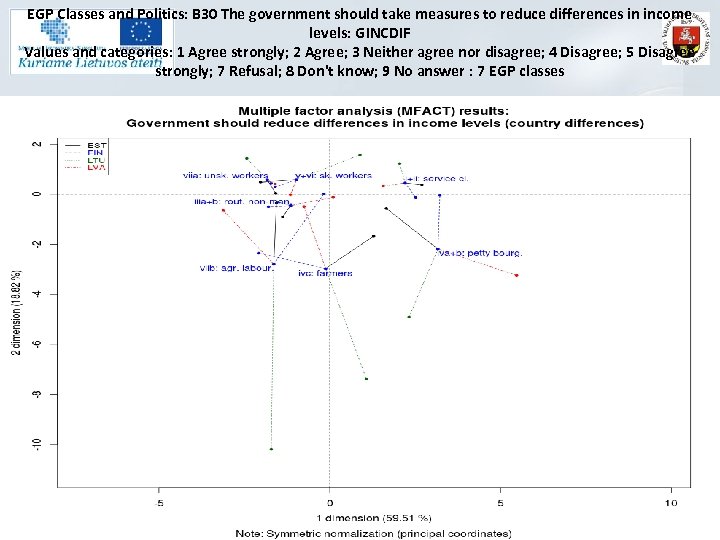

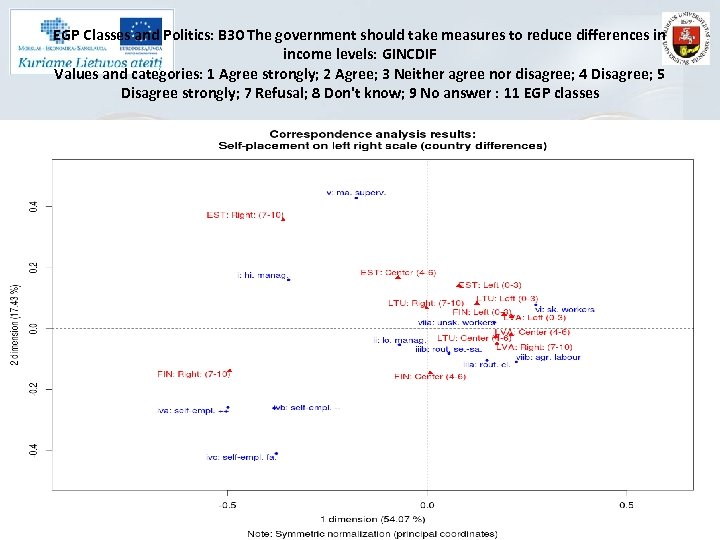

EGP Classes and Politics: B 30 The government should take measures to reduce differences in income levels: GINCDIF Values and categories: 1 Agree strongly; 2 Agree; 3 Neither agree nor disagree; 4 Disagree; 5 Disagree strongly; 7 Refusal; 8 Don't know; 9 No answer; 11 EGP classes

EGP Classes and Politics: B 30 The government should take measures to reduce differences in income levels: GINCDIF Values and categories: 1 Agree strongly; 2 Agree; 3 Neither agree nor disagree; 4 Disagree; 5 Disagree strongly; 7 Refusal; 8 Don't know; 9 No answer; 11 EGP classes

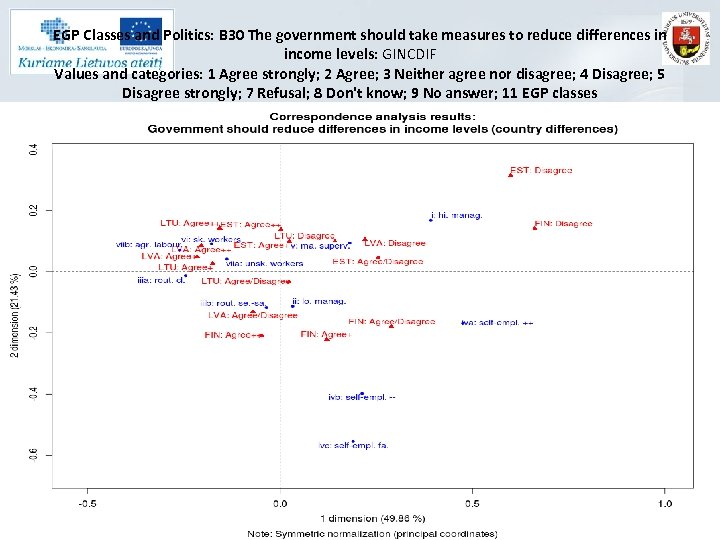

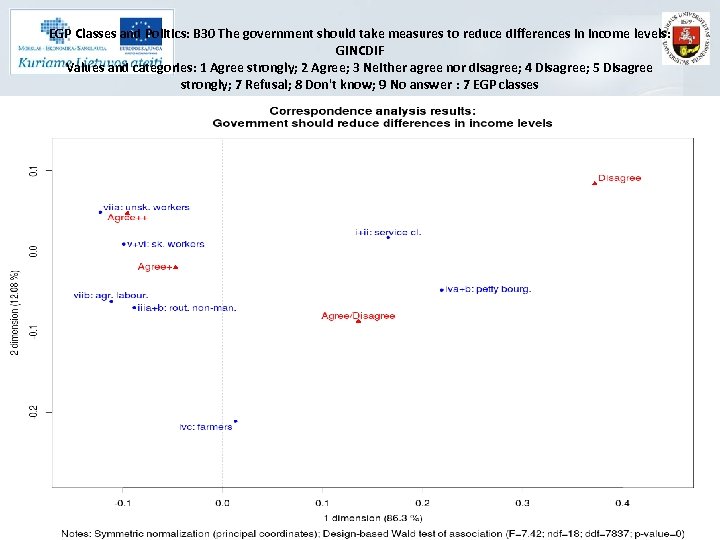

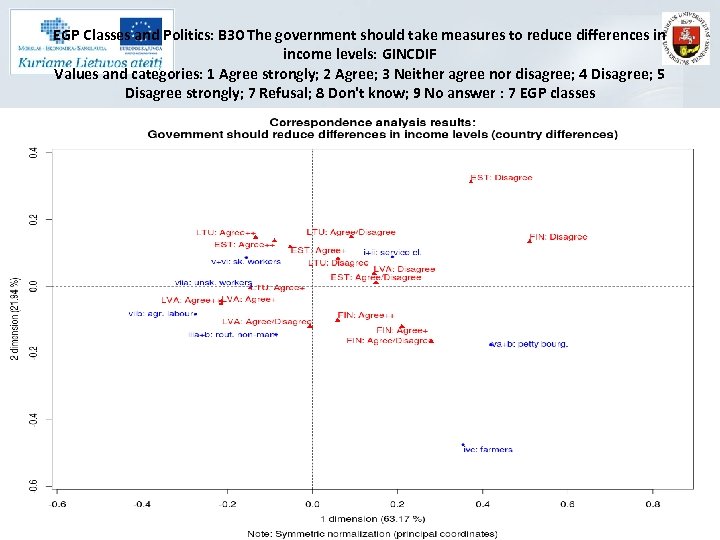

EGP Classes and Politics: B 30 The government should take measures to reduce differences in income levels: GINCDIF Values and categories: 1 Agree strongly; 2 Agree; 3 Neither agree nor disagree; 4 Disagree; 5 Disagree strongly; 7 Refusal; 8 Don't know; 9 No answer : 7 EGP classes

EGP Classes and Politics: B 30 The government should take measures to reduce differences in income levels: GINCDIF Values and categories: 1 Agree strongly; 2 Agree; 3 Neither agree nor disagree; 4 Disagree; 5 Disagree strongly; 7 Refusal; 8 Don't know; 9 No answer : 7 EGP classes

EGP Classes and Politics: B 30 The government should take measures to reduce differences in income levels: GINCDIF Values and categories: 1 Agree strongly; 2 Agree; 3 Neither agree nor disagree; 4 Disagree; 5 Disagree strongly; 7 Refusal; 8 Don't know; 9 No answer : 7 EGP classes

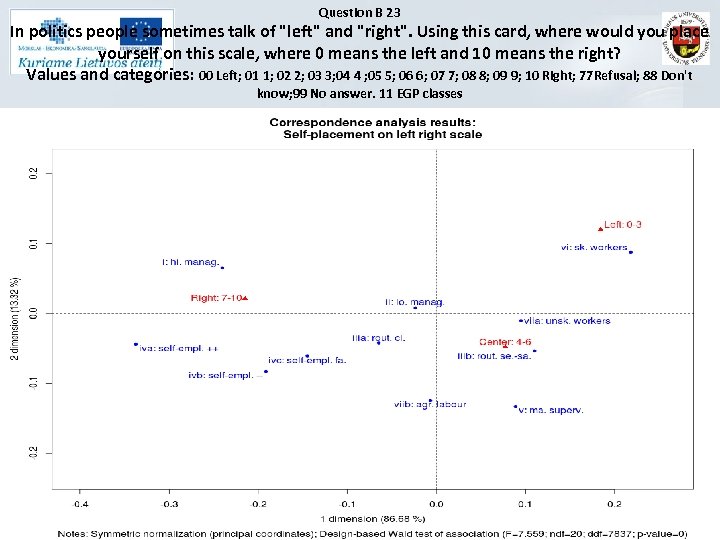

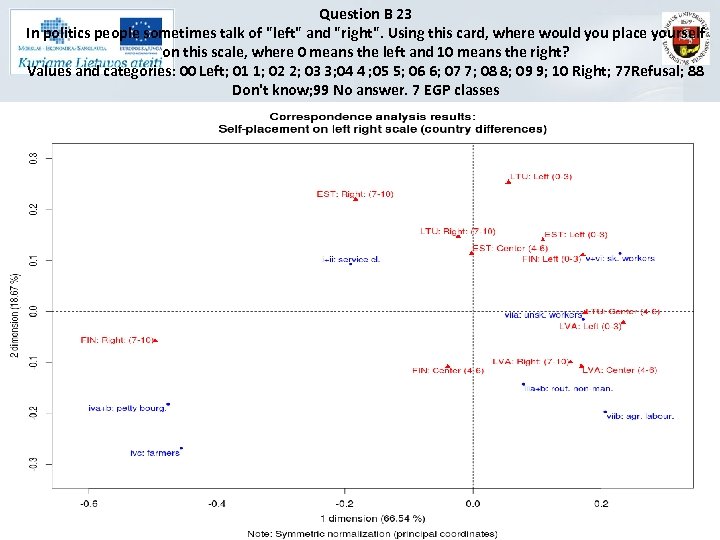

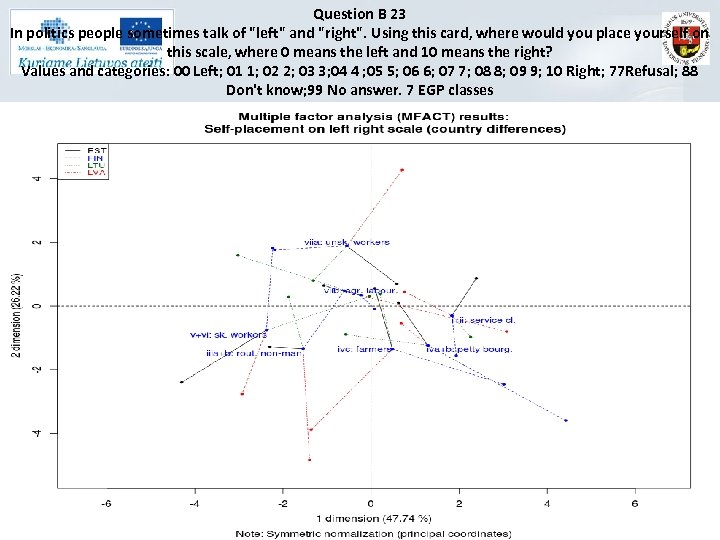

Question B 23 In politics people sometimes talk of "left" and "right". Using this card, where would you place yourself on this scale, where 0 means the left and 10 means the right? Values and categories: 00 Left; 01 1; 02 2; 03 3; 04 4 ; 05 5; 06 6; 07 7; 08 8; 09 9; 10 Right; 77 Refusal; 88 Don't know; 99 No answer. 11 EGP classes

EGP Classes and Politics: B 30 The government should take measures to reduce differences in income levels: GINCDIF Values and categories: 1 Agree strongly; 2 Agree; 3 Neither agree nor disagree; 4 Disagree; 5 Disagree strongly; 7 Refusal; 8 Don't know; 9 No answer : 11 EGP classes

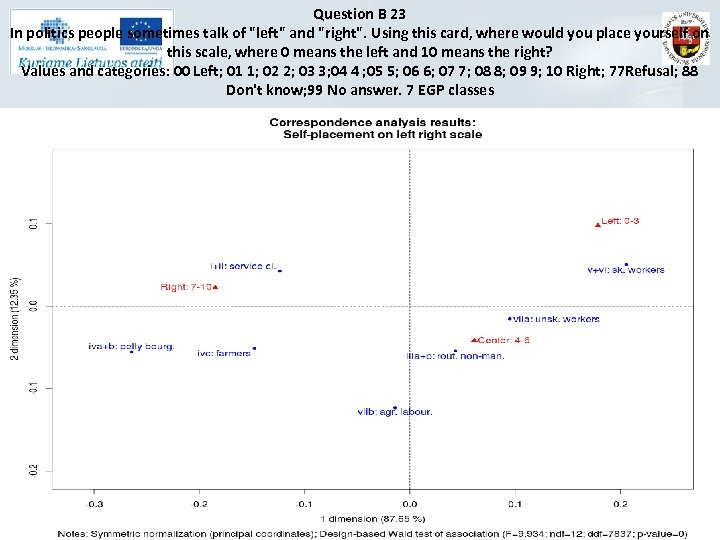

Question B 23 In politics people sometimes talk of "left" and "right". Using this card, where would you place yourself on this scale, where 0 means the left and 10 means the right? Values and categories: 00 Left; 01 1; 02 2; 03 3; 04 4 ; 05 5; 06 6; 07 7; 08 8; 09 9; 10 Right; 77 Refusal; 88 Don't know; 99 No answer. 7 EGP classes

Question B 23 In politics people sometimes talk of "left" and "right". Using this card, where would you place yourself on this scale, where 0 means the left and 10 means the right? Values and categories: 00 Left; 01 1; 02 2; 03 3; 04 4 ; 05 5; 06 6; 07 7; 08 8; 09 9; 10 Right; 77 Refusal; 88 Don't know; 99 No answer. 7 EGP classes

Question B 23 In politics people sometimes talk of "left" and "right". Using this card, where would you place yourself on this scale, where 0 means the left and 10 means the right? Values and categories: 00 Left; 01 1; 02 2; 03 3; 04 4 ; 05 5; 06 6; 07 7; 08 8; 09 9; 10 Right; 77 Refusal; 88 Don't know; 99 No answer. 7 EGP classes

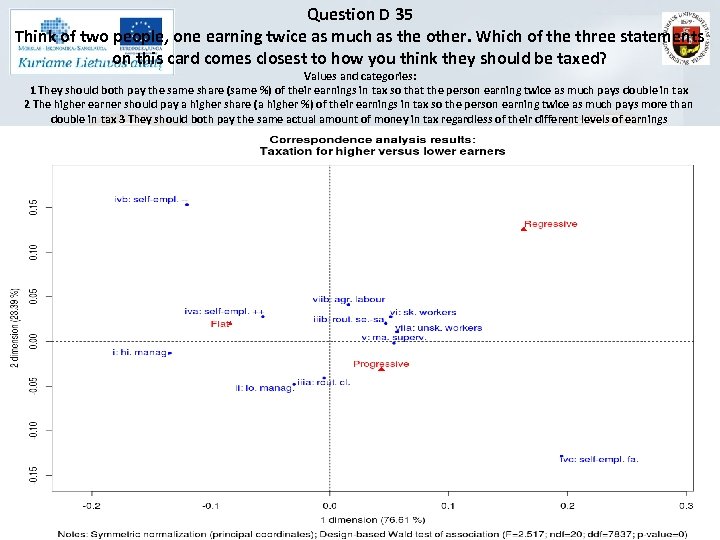

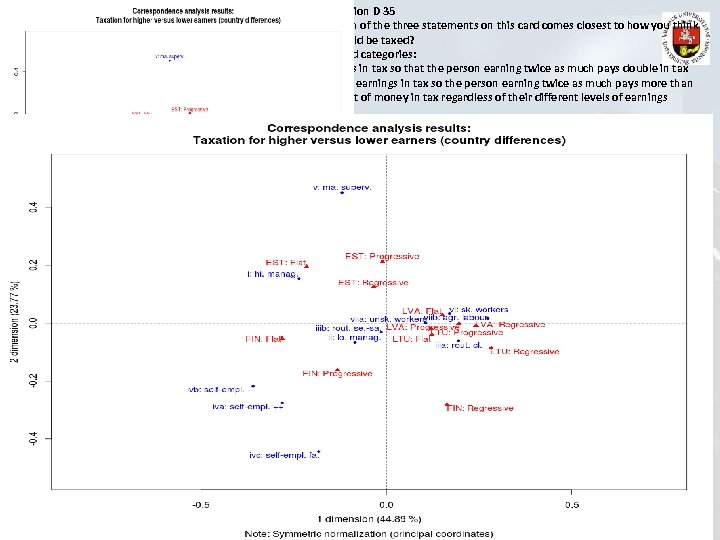

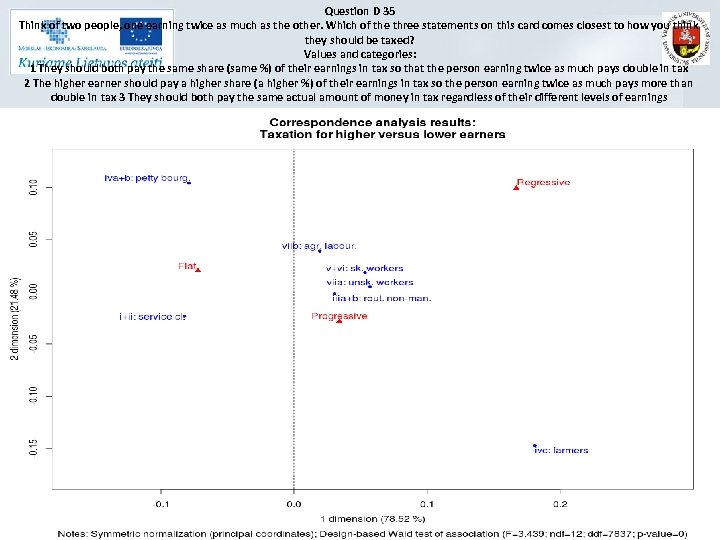

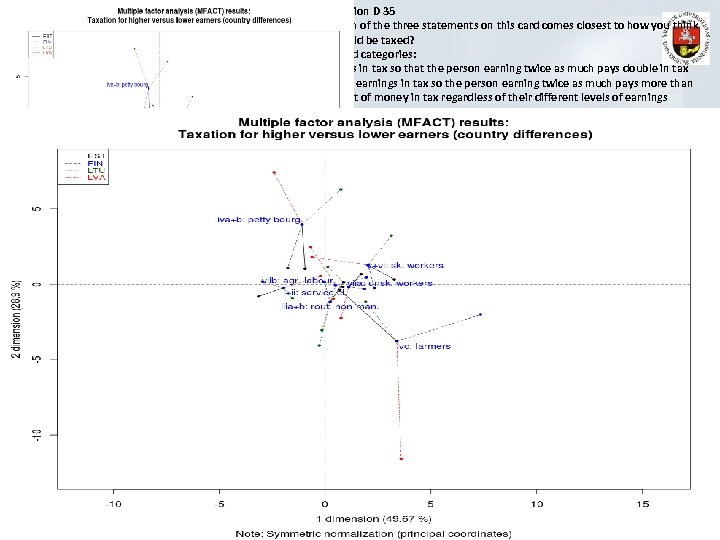

Question D 35 Think of two people, one earning twice as much as the other. Which of the three statements on this card comes closest to how you think they should be taxed? Values and categories: 1 They should both pay the same share (same %) of their earnings in tax so that the person earning twice as much pays double in tax 2 The higher earner should pay a higher share (a higher %) of their earnings in tax so the person earning twice as much pays more than double in tax 3 They should both pay the same actual amount of money in tax regardless of their different levels of earnings

Question D 35 Think of two people, one earning twice as much as the other. Which of the three statements on this card comes closest to how you think they should be taxed? Values and categories: 1 They should both pay the same share (same %) of their earnings in tax so that the person earning twice as much pays double in tax 2 The higher earner should pay a higher share (a higher %) of their earnings in tax so the person earning twice as much pays more than double in tax 3 They should both pay the same actual amount of money in tax regardless of their different levels of earnings

Question D 35 Think of two people, one earning twice as much as the other. Which of the three statements on this card comes closest to how you think they should be taxed? Values and categories: 1 They should both pay the same share (same %) of their earnings in tax so that the person earning twice as much pays double in tax 2 The higher earner should pay a higher share (a higher %) of their earnings in tax so the person earning twice as much pays more than double in tax 3 They should both pay the same actual amount of money in tax regardless of their different levels of earnings

Question D 35 Think of two people, one earning twice as much as the other. Which of the three statements on this card comes closest to how you think they should be taxed? Values and categories: 1 They should both pay the same share (same %) of their earnings in tax so that the person earning twice as much pays double in tax 2 The higher earner should pay a higher share (a higher %) of their earnings in tax so the person earning twice as much pays more than double in tax 3 They should both pay the same actual amount of money in tax regardless of their different levels of earnings

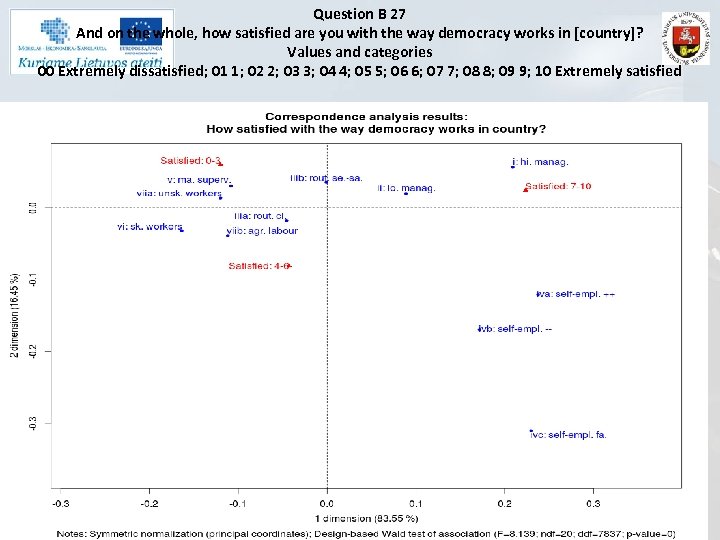

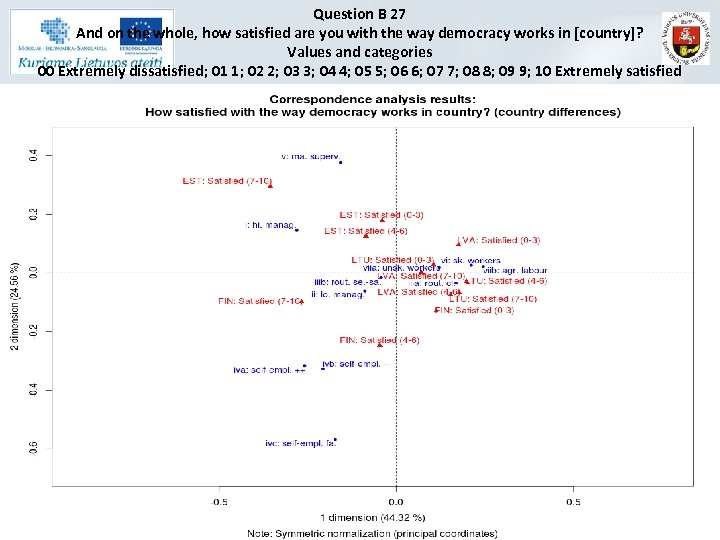

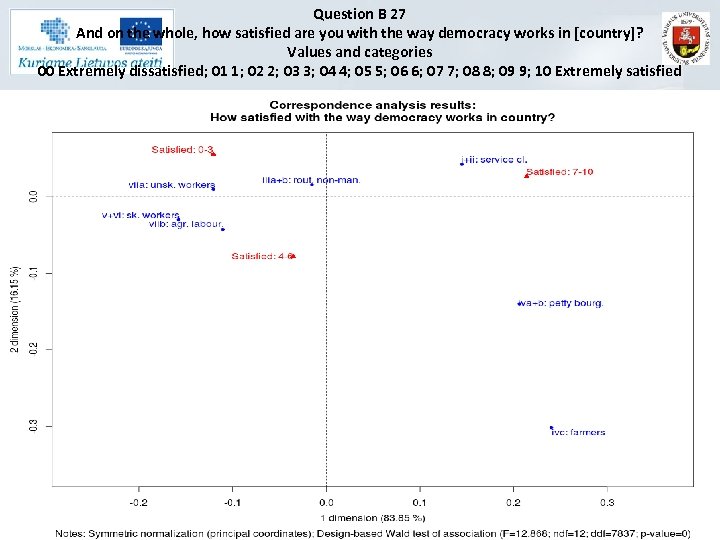

Question B 27 And on the whole, how satisfied are you with the way democracy works in [country]? Values and categories 00 Extremely dissatisfied; 01 1; 02 2; 03 3; 04 4; 05 5; 06 6; 07 7; 08 8; 09 9; 10 Extremely satisfied

Question B 27 And on the whole, how satisfied are you with the way democracy works in [country]? Values and categories 00 Extremely dissatisfied; 01 1; 02 2; 03 3; 04 4; 05 5; 06 6; 07 7; 08 8; 09 9; 10 Extremely satisfied

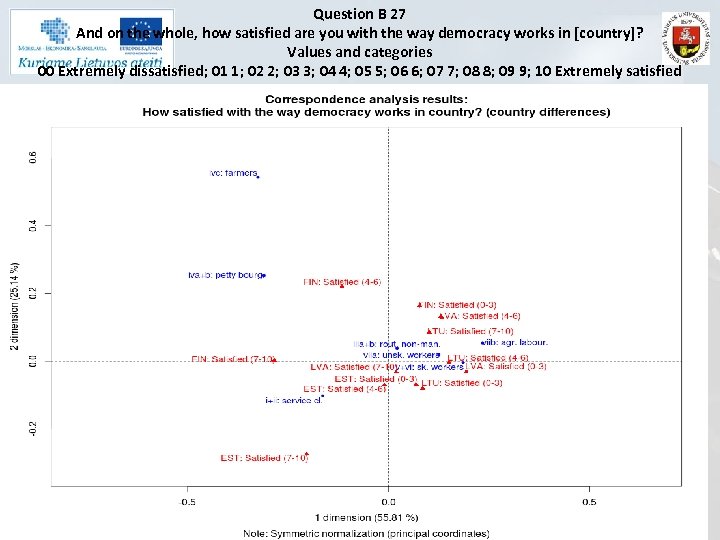

Question B 27 And on the whole, how satisfied are you with the way democracy works in [country]? Values and categories 00 Extremely dissatisfied; 01 1; 02 2; 03 3; 04 4; 05 5; 06 6; 07 7; 08 8; 09 9; 10 Extremely satisfied

Question B 27 And on the whole, how satisfied are you with the way democracy works in [country]? Values and categories 00 Extremely dissatisfied; 01 1; 02 2; 03 3; 04 4; 05 5; 06 6; 07 7; 08 8; 09 9; 10 Extremely satisfied

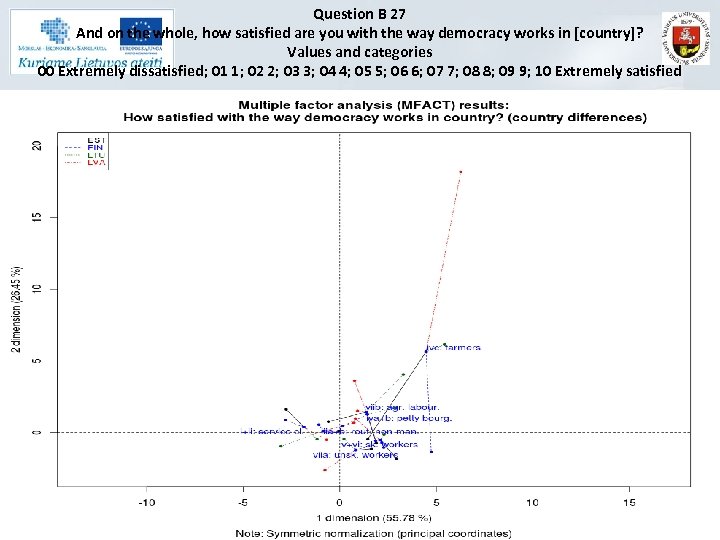

Question B 27 And on the whole, how satisfied are you with the way democracy works in [country]? Values and categories 00 Extremely dissatisfied; 01 1; 02 2; 03 3; 04 4; 05 5; 06 6; 07 7; 08 8; 09 9; 10 Extremely satisfied

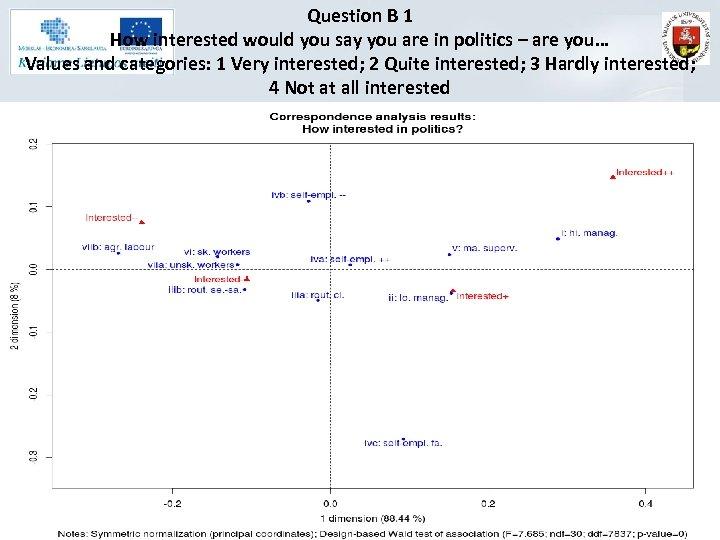

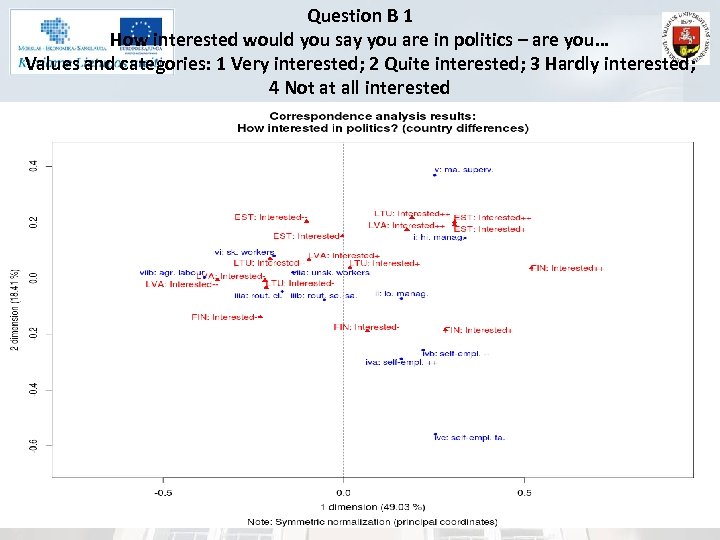

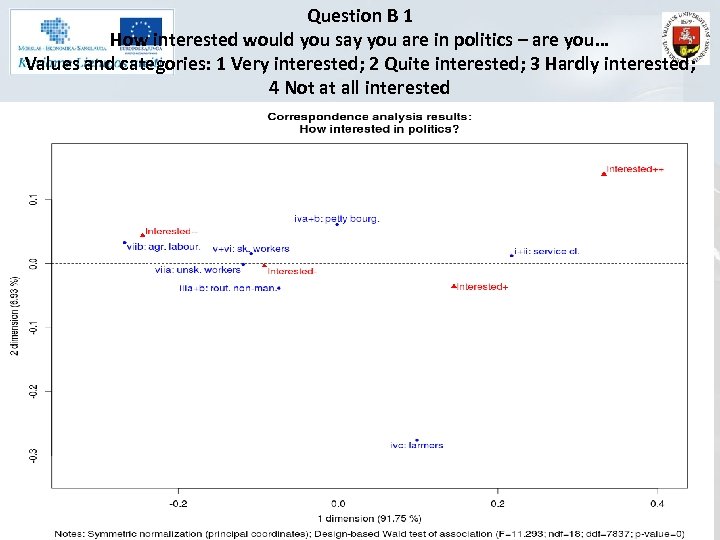

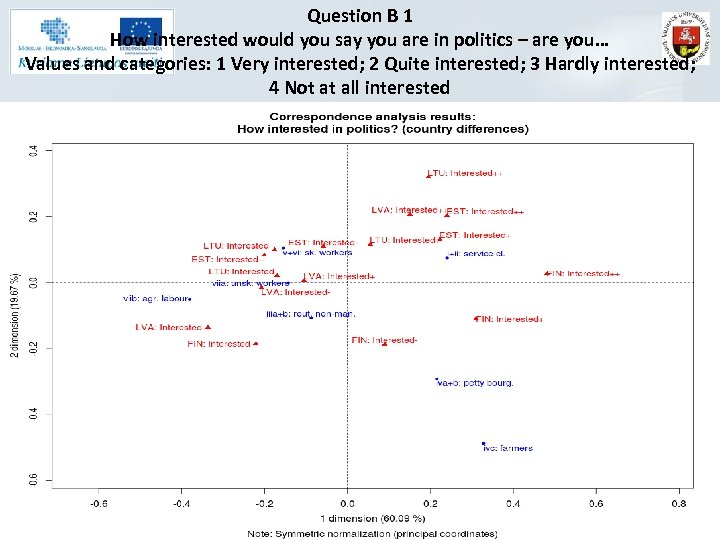

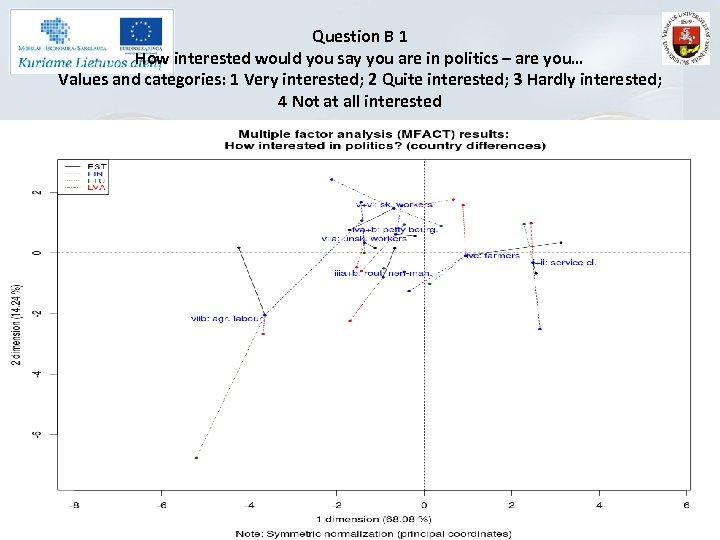

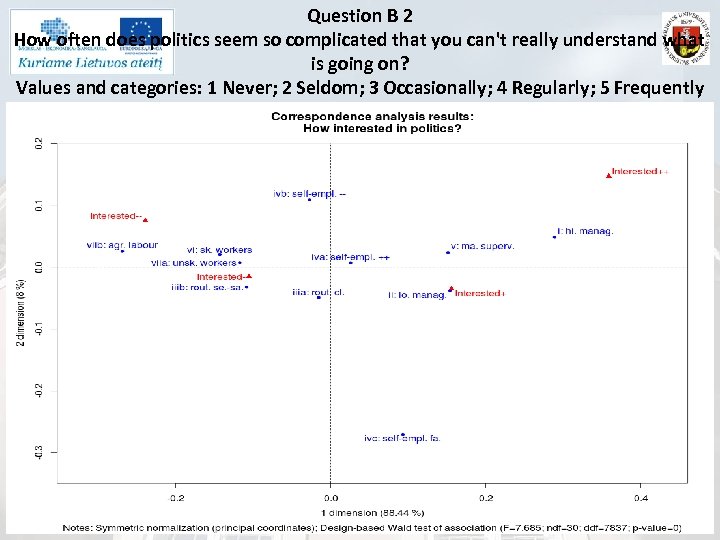

Question B 1 How interested would you say you are in politics – are you… Values and categories: 1 Very interested; 2 Quite interested; 3 Hardly interested; 4 Not at all interested

Question B 1 How interested would you say you are in politics – are you… Values and categories: 1 Very interested; 2 Quite interested; 3 Hardly interested; 4 Not at all interested

Question B 1 How interested would you say you are in politics – are you… Values and categories: 1 Very interested; 2 Quite interested; 3 Hardly interested; 4 Not at all interested

Question B 1 How interested would you say you are in politics – are you… Values and categories: 1 Very interested; 2 Quite interested; 3 Hardly interested; 4 Not at all interested

Question B 1 How interested would you say you are in politics – are you… Values and categories: 1 Very interested; 2 Quite interested; 3 Hardly interested; 4 Not at all interested

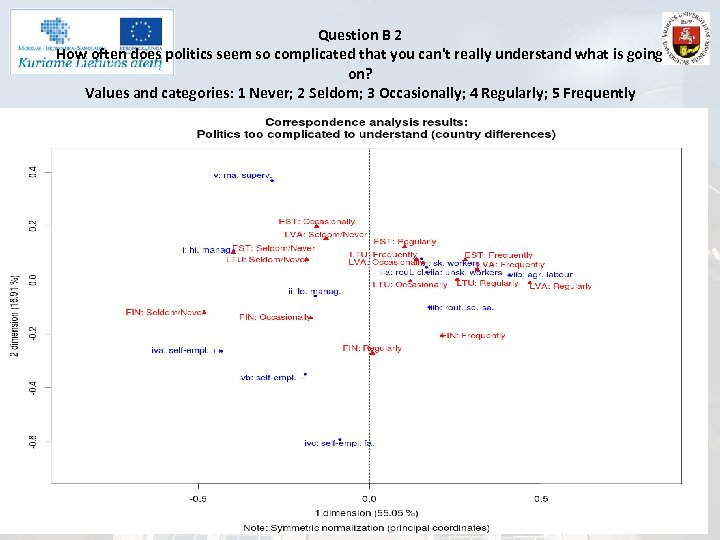

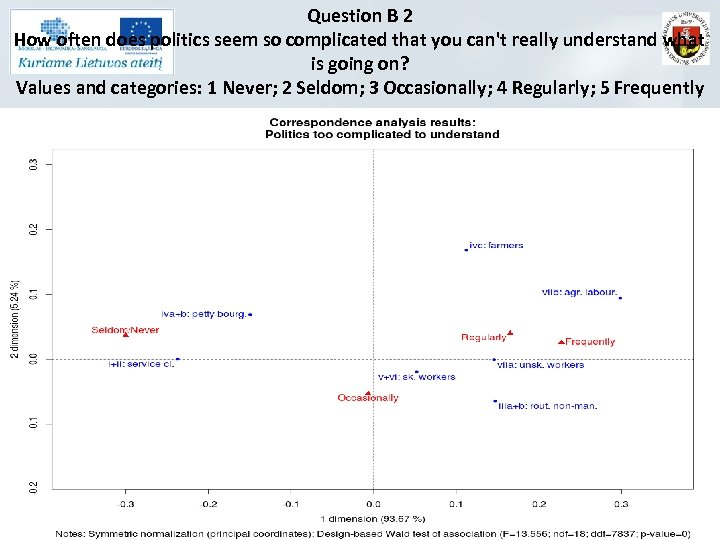

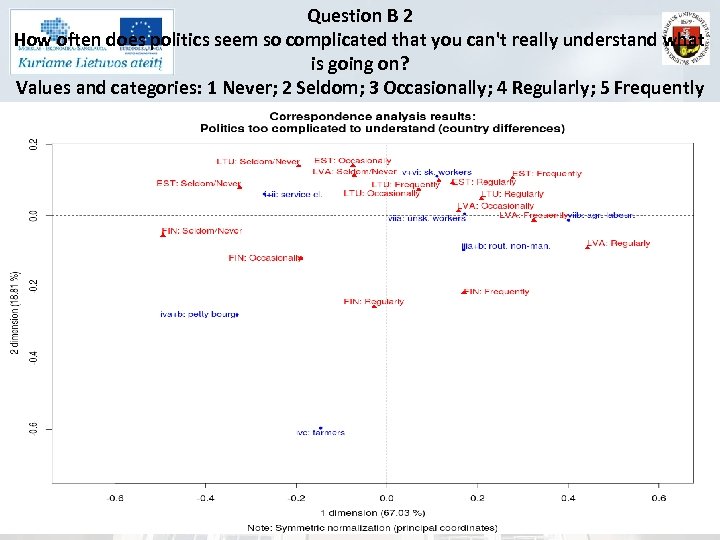

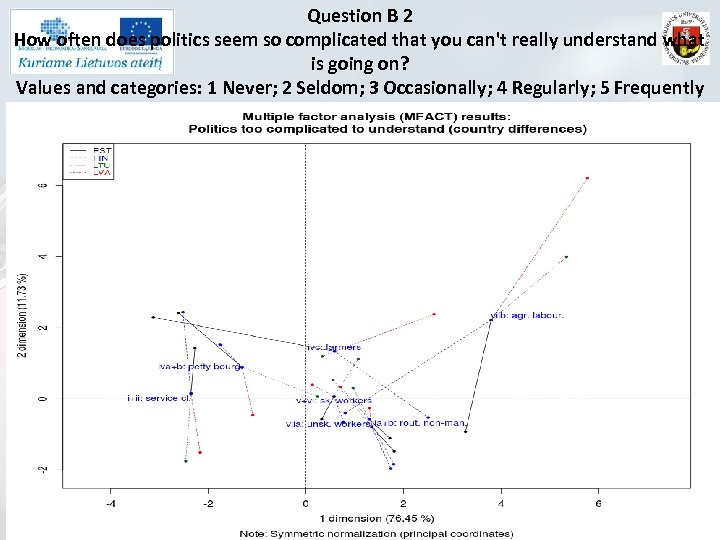

Question B 2 How often does politics seem so complicated that you can't really understand what is going on? Values and categories: 1 Never; 2 Seldom; 3 Occasionally; 4 Regularly; 5 Frequently

Question B 2 How often does politics seem so complicated that you can't really understand what is going on? Values and categories: 1 Never; 2 Seldom; 3 Occasionally; 4 Regularly; 5 Frequently

Question B 2 How often does politics seem so complicated that you can't really understand what is going on? Values and categories: 1 Never; 2 Seldom; 3 Occasionally; 4 Regularly; 5 Frequently

Question B 2 How often does politics seem so complicated that you can't really understand what is going on? Values and categories: 1 Never; 2 Seldom; 3 Occasionally; 4 Regularly; 5 Frequently

Question B 2 How often does politics seem so complicated that you can't really understand what is going on? Values and categories: 1 Never; 2 Seldom; 3 Occasionally; 4 Regularly; 5 Frequently

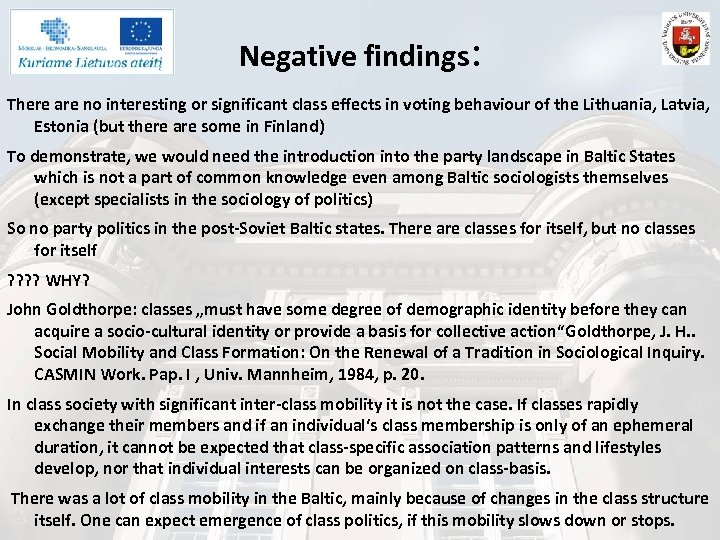

Negative findings: There are no interesting or significant class effects in voting behaviour of the Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia (but there are some in Finland) To demonstrate, we would need the introduction into the party landscape in Baltic States which is not a part of common knowledge even among Baltic sociologists themselves (except specialists in the sociology of politics) So no party politics in the post-Soviet Baltic states. There are classes for itself, but no classes for itself ? ? WHY? John Goldthorpe: classes „must have some degree of demographic identity before they can acquire a socio-cultural identity or provide a basis for collective action“Goldthorpe, J. H. . Social Mobility and Class Formation: On the Renewal of a Tradition in Sociological Inquiry. CASMIN Work. Pap. I , Univ. Mannheim, 1984, p. 20. In class society with significant inter-class mobility it is not the case. If classes rapidly exchange their members and if an individual‘s class membership is only of an ephemeral duration, it cannot be expected that class-specific association patterns and lifestyles develop, nor that individual interests can be organized on class-basis. There was a lot of class mobility in the Baltic, mainly because of changes in the class structure itself. One can expect emergence of class politics, if this mobility slows down or stops.

f257353320a095abf7ba1dae54c53dda.ppt