ced0e6afc6bedd611ed67f5586450c8b.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 128

Class 7_Aug 2 nd Pricing Strategy: Developing Pricing Strategies and Programs (Ch 12) To accompany A Framework for Marketing 1 Management, 5 E by Kotler © Jihye Lee

Class 7_Aug 2 nd Pricing Strategy: Developing Pricing Strategies and Programs (Ch 12) To accompany A Framework for Marketing 1 Management, 5 E by Kotler © Jihye Lee

Pricing Strategies

Pricing Strategies

4 P’s Product • • • Place Quality • Style Features • Options Brand name • Packaging Guarantees/warranties Services/spare parts • Numbers and types of middlemen • Locations/availability • Inventory levels • Transportation The target market Price • Discounts • Allowances • Credit terms • Payment period • Rental/lease • List price Promotion • • • Advertising Personal selling Sales promotion Point-of-purchase materials Publicity The marketing mix is the combination of controllable marketing variables that a manager uses to carry out a marketing strategy in pursuit of the firm’s objectives in a given target market.

4 P’s Product • • • Place Quality • Style Features • Options Brand name • Packaging Guarantees/warranties Services/spare parts • Numbers and types of middlemen • Locations/availability • Inventory levels • Transportation The target market Price • Discounts • Allowances • Credit terms • Payment period • Rental/lease • List price Promotion • • • Advertising Personal selling Sales promotion Point-of-purchase materials Publicity The marketing mix is the combination of controllable marketing variables that a manager uses to carry out a marketing strategy in pursuit of the firm’s objectives in a given target market.

What We Want to Learn • How do consumers process and evaluate prices? • How should a company set prices initially for products or services? • How should a company adapt prices to meet varying circumstances and opportunities? • When should a company initiate a price change? • How should a company respond to a competitor’s price challenge?

What We Want to Learn • How do consumers process and evaluate prices? • How should a company set prices initially for products or services? • How should a company adapt prices to meet varying circumstances and opportunities? • When should a company initiate a price change? • How should a company respond to a competitor’s price challenge?

Tiffany • What do you think about Tiffany’s price? • Start with “ affordable luxuries” – creating a line of cheaper silver jewelry ü Return to Tiffany” silver bracelet became a must-have item for teens • Affordable jewelry brought an image and pricing crisis for company To accompany A Framework for Marketing 5 Management, 5 E by Kotler © Jihye Lee

Tiffany • What do you think about Tiffany’s price? • Start with “ affordable luxuries” – creating a line of cheaper silver jewelry ü Return to Tiffany” silver bracelet became a must-have item for teens • Affordable jewelry brought an image and pricing crisis for company To accompany A Framework for Marketing 5 Management, 5 E by Kotler © Jihye Lee

Tiffany • Starting in 2002, the company began hiking prices again. • At the same time, it launched higher-end collections renovated stores to feature expensive items appealing to mature buyers and expanded aggressively into new cities and shopping malls. To accompany A Framework for Marketing 6 Management, 5 E by Kotler © Jihye Lee

Tiffany • Starting in 2002, the company began hiking prices again. • At the same time, it launched higher-end collections renovated stores to feature expensive items appealing to mature buyers and expanded aggressively into new cities and shopping malls. To accompany A Framework for Marketing 6 Management, 5 E by Kotler © Jihye Lee

Tiffany • Recession began in 2008, the company knew it had to be careful not to dilute its high-end appeal • Tiffany offset softer sales largely with costcutting and inventory management, and very quietly lowered prices on best-selling engagement by 10 percent To accompany A Framework for Marketing 7 Management, 5 E by Kotler © Jihye Lee

Tiffany • Recession began in 2008, the company knew it had to be careful not to dilute its high-end appeal • Tiffany offset softer sales largely with costcutting and inventory management, and very quietly lowered prices on best-selling engagement by 10 percent To accompany A Framework for Marketing 7 Management, 5 E by Kotler © Jihye Lee

What do we learn from Tiffany case? • Holistic marketers must take into account many factors in making pricing decisions- the company, the customers, the competition, and the marketing environment. • Pricing decisions must be consistent with the firm’s marketing strategy and its target markets and brand positioning. To accompany A Framework for Marketing 8 Management, 5 E by Kotler © Jihye Lee

What do we learn from Tiffany case? • Holistic marketers must take into account many factors in making pricing decisions- the company, the customers, the competition, and the marketing environment. • Pricing decisions must be consistent with the firm’s marketing strategy and its target markets and brand positioning. To accompany A Framework for Marketing 8 Management, 5 E by Kotler © Jihye Lee

What do you think about price? • Price is the one element of the marketing mix that produces revenue; the other elements produce costs. • Prices are perhaps the easiest element of the market program to adjust; product features, channels, and even communications take more time. • Price also communicates to the market the company’s intended value positioning of its product or brand. 9

What do you think about price? • Price is the one element of the marketing mix that produces revenue; the other elements produce costs. • Prices are perhaps the easiest element of the market program to adjust; product features, channels, and even communications take more time. • Price also communicates to the market the company’s intended value positioning of its product or brand. 9

Case: Ryanair • European destination only • No frills on aircraft • No complimentary food/drink • Ancillary revenue: Revenue from non-ticket sources, such as baggage fees and on-board food and services, and has become an important financial component for low-cost carriers (LCCs) in Europe, the United States and other global regions 10

Case: Ryanair • European destination only • No frills on aircraft • No complimentary food/drink • Ancillary revenue: Revenue from non-ticket sources, such as baggage fees and on-board food and services, and has become an important financial component for low-cost carriers (LCCs) in Europe, the United States and other global regions 10

Case: Ryanair - Price • A quarter of Ryanair’s seats are free. Passengers currently pay only taxes and fees of about $10 to $24, with an average one-way fare of roughly $52 • Passengers pay extra for everything else: for checked luggage, snacks, and bus or train transportation 11

Case: Ryanair - Price • A quarter of Ryanair’s seats are free. Passengers currently pay only taxes and fees of about $10 to $24, with an average one-way fare of roughly $52 • Passengers pay extra for everything else: for checked luggage, snacks, and bus or train transportation 11

Case: Ryanair - Price • 70 % tickets sold at the lowest far • 30% tickets sold at the higher fare • 6% tickets sold at the highest fare 12

Case: Ryanair - Price • 70 % tickets sold at the lowest far • 30% tickets sold at the higher fare • 6% tickets sold at the highest fare 12

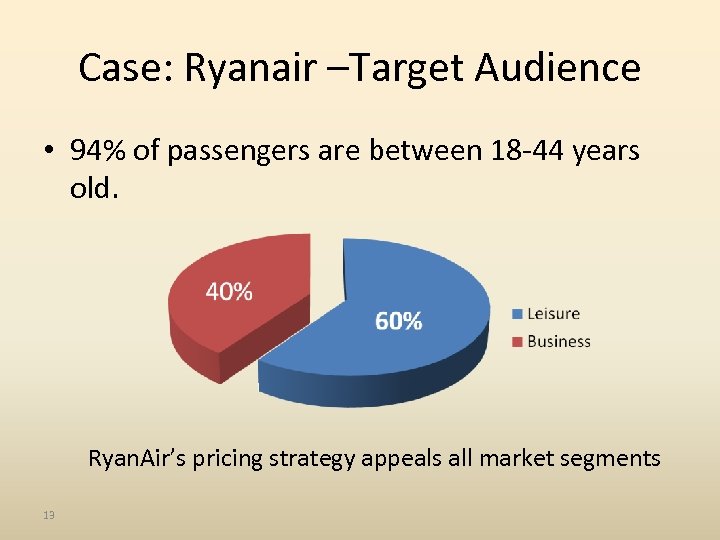

Case: Ryanair –Target Audience • 94% of passengers are between 18 -44 years old. Ryan. Air’s pricing strategy appeals all market segments 13

Case: Ryanair –Target Audience • 94% of passengers are between 18 -44 years old. Ryan. Air’s pricing strategy appeals all market segments 13

Case study-Ryan. Air To accompany A Framework for Marketing 14 Management, 5 E by Kotler © Jihye Lee

Case study-Ryan. Air To accompany A Framework for Marketing 14 Management, 5 E by Kotler © Jihye Lee

Pricing Strategies • • 15 Understanding the Pricing Setting the Price Adapting the Price Initiating and Responding to Price Changes

Pricing Strategies • • 15 Understanding the Pricing Setting the Price Adapting the Price Initiating and Responding to Price Changes

Understanding the Pricing • A changing pricing environment Ø During the recent recession Ø Economic environment affects Ø Advent of Internet Ø How to compete with free products • Consumer psychology and pricing 16

Understanding the Pricing • A changing pricing environment Ø During the recent recession Ø Economic environment affects Ø Advent of Internet Ø How to compete with free products • Consumer psychology and pricing 16

A Changing Pricing Environment • Buyers can: • (1) Get instant price comparisons from thousands of vendors (Biz. Rate. com) • (2) Name their price and have it met (e. g. priceline. com, e. Bay) • (3) Get products free (open source: Linux, challenge confronting MS, Oracle, IBM) 17

A Changing Pricing Environment • Buyers can: • (1) Get instant price comparisons from thousands of vendors (Biz. Rate. com) • (2) Name their price and have it met (e. g. priceline. com, e. Bay) • (3) Get products free (open source: Linux, challenge confronting MS, Oracle, IBM) 17

A Changing Pricing Environment (cont. ) • Sellers can: • (1) Monitor customer behavior and tailor offers to individuals • (2) Give certain customers access to special prices (Beyond Rack. com, Sephora-member of beauty insider) • (3) Negotiate prices in online auctions and exchanges (ebay. com. /baseballplanet. com- baseball cards at bargain price) 18

A Changing Pricing Environment (cont. ) • Sellers can: • (1) Monitor customer behavior and tailor offers to individuals • (2) Give certain customers access to special prices (Beyond Rack. com, Sephora-member of beauty insider) • (3) Negotiate prices in online auctions and exchanges (ebay. com. /baseballplanet. com- baseball cards at bargain price) 18

Common Pricing Mistakes • Determine costs and take traditional industry margins • Failure to revise price to capitalize on market changes • Setting price independently of the rest of the marketing mix • Failure to vary price by product item, market segment, distribution channels, and purchase occasion

Common Pricing Mistakes • Determine costs and take traditional industry margins • Failure to revise price to capitalize on market changes • Setting price independently of the rest of the marketing mix • Failure to vary price by product item, market segment, distribution channels, and purchase occasion

Consumer Psychology and Pricing • Purchase decisions are based on how consumers perceived prices and what they consider the current actual price to be – not on the marketer’s stated price. To accompany A Framework for Marketing 20 Management, 5 E by Kotler © Jihye Lee

Consumer Psychology and Pricing • Purchase decisions are based on how consumers perceived prices and what they consider the current actual price to be – not on the marketer’s stated price. To accompany A Framework for Marketing 20 Management, 5 E by Kotler © Jihye Lee

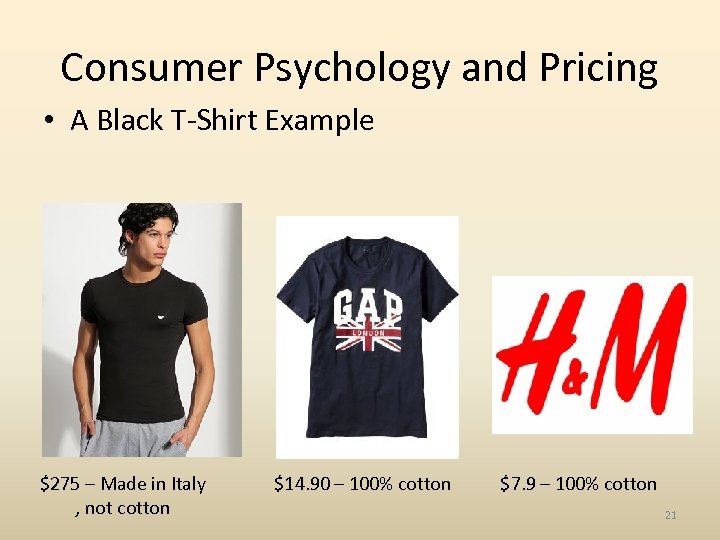

Consumer Psychology and Pricing • A Black T-Shirt Example $275 – Made in Italy , not cotton $14. 90 – 100% cotton $7. 9 – 100% cotton 21

Consumer Psychology and Pricing • A Black T-Shirt Example $275 – Made in Italy , not cotton $14. 90 – 100% cotton $7. 9 – 100% cotton 21

Consumer Psychology and Pricing Reference Prices Price-quality inferences Price endings

Consumer Psychology and Pricing Reference Prices Price-quality inferences Price endings

Possible Consumer Reference Prices Consumers often employ reference prices, comparing an observed price to an internal reference price they remember or an external frame of reference such as a posted “regular retail price” • “Fair price”(what consumers feel the product should cost) • Typical price • Last price paid • Historical Competitor prices • Expected future price • Usual discounted price • Upper-bound price(reservation price or the maximum most consumers would pay) • Lower-bound price(lower threshold price or the minimum most consumer would pay)

Possible Consumer Reference Prices Consumers often employ reference prices, comparing an observed price to an internal reference price they remember or an external frame of reference such as a posted “regular retail price” • “Fair price”(what consumers feel the product should cost) • Typical price • Last price paid • Historical Competitor prices • Expected future price • Usual discounted price • Upper-bound price(reservation price or the maximum most consumers would pay) • Lower-bound price(lower threshold price or the minimum most consumer would pay)

Reference Prices • Internal reference price : customer they remember • External reference price : what they see “regular retail price” 24

Reference Prices • Internal reference price : customer they remember • External reference price : what they see “regular retail price” 24

Ex: Suggested Retail Price 25

Ex: Suggested Retail Price 25

Ex: Smaller Units of Prices • If the price is broken down into smaller units, the product may look less expensive. • Ex: A $500 annual membership may look more expensive than “under $50 a month” even if the totals are the same. 26

Ex: Smaller Units of Prices • If the price is broken down into smaller units, the product may look less expensive. • Ex: A $500 annual membership may look more expensive than “under $50 a month” even if the totals are the same. 26

Price-Quality Inference • Many consumers use price as an indicator of quality. • Image pricing is especially effective with egosensitive products such as perfumes, expensive cars and designer clothing, etc. 27

Price-Quality Inference • Many consumers use price as an indicator of quality. • Image pricing is especially effective with egosensitive products such as perfumes, expensive cars and designer clothing, etc. 27

Price-Quality Inference (cont. ) • Price and quality perceptions of products (e. g. cars) interact. • Higher-priced cars are perceived to possess high quality. Higher-quality cars are likewise perceived to be higher priced than they actually are. 28

Price-Quality Inference (cont. ) • Price and quality perceptions of products (e. g. cars) interact. • Higher-priced cars are perceived to possess high quality. Higher-quality cars are likewise perceived to be higher priced than they actually are. 28

Perfume and designer clothing : price-quality inferences Do you think that it really worthy to pay $100 bottle of perfume? For luxury goods customers demand may actually increases price, because they then believe fewer other customers can afford the product

Perfume and designer clothing : price-quality inferences Do you think that it really worthy to pay $100 bottle of perfume? For luxury goods customers demand may actually increases price, because they then believe fewer other customers can afford the product

Price Endings • Consumers see an item priced at $299 as being in the $200 rather than the $300 range; they tend to process prices “left-to-right” rather than by rounding. • Price ending in odd numbers suggest a discount or bargain. A product priced at $2. 99 can be perceived as distinctly less expensive than one priced at $3. 00 30

Price Endings • Consumers see an item priced at $299 as being in the $200 rather than the $300 range; they tend to process prices “left-to-right” rather than by rounding. • Price ending in odd numbers suggest a discount or bargain. A product priced at $2. 99 can be perceived as distinctly less expensive than one priced at $3. 00 30

Pricing Strategies • • 31 Understanding the Pricing Setting the Price Adapting the Price Initiating and Responding to Price Changes

Pricing Strategies • • 31 Understanding the Pricing Setting the Price Adapting the Price Initiating and Responding to Price Changes

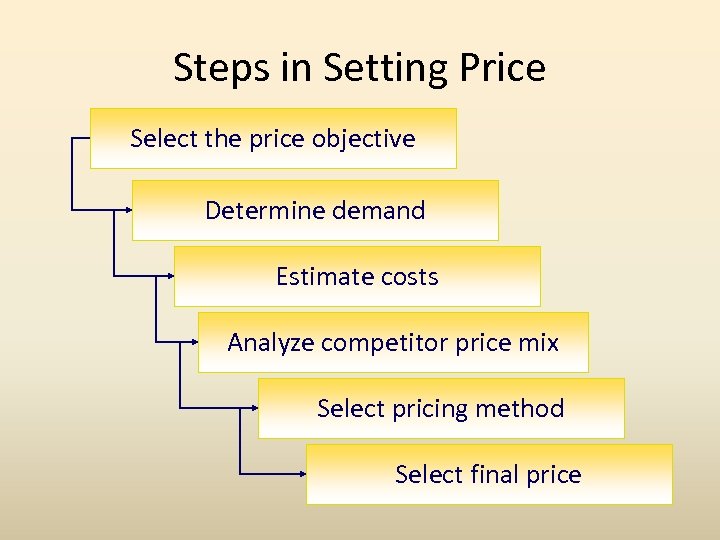

Steps in Setting Price Select the price objective Determine demand Estimate costs Analyze competitor price mix Select pricing method Select final price

Steps in Setting Price Select the price objective Determine demand Estimate costs Analyze competitor price mix Select pricing method Select final price

Step 1: Selecting the Pricing Objective • Survival (short term objective) • Maximum current profit(profits, cash flow, rate of return on investment) • Maximum market share (companies believe a higher sales volume will lead to lower unit costs and higher long-run profit)

Step 1: Selecting the Pricing Objective • Survival (short term objective) • Maximum current profit(profits, cash flow, rate of return on investment) • Maximum market share (companies believe a higher sales volume will lead to lower unit costs and higher long-run profit)

Step 1: Selecting the Pricing Objective • Maximum market skimming: new technology favor setting high prices to maximize • Product-quality leadership: affordable luxuries: e. g. Aveda, Starbuck, VS – quality Apple created an uproar among its leaders in their early-adopter customers when it categories significantly lowered the price of its i. Phone after only two months Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Prentice Hall 14 -34

Step 1: Selecting the Pricing Objective • Maximum market skimming: new technology favor setting high prices to maximize • Product-quality leadership: affordable luxuries: e. g. Aveda, Starbuck, VS – quality Apple created an uproar among its leaders in their early-adopter customers when it categories significantly lowered the price of its i. Phone after only two months Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Prentice Hall 14 -34

Step 2: Determining demand • What is the relationship between demand price? • Normally inverse (figure in pg. 37) • The higher the price, the lower the demand. • However, prestige goods, the demand curve sometimes lopes upward. e. g. , when perfume prices increased, sold more rather than less. Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Prentice Hall 14 -35

Step 2: Determining demand • What is the relationship between demand price? • Normally inverse (figure in pg. 37) • The higher the price, the lower the demand. • However, prestige goods, the demand curve sometimes lopes upward. e. g. , when perfume prices increased, sold more rather than less. Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Publishing as Prentice Hall 14 -35

Step 2: Determining Demand Price Sensitivity Estimating Demand Curves

Step 2: Determining Demand Price Sensitivity Estimating Demand Curves

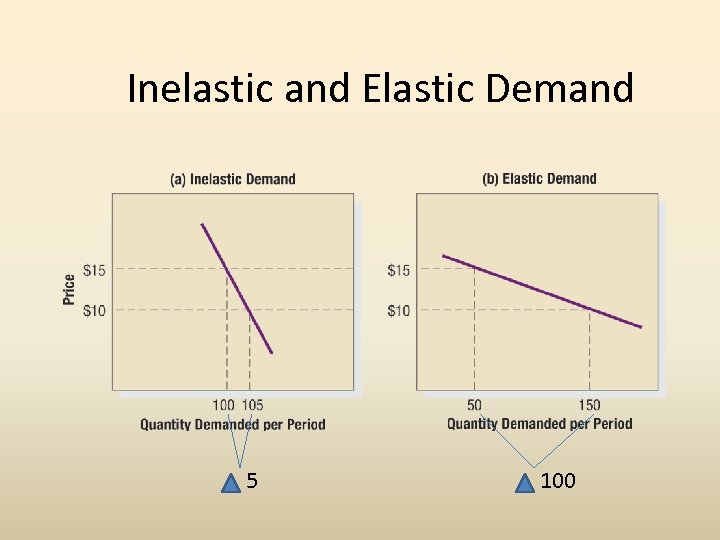

Inelastic and Elastic Demand (cont. ) • Price elasticity of demand ØInelastic—small change in demand with small change in price. ØElastic—considerable change in demand with small change in price. 37

Inelastic and Elastic Demand (cont. ) • Price elasticity of demand ØInelastic—small change in demand with small change in price. ØElastic—considerable change in demand with small change in price. 37

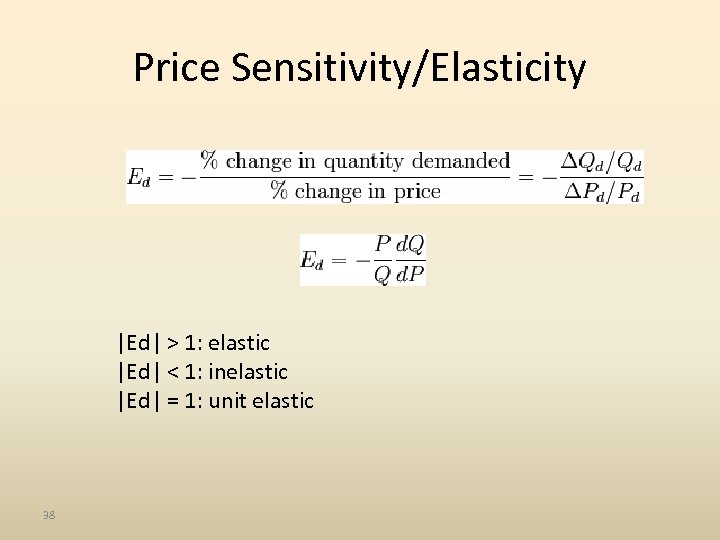

Price Sensitivity/Elasticity |Ed| > 1: elastic |Ed| < 1: inelastic |Ed| = 1: unit elastic 38

Price Sensitivity/Elasticity |Ed| > 1: elastic |Ed| < 1: inelastic |Ed| = 1: unit elastic 38

Inelastic and Elastic Demand 5 100

Inelastic and Elastic Demand 5 100

Factors Leading to Less Price Sensitivity • • • The product is more distinctive Buyers are less aware of substitutes Buyers cannot easily compare the quality of substitutes The expenditure is a smaller part of buyer’s total income The expenditure is small compared to the total cost of the end product Part of the cost is paid by another party The product is used with previously purchased assets The product is assumed to have high quality and prestige Buyers cannot store the product

Factors Leading to Less Price Sensitivity • • • The product is more distinctive Buyers are less aware of substitutes Buyers cannot easily compare the quality of substitutes The expenditure is a smaller part of buyer’s total income The expenditure is small compared to the total cost of the end product Part of the cost is paid by another party The product is used with previously purchased assets The product is assumed to have high quality and prestige Buyers cannot store the product

Estimating Demand Curves • Surveys: can explore how many units consumers would by at different proposed prices. • Price experiments: vary the prices of different products in a store or charge different prices for the same product in similar territories to see how the change affects sales. / another approach- Internet • Statistical analysis of prices, quantities sold, and other factors can reveal their relationships. 41

Estimating Demand Curves • Surveys: can explore how many units consumers would by at different proposed prices. • Price experiments: vary the prices of different products in a store or charge different prices for the same product in similar territories to see how the change affects sales. / another approach- Internet • Statistical analysis of prices, quantities sold, and other factors can reveal their relationships. 41

Step 3: Estimating Costs The company wants to charge a price that covers its cost of producing, distributing, and selling the product, including a fair return for its effort and risk. Types of Costs Accumulated Production

Step 3: Estimating Costs The company wants to charge a price that covers its cost of producing, distributing, and selling the product, including a fair return for its effort and risk. Types of Costs Accumulated Production

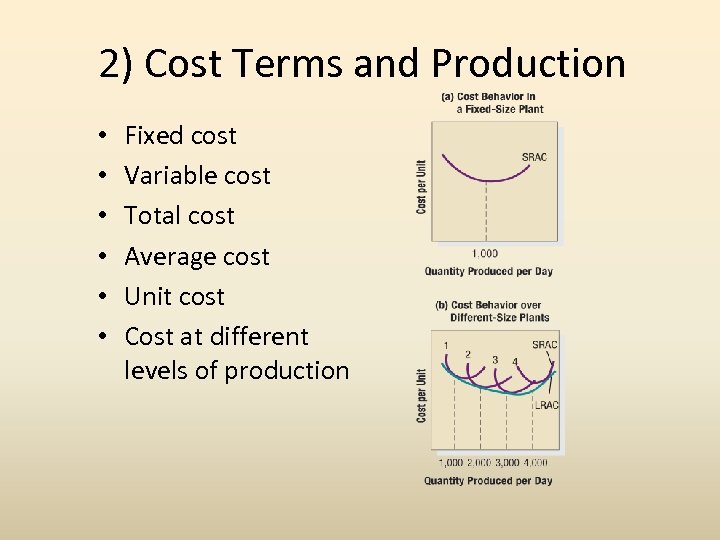

2) Cost Terms and Production • • • Fixed cost Variable cost Total cost Average cost Unit cost Cost at different levels of production

2) Cost Terms and Production • • • Fixed cost Variable cost Total cost Average cost Unit cost Cost at different levels of production

LRAC and SRAC • LRAC: Long Run Average Cost • SRAC: Short Run Average Cost 44

LRAC and SRAC • LRAC: Long Run Average Cost • SRAC: Short Run Average Cost 44

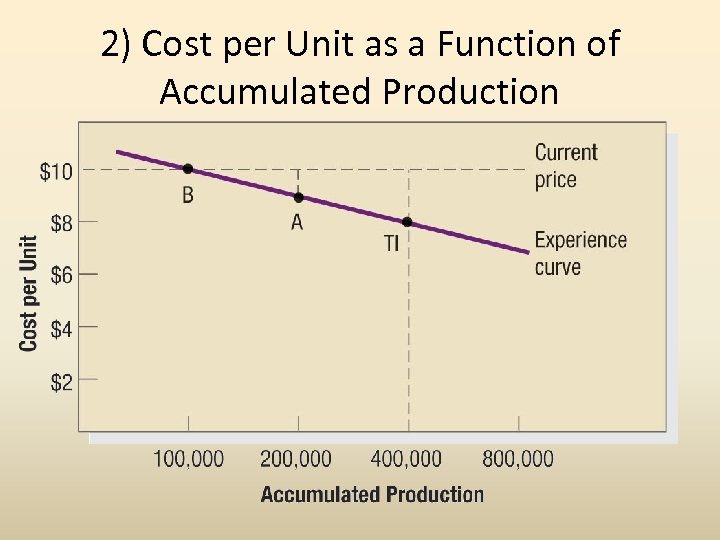

2) Cost per Unit as a Function of Accumulated Production

2) Cost per Unit as a Function of Accumulated Production

Experience/Learning Curve • The decline in the average cost with accumulated production experience is called the experience curve or learning curve. • Ex: A, B and TI • Unit cost of TI = $8, unit cost of A = $10, unit cost of B = $9 46

Experience/Learning Curve • The decline in the average cost with accumulated production experience is called the experience curve or learning curve. • Ex: A, B and TI • Unit cost of TI = $8, unit cost of A = $10, unit cost of B = $9 46

Experience/Learning Curve (cont. ) • If TI sets up its unit price = $9, what will happen? If TI sets up its unit price = $8, what will happen? • May drive the competitors out. • If TI sets up its unit price = $8 or $9, will such a price hurt TI itself? • May make the consumers think TI’s product is of low-quality (recall the price-quality inference…) 47

Experience/Learning Curve (cont. ) • If TI sets up its unit price = $9, what will happen? If TI sets up its unit price = $8, what will happen? • May drive the competitors out. • If TI sets up its unit price = $8 or $9, will such a price hurt TI itself? • May make the consumers think TI’s product is of low-quality (recall the price-quality inference…) 47

Step 4: Analyzing Competitors’ Costs, Prices, and Offers • Does the firm offer features not offered by competitors? • Given this point of comparison, should the price be higher, lower, or the same? • Within the range of possible prices determined by market demand company costs, the firm must take competitors’ costs, prices, and possible price reactions into account. 48

Step 4: Analyzing Competitors’ Costs, Prices, and Offers • Does the firm offer features not offered by competitors? • Given this point of comparison, should the price be higher, lower, or the same? • Within the range of possible prices determined by market demand company costs, the firm must take competitors’ costs, prices, and possible price reactions into account. 48

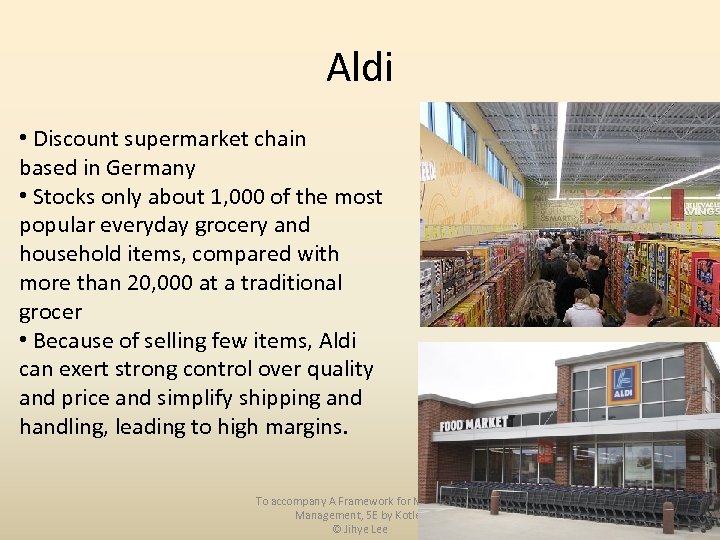

Aldi • Discount supermarket chain based in Germany • Stocks only about 1, 000 of the most popular everyday grocery and household items, compared with more than 20, 000 at a traditional grocer • Because of selling few items, Aldi can exert strong control over quality and price and simplify shipping and handling, leading to high margins. To accompany A Framework for Marketing 49 Management, 5 E by Kotler © Jihye Lee

Aldi • Discount supermarket chain based in Germany • Stocks only about 1, 000 of the most popular everyday grocery and household items, compared with more than 20, 000 at a traditional grocer • Because of selling few items, Aldi can exert strong control over quality and price and simplify shipping and handling, leading to high margins. To accompany A Framework for Marketing 49 Management, 5 E by Kotler © Jihye Lee

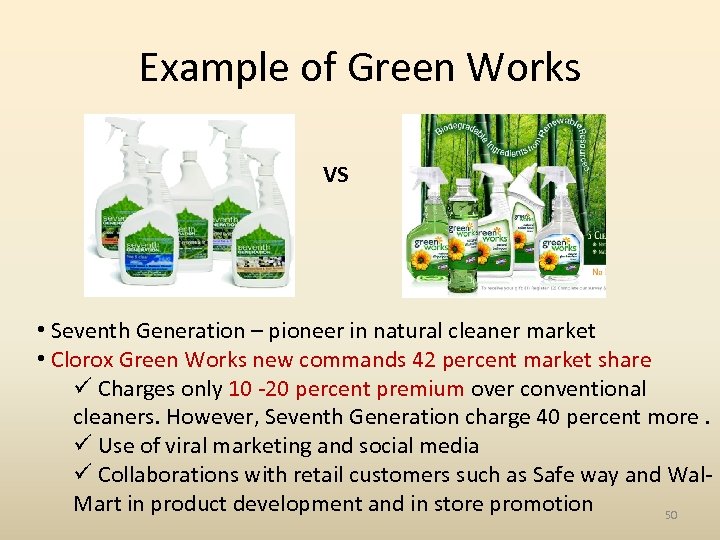

Example of Green Works VS • Seventh Generation – pioneer in natural cleaner market • Clorox Green Works new commands 42 percent market share ü Charges only 10 -20 percent premium over conventional cleaners. However, Seventh Generation charge 40 percent more. ü Use of viral marketing and social media ü Collaborations with retail customers such as Safe way and Wal. Mart in product development and in store promotion 50

Example of Green Works VS • Seventh Generation – pioneer in natural cleaner market • Clorox Green Works new commands 42 percent market share ü Charges only 10 -20 percent premium over conventional cleaners. However, Seventh Generation charge 40 percent more. ü Use of viral marketing and social media ü Collaborations with retail customers such as Safe way and Wal. Mart in product development and in store promotion 50

Step 5: Selecting a Pricing Method • Markup pricing • Target-return pricing • Perceived-value pricing

Step 5: Selecting a Pricing Method • Markup pricing • Target-return pricing • Perceived-value pricing

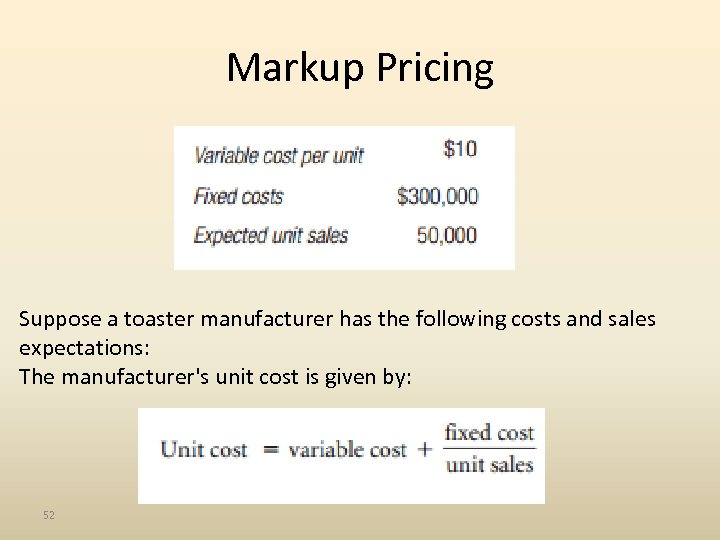

Markup Pricing Suppose a toaster manufacturer has the following costs and sales expectations: The manufacturer's unit cost is given by: 52

Markup Pricing Suppose a toaster manufacturer has the following costs and sales expectations: The manufacturer's unit cost is given by: 52

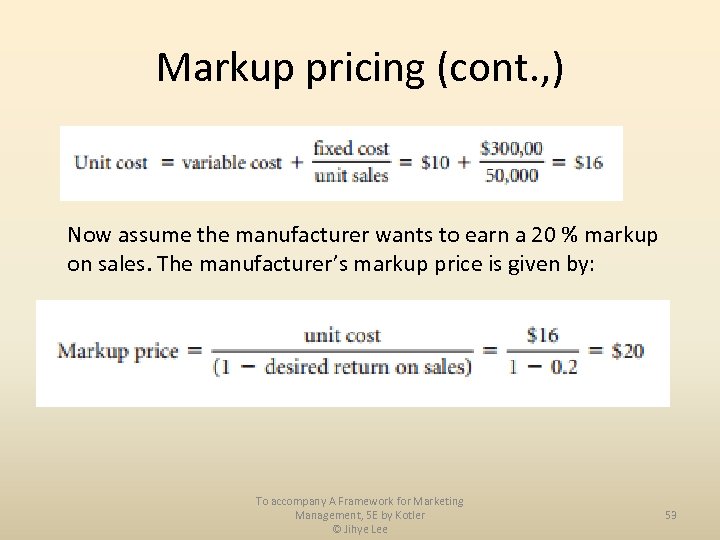

Markup pricing (cont. , ) Now assume the manufacturer wants to earn a 20 % markup on sales. The manufacturer’s markup price is given by: To accompany A Framework for Marketing 53 Management, 5 E by Kotler © Jihye Lee

Markup pricing (cont. , ) Now assume the manufacturer wants to earn a 20 % markup on sales. The manufacturer’s markup price is given by: To accompany A Framework for Marketing 53 Management, 5 E by Kotler © Jihye Lee

Markup Pricing (cont. , ) • The manufacturer will charge dealers $20 per toaster and make a profit of $4 per unit. ($20 -$16; unit cost)= $4 To accompany A Framework for Marketing 54 Management, 5 E by Kotler © Jihye Lee

Markup Pricing (cont. , ) • The manufacturer will charge dealers $20 per toaster and make a profit of $4 per unit. ($20 -$16; unit cost)= $4 To accompany A Framework for Marketing 54 Management, 5 E by Kotler © Jihye Lee

Markup Pricing (cont. , ) • Does the use of standard markups make logical sense? Generally, no. • Any pricing method that ignores current demand, perceived value, and competition is not likely to lead to the optimal price. • Markup pricing works only if the marked up price actually brings in the expected levels of sales. To accompany A Framework for Marketing 55 Management, 5 E by Kotler © Jihye Lee

Markup Pricing (cont. , ) • Does the use of standard markups make logical sense? Generally, no. • Any pricing method that ignores current demand, perceived value, and competition is not likely to lead to the optimal price. • Markup pricing works only if the marked up price actually brings in the expected levels of sales. To accompany A Framework for Marketing 55 Management, 5 E by Kotler © Jihye Lee

Markup Pricing (cont. , ) • However, still markup pricing is popular. 1) Sellers can determine costs much more easily than estimating demand. 2) Industries where all firms use this pricing method, prices tend to be similar and price competition is minimized. 3) Many people feel that cost-plus pricing is fairer to both buyers and sellers. To accompany A Framework for Marketing 56 Management, 5 E by Kotler © Jihye Lee

Markup Pricing (cont. , ) • However, still markup pricing is popular. 1) Sellers can determine costs much more easily than estimating demand. 2) Industries where all firms use this pricing method, prices tend to be similar and price competition is minimized. 3) Many people feel that cost-plus pricing is fairer to both buyers and sellers. To accompany A Framework for Marketing 56 Management, 5 E by Kotler © Jihye Lee

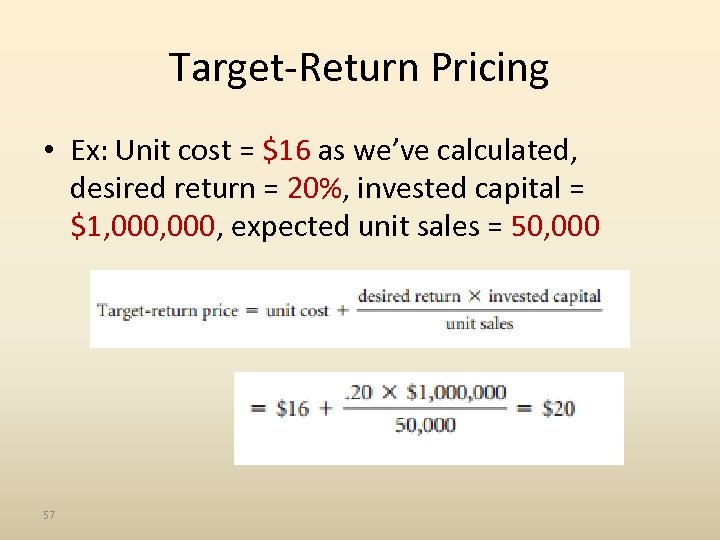

Target-Return Pricing • Ex: Unit cost = $16 as we’ve calculated, desired return = 20%, invested capital = $1, 000, expected unit sales = 50, 000 57

Target-Return Pricing • Ex: Unit cost = $16 as we’ve calculated, desired return = 20%, invested capital = $1, 000, expected unit sales = 50, 000 57

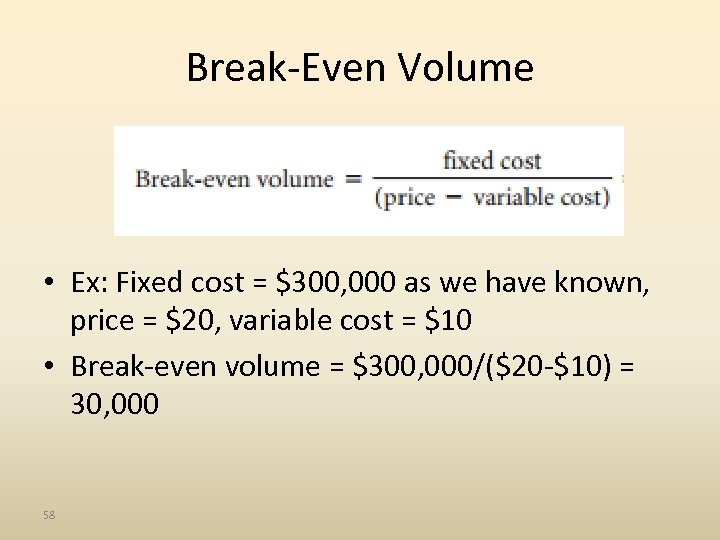

Break-Even Volume • Ex: Fixed cost = $300, 000 as we have known, price = $20, variable cost = $10 • Break-even volume = $300, 000/($20 -$10) = 30, 000 58

Break-Even Volume • Ex: Fixed cost = $300, 000 as we have known, price = $20, variable cost = $10 • Break-even volume = $300, 000/($20 -$10) = 30, 000 58

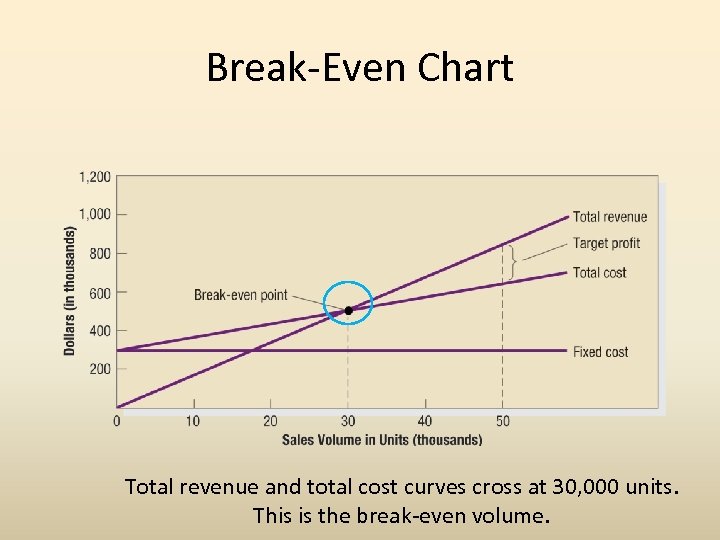

Break-Even Chart Total revenue and total cost curves cross at 30, 000 units. This is the break-even volume.

Break-Even Chart Total revenue and total cost curves cross at 30, 000 units. This is the break-even volume.

Perceived-Value Pricing • Made up of a host of inputs, such as the buyer’s image of the product performance, the channel deliverables, the warranty quality, customer support and trustworthiness, and esteem. 60

Perceived-Value Pricing • Made up of a host of inputs, such as the buyer’s image of the product performance, the channel deliverables, the warranty quality, customer support and trustworthiness, and esteem. 60

Perceived-Value Pricing (cont. , ) • Companies must deliver the value promised by their value proposition, and the customer must perceive this value. • Firms use the other marketing program elements, such as advertising, sales force, and the Internet, to communicate and enhance perceived value in buyers’ minds. 61

Perceived-Value Pricing (cont. , ) • Companies must deliver the value promised by their value proposition, and the customer must perceive this value. • Firms use the other marketing program elements, such as advertising, sales force, and the Internet, to communicate and enhance perceived value in buyers’ minds. 61

Perceived-Value Pricing – Example of Caterpillar • Caterpillar uses perceived value to set prices on its construction equipment. • It might price its tractor at $100, 000/competitor’s tractor might $90, 000 • Customer asks to dealer why he should pay $10, 000 more. 62

Perceived-Value Pricing – Example of Caterpillar • Caterpillar uses perceived value to set prices on its construction equipment. • It might price its tractor at $100, 000/competitor’s tractor might $90, 000 • Customer asks to dealer why he should pay $10, 000 more. 62

Perceived-Value Pricing – Example of Caterpillar • Dealer answers: $90, 000 - is the tractor’s price if it’s only equivalent to the competitors’ tractor $7, 000 - is the price premium for Caterpillar’s superior durability $6, 000 – is the price premium for Caterpillar’s superior reliability $5, 000 – Caterpillar’s superior service $2, 000 – Caterpillar’s longer warranty on parts $110, 000 – normal price to cover Caterpillar’s superior value(add them all) - $10, 000 – discount (substitute from final price) = $100, 000 – final price 63

Perceived-Value Pricing – Example of Caterpillar • Dealer answers: $90, 000 - is the tractor’s price if it’s only equivalent to the competitors’ tractor $7, 000 - is the price premium for Caterpillar’s superior durability $6, 000 – is the price premium for Caterpillar’s superior reliability $5, 000 – Caterpillar’s superior service $2, 000 – Caterpillar’s longer warranty on parts $110, 000 – normal price to cover Caterpillar’s superior value(add them all) - $10, 000 – discount (substitute from final price) = $100, 000 – final price 63

Perceived-Value Pricing – Example of Caterpillar • The Caterpillar dealer is able to show that although the customer is asked to pay a $10, 000 premium, he is actually getting $20, 000 extra value!! *($110, 000$90, 000) • The customer choose the Caterpillar tractor because he is convinced its lifetime operating costs will be lower • Ensuring that customers appreciate the total value of a product or service offering is crucial. To accompany A Framework for Marketing 64 Management, 5 E by Kotler © Jihye Lee

Perceived-Value Pricing – Example of Caterpillar • The Caterpillar dealer is able to show that although the customer is asked to pay a $10, 000 premium, he is actually getting $20, 000 extra value!! *($110, 000$90, 000) • The customer choose the Caterpillar tractor because he is convinced its lifetime operating costs will be lower • Ensuring that customers appreciate the total value of a product or service offering is crucial. To accompany A Framework for Marketing 64 Management, 5 E by Kotler © Jihye Lee

Example of premium pricing • PACCAR loyal customer for 20 years. • Order other 700 new trucks, despite their higher price, because of their higher perceived quality- greater reliability, higher trade-in value, even the superior plush interiors that might attract better drivers. Because of its high standards for quality and continual innovation, PACCAR can charge a premium for its trucks. To accompany A Framework for Marketing 65 Management, 5 E by Kotler © Jihye Lee

Example of premium pricing • PACCAR loyal customer for 20 years. • Order other 700 new trucks, despite their higher price, because of their higher perceived quality- greater reliability, higher trade-in value, even the superior plush interiors that might attract better drivers. Because of its high standards for quality and continual innovation, PACCAR can charge a premium for its trucks. To accompany A Framework for Marketing 65 Management, 5 E by Kotler © Jihye Lee

Step 6: Selecting the Final Price • Impact of other marketing activities • Company pricing policies • Gain-and-risk sharing pricing • Impact of price on other parties

Step 6: Selecting the Final Price • Impact of other marketing activities • Company pricing policies • Gain-and-risk sharing pricing • Impact of price on other parties

Impact of Other Marketing Activities • Brands with average relative quality but high relative advertising budgets were able to charge premium prices. • Brands with high relative quality and high relative advertising obtained the highest prices. • The positive relationship between high prices and high advertising held most strongly in the later stages of the product life cycle for market leaders. 67

Impact of Other Marketing Activities • Brands with average relative quality but high relative advertising budgets were able to charge premium prices. • Brands with high relative quality and high relative advertising obtained the highest prices. • The positive relationship between high prices and high advertising held most strongly in the later stages of the product life cycle for market leaders. 67

Company Pricing Policies • Price must be consistent with pricing policies. • However, companies are establishing pricing penalties under certain circumstances. • Ex: airlines charge $150 to those who change their reservations on discount price. • Ex: Banks charge fees for too many withdrawals in a month. 68

Company Pricing Policies • Price must be consistent with pricing policies. • However, companies are establishing pricing penalties under certain circumstances. • Ex: airlines charge $150 to those who change their reservations on discount price. • Ex: Banks charge fees for too many withdrawals in a month. 68

Gain-and-Risk-Sharing Pricing • Buyers may resist accepting a seller’s proposal because of a high perceived level of risk. The seller has the option of offering to absorb part of all the risk if it does not deliver the full promised value. • Ex: manufacturer warranty • Ex: Baxter Healthcare(leading medical products firm) – secure contract for an information management systems from a leading health care provider 69

Gain-and-Risk-Sharing Pricing • Buyers may resist accepting a seller’s proposal because of a high perceived level of risk. The seller has the option of offering to absorb part of all the risk if it does not deliver the full promised value. • Ex: manufacturer warranty • Ex: Baxter Healthcare(leading medical products firm) – secure contract for an information management systems from a leading health care provider 69

Impact of Price on Other Parties • How will distributors and dealers feel about it? If they don’t make enough profit, they may not choose to bring the product to market. • Will the sales force be willing to sell at that price? How will competitors react? Will suppliers raise their prices when they see the company’s price? Will the government intervene and prevent this price from being charged? 70

Impact of Price on Other Parties • How will distributors and dealers feel about it? If they don’t make enough profit, they may not choose to bring the product to market. • Will the sales force be willing to sell at that price? How will competitors react? Will suppliers raise their prices when they see the company’s price? Will the government intervene and prevent this price from being charged? 70

Structure of Part 8: Pricing Strategies • • 71 Understanding the Pricing Setting the Price Adapting the Price Initiating and Responding to Price Changes

Structure of Part 8: Pricing Strategies • • 71 Understanding the Pricing Setting the Price Adapting the Price Initiating and Responding to Price Changes

Adapting the Price • Companies usually do not set a single price, but rather develop a pricing structure that reflects variations in geographical demand costs, market-segment requirements, etc. • As a result of discounts, allowances, and promotional support, a company rarely realizes the same profit from each unit of a product that it sells. 72

Adapting the Price • Companies usually do not set a single price, but rather develop a pricing structure that reflects variations in geographical demand costs, market-segment requirements, etc. • As a result of discounts, allowances, and promotional support, a company rarely realizes the same profit from each unit of a product that it sells. 72

Adapting the Price (cont. ) • How to offer differentiated prices to different segments of customers? Related to segmentation and differentiation. 73

Adapting the Price (cont. ) • How to offer differentiated prices to different segments of customers? Related to segmentation and differentiation. 73

Price-Adaptation Strategies Geographical Pricing Discounts/Allowances Promotional Pricing Differentiated Pricing

Price-Adaptation Strategies Geographical Pricing Discounts/Allowances Promotional Pricing Differentiated Pricing

Geographical Pricing • In geographical pricing, the company decides how to price its products to different customers in different locations and countries. • Ex: P&G 75

Geographical Pricing • In geographical pricing, the company decides how to price its products to different customers in different locations and countries. • Ex: P&G 75

P&G – China Market 76

P&G – China Market 76

P&G (cont. ) • China is P&G’s 6 th-largest market, yet 2/3 of China’s population earns less than $25 per month. So in 2003 developed a tiered pricing initiative to help compete against cheaper local brands while still protecting the value of its global brands. P&G introduced a 320 -gram bag of Tide Clean White for 23 cents, compared with 33 cents for 350 grams of Tide Triple Action. The Clean White version doesn’t offer such benefits as stain removal and fragrance, but it costs less to make and, according to P&G, outperforms every other brand at that price level. 77

P&G (cont. ) • China is P&G’s 6 th-largest market, yet 2/3 of China’s population earns less than $25 per month. So in 2003 developed a tiered pricing initiative to help compete against cheaper local brands while still protecting the value of its global brands. P&G introduced a 320 -gram bag of Tide Clean White for 23 cents, compared with 33 cents for 350 grams of Tide Triple Action. The Clean White version doesn’t offer such benefits as stain removal and fragrance, but it costs less to make and, according to P&G, outperforms every other brand at that price level. 77

Price Discounts/Allowances • Most companies will adjust their list price and give discounts and allowances for early payment, volume purchases, and off-season buying. • However, only 15% to 35% of buyers in most categories are price sensitive. 78

Price Discounts/Allowances • Most companies will adjust their list price and give discounts and allowances for early payment, volume purchases, and off-season buying. • However, only 15% to 35% of buyers in most categories are price sensitive. 78

Bloomberg LP • Bloomberg LP markets a subscription service that sells reams of financial data, analytic software to leverage the data’s usefulness, trading tools, and even news. Users get all this data via a specialized terminal and a color-coded keyboard that pops the desired information onto the screen. The price is $1, 800 a month, or just a little over $1, 500 each for multiple setups in the same company, whether 2 or 2, 000. Banking on the perceived worth of its product and strong user loyalty, Bloomberg knows it doesn’t need to discount. 79

Bloomberg LP • Bloomberg LP markets a subscription service that sells reams of financial data, analytic software to leverage the data’s usefulness, trading tools, and even news. Users get all this data via a specialized terminal and a color-coded keyboard that pops the desired information onto the screen. The price is $1, 800 a month, or just a little over $1, 500 each for multiple setups in the same company, whether 2 or 2, 000. Banking on the perceived worth of its product and strong user loyalty, Bloomberg knows it doesn’t need to discount. 79

Bloomberg LP (cont. ) • Reuters, a competing service, actually has more terminals installed than Bloomberg, but it doesn’t come close to getting as much revenue from each. Bloomberg’s revenue, on the other hand, keeps going up. When Bloomberg needs to raise its rates, it has an equally simple, one-size-fits-all policy; it raises price 5% every two years (customers enter a twoyear contract when they subscribe). 80

Bloomberg LP (cont. ) • Reuters, a competing service, actually has more terminals installed than Bloomberg, but it doesn’t come close to getting as much revenue from each. Bloomberg’s revenue, on the other hand, keeps going up. When Bloomberg needs to raise its rates, it has an equally simple, one-size-fits-all policy; it raises price 5% every two years (customers enter a twoyear contract when they subscribe). 80

When Discounting May Be a Useful Tool • For example, if a company can gain concessions in return, such as when the customer agrees to sign a longer contract, is willing to order electronically, thus saving the company money, or agrees to buy in truckload quantities. 81

When Discounting May Be a Useful Tool • For example, if a company can gain concessions in return, such as when the customer agrees to sign a longer contract, is willing to order electronically, thus saving the company money, or agrees to buy in truckload quantities. 81

Types of Discounts/Allowances Discounts/ Allowances • Cash discount • Quantity discount ($10 per unit for fewer than 100 units: $9 per unit for 100 or more units) • Functional discount • Seasonal discount (out of season) • Allowance (trade- in: old item to new one/promotional allowances: participating in ads and sales support programs) • Price-Off Promotions • Coupons and Rebates 82

Types of Discounts/Allowances Discounts/ Allowances • Cash discount • Quantity discount ($10 per unit for fewer than 100 units: $9 per unit for 100 or more units) • Functional discount • Seasonal discount (out of season) • Allowance (trade- in: old item to new one/promotional allowances: participating in ads and sales support programs) • Price-Off Promotions • Coupons and Rebates 82

Promotional Pricing • • 83 Loss-leader pricing Special-event pricing Cash rebates Low-interest financing Longer payment terms Warranties and service contracts Psychological discounting

Promotional Pricing • • 83 Loss-leader pricing Special-event pricing Cash rebates Low-interest financing Longer payment terms Warranties and service contracts Psychological discounting

Loss-Leader Pricing • Supermarkets and department stores often drop the price on well-known brands to stimulate additional store traffic. • This pays if the revenue on the additional sales compensates for the lower margins on the lossleader items. • Manufacturers of loss-leader brands may object because this practice can dilute the brand image. • Ex: Nordstrom seasonal sales: winter- Northface 84

Loss-Leader Pricing • Supermarkets and department stores often drop the price on well-known brands to stimulate additional store traffic. • This pays if the revenue on the additional sales compensates for the lower margins on the lossleader items. • Manufacturers of loss-leader brands may object because this practice can dilute the brand image. • Ex: Nordstrom seasonal sales: winter- Northface 84

Special-Event Pricing • Sellers will establish special prices in certain seasons to draw in more customers. • Ex: Back-to-school sales in August. (Staples, Bookstore, Clothing and etc. ) 85

Special-Event Pricing • Sellers will establish special prices in certain seasons to draw in more customers. • Ex: Back-to-school sales in August. (Staples, Bookstore, Clothing and etc. ) 85

Cash Rebates • Rebates can help clear inventories without cutting the stated list price. • Auto companies and other consumer-goods companies offer cash rebates to encourage purchase of the manufacturers’ products within a specified time period. • Grocery store: Pickn. Save 86

Cash Rebates • Rebates can help clear inventories without cutting the stated list price. • Auto companies and other consumer-goods companies offer cash rebates to encourage purchase of the manufacturers’ products within a specified time period. • Grocery store: Pickn. Save 86

Low-Interest Financing • Instead of cutting its price, the company can offer customers low-interest financing. • Automakers have used no-interest financing to try to attract more customers. • Ex. Toyota after recall 87

Low-Interest Financing • Instead of cutting its price, the company can offer customers low-interest financing. • Automakers have used no-interest financing to try to attract more customers. • Ex. Toyota after recall 87

Longer Payment Terms • Sellers, esp. mortgage banks and auto companies, stretch loans over longer periods and thus lower the monthly payments. • Then consumers often worry less about the cost (the interest rate) of a loan and more about whether they can afford the monthly payment. 88

Longer Payment Terms • Sellers, esp. mortgage banks and auto companies, stretch loans over longer periods and thus lower the monthly payments. • Then consumers often worry less about the cost (the interest rate) of a loan and more about whether they can afford the monthly payment. 88

Warranties and Service Contracts • Companies can promote sales by adding a free or low-cost warranty or service contract. • Ex. Often computer industry. Hyundai car – 10 years warranty 89

Warranties and Service Contracts • Companies can promote sales by adding a free or low-cost warranty or service contract. • Ex. Often computer industry. Hyundai car – 10 years warranty 89

Psychological Discounting • This strategy sets an artificially high price and then offers the product at substantial savings. • Ex: “Was $359, now $299” 90

Psychological Discounting • This strategy sets an artificially high price and then offers the product at substantial savings. • Ex: “Was $359, now $299” 90

Differentiated Pricing • • 91 Price discrimination Customer-segment pricing Product-form pricing Image pricing Channel pricing Location pricing Time pricing

Differentiated Pricing • • 91 Price discrimination Customer-segment pricing Product-form pricing Image pricing Channel pricing Location pricing Time pricing

Price Discrimination • Price discrimination occurs when a company sells a product or service at two or more prices that do not reflect a proportional difference in costs. • Ex. Lands’ End creates men’s shirts in many different styles, weights, and levels of quality. • As of January 2010, a men’s white button-down shirt could cost as little as $14. 99 or as much as $79. 50 92

Price Discrimination • Price discrimination occurs when a company sells a product or service at two or more prices that do not reflect a proportional difference in costs. • Ex. Lands’ End creates men’s shirts in many different styles, weights, and levels of quality. • As of January 2010, a men’s white button-down shirt could cost as little as $14. 99 or as much as $79. 50 92

Price Discrimination • First-degree price discrimination: Seller charges a separate price to each customer depending on the intensity of his or her demand. Perfectly customized price • Second-degree price discrimination: Quantity discrimination. Charge less to buyers of larger volumes. E. g. , cell phone service- tiered pricing – consumers paying more with higher levels of usage. 93

Price Discrimination • First-degree price discrimination: Seller charges a separate price to each customer depending on the intensity of his or her demand. Perfectly customized price • Second-degree price discrimination: Quantity discrimination. Charge less to buyers of larger volumes. E. g. , cell phone service- tiered pricing – consumers paying more with higher levels of usage. 93

Third-Degree Price Discrimination • • • 94 Customer-segment pricing Product-form pricing Image pricing Channel pricing Location pricing Time pricing

Third-Degree Price Discrimination • • • 94 Customer-segment pricing Product-form pricing Image pricing Channel pricing Location pricing Time pricing

Customer-Segment Pricing • Different customer groups pay different prices for the same product or service. • For example, museums often charge a lower admission fee to students and senior citizens. 95

Customer-Segment Pricing • Different customer groups pay different prices for the same product or service. • For example, museums often charge a lower admission fee to students and senior citizens. 95

Product-Form Pricing • Different versions of the product are priced differently, but not proportionately to their costs. • Ex: Evian prices a 48 -ounce bottle of its mineral water at $2. 00. It takes the same water and packages 1. 7 ounces in a moisturizer spray for $6. 00. Through product-form pricing, Evian manages to charge $3. 50 an ounce on one form and about $0. 04 an ounce in another. 96

Product-Form Pricing • Different versions of the product are priced differently, but not proportionately to their costs. • Ex: Evian prices a 48 -ounce bottle of its mineral water at $2. 00. It takes the same water and packages 1. 7 ounces in a moisturizer spray for $6. 00. Through product-form pricing, Evian manages to charge $3. 50 an ounce on one form and about $0. 04 an ounce in another. 96

Image Pricing • Some companies price the same product at two different levels based on image differences. • Ex: The same perfume can be put in two different bottles with two different names and sold at different prices. • Ex: Shampoo with different names and images. 97

Image Pricing • Some companies price the same product at two different levels based on image differences. • Ex: The same perfume can be put in two different bottles with two different names and sold at different prices. • Ex: Shampoo with different names and images. 97

Channel Pricing • Coca-Cola carries a different price depending on whether the consumer purchases it in a fine restaurant, a fast-food restaurant, or a vending machine. 98

Channel Pricing • Coca-Cola carries a different price depending on whether the consumer purchases it in a fine restaurant, a fast-food restaurant, or a vending machine. 98

Location Pricing • The same product is priced differently at different locations even though the cost of offering it at each location is the same. • Ex: A theater varies its seat prices according to audience preferences for different locations. 99

Location Pricing • The same product is priced differently at different locations even though the cost of offering it at each location is the same. • Ex: A theater varies its seat prices according to audience preferences for different locations. 99

Time Pricing • Prices are varied by season, day, or hour. • Ex: Public utilities vary energy rates to commercial users by time of day and weekend versus weekday. Restaurants charge less to “early bird” customers, and some hotels charge less on weekends. 100

Time Pricing • Prices are varied by season, day, or hour. • Ex: Public utilities vary energy rates to commercial users by time of day and weekend versus weekday. Restaurants charge less to “early bird” customers, and some hotels charge less on weekends. 100

Examples of Price Discrimination • Shipping company APL Inc. rewards customers who can better predict how much cargo space they’ll need with cheaper rates for booking early. • Such a tactic is to use variable prices as a reward for good behavior rather than as a penalty. 101

Examples of Price Discrimination • Shipping company APL Inc. rewards customers who can better predict how much cargo space they’ll need with cheaper rates for booking early. • Such a tactic is to use variable prices as a reward for good behavior rather than as a penalty. 101

Examples of Price Discrimination (cont. ) • Catalog retailers such as Victoria’s Secret routinely send out catalogs that sell identical goods at different prices. Consumers who live in a more free-spending zip code may see only the higher prices. • Office product superstore Staples also sends out office supply catalogs with different prices. 102

Examples of Price Discrimination (cont. ) • Catalog retailers such as Victoria’s Secret routinely send out catalogs that sell identical goods at different prices. Consumers who live in a more free-spending zip code may see only the higher prices. • Office product superstore Staples also sends out office supply catalogs with different prices. 102

Conditions for Price Discrimination to Work • (1) The market must be segmentable and the segments must show different intensities of demand. • (2) Members in the lower-price segment must not be able to resell the product to the higher-price segment. • (3) competitors must not be able to undersell the firm in the higher-price segment. • (4) the cost of segmenting and policing the market must not exceed the extra revenue derived from price discrimination. • (5) the practice must not breed customer resentment and ill will. • (6) The particular form of price discrimination must not be illegal. 103

Conditions for Price Discrimination to Work • (1) The market must be segmentable and the segments must show different intensities of demand. • (2) Members in the lower-price segment must not be able to resell the product to the higher-price segment. • (3) competitors must not be able to undersell the firm in the higher-price segment. • (4) the cost of segmenting and policing the market must not exceed the extra revenue derived from price discrimination. • (5) the practice must not breed customer resentment and ill will. • (6) The particular form of price discrimination must not be illegal. 103

Pricing Strategies • • 104 Understanding the Pricing Setting the Price Adapting the Price Initiating and Responding to Price Changes

Pricing Strategies • • 104 Understanding the Pricing Setting the Price Adapting the Price Initiating and Responding to Price Changes

Initiating and Responding to Price Changes • Initiating Price Cuts • Initiating Price Increases • Responding to Competitors’ Price Changes 105

Initiating and Responding to Price Changes • Initiating Price Cuts • Initiating Price Increases • Responding to Competitors’ Price Changes 105

Initiating Price cuts: Circumstances Leading to Price Cuts • Excess plant capacity: The firm needs additional business and cannot generate it through increased sales effort, product improvement, or other measures. • Drive to dominate the market through lower costs: Either the company starts with lower costs than its competitors, or it initiates price cuts in the hope of gaining market share and lower costs. 106

Initiating Price cuts: Circumstances Leading to Price Cuts • Excess plant capacity: The firm needs additional business and cannot generate it through increased sales effort, product improvement, or other measures. • Drive to dominate the market through lower costs: Either the company starts with lower costs than its competitors, or it initiates price cuts in the hope of gaining market share and lower costs. 106

Traps in Initiating Price Cuts Low-quality trap Fragile-market-share trap Shallow-pockets trap Price-war trap 107

Traps in Initiating Price Cuts Low-quality trap Fragile-market-share trap Shallow-pockets trap Price-war trap 107

Low-Quality Trap • By price-quality inference, when the firm cuts the price, consumers may assume quality is low. 108

Low-Quality Trap • By price-quality inference, when the firm cuts the price, consumers may assume quality is low. 108

Fragile-Market-Share Trap • A low price buys market share but not market loyalty. The same customers will shift to any lower-priced firm that comes along. • The consumers may form up the habit of asking for lower prices. 109

Fragile-Market-Share Trap • A low price buys market share but not market loyalty. The same customers will shift to any lower-priced firm that comes along. • The consumers may form up the habit of asking for lower prices. 109

Shallow-Pockets Trap • Higher-priced competitors match the lower prices but have longer staying power because of deeper cash reserves. 110

Shallow-Pockets Trap • Higher-priced competitors match the lower prices but have longer staying power because of deeper cash reserves. 110

Price-War Trap • Competitors respond by lowering their prices even more, triggering a price war. • Example: US airlines industry 111

Price-War Trap • Competitors respond by lowering their prices even more, triggering a price war. • Example: US airlines industry 111

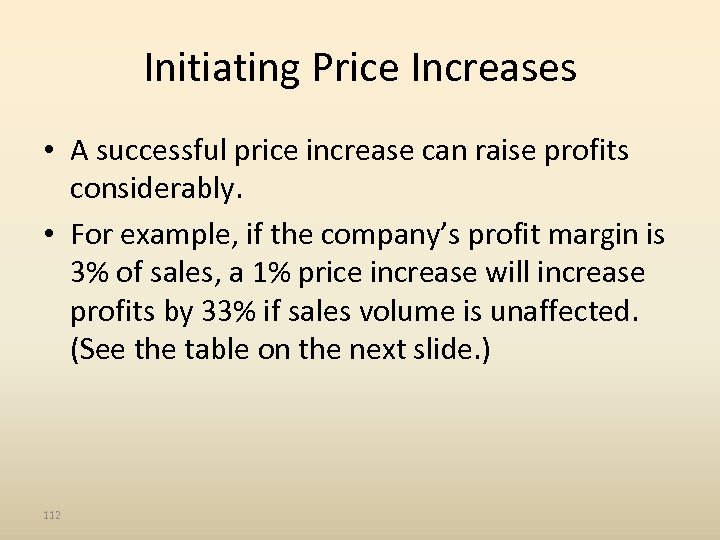

Initiating Price Increases • A successful price increase can raise profits considerably. • For example, if the company’s profit margin is 3% of sales, a 1% price increase will increase profits by 33% if sales volume is unaffected. (See the table on the next slide. ) 112

Initiating Price Increases • A successful price increase can raise profits considerably. • For example, if the company’s profit margin is 3% of sales, a 1% price increase will increase profits by 33% if sales volume is unaffected. (See the table on the next slide. ) 112

Profits Before and After a Price Increase

Profits Before and After a Price Increase

What May Provoke Price Increases • Cost inflation: Rising costs unmatched by productivity gains squeeze profit margins and lead companies to regular rounds of price increases. • Anticipatory pricing: Companies often raise their prices by more than the cost increase, in anticipation of further inflation or government price controls. • Overdemand: When a company cannot supply all its customers, it can use techniques: (next slides) 114

What May Provoke Price Increases • Cost inflation: Rising costs unmatched by productivity gains squeeze profit margins and lead companies to regular rounds of price increases. • Anticipatory pricing: Companies often raise their prices by more than the cost increase, in anticipation of further inflation or government price controls. • Overdemand: When a company cannot supply all its customers, it can use techniques: (next slides) 114

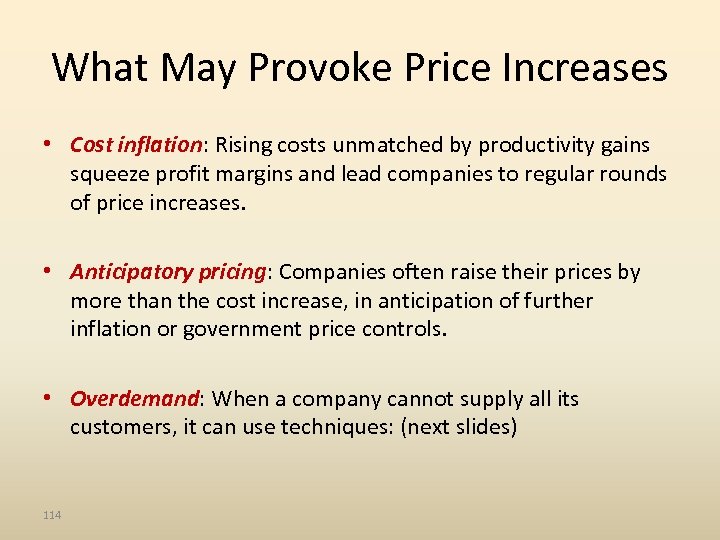

Ways of Initiating Price Increases Delayed quotation pricing Escalator clauses Unbundling Reduction of discounts

Ways of Initiating Price Increases Delayed quotation pricing Escalator clauses Unbundling Reduction of discounts

Delayed Quotation Pricing • The company does not set a final price until the product is finished or delivered. • This pricing is prevalent in industries with long production lead times, such as industrial construction and heavy equipment. 116

Delayed Quotation Pricing • The company does not set a final price until the product is finished or delivered. • This pricing is prevalent in industries with long production lead times, such as industrial construction and heavy equipment. 116

Escalator Clauses • The company requires the customer to pay today’s price and all or part of any inflation increase that takes place before delivery. • An escalator clause bases price increases on some specified price index. • Escalator clauses are found in contracts for major industrial projects, such as aircraft construction and bridge building. 117

Escalator Clauses • The company requires the customer to pay today’s price and all or part of any inflation increase that takes place before delivery. • An escalator clause bases price increases on some specified price index. • Escalator clauses are found in contracts for major industrial projects, such as aircraft construction and bridge building. 117

Unbundling • The company maintains its price but removes or prices separately one or more elements that were part of the former offer, such as free delivery or installation. • Car companies sometimes add antilock brakes and passenger-side airbags as supplementary extras to their vehicles. 118

Unbundling • The company maintains its price but removes or prices separately one or more elements that were part of the former offer, such as free delivery or installation. • Car companies sometimes add antilock brakes and passenger-side airbags as supplementary extras to their vehicles. 118

Reduction of Discounts • The company instructs its sales force not to offer its normal cash and quantity discounts. 119

Reduction of Discounts • The company instructs its sales force not to offer its normal cash and quantity discounts. 119

Consumers Reactions to Price Increases • (1) A price increase may carry some positive meanings to customers – for example, that the item is “hot” and represents an unusually good value. • (2) In general consumers dislike higher prices. • (3) The more similar the products or offerings from a company, the more likely consumers are to interpret any pricing differences as unfair. • (4) Generally, consumers prefer small price increases on a regular basis to sudden, sharp increases. 120

Consumers Reactions to Price Increases • (1) A price increase may carry some positive meanings to customers – for example, that the item is “hot” and represents an unusually good value. • (2) In general consumers dislike higher prices. • (3) The more similar the products or offerings from a company, the more likely consumers are to interpret any pricing differences as unfair. • (4) Generally, consumers prefer small price increases on a regular basis to sudden, sharp increases. 120

How to Avoid Hostile Reaction to Price Increases • Consumers may turn against companies that increase their prices. • How to avoid such hostile reaction when prices rise? The most important is to give consumers some senses of fairness in price hikes. 121

How to Avoid Hostile Reaction to Price Increases • Consumers may turn against companies that increase their prices. • How to avoid such hostile reaction when prices rise? The most important is to give consumers some senses of fairness in price hikes. 121

Alternative Approaches to Price Increase • (1) Shrinking the amount of product instead of raising the price. • Ex: Hershey Foods maintained its candy bar price but trimmed its size. Nestle maintained its size but raised the price. • (2) Substituting less-expensive materials or ingredients. • Ex: Many candy bar companies substituted synthetic chocolate for real chocolate to fight price increases in cocoa. 122

Alternative Approaches to Price Increase • (1) Shrinking the amount of product instead of raising the price. • Ex: Hershey Foods maintained its candy bar price but trimmed its size. Nestle maintained its size but raised the price. • (2) Substituting less-expensive materials or ingredients. • Ex: Many candy bar companies substituted synthetic chocolate for real chocolate to fight price increases in cocoa. 122

Alternative Approaches to Price Increase (cont. ) • (3) Reducing or removing product features. • Ex: Sears engineered down a number of its appliances so they could be priced competitively with those sold in discount stores. • (4) Removing or reducing product services, such as installation or free delivery. • (5) Using less-expensive packaging material or larger package sizes. 123

Alternative Approaches to Price Increase (cont. ) • (3) Reducing or removing product features. • Ex: Sears engineered down a number of its appliances so they could be priced competitively with those sold in discount stores. • (4) Removing or reducing product services, such as installation or free delivery. • (5) Using less-expensive packaging material or larger package sizes. 123

Alternative Approaches to Price Increase (cont. ) • (6) Creating new economy brands. • Ex: Jewel food stores introduced 170 generic items selling at 10% to 30% less than national brands. 124

Alternative Approaches to Price Increase (cont. ) • (6) Creating new economy brands. • Ex: Jewel food stores introduced 170 generic items selling at 10% to 30% less than national brands. 124

Brand Leader Responses to Competitive Price Cuts • • • Maintain price and add value Reduce price Increase price and improve quality Others

Brand Leader Responses to Competitive Price Cuts • • • Maintain price and add value Reduce price Increase price and improve quality Others

Responding to Competitors’ Price Changes: The Case of General Mills 126

Responding to Competitors’ Price Changes: The Case of General Mills 126

General Mills • General Mills ran into some trouble by not responding to competitors’ price changes. • While both private-label cereals and name-brand competitors, such as Kellogg, decreased package sizes and either lowered cereal prices or kept them static, General Mills banked on its brand-name reputation for quality and innovation and kept its prices at premium level. 127

General Mills • General Mills ran into some trouble by not responding to competitors’ price changes. • While both private-label cereals and name-brand competitors, such as Kellogg, decreased package sizes and either lowered cereal prices or kept them static, General Mills banked on its brand-name reputation for quality and innovation and kept its prices at premium level. 127

General Mills (cont. ) • But many customers were reluctant to pay above $4. 00 for a box of Cheerios or Lucky Charms, As a result, Kellogg took the lead in the cereal category in terms of dollar share, with 33. 8% compared to General Mills’ 29. 7%. • Finally, in 2007, General Mills announced its “right size, right price” strategy, adjusting package sizes downward (as its rivals already had) and lowering its prices. 128

General Mills (cont. ) • But many customers were reluctant to pay above $4. 00 for a box of Cheerios or Lucky Charms, As a result, Kellogg took the lead in the cereal category in terms of dollar share, with 33. 8% compared to General Mills’ 29. 7%. • Finally, in 2007, General Mills announced its “right size, right price” strategy, adjusting package sizes downward (as its rivals already had) and lowering its prices. 128