655f58f2db940380d9e3869900c7fc09.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 18

Child Sexual Exploitation – Moral Panic or Legitimate Concern? Stuart Allardyce Lisa Gamble Deputy Children’s Service Manager Barnardo’s Skylight / Lighthouse Policy and Research lead for CSE Barnardo’s Scotland stuart. allardyce@barnardos. org. uk lisa. gamble@barnardos. org. uk

Child Sexual Exploitation – Moral Panic or Legitimate Concern? Stuart Allardyce Lisa Gamble Deputy Children’s Service Manager Barnardo’s Skylight / Lighthouse Policy and Research lead for CSE Barnardo’s Scotland stuart. allardyce@barnardos. org. uk lisa. gamble@barnardos. org. uk

What is a moral panic? n n n A condition, episode, person or group of persons that becomes defined as a threat to societal values and interests; The threat is presented in a stylized and stereotypical fashion by the mass media; The novelty of the issue is emphasised in media coverage; The media coverage of the threat is out of all proportion to the actual threat; ‘moral entrepreneurs’ (e. g. academics, editors, politicians, judiciary religious figures, the third sector, police chiefs, etc) present the threat in similar ways in relation to rates, sources of the problem, future potential escalation and solutions; the condition then disappears, submerges or deteriorates or becomes more invisible. (Cohen 1972, Hall et al. 1978)

What is a moral panic? n n n A condition, episode, person or group of persons that becomes defined as a threat to societal values and interests; The threat is presented in a stylized and stereotypical fashion by the mass media; The novelty of the issue is emphasised in media coverage; The media coverage of the threat is out of all proportion to the actual threat; ‘moral entrepreneurs’ (e. g. academics, editors, politicians, judiciary religious figures, the third sector, police chiefs, etc) present the threat in similar ways in relation to rates, sources of the problem, future potential escalation and solutions; the condition then disappears, submerges or deteriorates or becomes more invisible. (Cohen 1972, Hall et al. 1978)

Key Facts about CSE https: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=b. Lc. S 0 fw. Txg&feature=player_embedded

Key Facts about CSE https: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=b. Lc. S 0 fw. Txg&feature=player_embedded

Definition of CSE ‘In practice, the sexual exploitation of children and young people under 18 might involve young people being coerced, manipulated, forced or deceived into performing and/or others performing on them, sexual activities in exchange for receiving some form of material goods or other entity (for example, food, accommodation, drugs, alcohol, cigarettes, gifts, affection). ’ National Guidance for Child Protection In Scotland 2014

Definition of CSE ‘In practice, the sexual exploitation of children and young people under 18 might involve young people being coerced, manipulated, forced or deceived into performing and/or others performing on them, sexual activities in exchange for receiving some form of material goods or other entity (for example, food, accommodation, drugs, alcohol, cigarettes, gifts, affection). ’ National Guidance for Child Protection In Scotland 2014

Scotland In the last 2 years, there have been a couple of significant publications in Scotland: n CELCIS (2012), based on a small sample of 75 LAC - n 8% were known or confirmed to have experienced CSE during the last year. 21% were suspected, known, or confirmed to have experienced CSE during the last year. Rigby and Murie (2013), case file analysis 39 accommodated children in Glasgow. - 33% C & YP were at substantial risk through sexual exploitation.

Scotland In the last 2 years, there have been a couple of significant publications in Scotland: n CELCIS (2012), based on a small sample of 75 LAC - n 8% were known or confirmed to have experienced CSE during the last year. 21% were suspected, known, or confirmed to have experienced CSE during the last year. Rigby and Murie (2013), case file analysis 39 accommodated children in Glasgow. - 33% C & YP were at substantial risk through sexual exploitation.

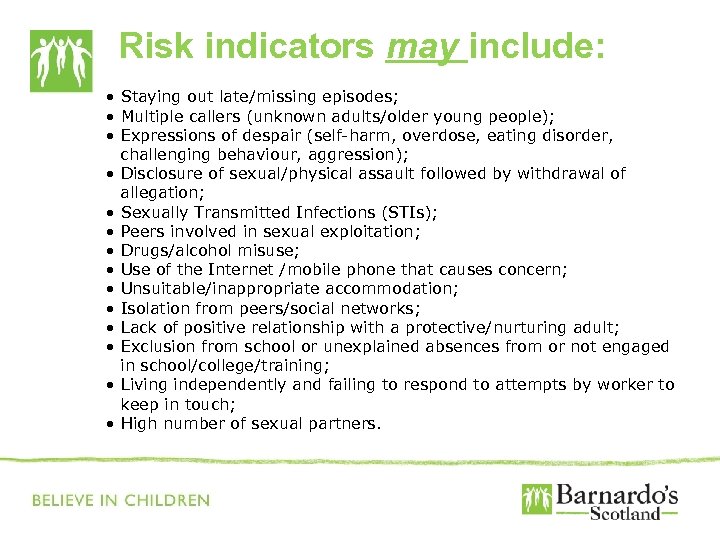

Risk indicators may include: • Staying out late/missing episodes; • Multiple callers (unknown adults/older young people); • Expressions of despair (self-harm, overdose, eating disorder, challenging behaviour, aggression); • Disclosure of sexual/physical assault followed by withdrawal of allegation; • Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs); • Peers involved in sexual exploitation; • Drugs/alcohol misuse; • Use of the Internet /mobile phone that causes concern; • Unsuitable/inappropriate accommodation; • Isolation from peers/social networks; • Lack of positive relationship with a protective/nurturing adult; • Exclusion from school or unexplained absences from or not engaged in school/college/training; • Living independently and failing to respond to attempts by worker to keep in touch; • High number of sexual partners.

Risk indicators may include: • Staying out late/missing episodes; • Multiple callers (unknown adults/older young people); • Expressions of despair (self-harm, overdose, eating disorder, challenging behaviour, aggression); • Disclosure of sexual/physical assault followed by withdrawal of allegation; • Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs); • Peers involved in sexual exploitation; • Drugs/alcohol misuse; • Use of the Internet /mobile phone that causes concern; • Unsuitable/inappropriate accommodation; • Isolation from peers/social networks; • Lack of positive relationship with a protective/nurturing adult; • Exclusion from school or unexplained absences from or not engaged in school/college/training; • Living independently and failing to respond to attempts by worker to keep in touch; • High number of sexual partners.

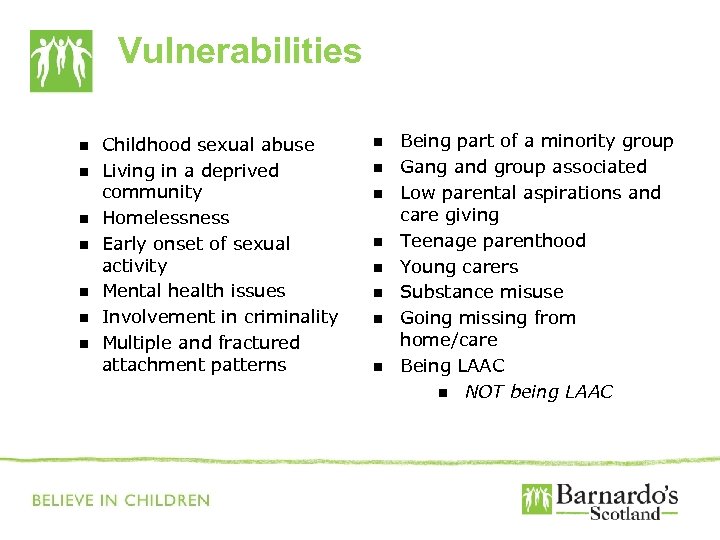

Vulnerabilities n n n n Childhood sexual abuse Living in a deprived community Homelessness Early onset of sexual activity Mental health issues Involvement in criminality Multiple and fractured attachment patterns n n n n Being part of a minority group Gang and group associated Low parental aspirations and care giving Teenage parenthood Young carers Substance misuse Going missing from home/care Being LAAC n NOT being LAAC

Vulnerabilities n n n n Childhood sexual abuse Living in a deprived community Homelessness Early onset of sexual activity Mental health issues Involvement in criminality Multiple and fractured attachment patterns n n n n Being part of a minority group Gang and group associated Low parental aspirations and care giving Teenage parenthood Young carers Substance misuse Going missing from home/care Being LAAC n NOT being LAAC

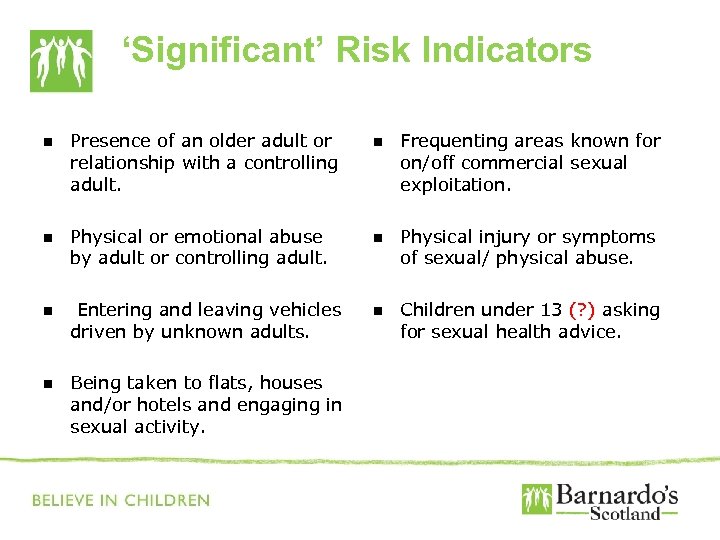

‘Significant’ Risk Indicators n Presence of an older adult or relationship with a controlling adult. n Frequenting areas known for on/off commercial sexual exploitation. n Physical or emotional abuse by adult or controlling adult. n Physical injury or symptoms of sexual/ physical abuse. n Entering and leaving vehicles driven by unknown adults. n Children under 13 (? ) asking for sexual health advice. n Being taken to flats, houses and/or hotels and engaging in sexual activity.

‘Significant’ Risk Indicators n Presence of an older adult or relationship with a controlling adult. n Frequenting areas known for on/off commercial sexual exploitation. n Physical or emotional abuse by adult or controlling adult. n Physical injury or symptoms of sexual/ physical abuse. n Entering and leaving vehicles driven by unknown adults. n Children under 13 (? ) asking for sexual health advice. n Being taken to flats, houses and/or hotels and engaging in sexual activity.

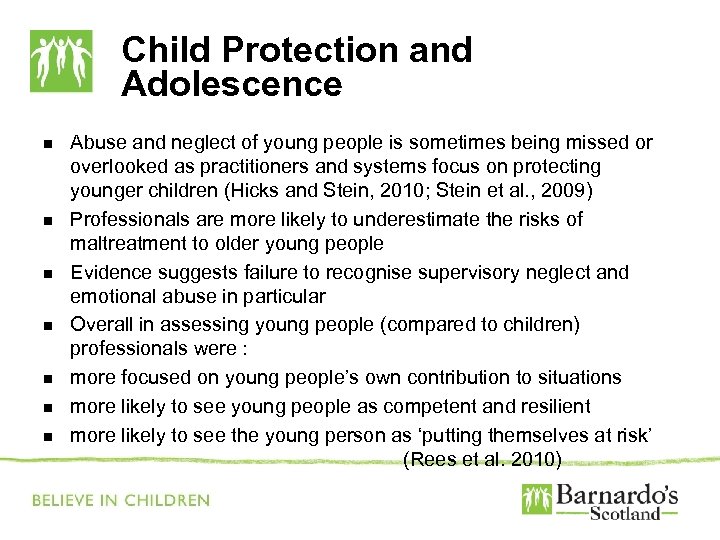

Child Protection and Adolescence n n n n Abuse and neglect of young people is sometimes being missed or overlooked as practitioners and systems focus on protecting younger children (Hicks and Stein, 2010; Stein et al. , 2009) Professionals are more likely to underestimate the risks of maltreatment to older young people Evidence suggests failure to recognise supervisory neglect and emotional abuse in particular Overall in assessing young people (compared to children) professionals were : more focused on young people’s own contribution to situations more likely to see young people as competent and resilient more likely to see the young person as ‘putting themselves at risk’ (Rees et al. 2010)

Child Protection and Adolescence n n n n Abuse and neglect of young people is sometimes being missed or overlooked as practitioners and systems focus on protecting younger children (Hicks and Stein, 2010; Stein et al. , 2009) Professionals are more likely to underestimate the risks of maltreatment to older young people Evidence suggests failure to recognise supervisory neglect and emotional abuse in particular Overall in assessing young people (compared to children) professionals were : more focused on young people’s own contribution to situations more likely to see young people as competent and resilient more likely to see the young person as ‘putting themselves at risk’ (Rees et al. 2010)

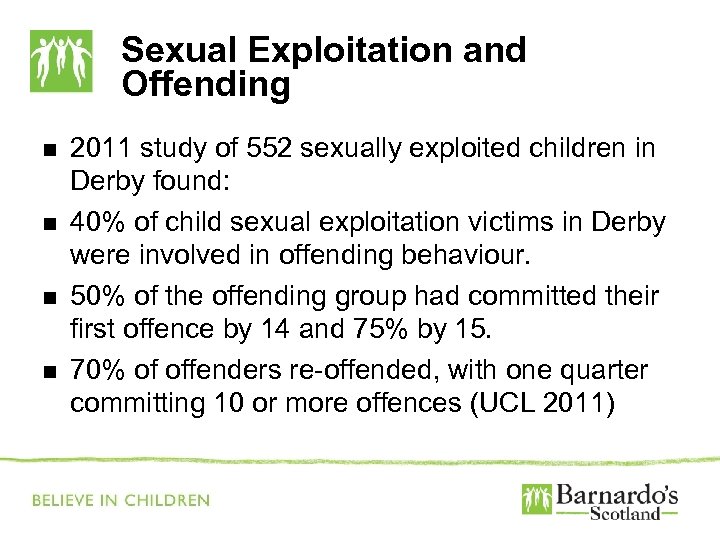

Sexual Exploitation and Offending n n 2011 study of 552 sexually exploited children in Derby found: 40% of child sexual exploitation victims in Derby were involved in offending behaviour. 50% of the offending group had committed their first offence by 14 and 75% by 15. 70% of offenders re-offended, with one quarter committing 10 or more offences (UCL 2011)

Sexual Exploitation and Offending n n 2011 study of 552 sexually exploited children in Derby found: 40% of child sexual exploitation victims in Derby were involved in offending behaviour. 50% of the offending group had committed their first offence by 14 and 75% by 15. 70% of offenders re-offended, with one quarter committing 10 or more offences (UCL 2011)

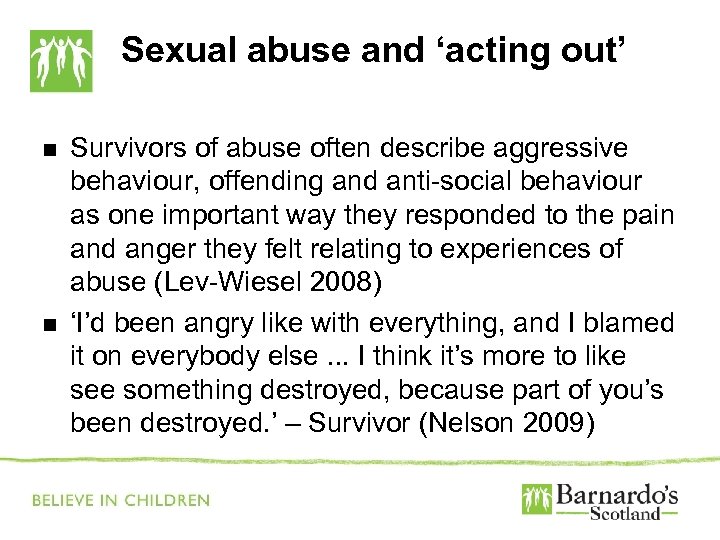

Sexual abuse and ‘acting out’ n n Survivors of abuse often describe aggressive behaviour, offending and anti-social behaviour as one important way they responded to the pain and anger they felt relating to experiences of abuse (Lev-Wiesel 2008) ‘I’d been angry like with everything, and I blamed it on everybody else. . . I think it’s more to like see something destroyed, because part of you’s been destroyed. ’ – Survivor (Nelson 2009)

Sexual abuse and ‘acting out’ n n Survivors of abuse often describe aggressive behaviour, offending and anti-social behaviour as one important way they responded to the pain and anger they felt relating to experiences of abuse (Lev-Wiesel 2008) ‘I’d been angry like with everything, and I blamed it on everybody else. . . I think it’s more to like see something destroyed, because part of you’s been destroyed. ’ – Survivor (Nelson 2009)

The Links between Crime and Sexual Exploitation ‘Girls (who experience sexual exploitation)will use crime as a resource to make themselves safe, knowing that in being arrested, they will be removed from the situation in which they find themselves, for example, shoplifting in front of security guards. Some offending is also a means by which girls and young women obtain a measure of justice for the crimes committed against them. The most common story recounted by practitioners across the country was one in which a young woman would commit criminal damage against the property of her exploiters. ’ (Phoenix 2012)

The Links between Crime and Sexual Exploitation ‘Girls (who experience sexual exploitation)will use crime as a resource to make themselves safe, knowing that in being arrested, they will be removed from the situation in which they find themselves, for example, shoplifting in front of security guards. Some offending is also a means by which girls and young women obtain a measure of justice for the crimes committed against them. The most common story recounted by practitioners across the country was one in which a young woman would commit criminal damage against the property of her exploiters. ’ (Phoenix 2012)

…. boys and young men? n significant differences between male and female service users in terms of youth offending: 48% of males had a youth offending record, compared with 28% of females (Cockbain et al, 2014). n young males involved in criminal activity may be viewed as a potential risk to others rather than – as would be the case with females– their criminal behaviour being assessed as an indicator of other vulnerabilities such as experiencing CSE (Mc. Naughton Nicholls et al, 2014). n Self-harm: males may express their anger externally, and self harm in different ways from females as a response to CSE. For example, males may intentionally provoke a fight as a means of sustaining an injury, which may not be recognised by adults as a method of self-harm. (Mc. Naughton Nicholls et al, 2014). n

…. boys and young men? n significant differences between male and female service users in terms of youth offending: 48% of males had a youth offending record, compared with 28% of females (Cockbain et al, 2014). n young males involved in criminal activity may be viewed as a potential risk to others rather than – as would be the case with females– their criminal behaviour being assessed as an indicator of other vulnerabilities such as experiencing CSE (Mc. Naughton Nicholls et al, 2014). n Self-harm: males may express their anger externally, and self harm in different ways from females as a response to CSE. For example, males may intentionally provoke a fight as a means of sustaining an injury, which may not be recognised by adults as a method of self-harm. (Mc. Naughton Nicholls et al, 2014). n

High Profile Cases ROTHERHAM Manchester Rochale Oxford Sheffield Bristol Birmingham Derby London And Edinburgh, Glasgow….

High Profile Cases ROTHERHAM Manchester Rochale Oxford Sheffield Bristol Birmingham Derby London And Edinburgh, Glasgow….

Discussion point… n n What does practice with children involved with sexual exploitation look like at a time when this issue now has a significant media profile? Are our practice and organizational responses to this issue proportionate?

Discussion point… n n What does practice with children involved with sexual exploitation look like at a time when this issue now has a significant media profile? Are our practice and organizational responses to this issue proportionate?

…moving forward? “The same patterns of abuse are seen, the same views of victims and parents, and similar long lead-ins before effective intervention. For all these everywhere to be the result of inept, uncaring and weak staff, and leaders who need to go seems highly improbable. The overall failings were those of lack of knowledge and understanding around a concept (of CSE) that few understood and where few knew how it could be tackled, but also organisational weaknesses which prevented the true picture from being seen. It is important this is recognised so organisations can, and continue to, get it right on CSE, and can respond better when the next new challenge occurs. ” Alan Bedford, Forward, SCR into CSE in Oxfordshire, para. V.

…moving forward? “The same patterns of abuse are seen, the same views of victims and parents, and similar long lead-ins before effective intervention. For all these everywhere to be the result of inept, uncaring and weak staff, and leaders who need to go seems highly improbable. The overall failings were those of lack of knowledge and understanding around a concept (of CSE) that few understood and where few knew how it could be tackled, but also organisational weaknesses which prevented the true picture from being seen. It is important this is recognised so organisations can, and continue to, get it right on CSE, and can respond better when the next new challenge occurs. ” Alan Bedford, Forward, SCR into CSE in Oxfordshire, para. V.

What we need to do https: //www. youtube. com/watch? feature=player_e mbedded&v=75 T_bg. Sg. W 8 k

What we need to do https: //www. youtube. com/watch? feature=player_e mbedded&v=75 T_bg. Sg. W 8 k