799a0e16a1bb9dc271ee4656c831525f.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 95

Chemistry: A Molecular Approach, 2 nd Ed. By Nivaldo Tro Chapter 19 Radioactivity and Nuclear Chemistry Roy Kennedy Massachusetts Bay Community College Wellesley Hills, MA Copyright 2011 Pearson Education, Inc.

The Discovery of Radioactivity • Phosphorescence is the long-lived • emission of light by atoms or molecules that sometimes occurs after they absorb light Antoine-Henri Becquerel designed an experiment to determine if phosphorescent minerals gave off X-rays ü Becquerel observed that only some phosphorescent materials produced penetrating rays ü While certain other minerals were constantly producing energy rays that could penetrate matter Ø The rays behaved like X-rays ü He determined that all minerals that contained uranium produced “uranic rays” even though the minerals were not exposed to outside energy 2

The Discovery of Radioactivity Marie Curie • X-rays were detected by their ability to • penetrate matter and expose a photographic plate Marie Curie broke down the minerals and used an electroscope to detect the source of the uranic rays ü she found that rays were emitted from uranium and other elements ü Some of which were new elements, e. g. Ø radium named for its green phosphorescence Ø polonium named for her homeland, Poland. • Because the rays were no longer just a property of uranium, she called the rays radioactivity 3

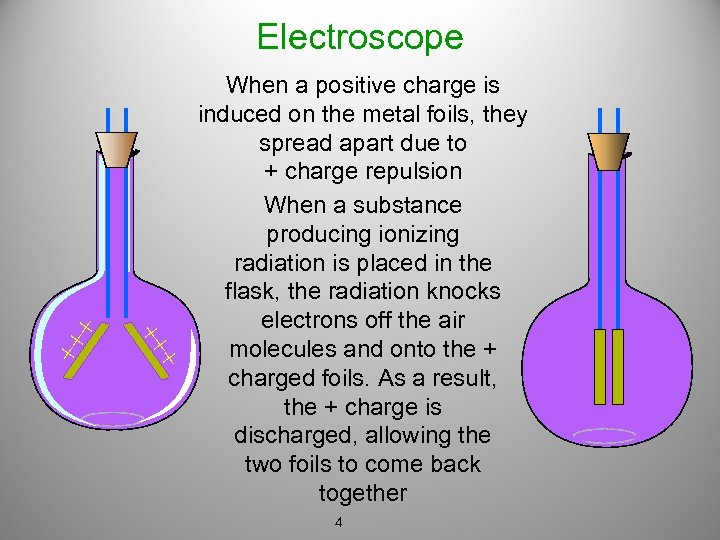

++ + Electroscope When a positive charge is induced on the metal foils, they spread apart due to + charge repulsion When a substance producing ionizing radiation is placed in the flask, the radiation knocks electrons off the air molecules and onto the + charged foils. As a result, the + charge is discharged, allowing the two foils to come back together 4

Other Properties of Radioactivity • Radioactive rays can ionize matter, and ü can cause uncharged matter to become charged Ø basis of Geiger Counter and electroscope • Radioactive rays üare high energy ücan penetrate matter ücan cause chemicals to phosphoresce Ø basis of scintillation counter 5

What Is Radioactivity? • Radioactivity is the release of tiny, highenergy particles or gamma rays from an atom • Particles are ejected from the nucleus 6

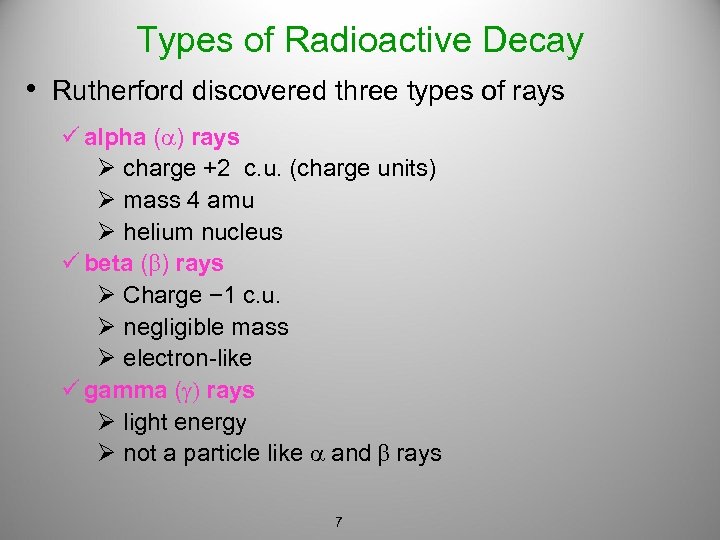

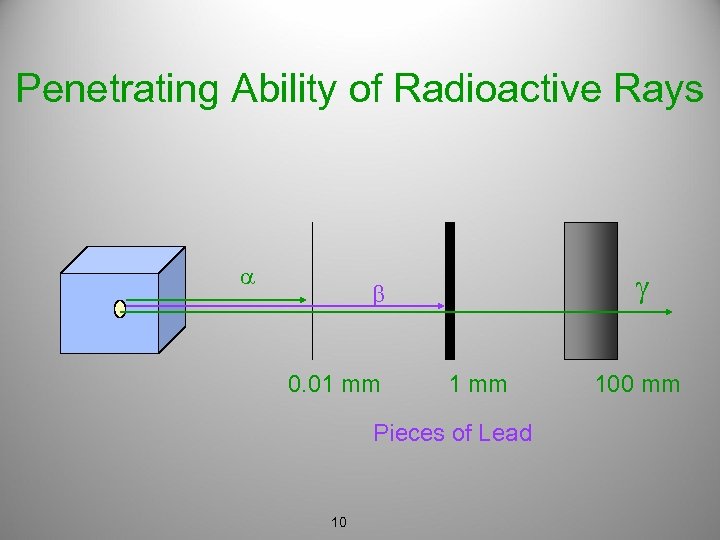

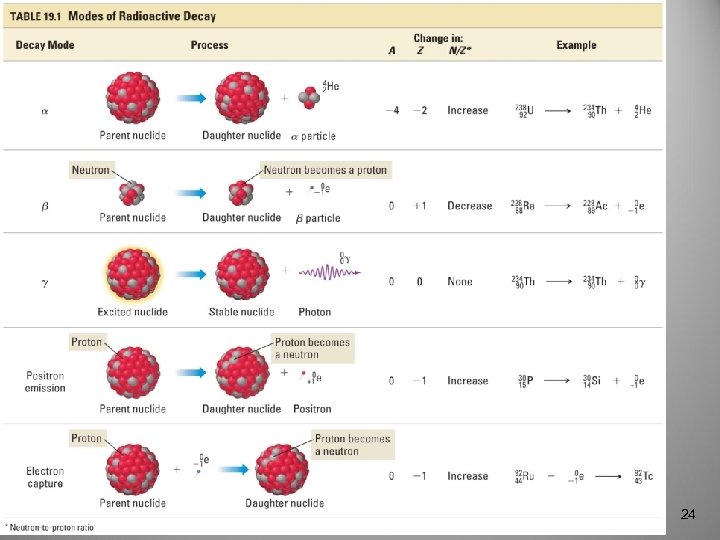

Types of Radioactive Decay • Rutherford discovered three types of rays ü alpha ( ) rays Ø charge +2 c. u. (charge units) Ø mass 4 amu Ø helium nucleus ü beta ( ) rays Ø Charge − 1 c. u. Ø negligible mass Ø electron-like ü gamma (g) rays Ø light energy Ø not a particle like and rays 7

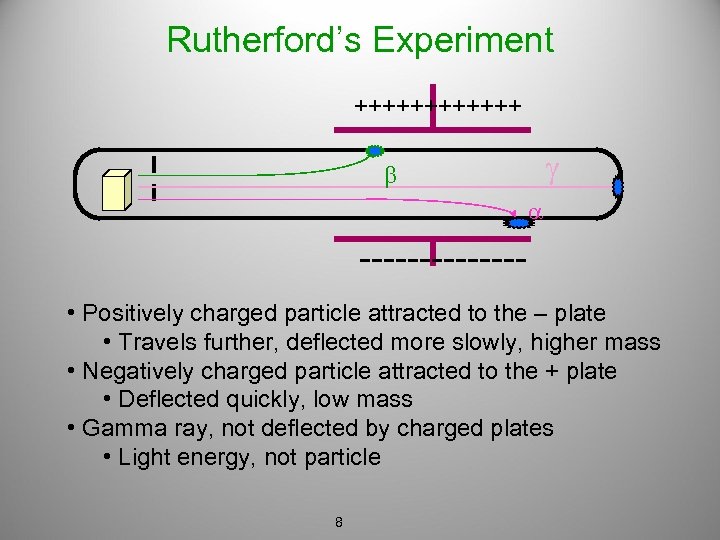

Rutherford’s Experiment ++++++ g ------- • Positively charged particle attracted to the – plate • Travels further, deflected more slowly, higher mass • Negatively charged particle attracted to the + plate • Deflected quickly, low mass • Gamma ray, not deflected by charged plates • Light energy, not particle 8

Types of Radioactive Decay In addition, some unstable nuclei can • Emit Positrons ü a positively charged electron • Undergo Electron capture ü low energy electron pulled into the nucleus 9

Penetrating Ability of Radioactive Rays g 0. 01 mm 100 mm Pieces of Lead 10

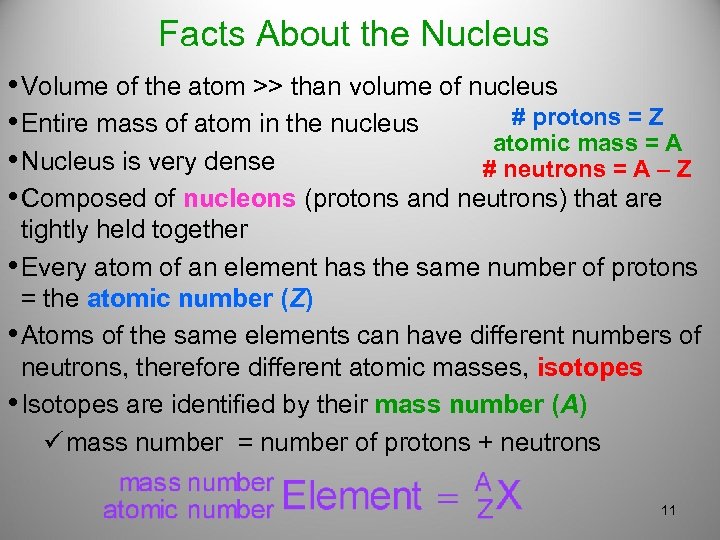

Facts About the Nucleus • Volume of the atom >> than volume of nucleus # protons = Z • Entire mass of atom in the nucleus atomic mass = A • Nucleus is very dense # neutrons = A – Z • Composed of nucleons (protons and neutrons) that are tightly held together • Every atom of an element has the same number of protons = the atomic number (Z) • Atoms of the same elements can have different numbers of neutrons, therefore different atomic masses, isotopes • Isotopes are identified by their mass number (A) ü mass number = number of protons + neutrons 11

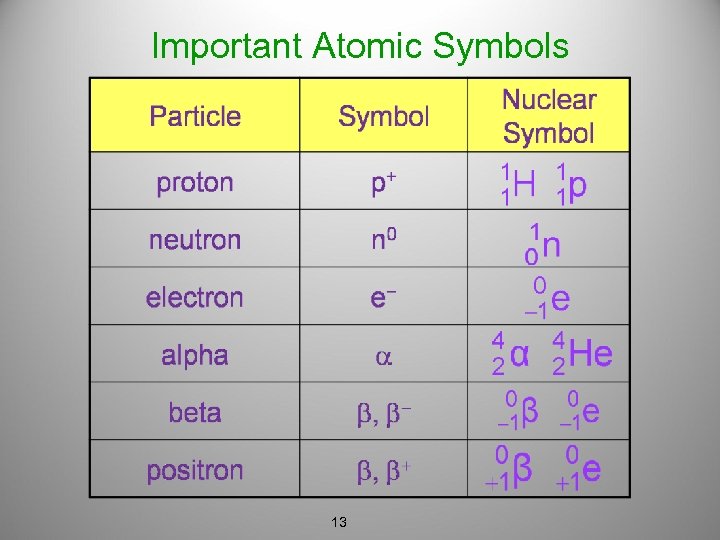

Radioactivity • The nucleus of an isotope is called a nuclide ü All nuclides with 84 or more protons are radioactive ü >90% of known nuclides are radioactive, i. e. radionuclides which are unstable and decompose Ø radioactive decay, which involves the nuclide emitting a particle and/or energy • The radioactive nucleus, the parent nuclide, • spontaneously decomposes into smaller nucleus, the daughter nuclide Each nuclide is identified by a symbol 12

Important Atomic Symbols 13

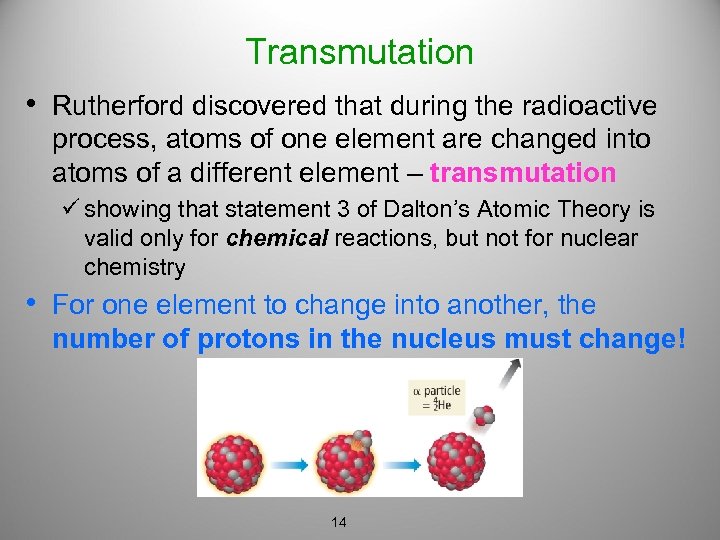

Transmutation • Rutherford discovered that during the radioactive process, atoms of one element are changed into atoms of a different element – transmutation ü showing that statement 3 of Dalton’s Atomic Theory is valid only for chemical reactions, but not for nuclear chemistry • For one element to change into another, the number of protons in the nucleus must change! 14

Chemical Processes vs. Nuclear Processes • Chemical reactions involve changes in the electronic structure of the atom ü atoms gain, lose, or share electrons ü no change in the nuclei occurs • Nuclear reactions involve changes in the structure of the nucleus ü when the number of protons in the nucleus changes, the atom becomes a different element 15

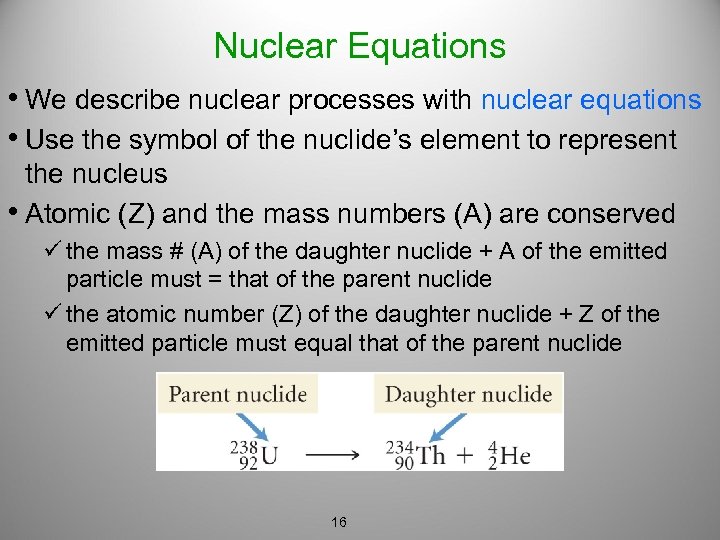

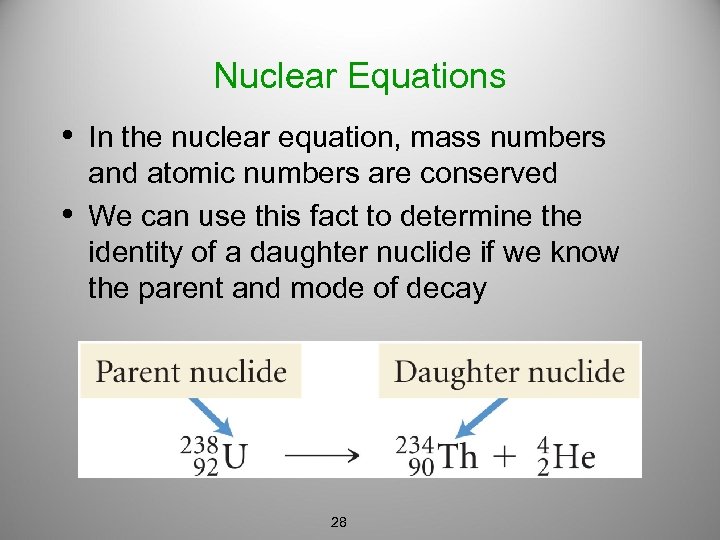

Nuclear Equations • We describe nuclear processes with nuclear equations • Use the symbol of the nuclide’s element to represent the nucleus • Atomic (Z) and the mass numbers (A) are conserved ü the mass # (A) of the daughter nuclide + A of the emitted particle must = that of the parent nuclide ü the atomic number (Z) of the daughter nuclide + Z of the emitted particle must equal that of the parent nuclide 16

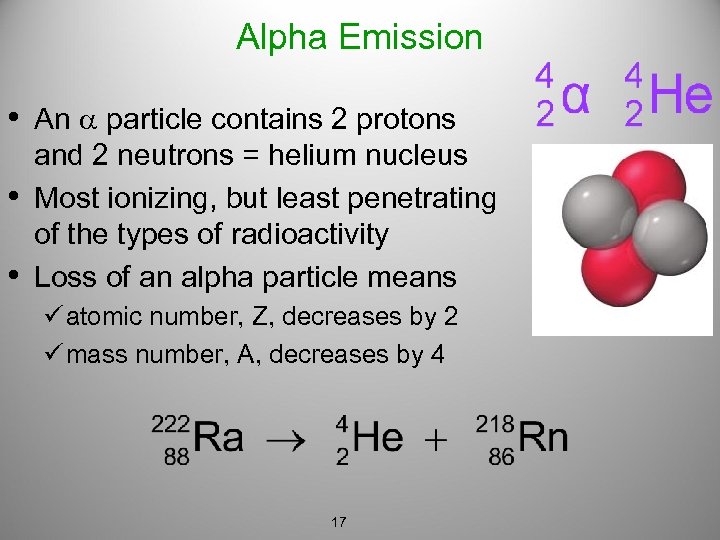

Alpha Emission • An particle contains 2 protons • • and 2 neutrons = helium nucleus Most ionizing, but least penetrating of the types of radioactivity Loss of an alpha particle means ü atomic number, Z, decreases by 2 ü mass number, A, decreases by 4 17

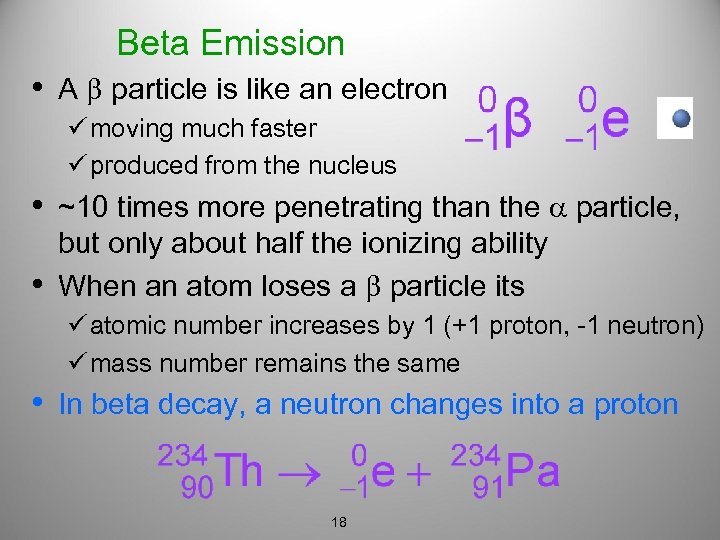

Beta Emission • A particle is like an electron ü moving much faster ü produced from the nucleus • ~10 times more penetrating than the particle, • but only about half the ionizing ability When an atom loses a particle its ü atomic number increases by 1 (+1 proton, -1 neutron) ü mass number remains the same • In beta decay, a neutron changes into a proton 18

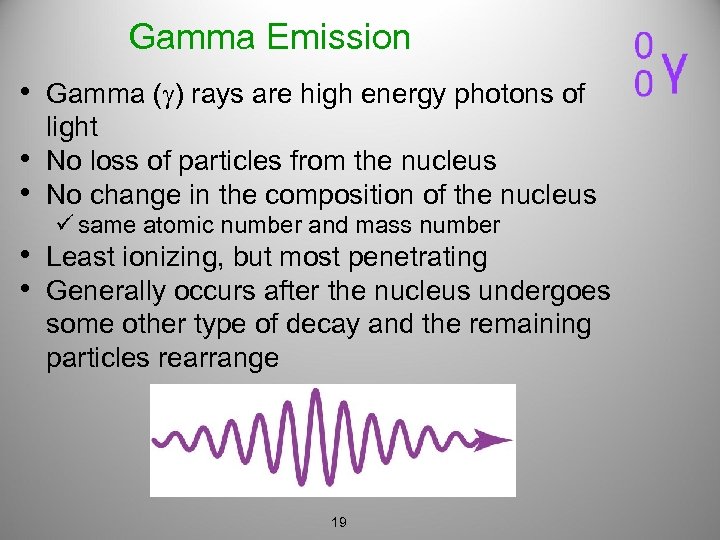

Gamma Emission • Gamma (g) rays are high energy photons of • • light No loss of particles from the nucleus No change in the composition of the nucleus ü same atomic number and mass number • Least ionizing, but most penetrating • Generally occurs after the nucleus undergoes some other type of decay and the remaining particles rearrange 19

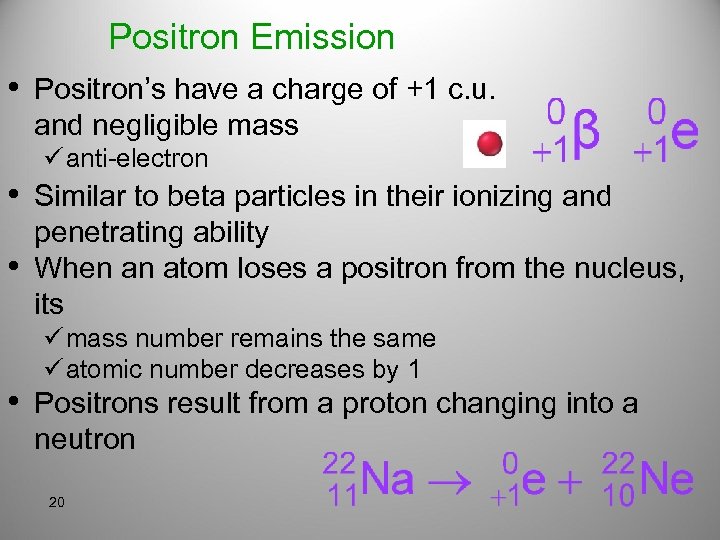

Positron Emission • Positron’s have a charge of +1 c. u. and negligible mass ü anti-electron • Similar to beta particles in their ionizing and • penetrating ability When an atom loses a positron from the nucleus, its ü mass number remains the same ü atomic number decreases by 1 • Positrons result from a proton changing into a neutron 20

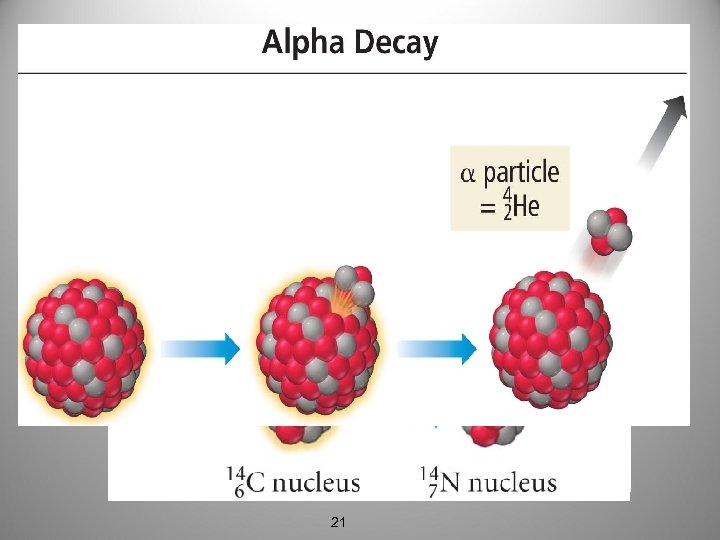

21

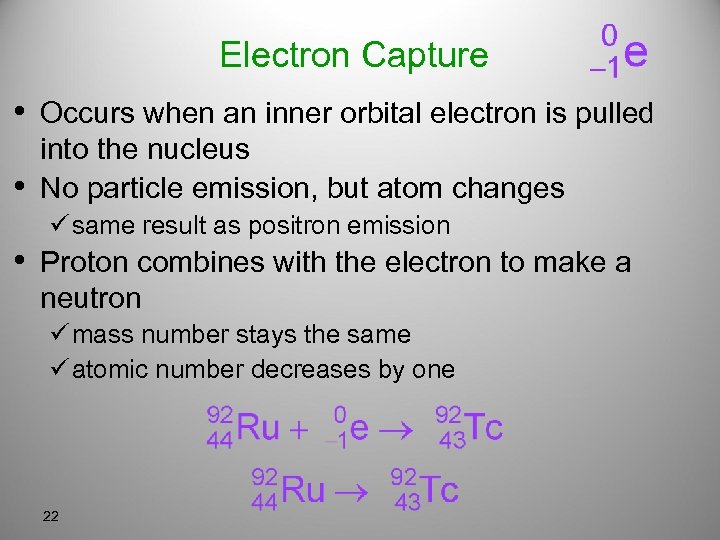

Electron Capture • Occurs when an inner orbital electron is pulled • into the nucleus No particle emission, but atom changes ü same result as positron emission • Proton combines with the electron to make a neutron ü mass number stays the same ü atomic number decreases by one 22

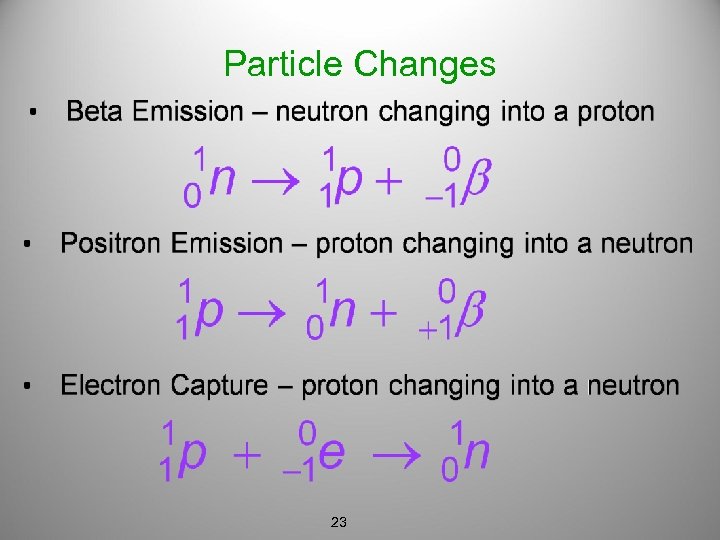

Particle Changes 23

24

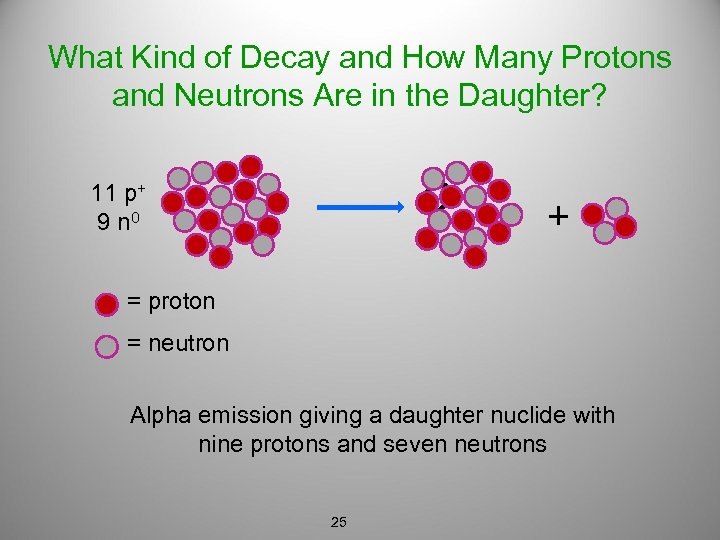

What Kind of Decay and How Many Protons and Neutrons Are in the Daughter? ? + 11 p+ 9 n 0 = proton = neutron Alpha emission giving a daughter nuclide with nine protons and seven neutrons 25

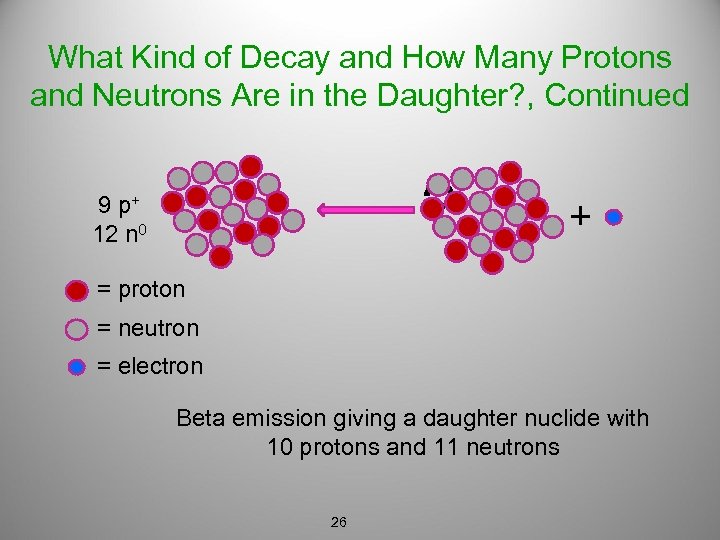

What Kind of Decay and How Many Protons and Neutrons Are in the Daughter? , Continued ? + 9 p+ 12 n 0 = proton = neutron = electron Beta emission giving a daughter nuclide with 10 protons and 11 neutrons 26

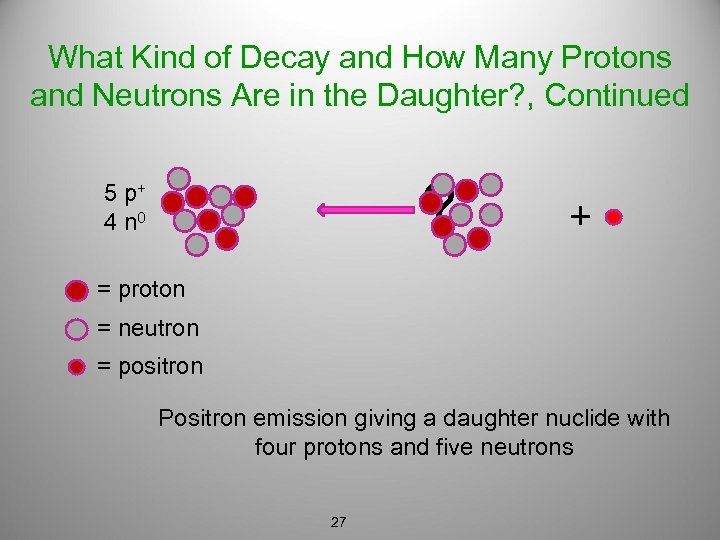

What Kind of Decay and How Many Protons and Neutrons Are in the Daughter? , Continued ? + 5 p+ 4 n 0 = proton = neutron = positron Positron emission giving a daughter nuclide with four protons and five neutrons 27

Nuclear Equations • In the nuclear equation, mass numbers • and atomic numbers are conserved We can use this fact to determine the identity of a daughter nuclide if we know the parent and mode of decay 28

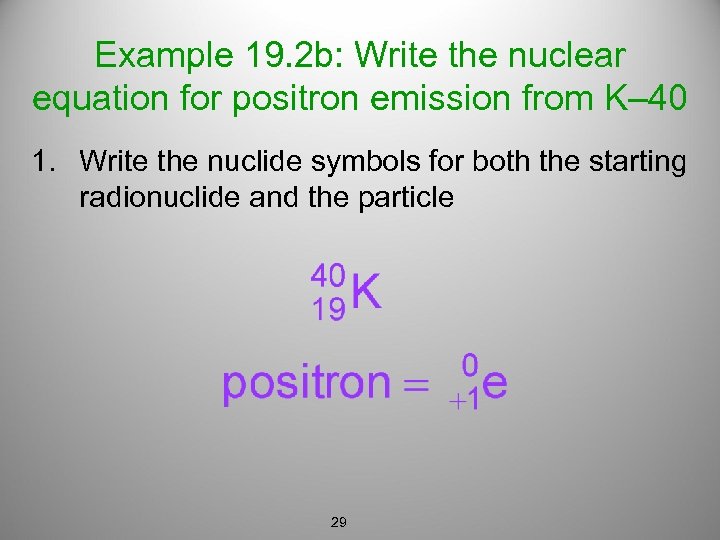

Example 19. 2 b: Write the nuclear equation for positron emission from K– 40 1. Write the nuclide symbols for both the starting radionuclide and the particle 29

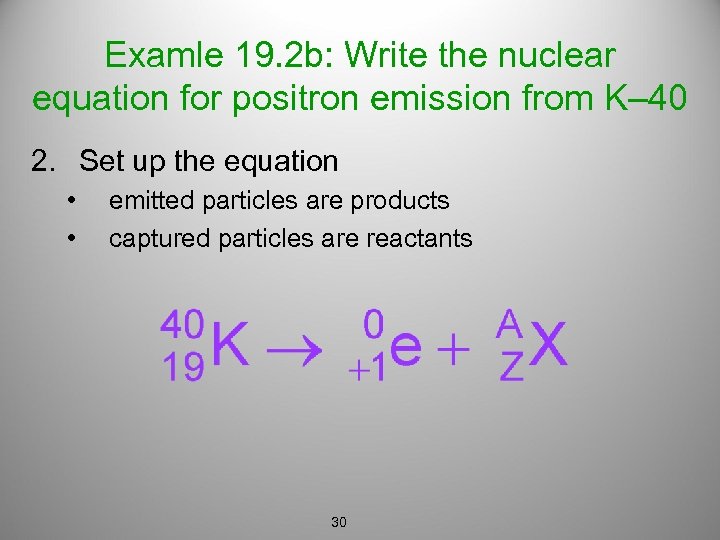

Examle 19. 2 b: Write the nuclear equation for positron emission from K– 40 2. Set up the equation • • emitted particles are products captured particles are reactants 30

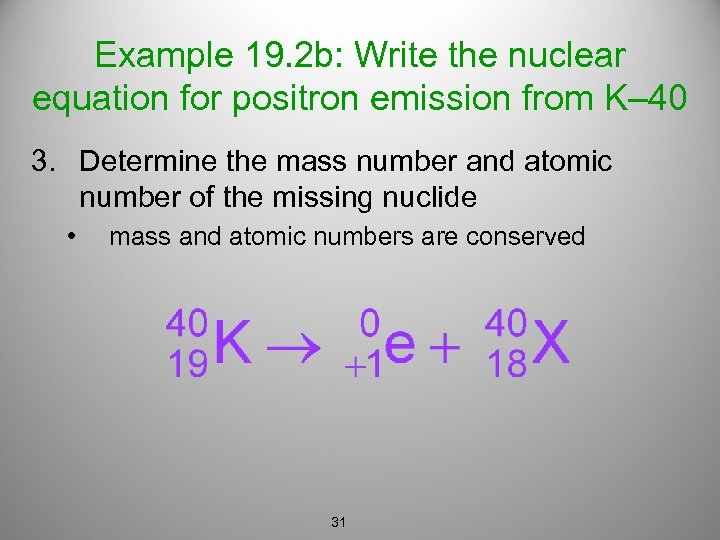

Example 19. 2 b: Write the nuclear equation for positron emission from K– 40 3. Determine the mass number and atomic number of the missing nuclide • mass and atomic numbers are conserved 31

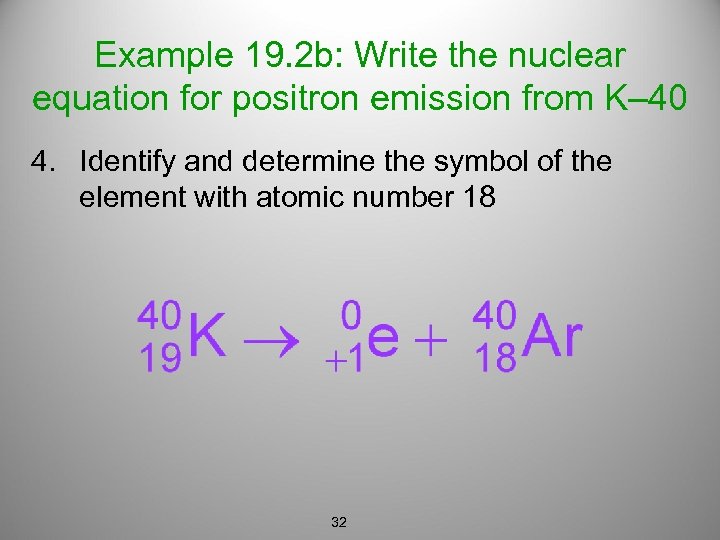

Example 19. 2 b: Write the nuclear equation for positron emission from K– 40 4. Identify and determine the symbol of the element with atomic number 18 32

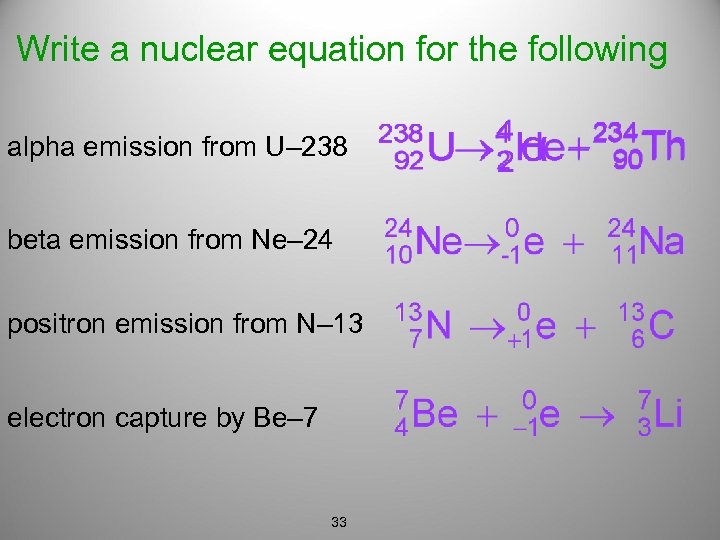

Write a nuclear equation for the following alpha emission from U– 238 beta emission from Ne– 24 positron emission from N– 13 electron capture by Be– 7 33

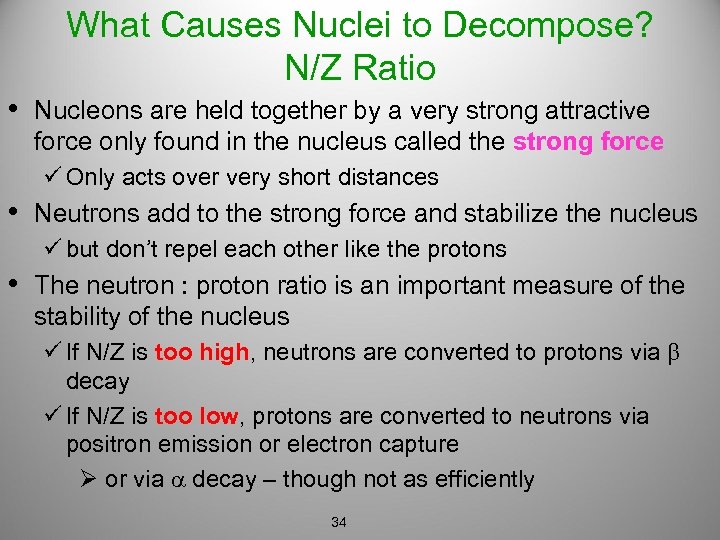

What Causes Nuclei to Decompose? N/Z Ratio • Nucleons are held together by a very strong attractive force only found in the nucleus called the strong force ü Only acts over very short distances • Neutrons add to the strong force and stabilize the nucleus ü but don’t repel each other like the protons • The neutron : proton ratio is an important measure of the stability of the nucleus ü If N/Z is too high, neutrons are converted to protons via decay ü If N/Z is too low, protons are converted to neutrons via positron emission or electron capture Ø or via decay – though not as efficiently 34

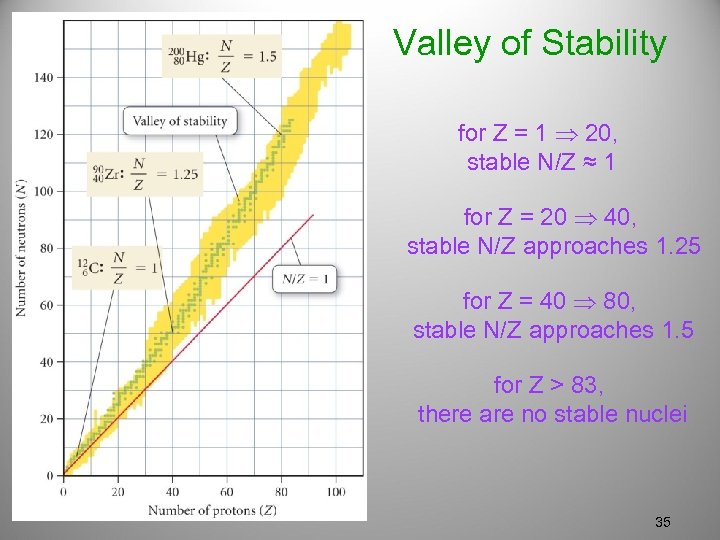

Valley of Stability for Z = 1 20, stable N/Z ≈ 1 for Z = 20 40, stable N/Z approaches 1. 25 for Z = 40 80, stable N/Z approaches 1. 5 for Z > 83, there are no stable nuclei 35

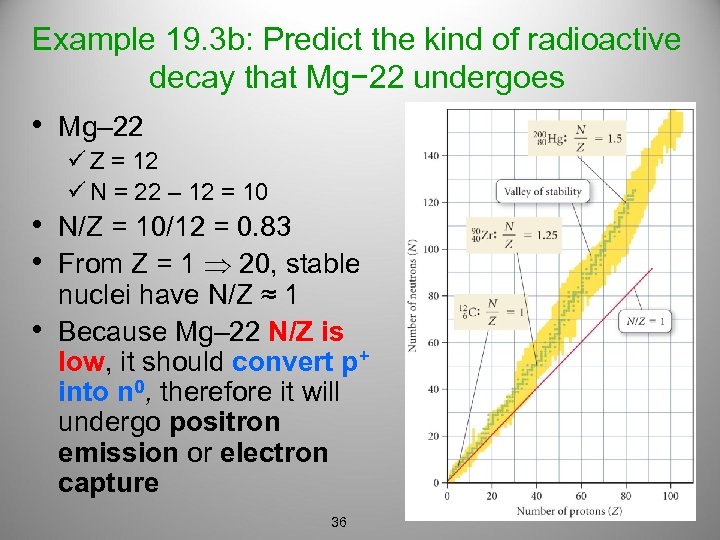

Example 19. 3 b: Predict the kind of radioactive decay that Mg− 22 undergoes • Mg– 22 ü Z = 12 ü N = 22 – 12 = 10 • N/Z = 10/12 = 0. 83 • From Z = 1 20, stable • nuclei have N/Z ≈ 1 Because Mg– 22 N/Z is low, it should convert p+ into n 0, therefore it will undergo positron emission or electron capture 36

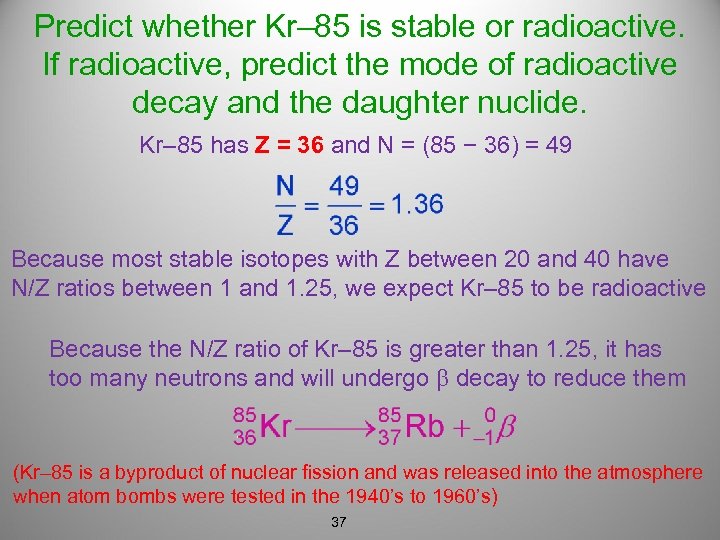

Predict whether Kr– 85 is stable or radioactive. If radioactive, predict the mode of radioactive decay and the daughter nuclide. Kr– 85 has Z = 36 and N = (85 − 36) = 49 Because most stable isotopes with Z between 20 and 40 have N/Z ratios between 1 and 1. 25, we expect Kr– 85 to be radioactive Because the N/Z ratio of Kr– 85 is greater than 1. 25, it has too many neutrons and will undergo decay to reduce them (Kr– 85 is a byproduct of nuclear fission and was released into the atmosphere when atom bombs were tested in the 1940’s to 1960’s) 37

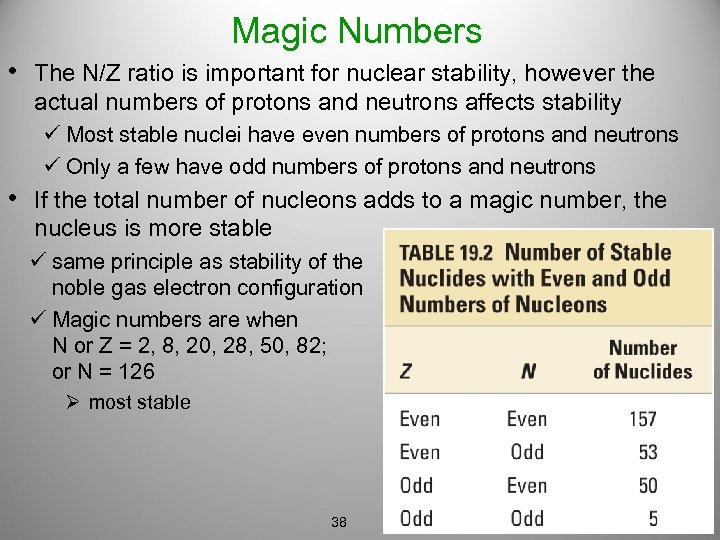

Magic Numbers • The N/Z ratio is important for nuclear stability, however the actual numbers of protons and neutrons affects stability ü Most stable nuclei have even numbers of protons and neutrons ü Only a few have odd numbers of protons and neutrons • If the total number of nucleons adds to a magic number, the nucleus is more stable ü same principle as stability of the noble gas electron configuration ü Magic numbers are when N or Z = 2, 8, 20, 28, 50, 82; or N = 126 Ø most stable 38

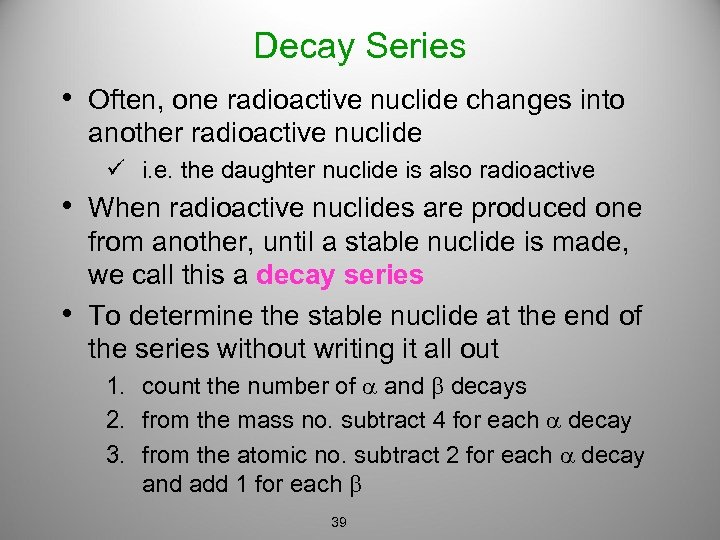

Decay Series • Often, one radioactive nuclide changes into another radioactive nuclide ü i. e. the daughter nuclide is also radioactive • When radioactive nuclides are produced one • from another, until a stable nuclide is made, we call this a decay series To determine the stable nuclide at the end of the series without writing it all out 1. count the number of and decays 2. from the mass no. subtract 4 for each decay 3. from the atomic no. subtract 2 for each decay and add 1 for each 39

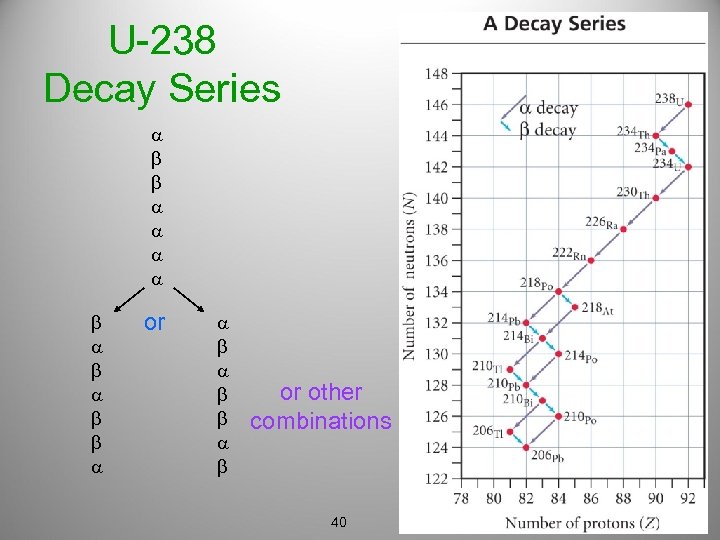

U-238 Decay Series or other combinations 40

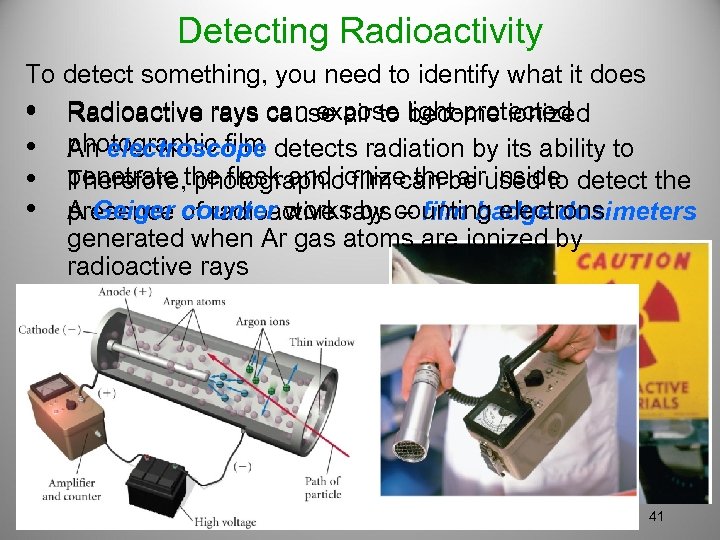

Detecting Radioactivity To detect something, you need to identify what it does • Radioactive rays cause air to become ionized Radioactive rays can expose light-protected • photographic film An electroscope detects radiation by its ability to • penetrate the flask and ionize the air inside Therefore, photographic film can be used to detect the • A Geiger counter works by counting electrons presence of radioactive rays – film badge dosimeters generated when Ar gas atoms are ionized by radioactive rays 41

Detecting Radioactivity • Radioactive rays cause certain chemicals to • give off a flash of light when they strike the chemical A scintillation counter is able to count the number of flashes per minute Natural Radioactivity • There are small amounts of radioactive • minerals in the air, ground, water, and even in the food you eat! The radiation you are exposed to from natural sources is called background radiation 42

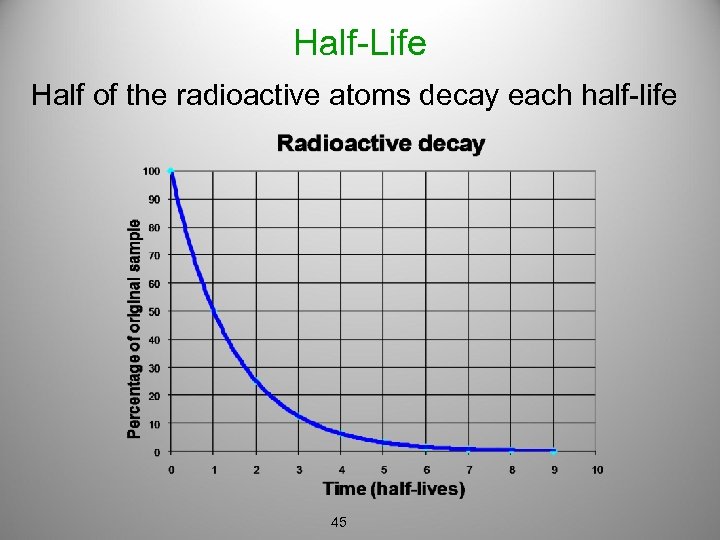

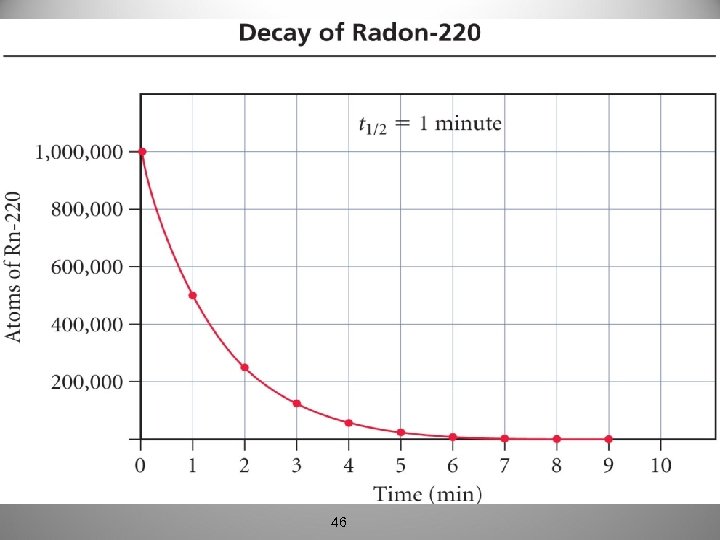

Rate of Radioactive Decay • The rate of change in the amount of radioactivity is constant, and different for each radioactive “isotope” ü change in radioactivity measured with a Geiger counter • Each radionuclide had a particular length of time required to lose half its radioactivity ü a constant half-life, which means it follows first order kinetic rate laws • The rate of radioactive change is not affected by temperature ü meaning radioactivity is not a chemical reaction! 43

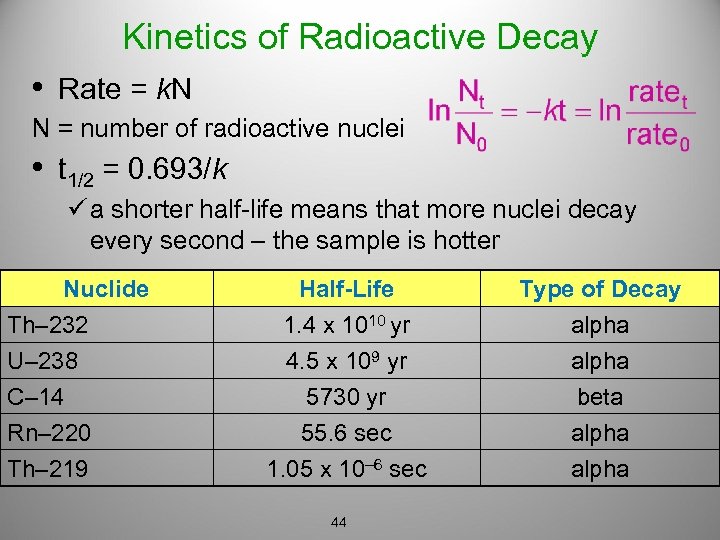

Kinetics of Radioactive Decay • Rate = k. N N = number of radioactive nuclei • t 1/2 = 0. 693/k ü a shorter half-life means that more nuclei decay every second – the sample is hotter Nuclide Th– 232 U– 238 C– 14 Rn– 220 Th– 219 Half-Life 1. 4 x 1010 yr 4. 5 x 109 yr 5730 yr 55. 6 sec 1. 05 x 10– 6 sec 44 Type of Decay alpha beta alpha

Half-Life Half of the radioactive atoms decay each half-life 45

46

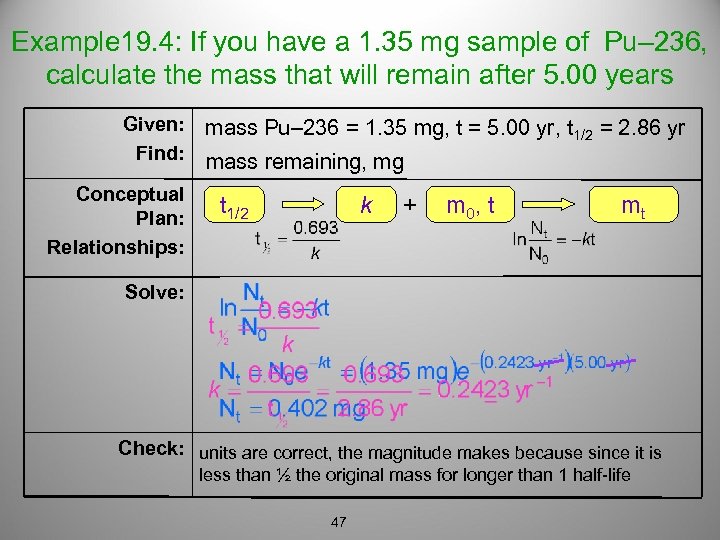

Example 19. 4: If you have a 1. 35 mg sample of Pu– 236, calculate the mass that will remain after 5. 00 years Given: Find: Conceptual Plan: Relationships: mass Pu– 236 = 1. 35 mg, t = 5. 00 yr, t 1/2 = 2. 86 yr mass remaining, mg t 1/2 k + m 0, t mt Solve: Check: units are correct, the magnitude makes because since it is less than ½ the original mass for longer than 1 half-life 47

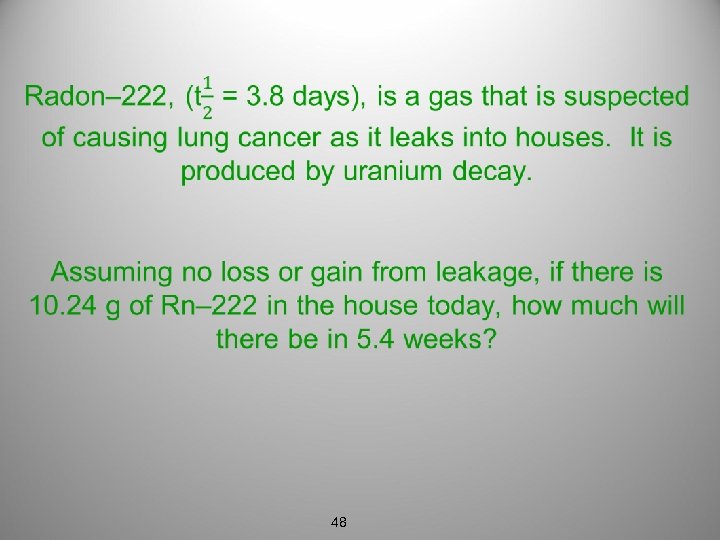

48

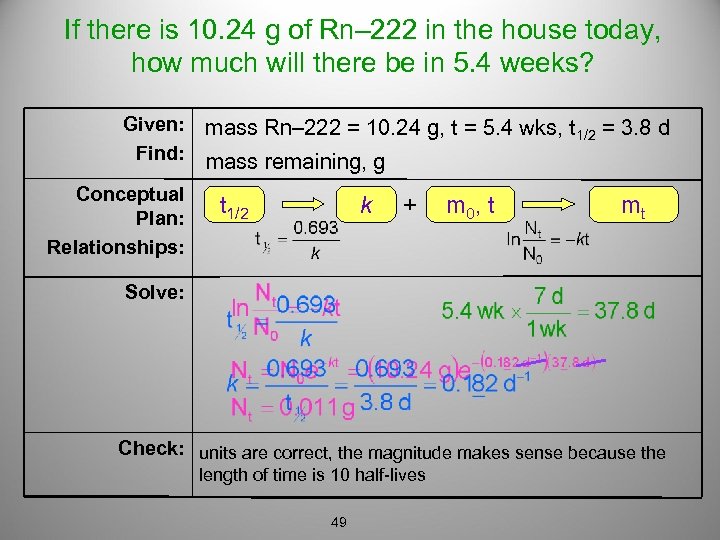

If there is 10. 24 g of Rn– 222 in the house today, how much will there be in 5. 4 weeks? Given: Find: Conceptual Plan: Relationships: mass Rn– 222 = 10. 24 g, t = 5. 4 wks, t 1/2 = 3. 8 d mass remaining, g t 1/2 k + m 0, t mt Solve: Check: units are correct, the magnitude makes sense because the length of time is 10 half-lives 49

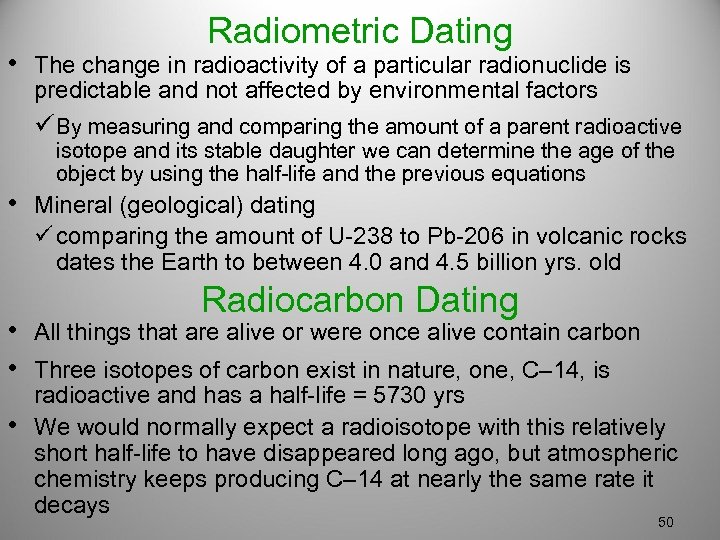

Radiometric Dating • The change in radioactivity of a particular radionuclide is predictable and not affected by environmental factors üBy measuring and comparing the amount of a parent radioactive isotope and its stable daughter we can determine the age of the object by using the half-life and the previous equations • Mineral (geological) dating ü comparing the amount of U-238 to Pb-206 in volcanic rocks dates the Earth to between 4. 0 and 4. 5 billion yrs. old Radiocarbon Dating • All things that are alive or were once alive contain carbon • Three isotopes of carbon exist in nature, one, C– 14, is • radioactive and has a half-life = 5730 yrs We would normally expect a radioisotope with this relatively short half-life to have disappeared long ago, but atmospheric chemistry keeps producing C– 14 at nearly the same rate it decays 50

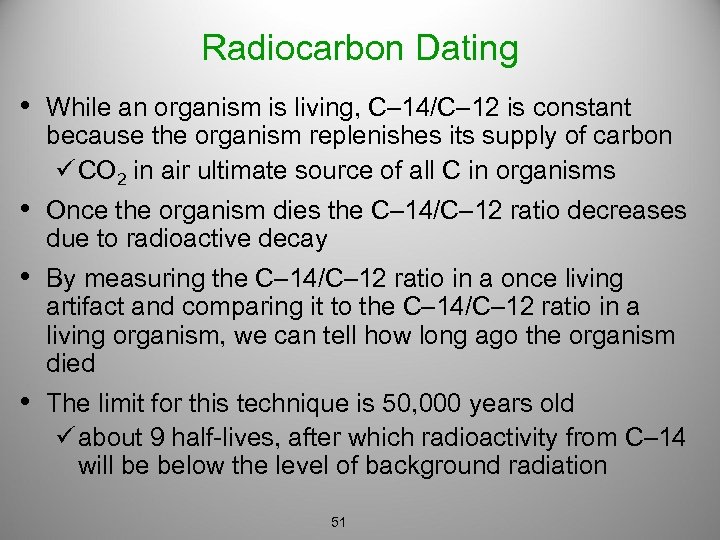

Radiocarbon Dating • While an organism is living, C– 14/C– 12 is constant because the organism replenishes its supply of carbon ü CO 2 in air ultimate source of all C in organisms • Once the organism dies the C– 14/C– 12 ratio decreases due to radioactive decay • By measuring the C– 14/C– 12 ratio in a once living artifact and comparing it to the C– 14/C– 12 ratio in a living organism, we can tell how long ago the organism died • The limit for this technique is 50, 000 years old ü about 9 half-lives, after which radioactivity from C– 14 will be below the level of background radiation 51

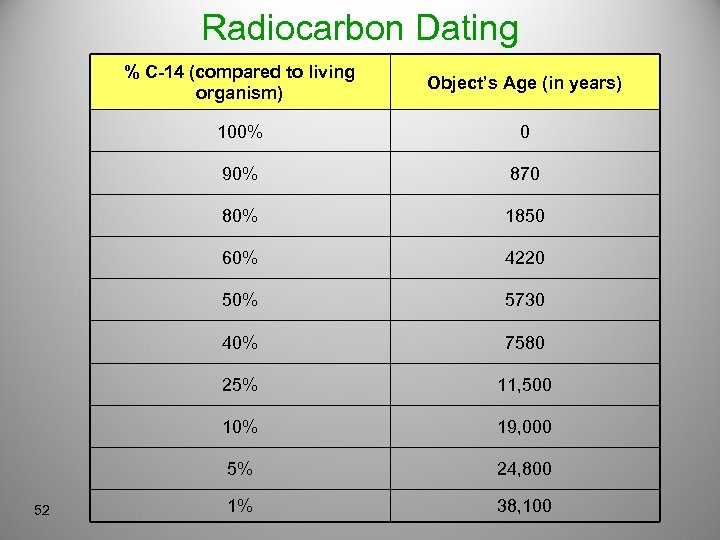

Radiocarbon Dating % C-14 (compared to living organism) 100% 0 90% 870 80% 1850 60% 4220 50% 5730 40% 7580 25% 11, 500 10% 19, 000 5% 52 Object’s Age (in years) 24, 800 1% 38, 100

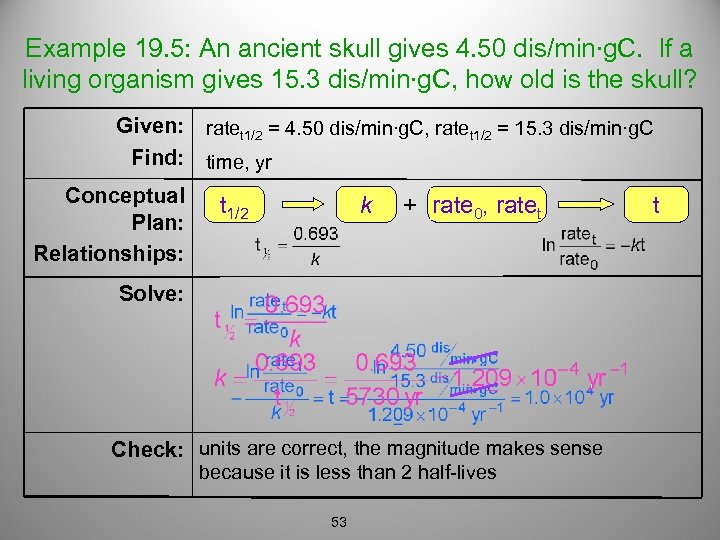

Example 19. 5: An ancient skull gives 4. 50 dis/min∙g. C. If a living organism gives 15. 3 dis/min∙g. C, how old is the skull? Given: ratet 1/2 = 4. 50 dis/min∙g. C, ratet 1/2 = 15. 3 dis/min∙g. C Find: time, yr Conceptual Plan: Relationships: t 1/2 k + rate 0, ratet Solve: Check: units are correct, the magnitude makes sense because it is less than 2 half-lives 53 t

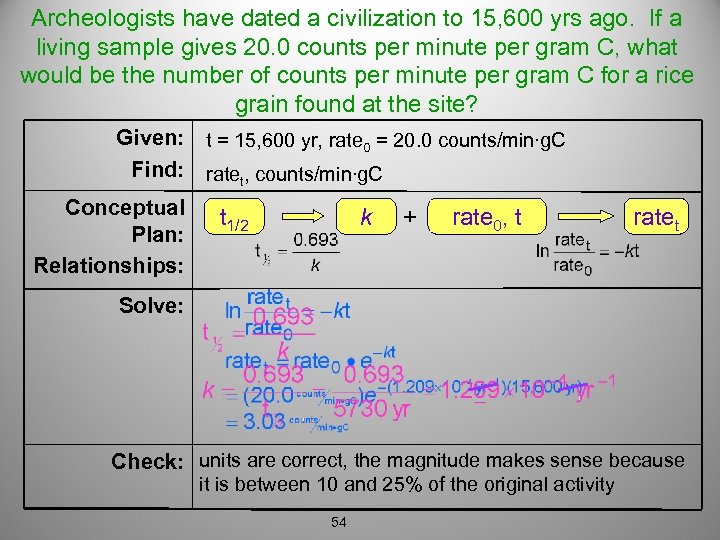

Archeologists have dated a civilization to 15, 600 yrs ago. If a living sample gives 20. 0 counts per minute per gram C, what would be the number of counts per minute per gram C for a rice grain found at the site? Given: t = 15, 600 yr, rate 0 = 20. 0 counts/min∙g. C Find: ratet, counts/min∙g. C Conceptual Plan: Relationships: t 1/2 k + rate 0, t ratet Solve: Check: units are correct, the magnitude makes sense because it is between 10 and 25% of the original activity 54

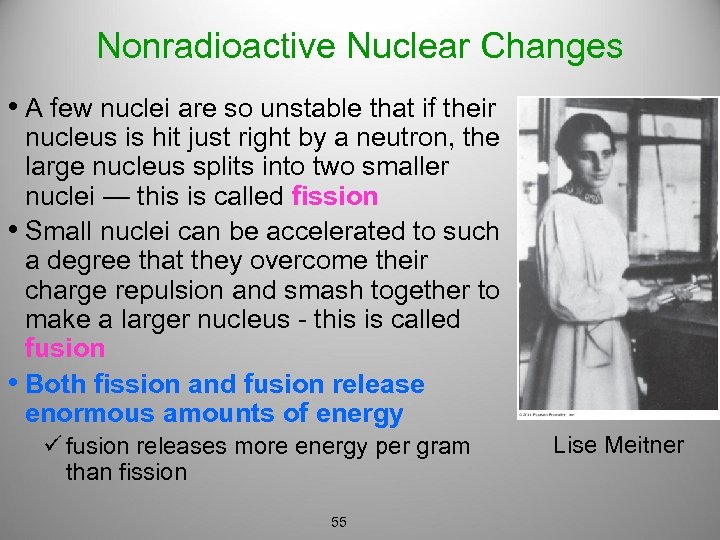

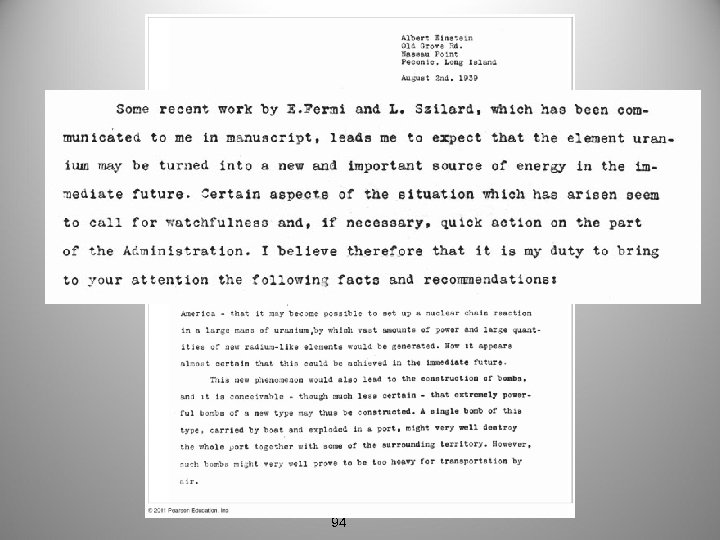

Nonradioactive Nuclear Changes • A few nuclei are so unstable that if their nucleus is hit just right by a neutron, the large nucleus splits into two smaller nuclei — this is called fission • Small nuclei can be accelerated to such a degree that they overcome their charge repulsion and smash together to make a larger nucleus - this is called fusion • Both fission and fusion release enormous amounts of energy ü fusion releases more energy per gram than fission 55 Lise Meitner

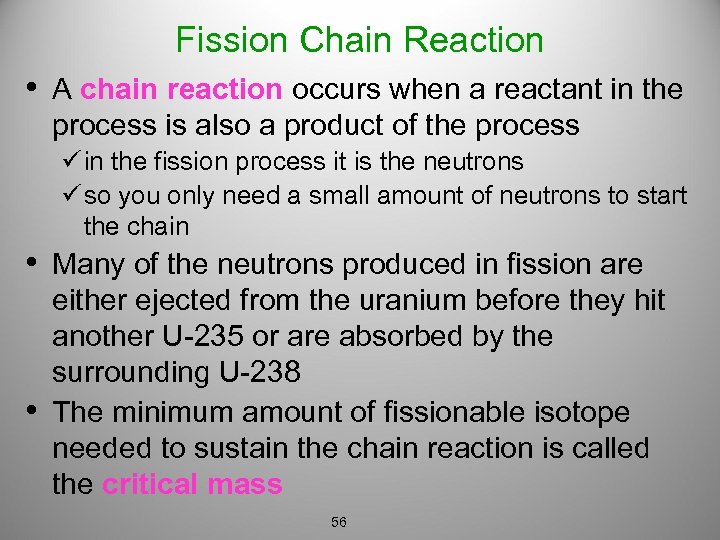

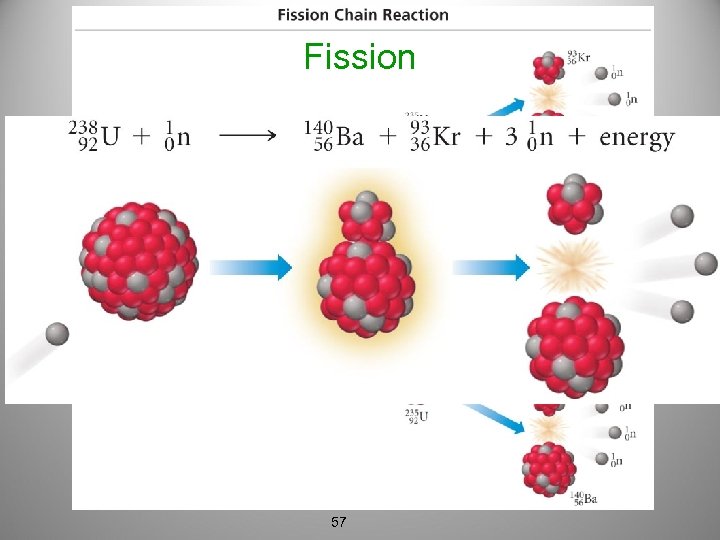

Fission Chain Reaction • A chain reaction occurs when a reactant in the process is also a product of the process ü in the fission process it is the neutrons ü so you only need a small amount of neutrons to start the chain • Many of the neutrons produced in fission are • either ejected from the uranium before they hit another U-235 or are absorbed by the surrounding U-238 The minimum amount of fissionable isotope needed to sustain the chain reaction is called the critical mass 56

Fission 57

Fissionable Material • Fissionable isotopes include ü U– 235, Pu– 239, and Pu– 240 • Natural uranium is mostly U – 238 and less than 1% U– 235 ü Not enough U– 235 to sustain a fission chain reaction • To produce fissionable uranium, the natural uranium must be enriched in U– 235 to ü ~7% for “weapons grade” ü ~3% for reactor grade 58

Nuclear Power Plants vs. Coal-Burning Power Plants • Use about 50 kg of • fuel to generate enough electricity for 1 million people No air pollution • Use about 2 million kg of • • fuel to generate enough electricity for 1 million people Produce NO 2 and SOx that add to acid rain Produce CO 2 that adds to the greenhouse effect • Nuclear reactors use fission to generate about 20% of U. S. electricity, utilizing the heat produced by the fission of U– 235 to boil water, creating steam, and using it to turn a turbine to generate electricity 59

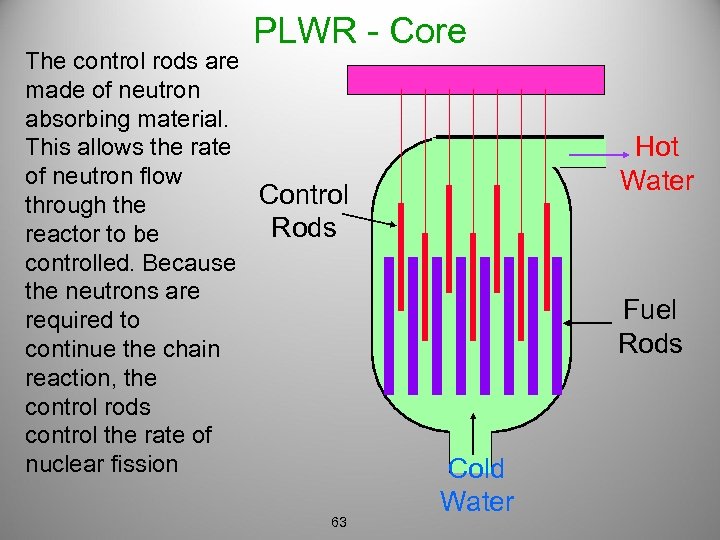

Nuclear Power Plants • The fissionable material is stored in long tubes, called fuel • • rods, arranged in a matrix Between the fuel rods are control rods made of neutronabsorbing materials like boron and/or cadmium ü neutrons are needed to sustain the chain reaction The rods are placed in a material to slow down the ejected neutrons, called a moderator ü allows chain reaction to occur below critical mass 60

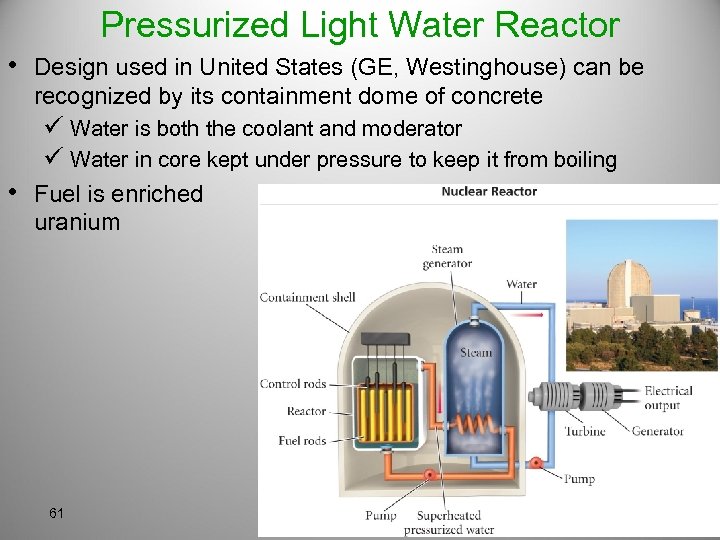

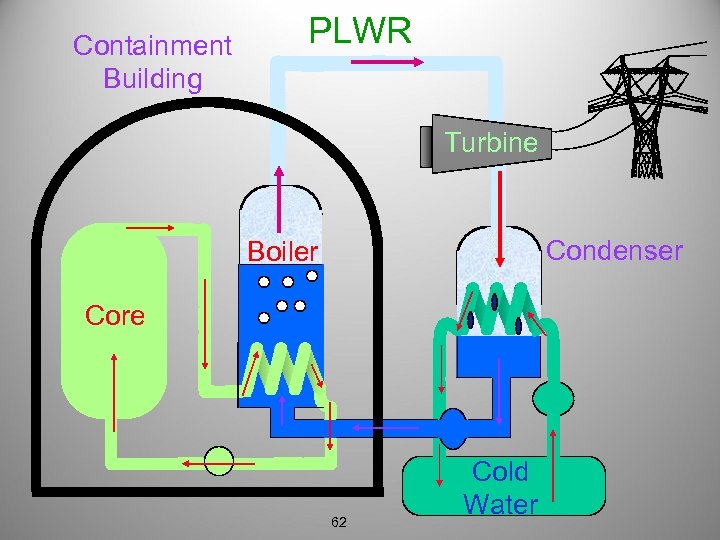

Pressurized Light Water Reactor • Design used in United States (GE, Westinghouse) can be recognized by its containment dome of concrete ü Water is both the coolant and moderator ü Water in core kept under pressure to keep it from boiling • Fuel is enriched uranium 61

Containment Building PLWR Turbine Condenser Boiler Core 62 Cold Water

PLWR - Core The control rods are made of neutron absorbing material. This allows the rate of neutron flow Control through the Rods reactor to be controlled. Because the neutrons are required to continue the chain reaction, the control rods control the rate of nuclear fission 63 Hot Water Fuel Rods Cold Water

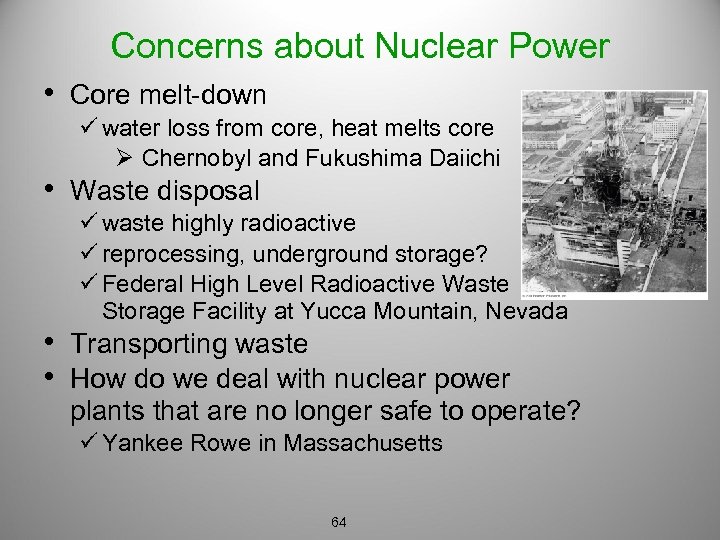

Concerns about Nuclear Power • Core melt-down ü water loss from core, heat melts core Ø Chernobyl and Fukushima Daiichi • Waste disposal ü waste highly radioactive ü reprocessing, underground storage? ü Federal High Level Radioactive Waste Storage Facility at Yucca Mountain, Nevada • Transporting waste • How do we deal with nuclear power plants that are no longer safe to operate? ü Yankee Rowe in Massachusetts 64

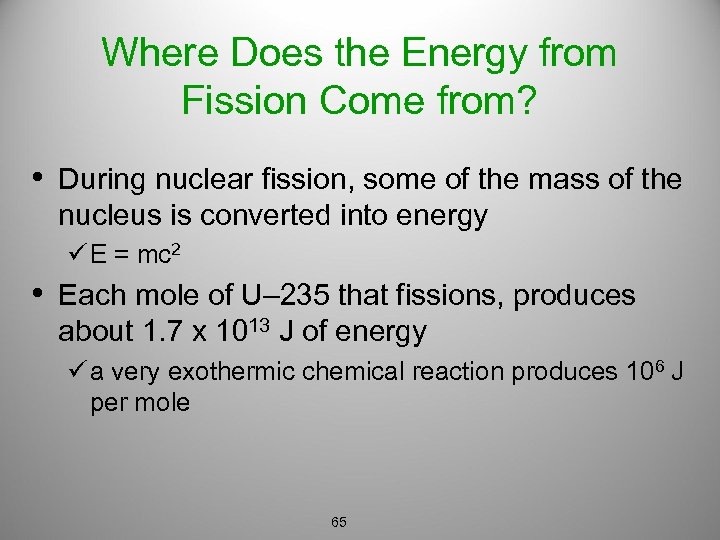

Where Does the Energy from Fission Come from? • During nuclear fission, some of the mass of the nucleus is converted into energy ü E = mc 2 • Each mole of U– 235 that fissions, produces about 1. 7 x 1013 J of energy ü a very exothermic chemical reaction produces 106 J per mole 65

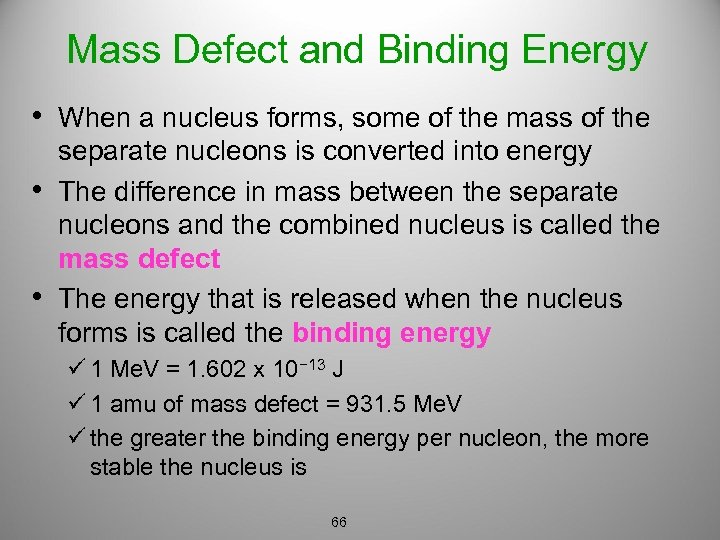

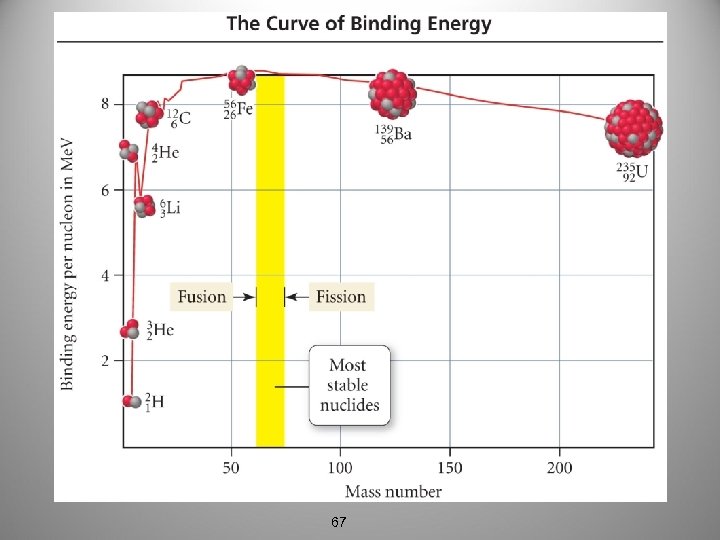

Mass Defect and Binding Energy • When a nucleus forms, some of the mass of the • • separate nucleons is converted into energy The difference in mass between the separate nucleons and the combined nucleus is called the mass defect The energy that is released when the nucleus forms is called the binding energy ü 1 Me. V = 1. 602 x 10− 13 J ü 1 amu of mass defect = 931. 5 Me. V ü the greater the binding energy per nucleon, the more stable the nucleus is 66

67

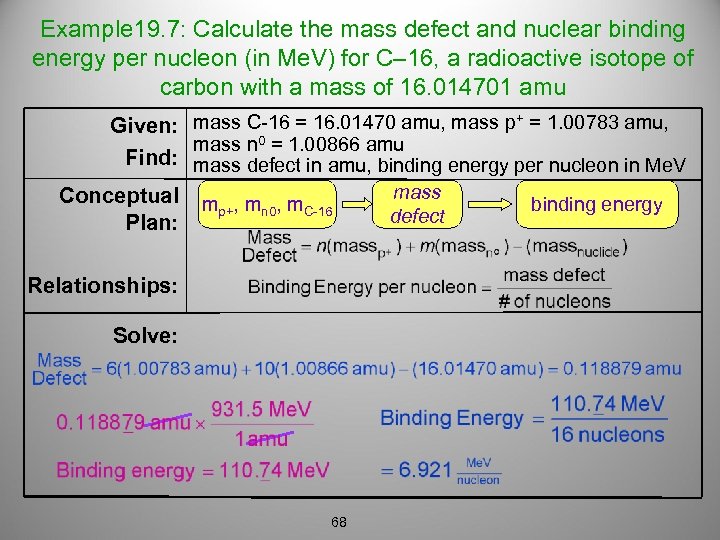

Example 19. 7: Calculate the mass defect and nuclear binding energy per nucleon (in Me. V) for C– 16, a radioactive isotope of carbon with a mass of 16. 014701 amu Given: mass C-16 = 16. 01470 amu, mass p+ = 1. 00783 amu, mass n 0 = 1. 00866 amu Find: mass defect in amu, binding energy per nucleon in Me. V Conceptual Plan: mp+, mn 0, m. C-16 Relationships: Solve: 68 mass defect binding energy

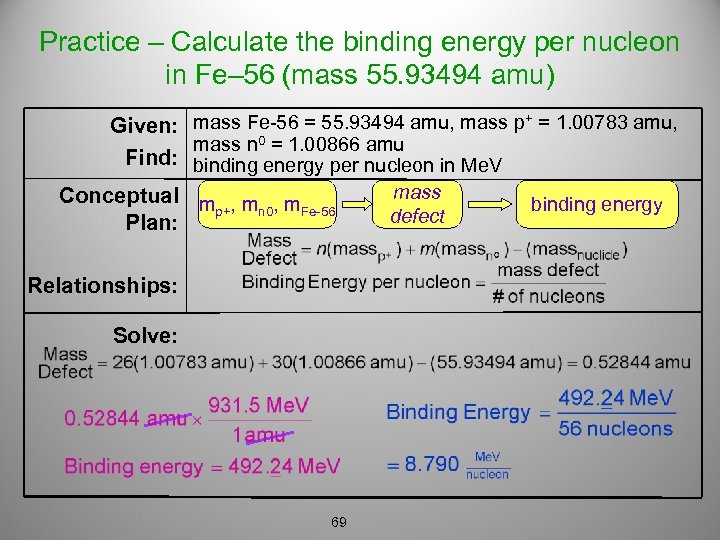

Practice – Calculate the binding energy per nucleon in Fe– 56 (mass 55. 93494 amu) Given: mass Fe-56 = 55. 93494 amu, mass p+ = 1. 00783 amu, mass n 0 = 1. 00866 amu Find: binding energy per nucleon in Me. V Conceptual m , m p+ n 0 Fe-56 Plan: Relationships: Solve: 69 mass defect binding energy

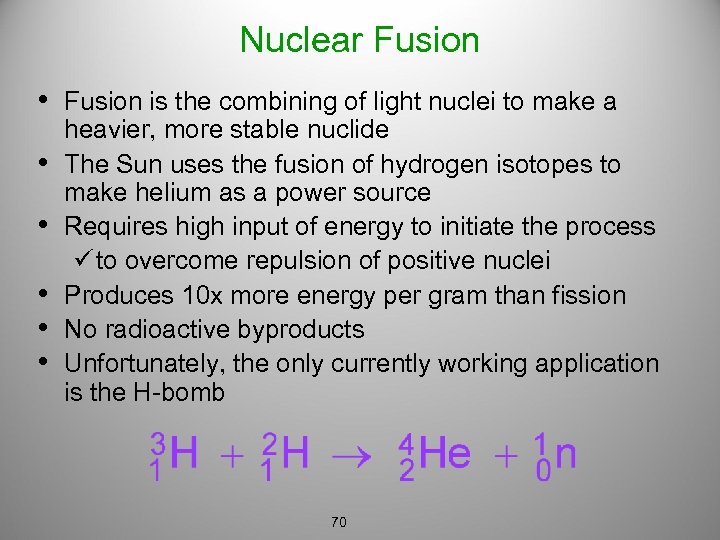

Nuclear Fusion • Fusion is the combining of light nuclei to make a • • • heavier, more stable nuclide The Sun uses the fusion of hydrogen isotopes to make helium as a power source Requires high input of energy to initiate the process ü to overcome repulsion of positive nuclei Produces 10 x more energy per gram than fission No radioactive byproducts Unfortunately, the only currently working application is the H-bomb 70

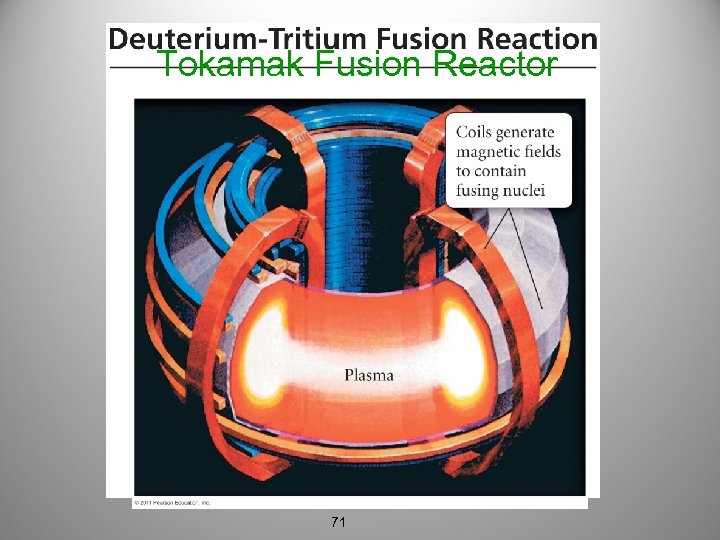

Tokamak Fusion Reactor 71

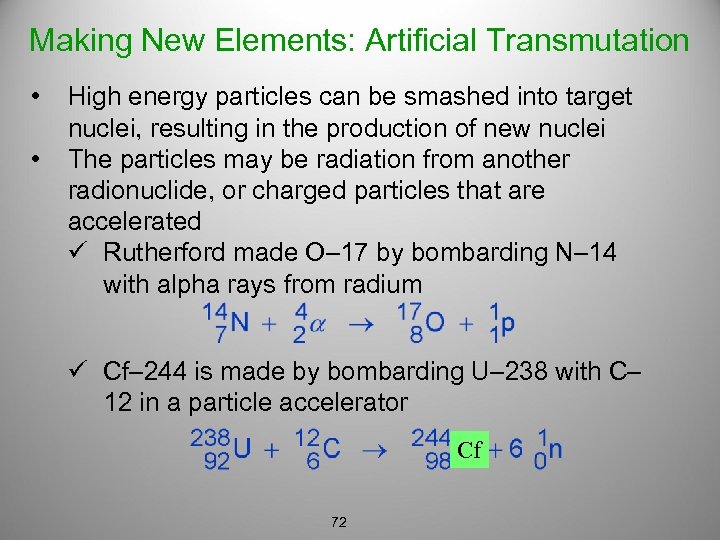

Making New Elements: Artificial Transmutation • • High energy particles can be smashed into target nuclei, resulting in the production of new nuclei The particles may be radiation from another radionuclide, or charged particles that are accelerated ü Rutherford made O– 17 by bombarding N– 14 with alpha rays from radium ü Cf– 244 is made by bombarding U– 238 with C– 12 in a particle accelerator Cf 72

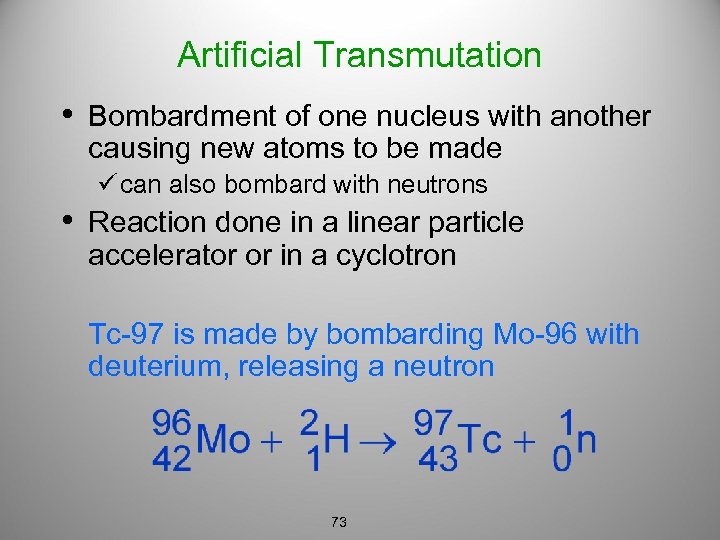

Artificial Transmutation • Bombardment of one nucleus with another causing new atoms to be made ü can also bombard with neutrons • Reaction done in a linear particle accelerator or in a cyclotron Tc-97 is made by bombarding Mo-96 with deuterium, releasing a neutron 73

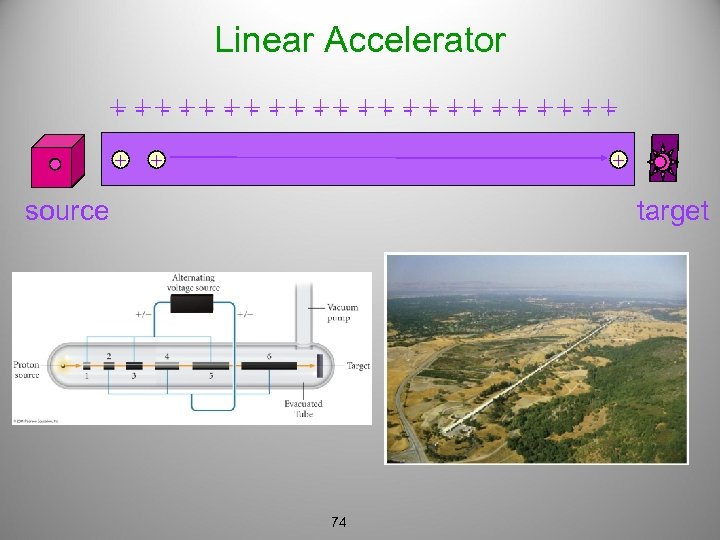

Linear Accelerator + ++ ++ ++ -- -- -- + + + source target 74

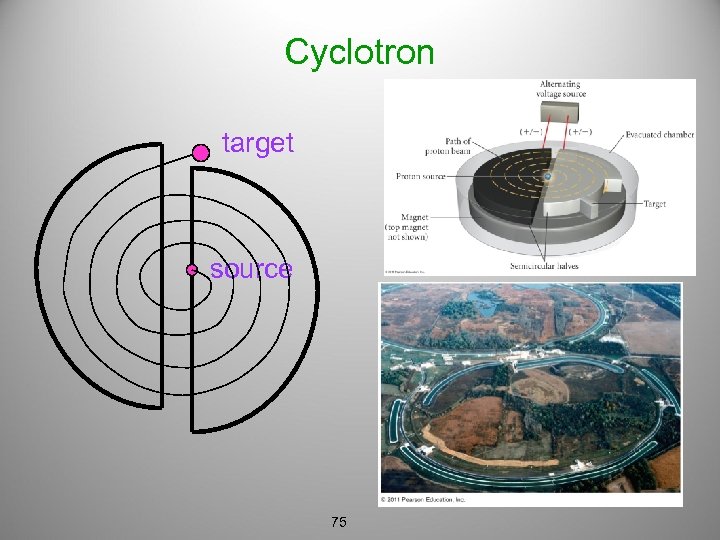

Cyclotron target source 75

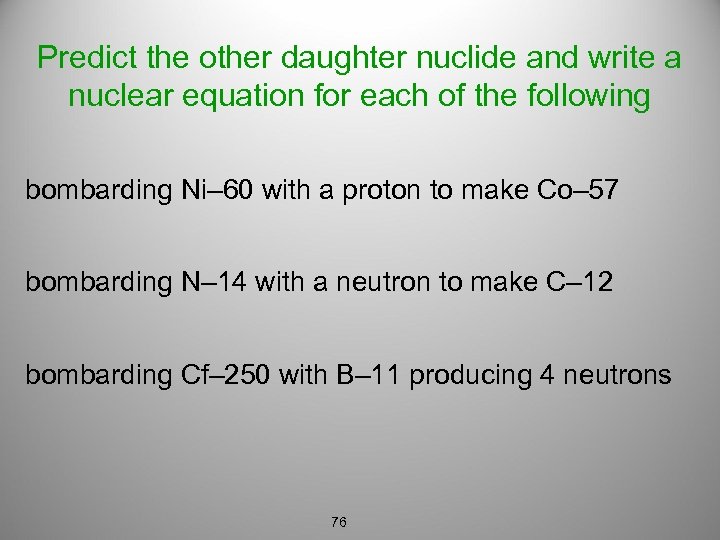

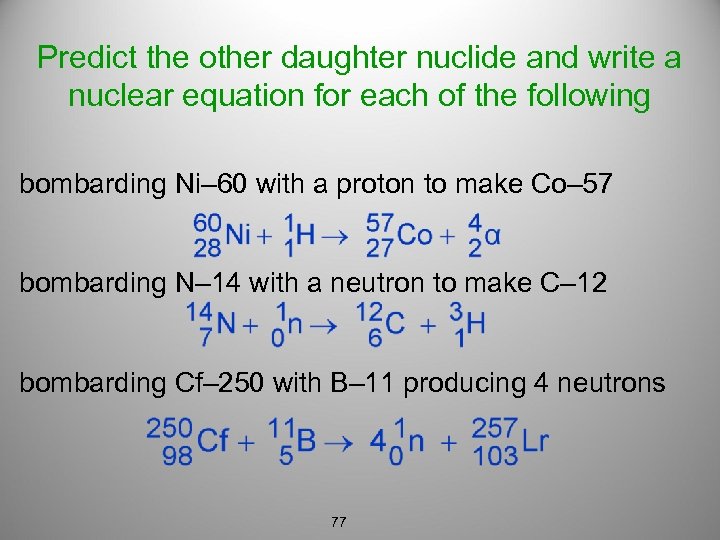

Predict the other daughter nuclide and write a nuclear equation for each of the following bombarding Ni– 60 with a proton to make Co– 57 bombarding N– 14 with a neutron to make C– 12 bombarding Cf– 250 with B– 11 producing 4 neutrons 76

Predict the other daughter nuclide and write a nuclear equation for each of the following bombarding Ni– 60 with a proton to make Co– 57 bombarding N– 14 with a neutron to make C– 12 bombarding Cf– 250 with B– 11 producing 4 neutrons 77

Biological Effects of Radiation • Radiation has high energy, enough to knock electrons from molecules and break bonds ü ionizing radiation • When this energy is transferred to cells, it can • damage biological molecules and cause the malfunction of the cell High levels of radiation over a short period of time kill large numbers of cells ü from a nuclear blast or exposed reactor core • Causes weakened immune system and lower ability to absorb nutrients from food ü may result in death, usually from infection 78

Chronic Effects • Low doses of radiation over a period of time show an increased risk for the development of cancer ü radiation damages DNA that may not get repaired properly • Low doses over time may damage • reproductive organs, which may lead to sterilization Damage to reproductive cells may lead to genetic defects in offspring 79

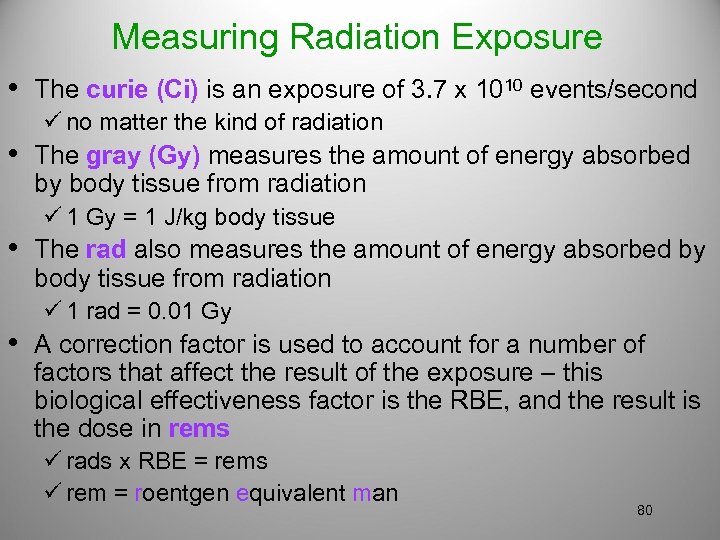

Measuring Radiation Exposure • The curie (Ci) is an exposure of 3. 7 x 1010 events/second ü no matter the kind of radiation • The gray (Gy) measures the amount of energy absorbed by body tissue from radiation ü 1 Gy = 1 J/kg body tissue • The rad also measures the amount of energy absorbed by body tissue from radiation ü 1 rad = 0. 01 Gy • A correction factor is used to account for a number of factors that affect the result of the exposure – this biological effectiveness factor is the RBE, and the result is the dose in rems ü rads x RBE = rems ü rem = roentgen equivalent man 80

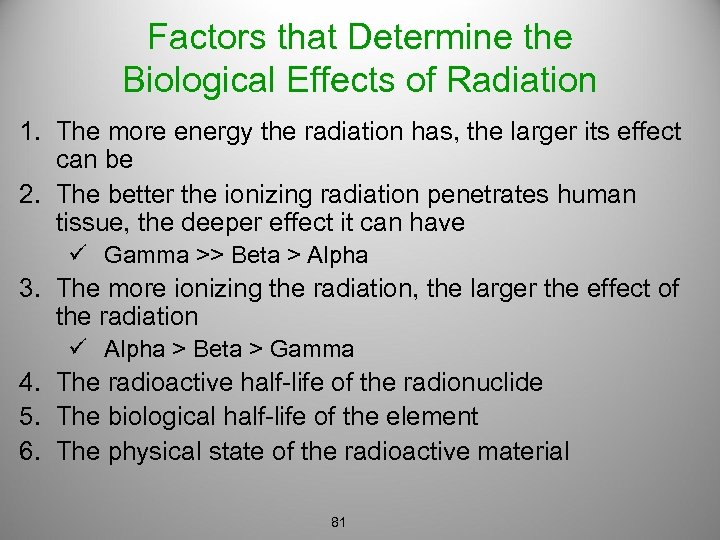

Factors that Determine the Biological Effects of Radiation 1. The more energy the radiation has, the larger its effect can be 2. The better the ionizing radiation penetrates human tissue, the deeper effect it can have ü Gamma >> Beta > Alpha 3. The more ionizing the radiation, the larger the effect of the radiation ü Alpha > Beta > Gamma 4. The radioactive half-life of the radionuclide 5. The biological half-life of the element 6. The physical state of the radioactive material 81

82

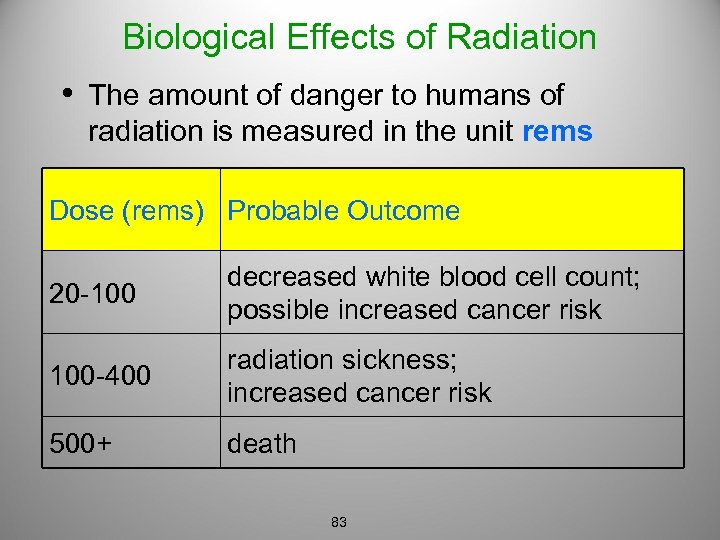

Biological Effects of Radiation • The amount of danger to humans of radiation is measured in the unit rems Dose (rems) Probable Outcome 20 -100 decreased white blood cell count; possible increased cancer risk 100 -400 radiation sickness; increased cancer risk 500+ death 83

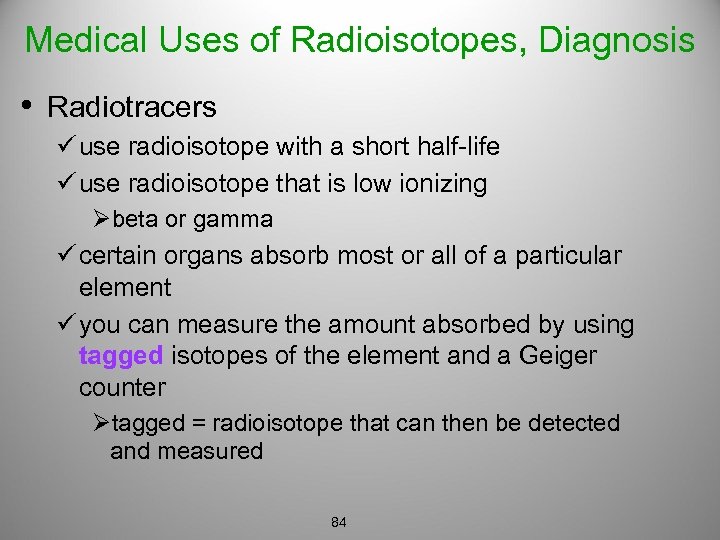

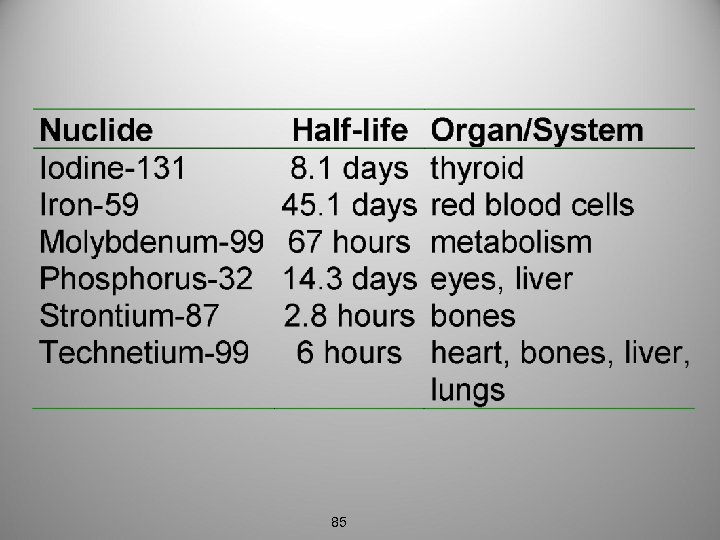

Medical Uses of Radioisotopes, Diagnosis • Radiotracers ü use radioisotope with a short half-life ü use radioisotope that is low ionizing Øbeta or gamma ü certain organs absorb most or all of a particular element ü you can measure the amount absorbed by using tagged isotopes of the element and a Geiger counter Øtagged = radioisotope that can then be detected and measured 84

85

Bone Scans 86

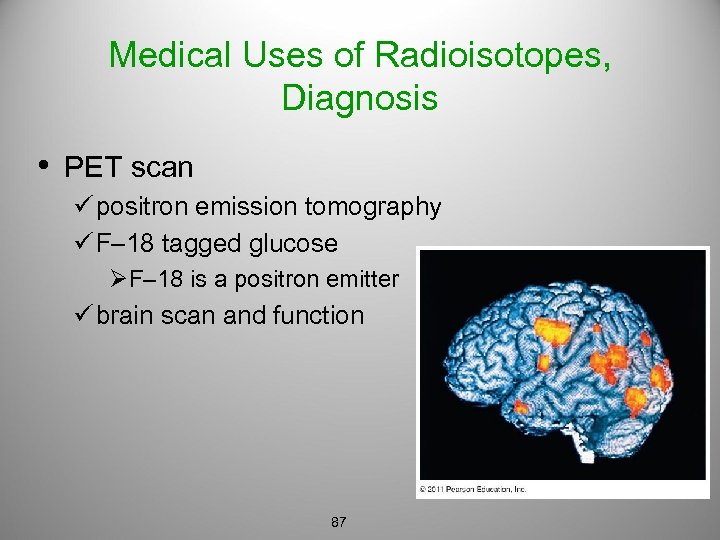

Medical Uses of Radioisotopes, Diagnosis • PET scan ü positron emission tomography ü F– 18 tagged glucose ØF– 18 is a positron emitter ü brain scan and function 87

Medical Uses of Radioisotopes, Treatment – Radiotherapy • Cancer treatment ü cancer cells more sensitive to radiation than healthy cells – use radiation to kill cancer cells without doing significant damage ü brachytherapy Ø place radioisotope directly at site of cancer ü teletherapy Ø use gamma radiation from Co– 60 outside to penetrate inside Ø IMRT ü radiopharmaceutical therapy Ø use radioisotopes that concentrate in one area of the body 88

Gamma Ray Treatment 89

Nonmedical Uses of Radioactive Isotopes • Smoke detectors ü Am– 241 ü smoke blocks ionized air, breaks circuit • Insect control ü sterilize males • Food preservation • Radioactive tracers ü follow progress of a “tagged” atom in a reaction • Chemical analysis ü neutron activation analysis 90

Nonmedical Uses of Radioactive Isotopes • Authenticating art objects ü many older pigments and ceramics were made from minerals with small amounts of radioisotopes • Crime scene investigation • Measure thickness or condition of industrial materials ü corrosion ü track flow through process ü gauges in high temp processes ü weld defects in pipelines ü road thickness 91

Nonmedical Uses of Radioactive Isotopes • Agribusiness ü develop disease-resistant crops ü trace fertilizer use • Treat computer disks to enhance data integrity • Nonstick pan coatings ü initiates polymerization • Photocopiers to help keep paper from jamming • Sterilize cosmetics, hair products and contact lens solutions and other personal hygiene products 92

93

94

Nuclear Medicine • Changes in the structure of the nucleus are • used in many ways in medicine Nuclear radiation can be used to visualize or test structures in your body to see if they are operating properly ü e. g. labeling atoms so their intake and output can be monitored • Nuclear radiation can also be used to treat diseases because the radiation is ionizing, allowing it to attack unhealthy tissue 95

799a0e16a1bb9dc271ee4656c831525f.ppt