570c1dccc9c99e2b6e327416ff71d2af.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 91

Checking Validity of Quantifier-Free Formulas in Combinations of First-Order Theories Clark W. Barrett Ph. D. Dissertation Defense Department of Computer Science Stanford University August 2001

The Problem: First-Order Logic l l l First-Order Logic a mathematical system for making is precise statements. Statements in first-order logic are made up of the following pieces: u Variables x, y u Constants 0, John, u Functions f (x ), x + y u Predicates p (x ), x > y, x = y u Boolean connectives , , , u Quantifiers , Example: “Every rectangle is a square” x. (Rectangle (x ) Square(x))

The Problem: First-Order Theories l A first-order theoryis a set of first-order statements about a related set of constants, functions, and predicates. l A theory of arithmetic might include the following statements about 0 and +: x. ( x + 0 = x ) x, y. (x + y = y + x )

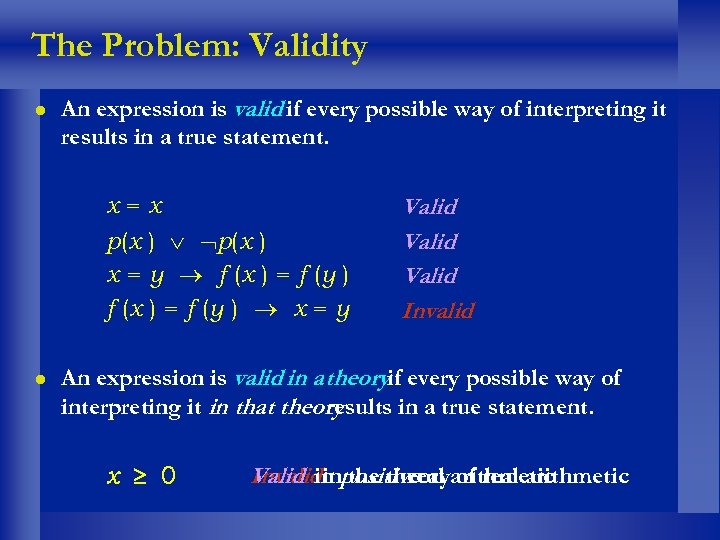

The Problem: Validity l An expression is valid if every possible way of interpreting it results in a true statement. x=x p(x ) x = y f (x ) = f (y ) x = y l Valid Invalid An expression is valid in a theoryif every possible way of interpreting it in that theory results in a true statement. x 0 Valid in theory of real arithmetic Invalidinpositive arithmetic real

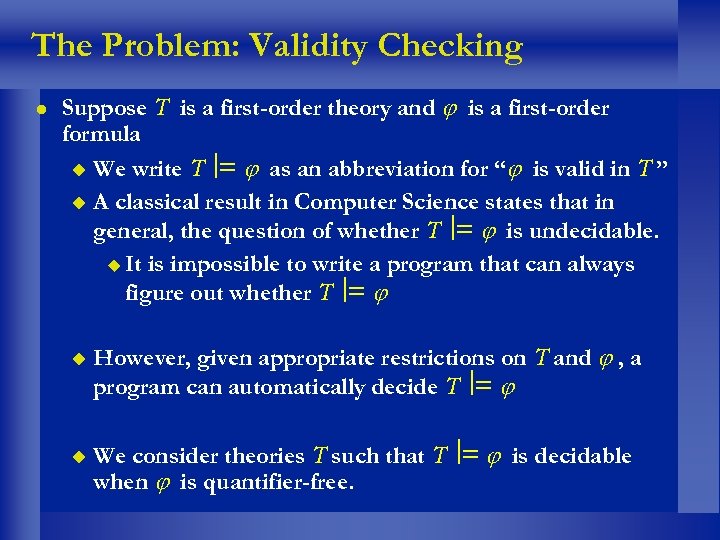

The Problem: Validity Checking l Suppose T is a first-order theory and is a first-order formula u We write T = as an abbreviation for “ is valid in T ” u A classical result in Computer Science states that in general, the question of whether T = is undecidable. u It is impossible to write a program that can always figure out whether T = u u However, given appropriate restrictions on T and , a program can automatically decide T = We consider theories T such that T = is decidable when is quantifier-free.

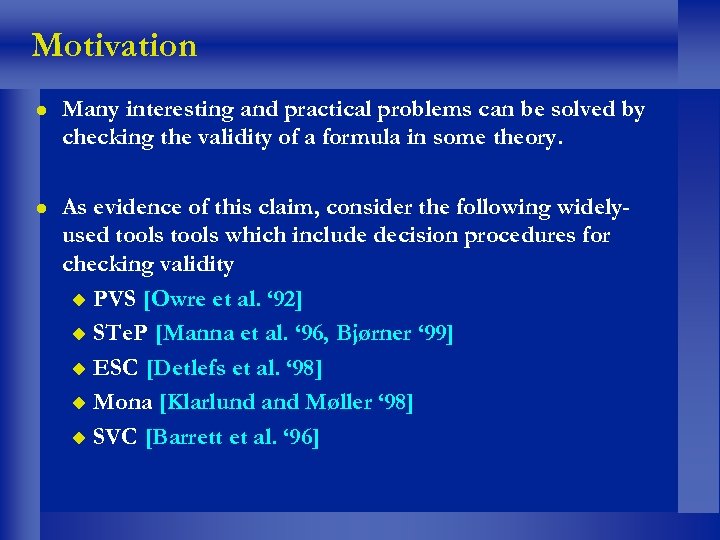

Motivation l Many interesting and practical problems can be solved by checking the validity of a formula in some theory. l As evidence of this claim, consider the following widelyused tools which include decision procedures for checking validity u PVS [Owre et al. ‘ 92] u STe. P [Manna et al. ‘ 96, Bjørner ‘ 99] u ESC [Detlefs et al. ‘ 98] u Mona [Klarlund and Møller ‘ 98] u SVC [Barrett et al. ‘ 96]

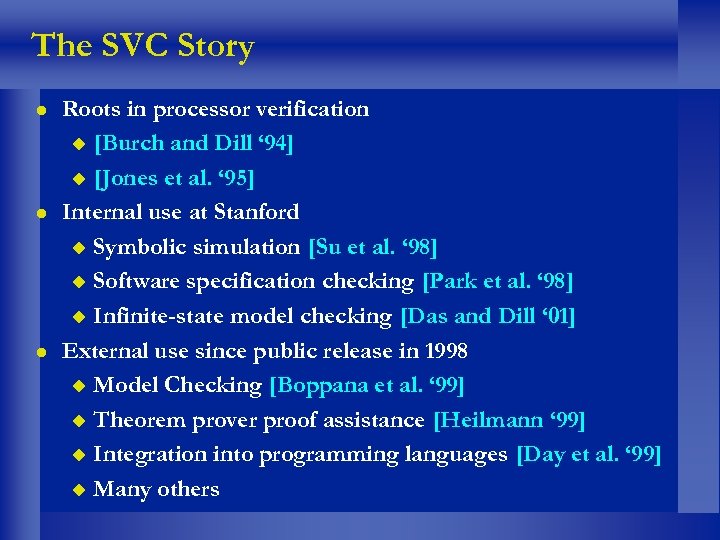

The SVC Story l l l Roots in processor verification u [Burch and Dill ‘ 94] u [Jones et al. ‘ 95] Internal use at Stanford u Symbolic simulation [Su et al. ‘ 98] u Software specification checking [Park et al. ‘ 98] u Infinite-state model checking [Das and Dill ‘ 01] External use since public release in 1998 u Model Checking [Boppana et al. ‘ 99] u Theorem prover proof assistance [Heilmann ‘ 99] u Integration into programming languages [Day et al. ‘ 99] u Many others

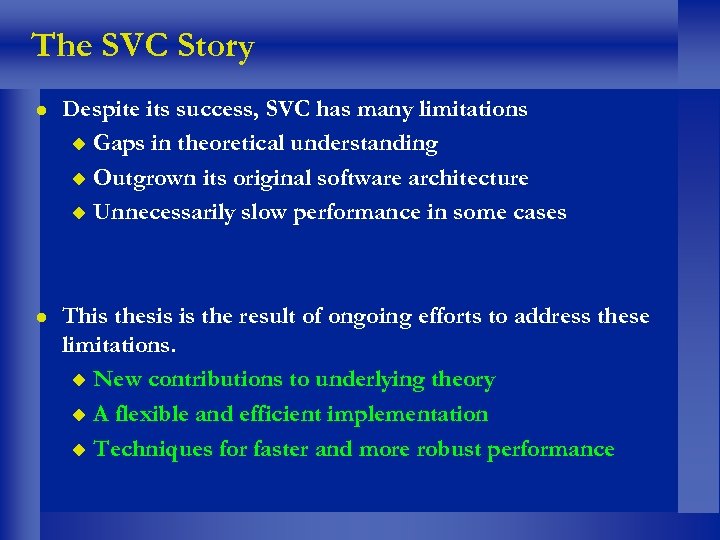

The SVC Story l Despite its success, SVC has many limitations u Gaps in theoretical understanding u Outgrown its original software architecture u Unnecessarily slow performance in some cases l This thesis is the result of ongoing efforts to address these limitations. u New contributions to underlying theory u A flexible and efficient implementation u Techniques for faster and more robust performance

Outline l Validity Checking Overview u The Problem u Motivation u The SVC Story u Top-Level Algorithm l Methods for Combining Theories l Implementation l Adapting Techniques from Propositional Satisfiability l Contributions and Conclusions

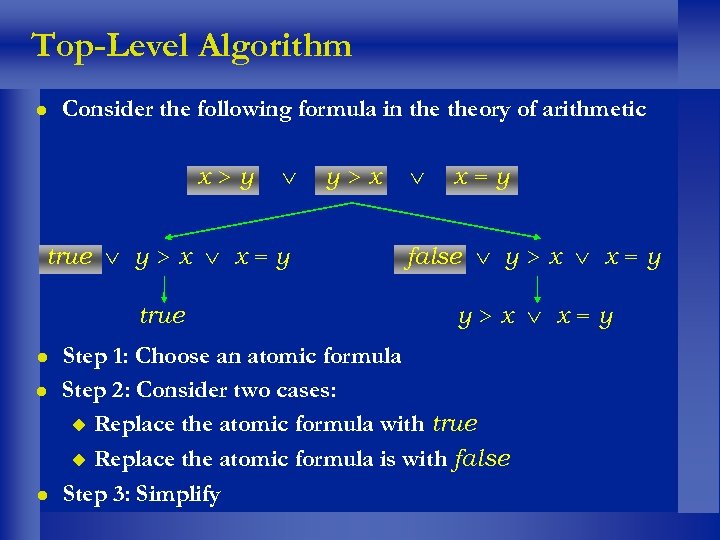

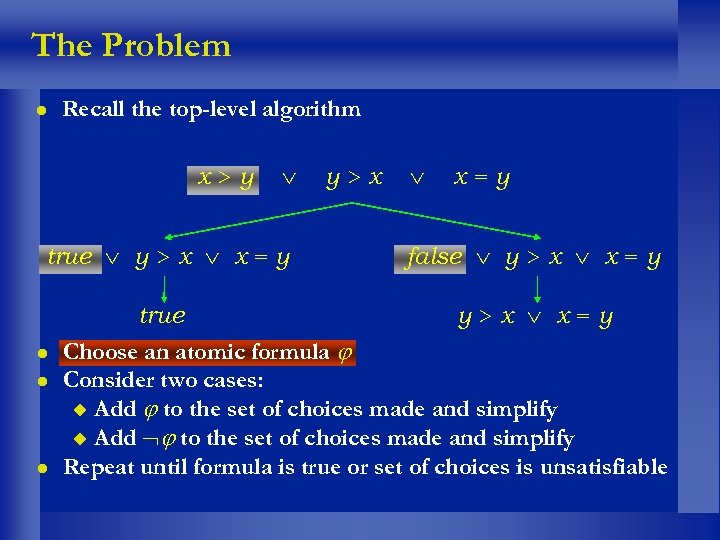

Top-Level Algorithm l Consider the following formula in theory of arithmetic x>y y>x x=y true y > x x = y false y > x x = y true y>x x=y l l l Step 1: Choose an atomic formula Step 2: Consider two cases: u Replace the atomic formula with true u Replace the atomic formula is with false Step 3: Simplify

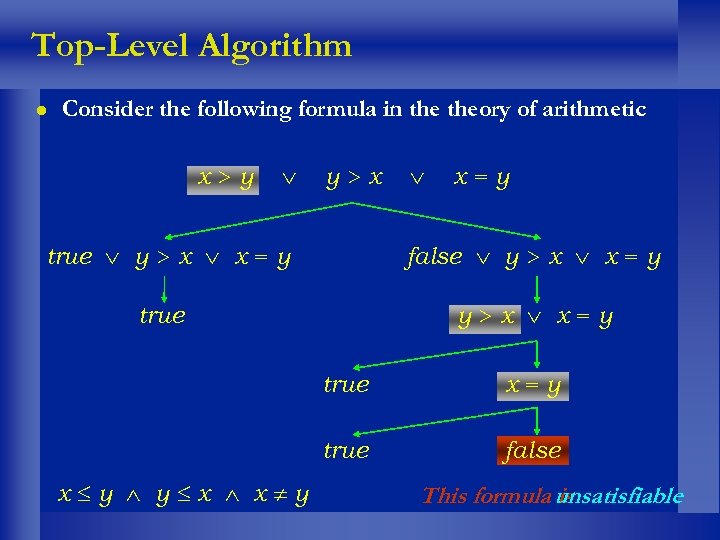

Top-Level Algorithm l Consider the following formula in theory of arithmetic x>y y>x x=y true y > x x = y false y > x x = y true y>x x=y true x y y x x y x=y false This formula unsatisfiable is

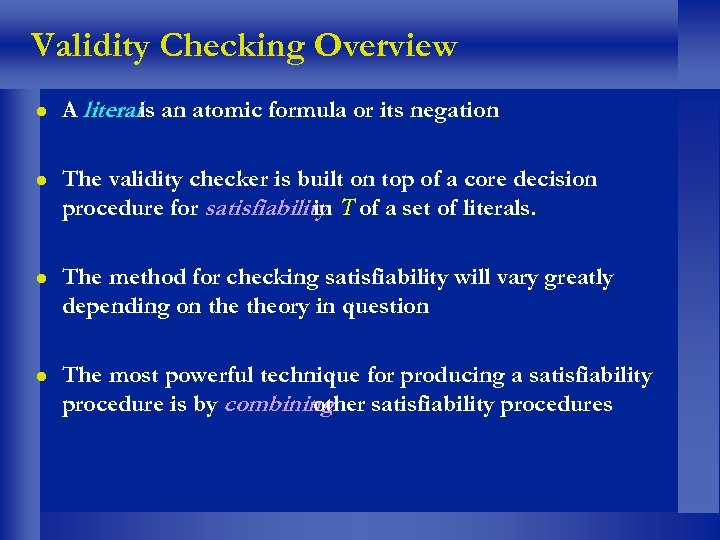

Validity Checking Overview l A literalis an atomic formula or its negation l The validity checker is built on top of a core decision procedure for satisfiability T of a set of literals. in l The method for checking satisfiability will vary greatly depending on theory in question l The most powerful technique for producing a satisfiability procedure is by combining other satisfiability procedures

Outline l Validity Checking Overview l Methods for Combining Theories u The Problem u Shostak’s Method u The Nelson-Oppen Method u A Combined Method l Implementation l Adapting Techniques from Propositional Satisfiability l Contributions and Conclusions

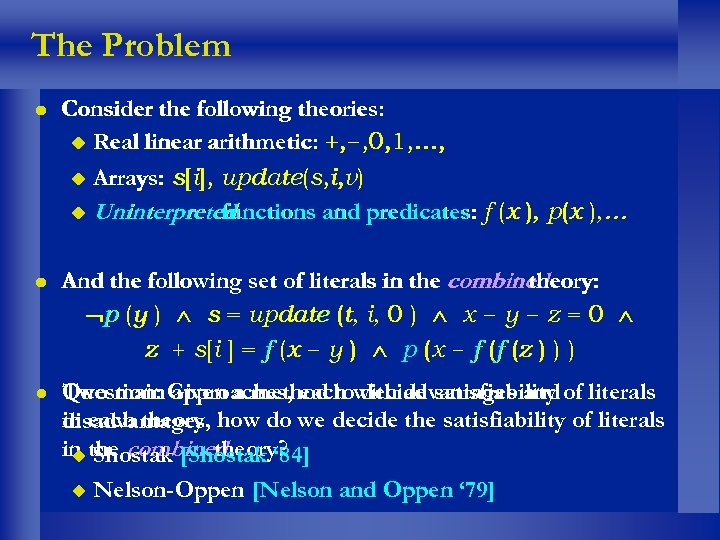

The Problem l Consider the following theories: u Real linear arithmetic: +, -, 0, 1, …, u Arrays: s[i], update(s, i, v) u Uninterpreted functions and predicates: f (x ), p(x ), … l And the following set of literals in the combined theory: p (y ) s = update (t, i, 0 ) x - y - z = 0 z + s[i ] = f (x - y ) p (x - f (f (z ) ) ) l Question: Given a method towith advantages and of literals Two main approaches, each decide satisfiability in each theory, how do we decide the satisfiability of literals disadvantages in the combined theory? u Shostak [Shostak ‘ 84] u Nelson-Oppen [Nelson and Oppen ‘ 79]

Shostak’s Method l l Has formed an ongoing strand of research u Originally published in 1984 [Shostak ‘ 84] u Several clarifying papers since then u [Cyrluk et al. ‘ 96] u [Ruess and Shankar ‘ 01] Used in several automated deduction systems u PVS, STe. P, SVC Unfortunately, remains difficult to understand u Details are nonintuitive u Simple proof of correctness has been especially elusive Contribution. A new presentation of a key subset of Shostak’s : original algorithm.

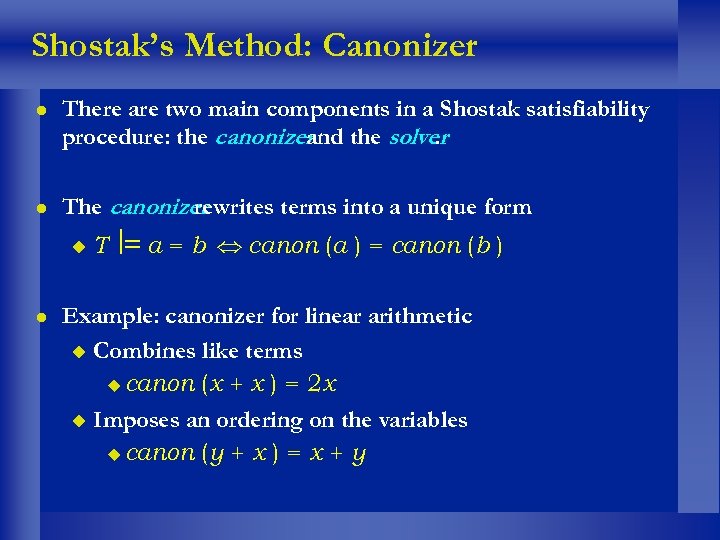

Shostak’s Method: Canonizer l There are two main components in a Shostak satisfiability procedure: the canonizer and the solver. l The canonizer rewrites terms into a unique form u l T = a = b canon (a ) = canon (b ) Example: canonizer for linear arithmetic u Combines like terms u canon (x + x ) = 2 x u Imposes an ordering on the variables u canon (y + x ) = x + y

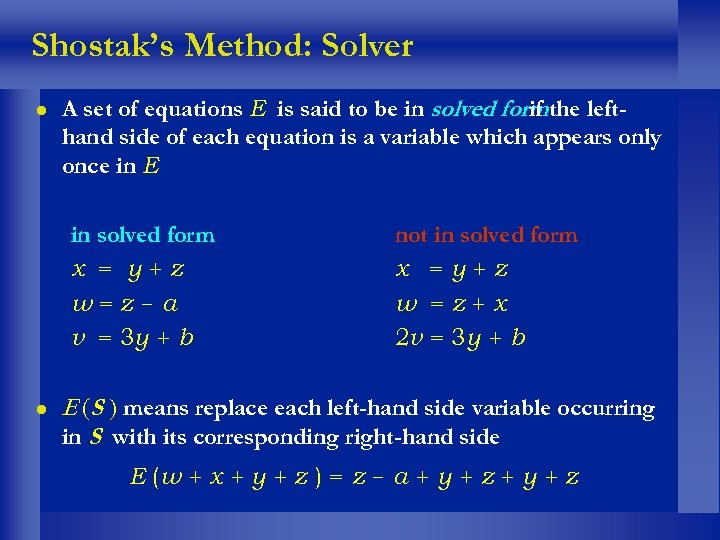

Shostak’s Method: Solver l A set of equations E is said to be in solved formthe leftif hand side of each equation is a variable which appears only once in E in solved form x = y+z w=z-a v = 3 y + b l not in solved form x =y+z w =z+x 2 v = 3 y + b S means replace each left-hand side variable occurring in S with its corresponding right-hand side E (w + x + y + z ) = z - a + y + z

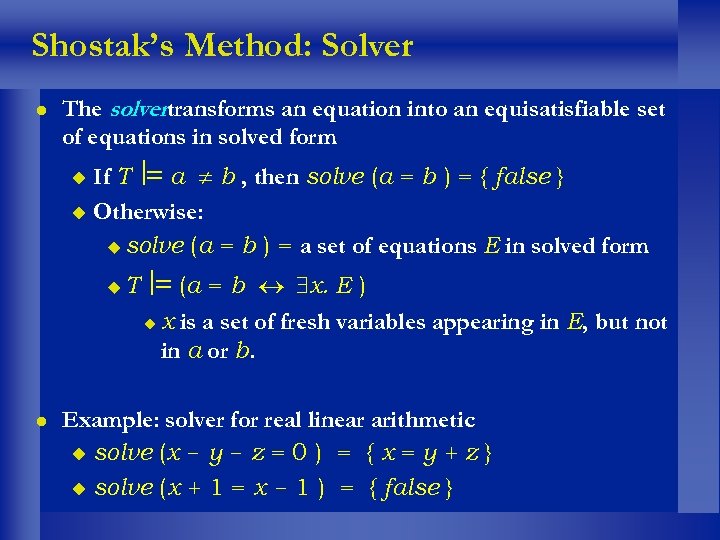

Shostak’s Method: Solver l The solvertransforms an equation into an equisatisfiable set of equations in solved form If T = a b , then solve (a = b ) = { false } u Otherwise: u solve (a = b ) = a set of equations E in solved form u u l T = (a = b x. E ) u x is a set of fresh variables appearing in E, but not in a or b. Example: solver for real linear arithmetic u solve (x - y - z = 0 ) = { x = y + z } u solve (x + 1 = x - 1 ) = { false }

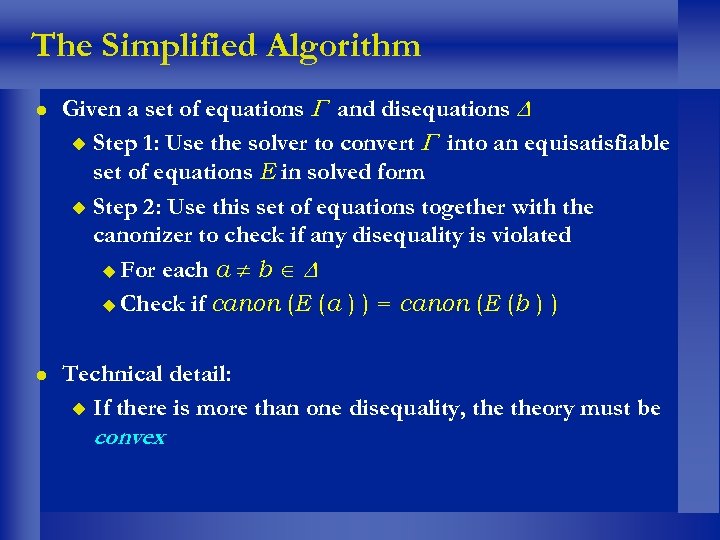

The Simplified Algorithm l Given a set of equations and disequations u Step 1: Use the solver to convert into an equisatisfiable set of equations E in solved form u Use a generalization of Gaussian elimination with back substitution

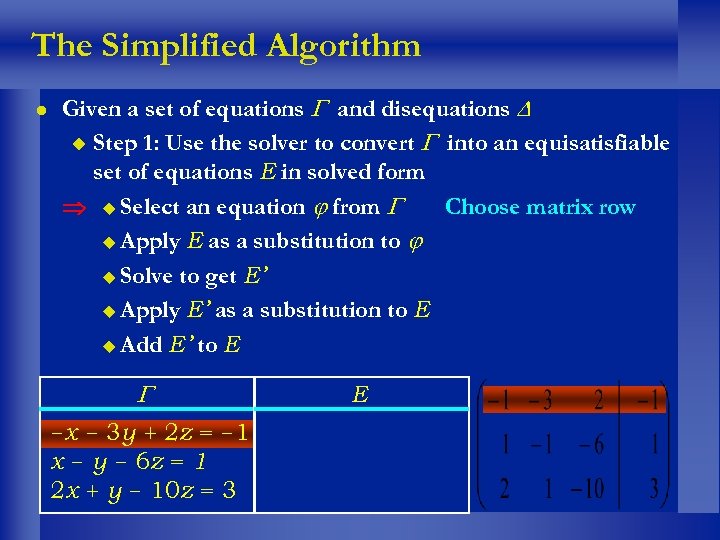

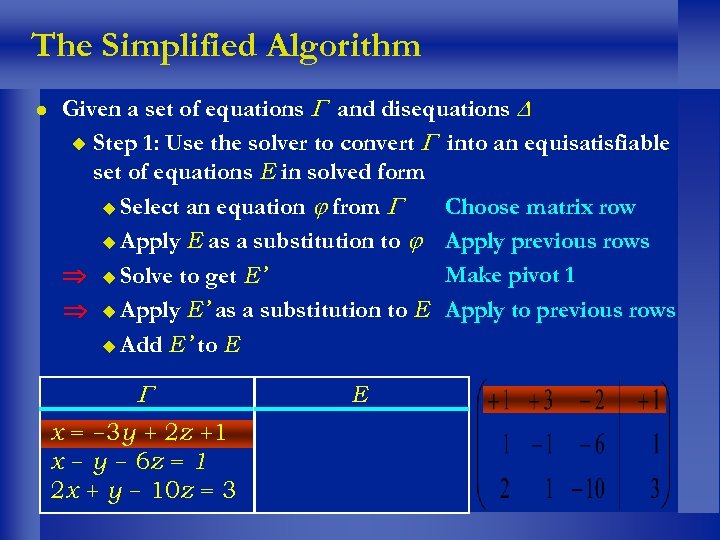

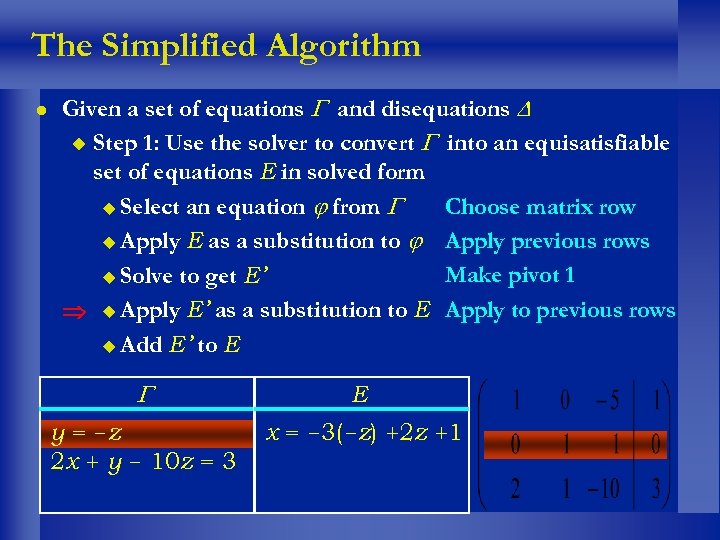

The Simplified Algorithm l Given a set of equations and disequations u Step 1: Use the solver to convert into an equisatisfiable set of equations E in solved form Choose matrix row u Select an equation from u Apply E as a substitution to u Solve to get E’ u Apply E’ as a substitution to E u Add E’ to E -x - 3 y + 2 z = -1 x - y - 6 z = 1 2 x + y - 10 z = 3 E

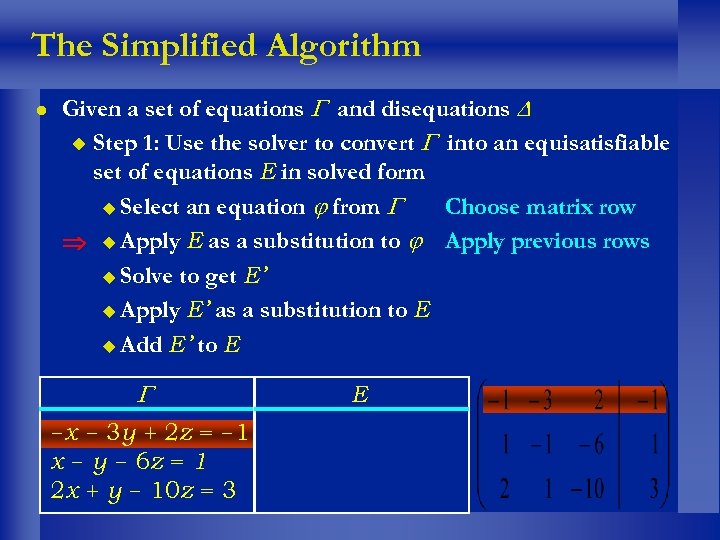

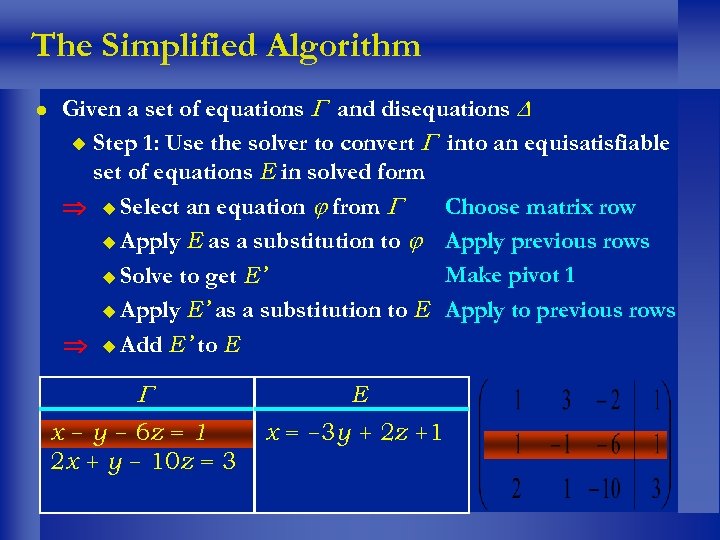

The Simplified Algorithm l Given a set of equations and disequations u Step 1: Use the solver to convert into an equisatisfiable set of equations E in solved form u Select an equation from Choose matrix row u Apply E as a substitution to Apply previous rows u Solve to get E’ u Apply E’ as a substitution to E u Add E’ to E -x - 3 y + 2 z = -1 x - y - 6 z = 1 2 x + y - 10 z = 3 E

The Simplified Algorithm l Given a set of equations and disequations u Step 1: Use the solver to convert into an equisatisfiable set of equations E in solved form u Select an equation from Choose matrix row Apply previous rows u Apply E as a substitution to Make pivot 1 u Solve to get E’ u Apply E’ as a substitution to E Apply to previous rows u Add E’ to E x = -3 y + 2 z +1 x - y - 6 z = 1 2 x + y - 10 z = 3 E

The Simplified Algorithm l Given a set of equations and disequations u Step 1: Use the solver to convert into an equisatisfiable set of equations E in solved form Choose matrix row u Select an equation from Apply previous rows u Apply E as a substitution to Make pivot 1 u Solve to get E’ u Apply E’ as a substitution to E Apply to previous rows u Add E’ to E E x - y - 6 z = 1 2 x + y - 10 z = 3 x = -3 y + 2 z +1

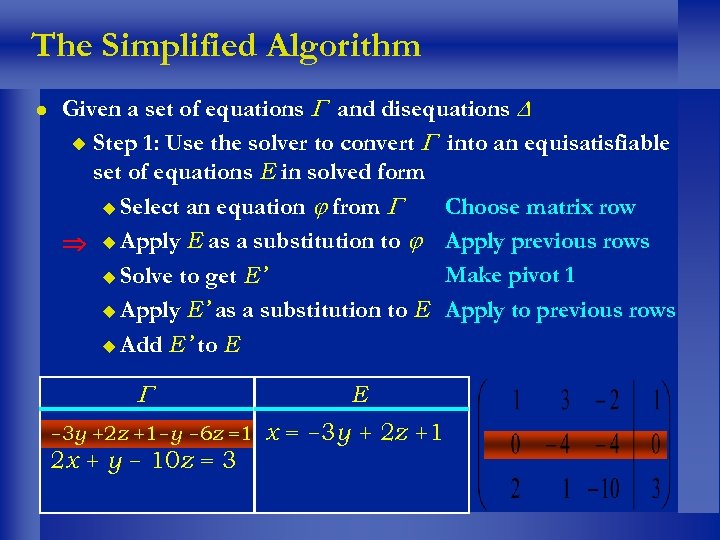

The Simplified Algorithm l Given a set of equations and disequations u Step 1: Use the solver to convert into an equisatisfiable set of equations E in solved form u Select an equation from Choose matrix row u Apply E as a substitution to Apply previous rows Make pivot 1 u Solve to get E’ u Apply E’ as a substitution to E Apply to previous rows u Add E’ to E -3 y +2 z +1 -y -6 z =1 2 x + y - 10 z = 3 E x = -3 y + 2 z +1

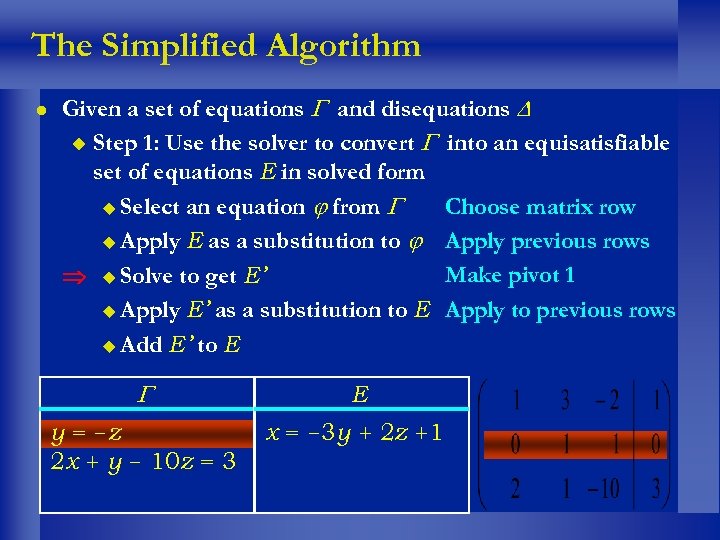

The Simplified Algorithm l Given a set of equations and disequations u Step 1: Use the solver to convert into an equisatisfiable set of equations E in solved form u Select an equation from Choose matrix row Apply previous rows u Apply E as a substitution to Make pivot 1 u Solve to get E’ u Apply E’ as a substitution to E Apply to previous rows u Add E’ to E E y = -z 2 x + y - 10 z = 3 x = -3 y + 2 z +1

The Simplified Algorithm l Given a set of equations and disequations u Step 1: Use the solver to convert into an equisatisfiable set of equations E in solved form u Select an equation from Choose matrix row Apply previous rows u Apply E as a substitution to Make pivot 1 u Solve to get E’ u Apply E’ as a substitution to E Apply to previous rows u Add E’ to E E y = -z 2 x + y - 10 z = 3 x = -3(-z) +2 z +1

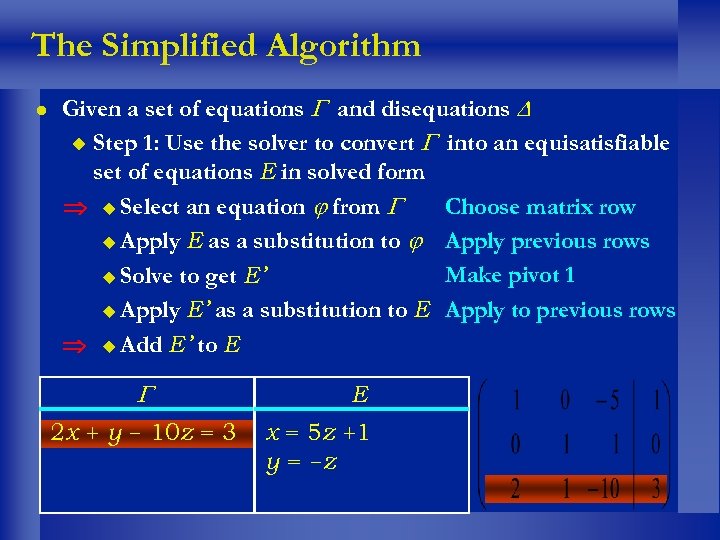

The Simplified Algorithm l Given a set of equations and disequations u Step 1: Use the solver to convert into an equisatisfiable set of equations E in solved form Choose matrix row u Select an equation from Apply previous rows u Apply E as a substitution to Make pivot 1 u Solve to get E’ u Apply E’ as a substitution to E Apply to previous rows u Add E’ to E 2 x + y - 10 z = 3 E x = 5 z +1 y = -z

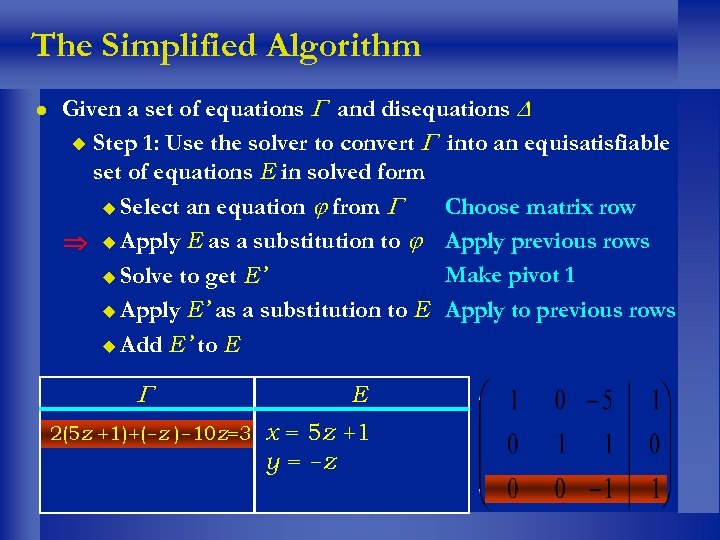

The Simplified Algorithm l Given a set of equations and disequations u Step 1: Use the solver to convert into an equisatisfiable set of equations E in solved form u Select an equation from Choose matrix row u Apply E as a substitution to Apply previous rows Make pivot 1 u Solve to get E’ u Apply E’ as a substitution to E Apply to previous rows u Add E’ to E 2(5 z +1)+(-z )-10 z=3 E x = 5 z +1 y = -z

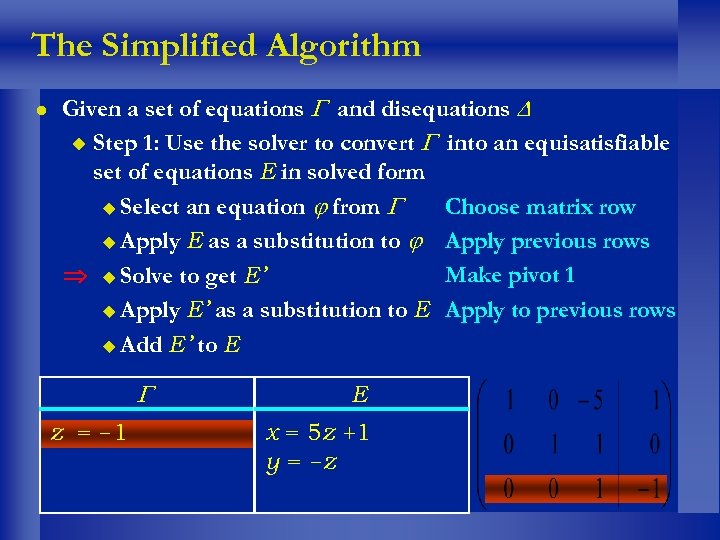

The Simplified Algorithm l Given a set of equations and disequations u Step 1: Use the solver to convert into an equisatisfiable set of equations E in solved form u Select an equation from Choose matrix row Apply previous rows u Apply E as a substitution to Make pivot 1 u Solve to get E’ u Apply E’ as a substitution to E Apply to previous rows u Add E’ to E z = -1 E x = 5 z +1 y = -z

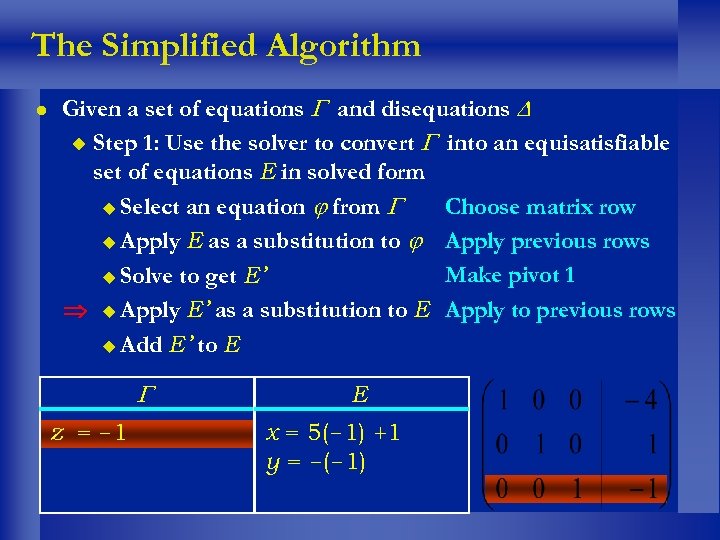

The Simplified Algorithm l Given a set of equations and disequations u Step 1: Use the solver to convert into an equisatisfiable set of equations E in solved form u Select an equation from Choose matrix row Apply previous rows u Apply E as a substitution to Make pivot 1 u Solve to get E’ u Apply E’ as a substitution to E Apply to previous rows u Add E’ to E z = -1 E x = 5(-1) +1 y = -(-1)

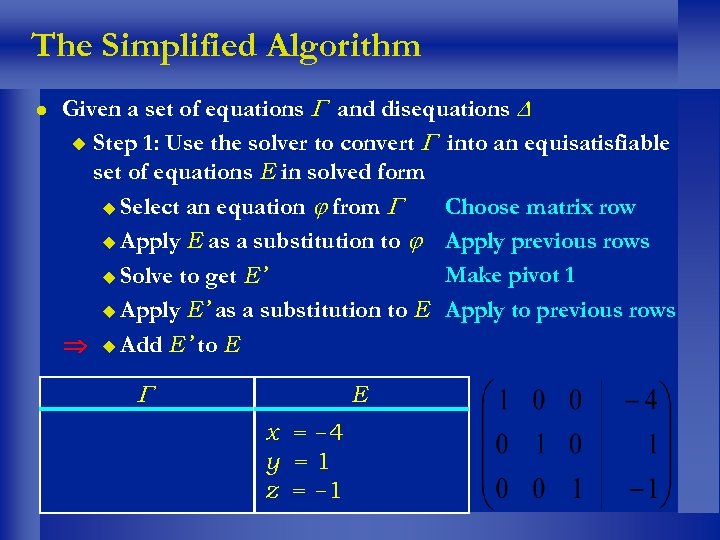

The Simplified Algorithm l Given a set of equations and disequations u Step 1: Use the solver to convert into an equisatisfiable set of equations E in solved form u Select an equation from Choose matrix row Apply previous rows u Apply E as a substitution to Make pivot 1 u Solve to get E’ u Apply E’ as a substitution to E Apply to previous rows u Add E’ to E E x = -4 y =1 z = -1

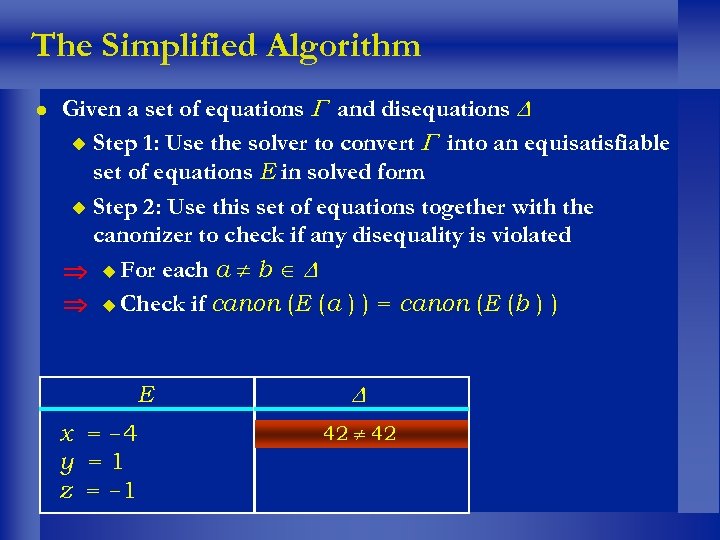

The Simplified Algorithm l Given a set of equations and disequations u Step 1: Use the solver to convert into an equisatisfiable set of equations E in solved form u Step 2: Use this set of equations together with the canonizer to check if any disequality is violated u For each a b u Check if canon (E (a ) ) = canon (E (b ) ) E x = -4 y =1 z = -1 2 y - 10 x 42 - 2 x) 42 6(z 2(1)-10(-4) 6(-1 -2(-4))

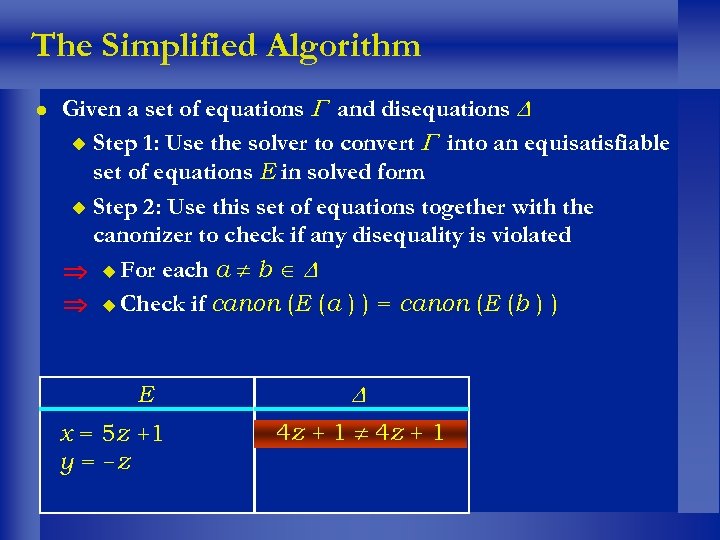

The Simplified Algorithm l Given a set of equations and disequations u Step 1: Use the solver to convert into an equisatisfiable set of equations E in solved form u Step 2: Use this set of equations together with the canonizer to check if any disequality is violated u For each a b u Check if canon (E (a ) ) = canon (E (b ) ) E x = 5 z +1 y = -z 4 z +4 y 4 z - z -z 1 - 1 x +1 1 -4(-z) (5 z +1)

The Simplified Algorithm l l Given a set of equations and disequations u Step 1: Use the solver to convert into an equisatisfiable set of equations E in solved form u Step 2: Use this set of equations together with the canonizer to check if any disequality is violated u For each a b u Check if canon (E (a ) ) = canon (E (b ) ) Technical detail: u If there is more than one disequality, theory must be convex

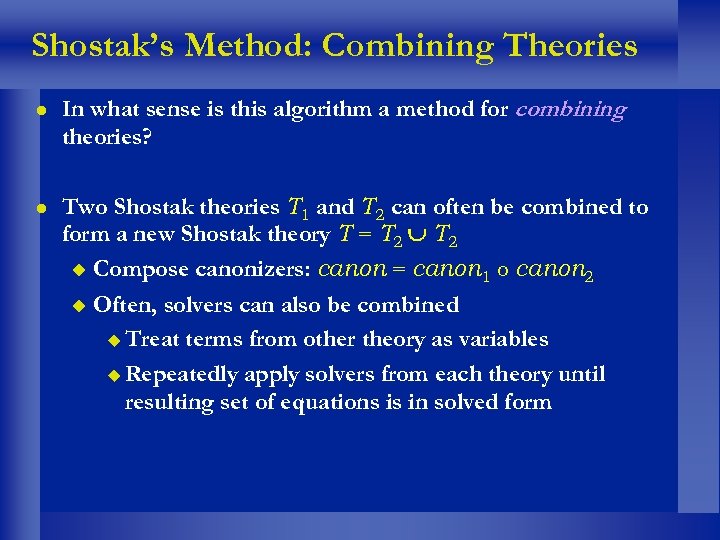

Shostak’s Method: Combining Theories l In what sense is this algorithm a method for combining theories? l Two Shostak theories T 1 and T 2 can often be combined to form a new Shostak theory T = T 2 u Compose canonizers: canon = canon 1 o canon 2 u Often, solvers can also be combined u Treat terms from other theory as variables u Repeatedly apply solvers from each theory until resulting set of equations is in solved form

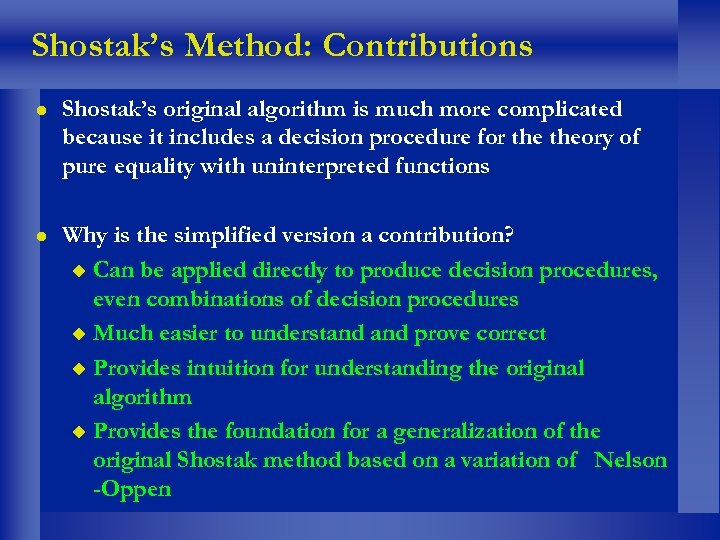

Shostak’s Method: Contributions l Shostak’s original algorithm is much more complicated because it includes a decision procedure for theory of pure equality with uninterpreted functions l Why is the simplified version a contribution? u Can be applied directly to produce decision procedures, even combinations of decision procedures u Much easier to understand prove correct u Provides intuition for understanding the original algorithm u Provides the foundation for a generalization of the original Shostak method based on a variation of Nelson -Oppen

![Nelson-Oppen l Developed for the Stanford Pascal Verifier u [Nelson and Oppen ‘ 79] Nelson-Oppen l Developed for the Stanford Pascal Verifier u [Nelson and Oppen ‘ 79]](https://present5.com/presentation/570c1dccc9c99e2b6e327416ff71d2af/image-37.jpg)

Nelson-Oppen l Developed for the Stanford Pascal Verifier u [Nelson and Oppen ‘ 79] u [Nelson ‘ 80, Oppen ‘ 80] l Tinelli and Harandi discovered a new (simpler) proof and an important optimization u [Tinelli and Harandi ‘ 96] l Used in real systems u ESC u EHDM [von Henke et al. ‘ 88] u Vampyre [http: //www-cad. eecs. berkeley. edu/~rupak/Vampyre]

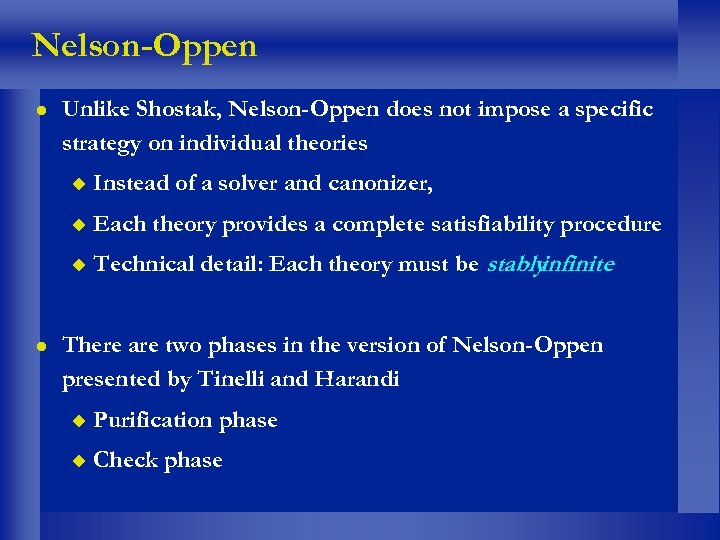

Nelson-Oppen l Unlike Shostak, Nelson-Oppen does not impose a specific strategy on individual theories u u Each theory provides a complete satisfiability procedure u l Instead of a solver and canonizer, Technical detail: Each theory must be stably infinite There are two phases in the version of Nelson-Oppen presented by Tinelli and Harandi u Purification phase u Check phase

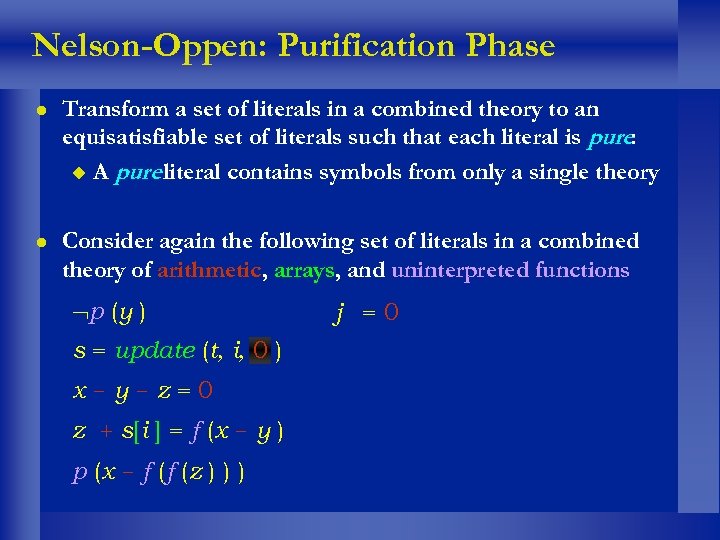

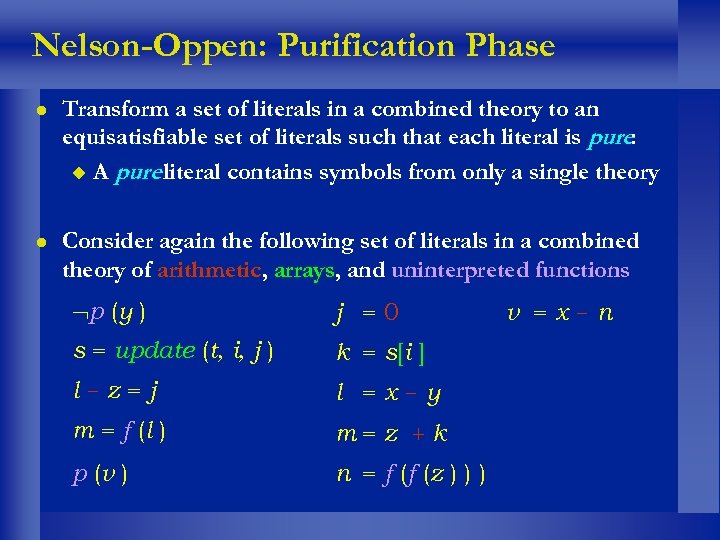

Nelson-Oppen: Purification Phase l Transform a set of literals in a combined theory to an equisatisfiable set of literals such that each literal is pure: u A pure literal contains symbols from only a single theory l Consider again the following set of literals in a combined theory of arithmetic, arrays, and uninterpreted functions p (y ) s = update (t, i, 0 ) x-y-z=0 z + s[i ] = f (x - y ) p (x - f (f (z ) ) ) j =0

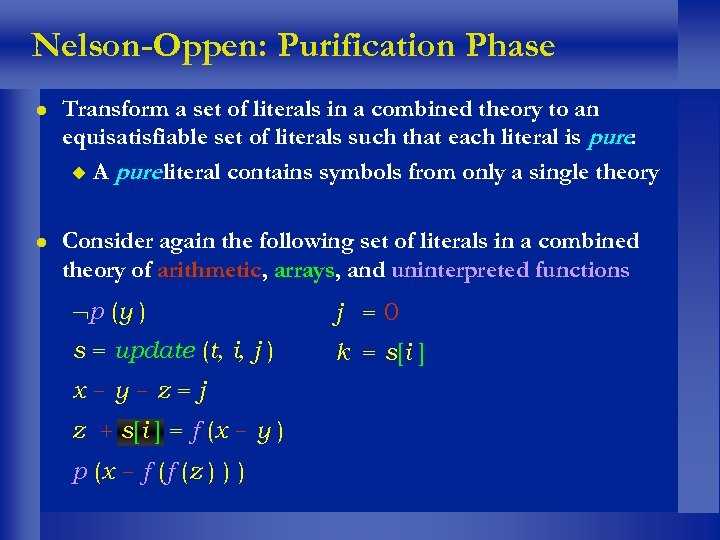

Nelson-Oppen: Purification Phase l Transform a set of literals in a combined theory to an equisatisfiable set of literals such that each literal is pure: u A pure literal contains symbols from only a single theory l Consider again the following set of literals in a combined theory of arithmetic, arrays, and uninterpreted functions p (y ) j =0 s = update (t, i, j ) k = s[i ] x-y-z=j z + s[i ] = f (x - y ) p (x - f (f (z ) ) )

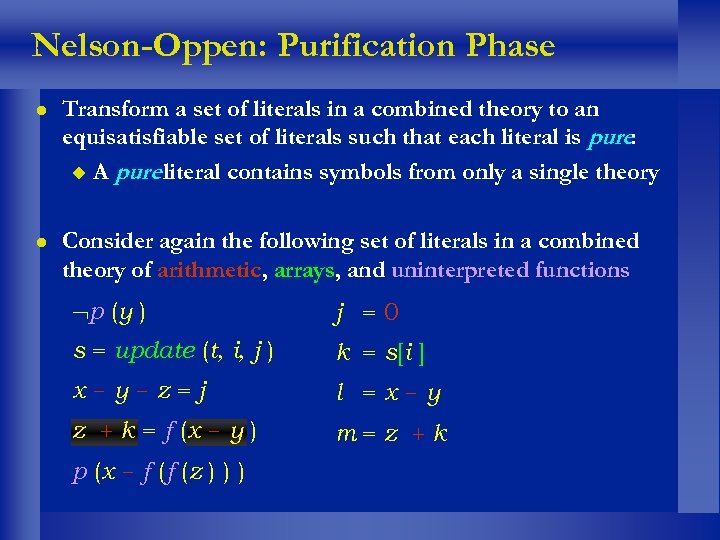

Nelson-Oppen: Purification Phase l Transform a set of literals in a combined theory to an equisatisfiable set of literals such that each literal is pure: u A pure literal contains symbols from only a single theory l Consider again the following set of literals in a combined theory of arithmetic, arrays, and uninterpreted functions p (y ) j =0 s = update (t, i, j ) k = s[i ] x-y-z=j l =x-y z + k = f (x - y ) m=z +k p (x - f (f (z ) ) )

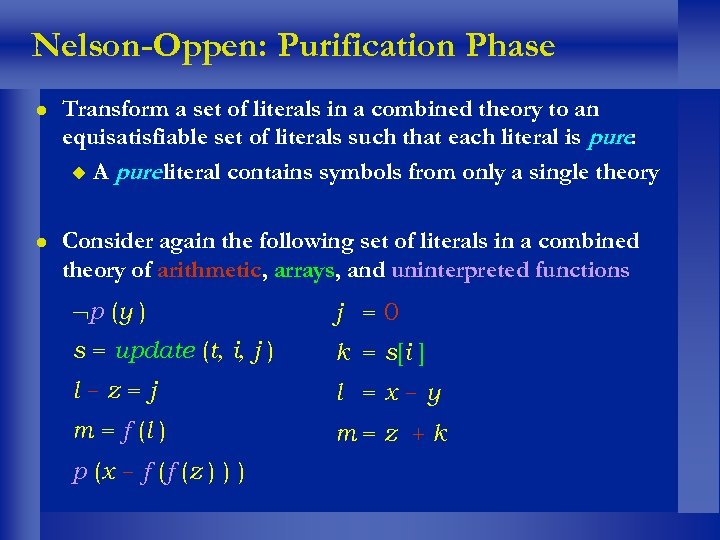

Nelson-Oppen: Purification Phase l Transform a set of literals in a combined theory to an equisatisfiable set of literals such that each literal is pure: u A pure literal contains symbols from only a single theory l Consider again the following set of literals in a combined theory of arithmetic, arrays, and uninterpreted functions p (y ) j =0 s = update (t, i, j ) k = s[i ] l-z=j l =x-y m = f (l ) m=z +k p (x - f (f (z ) ) )

Nelson-Oppen: Purification Phase l Transform a set of literals in a combined theory to an equisatisfiable set of literals such that each literal is pure: u A pure literal contains symbols from only a single theory l Consider again the following set of literals in a combined theory of arithmetic, arrays, and uninterpreted functions p (y ) j =0 s = update (t, i, j ) k = s[i ] l-z=j l =x-y m = f (l ) m=z +k p (v ) n = f (f (z ) ) ) v =x-n

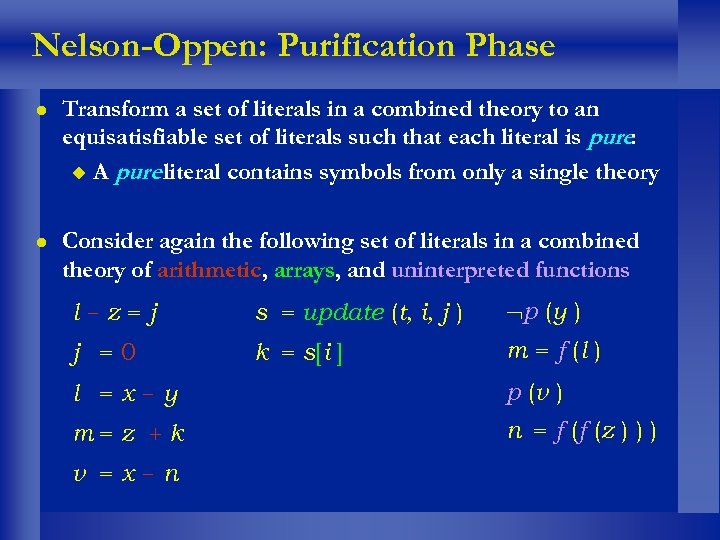

Nelson-Oppen: Purification Phase l Transform a set of literals in a combined theory to an equisatisfiable set of literals such that each literal is pure: u A pure literal contains symbols from only a single theory l Consider again the following set of literals in a combined theory of arithmetic, arrays, and uninterpreted functions l-z=j s = update (t, i, j ) p (y ) j =0 k = s[i ] m = f (l ) l =x-y p (v ) m=z +k n = f (f (z ) ) ) v =x-n

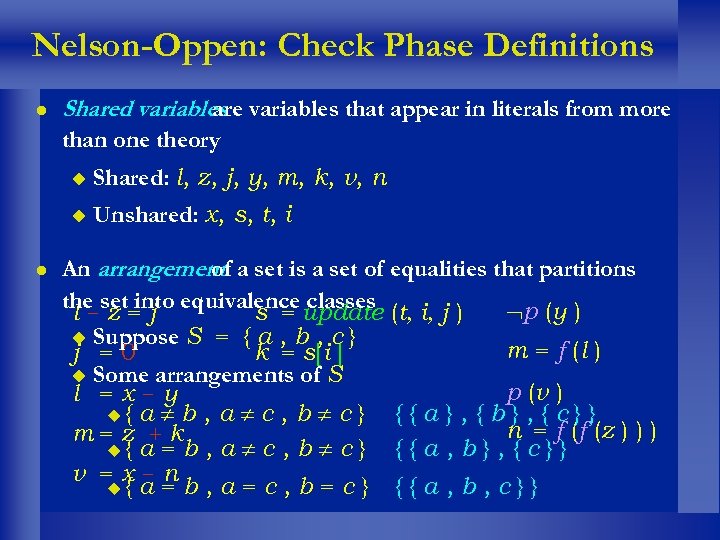

Nelson-Oppen: Check Phase Definitions l Shared variables that appear in literals from more are than one theory u u l Shared: l, z, j, y, m, k, v, n Unshared: x, s, t, i An arrangement a set is a set of equalities that partitions of the set into equivalence classes p (y ) s = update (t, i, j ) l-z=j u Suppose S = { a , b , c } m = f (l ) k = s[i ] j =0 u Some arrangements of S p (v ) l =x-y u{ a b , a c , b c } {{a}, {b}, {c}} n = f (f (z ) ) ) m=z +k u{ a = b , a c , b c } {{a, b}, {c}} v =x-n u{ a = b , a = c , b = c } {{a, b, c}}

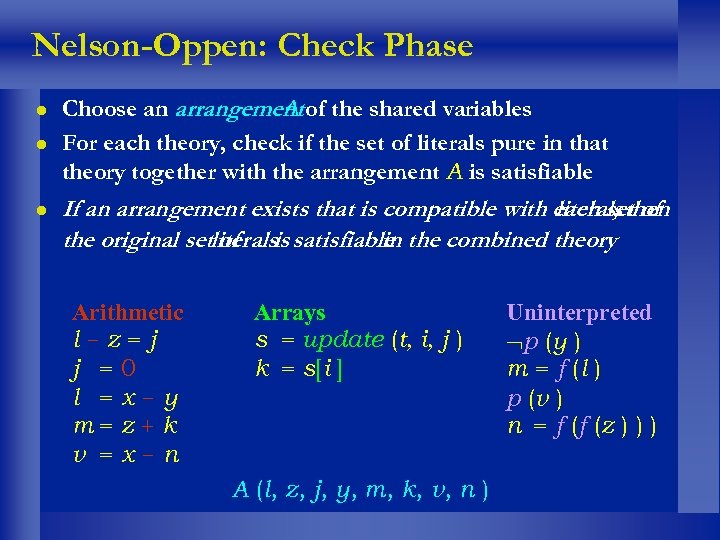

Nelson-Oppen: Check Phase l l l Choose an arrangement of the shared variables A For each theory, check if the set of literals pure in that theory together with the arrangement A is satisfiable If an arrangement exists that is compatible with each set of literals then , the original setliteralsis satisfiable the combined theory of in Arithmetic l-z=j j =0 l =x-y m=z+k v =x-n Arrays s = update (t, i, j ) k = s[i ] A (l, z, j, y, m, k, v, n ) Uninterpreted p (y ) m = f (l ) p (v ) n = f (f (z ) ) )

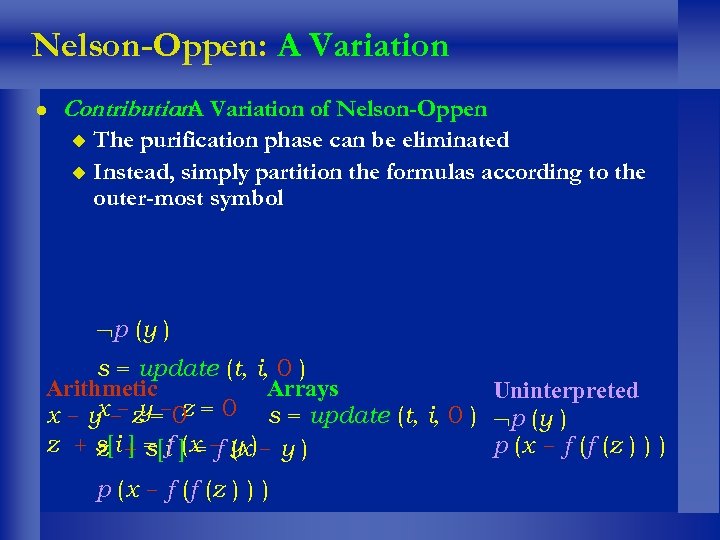

Nelson-Oppen: A Variation l Contribution. A Variation of Nelson-Oppen : The purification phase can be eliminated u Instead, simply partition the formulas according to the outer-most symbol u p (y ) s = update (t, i, 0 ) Arithmetic Arrays Uninterpreted x-y-z x - y - z = 0 s = update (t, i, 0 ) p (y ) z + s[i + = f ] =- y ) p (x - f (f (z ) ) ) z ] s[i (x f (x p (x - f (f (z ) ) )

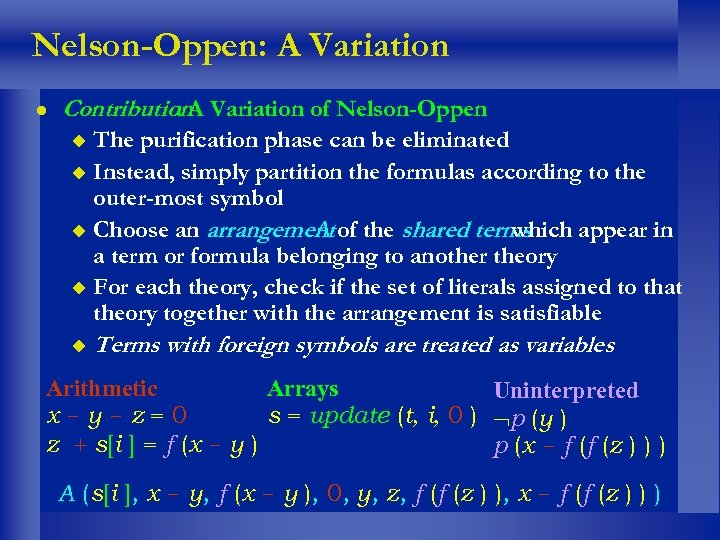

Nelson-Oppen: A Variation l Contribution. A Variation of Nelson-Oppen : The purification phase can be eliminated u Instead, simply partition the formulas according to the outer-most symbol u Choose an arrangement of the shared terms A which appear in a term or formula belonging to another theory u For each theory, check if the set of literals assigned to that theory together with the arrangement is satisfiable u u Terms with foreign symbols are treated as variables Arithmetic Arrays Uninterpreted x-y-z=0 s = update (t, i, 0 ) p (y ) z + s[i ] = f (x - y ) p (x - f (f (z ) ) ) A (s[i ], x - y, f (x - y ), 0, y, z, f (f (z ) ), x - f (f (z ) ) )

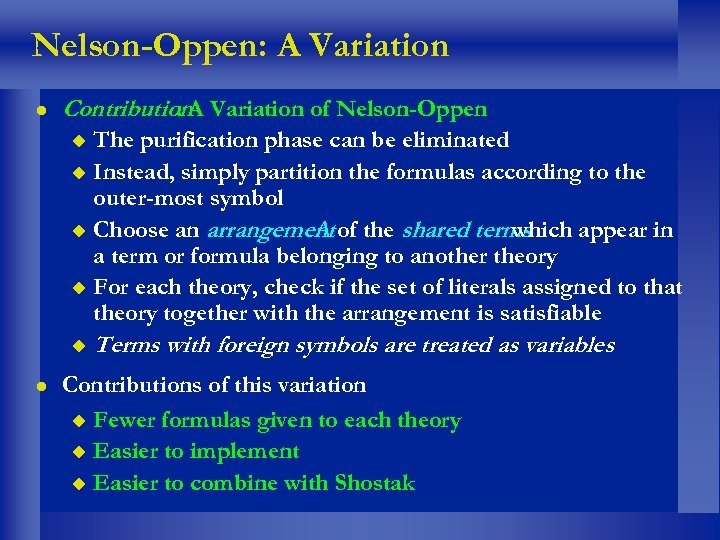

Nelson-Oppen: A Variation l Contribution. A Variation of Nelson-Oppen : The purification phase can be eliminated u Instead, simply partition the formulas according to the outer-most symbol u Choose an arrangement of the shared terms A which appear in a term or formula belonging to another theory u For each theory, check if the set of literals assigned to that theory together with the arrangement is satisfiable u u l Terms with foreign symbols are treated as variables Contributions of this variation u Fewer formulas given to each theory u Easier to implement u Easier to combine with Shostak

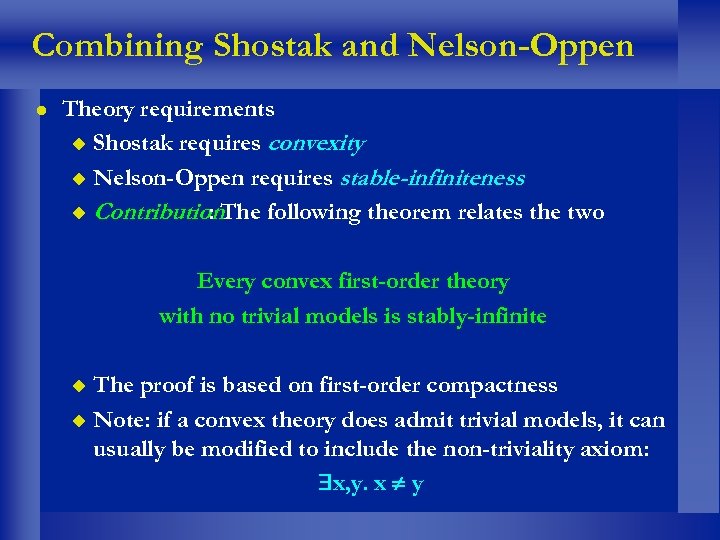

Combining Shostak and Nelson-Oppen l Theory requirements u Shostak requires convexity u Nelson-Oppen requires stable-infiniteness u Contribution : The following theorem relates the two Every convex first-order theory with no trivial models is stably-infinite The proof is based on first-order compactness u Note: if a convex theory does admit trivial models, it can usually be modified to include the non-triviality axiom: x, y. x y u

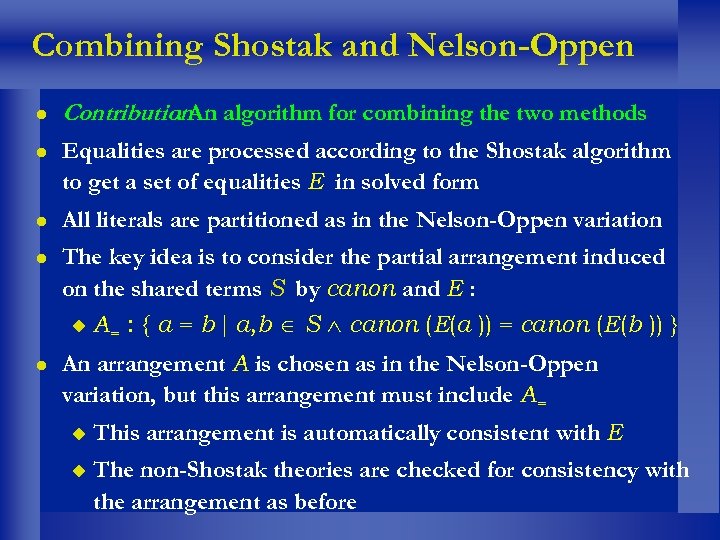

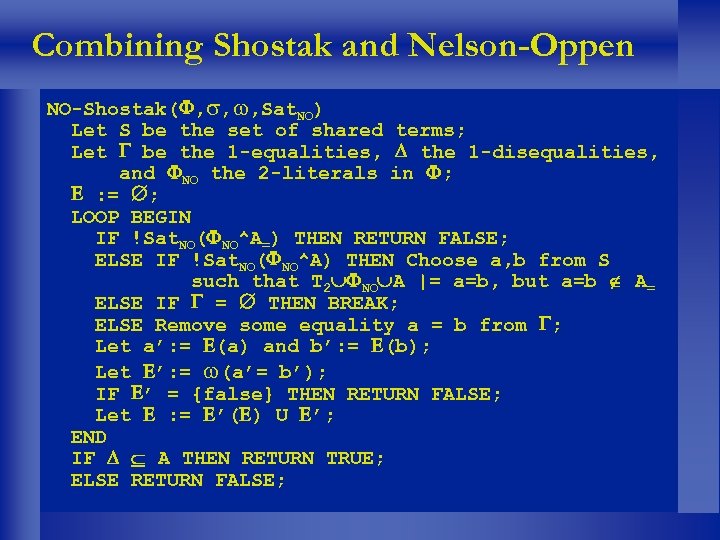

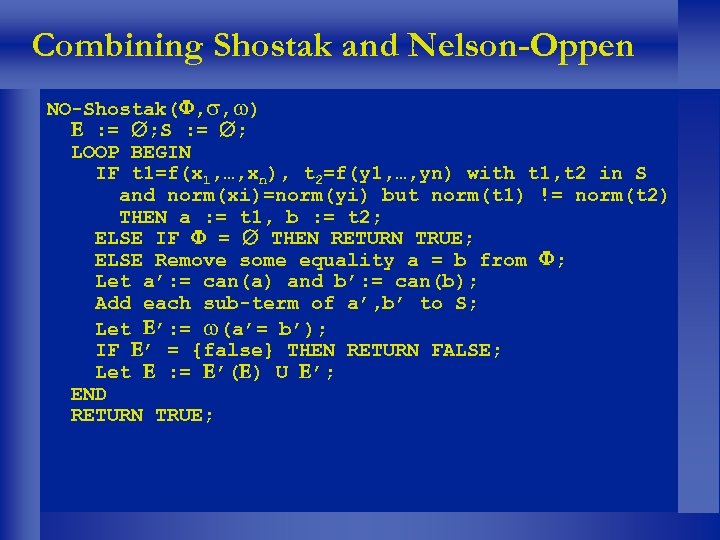

Combining Shostak and Nelson-Oppen l Contribution. An algorithm for combining the two methods : l Equalities are processed according to the Shostak algorithm to get a set of equalities E in solved form l All literals are partitioned as in the Nelson-Oppen variation l The key idea is to consider the partial arrangement induced on the shared terms S by canon and E : u l A= : { a = b a, b S canon (E(a )) = canon (E(b )) } An arrangement A is chosen as in the Nelson-Oppen variation, but this arrangement must include A= u This arrangement is automatically consistent with E u The non-Shostak theories are checked for consistency with the arrangement as before

Outline l Validity Checking Overview l Methods for Combining Theories l Implementation l Adapting Techniques from Propositional Satisfiability l Contributions and Conclusions

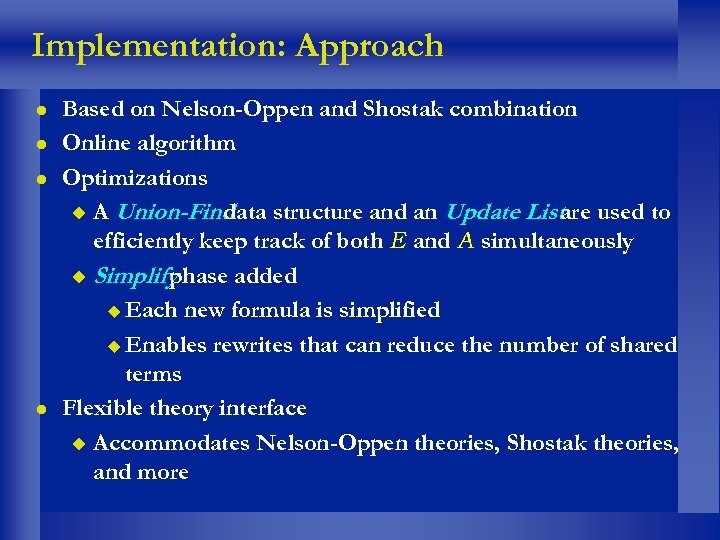

Implementation: Approach l l Based on Nelson-Oppen and Shostak combination Online algorithm Optimizations u A Union-Find data structure and an Update Listare used to efficiently keep track of both E and A simultaneously u Simplify phase added u Each new formula is simplified u Enables rewrites that can reduce the number of shared terms Flexible theory interface u Accommodates Nelson-Oppen theories, Shostak theories, and more

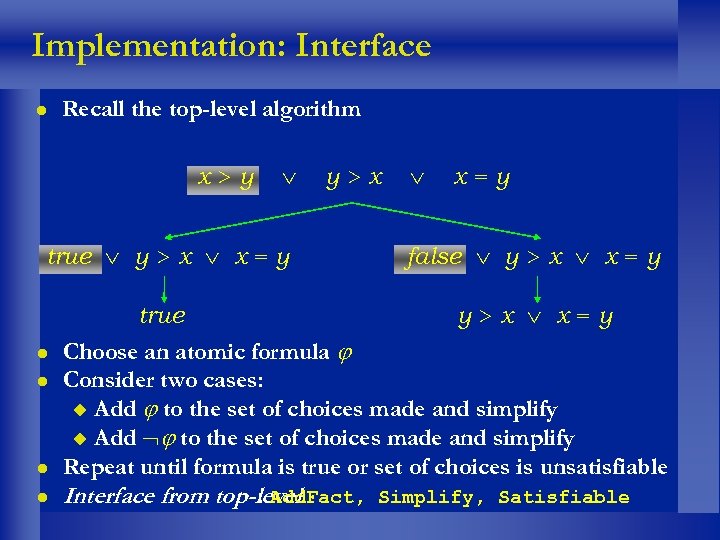

Implementation: Interface l Recall the top-level algorithm x>y true y > x x = y l l y>x x=y false y > x x = y true y>x x=y Choose an atomic formula Consider two cases: u Add to the set of choices made and simplify Repeat until formula is true or set of choices is unsatisfiable Interface from top-level : Add. Fact, Simplify, Satisfiable

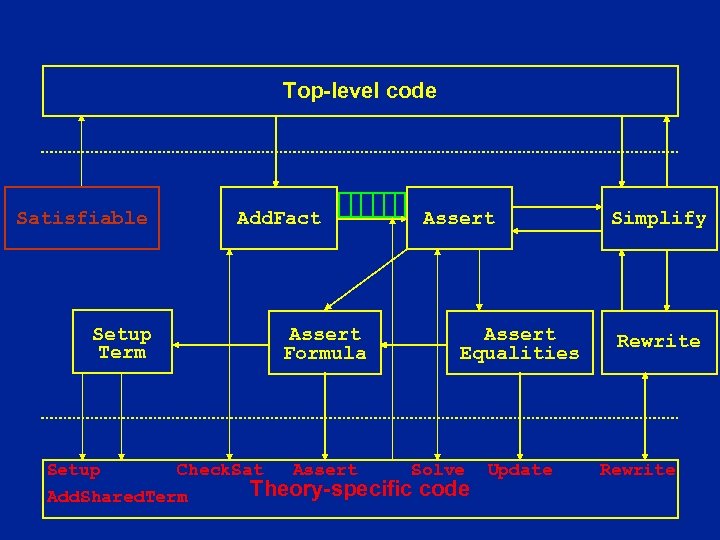

Top-level code Satisfiable Add. Fact Setup Term Setup Assert Formula Check. Sat Add. Shared. Term Assert Equalities Solve Theory-specific code Update Simplify Rewrite

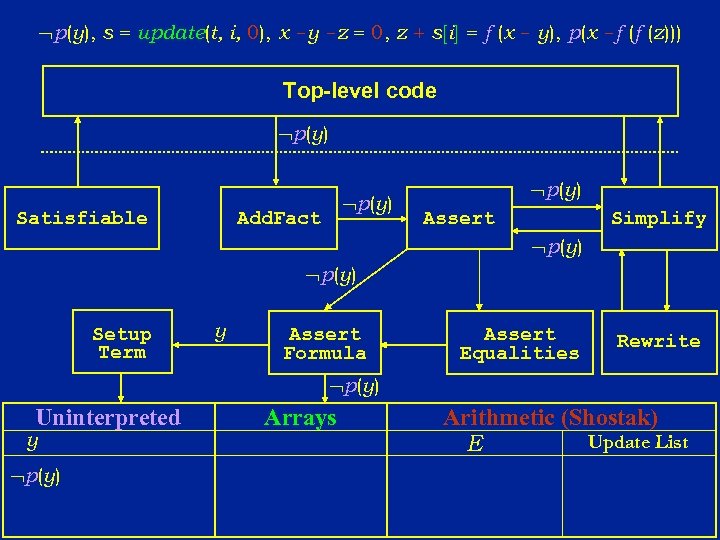

p(y), s = update(t, i, 0), x -y -z = 0, z + s[i] = f (x - y), p(x -f (f (z))) Top-level code p(y) Satisfiable p(y) Add. Fact p(y) Assert Simplify p(y) Setup Term y Assert Formula Assert Equalities Rewrite p(y) Uninterpreted y p(y) Arrays Arithmetic (Shostak) Update List E

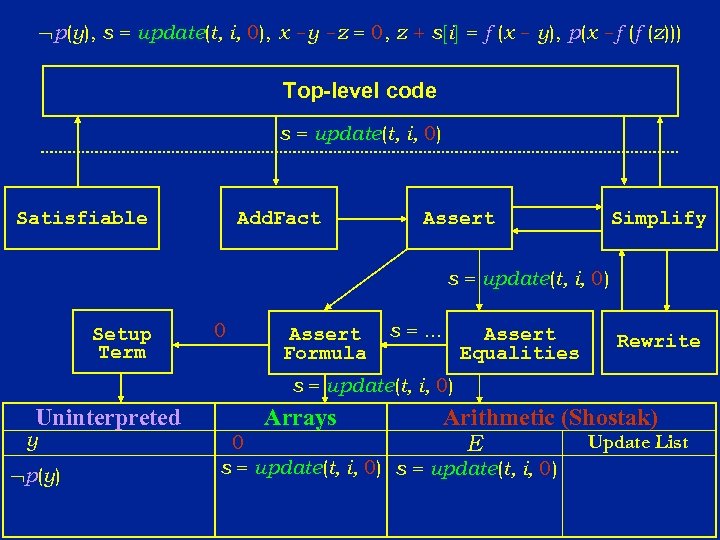

p(y), s = update(t, i, 0), x -y -z = 0, z + s[i] = f (x - y), p(x -f (f (z))) Top-level code s = update(t, i, 0) Satisfiable Add. Fact Assert Simplify s = update(t, i, 0) Setup Term 0 Assert Formula s =. . . Assert Equalities Rewrite s = update(t, i, 0) Uninterpreted y p(y) Arrays Arithmetic (Shostak) Update List E 0 s = update(t, i, 0)

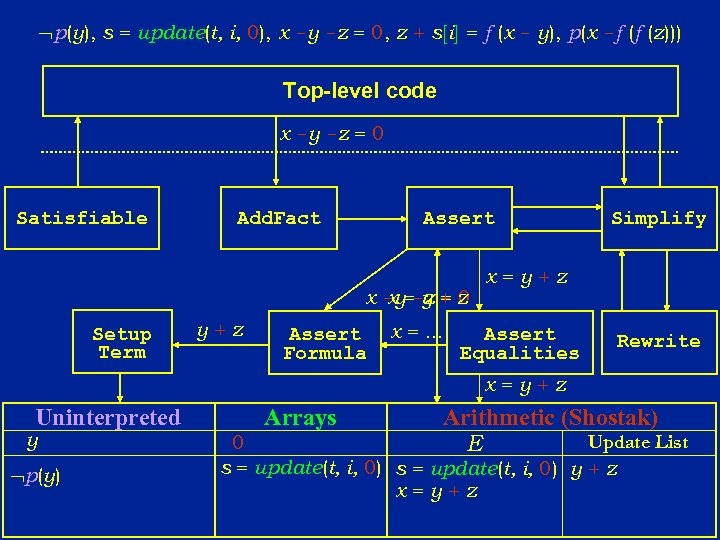

p(y), s = update(t, i, 0), x -y -z = 0, z + s[i] = f (x - y), p(x -f (f (z))) Top-level code x -y -z = 0 Satisfiable Assert Add. Fact x -y=-z + z x y=0 Setup Term y+z Assert Formula x =. . . Simplify x=y+z Assert Equalities Rewrite x=y+z Uninterpreted y p(y) Arrays Arithmetic (Shostak) Update List E 0 s = update(t, i, 0) y + z x=y+z

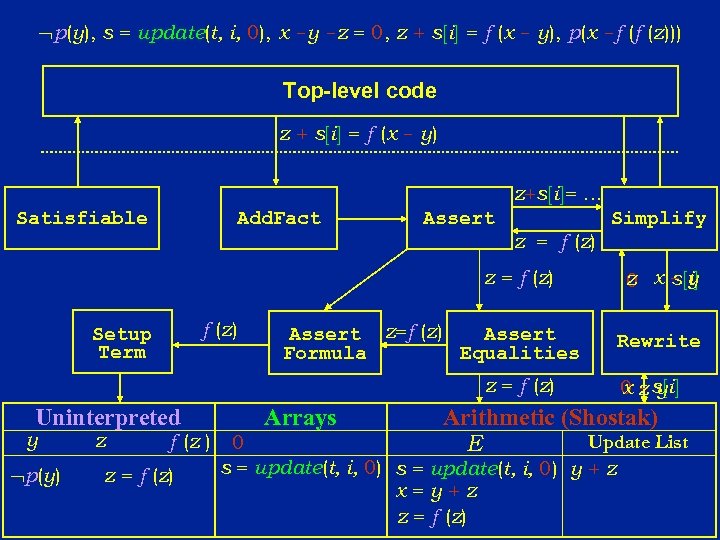

p(y), s = update(t, i, 0), x -y -z = 0, z + s[i] = f (x - y), p(x -f (f (z))) Top-level code z + s[i] = f (x - y) z+s[i]=. . . Satisfiable Add. Fact Assert z = f (z) Simplify z = f (z) Setup Term Assert z=f (z) Assert Formula Equalities z = f (z) Uninterpreted y p(y) z f (z ) z = f (z) Arrays s[i] z 0 x-y Rewrite x-y 0 z s[i] Arithmetic (Shostak) Update List E 0 s = update(t, i, 0) y + z x=y+z z = f (z)

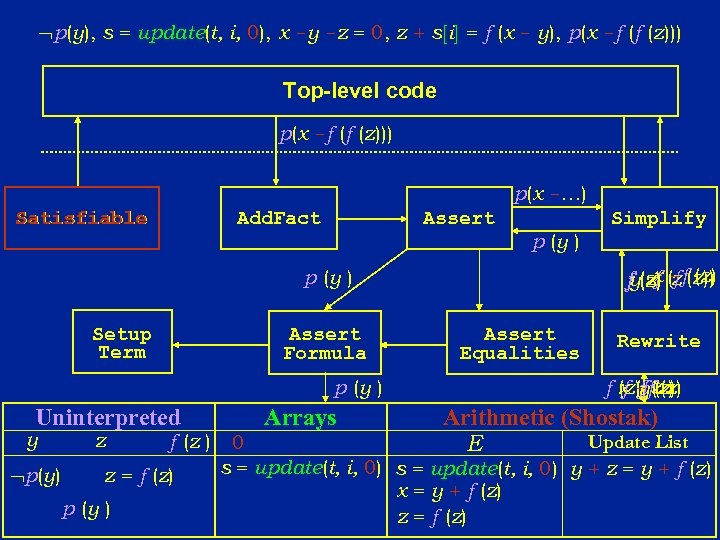

p(y), s = update(t, i, 0), x -y -z = 0, z + s[i] = f (x - y), p(x -f (f (z))) Top-level code p(x -f (f (z))) p(x -…) Satisfiable Assert Add. Fact p (y ) x -f (z) f z fy(z) (f (z)) p (y ) Setup Term Assert Formula p (y ) Uninterpreted y p(y) z f (z ) z = f (z) p (y ) Arrays Simplify Assert Equalities Rewrite f -f(z)) f x (f z(z) (z)y (z) f Arithmetic (Shostak) Update List E 0 s = update(t, i, 0) y + z = y + f (z) x = y + f (z) z = f (z)

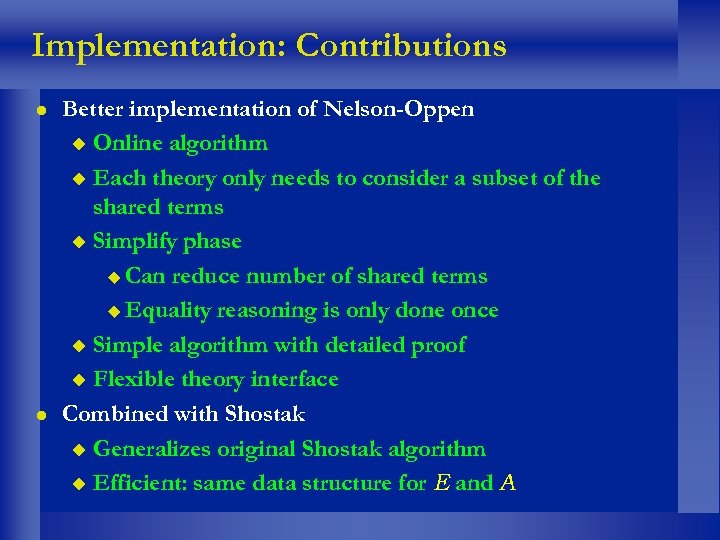

Implementation: Contributions l l Better implementation of Nelson-Oppen u Online algorithm u Each theory only needs to consider a subset of the shared terms u Simplify phase u Can reduce number of shared terms u Equality reasoning is only done once u Simple algorithm with detailed proof u Flexible theory interface Combined with Shostak u Generalizes original Shostak algorithm u Efficient: same data structure for E and A

Outline l Validity Checking Overview l Methods for Combining Theories l Implementation l Adapting Techniques from Propositional Satisfiability u u Combining with SAT u l The Problem Results Contributions and Conclusions

The Problem l Recall the top-level algorithm x>y true y > x x = y l l l y>x x=y false y > x x = y true y>x x=y Choose an atomic formula Consider two cases: u Add to the set of choices made and simplify Repeat until formula is true or set of choices is unsatisfiable

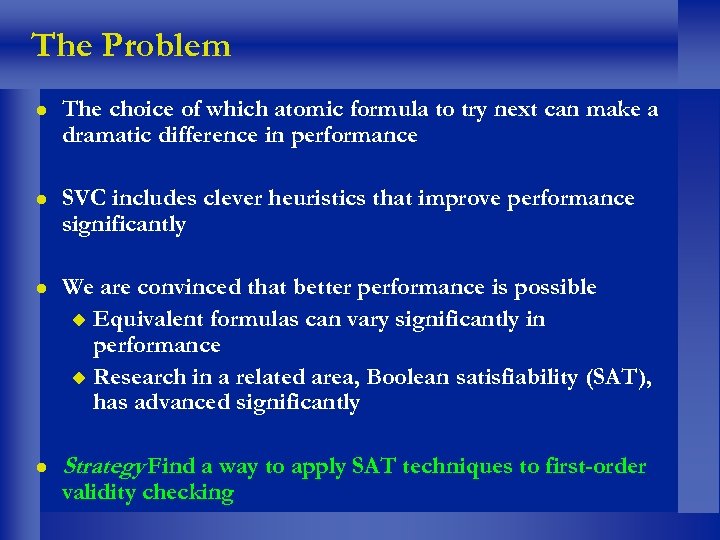

The Problem l The choice of which atomic formula to try next can make a dramatic difference in performance l SVC includes clever heuristics that improve performance significantly l We are convinced that better performance is possible u Equivalent formulas can vary significantly in performance u Research in a related area, Boolean satisfiability (SAT), has advanced significantly l Strategy Find a way to apply SAT techniques to first-order : validity checking

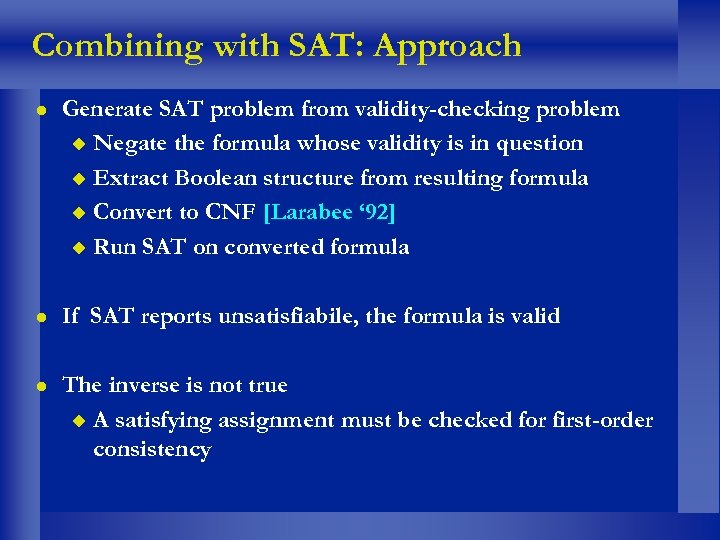

Combining with SAT: Approach l Generate SAT problem from validity-checking problem u Negate the formula whose validity is in question u Extract Boolean structure from resulting formula u Convert to CNF [Larabee ‘ 92] u Run SAT on converted formula l If SAT reports unsatisfiabile, the formula is valid l The inverse is not true u A satisfying assignment must be checked for first-order consistency

![Combining with SAT: Initial Results l Implementation u GRASP SAT engine [Silva ‘ 96] Combining with SAT: Initial Results l Implementation u GRASP SAT engine [Silva ‘ 96]](https://present5.com/presentation/570c1dccc9c99e2b6e327416ff71d2af/image-66.jpg)

Combining with SAT: Initial Results l Implementation u GRASP SAT engine [Silva ‘ 96] u SVC 2 l Initial results were disappointing u Examples of interest could not be proved by just considering Boolean structure u SAT techniques do not compensate for the loss of information resulting from translation to SAT l Idea: u Incrementally give SAT more information

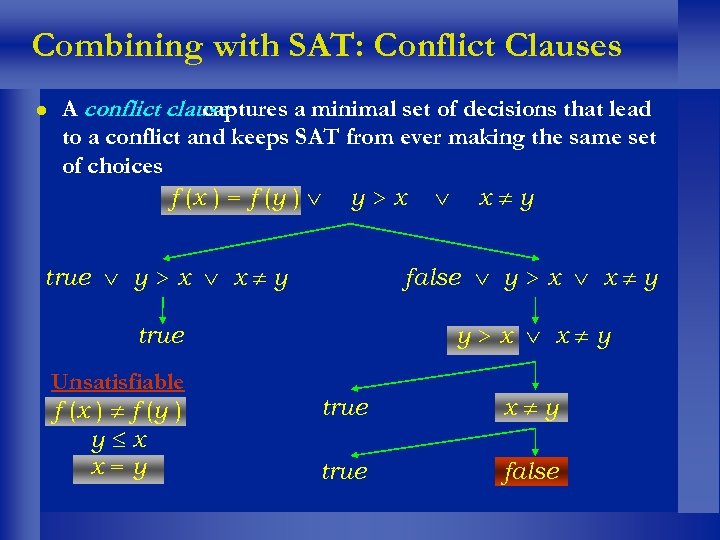

Combining with SAT: Conflict Clauses l A conflict clause captures a minimal set of decisions that lead to a conflict and keeps SAT from ever making the same set of choices f (x ) = f (y ) y > x x y true y > x x y false y > x x y true y>x x y Unsatisfiable f (x ) f (y ) y x x=y true x y true false

Combining with SAT: Conflict Clauses l How do we get a conflict clause from the first-order satisfiability algorithm u Using all decisions too slow u Black-box minimization methods too slow l Solution Use proof-production! : Aaron Stump has extended several SVC decision procedures to produce a proof for every result deduced u By looking at what assumptions are used in a proof of inconsistency, a conflict clause can be obtained u

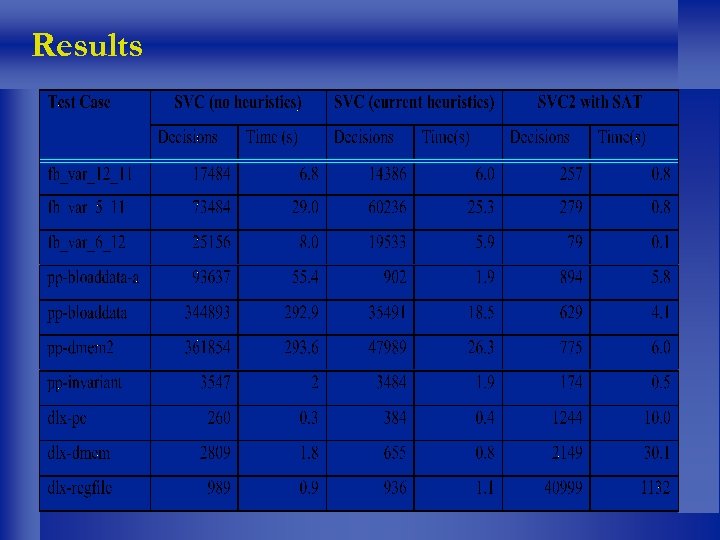

Results

Results: Preliminary Conclusions l Naïve approach does not work well l Adding conflict clauses results in dramatic speed-ups on several examples l Most helpful on formulas with more Boolean structure l Still more work to be done u Find out source of performance problems u Compare to related work u [Goel et al. ‘ 98] u [Bryant et al. ‘ 99]

Outline l Validity Checking Overview l Methods for Combining Theories l Implementation l Adapting Techniques from Propositional Satisfiability l Contributions and Conclusions

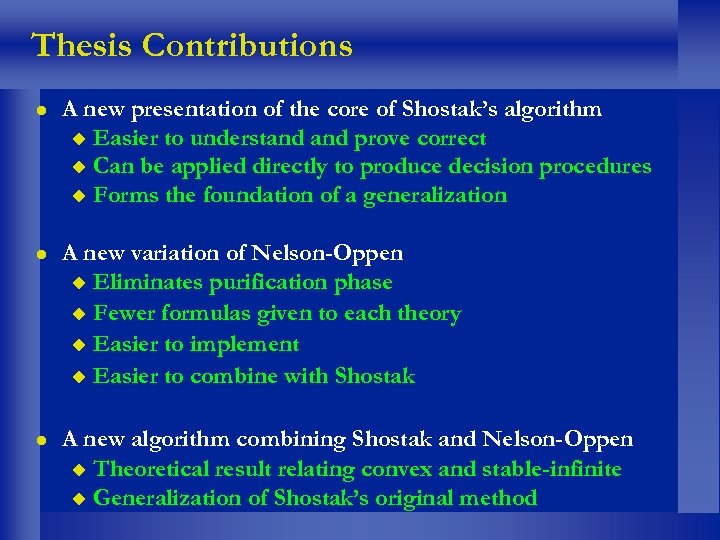

Thesis Contributions l A new presentation of the core of Shostak’s algorithm u Easier to understand prove correct u Can be applied directly to produce decision procedures u Forms the foundation of a generalization l A new variation of Nelson-Oppen u Eliminates purification phase u Fewer formulas given to each theory u Easier to implement u Easier to combine with Shostak l A new algorithm combining Shostak and Nelson-Oppen u Theoretical result relating convex and stable-infinite u Generalization of Shostak’s original method

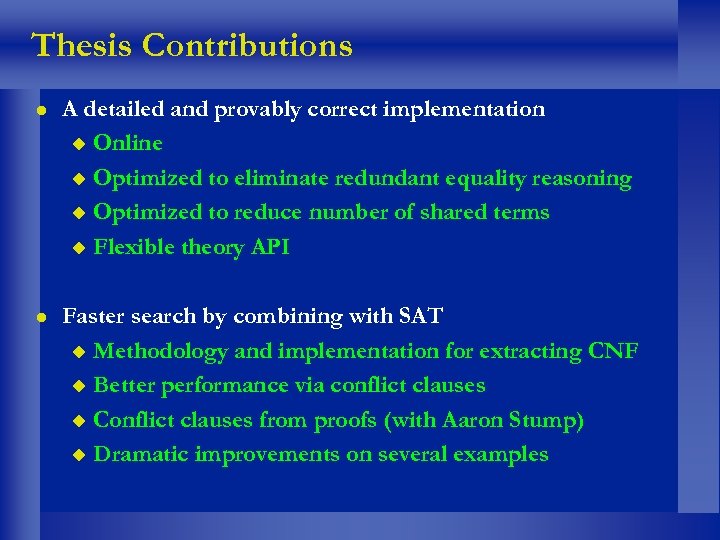

Thesis Contributions l A detailed and provably correct implementation u Online u Optimized to eliminate redundant equality reasoning u Optimized to reduce number of shared terms u Flexible theory API l Faster search by combining with SAT u Methodology and implementation for extracting CNF u Better performance via conflict clauses u Conflict clauses from proofs (with Aaron Stump) u Dramatic improvements on several examples

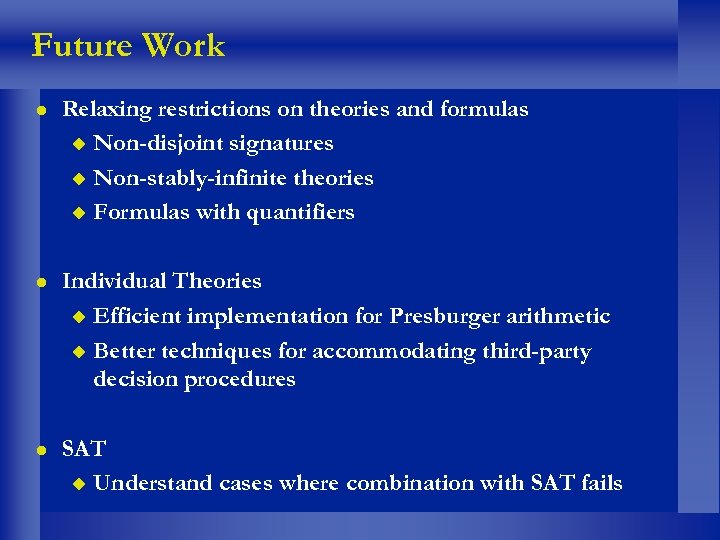

Future Work l Relaxing restrictions on theories and formulas u Non-disjoint signatures u Non-stably-infinite theories u Formulas with quantifiers l Individual Theories u Efficient implementation for Presburger arithmetic u Better techniques for accommodating third-party decision procedures l SAT u Understand cases where combination with SAT fails

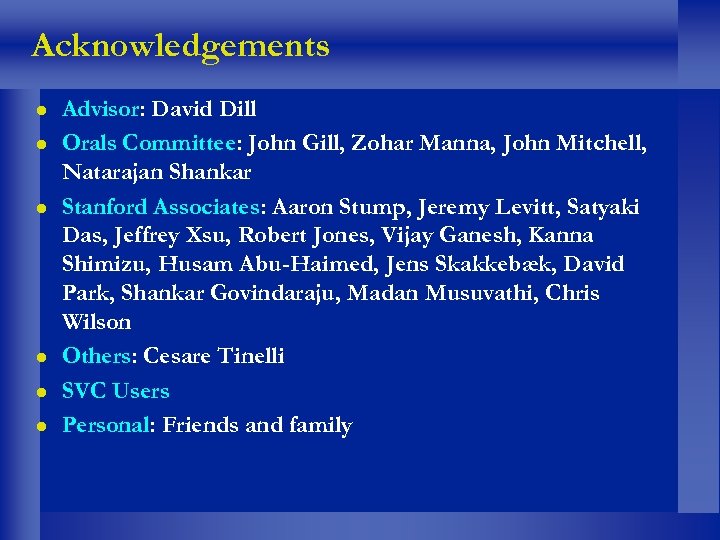

Acknowledgements l l l Advisor: David Dill Orals Committee: John Gill, Zohar Manna, John Mitchell, Natarajan Shankar Stanford Associates: Aaron Stump, Jeremy Levitt, Satyaki Das, Jeffrey Xsu, Robert Jones, Vijay Ganesh, Kanna Shimizu, Husam Abu-Haimed, Jens Skakkebæk, David Park, Shankar Govindaraju, Madan Musuvathi, Chris Wilson Others: Cesare Tinelli SVC Users Personal: Friends and family

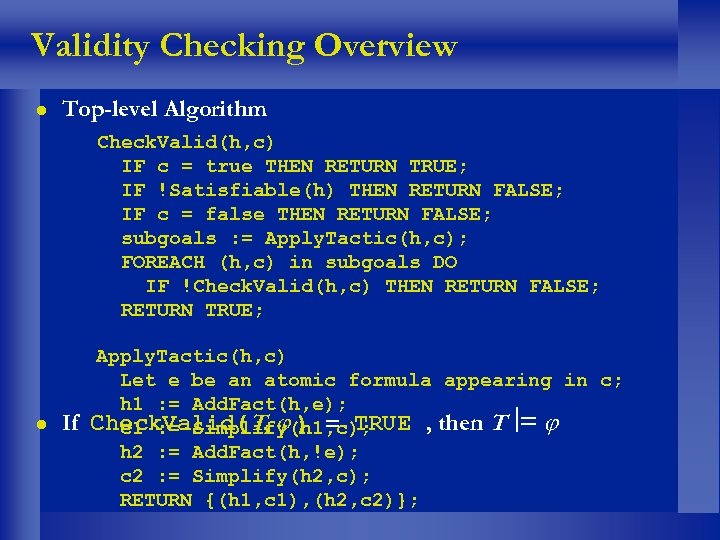

Validity Checking Overview l Top-level Algorithm Check. Valid(h, c) IF c = true THEN RETURN TRUE; Check. Valid(h, c) IF !Satisfiable(h) THEN RETURN FALSE; IF c = true THEN RETURN TRUE; IF c = false THEN RETURN FALSE; IF !Satisfiable(h) THEN RETURN FALSE; subgoals : = Apply. Tactic(h, c); IF c = false THEN subgoals. FALSE; FOREACH (h, c) in RETURN DO subgoals : = Apply. Tactic(h, c); IF !Check. Valid(h, c) THEN RETURN FALSE; FOREACHTRUE; in subgoals DO RETURN (h, c) IF !Check. Valid(h, c) THEN RETURN FALSE; RETURN TRUE; Apply. Tactic(h, c) l If Let e be an atomic formula appearing in c; h 1 : = Add. Fact(h, e); Check. Valid(T, ) = TRUE , then T = c 1 : = Simplify(h 1, c); h 2 : = Add. Fact(h, !e); c 2 : = Simplify(h 2, c); RETURN {(h 1, c 1), (h 2, c 2)};

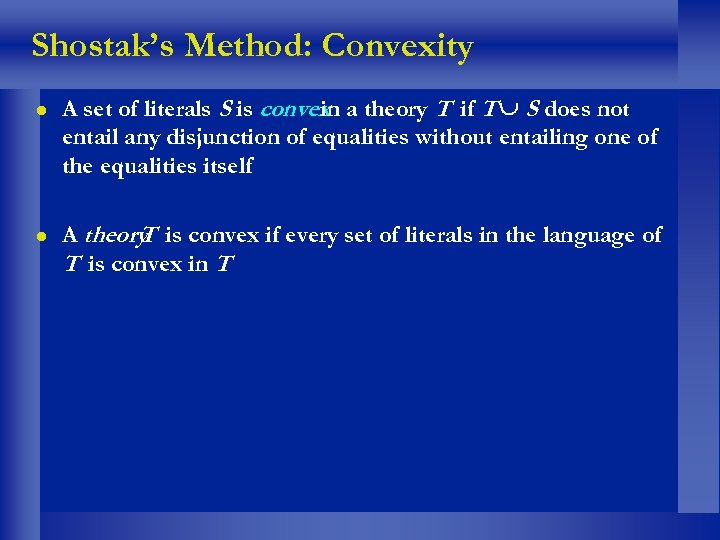

Shostak’s Method: Convexity l l A set of literals S is convex a theory T if T S does not in entail any disjunction of equalities without entailing one of the equalities itself A theory is convex if every set of literals in the language of T T is convex in T

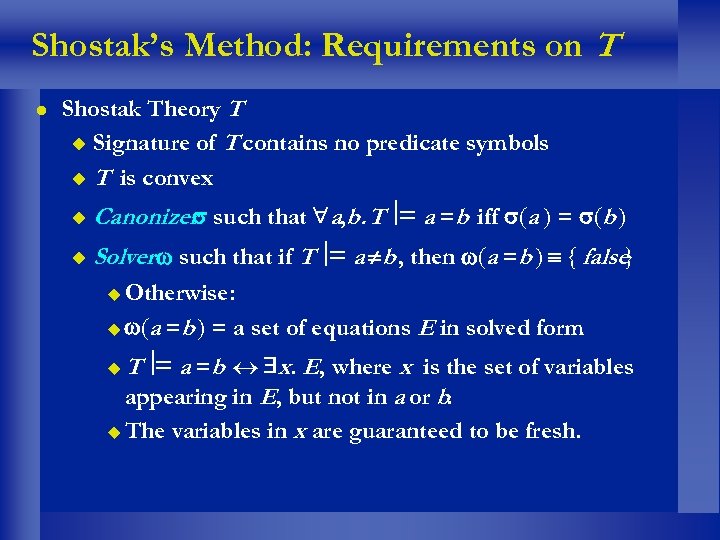

Shostak’s Method: Requirements on T l Shostak Theory T u Signature of T contains no predicate symbols u T is convex u Canonizer such that a, b. T = a =b iff a = b u Solver such that if T = a b , then a =b { false} Otherwise: u a =b = a set of equations E in solved form u T = a =b x. E, where x is the set of variables appearing in E, but not in a or b. u The variables in x are guaranteed to be fresh. u

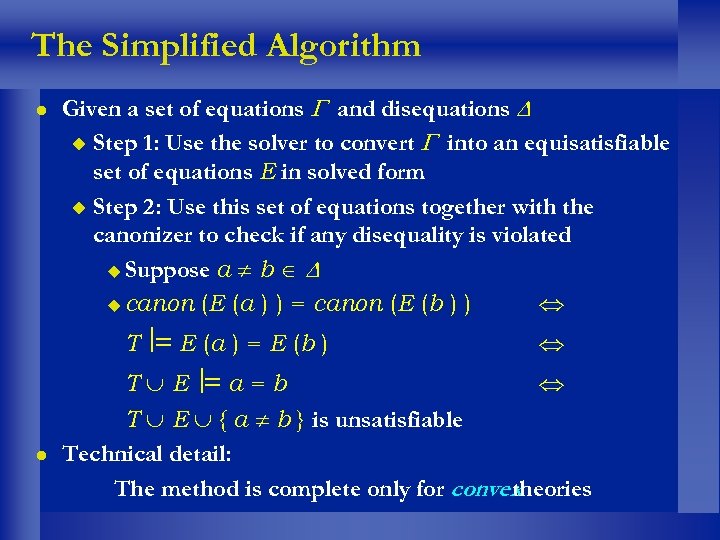

The Simplified Algorithm l Given a set of equations and disequations u Step 1: Use the solver to convert into an equisatisfiable set of equations E in solved form u Step 2: Use this set of equations together with the canonizer to check if any disequality is violated u Suppose a b u canon (E (a ) ) = canon (E (b ) ) T = E (a ) = E (b ) l T E = a = b T E { a b } is unsatisfiable Technical detail: The method is complete only for convex theories

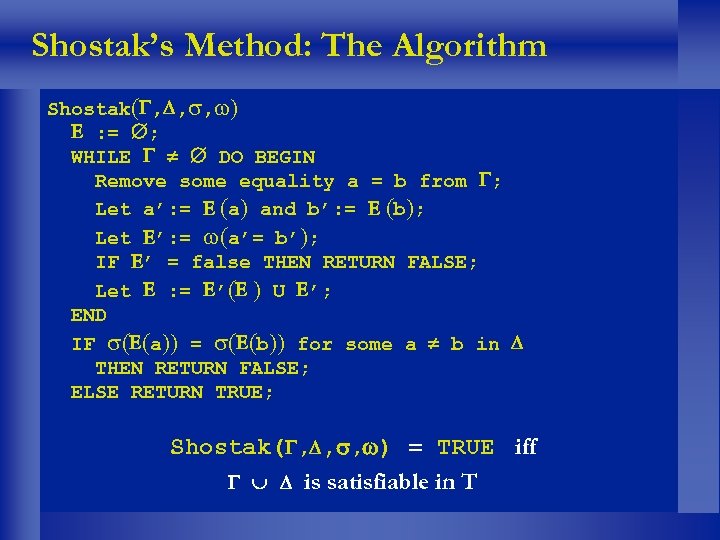

Shostak’s Method: The Algorithm Shostak , , , : = ; WHILE DO BEGIN Remove some equality a = b from ; Let a’: = a and b’: = b ; Let ’: = a’= b’ ; IF ’ = false THEN RETURN FALSE; Let : = ’ U ’; END IF a = b for some a b in THEN RETURN FALSE; ELSE RETURN TRUE; Shostak( , , , ) = TRUE iff is satisfiable in T

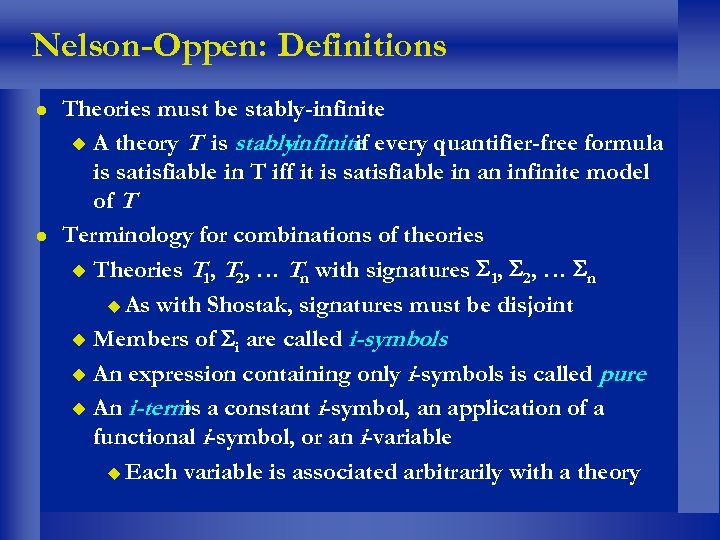

Nelson-Oppen: Definitions l l Theories must be stably-infinite u A theory T is stablyinfinite every quantifier-free formula if is satisfiable in T iff it is satisfiable in an infinite model of T Terminology for combinations of theories u Theories T 1, T 2, … Tn with signatures 1, 2, … n u As with Shostak, signatures must be disjoint u Members of i are called i-symbols u An expression containing only i-symbols is called pure u An i-term a constant i-symbol, an application of a is functional i-symbol, or an i-variable u Each variable is associated arbitrarily with a theory

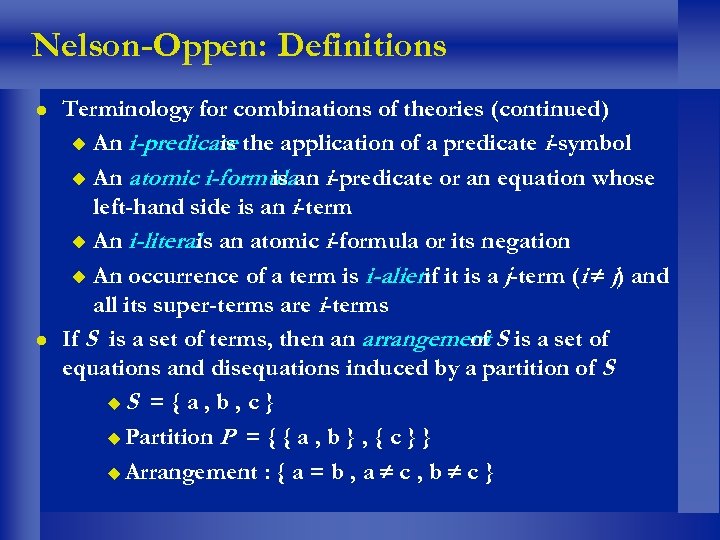

Nelson-Oppen: Definitions l l Terminology for combinations of theories (continued) u An i-predicate the application of a predicate i-symbol is u An atomic i-formula is an i-predicate or an equation whose left-hand side is an i-term u An i-literal an atomic i-formula or its negation is u An occurrence of a term is i-alien it is a j-term (i j) and if all its super-terms are i-terms If S is a set of terms, then an arrangement S is a set of of equations and disequations induced by a partition of S u. S = { a , b , c } u Partition P = { { a , b } , { c } } u Arrangement : { a = b , a c , b c }

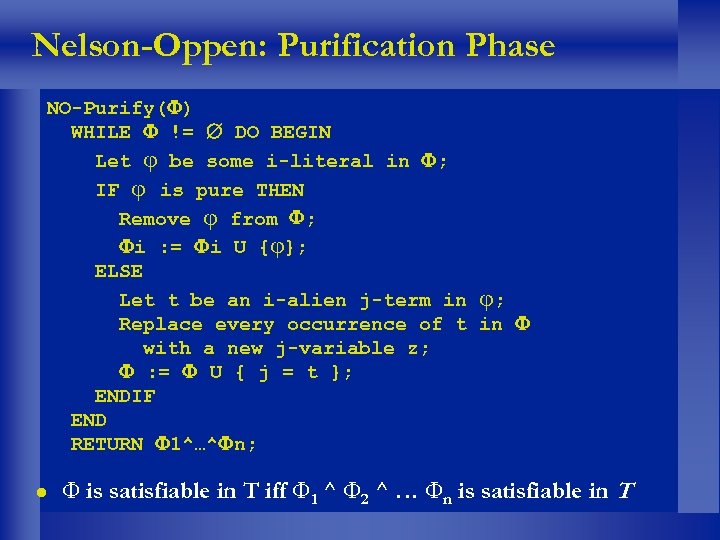

Nelson-Oppen: Purification Phase NO-Purify( ) WHILE != DO BEGIN Let be some i-literal in ; IF is pure THEN Remove from ; i : = i U { }; ELSE Let t be an i-alien j-term in ; Replace every occurrence of t in with a new j-variable z; : = U { j = t }; ENDIF END RETURN 1^…^ n; l is satisfiable in T iff 1 ^ 2 ^ … n is satisfiable in T

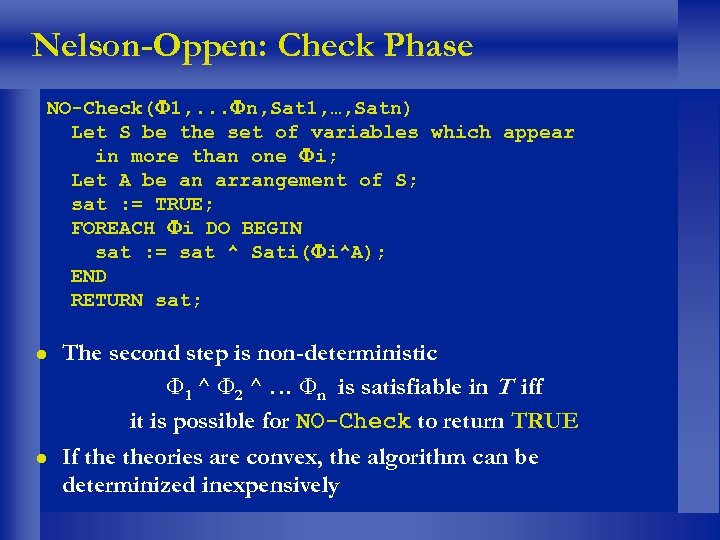

Nelson-Oppen: Check Phase NO-Check( 1, . . . n, Sat 1, …, Satn) Let S be the set of variables which appear in more than one i; Let A be an arrangement of S; sat : = TRUE; FOREACH i DO BEGIN sat : = sat ^ Sati( i^A); END RETURN sat; l l The second step is non-deterministic 1 ^ 2 ^ … n is satisfiable in T iff it is possible for NO-Check to return TRUE If theories are convex, the algorithm can be determinized inexpensively

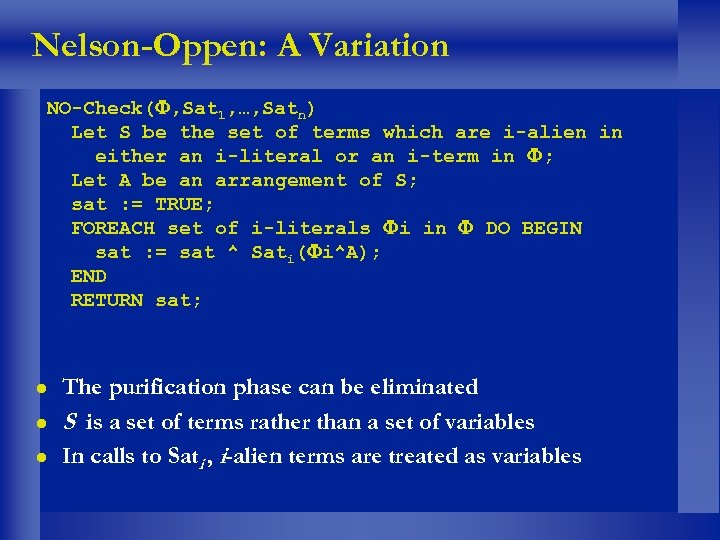

Nelson-Oppen: A Variation NO-Check( , Sat 1, …, Satn) Let S be the set of terms which are i-alien in either an i-literal or an i-term in ; Let A be an arrangement of S; sat : = TRUE; FOREACH set of i-literals i in DO BEGIN sat : = sat ^ Sati( i^A); END RETURN sat; l l l The purification phase can be eliminated S is a set of terms rather than a set of variables In calls to Sati , i-alien terms are treated as variables

Combining Shostak and Nelson-Oppen NO-Shostak( , , , Sat. NO) Let S be the set of shared terms; Let be the 1 -equalities, the 1 -disequalities, and NO the 2 -literals in ; : = ; LOOP BEGIN IF !Sat. NO( NO^A=) THEN RETURN FALSE; ELSE IF !Sat. NO( NO^A) THEN Choose a, b from S such that T 2 NO A |= a=b, but a=b A= ELSE IF = THEN BREAK; ELSE Remove some equality a = b from ; Let a’: = (a) and b’: = (b); Let ’: = (a’= b’); IF ’ = {false} THEN RETURN FALSE; Let : = ’( ) U ’; END IF A THEN RETURN TRUE; ELSE RETURN FALSE;

Combining Shostak and Nelson-Oppen NO-Shostak( , , ) : = ; S : = ; LOOP BEGIN IF t 1=f(x 1, …, xn), t 2=f(y 1, …, yn) with t 1, t 2 in S and norm(xi)=norm(yi) but norm(t 1) != norm(t 2) THEN a : = t 1, b : = t 2; ELSE IF = THEN RETURN TRUE; ELSE Remove some equality a = b from ; Let a’: = can(a) and b’: = can(b); Add each sub-term of a’, b’ to S; Let ’: = (a’= b’); IF ’ = {false} THEN RETURN FALSE; Let : = ’( ) U ’; END RETURN TRUE;

Individual Theories l SVC contains decision procedures for a number of individual theories u Pure equality with uninterpreted functions u Real linear arithmetic u Arrays u Bit-vectors u Records l In our efforts to revisit and improve these decision procedures, a number of interesting issues were uncovered u Finite domains u Strategies for arithmetic

Finite Domains l Theoretical technicalitiy u Cannot directly combine a theory with only finite models u Not stably-infinite u Union of theories likely to actually be inconsistent u Solution: Form an extended theory whose relativized reduct with respect to a new predicate P is theory with a finite domain. l Implementation strategy for nonconvexity u Keep track of the terms for which P holds u Use graph coloring to determine satisfiability

Arithmetic l l Suppose we want to handle linear arithmetic formulas with mixed variable types: some real and some integer. One approach is the following: u Split weak inequalities into the disjunction of an equation and a strong inequality u Use Shostak-style solver to eliminate all equations that can be solved for a real variable u Use Fourier-Motzkin techniques to eliminate all real variables from inequalities u Eliminate disequalities which can be solved for a real variable u What’s left can be done with Presburger decision procedures

Math symbols ()

570c1dccc9c99e2b6e327416ff71d2af.ppt