243877867114f952c55b16bce9a70b2e.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 42

Chapter Four Trade, Distribution, and Welfare Copyright © 2003 South-Western/Thomson Learning

Chapter Four Outline 1. Introduction 2. Partial and General Equilibrium Analysis 3. Stolper-Samuelson Theorem 4. Factor Price Equalization Theorem 5. Specific Factors Model 6. Trade and Welfare: Gainers, Losers, and Compensation 2

Introduction • Time to examine some of the major contributions international trade theory has made to general-equilibrium analysis. – We will look at the primary reason for the controversy between policies of free trade and policies of protectionism. 3

Partial and General Equilibrium Analysis • General-equilibrium analysis – Interrelationships among various markets in the economy. • Extreme example would be a model of a world economy that includes every good, every input, and every country and in which everything depended on everything else. • Partial-equilibrium analysis – Focuses on events in one or two markets and assumes others remain unaffected. • Simple example: analysis of effect of a Florida freeze on prices of orange juice. 4

Effect of Output Prices on Factor Prices • Stolper-Samuelson Theorem – Link between changes in output prices and changes in factor prices. – Most general form: an increase in the relative price of a good increases the real return to the factor used intensively in that good’s production and decreases the real return to the other factor. • Factor prices change proportionally more than output prices (magnification effect). 5

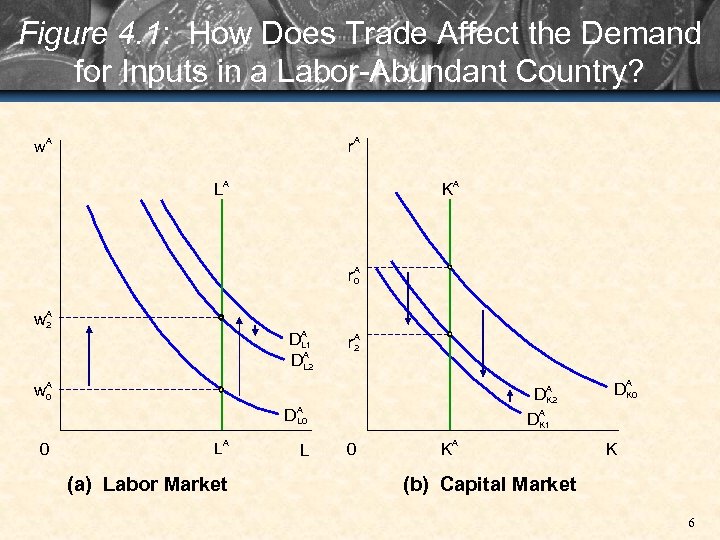

Figure 4. 1: How Does Trade Affect the Demand for Inputs in a Labor-Abundant Country? r. A w. A LA KA r. A 0 w. A 2 DA L 1 DA L 2 r. A 2 w. A 0 A K 2 D DA K 1 A L 0 D 0 LA (a) Labor Market L 0 KA DA K 0 K (b) Capital Market 6

Effect of Output Prices on Factor Prices • In Figure 4. 1, as production of the laborintensive good increases, opening trade generates a net increase in demand for labor. – Net effect on demand for capital is negative, because production of the capital-intensive good falls. – With fixed factor endowments, the reward paid to the abundant factor rises and that paid to the scarce factor falls. • The wage-rental ratio under restricted trade exceeds the ratio under autarky. 7

Effect of Output Prices on Factor Prices • When assumptions of Heckscher-Ohlin model are added, the Stolper-Samuelson theorem means that opening trade raises the real reward to the abundant factor and lowers the real reward to the scarce factor. – Trade boosts production of the good of comparative advantage, increasing that good’s opportunity cost and relative price. • See Table 4. 1 for trade’s effects on production, output prices, and factor prices. 8

How Do Factor Prices Vary Across Countries? • The Factor Price Equalization Theorem – According to Stolper-Samuelson theorem, moving from autarky to unrestricted trade raises the real reward of the abundant factor. • Similarly, such a move lowers the real reward of the scarce factor. • Same adjustment takes place in the second country, but with the roles of the two factors reversed. – Trade raises the real reward of a factor in a country where that factor is abundant and lowers its price in the country where it is scarce. 9

How Do Factor Prices Vary Across Countries? – Thus, even when factors are immobile between the two countries, unrestricted trade in goods tends to equalize the price of each factor across countries. • With free trade in goods and no international factor mobility, w. A = w. B and r. A = r. B. – This is idea behind Factor Price Equalization Theorem. • Table 4. 2 (page 111) summarizes theorem’s implications, assuming country A is labor-abundant and good X is labor intensive. 10

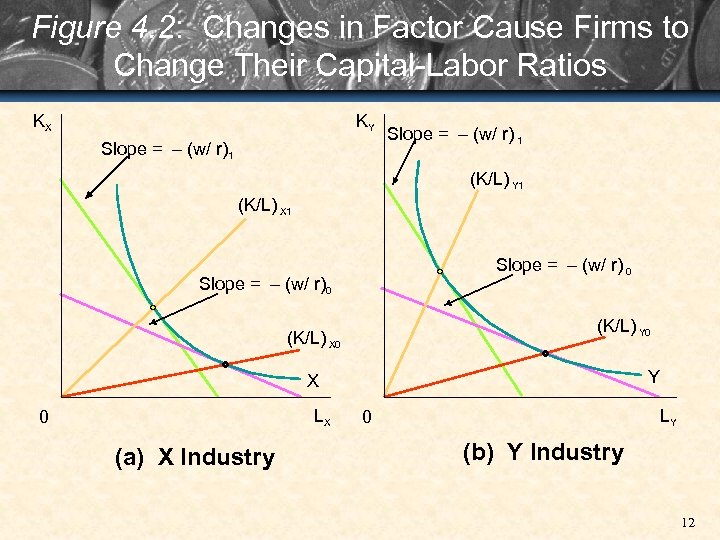

How Do Factor Prices Vary Across Countries? • Figure 4. 2 illustrates how a firm’s costminimizing production techniques change. – To increase production of the labor-intensive good (X), firms in both industries must increase their capital-labor ratios. • The rise in wage-rental ratio from (w/r)0 to (w/r)1 brings about this adjustment. – Firms choose to use less labor and more capital as labor becomes more expensive relative to capital. 11

Figure 4. 2: Changes in Factor Cause Firms to Change Their Capital-Labor Ratios KX KY Slope = – (w/ r)1 Slope = – (w/ r) 1 (K/L) Y 1 (K/L) X 1 Slope = – (w/ r) 0 Slope = – (w/ r)0 (K/L) Y 0 (K/L) X 0 Y X LX 0 (a) X Industry LY 0 (b) Y Industry 12

How Do Factor Prices Vary Across Countries? • The factor price changes predicted by the factor price equalization theorem provide the firm an incentive to undertake the necessary changes in production techniques. – Profit-maximizing firms will choose to use more of the scarce factor as it becomes relatively cheaper and less of the abundant factor as it becomes relatively more expensive. • This “economizing” on use of the abundant factor allows the country to specialize in producing the comparative advantage good. 13

An Alternate View of Factor Price Equalization • Trade in outputs serves as a “substitute” for trade in factors of production. – For example, when a labor-abundant country exports a unit of a labor-intensive good, it indirectly exports labor to a labor-scarce country. • Unrestricted trade in either output or input markets can serve as a substitute for trade in the other markets. 14

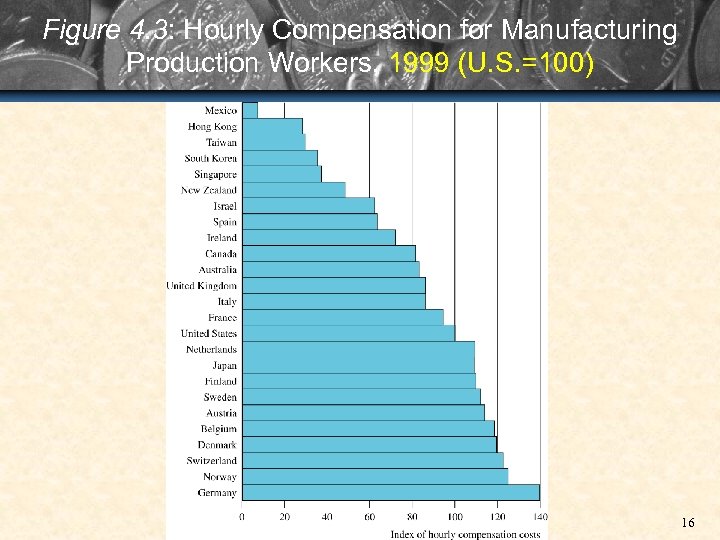

Why Don’t We Observe Factor Price Equalization? • Full factor price equalization is never observed. – In Figure 4. 3, it is shown that wages, before corrections for differences in labor productivity, differ widely across countries (by a factor of 20). • Reason #1: Uneven ownership of human and nonhuman capital yields inequality of wealth. • Reason #2: Not all countries use identical technology in production…some are more advanced than others. – Causes factor productivity to vary across countries. 15

Figure 4. 3: Hourly Compensation for Manufacturing Production Workers, 1999 (U. S. =100) 16

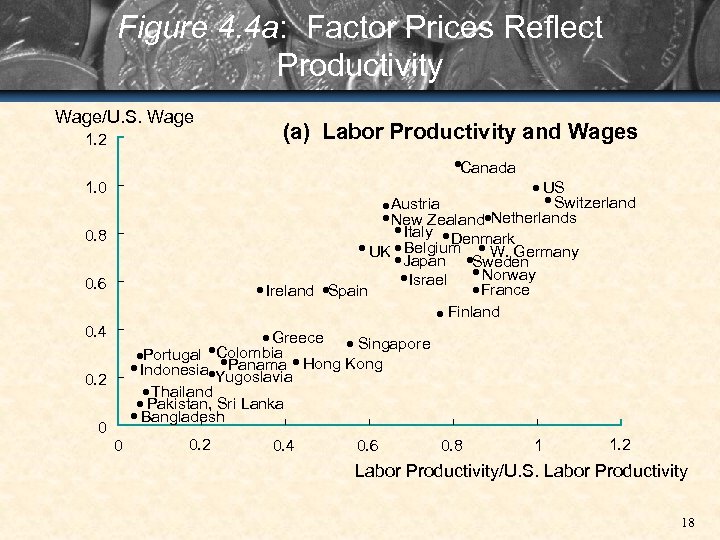

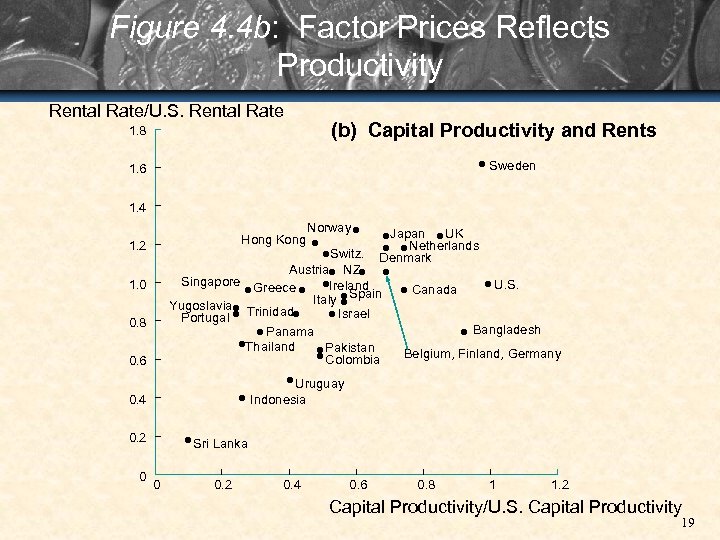

Why Don’t We Observe Factor Price Equalization? • Figure 4. 4 shows that relative factor price differences across countries match relative productivity differences. – Countries with high (low) labor productivity relative to that of the U. S. have high (low) wages relative to the U. S. – Countries with high (low) capital productivity relative to the U. S. have high (low) rental rates. 17

Figure 4. 4 a: Factor Prices Reflect Productivity Wage/U. S. Wage 1. 2 (a) Labor Productivity and Wages Canada 1. 0 US Switzerland Austria New Zealand Netherlands Italy Denmark UK Belgium W. Germany Japan Sweden Norway Israel France Ireland Spain Finland 0. 8 0. 6 0. 4 Greece Singapore Portugal Colombia Panama Indonesia Yugoslavia Hong Kong Thailand Pakistan, Sri Lanka Bangladesh 0. 2 0 0 0. 2 0. 4 0. 6 0. 8 1 1. 2 Labor Productivity/U. S. Labor Productivity 18

Figure 4. 4 b: Factor Prices Reflects Productivity Rental Rate/U. S. Rental Rate 1. 8 (b) Capital Productivity and Rents Sweden 1. 6 1. 4 Hong Kong 1. 2 Japan UK Netherlands Denmark Switz. Austria NZ Singapore Greece Ireland Spain Yugoslavia Trinidad Italy Israel Portugal Panama Thailand Pakistan Colombia 1. 0 0. 8 0. 6 Canada U. S. Bangladesh Belgium, Finland, Germany Uruguay Indonesia 0. 4 0. 2 0 Norway Sri Lanka 0 0. 2 0. 4 0. 6 0. 8 1 1. 2 Capital Productivity/U. S. Capital Productivity 19

Why Don’t We Observe Factor Price Equalization? • Complete output price equalization may not occur due to transportation costs, barriers to trade, and existence of goods that are rarely traded. – The factor price equalization theorem suggests an important policy alternative: • Allow free trade in outputs, specialize in labor-intensive production, and export labor indirectly in the form of labor-intensive goods. – Countries such as Ireland, the Philippines, India, Jamaica, and Singapore have begun using new technologies to do just that. 20

What if Factors Are Immobile in the Short -Run? • Previous assumptions were that factors are completely mobile among industries within a country and completely immobile among countries. – In the short-term, mobility of factors may be imperfect. • Short-run effects of opening trade may differ from longrun effects captured by Stolper-Samuelson and factor price equalization theorems. 21

Reasons for Short-Run Factor Immobility • Physical capital: machines and factories – Most equipment is specialized…it is suited only for the specific purpose for which it was designed. – As physical capital wear out from use and age, firms set aside funds (depreciation allowances) to replace the equipment. • Funds can be used to buy a different type of capital. • Labor capital – same arguments apply. – As older workers retire and new ones enter the labor force, the skill distribution slowly changes in favor of growing industries and away from shrinking ones. 22

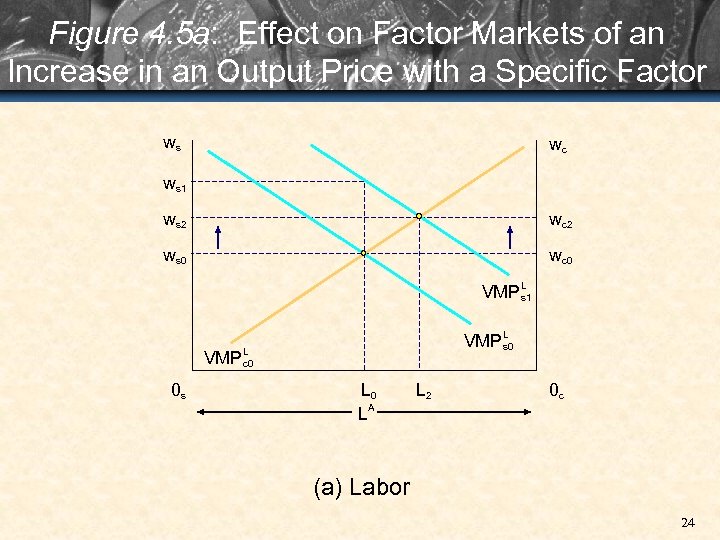

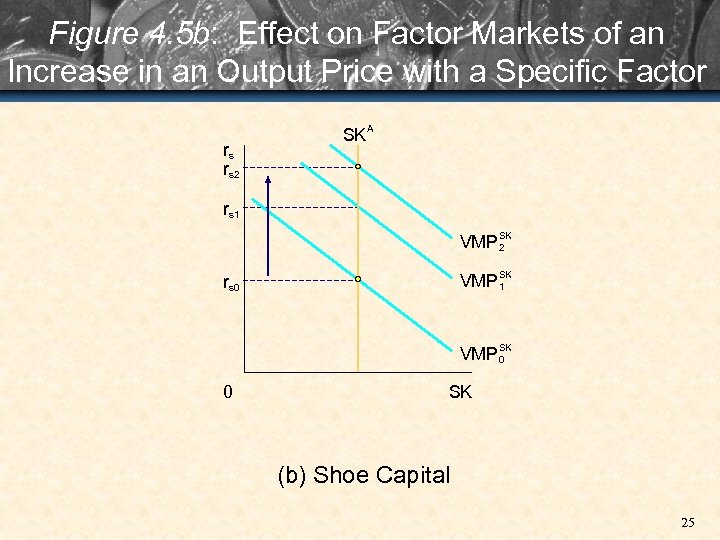

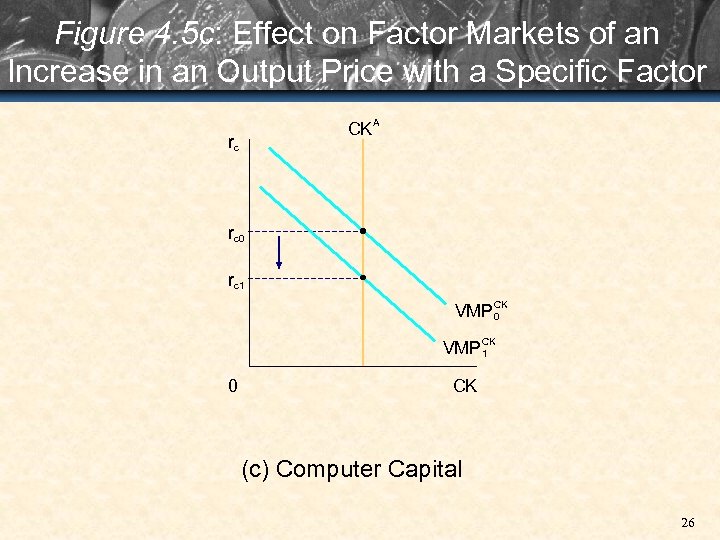

Effects of Short-Run Factor Immobility • Figure 4. 5 illustrates that an increase in the price of shoes raises the wage rate in both the shoe and the computer industries, but by less than the rise in the price of shoes. – The return to capital specific to the shoe industry rises more than proportionally with the price of shoes, and the return to capital specific to the computer industry falls. 23

Figure 4. 5 a: Effect on Factor Markets of an Increase in an Output Price with a Specific Factor ws wc ws 1 ws 2 wc 2 ws 0 wc 0 VMPL s 1 VMPL s 0 VMPL c 0 0 s L 0 LA L 2 0 c (a) Labor 24

Figure 4. 5 b: Effect on Factor Markets of an Increase in an Output Price with a Specific Factor rs rs 2 SKA rs 1 VMPSK 2 VMPSK 1 rs 0 VMPSK 0 0 SK (b) Shoe Capital 25

Figure 4. 5 c: Effect on Factor Markets of an Increase in an Output Price with a Specific Factor CKA rc rc 0 rc 1 VMPCK 0 VMPCK 1 0 CK (c) Computer Capital 26

Effect of a Rise in Shoe Prices on Factor Prices when Capital is Immobile • Wage rates rise in both industries, but by less than the price of shoes. – Effect on workers’ purchasing power depends on shares of shoes and computers in workers’ consumption. • The return to shoe capital rises more than the price of shoes, so owners of shoe capital enjoy an increase in buying power regardless of their pattern of consumption. • Return to computer capital falls, so those owners suffer a loss of purchasing power regardless of their pattern of consumption. 27

Trade with an Industry-Specific Factor • Continue with a case in which labor is highly mobile among industries, but capital is immobile in the short-run. – Country has a comparative disadvantage in laborintensive shoe production and comparative advantage in capital-intensive computer production – it opens trade with another country. • Shoe production falls and computer production rises. • If both labor and capital were mobile between two industries, newly employed workers from shoe industry would flow into computer industry, and computer industry would buy unused capital from shoe industry. 28

Trade with an Industry-Specific Factor • In our example, in the short-run, capital employed in the computer industry and workers who buy more shoes than computers gain from the opening of trade. – And, capital employed in shoe industry and workers who buy more computers than shoes lose. – In the long-run, owners of capital, the factor used intensively in computer production, gain from the opening of trade. • And, workers, the factor used intensively in shoe production, lose. 29

Trade with an Industry-Specific Factor • The existence of factors specific to single industries creates a short-run rigidity, or limitation on the economy’s ability to reallocate production among industries quickly and at a low cost. – The more industry-specific the factors of production, the more costly will be any adjustment to relative price changes in terms of temporary unemployment or underutilization of capital. 30

Trade and Welfare: Gainers, Losers, and Compensation • Opening trade increases the total quantity of goods available and makes it possible for everyone to gain. – In order for everyone to gain, a portion of the gains enjoyed by some would have to be used to compensate others for their losses. • If this were done, society as a whole would be made better off by trade. – In general, however, no automatic mechanism to make this compensatory redistribution exists. 31

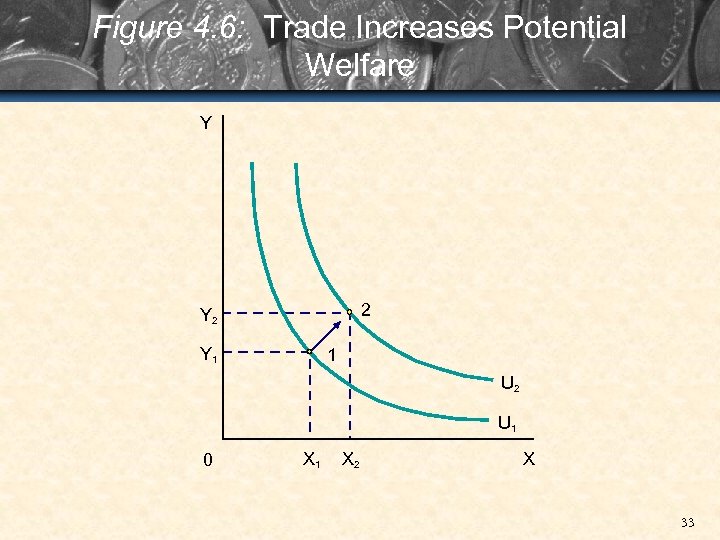

Potential versus Actual Utility • Figure 4. 6 shows that trade allows production of larger quantities of goods, making a higher indifference curve attainable (potentially to make every individual better off – if, for example, the additional goods were distributed among all individuals). 32

Figure 4. 6: Trade Increases Potential Welfare Y 2 Y 1 1 U 2 U 1 0 X 1 X 2 X 33

Comparing Utility: The Pareto Criterion • If, as shown in Fig. 4. 6, after moving from point 1 to point 2, the additional goods were distributed such that every person ended up with more of such a good – Then you could say that this move increased actual welfare or utility according the Pareto Criterion. • States that any change that makes at least one person better off without making any individual worse off increases welfare. 34

Comparing Utility: The Compensation Criterion • Opening trade harms some groups. – How can gainers from a policy gain enough to allow them to compensate the losers for their losses and still enjoy a net gain? • Opening international trade satisfies this Compensation Criterion for welfare improvement. – Because the world economy produces more goods with trade, gainers can, in principle, compensate losers and still be better off. • Such compensation, though possible, rarely occurs. 35

Trade Adjustment Assistance • International trade is dynamic – industries are always making adjustments in order to maintain competitive advantages. – These adjustments cause certain losses. • Temporary unemployment • Relocation • Retraining – U. S. government administers the Trade Adjustment Assistance (TAA) program. • Provides variable compensation for workers displaced for trade-related reasons…see Table 4. 5. 36

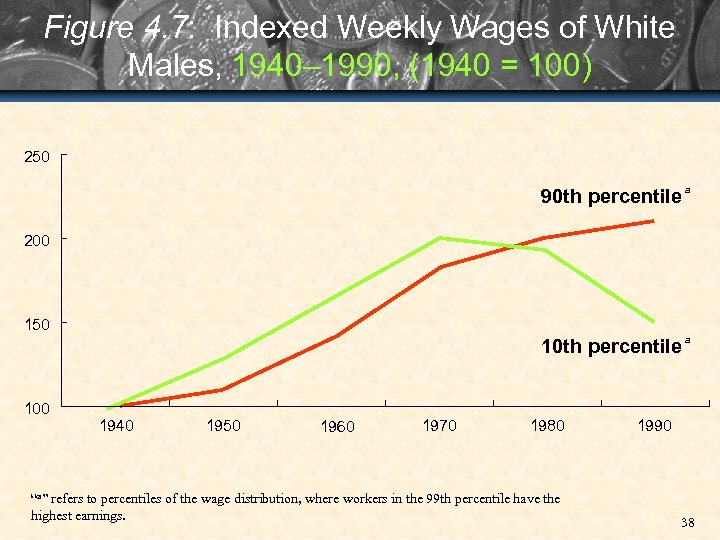

Notes on Case Two: Trade and Wages II: The United States • Figure 4. 7 illustrates that from the mid-1970 s until the present, wages of high-income workers have risen relative to those of lowincome workers. – Trend stems mainly from changes in technology rather than from international trade. • Increased importance of knowledge-intensive skills has increased demand for workers who possess those skills. 37

Figure 4. 7: Indexed Weekly Wages of White Males, 1940– 1990, (1940 = 100) 250 90 th percentile a 200 150 10 th percentile a 100 1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 “a” refers to percentiles of the wage distribution, where workers in the 99 th percentile have the highest earnings. 1990 38

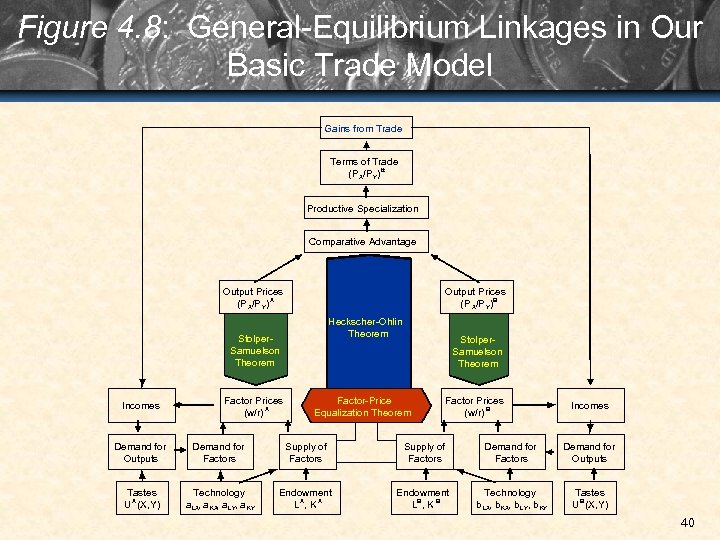

Summary • General equilibrium analysis incorporates the interrelationships among various markets in the world economy. – In Figure 4. 8, the Heckscher-Ohlin, Stolper. Samuelson, and factor price equalization theorems link markets in countries that allow trade in goods. 39

Figure 4. 8: General-Equilibrium Linkages in Our Basic Trade Model Gains from Trade Terms of Trade tt (P X/P Y) Productive Specialization Comparative Advantage Output Prices A (P X/P Y) Output Prices B (P X/P Y) Heckscher-Ohlin Theorem Stolper. Samuelson Theorem Incomes Factor Prices A (w/r) Stolper. Samuelson Theorem Factor-Price Equalization Theorem Factor Prices B (w/r) Incomes Demand for Outputs Demand for Factors Supply of Factors Demand for Outputs Tastes A U (X, Y) Technology a. LX, a KX, a LY, a KY Endowment A A L , K Endowment B B L , K Technology b LX, b KX, b LY, b KY Tastes B U (X, Y) 40

Key Terms in Chapter 4 • General-equilibrium analysis • Partial-equilibrium analysis • Magnification effect • Stolper-Samuelson theorem • Factor price equalization theorem • Depreciation allowance • Pareto criterion 41

Key Terms in Chapter 4 • Compensation criterion • Trade Adjustment Assistance (TAA) 42

243877867114f952c55b16bce9a70b2e.ppt