867e4ba39320a72040a7abf8f0d210ff.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 129

Chapter 8 Capital Budgeting and Cash Flow Analysis Copyright © 2003 South-Western/Thomson Learning

Introduction • This chapter discusses capital budgeting and capital expenditures. • It deals with the financial management of the assets on a firm’s balance sheet.

Capital Budgeting • Capital Budgeting is the process of planning for purchases of assets whose returns are expected to continue beyond one year.

Capital Budgeting • Capital Expenditure – A cash outlay expected to generate a flow of future cash benefits for more than one year. – A normal operating expenditure expected to result in cash benefits during the coming one-year period. (The choice of a one-year period is arbitrary, but it does serve as a useful guideline. )

Capital Budgeting • Capital budgeting decisions can be the most complex decisions facing management. • Several different types of outlays may be classified as capital expenditures and evaluated using the framework of capital budgeting models. (See next several slides. )

Types of Capital Expenditure • The purchase of a new piece of equipment, real estate, or a building in order to expand an existing product or service line or enter a new line of business • The replacement of an existing capital asset, such as drill press • Expenditures for an advertising campaign

Types of Capital Expenditure • Expenditures for a research and development program • Investments in permanent increases of target inventory levels or levels of accounts receivable • Investments in employee education and training

Types of Capital Expenditure • The refunding of an old bond issue with a new, lower-interest issue • Lease-versus-buy analysis • Merger and acquisition evaluation

Capital Expenditure Decisions • Capital expenditures are important to a firm both because they require sizable cash outlays and because they have a long-range impact on the firm’s performance.

Capital Expenditure Decisions • A firm’s capital expenditures affect its future profitability and, when taken together, essentially plot the company’s future direction by determining the following things: – which products will be produced – which markets will be entered – where production facilities will be located – what type of technology will be used

Capital Expenditure Decisions • Capital expenditure decision making is important for another reason as well. Specifically, it is often difficult, if not impossible, to reverse a major capital expenditure without incurring considerable additional expense.

Capital Expenditure Decisions • For example, if a firm acquires highly specialized production facilities and equipment, it must recognize that there may be no ready used-equipment market in which to dispose of them if they do not generate the desired future cash flows.

Capital Expenditure Decisions • For these reasons, a firm’s management should establish a number of definite procedures to follow when analyzing capital expenditure projects. Choosing from among such projects is the objective of capital budgeting models.

Cost of Capital • A firm’s cost of capital is defined as the cost of the funds supplied to it. It is also termed the required rate of return because it specifies the minimum necessary rate of return required by the firm’s investors. In this context, the cost of capital provides the firm with a basis for choosing among various capital investment projects.

How Projects Are Classified • Independent Projects – Acceptance or rejection of one project has no effect on other projects from consideration. – For example, a firm may want to install a new telephone communications system in its headquarters and replace a drill press during approximately the same time. In the absence of a constraint on the availability of funds, both projects could be adopted if they meet minimum investment criteria.

How Projects Are Classified • Mutually Exclusive Projects – Acceptance of one project automatically rejects the others. Because two mutually exclusive projects have the capacity to perform the same function for a firm, only one should be chosen. – For example, BMW was faced with deciding whether it should locate its U. S. manufacturing complex in Spartanburg, S. C. , or at one of several competing North Carolina sites. It ultimately chose the Spartanburg site; this precluded other alternatives.

How Projects Are Classified • Contingent Projects – Acceptance of one project is dependent upon the adoption of one or more other projects. – When a firm is considering contingent projects, it is best to consider together all projects that are dependent on one another and treat them as a single project for purposes of evaluation. – For example, a decision by Nucor to build a new steel plant in North Carolina is contingent upon Nucor investing in suitable air and water pollution control equipment.

Capital Rationing • When a firm has adequate funds to invest in all projects that meet some capital budgeting selection criterion, the firm is said to be operating without a funds constraint.

Capital Rationing • Many times firms limit their capital expenditures, not because of a funds constraint but because of limited managerial resources needed to manage the project effectively. • Frequently, however, the total initial cost of the acceptable projects in the absence of a funds constraint is greater than the total funds the firm has available to invest in capital projects.

Capital Rationing Most companies have a limited amount of dollars available for investment Funds constraint

Basic Framework for Capital Budgeting • According to economic theory, a firm should operate at the point where the marginal cost of an additional unit of output just equals the marginal revenue derived from the output. Following this rule leads to profit maximization.

Basic Framework for Capital Budgeting • A firm’s marginal revenue is the rate of return earned on succeeding investments. • A firm’s marginal cost may be defined as the firm’s marginal cost of capital (MCC), that is, the cost of successive increments of capital acquired by the firm.

Basic Framework for Capital Budgeting • Figure 8. 1 illustrates a simplified capital budgeting model. This model assumes that all projects have the same risk. The projects under consideration are indicated by lettered bars on the graph.

Basic Framework for Capital Budgeting • Project A requires an investment of $2 million and is expected to generate a 24 percent rate of return. • Project B will cost $1 million ($3 million minus $2 million on the horizontal axis) and is expected to generate a 22 percent rate of return, and so on.

Basic Framework for Capital Budgeting • The projects are arranged in descending order according to their expected rates of return, in recognition of the fact that no firm has an inexhaustible supply of projects offering high expected rates of return. This schedule of projects is often called the firm’s investment opportunity curve (IOC).

Basic Framework for Capital Budgeting • Typically, a firm will invest in its best projects first—such as Project A—before moving on to less attractive alternatives.

Basic Framework for Capital Budgeting • The MCC schedule represents the marginal cost of capital to the firm.

Basic Framework for Capital Budgeting • Note that the schedule increases as more funds are sought in the capital markets. The reasons for this including the following: – Investors’ expectations about the firm’s ability to successfully undertake a large number of new projects – The business risk to which the firm is exposed because of its particular line of business

Basic Framework for Capital Budgeting – The firm’s financial risk, which is due to its capital structure – The supply and demand for investment capital in the capital market – The cost of selling new stock, which is greater than the cost of retained earnings

Basic Framework for Capital Budgeting • The basic capital budgeting model indicates that, in principle, the firm should undertake Projects A, B, C, D, and E, because the expected returns from each project exceed the firm’s marginal cost of capital.

Basic Framework for Capital Budgeting • Unfortunately, however, in practice, financial decision making is not this simple. Some practical problems are encountered in trying to apply this model, including the following (the following four slides):

Basic Framework for Capital Budgeting • At any point in time, a firm probably will not know all of the capital projects available to it. In most firms, capital expenditures are proposed continually, based on results of research and development programs, changing market conditions, new technologies, corporate planning efforts, and so on.

Basic Framework for Capital Budgeting • Thus, a schedule of projects similar to Figure 8. 1 will be probably be incomplete at the time the firm makes its capital expenditure decisions.

Basic Framework for Capital Budgeting • The shape of the MCC schedule itself may be difficult to determine. (The problems and techniques involved in estimating a firm’s cost of capital are discussed in Chapter 11. )

Basic Framework for Capital Budgeting • In most cases, a firm can only make uncertain estimates of a project’s future costs and revenues (and, consequently, its rate of return). Some projects will be more risky than others. The riskier a project is, the greater the rate of return that is required before it will be acceptable. (This concept is considered in more detail in Chapter 10. )

Basic Framework for Capital Budgeting: Summary • Invest in the most profitable projects first. • Continue accepting projects as long as the rate of return exceeds the MCC. • Expand output until marginal revenue equals marginal cost.

Capital Budgeting Process • Step 1 – Generating capital investment project proposals • Step 2 – Estimating cash flows

Capital Budgeting Process • Step 3 Ch 9 – Evaluating alternatives and selecting projects to be implemented • Step 4 Ch 9 – Reviewing a project’s performance after it has been implemented, and post-auditing its performance after its termination

Classify Investment Projects • Growth opportunities • Cost reduction opportunities • Required to meet legal requirements • Required to meet health & safety standards

Classify Investment Projects • Projects Generated by Growth Opportunities: – Assume that a firm produces a particular product that is expected to experience increased demand during the upcoming years. If the firm’s existing facilities are inadequate to handle the demand, proposals should be developed for expanding the firm’s capacity.

Classify Investment Projects – These proposals may come from the corporate planning staff group, from a divisional staff group, or from some other sources.

Classify Investment Projects – Because most existing products eventually become obsolete, a firm’s growth is also dependent on the development and marketing of new products. This involves the generation of research and development investment proposals, marketing research investments, test marketing investments, and perhaps even investments in new plants, property, and equipment.

Classify Investment Projects • Projects Generated by Cost Reduction Opportunities: – Just as products become obsolete over time, so do plants, property, equipment, and production processes. Normal use makes older plants more expensive to operate because of the higher cost of maintenance and downtime (idle time).

Classify Investment Projects – In addition, new technological developments may render existing equipment economically obsolete. These factors create opportunities for cost reduction investments, which include replacing old, obsolete capital equipment with newer, more efficient equipment.

Classify Investment Projects • Projects Generated to Meet Legal Requirements and Health and Safety Standards: – These projects include investment proposals for such things as pollution control, ventilation, and fire protection equipment. In terms of analysis, this group of projects is best considered as contingent upon other projects.

Classify Investment Projects – To illustrate, suppose USX wishes to build a new steel plant in Cleveland, Ohio. The decision will be contingent upon the investment in the amount of pollution abatement equipment required by state and local laws. Thus, the decision to invest in the new plant must be based upon the total cost of the plant, including the pollution abatement equipment, and not just the operating equipment alone. In the case of existing facilities, this type of decision making is sometimes more complex.

Classify Investment Projects – For example, suppose a firm is told it must install new pollution abatement equipment in a plant that has been in operation for some time. The firm first needs to determine the lowest cost alternative that will meet these legal requirements. “Lowest cost” is normally measured by the smallest present value of net cash outflows from the project. Then management must decide whether the remaining stream of cash flows from the plant is sufficient to justify the expenditure. If it appears as though it will not be, the firm may consider building a new facility, or it may decide simply to close down the original plant.

Principles of Estimating CFs • The capital budgeting process is concerned primarily with the estimation of the cash flows associated with a projects, not just the project’s contribution to accounting profits.

Principles of Estimating CFs • Typically, a capital expenditure requires an initial cash outflow, termed the net investment. Thus it is important to measure a project’s performance in terms of the net (operating) cash flows it is expected to generate over a number of future years.

Principles of Estimating CFs • The project expected to generate a stream of net cash inflows over its anticipated life is called a normal or conventional project.

Principles of Estimating CFs • Nonnormal or nonconventional projects have cash flow patterns with either more than one or no sign change. The latter refers to the project which is expected to generated a stream of net cash outflows over its anticipated life.

Principles of Estimating CFs • Cash flows should be measured on an incremental basis. In other words, the cash flow stream for a particular project should be estimated from the perspective of how the entire cash flow stream of the firm will be affected if the project is adopted as compared with how the stream will be affected if the project is not adopted. This principle is particularly important in estimating CFs of asset replacement projects.

Principles of Estimating CFs • Cash flows should be measured on an after-tax basis. Because the initial investment made on a project requires the outlay of after-tax cash dollars, the returns from the project should be measured in the same units, namely, after-tax cash flows.

Principles of Estimating CFs • All the indirect effects of a project should be included in the cash flow calculations. For example, if a proposed plant expansion requires that working capital be increased for the firm as a whole, the increase in working capital should be included in the net investment required for the project.

Principles of Estimating CFs • Sunk costs should not be considered when evaluating a project. A sunk cost is an outlay that has already been made (or committed to be made). Because sunk costs cannot be recovered, they should not be considered in the decision to accept or reject a project.

Principles of Estimating CFs • For example, in 2001, the Chemtron Corporation was considering constructing a new chemical disposal facility. Two years earlier, the firm had hired the R. O. E. Consulting Group to do an environmental impact analysis of the proposed site at a cost of $500, 000.

Principles of Estimating CFs Because this $500, 000 cost cannot be recovered whether the project is undertaken or not, it should not be considered in the accept-reject analysis taking place in 2001. The only relevant costs are the incremental outlays that will be made from this point forward if the project is undertaken.

Principles of Estimating CFs • The value of resources used in a project should be measured in terms of their opportunity costs. Opportunity costs of resources (assets) are the cash flows those resources could generate if they are not used in the project under consideration.

Principles of Estimating CFs: Summary • On an incremental basis • On an after-tax basis • Include indirect effects • Exclude sunk costs • Opportunity costs of resources

Cash Flow Information • American Cash Flow Institute – http: //acfi-online. com/ • American Cash Flow Association – http: //acfa-cashflow. com/

Estimating the NINV • The net investment (NINV) in a project is defined as the project’s initial net cash outlay, that is, the outlay at time (period) 0. It is calculated using the following steps: Step 1. The new project cost plus any installation and shipping costs associated with acquiring the asset and putting it into service PLUS

Estimating the NINV Step 2. Any increase in net working capital initially required as a result of the new investment MINUS Step 3. The net proceeds from the sale of existing assets when the investment is a replacement decision PLUS or MINUS

Estimating the NINV Step 4. The taxes associated with the sale of the existing assets and/or the purchase of the new assets EQUALS The net investment (NINV)

Estimating the NINV • Note that the tax consequences can influence the net investment of a project. These tax effects are the treatment of gains and losses from asset sales in the case of replacement decisions.

Estimating the NINV • If a project generates additional revenues and the company extends credit to its customers, an additional initial investment in accounts receivable is required. • Moreover, if additional inventories are necessary to generate the increased revenues, then an additional initial investment in inventory is required, too.

Estimating the NINV • This increase in initial working capital– that is, cash, accounts receivable, and inventories—should be calculated net of any automatic increases in current liabilities, such as accounts payable or wages and taxes payable, that occur because of the project.

Estimating the NINV • Working capital compares current assets to current liabilities, and serves as the liquid reserve available to satisfy contingencies and uncertainties. • Working capital = current assets – current liabilities

Estimating the NINV • As a general rule, replacement projects require little or no net working capital increase. • Expansion projects, on the other hand, normally require investments in additional net working capital.

NINV for a Multiple-period Investment • Some projects require outlays over more than one year before positive cash inflows are generated. • The NINV for a multiple-period investment is the PV of the series of outlays discounted at the firm’s cost of capital.

NINV for a Multiple-period Investment • For example, consider a project requiring outlays of $100, 000 in year 0, $30, 000 in year 1, and $20, 000 in year 2, with a cost of capital equal to 10 percent. The NINV or present value of the cash outlays is calculated as follows: NINV = $100, 000(PVIF 0. 10, 0) + $30, 000 (PVIF 0. 10, 1) + $20, 000 (PVIF 0. 10, 2) = $143, 790 • Figure 8. 3 illustrates this concept.

Computing Net Cash Flows (NCF) • Capital investment projects are expected to generate after-tax cash flow streams after the initial net investment has been made. The process of estimating incremental cash flows associated with a specific project is an important part of the capital budgeting process.

Computing Net Cash Flows (NCF) • Capital budgeting is concerned primarily with the after-tax net (operating) cash flows (NCF) of a particular project, or change in cash inflows minus change in cash outflows.

Computing Net Cash Flows (NCF) • For any year during the life of a project, net cash flows may be defined as the change in operating earnings after taxes, ΔOEAT, plus the change in depreciation, ΔDep, minus the change in the net working capital investment required by the firm to support the project, ΔNWC: NCF = ΔOEAT + ΔDep – ΔNWC where the term change (Δ) refers to the difference in cash (and noncash) flows with and without adoption of the investment project.

Computing Net Cash Flows (NCF) • Depreciation is the systematic allocation of the cost of an asset with an economic life in excess of one year. Although depreciation is not a cash flow, it does affect a firm’s after-tax cash flows by reducing reported earnings and thereby reducing taxes paid by a firm.

Computing Net Cash Flows (NCF) • If a firm’s depreciation increases in a particular year as a result of adopting a project, after-tax net cash flow in that year will increase, all other things being equal.

Computing Net Cash Flows (NCF) • After-tax net cash flow also considers changes in a firm’s investment in net working capital. Changes in net working capital can occur as part of the net investment at time 0 or at any time during the life of the project.

Computing Net Cash Flows (NCF) • If a firm increases its accounts receivable, for example, in a particular year without increasing its current liabilities as a result of adopting a specific project, after-tax net cash flow in that year will decrease, all other things being equal.

Computing Net Cash Flows (NCF) • On the other hand, a reduction in a firm’s investment in net working capital during a given year results in an increase in the firm’s net cash flow for that year.

Computing Net Cash Flows (NCF) • From basic accounting definitions, the change in operating earnings after taxes (ΔOEAT) is equal to the change in operating earnings before taxes (ΔOEBT) times (I – T) where T is the marginal corporate income tax rate. • That is, ΔOEAT = (ΔOEBT)(I – T).

Computing Net Cash Flows (NCF) • Furthermore, ΔOEBT is equal to the change in revenues (ΔR) minus the change in operating cost (ΔO) minus the change in depreciation (ΔDep). • That is, ΔOEBT = ΔR – ΔO – ΔDep. • ΔOEAT = (ΔOEBT)(I – T) = (ΔR – ΔO – ΔDep)(I – T)

Computing Net Cash Flows (NCF) • Then the definition of net cash flow can also be expressed as follows: NCF = [(Rw – Rwo) – (Ow – Owo) – (Depw – Depwo)](1 – T) + (Depw – Depwo) – ΔNWC Rw (Rwo) = Revenues of the firm with (without) the project Ow (Owo) = Operating costs exclusive of depreciation for the firm with (without) the project Depw (Depwo) = Depreciation charges for the firm with (without) the project

Computing Net Cash Flows (NCF) • The definition of net cash flow can be further simplified as follows: NCF = (ΔR – ΔO – ΔDep)(1 – T) + ΔDep – ΔNWC where the term change (Δ) refers to the difference in cash (and noncash) flows with and without adoption of the investment project.

Recovery of After-Tax Salvage Value • When an asset that has been depreciated is sold, there are potential tax consequences that may affect the after-tax net proceeds received from the asset sale. These tax consequences are important when estimating the after-tax salvage value to be received at the end of the economic life of any project. There are four cases that need to be considered.

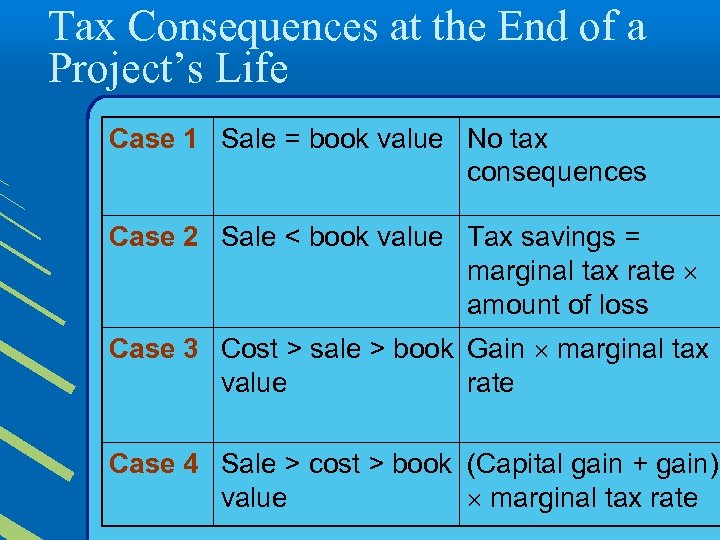

Tax Consequences at the End of a Project’s Life Case 1 Sale = book value No tax consequences Case 2 Sale < book value Tax savings = marginal tax rate amount of loss Case 3 Cost > sale > book Gain marginal tax value rate Case 4 Sale > cost > book (Capital gain + gain) value marginal tax rate

Sale of an Asset for Its Book Value : Case 1 • If a company disposes of an asset for an amount exactly equal to the asset’s tax book value, there is neither a gain nor a loss on the sale and thus there are not tax consequence.

Sale of an Asset for Its Book Value : Case 1 • For example, if Apex Corp. sells for $50, 000 an asset with a book value for tax purposes of $50, 000, no taxes are associated with this disposal. – In general, the tax book value of an asset equals the installed cost of the asset less accumulated tax depreciation.

Sale of an Asset for Less Than Its Book Value : Case 2 • If Apex Corp. sells for $20, 000 an asset having a tax book value of $50, 000, Apex Corp. incurs a $30, 000 pretax loss. Assuming that this asset is used in business or trade (an essential criterion for this tax treatment), this loss may be treated as an operating loss or an offset to operating income. This operating loss effectively reduces the company’s taxes by an amount equal to the loss times the company’s marginal tax rate.

Sale of an Asset for Less Than Its Book Value : Case 2 Assume that the company’s earnings before taxes is $100, 000 (before consideration of the operating loss from the disposal of the asset). Taxes on these earnings are $100, 000 times the company’s marginal (40 percent) tax rate, or $40, 000.

Sale of an Asset for Less Than Its Book Value : Case 2 Because of the operating loss incurred by selling the asset for $20, 000, the company’s taxable income is reduced to $70, 000 (= $100, 000 – $30, 000) and the taxes decline to $28, 000 (40 percent of $70, 000). The $12, 000 (= $40, 000 – $28, 000) difference in taxes is equal to the tax loss on the sale of the old asset times the company’s marginal tax rate ($30, 000 40%).

Sale of an Asset for More Than Its Book Value : Case 3 • If Apex Corp. sells the asset for $60, 000 —$10, 000 more than the current tax book value—$50, 000 of this amount constitutes a tax-free cash inflow, and the remaining $10, 000 is taxed as operating income. As a result, the firm’s taxes increase by $4, 000, or the amount of the gain times the firm’s marginal tax rate ($10, 000 40%).

Sale of an Asset for More Than Its Original Cost : Case 4 • If Apex Corp. sells the asset for $120, 000 (assuming an original asset cost of $110, 000), part of the gain from the sale is treated as ordinary income and part is treated as a long-term capital gain.

Sale of an Asset for More Than Its Original Cost : Case The gain receiving ordinary income treatment is equal to the difference between the original asset cost and the current tax book value, or $60, 000 (= $110, 000 – $50, 000). The capital gain portion is the amount in excess of the original asset cost, or $10, 000.

Sale of an Asset for More Than Its Original Cost : Case 4 • In the case of sale of an asset more than its original cost: – Capital gain = sale – cost – Gain = cost – book value

Recovery of Net Working Capital • In the last year of a project that, over its economic life, has required incremental net working capital investments, this net working capital is assumed to be liquidated and returned to the firm as cash. At the end of a project’s life, all net working capital additions required over the project’s life are recovered—not just the initial net working capital outlay occurring at time 0.

Recovery of Net Working Capital • Hence, the total accumulated net working capital is normally recovered in the last year of the project. This decrease in net working capital in the last year of the project increases the net cash flow for that year, all other things being equal. Of course, no tax consequences are associated with the recovery of NWC.

Interest Charges and Net Cash Flows • Often the purchase of a particular asset is tied closely to the creation of some debt obligation, such as the sale of mortgage bonds or a bank loan. Nevertheless, it is generally considered incorrect to deduct the interest charges associated with a particular project from the estimated cash flows. This is true for two reasons as mentioned below.

Interest Charges and Net Cash Flows • First, the decision about how a firm should be financed can—and should— be made independently of the decision to accept or reject one or more projects. Instead, the firm should seek some combination of debt, common stock, and preferred stock capital that is consistent with management’s wishes concerning the trade-off between financial risk and the cost of capital.

Interest Charges and Net Cash Flows In many cases, this will result in a capital structure with the cost of capital at or near its minimum. Because investment and financing decisions should normally be made independently of one another, each new project can be viewed as being financed with the same proportions of the various sources of capital funds used to finance the firm as a whole.

Interest Charges and Net Cash Flows • Second, when a discounting framework is used for project evaluation, the discount rate, or cost of capital, already incorporates the cost of funds used to finance a project. Thus, including interest charges in cash flow calculations essentially would result in a double counting of costs.

Depreciation • Depreciation was defined as the systematic allocation of the cost of an asset over more than one year. It allows a firm to spread the costs of fixed assets over a period of years to better match costs and revenues in each accounting period.

Depreciation • The annual depreciation expense recorded for a particular asset is simply an allocation of historic costs and does not necessarily indicate a declining market value. • For example, a company that is depreciating an office building may find the building’s market value appreciating each year.

Depreciation • Under the straight-line depreciation method, the annual amount of an asset’s depreciation is calculated as follows: Annual depreciation amount = (installed cost) (number of years over which the asset is depreciated) – The installed cost includes the purchase price of the asset plus shipping and installation charges, that is, Step 1 of the NINV calculation described earlier.

Depreciation • For tax purposes, the depreciation rate a firm uses has a significant impact on the cash flows of the firm. This is so because depreciation represents a noncash expense that is deductible for tax purposes.

Depreciation • Hence, the greater the amount of depreciation charged in a period, the lower the firm’s taxable income will be. With a lower reported taxable income, the firm’s tax obligation (a cash outflow) is reduced and the cash inflows for the firm are increased.

Asset Expansion Projects • A project that requires a firm to invest funds in additional assets in order to increase sales (or reduce costs) is called an asset expansion project.

Example: Asset Expansion Projects • For example, suppose the TLC Yogurt Company has decided to capitalize on the exercise fad and plans to open an exercise facility in conjunction with its main yogurt and health foods store. To get the project under way, the company will rent additional space adjacent to its current store.

Example: Asset Expansion Projects The equipment required for the facility will cost $50, 000. Shipping and installation charges for the equipment are expected to total $5, 000. This equipment will be depreciated on a straight-line basis over its five-year economic life to an estimated salvage value of $0.

Example: Asset Expansion Projects In order to open the exercise facility, TLC estimates that it will have to add about $7, 000 initially to its net working capital in the form of additional inventories of exercise supplies, cash, and accounts receivable for its exercise customers (less accounts payable).

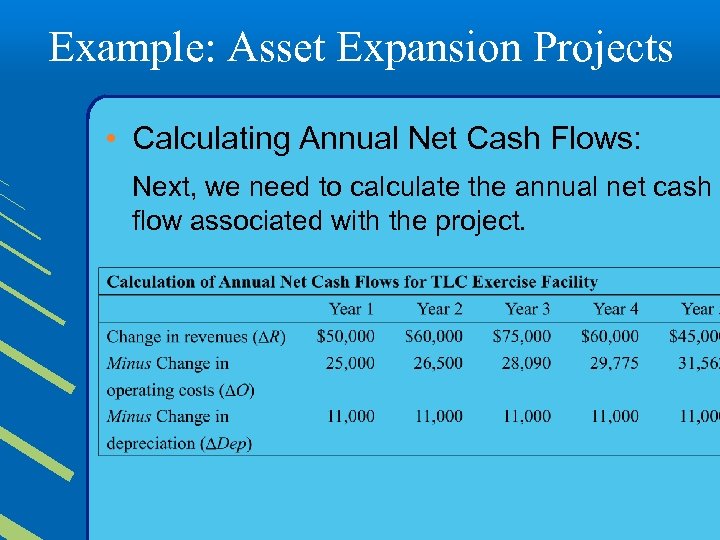

Example: Asset Expansion Projects During the first year of operations, TLC expects its total revenues (from yogurt sales and exercise services) to increase by $50, 000 above the level that would have prevailed without the exercise facility addition. These incremental revenues are expected to grow to $60, 000 in year 2, $75, 000 in year 3, decline to $60, 000 in year 4, and decline again to $45, 000 during the fifth year of the project’s life.

Example: Asset Expansion Projects The company’s incremental operating costs associated with the exercise facility, including the rental of the facility, are expected to total $25, 000 during the first year and increase at a rate of 6 percent per year over the five-year project life. Depreciation will be $11, 000 per year in which $11, 000 is derived from [($50, 000 + $5, 000)/5] assuming no salvage value.

Example: Asset Expansion Projects TLC has a marginal tax rate of 40 percent. In addition, TLC expects that it will have to add about $5, 000 per year to its net working capital in years 1, 2, and 3 and nothing in years 4 and 5. At the end of the project, the total accumulated net working capital required by the project will be recovered.

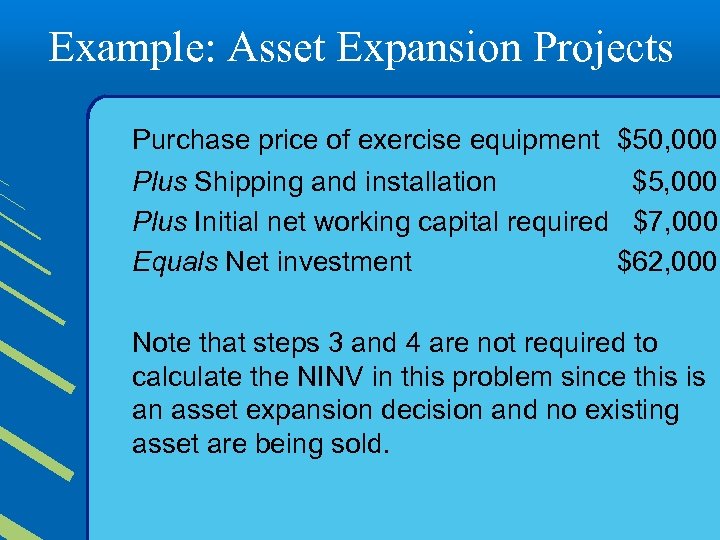

Example: Asset Expansion Projects • Calculating the Net Investment: First, we determine the net investment required for the exercise facility expansion. TLC must make a cash outlay of $50, 000 to pay for the facility equipment. In addition, it must pay $5, 000 in cash to cover the costs of shipping and installation of the equipment. Finally, TLC must invest $7, 000 in initial net working capital to get the project under way. The four-step procedure discussed earlier for calculating the net investment yields the NINV required at time 0:

Example: Asset Expansion Projects Purchase price of exercise equipment $50, 000 Plus Shipping and installation $5, 000 Plus Initial net working capital required $7, 000 Equals Net investment $62, 000 Note that steps 3 and 4 are not required to calculate the NINV in this problem since this is an asset expansion decision and no existing asset are being sold.

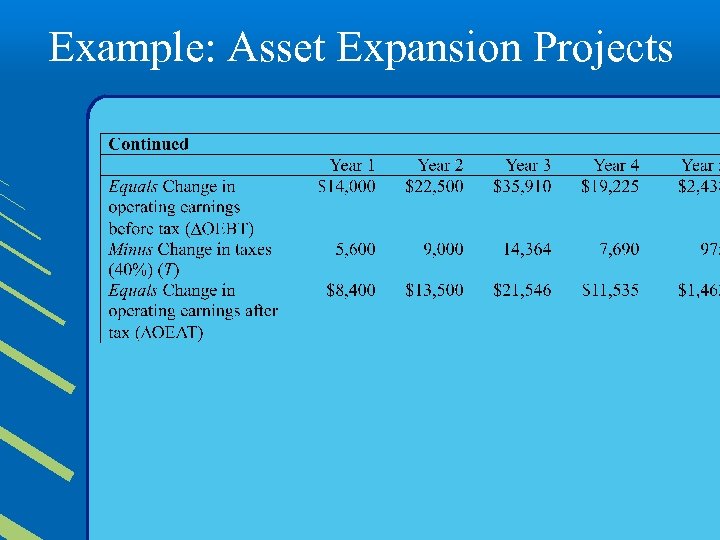

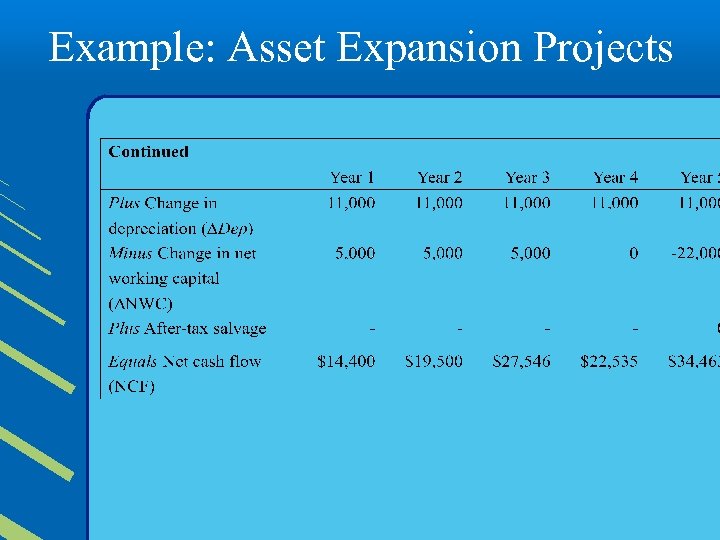

Example: Asset Expansion Projects • Calculating Annual Net Cash Flows: Next, we need to calculate the annual net cash flow associated with the project.

Example: Asset Expansion Projects

Example: Asset Expansion Projects

Asset Replacement Projects • Asset replacement involve retiring one asset and replacing it with a more efficient asset.

Example: Asset Replacement Projects • For example, suppose Briggs & Stratton purchased an automated drill press 10 years ago that had an estimated economic life of 20 years. The drill press originally cost $150, 000 and has been fully depreciated, leaving a current book value of $0. The actual market value of this drill press is $40, 000.

Example: Asset Replacement Projects The company is considering replacing the drill press with a new one costing $190, 000. Shipping and installation charges will add an additional $10, 000 to the cost. The new machine would be depreciated to zero on a straight-line basis.

Example: Asset Replacement Projects The new machine is expected to have a 10 -year economic life, and its actual salvage value at the end of the 10 -year period is estimated to be $25, 000. Briggs & Stratton’s current marginal tax rate is 40 percent.

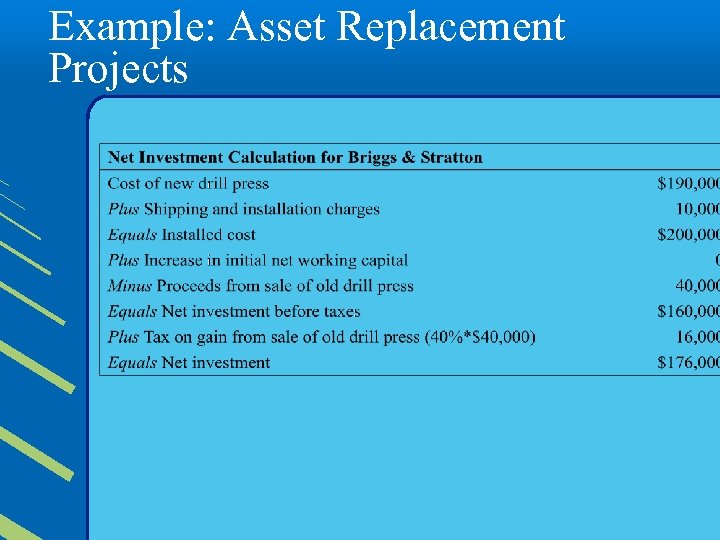

Example: Asset Replacement Projects • Calculating the Net Investment: – Steps 1 and 2 of the net investment calculation are easy; the new project cost ($190, 000) plus shipping and installation ($10, 000) is $200, 000. In this case, no initial incremental net working capital is required. – In steps 3 and 4, the net proceeds received from the sale of the old drill press have to be adjusted for taxes. Because the old drill press is sold for $40, 000, the gain from this sale is treated as a recapture of depreciation and thus taxed as ordinary income.

Example: Asset Replacement Projects

Example: Asset Replacement Projects • Calculating Annual Net Cash Flows: – Suppose Briggs & Stratton expects annual revenues during the project’s first year to increase from $70, 000 to $85, 000 if the new drill press is purchased. After the first year, revenues from the new project are expected to increase at a rate of $2, 000 a year for the remainder of the project life.

Example: Asset Replacement Projects – Assume further that while the old drill press required two operators, the new drill press is more automated and needs only one, thereby reducing annual operating costs from $40, 000 to $20, 000 during the project’s first year. After the first year, annual operating costs of the new drill press are expected to increase by $1, 000 a year over the remaining life of the project. The old machine is fully depreciated, whereas the new machine will be depreciated on a straight-line basis.

Example: Asset Replacement Projects – The marginal tax rate of 40 percent applies. Assume also that the company’s net working capital does not change as a result of replacing the drill press.

Example: Asset Replacement Projects • The first-year net cash flow resulting from the purchase of the new drill press can be computed by substituting Rw = $85, 000, Rwo =$70, 000, Ow = $20, 000, Owo = $40, 000, Depw = $20, 000 (= $200, 000/10), Depwo = $0, T = 0. 40, and ΔNWC = $0 into the equation as follows: – NCF 1 = [($85, 000 – $70, 000) – ($20, 000 – $40, 000) – ($20, 000 – $0)](1 – 0. 4) + ($20, 000 – $0) – $0 = $29, 000

Example: Asset Replacement Projects • Using the different expected values for new revenues Rw = $87, 000 and new operating costs Ow = $21, 000 in the second year, the second-year net cash flows can be computed as follows: – NCF 2 = [($87, 000 – $70, 000) – ($21, 000 – $40, 000) – ($20, 000 – $0)](1 – 0. 4) + ($20, 000 – $0) – $0 = $29, 600 – Similar calculations are used to obtain the net cash flows in years 3 through 9.

Example: Asset Replacement Projects • Finally, in year 10, the $25, 000 estimated salvage from the new drill press must be added along with its associated tax effects. This $25, 000 salvage is treated as ordinary income because it represents a recapture of depreciation for tax purposes. – NCF 10 = [($103, 000 – $70, 000) – ($29, 000 – $40, 000) – ($20, 000 – $0)](1 – 0. 4) + ($20, 000 – $0) – $0 + $25, 000 salvage value – tax on salvage value (0. 4*$25, 000) = $34, 400 + $25, 000 – $10, 000 = $49, 400

Ethical Issues: Biased CF Estimates • Overestimate the revenues • Underestimate the costs • Reduce CF estimates to a level below the “most likely outcome”

867e4ba39320a72040a7abf8f0d210ff.ppt