766f6b81b766d9f760da73cdef1012d5.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 24

(Chapter 7 continued) We now offer a &get_long_id toolkit function which automatically polices the state file cache, deleting old state files. • The idea is that a request for a new session ID should be contingent upon whether the cache has reached some preset limit, the cache limit, on the number of state files it can contain. • If the cache is "full" (cache limit reached) it is policed before a new session ID is given out. • The cache is policed by deleting those state files which have not been modified (i. e. used by an active session) in some preset time limit -- the file life span.

(Chapter 7 continued) We now offer a &get_long_id toolkit function which automatically polices the state file cache, deleting old state files. • The idea is that a request for a new session ID should be contingent upon whether the cache has reached some preset limit, the cache limit, on the number of state files it can contain. • If the cache is "full" (cache limit reached) it is policed before a new session ID is given out. • The cache is policed by deleting those state files which have not been modified (i. e. used by an active session) in some preset time limit -- the file life span.

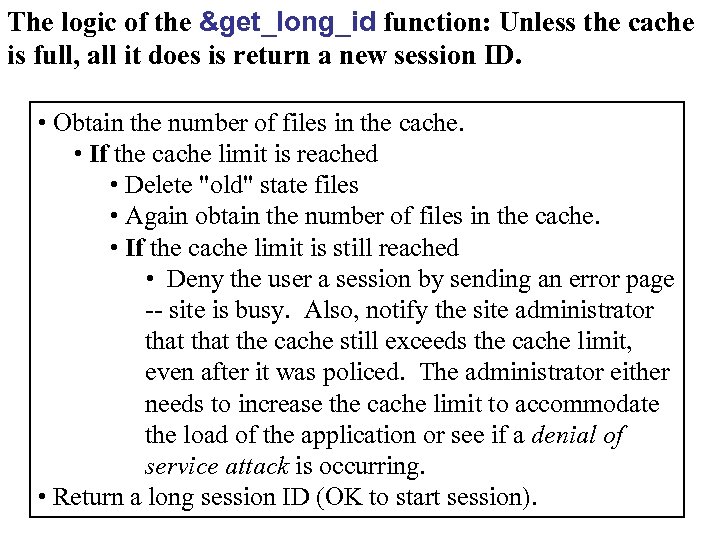

The logic of the &get_long_id function: Unless the cache is full, all it does is return a new session ID. • Obtain the number of files in the cache. • If the cache limit is reached • Delete "old" state files • Again obtain the number of files in the cache. • If the cache limit is still reached • Deny the user a session by sending an error page -- site is busy. Also, notify the site administrator that the cache still exceeds the cache limit, even after it was policed. The administrator either needs to increase the cache limit to accommodate the load of the application or see if a denial of service attack is occurring. • Return a long session ID (OK to start session).

The logic of the &get_long_id function: Unless the cache is full, all it does is return a new session ID. • Obtain the number of files in the cache. • If the cache limit is reached • Delete "old" state files • Again obtain the number of files in the cache. • If the cache limit is still reached • Deny the user a session by sending an error page -- site is busy. Also, notify the site administrator that the cache still exceeds the cache limit, even after it was policed. The administrator either needs to increase the cache limit to accommodate the load of the application or see if a denial of service attack is occurring. • Return a long session ID (OK to start session).

• Perl's directory functions are used to read in the names (as strings) of all the state files found in the cache. Example: opendir(D, "path/to/cache/directory/"); @allfiles = readdir(D); closedir(D); • We can then easily determine the size of the cache $#allfiles. • Moreover, the files in the cache can be individually examined by looping over the @allfiles array.

• Perl's directory functions are used to read in the names (as strings) of all the state files found in the cache. Example: opendir(D, "path/to/cache/directory/"); @allfiles = readdir(D); closedir(D); • We can then easily determine the size of the cache $#allfiles. • Moreover, the files in the cache can be individually examined by looping over the @allfiles array.

• The function also makes use of two of Perl's file test operators. (Such operators are discussed in more detail in Section 12. 6. ) • To test the "age" of state files: -M filename returns the time (in days as a real number) since the file was last modified • To make sure that we have is actually a state file: (there could be other directories in the cache, like the hidden ones used by the Unix and Linux file systems. ) -f filename returns false (0) if it is not a file true (1) if it is See source code for the &get_long_id function in Chap 7 CGI. lib.

• The function also makes use of two of Perl's file test operators. (Such operators are discussed in more detail in Section 12. 6. ) • To test the "age" of state files: -M filename returns the time (in days as a real number) since the file was last modified • To make sure that we have is actually a state file: (there could be other directories in the cache, like the hidden ones used by the Unix and Linux file systems. ) -f filename returns false (0) if it is not a file true (1) if it is See source code for the &get_long_id function in Chap 7 CGI. lib.

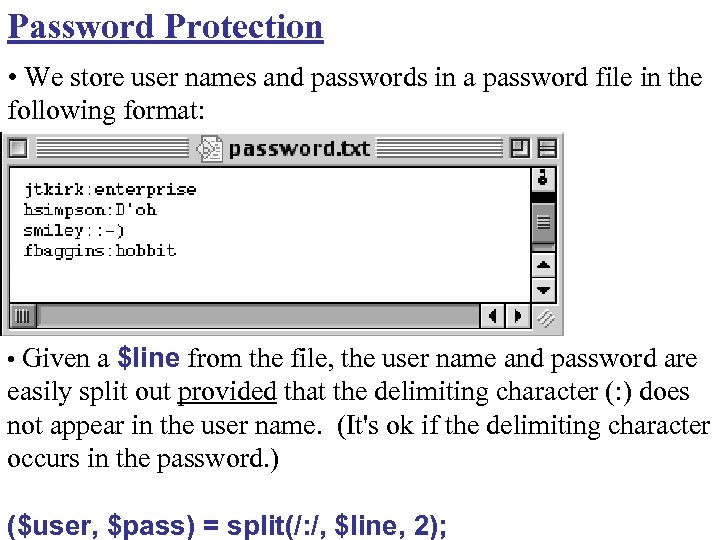

Password Protection • We store user names and passwords in a password file in the following format: • Given a $line from the file, the user name and password are easily split out provided that the delimiting character (: ) does not appear in the user name. (It's ok if the delimiting character occurs in the password. ) ($user, $pass) = split(/: /, $line, 2);

Password Protection • We store user names and passwords in a password file in the following format: • Given a $line from the file, the user name and password are easily split out provided that the delimiting character (: ) does not appear in the user name. (It's ok if the delimiting character occurs in the password. ) ($user, $pass) = split(/: /, $line, 2);

• Password verification is so common a need in Web applications, we provide a new toolkit function, &logon, to automate the process. Example use: $result = &logon("pw. txt", "user", "pass"); • If user: pass is found on a line in the password file, the function returns the string "yes". • Otherwise, it returns a descriptive failure message, "invalid user" for example. (That's why the function doesn't simply return a Boolean value. ) See Chap 7 CGI. lib for source code.

• Password verification is so common a need in Web applications, we provide a new toolkit function, &logon, to automate the process. Example use: $result = &logon("pw. txt", "user", "pass"); • If user: pass is found on a line in the password file, the function returns the string "yes". • Otherwise, it returns a descriptive failure message, "invalid user" for example. (That's why the function doesn't simply return a Boolean value. ) See Chap 7 CGI. lib for source code.

• Usually, a Web application has publicly accessible pages and others which are password protected (private). • The different pages generated by a Web application are determined by which functions are in its app logic. • Thus, a private page is one for which the app logic function first verifies password information before returning the page. • That means, the notion of public/private pages directly equates to public/private functions in the app logic. See guestbook. cgi (transaction diagram is on next slide)

• Usually, a Web application has publicly accessible pages and others which are password protected (private). • The different pages generated by a Web application are determined by which functions are in its app logic. • Thus, a private page is one for which the app logic function first verifies password information before returning the page. • That means, the notion of public/private pages directly equates to public/private functions in the app logic. See guestbook. cgi (transaction diagram is on next slide)

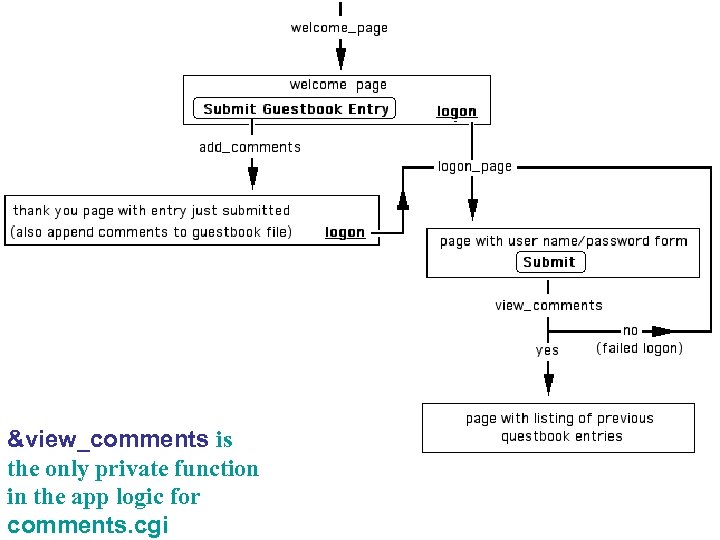

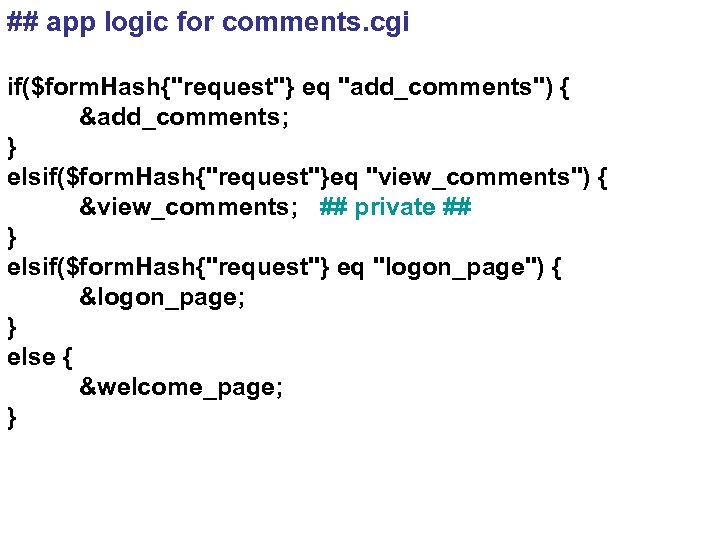

&view_comments is the only private function in the app logic for comments. cgi

&view_comments is the only private function in the app logic for comments. cgi

## app logic for comments. cgi if($form. Hash{"request"} eq "add_comments") { &add_comments; } elsif($form. Hash{"request"}eq "view_comments") { &view_comments; ## private ## } elsif($form. Hash{"request"} eq "logon_page") { &logon_page; } else { &welcome_page; }

## app logic for comments. cgi if($form. Hash{"request"} eq "add_comments") { &add_comments; } elsif($form. Hash{"request"}eq "view_comments") { &view_comments; ## private ## } elsif($form. Hash{"request"} eq "logon_page") { &logon_page; } else { &welcome_page; }

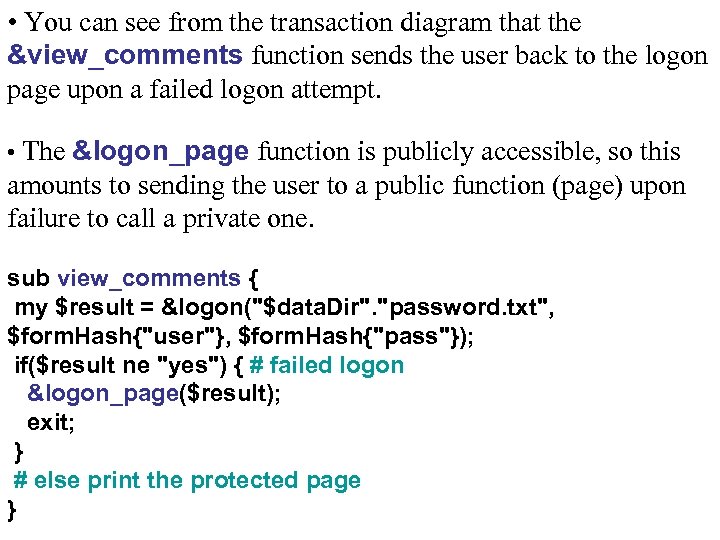

• You can see from the transaction diagram that the &view_comments function sends the user back to the logon page upon a failed logon attempt. • The &logon_page function is publicly accessible, so this amounts to sending the user to a public function (page) upon failure to call a private one. sub view_comments { my $result = &logon("$data. Dir". "password. txt", $form. Hash{"user"}, $form. Hash{"pass"}); if($result ne "yes") { # failed logon &logon_page($result); exit; } # else print the protected page }

• You can see from the transaction diagram that the &view_comments function sends the user back to the logon page upon a failed logon attempt. • The &logon_page function is publicly accessible, so this amounts to sending the user to a public function (page) upon failure to call a private one. sub view_comments { my $result = &logon("$data. Dir". "password. txt", $form. Hash{"user"}, $form. Hash{"pass"}); if($result ne "yes") { # failed logon &logon_page($result); exit; } # else print the protected page }

Logged on state -- the state of prolonged access to private pages (functions) in the application. • The main idea is that after one successful logon, the entire private portion of the application is available. • That might mean one logon allows you to call any of several private app logic functions. • Or one successful logon allows to call one private app logic function over and over again.

Logged on state -- the state of prolonged access to private pages (functions) in the application. • The main idea is that after one successful logon, the entire private portion of the application is available. • That might mean one logon allows you to call any of several private app logic functions. • Or one successful logon allows to call one private app logic function over and over again.

Here's how to implement logged on state: 1. Upon successful logon, create a session ID and state file. 2. Hide the session ID in every page subsequently returned to the user.

Here's how to implement logged on state: 1. Upon successful logon, create a session ID and state file. 2. Hide the session ID in every page subsequently returned to the user.

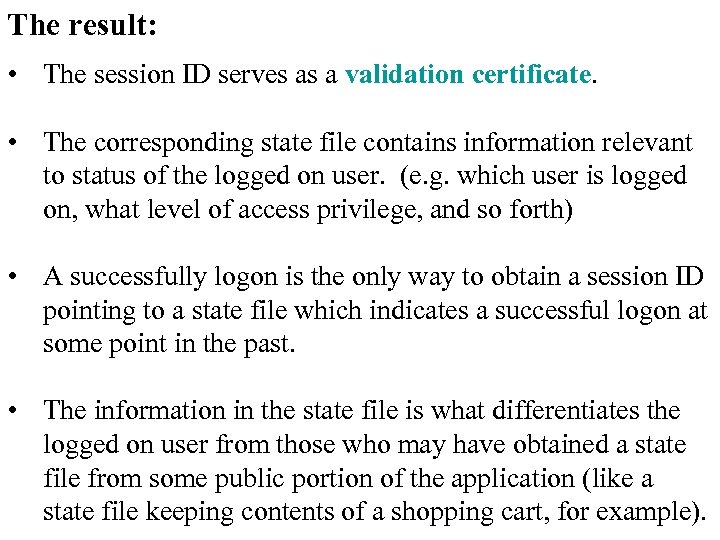

The result: • The session ID serves as a validation certificate. • The corresponding state file contains information relevant to status of the logged on user. (e. g. which user is logged on, what level of access privilege, and so forth) • A successfully logon is the only way to obtain a session ID pointing to a state file which indicates a successful logon at some point in the past. • The information in the state file is what differentiates the logged on user from those who may have obtained a state file from some public portion of the application (like a state file keeping contents of a shopping cart, for example).

The result: • The session ID serves as a validation certificate. • The corresponding state file contains information relevant to status of the logged on user. (e. g. which user is logged on, what level of access privilege, and so forth) • A successfully logon is the only way to obtain a session ID pointing to a state file which indicates a successful logon at some point in the past. • The information in the state file is what differentiates the logged on user from those who may have obtained a state file from some public portion of the application (like a state file keeping contents of a shopping cart, for example).

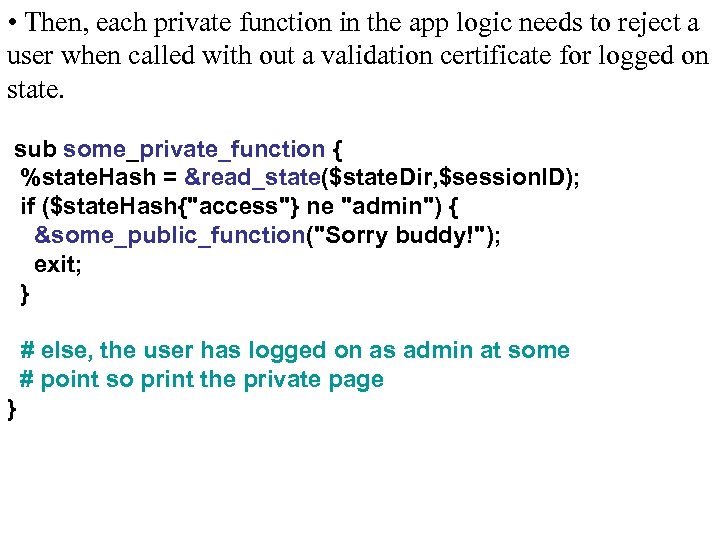

• Then, each private function in the app logic needs to reject a user when called with out a validation certificate for logged on state. sub some_private_function { %state. Hash = &read_state($state. Dir, $session. ID); if ($state. Hash{"access"} ne "admin") { &some_public_function("Sorry buddy!"); exit; } # else, the user has logged on as admin at some # point so print the private page }

• Then, each private function in the app logic needs to reject a user when called with out a validation certificate for logged on state. sub some_private_function { %state. Hash = &read_state($state. Dir, $session. ID); if ($state. Hash{"access"} ne "admin") { &some_public_function("Sorry buddy!"); exit; } # else, the user has logged on as admin at some # point so print the private page }

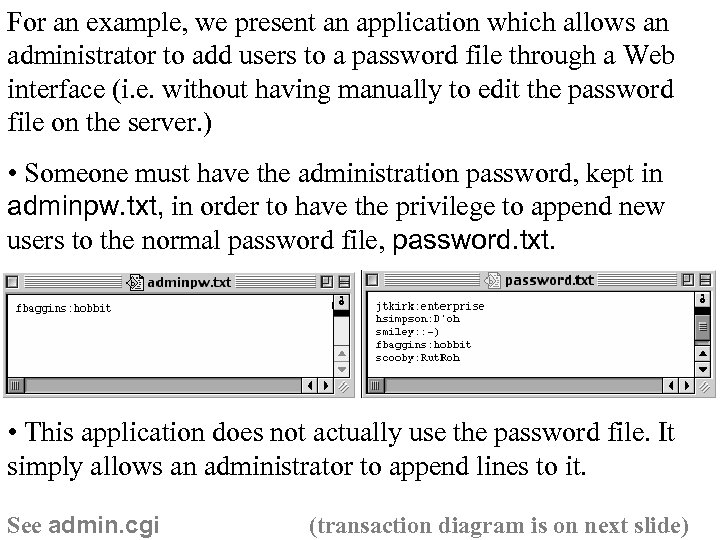

For an example, we present an application which allows an administrator to add users to a password file through a Web interface (i. e. without having manually to edit the password file on the server. ) • Someone must have the administration password, kept in adminpw. txt, in order to have the privilege to append new users to the normal password file, password. txt. • This application does not actually use the password file. It simply allows an administrator to append lines to it. See admin. cgi (transaction diagram is on next slide)

For an example, we present an application which allows an administrator to add users to a password file through a Web interface (i. e. without having manually to edit the password file on the server. ) • Someone must have the administration password, kept in adminpw. txt, in order to have the privilege to append new users to the normal password file, password. txt. • This application does not actually use the password file. It simply allows an administrator to append lines to it. See admin. cgi (transaction diagram is on next slide)

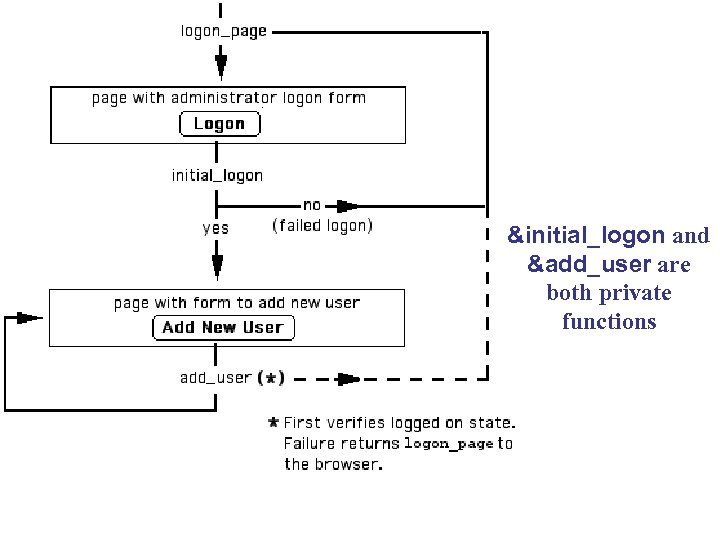

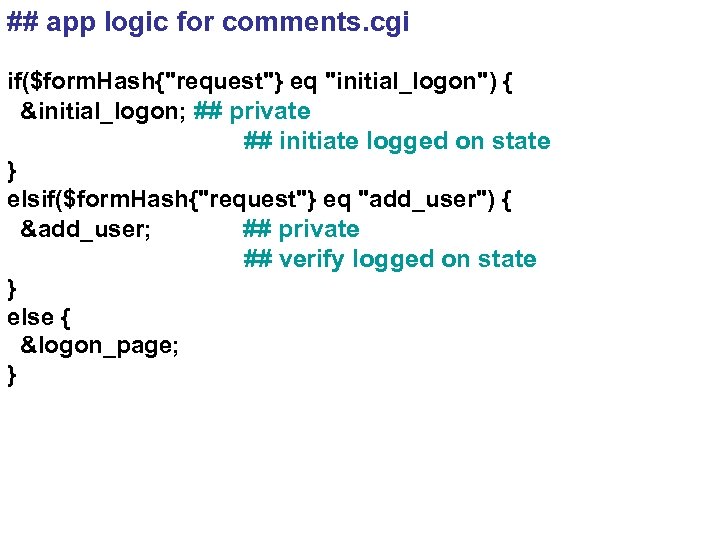

&initial_logon and &add_user are both private functions

&initial_logon and &add_user are both private functions

## app logic for comments. cgi if($form. Hash{"request"} eq "initial_logon") { &initial_logon; ## private ## initiate logged on state } elsif($form. Hash{"request"} eq "add_user") { &add_user; ## private ## verify logged on state } else { &logon_page; }

## app logic for comments. cgi if($form. Hash{"request"} eq "initial_logon") { &initial_logon; ## private ## initiate logged on state } elsif($form. Hash{"request"} eq "add_user") { &add_user; ## private ## verify logged on state } else { &logon_page; }

Note: Adding new user accounts for a Web application is a very common task. The previous example allowed an administrator to add users, but many Web applications allow you to add yourself as a user via an online form. Thus, we consolidated this process into a toolkit function, named &logon_new, which processes data submitted any form with the following functionality. • This function returns "yes" if the user is successfully added to the password file. • Otherwise it returns one of several descriptive failure messages like, "passwords do not match", for example. • As with all toolkit functions, full documentation can be found in the function library provided on the Web site.

Note: Adding new user accounts for a Web application is a very common task. The previous example allowed an administrator to add users, but many Web applications allow you to add yourself as a user via an online form. Thus, we consolidated this process into a toolkit function, named &logon_new, which processes data submitted any form with the following functionality. • This function returns "yes" if the user is successfully added to the password file. • Otherwise it returns one of several descriptive failure messages like, "passwords do not match", for example. • As with all toolkit functions, full documentation can be found in the function library provided on the Web site.

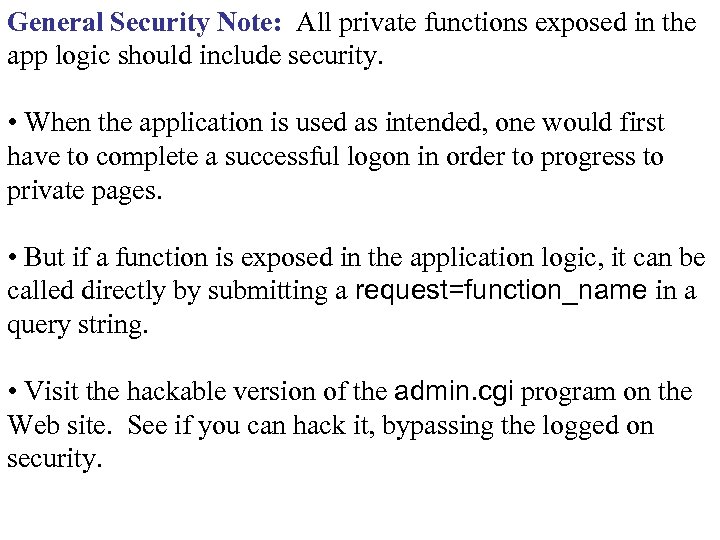

General Security Note: All private functions exposed in the app logic should include security. • When the application is used as intended, one would first have to complete a successful logon in order to progress to private pages. • But if a function is exposed in the application logic, it can be called directly by submitting a request=function_name in a query string. • Visit the hackable version of the admin. cgi program on the Web site. See if you can hack it, bypassing the logged on security.

General Security Note: All private functions exposed in the app logic should include security. • When the application is used as intended, one would first have to complete a successful logon in order to progress to private pages. • But if a function is exposed in the application logic, it can be called directly by submitting a request=function_name in a query string. • Visit the hackable version of the admin. cgi program on the Web site. See if you can hack it, bypassing the logged on security.

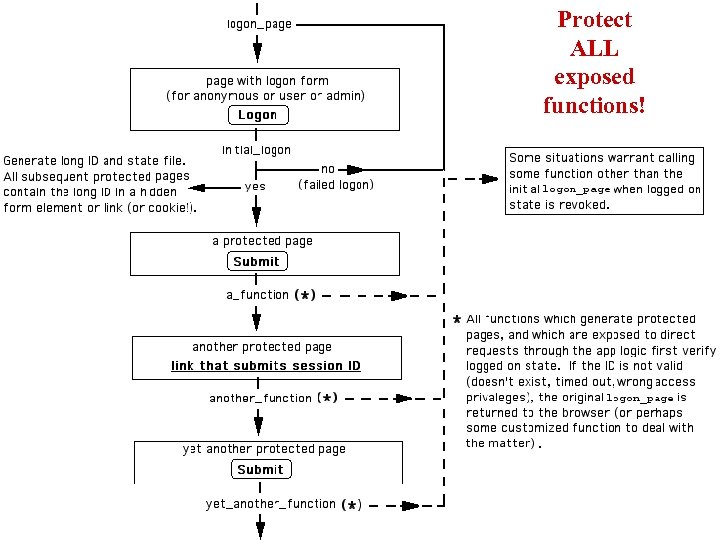

Protect ALL exposed functions!

Protect ALL exposed functions!

Note on validation certificates: The mere existence of a state file can be used to verify logged on state. if (!(-e "path/to/session. ID. state")) { &logon_page; # revoke session exit; } • Here, -e tests the existence of the file, returning true or false. • Successful logon gives a session ID (impossible to guess) and creates a corresponding state file. • Thus, submitting a valid session ID (corresponding file exists) is equivalent to having successfully logged on.

Note on validation certificates: The mere existence of a state file can be used to verify logged on state. if (!(-e "path/to/session. ID. state")) { &logon_page; # revoke session exit; } • Here, -e tests the existence of the file, returning true or false. • Successful logon gives a session ID (impossible to guess) and creates a corresponding state file. • Thus, submitting a valid session ID (corresponding file exists) is equivalent to having successfully logged on.

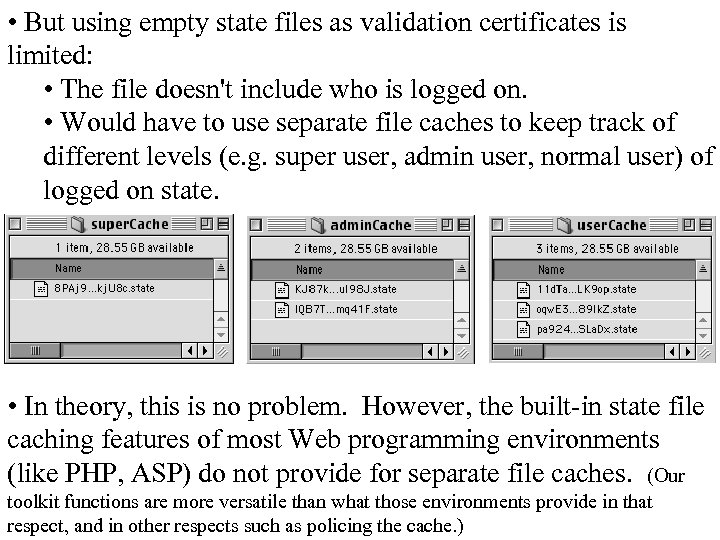

• But using empty state files as validation certificates is limited: • The file doesn't include who is logged on. • Would have to use separate file caches to keep track of different levels (e. g. super user, admin user, normal user) of logged on state. • In theory, this is no problem. However, the built-in state file caching features of most Web programming environments (like PHP, ASP) do not provide for separate file caches. (Our toolkit functions are more versatile than what those environments provide in that respect, and in other respects such as policing the cache. )

• But using empty state files as validation certificates is limited: • The file doesn't include who is logged on. • Would have to use separate file caches to keep track of different levels (e. g. super user, admin user, normal user) of logged on state. • In theory, this is no problem. However, the built-in state file caching features of most Web programming environments (like PHP, ASP) do not provide for separate file caches. (Our toolkit functions are more versatile than what those environments provide in that respect, and in other respects such as policing the cache. )

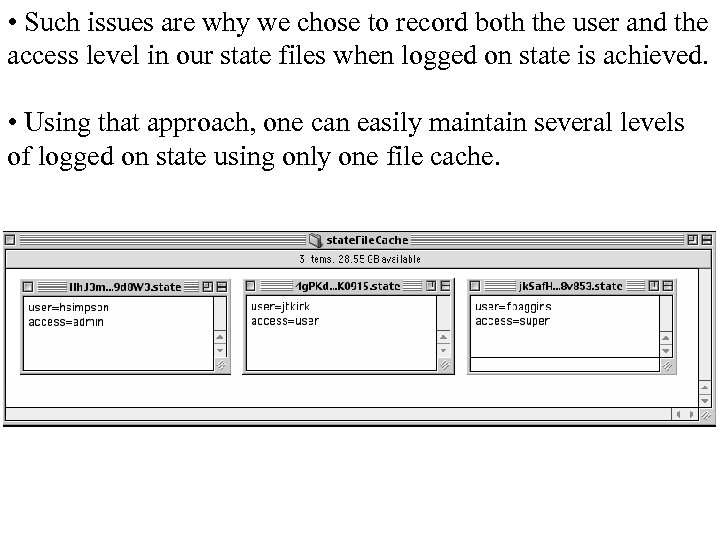

• Such issues are why we chose to record both the user and the access level in our state files when logged on state is achieved. • Using that approach, one can easily maintain several levels of logged on state using only one file cache.

• Such issues are why we chose to record both the user and the access level in our state files when logged on state is achieved. • Using that approach, one can easily maintain several levels of logged on state using only one file cache.

Note on Session Timeouts: Many Web applications are equipped to revoke sessions after some period of inactivity, maybe an hour or even a day. • Since this is a common need in Web applications, the final version of our &read_state toolkit function has optional parameters which can be used to easily implement session timeouts. • When attempting to read a state file, if it finds the file to be old or it doesn't exist (perhaps because it was policed), then the user is given some sort of error page saying the session was revoked due to inactivity for some period of time. See source code for the final version of the &read_state function in Chap 7 CGI. lib.

Note on Session Timeouts: Many Web applications are equipped to revoke sessions after some period of inactivity, maybe an hour or even a day. • Since this is a common need in Web applications, the final version of our &read_state toolkit function has optional parameters which can be used to easily implement session timeouts. • When attempting to read a state file, if it finds the file to be old or it doesn't exist (perhaps because it was policed), then the user is given some sort of error page saying the session was revoked due to inactivity for some period of time. See source code for the final version of the &read_state function in Chap 7 CGI. lib.