83340717190bde2cb158e791fed96ec2.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 62

Chapter 4 Section A Physical Principles of Propagation July, 1998 RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 1

Chapter 4 Section A Physical Principles of Propagation July, 1998 RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 1

Introduction to Propagation n Propagation is the heart of every radio link. During propagation, many processes act on the radio signal. • attenuation – the signal amplitude is reduced by various natural mechanisms. If there is too much attenuation, the signal will fall below the reliable detection threshold at the receiver. Attenuation is the most important single factor in propagation. • multipath and group delay distortions – the signal diffracts and reflects off irregularly shaped objects, producing a host of components which arrive in random timings and random RF phases at the receiver. This blurs pulses and also produces intermittent signal cancellation and reinforcement. These effects are overcome through a variety of special techniques • time variability - signal strength and quality varies with time, often dramatically • space variability - signal strength and quality varies with location and distance • frequency variability - signal strength and quality differs on different frequencies n To master propagation and effectively design wireless systems, you must know: • Physics: understand the basic propagation processes • Measurement: obtain data on propagation behavior in area of interest • Statistics: analyze known data, extrapolate to predict the unknown • Modelmaking: formalize all the above into useful models July, 1998 RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 2

Introduction to Propagation n Propagation is the heart of every radio link. During propagation, many processes act on the radio signal. • attenuation – the signal amplitude is reduced by various natural mechanisms. If there is too much attenuation, the signal will fall below the reliable detection threshold at the receiver. Attenuation is the most important single factor in propagation. • multipath and group delay distortions – the signal diffracts and reflects off irregularly shaped objects, producing a host of components which arrive in random timings and random RF phases at the receiver. This blurs pulses and also produces intermittent signal cancellation and reinforcement. These effects are overcome through a variety of special techniques • time variability - signal strength and quality varies with time, often dramatically • space variability - signal strength and quality varies with location and distance • frequency variability - signal strength and quality differs on different frequencies n To master propagation and effectively design wireless systems, you must know: • Physics: understand the basic propagation processes • Measurement: obtain data on propagation behavior in area of interest • Statistics: analyze known data, extrapolate to predict the unknown • Modelmaking: formalize all the above into useful models July, 1998 RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 2

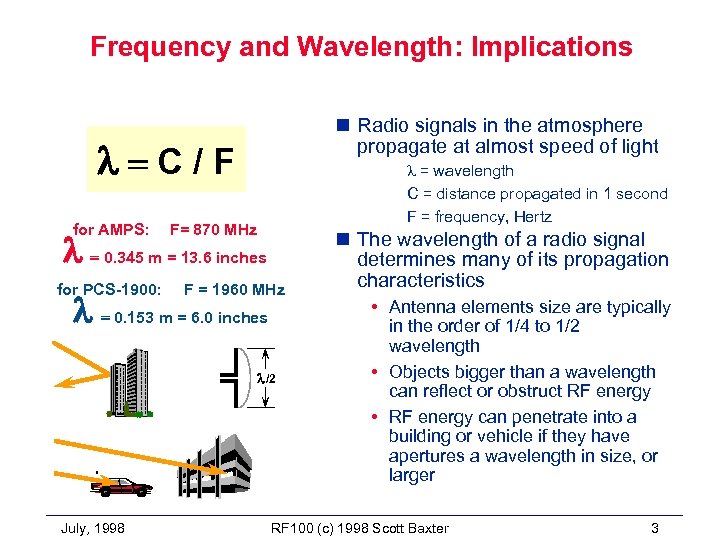

Frequency and Wavelength: Implications n Radio signals in the atmosphere propagate at almost speed of light l=C/F for AMPS: l = wavelength C = distance propagated in 1 second F = frequency, Hertz F= 870 MHz l = 0. 345 m = 13. 6 inches for PCS-1900: F = 1960 MHz l = 0. 153 m = 6. 0 inches l/2 July, 1998 n The wavelength of a radio signal determines many of its propagation characteristics • Antenna elements size are typically in the order of 1/4 to 1/2 wavelength • Objects bigger than a wavelength can reflect or obstruct RF energy • RF energy can penetrate into a building or vehicle if they have apertures a wavelength in size, or larger RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 3

Frequency and Wavelength: Implications n Radio signals in the atmosphere propagate at almost speed of light l=C/F for AMPS: l = wavelength C = distance propagated in 1 second F = frequency, Hertz F= 870 MHz l = 0. 345 m = 13. 6 inches for PCS-1900: F = 1960 MHz l = 0. 153 m = 6. 0 inches l/2 July, 1998 n The wavelength of a radio signal determines many of its propagation characteristics • Antenna elements size are typically in the order of 1/4 to 1/2 wavelength • Objects bigger than a wavelength can reflect or obstruct RF energy • RF energy can penetrate into a building or vehicle if they have apertures a wavelength in size, or larger RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 3

Propagation Effects of Earth’s Atmosphere n Earth’s unique atmosphere supports life (ours included) and also introduces many propagation effects -- some useful, some troublesome n Skywave Propagation: reflection from Ionized Layers • LF and HF frequencies (below roughly 50 MHz. ) are routinely reflected off layers of the upper atmosphere which become ionized by the sun • this phenomena produces intermittent worldwide propagation and occasional total outages • this phenomena is strongly correlated with frequency, day/night cycles, variations in earth’s magnetic field, 11 -year sunspot cycle • these effects are negligible for wireless systems at their much-higher frequencies July, 1998 RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 4

Propagation Effects of Earth’s Atmosphere n Earth’s unique atmosphere supports life (ours included) and also introduces many propagation effects -- some useful, some troublesome n Skywave Propagation: reflection from Ionized Layers • LF and HF frequencies (below roughly 50 MHz. ) are routinely reflected off layers of the upper atmosphere which become ionized by the sun • this phenomena produces intermittent worldwide propagation and occasional total outages • this phenomena is strongly correlated with frequency, day/night cycles, variations in earth’s magnetic field, 11 -year sunspot cycle • these effects are negligible for wireless systems at their much-higher frequencies July, 1998 RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 4

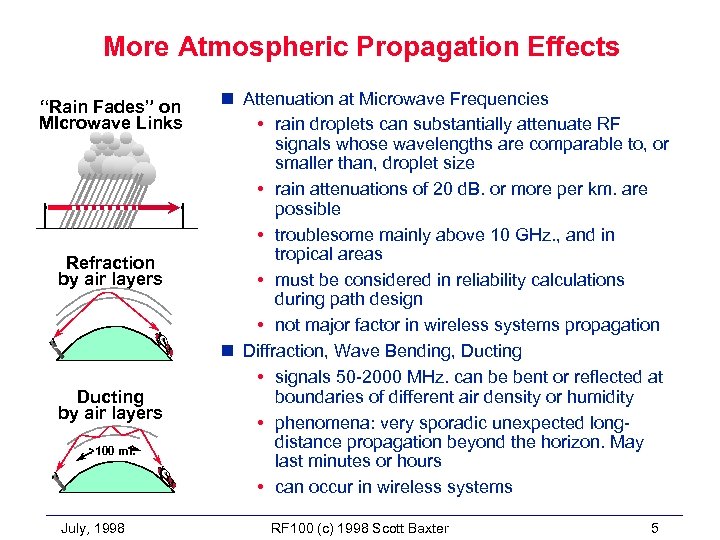

More Atmospheric Propagation Effects “Rain Fades” on MIcrowave Links Refraction by air layers Ducting by air layers >100 mi. July, 1998 n Attenuation at Microwave Frequencies • rain droplets can substantially attenuate RF signals whose wavelengths are comparable to, or smaller than, droplet size • rain attenuations of 20 d. B. or more per km. are possible • troublesome mainly above 10 GHz. , and in tropical areas • must be considered in reliability calculations during path design • not major factor in wireless systems propagation n Diffraction, Wave Bending, Ducting • signals 50 -2000 MHz. can be bent or reflected at boundaries of different air density or humidity • phenomena: very sporadic unexpected longdistance propagation beyond the horizon. May last minutes or hours • can occur in wireless systems RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 5

More Atmospheric Propagation Effects “Rain Fades” on MIcrowave Links Refraction by air layers Ducting by air layers >100 mi. July, 1998 n Attenuation at Microwave Frequencies • rain droplets can substantially attenuate RF signals whose wavelengths are comparable to, or smaller than, droplet size • rain attenuations of 20 d. B. or more per km. are possible • troublesome mainly above 10 GHz. , and in tropical areas • must be considered in reliability calculations during path design • not major factor in wireless systems propagation n Diffraction, Wave Bending, Ducting • signals 50 -2000 MHz. can be bent or reflected at boundaries of different air density or humidity • phenomena: very sporadic unexpected longdistance propagation beyond the horizon. May last minutes or hours • can occur in wireless systems RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 5

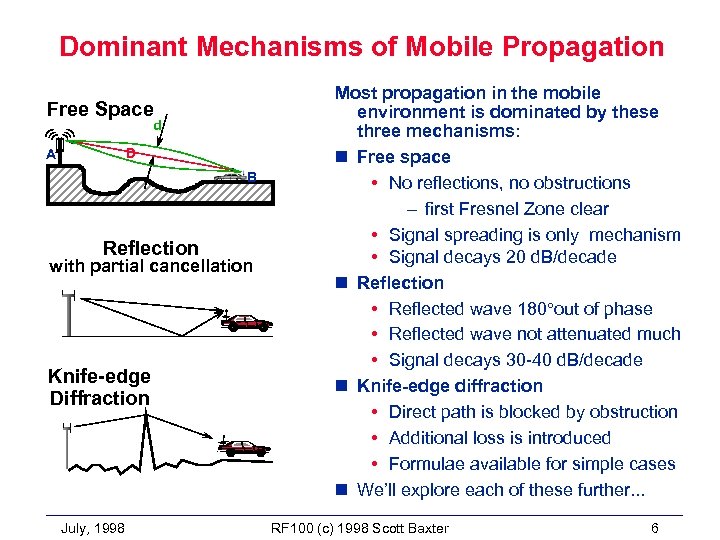

Dominant Mechanisms of Mobile Propagation Free Space d D A B Reflection with partial cancellation Knife-edge Diffraction July, 1998 Most propagation in the mobile environment is dominated by these three mechanisms: n Free space • No reflections, no obstructions – first Fresnel Zone clear • Signal spreading is only mechanism • Signal decays 20 d. B/decade n Reflection • Reflected wave 180°out of phase • Reflected wave not attenuated much • Signal decays 30 -40 d. B/decade n Knife-edge diffraction • Direct path is blocked by obstruction • Additional loss is introduced • Formulae available for simple cases n We’ll explore each of these further. . . RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 6

Dominant Mechanisms of Mobile Propagation Free Space d D A B Reflection with partial cancellation Knife-edge Diffraction July, 1998 Most propagation in the mobile environment is dominated by these three mechanisms: n Free space • No reflections, no obstructions – first Fresnel Zone clear • Signal spreading is only mechanism • Signal decays 20 d. B/decade n Reflection • Reflected wave 180°out of phase • Reflected wave not attenuated much • Signal decays 30 -40 d. B/decade n Knife-edge diffraction • Direct path is blocked by obstruction • Additional loss is introduced • Formulae available for simple cases n We’ll explore each of these further. . . RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 6

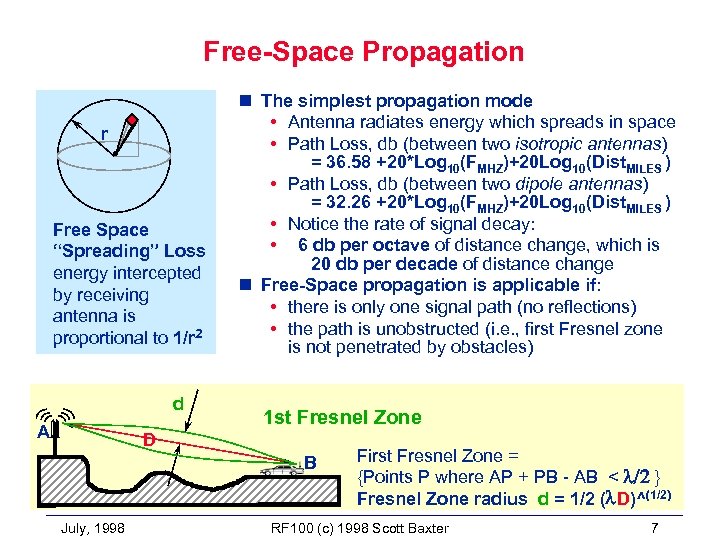

Free-Space Propagation r Free Space “Spreading” Loss energy intercepted by receiving antenna is proportional to 1/r 2 d A n The simplest propagation mode • Antenna radiates energy which spreads in space • Path Loss, db (between two isotropic antennas) = 36. 58 +20*Log 10(FMHZ)+20 Log 10(Dist. MILES ) • Path Loss, db (between two dipole antennas) = 32. 26 +20*Log 10(FMHZ)+20 Log 10(Dist. MILES ) • Notice the rate of signal decay: • 6 db per octave of distance change, which is 20 db per decade of distance change n Free-Space propagation is applicable if: • there is only one signal path (no reflections) • the path is unobstructed (i. e. , first Fresnel zone is not penetrated by obstacles) 1 st Fresnel Zone D B July, 1998 First Fresnel Zone = {Points P where AP + PB - AB < l/2 } Fresnel Zone radius d = 1/2 (l. D)^(1/2) RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 7

Free-Space Propagation r Free Space “Spreading” Loss energy intercepted by receiving antenna is proportional to 1/r 2 d A n The simplest propagation mode • Antenna radiates energy which spreads in space • Path Loss, db (between two isotropic antennas) = 36. 58 +20*Log 10(FMHZ)+20 Log 10(Dist. MILES ) • Path Loss, db (between two dipole antennas) = 32. 26 +20*Log 10(FMHZ)+20 Log 10(Dist. MILES ) • Notice the rate of signal decay: • 6 db per octave of distance change, which is 20 db per decade of distance change n Free-Space propagation is applicable if: • there is only one signal path (no reflections) • the path is unobstructed (i. e. , first Fresnel zone is not penetrated by obstacles) 1 st Fresnel Zone D B July, 1998 First Fresnel Zone = {Points P where AP + PB - AB < l/2 } Fresnel Zone radius d = 1/2 (l. D)^(1/2) RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 7

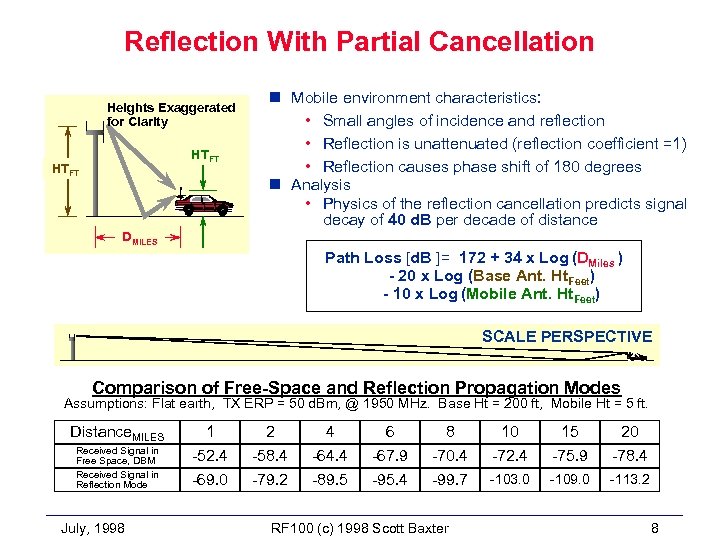

Reflection With Partial Cancellation Heights Exaggerated for Clarity HTFT n Mobile environment characteristics: • Small angles of incidence and reflection • Reflection is unattenuated (reflection coefficient =1) • Reflection causes phase shift of 180 degrees n Analysis • Physics of the reflection cancellation predicts signal decay of 40 d. B per decade of distance DMILES Path Loss [d. B ]= 172 + 34 x Log (DMiles ) - 20 x Log (Base Ant. Ht. Feet) - 10 x Log (Mobile Ant. Ht. Feet) SCALE PERSPECTIVE Comparison of Free-Space and Reflection Propagation Modes Assumptions: Flat earth, TX ERP = 50 d. Bm, @ 1950 MHz. Base Ht = 200 ft, Mobile Ht = 5 ft. Distance. MILES Received Signal in Free Space, DBM Received Signal in Reflection Mode July, 1998 1 -52. 4 2 -58. 4 4 -64. 4 6 -67. 9 8 -70. 4 10 -72. 4 15 -75. 9 20 -78. 4 -69. 0 -79. 2 -89. 5 -95. 4 -99. 7 -103. 0 -109. 0 -113. 2 RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 8

Reflection With Partial Cancellation Heights Exaggerated for Clarity HTFT n Mobile environment characteristics: • Small angles of incidence and reflection • Reflection is unattenuated (reflection coefficient =1) • Reflection causes phase shift of 180 degrees n Analysis • Physics of the reflection cancellation predicts signal decay of 40 d. B per decade of distance DMILES Path Loss [d. B ]= 172 + 34 x Log (DMiles ) - 20 x Log (Base Ant. Ht. Feet) - 10 x Log (Mobile Ant. Ht. Feet) SCALE PERSPECTIVE Comparison of Free-Space and Reflection Propagation Modes Assumptions: Flat earth, TX ERP = 50 d. Bm, @ 1950 MHz. Base Ht = 200 ft, Mobile Ht = 5 ft. Distance. MILES Received Signal in Free Space, DBM Received Signal in Reflection Mode July, 1998 1 -52. 4 2 -58. 4 4 -64. 4 6 -67. 9 8 -70. 4 10 -72. 4 15 -75. 9 20 -78. 4 -69. 0 -79. 2 -89. 5 -95. 4 -99. 7 -103. 0 -109. 0 -113. 2 RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 8

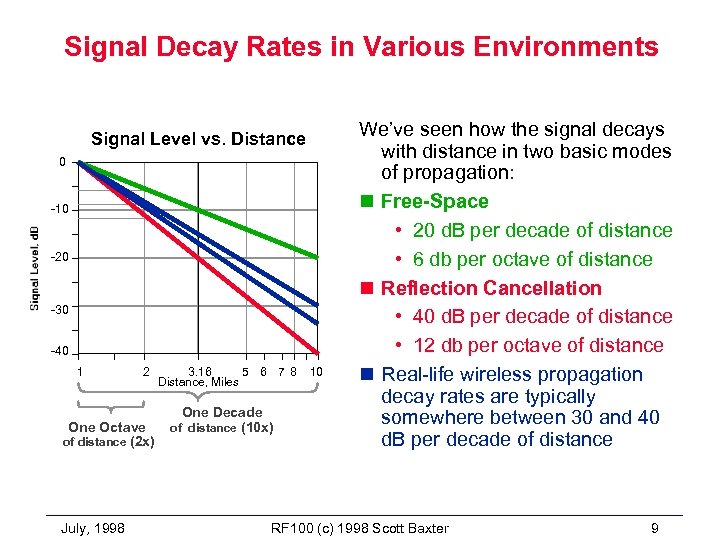

Signal Decay Rates in Various Environments Signal Level vs. Distance 0 -10 -20 -30 -40 1 2 One Octave of distance (2 x) July, 1998 3. 16 5 6 7 8 Distance, Miles One Decade of distance (10 x) 10 We’ve seen how the signal decays with distance in two basic modes of propagation: n Free-Space • 20 d. B per decade of distance • 6 db per octave of distance n Reflection Cancellation • 40 d. B per decade of distance • 12 db per octave of distance n Real-life wireless propagation decay rates are typically somewhere between 30 and 40 d. B per decade of distance RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 9

Signal Decay Rates in Various Environments Signal Level vs. Distance 0 -10 -20 -30 -40 1 2 One Octave of distance (2 x) July, 1998 3. 16 5 6 7 8 Distance, Miles One Decade of distance (10 x) 10 We’ve seen how the signal decays with distance in two basic modes of propagation: n Free-Space • 20 d. B per decade of distance • 6 db per octave of distance n Reflection Cancellation • 40 d. B per decade of distance • 12 db per octave of distance n Real-life wireless propagation decay rates are typically somewhere between 30 and 40 d. B per decade of distance RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 9

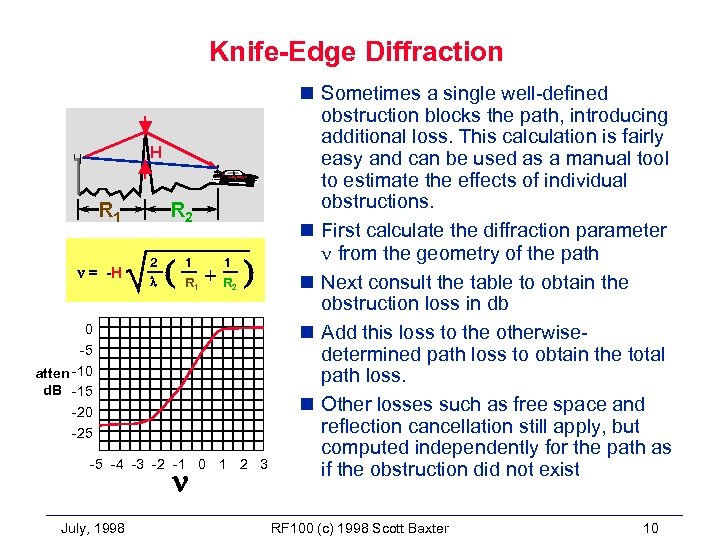

Knife-Edge Diffraction H R 1 n = -H R 2 2 l ( 1 R 1 + 1 R 2 ) 0 -5 atten -10 d. B -15 -20 -25 -5 -4 -3 -2 -1 0 1 2 3 n July, 1998 n Sometimes a single well-defined obstruction blocks the path, introducing additional loss. This calculation is fairly easy and can be used as a manual tool to estimate the effects of individual obstructions. n First calculate the diffraction parameter n from the geometry of the path n Next consult the table to obtain the obstruction loss in db n Add this loss to the otherwisedetermined path loss to obtain the total path loss. n Other losses such as free space and reflection cancellation still apply, but computed independently for the path as if the obstruction did not exist RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 10

Knife-Edge Diffraction H R 1 n = -H R 2 2 l ( 1 R 1 + 1 R 2 ) 0 -5 atten -10 d. B -15 -20 -25 -5 -4 -3 -2 -1 0 1 2 3 n July, 1998 n Sometimes a single well-defined obstruction blocks the path, introducing additional loss. This calculation is fairly easy and can be used as a manual tool to estimate the effects of individual obstructions. n First calculate the diffraction parameter n from the geometry of the path n Next consult the table to obtain the obstruction loss in db n Add this loss to the otherwisedetermined path loss to obtain the total path loss. n Other losses such as free space and reflection cancellation still apply, but computed independently for the path as if the obstruction did not exist RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 10

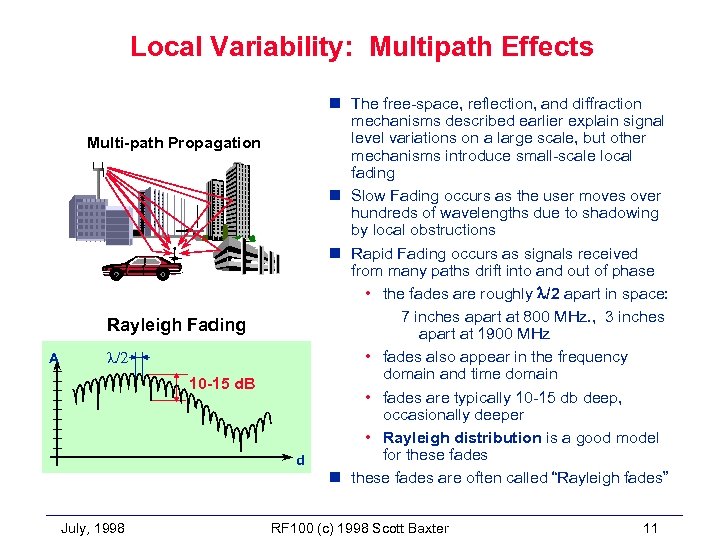

Local Variability: Multipath Effects Multi-path Propagation Rayleigh Fading A l/2 10 -15 d. B d July, 1998 n The free-space, reflection, and diffraction mechanisms described earlier explain signal level variations on a large scale, but other mechanisms introduce small-scale local fading n Slow Fading occurs as the user moves over hundreds of wavelengths due to shadowing by local obstructions n Rapid Fading occurs as signals received from many paths drift into and out of phase • the fades are roughly l/2 apart in space: 7 inches apart at 800 MHz. , 3 inches apart at 1900 MHz • fades also appear in the frequency domain and time domain • fades are typically 10 -15 db deep, occasionally deeper • Rayleigh distribution is a good model for these fades n these fades are often called “Rayleigh fades” RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 11

Local Variability: Multipath Effects Multi-path Propagation Rayleigh Fading A l/2 10 -15 d. B d July, 1998 n The free-space, reflection, and diffraction mechanisms described earlier explain signal level variations on a large scale, but other mechanisms introduce small-scale local fading n Slow Fading occurs as the user moves over hundreds of wavelengths due to shadowing by local obstructions n Rapid Fading occurs as signals received from many paths drift into and out of phase • the fades are roughly l/2 apart in space: 7 inches apart at 800 MHz. , 3 inches apart at 1900 MHz • fades also appear in the frequency domain and time domain • fades are typically 10 -15 db deep, occasionally deeper • Rayleigh distribution is a good model for these fades n these fades are often called “Rayleigh fades” RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 11

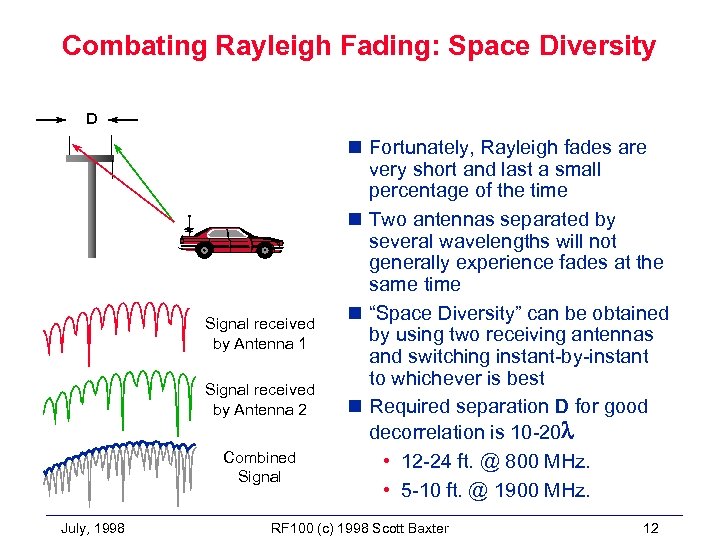

Combating Rayleigh Fading: Space Diversity D Signal received by Antenna 1 Signal received by Antenna 2 Combined Signal July, 1998 n Fortunately, Rayleigh fades are very short and last a small percentage of the time n Two antennas separated by several wavelengths will not generally experience fades at the same time n “Space Diversity” can be obtained by using two receiving antennas and switching instant-by-instant to whichever is best n Required separation D for good decorrelation is 10 -20 l • 12 -24 ft. @ 800 MHz. • 5 -10 ft. @ 1900 MHz. RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 12

Combating Rayleigh Fading: Space Diversity D Signal received by Antenna 1 Signal received by Antenna 2 Combined Signal July, 1998 n Fortunately, Rayleigh fades are very short and last a small percentage of the time n Two antennas separated by several wavelengths will not generally experience fades at the same time n “Space Diversity” can be obtained by using two receiving antennas and switching instant-by-instant to whichever is best n Required separation D for good decorrelation is 10 -20 l • 12 -24 ft. @ 800 MHz. • 5 -10 ft. @ 1900 MHz. RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 12

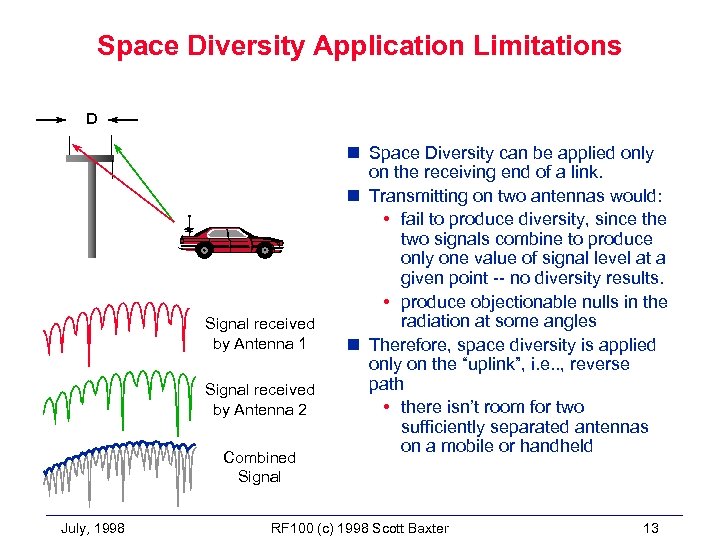

Space Diversity Application Limitations D Signal received by Antenna 1 Signal received by Antenna 2 Combined Signal July, 1998 n Space Diversity can be applied only on the receiving end of a link. n Transmitting on two antennas would: • fail to produce diversity, since the two signals combine to produce only one value of signal level at a given point -- no diversity results. • produce objectionable nulls in the radiation at some angles n Therefore, space diversity is applied only on the “uplink”, i. e. . , reverse path • there isn’t room for two sufficiently separated antennas on a mobile or handheld RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 13

Space Diversity Application Limitations D Signal received by Antenna 1 Signal received by Antenna 2 Combined Signal July, 1998 n Space Diversity can be applied only on the receiving end of a link. n Transmitting on two antennas would: • fail to produce diversity, since the two signals combine to produce only one value of signal level at a given point -- no diversity results. • produce objectionable nulls in the radiation at some angles n Therefore, space diversity is applied only on the “uplink”, i. e. . , reverse path • there isn’t room for two sufficiently separated antennas on a mobile or handheld RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 13

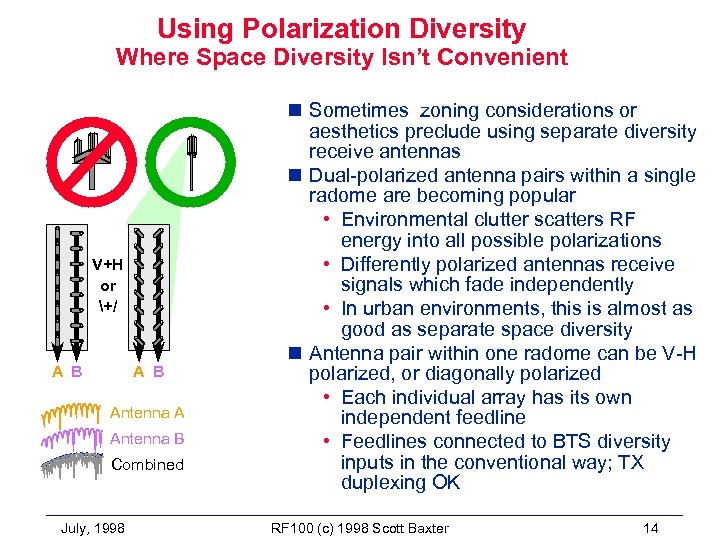

Using Polarization Diversity Where Space Diversity Isn’t Convenient V+H or +/ A B Antenna A Antenna B Combined July, 1998 n Sometimes zoning considerations or aesthetics preclude using separate diversity receive antennas n Dual-polarized antenna pairs within a single radome are becoming popular • Environmental clutter scatters RF energy into all possible polarizations • Differently polarized antennas receive signals which fade independently • In urban environments, this is almost as good as separate space diversity n Antenna pair within one radome can be V-H polarized, or diagonally polarized • Each individual array has its own independent feedline • Feedlines connected to BTS diversity inputs in the conventional way; TX duplexing OK RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 14

Using Polarization Diversity Where Space Diversity Isn’t Convenient V+H or +/ A B Antenna A Antenna B Combined July, 1998 n Sometimes zoning considerations or aesthetics preclude using separate diversity receive antennas n Dual-polarized antenna pairs within a single radome are becoming popular • Environmental clutter scatters RF energy into all possible polarizations • Differently polarized antennas receive signals which fade independently • In urban environments, this is almost as good as separate space diversity n Antenna pair within one radome can be V-H polarized, or diagonally polarized • Each individual array has its own independent feedline • Feedlines connected to BTS diversity inputs in the conventional way; TX duplexing OK RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 14

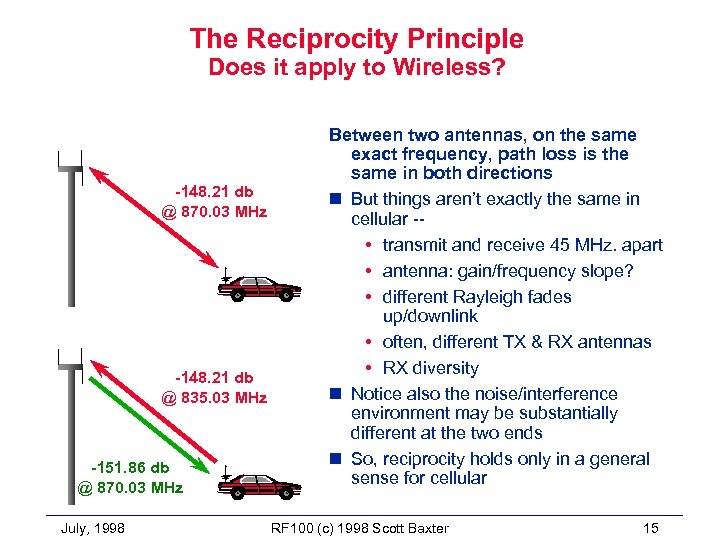

The Reciprocity Principle Does it apply to Wireless? -148. 21 db @ 870. 03 MHz -148. 21 db @ 835. 03 MHz -151. 86 db @ 870. 03 MHz July, 1998 Between two antennas, on the same exact frequency, path loss is the same in both directions n But things aren’t exactly the same in cellular - • transmit and receive 45 MHz. apart • antenna: gain/frequency slope? • different Rayleigh fades up/downlink • often, different TX & RX antennas • RX diversity n Notice also the noise/interference environment may be substantially different at the two ends n So, reciprocity holds only in a general sense for cellular RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 15

The Reciprocity Principle Does it apply to Wireless? -148. 21 db @ 870. 03 MHz -148. 21 db @ 835. 03 MHz -151. 86 db @ 870. 03 MHz July, 1998 Between two antennas, on the same exact frequency, path loss is the same in both directions n But things aren’t exactly the same in cellular - • transmit and receive 45 MHz. apart • antenna: gain/frequency slope? • different Rayleigh fades up/downlink • often, different TX & RX antennas • RX diversity n Notice also the noise/interference environment may be substantially different at the two ends n So, reciprocity holds only in a general sense for cellular RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 15

Chapter 4 Section B Propagation Models July, 1998 RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 16

Chapter 4 Section B Propagation Models July, 1998 RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 16

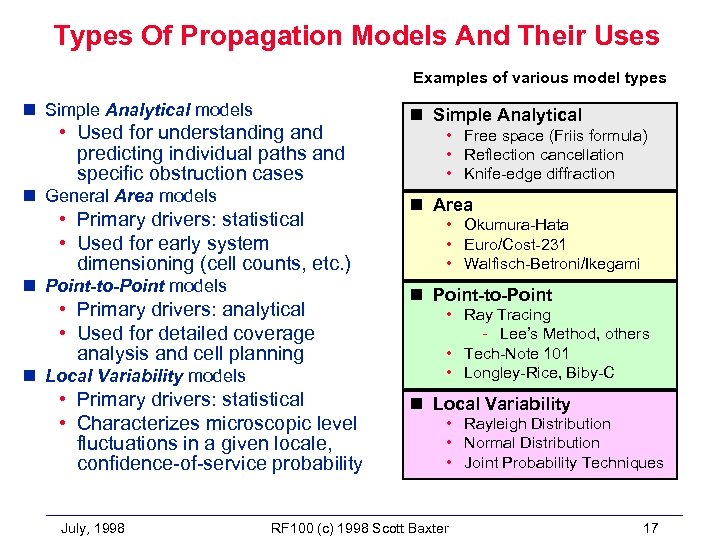

Types Of Propagation Models And Their Uses Examples of various model types n Simple Analytical models • Used for understanding and predicting individual paths and specific obstruction cases n General Area models • Primary drivers: statistical • Used for early system dimensioning (cell counts, etc. ) n Point-to-Point models • Primary drivers: analytical • Used for detailed coverage analysis and cell planning n Local Variability models • Primary drivers: statistical • Characterizes microscopic level fluctuations in a given locale, confidence-of-service probability July, 1998 n Simple Analytical • Free space (Friis formula) • Reflection cancellation • Knife-edge diffraction n Area • Okumura-Hata • Euro/Cost-231 • Walfisch-Betroni/Ikegami n Point-to-Point • Ray Tracing - Lee’s Method, others • Tech-Note 101 • Longley-Rice, Biby-C n Local Variability • Rayleigh Distribution • Normal Distribution • Joint Probability Techniques RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 17

Types Of Propagation Models And Their Uses Examples of various model types n Simple Analytical models • Used for understanding and predicting individual paths and specific obstruction cases n General Area models • Primary drivers: statistical • Used for early system dimensioning (cell counts, etc. ) n Point-to-Point models • Primary drivers: analytical • Used for detailed coverage analysis and cell planning n Local Variability models • Primary drivers: statistical • Characterizes microscopic level fluctuations in a given locale, confidence-of-service probability July, 1998 n Simple Analytical • Free space (Friis formula) • Reflection cancellation • Knife-edge diffraction n Area • Okumura-Hata • Euro/Cost-231 • Walfisch-Betroni/Ikegami n Point-to-Point • Ray Tracing - Lee’s Method, others • Tech-Note 101 • Longley-Rice, Biby-C n Local Variability • Rayleigh Distribution • Normal Distribution • Joint Probability Techniques RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 17

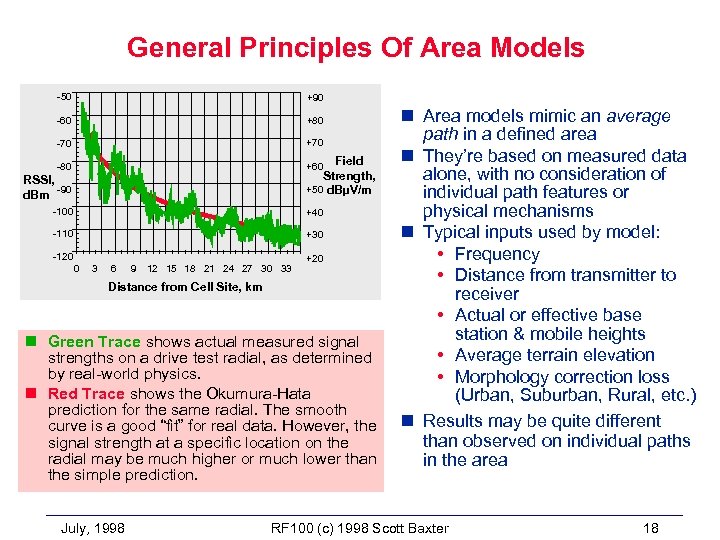

General Principles Of Area Models -50 +90 -60 +80 -70 +70 -80 +60 Field Strength, +50 d. BµV/m RSSI, -90 d. Bm -100 +40 -110 +30 -120 0 3 6 9 12 15 18 21 24 27 30 33 +20 Distance from Cell Site, km n Green Trace shows actual measured signal strengths on a drive test radial, as determined by real-world physics. n Red Trace shows the Okumura-Hata prediction for the same radial. The smooth curve is a good “fit” for real data. However, the signal strength at a specific location on the radial may be much higher or much lower than the simple prediction. July, 1998 n Area models mimic an average path in a defined area n They’re based on measured data alone, with no consideration of individual path features or physical mechanisms n Typical inputs used by model: • Frequency • Distance from transmitter to receiver • Actual or effective base station & mobile heights • Average terrain elevation • Morphology correction loss (Urban, Suburban, Rural, etc. ) n Results may be quite different than observed on individual paths in the area RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 18

General Principles Of Area Models -50 +90 -60 +80 -70 +70 -80 +60 Field Strength, +50 d. BµV/m RSSI, -90 d. Bm -100 +40 -110 +30 -120 0 3 6 9 12 15 18 21 24 27 30 33 +20 Distance from Cell Site, km n Green Trace shows actual measured signal strengths on a drive test radial, as determined by real-world physics. n Red Trace shows the Okumura-Hata prediction for the same radial. The smooth curve is a good “fit” for real data. However, the signal strength at a specific location on the radial may be much higher or much lower than the simple prediction. July, 1998 n Area models mimic an average path in a defined area n They’re based on measured data alone, with no consideration of individual path features or physical mechanisms n Typical inputs used by model: • Frequency • Distance from transmitter to receiver • Actual or effective base station & mobile heights • Average terrain elevation • Morphology correction loss (Urban, Suburban, Rural, etc. ) n Results may be quite different than observed on individual paths in the area RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 18

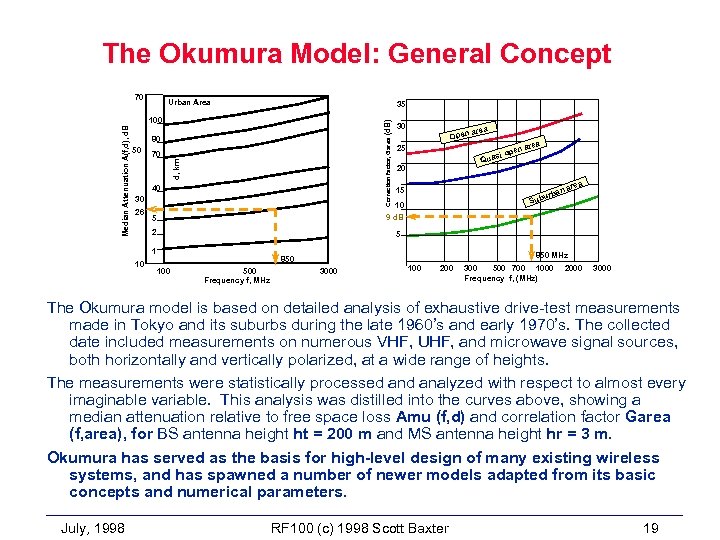

The Okumura Model: General Concept 70 Urban Area 35 50 (d. B) Correction factor, Garea 80 70 d, km Median Attenuation A(f, d), d. B 100 40 30 26 Open 5 area 25 pen io uas Q 20 area 15 rb ubu ea r an a S 10 9 d. B 2 5 1 10 30 850 MHz 850 100 500 Frequency f, MHz 3000 100 200 300 500 700 1000 Frequency f, (MHz) 2000 3000 The Okumura model is based on detailed analysis of exhaustive drive-test measurements made in Tokyo and its suburbs during the late 1960’s and early 1970’s. The collected date included measurements on numerous VHF, UHF, and microwave signal sources, both horizontally and vertically polarized, at a wide range of heights. The measurements were statistically processed analyzed with respect to almost every imaginable variable. This analysis was distilled into the curves above, showing a median attenuation relative to free space loss Amu (f, d) and correlation factor Garea (f, area), for BS antenna height ht = 200 m and MS antenna height hr = 3 m. Okumura has served as the basis for high-level design of many existing wireless systems, and has spawned a number of newer models adapted from its basic concepts and numerical parameters. July, 1998 RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 19

The Okumura Model: General Concept 70 Urban Area 35 50 (d. B) Correction factor, Garea 80 70 d, km Median Attenuation A(f, d), d. B 100 40 30 26 Open 5 area 25 pen io uas Q 20 area 15 rb ubu ea r an a S 10 9 d. B 2 5 1 10 30 850 MHz 850 100 500 Frequency f, MHz 3000 100 200 300 500 700 1000 Frequency f, (MHz) 2000 3000 The Okumura model is based on detailed analysis of exhaustive drive-test measurements made in Tokyo and its suburbs during the late 1960’s and early 1970’s. The collected date included measurements on numerous VHF, UHF, and microwave signal sources, both horizontally and vertically polarized, at a wide range of heights. The measurements were statistically processed analyzed with respect to almost every imaginable variable. This analysis was distilled into the curves above, showing a median attenuation relative to free space loss Amu (f, d) and correlation factor Garea (f, area), for BS antenna height ht = 200 m and MS antenna height hr = 3 m. Okumura has served as the basis for high-level design of many existing wireless systems, and has spawned a number of newer models adapted from its basic concepts and numerical parameters. July, 1998 RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 19

![Structure of the Okumura Model Path Loss [d. B] = LFS + Amu(f, d) Structure of the Okumura Model Path Loss [d. B] = LFS + Amu(f, d)](https://present5.com/presentation/83340717190bde2cb158e791fed96ec2/image-20.jpg) Structure of the Okumura Model Path Loss [d. B] = LFS + Amu(f, d) - G(Hb) - G(Hm) - Garea Base Station Height Gain = 20 x Log (Hb/200) Amu(f, d) Additional Median Loss from Okumura’s Curves Urban Area 100 80 50 70 Mobile Station Height Gain = 10 x Log (Hm/3) 30 Open area 25 Qua pen si o area 20 15 an urb a are Sub 10 5 d, km Median Attenuation A(f, d), d. B 70 35 Correction factor, Garea (d. B) Free-Space Path Loss Morphology Gain 0 dense urban 5 urban 10 suburban 17 rural 850 MHz 40 100 30 26 200 300 500 700 1000 2000 3000 Frequency f, (MHz) 5 2 1 10 Frequency f, MHz 100 500 850 3000 n The Okumura Model uses a combination of terms from basic physical mechanisms and arbitrary factors to fit 1960 -1970 Tokyo drive test data n Later researchers (HATA, COST 231, others) have expressed Okumura’s curves as formulas and automated the computation July, 1998 RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 20

Structure of the Okumura Model Path Loss [d. B] = LFS + Amu(f, d) - G(Hb) - G(Hm) - Garea Base Station Height Gain = 20 x Log (Hb/200) Amu(f, d) Additional Median Loss from Okumura’s Curves Urban Area 100 80 50 70 Mobile Station Height Gain = 10 x Log (Hm/3) 30 Open area 25 Qua pen si o area 20 15 an urb a are Sub 10 5 d, km Median Attenuation A(f, d), d. B 70 35 Correction factor, Garea (d. B) Free-Space Path Loss Morphology Gain 0 dense urban 5 urban 10 suburban 17 rural 850 MHz 40 100 30 26 200 300 500 700 1000 2000 3000 Frequency f, (MHz) 5 2 1 10 Frequency f, MHz 100 500 850 3000 n The Okumura Model uses a combination of terms from basic physical mechanisms and arbitrary factors to fit 1960 -1970 Tokyo drive test data n Later researchers (HATA, COST 231, others) have expressed Okumura’s curves as formulas and automated the computation July, 1998 RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 20

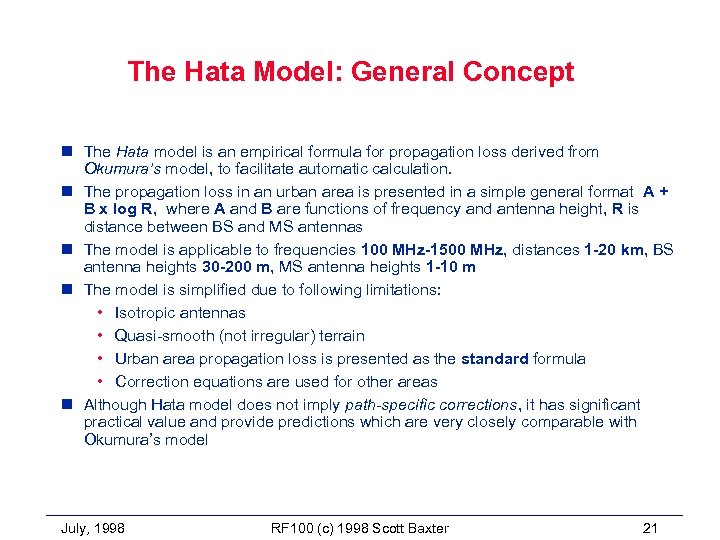

The Hata Model: General Concept n The Hata model is an empirical formula for propagation loss derived from Okumura’s model, to facilitate automatic calculation. n The propagation loss in an urban area is presented in a simple general format A + B x log R, where A and B are functions of frequency and antenna height, R is distance between BS and MS antennas n The model is applicable to frequencies 100 MHz-1500 MHz, distances 1 -20 km, BS antenna heights 30 -200 m, MS antenna heights 1 -10 m n The model is simplified due to following limitations: • Isotropic antennas • Quasi-smooth (not irregular) terrain • Urban area propagation loss is presented as the standard formula • Correction equations are used for other areas n Although Hata model does not imply path-specific corrections, it has significant practical value and provide predictions which are very closely comparable with Okumura’s model July, 1998 RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 21

The Hata Model: General Concept n The Hata model is an empirical formula for propagation loss derived from Okumura’s model, to facilitate automatic calculation. n The propagation loss in an urban area is presented in a simple general format A + B x log R, where A and B are functions of frequency and antenna height, R is distance between BS and MS antennas n The model is applicable to frequencies 100 MHz-1500 MHz, distances 1 -20 km, BS antenna heights 30 -200 m, MS antenna heights 1 -10 m n The model is simplified due to following limitations: • Isotropic antennas • Quasi-smooth (not irregular) terrain • Urban area propagation loss is presented as the standard formula • Correction equations are used for other areas n Although Hata model does not imply path-specific corrections, it has significant practical value and provide predictions which are very closely comparable with Okumura’s model July, 1998 RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 21

![Hata Model General Concept and Formulas (1) LHATA (urban) [d. B] =69. 55 + Hata Model General Concept and Formulas (1) LHATA (urban) [d. B] =69. 55 +](https://present5.com/presentation/83340717190bde2cb158e791fed96ec2/image-22.jpg) Hata Model General Concept and Formulas (1) LHATA (urban) [d. B] =69. 55 + 26. 16 x log ( f ) + [ 44. 9 - 6. 55 x log ( hb ) ] x log ( d ) 13. 82 x log ( hb ) - A ( hm ) (2) LHATA (suburban) [d. B] = LHATA (urban) - 2 x [ log ( f/28 ) ]2 - 5. 4 (3) LHATA (rural) [d. B] =LHATA (urban) - 4. 78 x [ log ( f ) ]2 - 18. 33 x log ( f ) -40. 98 (4) A ( hm ) [d. B] = [ 11 x log ( f ) - 0. 7 ] x hm - [ 1. 56 x log ( f ) - 0. 8 ] (5) A ( hm ) [d. B] = 8. 29 x [ log ( 1. 54 x hm ) ]2 - 1. 1 (for f<= 300 MHz. ) (6) A ( hm ) [d. B] = 3. 2 x [ log ( 1175 x hm ) ]2 - 4. 97 (for f > 300 MHz. ) Formulas for median path loss are: (1) - Standard formula for urban areas (2) - For suburban areas (3) - For rural areas Formulas for MS antenna ht. gain correction factor A(hm) (4) - For a small to medium sizes cities (5) and (6) - For large cities July, 1998 f - carrier frequency, MHz hb and hm - BS and MS antenna heights, m d - distance between BS and MS antennas, km Environmental Factor C 0 dense urban -5 urban -10 suburban -17 rural RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 22

Hata Model General Concept and Formulas (1) LHATA (urban) [d. B] =69. 55 + 26. 16 x log ( f ) + [ 44. 9 - 6. 55 x log ( hb ) ] x log ( d ) 13. 82 x log ( hb ) - A ( hm ) (2) LHATA (suburban) [d. B] = LHATA (urban) - 2 x [ log ( f/28 ) ]2 - 5. 4 (3) LHATA (rural) [d. B] =LHATA (urban) - 4. 78 x [ log ( f ) ]2 - 18. 33 x log ( f ) -40. 98 (4) A ( hm ) [d. B] = [ 11 x log ( f ) - 0. 7 ] x hm - [ 1. 56 x log ( f ) - 0. 8 ] (5) A ( hm ) [d. B] = 8. 29 x [ log ( 1. 54 x hm ) ]2 - 1. 1 (for f<= 300 MHz. ) (6) A ( hm ) [d. B] = 3. 2 x [ log ( 1175 x hm ) ]2 - 4. 97 (for f > 300 MHz. ) Formulas for median path loss are: (1) - Standard formula for urban areas (2) - For suburban areas (3) - For rural areas Formulas for MS antenna ht. gain correction factor A(hm) (4) - For a small to medium sizes cities (5) and (6) - For large cities July, 1998 f - carrier frequency, MHz hb and hm - BS and MS antenna heights, m d - distance between BS and MS antennas, km Environmental Factor C 0 dense urban -5 urban -10 suburban -17 rural RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 22

![The EURO COST-231 Model LCOST (urban) [d. B] = 46. 3 + 33. 9 The EURO COST-231 Model LCOST (urban) [d. B] = 46. 3 + 33. 9](https://present5.com/presentation/83340717190bde2cb158e791fed96ec2/image-23.jpg) The EURO COST-231 Model LCOST (urban) [d. B] = 46. 3 + 33. 9 x log ( f ) + [ 44. 9 - 6. 55 x log ( hb ) ] x log ( d ) + Cm -13. 82 x log ( hb ) - A ( hm ) The COST-231 model was developed by European COoperative for Scientific and Technical Research committee. It extends the HATA model to the 1. 8 -2 GHz. band in anticipation of PCS use. n COST-231 is applicable for frequencies 1500 -2000 MHz, distances 1 -20 km, BS antenna heights 30 -200 m, MS antenna heights 1 -10 m n Parameters and variables: • f is carrier frequency , in MHz • hb and hm are BS and MS antenna heights (m) • d is BS and MS separation, in km • A(hm) is MS antenna height correction factor (same as in Hata model) • Cm is city size correction factor: Cm=0 d. B for suburbs and Cm=3 d. B for metropolitan centers July, 1998 RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter Environmental Factor C 1900 -2 dense urban -5 urban -10 suburban -26 rural 23

The EURO COST-231 Model LCOST (urban) [d. B] = 46. 3 + 33. 9 x log ( f ) + [ 44. 9 - 6. 55 x log ( hb ) ] x log ( d ) + Cm -13. 82 x log ( hb ) - A ( hm ) The COST-231 model was developed by European COoperative for Scientific and Technical Research committee. It extends the HATA model to the 1. 8 -2 GHz. band in anticipation of PCS use. n COST-231 is applicable for frequencies 1500 -2000 MHz, distances 1 -20 km, BS antenna heights 30 -200 m, MS antenna heights 1 -10 m n Parameters and variables: • f is carrier frequency , in MHz • hb and hm are BS and MS antenna heights (m) • d is BS and MS separation, in km • A(hm) is MS antenna height correction factor (same as in Hata model) • Cm is city size correction factor: Cm=0 d. B for suburbs and Cm=3 d. B for metropolitan centers July, 1998 RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter Environmental Factor C 1900 -2 dense urban -5 urban -10 suburban -26 rural 23

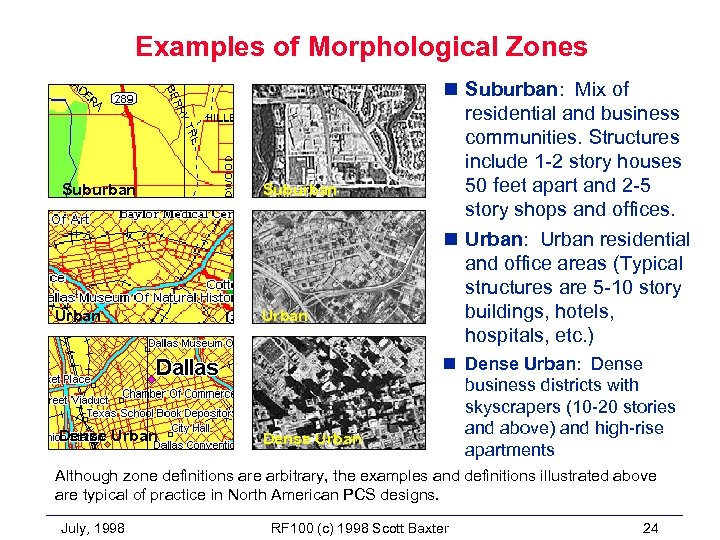

Examples of Morphological Zones Suburban Urban Dense Urban n Suburban: Mix of residential and business communities. Structures include 1 -2 story houses 50 feet apart and 2 -5 story shops and offices. n Urban: Urban residential and office areas (Typical structures are 5 -10 story buildings, hotels, hospitals, etc. ) n Dense Urban: Dense business districts with skyscrapers (10 -20 stories and above) and high-rise apartments Although zone definitions are arbitrary, the examples and definitions illustrated above are typical of practice in North American PCS designs. July, 1998 RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 24

Examples of Morphological Zones Suburban Urban Dense Urban n Suburban: Mix of residential and business communities. Structures include 1 -2 story houses 50 feet apart and 2 -5 story shops and offices. n Urban: Urban residential and office areas (Typical structures are 5 -10 story buildings, hotels, hospitals, etc. ) n Dense Urban: Dense business districts with skyscrapers (10 -20 stories and above) and high-rise apartments Although zone definitions are arbitrary, the examples and definitions illustrated above are typical of practice in North American PCS designs. July, 1998 RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 24

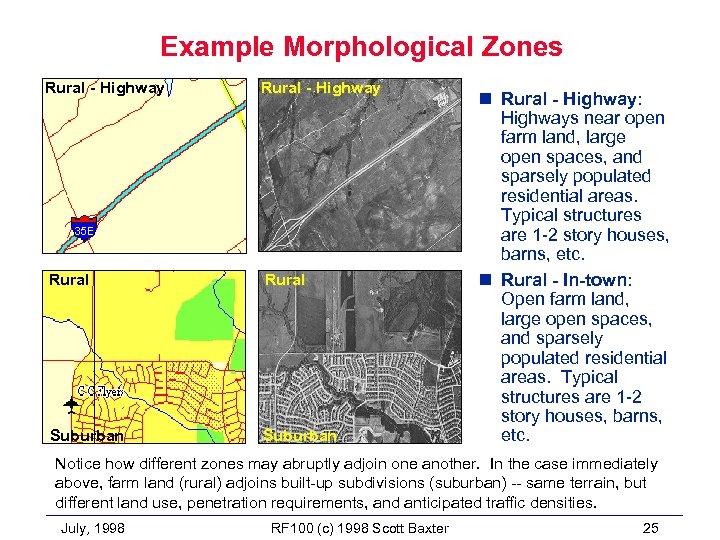

Example Morphological Zones Rural - Highway Rural Suburban n Rural - Highway: Highways near open farm land, large open spaces, and sparsely populated residential areas. Typical structures are 1 -2 story houses, barns, etc. n Rural - In-town: Open farm land, large open spaces, and sparsely populated residential areas. Typical structures are 1 -2 story houses, barns, etc. Notice how different zones may abruptly adjoin one another. In the case immediately above, farm land (rural) adjoins built-up subdivisions (suburban) -- same terrain, but different land use, penetration requirements, and anticipated traffic densities. July, 1998 RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 25

Example Morphological Zones Rural - Highway Rural Suburban n Rural - Highway: Highways near open farm land, large open spaces, and sparsely populated residential areas. Typical structures are 1 -2 story houses, barns, etc. n Rural - In-town: Open farm land, large open spaces, and sparsely populated residential areas. Typical structures are 1 -2 story houses, barns, etc. Notice how different zones may abruptly adjoin one another. In the case immediately above, farm land (rural) adjoins built-up subdivisions (suburban) -- same terrain, but different land use, penetration requirements, and anticipated traffic densities. July, 1998 RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 25

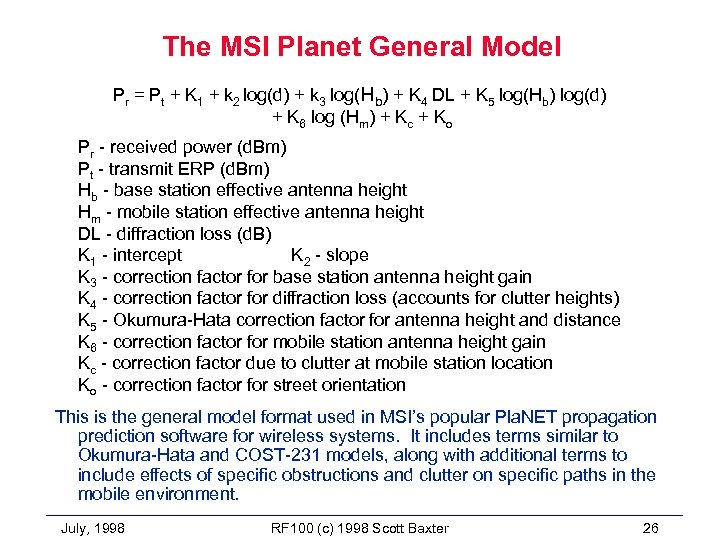

The MSI Planet General Model Pr = Pt + K 1 + k 2 log(d) + k 3 log(Hb) + K 4 DL + K 5 log(Hb) log(d) + K 6 log (Hm) + Kc + Ko Pr - received power (d. Bm) Pt - transmit ERP (d. Bm) Hb - base station effective antenna height Hm - mobile station effective antenna height DL - diffraction loss (d. B) K 1 - intercept K 2 - slope K 3 - correction factor for base station antenna height gain K 4 - correction factor for diffraction loss (accounts for clutter heights) K 5 - Okumura-Hata correction factor for antenna height and distance K 6 - correction factor for mobile station antenna height gain Kc - correction factor due to clutter at mobile station location Ko - correction factor for street orientation This is the general model format used in MSI’s popular Pla. NET propagation prediction software for wireless systems. It includes terms similar to Okumura-Hata and COST-231 models, along with additional terms to include effects of specific obstructions and clutter on specific paths in the mobile environment. July, 1998 RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 26

The MSI Planet General Model Pr = Pt + K 1 + k 2 log(d) + k 3 log(Hb) + K 4 DL + K 5 log(Hb) log(d) + K 6 log (Hm) + Kc + Ko Pr - received power (d. Bm) Pt - transmit ERP (d. Bm) Hb - base station effective antenna height Hm - mobile station effective antenna height DL - diffraction loss (d. B) K 1 - intercept K 2 - slope K 3 - correction factor for base station antenna height gain K 4 - correction factor for diffraction loss (accounts for clutter heights) K 5 - Okumura-Hata correction factor for antenna height and distance K 6 - correction factor for mobile station antenna height gain Kc - correction factor due to clutter at mobile station location Ko - correction factor for street orientation This is the general model format used in MSI’s popular Pla. NET propagation prediction software for wireless systems. It includes terms similar to Okumura-Hata and COST-231 models, along with additional terms to include effects of specific obstructions and clutter on specific paths in the mobile environment. July, 1998 RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 26

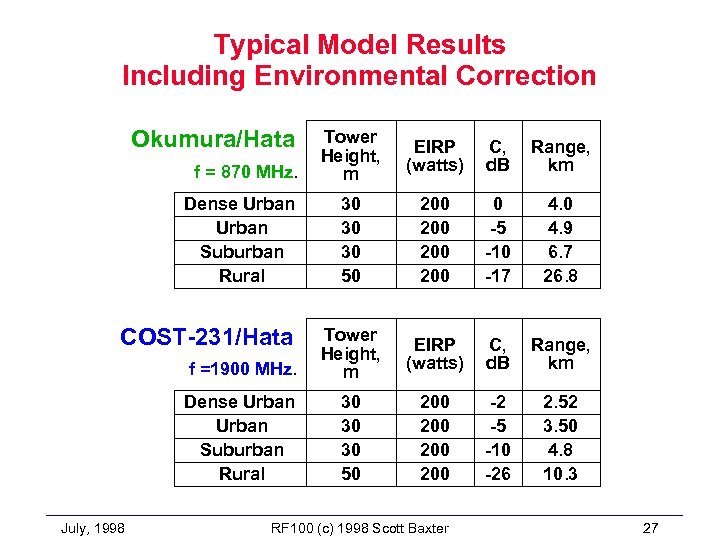

Typical Model Results Including Environmental Correction Okumura/Hata Tower Height, m EIRP (watts) C, d. B Range, km 30 30 30 50 200 200 0 -5 -10 -17 4. 0 4. 9 6. 7 26. 8 f =1900 MHz. Tower Height, m EIRP (watts) C, d. B Range, km Dense Urban Suburban Rural 30 30 30 50 200 200 -2 -5 -10 -26 2. 52 3. 50 4. 8 10. 3 f = 870 MHz. Dense Urban Suburban Rural COST-231/Hata July, 1998 RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 27

Typical Model Results Including Environmental Correction Okumura/Hata Tower Height, m EIRP (watts) C, d. B Range, km 30 30 30 50 200 200 0 -5 -10 -17 4. 0 4. 9 6. 7 26. 8 f =1900 MHz. Tower Height, m EIRP (watts) C, d. B Range, km Dense Urban Suburban Rural 30 30 30 50 200 200 -2 -5 -10 -26 2. 52 3. 50 4. 8 10. 3 f = 870 MHz. Dense Urban Suburban Rural COST-231/Hata July, 1998 RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 27

Propagation at 1900 MHz. vs. 800 MHz. n Propagation at 1900 MHz. is similar to 800 MHz. , but all effects are more pronounced. • Reflections are more effective • Shadows from obstructions are deeper • Foliage absorption is more attenuative • Penetration into buildings through openings is more effective, but absorbing materials within buildings and their walls attenuate the signal more severely than at 800 MHz. n The net result of all these effects is to increase the “contrast” of hot and cold signal areas throughout a 1900 MHz. system, compared to what would have been obtained at 800 MHz. n Overall, coverage radius of a 1900 MHz. BTS is approximately two -thirds the distance which would be obtained with the same ERP, same antenna height, at 800 MHz. July, 1998 RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 28

Propagation at 1900 MHz. vs. 800 MHz. n Propagation at 1900 MHz. is similar to 800 MHz. , but all effects are more pronounced. • Reflections are more effective • Shadows from obstructions are deeper • Foliage absorption is more attenuative • Penetration into buildings through openings is more effective, but absorbing materials within buildings and their walls attenuate the signal more severely than at 800 MHz. n The net result of all these effects is to increase the “contrast” of hot and cold signal areas throughout a 1900 MHz. system, compared to what would have been obtained at 800 MHz. n Overall, coverage radius of a 1900 MHz. BTS is approximately two -thirds the distance which would be obtained with the same ERP, same antenna height, at 800 MHz. July, 1998 RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 28

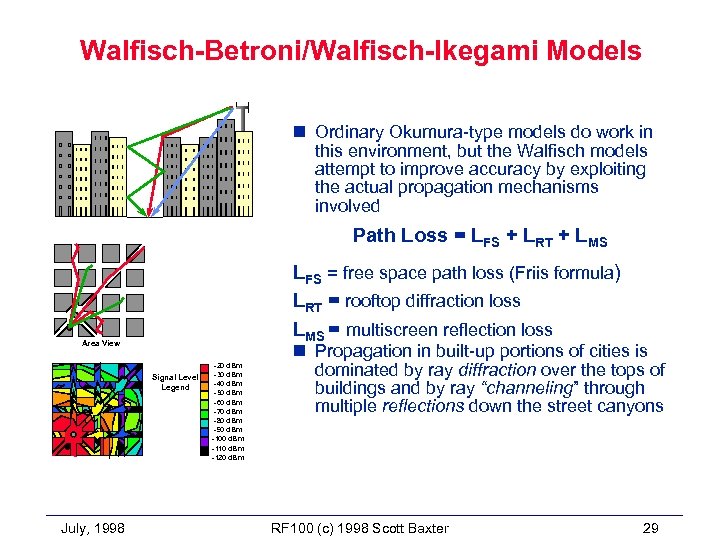

Walfisch-Betroni/Walfisch-Ikegami Models n Ordinary Okumura-type models do work in this environment, but the Walfisch models attempt to improve accuracy by exploiting the actual propagation mechanisms involved Path Loss = LFS + LRT + LMS LFS = free space path loss (Friis formula) LRT = rooftop diffraction loss LMS = multiscreen reflection loss Area View Signal Level Legend July, 1998 -20 d. Bm -30 d. Bm -40 d. Bm -50 d. Bm -60 d. Bm -70 d. Bm -80 d. Bm -90 d. Bm -100 d. Bm -110 d. Bm -120 d. Bm n Propagation in built-up portions of cities is dominated by ray diffraction over the tops of buildings and by ray “channeling” through multiple reflections down the street canyons RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 29

Walfisch-Betroni/Walfisch-Ikegami Models n Ordinary Okumura-type models do work in this environment, but the Walfisch models attempt to improve accuracy by exploiting the actual propagation mechanisms involved Path Loss = LFS + LRT + LMS LFS = free space path loss (Friis formula) LRT = rooftop diffraction loss LMS = multiscreen reflection loss Area View Signal Level Legend July, 1998 -20 d. Bm -30 d. Bm -40 d. Bm -50 d. Bm -60 d. Bm -70 d. Bm -80 d. Bm -90 d. Bm -100 d. Bm -110 d. Bm -120 d. Bm n Propagation in built-up portions of cities is dominated by ray diffraction over the tops of buildings and by ray “channeling” through multiple reflections down the street canyons RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 29

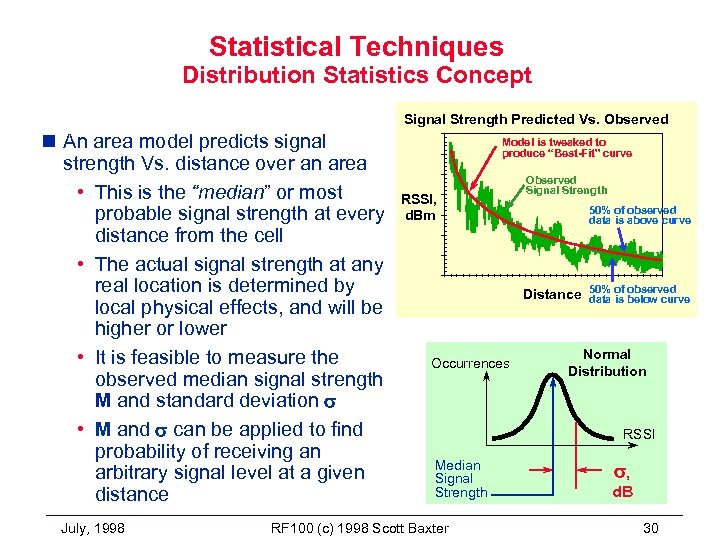

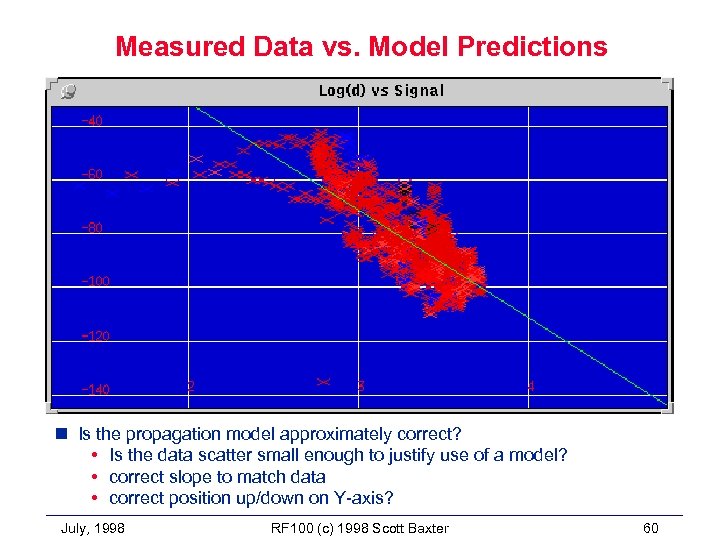

Statistical Techniques Distribution Statistics Concept Signal Strength Predicted Vs. Observed n An area model predicts signal strength Vs. distance over an area • This is the “median” or most probable signal strength at every distance from the cell • The actual signal strength at any real location is determined by local physical effects, and will be higher or lower • It is feasible to measure the observed median signal strength M and standard deviation s • M and s can be applied to find probability of receiving an arbitrary signal level at a given distance July, 1998 Model is tweaked to produce “Best-Fit” curve RSSI, d. Bm Observed Signal Strength 50% of observed data is above curve Distance Occurrences 50% of observed data is below curve Normal Distribution RSSI Median Signal Strength RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter s, d. B 30

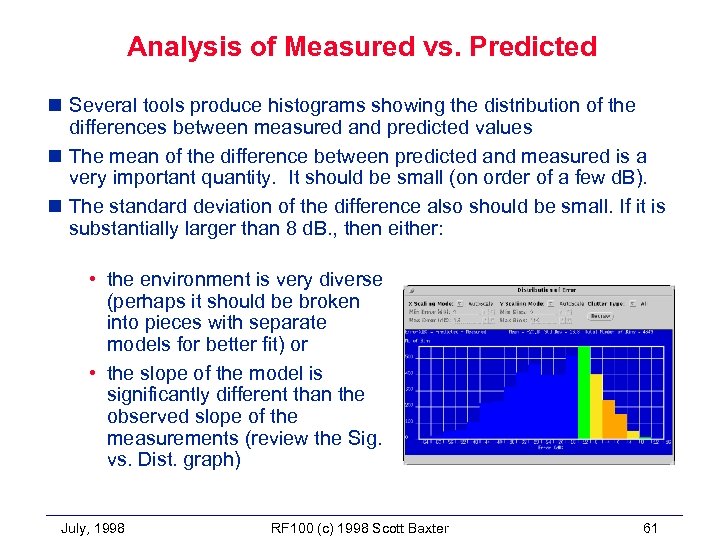

Statistical Techniques Distribution Statistics Concept Signal Strength Predicted Vs. Observed n An area model predicts signal strength Vs. distance over an area • This is the “median” or most probable signal strength at every distance from the cell • The actual signal strength at any real location is determined by local physical effects, and will be higher or lower • It is feasible to measure the observed median signal strength M and standard deviation s • M and s can be applied to find probability of receiving an arbitrary signal level at a given distance July, 1998 Model is tweaked to produce “Best-Fit” curve RSSI, d. Bm Observed Signal Strength 50% of observed data is above curve Distance Occurrences 50% of observed data is below curve Normal Distribution RSSI Median Signal Strength RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter s, d. B 30

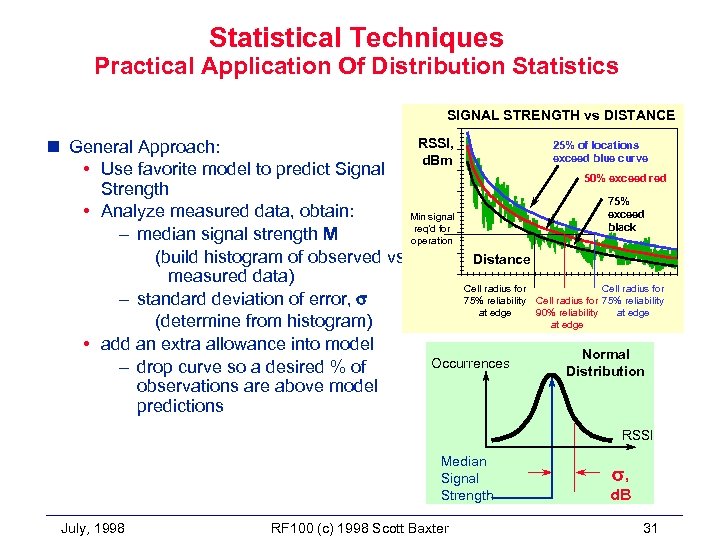

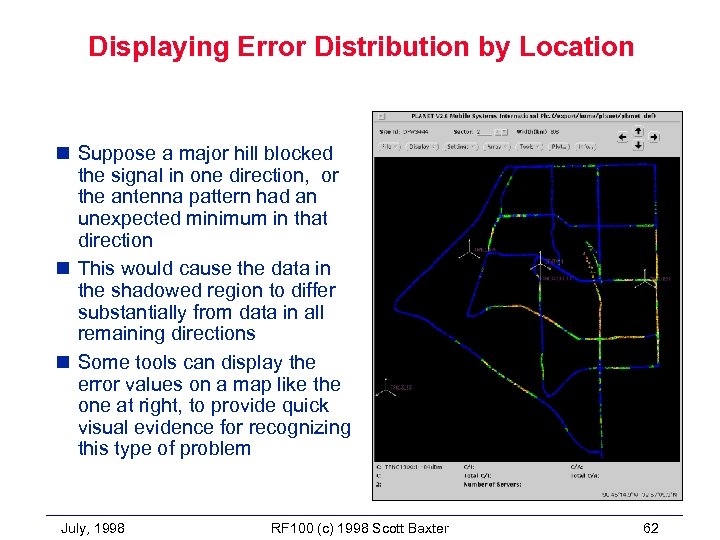

Statistical Techniques Practical Application Of Distribution Statistics SIGNAL STRENGTH vs DISTANCE RSSI, 25% of locations n General Approach: exceed blue curve d. Bm • Use favorite model to predict Signal 50% exceed red Strength 75% • Analyze measured data, obtain: exceed Min signal black req’d for – median signal strength M operation (build histogram of observed vs. Distance measured data) Cell radius for 75% reliability – standard deviation of error, s at edge 90% reliability (determine from histogram) at edge • add an extra allowance into model Normal Occurrences – drop curve so a desired % of Distribution observations are above model predictions RSSI Median Signal Strength July, 1998 RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter s, d. B 31

Statistical Techniques Practical Application Of Distribution Statistics SIGNAL STRENGTH vs DISTANCE RSSI, 25% of locations n General Approach: exceed blue curve d. Bm • Use favorite model to predict Signal 50% exceed red Strength 75% • Analyze measured data, obtain: exceed Min signal black req’d for – median signal strength M operation (build histogram of observed vs. Distance measured data) Cell radius for 75% reliability – standard deviation of error, s at edge 90% reliability (determine from histogram) at edge • add an extra allowance into model Normal Occurrences – drop curve so a desired % of Distribution observations are above model predictions RSSI Median Signal Strength July, 1998 RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter s, d. B 31

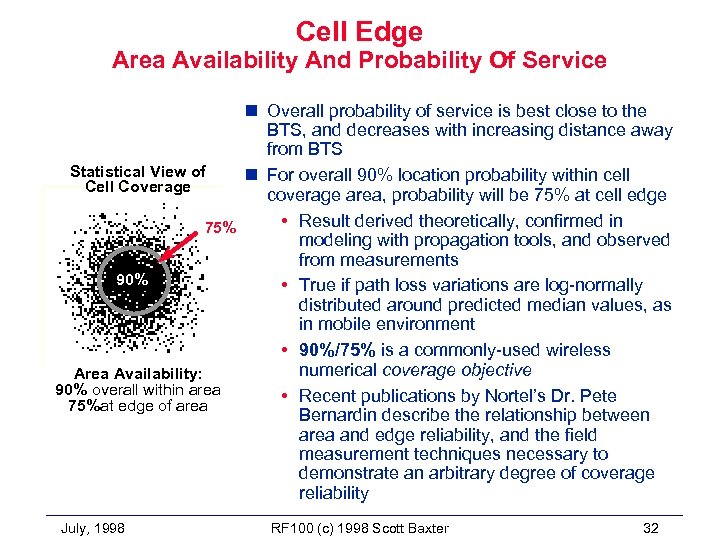

Cell Edge Area Availability And Probability Of Service n Overall probability of service is best close to the BTS, and decreases with increasing distance away from BTS Statistical View of n For overall 90% location probability within cell Coverage coverage area, probability will be 75% at cell edge • Result derived theoretically, confirmed in 75% modeling with propagation tools, and observed from measurements 90% • True if path loss variations are log-normally distributed around predicted median values, as in mobile environment • 90%/75% is a commonly-used wireless numerical coverage objective Area Availability: 90% overall within area • Recent publications by Nortel’s Dr. Pete 75%at edge of area Bernardin describe the relationship between area and edge reliability, and the field measurement techniques necessary to demonstrate an arbitrary degree of coverage reliability July, 1998 RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 32

Cell Edge Area Availability And Probability Of Service n Overall probability of service is best close to the BTS, and decreases with increasing distance away from BTS Statistical View of n For overall 90% location probability within cell Coverage coverage area, probability will be 75% at cell edge • Result derived theoretically, confirmed in 75% modeling with propagation tools, and observed from measurements 90% • True if path loss variations are log-normally distributed around predicted median values, as in mobile environment • 90%/75% is a commonly-used wireless numerical coverage objective Area Availability: 90% overall within area • Recent publications by Nortel’s Dr. Pete 75%at edge of area Bernardin describe the relationship between area and edge reliability, and the field measurement techniques necessary to demonstrate an arbitrary degree of coverage reliability July, 1998 RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 32

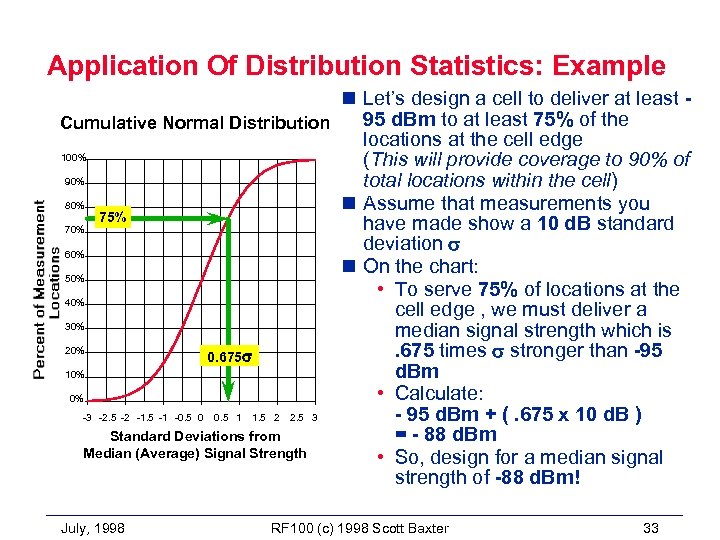

Application Of Distribution Statistics: Example n Let’s design a cell to deliver at least 95 d. Bm to at least 75% of the Cumulative Normal Distribution locations at the cell edge 100% (This will provide coverage to 90% of 90% total locations within the cell) 80% n Assume that measurements you 75% have made show a 10 d. B standard 70% deviation s 60% n On the chart: 50% • To serve 75% of locations at the 40% cell edge , we must deliver a 30% median signal strength which is 20%. 675 times s stronger than -95 0. 675 s d. Bm 10% • Calculate: 0% - 95 d. Bm + (. 675 x 10 d. B ) -3 -2. 5 -2 -1. 5 -1 -0. 5 0 0. 5 1 1. 5 2 2. 5 3 = - 88 d. Bm Standard Deviations from Median (Average) Signal Strength • So, design for a median signal strength of -88 d. Bm! July, 1998 RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 33

Application Of Distribution Statistics: Example n Let’s design a cell to deliver at least 95 d. Bm to at least 75% of the Cumulative Normal Distribution locations at the cell edge 100% (This will provide coverage to 90% of 90% total locations within the cell) 80% n Assume that measurements you 75% have made show a 10 d. B standard 70% deviation s 60% n On the chart: 50% • To serve 75% of locations at the 40% cell edge , we must deliver a 30% median signal strength which is 20%. 675 times s stronger than -95 0. 675 s d. Bm 10% • Calculate: 0% - 95 d. Bm + (. 675 x 10 d. B ) -3 -2. 5 -2 -1. 5 -1 -0. 5 0 0. 5 1 1. 5 2 2. 5 3 = - 88 d. Bm Standard Deviations from Median (Average) Signal Strength • So, design for a median signal strength of -88 d. Bm! July, 1998 RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 33

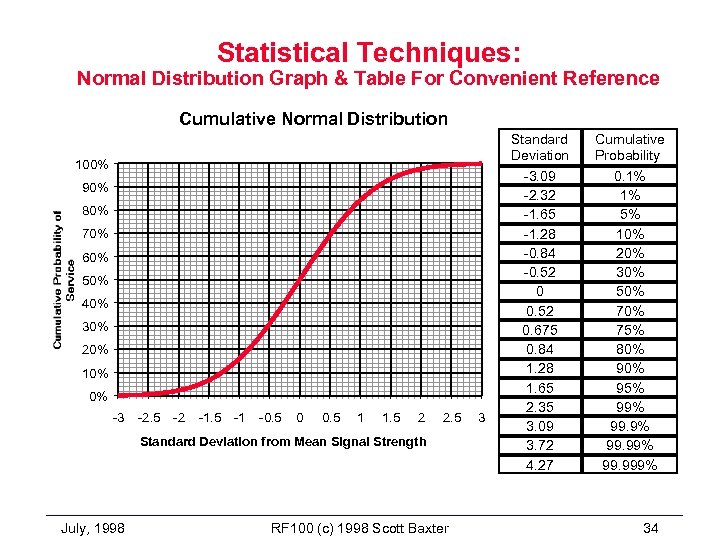

Statistical Techniques: Normal Distribution Graph & Table For Convenient Reference Cumulative Normal Distribution 100% 90% 80% 70% 60% 50% 40% 30% 20% 10% 0% -3 -2. 5 -2 -1. 5 -1 -0. 5 0 0. 5 1 1. 5 2 2. 5 Standard Deviation from Mean Signal Strength July, 1998 RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 3 Standard Deviation -3. 09 -2. 32 -1. 65 -1. 28 -0. 84 -0. 52 0. 675 0. 84 1. 28 1. 65 2. 35 3. 09 3. 72 4. 27 Cumulative Probability 0. 1% 1% 5% 10% 20% 30% 50% 75% 80% 95% 99. 9% 99. 999% 34

Statistical Techniques: Normal Distribution Graph & Table For Convenient Reference Cumulative Normal Distribution 100% 90% 80% 70% 60% 50% 40% 30% 20% 10% 0% -3 -2. 5 -2 -1. 5 -1 -0. 5 0 0. 5 1 1. 5 2 2. 5 Standard Deviation from Mean Signal Strength July, 1998 RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 3 Standard Deviation -3. 09 -2. 32 -1. 65 -1. 28 -0. 84 -0. 52 0. 675 0. 84 1. 28 1. 65 2. 35 3. 09 3. 72 4. 27 Cumulative Probability 0. 1% 1% 5% 10% 20% 30% 50% 75% 80% 95% 99. 9% 99. 999% 34

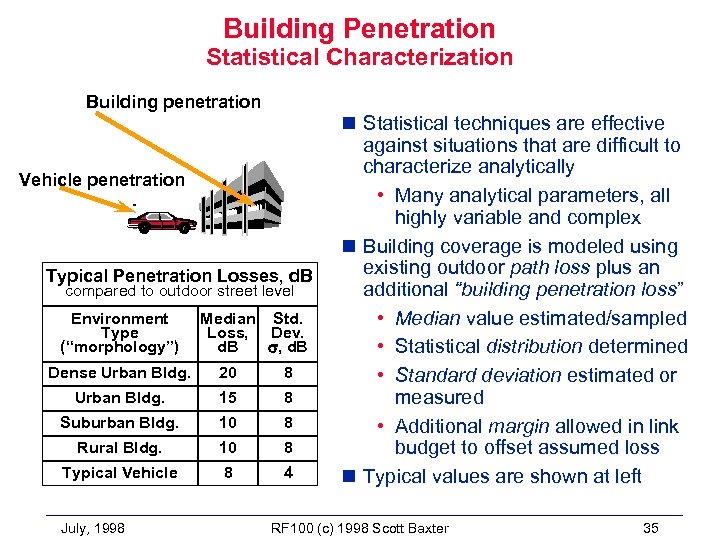

Building Penetration Statistical Characterization Building penetration Vehicle penetration Typical Penetration Losses, d. B compared to outdoor street level Environment Type (“morphology”) Median Std. Loss, Dev. d. B s, d. B Dense Urban Bldg. 20 8 Urban Bldg. 15 8 Suburban Bldg. 10 8 Rural Bldg. 10 8 Typical Vehicle 8 4 July, 1998 n Statistical techniques are effective against situations that are difficult to characterize analytically • Many analytical parameters, all highly variable and complex n Building coverage is modeled using existing outdoor path loss plus an additional “building penetration loss” • Median value estimated/sampled • Statistical distribution determined • Standard deviation estimated or measured • Additional margin allowed in link budget to offset assumed loss n Typical values are shown at left RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 35

Building Penetration Statistical Characterization Building penetration Vehicle penetration Typical Penetration Losses, d. B compared to outdoor street level Environment Type (“morphology”) Median Std. Loss, Dev. d. B s, d. B Dense Urban Bldg. 20 8 Urban Bldg. 15 8 Suburban Bldg. 10 8 Rural Bldg. 10 8 Typical Vehicle 8 4 July, 1998 n Statistical techniques are effective against situations that are difficult to characterize analytically • Many analytical parameters, all highly variable and complex n Building coverage is modeled using existing outdoor path loss plus an additional “building penetration loss” • Median value estimated/sampled • Statistical distribution determined • Standard deviation estimated or measured • Additional margin allowed in link budget to offset assumed loss n Typical values are shown at left RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 35

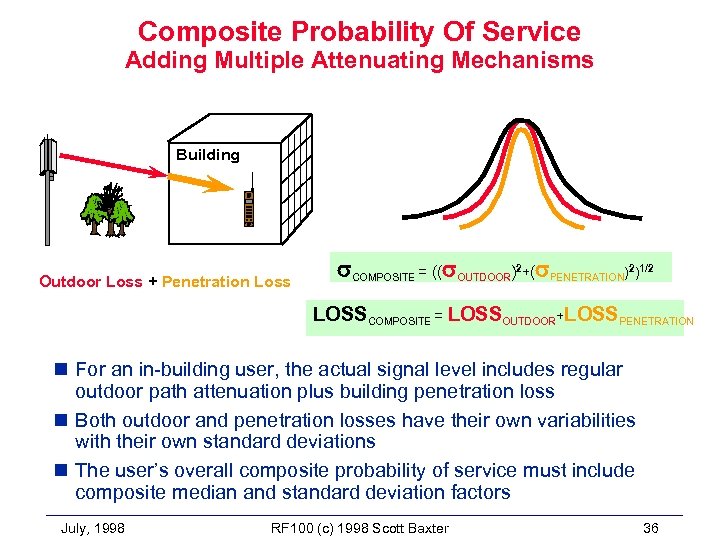

Composite Probability Of Service Adding Multiple Attenuating Mechanisms Building Outdoor Loss + Penetration Loss s. COMPOSITE = ((s. OUTDOOR)2+(s ENETRATION)2)1/2 P LOSSCOMPOSITE = LOSSOUTDOOR+LOSSPENETRATION n For an in-building user, the actual signal level includes regular outdoor path attenuation plus building penetration loss n Both outdoor and penetration losses have their own variabilities with their own standard deviations n The user’s overall composite probability of service must include composite median and standard deviation factors July, 1998 RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 36

Composite Probability Of Service Adding Multiple Attenuating Mechanisms Building Outdoor Loss + Penetration Loss s. COMPOSITE = ((s. OUTDOOR)2+(s ENETRATION)2)1/2 P LOSSCOMPOSITE = LOSSOUTDOOR+LOSSPENETRATION n For an in-building user, the actual signal level includes regular outdoor path attenuation plus building penetration loss n Both outdoor and penetration losses have their own variabilities with their own standard deviations n The user’s overall composite probability of service must include composite median and standard deviation factors July, 1998 RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 36

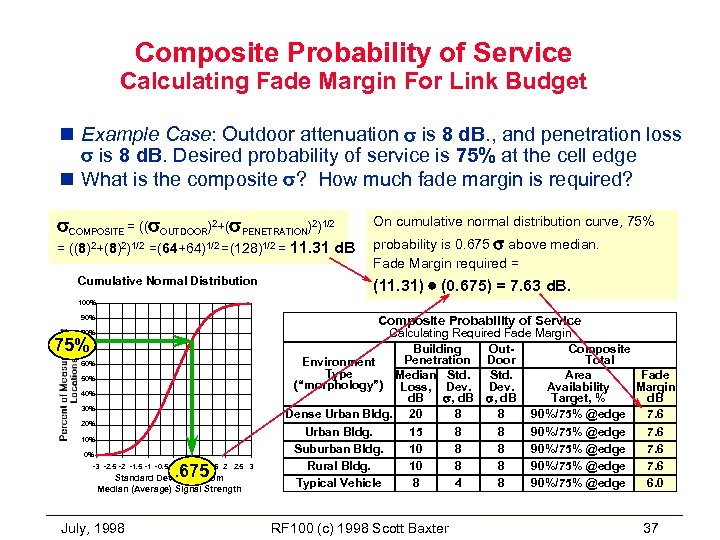

Composite Probability of Service Calculating Fade Margin For Link Budget n Example Case: Outdoor attenuation s is 8 d. B. , and penetration loss s is 8 d. B. Desired probability of service is 75% at the cell edge n What is the composite s? How much fade margin is required? s. COMPOSITE = ((s. OUTDOOR)2+(s. PENETRATION)2)1/2 = ((8)2+(8)2)1/2 =(64+64)1/2 =(128)1/2 = 11. 31 d. B Cumulative Normal Distribution On cumulative normal distribution curve, 75% probability is 0. 675 s above median. Fade Margin required = (11. 31) · (0. 675) = 7. 63 d. B. 100% Composite Probability of Service 90% 80% 75% 70% 60% 50% 40% 30% 20% 10% 0% . 675 -3 -2. 5 -2 -1. 5 -1 -0. 5 0 0. 5 1 1. 5 2 2. 5 3 Standard Deviations from Median (Average) Signal Strength July, 1998 Calculating Required Fade Margin Building Out. Composite Penetration Door Total Environment Type Median Std. Area Fade (“morphology”) Loss, Dev. Availability Margin d. B s, d. B Target, % d. B 90%/75% @edge Dense Urban Bldg. 20 8 8 7. 6 90%/75% @edge Urban Bldg. 15 8 8 7. 6 90%/75% @edge Suburban Bldg. 10 8 8 7. 6 90%/75% @edge Rural Bldg. 10 8 8 7. 6 Typical Vehicle 8 4 8 90%/75% @edge 6. 0 RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 37

Composite Probability of Service Calculating Fade Margin For Link Budget n Example Case: Outdoor attenuation s is 8 d. B. , and penetration loss s is 8 d. B. Desired probability of service is 75% at the cell edge n What is the composite s? How much fade margin is required? s. COMPOSITE = ((s. OUTDOOR)2+(s. PENETRATION)2)1/2 = ((8)2+(8)2)1/2 =(64+64)1/2 =(128)1/2 = 11. 31 d. B Cumulative Normal Distribution On cumulative normal distribution curve, 75% probability is 0. 675 s above median. Fade Margin required = (11. 31) · (0. 675) = 7. 63 d. B. 100% Composite Probability of Service 90% 80% 75% 70% 60% 50% 40% 30% 20% 10% 0% . 675 -3 -2. 5 -2 -1. 5 -1 -0. 5 0 0. 5 1 1. 5 2 2. 5 3 Standard Deviations from Median (Average) Signal Strength July, 1998 Calculating Required Fade Margin Building Out. Composite Penetration Door Total Environment Type Median Std. Area Fade (“morphology”) Loss, Dev. Availability Margin d. B s, d. B Target, % d. B 90%/75% @edge Dense Urban Bldg. 20 8 8 7. 6 90%/75% @edge Urban Bldg. 15 8 8 7. 6 90%/75% @edge Suburban Bldg. 10 8 8 7. 6 90%/75% @edge Rural Bldg. 10 8 8 7. 6 Typical Vehicle 8 4 8 90%/75% @edge 6. 0 RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 37

Chapter 4 Section C Commercial Propagation Prediction Software July, 1998 RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 38

Chapter 4 Section C Commercial Propagation Prediction Software July, 1998 RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 38

Point-To-Point Path-Driven Prediction Models n Use of models based on deterministic methods • Use of terrain data for construction of path profile • Path analysis (ray tracing) for obstruction, reflection analysis • Appropriate algorithms applied for best emulation of underlying physics • May include some statistical techniques • Automated point-to-point analysis for enough points to appear to provide large “area” coverage on raster or radial grid n Commonly-used Resources • • • Terrain databases Morphological/Clutter Databases of existing and proposed sites Antenna characteristics databases Unique user-defined propagation models July, 1998 RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 39

Point-To-Point Path-Driven Prediction Models n Use of models based on deterministic methods • Use of terrain data for construction of path profile • Path analysis (ray tracing) for obstruction, reflection analysis • Appropriate algorithms applied for best emulation of underlying physics • May include some statistical techniques • Automated point-to-point analysis for enough points to appear to provide large “area” coverage on raster or radial grid n Commonly-used Resources • • • Terrain databases Morphological/Clutter Databases of existing and proposed sites Antenna characteristics databases Unique user-defined propagation models July, 1998 RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 39

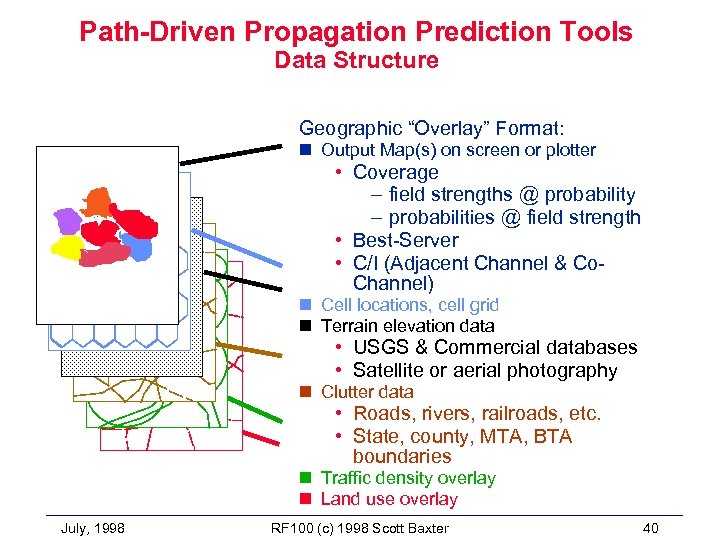

Path-Driven Propagation Prediction Tools Data Structure Geographic “Overlay” Format: n Output Map(s) on screen or plotter • Coverage – field strengths @ probability – probabilities @ field strength • Best-Server • C/I (Adjacent Channel & Co. Channel) n Cell locations, cell grid n Terrain elevation data • USGS & Commercial databases • Satellite or aerial photography n Clutter data • Roads, rivers, railroads, etc. • State, county, MTA, BTA boundaries n Traffic density overlay n Land use overlay July, 1998 RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 40

Path-Driven Propagation Prediction Tools Data Structure Geographic “Overlay” Format: n Output Map(s) on screen or plotter • Coverage – field strengths @ probability – probabilities @ field strength • Best-Server • C/I (Adjacent Channel & Co. Channel) n Cell locations, cell grid n Terrain elevation data • USGS & Commercial databases • Satellite or aerial photography n Clutter data • Roads, rivers, railroads, etc. • State, county, MTA, BTA boundaries n Traffic density overlay n Land use overlay July, 1998 RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 40

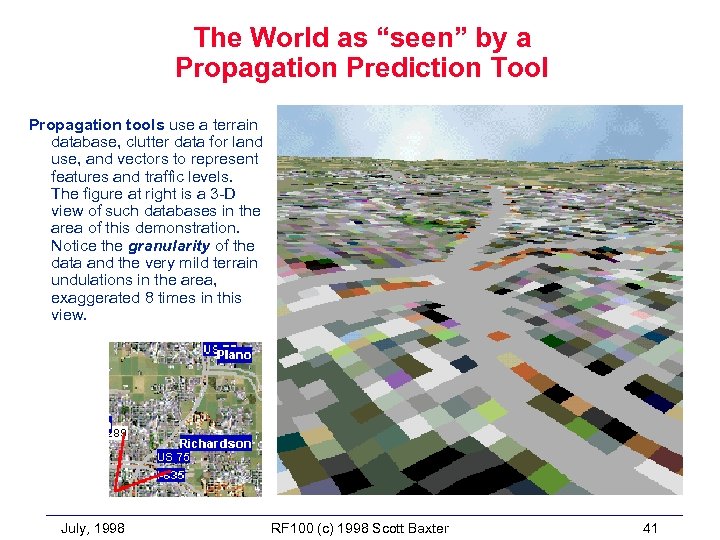

The World as “seen” by a Propagation Prediction Tool Propagation tools use a terrain database, clutter data for land use, and vectors to represent features and traffic levels. The figure at right is a 3 -D view of such databases in the area of this demonstration. Notice the granularity of the data and the very mild terrain undulations in the area, exaggerated 8 times in this view. July, 1998 RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 41

The World as “seen” by a Propagation Prediction Tool Propagation tools use a terrain database, clutter data for land use, and vectors to represent features and traffic levels. The figure at right is a 3 -D view of such databases in the area of this demonstration. Notice the granularity of the data and the very mild terrain undulations in the area, exaggerated 8 times in this view. July, 1998 RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 41

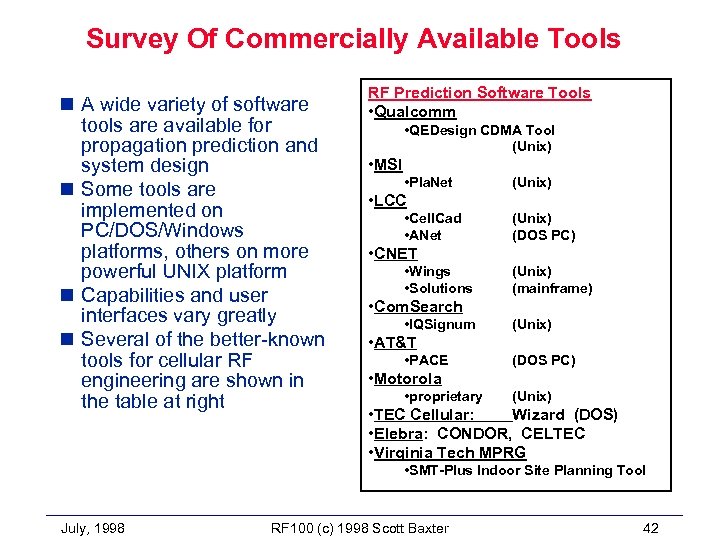

Survey Of Commercially Available Tools n A wide variety of software tools are available for propagation prediction and system design n Some tools are implemented on PC/DOS/Windows platforms, others on more powerful UNIX platform n Capabilities and user interfaces vary greatly n Several of the better-known tools for cellular RF engineering are shown in the table at right RF Prediction Software Tools • Qualcomm • QEDesign CDMA Tool (Unix) • MSI • Pla. Net (Unix) • LCC • Cell. Cad • ANet (Unix) (DOS PC) • CNET • Wings • Solutions (Unix) (mainframe) • Com. Search • IQSignum (Unix) • AT&T • PACE (DOS PC) • Motorola • proprietary (Unix) • TEC Cellular: Wizard (DOS) • Elebra: CONDOR, CELTEC • Virginia Tech MPRG • SMT-Plus Indoor Site Planning Tool July, 1998 RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 42

Survey Of Commercially Available Tools n A wide variety of software tools are available for propagation prediction and system design n Some tools are implemented on PC/DOS/Windows platforms, others on more powerful UNIX platform n Capabilities and user interfaces vary greatly n Several of the better-known tools for cellular RF engineering are shown in the table at right RF Prediction Software Tools • Qualcomm • QEDesign CDMA Tool (Unix) • MSI • Pla. Net (Unix) • LCC • Cell. Cad • ANet (Unix) (DOS PC) • CNET • Wings • Solutions (Unix) (mainframe) • Com. Search • IQSignum (Unix) • AT&T • PACE (DOS PC) • Motorola • proprietary (Unix) • TEC Cellular: Wizard (DOS) • Elebra: CONDOR, CELTEC • Virginia Tech MPRG • SMT-Plus Indoor Site Planning Tool July, 1998 RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 42

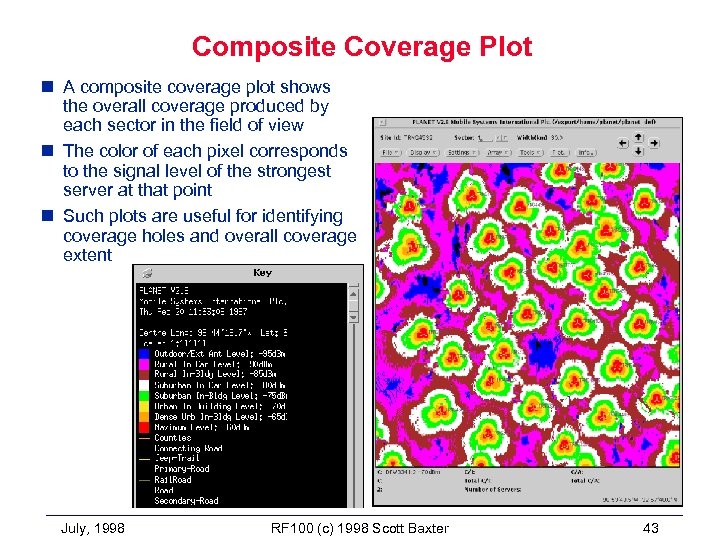

Composite Coverage Plot n A composite coverage plot shows the overall coverage produced by each sector in the field of view n The color of each pixel corresponds to the signal level of the strongest server at that point n Such plots are useful for identifying coverage holes and overall coverage extent July, 1998 RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 43

Composite Coverage Plot n A composite coverage plot shows the overall coverage produced by each sector in the field of view n The color of each pixel corresponds to the signal level of the strongest server at that point n Such plots are useful for identifying coverage holes and overall coverage extent July, 1998 RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 43

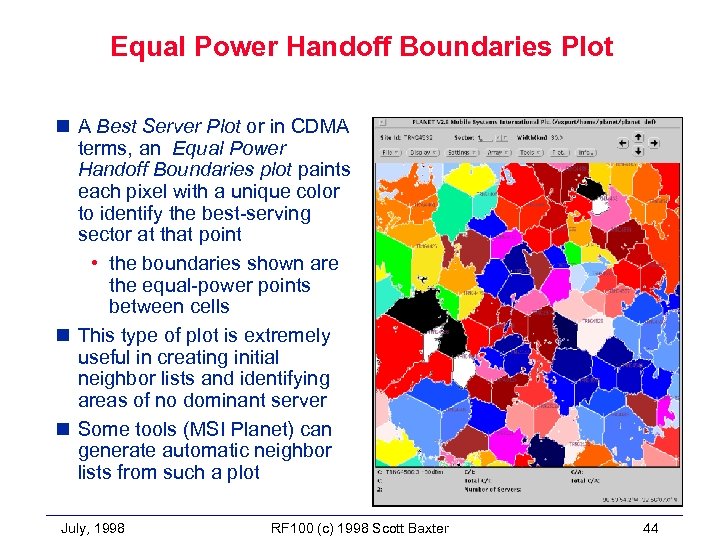

Equal Power Handoff Boundaries Plot n A Best Server Plot or in CDMA terms, an Equal Power Handoff Boundaries plot paints each pixel with a unique color to identify the best-serving sector at that point • the boundaries shown are the equal-power points between cells n This type of plot is extremely useful in creating initial neighbor lists and identifying areas of no dominant server n Some tools (MSI Planet) can generate automatic neighbor lists from such a plot July, 1998 RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 44

Equal Power Handoff Boundaries Plot n A Best Server Plot or in CDMA terms, an Equal Power Handoff Boundaries plot paints each pixel with a unique color to identify the best-serving sector at that point • the boundaries shown are the equal-power points between cells n This type of plot is extremely useful in creating initial neighbor lists and identifying areas of no dominant server n Some tools (MSI Planet) can generate automatic neighbor lists from such a plot July, 1998 RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 44

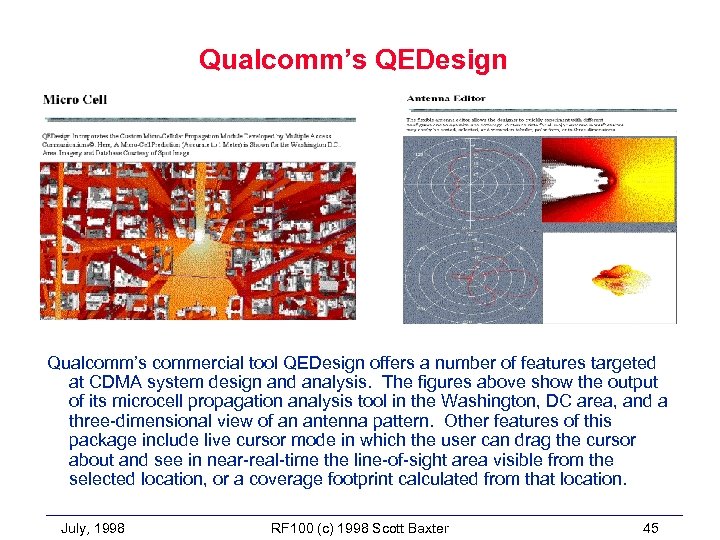

Qualcomm’s QEDesign Qualcomm’s commercial tool QEDesign offers a number of features targeted at CDMA system design and analysis. The figures above show the output of its microcell propagation analysis tool in the Washington, DC area, and a three-dimensional view of an antenna pattern. Other features of this package include live cursor mode in which the user can drag the cursor about and see in near-real-time the line-of-sight area visible from the selected location, or a coverage footprint calculated from that location. July, 1998 RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 45

Qualcomm’s QEDesign Qualcomm’s commercial tool QEDesign offers a number of features targeted at CDMA system design and analysis. The figures above show the output of its microcell propagation analysis tool in the Washington, DC area, and a three-dimensional view of an antenna pattern. Other features of this package include live cursor mode in which the user can drag the cursor about and see in near-real-time the line-of-sight area visible from the selected location, or a coverage footprint calculated from that location. July, 1998 RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 45

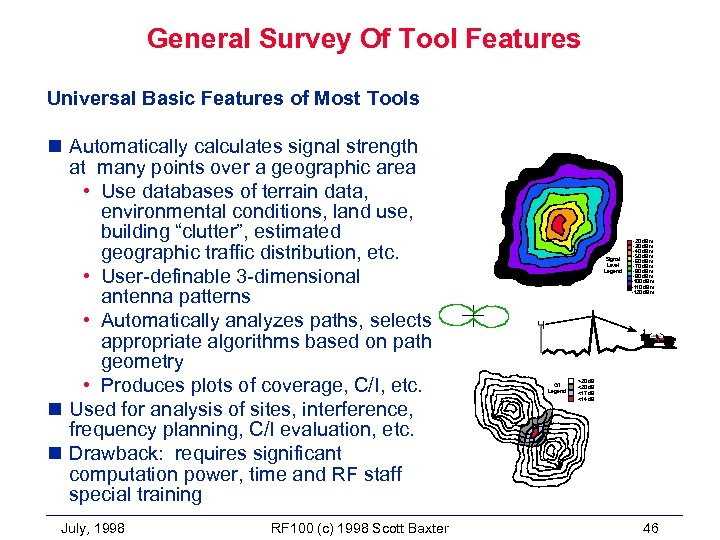

General Survey Of Tool Features Universal Basic Features of Most Tools n Automatically calculates signal strength at many points over a geographic area • Use databases of terrain data, environmental conditions, land use, building “clutter”, estimated geographic traffic distribution, etc. • User-definable 3 -dimensional antenna patterns • Automatically analyzes paths, selects appropriate algorithms based on path geometry • Produces plots of coverage, C/I, etc. n Used for analysis of sites, interference, frequency planning, C/I evaluation, etc. n Drawback: requires significant computation power, time and RF staff special training July, 1998 RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter Signal Level Legend C/I Legend -20 d. Bm -30 d. Bm -40 d. Bm -50 d. Bm -60 d. Bm -70 d. Bm -80 d. Bm -90 d. Bm -100 d. Bm -110 d. Bm -120 d. Bm >20 d. B <17 d. B <14 d. B 46

General Survey Of Tool Features Universal Basic Features of Most Tools n Automatically calculates signal strength at many points over a geographic area • Use databases of terrain data, environmental conditions, land use, building “clutter”, estimated geographic traffic distribution, etc. • User-definable 3 -dimensional antenna patterns • Automatically analyzes paths, selects appropriate algorithms based on path geometry • Produces plots of coverage, C/I, etc. n Used for analysis of sites, interference, frequency planning, C/I evaluation, etc. n Drawback: requires significant computation power, time and RF staff special training July, 1998 RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter Signal Level Legend C/I Legend -20 d. Bm -30 d. Bm -40 d. Bm -50 d. Bm -60 d. Bm -70 d. Bm -80 d. Bm -90 d. Bm -100 d. Bm -110 d. Bm -120 d. Bm >20 d. B <17 d. B <14 d. B 46

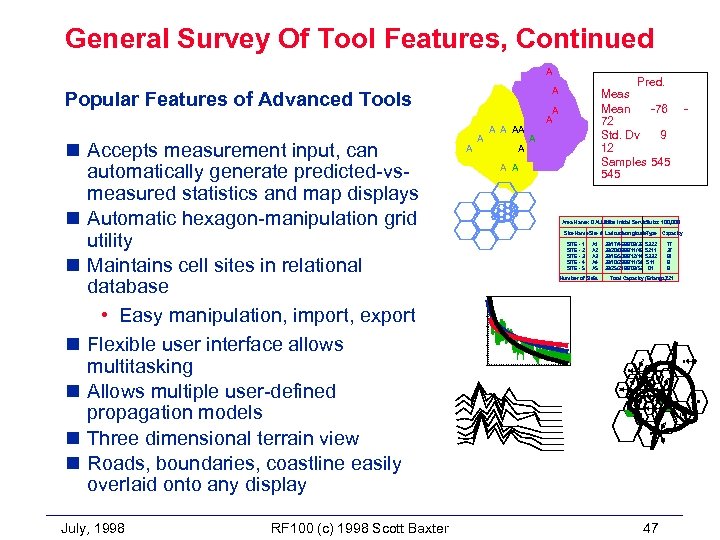

General Survey Of Tool Features, Continued A Popular Features of Advanced Tools n Accepts measurement input, can automatically generate predicted-vsmeasured statistics and map displays n Automatic hexagon-manipulation grid utility n Maintains cell sites in relational database • Easy manipulation, import, export n Flexible user interface allows multitasking n Allows multiple user-defined propagation models n Three dimensional terrain view n Roads, boundaries, coastline easily overlaid onto any display July, 1998 RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter Pred. Meas Mean -76 72 Std. Dv 9 12 Samples 545 A A AA A A A - Area Name: DALLAS Initial Service Date: Subs: 100, 000 Site Name Site # Latitude Longitude. Type Capacity SITE - 1 SITE - 2 SITE - 3 SITE - 4 SITE - 5 A 1 A 2 A 3 A 4 A 5 Number of Sites 5 33/17/4696/08/33 33/20/0896/11/49 33/16/5096/12/14 33/10/2896/11/51 33/25/2196/03/53 S 322 S 211 S 332 S 11 01 77 37 91 8 8 Total Capacity (Erlangs) 21 2 7 9 6 1 3 2 2 4 8 7 1 8 9 6 7 9 5 10 3 11 2 8 4 6 47

General Survey Of Tool Features, Continued A Popular Features of Advanced Tools n Accepts measurement input, can automatically generate predicted-vsmeasured statistics and map displays n Automatic hexagon-manipulation grid utility n Maintains cell sites in relational database • Easy manipulation, import, export n Flexible user interface allows multitasking n Allows multiple user-defined propagation models n Three dimensional terrain view n Roads, boundaries, coastline easily overlaid onto any display July, 1998 RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter Pred. Meas Mean -76 72 Std. Dv 9 12 Samples 545 A A AA A A A - Area Name: DALLAS Initial Service Date: Subs: 100, 000 Site Name Site # Latitude Longitude. Type Capacity SITE - 1 SITE - 2 SITE - 3 SITE - 4 SITE - 5 A 1 A 2 A 3 A 4 A 5 Number of Sites 5 33/17/4696/08/33 33/20/0896/11/49 33/16/5096/12/14 33/10/2896/11/51 33/25/2196/03/53 S 322 S 211 S 332 S 11 01 77 37 91 8 8 Total Capacity (Erlangs) 21 2 7 9 6 1 3 2 2 4 8 7 1 8 9 6 7 9 5 10 3 11 2 8 4 6 47

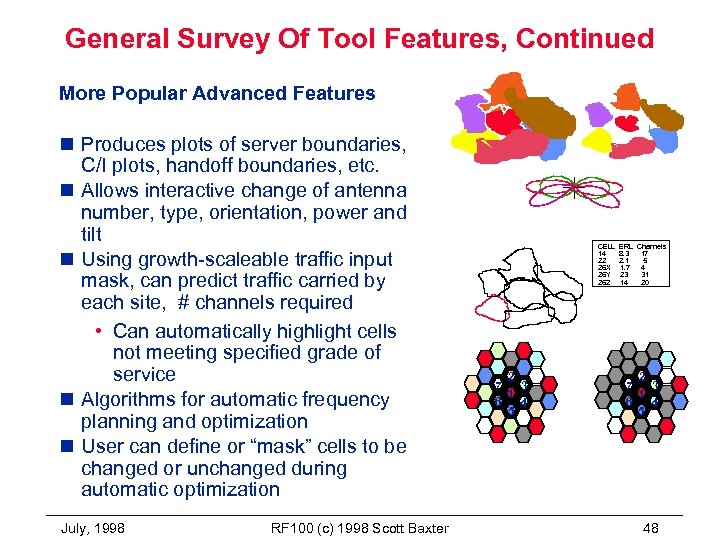

General Survey Of Tool Features, Continued More Popular Advanced Features n Produces plots of server boundaries, C/I plots, handoff boundaries, etc. n Allows interactive change of antenna number, type, orientation, power and tilt n Using growth-scaleable traffic input mask, can predict traffic carried by each site, # channels required • Can automatically highlight cells not meeting specified grade of service n Algorithms for automatic frequency planning and optimization n User can define or “mask” cells to be changed or unchanged during automatic optimization July, 1998 RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter CELL 14 22 26 X 26 Y 26 Z 2 3 7 1 6 4 5 ERL Channels 8. 3 17 2. 1 5 1. 7 4 23 31 14 20 2 3 7 1 6 4 5 48

General Survey Of Tool Features, Continued More Popular Advanced Features n Produces plots of server boundaries, C/I plots, handoff boundaries, etc. n Allows interactive change of antenna number, type, orientation, power and tilt n Using growth-scaleable traffic input mask, can predict traffic carried by each site, # channels required • Can automatically highlight cells not meeting specified grade of service n Algorithms for automatic frequency planning and optimization n User can define or “mask” cells to be changed or unchanged during automatic optimization July, 1998 RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter CELL 14 22 26 X 26 Y 26 Z 2 3 7 1 6 4 5 ERL Channels 8. 3 17 2. 1 5 1. 7 4 23 31 14 20 2 3 7 1 6 4 5 48

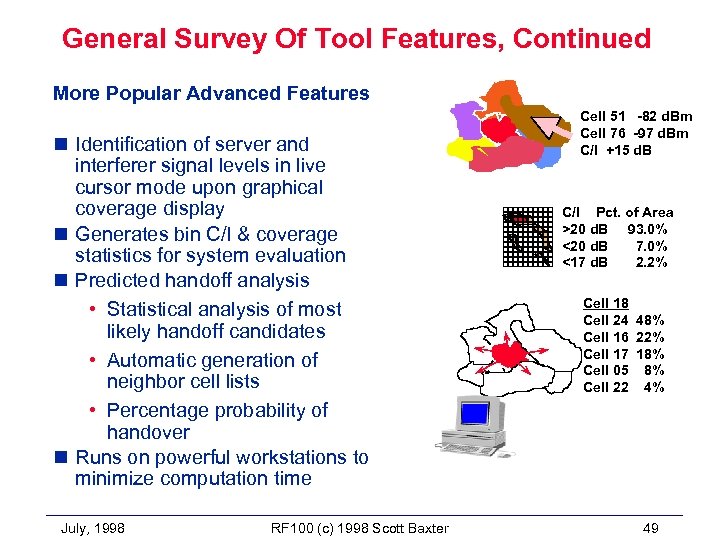

General Survey Of Tool Features, Continued More Popular Advanced Features n Identification of server and interferer signal levels in live cursor mode upon graphical coverage display n Generates bin C/I & coverage statistics for system evaluation n Predicted handoff analysis • Statistical analysis of most likely handoff candidates • Automatic generation of neighbor cell lists • Percentage probability of handover n Runs on powerful workstations to minimize computation time July, 1998 RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter Cell 51 -82 d. Bm Cell 76 -97 d. Bm C/I +15 d. B C/I Pct. of Area >20 d. B 93. 0% <20 d. B 7. 0% <17 d. B 2. 2% Cell 18 Cell 24 48% Cell 16 22% Cell 17 18% Cell 05 8% Cell 22 4% 49

General Survey Of Tool Features, Continued More Popular Advanced Features n Identification of server and interferer signal levels in live cursor mode upon graphical coverage display n Generates bin C/I & coverage statistics for system evaluation n Predicted handoff analysis • Statistical analysis of most likely handoff candidates • Automatic generation of neighbor cell lists • Percentage probability of handover n Runs on powerful workstations to minimize computation time July, 1998 RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter Cell 51 -82 d. Bm Cell 76 -97 d. Bm C/I +15 d. B C/I Pct. of Area >20 d. B 93. 0% <20 d. B 7. 0% <17 d. B 2. 2% Cell 18 Cell 24 48% Cell 16 22% Cell 17 18% Cell 05 8% Cell 22 4% 49

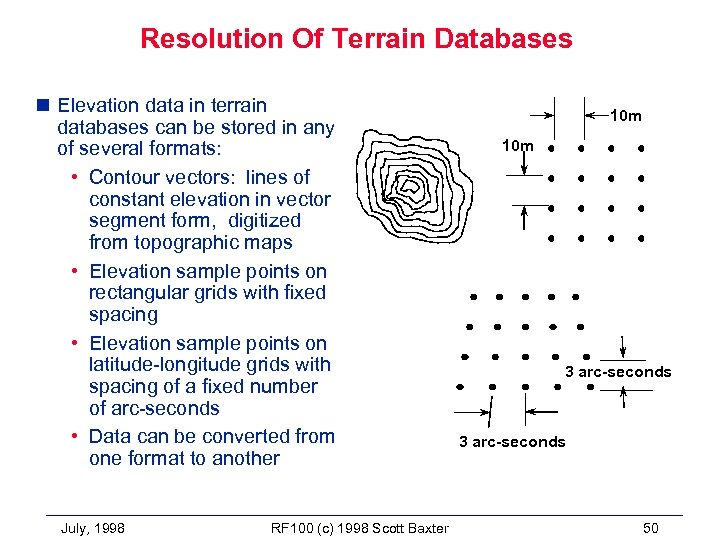

Resolution Of Terrain Databases n Elevation data in terrain databases can be stored in any of several formats: • Contour vectors: lines of constant elevation in vector segment form, digitized from topographic maps • Elevation sample points on rectangular grids with fixed spacing • Elevation sample points on latitude-longitude grids with spacing of a fixed number of arc-seconds • Data can be converted from one format to another July, 1998 RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 10 m 3 arc-seconds 50

Resolution Of Terrain Databases n Elevation data in terrain databases can be stored in any of several formats: • Contour vectors: lines of constant elevation in vector segment form, digitized from topographic maps • Elevation sample points on rectangular grids with fixed spacing • Elevation sample points on latitude-longitude grids with spacing of a fixed number of arc-seconds • Data can be converted from one format to another July, 1998 RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 10 m 3 arc-seconds 50

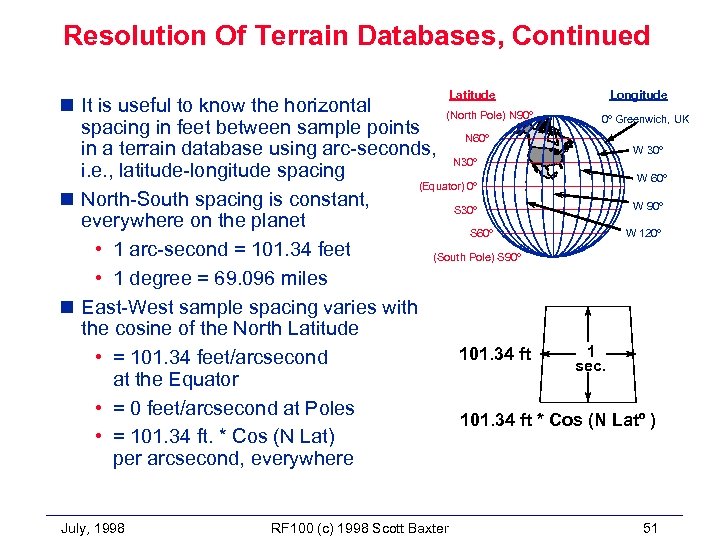

Resolution Of Terrain Databases, Continued Latitude Longitude n It is useful to know the horizontal (North Pole) N 90º 0º Greenwich, UK spacing in feet between sample points N 60º W 30º in a terrain database using arc-seconds, N 30º i. e. , latitude-longitude spacing W 60º (Equator) 0º n North-South spacing is constant, W 90º S 30º everywhere on the planet S 60º W 120º • 1 arc-second = 101. 34 feet (South Pole) S 90º • 1 degree = 69. 096 miles n East-West sample spacing varies with the cosine of the North Latitude 1 101. 34 ft • = 101. 34 feet/arcsecond sec. at the Equator • = 0 feet/arcsecond at Poles 101. 34 ft * Cos (N Latº ) • = 101. 34 ft. * Cos (N Lat) per arcsecond, everywhere July, 1998 RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 51

Resolution Of Terrain Databases, Continued Latitude Longitude n It is useful to know the horizontal (North Pole) N 90º 0º Greenwich, UK spacing in feet between sample points N 60º W 30º in a terrain database using arc-seconds, N 30º i. e. , latitude-longitude spacing W 60º (Equator) 0º n North-South spacing is constant, W 90º S 30º everywhere on the planet S 60º W 120º • 1 arc-second = 101. 34 feet (South Pole) S 90º • 1 degree = 69. 096 miles n East-West sample spacing varies with the cosine of the North Latitude 1 101. 34 ft • = 101. 34 feet/arcsecond sec. at the Equator • = 0 feet/arcsecond at Poles 101. 34 ft * Cos (N Latº ) • = 101. 34 ft. * Cos (N Lat) per arcsecond, everywhere July, 1998 RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 51

Chapter 4 Section D Commercial Measurement Tools July, 1998 RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 52

Chapter 4 Section D Commercial Measurement Tools July, 1998 RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 52

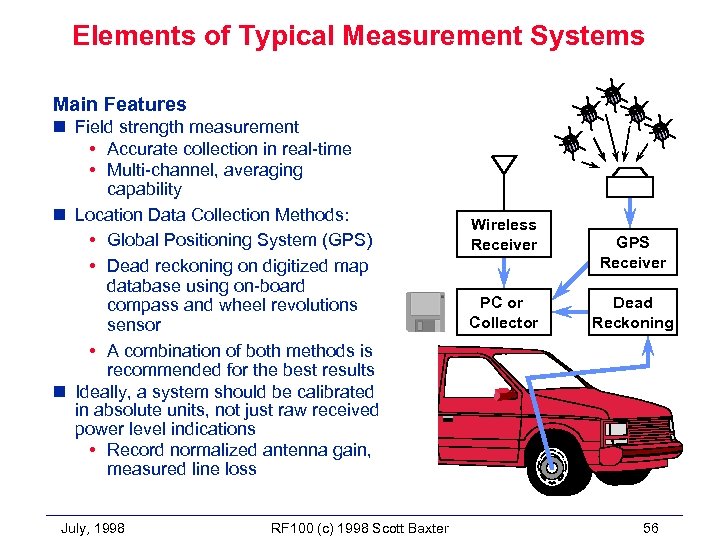

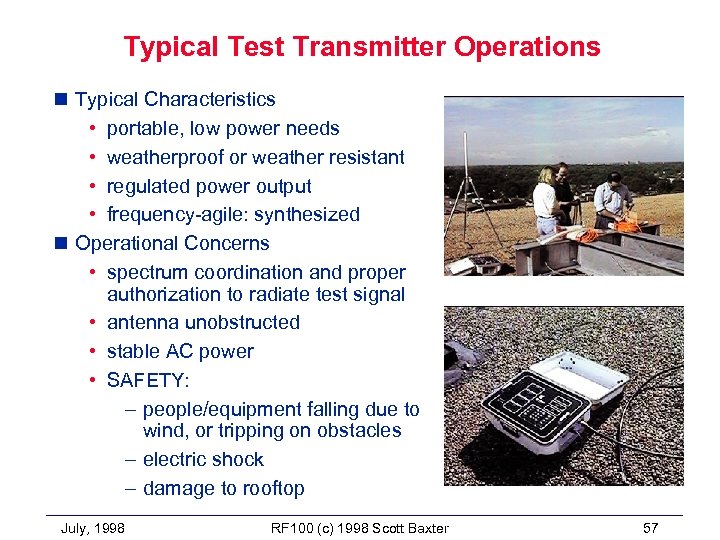

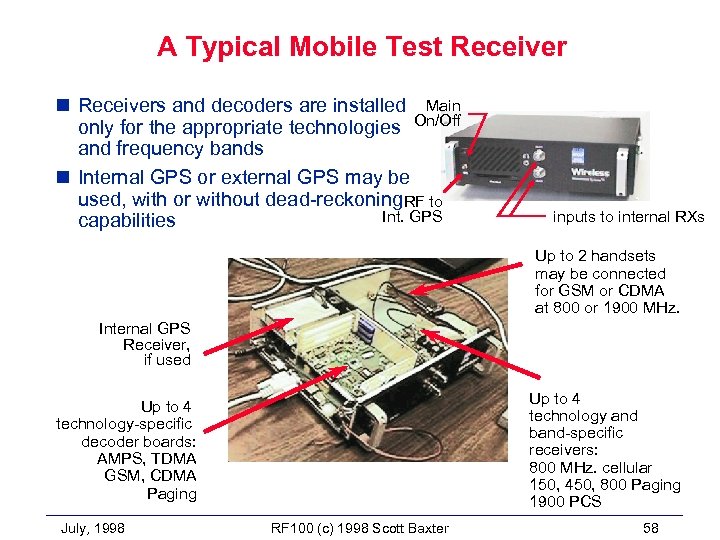

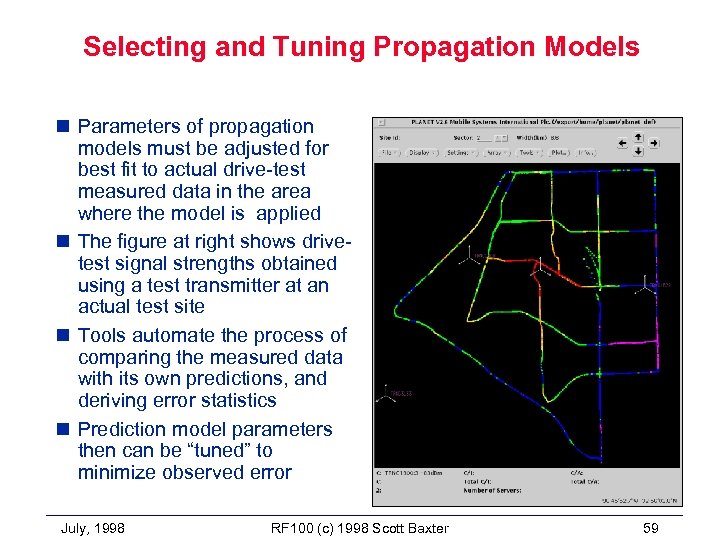

Propagation Data Collection Philosophy n RF testing of sites is usually performed for one of two reasons: n Drive Testing for model calibration • Prior to cell design of a wireless system, accurate models of propagation in the area must be developed for use by the prediction software. A significant number of typical sites are evaluated using the test transmitter and receiver to determine signal decay rates and to get a fairly accurate understanding of the effects of typical clutter in the area. • Tests are also conducted to evaluate the additional attenuation which the signal suffers during penetration of typical buildings and vehicles. • The focus is on developing models generally applicable to the area, not on the performance of specific individual sites. n Drive Testing for site evaluation • Although propagation models for an area already have been refined, coverage of a particular site is so critical, or its environment so variable due to urban clutter, that it is essential to actually measure the coverage and interference it will produce. The focus is on this specific site. July, 1998 RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 53

Propagation Data Collection Philosophy n RF testing of sites is usually performed for one of two reasons: n Drive Testing for model calibration • Prior to cell design of a wireless system, accurate models of propagation in the area must be developed for use by the prediction software. A significant number of typical sites are evaluated using the test transmitter and receiver to determine signal decay rates and to get a fairly accurate understanding of the effects of typical clutter in the area. • Tests are also conducted to evaluate the additional attenuation which the signal suffers during penetration of typical buildings and vehicles. • The focus is on developing models generally applicable to the area, not on the performance of specific individual sites. n Drive Testing for site evaluation • Although propagation models for an area already have been refined, coverage of a particular site is so critical, or its environment so variable due to urban clutter, that it is essential to actually measure the coverage and interference it will produce. The focus is on this specific site. July, 1998 RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 53

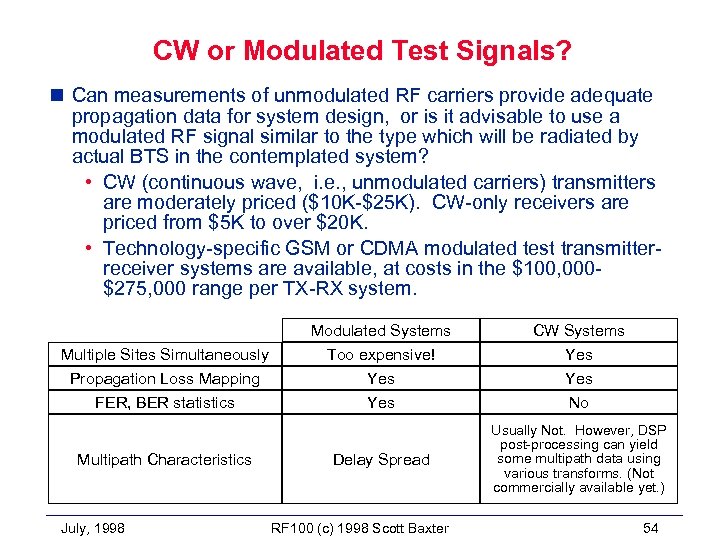

CW or Modulated Test Signals? n Can measurements of unmodulated RF carriers provide adequate propagation data for system design, or is it advisable to use a modulated RF signal similar to the type which will be radiated by actual BTS in the contemplated system? • CW (continuous wave, i. e. , unmodulated carriers) transmitters are moderately priced ($10 K-$25 K). CW-only receivers are priced from $5 K to over $20 K. • Technology-specific GSM or CDMA modulated test transmitterreceiver systems are available, at costs in the $100, 000$275, 000 range per TX-RX system. Multiple Sites Simultaneously Propagation Loss Mapping FER, BER statistics Multipath Characteristics July, 1998 Modulated Systems Too expensive! Yes CW Systems Yes No Delay Spread Usually Not. However, DSP post-processing can yield some multipath data using various transforms. (Not commercially available yet. ) RF 100 (c) 1998 Scott Baxter 54