Копия functional_hierarhy_lect_fin.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 130

Chapter 4 Anatomy of the Nervous System

Chapter 4 Anatomy of the Nervous System

Structure of the Vertebrate Nervous System • Neuroanatomy is the anatomy of the nervous system. • Refers to the study of the various parts of the nervous system and their respective function(s). • The nervous system consists of many substructures, each comprised of many neurons.

Structure of the Vertebrate Nervous System • Neuroanatomy is the anatomy of the nervous system. • Refers to the study of the various parts of the nervous system and their respective function(s). • The nervous system consists of many substructures, each comprised of many neurons.

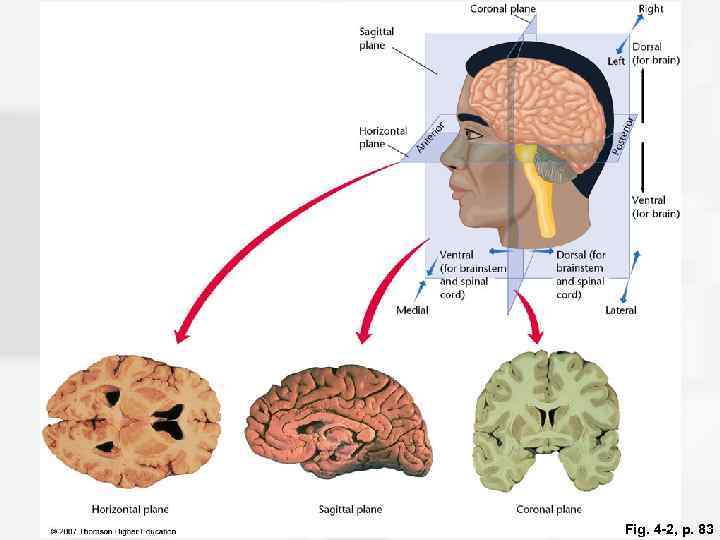

Structure of the Vertebrate Nervous System • Terms used to describe location when referring to the nervous system include: – Ventral: toward the stomach – Dorsal: toward the back – Anterior: toward the front end – Posterior: toward the back end – Lateral: toward the side – Medial: toward the midline

Structure of the Vertebrate Nervous System • Terms used to describe location when referring to the nervous system include: – Ventral: toward the stomach – Dorsal: toward the back – Anterior: toward the front end – Posterior: toward the back end – Lateral: toward the side – Medial: toward the midline

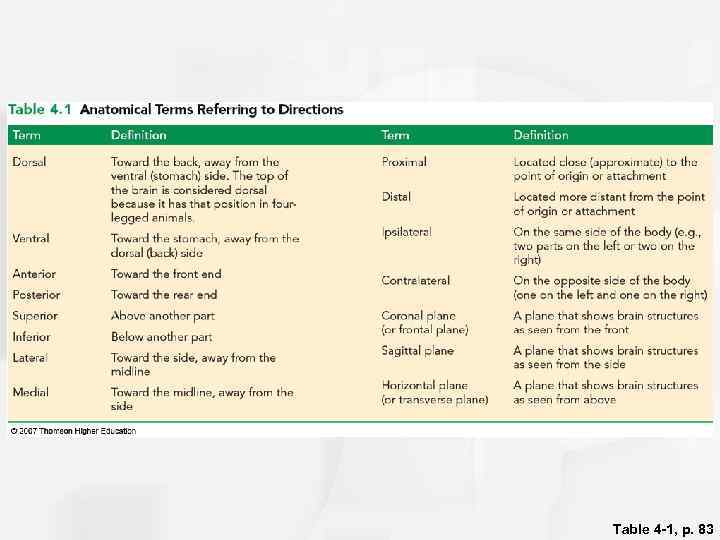

Table 4 -1, p. 83

Table 4 -1, p. 83

Fig. 4 -2, p. 83

Fig. 4 -2, p. 83

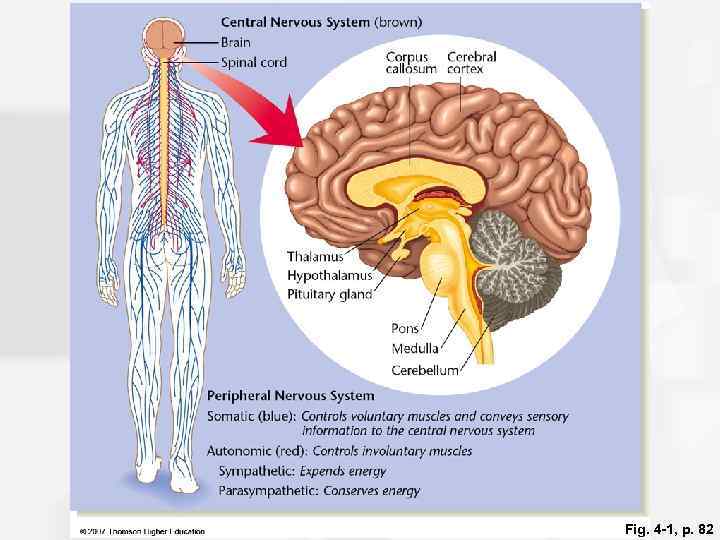

Structure of the Vertebrate Nervous System • The Nervous System is comprised of two major subsystems: 1. The Central Nervous System (CNS) 2. The Peripheral Nervous System (PNS)

Structure of the Vertebrate Nervous System • The Nervous System is comprised of two major subsystems: 1. The Central Nervous System (CNS) 2. The Peripheral Nervous System (PNS)

Fig. 4 -1, p. 82

Fig. 4 -1, p. 82

Structure of the Vertebrate Nervous System • The Central Nervous System consists of: 1. Brain 2. Spinal Chord

Structure of the Vertebrate Nervous System • The Central Nervous System consists of: 1. Brain 2. Spinal Chord

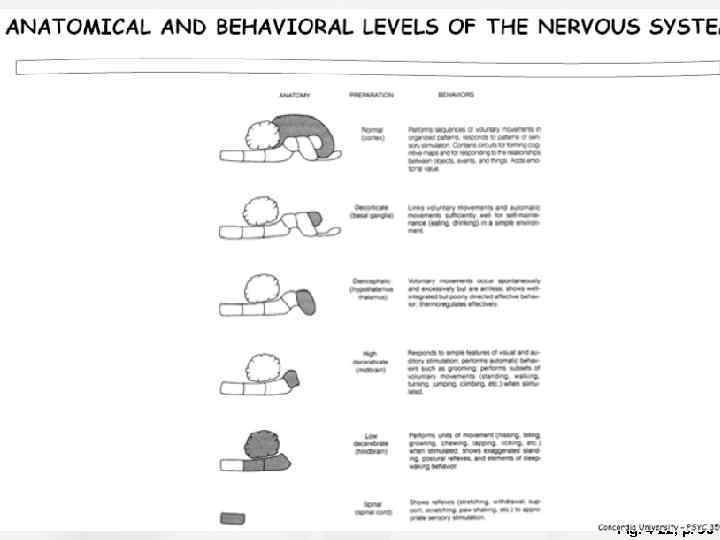

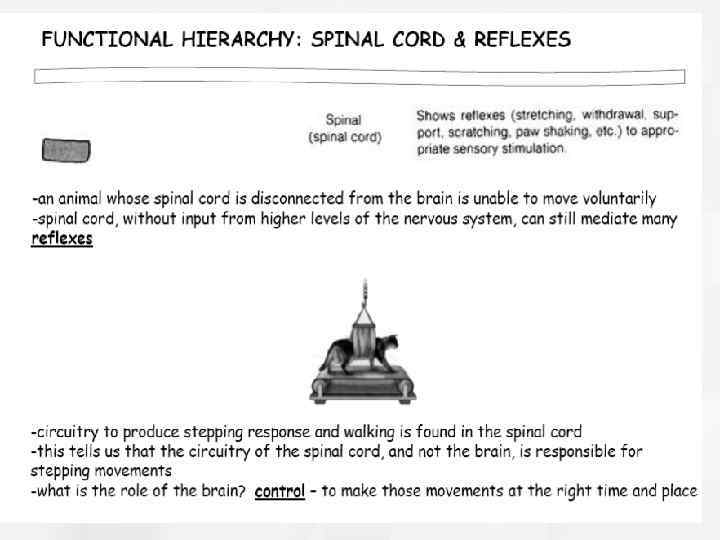

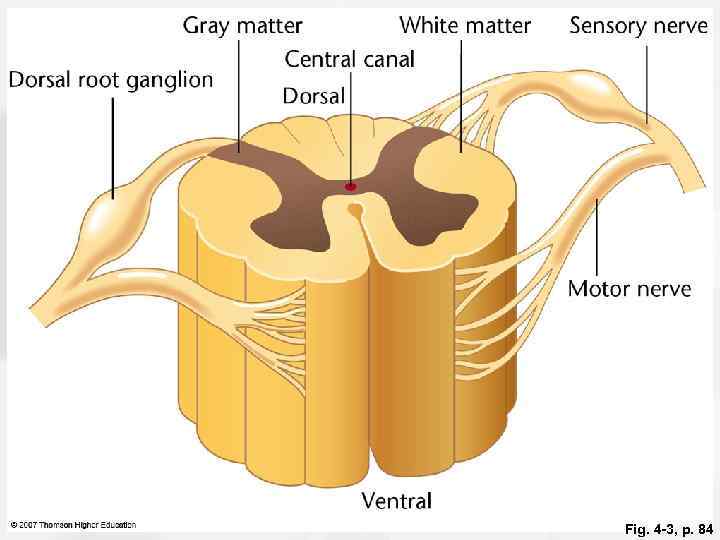

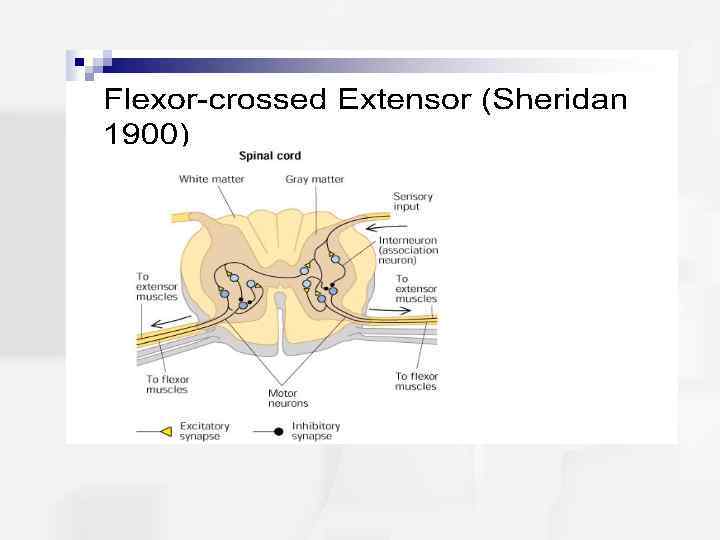

Structure of the Vertebrate Nervous System § The spinal cord is the part of the CNS found within the spinal column and communicates with the sense organs and muscles below the level of the head. § The Bell-Magendie law states the entering dorsal roots carry sensory information and the exiting ventral roots carry motor information. § The cell bodies of the sensory neurons are located in clusters of neurons outside the spinal cord called dorsal root ganglia.

Structure of the Vertebrate Nervous System § The spinal cord is the part of the CNS found within the spinal column and communicates with the sense organs and muscles below the level of the head. § The Bell-Magendie law states the entering dorsal roots carry sensory information and the exiting ventral roots carry motor information. § The cell bodies of the sensory neurons are located in clusters of neurons outside the spinal cord called dorsal root ganglia.

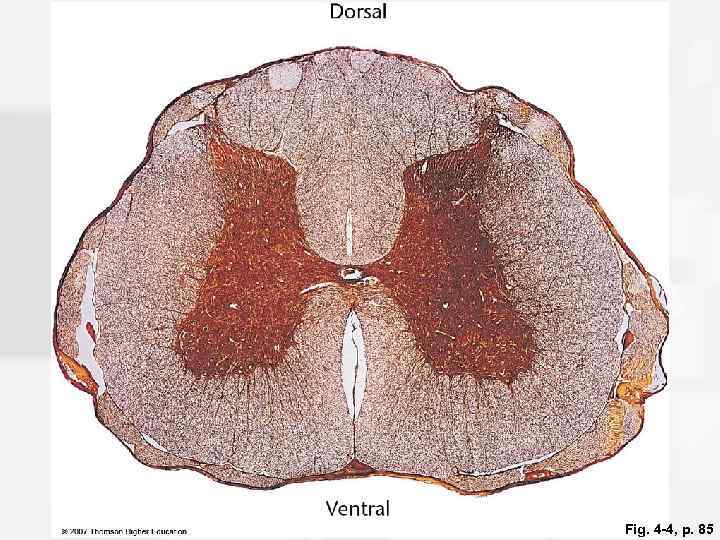

Structure of the Vertebrate Nervous System • The spinal cord is comprised of: – grey matter-located in the center of the spinal cord and is denseley packed with cell bodies and dendrites – white matter – composed mostly of myelinated axons that carries information from the gray matter to the brain or other areas of the spinal cord. • Each segment sends sensory information to the brain and receives motor commands.

Structure of the Vertebrate Nervous System • The spinal cord is comprised of: – grey matter-located in the center of the spinal cord and is denseley packed with cell bodies and dendrites – white matter – composed mostly of myelinated axons that carries information from the gray matter to the brain or other areas of the spinal cord. • Each segment sends sensory information to the brain and receives motor commands.

Fig. 4 -5, p. 85

Fig. 4 -5, p. 85

Structure of the Vertebrate Nervous System • The Peripheral Nervous System (PNS) is comprised of the: 1. Somatic Nervous System 2. Autonomic Nervous System

Structure of the Vertebrate Nervous System • The Peripheral Nervous System (PNS) is comprised of the: 1. Somatic Nervous System 2. Autonomic Nervous System

Structure of the Vertebrate Nervous System • The Somatic Nervous System consists of nerves that: – Convey sensory information to the CNS. – Transmit messages for motor movement from the CNS to the body.

Structure of the Vertebrate Nervous System • The Somatic Nervous System consists of nerves that: – Convey sensory information to the CNS. – Transmit messages for motor movement from the CNS to the body.

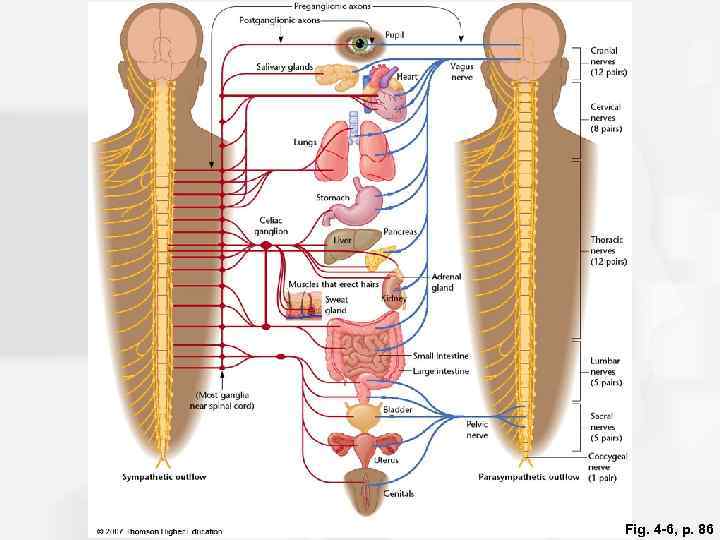

Structure of the Vertebrate Nervous System • The autonomic nervous system regulates the automatic behaviors of the body (heart rate, blood pressure, respiration, digestion etc). • The autonomic nervous system can be divided into two subsystems: 1. The Sympathetic Nervous System. 2. The Parasympathetic Nervous System.

Structure of the Vertebrate Nervous System • The autonomic nervous system regulates the automatic behaviors of the body (heart rate, blood pressure, respiration, digestion etc). • The autonomic nervous system can be divided into two subsystems: 1. The Sympathetic Nervous System. 2. The Parasympathetic Nervous System.

Fig. 4 -6, p. 86

Fig. 4 -6, p. 86

Structure of the Vertebrate Nervous System • The sympathetic nervous system is a network of nerves that prepares the organs for rigorous activity: – increases heart rate, blood pressure, respiration, etc. (“fight or flight” response) – comprised of ganglia on the left and right of the spinal cord – mainly uses norepinephrine as a neurotransmitter at the postganglionic synapses.

Structure of the Vertebrate Nervous System • The sympathetic nervous system is a network of nerves that prepares the organs for rigorous activity: – increases heart rate, blood pressure, respiration, etc. (“fight or flight” response) – comprised of ganglia on the left and right of the spinal cord – mainly uses norepinephrine as a neurotransmitter at the postganglionic synapses.

Structure of the Vertebrate Nervous System • The parasympathetic nervous system facilitates vegetative, nonemergency responses by the organs. – decreases functions increased by the sympathetic nervous system. – comprised of long preganglion axons extending from the spinal cord and short postganglionic fibers that attach to the organs themselves. – dominant during our relaxed states.

Structure of the Vertebrate Nervous System • The parasympathetic nervous system facilitates vegetative, nonemergency responses by the organs. – decreases functions increased by the sympathetic nervous system. – comprised of long preganglion axons extending from the spinal cord and short postganglionic fibers that attach to the organs themselves. – dominant during our relaxed states.

Structure of the Vertebrate Nervous System • Parasympathetic Nervous System (cont’d) – Postganglionic axons mostly release acetylcholine as a neurotransmitter

Structure of the Vertebrate Nervous System • Parasympathetic Nervous System (cont’d) – Postganglionic axons mostly release acetylcholine as a neurotransmitter

Structure of the Vertebrate Nervous System • The brain can be divided into three major divisions: 1. Hindbrain. 2. Midbrain. 3. Forebrain.

Structure of the Vertebrate Nervous System • The brain can be divided into three major divisions: 1. Hindbrain. 2. Midbrain. 3. Forebrain.

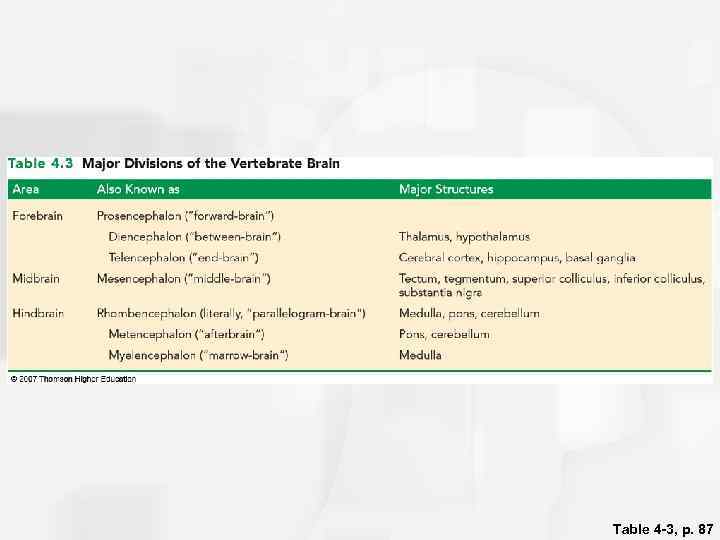

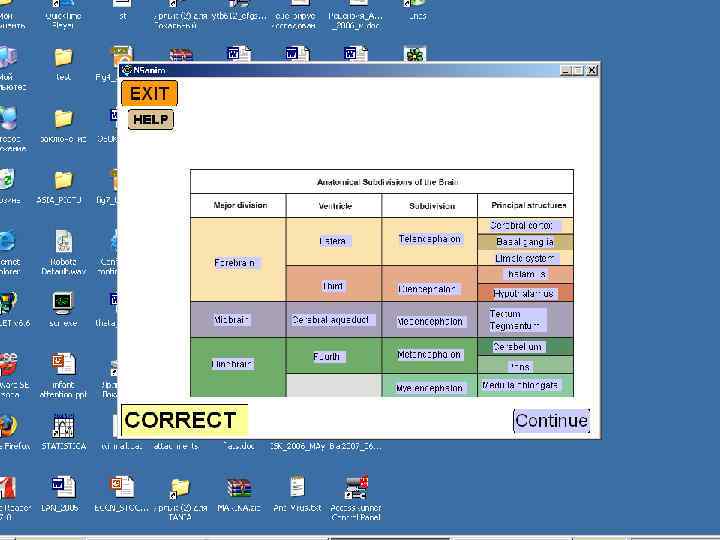

Table 4 -3, p. 87

Table 4 -3, p. 87

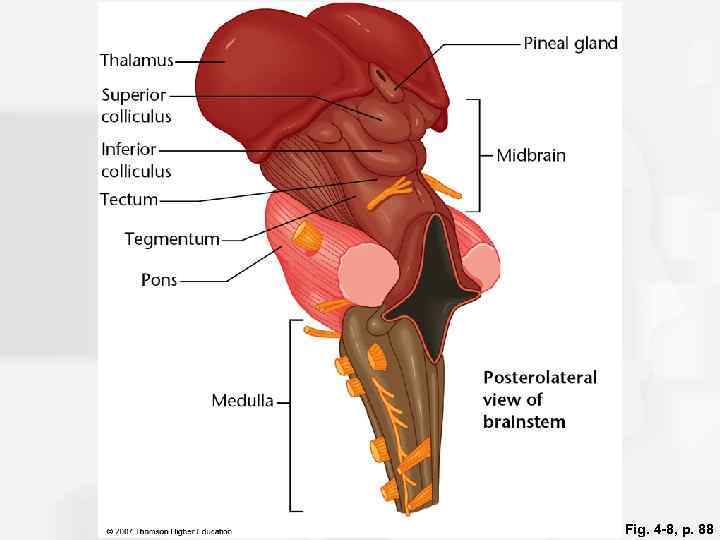

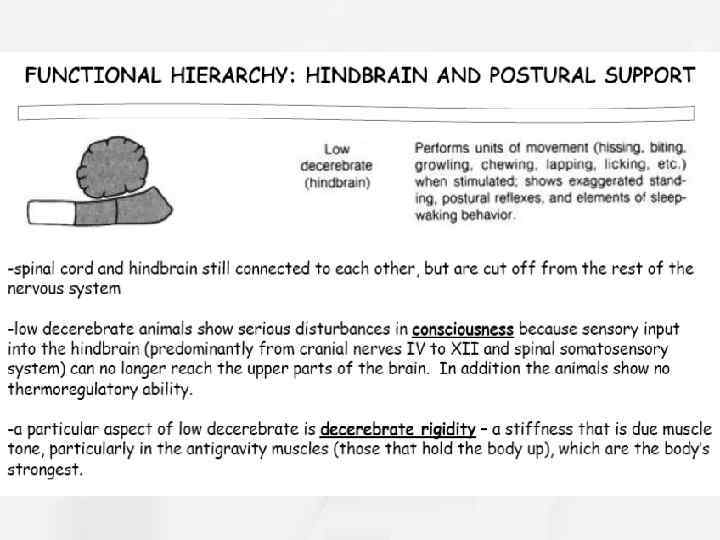

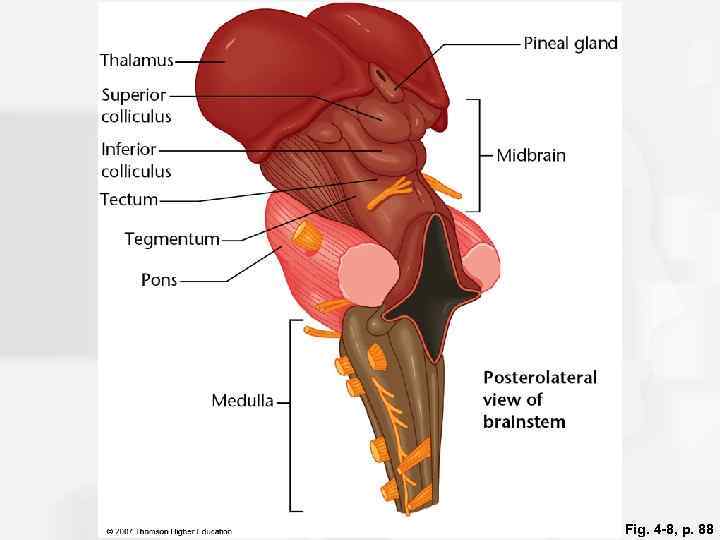

Structure of the Vertebrate Nervous System • The Hindbrain consists of the: – Medulla. – Pons. – Cerebellum. • Located at the posterior portion of the brain • Hindbrain structures, the midbrain and other central structures of the brain combine and make up the brain stem.

Structure of the Vertebrate Nervous System • The Hindbrain consists of the: – Medulla. – Pons. – Cerebellum. • Located at the posterior portion of the brain • Hindbrain structures, the midbrain and other central structures of the brain combine and make up the brain stem.

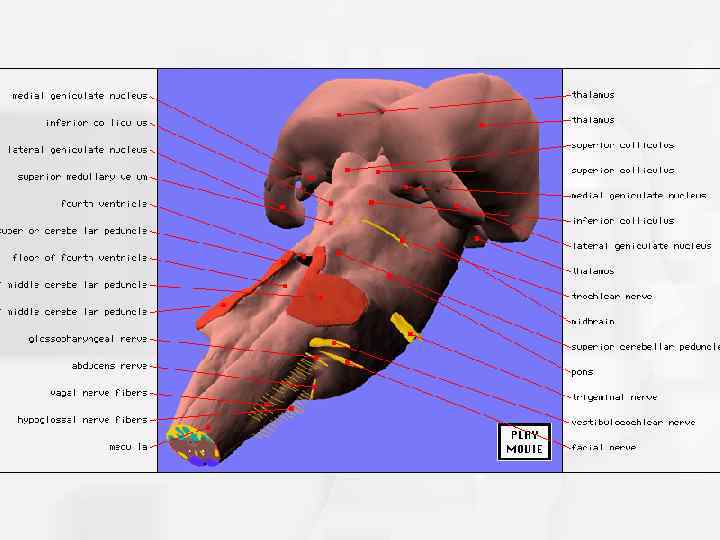

Fig. 4 -8, p. 88

Fig. 4 -8, p. 88

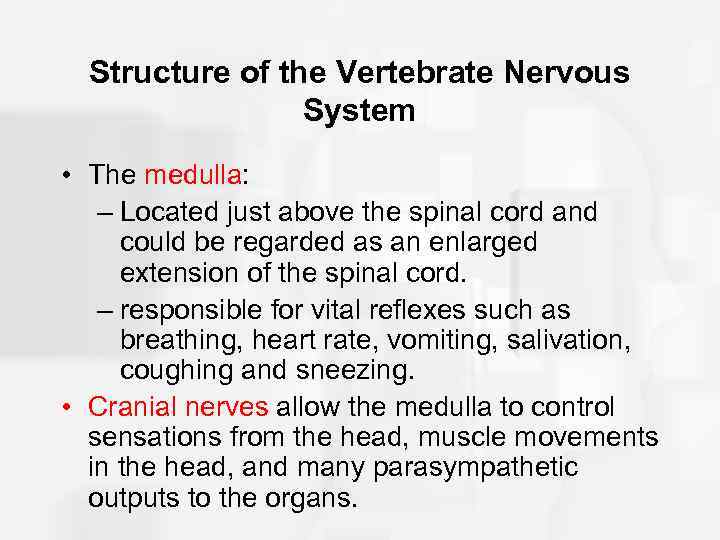

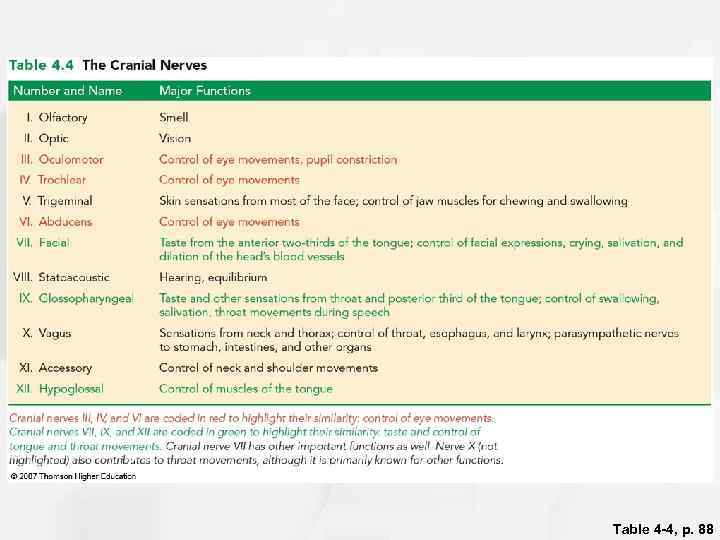

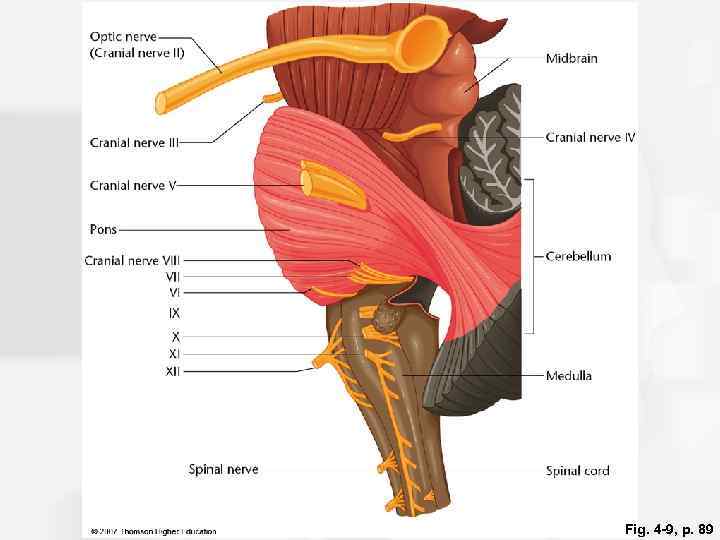

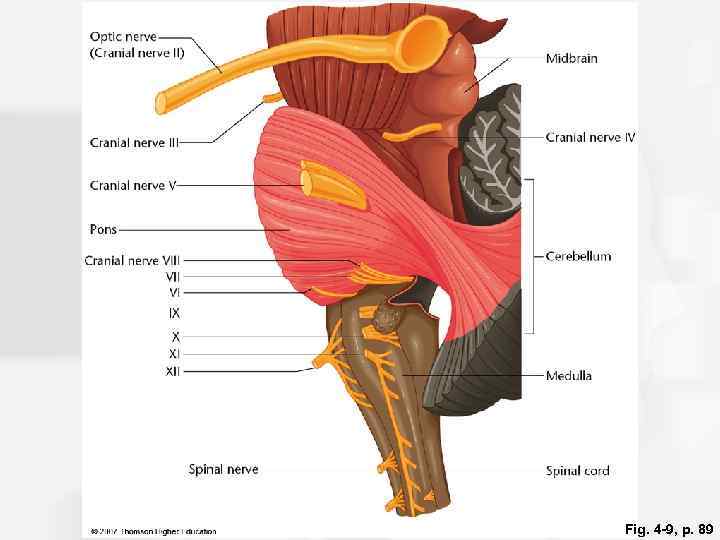

Structure of the Vertebrate Nervous System • The medulla: – Located just above the spinal cord and could be regarded as an enlarged extension of the spinal cord. – responsible for vital reflexes such as breathing, heart rate, vomiting, salivation, coughing and sneezing. • Cranial nerves allow the medulla to control sensations from the head, muscle movements in the head, and many parasympathetic outputs to the organs.

Structure of the Vertebrate Nervous System • The medulla: – Located just above the spinal cord and could be regarded as an enlarged extension of the spinal cord. – responsible for vital reflexes such as breathing, heart rate, vomiting, salivation, coughing and sneezing. • Cranial nerves allow the medulla to control sensations from the head, muscle movements in the head, and many parasympathetic outputs to the organs.

Table 4 -4, p. 88

Table 4 -4, p. 88

Fig. 4 -9, p. 89

Fig. 4 -9, p. 89

Structure of the Vertebrate Nervous System • Pons – lies on each side of the medulla (ventral and anterior). – along with the medulla, contains the reticular formation and raphe system. – works in conjunction to increase arousal and readiness of other parts of the brain.

Structure of the Vertebrate Nervous System • Pons – lies on each side of the medulla (ventral and anterior). – along with the medulla, contains the reticular formation and raphe system. – works in conjunction to increase arousal and readiness of other parts of the brain.

Structure of the Vertebrate Nervous System • The reticular formation: – descending portion is one of several brain areas that control the motor areas of the spinal cord. – ascending portion sends output to much of the cerebral cortex, selectively increasing arousal and attention. • The raphe system also sends axons to much of the forebrain, modifying the brain’s readiness to respond to stimuli.

Structure of the Vertebrate Nervous System • The reticular formation: – descending portion is one of several brain areas that control the motor areas of the spinal cord. – ascending portion sends output to much of the cerebral cortex, selectively increasing arousal and attention. • The raphe system also sends axons to much of the forebrain, modifying the brain’s readiness to respond to stimuli.

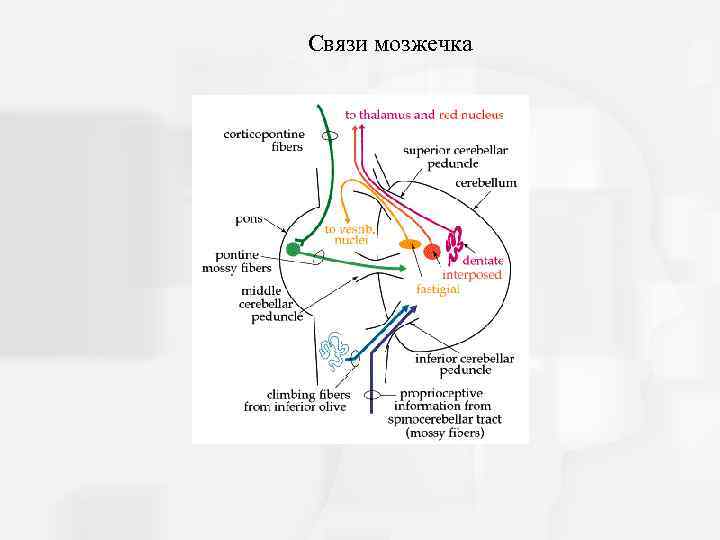

Structure of the Vertebrate Nervous System • The Cerebellum: – a structure located in the hindbrain with many deep folds. – helps regulate motor movement, balance and coordination. – is also important for shifting attention between auditory and visual stimuli.

Structure of the Vertebrate Nervous System • The Cerebellum: – a structure located in the hindbrain with many deep folds. – helps regulate motor movement, balance and coordination. – is also important for shifting attention between auditory and visual stimuli.

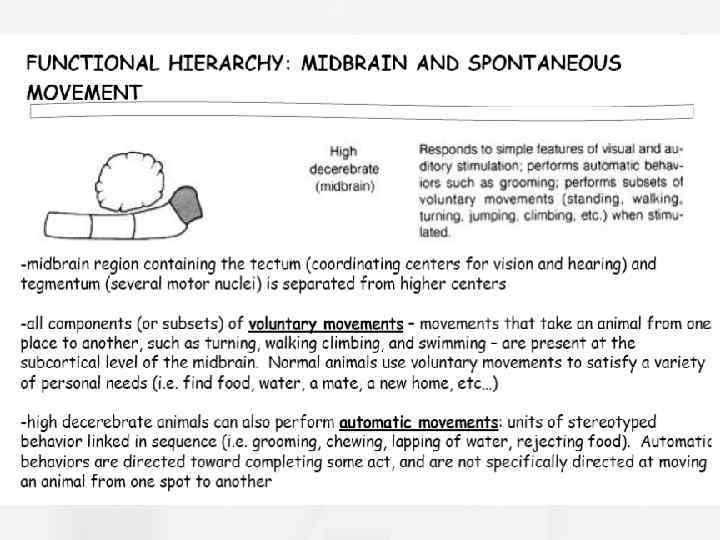

Structure of the Vertebrate Nervous System • The midbrain is comprised of the following structures: – Tectum – roof of the midbrain – Superior colliculus &inferior colliculus– swellings on each side of the tectum and routes for sensory information – Tagmentum- the intermediate level of the midbrain – Substantia nigra - gives rise to the dopamine-containing pathway

Structure of the Vertebrate Nervous System • The midbrain is comprised of the following structures: – Tectum – roof of the midbrain – Superior colliculus &inferior colliculus– swellings on each side of the tectum and routes for sensory information – Tagmentum- the intermediate level of the midbrain – Substantia nigra - gives rise to the dopamine-containing pathway

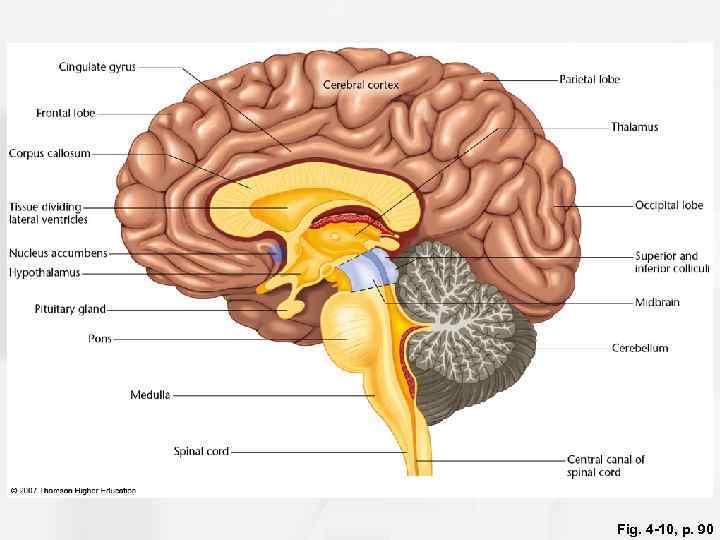

Structure of the Vertebrate Nervous System • The forebrain is the most anterior and prominent part of the mammalian brain and consists of two cerebral hemispheres – Consists of the outer cortex and subcortical regions. – outer portion is known as the “cerebral cortex”. • Receives sensory information and controls motor movement from the opposite (contralateral) side of the body.

Structure of the Vertebrate Nervous System • The forebrain is the most anterior and prominent part of the mammalian brain and consists of two cerebral hemispheres – Consists of the outer cortex and subcortical regions. – outer portion is known as the “cerebral cortex”. • Receives sensory information and controls motor movement from the opposite (contralateral) side of the body.

Fig. 4 -10, p. 90

Fig. 4 -10, p. 90

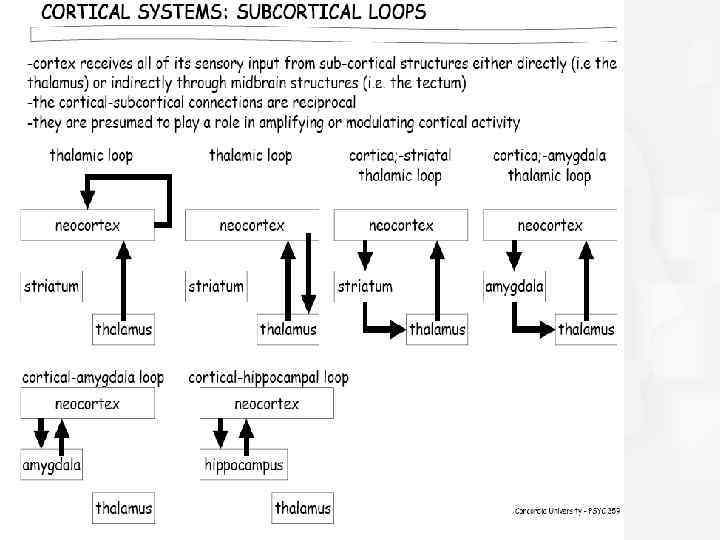

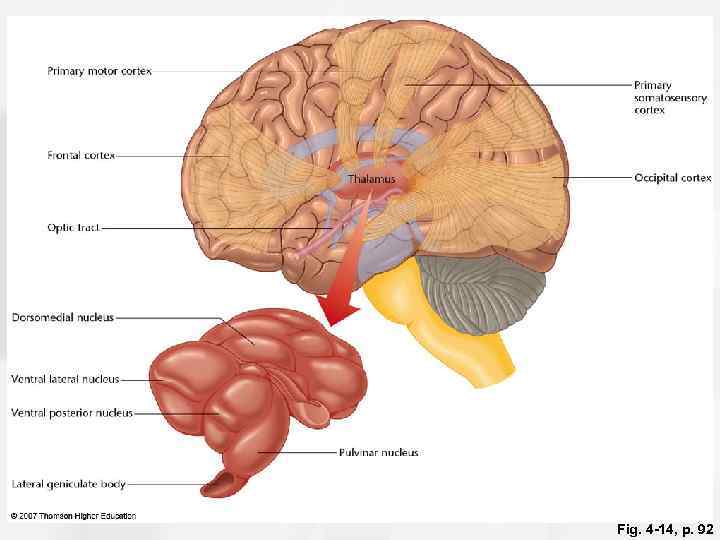

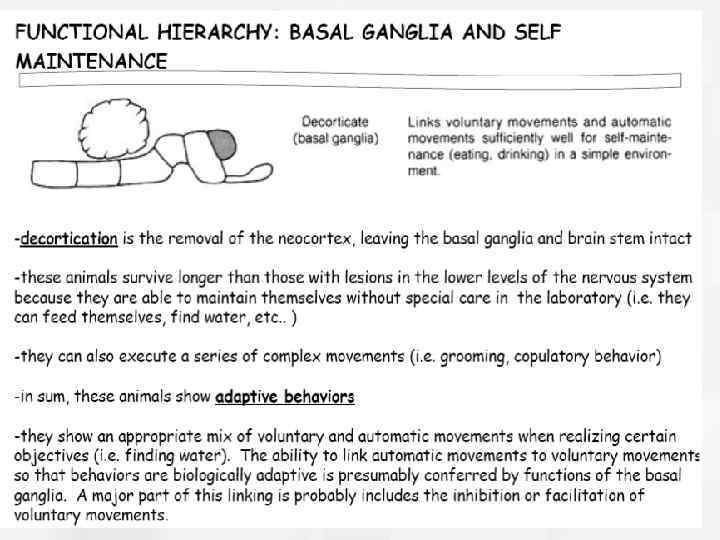

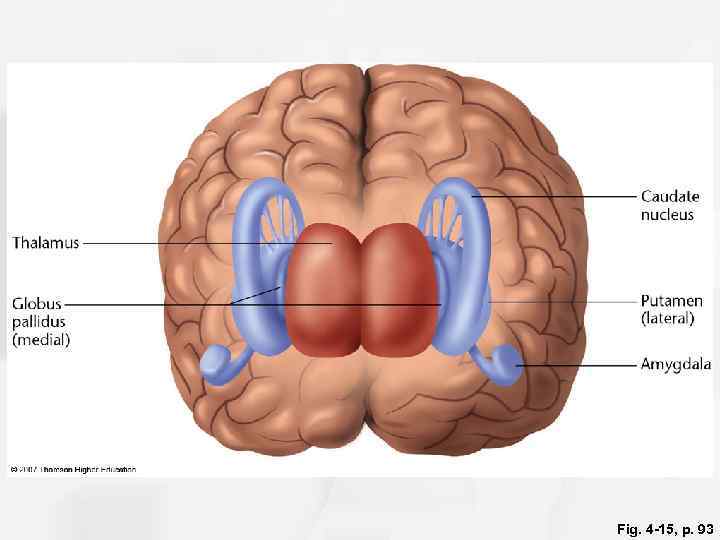

Structure of the Vertebrate Nervous System • Subcortical regions are structures of the brain that lie underneath the cortex. • Subcortical structures of the forebrain include: – Thalamus - relay station from the sensory organs and main source of input to the cortex. – Basal Ganglia - important for certain aspects of movement.

Structure of the Vertebrate Nervous System • Subcortical regions are structures of the brain that lie underneath the cortex. • Subcortical structures of the forebrain include: – Thalamus - relay station from the sensory organs and main source of input to the cortex. – Basal Ganglia - important for certain aspects of movement.

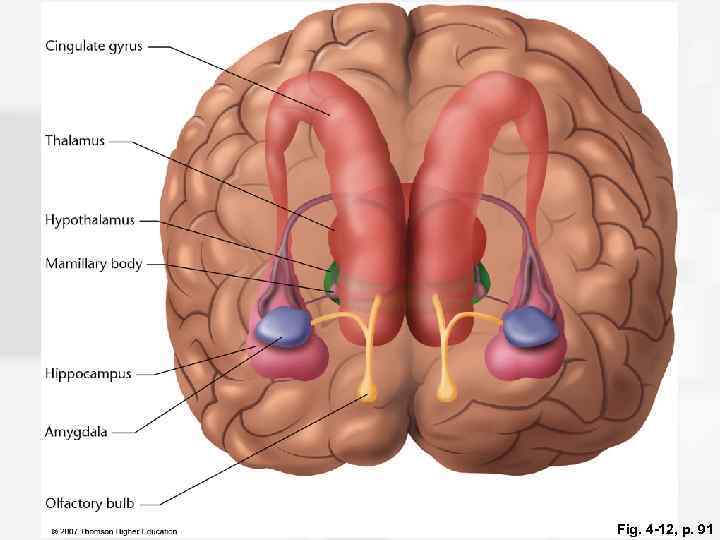

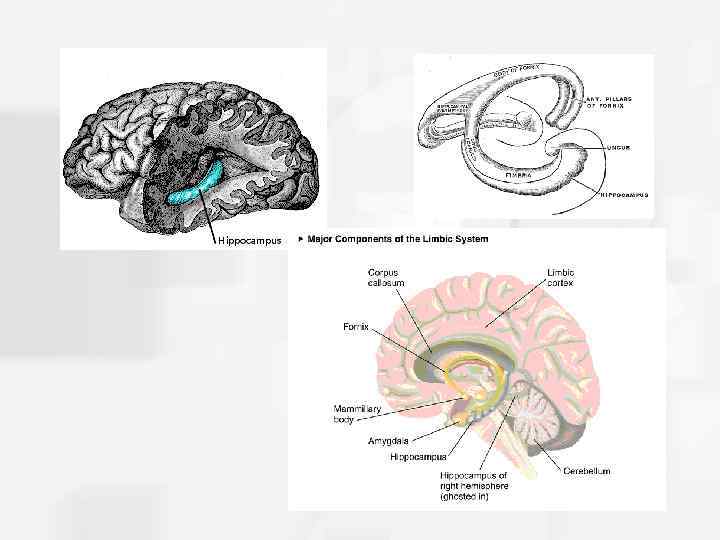

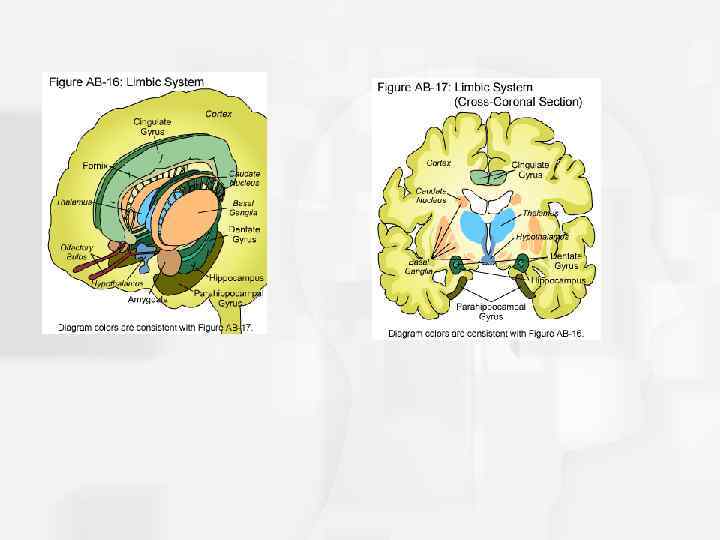

Structure of the Vertebrate Nervous System • The limbic system consists of a number of other interlinked structures that form a border around the brainstem. – Includes the olfactory bulb, hypothalamus, hippocampus, amygdala, and cingulate gyrus of the cerebral cortex – associated with motivation, emotion, drives and aggression.

Structure of the Vertebrate Nervous System • The limbic system consists of a number of other interlinked structures that form a border around the brainstem. – Includes the olfactory bulb, hypothalamus, hippocampus, amygdala, and cingulate gyrus of the cerebral cortex – associated with motivation, emotion, drives and aggression.

Fig. 4 -12, p. 91

Fig. 4 -12, p. 91

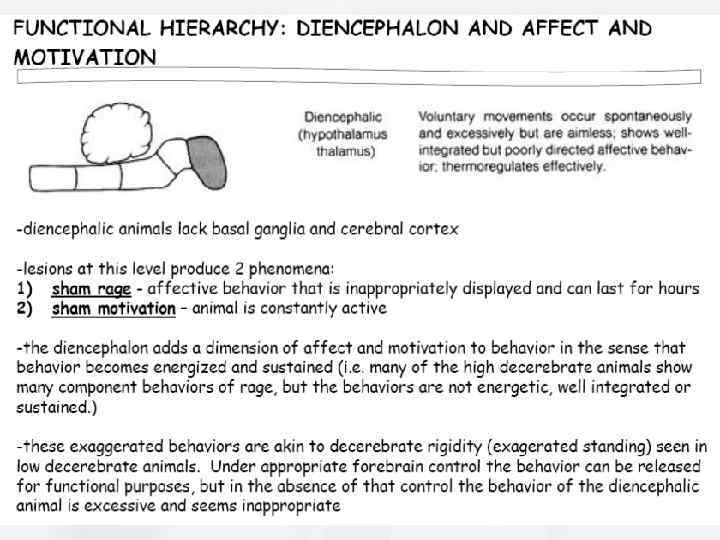

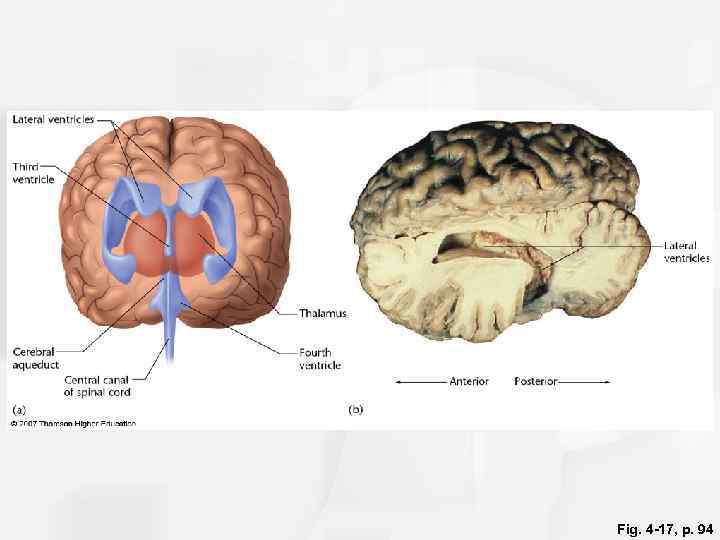

Structure of the Vertebrate Nervous System • Hypothalamus – Small area near the base of the brain. – Conveys messages to the pituitary gland to trigger the release of hormones. – Associated with behaviors such as eating, drinking, sexual behavior and other motivated behaviors. • Thalamus and the hypothalamus together form the “diencephalon”.

Structure of the Vertebrate Nervous System • Hypothalamus – Small area near the base of the brain. – Conveys messages to the pituitary gland to trigger the release of hormones. – Associated with behaviors such as eating, drinking, sexual behavior and other motivated behaviors. • Thalamus and the hypothalamus together form the “diencephalon”.

Fig. 4 -14, p. 92

Fig. 4 -14, p. 92

Structure of the Vertebrate Nervous System • Pituitary gland - hormone producing gland found at the base of the hypothalamus. • Basal Ganglia - comprised of the caudate nucleus, the putamen and the globus pallidus. – Associated with planning of motor movement, and aspects of memory and emotional expression.

Structure of the Vertebrate Nervous System • Pituitary gland - hormone producing gland found at the base of the hypothalamus. • Basal Ganglia - comprised of the caudate nucleus, the putamen and the globus pallidus. – Associated with planning of motor movement, and aspects of memory and emotional expression.

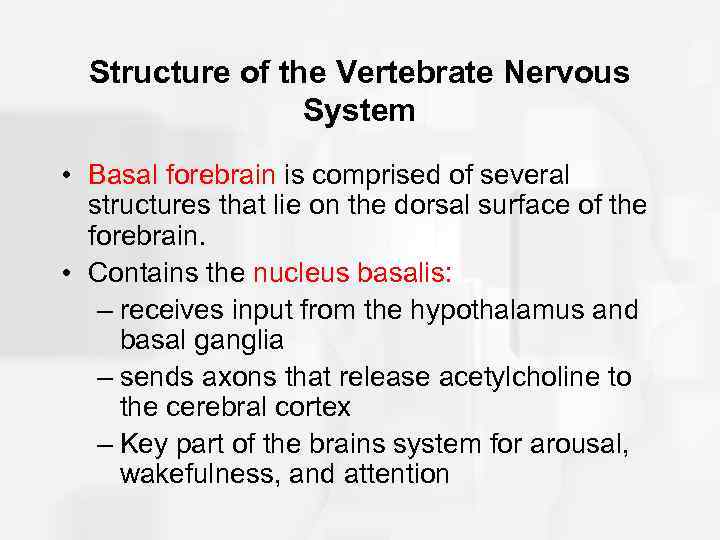

Structure of the Vertebrate Nervous System • Basal forebrain is comprised of several structures that lie on the dorsal surface of the forebrain. • Contains the nucleus basalis: – receives input from the hypothalamus and basal ganglia – sends axons that release acetylcholine to the cerebral cortex – Key part of the brains system for arousal, wakefulness, and attention

Structure of the Vertebrate Nervous System • Basal forebrain is comprised of several structures that lie on the dorsal surface of the forebrain. • Contains the nucleus basalis: – receives input from the hypothalamus and basal ganglia – sends axons that release acetylcholine to the cerebral cortex – Key part of the brains system for arousal, wakefulness, and attention

Fig. 4 -16, p. 93

Fig. 4 -16, p. 93

Structure of the Vertebrate Nervous System • Hippocampus is a large structure located between the thalamus and cerebral cortex. – critical for storing certain types of memory.

Structure of the Vertebrate Nervous System • Hippocampus is a large structure located between the thalamus and cerebral cortex. – critical for storing certain types of memory.

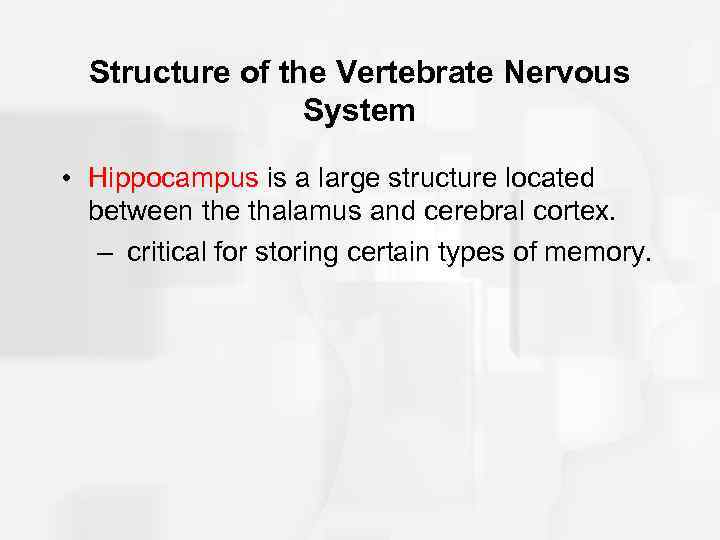

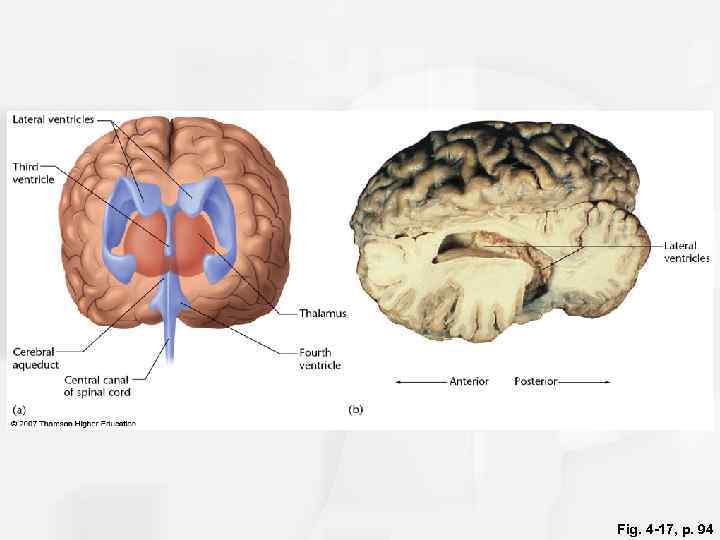

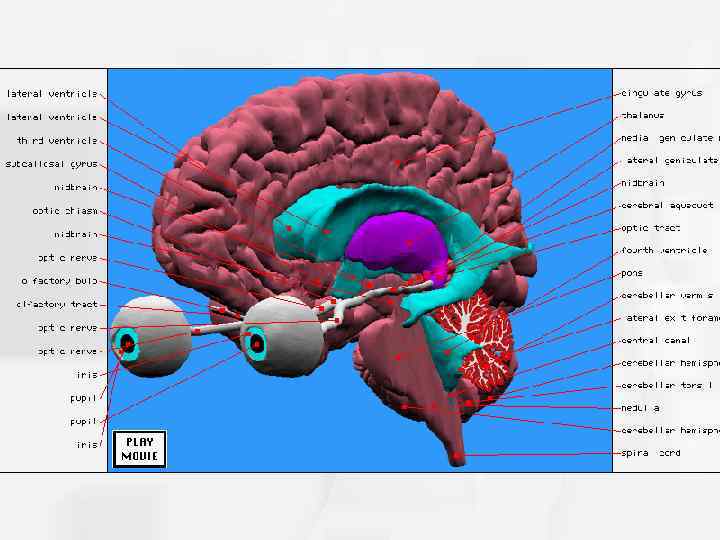

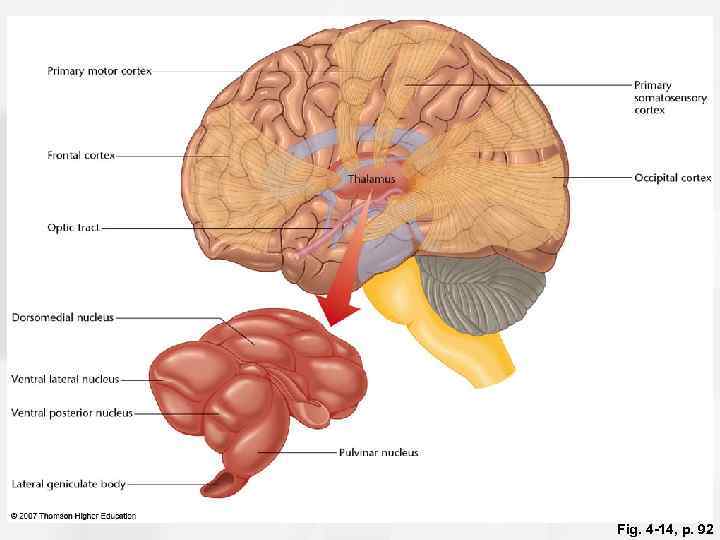

Structure of the Vertebrate Nervous System • The central canal is a fluid-filled channel in the center of the spinal cord. • The ventricles are four fluid-filled cavities within the brain containing cerebrospinal fluid. • Cerebrospinal fluid is a clear fluid similar to blood plasma found in the brain and spinal cord: – Provides “cushioning” for the brain. – Reservoir of hormones and nutrition for the brain and spinal cord.

Structure of the Vertebrate Nervous System • The central canal is a fluid-filled channel in the center of the spinal cord. • The ventricles are four fluid-filled cavities within the brain containing cerebrospinal fluid. • Cerebrospinal fluid is a clear fluid similar to blood plasma found in the brain and spinal cord: – Provides “cushioning” for the brain. – Reservoir of hormones and nutrition for the brain and spinal cord.

Fig. 4 -17, p. 94

Fig. 4 -17, p. 94

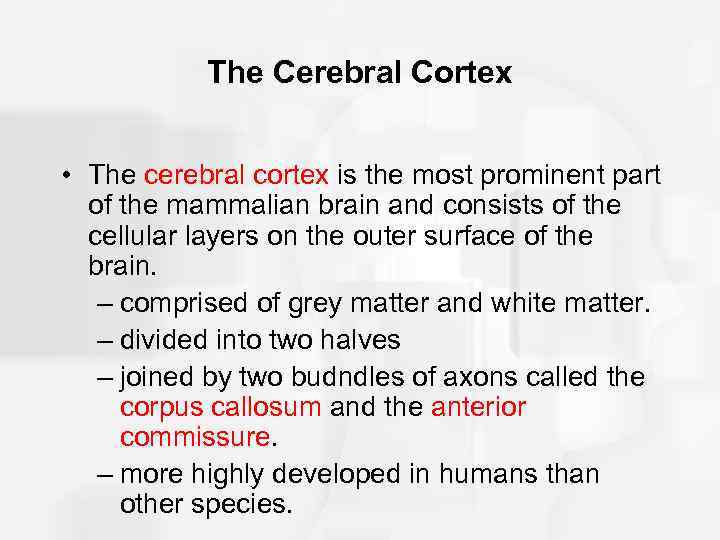

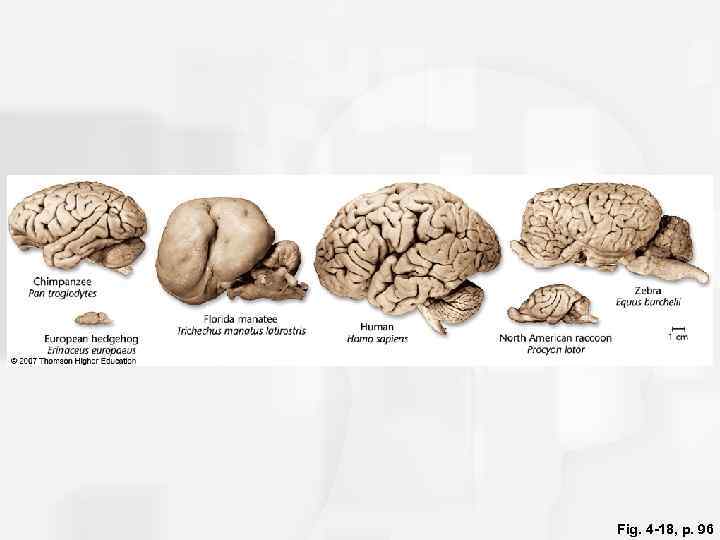

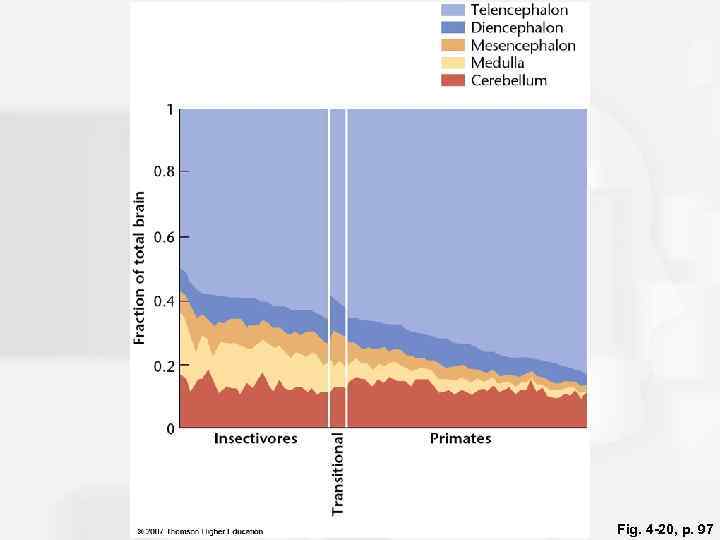

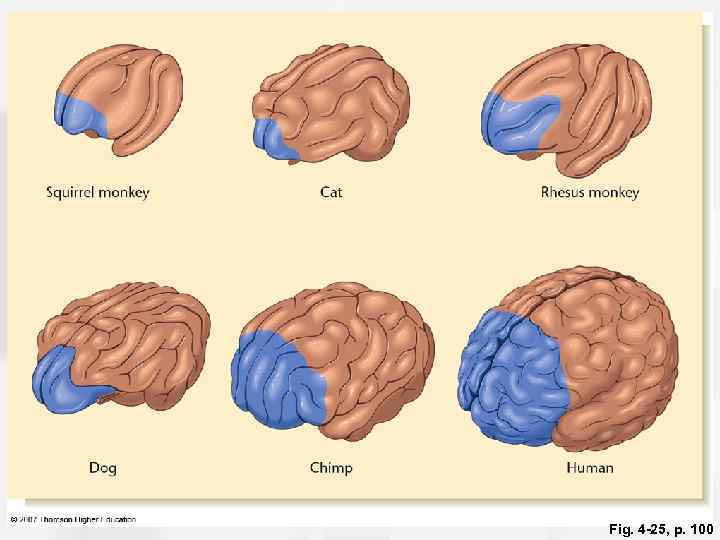

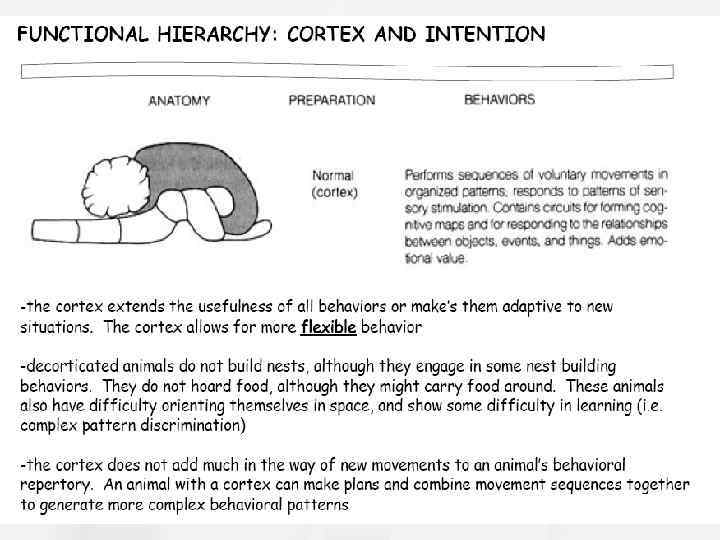

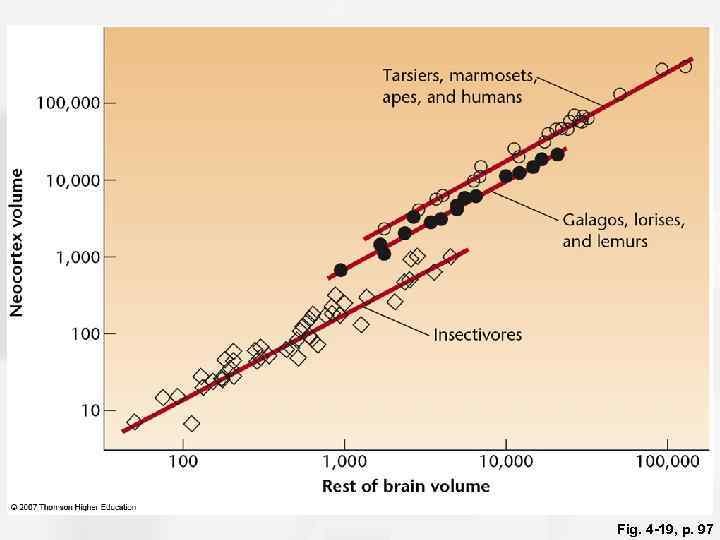

The Cerebral Cortex • The cerebral cortex is the most prominent part of the mammalian brain and consists of the cellular layers on the outer surface of the brain. – comprised of grey matter and white matter. – divided into two halves – joined by two budndles of axons called the corpus callosum and the anterior commissure. – more highly developed in humans than other species.

The Cerebral Cortex • The cerebral cortex is the most prominent part of the mammalian brain and consists of the cellular layers on the outer surface of the brain. – comprised of grey matter and white matter. – divided into two halves – joined by two budndles of axons called the corpus callosum and the anterior commissure. – more highly developed in humans than other species.

Fig. 4 -18, p. 96

Fig. 4 -18, p. 96

Fig. 4 -20, p. 97

Fig. 4 -20, p. 97

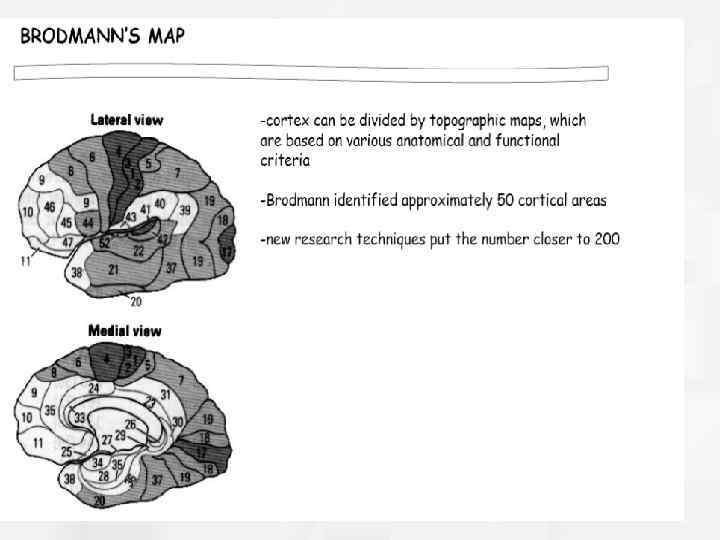

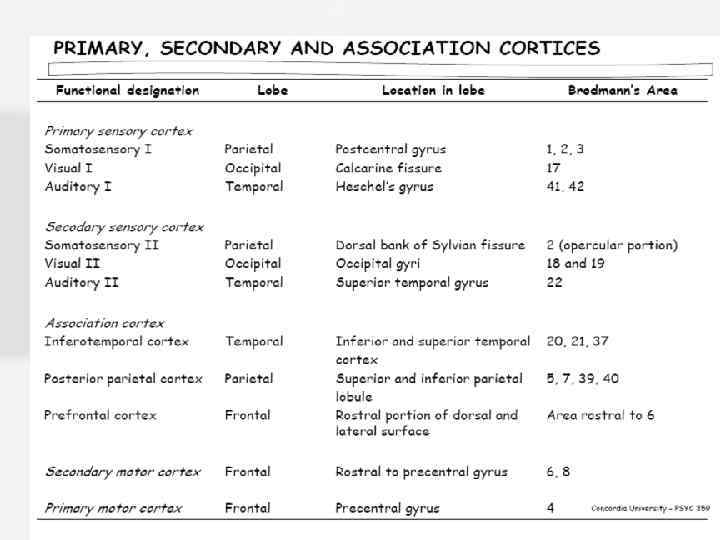

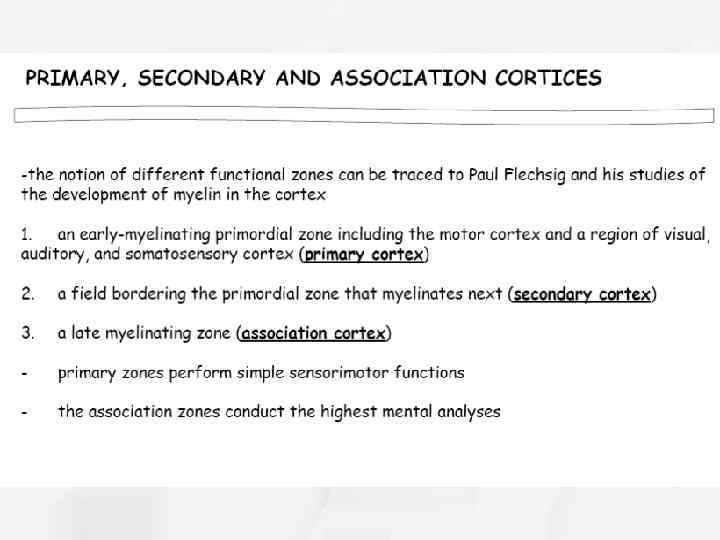

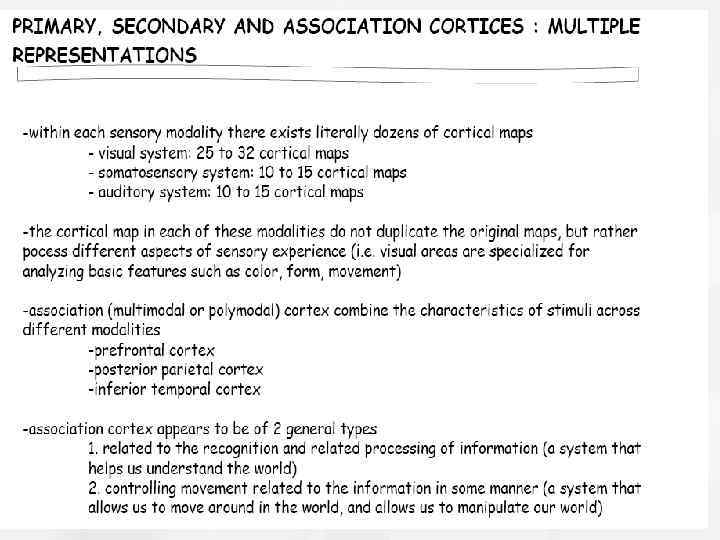

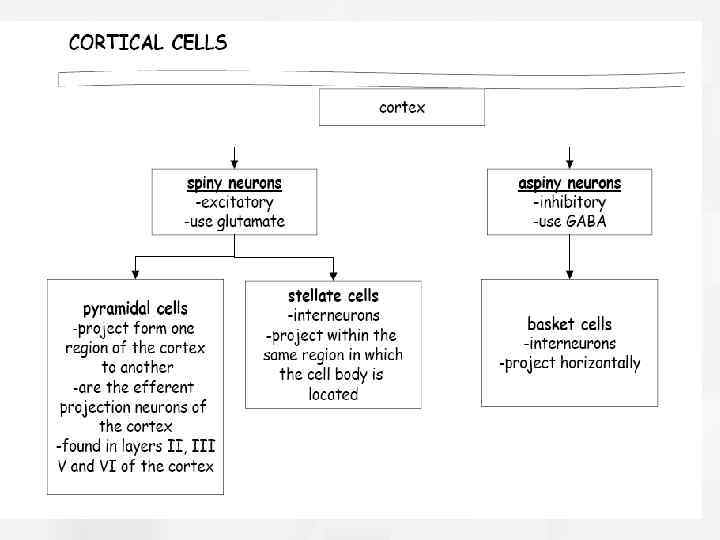

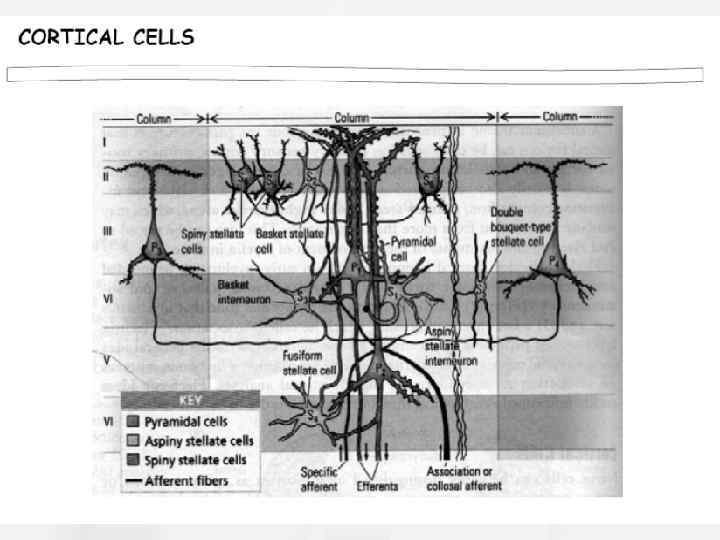

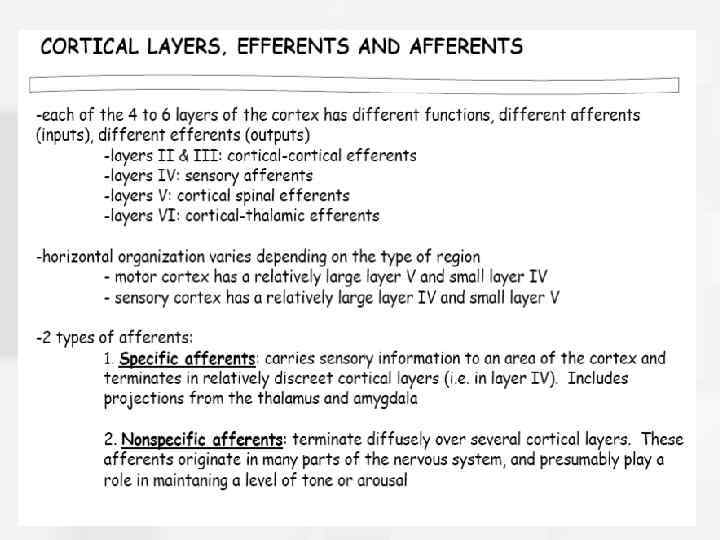

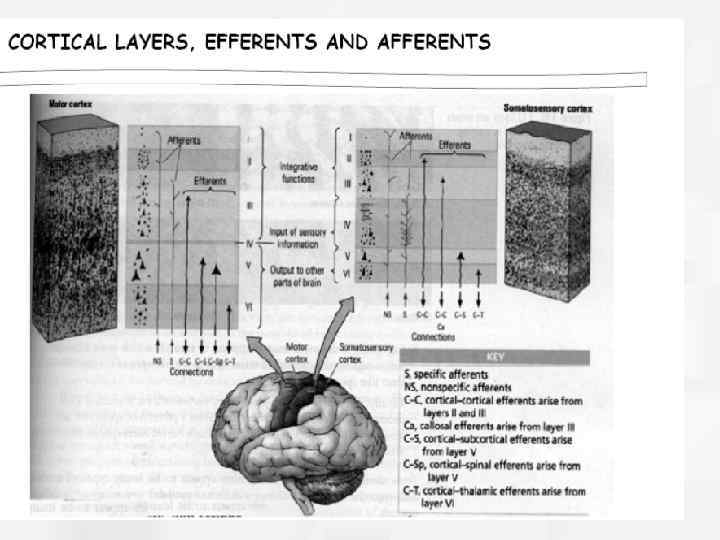

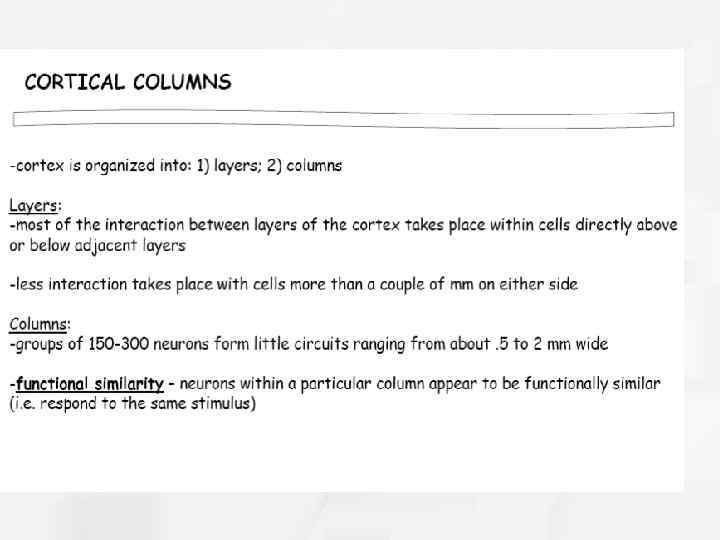

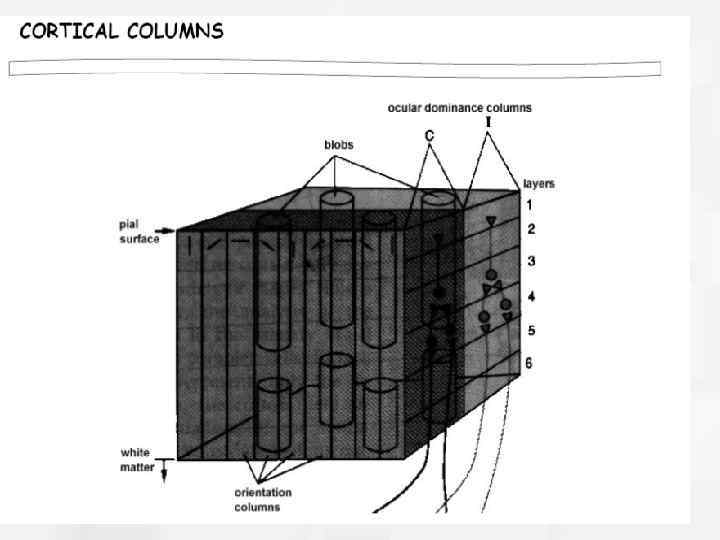

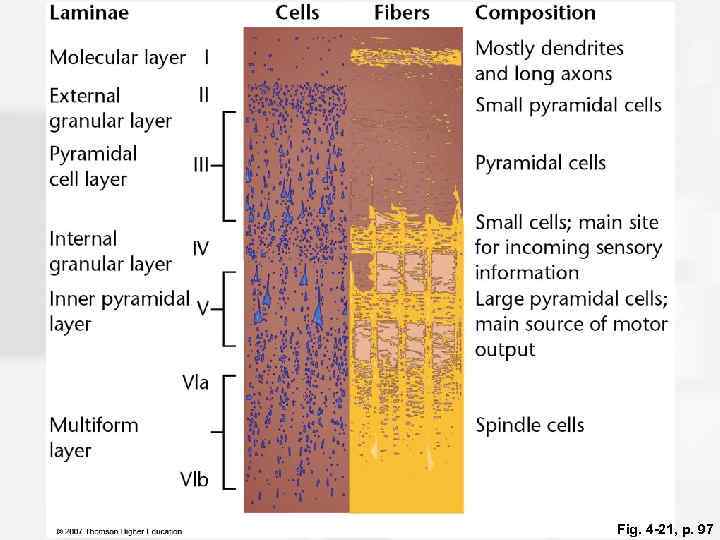

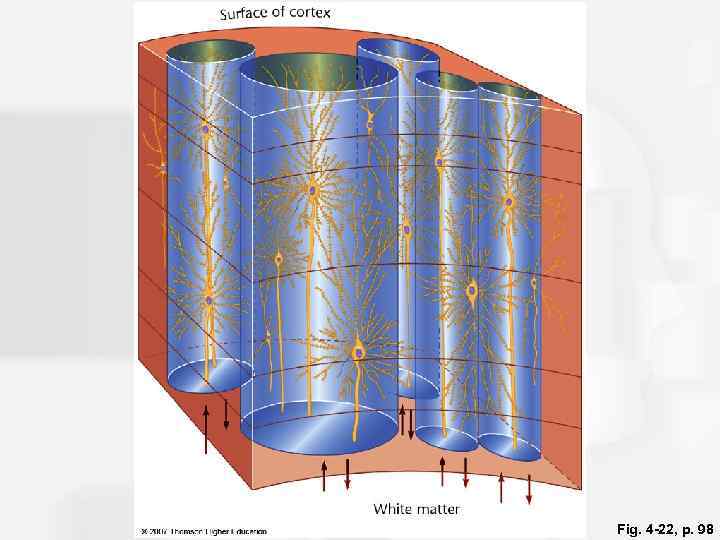

The Cerebral Cortex • Organization of the Cerebral Cortex: – Contains up to six distinct laminae (layers) that are parallel to the surface of the cortex. – Cells of the cortex are also divided into columns that lie perpendicular to the laminae. – Divided into four lobes: occipital, parietal, temporal, and frontal.

The Cerebral Cortex • Organization of the Cerebral Cortex: – Contains up to six distinct laminae (layers) that are parallel to the surface of the cortex. – Cells of the cortex are also divided into columns that lie perpendicular to the laminae. – Divided into four lobes: occipital, parietal, temporal, and frontal.

Fig. 4 -21, p. 97

Fig. 4 -21, p. 97

Fig. 4 -22, p. 98

Fig. 4 -22, p. 98

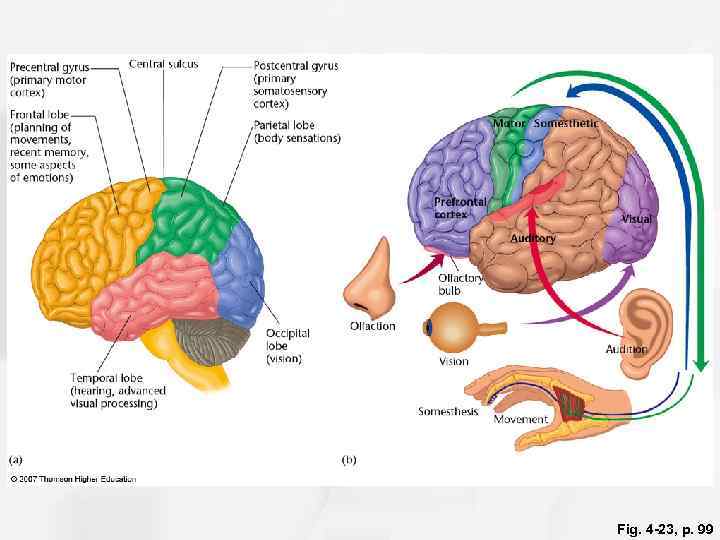

The Cerebral Cortex • 1. 2. 3. 4. The four lobes of the cerebral cortex include the following: Occipital lobe Parietal lobe Temporal lobe Frontal lobe

The Cerebral Cortex • 1. 2. 3. 4. The four lobes of the cerebral cortex include the following: Occipital lobe Parietal lobe Temporal lobe Frontal lobe

Fig. 4 -23, p. 99

Fig. 4 -23, p. 99

The Cerebral Cortex • Occipital lobe: – Located at the posterior end of the cortex. – Known as the striate cortex or the primary visual cortex. – Highly responsible for visual input. – Damage can result in cortical blindness.

The Cerebral Cortex • Occipital lobe: – Located at the posterior end of the cortex. – Known as the striate cortex or the primary visual cortex. – Highly responsible for visual input. – Damage can result in cortical blindness.

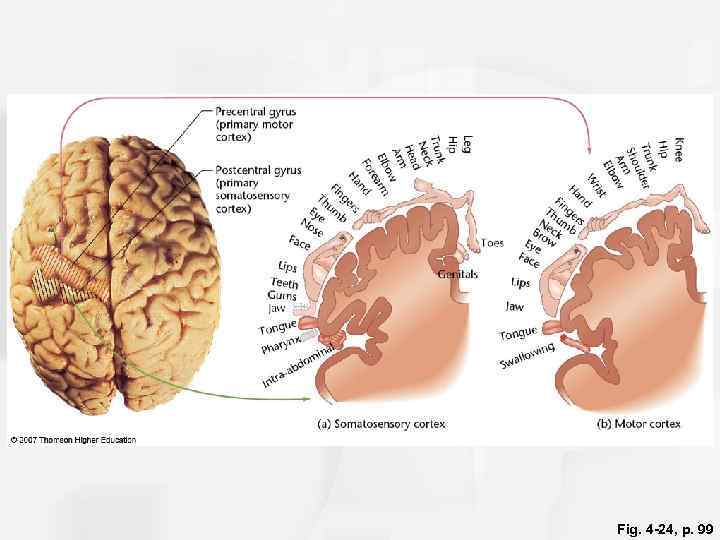

The Cerebral Cortex • Parietal lobe – Contains the postcentral gyrus (aka “primary somatosensory cortex”) is the primary target for touch sensations, and information from muscle-stretch receptors and joint receptors. – Also responsible for processing and integrating information about eye, head and body positions from information sent from muscles and joints.

The Cerebral Cortex • Parietal lobe – Contains the postcentral gyrus (aka “primary somatosensory cortex”) is the primary target for touch sensations, and information from muscle-stretch receptors and joint receptors. – Also responsible for processing and integrating information about eye, head and body positions from information sent from muscles and joints.

Fig. 4 -24, p. 99

Fig. 4 -24, p. 99

The Cerebral Cortex • Temporal Lobe – Located on the lateral portion of the hemispheres near the temples. – Target for auditory information and essential for processing spoken language. – Also responsible for complex aspects of vision including movement and some emotional and motivational behaviors.

The Cerebral Cortex • Temporal Lobe – Located on the lateral portion of the hemispheres near the temples. – Target for auditory information and essential for processing spoken language. – Also responsible for complex aspects of vision including movement and some emotional and motivational behaviors.

The Cerebral Cortex • The Frontal lobe: – Contains the prefrontal cortex and the precentral gyrus. – Precentral gyrus is also known as the primary motor cortex and is responsible for the control of fine motor movement. – Contains the prefrontal cortex- the integration center for all sensory information and other areasof the cortex. (most anterior portion of the frontal lobe)

The Cerebral Cortex • The Frontal lobe: – Contains the prefrontal cortex and the precentral gyrus. – Precentral gyrus is also known as the primary motor cortex and is responsible for the control of fine motor movement. – Contains the prefrontal cortex- the integration center for all sensory information and other areasof the cortex. (most anterior portion of the frontal lobe)

Fig. 4 -25, p. 100

Fig. 4 -25, p. 100

The Cerebral Cortex • The Prefrontal cortex (cont’d) – responsible for higher functions such as abstract thinking and planning. – responsible for our ability to remember recent events and information (“working memory”). – allows for regulation of impulsive behaviors and the control of more complex behaviors.

The Cerebral Cortex • The Prefrontal cortex (cont’d) – responsible for higher functions such as abstract thinking and planning. – responsible for our ability to remember recent events and information (“working memory”). – allows for regulation of impulsive behaviors and the control of more complex behaviors.

The Cerebral Cortex • Various parts of the cerebral cortex do not work independently of each other. – All areas of the brain communicate with each other • The binding problem refers to the question of how the visual, auditory, and other areas of the brain produce a perception of a single object. – perhaps the brain binds activity in different areas when they produce synchronous waves of activity

The Cerebral Cortex • Various parts of the cerebral cortex do not work independently of each other. – All areas of the brain communicate with each other • The binding problem refers to the question of how the visual, auditory, and other areas of the brain produce a perception of a single object. – perhaps the brain binds activity in different areas when they produce synchronous waves of activity

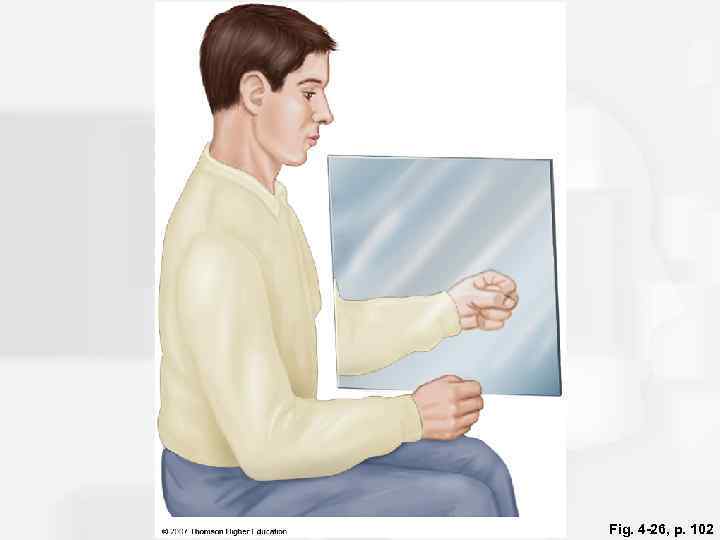

Fig. 4 -26, p. 102

Fig. 4 -26, p. 102

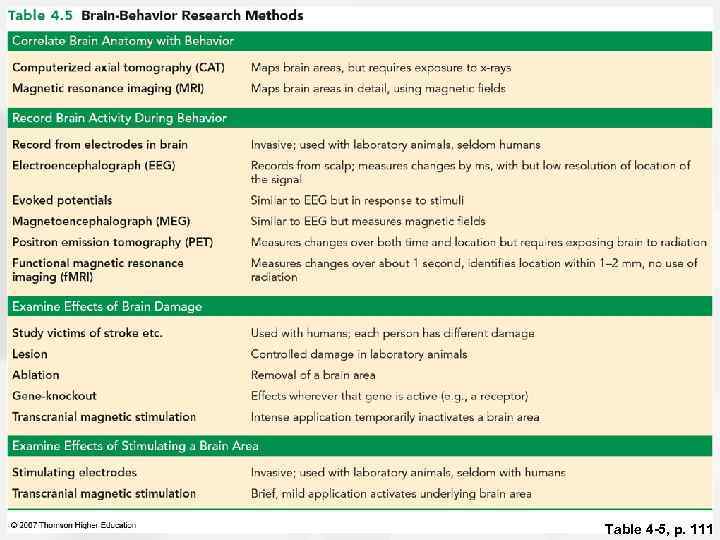

Research Methods • Main categories of research methods to study the brain include those that attempt to: 1. Correlate brain anatomy with behavior. 2. Record brain activity during behavior. 3. Examine the effects of brain damage. 4. Examine the effects of stimulating particular parts of the brain.

Research Methods • Main categories of research methods to study the brain include those that attempt to: 1. Correlate brain anatomy with behavior. 2. Record brain activity during behavior. 3. Examine the effects of brain damage. 4. Examine the effects of stimulating particular parts of the brain.

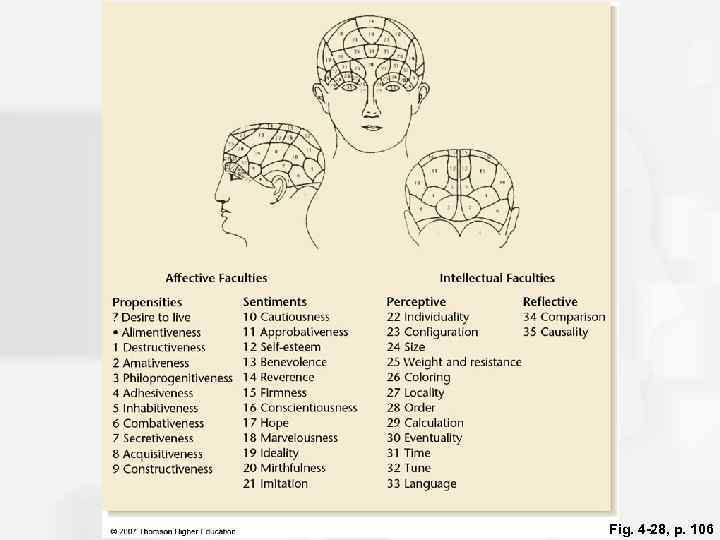

Research Methods • The process of relating skull anatomy to behavior is known as phrenology. – One of the first ways ever used to study the brain. – Yielded few, if any accurate results

Research Methods • The process of relating skull anatomy to behavior is known as phrenology. – One of the first ways ever used to study the brain. – Yielded few, if any accurate results

Fig. 4 -28, p. 106

Fig. 4 -28, p. 106

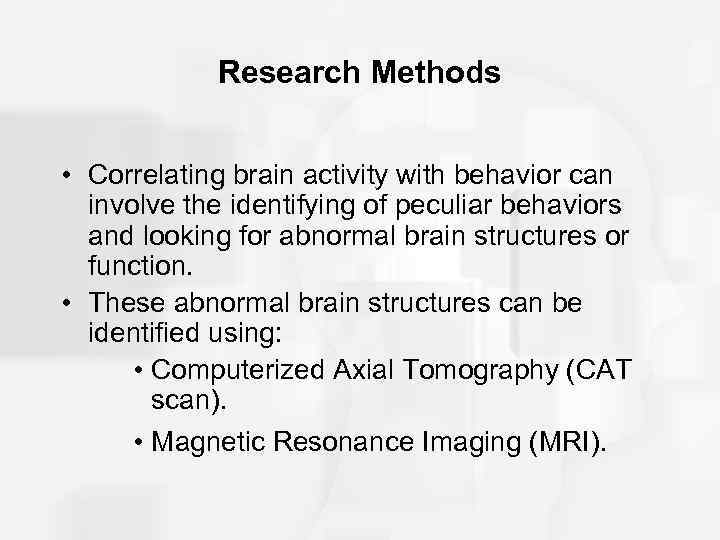

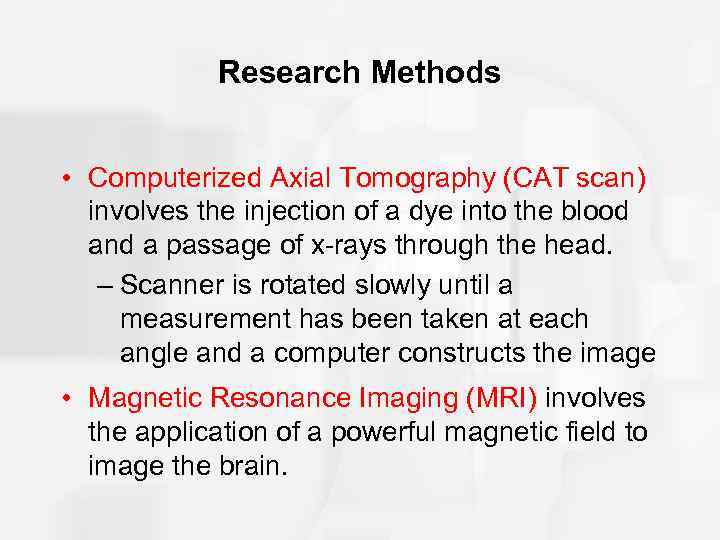

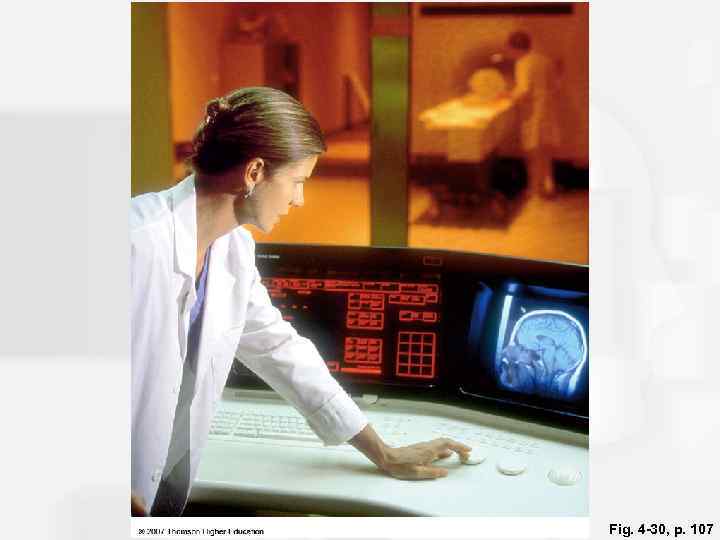

Research Methods • Correlating brain activity with behavior can involve the identifying of peculiar behaviors and looking for abnormal brain structures or function. • These abnormal brain structures can be identified using: • Computerized Axial Tomography (CAT scan). • Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI).

Research Methods • Correlating brain activity with behavior can involve the identifying of peculiar behaviors and looking for abnormal brain structures or function. • These abnormal brain structures can be identified using: • Computerized Axial Tomography (CAT scan). • Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI).

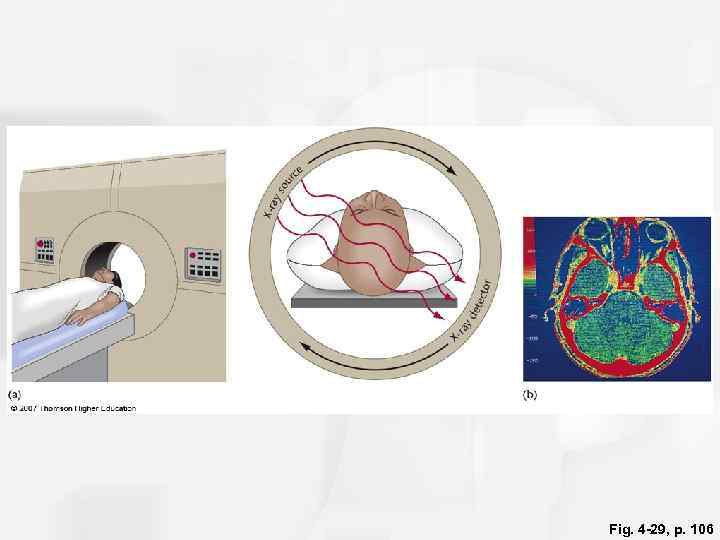

Research Methods • Computerized Axial Tomography (CAT scan) involves the injection of a dye into the blood and a passage of x-rays through the head. – Scanner is rotated slowly until a measurement has been taken at each angle and a computer constructs the image • Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) involves the application of a powerful magnetic field to image the brain.

Research Methods • Computerized Axial Tomography (CAT scan) involves the injection of a dye into the blood and a passage of x-rays through the head. – Scanner is rotated slowly until a measurement has been taken at each angle and a computer constructs the image • Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) involves the application of a powerful magnetic field to image the brain.

Fig. 4 -29, p. 106

Fig. 4 -29, p. 106

Fig. 4 -30, p. 107

Fig. 4 -30, p. 107

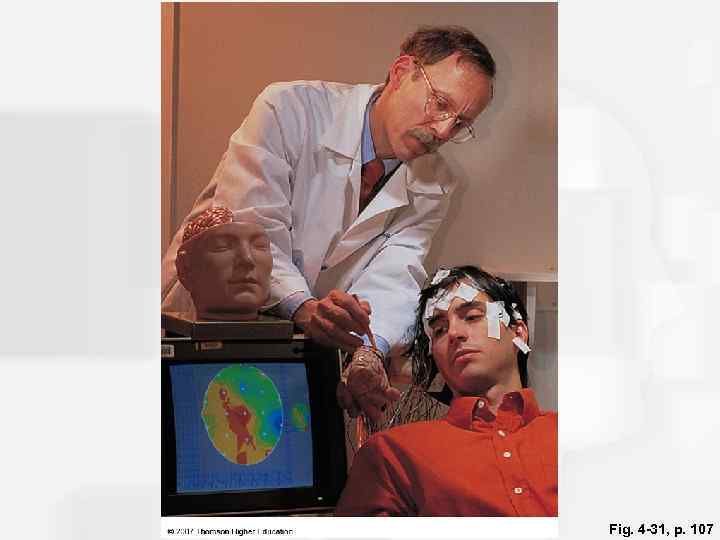

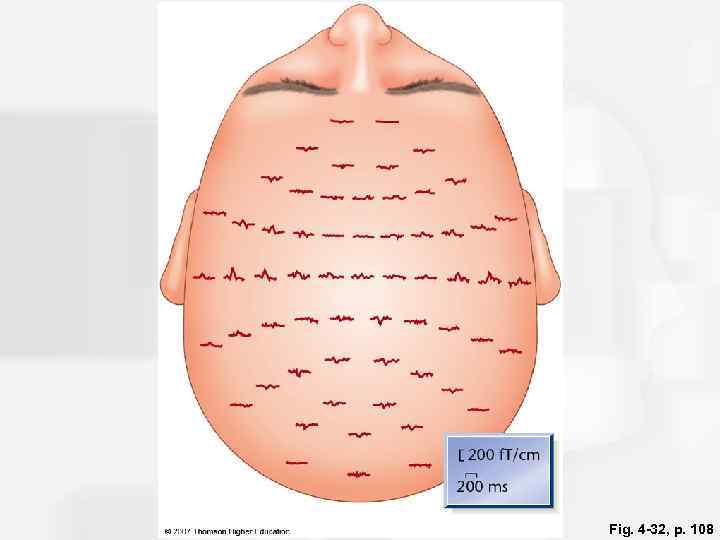

Research Methods • Recording brain activity involves using a variety of noninvasive methods including: – Electroencephalograph (EEG) - records electrical activity produced by various brain regions. – Positron-emission tomography (PET) - records emission of radioactivity from injected radioactive chemicals to produce a high- resolution image.

Research Methods • Recording brain activity involves using a variety of noninvasive methods including: – Electroencephalograph (EEG) - records electrical activity produced by various brain regions. – Positron-emission tomography (PET) - records emission of radioactivity from injected radioactive chemicals to produce a high- resolution image.

Fig. 4 -31, p. 107

Fig. 4 -31, p. 107

Fig. 4 -32, p. 108

Fig. 4 -32, p. 108

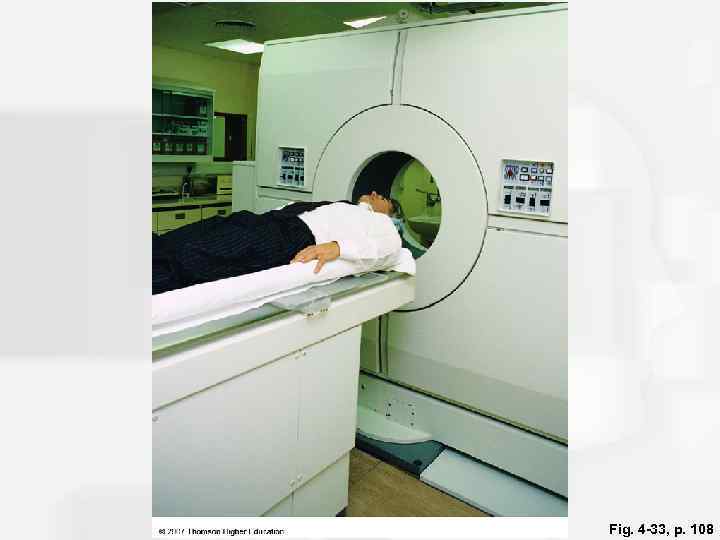

Fig. 4 -33, p. 108

Fig. 4 -33, p. 108

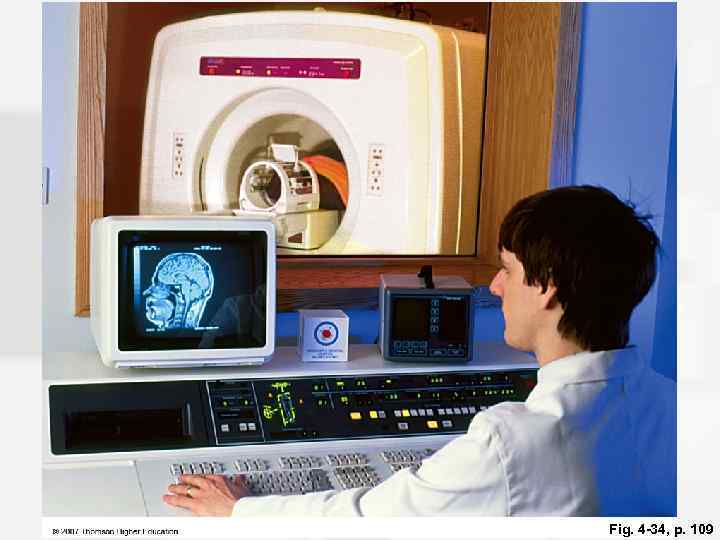

Research Methods • Regional Cerebral Blood Flow (r. CBF) inert radioactive chemicals are dissolved in the blood where a PET scanner is used to trace their distribution and indicate high levels of brain activity. • Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging uses oxygen consumption in the brain to provide a moving and detailed picture.

Research Methods • Regional Cerebral Blood Flow (r. CBF) inert radioactive chemicals are dissolved in the blood where a PET scanner is used to trace their distribution and indicate high levels of brain activity. • Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging uses oxygen consumption in the brain to provide a moving and detailed picture.

Fig. 4 -34, p. 109

Fig. 4 -34, p. 109

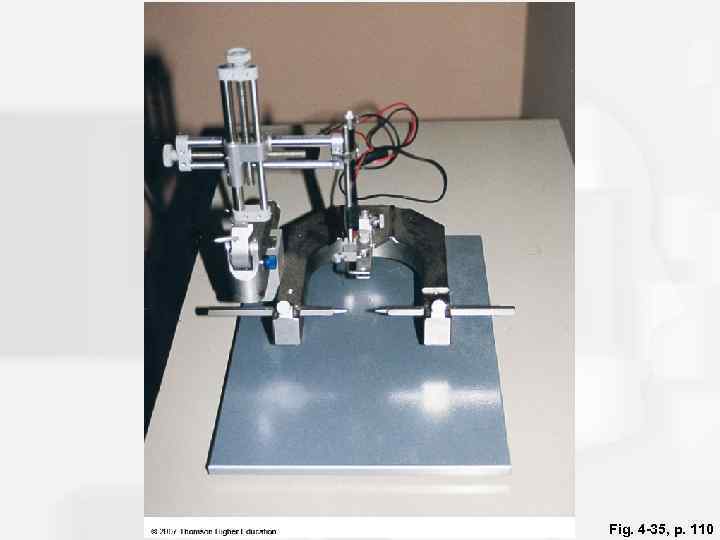

Research Methods • Examining the effects of damage to the brain is done using laboratory animals and includes: – Lesion techniques: purposely damaging parts of the brain. – Ablation techniques: removal of specific parts of the brain.

Research Methods • Examining the effects of damage to the brain is done using laboratory animals and includes: – Lesion techniques: purposely damaging parts of the brain. – Ablation techniques: removal of specific parts of the brain.

Fig. 4 -35, p. 110

Fig. 4 -35, p. 110

Research Methods • Other research methods used to inhibit particular brain structures include: – Gene-knockout approach: use of various biochemicals to inactivate parts of the brain by causing gene mutations critical to their development or functioning. – Transcranial magnetic stimulation: the application of intense magnetic fields to temporarily inactivate neurons.

Research Methods • Other research methods used to inhibit particular brain structures include: – Gene-knockout approach: use of various biochemicals to inactivate parts of the brain by causing gene mutations critical to their development or functioning. – Transcranial magnetic stimulation: the application of intense magnetic fields to temporarily inactivate neurons.

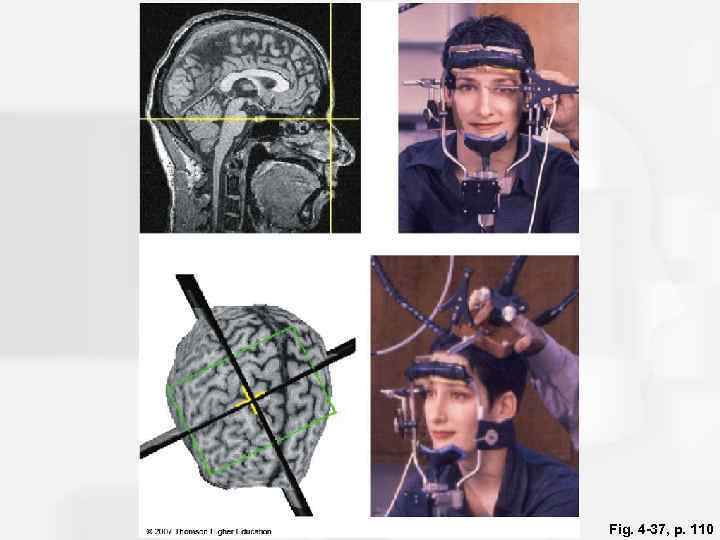

Fig. 4 -37, p. 110

Fig. 4 -37, p. 110

Research Methods • Brain Stimulation techniques assume stimulation of certain areas should increase activity. – Researchers observe the corresponding change in behavior as a particular region is stimulated.

Research Methods • Brain Stimulation techniques assume stimulation of certain areas should increase activity. – Researchers observe the corresponding change in behavior as a particular region is stimulated.

Table 4 -5, p. 111

Table 4 -5, p. 111

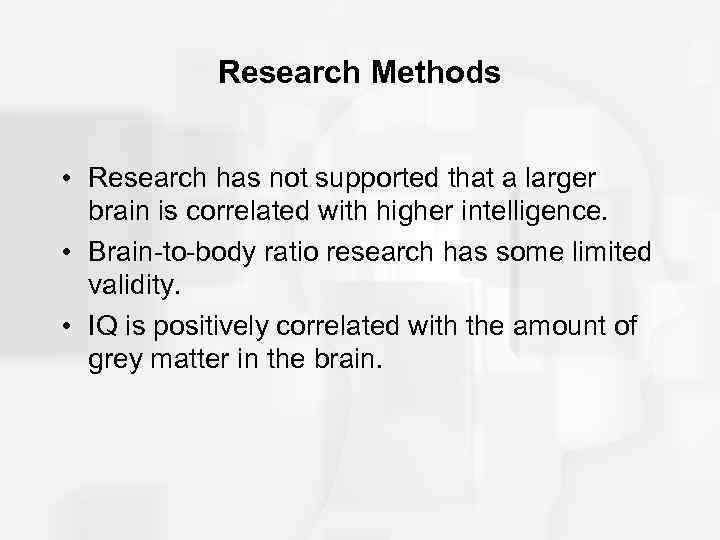

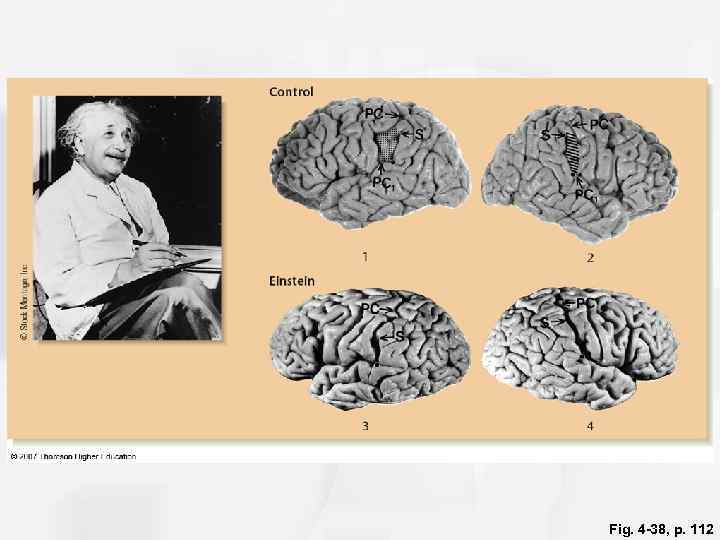

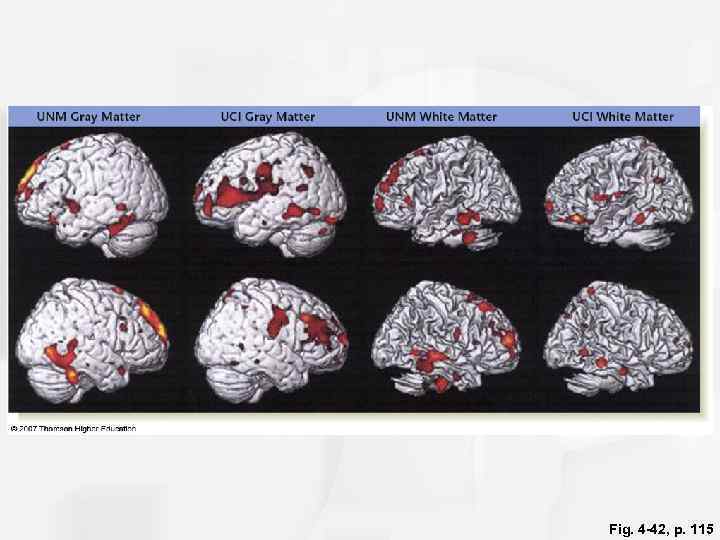

Research Methods • Research has not supported that a larger brain is correlated with higher intelligence. • Brain-to-body ratio research has some limited validity. • IQ is positively correlated with the amount of grey matter in the brain.

Research Methods • Research has not supported that a larger brain is correlated with higher intelligence. • Brain-to-body ratio research has some limited validity. • IQ is positively correlated with the amount of grey matter in the brain.

Fig. 4 -38, p. 112

Fig. 4 -38, p. 112

Fig. 4 -39, p. 113

Fig. 4 -39, p. 113

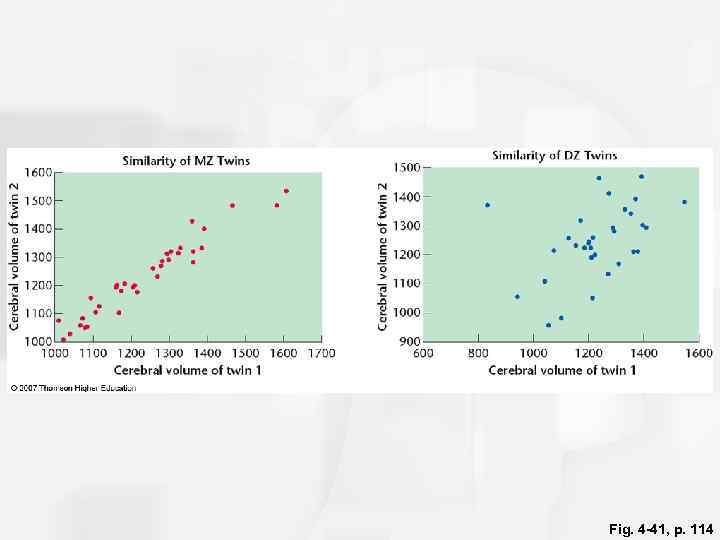

Research Methods • For monozygotic twins, the size of one twin’s brain correlates significantly with the other twin’s IQ. • Therefore, whatever genes increase the growth of the brain also increase IQ.

Research Methods • For monozygotic twins, the size of one twin’s brain correlates significantly with the other twin’s IQ. • Therefore, whatever genes increase the growth of the brain also increase IQ.

Fig. 4 -41, p. 114

Fig. 4 -41, p. 114

Fig. 4 -42, p. 115

Fig. 4 -42, p. 115

Fig. 4 -22, p. 98

Fig. 4 -22, p. 98

Fig. 4 -4, p. 85

Fig. 4 -4, p. 85

Fig. 4 -3, p. 84

Fig. 4 -3, p. 84

Fig. 4 -9, p. 89

Fig. 4 -9, p. 89

Связи мозжечка

Связи мозжечка

Fig. 4 -8, p. 88

Fig. 4 -8, p. 88

Fig. 4 -17, p. 94

Fig. 4 -17, p. 94

Fig. 4 -14, p. 92

Fig. 4 -14, p. 92

Fig. 4 -15, p. 93

Fig. 4 -15, p. 93

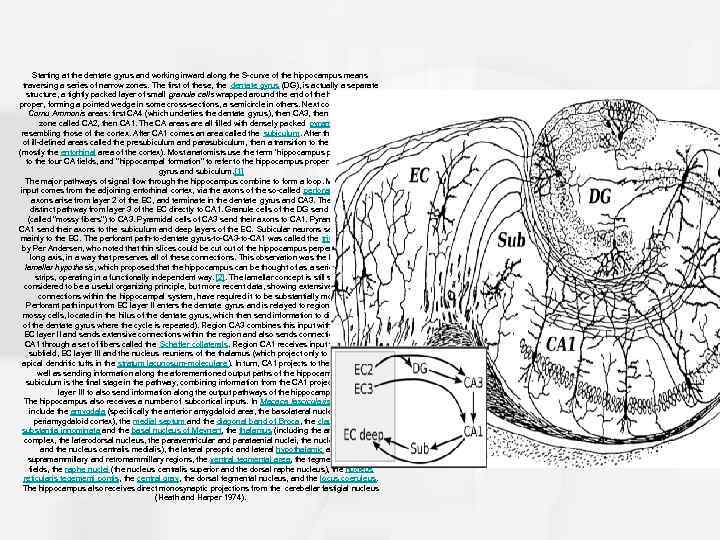

Starting at the dentate gyrus and working inward along the S-curve of the hippocampus means traversing a series of narrow zones. The first of these, the dentate gyrus (DG), is actually a separate structure, a tightly packed layer of small granule cells wrapped around the end of the hippocampus proper, forming a pointed wedge in some cross-sections, a semicircle in others. Next come a series of Cornu Ammonis areas: first CA 4 (which underlies the dentate gyrus), then CA 3, then a very small zone called CA 2, then CA 1. The CA areas are all filled with densely packed pyramidal cells resembling those of the cortex. After CA 1 comes an area called the subiculum. After this come a pair of ill-defined areas called the presubiculum and parasubiculum, then a transition to the cortex proper (mostly the entorhinal area of the cortex). Most anatomists use the term "hippocampus proper" to refer to the four CA fields, and " hippocampal formation" to refer to the hippocampus proper plus dentate gyrus and subiculum. [1] The major pathways of signal flow through the hippocampus combine to form a loop. Most external input comes from the adjoining entorhinal cortex, via the axons of the so-called perforant path. These axons arise from layer 2 of the EC, and terminate in the dentate gyrus and CA 3. There is also a distinct pathway from layer 3 of the EC directly to CA 1. Granule cells of the DG send their axons (called "mossy fibers") to CA 3. Pyramidal cells of CA 3 send their axons to CA 1. Pyramidal cells of CA 1 send their axons to the subiculum and deep layers of the EC. Subicular neurons send their axons mainly to the EC. The perforant path-to-dentate gyrus-to-CA 3 -to-CA 1 was called the trisynaptic circuit by Per Andersen, who noted that thin slices could be cut of the hippocampus perpendicular to its long axis, in a way that preserves all of these connections. This observation was the basis of his lamellar hypothesis, which proposed that the hippocampus can be thought of as a series of parallel strips, operating in a functionally independent way. [2]. The lamellar concept is still sometimes considered to be a useful organizing principle, but more recent data, showing extensive longitudinal connections within the hippocampal system, have required it to be substantially modified. [3] Perforant path input from EC layer II enters the dentate gyrus and is relayed to region CA 3 (and to mossy cells, located in the hilus of the dentate gyrus, which then send information to distant portions of the dentate gyrus where the cycle is repeated). Region CA 3 combines this input with signals from EC layer II and sends extensive connections within the region and also sends connections to region CA 1 through a set of fibers called the Schaffer collaterals. Region CA 1 receives input from the CA 3 subfield, EC layer III and the nucleus reuniens of the thalamus (which project only to the terminal apical dendritic tufts in the stratum lacunosum-moleculare). In turn, CA 1 projects to the subiculum as well as sending information along the aforementioned output paths of the hippocampus. The subiculum is the final stage in the pathway, combining information from the CA 1 projection and EC layer III to also send information along the output pathways of the hippocampus. The hippocampus also receives a number of subcortical inputs. In Macaca fascicularis, these inputs include the amygdala (specifically the anterior amygdaloid area, the basolateral nucleus, and the periamygdaloid cortex), the medial septum and the diagonal band of Broca, the claustrum, the substantia innominata and the basal nucleus of Meynert, the thalamus (including the anterior nuclear complex, the laterodorsal nucleus, the paraventricular and parataenial nuclei, the nucleus reuniens, and the nucleus centralis medialis), the lateral preoptic and lateral hypothalamic areas, the supramammillary and retromammillary regions, the ventral tegmental area, the tegmental reticular fields, the raphe nuclei (the nucleus centralis superior and the dorsal raphe nucleus), the nucleus reticularis tegementi pontis, the central gray, the dorsal tegmental nucleus, and the locus coeruleus. The hippocampus also receives direct monosynaptic projections from the cerebellar fastigial nucleus (Heath and Harper 1974).

Starting at the dentate gyrus and working inward along the S-curve of the hippocampus means traversing a series of narrow zones. The first of these, the dentate gyrus (DG), is actually a separate structure, a tightly packed layer of small granule cells wrapped around the end of the hippocampus proper, forming a pointed wedge in some cross-sections, a semicircle in others. Next come a series of Cornu Ammonis areas: first CA 4 (which underlies the dentate gyrus), then CA 3, then a very small zone called CA 2, then CA 1. The CA areas are all filled with densely packed pyramidal cells resembling those of the cortex. After CA 1 comes an area called the subiculum. After this come a pair of ill-defined areas called the presubiculum and parasubiculum, then a transition to the cortex proper (mostly the entorhinal area of the cortex). Most anatomists use the term "hippocampus proper" to refer to the four CA fields, and " hippocampal formation" to refer to the hippocampus proper plus dentate gyrus and subiculum. [1] The major pathways of signal flow through the hippocampus combine to form a loop. Most external input comes from the adjoining entorhinal cortex, via the axons of the so-called perforant path. These axons arise from layer 2 of the EC, and terminate in the dentate gyrus and CA 3. There is also a distinct pathway from layer 3 of the EC directly to CA 1. Granule cells of the DG send their axons (called "mossy fibers") to CA 3. Pyramidal cells of CA 3 send their axons to CA 1. Pyramidal cells of CA 1 send their axons to the subiculum and deep layers of the EC. Subicular neurons send their axons mainly to the EC. The perforant path-to-dentate gyrus-to-CA 3 -to-CA 1 was called the trisynaptic circuit by Per Andersen, who noted that thin slices could be cut of the hippocampus perpendicular to its long axis, in a way that preserves all of these connections. This observation was the basis of his lamellar hypothesis, which proposed that the hippocampus can be thought of as a series of parallel strips, operating in a functionally independent way. [2]. The lamellar concept is still sometimes considered to be a useful organizing principle, but more recent data, showing extensive longitudinal connections within the hippocampal system, have required it to be substantially modified. [3] Perforant path input from EC layer II enters the dentate gyrus and is relayed to region CA 3 (and to mossy cells, located in the hilus of the dentate gyrus, which then send information to distant portions of the dentate gyrus where the cycle is repeated). Region CA 3 combines this input with signals from EC layer II and sends extensive connections within the region and also sends connections to region CA 1 through a set of fibers called the Schaffer collaterals. Region CA 1 receives input from the CA 3 subfield, EC layer III and the nucleus reuniens of the thalamus (which project only to the terminal apical dendritic tufts in the stratum lacunosum-moleculare). In turn, CA 1 projects to the subiculum as well as sending information along the aforementioned output paths of the hippocampus. The subiculum is the final stage in the pathway, combining information from the CA 1 projection and EC layer III to also send information along the output pathways of the hippocampus. The hippocampus also receives a number of subcortical inputs. In Macaca fascicularis, these inputs include the amygdala (specifically the anterior amygdaloid area, the basolateral nucleus, and the periamygdaloid cortex), the medial septum and the diagonal band of Broca, the claustrum, the substantia innominata and the basal nucleus of Meynert, the thalamus (including the anterior nuclear complex, the laterodorsal nucleus, the paraventricular and parataenial nuclei, the nucleus reuniens, and the nucleus centralis medialis), the lateral preoptic and lateral hypothalamic areas, the supramammillary and retromammillary regions, the ventral tegmental area, the tegmental reticular fields, the raphe nuclei (the nucleus centralis superior and the dorsal raphe nucleus), the nucleus reticularis tegementi pontis, the central gray, the dorsal tegmental nucleus, and the locus coeruleus. The hippocampus also receives direct monosynaptic projections from the cerebellar fastigial nucleus (Heath and Harper 1974).

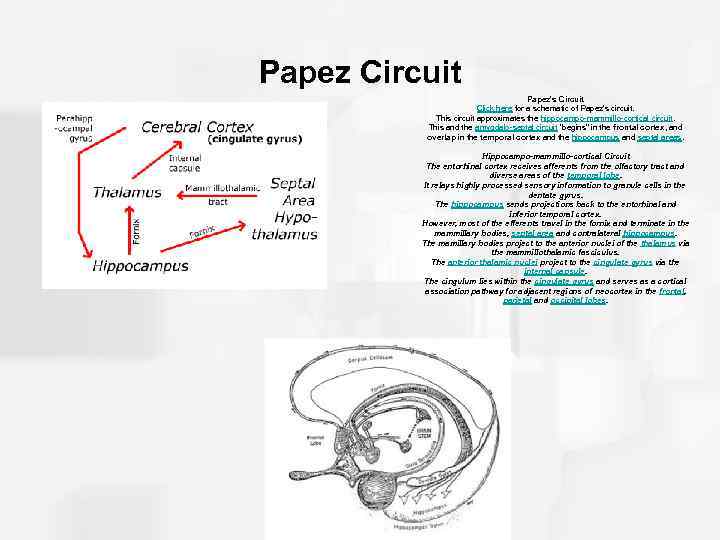

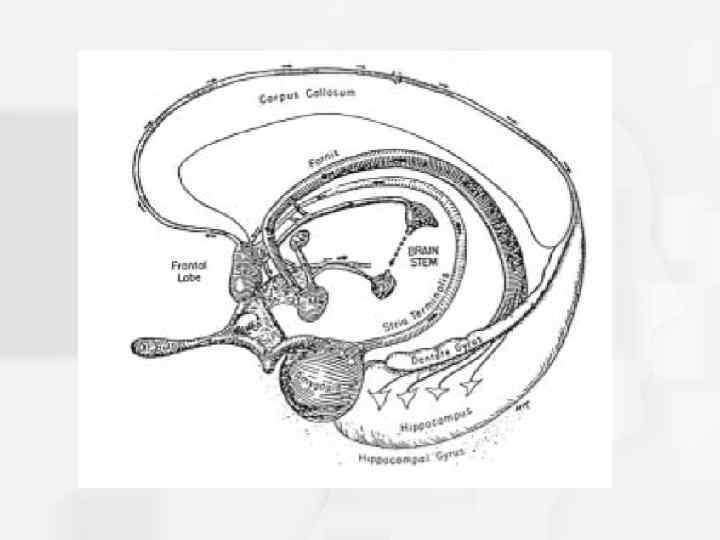

Papez Circuit Papez's Circuit Click here for a schematic of Papez's circuit. This circuit approximates the hippocampo-mammillo-cortical circuit. This and the amygdalo-septal circuit "begins" in the frontal cortex, and overlap in the temporal cortex and the hippocampus and septal areas. Hippocampo-mammillo-cortical Circuit The entorhinal cortex receives afferents from the olfactory tract and diverse areas of the temporal lobe. It relays highly processed sensory information to granule cells in the dentate gyrus. The hippocampus sends projections back to the entorhinal and inferior temporal cortex. However, most of the efferents travel in the fornix and terminate in the mammillary bodies, septal area and contralateral hippocampus. The mamillary bodies project to the anterior nuclei of the thalamus via the mammillothalamic fasciculus. The anterior thalamic nuclei project to the cingulate gyrus via the internal capsule. The cingulum lies within the cingulate gyrus and serves as a cortical association pathway for adjacent regions of neocortex in the frontal, parietal and occipital lobes.

Papez Circuit Papez's Circuit Click here for a schematic of Papez's circuit. This circuit approximates the hippocampo-mammillo-cortical circuit. This and the amygdalo-septal circuit "begins" in the frontal cortex, and overlap in the temporal cortex and the hippocampus and septal areas. Hippocampo-mammillo-cortical Circuit The entorhinal cortex receives afferents from the olfactory tract and diverse areas of the temporal lobe. It relays highly processed sensory information to granule cells in the dentate gyrus. The hippocampus sends projections back to the entorhinal and inferior temporal cortex. However, most of the efferents travel in the fornix and terminate in the mammillary bodies, septal area and contralateral hippocampus. The mamillary bodies project to the anterior nuclei of the thalamus via the mammillothalamic fasciculus. The anterior thalamic nuclei project to the cingulate gyrus via the internal capsule. The cingulum lies within the cingulate gyrus and serves as a cortical association pathway for adjacent regions of neocortex in the frontal, parietal and occipital lobes.

Fig. 4 -19, p. 97

Fig. 4 -19, p. 97