e3a88817dd429af1d9b6f0669f238dff.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 56

Chapter 3 Ricardian Model 1

Chapter 3 Ricardian Model 1

Ricardian Model • • • Opportunity costs and comparative advantage An Example Relative demand-relative supply analysis A one factor Ricardian model Production possibilities Gains from trade Wages and trade Misconceptions about comparative advantage Transportation costs and non-traded goods Empirical evidence 2

Ricardian Model • • • Opportunity costs and comparative advantage An Example Relative demand-relative supply analysis A one factor Ricardian model Production possibilities Gains from trade Wages and trade Misconceptions about comparative advantage Transportation costs and non-traded goods Empirical evidence 2

Introduction • Theories of why trade occurs can be grouped into three categories: • Market size and distance between markets determine how much countries buy and sell. These transactions benefit both buyers and sellers. • Differences in labor, physical capital, natural resources and technology create productive advantages for countries. • Economies of scale (larger is more efficient) create productive advantages for countries. 3

Introduction • Theories of why trade occurs can be grouped into three categories: • Market size and distance between markets determine how much countries buy and sell. These transactions benefit both buyers and sellers. • Differences in labor, physical capital, natural resources and technology create productive advantages for countries. • Economies of scale (larger is more efficient) create productive advantages for countries. 3

Introduction (cont. ) • The Ricardian model (chapter 3) says differences in productivity of labor between countries cause productive differences, leading to gains from trade. – Differences in productivity are usually explained by differences in technology. • The Heckscher-Ohlin model (chapter 4) says differences in labor, labor skills, physical capital and land between countries cause productive differences, leading to gains from trade. 4

Introduction (cont. ) • The Ricardian model (chapter 3) says differences in productivity of labor between countries cause productive differences, leading to gains from trade. – Differences in productivity are usually explained by differences in technology. • The Heckscher-Ohlin model (chapter 4) says differences in labor, labor skills, physical capital and land between countries cause productive differences, leading to gains from trade. 4

Comparative Advantage and Opportunity Cost • The Ricardian model uses the concepts of opportunity cost and comparative advantage. • The opportunity cost of producing something measures the cost of not being able to produce something else. 5

Comparative Advantage and Opportunity Cost • The Ricardian model uses the concepts of opportunity cost and comparative advantage. • The opportunity cost of producing something measures the cost of not being able to produce something else. 5

Comparative Advantage and Opportunity Cost (cont. ) • A country faces opportunity costs when it employs resources to produce goods and services. • For example, a limited number of workers could be employed to produce either wine or cheese. – The opportunity cost of producing wine is the amount of cheese not produced. – The opportunity cost of producing cheese is the amount of wine not produced. – A country faces a trade off: how much wine or cheese should it produce with the limited resources that it has? 6

Comparative Advantage and Opportunity Cost (cont. ) • A country faces opportunity costs when it employs resources to produce goods and services. • For example, a limited number of workers could be employed to produce either wine or cheese. – The opportunity cost of producing wine is the amount of cheese not produced. – The opportunity cost of producing cheese is the amount of wine not produced. – A country faces a trade off: how much wine or cheese should it produce with the limited resources that it has? 6

Comparative Advantage and Opportunity Cost (cont. ) • A country has a comparative advantage in producing a good if the opportunity cost of producing that good is lower in the country than it is in other countries. • A country with a comparative advantage in producing a good uses its resources most efficiently when it produces that good compared to producing other goods. 7

Comparative Advantage and Opportunity Cost (cont. ) • A country has a comparative advantage in producing a good if the opportunity cost of producing that good is lower in the country than it is in other countries. • A country with a comparative advantage in producing a good uses its resources most efficiently when it produces that good compared to producing other goods. 7

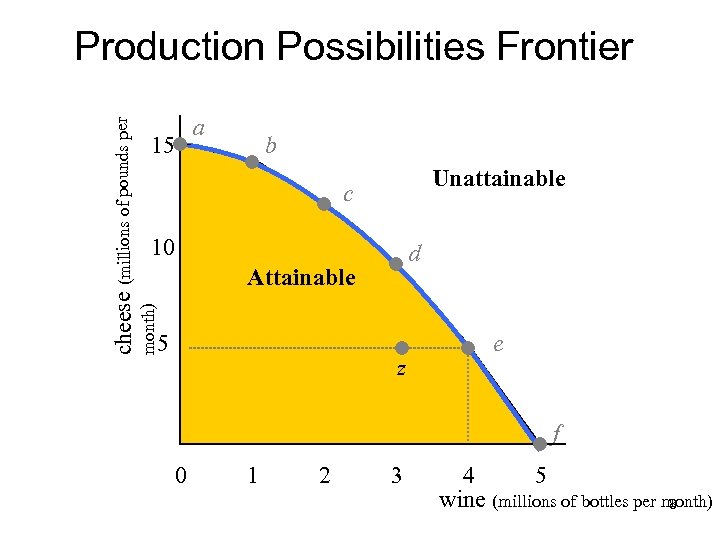

a 15 b Unattainable c 10 d Attainable month) cheese (millions of pounds per Production Possibilities Frontier 5 z e f 0 1 2 3 4 5 wine (millions of bottles per month) 8

a 15 b Unattainable c 10 d Attainable month) cheese (millions of pounds per Production Possibilities Frontier 5 z e f 0 1 2 3 4 5 wine (millions of bottles per month) 8

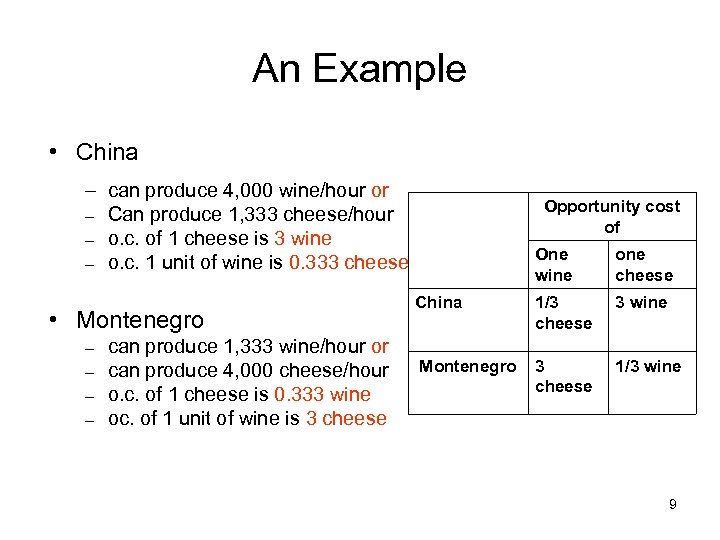

An Example • China – can produce 4, 000 wine/hour or – Can produce 1, 333 cheese/hour – o. c. of 1 cheese is 3 wine – o. c. 1 unit of wine is 0. 333 cheese • Montenegro – – can produce 1, 333 wine/hour or can produce 4, 000 cheese/hour o. c. of 1 cheese is 0. 333 wine oc. of 1 unit of wine is 3 cheese Opportunity cost of One wine one cheese China 1/3 cheese 3 wine Montenegro 3 cheese 1/3 wine 9

An Example • China – can produce 4, 000 wine/hour or – Can produce 1, 333 cheese/hour – o. c. of 1 cheese is 3 wine – o. c. 1 unit of wine is 0. 333 cheese • Montenegro – – can produce 1, 333 wine/hour or can produce 4, 000 cheese/hour o. c. of 1 cheese is 0. 333 wine oc. of 1 unit of wine is 3 cheese Opportunity cost of One wine one cheese China 1/3 cheese 3 wine Montenegro 3 cheese 1/3 wine 9

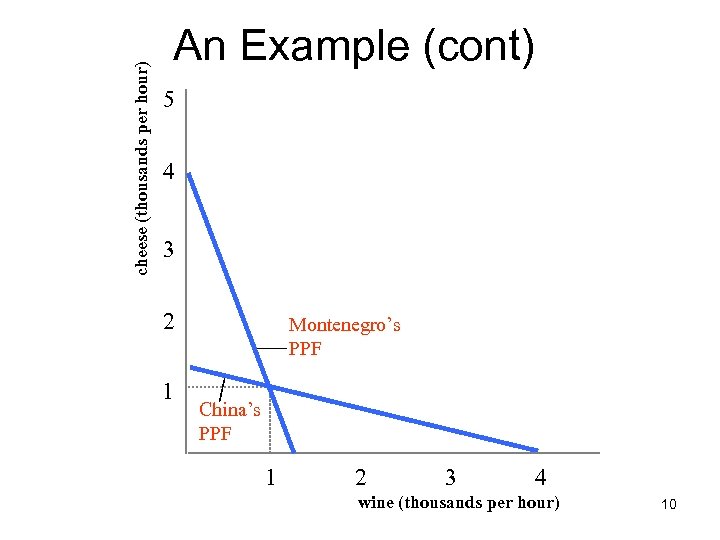

cheese (thousands per hour) An Example (cont) 5 4 3 2 1 Montenegro’s PPF China’s PPF 1 2 3 4 wine (thousands per hour) 10

cheese (thousands per hour) An Example (cont) 5 4 3 2 1 Montenegro’s PPF China’s PPF 1 2 3 4 wine (thousands per hour) 10

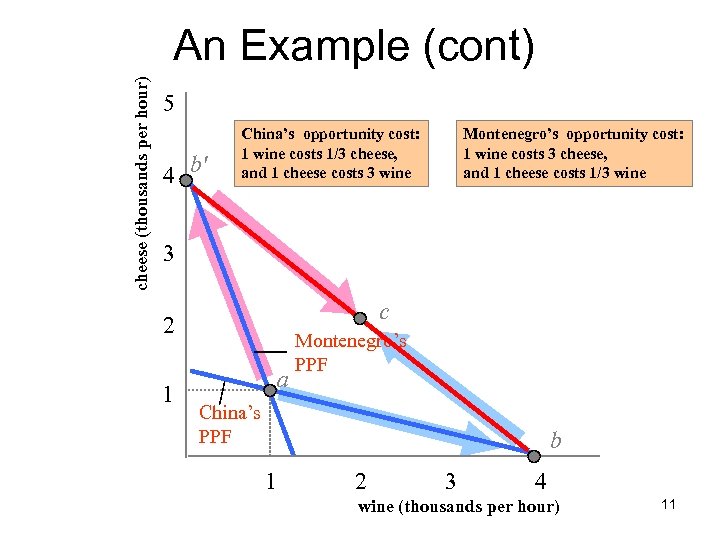

cheese (thousands per hour) An Example (cont) 5 4 b' China’s opportunity cost: 1 wine costs 1/3 cheese, and 1 cheese costs 3 wine Montenegro’s opportunity cost: 1 wine costs 3 cheese, and 1 cheese costs 1/3 wine 3 c 2 1 a Montenegro’s PPF China’s PPF b 1 2 3 4 wine (thousands per hour) 11

cheese (thousands per hour) An Example (cont) 5 4 b' China’s opportunity cost: 1 wine costs 1/3 cheese, and 1 cheese costs 3 wine Montenegro’s opportunity cost: 1 wine costs 3 cheese, and 1 cheese costs 1/3 wine 3 c 2 1 a Montenegro’s PPF China’s PPF b 1 2 3 4 wine (thousands per hour) 11

An Example (cont. ) • China has comparative advantage in producing wine, and Montenegro has c. a. in producing cheese. • China specializes in wine production and Montenegro in cheese production. • Both countries are better off by engaging in international trade! 12

An Example (cont. ) • China has comparative advantage in producing wine, and Montenegro has c. a. in producing cheese. • China specializes in wine production and Montenegro in cheese production. • Both countries are better off by engaging in international trade! 12

An Example (cont) • China—the country with absolute cost disadvantage—can benefit from trade • Montenegro—the country with absolute cost advantage—can benefit from trade too • But how much exactly do they produce? At what prices? 13

An Example (cont) • China—the country with absolute cost disadvantage—can benefit from trade • Montenegro—the country with absolute cost advantage—can benefit from trade too • But how much exactly do they produce? At what prices? 13

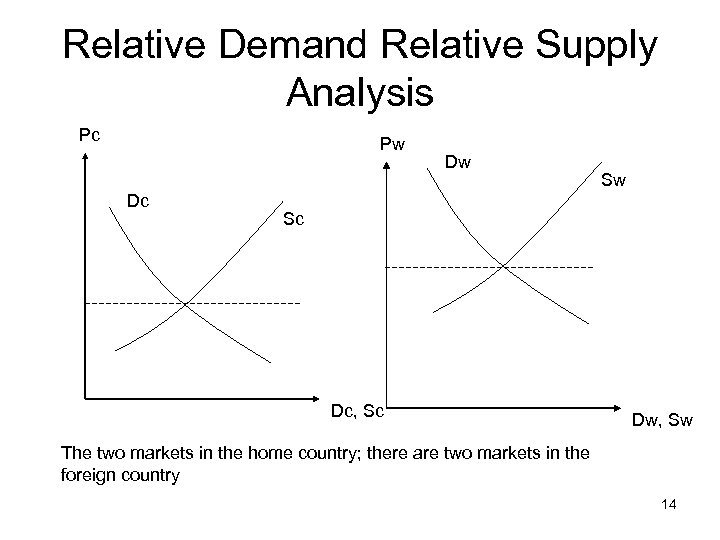

Relative Demand Relative Supply Analysis Pc Pw Dc Dw Sw Sc Dc, Sc Dw, Sw The two markets in the home country; there are two markets in the foreign country 14

Relative Demand Relative Supply Analysis Pc Pw Dc Dw Sw Sc Dc, Sc Dw, Sw The two markets in the home country; there are two markets in the foreign country 14

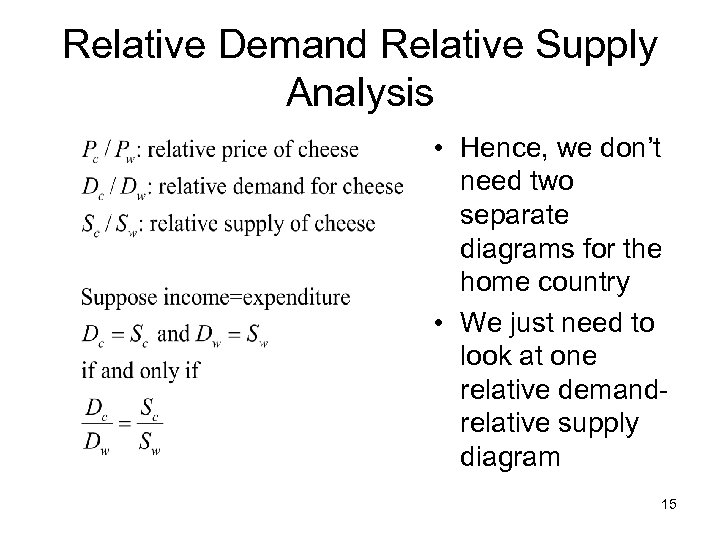

Relative Demand Relative Supply Analysis • Hence, we don’t need two separate diagrams for the home country • We just need to look at one relative demandrelative supply diagram 15

Relative Demand Relative Supply Analysis • Hence, we don’t need two separate diagrams for the home country • We just need to look at one relative demandrelative supply diagram 15

Relative Demand-Relative Supply Analysis 16

Relative Demand-Relative Supply Analysis 16

Relative Demand Relative Supply Analysis • To study the Ricardian Model, we need to clarify what the RD and RS are. • The RS is determined by the technology • The RD is determined by consumers’ preferences – The preferences to be introduced are general, applicable to other models 17

Relative Demand Relative Supply Analysis • To study the Ricardian Model, we need to clarify what the RD and RS are. • The RS is determined by the technology • The RD is determined by consumers’ preferences – The preferences to be introduced are general, applicable to other models 17

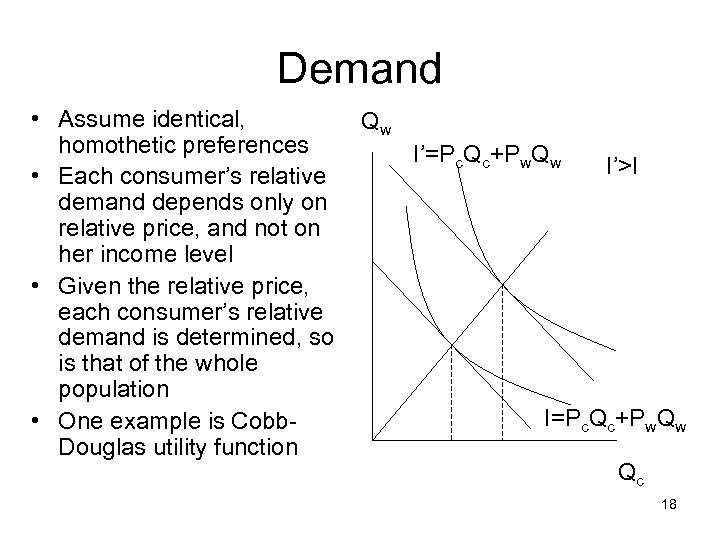

Demand • Assume identical, homothetic preferences • Each consumer’s relative demand depends only on relative price, and not on her income level • Given the relative price, each consumer’s relative demand is determined, so is that of the whole population • One example is Cobb. Douglas utility function Qw I’=Pc. Qc+Pw. Qw I’>I I=Pc. Qc+Pw. Qw Qc 18

Demand • Assume identical, homothetic preferences • Each consumer’s relative demand depends only on relative price, and not on her income level • Given the relative price, each consumer’s relative demand is determined, so is that of the whole population • One example is Cobb. Douglas utility function Qw I’=Pc. Qc+Pw. Qw I’>I I=Pc. Qc+Pw. Qw Qc 18

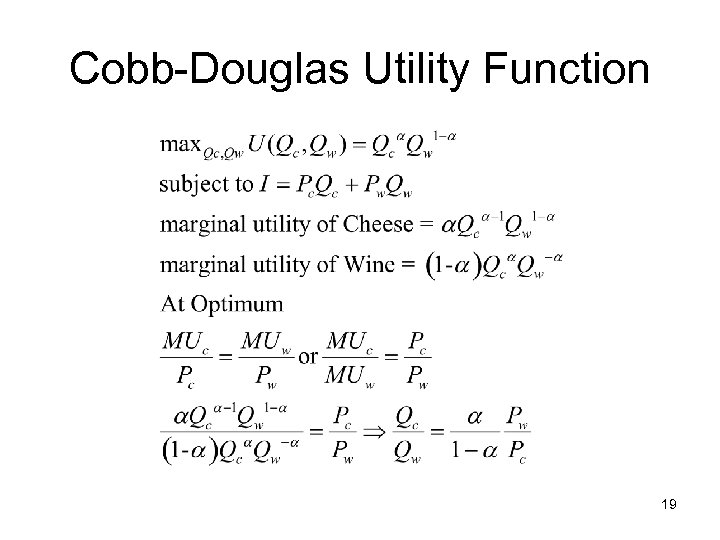

Cobb-Douglas Utility Function 19

Cobb-Douglas Utility Function 19

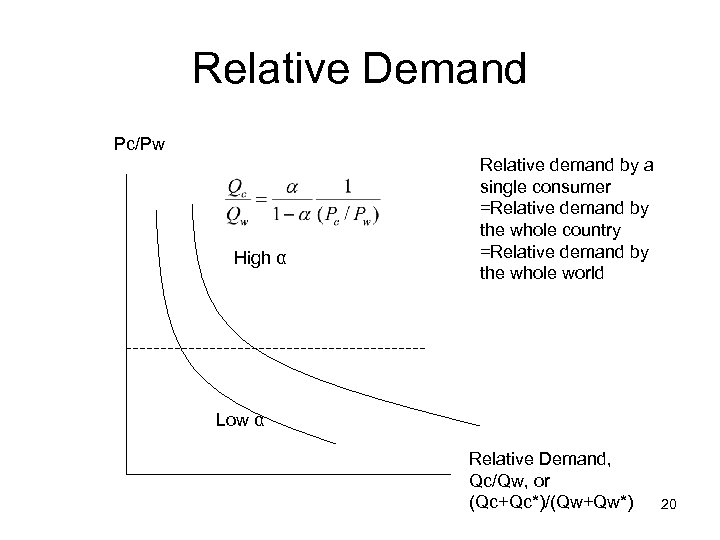

Relative Demand Pc/Pw High α Relative demand by a single consumer =Relative demand by the whole country =Relative demand by the whole world Low α Relative Demand, Qc/Qw, or (Qc+Qc*)/(Qw+Qw*) 20

Relative Demand Pc/Pw High α Relative demand by a single consumer =Relative demand by the whole country =Relative demand by the whole world Low α Relative Demand, Qc/Qw, or (Qc+Qc*)/(Qw+Qw*) 20

Relative Supply • Assume that we are dealing with an economy (which we call Home). In this economy: – – Labor is the only factor of production. Only two goods (say wine and cheese) are produced. The supply of labor is fixed in each country. The productivity of labor in each good is fixed (c. r. t. s. technology). – Perfect competition prevails in all markets. 21

Relative Supply • Assume that we are dealing with an economy (which we call Home). In this economy: – – Labor is the only factor of production. Only two goods (say wine and cheese) are produced. The supply of labor is fixed in each country. The productivity of labor in each good is fixed (c. r. t. s. technology). – Perfect competition prevails in all markets. 21

A One-Factor Economy • The unit labor requirement is the number of hours of labor required to produce one unit of output. • Denote with a. LW the unit labor requirement for wine (e. g. if a. LW = 2, then one needs 2 hours of labor to produce one gallon of wine). • Denote with a. LC the unit labor requirement for cheese (e. g. if a. LC = 1, then one needs 1 hour of labor to produce a pound of cheese). • The economy’s total resources are defined as L, the total labor supply (e. g. if L = 120, then this economy is endowed with 120 hours of labor or 120 workers). 22

A One-Factor Economy • The unit labor requirement is the number of hours of labor required to produce one unit of output. • Denote with a. LW the unit labor requirement for wine (e. g. if a. LW = 2, then one needs 2 hours of labor to produce one gallon of wine). • Denote with a. LC the unit labor requirement for cheese (e. g. if a. LC = 1, then one needs 1 hour of labor to produce a pound of cheese). • The economy’s total resources are defined as L, the total labor supply (e. g. if L = 120, then this economy is endowed with 120 hours of labor or 120 workers). 22

Relative Price and Supply • “I have a unit of labor, should I produce cheese or wine? ” • To produce cheese, I can make 1/ a. LC units and get a revenue of Pc/ a. LC. • To produce wine, I make 1/a. Lw units and hence get a revenue of Pw/ a. LW. • Hence, • If Pc/Pw> a. LC / a. LW, I should produce cheese • If Pc/Pw< a. LC / a. LW, I should produce wine • If Pc/Pw= a. LC / a. LW, I don’t mind produce any combination 23

Relative Price and Supply • “I have a unit of labor, should I produce cheese or wine? ” • To produce cheese, I can make 1/ a. LC units and get a revenue of Pc/ a. LC. • To produce wine, I make 1/a. Lw units and hence get a revenue of Pw/ a. LW. • Hence, • If Pc/Pw> a. LC / a. LW, I should produce cheese • If Pc/Pw< a. LC / a. LW, I should produce wine • If Pc/Pw= a. LC / a. LW, I don’t mind produce any combination 23

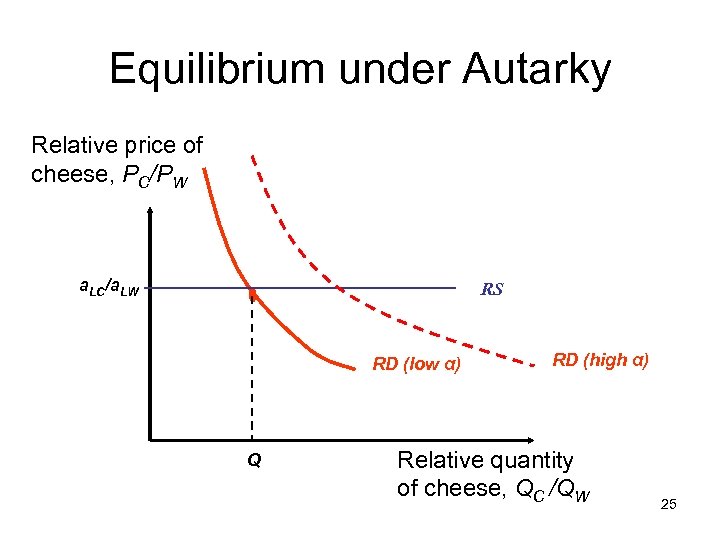

Relative Price and Supply • The above relations imply that if the relative price of cheese (PC / PW ) exceeds its opportunity cost (a. LC / a. LW), then the economy will specialize in the production of cheese. • In the absence of international trade, both goods are produced, and therefore PC / PW = a. LC /a. LW. 24

Relative Price and Supply • The above relations imply that if the relative price of cheese (PC / PW ) exceeds its opportunity cost (a. LC / a. LW), then the economy will specialize in the production of cheese. • In the absence of international trade, both goods are produced, and therefore PC / PW = a. LC /a. LW. 24

Equilibrium under Autarky Relative price of cheese, PC/PW a. LC/a. LW RS RD (low α) Q RD (high α) Relative quantity of cheese, QC /QW 25

Equilibrium under Autarky Relative price of cheese, PC/PW a. LC/a. LW RS RD (low α) Q RD (high α) Relative quantity of cheese, QC /QW 25

Trade in a One-Factor World • Assumptions of the model: – There are two countries in the world (Home and Foreign). – Each of the two countries produces two goods (say wine and cheese). – Labor is the only factor of production. – The supply of labor is fixed in each country. – The productivity of labor in each good is fixed. – Labor is not mobile across the two countries. – Perfect competition prevails in all markets. – All variables with an asterisk refer to the Foreign country. 26

Trade in a One-Factor World • Assumptions of the model: – There are two countries in the world (Home and Foreign). – Each of the two countries produces two goods (say wine and cheese). – Labor is the only factor of production. – The supply of labor is fixed in each country. – The productivity of labor in each good is fixed. – Labor is not mobile across the two countries. – Perfect competition prevails in all markets. – All variables with an asterisk refer to the Foreign country. 26

Trade in a One-Factor World • Absolute Advantage – A country has an absolute advantage in a production of a good if it has a lower unit labor requirement than the foreign country in this good. – Assume that a. LC > a*LC and a. LW > a*LW • This assumption implies that Home has an absolute disadvantage in the production of both goods. Another way to see this is to notice that Home is less productive in the production of both goods than Foreign. • Even if Home has an absolute disadvantage in both goods, beneficial trade is possible. • The pattern of trade will be determined by the concept of comparative advantage. 27

Trade in a One-Factor World • Absolute Advantage – A country has an absolute advantage in a production of a good if it has a lower unit labor requirement than the foreign country in this good. – Assume that a. LC > a*LC and a. LW > a*LW • This assumption implies that Home has an absolute disadvantage in the production of both goods. Another way to see this is to notice that Home is less productive in the production of both goods than Foreign. • Even if Home has an absolute disadvantage in both goods, beneficial trade is possible. • The pattern of trade will be determined by the concept of comparative advantage. 27

Trade in a One-Factor World • Comparative Advantage – Assume that a. LC /a. LW < a*LC /a*LW (2 -2) • In other words, in the absence of trade, the relative price of cheese at Home is lower than the relative price of cheese at Foreign. • Home has a comparative advantage in cheese and will export it to Foreign in exchange for wine. 28

Trade in a One-Factor World • Comparative Advantage – Assume that a. LC /a. LW < a*LC /a*LW (2 -2) • In other words, in the absence of trade, the relative price of cheese at Home is lower than the relative price of cheese at Foreign. • Home has a comparative advantage in cheese and will export it to Foreign in exchange for wine. 28

Trade in a One-Factor World • Determining the Relative Price After Trade – What determines the relative price (e. g. , PC / PW) after trade? • To answer this question we have to define the relative supply and relative demand for cheese in the world as a whole. • The relative supply of cheese equals the total quantity of cheese supplied by both countries at each given relative price divided by the total quantity of wine supplied, (QC + Q*C )/(QW + Q*W). • The relative demand of cheese in the world is a similar concept. 29

Trade in a One-Factor World • Determining the Relative Price After Trade – What determines the relative price (e. g. , PC / PW) after trade? • To answer this question we have to define the relative supply and relative demand for cheese in the world as a whole. • The relative supply of cheese equals the total quantity of cheese supplied by both countries at each given relative price divided by the total quantity of wine supplied, (QC + Q*C )/(QW + Q*W). • The relative demand of cheese in the world is a similar concept. 29

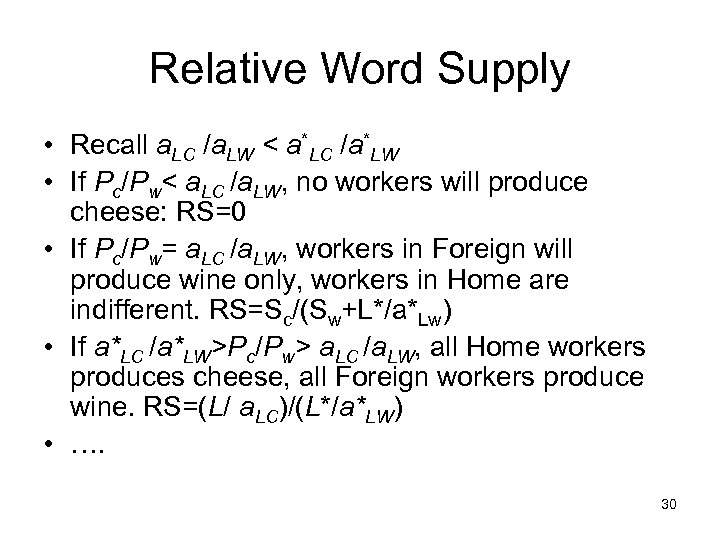

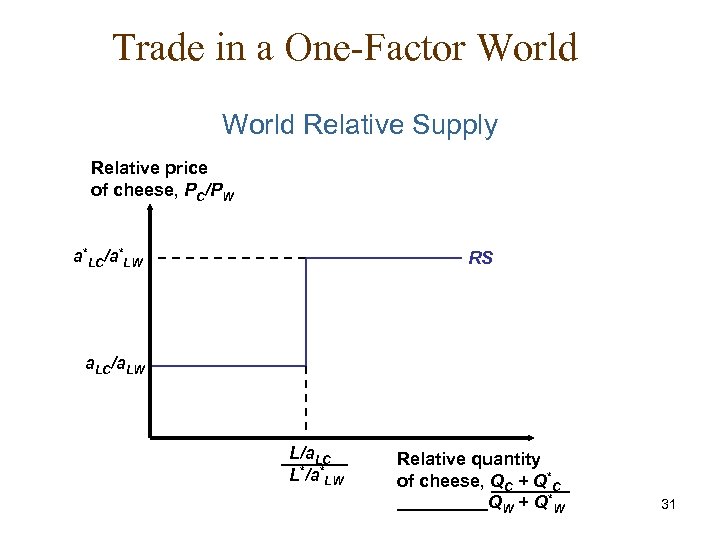

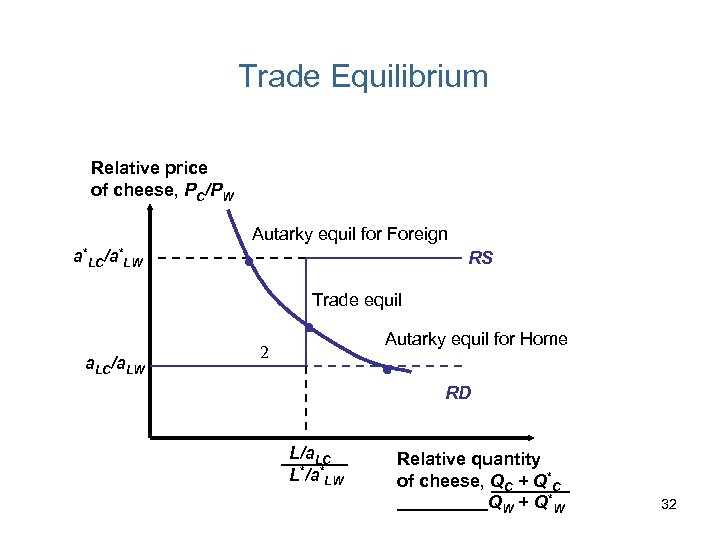

Relative Word Supply • Recall a. LC /a. LW < a*LC /a*LW • If Pc/Pw< a. LC /a. LW, no workers will produce cheese: RS=0 • If Pc/Pw= a. LC /a. LW, workers in Foreign will produce wine only, workers in Home are indifferent. RS=Sc/(Sw+L*/a*Lw) • If a*LC /a*LW>Pc/Pw> a. LC /a. LW, all Home workers produces cheese, all Foreign workers produce wine. RS=(L/ a. LC)/(L*/a*LW) • …. 30

Relative Word Supply • Recall a. LC /a. LW < a*LC /a*LW • If Pc/Pw< a. LC /a. LW, no workers will produce cheese: RS=0 • If Pc/Pw= a. LC /a. LW, workers in Foreign will produce wine only, workers in Home are indifferent. RS=Sc/(Sw+L*/a*Lw) • If a*LC /a*LW>Pc/Pw> a. LC /a. LW, all Home workers produces cheese, all Foreign workers produce wine. RS=(L/ a. LC)/(L*/a*LW) • …. 30

Trade in a One-Factor World Relative Supply Relative price of cheese, PC/PW a*LC/a*LW RS a. LC/a. LW L/a. LC L*/a*LW Relative quantity of cheese, QC + Q*C Q W + Q *W 31

Trade in a One-Factor World Relative Supply Relative price of cheese, PC/PW a*LC/a*LW RS a. LC/a. LW L/a. LC L*/a*LW Relative quantity of cheese, QC + Q*C Q W + Q *W 31

Trade Equilibrium Relative price of cheese, PC/PW Autarky equil for Foreign a*LC/a*LW RS Trade equil a. LC/a. LW Autarky equil for Home 2 RD L/a. LC L*/a*LW Relative quantity of cheese, QC + Q*C Q W + Q *W 32

Trade Equilibrium Relative price of cheese, PC/PW Autarky equil for Foreign a*LC/a*LW RS Trade equil a. LC/a. LW Autarky equil for Home 2 RD L/a. LC L*/a*LW Relative quantity of cheese, QC + Q*C Q W + Q *W 32

Gains from Trade • If countries specialize according to their comparative advantage, they all gain from this specialization and trade. 33

Gains from Trade • If countries specialize according to their comparative advantage, they all gain from this specialization and trade. 33

Gains from Trade • • L=L*=120 a. LC=4, a. LW=8, hence a. LC/a. LW=1/2 a*LC=2, a*LW=1, hence a*LC/a*LW=2 If free trade relative price is in between ½ and 2 • Home specializes in Cheese production. • Foreign specializes in Wine production. 34

Gains from Trade • • L=L*=120 a. LC=4, a. LW=8, hence a. LC/a. LW=1/2 a*LC=2, a*LW=1, hence a*LC/a*LW=2 If free trade relative price is in between ½ and 2 • Home specializes in Cheese production. • Foreign specializes in Wine production. 34

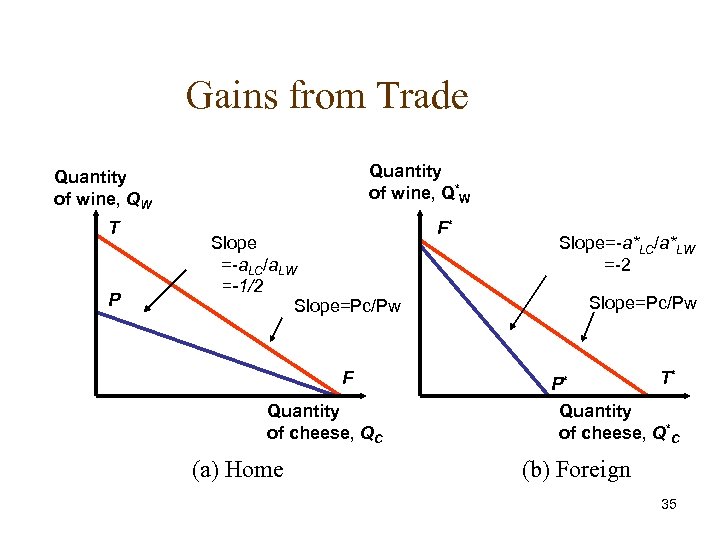

Gains from Trade Quantity of wine, Q*W Quantity of wine, QW T P Slope =-a. LC/a. LW =-1/2 Slope=Pc/Pw F Quantity of cheese, QC (a) Home F* Slope=-a*LC/a*LW =-2 Slope=Pc/Pw T* P* Quantity of cheese, Q*C (b) Foreign 35

Gains from Trade Quantity of wine, Q*W Quantity of wine, QW T P Slope =-a. LC/a. LW =-1/2 Slope=Pc/Pw F Quantity of cheese, QC (a) Home F* Slope=-a*LC/a*LW =-2 Slope=Pc/Pw T* P* Quantity of cheese, Q*C (b) Foreign 35

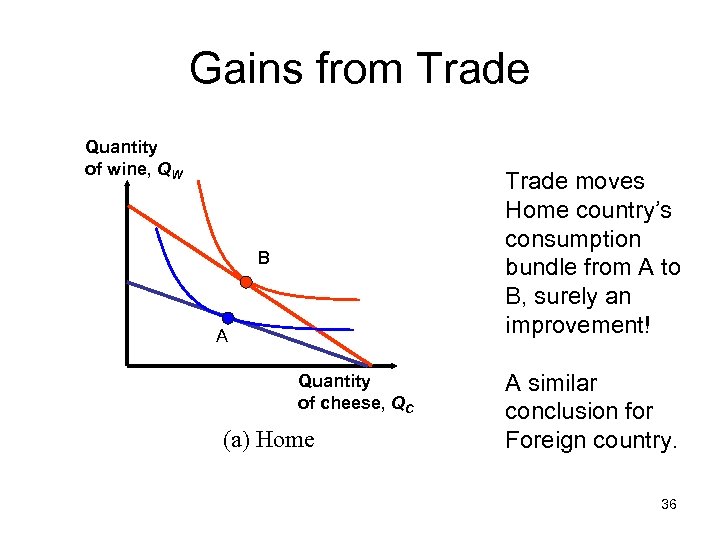

Gains from Trade Quantity of wine, QW Trade moves Home country’s consumption bundle from A to B, surely an improvement! B A Quantity of cheese, QC (a) Home A similar conclusion for Foreign country. 36

Gains from Trade Quantity of wine, QW Trade moves Home country’s consumption bundle from A to B, surely an improvement! B A Quantity of cheese, QC (a) Home A similar conclusion for Foreign country. 36

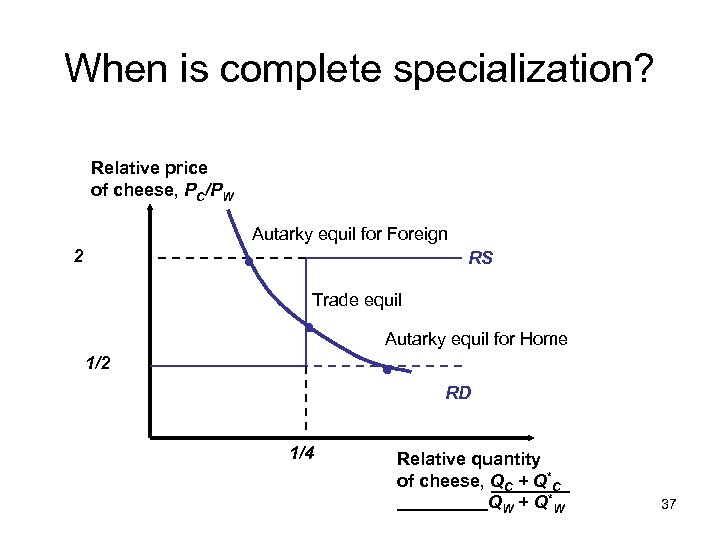

When is complete specialization? Relative price of cheese, PC/PW Autarky equil for Foreign 2 RS Trade equil Autarky equil for Home 1/2 RD 1/4 Relative quantity of cheese, QC + Q*C Q W + Q *W 37

When is complete specialization? Relative price of cheese, PC/PW Autarky equil for Foreign 2 RS Trade equil Autarky equil for Home 1/2 RD 1/4 Relative quantity of cheese, QC + Q*C Q W + Q *W 37

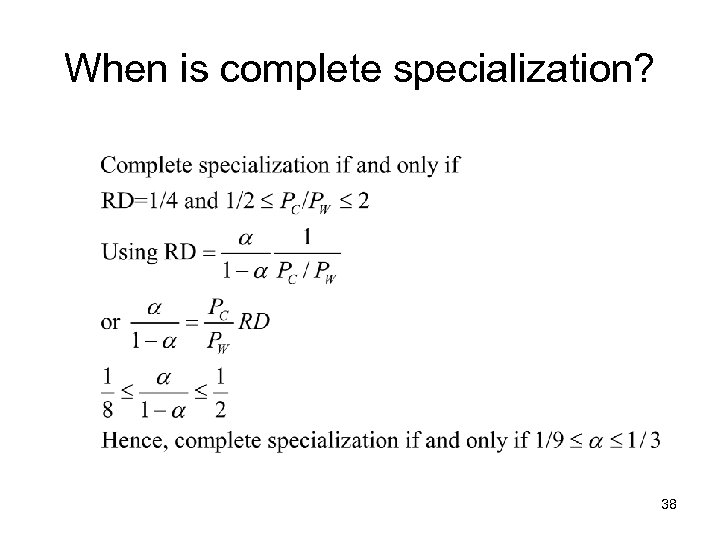

When is complete specialization? 38

When is complete specialization? 38

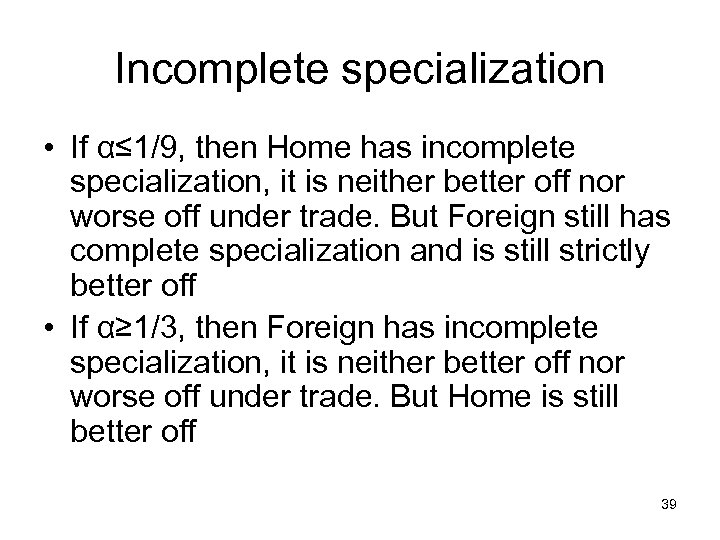

Incomplete specialization • If α≤ 1/9, then Home has incomplete specialization, it is neither better off nor worse off under trade. But Foreign still has complete specialization and is still strictly better off • If α≥ 1/3, then Foreign has incomplete specialization, it is neither better off nor worse off under trade. But Home is still better off 39

Incomplete specialization • If α≤ 1/9, then Home has incomplete specialization, it is neither better off nor worse off under trade. But Foreign still has complete specialization and is still strictly better off • If α≥ 1/3, then Foreign has incomplete specialization, it is neither better off nor worse off under trade. But Home is still better off 39

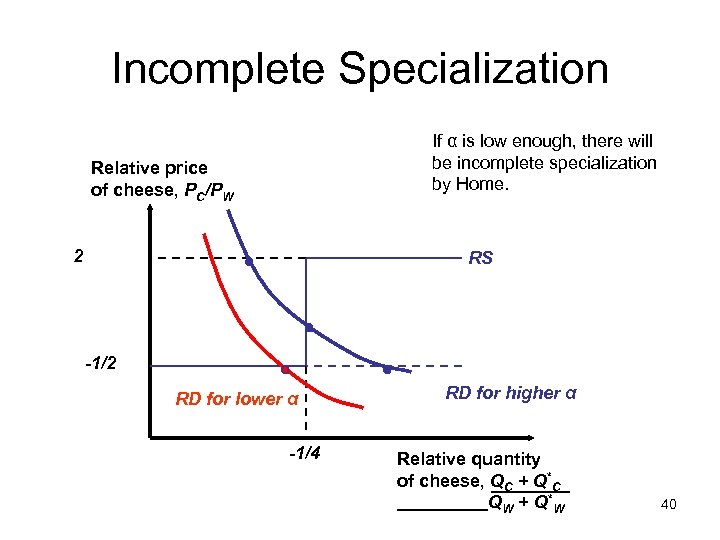

Incomplete Specialization If α is low enough, there will be incomplete specialization by Home. Relative price of cheese, PC/PW 2 RS -1/2 RD for lower α -1/4 RD for higher α Relative quantity of cheese, QC + Q*C Q W + Q *W 40

Incomplete Specialization If α is low enough, there will be incomplete specialization by Home. Relative price of cheese, PC/PW 2 RS -1/2 RD for lower α -1/4 RD for higher α Relative quantity of cheese, QC + Q*C Q W + Q *W 40

Wages • Relative Wages – Because there are technological differences between the two countries, trade in goods does not make the wages equal across the two countries. – A country with absolute advantage in both goods will enjoy a higher wage after trade. 41

Wages • Relative Wages – Because there are technological differences between the two countries, trade in goods does not make the wages equal across the two countries. – A country with absolute advantage in both goods will enjoy a higher wage after trade. 41

Wages – This can be illustrated with the help of a numerical example: • Assume that PC = $12 and that PW = $12. Therefore, we have PC / PW = 1. • Since Home specializes in cheese after trade, its wage will be (1/a. LC)PC = ( 1/4)$12 = $3. • Since Foreign specializes in wine after trade, its wage will be (1/a*LW) PW = (1/1)$12 = $12. • Therefore the relative wage of Home will be $3/$12 = 1/4. • Thus, the country with the higher absolute advantage will enjoy a higher wage after trade. 42

Wages – This can be illustrated with the help of a numerical example: • Assume that PC = $12 and that PW = $12. Therefore, we have PC / PW = 1. • Since Home specializes in cheese after trade, its wage will be (1/a. LC)PC = ( 1/4)$12 = $3. • Since Foreign specializes in wine after trade, its wage will be (1/a*LW) PW = (1/1)$12 = $12. • Therefore the relative wage of Home will be $3/$12 = 1/4. • Thus, the country with the higher absolute advantage will enjoy a higher wage after trade. 42

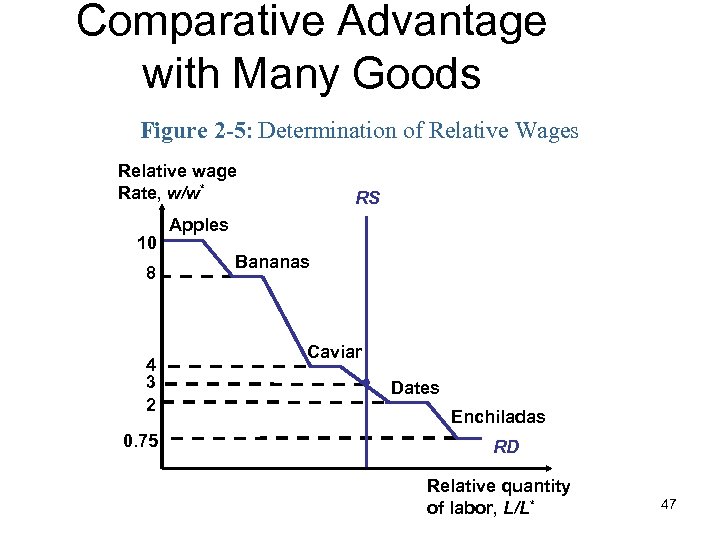

Comparative Advantage with Many Goods • Setting Up the Model – Both countries consume and are able to produce a large number, N, of different goods. • Relative Wages and Specialization – The pattern of trade will depend on the ratio of Home to Foreign wages. – Goods will always be produced where it is cheapest to make them. • For example, it will be cheaper to produce good i in Home if wa. Li < w*a*Li , or by rearranging if a*Li/a. Li >43 w/w*.

Comparative Advantage with Many Goods • Setting Up the Model – Both countries consume and are able to produce a large number, N, of different goods. • Relative Wages and Specialization – The pattern of trade will depend on the ratio of Home to Foreign wages. – Goods will always be produced where it is cheapest to make them. • For example, it will be cheaper to produce good i in Home if wa. Li < w*a*Li , or by rearranging if a*Li/a. Li >43 w/w*.

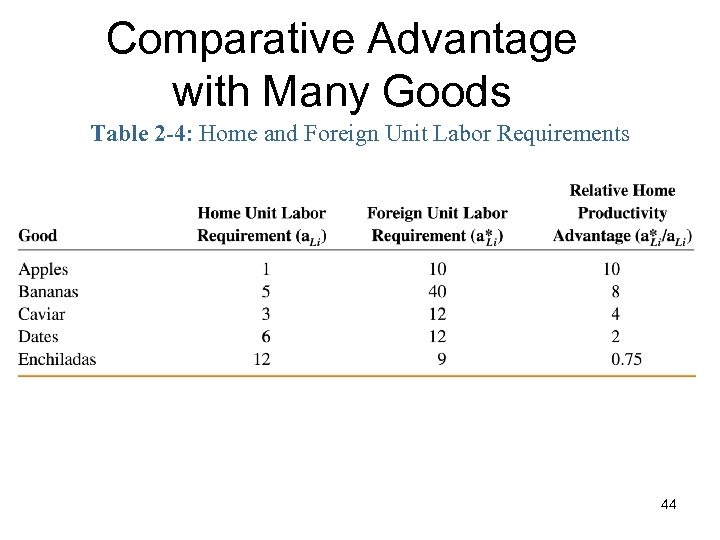

Comparative Advantage with Many Goods Table 2 -4: Home and Foreign Unit Labor Requirements 44

Comparative Advantage with Many Goods Table 2 -4: Home and Foreign Unit Labor Requirements 44

Comparative Advantage with Many Goods • Which country produces which goods? – A country has a cost advantage in any good for which its relative productivity is higher than its relative wage. • If, for example, w/w* = 3, Home will produce apples, bananas, and caviar, while Foreign will produce only dates and enchiladas. • Both countries will gain from this specialization. 45

Comparative Advantage with Many Goods • Which country produces which goods? – A country has a cost advantage in any good for which its relative productivity is higher than its relative wage. • If, for example, w/w* = 3, Home will produce apples, bananas, and caviar, while Foreign will produce only dates and enchiladas. • Both countries will gain from this specialization. 45

Comparative Advantage with Many Goods • Determining the Relative Wage in the Multigood Model – To determine relative wages in a multigood economy we must look behind the relative demand for goods (i. e. , the relative derived demand). – The relative demand for Home labor depends negatively on the ratio of Home to Foreign wages. 46

Comparative Advantage with Many Goods • Determining the Relative Wage in the Multigood Model – To determine relative wages in a multigood economy we must look behind the relative demand for goods (i. e. , the relative derived demand). – The relative demand for Home labor depends negatively on the ratio of Home to Foreign wages. 46

Comparative Advantage with Many Goods Figure 2 -5: Determination of Relative Wages Relative wage Rate, w/w* 10 8 4 3 2 0. 75 RS Apples Bananas Caviar Dates Enchiladas RD Relative quantity of labor, L/L* 47

Comparative Advantage with Many Goods Figure 2 -5: Determination of Relative Wages Relative wage Rate, w/w* 10 8 4 3 2 0. 75 RS Apples Bananas Caviar Dates Enchiladas RD Relative quantity of labor, L/L* 47

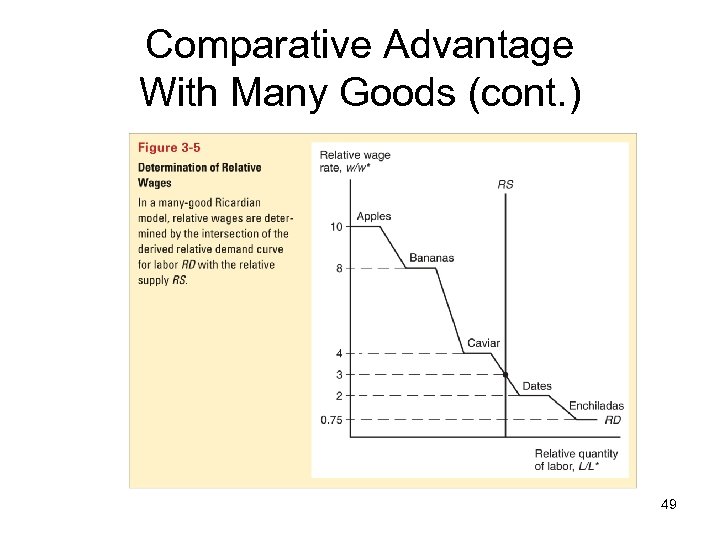

Comparative Advantage With Many Goods (cont. ) • Finally, suppose that relative supply of labor is independent of w/w* and is fixed at an amount determined by the populations in the domestic and foreign countries. 48

Comparative Advantage With Many Goods (cont. ) • Finally, suppose that relative supply of labor is independent of w/w* and is fixed at an amount determined by the populations in the domestic and foreign countries. 48

Comparative Advantage With Many Goods (cont. ) 49

Comparative Advantage With Many Goods (cont. ) 49

Transportation Costs and Non-traded Goods • The Ricardian model predicts that countries should completely specialize in production. • But this rarely happens for primarily 3 reasons: 1. More than one factor of production reduces the tendency of specialization (chapter 4) 2. Protectionism (chapters 8– 11) 3. Transportation costs reduce or prevent trade, which may cause each country to produce the same good or service 50

Transportation Costs and Non-traded Goods • The Ricardian model predicts that countries should completely specialize in production. • But this rarely happens for primarily 3 reasons: 1. More than one factor of production reduces the tendency of specialization (chapter 4) 2. Protectionism (chapters 8– 11) 3. Transportation costs reduce or prevent trade, which may cause each country to produce the same good or service 50

Transportation Costs and Non-traded Goods (cont. ) • Non-traded goods and services (e. g. , haircuts and auto repairs) exist due to high transportation costs. – Countries tend to spend a large fraction of national income on non-traded goods and services. – This fact has implications for the gravity model and for models that consider how income transfers across countries affect trade. 51

Transportation Costs and Non-traded Goods (cont. ) • Non-traded goods and services (e. g. , haircuts and auto repairs) exist due to high transportation costs. – Countries tend to spend a large fraction of national income on non-traded goods and services. – This fact has implications for the gravity model and for models that consider how income transfers across countries affect trade. 51

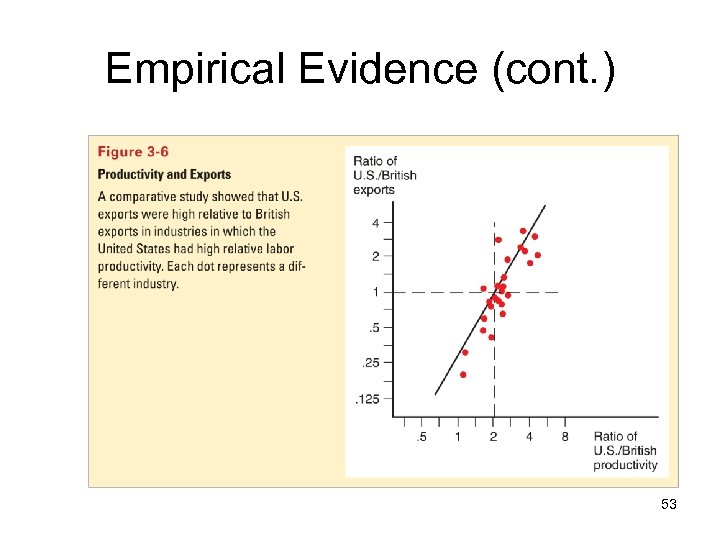

Empirical Evidence • Do countries export those goods in which their productivity is relatively high? • The ratio of US to British exports in 1951 compared to the ratio of US to British labor productivity in 26 manufacturing industries suggests yes. • At this time the US had an absolute advantage in all 26 industries, yet the ratio of exports was low in the least productive sectors of the US. 52

Empirical Evidence • Do countries export those goods in which their productivity is relatively high? • The ratio of US to British exports in 1951 compared to the ratio of US to British labor productivity in 26 manufacturing industries suggests yes. • At this time the US had an absolute advantage in all 26 industries, yet the ratio of exports was low in the least productive sectors of the US. 52

Empirical Evidence (cont. ) 53

Empirical Evidence (cont. ) 53

Summary 1. A country has a comparative advantage in producing a good if the opportunity cost of producing that good is lower in the country than it is in other countries. – A country with a comparative advantage in producing a good uses its resources most efficiently when it produces that good compared to producing other goods. 2. The Ricardian model focuses only on differences in the productivity of labor across countries, and it explains gains from trade using the concept of comparative advantage. 54

Summary 1. A country has a comparative advantage in producing a good if the opportunity cost of producing that good is lower in the country than it is in other countries. – A country with a comparative advantage in producing a good uses its resources most efficiently when it produces that good compared to producing other goods. 2. The Ricardian model focuses only on differences in the productivity of labor across countries, and it explains gains from trade using the concept of comparative advantage. 54

Summary (cont. ) 3. When countries specialize and trade according to the Ricardian model; the relative price of the produced good rises, income for workers rises and imported goods are less expensive for consumers. 4. Trade is predicted to benefit both high productivity and low productivity countries, although trade may change the distribution of income within countries. 5. High productivity or low wages give countries a cost advantage that allow them to produce efficiently. 55

Summary (cont. ) 3. When countries specialize and trade according to the Ricardian model; the relative price of the produced good rises, income for workers rises and imported goods are less expensive for consumers. 4. Trade is predicted to benefit both high productivity and low productivity countries, although trade may change the distribution of income within countries. 5. High productivity or low wages give countries a cost advantage that allow them to produce efficiently. 55

Summary (cont. ) 7. Although empirical evidence supports trade based on comparative advantage, transportation costs and other factors prevent complete specialization in production. 56

Summary (cont. ) 7. Although empirical evidence supports trade based on comparative advantage, transportation costs and other factors prevent complete specialization in production. 56