a4e82aa6d05ecfe5f1413fabb3edaac6.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 59

Chapter 2 Summary

Overview • Numbers – Decimal, Binary, Octal, Hexadecimal – Their relationship • • Sign-magnitude One’s complement Two’s complement Arithmetic operation

Positive Numbers • A computer represents positive integers in binary • Three methods for representing negative numbers (signed numbers) are – Sign-magnitude – One’s complement – Two’s complement

Sign Magnitude • Representation the number’s sign and magnitude (value) • Sign -- Positive numbers 0 and negative numbers 1 • e. g. 01000000 = 64 and 11000000 = -64 • Easy for human to understand but it requires some special logic for arithmetic operations (addition, subtraction)

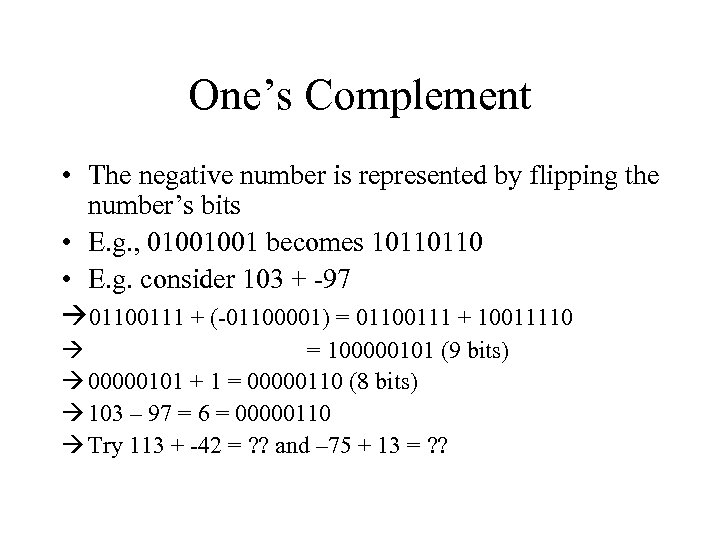

One’s Complement • The negative number is represented by flipping the number’s bits • E. g. , 01001001 becomes 10110110 • E. g. consider 103 + -97 01100111 + (-01100001) = 01100111 + 10011110 = 100000101 (9 bits) 00000101 + 1 = 00000110 (8 bits) 103 – 97 = 6 = 00000110 Try 113 + -42 = ? ? and – 75 + 13 = ? ?

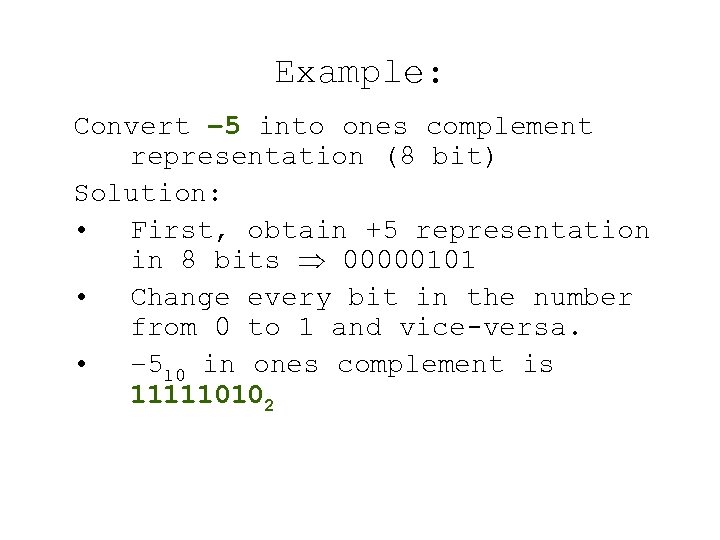

Example: Convert – 5 into ones complement representation (8 bit) Solution: • First, obtain +5 representation in 8 bits 00000101 • Change every bit in the number from 0 to 1 and vice-versa. • – 510 in ones complement is 111110102

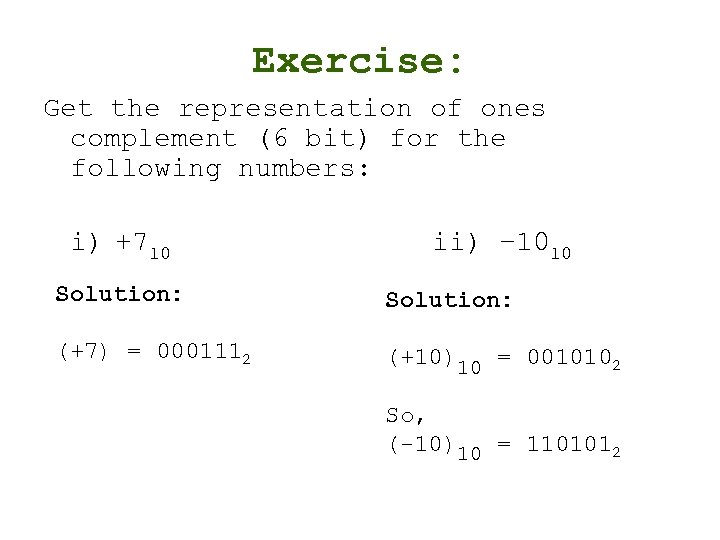

Exercise: Get the representation of ones complement (6 bit) for the following numbers: i) +710 ii) – 1010 Solution: (+7) = 0001112 (+10)10 = 0010102 So, (-10)10 = 1101012

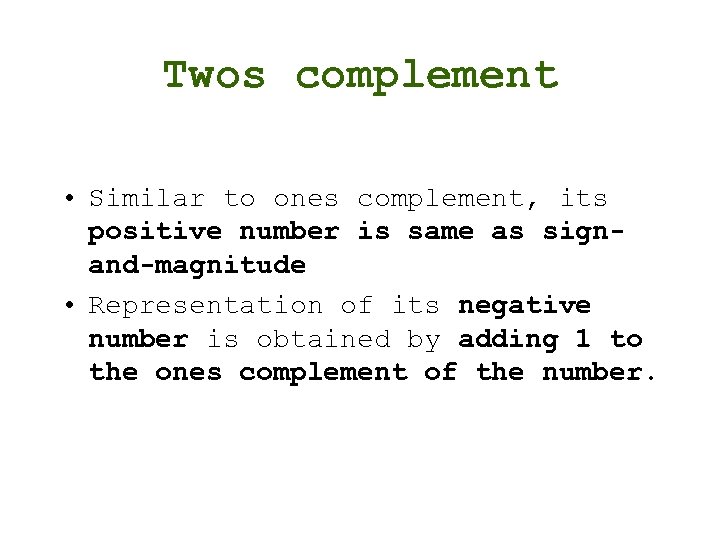

Twos complement • Similar to ones complement, its positive number is same as signand-magnitude • Representation of its negative number is obtained by adding 1 to the ones complement of the number.

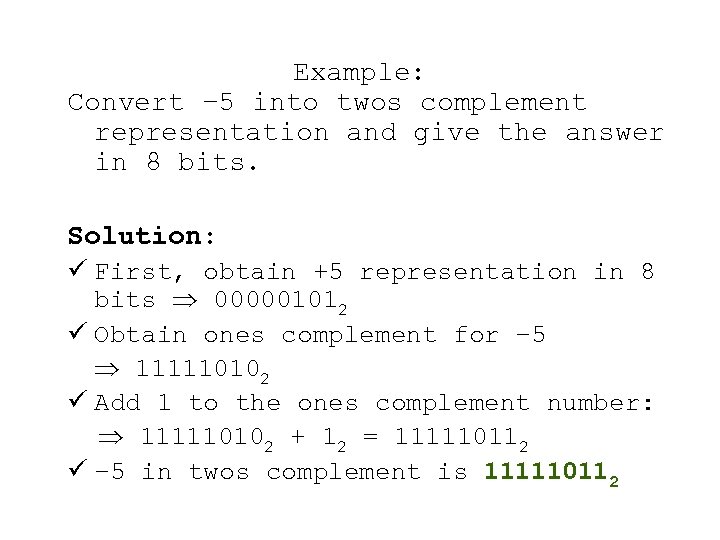

Example: Convert – 5 into twos complement representation and give the answer in 8 bits. Solution: ü First, obtain +5 representation in 8 bits 000001012 ü Obtain ones complement for – 5 111110102 ü Add 1 to the ones complement number: 111110102 + 12 = 111110112 ü – 5 in twos complement is 111110112

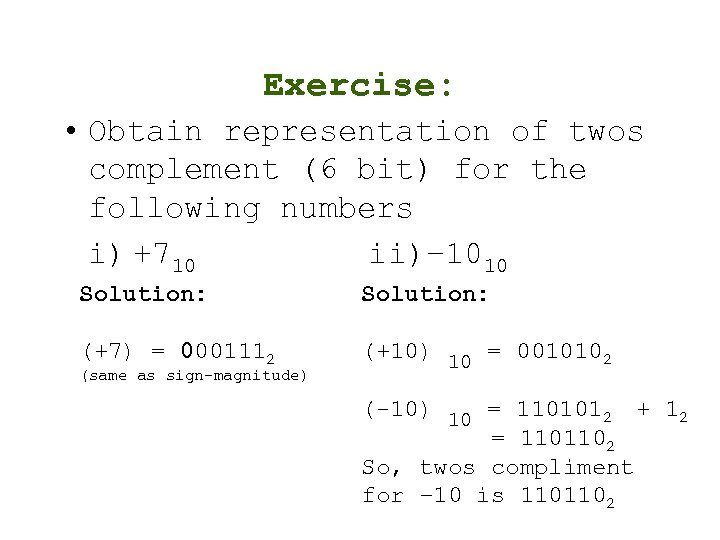

Exercise: • Obtain representation of twos complement (6 bit) for the following numbers i) +710 ii)– 1010 Solution: (+7) = 0001112 (+10) 10 = 0010102 (same as sign-magnitude) (-10) 10 = 1101012 + 12 = 1101102 So, twos compliment for – 10 is 1101102

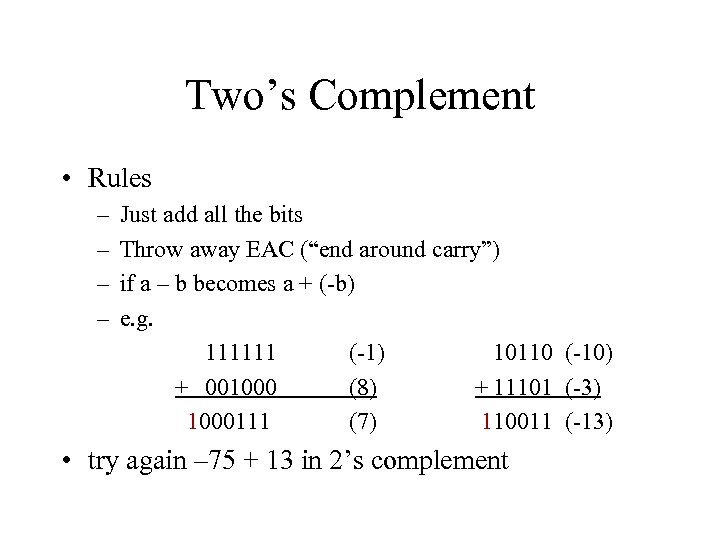

Two’s Complement • Rules – – Just add all the bits Throw away EAC (“end around carry”) if a – b becomes a + (-b) e. g. 111111 (-1) 10110 (-10) + 001000 (8) + 11101 (-3) 1000111 (7) 110011 (-13) • try again – 75 + 13 in 2’s complement

Chapter 3 Summary

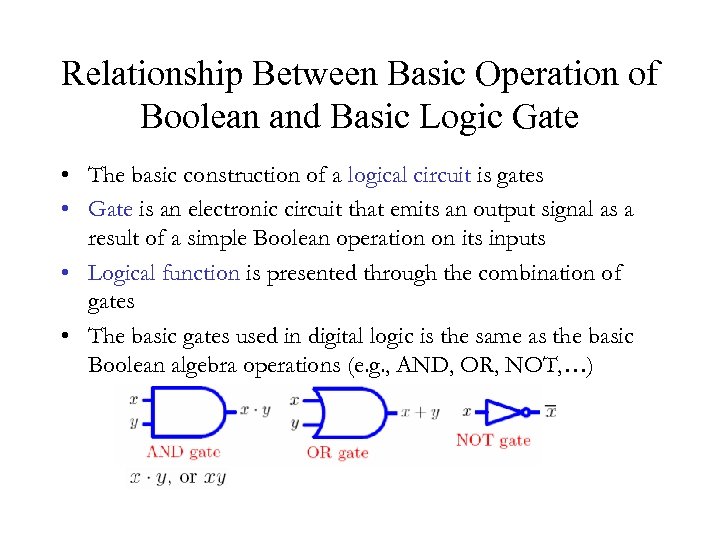

Relationship Between Basic Operation of Boolean and Basic Logic Gate • The basic construction of a logical circuit is gates • Gate is an electronic circuit that emits an output signal as a result of a simple Boolean operation on its inputs • Logical function is presented through the combination of gates • The basic gates used in digital logic is the same as the basic Boolean algebra operations (e. g. , AND, OR, NOT, …)

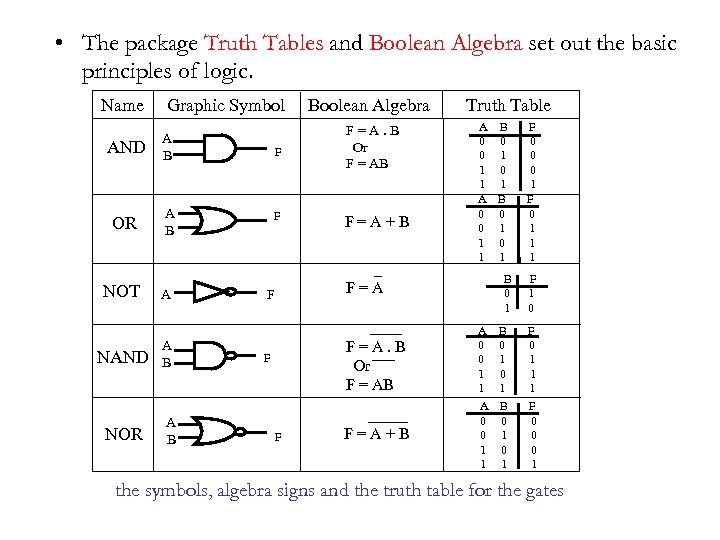

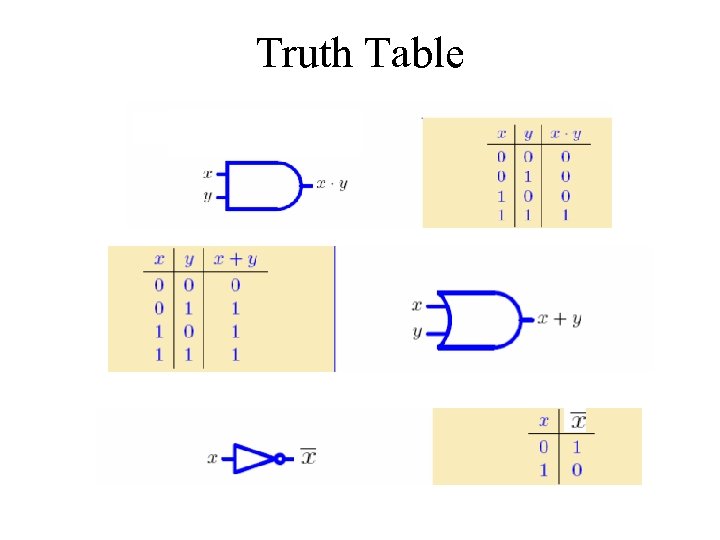

• The package Truth Tables and Boolean Algebra set out the basic principles of logic. Name Graphic Symbol Boolean Algebra Truth Table AND A B F F = A. B Or F = AB OR A B F F = A + B NOT NAND NOR A A B _ F = A F ____ F = A. B Or F = AB F F _____ F = A + B A B F 0 0 1 0 0 1 1 1 A B F 0 0 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 1 B F 0 1 1 0 A B F 0 0 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 1 A B F 0 0 1 0 0 1 1 1 the symbols, algebra signs and the truth table for the gates

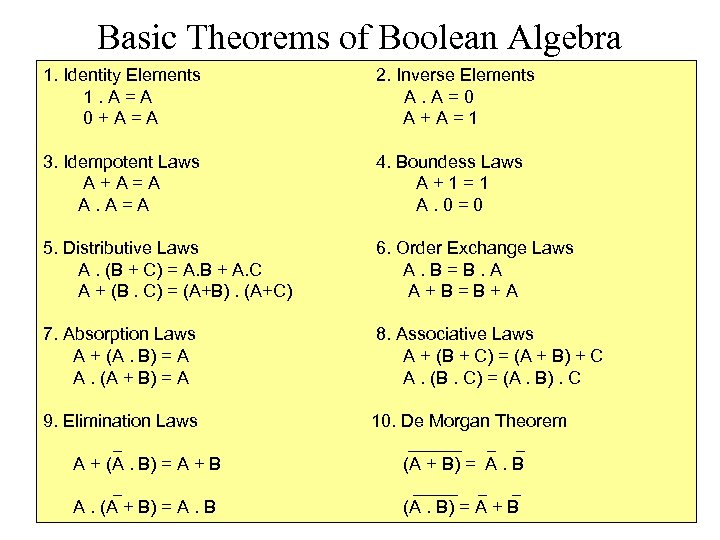

Basic Theorems of Boolean Algebra 1. Identity Elements 2. Inverse Elements 1. A = A A. A = 0 0 + A = A A + A = 1 3. Idempotent Laws 4. Boundess Laws A + A = A A + 1 = 1 A. A = A A. 0 = 0 5. Distributive Laws 6. Order Exchange Laws A. (B + C) = A. B + A. C A. B = B. A A + (B. C) = (A+B). (A+C) A + B = B + A 7. Absorption Laws 8. Associative Laws A + (A. B) = A A + (B + C) = (A + B) + C A. (A + B) = A A. (B. C) = (A. B). C 9. Elimination Laws 10. De Morgan Theorem A + (A. B) = A + B (A + B) = A. B A. (A + B) = A. B (A. B) = A + B

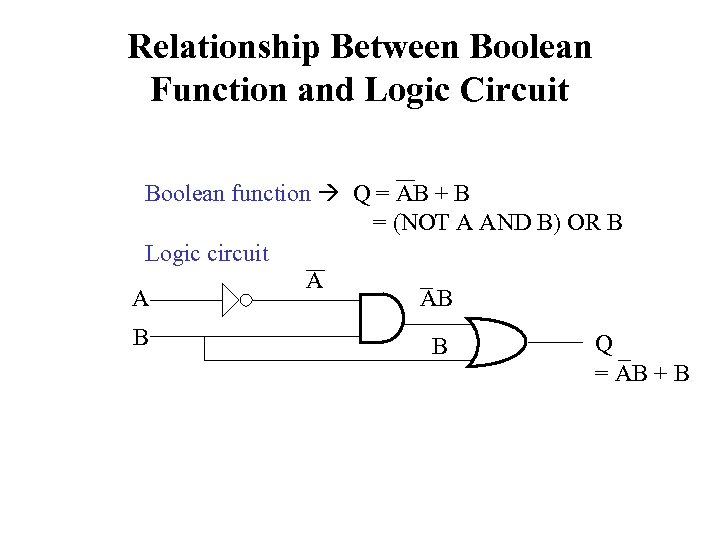

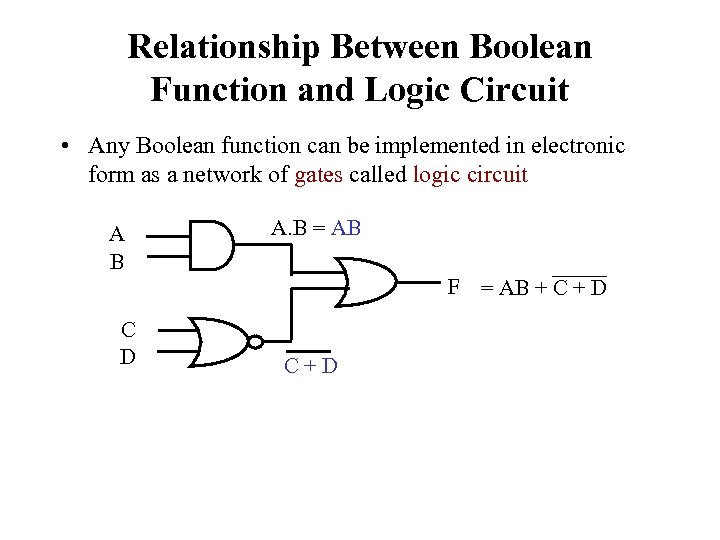

Relationship Between Boolean Function and Logic Circuit Boolean function Q = AB + B = (NOT A AND B) OR B Logic circuit A A AB B B Q = AB + B

Relationship Between Boolean Function and Logic Circuit • Any Boolean function can be implemented in electronic form as a network of gates called logic circuit A B A. B = AB F = AB + C + D

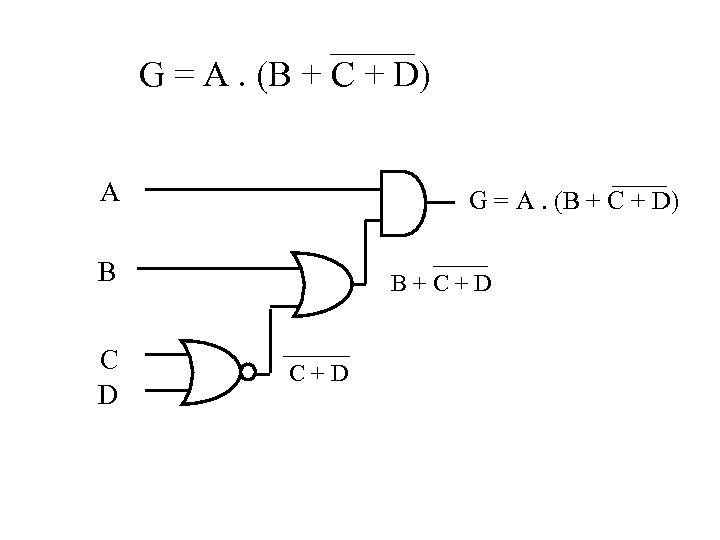

G = A. (B + C + D) A G = A. (B + C + D) B C D B + C + D

Truth Table

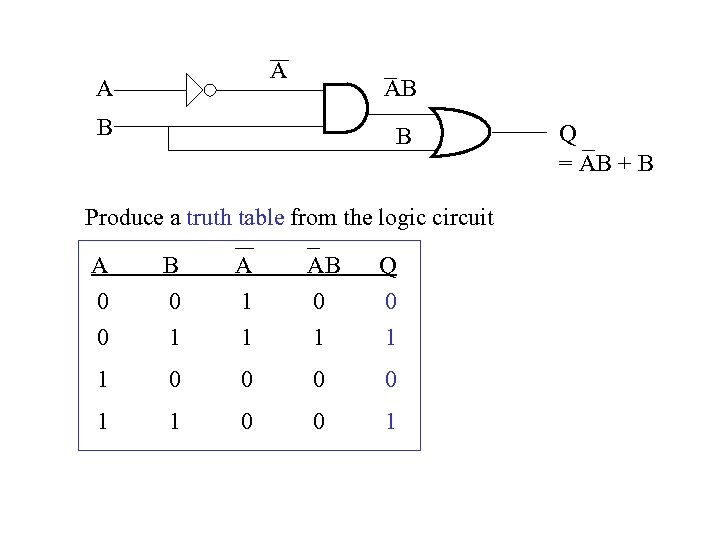

A A AB B B Produce a truth table from the logic circuit A 0 0 B 0 1 A 1 1 AB 0 1 Q 0 1 1 0 0 1 Q = AB + B

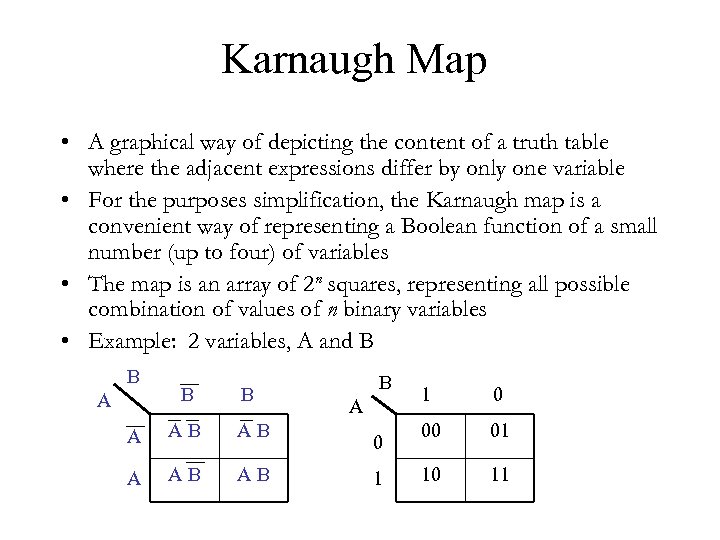

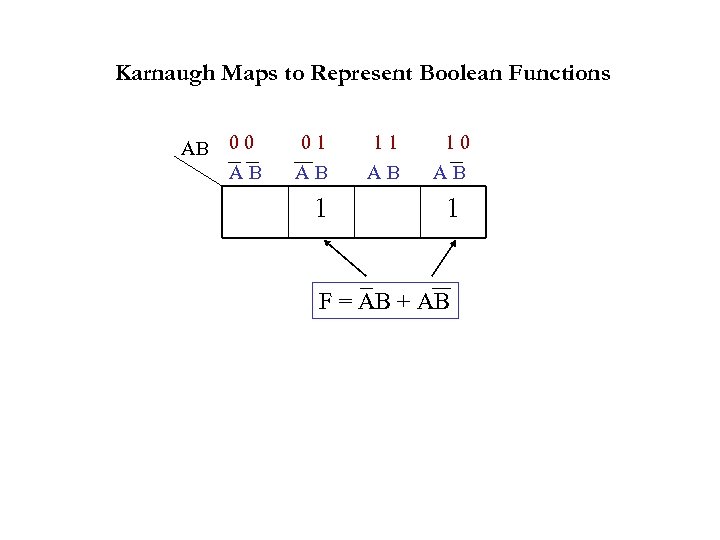

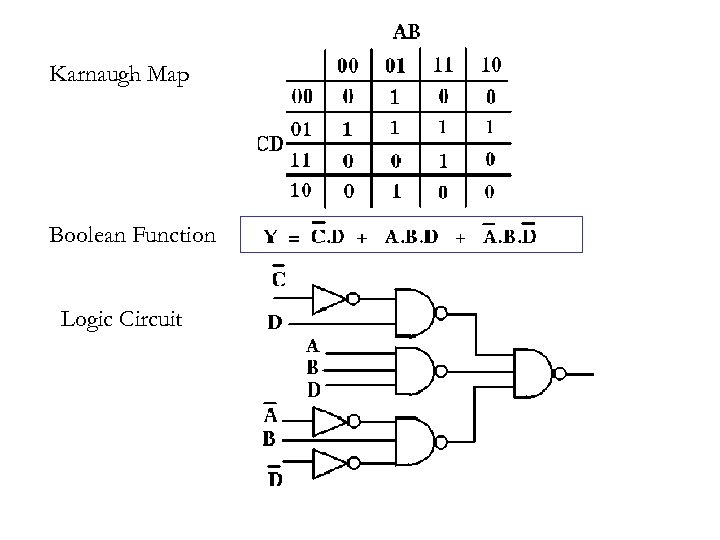

Karnaugh Map • A graphical way of depicting the content of a truth table where the adjacent expressions differ by only one variable • For the purposes simplification, the Karnaugh map is a convenient way of representing a Boolean function of a small number (up to four) of variables • The map is an array of 2 n squares, representing all possible combination of values of n binary variables • Example: 2 variables, A and B B A A B A B A B A 0 1 1 0 00 01 10 11

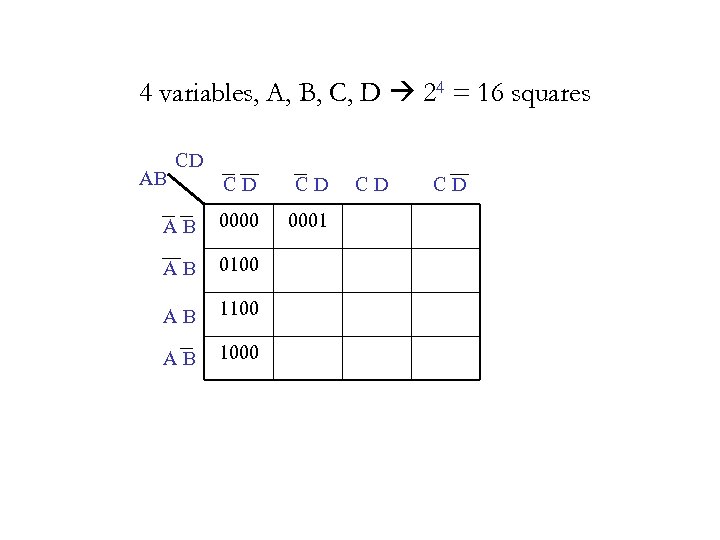

4 variables, A, B, C, D 24 = 16 squares AB CD C D A B 0000 0001 A B 0100 A B 1000 C D

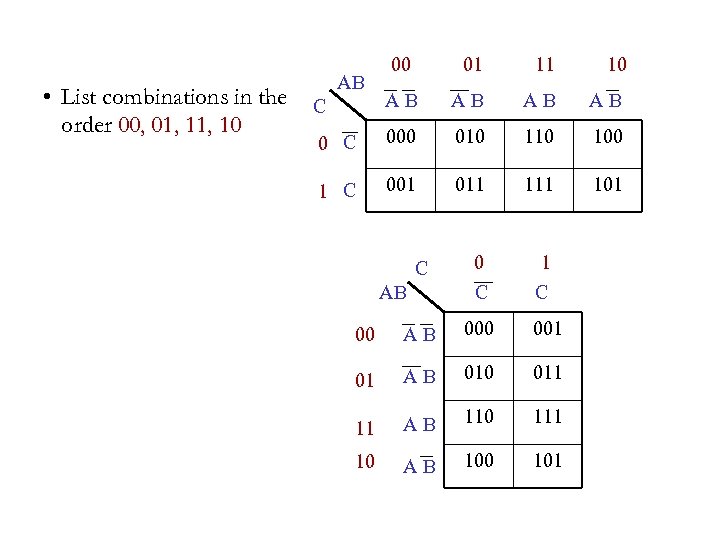

• List combinations in the order 00, 01, 10 00 01 11 10 C A B A B 0 C 000 010 100 1 C 001 011 101 0 1 C C AB 00 A B 000 001 01 A B 010 011 11 A B 110 111 10 A B 100 101

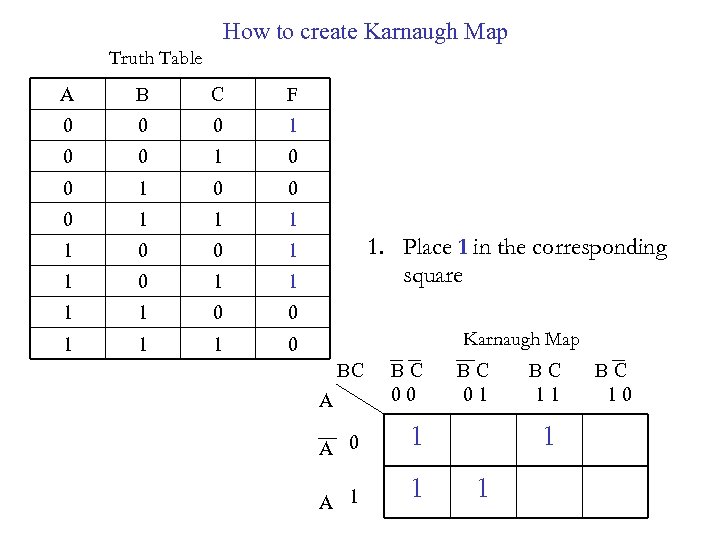

How to create Karnaugh Map Truth Table A B C F 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 0 1. Place 1 in the corresponding square Karnaugh Map BC A A 0 A 1 B C 0 0 B C 0 1 1 1 B C 1 0

Karnaugh Maps to Represent Boolean Functions AB 0 0 A B 0 1 A B 1 1 1 A B 1 0 A B 1 F = AB + AB

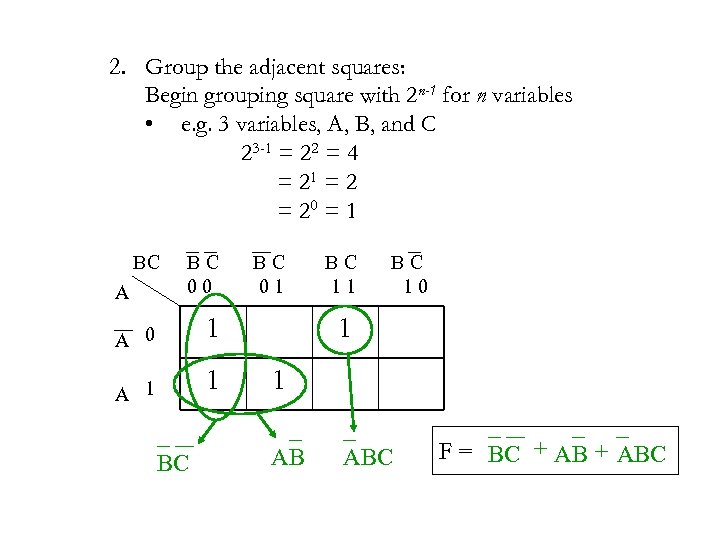

2. Group the adjacent squares: Begin grouping square with 2 n-1 for n variables • e. g. 3 variables, A, B, and C 23 -1 = 22 = 4 = 21 = 20 = 1 BC A B C 0 0 B C 0 1 1 A 0 1 A 1 BC B C 1 1 B C 1 0 1 1 AB ABC F = BC + ABC

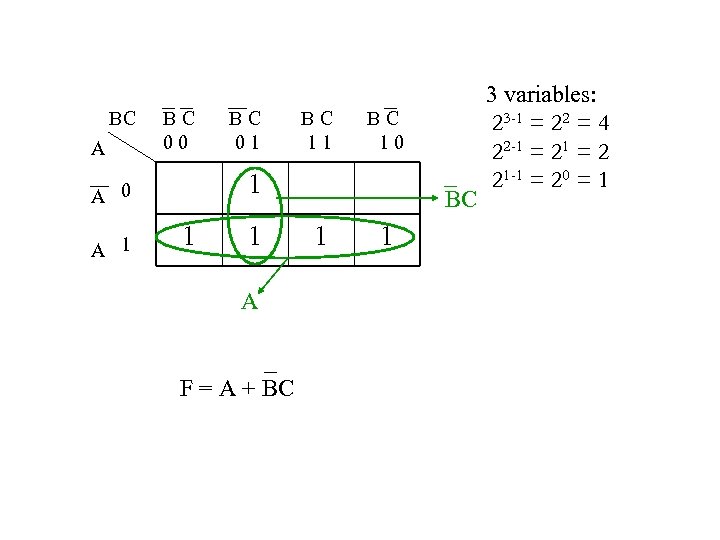

BC A B C 0 0 B C 1 1 B C 1 0 1 A 0 A 1 B C 0 1 1 1 A F = A + BC BC 1 1 3 variables: 23 -1 = 22 = 4 22 -1 = 2 21 -1 = 20 = 1

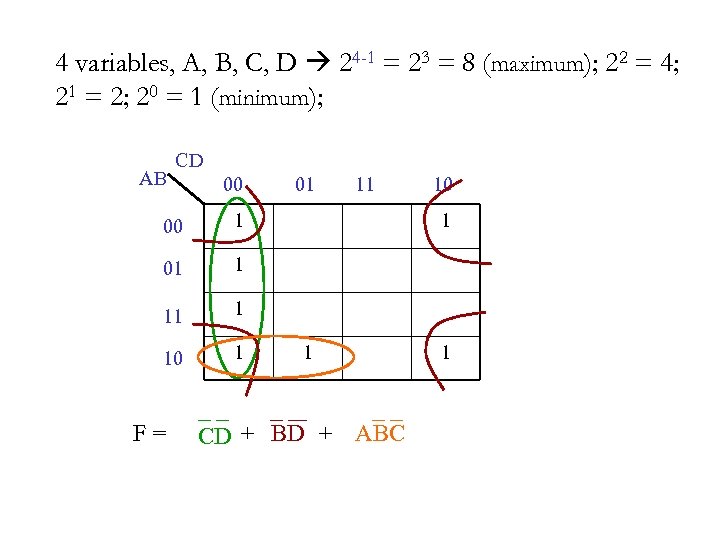

4 variables, A, B, C, D 24 -1 = 23 = 8 (maximum); 22 = 4; 21 = 2; 20 = 1 (minimum); AB CD 00 00 1 10 1 11 11 1 01 01 F = 1 1 CD + BD + ABC 1

Karnaugh Map Boolean Function Logic Circuit

Chapter 5 Summary

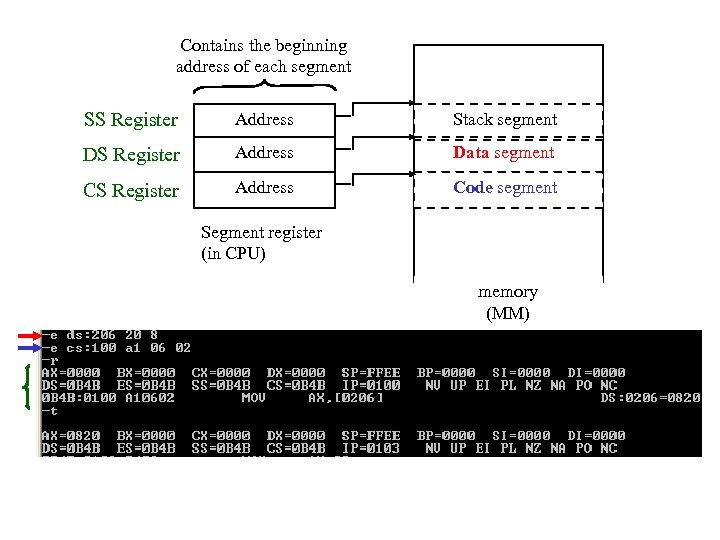

Contains the beginning address of each segment SS Register Address Stack segment DS Register Address Data segment CS Register Address Code segment Segment register (in CPU) memory (MM)

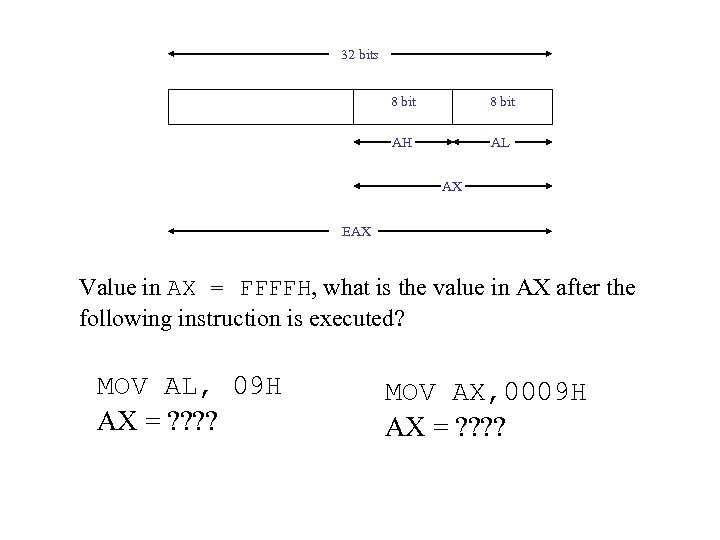

32 bits 8 bit AH AL AX EAX Value in AX = FFFFH, what is the value in AX after the following instruction is executed? MOV AL, 09 H AX = ? ? MOV AX, 0009 H AX = ? ?

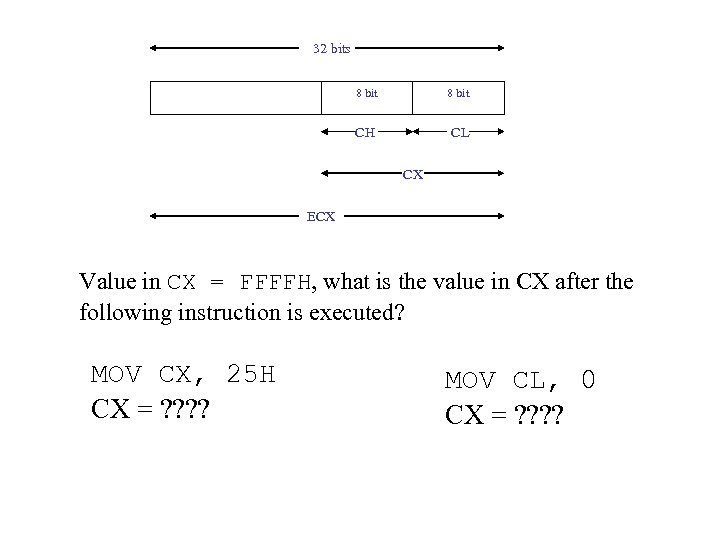

32 bits 8 bit CH CL CX ECX Value in CX = FFFFH, what is the value in CX after the following instruction is executed? MOV CX, 25 H CX = ? ? MOV CL, 0 CX = ? ?

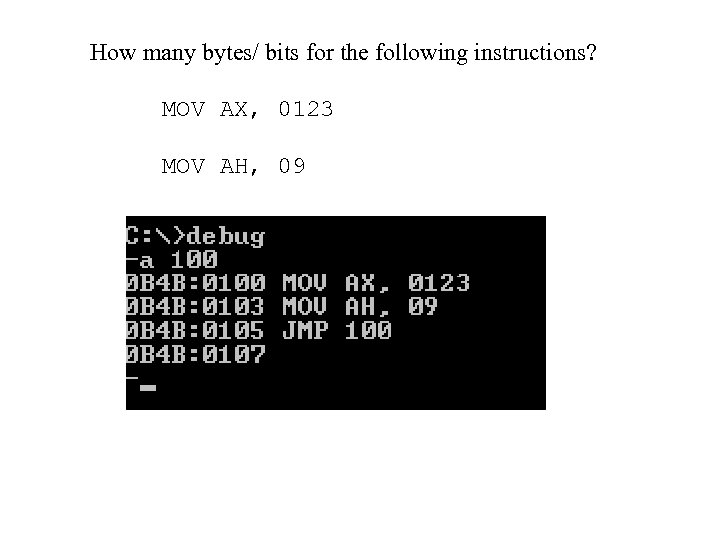

How many bytes/ bits for the following instructions? MOV AX, 0123 MOV AH, 09

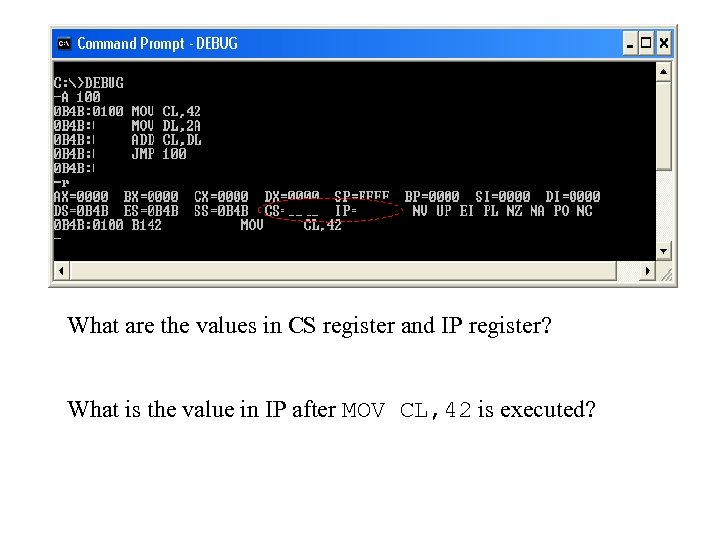

What are the values in CS register and IP register? What is the value in IP after MOV CL, 42 is executed?

CHAPTER 6 ASSEMBLY LANGUAGE PROGRAM FORMAT AND DATA DEFINITION 6. 1) Assembly Language Program Format 6. 2) Features of Assembly Language 6. 3) Data Definition

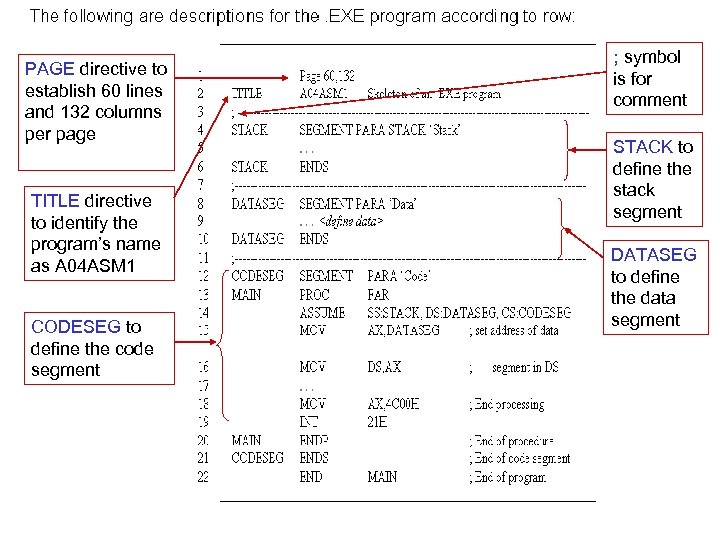

PAGE directive to establish 60 lines and 132 columns per page TITLE directive to identify the program’s name as A 04 ASM 1 CODESEG to define the code segment ; symbol is for comment STACK to define the stack segment DATASEG to define the data segment

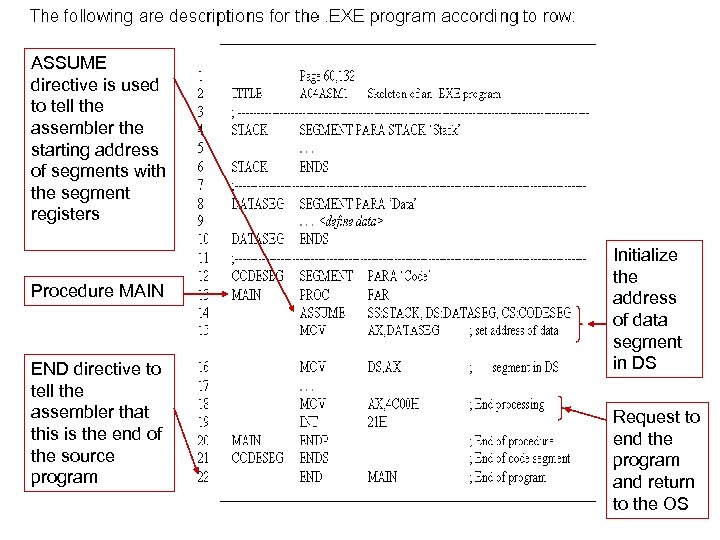

ASSUME directive is used to tell the assembler the starting address of segments with the segment registers Procedure MAIN END directive to tell the assembler that this is the end of the source program Initialize the address of data segment in DS Request to end the program and return to the OS

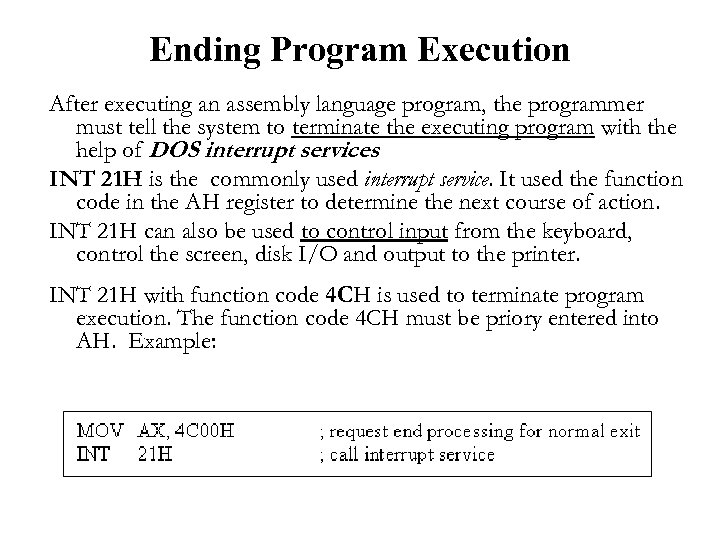

Ending Program Execution After executing an assembly language program, the programmer must tell the system to terminate the executing program with the help of DOS interrupt services. INT 21 H is the commonly used interrupt service. It used the function code in the AH register to determine the next course of action. INT 21 H can also be used to control input from the keyboard, control the screen, disk I/O and output to the printer. INT 21 H with function code 4 CH is used to terminate program execution. The function code 4 CH must be priory entered into AH. Example:

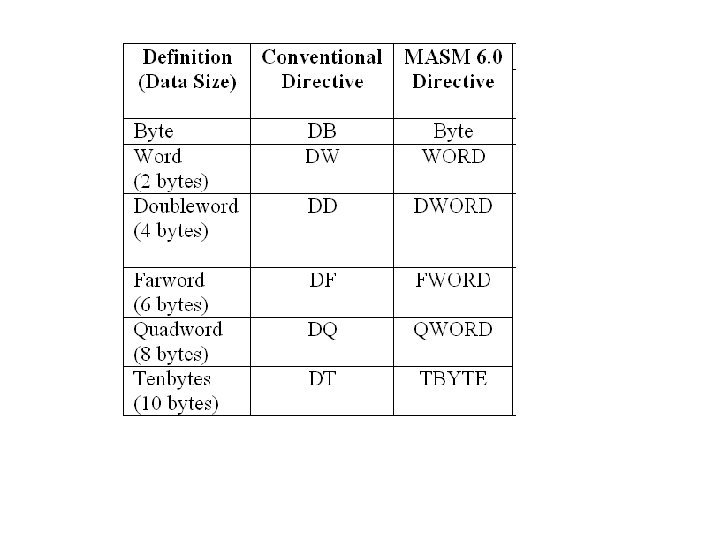

Data Definition Assembler offers a few directives that enable programmers to define data according to its type and length. Format for data definition: [name] Data names are optional because in assembly language programming, data is not necessarily reference by its name. Dn Directive Next slide are the common directives to define data and also directives used in MASM 6. 0

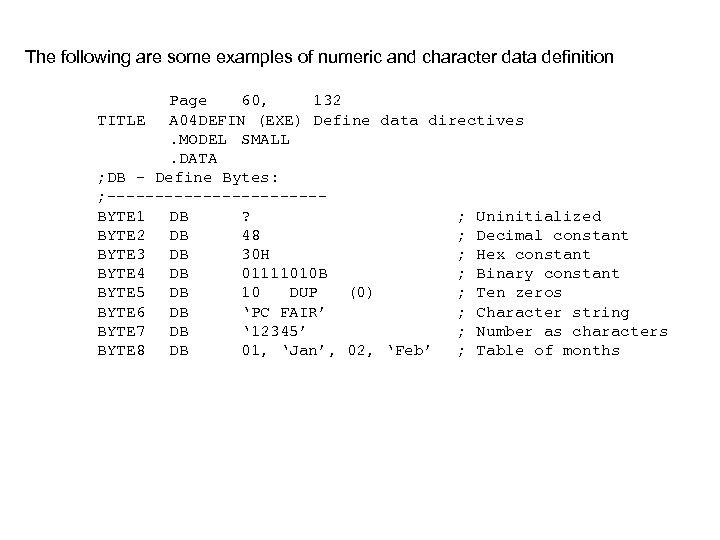

The following are some examples of numeric and character data definition Page 60, 132 TITLE A 04 DEFIN (EXE) Define data directives. MODEL SMALL. DATA ; DB – Define Bytes: ; -----------BYTE 1 DB ? ; Uninitialized BYTE 2 DB 48 ; Decimal constant BYTE 3 DB 30 H ; Hex constant BYTE 4 DB 01111010 B ; Binary constant BYTE 5 DB 10 DUP (0) ; Ten zeros BYTE 6 DB ‘PC FAIR’ ; Character string BYTE 7 DB ‘ 12345’ ; Number as characters BYTE 8 DB 01, ‘Jan’, 02, ‘Feb’ ; Table of months

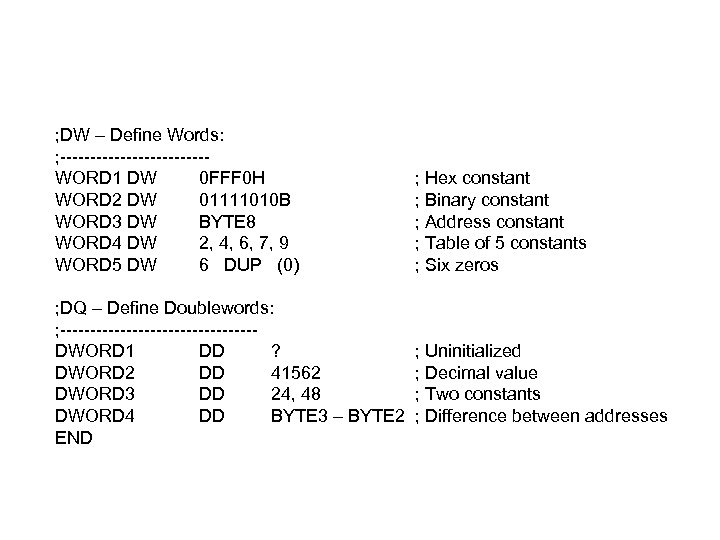

; DW – Define Words: ; ------------WORD 1 DW 0 FFF 0 H WORD 2 DW 01111010 B WORD 3 DW BYTE 8 WORD 4 DW 2, 4, 6, 7, 9 WORD 5 DW 6 DUP (0) ; DQ – Define Doublewords: ; ----------------DWORD 1 DD ? DWORD 2 DD 41562 DWORD 3 DD 24, 48 DWORD 4 DD BYTE 3 – BYTE 2 END ; Hex constant ; Binary constant ; Address constant ; Table of 5 constants ; Six zeros ; Uninitialized ; Decimal value ; Two constants ; Difference between addresses

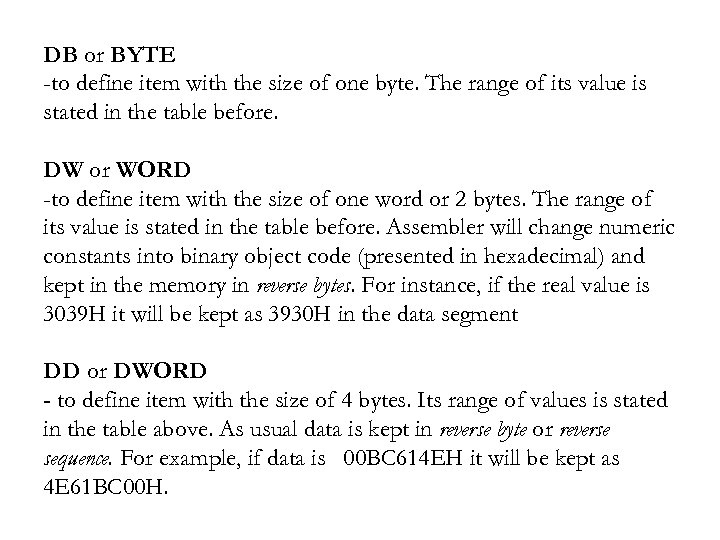

DB or BYTE -to define item with the size of one byte. The range of its value is stated in the table before. DW or WORD -to define item with the size of one word or 2 bytes. The range of its value is stated in the table before. Assembler will change numeric constants into binary object code (presented in hexadecimal) and kept in the memory in reverse bytes. For instance, if the real value is 3039 H it will be kept as 3930 H in the data segment DD or DWORD - to define item with the size of 4 bytes. Its range of values is stated in the table above. As usual data is kept in reverse byte or reverse sequence. For example, if data is 00 BC 614 EH it will be kept as 4 E 61 BC 00 H.

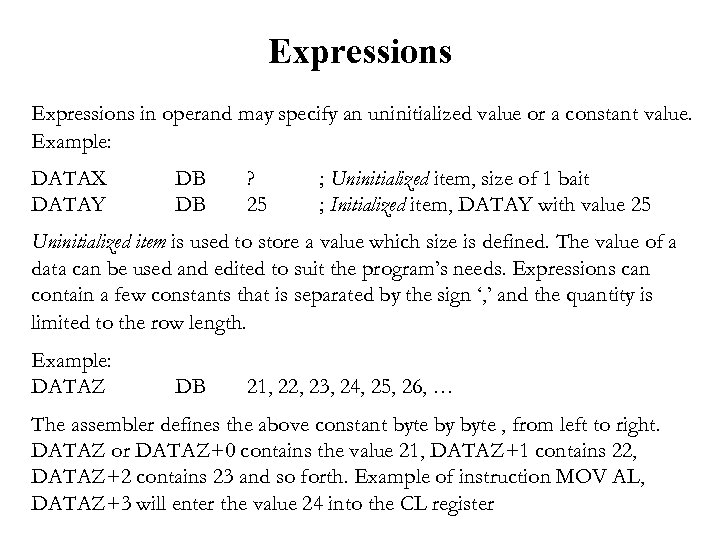

Expressions in operand may specify an uninitialized value or a constant value. Example: DATAX DATAY DB DB ? 25 ; Uninitialized item, size of 1 bait ; Initialized item, DATAY with value 25 Uninitialized item is used to store a value which size is defined. The value of a data can be used and edited to suit the program’s needs. Expressions can contain a few constants that is separated by the sign ‘, ’ and the quantity is limited to the row length. Example: DATAZ DB 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, … The assembler defines the above constant byte by byte , from left to right. DATAZ or DATAZ+0 contains the value 21, DATAZ+1 contains 22, DATAZ+2 contains 23 and so forth. Example of instruction MOV AL, DATAZ+3 will enter the value 24 into the CL register

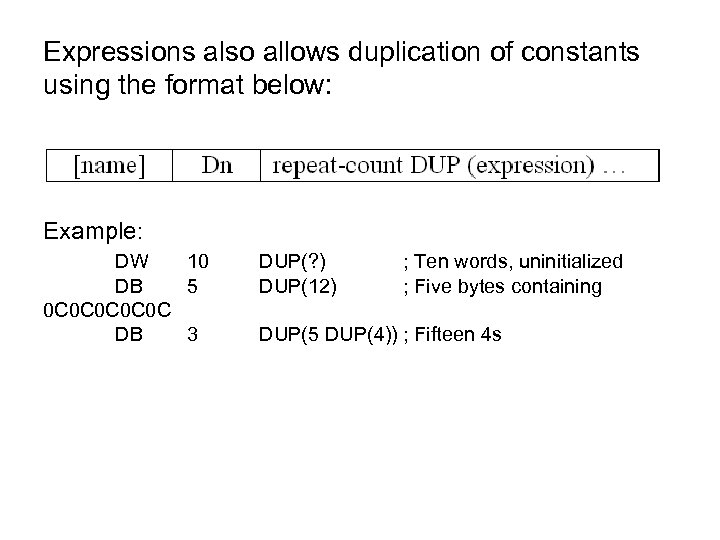

Expressions also allows duplication of constants using the format below: Example: DW 10 DB 5 0 C 0 C 0 C DB 3 DUP(? ) DUP(12) ; Ten words, uninitialized ; Five bytes containing DUP(5 DUP(4)) ; Fifteen 4 s

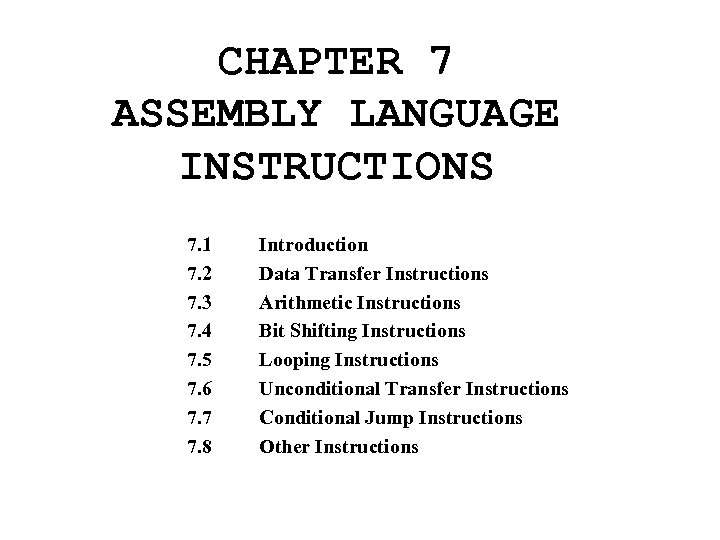

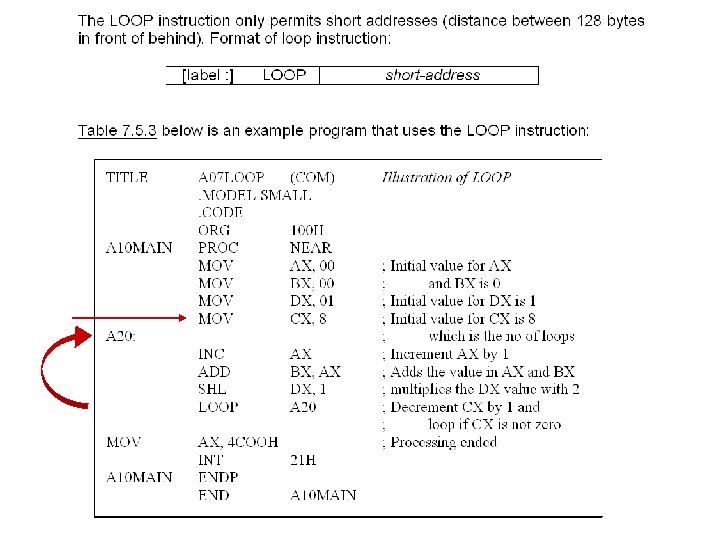

CHAPTER 7 ASSEMBLY LANGUAGE INSTRUCTIONS 7. 1 7. 2 7. 3 7. 4 7. 5 7. 6 7. 7 7. 8 Introduction Data Transfer Instructions Arithmetic Instructions Bit Shifting Instructions Looping Instructions Unconditional Transfer Instructions Conditional Jump Instructions Other Instructions

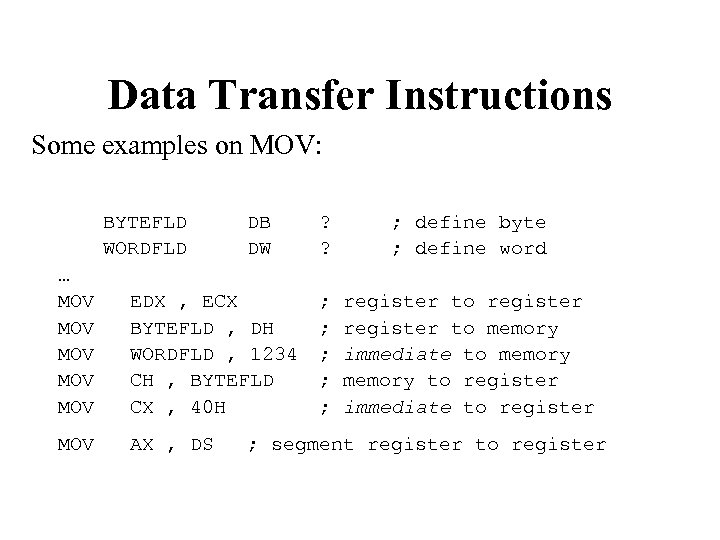

Data Transfer Instructions Some examples on MOV: BYTEFLD WORDFLD DB DW … MOV EDX , ECX MOV BYTEFLD , DH MOV WORDFLD , 1234 MOV CH , BYTEFLD MOV CX , 40 H MOV AX , DS ? ? ; define byte ; define word ; register to register ; register to memory ; immediate to memory ; memory to register ; immediate to register ; segment register to register

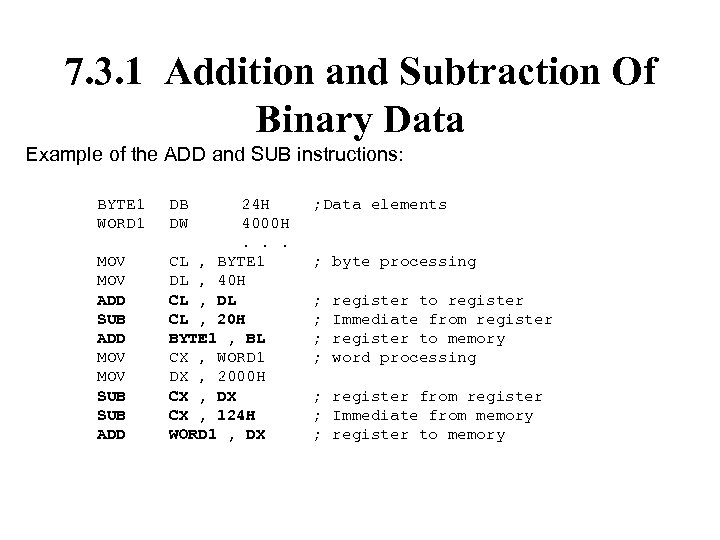

7. 3. 1 Addition and Subtraction Of Binary Data Example of the ADD and SUB instructions: BYTE 1 WORD 1 MOV ADD SUB ADD MOV SUB ADD DB DW 24 H 4000 H. . . CL , BYTE 1 DL , 40 H CL , DL CL , 20 H BYTE 1 , BL CX , WORD 1 DX , 2000 H CX , DX CX , 124 H WORD 1 , DX ; Data elements ; byte processing ; register to register ; Immediate from register ; register to memory ; word processing ; register from register ; Immediate from memory ; register to memory

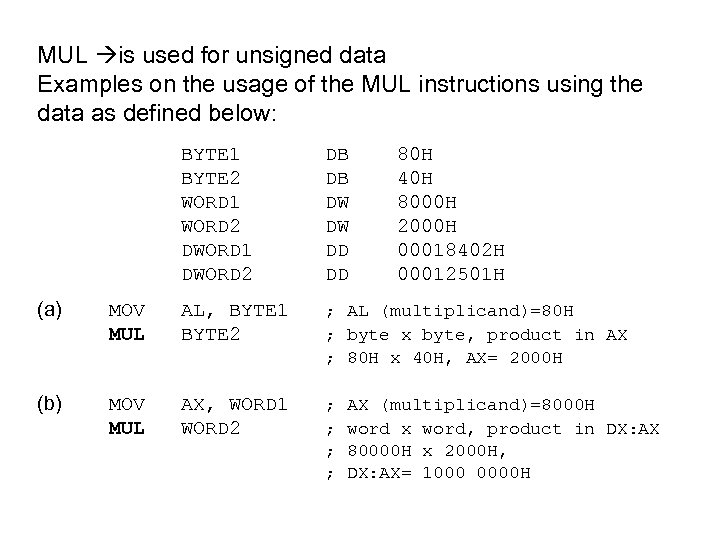

MUL is used for unsigned data Examples on the usage of the MUL instructions using the data as defined below: BYTE 1 BYTE 2 WORD 1 WORD 2 DWORD 1 DWORD 2 DB DB DW DW DD DD 80 H 40 H 8000 H 2000 H 00018402 H 00012501 H (a) MOV MUL AL, BYTE 1 BYTE 2 ; AL (multiplicand)=80 H ; byte x byte, product in AX ; 80 H x 40 H, AX= 2000 H (b) MOV MUL AX, WORD 1 WORD 2 ; AX (multiplicand)=8000 H ; word x word, product in DX: AX ; 80000 H x 2000 H, ; DX: AX= 1000 0000 H

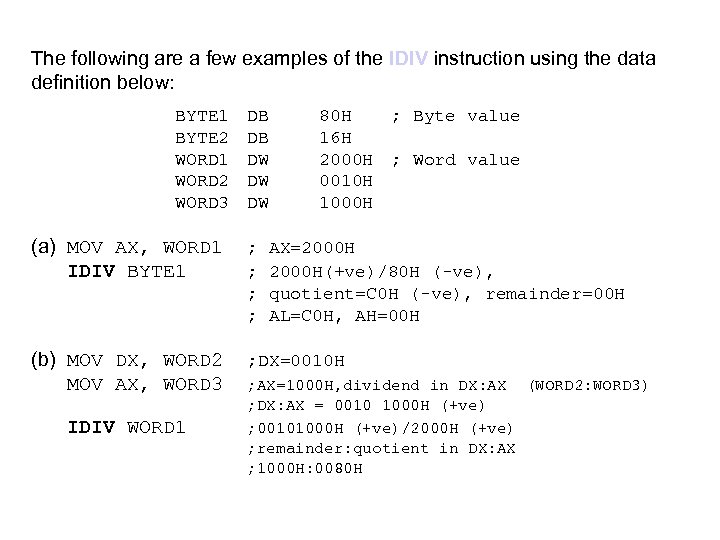

The following are a few examples of the IDIV instruction using the data definition below: BYTE 1 BYTE 2 WORD 1 WORD 2 WORD 3 DB DB DW DW DW 80 H ; Byte value 16 H 2000 H ; Word value 0010 H 1000 H (a) MOV AX, WORD 1 IDIV BYTE 1 ; AX=2000 H ; 2000 H(+ve)/80 H (-ve), ; quotient=C 0 H (-ve), remainder=00 H ; AL=C 0 H, AH=00 H (b) MOV DX, WORD 2 MOV AX, WORD 3 ; DX=0010 H IDIV WORD 1 ; AX=1000 H, dividend in DX: AX (WORD 2: WORD 3) ; DX: AX = 0010 1000 H (+ve) ; 00101000 H (+ve)/2000 H (+ve) ; remainder: quotient in DX: AX ; 1000 H: 0080 H

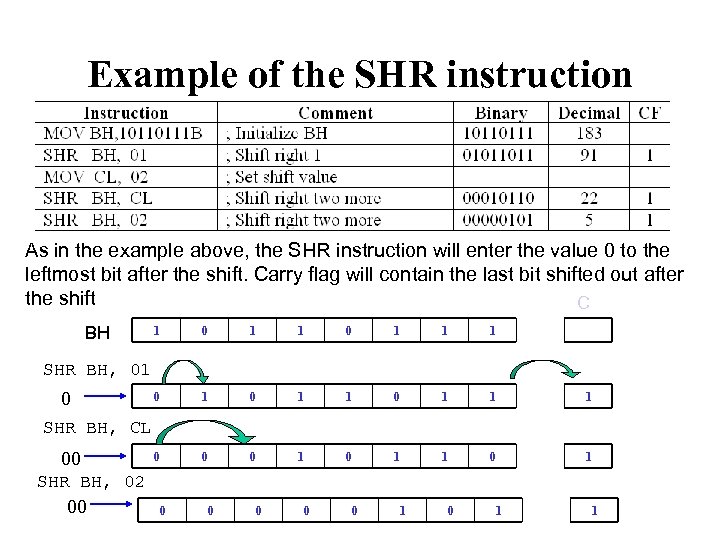

Example of the SHR instruction As in the example above, the SHR instruction will enter the value 0 to the leftmost bit after the shift. Carry flag will contain the last bit shifted out after the shift C BH 1 0 1 1 1 0 0 0 1 1 0 1 SHR BH, 01 0 SHR BH, CL 00 SHR BH, 02 00 0 0 1 0 1 1

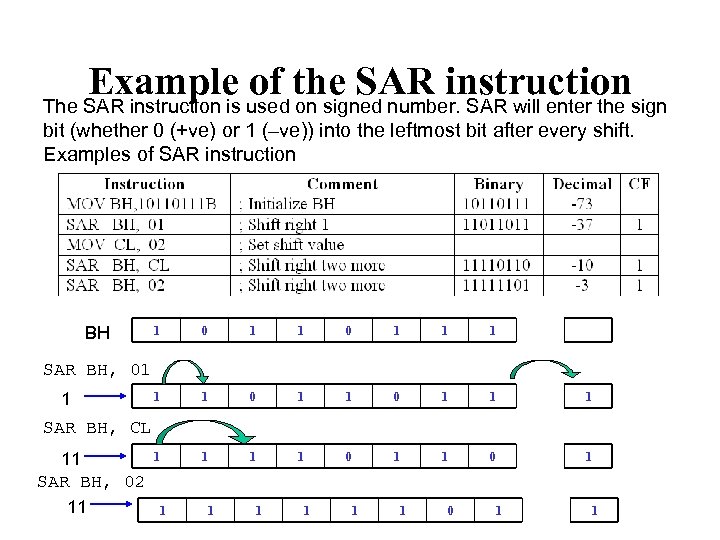

Example of the SAR instruction The SAR instruction is used on signed number. SAR will enter the sign bit (whether 0 (+ve) or 1 (–ve)) into the leftmost bit after every shift. Examples of SAR instruction BH 1 0 1 1 1 1 0 1 SAR BH, 01 1 SAR BH, CL 11 SAR BH, 02 11 1 1 1 0 1 1

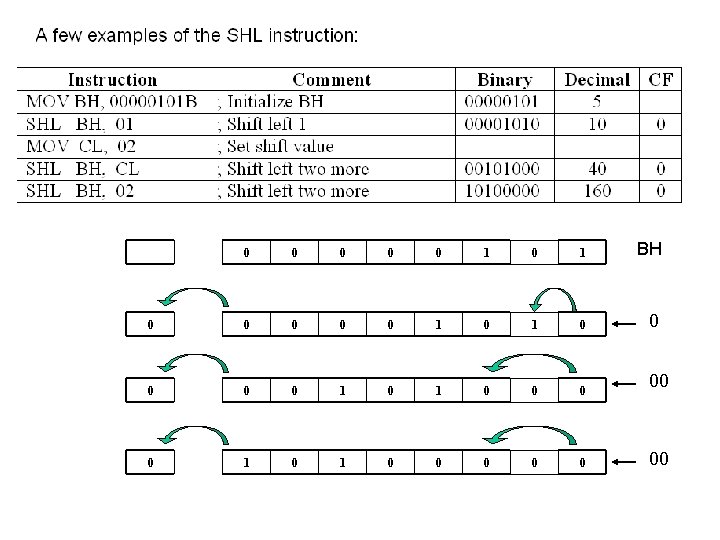

0 0 0 1 BH 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 00 00

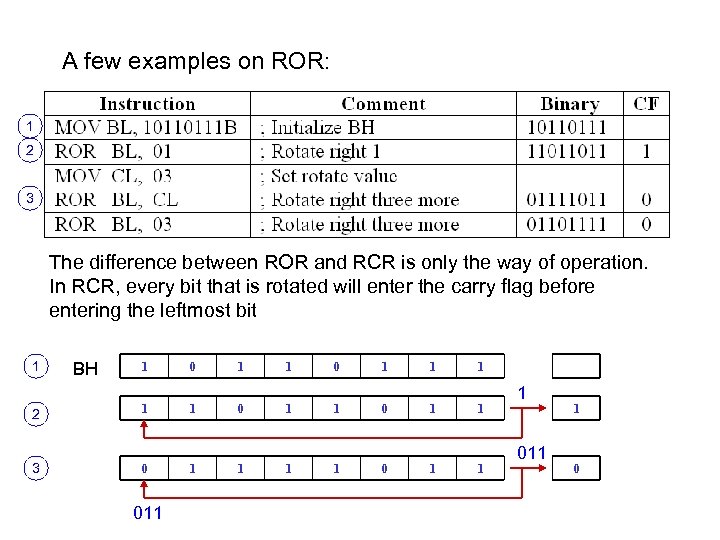

A few examples on ROR: 1 2 3 The difference between ROR and RCR is only the way of operation. In RCR, every bit that is rotated will enter the carry flag before entering the leftmost bit 1 2 3 BH 1 1 0 011 0 1 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 011 1 0

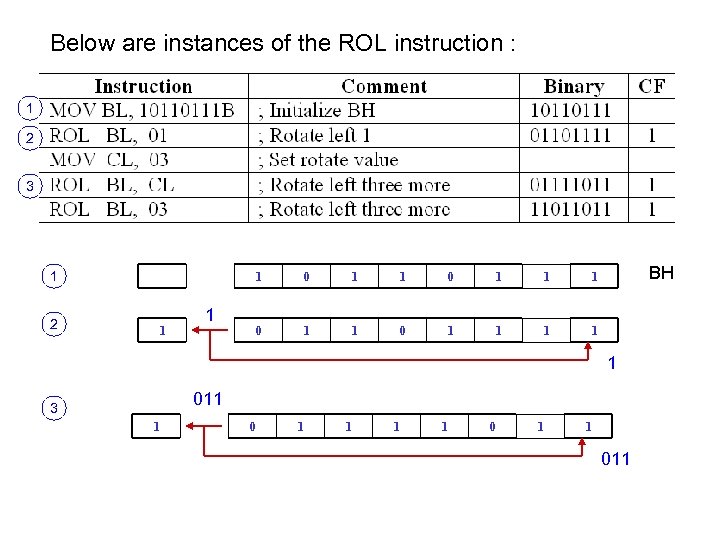

Below are instances of the ROL instruction : 1 2 3 1 2 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 BH 1 1 1 011 3 1 0 1 1 011

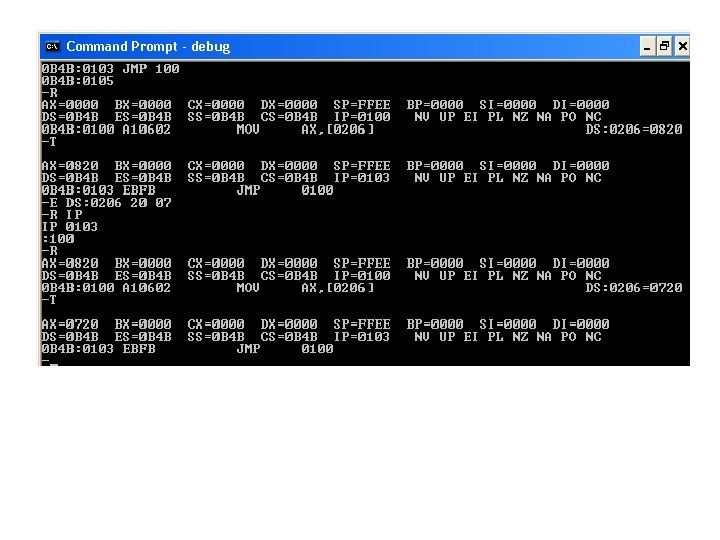

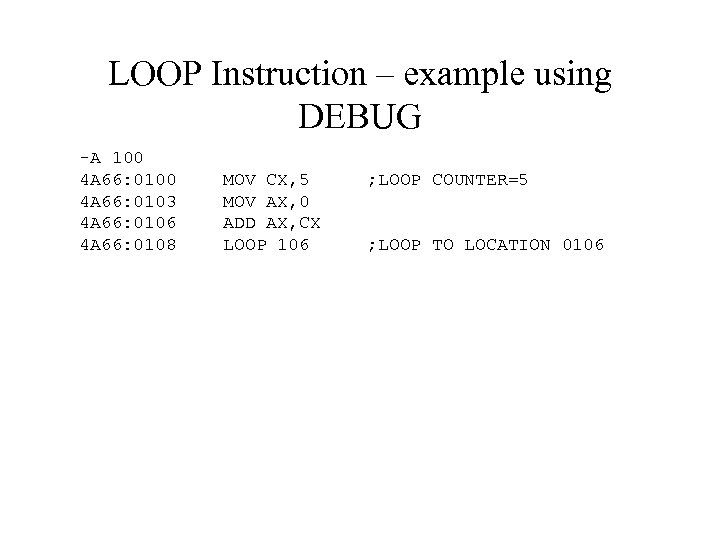

LOOP Instruction – example using DEBUG -A 100 4 A 66: 0103 4 A 66: 0106 4 A 66: 0108 MOV CX, 5 MOV AX, 0 ADD AX, CX LOOP 106 ; LOOP COUNTER=5 ; LOOP TO LOCATION 0106

a4e82aa6d05ecfe5f1413fabb3edaac6.ppt