e4a65f0586d1f5bec0df9631cb892003.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 28

Chapter 18 Development, Planning & Policy Making: The State and the Market CHAPTER 18 ©E. Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 1

Chapter 18 Development, Planning & Policy Making: The State and the Market CHAPTER 18 ©E. Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 1

Development Planning & Policy Making: The State & the Market n n n n n Development Planning Dirigiste Debate Soviet Planning Indian Planning The Market versus Detailed Centralized Planning Indicative Planning Limitations of Planning Models The Input-Output Table Public Policies and Expenditures CHAPTER 18 ©E. Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 2

Development Planning & Policy Making: The State & the Market n n n n n Development Planning Dirigiste Debate Soviet Planning Indian Planning The Market versus Detailed Centralized Planning Indicative Planning Limitations of Planning Models The Input-Output Table Public Policies and Expenditures CHAPTER 18 ©E. Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 2

Development planning n n The government’s use of coordinated policies to achieve national economic objectives such as reduced poverty or accelerated economic growth. Economists have recently emphasized that the planning commission should be directly responsible to politicians and integrated with government departments of industry, finance, commerce, petroleum, agriculture, health, education, and social welfare, as well as with regional and local government departments and planners. CHAPTER 18 ©E. Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 3

Development planning n n The government’s use of coordinated policies to achieve national economic objectives such as reduced poverty or accelerated economic growth. Economists have recently emphasized that the planning commission should be directly responsible to politicians and integrated with government departments of industry, finance, commerce, petroleum, agriculture, health, education, and social welfare, as well as with regional and local government departments and planners. CHAPTER 18 ©E. Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 3

Dirigiste debate n n n Criticism of LDC state planning and public enterprise partly because of frequent soft budget constraint, an absence of financial penalty for enterprise failure. Lal (1983) criticizes development economists’ dirigiste dogma, a view that standard economic theory does not apply to LDCs. Lal’s description of their views is a caricature. CHAPTER 18 ©E. Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 4

Dirigiste debate n n n Criticism of LDC state planning and public enterprise partly because of frequent soft budget constraint, an absence of financial penalty for enterprise failure. Lal (1983) criticizes development economists’ dirigiste dogma, a view that standard economic theory does not apply to LDCs. Lal’s description of their views is a caricature. CHAPTER 18 ©E. Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 4

Soviet planning n n n Controlling plan that authorized what each key sector enterprise produced and how much it invested. Yet these enterprises still faced much local, extraplan discretion: government could not control all operations details, even with computers. Trotsky (1931), an opponent of Stalin, contended that “Economic accounting is unthinkable without market relations. ” CHAPTER 18 ©E. Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 5

Soviet planning n n n Controlling plan that authorized what each key sector enterprise produced and how much it invested. Yet these enterprises still faced much local, extraplan discretion: government could not control all operations details, even with computers. Trotsky (1931), an opponent of Stalin, contended that “Economic accounting is unthinkable without market relations. ” CHAPTER 18 ©E. Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 5

Indian planning n n n In 1950, India was the first major mixed LDC to have its own planning commission. From 1951 through 1978, India’s plans suffered from the paradox of inadequate attention to public sector programs and too much control over the private sector. The choice of public sector investments were frequently based on incomplete reports, with few cost-benefit calculations, and a lack of necessary detailed technical preparations. CHAPTER 18 ©E. Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 6

Indian planning n n n In 1950, India was the first major mixed LDC to have its own planning commission. From 1951 through 1978, India’s plans suffered from the paradox of inadequate attention to public sector programs and too much control over the private sector. The choice of public sector investments were frequently based on incomplete reports, with few cost-benefit calculations, and a lack of necessary detailed technical preparations. CHAPTER 18 ©E. Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 6

Indian planners influenced private investment & productions through licensing and other controls n Before the 1991 reforms, the Indian government awarded materials and input quotas at below-market prices, which hampered private industrial efficiency. CHAPTER 18 ©E. Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 7

Indian planners influenced private investment & productions through licensing and other controls n Before the 1991 reforms, the Indian government awarded materials and input quotas at below-market prices, which hampered private industrial efficiency. CHAPTER 18 ©E. Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 7

How India’s policies distorted firm and entrepreneurial behavior n n n They subsidized some firms and forced others to buy inputs on the black market or do without. Favoring existing firms discouraged new-firm entry. And inefficient manufacturers sold controlled inputs on the free market for sizable profit. Businesspeople were unproductive, because they were dealing with government agencies and buying and selling controlled materials. Capital was often underutilized, because government encouraged building excess capacity by awarding more materials to firms with greater plant capacity. Entrepreneurs inflated materials requests, expecting allotments to be reduced by a specific percentage. CHAPTER 18 ©E. Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 8

How India’s policies distorted firm and entrepreneurial behavior n n n They subsidized some firms and forced others to buy inputs on the black market or do without. Favoring existing firms discouraged new-firm entry. And inefficient manufacturers sold controlled inputs on the free market for sizable profit. Businesspeople were unproductive, because they were dealing with government agencies and buying and selling controlled materials. Capital was often underutilized, because government encouraged building excess capacity by awarding more materials to firms with greater plant capacity. Entrepreneurs inflated materials requests, expecting allotments to be reduced by a specific percentage. CHAPTER 18 ©E. Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 8

How India’s policies distorted firm and entrepreneurial behavior (cont) n n Businesspeople used or sold all materials within the fiscal year to avoid quota cuts the following years. A shortage of controlled inputs could halt production, because the application process took several months. Large companies, which were better organized and informed than small enterprises, took advantage of economies of scale in dealing with the public bureaucracy. Entrepreneurial planning was difficult because of quota delay and uncertainty (Bhagwati and Desai 1970; Nafziger 1978: 114– 119). CHAPTER 18 ©E. Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 9

How India’s policies distorted firm and entrepreneurial behavior (cont) n n Businesspeople used or sold all materials within the fiscal year to avoid quota cuts the following years. A shortage of controlled inputs could halt production, because the application process took several months. Large companies, which were better organized and informed than small enterprises, took advantage of economies of scale in dealing with the public bureaucracy. Entrepreneurial planning was difficult because of quota delay and uncertainty (Bhagwati and Desai 1970; Nafziger 1978: 114– 119). CHAPTER 18 ©E. Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 9

India’s 1991 economic reform n n Budget, debt, and balance-of-payments crises woke the Indian government to the stifling nature of licensing and the need for liberalization reforms. Growth rates accelerated after 1991, with rupee devaluation, increasing convertibility, import barrier reductions, widespread privatization, industry deregulation, decreased restrictions on foreign investment, liberalization of capital markets, and cutbacks in income and wealth taxes. CHAPTER 18 ©E. Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 10

India’s 1991 economic reform n n Budget, debt, and balance-of-payments crises woke the Indian government to the stifling nature of licensing and the need for liberalization reforms. Growth rates accelerated after 1991, with rupee devaluation, increasing convertibility, import barrier reductions, widespread privatization, industry deregulation, decreased restrictions on foreign investment, liberalization of capital markets, and cutbacks in income and wealth taxes. CHAPTER 18 ©E. Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 10

The market versus detailed centralized planning Pro-market arguments: 1. The market efficiently allocates scarce resources among alternative ends. a. Consumers receive goods for which they are willing to pay. b. Firms produce commodities to maximize profits, so that consumption and production are socially efficient if the resulting income distribution is acceptable. c. Production resources hire out to maximize income. d. The market determines available labor and capital. e. The market distributes income among production resources and, thus, among individuals. CHAPTER 18 ©E. Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 11

The market versus detailed centralized planning Pro-market arguments: 1. The market efficiently allocates scarce resources among alternative ends. a. Consumers receive goods for which they are willing to pay. b. Firms produce commodities to maximize profits, so that consumption and production are socially efficient if the resulting income distribution is acceptable. c. Production resources hire out to maximize income. d. The market determines available labor and capital. e. The market distributes income among production resources and, thus, among individuals. CHAPTER 18 ©E. Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 11

Pro-market arguments (cont) 2. The market provides incentives for innovation and economic growth. 3. The market stimulates growth and efficiency automatically, without a large administration on centralized decision making. CHAPTER 18 ©E. Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 12

Pro-market arguments (cont) 2. The market provides incentives for innovation and economic growth. 3. The market stimulates growth and efficiency automatically, without a large administration on centralized decision making. CHAPTER 18 ©E. Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 12

Pro-planning arguments: 1. Market decisions do not produce the best results when the market fails, as with environmental degradation, HIV/AIDS prevention, measles vaccinations, and labor training. Social profitability exceeds private profitability when external economies are rendered free by one economic unit to consumers or producers. CHAPTER 18 ©E. Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 13

Pro-planning arguments: 1. Market decisions do not produce the best results when the market fails, as with environmental degradation, HIV/AIDS prevention, measles vaccinations, and labor training. Social profitability exceeds private profitability when external economies are rendered free by one economic unit to consumers or producers. CHAPTER 18 ©E. Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 13

Pro-planning arguments: 2. Social and private profitability diverge in a market economy when there are monopolistic restraints and other market failures. 3. Government needs to produce the public or collective goods, schools, defense, sewage disposal, and police and fire protection that the market fails to produce. 4. The free market may not produce so high a saving rate as is socially desirable. 5. The planning agency can disseminate information to make the market work more effectively. CHAPTER 18 ©E. Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 14

Pro-planning arguments: 2. Social and private profitability diverge in a market economy when there are monopolistic restraints and other market failures. 3. Government needs to produce the public or collective goods, schools, defense, sewage disposal, and police and fire protection that the market fails to produce. 4. The free market may not produce so high a saving rate as is socially desirable. 5. The planning agency can disseminate information to make the market work more effectively. CHAPTER 18 ©E. Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 14

Indicative plans n n Most mixed or capitalist developing countries are limited to an indicative plan, which indicates expectations, aspirations, and intentions, but falls short of authorization. Indicative planning may include economic forecasts, helping private decision makers, policies favorable to the private sector, ways of raising money and recruiting personnel, and a list of proposed public expenditures – usually not authorized by the plan, but the annual budget. CHAPTER 18 ©E. Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 15

Indicative plans n n Most mixed or capitalist developing countries are limited to an indicative plan, which indicates expectations, aspirations, and intentions, but falls short of authorization. Indicative planning may include economic forecasts, helping private decision makers, policies favorable to the private sector, ways of raising money and recruiting personnel, and a list of proposed public expenditures – usually not authorized by the plan, but the annual budget. CHAPTER 18 ©E. Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 15

Limitations of planning models 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. LDCs may not be able to afford the complexity of many macroeconomic models. Policy control in mixed and capitalist LDCs is too limited for a comprehensive aggregate model to have much practical value. Consistency and ability to dazzle do not mean that the plan is right. Of little value if planners have not consulted with economic departments and private firms. Models are of less importance than adequate preparatory work for projects & professionals: one with treasury experience, a practical economist familiar with an LDC’s unique problems, & an econometrician who can construct input-output tables. CHAPTER 18 ©E. Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 16

Limitations of planning models 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. LDCs may not be able to afford the complexity of many macroeconomic models. Policy control in mixed and capitalist LDCs is too limited for a comprehensive aggregate model to have much practical value. Consistency and ability to dazzle do not mean that the plan is right. Of little value if planners have not consulted with economic departments and private firms. Models are of less importance than adequate preparatory work for projects & professionals: one with treasury experience, a practical economist familiar with an LDC’s unique problems, & an econometrician who can construct input-output tables. CHAPTER 18 ©E. Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 16

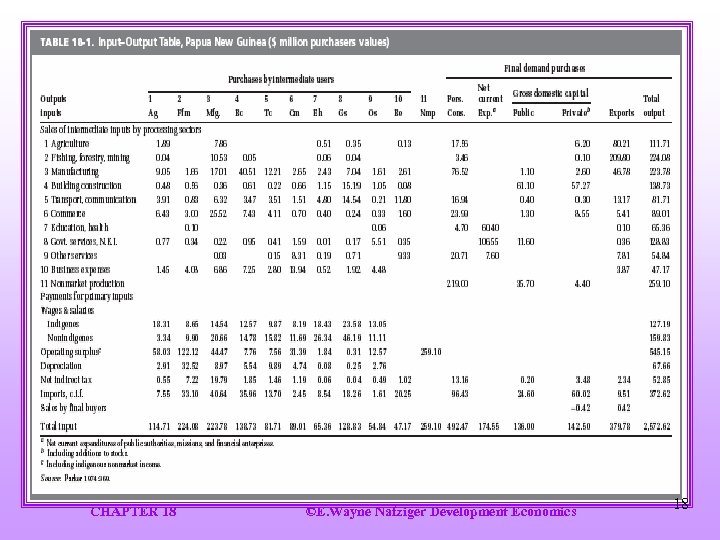

The input-output table n n n Illustrated by Table 18 -1, showing interindustry transactions in Papua New Guinea in 1974. When divided horizontally, the table shows how the output of each industry is distributed among other industries and sectors of the economy. When divided vertically, the table shows the inputs to each industry from other industries and sectors. CHAPTER 18 ©E. Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 17

The input-output table n n n Illustrated by Table 18 -1, showing interindustry transactions in Papua New Guinea in 1974. When divided horizontally, the table shows how the output of each industry is distributed among other industries and sectors of the economy. When divided vertically, the table shows the inputs to each industry from other industries and sectors. CHAPTER 18 ©E. Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 17

CHAPTER 18 ©E. Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 18

CHAPTER 18 ©E. Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 18

How to read the input-output table n n 1. To find the amount of purchases from one sector by another, locate the purchasing industry (e. g. , 7 Eh) at the top of the table, then read down the column until you come to the processing industry ($4. 80 million from 5 Transport, communication). 2. To find the amount of sales from one sector to another, locate the selling industry (e. g. , 4 Building construction) along the left side of the table, then read across the row until you come to the buying industry (Building construction sells $0. 36 to 3 Mfg). CHAPTER 18 ©E. Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 19

How to read the input-output table n n 1. To find the amount of purchases from one sector by another, locate the purchasing industry (e. g. , 7 Eh) at the top of the table, then read down the column until you come to the processing industry ($4. 80 million from 5 Transport, communication). 2. To find the amount of sales from one sector to another, locate the selling industry (e. g. , 4 Building construction) along the left side of the table, then read across the row until you come to the buying industry (Building construction sells $0. 36 to 3 Mfg). CHAPTER 18 ©E. Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 19

Totals n n Intermediate inputs from the upper left plus primary inputs from the lower left equal total inputs, for example, $114. 71 million, the total output for agriculture (a typo). The sum of the outputs from all individual rows, $2, 752. 62, is far in excess of GNP for the same year, $952. 68 million. Because the input-output table measures all transactions between sectors of the economy, the value of goods and services produced in a given year (that is, an accumulation of value added at each stage of the production process through final demand) is counted more than once. CHAPTER 18 ©E. Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 20

Totals n n Intermediate inputs from the upper left plus primary inputs from the lower left equal total inputs, for example, $114. 71 million, the total output for agriculture (a typo). The sum of the outputs from all individual rows, $2, 752. 62, is far in excess of GNP for the same year, $952. 68 million. Because the input-output table measures all transactions between sectors of the economy, the value of goods and services produced in a given year (that is, an accumulation of value added at each stage of the production process through final demand) is counted more than once. CHAPTER 18 ©E. Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 20

The input-output table’s uses n n n Sectoral information from data gathered. If the plan sets final demand the sectors to produce it, detailed interrelationships & deliveries can be approximated by tracking through the table the direct and indirect purchases needed. Implications of alternative development strategies for economic structure, import requirements, balance of payments, employment, investment demand, and national income through using high-speed electronic calculations. CHAPTER 18 ©E. Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 21

The input-output table’s uses n n n Sectoral information from data gathered. If the plan sets final demand the sectors to produce it, detailed interrelationships & deliveries can be approximated by tracking through the table the direct and indirect purchases needed. Implications of alternative development strategies for economic structure, import requirements, balance of payments, employment, investment demand, and national income through using high-speed electronic calculations. CHAPTER 18 ©E. Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 21

Problems of the input-output table 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Technical coefficients fixed, so no substitution between inputs. Input functions are linear, so that output increases by the same multiple as inputs. The marginal input coefficient is equal to the average, implying no economies of scale. There are no externalities, so that the total effect of carrying out several activities is the sum of the separate effects. There are no joint products. Each good is produced by only one industry, and each industry produces only one commodity. There is no technical change, ruling out reduced inputs required per output unit. CHAPTER 18 ©E. Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 22

Problems of the input-output table 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Technical coefficients fixed, so no substitution between inputs. Input functions are linear, so that output increases by the same multiple as inputs. The marginal input coefficient is equal to the average, implying no economies of scale. There are no externalities, so that the total effect of carrying out several activities is the sum of the separate effects. There are no joint products. Each good is produced by only one industry, and each industry produces only one commodity. There is no technical change, ruling out reduced inputs required per output unit. CHAPTER 18 ©E. Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 22

Assessments of input-output tables: additional comments n n Errors may not be substantial during a period of 5 years of less (when relative factor prices and level of technology may be relatively constant). Unfortunately, input-output tables in both DCs and LDCs are not timely, sometimes more than 10 years out of date. CHAPTER 18 ©E. Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 23

Assessments of input-output tables: additional comments n n Errors may not be substantial during a period of 5 years of less (when relative factor prices and level of technology may be relatively constant). Unfortunately, input-output tables in both DCs and LDCs are not timely, sometimes more than 10 years out of date. CHAPTER 18 ©E. Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 23

Public policies & expenditures: policies toward the private sector n n The private sector is larger than the public sector, and is usually outside the purview of planners. Private sector planning means government trying to get people to do what the would otherwise not do – invest more in equipment or improve their job skills, change jobs, switch from one crop to another, adopt new technologies, and so on. CHAPTER 18 ©E. Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 24

Public policies & expenditures: policies toward the private sector n n The private sector is larger than the public sector, and is usually outside the purview of planners. Private sector planning means government trying to get people to do what the would otherwise not do – invest more in equipment or improve their job skills, change jobs, switch from one crop to another, adopt new technologies, and so on. CHAPTER 18 ©E. Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 24

Public policies toward the private sector 1. Investigating development potential through scientific and market research, and natural resources surveys. 2. Providing adequate infrastructure (water, power, transport, and communication) for public and private agencies. 3. Providing the necessary skills through general education and specialized training. 4. Improving the legal framework related to land tenure, corporations, commercial transactions, and other economic activities. CHAPTER 18 ©E. Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 25

Public policies toward the private sector 1. Investigating development potential through scientific and market research, and natural resources surveys. 2. Providing adequate infrastructure (water, power, transport, and communication) for public and private agencies. 3. Providing the necessary skills through general education and specialized training. 4. Improving the legal framework related to land tenure, corporations, commercial transactions, and other economic activities. CHAPTER 18 ©E. Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 25

Public policies toward the private sector (cont) 5. Creating markets, including commodity markets, security exchanges, banks, credit facilities, and insurance companies. 6. Seeking out and assisting entrepreneurs. 7. Promoting better resource utilization through inducements and controls. 8. Promoting private and public saving. 9. Reducing monopolies and oligopolies (Lewis 1966: 13– 24). CHAPTER 18 ©E. Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 26

Public policies toward the private sector (cont) 5. Creating markets, including commodity markets, security exchanges, banks, credit facilities, and insurance companies. 6. Seeking out and assisting entrepreneurs. 7. Promoting better resource utilization through inducements and controls. 8. Promoting private and public saving. 9. Reducing monopolies and oligopolies (Lewis 1966: 13– 24). CHAPTER 18 ©E. Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 26

Public expenditures n n Planners should ask each government department to submit proposals for expenditures, with estimation of financial costs and benefits, based on feasibility studies, during the plan period. Government must estimate the effects of current (noncapital), recurrent (spending on continuing programs), new capital programs and their future, recurrent expenditures. Current costs of government are typically several times capital costs yearly. CHAPTER 18 ©E. Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 27

Public expenditures n n Planners should ask each government department to submit proposals for expenditures, with estimation of financial costs and benefits, based on feasibility studies, during the plan period. Government must estimate the effects of current (noncapital), recurrent (spending on continuing programs), new capital programs and their future, recurrent expenditures. Current costs of government are typically several times capital costs yearly. CHAPTER 18 ©E. Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 27

Public expenditures § Planners must set priorities, including size § and timing. Government needs competent executives, administrators, and technicians experienced in conceiving projects, starting them, keeping them on schedule, amending them, and evaluating them, prerequisites for successful development planning. CHAPTER 18 ©E. Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 28

Public expenditures § Planners must set priorities, including size § and timing. Government needs competent executives, administrators, and technicians experienced in conceiving projects, starting them, keeping them on schedule, amending them, and evaluating them, prerequisites for successful development planning. CHAPTER 18 ©E. Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 28