bee462a2b2f2514c4e6164788e0cb1ca.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 119

Chapter 13 Game Theory and Competitive Strategy

Chapter 13 Game Theory and Competitive Strategy

Topics to be Discussed l Gaming and Strategic Decisions l Dominant Strategies l The Nash Equilibrium Revisited l Repeated Games © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 2

Topics to be Discussed l Gaming and Strategic Decisions l Dominant Strategies l The Nash Equilibrium Revisited l Repeated Games © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 2

Topics to be Discussed l Sequential Games l Threats, Commitments, and Credibility l Entry Deterrence l Bargaining Strategy l Auctions © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 3

Topics to be Discussed l Sequential Games l Threats, Commitments, and Credibility l Entry Deterrence l Bargaining Strategy l Auctions © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 3

Gaming and Strategic Decisions l Game is any situation in which players (the participants) make strategic decisions. m Ex: firms competing with each other by setting prices, group of consumers bidding against each other in an auction l Strategic decisions result in payoffs to the players: outcomes that generate rewards or benefits © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 4

Gaming and Strategic Decisions l Game is any situation in which players (the participants) make strategic decisions. m Ex: firms competing with each other by setting prices, group of consumers bidding against each other in an auction l Strategic decisions result in payoffs to the players: outcomes that generate rewards or benefits © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 4

Gaming and Strategic Decisions l Game theory tries to determine optimal strategy for each player l Strategy is a rule or plan of action for playing the game l Optimal strategy for a player is one that maximizes the expected payoff l We consider players who are rational – they think through their actions © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 5

Gaming and Strategic Decisions l Game theory tries to determine optimal strategy for each player l Strategy is a rule or plan of action for playing the game l Optimal strategy for a player is one that maximizes the expected payoff l We consider players who are rational – they think through their actions © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 5

Gaming and Strategic Decisions l “If I believe that my competitors are rational and act to maximize their own profits, how should I take their behavior into account when making my own profitmaximizing decisions? ” © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 6

Gaming and Strategic Decisions l “If I believe that my competitors are rational and act to maximize their own profits, how should I take their behavior into account when making my own profitmaximizing decisions? ” © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 6

Noncooperative v. Cooperative Games l Cooperative Game m Players negotiate binding contracts that allow them to plan joint strategies l Example: Buyer and seller negotiating the price of a good or service or a joint venture by two firms (i. e. Microsoft and Apple) l Binding contracts are possible © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 7

Noncooperative v. Cooperative Games l Cooperative Game m Players negotiate binding contracts that allow them to plan joint strategies l Example: Buyer and seller negotiating the price of a good or service or a joint venture by two firms (i. e. Microsoft and Apple) l Binding contracts are possible © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 7

Noncooperative v. Cooperative Games l Noncooperative Game m Negotiation and enforcement of binding contracts between players is not possible l Example: Two competing firms assuming the others behavior determine, independently, pricing and advertising strategy to gain market share l Binding contracts are not possible © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 8

Noncooperative v. Cooperative Games l Noncooperative Game m Negotiation and enforcement of binding contracts between players is not possible l Example: Two competing firms assuming the others behavior determine, independently, pricing and advertising strategy to gain market share l Binding contracts are not possible © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 8

Noncooperative v. Cooperative Games l “The strategy design is based on understanding your opponent’s point of view, and (assuming you opponent is rational) deducing how he or she is likely to respond to your actions” © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 9

Noncooperative v. Cooperative Games l “The strategy design is based on understanding your opponent’s point of view, and (assuming you opponent is rational) deducing how he or she is likely to respond to your actions” © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 9

Gaming and Strategic Decisions l An Example: How to buy a dollar bill 1. 2. 3. 4. Auction a dollar bill Highest bidder receives the dollar in return for the amount bid Second highest bidder must pay the amount he or she bid but gets nothing in return How much would you bid for a dollar? l Typically bid more for the dollar when faced with loss as second highest bidder © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 10

Gaming and Strategic Decisions l An Example: How to buy a dollar bill 1. 2. 3. 4. Auction a dollar bill Highest bidder receives the dollar in return for the amount bid Second highest bidder must pay the amount he or she bid but gets nothing in return How much would you bid for a dollar? l Typically bid more for the dollar when faced with loss as second highest bidder © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 10

Acquiring a Company l Scenario m Company A: The Acquirer m Company T: The Target m A will offer cash for all of T’s shares l The value and viability of T depends on the outcome of a current oil exploration project © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 11

Acquiring a Company l Scenario m Company A: The Acquirer m Company T: The Target m A will offer cash for all of T’s shares l The value and viability of T depends on the outcome of a current oil exploration project © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 11

Acquiring a Company l Project failure: T’s value = $0 l Project success: T’s value = $100/share l All outcomes in between equally likely l T’s value will be 50% greater with A’s management © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 12

Acquiring a Company l Project failure: T’s value = $0 l Project success: T’s value = $100/share l All outcomes in between equally likely l T’s value will be 50% greater with A’s management © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 12

Acquiring a Company l Scenario m A, must submit the proposal before the exploration outcome is known. m T will not choose to accept or reject until after the outcome is known only to T. m Company T will accept any offer that is greater than the per share value of the company under current management? l How much should A offer? © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 13

Acquiring a Company l Scenario m A, must submit the proposal before the exploration outcome is known. m T will not choose to accept or reject until after the outcome is known only to T. m Company T will accept any offer that is greater than the per share value of the company under current management? l How much should A offer? © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 13

Dominant Strategies l Dominant Strategy is one that is optimal no matter what an opponent does. m An Example l. A & B sell competing products l They are deciding whether to undertake advertising campaigns © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 14

Dominant Strategies l Dominant Strategy is one that is optimal no matter what an opponent does. m An Example l. A & B sell competing products l They are deciding whether to undertake advertising campaigns © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 14

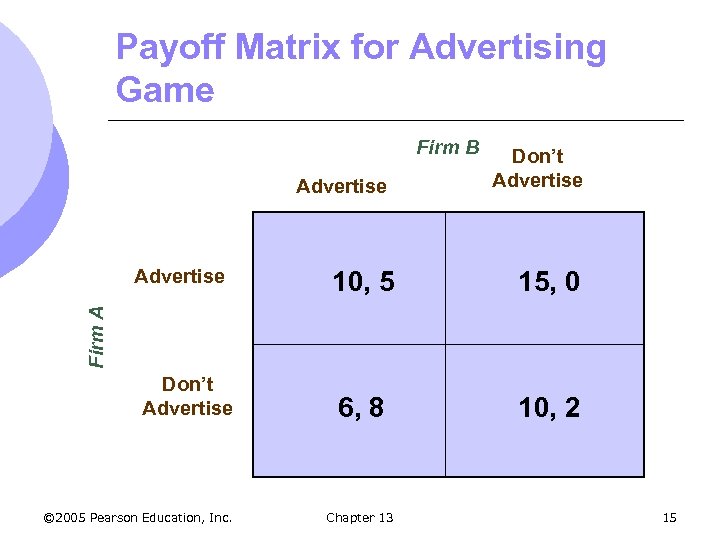

Payoff Matrix for Advertising Game Firm B Advertise 10, 5 15, 0 6, 8 10, 2 Firm A Advertise Don’t Advertise © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 15

Payoff Matrix for Advertising Game Firm B Advertise 10, 5 15, 0 6, 8 10, 2 Firm A Advertise Don’t Advertise © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 15

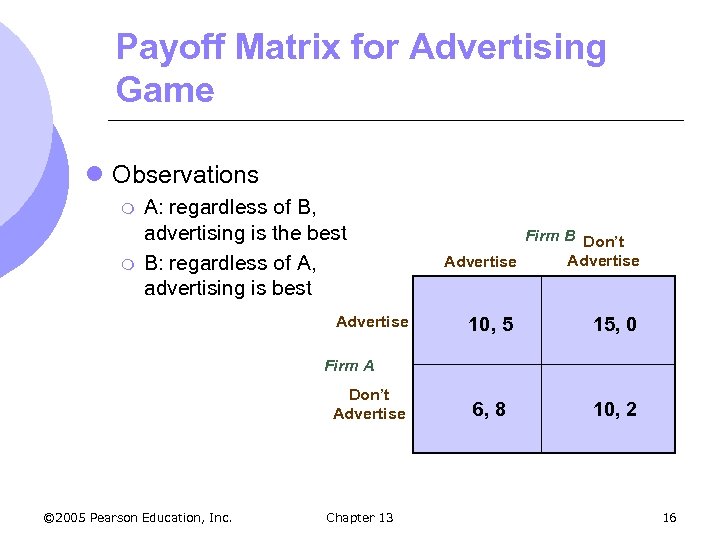

Payoff Matrix for Advertising Game l Observations m m A: regardless of B, advertising is the best B: regardless of A, advertising is best Advertise Firm B Don’t Advertise 10, 5 15, 0 6, 8 10, 2 Firm A Don’t Advertise © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 16

Payoff Matrix for Advertising Game l Observations m m A: regardless of B, advertising is the best B: regardless of A, advertising is best Advertise Firm B Don’t Advertise 10, 5 15, 0 6, 8 10, 2 Firm A Don’t Advertise © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 16

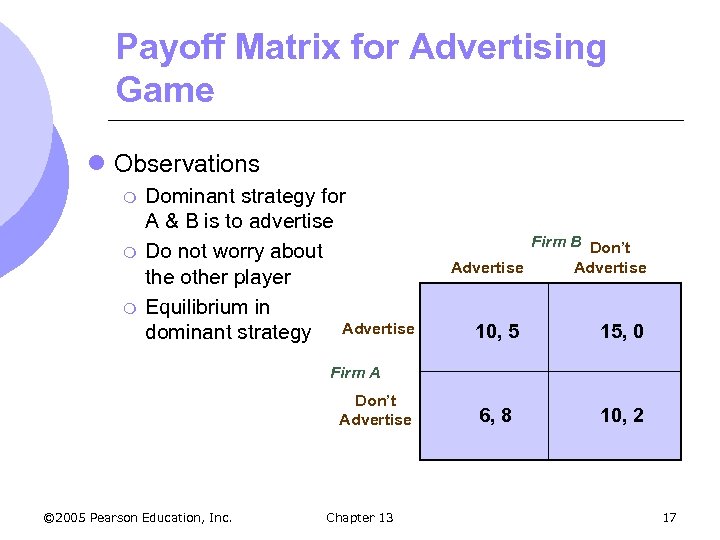

Payoff Matrix for Advertising Game l Observations m m m Dominant strategy for A & B is to advertise Do not worry about the other player Equilibrium in dominant strategy Advertise Firm B Don’t Advertise 10, 5 15, 0 6, 8 10, 2 Firm A Don’t Advertise © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 17

Payoff Matrix for Advertising Game l Observations m m m Dominant strategy for A & B is to advertise Do not worry about the other player Equilibrium in dominant strategy Advertise Firm B Don’t Advertise 10, 5 15, 0 6, 8 10, 2 Firm A Don’t Advertise © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 17

Dominant Strategies l Equilibrium in dominant strategies m Outcome of a game in which each firm is doing the best it can regardless of what its competitors are doing m Optimal strategy is determined without worrying about actions of other players l However, not every game has a dominant strategy for each player © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 18

Dominant Strategies l Equilibrium in dominant strategies m Outcome of a game in which each firm is doing the best it can regardless of what its competitors are doing m Optimal strategy is determined without worrying about actions of other players l However, not every game has a dominant strategy for each player © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 18

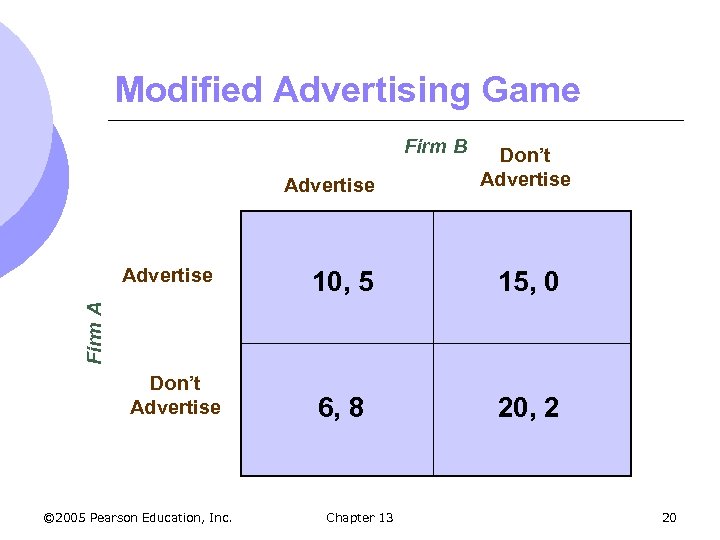

Dominant Strategies l Game Without Dominant Strategy m The optimal decision of a player without a dominant strategy will depend on what the other player does. m Revising the payoff matrix we can see a situation where no dominant strategy exists © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 19

Dominant Strategies l Game Without Dominant Strategy m The optimal decision of a player without a dominant strategy will depend on what the other player does. m Revising the payoff matrix we can see a situation where no dominant strategy exists © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 19

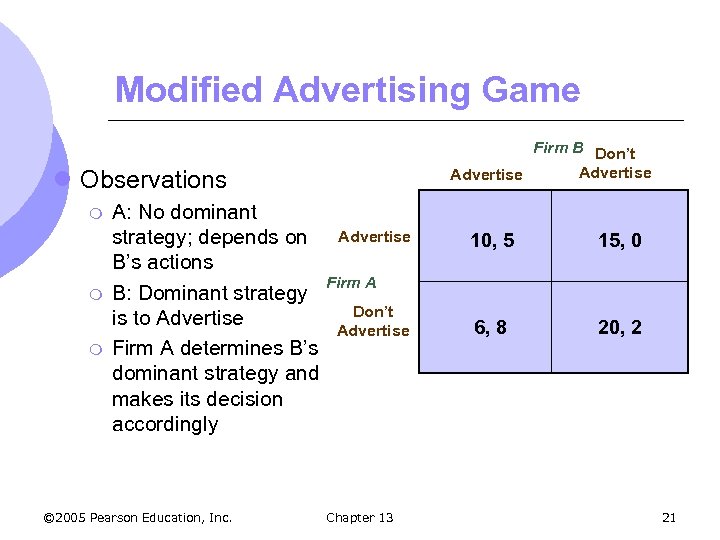

Modified Advertising Game Firm B Advertise 10, 5 15, 0 6, 8 20, 2 Firm A Advertise Don’t Advertise © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 20

Modified Advertising Game Firm B Advertise 10, 5 15, 0 6, 8 20, 2 Firm A Advertise Don’t Advertise © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 20

Modified Advertising Game Firm B Don’t Advertise l Observations m m m A: No dominant strategy; depends on B’s actions B: Dominant strategy is to Advertise Firm A determines B’s dominant strategy and makes its decision accordingly © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Advertise 10, 5 15, 0 6, 8 20, 2 Firm A Don’t Advertise Chapter 13 21

Modified Advertising Game Firm B Don’t Advertise l Observations m m m A: No dominant strategy; depends on B’s actions B: Dominant strategy is to Advertise Firm A determines B’s dominant strategy and makes its decision accordingly © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Advertise 10, 5 15, 0 6, 8 20, 2 Firm A Don’t Advertise Chapter 13 21

The Nash Equilibrium Revisited l A dominant strategy is stable, but in many games one or more party does not have a dominant strategy. l A more general equilibrium concept is the Nash Equilibrium introduced in chapter 12 m. A set of strategies (or actions) such that each player is doing the best it can given the actions of its opponents © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 22

The Nash Equilibrium Revisited l A dominant strategy is stable, but in many games one or more party does not have a dominant strategy. l A more general equilibrium concept is the Nash Equilibrium introduced in chapter 12 m. A set of strategies (or actions) such that each player is doing the best it can given the actions of its opponents © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 22

The Nash Equilibrium Revisited l None of the players have incentive to deviate from its Nash strategy, therefore it is stable m In the Cournot model, each firm sets its own price assuming the other firms outputs are fixed. Cournot equilibrium is a Nash Equilibrium © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 23

The Nash Equilibrium Revisited l None of the players have incentive to deviate from its Nash strategy, therefore it is stable m In the Cournot model, each firm sets its own price assuming the other firms outputs are fixed. Cournot equilibrium is a Nash Equilibrium © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 23

The Nash Equilibrium Revisited l Dominant Strategy m “I’m doing the best I can no matter what you do. You’re doing the best you can no matter what I do. ” l Nash Equilibrium m “I’m doing the best I can given what you are doing. You’re doing the best you can given what I am doing. ” l Dominant strategy is special case of Nash equilibrium © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 24

The Nash Equilibrium Revisited l Dominant Strategy m “I’m doing the best I can no matter what you do. You’re doing the best you can no matter what I do. ” l Nash Equilibrium m “I’m doing the best I can given what you are doing. You’re doing the best you can given what I am doing. ” l Dominant strategy is special case of Nash equilibrium © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 24

The Nash Equilibrium Revisited l Two cereal companies face a market in which two new types of cereal can be successfully introduced provided each type is introduced by only one firm l Product Choice Problem m m Market for one producer of crispy cereal Market for one producer of sweet cereal Each firm only has the resources to introduce one cereal Noncooperative © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 25

The Nash Equilibrium Revisited l Two cereal companies face a market in which two new types of cereal can be successfully introduced provided each type is introduced by only one firm l Product Choice Problem m m Market for one producer of crispy cereal Market for one producer of sweet cereal Each firm only has the resources to introduce one cereal Noncooperative © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 25

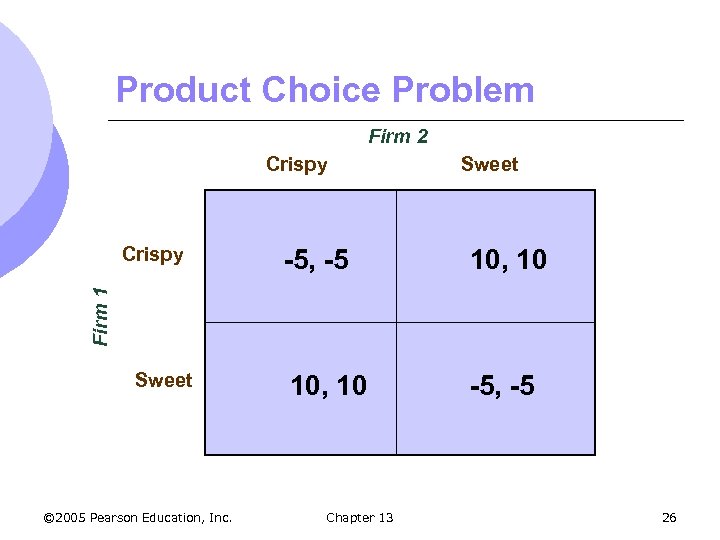

Product Choice Problem Firm 2 Crispy -5, -5 10, 10 -5, -5 Firm 1 Crispy Sweet © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 26

Product Choice Problem Firm 2 Crispy -5, -5 10, 10 -5, -5 Firm 1 Crispy Sweet © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 26

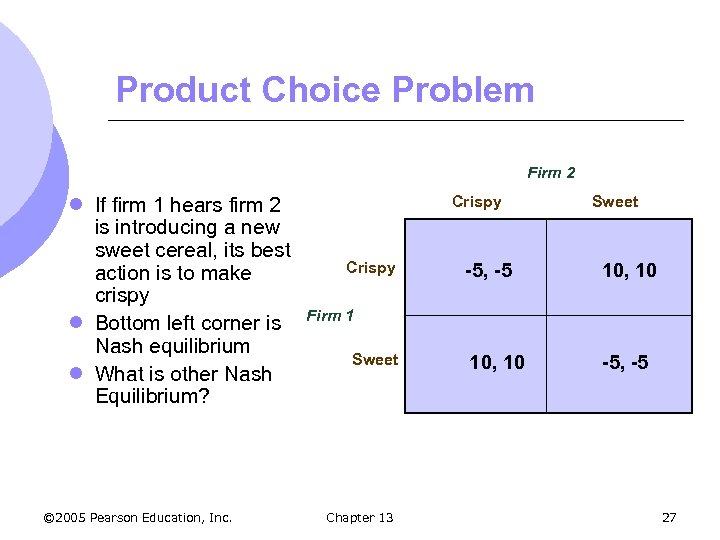

Product Choice Problem Firm 2 l If firm 1 hears firm 2 is introducing a new sweet cereal, its best action is to make crispy l Bottom left corner is Nash equilibrium l What is other Nash Equilibrium? © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Crispy Sweet -5, -5 10, 10 -5, -5 Firm 1 Sweet Chapter 13 27

Product Choice Problem Firm 2 l If firm 1 hears firm 2 is introducing a new sweet cereal, its best action is to make crispy l Bottom left corner is Nash equilibrium l What is other Nash Equilibrium? © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Crispy Sweet -5, -5 10, 10 -5, -5 Firm 1 Sweet Chapter 13 27

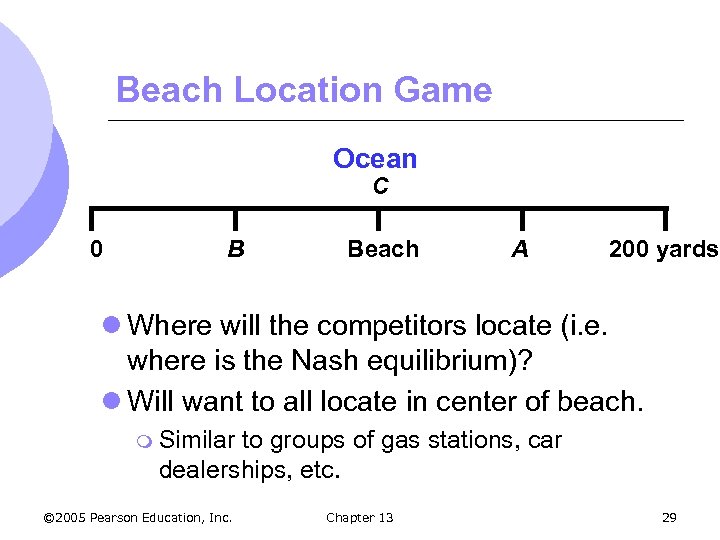

Beach Location Game l Scenario m Two competitors, Y and C, selling soft drinks m Beach 200 yards long m Sunbathers are spread evenly along the beach m Price Y = Price C m Customer will buy from the closest vendor © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 28

Beach Location Game l Scenario m Two competitors, Y and C, selling soft drinks m Beach 200 yards long m Sunbathers are spread evenly along the beach m Price Y = Price C m Customer will buy from the closest vendor © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 28

Beach Location Game Ocean C 0 B Beach A 200 yards l Where will the competitors locate (i. e. where is the Nash equilibrium)? l Will want to all locate in center of beach. m Similar to groups of gas stations, car dealerships, etc. © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 29

Beach Location Game Ocean C 0 B Beach A 200 yards l Where will the competitors locate (i. e. where is the Nash equilibrium)? l Will want to all locate in center of beach. m Similar to groups of gas stations, car dealerships, etc. © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 29

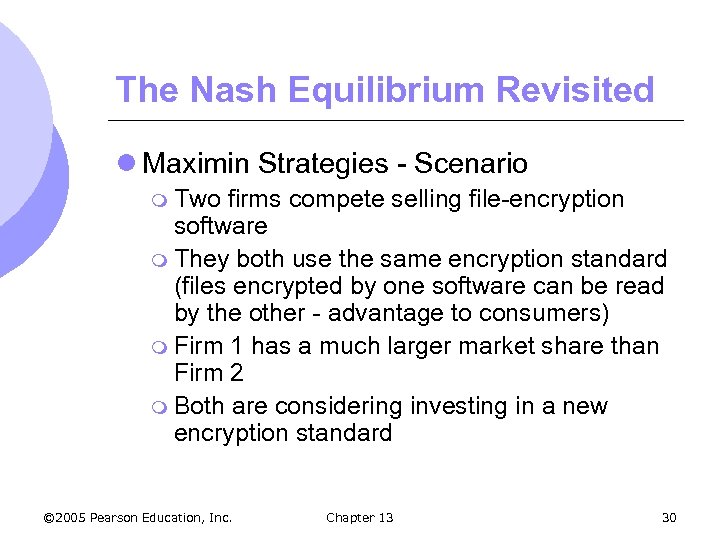

The Nash Equilibrium Revisited l Maximin Strategies - Scenario m Two firms compete selling file-encryption software m They both use the same encryption standard (files encrypted by one software can be read by the other - advantage to consumers) m Firm 1 has a much larger market share than Firm 2 m Both are considering investing in a new encryption standard © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 30

The Nash Equilibrium Revisited l Maximin Strategies - Scenario m Two firms compete selling file-encryption software m They both use the same encryption standard (files encrypted by one software can be read by the other - advantage to consumers) m Firm 1 has a much larger market share than Firm 2 m Both are considering investing in a new encryption standard © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 30

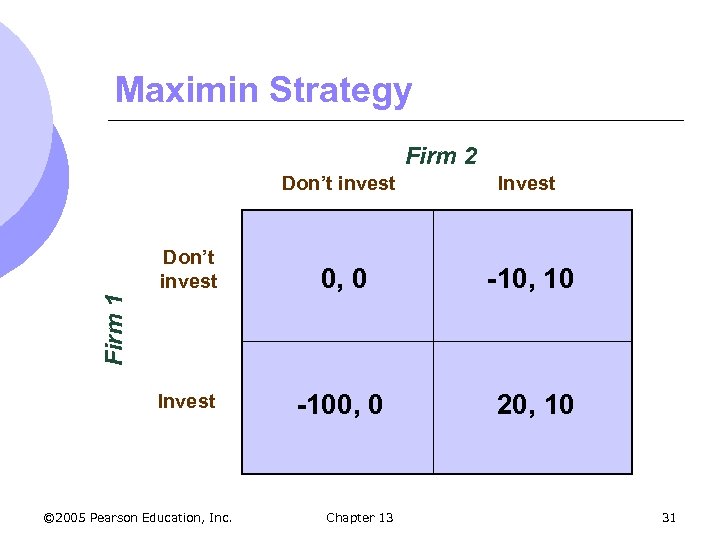

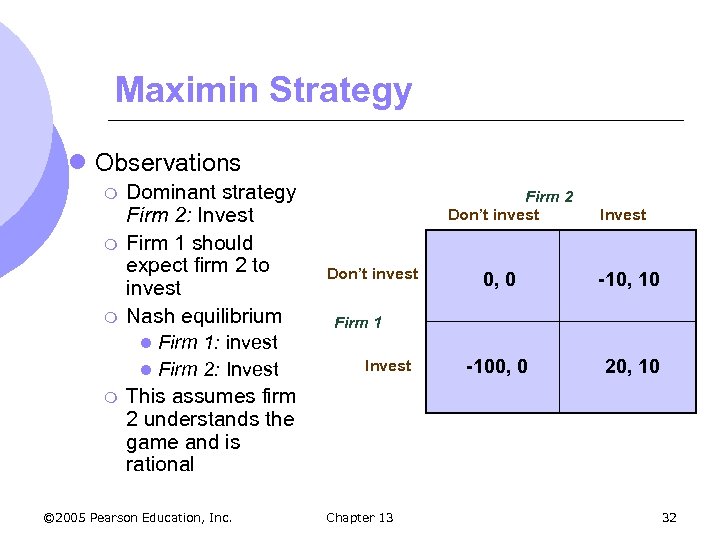

Maximin Strategy Firm 2 Invest Don’t invest 0, 0 -10, 10 Invest -100, 0 20, 10 Firm 1 Don’t invest © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 31

Maximin Strategy Firm 2 Invest Don’t invest 0, 0 -10, 10 Invest -100, 0 20, 10 Firm 1 Don’t invest © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 31

Maximin Strategy l Observations m m Dominant strategy Firm 2: Invest Firm 1 should expect firm 2 to invest Nash equilibrium l Firm 1: invest l Firm 2: Invest This assumes firm 2 understands the game and is rational © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Firm 2 Don’t invest Invest 0, 0 -10, 10 -100, 0 20, 10 Firm 1 Invest Chapter 13 32

Maximin Strategy l Observations m m Dominant strategy Firm 2: Invest Firm 1 should expect firm 2 to invest Nash equilibrium l Firm 1: invest l Firm 2: Invest This assumes firm 2 understands the game and is rational © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Firm 2 Don’t invest Invest 0, 0 -10, 10 -100, 0 20, 10 Firm 1 Invest Chapter 13 32

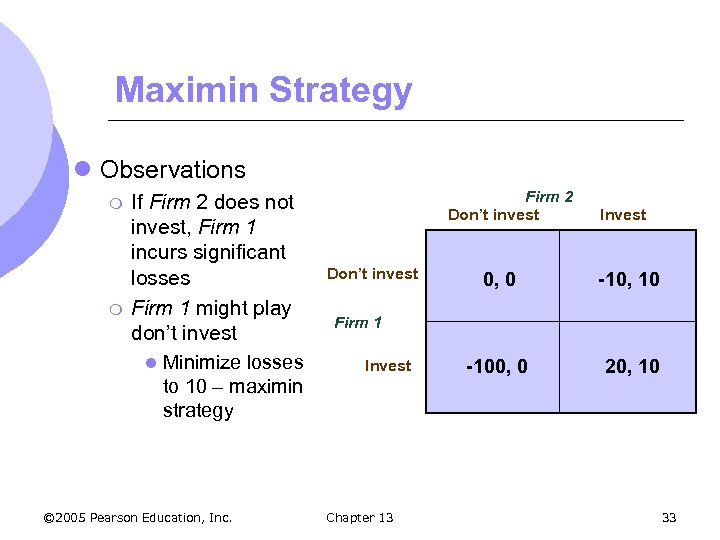

Maximin Strategy l Observations m m If Firm 2 does not invest, Firm 1 incurs significant losses Firm 1 might play don’t invest l Minimize losses to 10 – maximin strategy © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Firm 2 Don’t invest Invest 0, 0 -10, 10 -100, 0 20, 10 Firm 1 Invest Chapter 13 33

Maximin Strategy l Observations m m If Firm 2 does not invest, Firm 1 incurs significant losses Firm 1 might play don’t invest l Minimize losses to 10 – maximin strategy © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Firm 2 Don’t invest Invest 0, 0 -10, 10 -100, 0 20, 10 Firm 1 Invest Chapter 13 33

Maximin Strategy l If both are rational and informed m Both firms invest m Nash equilibrium l If Player 2 is not rational or completely informed m Firm 1’s maximin strategy is to not invest m Firm 2’s maximin strategy is to invest. m If 1 knows 2 is using a maximin strategy, 1 would invest © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 34

Maximin Strategy l If both are rational and informed m Both firms invest m Nash equilibrium l If Player 2 is not rational or completely informed m Firm 1’s maximin strategy is to not invest m Firm 2’s maximin strategy is to invest. m If 1 knows 2 is using a maximin strategy, 1 would invest © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 34

Maximin Strategy l If firm 1 is unsure about what firm 2 will do, it can assign probabilities to each possible action m Could use a strategy that maximizes its expected payoff m Firm 1’s strategy depends critically on its assessment of probabilities for firm 2 © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 35

Maximin Strategy l If firm 1 is unsure about what firm 2 will do, it can assign probabilities to each possible action m Could use a strategy that maximizes its expected payoff m Firm 1’s strategy depends critically on its assessment of probabilities for firm 2 © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 35

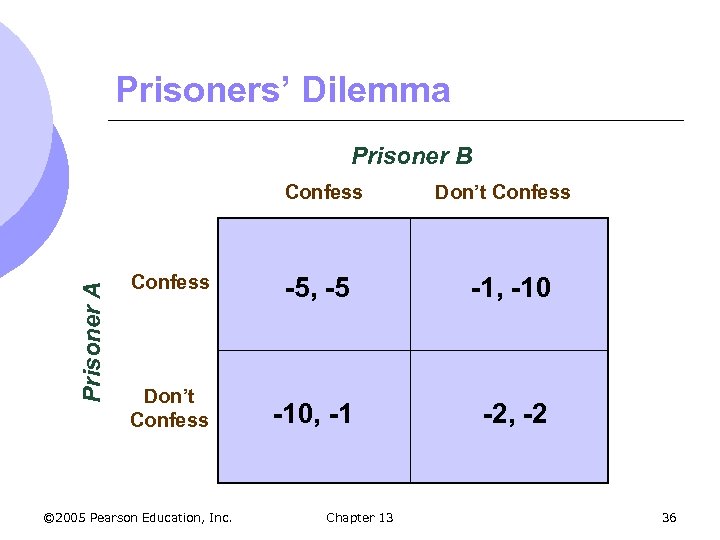

Prisoners’ Dilemma Prisoner B Prisoner A Confess Don’t Confess -5, -5 -1, -10 Don’t Confess -10, -1 -2, -2 © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 36

Prisoners’ Dilemma Prisoner B Prisoner A Confess Don’t Confess -5, -5 -1, -10 Don’t Confess -10, -1 -2, -2 © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 36

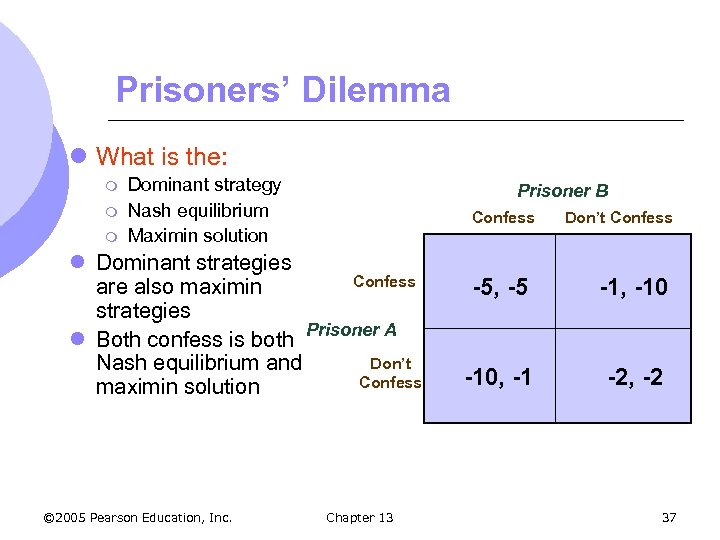

Prisoners’ Dilemma l What is the: m m m Dominant strategy Nash equilibrium Maximin solution Prisoner B Confess l Dominant strategies Confess are also maximin strategies l Both confess is both Prisoner A Don’t Nash equilibrium and Confess maximin solution © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 Don’t Confess -5, -5 -1, -10, -1 -2, -2 37

Prisoners’ Dilemma l What is the: m m m Dominant strategy Nash equilibrium Maximin solution Prisoner B Confess l Dominant strategies Confess are also maximin strategies l Both confess is both Prisoner A Don’t Nash equilibrium and Confess maximin solution © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 Don’t Confess -5, -5 -1, -10, -1 -2, -2 37

Mixed Strategy l Pure Strategy m Player makes a specific choice or takes a specific action l Mixed Strategy m Player makes a random choice among two or more possible actions, based on a set of chosen probabilities © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 38

Mixed Strategy l Pure Strategy m Player makes a specific choice or takes a specific action l Mixed Strategy m Player makes a random choice among two or more possible actions, based on a set of chosen probabilities © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 38

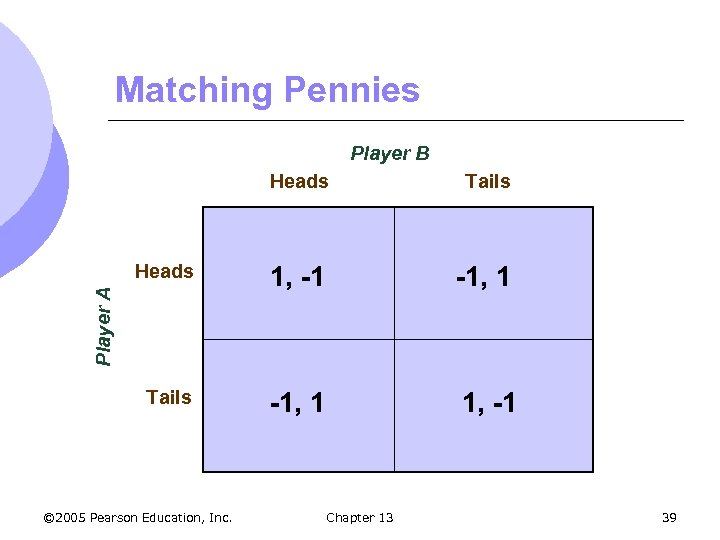

Matching Pennies Player B Tails Heads 1, -1 -1, 1 Tails -1, 1 1, -1 Player A Heads © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 39

Matching Pennies Player B Tails Heads 1, -1 -1, 1 Tails -1, 1 1, -1 Player A Heads © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 39

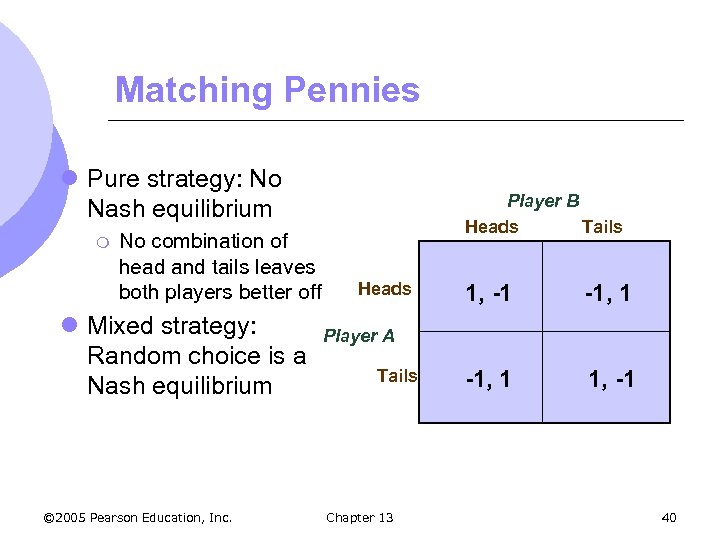

Matching Pennies l Pure strategy: No Nash equilibrium m No combination of head and tails leaves both players better off l Mixed strategy: Random choice is a Nash equilibrium © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Player B Heads Tails Heads 1, -1 -1, 1 1, -1 Player A Tails Chapter 13 40

Matching Pennies l Pure strategy: No Nash equilibrium m No combination of head and tails leaves both players better off l Mixed strategy: Random choice is a Nash equilibrium © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Player B Heads Tails Heads 1, -1 -1, 1 1, -1 Player A Tails Chapter 13 40

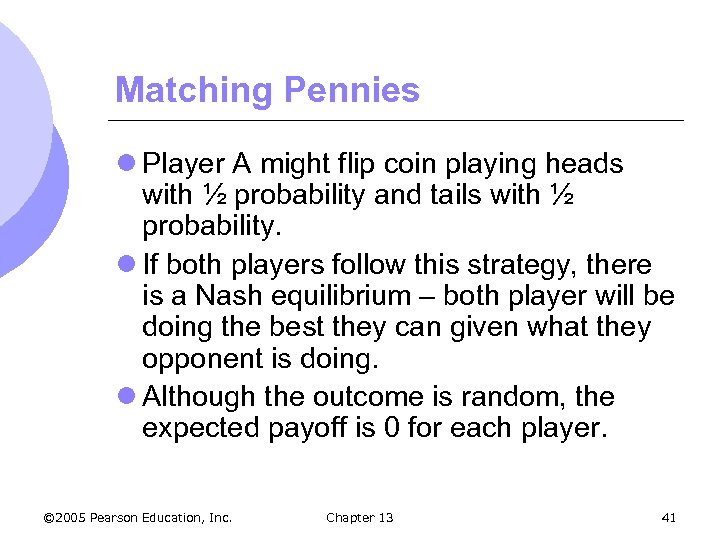

Matching Pennies l Player A might flip coin playing heads with ½ probability and tails with ½ probability. l If both players follow this strategy, there is a Nash equilibrium – both player will be doing the best they can given what they opponent is doing. l Although the outcome is random, the expected payoff is 0 for each player. © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 41

Matching Pennies l Player A might flip coin playing heads with ½ probability and tails with ½ probability. l If both players follow this strategy, there is a Nash equilibrium – both player will be doing the best they can given what they opponent is doing. l Although the outcome is random, the expected payoff is 0 for each player. © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 41

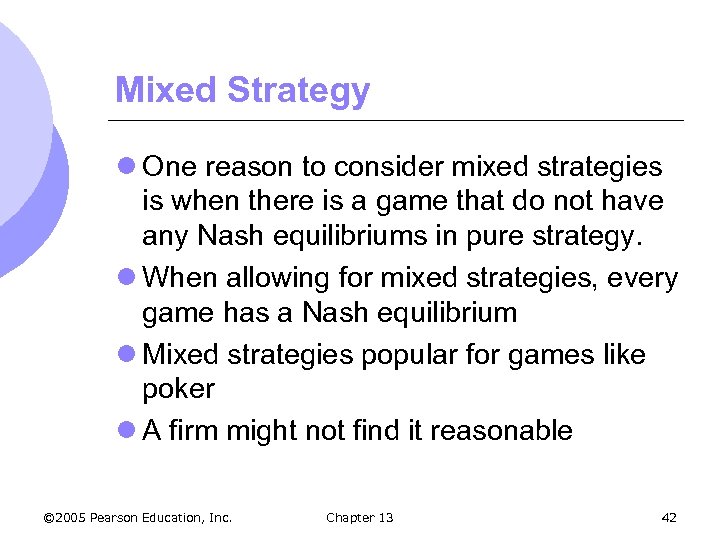

Mixed Strategy l One reason to consider mixed strategies is when there is a game that do not have any Nash equilibriums in pure strategy. l When allowing for mixed strategies, every game has a Nash equilibrium l Mixed strategies popular for games like poker l A firm might not find it reasonable © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 42

Mixed Strategy l One reason to consider mixed strategies is when there is a game that do not have any Nash equilibriums in pure strategy. l When allowing for mixed strategies, every game has a Nash equilibrium l Mixed strategies popular for games like poker l A firm might not find it reasonable © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 42

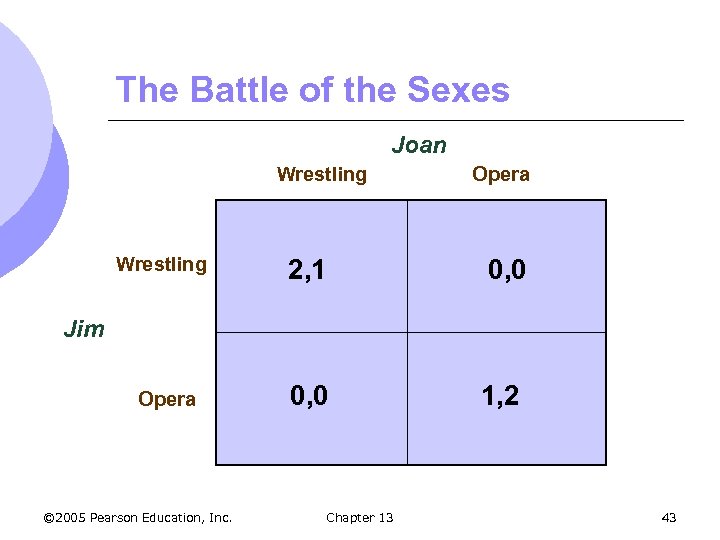

The Battle of the Sexes Joan Wrestling Opera Wrestling 2, 1 0, 0 Opera 0, 0 1, 2 Jim © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 43

The Battle of the Sexes Joan Wrestling Opera Wrestling 2, 1 0, 0 Opera 0, 0 1, 2 Jim © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 43

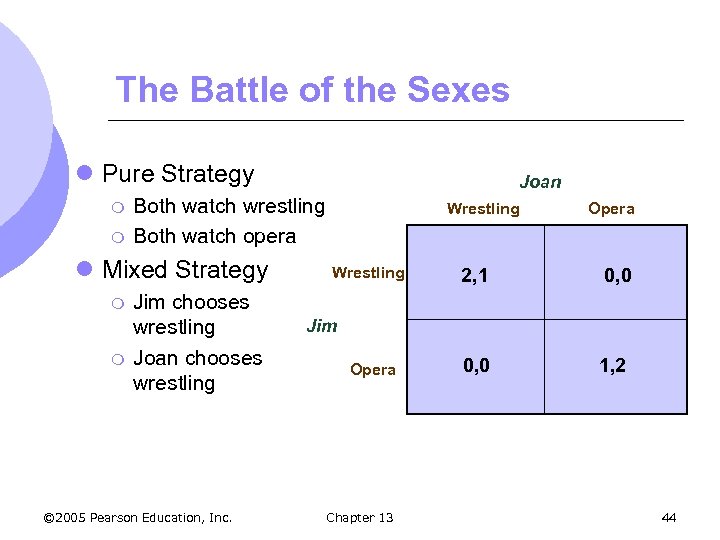

The Battle of the Sexes l Pure Strategy m m Both watch wrestling Both watch opera l Mixed Strategy m m Joan Jim chooses wrestling Joan chooses wrestling © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Wrestling Opera 2, 1 0, 0 1, 2 Jim Opera Chapter 13 44

The Battle of the Sexes l Pure Strategy m m Both watch wrestling Both watch opera l Mixed Strategy m m Joan Jim chooses wrestling Joan chooses wrestling © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Wrestling Opera 2, 1 0, 0 1, 2 Jim Opera Chapter 13 44

Repeated Games l Game in which actions are taken and payoffs received over and over again l Oligopolistic firms play a repeated game. l With each repetition of the Prisoners’ Dilemma, firms can develop reputations about their behavior and study the behavior of their competitors. © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 45

Repeated Games l Game in which actions are taken and payoffs received over and over again l Oligopolistic firms play a repeated game. l With each repetition of the Prisoners’ Dilemma, firms can develop reputations about their behavior and study the behavior of their competitors. © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 45

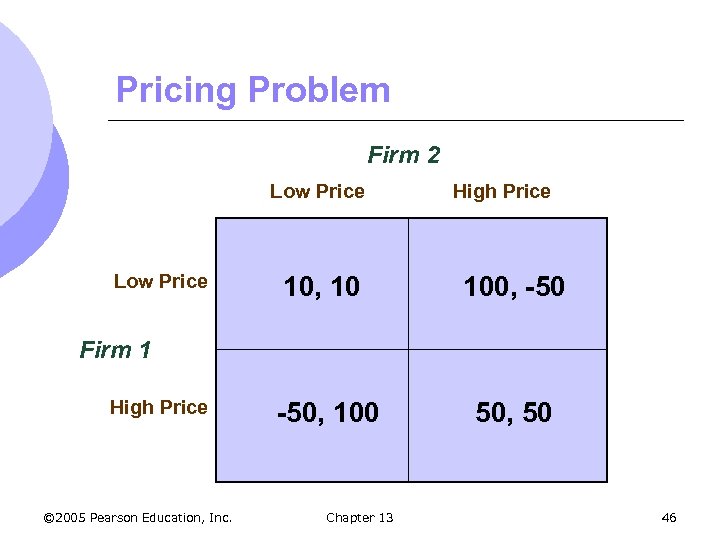

Pricing Problem Firm 2 Low Price High Price 10, 10 100, -50, 100 50, 50 Firm 1 High Price © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 46

Pricing Problem Firm 2 Low Price High Price 10, 10 100, -50, 100 50, 50 Firm 1 High Price © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 46

Pricing Problem l How does a firm find a strategy that would work best on average against all or almost all other strategies l Tit-for-tat strategy m Repeated game strategy in which a player responds in kink to an opponent’s previous play, cooperating with cooperative opponents and retaliating against uncooperative ones. © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 47

Pricing Problem l How does a firm find a strategy that would work best on average against all or almost all other strategies l Tit-for-tat strategy m Repeated game strategy in which a player responds in kink to an opponent’s previous play, cooperating with cooperative opponents and retaliating against uncooperative ones. © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 47

Tit-for-Tat Strategy l What if the game is infinitely repeated m Competitors repeatedly set price every month, forever m Tit-for-tat strategy is rational l If competitor charges low price and undercuts firm l Will get high profits that month but know I will lower price next month l Both of us will get lower profits if keep undercutting, so not rational to undercut. © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 48

Tit-for-Tat Strategy l What if the game is infinitely repeated m Competitors repeatedly set price every month, forever m Tit-for-tat strategy is rational l If competitor charges low price and undercuts firm l Will get high profits that month but know I will lower price next month l Both of us will get lower profits if keep undercutting, so not rational to undercut. © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 48

Tit-for-Tat Strategy l What if repeat a finite number of times m m If both firms are rational, they will charge high prices until the last month After the last month, there is no retaliation possible But in the month before last month, knowing that will charge low price in last month, will charge low price in month before Keep going and see that only rational outcome is for both firms to charge low price every month © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 49

Tit-for-Tat Strategy l What if repeat a finite number of times m m If both firms are rational, they will charge high prices until the last month After the last month, there is no retaliation possible But in the month before last month, knowing that will charge low price in last month, will charge low price in month before Keep going and see that only rational outcome is for both firms to charge low price every month © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 49

Tit-for-Tat Strategy l If firms don’t believe their competitors are rational or think perhaps they aren’t, cooperative behavior is a good strategy. l Most managers don’t know how long they will be competing with their rivals l In a repeated game, prisoners dilemma can have cooperative outcome © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 50

Tit-for-Tat Strategy l If firms don’t believe their competitors are rational or think perhaps they aren’t, cooperative behavior is a good strategy. l Most managers don’t know how long they will be competing with their rivals l In a repeated game, prisoners dilemma can have cooperative outcome © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 50

Repeated Games l Conclusion m Cooperation is difficult at best since these factors may change in the long-run. m Need a small number of firms m Need stable demand cost conditions l This © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. could lead to price wars if don’t have them Chapter 13 51

Repeated Games l Conclusion m Cooperation is difficult at best since these factors may change in the long-run. m Need a small number of firms m Need stable demand cost conditions l This © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. could lead to price wars if don’t have them Chapter 13 51

Oligopolistic Cooperation in the Water Meter Industry l Characteristics of the Market m Four producers of water meters l Rockwell International (35%) l Badger Meter l Neptune Water Meter Company l Hersey Products l Rockwell has about 35 % of market share l Badger, Neptune, and Hersey combined have about a 50 to 55% share © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 52

Oligopolistic Cooperation in the Water Meter Industry l Characteristics of the Market m Four producers of water meters l Rockwell International (35%) l Badger Meter l Neptune Water Meter Company l Hersey Products l Rockwell has about 35 % of market share l Badger, Neptune, and Hersey combined have about a 50 to 55% share © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 52

Oligopolistic Cooperation in the Water Meter Industry l Most buyers are municipal water utilities l Very inelastic demand m Not a significant part of the budget for providing water l Demand is stable m Demand grows steadily with population l Utilities have long-standing relationships with suppliers m Reluctant © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. to switch Chapter 13 53

Oligopolistic Cooperation in the Water Meter Industry l Most buyers are municipal water utilities l Very inelastic demand m Not a significant part of the budget for providing water l Demand is stable m Demand grows steadily with population l Utilities have long-standing relationships with suppliers m Reluctant © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. to switch Chapter 13 53

Oligopolistic Cooperation in the Water Meter Industry l Significant economies of scale l Both long term relationship and economies of scale represent barriers to entry m Hard for new firms to enter market l If firms were to cooperate, could earn significant monopoly profits l If compete aggressively to gain market share, profits will fall to competitive levels © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 54

Oligopolistic Cooperation in the Water Meter Industry l Significant economies of scale l Both long term relationship and economies of scale represent barriers to entry m Hard for new firms to enter market l If firms were to cooperate, could earn significant monopoly profits l If compete aggressively to gain market share, profits will fall to competitive levels © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 54

Oligopolistic Cooperation in the Water Meter Industry l This is a Prisoners’ Dilemma – what should the firms do? m Lower price to a competitive level m Cooperate l Companies have been playing repeated game for decades l Cooperation has prevailed given market characteristics © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 55

Oligopolistic Cooperation in the Water Meter Industry l This is a Prisoners’ Dilemma – what should the firms do? m Lower price to a competitive level m Cooperate l Companies have been playing repeated game for decades l Cooperation has prevailed given market characteristics © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 55

Sequential Games l Players move in turn, responding to each other’s actions and reactions m Ex: Stackelberg model (ch. 12) m Responding to a competitor’s ad campaign m Entry decisions m Responding to regulatory policy © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 56

Sequential Games l Players move in turn, responding to each other’s actions and reactions m Ex: Stackelberg model (ch. 12) m Responding to a competitor’s ad campaign m Entry decisions m Responding to regulatory policy © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 56

Sequential Games l Going back to the product choice problem m Two new (sweet, crispy) cereals m Successful only if each firm produces one cereal m Sweet will sell better m Both still profitable with only one producer © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 57

Sequential Games l Going back to the product choice problem m Two new (sweet, crispy) cereals m Successful only if each firm produces one cereal m Sweet will sell better m Both still profitable with only one producer © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 57

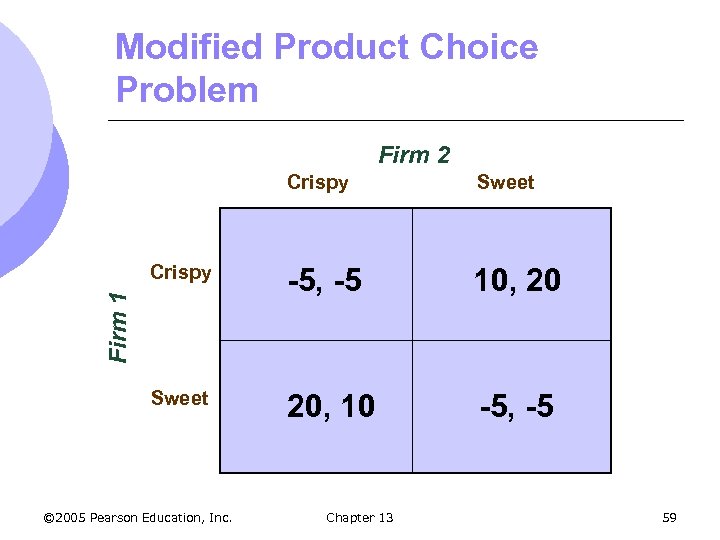

Modified Product Choice Problem l If firms both announce their decision independently and simultaneously, they will both pick sweet cereal and both will lose money l What if firm 1 sped up production and introduced new cereal first m Now there is a sequential game m Firm 1 think about what firm 2 will do © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 58

Modified Product Choice Problem l If firms both announce their decision independently and simultaneously, they will both pick sweet cereal and both will lose money l What if firm 1 sped up production and introduced new cereal first m Now there is a sequential game m Firm 1 think about what firm 2 will do © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 58

Modified Product Choice Problem Firm 2 Sweet Crispy -5, -5 10, 20 Sweet 20, 10 -5, -5 Firm 1 Crispy © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 59

Modified Product Choice Problem Firm 2 Sweet Crispy -5, -5 10, 20 Sweet 20, 10 -5, -5 Firm 1 Crispy © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 59

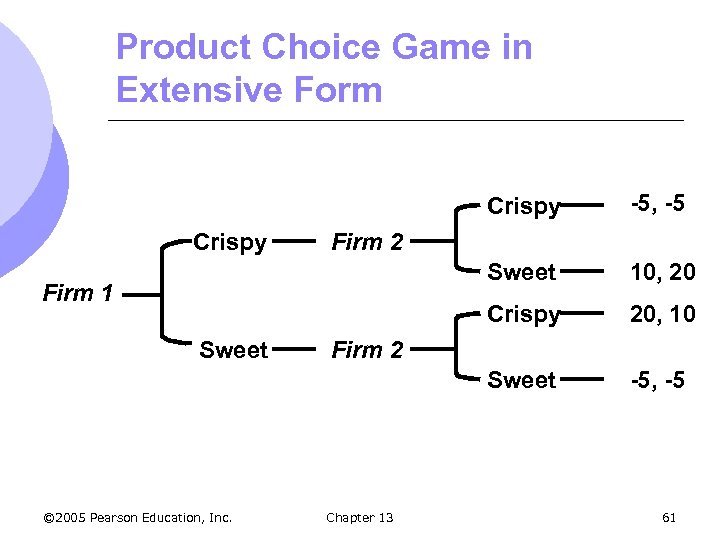

Extensive Form of a Game l Extensive Form of a Game m Representation of possible moves in a game in the form of a decision tree l Allows one to work backward from the best outcome for Firm 1 © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 60

Extensive Form of a Game l Extensive Form of a Game m Representation of possible moves in a game in the form of a decision tree l Allows one to work backward from the best outcome for Firm 1 © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 60

Product Choice Game in Extensive Form Crispy Sweet © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. 20, 10 -5, -5 Firm 2 Firm 1 Sweet 10, 20 Crispy -5, -5 Firm 2 Chapter 13 61

Product Choice Game in Extensive Form Crispy Sweet © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. 20, 10 -5, -5 Firm 2 Firm 1 Sweet 10, 20 Crispy -5, -5 Firm 2 Chapter 13 61

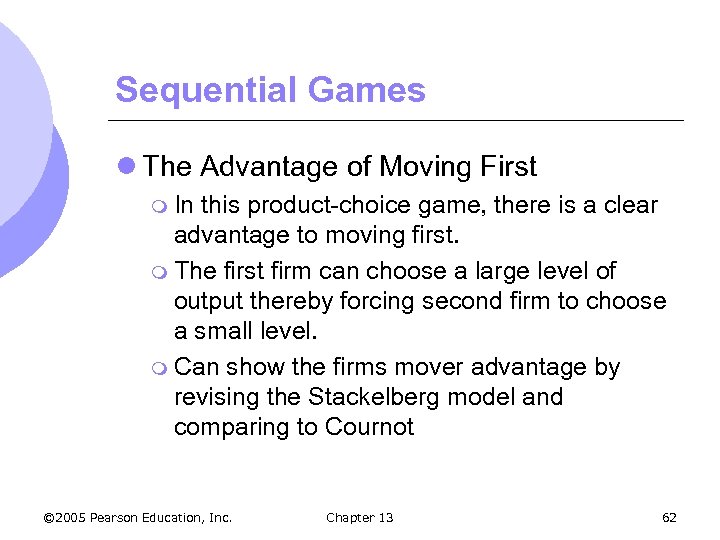

Sequential Games l The Advantage of Moving First m In this product-choice game, there is a clear advantage to moving first. m The first firm can choose a large level of output thereby forcing second firm to choose a small level. m Can show the firms mover advantage by revising the Stackelberg model and comparing to Cournot © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 62

Sequential Games l The Advantage of Moving First m In this product-choice game, there is a clear advantage to moving first. m The first firm can choose a large level of output thereby forcing second firm to choose a small level. m Can show the firms mover advantage by revising the Stackelberg model and comparing to Cournot © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 62

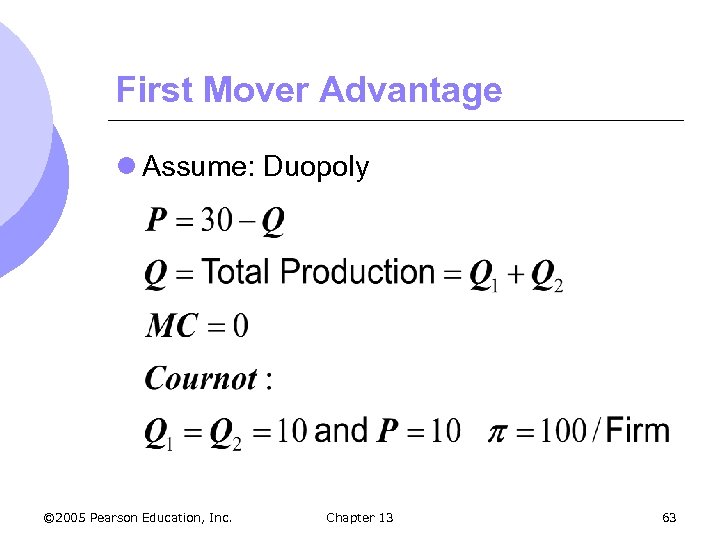

First Mover Advantage l Assume: Duopoly © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 63

First Mover Advantage l Assume: Duopoly © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 63

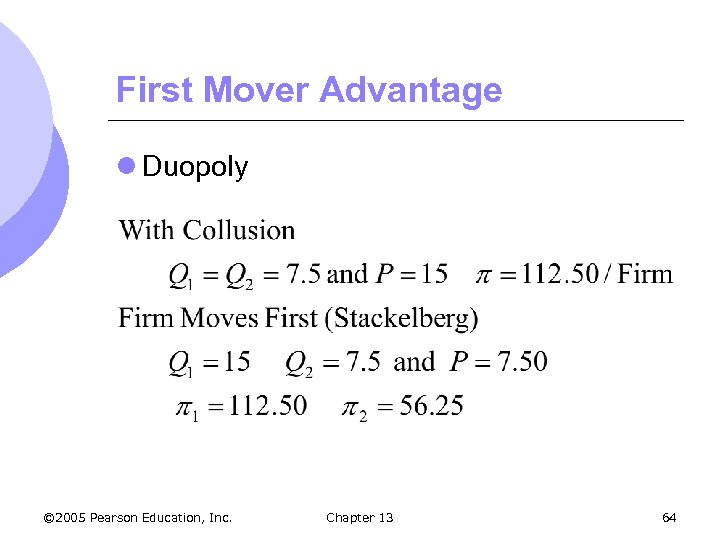

First Mover Advantage l Duopoly © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 64

First Mover Advantage l Duopoly © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 64

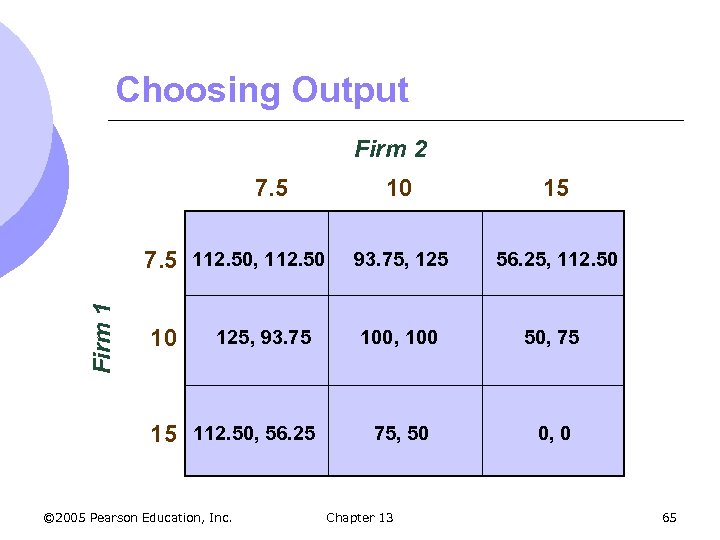

Choosing Output Firm 2 7. 5 Firm 1 7. 5 112. 50, 112. 50 10 125, 93. 75 15 112. 50, 56. 25 © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. 10 15 93. 75, 125 56. 25, 112. 50 100, 100 50, 75 75, 50 0, 0 Chapter 13 65

Choosing Output Firm 2 7. 5 Firm 1 7. 5 112. 50, 112. 50 10 125, 93. 75 15 112. 50, 56. 25 © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. 10 15 93. 75, 125 56. 25, 112. 50 100, 100 50, 75 75, 50 0, 0 Chapter 13 65

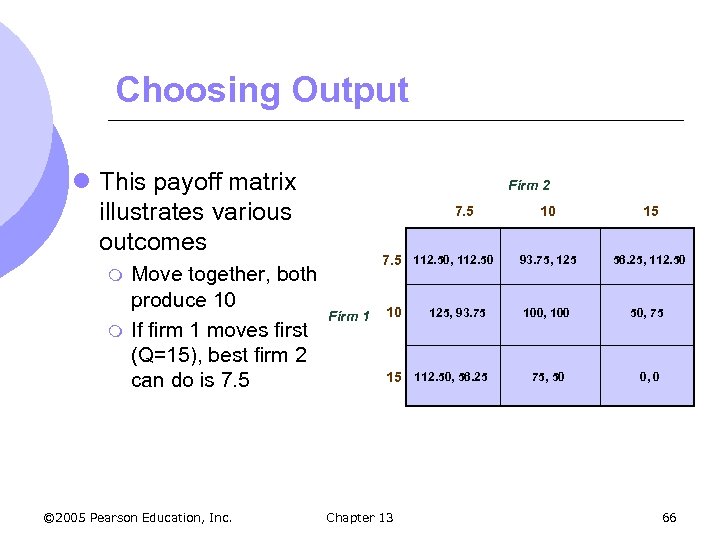

Choosing Output l This payoff matrix illustrates various outcomes m m Move together, both produce 10 If firm 1 moves first (Q=15), best firm 2 can do is 7. 5 © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Firm 2 7. 5 112. 50, 112. 50 Firm 1 10 125, 93. 75 15 112. 50, 56. 25 Chapter 13 10 15 93. 75, 125 56. 25, 112. 50 100, 100 50, 75 75, 50 0, 0 66

Choosing Output l This payoff matrix illustrates various outcomes m m Move together, both produce 10 If firm 1 moves first (Q=15), best firm 2 can do is 7. 5 © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Firm 2 7. 5 112. 50, 112. 50 Firm 1 10 125, 93. 75 15 112. 50, 56. 25 Chapter 13 10 15 93. 75, 125 56. 25, 112. 50 100, 100 50, 75 75, 50 0, 0 66

Threats, Commitments, and Credibility l Strategic Moves m What actions can a firm take to gain advantage in the marketplace? l Deter entry l Induce competitors to reduce output, leave, raise price l Implicit agreements that benefit one firm © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 67

Threats, Commitments, and Credibility l Strategic Moves m What actions can a firm take to gain advantage in the marketplace? l Deter entry l Induce competitors to reduce output, leave, raise price l Implicit agreements that benefit one firm © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 67

Threats, Commitments, and Credibility l Strategic Move m Action that gives a player an advantage by constraining his behavior m Firm 1 must constrain his behavior to the extent Firm 2 is convinced that he is committed © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 68

Threats, Commitments, and Credibility l Strategic Move m Action that gives a player an advantage by constraining his behavior m Firm 1 must constrain his behavior to the extent Firm 2 is convinced that he is committed © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 68

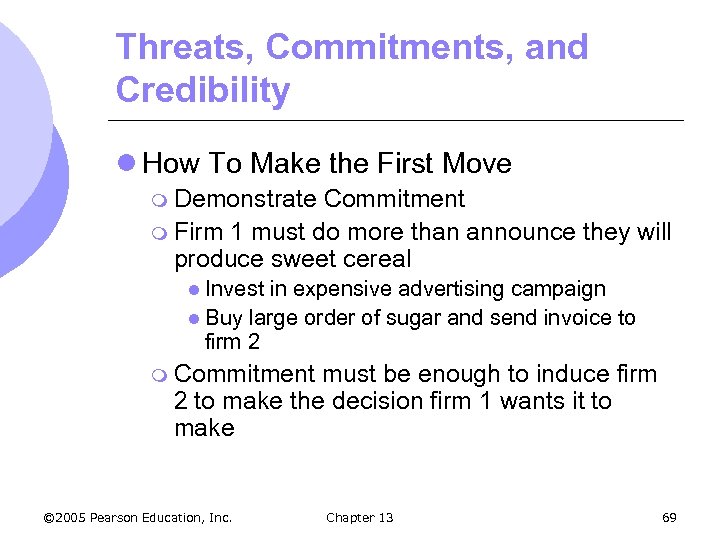

Threats, Commitments, and Credibility l How To Make the First Move m Demonstrate Commitment m Firm 1 must do more than announce they will produce sweet cereal l Invest in expensive advertising campaign l Buy large order of sugar and send invoice to firm 2 m Commitment must be enough to induce firm 2 to make the decision firm 1 wants it to make © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 69

Threats, Commitments, and Credibility l How To Make the First Move m Demonstrate Commitment m Firm 1 must do more than announce they will produce sweet cereal l Invest in expensive advertising campaign l Buy large order of sugar and send invoice to firm 2 m Commitment must be enough to induce firm 2 to make the decision firm 1 wants it to make © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 69

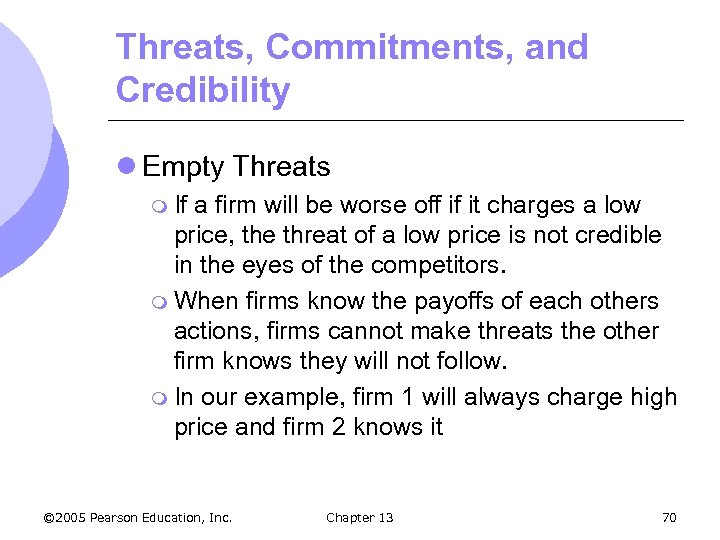

Threats, Commitments, and Credibility l Empty Threats m If a firm will be worse off if it charges a low price, the threat of a low price is not credible in the eyes of the competitors. m When firms know the payoffs of each others actions, firms cannot make threats the other firm knows they will not follow. m In our example, firm 1 will always charge high price and firm 2 knows it © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 70

Threats, Commitments, and Credibility l Empty Threats m If a firm will be worse off if it charges a low price, the threat of a low price is not credible in the eyes of the competitors. m When firms know the payoffs of each others actions, firms cannot make threats the other firm knows they will not follow. m In our example, firm 1 will always charge high price and firm 2 knows it © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 70

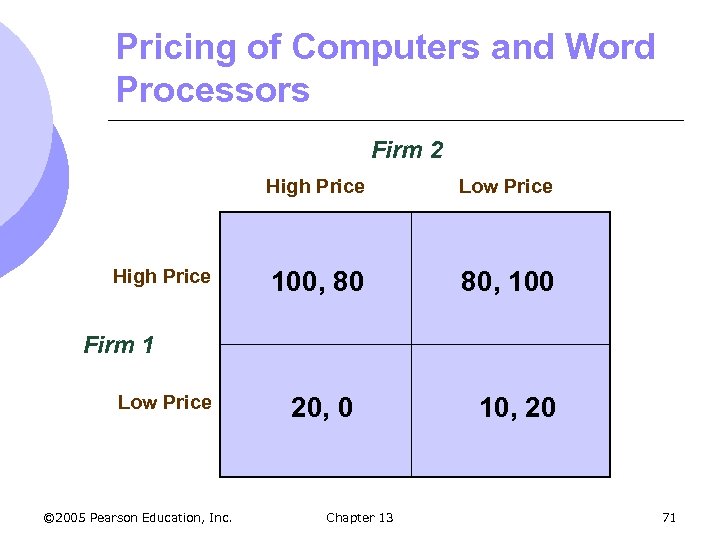

Pricing of Computers and Word Processors Firm 2 High Price Low Price 100, 80 80, 100 Firm 1 Low Price © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. 20, 0 Chapter 13 10, 20 71

Pricing of Computers and Word Processors Firm 2 High Price Low Price 100, 80 80, 100 Firm 1 Low Price © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. 20, 0 Chapter 13 10, 20 71

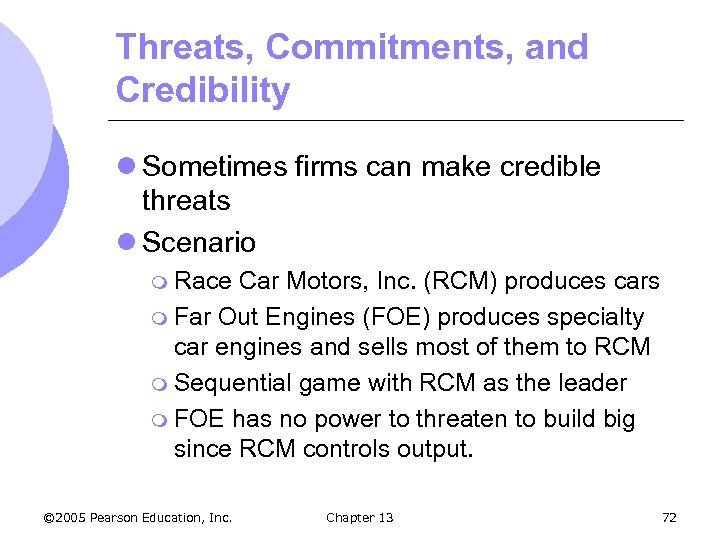

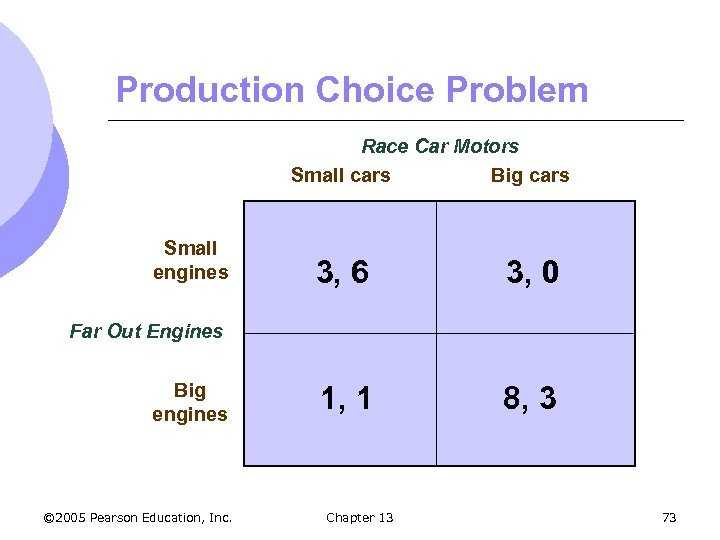

Threats, Commitments, and Credibility l Sometimes firms can make credible threats l Scenario m Race Car Motors, Inc. (RCM) produces cars m Far Out Engines (FOE) produces specialty car engines and sells most of them to RCM m Sequential game with RCM as the leader m FOE has no power to threaten to build big since RCM controls output. © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 72

Threats, Commitments, and Credibility l Sometimes firms can make credible threats l Scenario m Race Car Motors, Inc. (RCM) produces cars m Far Out Engines (FOE) produces specialty car engines and sells most of them to RCM m Sequential game with RCM as the leader m FOE has no power to threaten to build big since RCM controls output. © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 72

Production Choice Problem Race Car Motors Small cars Big cars Small engines 3, 6 3, 0 1, 1 8, 3 Far Out Engines Big engines © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 73

Production Choice Problem Race Car Motors Small cars Big cars Small engines 3, 6 3, 0 1, 1 8, 3 Far Out Engines Big engines © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 73

Threats, Commitments, and Credibility l RCM does best by producing small cars l Knows that Far Out will then produce small engines l Far Out prefers to make big engines l Can Far Out induce Race Car to produce big cars instead? © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 74

Threats, Commitments, and Credibility l RCM does best by producing small cars l Knows that Far Out will then produce small engines l Far Out prefers to make big engines l Can Far Out induce Race Car to produce big cars instead? © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 74

Threats, Commitments, and Credibility l Suppose Far Out threatens to produce big engines no matter what RCM does m Not credible since once RCM announces they are producing small cars, FO will not have incentive to carry out threat. m Can make threat credible by altering pay off matrix by constraining its own choices l Shutting down or destroying some small engine production capacity © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 75

Threats, Commitments, and Credibility l Suppose Far Out threatens to produce big engines no matter what RCM does m Not credible since once RCM announces they are producing small cars, FO will not have incentive to carry out threat. m Can make threat credible by altering pay off matrix by constraining its own choices l Shutting down or destroying some small engine production capacity © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 75

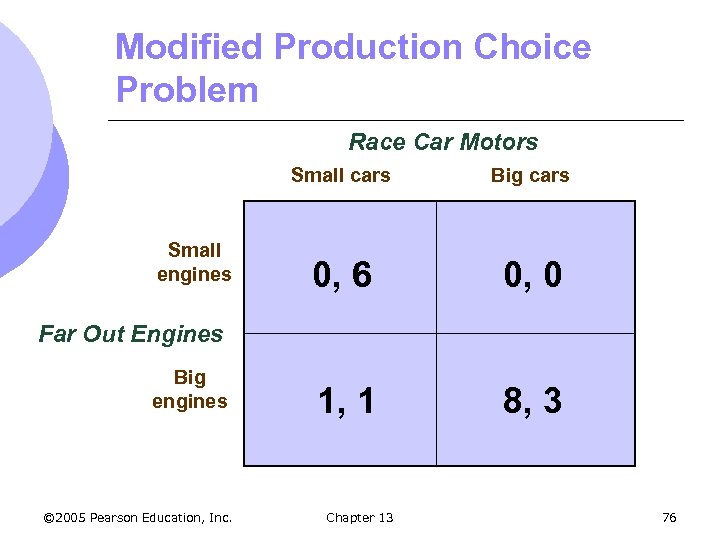

Modified Production Choice Problem Race Car Motors Small cars Small engines Big cars 0, 6 0, 0 1, 1 8, 3 Far Out Engines Big engines © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 76

Modified Production Choice Problem Race Car Motors Small cars Small engines Big cars 0, 6 0, 0 1, 1 8, 3 Far Out Engines Big engines © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 76

Modified Production Choice Problem l Strategic commitments can be effect but not without risk m Rely heavily on accurate knowledge of payoff matrix and industry m May have competitors out there that they don’t know about and lose sale © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 77

Modified Production Choice Problem l Strategic commitments can be effect but not without risk m Rely heavily on accurate knowledge of payoff matrix and industry m May have competitors out there that they don’t know about and lose sale © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 77

Role of Reputation l If Far Out gets the reputation of being irrational m They threaten to produce large engines not matter what Race Car does l Threat might be credible because irrational people don’t always make profit maximizing decisions l A party thought to be crazy can lead to a significant advantage © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 78

Role of Reputation l If Far Out gets the reputation of being irrational m They threaten to produce large engines not matter what Race Car does l Threat might be credible because irrational people don’t always make profit maximizing decisions l A party thought to be crazy can lead to a significant advantage © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 78

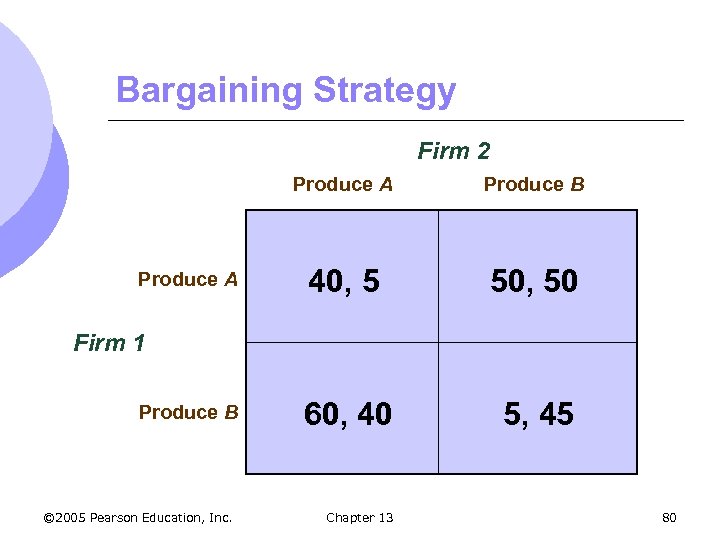

Bargaining Strategy l Bargaining situation can depend on ability to affect relative bargaining position l Consider two firms introducing one of two complementary goods. m Firm 1 has cost advantage in Good A m Firm 2 has cost advantage in Good B © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 79

Bargaining Strategy l Bargaining situation can depend on ability to affect relative bargaining position l Consider two firms introducing one of two complementary goods. m Firm 1 has cost advantage in Good A m Firm 2 has cost advantage in Good B © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 79

Bargaining Strategy Firm 2 Produce A Produce B 40, 5 50, 50 60, 40 5, 45 Firm 1 Produce B © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 80

Bargaining Strategy Firm 2 Produce A Produce B 40, 5 50, 50 60, 40 5, 45 Firm 1 Produce B © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 80

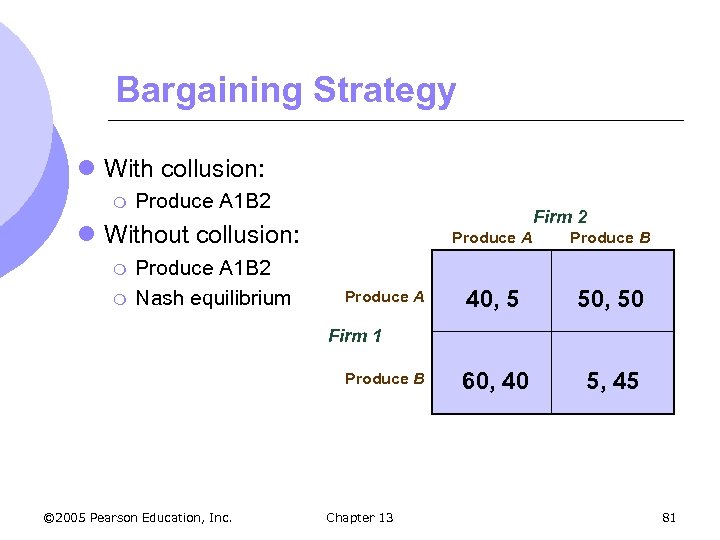

Bargaining Strategy l With collusion: m Produce A 1 B 2 Firm 2 l Without collusion: m m Produce A 1 B 2 Nash equilibrium Produce A Produce B 40, 5 50, 50 60, 40 5, 45 Firm 1 Produce B © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 81

Bargaining Strategy l With collusion: m Produce A 1 B 2 Firm 2 l Without collusion: m m Produce A 1 B 2 Nash equilibrium Produce A Produce B 40, 5 50, 50 60, 40 5, 45 Firm 1 Produce B © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 81

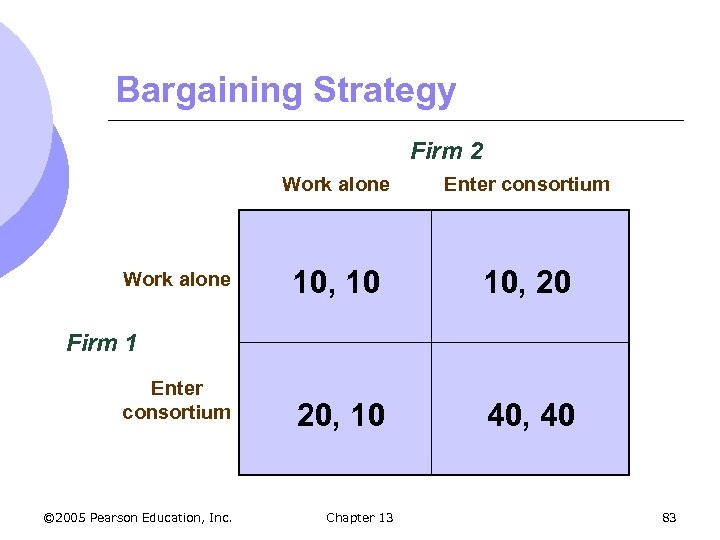

Bargaining Strategy l Suppose each firm is also bargaining on the decision to join in a research consortium with a third firm. l Dominant strategy is for both firms to enter consortium © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 82

Bargaining Strategy l Suppose each firm is also bargaining on the decision to join in a research consortium with a third firm. l Dominant strategy is for both firms to enter consortium © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 82

Bargaining Strategy Firm 2 Work alone Enter consortium 10, 10 10, 20 20, 10 40, 40 Firm 1 Enter consortium © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 83

Bargaining Strategy Firm 2 Work alone Enter consortium 10, 10 10, 20 20, 10 40, 40 Firm 1 Enter consortium © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 83

Bargaining Strategy l Linking the Bargain Problem m Firm 1 announces it will join the consortium only if Firm 2 agrees to produce A and Firm 1 will produce B. m Firm 2’s best interest to produce A with firm 1 producing B l Firm © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. 1’s profit increases from 50 to 60 Chapter 13 84

Bargaining Strategy l Linking the Bargain Problem m Firm 1 announces it will join the consortium only if Firm 2 agrees to produce A and Firm 1 will produce B. m Firm 2’s best interest to produce A with firm 1 producing B l Firm © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. 1’s profit increases from 50 to 60 Chapter 13 84

Bargaining Strategy l Strategic moves can be used in bargaining l Combining issues in bargaining can benefit one side at other’s expense © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 85

Bargaining Strategy l Strategic moves can be used in bargaining l Combining issues in bargaining can benefit one side at other’s expense © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 85

Wal-Mart Stores’ Preemptive Investment Strategy l How did Wal-Mart become the largest retailer in the U. S. when many established retail chains were closing their doors? m Gained monopoly power by opening in small town with no threat of other discount competition m Preemptive game with Nash equilibrium © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 86

Wal-Mart Stores’ Preemptive Investment Strategy l How did Wal-Mart become the largest retailer in the U. S. when many established retail chains were closing their doors? m Gained monopoly power by opening in small town with no threat of other discount competition m Preemptive game with Nash equilibrium © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 86

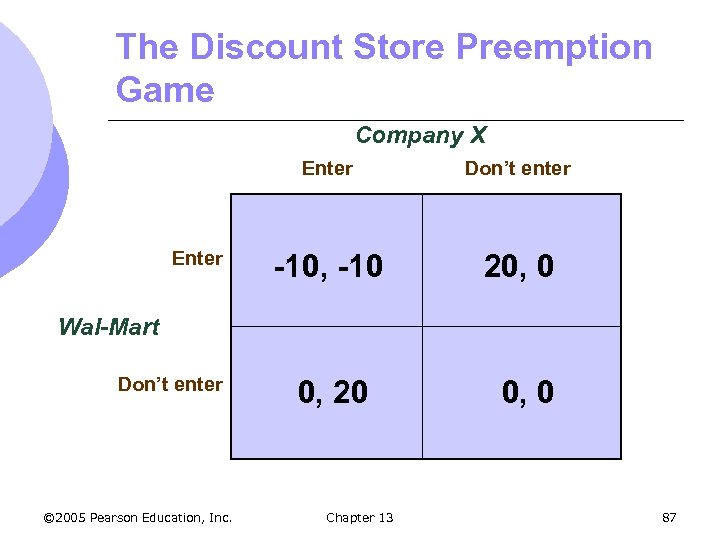

The Discount Store Preemption Game Company X Enter Don’t enter -10, -10 20, 0 0, 20 0, 0 Wal-Mart Don’t enter © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 87

The Discount Store Preemption Game Company X Enter Don’t enter -10, -10 20, 0 0, 20 0, 0 Wal-Mart Don’t enter © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 87

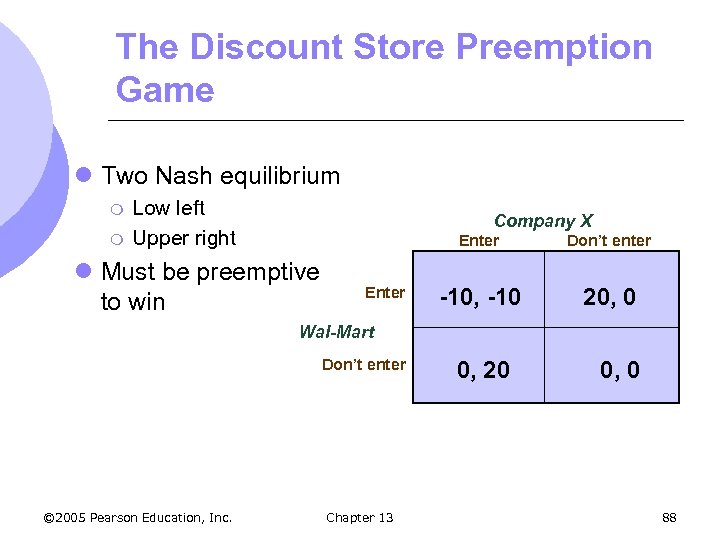

The Discount Store Preemption Game l Two Nash equilibrium m m Low left Upper right Company X Enter l Must be preemptive to win Enter Don’t enter -10, -10 20, 0 Wal-Mart Don’t enter © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 0, 20 0, 0 88

The Discount Store Preemption Game l Two Nash equilibrium m m Low left Upper right Company X Enter l Must be preemptive to win Enter Don’t enter -10, -10 20, 0 Wal-Mart Don’t enter © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 0, 20 0, 0 88

Entry Deterrence l Barriers to entry important for monopoly power m Economies of scale, patents and licenses, access to critical inputs m Firms can also deter entry l To deter entry, the incumbent firm must convince any potential competitor that entry will be unprofitable. © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 89

Entry Deterrence l Barriers to entry important for monopoly power m Economies of scale, patents and licenses, access to critical inputs m Firms can also deter entry l To deter entry, the incumbent firm must convince any potential competitor that entry will be unprofitable. © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 89

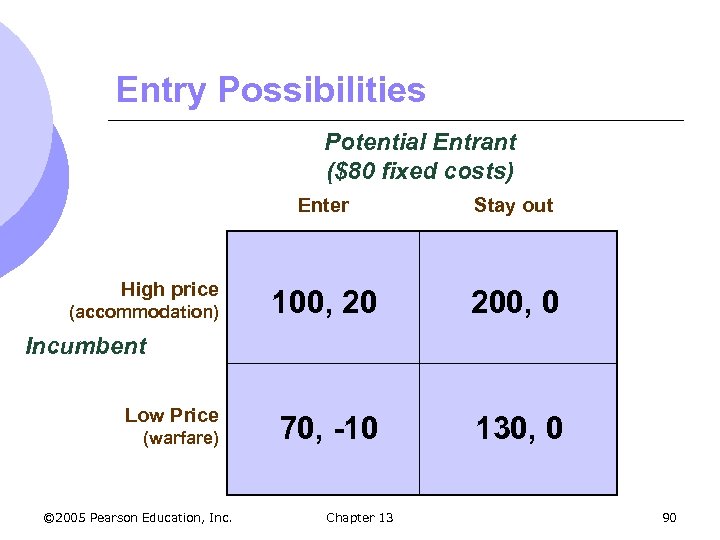

Entry Possibilities Potential Entrant ($80 fixed costs) Enter High price (accommodation) Stay out 100, 20 200, 0 70, -10 130, 0 Incumbent Low Price (warfare) © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 90

Entry Possibilities Potential Entrant ($80 fixed costs) Enter High price (accommodation) Stay out 100, 20 200, 0 70, -10 130, 0 Incumbent Low Price (warfare) © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 90

Entry Deterrence l Scenario m If X does not enter I makes a profit of $200 million. m If X enters and charges a high price I earns a profit of $100 million and X earns $20 million. m If X enters and charges a low price I earns a profit of $70 million and X earns $-10 million. © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 91

Entry Deterrence l Scenario m If X does not enter I makes a profit of $200 million. m If X enters and charges a high price I earns a profit of $100 million and X earns $20 million. m If X enters and charges a low price I earns a profit of $70 million and X earns $-10 million. © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 91

Entry Deterrence l Could threaten X with warfare if enter market m Not credible because once X has entered, it is in your best interest to accommodate and maintain high price. © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 92

Entry Deterrence l Could threaten X with warfare if enter market m Not credible because once X has entered, it is in your best interest to accommodate and maintain high price. © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 92

Entry Deterrence l What if make an investment before entry to increase my capacity m Irrevocable commitment l Gives new payoff matrix since profits will be reduced by investment l Threat is completely credible l Rational for firm X to stay out of market © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 93

Entry Deterrence l What if make an investment before entry to increase my capacity m Irrevocable commitment l Gives new payoff matrix since profits will be reduced by investment l Threat is completely credible l Rational for firm X to stay out of market © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 93

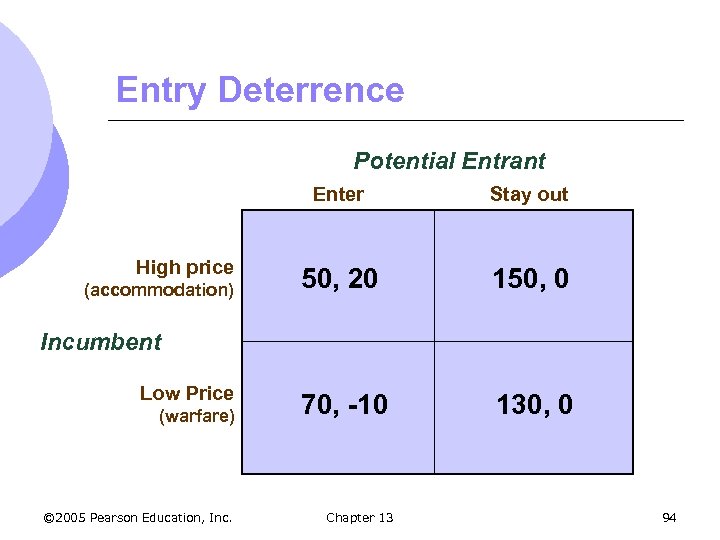

Entry Deterrence Potential Entrant Enter High price (accommodation) Stay out 50, 20 150, 0 70, -10 130, 0 Incumbent Low Price (warfare) © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 94

Entry Deterrence Potential Entrant Enter High price (accommodation) Stay out 50, 20 150, 0 70, -10 130, 0 Incumbent Low Price (warfare) © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 94

Entry Deterrence l If incumbent has reputation of price cutting competitors even at loss, then threat will be credible. l Short run losses may be offset by long run gains as monopolist © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 95

Entry Deterrence l If incumbent has reputation of price cutting competitors even at loss, then threat will be credible. l Short run losses may be offset by long run gains as monopolist © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 95

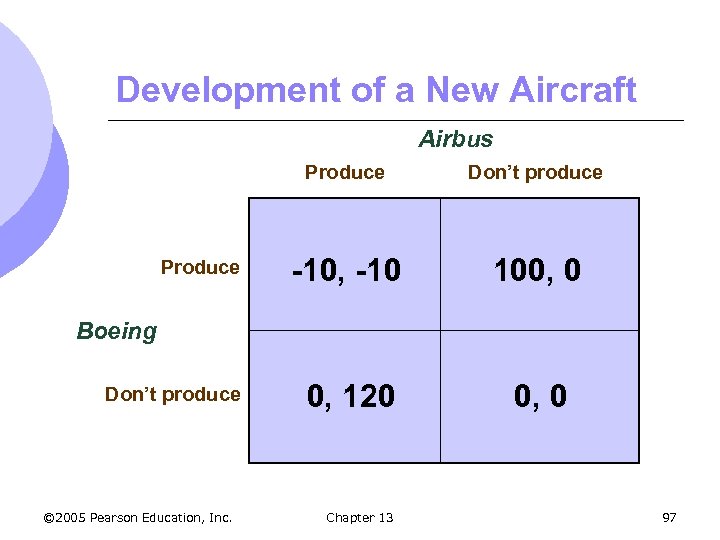

Entry Deterrence l Production of commercial airlines exhibit significant economies of scale l Airbus and Boeing considering new aircraft l Suppose not economical for both firms to produce the new aircraft © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 96

Entry Deterrence l Production of commercial airlines exhibit significant economies of scale l Airbus and Boeing considering new aircraft l Suppose not economical for both firms to produce the new aircraft © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 96

Development of a New Aircraft Airbus Produce Don’t produce Produce -10, -10 100, 0 Don’t produce 0, 120 0, 0 Boeing © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 97

Development of a New Aircraft Airbus Produce Don’t produce Produce -10, -10 100, 0 Don’t produce 0, 120 0, 0 Boeing © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 97

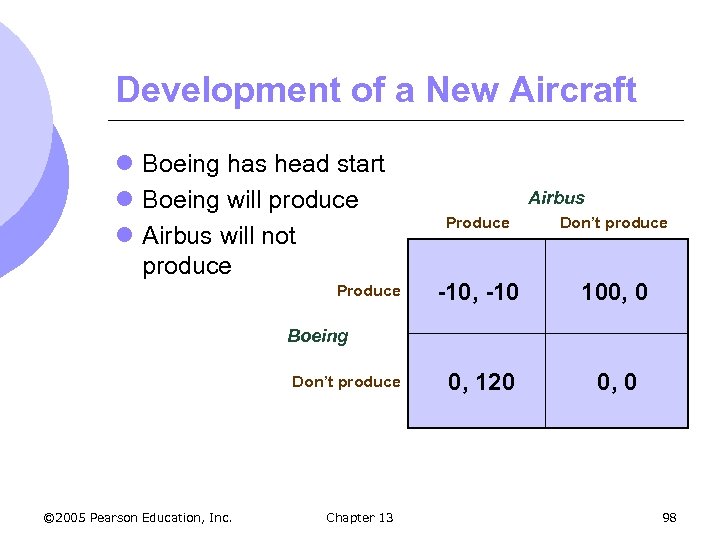

Development of a New Aircraft l Boeing has head start l Boeing will produce l Airbus will not produce Produce Airbus Produce Don’t produce -10, -10 100, 0 0, 120 0, 0 Boeing Don’t produce © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 98

Development of a New Aircraft l Boeing has head start l Boeing will produce l Airbus will not produce Produce Airbus Produce Don’t produce -10, -10 100, 0 0, 120 0, 0 Boeing Don’t produce © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 98

Development of a New Aircraft l Governments can change outcome of game l European government agrees to subsidize Airbus before Boeing decides to produce l With Airbus being subsidized, the payoff matrix for the two firms would differ significantly. © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 99

Development of a New Aircraft l Governments can change outcome of game l European government agrees to subsidize Airbus before Boeing decides to produce l With Airbus being subsidized, the payoff matrix for the two firms would differ significantly. © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 99

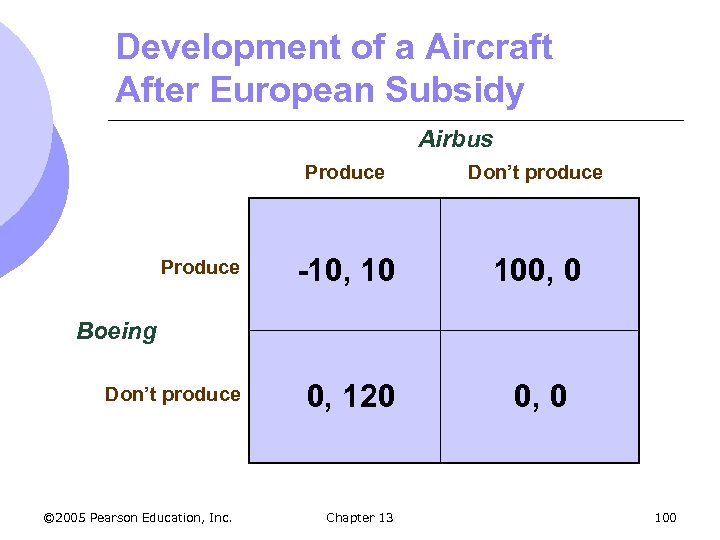

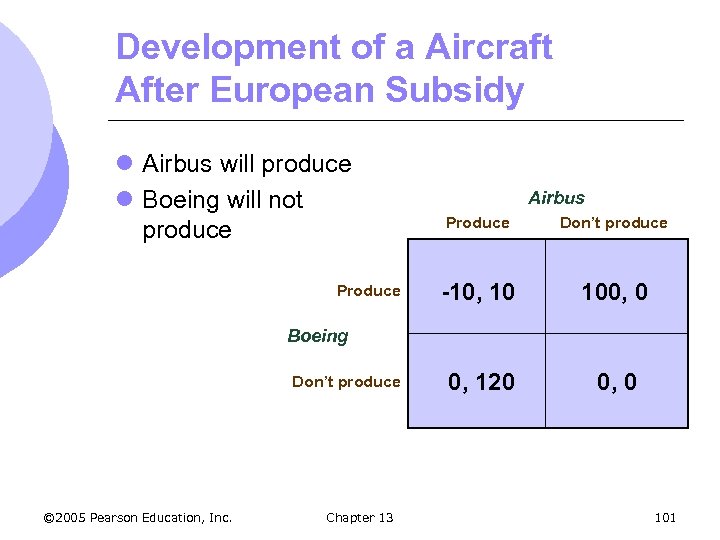

Development of a Aircraft After European Subsidy Airbus Produce Don’t produce Produce -10, 10 100, 0 Don’t produce 0, 120 0, 0 Boeing © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 100

Development of a Aircraft After European Subsidy Airbus Produce Don’t produce Produce -10, 10 100, 0 Don’t produce 0, 120 0, 0 Boeing © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 100

Development of a Aircraft After European Subsidy l Airbus will produce l Boeing will not produce Produce Airbus Produce Don’t produce -10, 10 100, 0 0, 120 0, 0 Boeing Don’t produce © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 101

Development of a Aircraft After European Subsidy l Airbus will produce l Boeing will not produce Produce Airbus Produce Don’t produce -10, 10 100, 0 0, 120 0, 0 Boeing Don’t produce © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 101

Diaper Wars l Even though there are only two major firms, competition is intense. l The competition occurs mostly in the form of cost-reducing innovation. l Small cost savings can lead to capturing of market share l Both firms spend significantly on R&D © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 102

Diaper Wars l Even though there are only two major firms, competition is intense. l The competition occurs mostly in the form of cost-reducing innovation. l Small cost savings can lead to capturing of market share l Both firms spend significantly on R&D © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 102

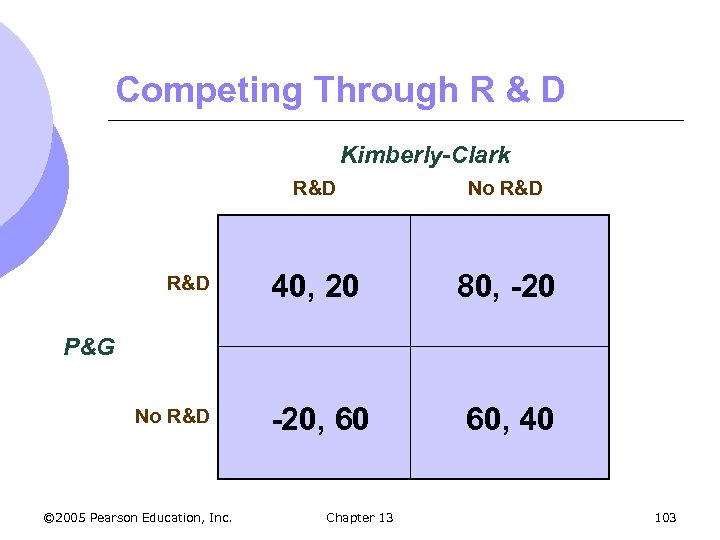

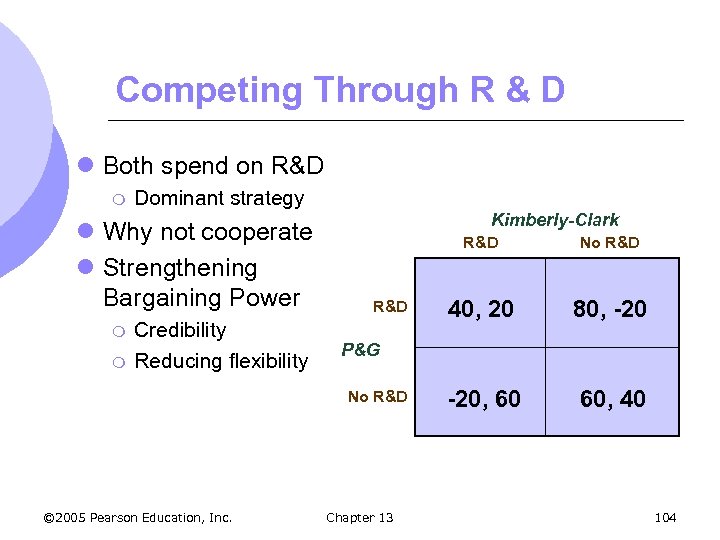

Competing Through R & D Kimberly-Clark R&D No R&D 40, 20 80, -20, 60 60, 40 P&G No R&D © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 103

Competing Through R & D Kimberly-Clark R&D No R&D 40, 20 80, -20, 60 60, 40 P&G No R&D © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 103

Competing Through R & D l Both spend on R&D m Dominant strategy l Why not cooperate l Strengthening Bargaining Power m m Credibility Reducing flexibility Kimberly-Clark R&D 40, 20 80, -20, 60 60, 40 P&G No R&D © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. No R&D Chapter 13 104

Competing Through R & D l Both spend on R&D m Dominant strategy l Why not cooperate l Strengthening Bargaining Power m m Credibility Reducing flexibility Kimberly-Clark R&D 40, 20 80, -20, 60 60, 40 P&G No R&D © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. No R&D Chapter 13 104

Auctions l Markets in which products are bought and sold through formal biding processes m Encourages competition that increases seller’s revenue m Low cost of transactions m Useful for unique items or though with fluctuating value l Tokyo © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. fish market Chapter 13 105

Auctions l Markets in which products are bought and sold through formal biding processes m Encourages competition that increases seller’s revenue m Low cost of transactions m Useful for unique items or though with fluctuating value l Tokyo © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. fish market Chapter 13 105

Auction Formats 1. Traditional English (oral) m m m Seller actively solicits progressively higher bids from a group of potential buyers Buyers always aware of highest bid Stops when no one passes highest bid © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 106

Auction Formats 1. Traditional English (oral) m m m Seller actively solicits progressively higher bids from a group of potential buyers Buyers always aware of highest bid Stops when no one passes highest bid © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 106

Auction Formats 2. Dutch auction m m Seller begins by offering item at relatively high price, then reduces it by fixed amounts until item is sold First buyer accepting offered price can buy item at that price © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 107

Auction Formats 2. Dutch auction m m Seller begins by offering item at relatively high price, then reduces it by fixed amounts until item is sold First buyer accepting offered price can buy item at that price © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 107

Auction Formats 3. Sealed-bid m A. All bids are make simultaneously in sealed envelopes, where winning bid is one who submitted highest bid. First price l B. Sales price equals highest bid Second price l Sales price equals second highest bid © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 108

Auction Formats 3. Sealed-bid m A. All bids are make simultaneously in sealed envelopes, where winning bid is one who submitted highest bid. First price l B. Sales price equals highest bid Second price l Sales price equals second highest bid © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 108

Valuation and Information l How to choose an auction format 1. Private-value auction – bidder knows individual valuations of object, but valuations differ from bidder to bidder l 2. Signed baseball Common-value auction: bidders uncertain what the value is l Offshore oil reserve © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 109

Valuation and Information l How to choose an auction format 1. Private-value auction – bidder knows individual valuations of object, but valuations differ from bidder to bidder l 2. Signed baseball Common-value auction: bidders uncertain what the value is l Offshore oil reserve © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 109

Price-Value Auctions l Each bidder must choose bidding strategy l Payoff for winning is reservation price minus price paid l Payoff for losing is zero © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 110

Price-Value Auctions l Each bidder must choose bidding strategy l Payoff for winning is reservation price minus price paid l Payoff for losing is zero © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 110

Private Value Auction l English oral auction and second – price sealed bid auctions m Bidding truthfully is dominant strategy m Pay based on value of second highest bidder so no incentive not to bid reservation price m Risk to bidding higher than reservation price © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 111

Private Value Auction l English oral auction and second – price sealed bid auctions m Bidding truthfully is dominant strategy m Pay based on value of second highest bidder so no incentive not to bid reservation price m Risk to bidding higher than reservation price © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 111

Private Value Auctions l English auction m Continue bidding until second person is unwilling to make bid l Sealed-bid auction m Winning bid approximately equal to the second highest bidder’s reservation price l Both yield the same revenue © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 112

Private Value Auctions l English auction m Continue bidding until second person is unwilling to make bid l Sealed-bid auction m Winning bid approximately equal to the second highest bidder’s reservation price l Both yield the same revenue © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 112

Common Value Auctions l Winner’s Curse m The winner is worse off because they over estimated the value of the item and thereby overbid m Must reduce bid by amount equal to the expected error of the winning bidder m If lot of variation in other bidders than estimates are fairly imprecise © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 113

Common Value Auctions l Winner’s Curse m The winner is worse off because they over estimated the value of the item and thereby overbid m Must reduce bid by amount equal to the expected error of the winning bidder m If lot of variation in other bidders than estimates are fairly imprecise © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 113

Maximizing Auction Revenue 1. Private Value auction m Encourage many bidders to increase expected bid of winner 2. Common Value Auction m Use open rather than sealed bid l m Generate greater revenue Reveal information about true value reducing concern of winner’s curse © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 114

Maximizing Auction Revenue 1. Private Value auction m Encourage many bidders to increase expected bid of winner 2. Common Value Auction m Use open rather than sealed bid l m Generate greater revenue Reveal information about true value reducing concern of winner’s curse © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 114

Maximizing Auction Revenue 3. Private value auction m m Set min bid equal to or higher than value to you of keeping good for future sale Protect against loss if bidders unaware of value Increase size of bids by letting bidders think item is valuable No sale could make bidders think item is low quality © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 115

Maximizing Auction Revenue 3. Private value auction m m Set min bid equal to or higher than value to you of keeping good for future sale Protect against loss if bidders unaware of value Increase size of bids by letting bidders think item is valuable No sale could make bidders think item is low quality © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 115

Bidding and Collusion l Buyers can allow benefit from collusion m Can be done legally through buying groups m Can be done illegally through collusive agreements that violate antitrust laws m Collusion not easy because large incentive to cheat m Repeated auctions allow for penalizing participants that break agreement © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 116

Bidding and Collusion l Buyers can allow benefit from collusion m Can be done legally through buying groups m Can be done illegally through collusive agreements that violate antitrust laws m Collusion not easy because large incentive to cheat m Repeated auctions allow for penalizing participants that break agreement © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 116

Bidding and Collusion l Examples 1. Collusion among baseball owners to limit their bidding for free-agent players in 1980’s 2. Two of world’s most successful auction houses were found guilty of agreeing to fix prices of commissions m Sotheby’s and Christie’s © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 117

Bidding and Collusion l Examples 1. Collusion among baseball owners to limit their bidding for free-agent players in 1980’s 2. Two of world’s most successful auction houses were found guilty of agreeing to fix prices of commissions m Sotheby’s and Christie’s © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 117

Internet Auctions l Popularity of auctions has skyrocketed with growth of internet l Most popular site is ebay m Dominates online person-person auction industry l Subject to large network externalities m Choose auction site with largest number of potential bidders © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 118

Internet Auctions l Popularity of auctions has skyrocketed with growth of internet l Most popular site is ebay m Dominates online person-person auction industry l Subject to large network externalities m Choose auction site with largest number of potential bidders © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 118

Internet Auctions l Ebay auctions somewhat different from types discussed l A Few Caveats m No quality control function m Poor seller feedback m Bid manipulation may occur © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 119

Internet Auctions l Ebay auctions somewhat different from types discussed l A Few Caveats m No quality control function m Poor seller feedback m Bid manipulation may occur © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. Chapter 13 119