2e2870b0488d96bc248e513b7afb86e0.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 77

Chapter 11: Hedging and Insuring Objective Explain market mechanisms for implementing hedges and insurance 1 Copyright © Prentice Hall Inc. 1999. Author: Nick Bagley

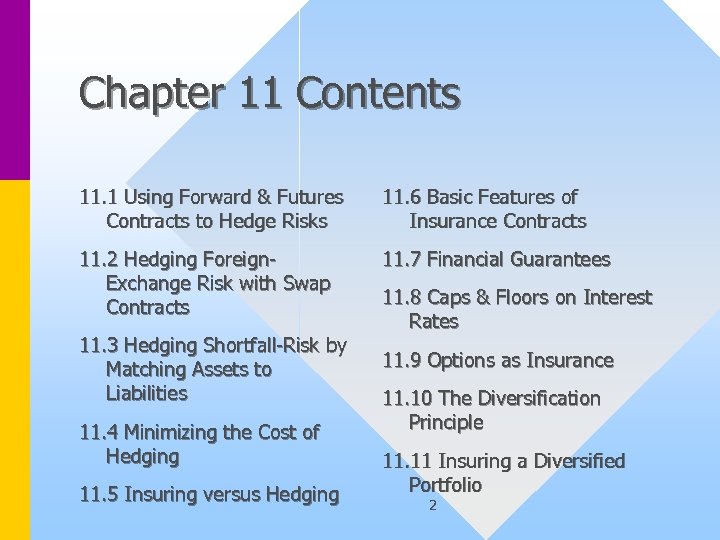

Chapter 11 Contents 11. 1 Using Forward & Futures Contracts to Hedge Risks 11. 6 Basic Features of Insurance Contracts 11. 2 Hedging Foreign. Exchange Risk with Swap Contracts 11. 7 Financial Guarantees 11. 3 Hedging Shortfall-Risk by Matching Assets to Liabilities 11. 4 Minimizing the Cost of Hedging 11. 5 Insuring versus Hedging 11. 8 Caps & Floors on Interest Rates 11. 9 Options as Insurance 11. 10 The Diversification Principle 11. 11 Insuring a Diversified Portfolio 2

11. 1 Using Forward and Futures Contracts to Hedge Risks • Forward Contract – an agreement between two parties to exchange something at a specified price and time • This is an obligation on both parties • Distinguish this from a right, but not the obligation, of a party to exchange something • To nullify the contract, you try to negotiate second contract for a +/- cash consideration 3

Definitions of Terms • Forward Price – Price (agreed to today) of an item to be purchased, and paid for, at a given future date • Spot Price – Price (agreed to today) of an item to be purchased (and paid for) immediately • Face Value – ‘Quantity of deliverable’ times ‘forward price’ 4

Definitions of Terms • Long Position – The agreement to buy the item (from the person taking the short position) • Short Position – The agreement to sell the item (to the person taking the long position) 5

Using Forward and Futures Contracts to Hedge Risks • Traditionally, no payment is made on a forward contract until the settlement date – If the parties to a forward contract do not trust the other, then add clauses to • provide a sureties to a stakeholder • periodically render contract valueless by making cash settlement equal to its current market value 6

Using Forward and Futures Contracts to Hedge Risks: Futures Contracts • Futures contracts for commodities and financial products includes such clauses to protect against unknown credit risks, and we leave the details of this to Chapter 14 • For clarity, the following example treats futures as if they were pure forward contracts 7

The Farmer and the Baker (Example) • Jamela is a farmer with a wheat crop of about 100, 000 bushels, 1 -month from harvest • Mohammed is a baker who will need to restock his inventory of wheat for the coming year 8

The Farmer and the Baker • Jamela and Mohammed wish to reduce price uncertainty because: – Jamela has a mortgage to pay on her farm, and is concerned about wheat prices falling in the next month – Mohammed wishes to close an agreement with a supermarket to supply bread at a fixed price for the coming year 9

The Farmer and the Baker • Jamela and Mohammed agree to a forward contract – Jamela agrees to deliver 100, 000 bushels of wheat at $2. 00 a bushel in one month, and Mohammed agrees to pay the $200, 000 on delivery – Assuming the crop doesn't fail, both parties have hedged their obligations 10

The Farmer and the Baker • Assume that Jamela and Mohammed live miles apart, and don’t know each other • Jamela writes a forward contract with Ms. Distributor at $1. 99/bushel • Mohammed writes a forward contracts with Mr. Supplier at $2. 01/bushel • Ms. Distributor, Mr. Supplier, and Dr. Another hedge with forward contracts at $2. 00/bushel 11

The Farmer and the Baker • Move forward a month – Wheat prices are not $2. 00 a bushel, but $2. 20, due to wet conditions in other geographic regions 12

The Farmer and the Baker – Jamela’s crop is 110, 000 bushels, and it also exceeds the contracted quality – She delivers the contracted 100, 000 b for the agreed $2. 00/bushel, and receives $200, 000 – She sells her surplus 10, 000 b at $2. 20 + $0. 10 (a quality premium) to a local baker, and receives $23, 000 – The total = $223, 000 13

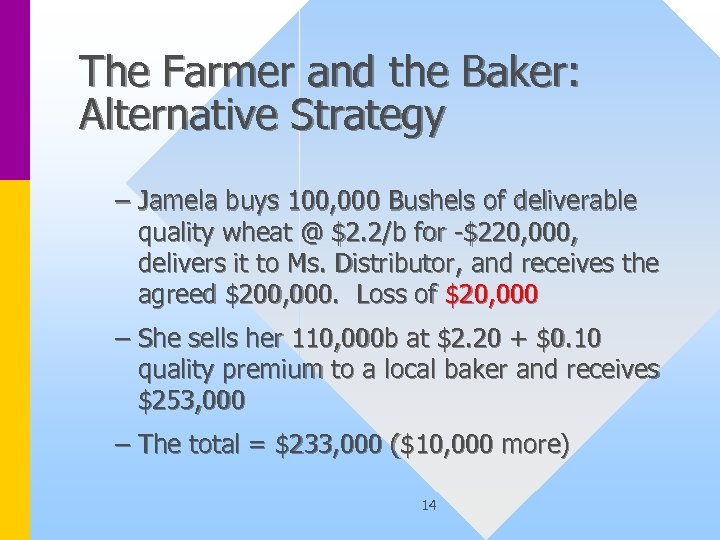

The Farmer and the Baker: Alternative Strategy – Jamela buys 100, 000 Bushels of deliverable quality wheat @ $2. 2/b for -$220, 000, delivers it to Ms. Distributor, and receives the agreed $200, 000. Loss of $20, 000 – She sells her 110, 000 b at $2. 20 + $0. 10 quality premium to a local baker and receives $253, 000 – The total = $233, 000 ($10, 000 more) 14

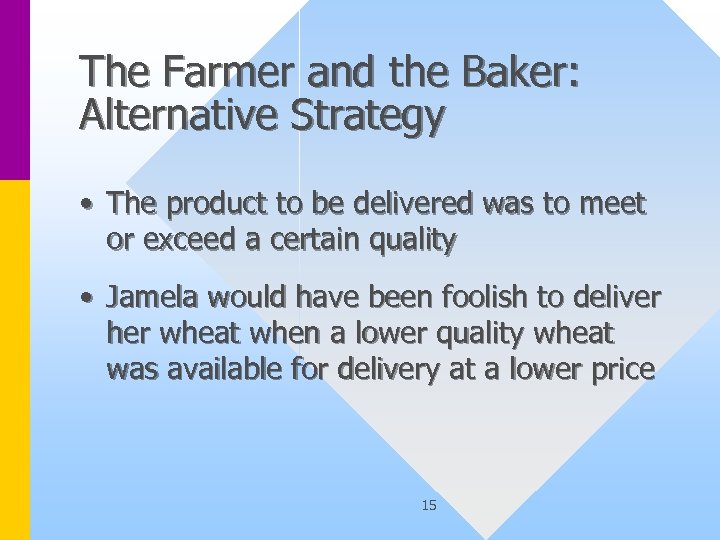

The Farmer and the Baker: Alternative Strategy • The product to be delivered was to meet or exceed a certain quality • Jamela would have been foolish to deliver her wheat when a lower quality wheat was available for delivery at a lower price 15

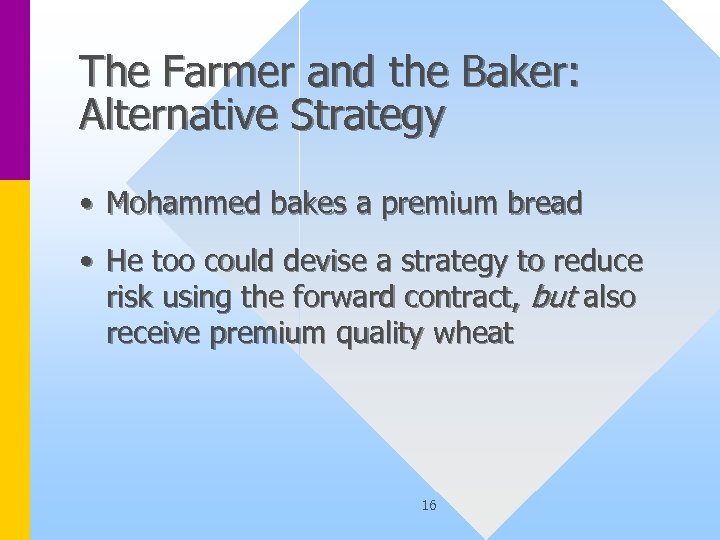

The Farmer and the Baker: Alternative Strategy • Mohammed bakes a premium bread • He too could devise a strategy to reduce risk using the forward contract, but also receive premium quality wheat 16

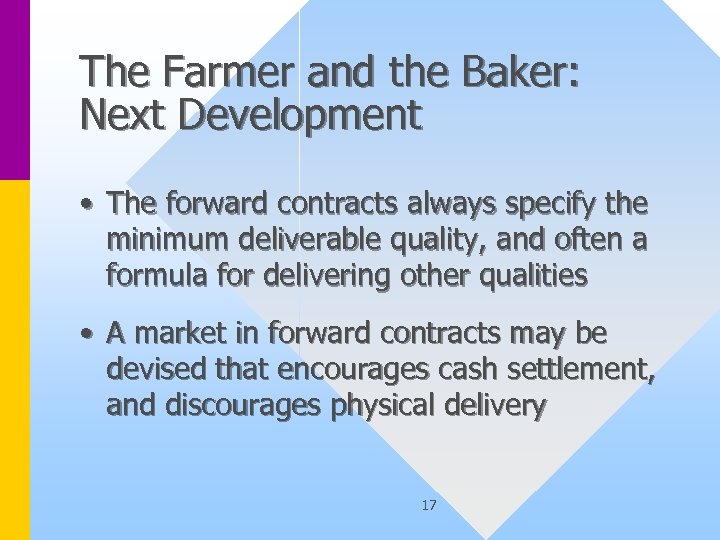

The Farmer and the Baker: Next Development • The forward contracts always specify the minimum deliverable quality, and often a formula for delivering other qualities • A market in forward contracts may be devised that encourages cash settlement, and discourages physical delivery 17

The Farmer and the Baker: Next Development – Jamela sells forward 200, 000 b for 1 -month delivery @ 2. 00 / bushel • This short has no monetary value at this time – A month later, the spot price of deliverable wheat is $2. 20 / b, and the forward is about to expire, and so is also trading at $2. 20 / b – The contract now has a monetary value. The long position is worth $(2. 20 - 2. 00) / bushel • Jamela settles her position by paying $20, 000 18

The Farmer and the Baker: Next Development – Jamela has made a loss of $20, 000 on her trade in the hypothetical wheat forwards market – She recovers this loss when she sells her wheat • This is a true hedge. She has lost the opportunity to participate in a rise in the price of wheat in return for down-side protection 19

The Farmer and the Baker: Next Development – The baker’s hedge in the forward market resulted in a settlement of $20, 000 – When he takes physical delivery, he exactly offsets higher spot prices with this $20, 000 – He traded the opportunity of lower wheat prices for a known price • Both gained! Mohammed’s gain (at Jamela expense) is 20/20 hindsight, and should be irrelevant to both of them 20

The Farmer and the Baker: Next Development • Omar is rich, and wants to get richer – He purchases forward 100, 000 b of wheat @ $2. 00/bushel, for delivery in 1 -month – At maturity, deliverable wheat costs $2. 20/b and he makes a cash settlement, gaining $20, 000 – Omar is a speculator profiting from his purported understanding of the market 21

The Farmer and the Baker: Next Development • Rema wants to get rich too – She sells forward 100, 000 b of wheat @ $2. 00/bushel for delivery in 1 -month – At maturity, deliverable wheat costs $2. 20/b but she is unable pay the $20, 000 she owes – Rema’s default must be made good by one or more of the market’s participants 22

The Farmer and the Baker: Forwards to Futures • To mitigate default-risk exposure – Require a modest surety deposit based on daily volatility – Mark contract to market daily (rendering them temporally valueless) • The small profit/loss is payable immediately – Remaining problem: Large daily price movements 23

The Farmer and the Baker: Conclusion • The farmer and the baker have both eliminated specific risks through perfectly anti-correlated assets • Speculators are exposed to considerable risk, hoping to enjoy a statistical profit – They provide liquidity and expertise that push the market further towards efficiency 24

Risk Transfer: Three Points • Whether the transaction reduces or increases risk depends upon the particular context in which it is undertaken • Both parties to a risk-reducing transaction can benefit. In retrospect, it may seem as if one of the parties has gained at the expense of the other • Even with no change in total output nor total risk, redistributing the way the risk is borne can improve the welfare of the individuals involved 25

11. 2 Hedging Foreign. Exchange Risk with Swap Contracts • Swap Contract – an agreement between two parties to exchange a series of cash flows, at specific intervals, over a specified period of time – the swap payments are based on an agreed principal amount (the notional amount) – there is no immediate payment of money to either party as compensation for entering the contract 26

Hedging Foreign-Exchange Risk with Swap Contracts • A swap may call for the exchange of anything, but most swaps are for the exchange of – commodities – currencies – securities’ returns 27

Currency Swap Example • You have an agreement with a German software distributor for them to market the German language version of your financial derivative pricing program for a payment of DM 100, 000/year for 10 years • To hedge foreign exchange risk, immunize your future DM to $US transactions using a currency swap 28 agreement

Currency Swap Example • This swap arrangement is equivalent to a series of forward foreign exchange contracts • The notional amount in the swap contract corresponds to the face value of the implied forward contracts 29

Currency Swap Example • You are still at risk after the swap – Default: There is a probability that the German company will default on its agreement, either by going bankrupt, or by exercising a performance clause in the contract – Default driven Exchange Risk: Should default occur, you reacquire exchange risk through the residual swap agreement 30

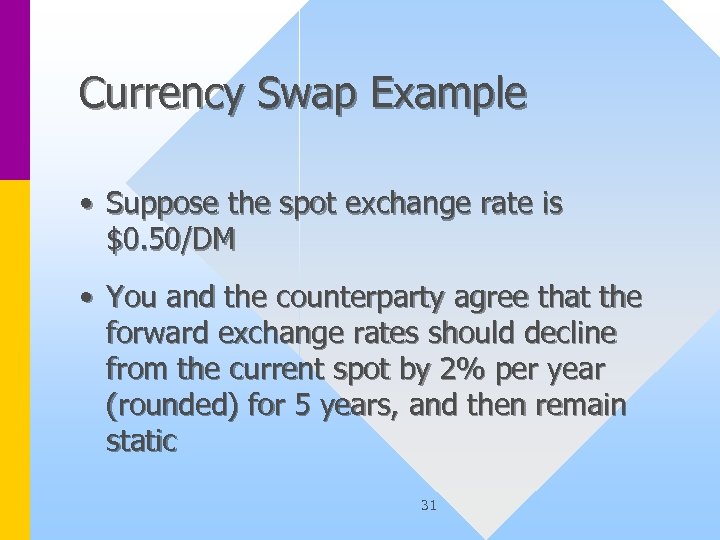

Currency Swap Example • Suppose the spot exchange rate is $0. 50/DM • You and the counterparty agree that the forward exchange rates should decline from the current spot by 2% per year (rounded) for 5 years, and then remain static 31

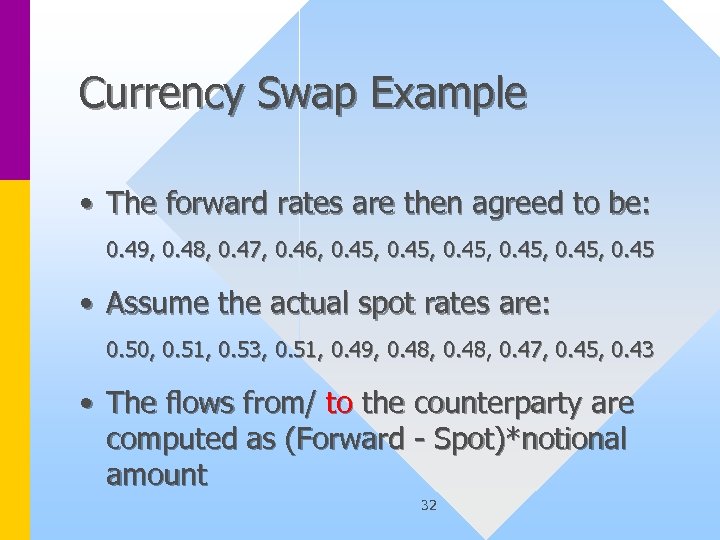

Currency Swap Example • The forward rates are then agreed to be: 0. 49, 0. 48, 0. 47, 0. 46, 0. 45, 0. 45 • Assume the actual spot rates are: 0. 50, 0. 51, 0. 53, 0. 51, 0. 49, 0. 48, 0. 47, 0. 45, 0. 43 • The flows from/ to the counterparty are computed as (Forward - Spot)*notional amount 32

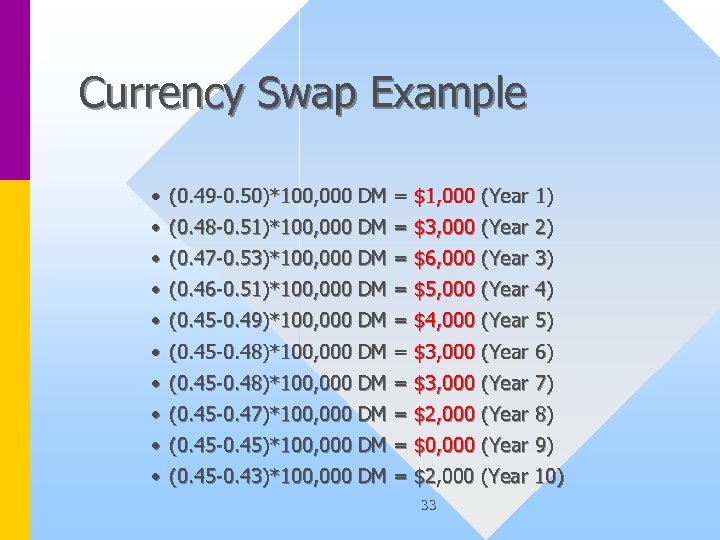

Currency Swap Example • (0. 49 -0. 50)*100, 000 DM = $1, 000 (Year 1) • (0. 48 -0. 51)*100, 000 DM = $3, 000 (Year 2) • (0. 47 -0. 53)*100, 000 DM = $6, 000 (Year 3) • (0. 46 -0. 51)*100, 000 DM = $5, 000 (Year 4) • (0. 45 -0. 49)*100, 000 DM = $4, 000 (Year 5) • (0. 45 -0. 48)*100, 000 DM = $3, 000 (Year 6) • (0. 45 -0. 48)*100, 000 DM = $3, 000 (Year 7) • (0. 45 -0. 47)*100, 000 DM = $2, 000 (Year 8) • (0. 45 -0. 45)*100, 000 DM = $0, 000 (Year 9) • (0. 45 -0. 43)*100, 000 DM = $2, 000 (Year 10) 33

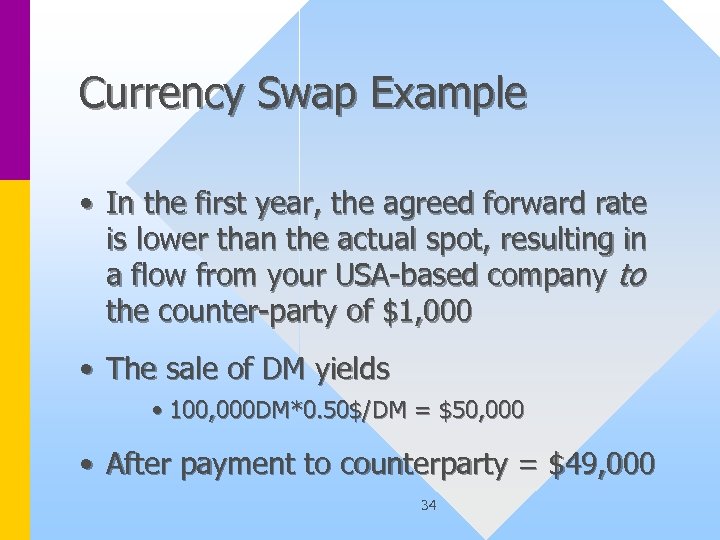

Currency Swap Example • In the first year, the agreed forward rate is lower than the actual spot, resulting in a flow from your USA-based company to the counter-party of $1, 000 • The sale of DM yields • 100, 000 DM*0. 50$/DM = $50, 000 • After payment to counterparty = $49, 000 34

Currency Swap Example • Whatever the spot rate in year 1, the agreement absorbs the variance, and you receive a net $49, 000 (guaranteed) • Assuming no default, the guaranteed net cash flows ($ ’ 000) are • Year 1 = 49, year 2 = 48, year 3 = 47, year 4 = 46, year 5 through year 10 = 45 35

Currency Swap Example – If you prefer a dollar annuity, negotiate: • a fixed forward rate with the counterparty Assume a single forward rate (rather than a schedule based on market expectations formed from the $ & DM yield curves). With the passage of time, the expected market value of the swap will diverge more from zero. This generates higher credit risk for the counterparty, which translates into higher costs for you a new DM payment schedule that, when coupled with the swap, generates a constant $ payment schedule 36

11. 3 Hedging Shortfall-Risk by Matching Assets to Liabilities • Assume a credit union borrows using 1 year CDs, and lends using 30 -year mortgages – If interest rates rise • the market value of the mortgages will fall • mortgage cash flows won’t fully pay the CDs – Result? Insolvency and ruin! 37

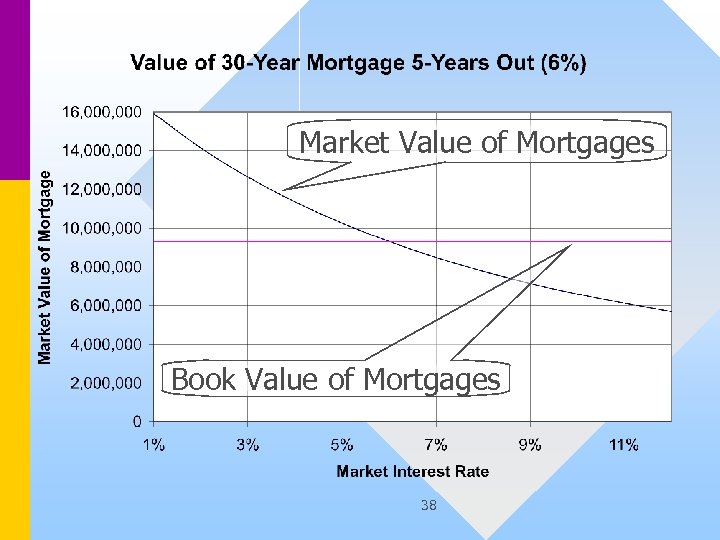

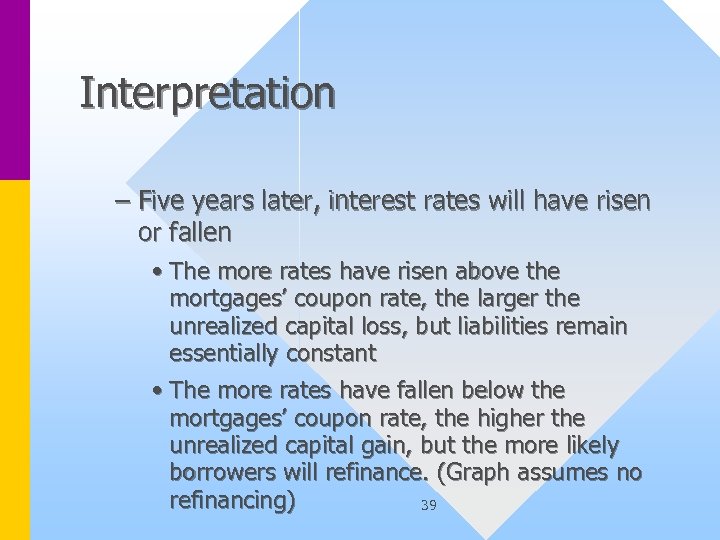

Market Value of Mortgages Book Value of Mortgages 38

Interpretation – Five years later, interest rates will have risen or fallen • The more rates have risen above the mortgages’ coupon rate, the larger the unrealized capital loss, but liabilities remain essentially constant • The more rates have fallen below the mortgages’ coupon rate, the higher the unrealized capital gain, but the more likely borrowers will refinance. (Graph assumes no refinancing) 39

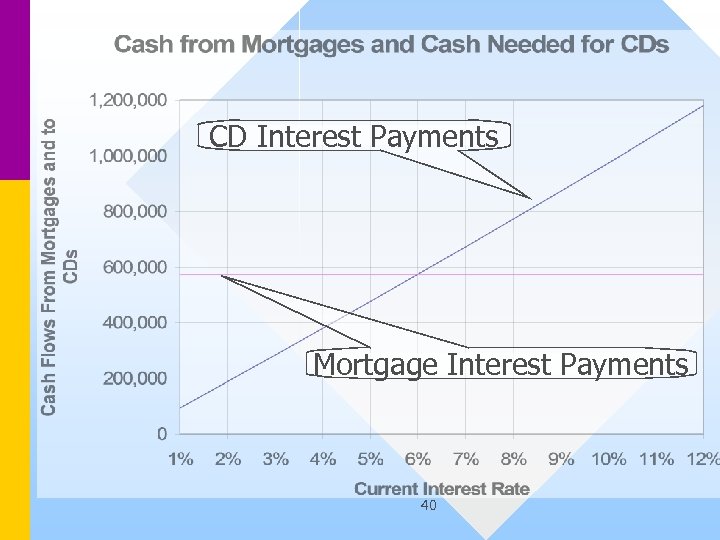

CD Interest Payments Mortgage Interest Payments 40

Interpretation • As interest rates rise, so too does the rate demanded by the lenders • The mortgage borrowers continue to provide the same cash flow • The result is a reduction in the cash flows that service the CDs 41

Remedial Action to Prevent further Damage – Match exposure of assets and liabilities • Sell mortgages & invest in short-term lending – Participate in GNMA, FNMA, … programs • Get lenders to invest in longer-term notes • Lend using adjustable rate mortgages • Issue longer-term bonds – Hedge using interest-rate forwards, futures, options, or swaps 42

11. 4 Minimizing the Cost of Hedging • There are sometimes several ways to hedge a transaction – Choose the one that minimizes the cost of achieving the desired level of risk reduction after considering transaction costs, and taxes 43

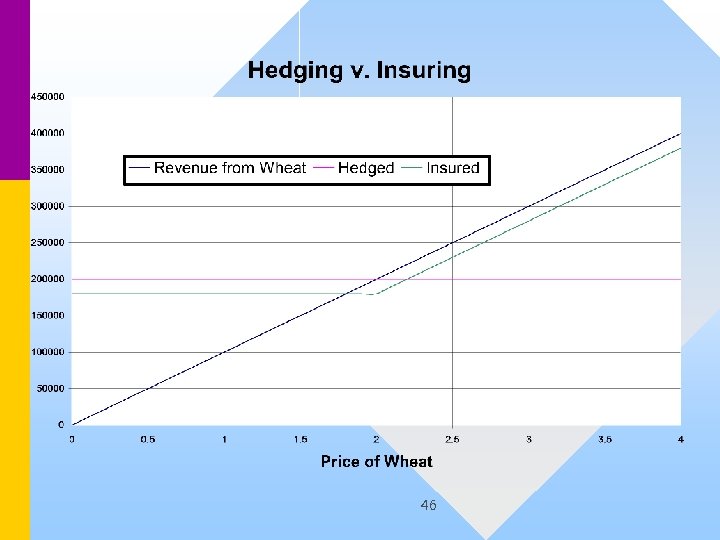

11. 5 Hedging versus Insuring – Hedging: A contract “to purchase 100, 000 perfume bottles, six months from now @ $0. 25/bottle, payment on receipt” is a forward contract (obligation to purchase) – Insuring: A contract “to purchase up to 100, 000 perfume bottles, six months from now @ $0. 25/bottle, payment on receipt” is a not a forward contract (right but no obligation to purchase) 44

Hedging versus Insuring • Recall – Hedging is symmetric, you sacrifice the upside risk to protect you against the downside risk – Insuring is asymmetric, you maintain the upside risk, but dispose of the downside risk 45

46

11. 6 Basic Features of Insurance Contracts • Exclusions • Caps • Deductibles • Co-payments 47

11. 7 Financial Guarantees • Financial guarantees are insurance against credit risk--the risk to you that the counterparty will default • A loan guarantee is a contract that obliges the guarantor to make the promised payment on a loan if the borrower fails to do so 48

11. 8 Caps and Floors on Interest Rates • Some financial instruments, such as ARMs, offer an interest rate that varies with a specified prime rate, the T-bill rate, LIBOR, et cetera • A clause may provide for annual floors, annual caps, global floors, or global caps on interest rate changes 49

11. 9 Options as Insurance • A call (put) option is the right, but not the obligation, to purchase (sell) a given asset according to a schedule of prices and times • European options have a single strike or exercise price, and a single exercise date • American options have a single strike or exercise price, and may be exercised at any time before their expiration or maturity date 50

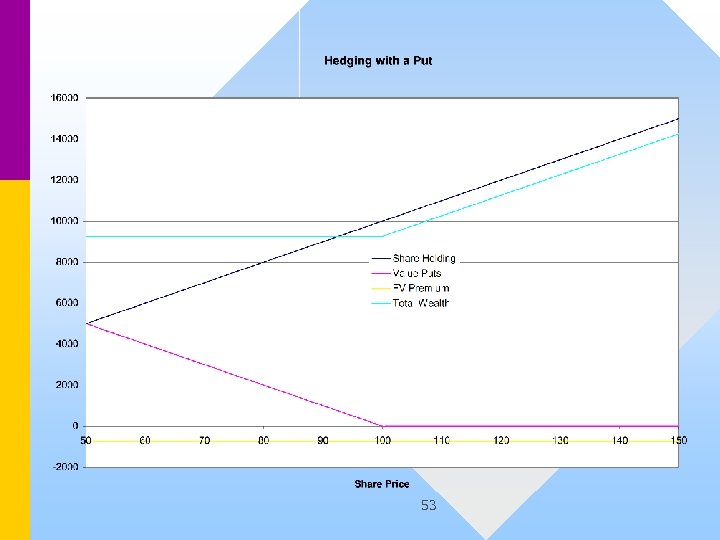

Options as Insurance: Put Illustration • You have 100 shares of XYZ stock currently trading at $100/share, and a planning time horizon of 3 -months • You wish to pay a small premium to insure the current price in 3 -months • You wish to benefit from any stock price rises 51

Options as Insurance: Put Illustration • Strategy: – Retain your holding of 100 shares in XYZ currently valued at $10, 000 – Purchase one round lot of 100 XYZ European put options with a strike price of $100 for a premium of $729. 51 – At the end of 3 -months, your holding, as a function of XYZ new share price, is: 52

53

Put Option on a Bond • The value of a bond depends upon – the risk-free rate for bonds of that maturity – the value of the bond’s collateral • Purchasing a put option on the bond gives downside protection, while preserving upside potential 54

11. 10 The Diversification Principle • Diversification: – splitting an investment among many risky assets instead of concentrating it all in only one • Diversification Principle: – by diversifying across risky assets people can sometimes achieve a reduction in their overall risk exposure with no reduction in their return 55

Diversification of Uncorrected Risks • Assume that you are offered a number of investment opportunities in various biotechnology firms – The outcome of any of the investments has no effect on any of the others (independent) – You believe that each firm has a 50% chance of quadrupling your investment, and a 50% chance of total loss 56

Invest $100, 000 in any one of the firms: – If the firm fails (p = 0. 50) • the expected contribution to your pay-out is 0. 50 * $0 = $0 – If the firm is successful (p = 0. 50) • the expected contribution to your pay-out is 0. 5 * 4 * $100, 000 = $200, 000 – Expected Pay-off = $0 + $200, 000 = $200, 000 57

Invest $50, 000 in any of the firms, & $50, 000 in another – If both firm fails (p = 0. 25) • the expected contribution to your pay-out is 0. 25 * $0 = $0 – If one firm is successful (p = 0. 50) • the expected contribution to your pay-out is 0. 5 * 4 * $50, 000 = $100, 000 – If both firm are successful (p = 0. 25) • the expected contribution to your pay-out is 0. 25 * 4 * 2 * $50, 000 = $100, 000 – Expected Pay-off = $0 + $100, 000 + 100, 000 = $200, 000 58

Conclusion • Investing in one or in two firms has the same expected return • But. . . 59

But. . . • We have not analyzed risk – We will now compute the standard deviations of both strategies 60

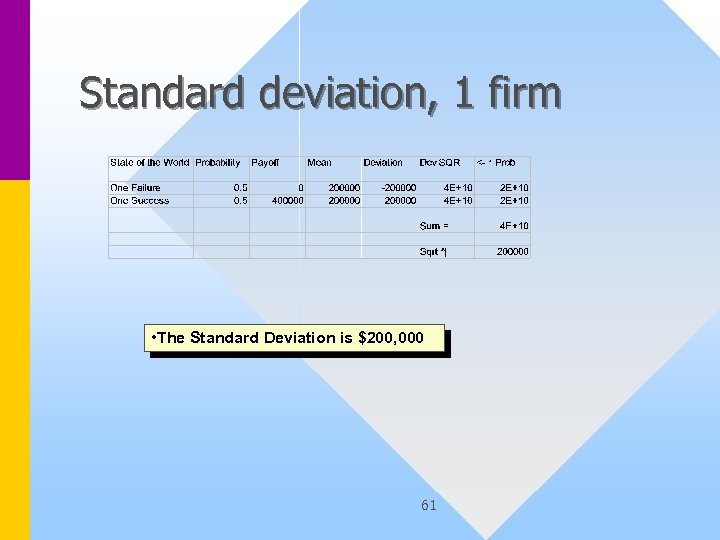

Standard deviation, 1 firm • The Standard Deviation is $200, 000 61

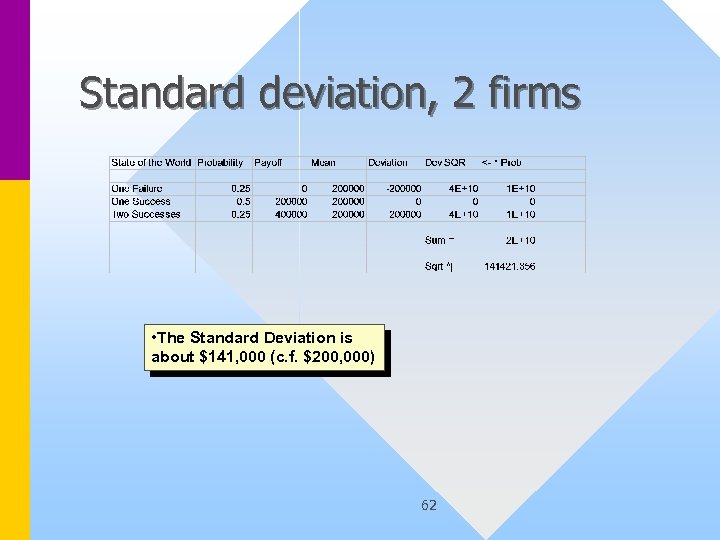

Standard deviation, 2 firms • The Standard Deviation is about $141, 000 (c. f. $200, 000) 62

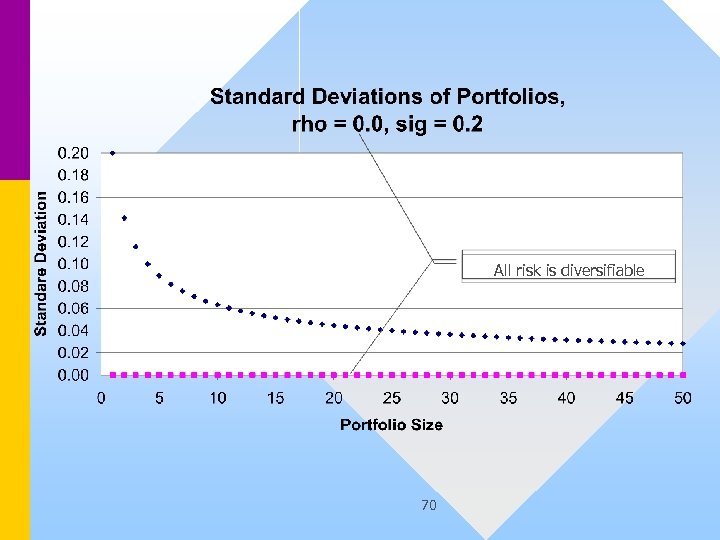

Standard deviation, equal investment in “n” firms • Generalizing the argument, it is easy to prove that the standard deviation in this case is just $200, 000/Sqrare. Root(n) • Conclusion: Given the facts of this example, the risk may be made as close to zero as we wish if there are sufficient securities! In reality, however … n is must be finite, and pharmaceutical projects have a non-zero correlations 63

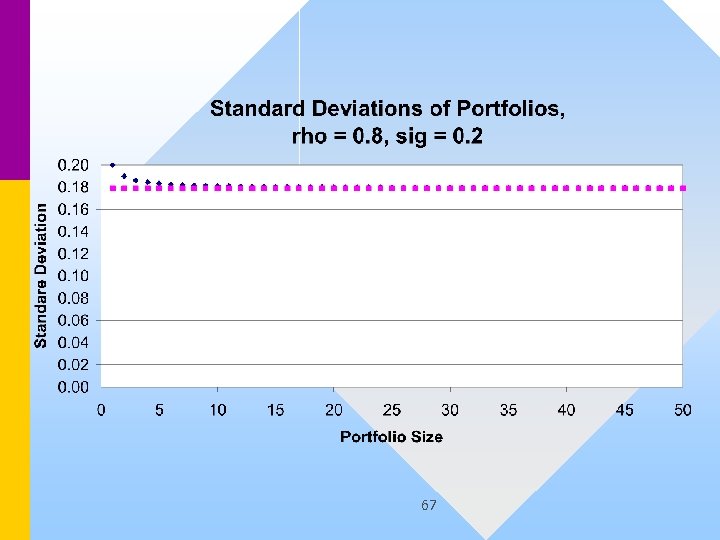

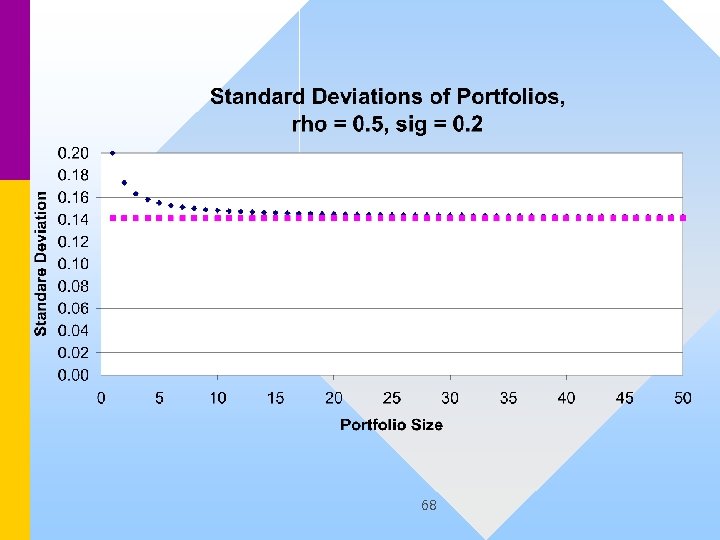

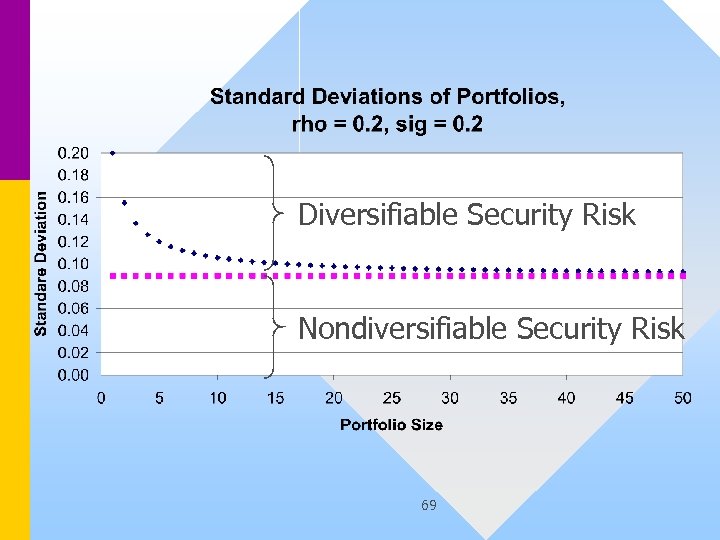

Correlated Homogeneous Securities • Pharmaceutical projects do have positive correlation (Why? ) • Loosen the assumptions made about the correlation, and set it to ρ, and use the generalization of 64

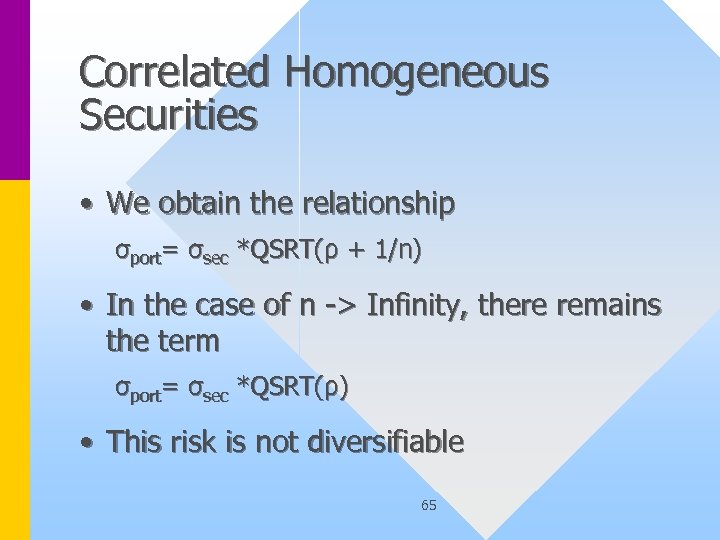

Correlated Homogeneous Securities • We obtain the relationship σport= σsec *QSRT(ρ + 1/n) • In the case of n -> Infinity, there remains the term σport= σsec *QSRT(ρ) • This risk is not diversifiable 65

66

67

68

Diversifiable Security Risk Nondiversifiable Security Risk 69

All risk is diversifiable 70

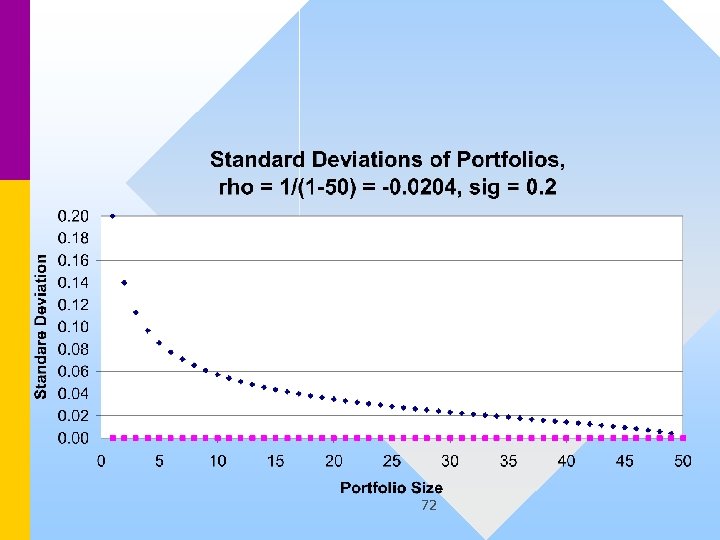

Negative Correlation • Note that as the correlation ranges from one to zero – the percentage of undiversifiable risk falls – the number of securities necessary to approach this level increases • …and just for fun, let’s look at a negative correlation 71

72

Nondiversifiable Risk • The graphs illustrate an important point – For homogeneous securities (at least), there is an asymptotic value for the least risk a portfolio may contain – For correlations that are strictly positive, there appears to be a level of risk that can’t be diversified away 73

Nondiversifiable Risk • For a fund manager, the cost of holding her assets in either (1) a well diversified portfolio, or (2) a single stock, differ by only (quite low) transaction costs • In this world of homogeneous securities, she may reduce risk by diversifying some of the risk away at (almost) no cost 74

Language • The following groups of word are similes – Diversifiable risk, individual risk, securityspecific risk, irrelevant risk – Nondiversifiable risk, market risk, relevant risk 75

11. 11 Diversification & the Cost of Insurance • When you purchase insurance, the premium, p, may be divided into two portions – a, the actuary value of the good-faith risk – b, the sales, administration, profits, and fraud • The ratio a/p not always as high as one would like 76

Self-Insurance • Accordingly, accepting some of the risk yourself may be advisable in some situations – When the correlation between risks is not high – when the number of risks is relatively high – when the risks are of the same magnitude 77

2e2870b0488d96bc248e513b7afb86e0.ppt