12ffc04e0ce0101dd316a19277f1e560.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 59

Chapter 10: XML The world of XML

Chapter 10: XML The world of XML

Context • The dawn of database technology 70 s • A DBMS is a flexible store-recall system for digital information • It provides permanent memory for structured information

Context • The dawn of database technology 70 s • A DBMS is a flexible store-recall system for digital information • It provides permanent memory for structured information

Context • Database Managements technology for administrative settings ‘completed’ in the early 80 s • Search for demanding application areas that could benefit from a database approach – A sound datamodel to structure the information and maintain integrity rules – A high level programming language model to manipulate the data – Separation of concerns between modelling and manipulation, and physical storage and order of execution thanks to query optimizer technology

Context • Database Managements technology for administrative settings ‘completed’ in the early 80 s • Search for demanding application areas that could benefit from a database approach – A sound datamodel to structure the information and maintain integrity rules – A high level programming language model to manipulate the data – Separation of concerns between modelling and manipulation, and physical storage and order of execution thanks to query optimizer technology

Context • Demanding areas of research in DBMS core technology: – Office Information systems, e. g. document modelling and workflow – CAD/CAM, e. g. how to manage the design of an airplane or nucleur power plant – GIS, e. g. managing remote sensing information – WWW, e. g. how to integrate heterogenous sources – Agent-based systems, e. g. reactive systems – Multimedia, e. g. video storage/retrieval – Datamining, e. g. discovery of client profiles – Sensor networks, e. g. small footprint and energy-wise computing

Context • Demanding areas of research in DBMS core technology: – Office Information systems, e. g. document modelling and workflow – CAD/CAM, e. g. how to manage the design of an airplane or nucleur power plant – GIS, e. g. managing remote sensing information – WWW, e. g. how to integrate heterogenous sources – Agent-based systems, e. g. reactive systems – Multimedia, e. g. video storage/retrieval – Datamining, e. g. discovery of client profiles – Sensor networks, e. g. small footprint and energy-wise computing

Context • Demanding areas of research in DBMS core technology: – Office Information systems, Extensible DBMS, blobs – CAD/CAM, Object-oriented DBMS, geometry – GIS, GIS DBMS, geometry and images – Agent-based systems, Active DBMS, triggers – Multimedia, MM DBMS, feature analysis – Datamining, Datawarehouse systems, cube, association rules – Sensor networks, P 2 P databases, ad-hoc networking

Context • Demanding areas of research in DBMS core technology: – Office Information systems, Extensible DBMS, blobs – CAD/CAM, Object-oriented DBMS, geometry – GIS, GIS DBMS, geometry and images – Agent-based systems, Active DBMS, triggers – Multimedia, MM DBMS, feature analysis – Datamining, Datawarehouse systems, cube, association rules – Sensor networks, P 2 P databases, ad-hoc networking

Context • Application interaction with DBMS – Proprietary application programming interface, shielding the hardware distinctions – Use readable interfaces to improve monitoring and development • Example: in Monetdb the interaction is based on ascii text with the first character indicative for the message type ‘>’ prompt, await for next request ‘!’ error occurred, rest is the message ‘[‘ start of a tuple answer – Language embedding to remove the impedance mismatch, i. e. avoid cost of transforming data • Effectively failed in the OO world

Context • Application interaction with DBMS – Proprietary application programming interface, shielding the hardware distinctions – Use readable interfaces to improve monitoring and development • Example: in Monetdb the interaction is based on ascii text with the first character indicative for the message type ‘>’ prompt, await for next request ‘!’ error occurred, rest is the message ‘[‘ start of a tuple answer – Language embedding to remove the impedance mismatch, i. e. avoid cost of transforming data • Effectively failed in the OO world

Context • Learning points database perspective, – Database system should not be concerned with the userinteraction technology, ‘they should be blind and deaf’ – The strong requirements on schema, integrity rules and processing is a harness – Interaction with applications should be self-descriptive as much as possible, because, you can not a priori know a complete schema – Need for semi-structured databases

Context • Learning points database perspective, – Database system should not be concerned with the userinteraction technology, ‘they should be blind and deaf’ – The strong requirements on schema, integrity rules and processing is a harness – Interaction with applications should be self-descriptive as much as possible, because, you can not a priori know a complete schema – Need for semi-structured databases

Semi-structured data • Properties of semistructured databases: – The schema is not given in advance and may be implicit in the data – The schema is relatively large and changes frequently – The schema is descriptive rather than prescriptive, integrity rules may be violated – The data is not strongly typed, the values of attributes may be of different type • Stanford Lore system is the prototypical first attempt to support semi-structured databases

Semi-structured data • Properties of semistructured databases: – The schema is not given in advance and may be implicit in the data – The schema is relatively large and changes frequently – The schema is descriptive rather than prescriptive, integrity rules may be violated – The data is not strongly typed, the values of attributes may be of different type • Stanford Lore system is the prototypical first attempt to support semi-structured databases

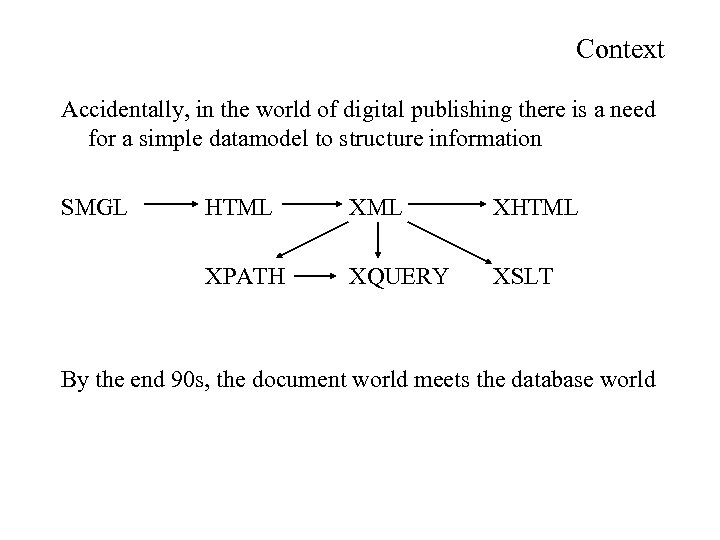

Context Accidentally, in the world of digital publishing there is a need for a simple datamodel to structure information SMGL HTML XHTML XPATH XQUERY XSLT By the end 90 s, the document world meets the database world

Context Accidentally, in the world of digital publishing there is a need for a simple datamodel to structure information SMGL HTML XHTML XPATH XQUERY XSLT By the end 90 s, the document world meets the database world

Introduction • XML: Extensible Markup Language • Defined by the WWW Consortium (W 3 C) • Originally intended as a document markup language not a database language – Documents have tags giving extra information about sections of the document • E. g.

Introduction • XML: Extensible Markup Language • Defined by the WWW Consortium (W 3 C) • Originally intended as a document markup language not a database language – Documents have tags giving extra information about sections of the document • E. g.

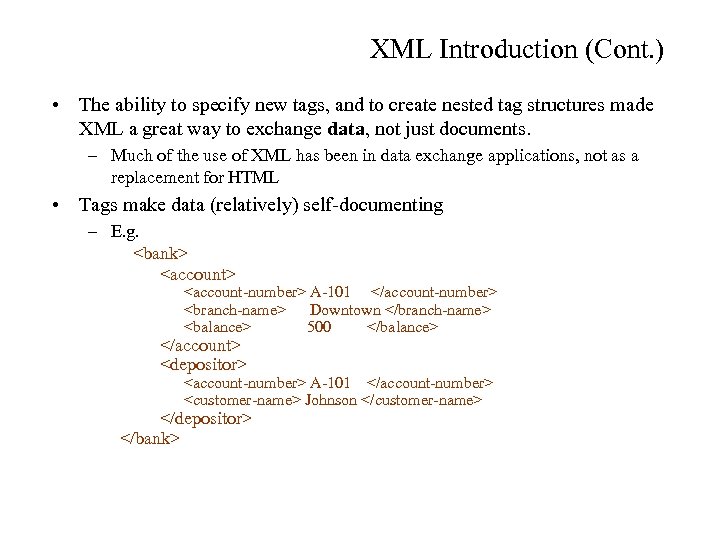

XML Introduction (Cont. ) • The ability to specify new tags, and to create nested tag structures made XML a great way to exchange data, not just documents. – Much of the use of XML has been in data exchange applications, not as a replacement for HTML • Tags make data (relatively) self-documenting – E. g.

XML Introduction (Cont. ) • The ability to specify new tags, and to create nested tag structures made XML a great way to exchange data, not just documents. – Much of the use of XML has been in data exchange applications, not as a replacement for HTML • Tags make data (relatively) self-documenting – E. g.

XML: Motivation • Data interchange is critical in today’s networked world – Examples: • Banking: funds transfer • Order processing (especially inter-company orders) • Scientific data – Chemistry: Chem. ML, … – Genetics: BSML (Bio-Sequence Markup Language), … – Paper flow of information between organizations is being replaced by electronic flow of information • Each application area has its own set of standards for representing information (W 3 C maintains ca 30 standards) • XML has become the basis for all new generation data interchange formats

XML: Motivation • Data interchange is critical in today’s networked world – Examples: • Banking: funds transfer • Order processing (especially inter-company orders) • Scientific data – Chemistry: Chem. ML, … – Genetics: BSML (Bio-Sequence Markup Language), … – Paper flow of information between organizations is being replaced by electronic flow of information • Each application area has its own set of standards for representing information (W 3 C maintains ca 30 standards) • XML has become the basis for all new generation data interchange formats

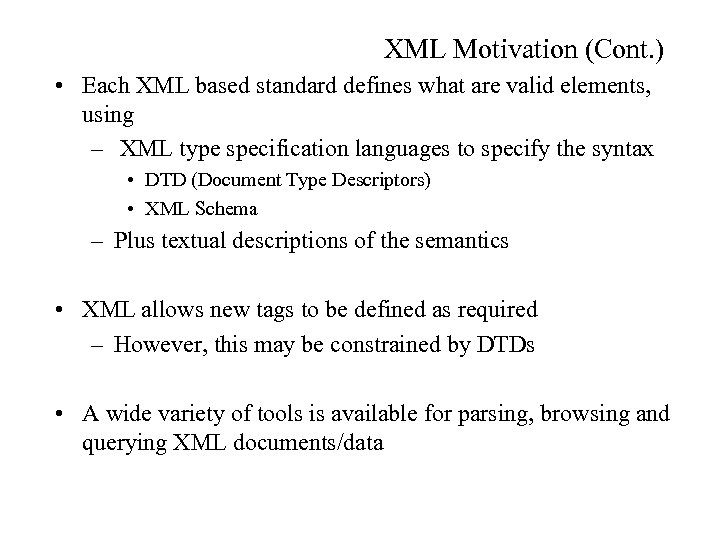

XML Motivation (Cont. ) • Each XML based standard defines what are valid elements, using – XML type specification languages to specify the syntax • DTD (Document Type Descriptors) • XML Schema – Plus textual descriptions of the semantics • XML allows new tags to be defined as required – However, this may be constrained by DTDs • A wide variety of tools is available for parsing, browsing and querying XML documents/data

XML Motivation (Cont. ) • Each XML based standard defines what are valid elements, using – XML type specification languages to specify the syntax • DTD (Document Type Descriptors) • XML Schema – Plus textual descriptions of the semantics • XML allows new tags to be defined as required – However, this may be constrained by DTDs • A wide variety of tools is available for parsing, browsing and querying XML documents/data

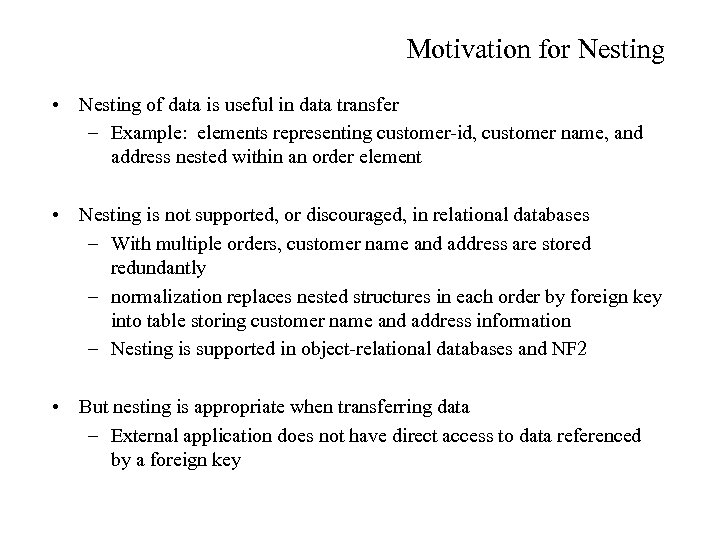

Motivation for Nesting • Nesting of data is useful in data transfer – Example: elements representing customer-id, customer name, and address nested within an order element • Nesting is not supported, or discouraged, in relational databases – With multiple orders, customer name and address are stored redundantly – normalization replaces nested structures in each order by foreign key into table storing customer name and address information – Nesting is supported in object-relational databases and NF 2 • But nesting is appropriate when transferring data – External application does not have direct access to data referenced by a foreign key

Motivation for Nesting • Nesting of data is useful in data transfer – Example: elements representing customer-id, customer name, and address nested within an order element • Nesting is not supported, or discouraged, in relational databases – With multiple orders, customer name and address are stored redundantly – normalization replaces nested structures in each order by foreign key into table storing customer name and address information – Nesting is supported in object-relational databases and NF 2 • But nesting is appropriate when transferring data – External application does not have direct access to data referenced by a foreign key

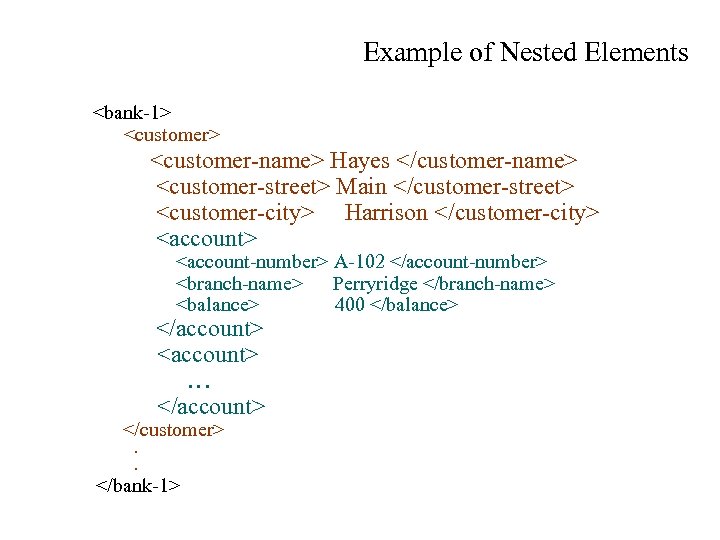

Example of Nested Elements

Example of Nested Elements

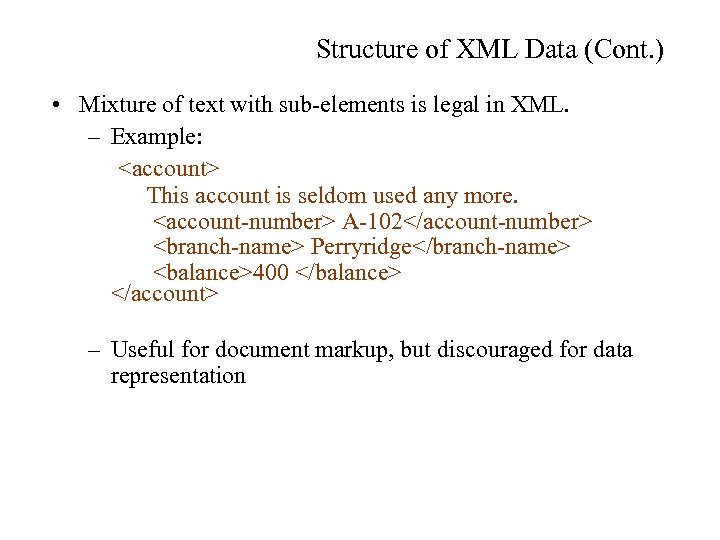

Structure of XML Data (Cont. ) • Mixture of text with sub-elements is legal in XML. – Example:

Structure of XML Data (Cont. ) • Mixture of text with sub-elements is legal in XML. – Example:

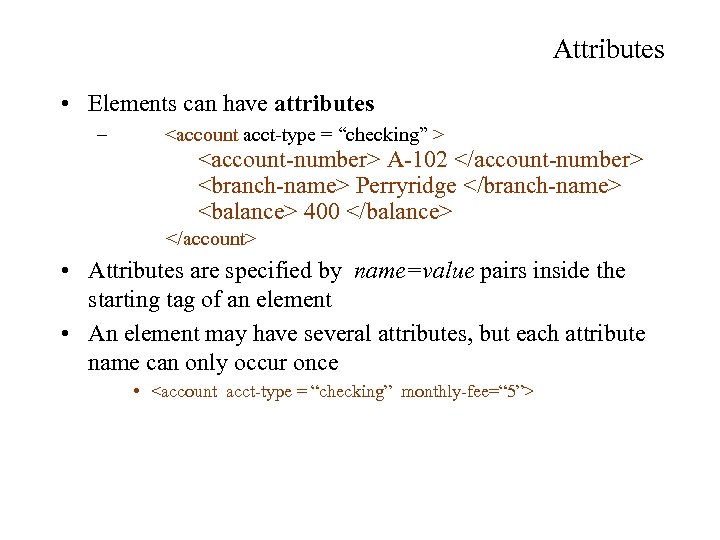

Attributes • Elements can have attributes –

Attributes • Elements can have attributes –

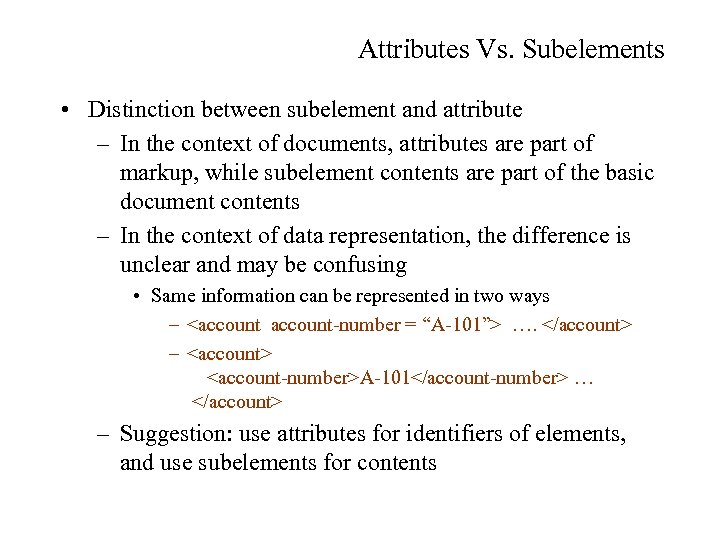

Attributes Vs. Subelements • Distinction between subelement and attribute – In the context of documents, attributes are part of markup, while subelement contents are part of the basic document contents – In the context of data representation, the difference is unclear and may be confusing • Same information can be represented in two ways –

Attributes Vs. Subelements • Distinction between subelement and attribute – In the context of documents, attributes are part of markup, while subelement contents are part of the basic document contents – In the context of data representation, the difference is unclear and may be confusing • Same information can be represented in two ways –

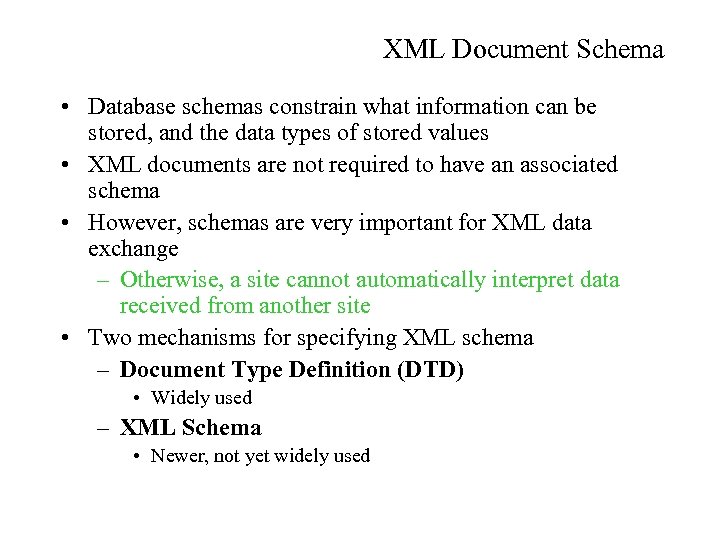

XML Document Schema • Database schemas constrain what information can be stored, and the data types of stored values • XML documents are not required to have an associated schema • However, schemas are very important for XML data exchange – Otherwise, a site cannot automatically interpret data received from another site • Two mechanisms for specifying XML schema – Document Type Definition (DTD) • Widely used – XML Schema • Newer, not yet widely used

XML Document Schema • Database schemas constrain what information can be stored, and the data types of stored values • XML documents are not required to have an associated schema • However, schemas are very important for XML data exchange – Otherwise, a site cannot automatically interpret data received from another site • Two mechanisms for specifying XML schema – Document Type Definition (DTD) • Widely used – XML Schema • Newer, not yet widely used

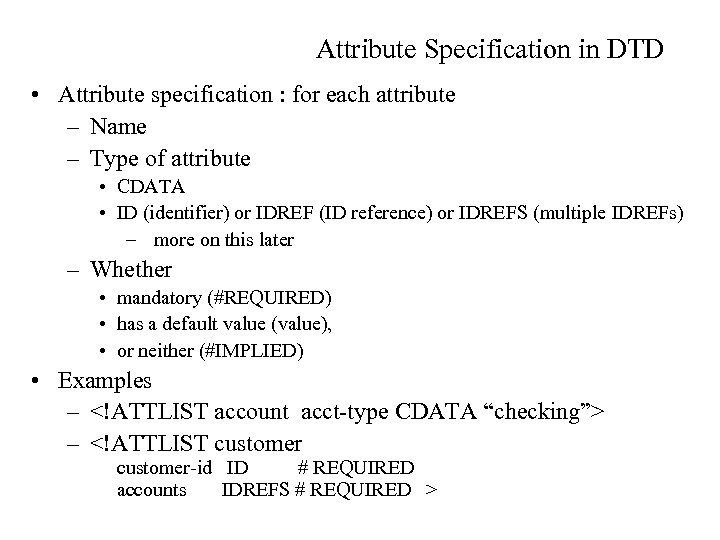

Attribute Specification in DTD • Attribute specification : for each attribute – Name – Type of attribute • CDATA • ID (identifier) or IDREF (ID reference) or IDREFS (multiple IDREFs) – more on this later – Whether • mandatory (#REQUIRED) • has a default value (value), • or neither (#IMPLIED) • Examples – –

Attribute Specification in DTD • Attribute specification : for each attribute – Name – Type of attribute • CDATA • ID (identifier) or IDREF (ID reference) or IDREFS (multiple IDREFs) – more on this later – Whether • mandatory (#REQUIRED) • has a default value (value), • or neither (#IMPLIED) • Examples – –

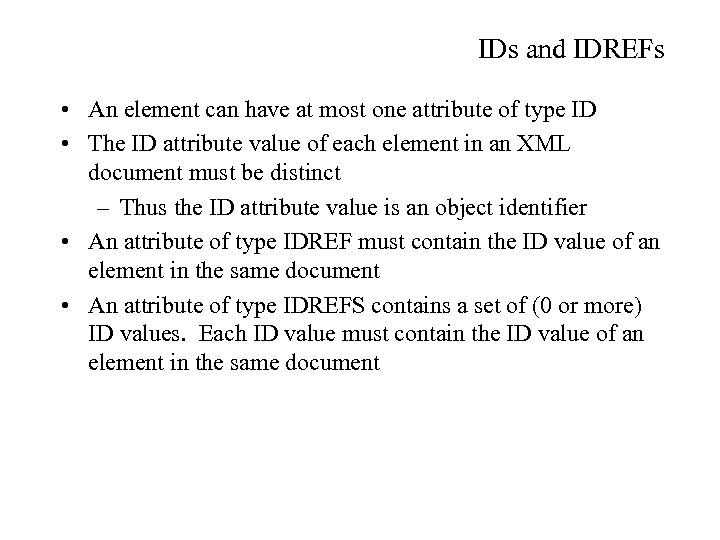

IDs and IDREFs • An element can have at most one attribute of type ID • The ID attribute value of each element in an XML document must be distinct – Thus the ID attribute value is an object identifier • An attribute of type IDREF must contain the ID value of an element in the same document • An attribute of type IDREFS contains a set of (0 or more) ID values. Each ID value must contain the ID value of an element in the same document

IDs and IDREFs • An element can have at most one attribute of type ID • The ID attribute value of each element in an XML document must be distinct – Thus the ID attribute value is an object identifier • An attribute of type IDREF must contain the ID value of an element in the same document • An attribute of type IDREFS contains a set of (0 or more) ID values. Each ID value must contain the ID value of an element in the same document

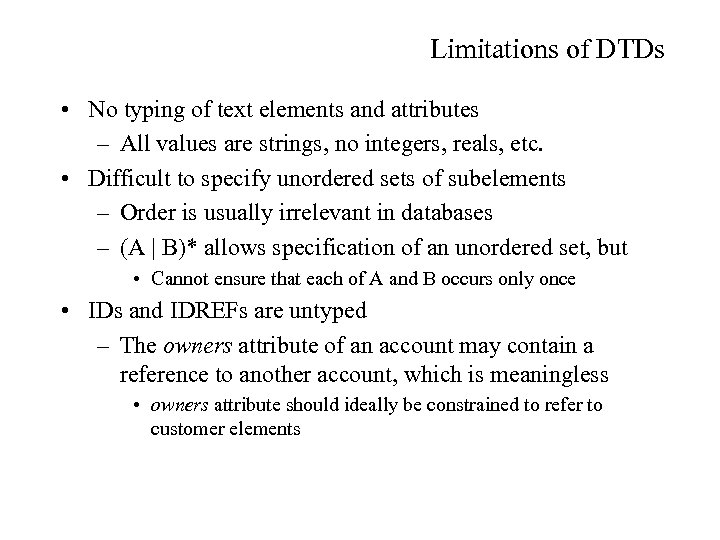

Limitations of DTDs • No typing of text elements and attributes – All values are strings, no integers, reals, etc. • Difficult to specify unordered sets of subelements – Order is usually irrelevant in databases – (A | B)* allows specification of an unordered set, but • Cannot ensure that each of A and B occurs only once • IDs and IDREFs are untyped – The owners attribute of an account may contain a reference to another account, which is meaningless • owners attribute should ideally be constrained to refer to customer elements

Limitations of DTDs • No typing of text elements and attributes – All values are strings, no integers, reals, etc. • Difficult to specify unordered sets of subelements – Order is usually irrelevant in databases – (A | B)* allows specification of an unordered set, but • Cannot ensure that each of A and B occurs only once • IDs and IDREFs are untyped – The owners attribute of an account may contain a reference to another account, which is meaningless • owners attribute should ideally be constrained to refer to customer elements

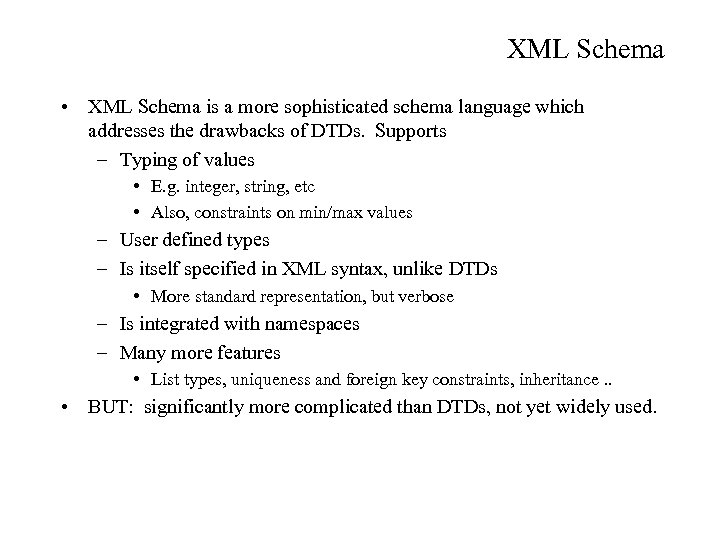

XML Schema • XML Schema is a more sophisticated schema language which addresses the drawbacks of DTDs. Supports – Typing of values • E. g. integer, string, etc • Also, constraints on min/max values – User defined types – Is itself specified in XML syntax, unlike DTDs • More standard representation, but verbose – Is integrated with namespaces – Many more features • List types, uniqueness and foreign key constraints, inheritance. . • BUT: significantly more complicated than DTDs, not yet widely used.

XML Schema • XML Schema is a more sophisticated schema language which addresses the drawbacks of DTDs. Supports – Typing of values • E. g. integer, string, etc • Also, constraints on min/max values – User defined types – Is itself specified in XML syntax, unlike DTDs • More standard representation, but verbose – Is integrated with namespaces – Many more features • List types, uniqueness and foreign key constraints, inheritance. . • BUT: significantly more complicated than DTDs, not yet widely used.

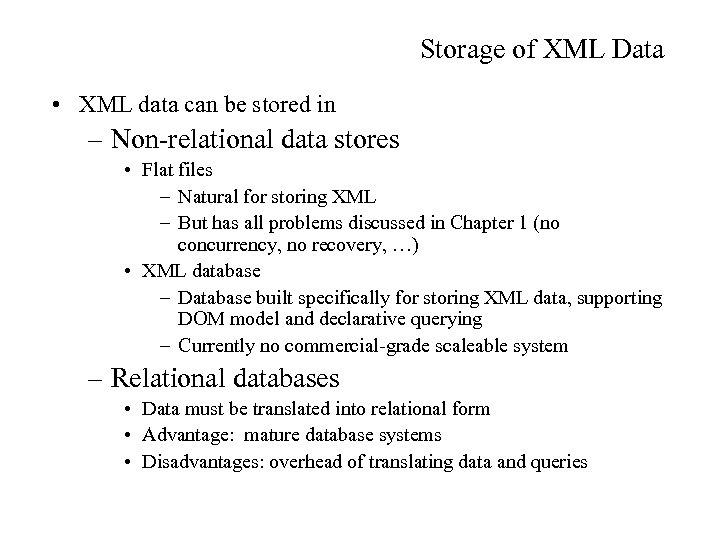

Storage of XML Data • XML data can be stored in – Non-relational data stores • Flat files – Natural for storing XML – But has all problems discussed in Chapter 1 (no concurrency, no recovery, …) • XML database – Database built specifically for storing XML data, supporting DOM model and declarative querying – Currently no commercial-grade scaleable system – Relational databases • Data must be translated into relational form • Advantage: mature database systems • Disadvantages: overhead of translating data and queries

Storage of XML Data • XML data can be stored in – Non-relational data stores • Flat files – Natural for storing XML – But has all problems discussed in Chapter 1 (no concurrency, no recovery, …) • XML database – Database built specifically for storing XML data, supporting DOM model and declarative querying – Currently no commercial-grade scaleable system – Relational databases • Data must be translated into relational form • Advantage: mature database systems • Disadvantages: overhead of translating data and queries

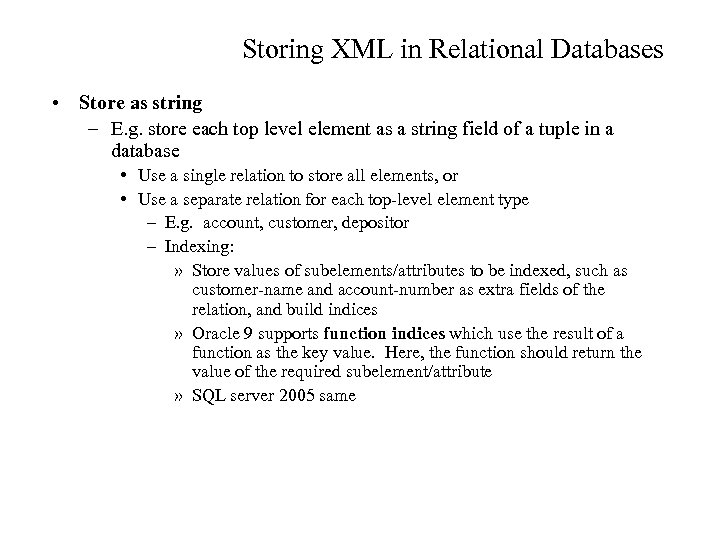

Storing XML in Relational Databases • Store as string – E. g. store each top level element as a string field of a tuple in a database • Use a single relation to store all elements, or • Use a separate relation for each top-level element type – E. g. account, customer, depositor – Indexing: » Store values of subelements/attributes to be indexed, such as customer-name and account-number as extra fields of the relation, and build indices » Oracle 9 supports function indices which use the result of a function as the key value. Here, the function should return the value of the required subelement/attribute » SQL server 2005 same

Storing XML in Relational Databases • Store as string – E. g. store each top level element as a string field of a tuple in a database • Use a single relation to store all elements, or • Use a separate relation for each top-level element type – E. g. account, customer, depositor – Indexing: » Store values of subelements/attributes to be indexed, such as customer-name and account-number as extra fields of the relation, and build indices » Oracle 9 supports function indices which use the result of a function as the key value. Here, the function should return the value of the required subelement/attribute » SQL server 2005 same

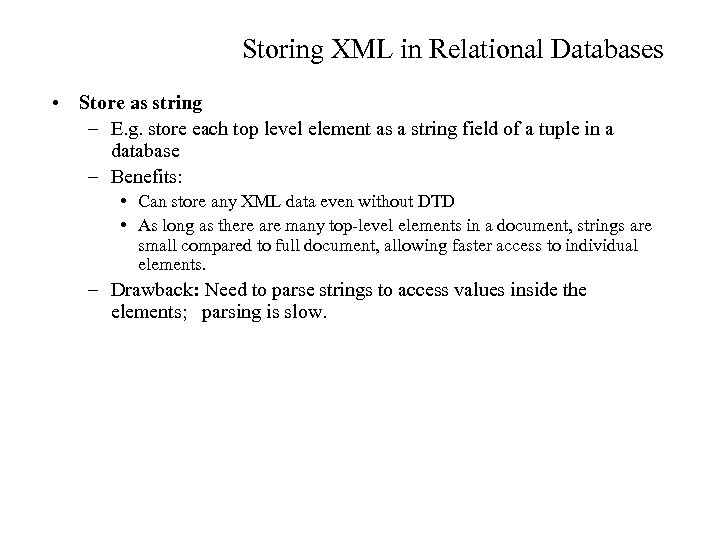

Storing XML in Relational Databases • Store as string – E. g. store each top level element as a string field of a tuple in a database – Benefits: • Can store any XML data even without DTD • As long as there are many top-level elements in a document, strings are small compared to full document, allowing faster access to individual elements. – Drawback: Need to parse strings to access values inside the elements; parsing is slow.

Storing XML in Relational Databases • Store as string – E. g. store each top level element as a string field of a tuple in a database – Benefits: • Can store any XML data even without DTD • As long as there are many top-level elements in a document, strings are small compared to full document, allowing faster access to individual elements. – Drawback: Need to parse strings to access values inside the elements; parsing is slow.

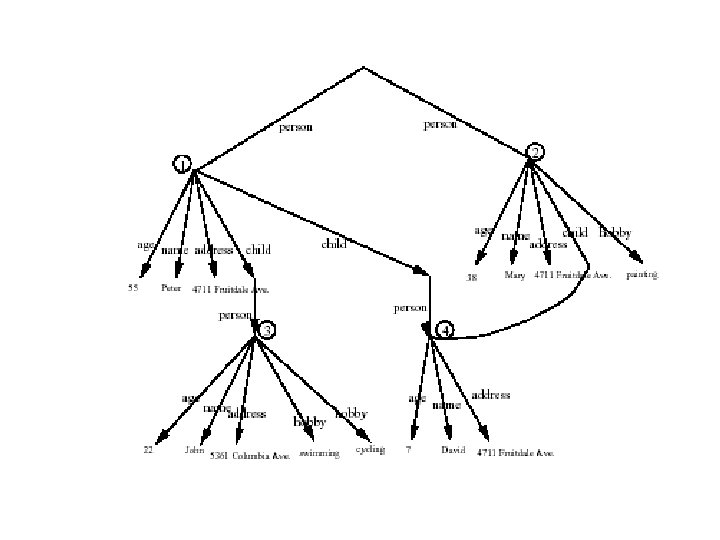

OEM model • Semi structured and XML databases can be modelled as graph-problems • Early prototypes directly supported the graph model as the physical implementation scheme. Querying the graph model was implemented using graph traversals • XML without IDREFS can be modelled as trees

OEM model • Semi structured and XML databases can be modelled as graph-problems • Early prototypes directly supported the graph model as the physical implementation scheme. Querying the graph model was implemented using graph traversals • XML without IDREFS can be modelled as trees

Storing XML as Relations (Cont. ) • Tree representation: model XML data as tree and store using relations nodes(id, type, label, value) child (child-id, parent-id) – Each element/attribute is given a unique identifier – Type indicates element/attribute – Label specifies the tag name of the element/name of attribute – Value is the text value of the element/attribute – The relation child notes the parent-child relationships in the tree • Can add an extra attribute to child to record ordering of children – Benefit: Can store any XML data, even without DTD – Drawbacks: • Data is broken up into too many pieces, increasing space overheads • Even simple queries require a large number of joins, which can be slow

Storing XML as Relations (Cont. ) • Tree representation: model XML data as tree and store using relations nodes(id, type, label, value) child (child-id, parent-id) – Each element/attribute is given a unique identifier – Type indicates element/attribute – Label specifies the tag name of the element/name of attribute – Value is the text value of the element/attribute – The relation child notes the parent-child relationships in the tree • Can add an extra attribute to child to record ordering of children – Benefit: Can store any XML data, even without DTD – Drawbacks: • Data is broken up into too many pieces, increasing space overheads • Even simple queries require a large number of joins, which can be slow

Storing XML in Relations (Cont. ) • Map to relations • If DTD of document is known, you can map data to relations – Bottom-level elements and attributes are mapped to attributes of relations – A relation is created for each element type • An id attribute to store a unique id for each element • all element attributes become relation attributes • All subelements that occur only once become attributes – For text-valued subelements, store the text as attribute value – For complex subelements, store the id of the subelement • Subelements that can occur multiple times represented in a separate table – Similar to handling of multivalued attributes when converting ER diagrams to tables – Benefits: • Efficient storage • Can translate XML queries into SQL, execute efficiently, and then translate SQL results back to XML

Storing XML in Relations (Cont. ) • Map to relations • If DTD of document is known, you can map data to relations – Bottom-level elements and attributes are mapped to attributes of relations – A relation is created for each element type • An id attribute to store a unique id for each element • all element attributes become relation attributes • All subelements that occur only once become attributes – For text-valued subelements, store the text as attribute value – For complex subelements, store the id of the subelement • Subelements that can occur multiple times represented in a separate table – Similar to handling of multivalued attributes when converting ER diagrams to tables – Benefits: • Efficient storage • Can translate XML queries into SQL, execute efficiently, and then translate SQL results back to XML

Alternative mappings • Mapping the structure – The Edge approach – The Attribute approach – The Universal Table approach – The Normalized Universal approach – The Dataguide approach • Mapping values – Separate value tables – Inlining • Shredding

Alternative mappings • Mapping the structure – The Edge approach – The Attribute approach – The Universal Table approach – The Normalized Universal approach – The Dataguide approach • Mapping values – Separate value tables – Inlining • Shredding

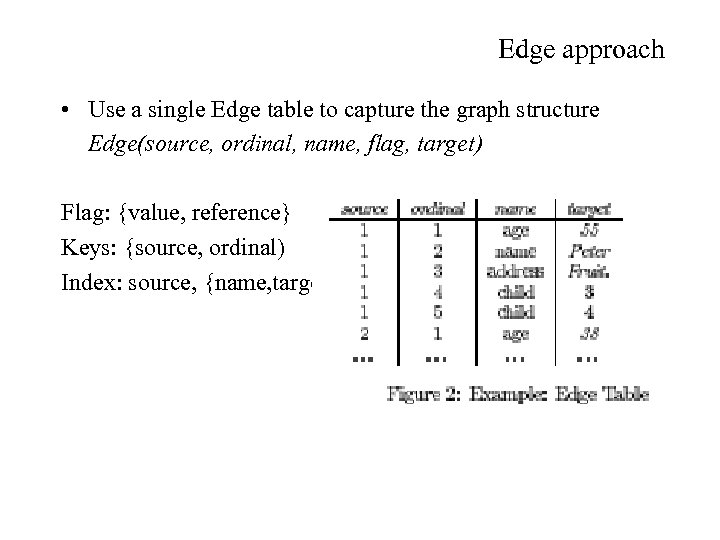

Edge approach • Use a single Edge table to capture the graph structure Edge(source, ordinal, name, flag, target) Flag: {value, reference} Keys: {source, ordinal) Index: source, {name, target}

Edge approach • Use a single Edge table to capture the graph structure Edge(source, ordinal, name, flag, target) Flag: {value, reference} Keys: {source, ordinal) Index: source, {name, target}

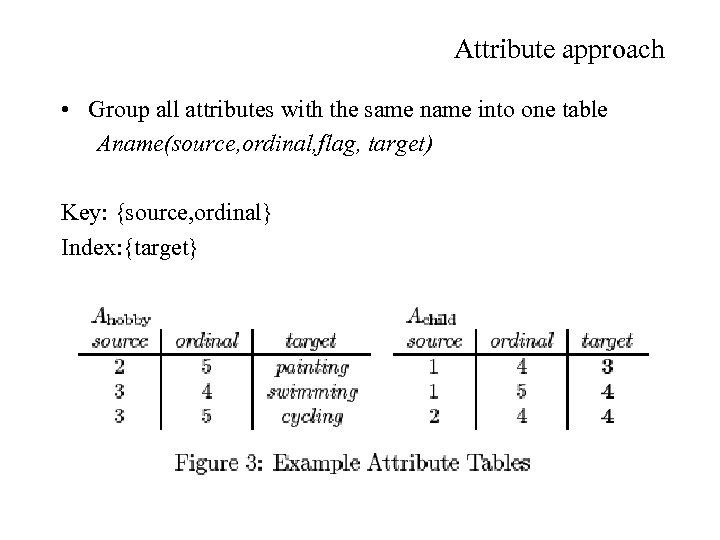

Attribute approach • Group all attributes with the same name into one table Aname(source, ordinal, flag, target) Key: {source, ordinal} Index: {target}

Attribute approach • Group all attributes with the same name into one table Aname(source, ordinal, flag, target) Key: {source, ordinal} Index: {target}

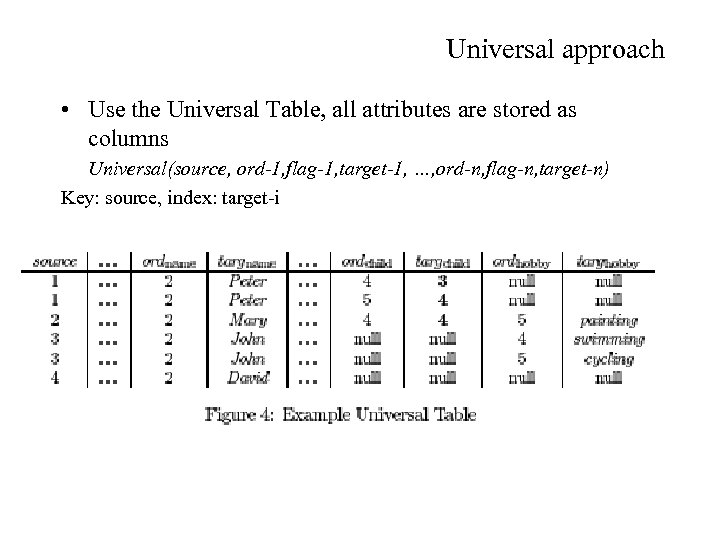

Universal approach • Use the Universal Table, all attributes are stored as columns Universal(source, ord-1, flag-1, target-1, …, ord-n, flag-n, target-n) Key: source, index: target-i

Universal approach • Use the Universal Table, all attributes are stored as columns Universal(source, ord-1, flag-1, target-1, …, ord-n, flag-n, target-n) Key: source, index: target-i

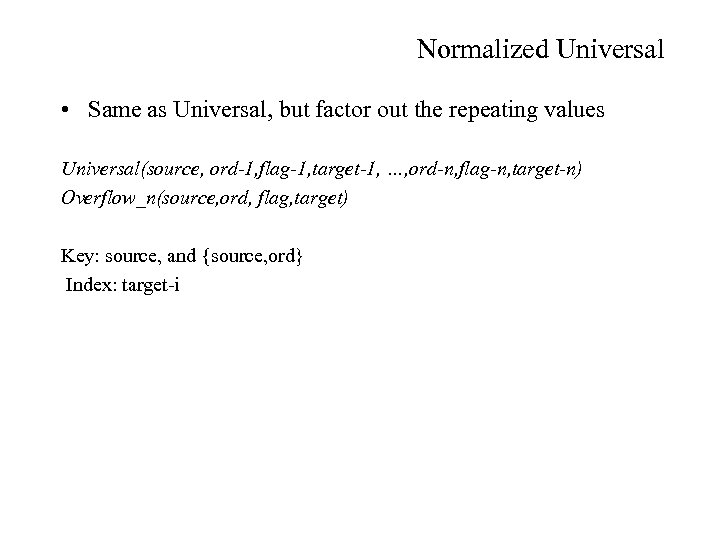

Normalized Universal • Same as Universal, but factor out the repeating values Universal(source, ord-1, flag-1, target-1, …, ord-n, flag-n, target-n) Overflow_n(source, ord, flag, target) Key: source, and {source, ord} Index: target-i

Normalized Universal • Same as Universal, but factor out the repeating values Universal(source, ord-1, flag-1, target-1, …, ord-n, flag-n, target-n) Overflow_n(source, ord, flag, target) Key: source, and {source, ord} Index: target-i

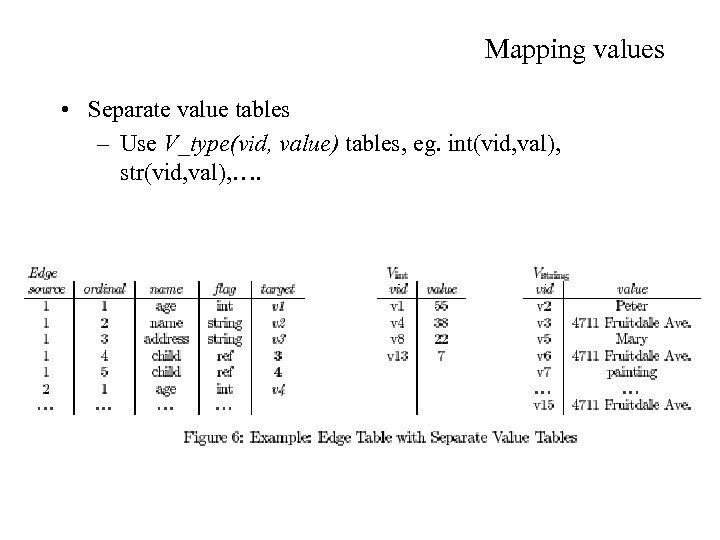

Mapping values • Separate value tables – Use V_type(vid, value) tables, eg. int(vid, val), str(vid, val), ….

Mapping values • Separate value tables – Use V_type(vid, value) tables, eg. int(vid, val), str(vid, val), ….

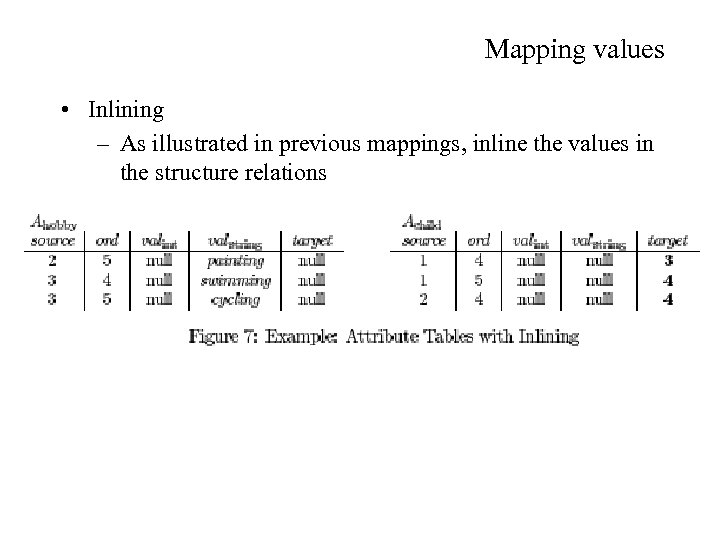

Mapping values • Inlining – As illustrated in previous mappings, inline the values in the structure relations

Mapping values • Inlining – As illustrated in previous mappings, inline the values in the structure relations

Shredding • Try to recognize repeating structures and map them to separate tables • Handle the remainder through any of the previous methods

Shredding • Try to recognize repeating structures and map them to separate tables • Handle the remainder through any of the previous methods

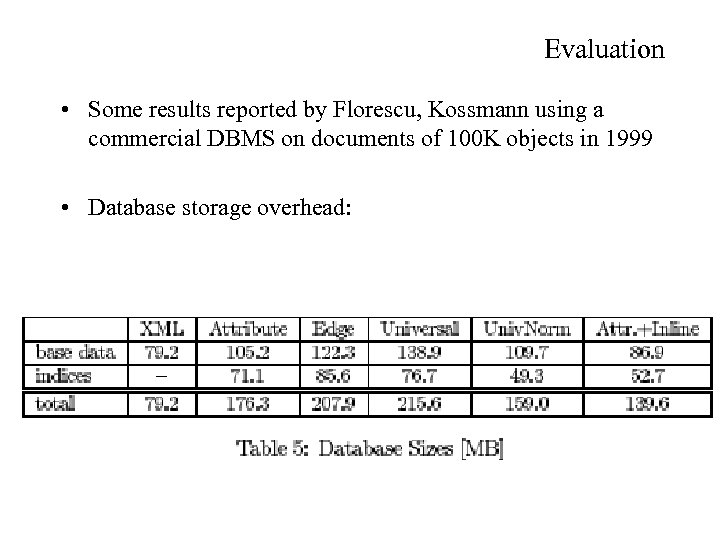

Evaluation • Some results reported by Florescu, Kossmann using a commercial DBMS on documents of 100 K objects in 1999 • Database storage overhead:

Evaluation • Some results reported by Florescu, Kossmann using a commercial DBMS on documents of 100 K objects in 1999 • Database storage overhead:

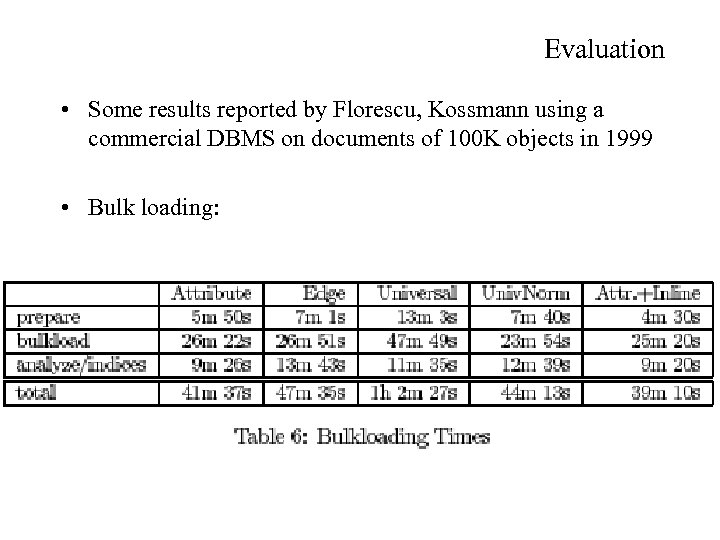

Evaluation • Some results reported by Florescu, Kossmann using a commercial DBMS on documents of 100 K objects in 1999 • Bulk loading:

Evaluation • Some results reported by Florescu, Kossmann using a commercial DBMS on documents of 100 K objects in 1999 • Bulk loading:

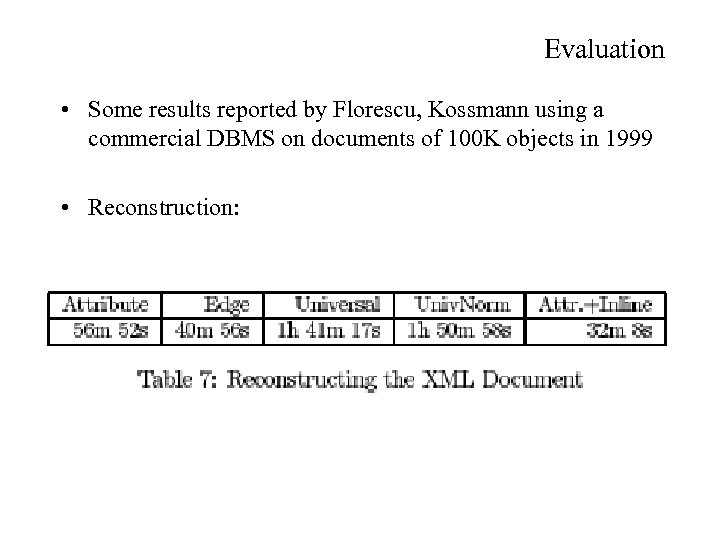

Evaluation • Some results reported by Florescu, Kossmann using a commercial DBMS on documents of 100 K objects in 1999 • Reconstruction:

Evaluation • Some results reported by Florescu, Kossmann using a commercial DBMS on documents of 100 K objects in 1999 • Reconstruction:

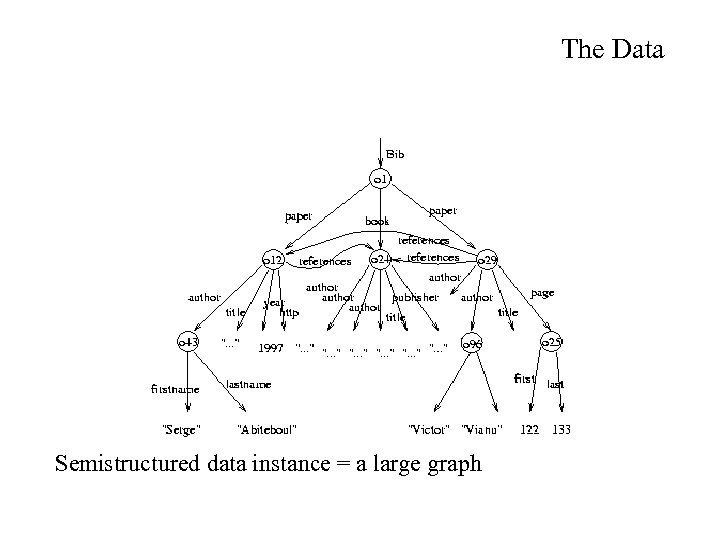

The Data Semistructured data instance = a large graph

The Data Semistructured data instance = a large graph

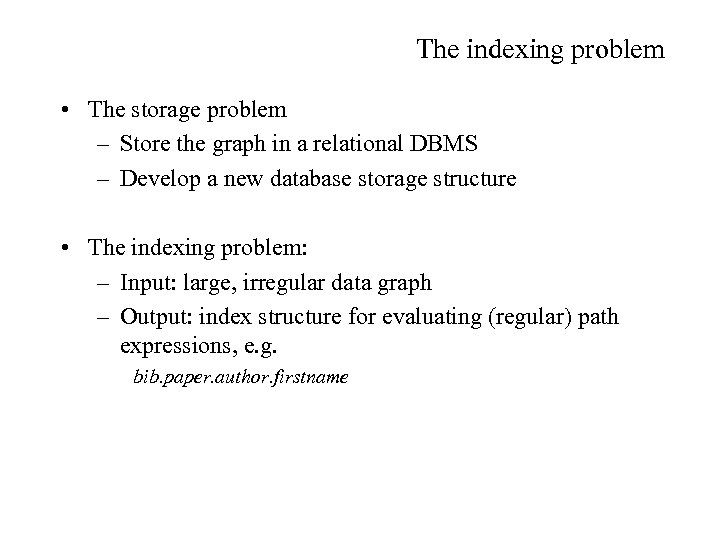

The indexing problem • The storage problem – Store the graph in a relational DBMS – Develop a new database storage structure • The indexing problem: – Input: large, irregular data graph – Output: index structure for evaluating (regular) path expressions, e. g. bib. paper. author. firstname

The indexing problem • The storage problem – Store the graph in a relational DBMS – Develop a new database storage structure • The indexing problem: – Input: large, irregular data graph – Output: index structure for evaluating (regular) path expressions, e. g. bib. paper. author. firstname

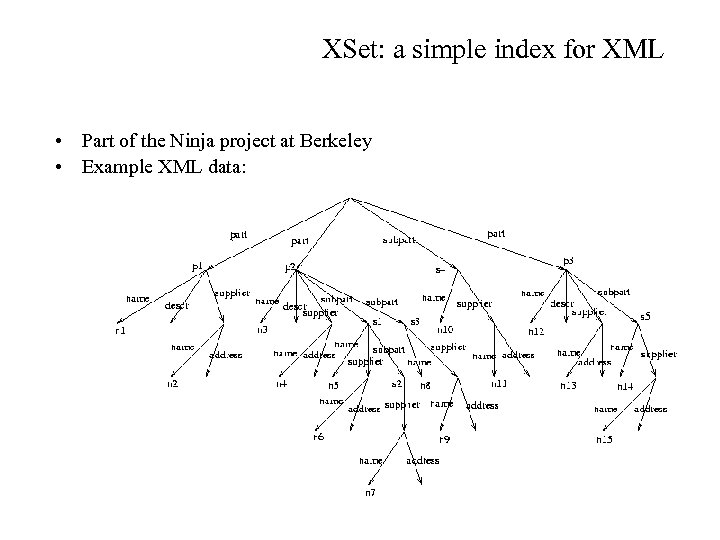

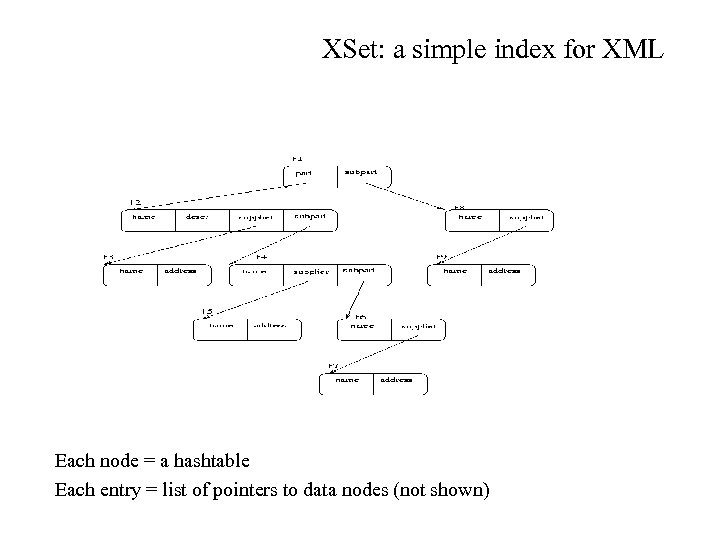

XSet: a simple index for XML • Part of the Ninja project at Berkeley • Example XML data:

XSet: a simple index for XML • Part of the Ninja project at Berkeley • Example XML data:

XSet: a simple index for XML Each node = a hashtable Each entry = list of pointers to data nodes (not shown)

XSet: a simple index for XML Each node = a hashtable Each entry = list of pointers to data nodes (not shown)

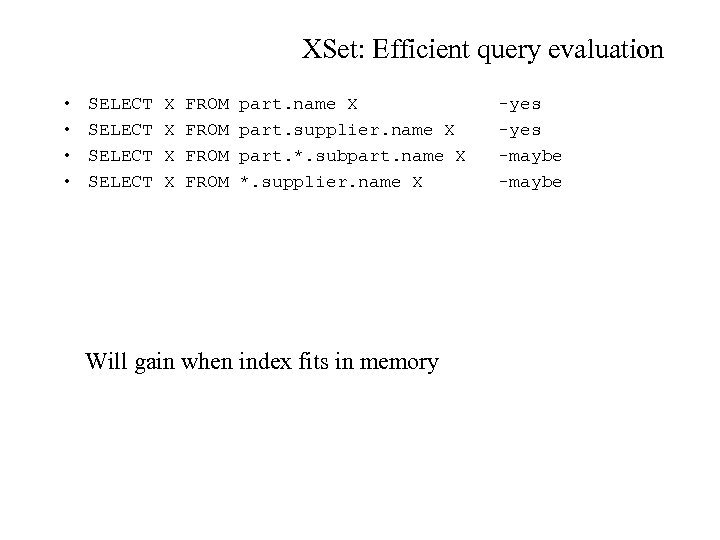

XSet: Efficient query evaluation • • SELECT X X FROM part. name X part. supplier. name X part. *. subpart. name X *. supplier. name X Will gain when index fits in memory -yes -maybe

XSet: Efficient query evaluation • • SELECT X X FROM part. name X part. supplier. name X part. *. subpart. name X *. supplier. name X Will gain when index fits in memory -yes -maybe

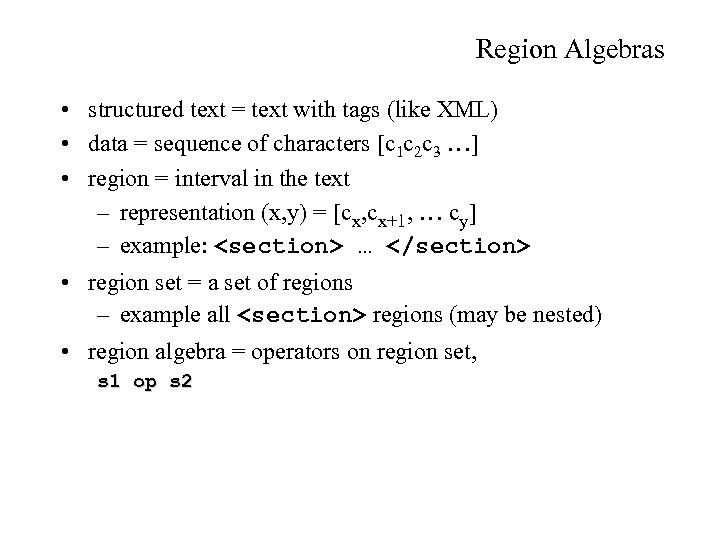

Region Algebras • structured text = text with tags (like XML) • data = sequence of characters [c 1 c 2 c 3 …] • region = interval in the text – representation (x, y) = [cx, cx+1, … cy] – example:

Region Algebras • structured text = text with tags (like XML) • data = sequence of characters [c 1 c 2 c 3 …] • region = interval in the text – representation (x, y) = [cx, cx+1, … cy] – example:

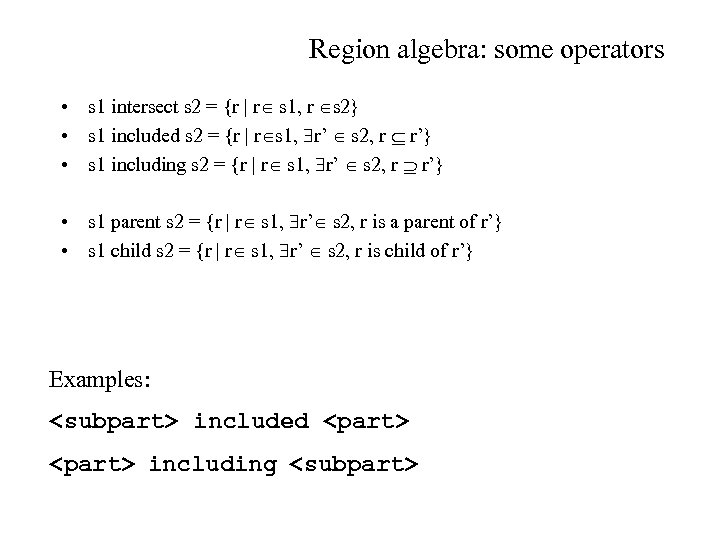

Region algebra: some operators • s 1 intersect s 2 = {r | r s 1, r s 2} • s 1 included s 2 = {r | r s 1, r’ s 2, r r’} • s 1 including s 2 = {r | r s 1, r’ s 2, r r’} • s 1 parent s 2 = {r | r s 1, r’ s 2, r is a parent of r’} • s 1 child s 2 = {r | r s 1, r’ s 2, r is child of r’} Examples:

Region algebra: some operators • s 1 intersect s 2 = {r | r s 1, r s 2} • s 1 included s 2 = {r | r s 1, r’ s 2, r r’} • s 1 including s 2 = {r | r s 1, r’ s 2, r r’} • s 1 parent s 2 = {r | r s 1, r’ s 2, r is a parent of r’} • s 1 child s 2 = {r | r s 1, r’ s 2, r is child of r’} Examples:

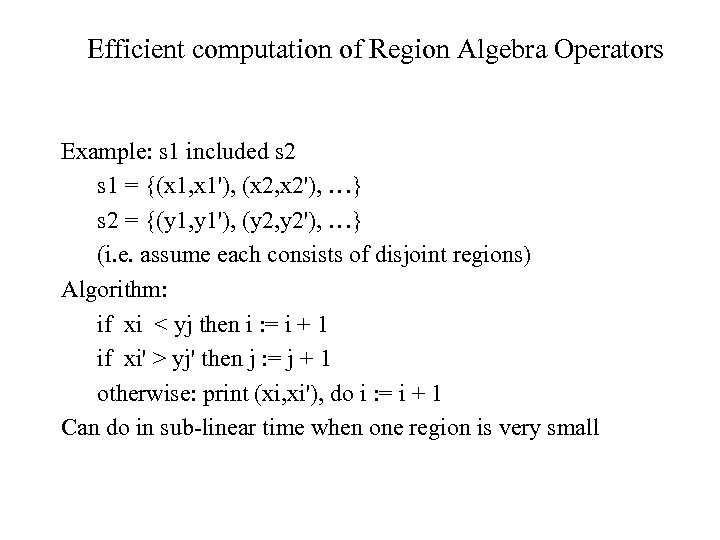

Efficient computation of Region Algebra Operators Example: s 1 included s 2 s 1 = {(x 1, x 1'), (x 2, x 2'), …} s 2 = {(y 1, y 1'), (y 2, y 2'), …} (i. e. assume each consists of disjoint regions) Algorithm: if xi < yj then i : = i + 1 if xi' > yj' then j : = j + 1 otherwise: print (xi, xi'), do i : = i + 1 Can do in sub-linear time when one region is very small

Efficient computation of Region Algebra Operators Example: s 1 included s 2 s 1 = {(x 1, x 1'), (x 2, x 2'), …} s 2 = {(y 1, y 1'), (y 2, y 2'), …} (i. e. assume each consists of disjoint regions) Algorithm: if xi < yj then i : = i + 1 if xi' > yj' then j : = j + 1 otherwise: print (xi, xi'), do i : = i + 1 Can do in sub-linear time when one region is very small

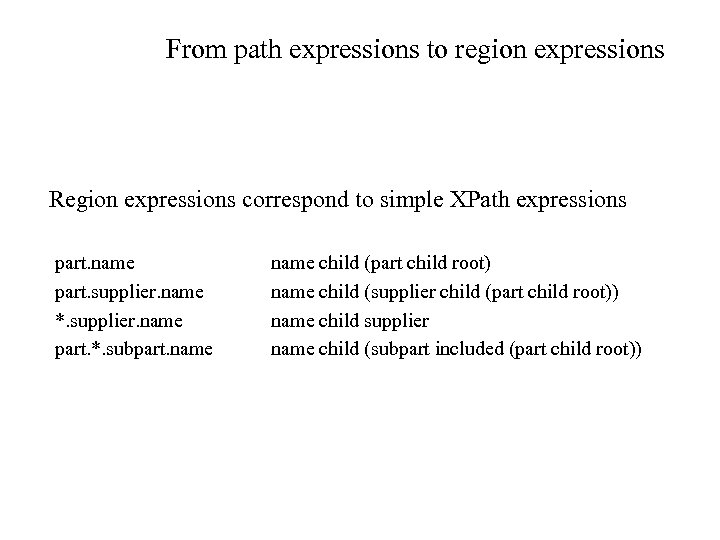

From path expressions to region expressions Region expressions correspond to simple XPath expressions part. name part. supplier. name *. supplier. name part. *. subpart. name child (part child root) name child (supplier child (part child root)) name child supplier name child (subpart included (part child root))

From path expressions to region expressions Region expressions correspond to simple XPath expressions part. name part. supplier. name *. supplier. name part. *. subpart. name child (part child root) name child (supplier child (part child root)) name child supplier name child (subpart included (part child root))

Storage structures for region algebras • Every node is characterised by an integer pair (x, y) • This means we have a 2 -d space • Any 2 -d space data structure can be used • If you use a (pre-order, post-order) numbering you get triangular filling of 2 -d (to be discussed later)

Storage structures for region algebras • Every node is characterised by an integer pair (x, y) • This means we have a 2 -d space • Any 2 -d space data structure can be used • If you use a (pre-order, post-order) numbering you get triangular filling of 2 -d (to be discussed later)

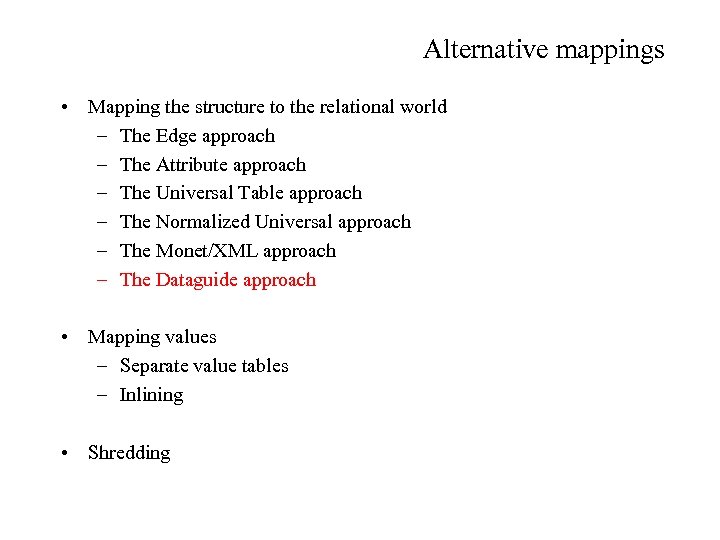

Alternative mappings • Mapping the structure to the relational world – The Edge approach – The Attribute approach – The Universal Table approach – The Normalized Universal approach – The Monet/XML approach – The Dataguide approach • Mapping values – Separate value tables – Inlining • Shredding

Alternative mappings • Mapping the structure to the relational world – The Edge approach – The Attribute approach – The Universal Table approach – The Normalized Universal approach – The Monet/XML approach – The Dataguide approach • Mapping values – Separate value tables – Inlining • Shredding

Dataguide approach • Developed in the context of Lore, Lorel (Stanford Univ) • Predecessor of the Monet/XML model • Observation: – queries in the graph-representation take a limited form – they are partial walks from the root to an object of interest – this behaviour was stressed by the query language Lorel, i. e. an SQL-based query language based on processing regular expressions SELECT X FROM (Bib. *. author). (lastname|firstname). Abiteboul X

Dataguide approach • Developed in the context of Lore, Lorel (Stanford Univ) • Predecessor of the Monet/XML model • Observation: – queries in the graph-representation take a limited form – they are partial walks from the root to an object of interest – this behaviour was stressed by the query language Lorel, i. e. an SQL-based query language based on processing regular expressions SELECT X FROM (Bib. *. author). (lastname|firstname). Abiteboul X

Data. Guides Definition given a semistructured data instance DB, a Data. Guide for DB is a graph G s. t. : - every path in DB also occurs in G - every path in G occurs in DB - every path in G is unique

Data. Guides Definition given a semistructured data instance DB, a Data. Guide for DB is a graph G s. t. : - every path in DB also occurs in G - every path in G occurs in DB - every path in G is unique

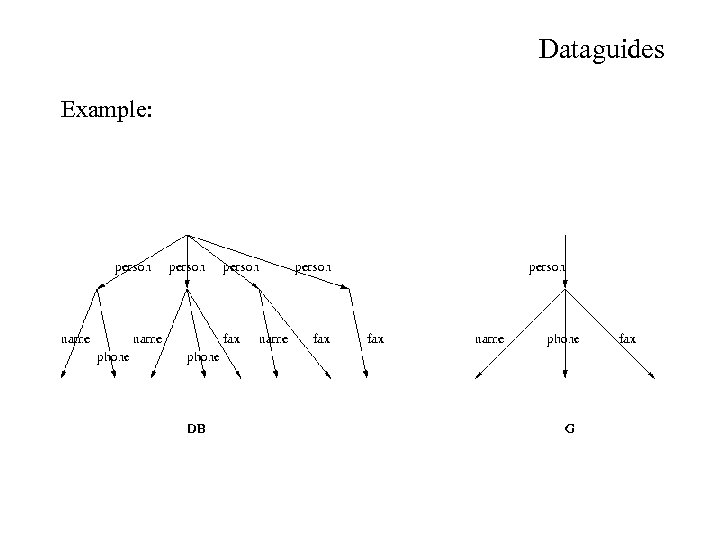

Dataguides Example:

Dataguides Example:

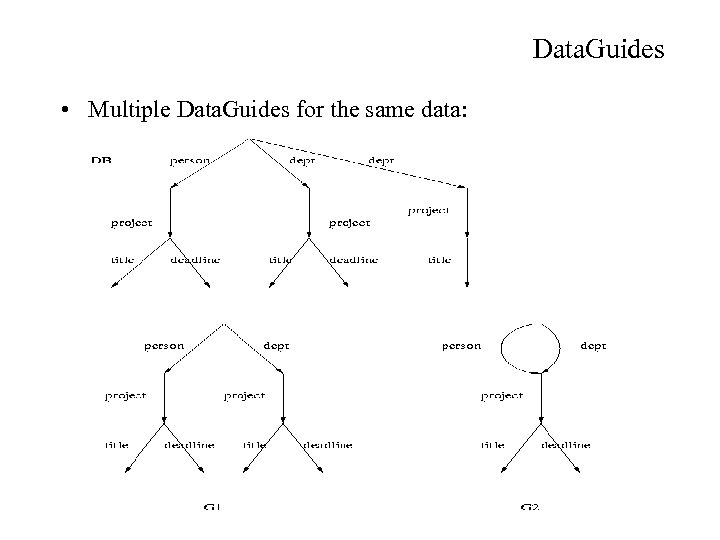

Data. Guides • Multiple Data. Guides for the same data:

Data. Guides • Multiple Data. Guides for the same data:

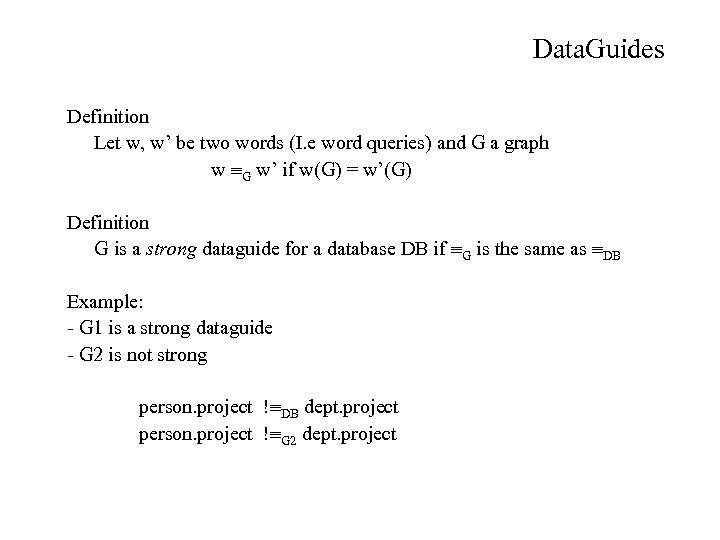

Data. Guides Definition Let w, w’ be two words (I. e word queries) and G a graph w G w’ if w(G) = w’(G) Definition G is a strong dataguide for a database DB if G is the same as DB Example: - G 1 is a strong dataguide - G 2 is not strong person. project ! DB dept. project person. project ! G 2 dept. project

Data. Guides Definition Let w, w’ be two words (I. e word queries) and G a graph w G w’ if w(G) = w’(G) Definition G is a strong dataguide for a database DB if G is the same as DB Example: - G 1 is a strong dataguide - G 2 is not strong person. project ! DB dept. project person. project ! G 2 dept. project

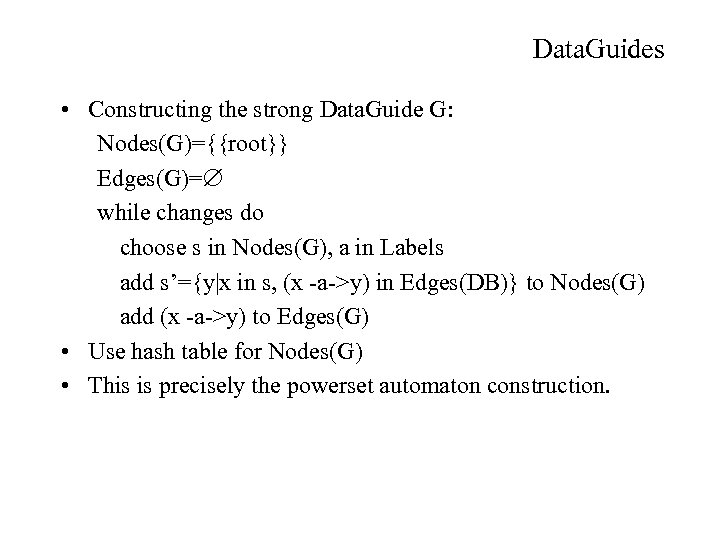

Data. Guides • Constructing the strong Data. Guide G: Nodes(G)={{root}} Edges(G)= while changes do choose s in Nodes(G), a in Labels add s’={y|x in s, (x -a->y) in Edges(DB)} to Nodes(G) add (x -a->y) to Edges(G) • Use hash table for Nodes(G) • This is precisely the powerset automaton construction.

Data. Guides • Constructing the strong Data. Guide G: Nodes(G)={{root}} Edges(G)= while changes do choose s in Nodes(G), a in Labels add s’={y|x in s, (x -a->y) in Edges(DB)} to Nodes(G) add (x -a->y) to Edges(G) • Use hash table for Nodes(G) • This is precisely the powerset automaton construction.

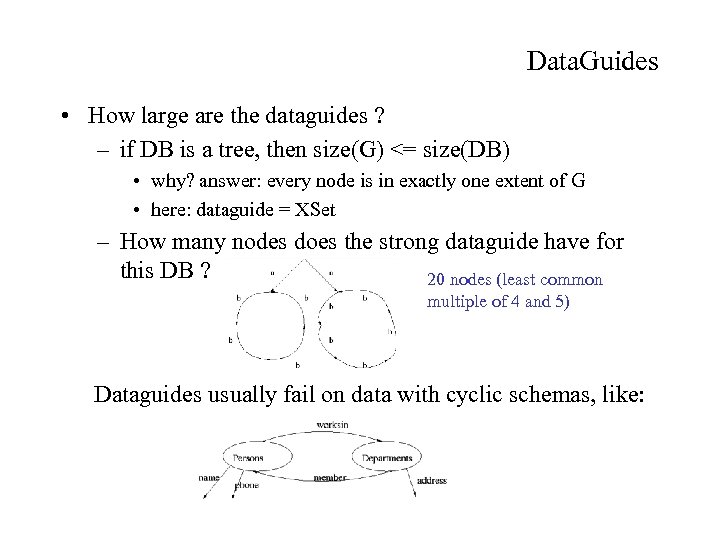

Data. Guides • How large are the dataguides ? – if DB is a tree, then size(G) <= size(DB) • why? answer: every node is in exactly one extent of G • here: dataguide = XSet – How many nodes does the strong dataguide have for this DB ? 20 nodes (least common multiple of 4 and 5) Dataguides usually fail on data with cyclic schemas, like:

Data. Guides • How large are the dataguides ? – if DB is a tree, then size(G) <= size(DB) • why? answer: every node is in exactly one extent of G • here: dataguide = XSet – How many nodes does the strong dataguide have for this DB ? 20 nodes (least common multiple of 4 and 5) Dataguides usually fail on data with cyclic schemas, like: