CHAPTER 1. GENERAL PHYSIOLOGY

CHAPTER 1. GENERAL PHYSIOLOGY

1. Medical Physiology: The Big Picture. Jonatan D. Kibble, Colby R Halsey. 2009. 2. Textbook of Medical Physiology. Arthur C. Guyton, John E. Hall. 2000. 3. Human physiology–Atlases. Stefan Silbernagl. 2009. 4. Netter’s Atlas of human physiology. John T. Hansen, Bruse M. Koeppen. 2009.

1. Medical Physiology: The Big Picture. Jonatan D. Kibble, Colby R Halsey. 2009. 2. Textbook of Medical Physiology. Arthur C. Guyton, John E. Hall. 2000. 3. Human physiology–Atlases. Stefan Silbernagl. 2009. 4. Netter’s Atlas of human physiology. John T. Hansen, Bruse M. Koeppen. 2009.

CHAPTER 1. GENERAL PHYSIOLOGY 1. 1. Homeostasis 1. 2. The internal environment 1. 3. Membrane transport mechanisms 1. 3. 1. The electrochemical gradient 1. 3. 2. Classification of membrane transport systems 1. 4. Membrane potentials 1. 4. 1. Ionic basis of membrane potentials 1. 4. 2. Resting membrane potential 1. 5. Action potential 1. 6. Refractory periods 1. 7. Action potential propagation

CHAPTER 1. GENERAL PHYSIOLOGY 1. 1. Homeostasis 1. 2. The internal environment 1. 3. Membrane transport mechanisms 1. 3. 1. The electrochemical gradient 1. 3. 2. Classification of membrane transport systems 1. 4. Membrane potentials 1. 4. 1. Ionic basis of membrane potentials 1. 4. 2. Resting membrane potential 1. 5. Action potential 1. 6. Refractory periods 1. 7. Action potential propagation

1. 8. Synaptic transmission 1. 9. Skeletal muscle 1. 9. 1. Neuromuscular junction 1. 9. 2. Sarcomeres 1. 9. 3. Molecular components of sarcomeres 1. 9. 4. Sliding filament theory 1. 9. 5. Force of contraction 1. 9. 6. Skeletal muscle diversity 1. 10. Smooth muscle

1. 8. Synaptic transmission 1. 9. Skeletal muscle 1. 9. 1. Neuromuscular junction 1. 9. 2. Sarcomeres 1. 9. 3. Molecular components of sarcomeres 1. 9. 4. Sliding filament theory 1. 9. 5. Force of contraction 1. 9. 6. Skeletal muscle diversity 1. 10. Smooth muscle

1. 1. Homeostasis

1. 1. Homeostasis

Physiology (physis - nature, logos – nature) –is concerned with how a state of health and wellness is maintained in a person and, therefore, it takes a global view of how the body systems function and how they are controlled.

Physiology (physis - nature, logos – nature) –is concerned with how a state of health and wellness is maintained in a person and, therefore, it takes a global view of how the body systems function and how they are controlled.

There are 10 body systems, each with unique contributions to body function (Table 1 -1).

There are 10 body systems, each with unique contributions to body function (Table 1 -1).

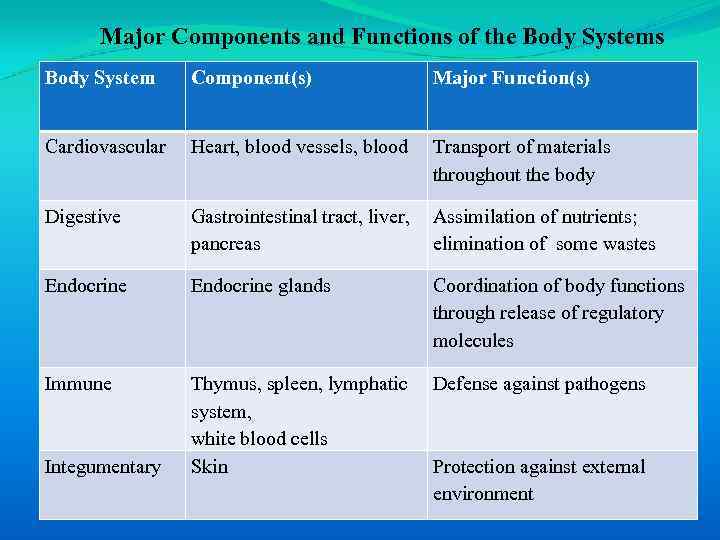

Major Components and Functions of the Body Systems Body System Component(s) Major Function(s) Cardiovascular Heart, blood vessels, blood Transport of materials throughout the body Digestive Gastrointestinal tract, liver, pancreas Assimilation of nutrients; elimination of some wastes Endocrine glands Coordination of body functions through release of regulatory molecules Immune Thymus, spleen, lymphatic system, white blood cells Skin Defense against pathogens Integumentary Protection against external environment

Major Components and Functions of the Body Systems Body System Component(s) Major Function(s) Cardiovascular Heart, blood vessels, blood Transport of materials throughout the body Digestive Gastrointestinal tract, liver, pancreas Assimilation of nutrients; elimination of some wastes Endocrine glands Coordination of body functions through release of regulatory molecules Immune Thymus, spleen, lymphatic system, white blood cells Skin Defense against pathogens Integumentary Protection against external environment

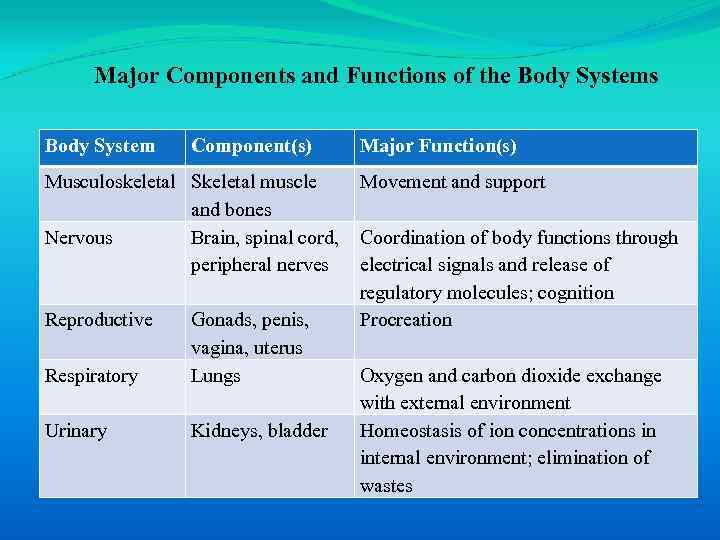

Major Components and Functions of the Body Systems Body System Component(s) Musculoskeletal Skeletal muscle and bones Nervous Brain, spinal cord, peripheral nerves Reproductive Respiratory Gonads, penis, vagina, uterus Lungs Urinary Kidneys, bladder Major Function(s) Movement and support Coordination of body functions through electrical signals and release of regulatory molecules; cognition Procreation Oxygen and carbon dioxide exchange with external environment Homeostasis of ion concentrations in internal environment; elimination of wastes

Major Components and Functions of the Body Systems Body System Component(s) Musculoskeletal Skeletal muscle and bones Nervous Brain, spinal cord, peripheral nerves Reproductive Respiratory Gonads, penis, vagina, uterus Lungs Urinary Kidneys, bladder Major Function(s) Movement and support Coordination of body functions through electrical signals and release of regulatory molecules; cognition Procreation Oxygen and carbon dioxide exchange with external environment Homeostasis of ion concentrations in internal environment; elimination of wastes

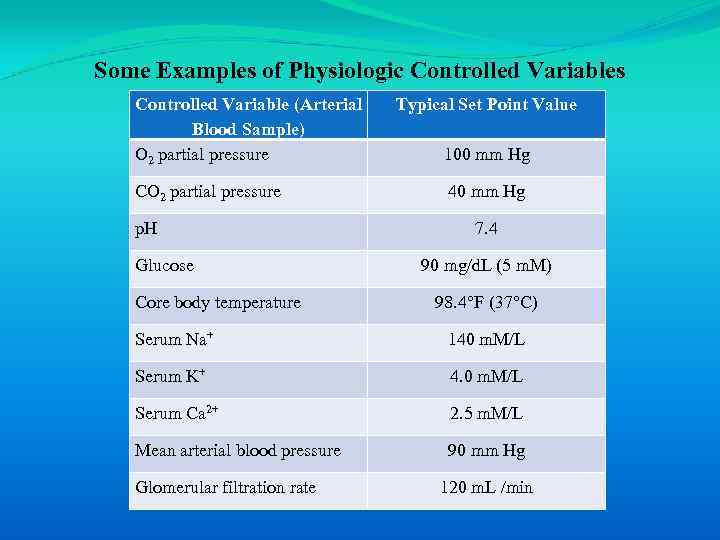

However, it is the integration of the body systems that allows the creation of a stable internal environment in which cells are able to function. Such ability to maintain a stable internal environment is a central concept in physiology and is referred to as homeostasis. The stability of the body’s internal environment is defined by the maintenance of several physiologic controlled variables within narrow normal ranges (Table 1 -2).

However, it is the integration of the body systems that allows the creation of a stable internal environment in which cells are able to function. Such ability to maintain a stable internal environment is a central concept in physiology and is referred to as homeostasis. The stability of the body’s internal environment is defined by the maintenance of several physiologic controlled variables within narrow normal ranges (Table 1 -2).

Some Examples of Physiologic Controlled Variables Controlled Variable (Arterial Blood Sample) O 2 partial pressure CO 2 partial pressure p. H Glucose Core body temperature Typical Set Point Value 100 mm Hg 40 mm Hg 7. 4 90 mg/d. L (5 m. M) 98. 4°F (37°C) Serum Na+ 140 m. M/L Serum K+ 4. 0 m. M/L Serum Ca 2+ 2. 5 m. M/L Mean arterial blood pressure 90 mm Hg Glomerular filtration rate 120 m. L /min

Some Examples of Physiologic Controlled Variables Controlled Variable (Arterial Blood Sample) O 2 partial pressure CO 2 partial pressure p. H Glucose Core body temperature Typical Set Point Value 100 mm Hg 40 mm Hg 7. 4 90 mg/d. L (5 m. M) 98. 4°F (37°C) Serum Na+ 140 m. M/L Serum K+ 4. 0 m. M/L Serum Ca 2+ 2. 5 m. M/L Mean arterial blood pressure 90 mm Hg Glomerular filtration rate 120 m. L /min

Homeostasis - a stable internal environment in which cells are able to function. Pathological states occur when homeostasis is not maintained.

Homeostasis - a stable internal environment in which cells are able to function. Pathological states occur when homeostasis is not maintained.

1. 2. The internal environment

1. 2. The internal environment

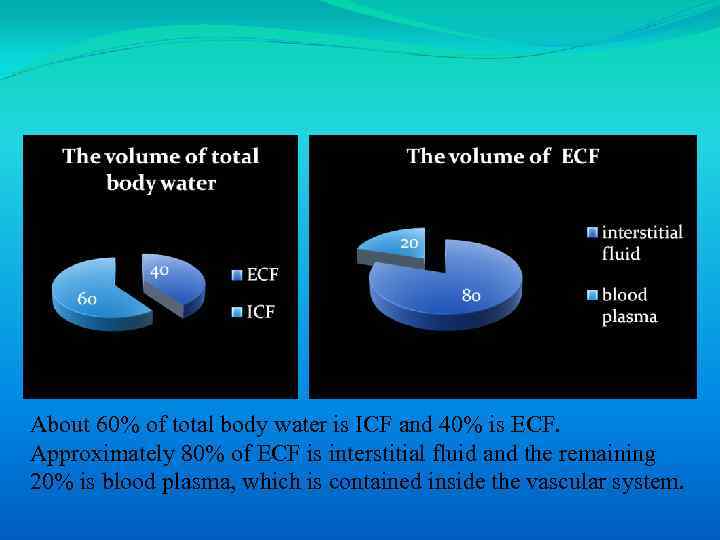

The goal of homeostasis is to provide an optimal fluid environment for cellular function. The body fluids are divided into two major functional compartments: 1. The fluid inside cells, is the intracellular fluid (ICF) compartment. 2. The fluid outside cells is the extracellular fluid (ECF) is subdivided into the interstitial fluid and the blood plasma.

The goal of homeostasis is to provide an optimal fluid environment for cellular function. The body fluids are divided into two major functional compartments: 1. The fluid inside cells, is the intracellular fluid (ICF) compartment. 2. The fluid outside cells is the extracellular fluid (ECF) is subdivided into the interstitial fluid and the blood plasma.

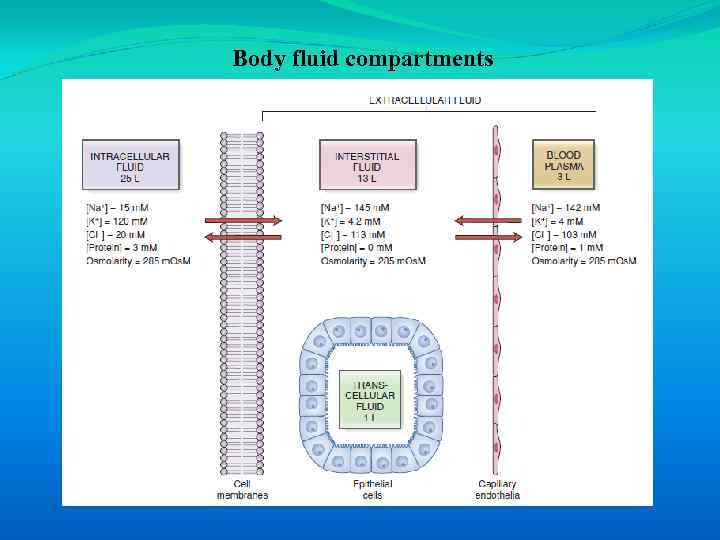

Body fluid compartments

Body fluid compartments

The concept of an internal environment in the body correlates with the interstitial fluid bathing cells. There is free exchange of water and small solutes between interstitial fluid and plasma across the blood capillaries. In contrast, the exchange of most substances between interstitial fluid and intracellular fluid is highly regulated and occurs across plasma cell membranes.

The concept of an internal environment in the body correlates with the interstitial fluid bathing cells. There is free exchange of water and small solutes between interstitial fluid and plasma across the blood capillaries. In contrast, the exchange of most substances between interstitial fluid and intracellular fluid is highly regulated and occurs across plasma cell membranes.

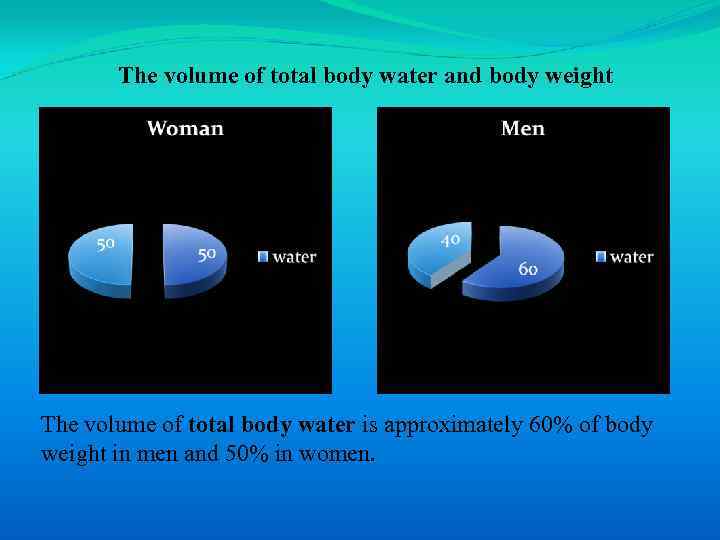

The volume of total body water and body weight The volume of total body water is approximately 60% of body weight in men and 50% in women.

The volume of total body water and body weight The volume of total body water is approximately 60% of body weight in men and 50% in women.

About 60% of total body water is ICF and 40% is ECF. Approximately 80% of ECF is interstitial fluid and the remaining 20% is blood plasma, which is contained inside the vascular system.

About 60% of total body water is ICF and 40% is ECF. Approximately 80% of ECF is interstitial fluid and the remaining 20% is blood plasma, which is contained inside the vascular system.

1. 3. Membrane transport mechanisms

1. 3. Membrane transport mechanisms

Cells constantly exchange solutes (e. g. , nutrients, wastes, and respiratory gases) with the interstitial fluid. The transport of solutes across cell membranes is fundamental to the survival of all cells, and the transport mechanisms are therefore present in all cells. Specializations in membrane transport mechanisms often underlie tissue function. For example, excitable tissues express many voltage-sensitive membrane transport systems that account for the ability to generate and propagate electrical signals.

Cells constantly exchange solutes (e. g. , nutrients, wastes, and respiratory gases) with the interstitial fluid. The transport of solutes across cell membranes is fundamental to the survival of all cells, and the transport mechanisms are therefore present in all cells. Specializations in membrane transport mechanisms often underlie tissue function. For example, excitable tissues express many voltage-sensitive membrane transport systems that account for the ability to generate and propagate electrical signals.

1. 3. 1. The electrochemical gradient

1. 3. 1. The electrochemical gradient

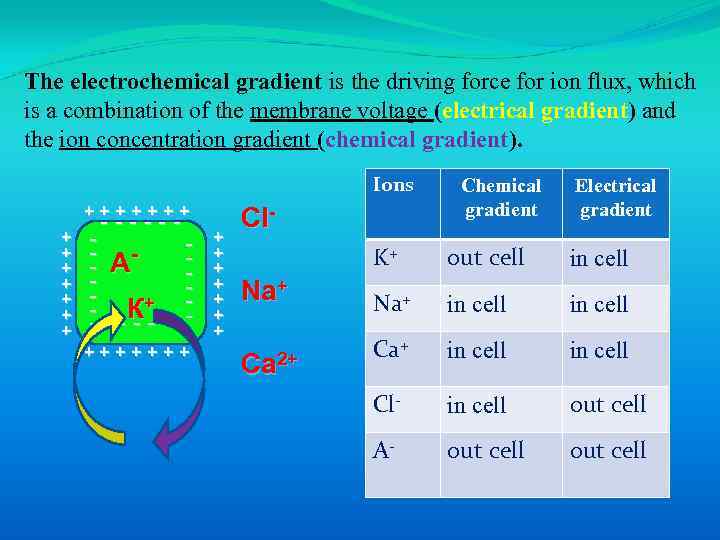

The electrochemical gradient is the driving force for ion flux, which is a combination of the membrane voltage (electrical gradient) and the ion concentration gradient (chemical gradient).

The electrochemical gradient is the driving force for ion flux, which is a combination of the membrane voltage (electrical gradient) and the ion concentration gradient (chemical gradient).

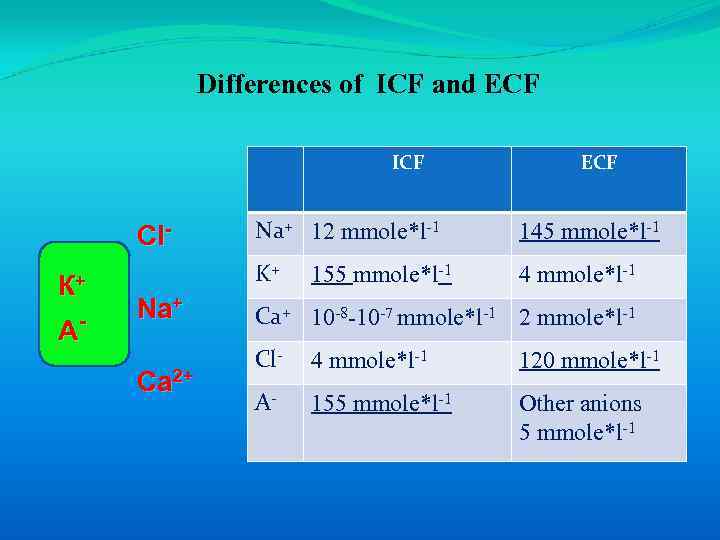

Differences of ICF and ECF ICF А- Na+ Ca 2+ Na+ 12 mmole*l-1 145 mmole*l-1 K+ Cl. К+ ECF 4 mmole*l-1 155 mmole*l-1 Ca+ 10 -8 -10 -7 mmole*l-1 2 mmole*l-1 Cl- 4 mmole*l-1 120 mmole*l-1 A- 155 mmole*l-1 Other anions 5 mmole*l-1

Differences of ICF and ECF ICF А- Na+ Ca 2+ Na+ 12 mmole*l-1 145 mmole*l-1 K+ Cl. К+ ECF 4 mmole*l-1 155 mmole*l-1 Ca+ 10 -8 -10 -7 mmole*l-1 2 mmole*l-1 Cl- 4 mmole*l-1 120 mmole*l-1 A- 155 mmole*l-1 Other anions 5 mmole*l-1

The electrochemical gradient is the driving force for ion flux, which is a combination of the membrane voltage (electrical gradient) and the ion concentration gradient (chemical gradient). Ions +++++++ + + + ------ - А - К+ - - - -- +++++++ + + + Cl- Chemical gradient Electrical gradient K+ Na+ Ca 2+ out cell in cell Na+ in cell Cl- in cell out cell A- out cell

The electrochemical gradient is the driving force for ion flux, which is a combination of the membrane voltage (electrical gradient) and the ion concentration gradient (chemical gradient). Ions +++++++ + + + ------ - А - К+ - - - -- +++++++ + + + Cl- Chemical gradient Electrical gradient K+ Na+ Ca 2+ out cell in cell Na+ in cell Cl- in cell out cell A- out cell

1. 3. 2. Classification of membrane transport systems

1. 3. 2. Classification of membrane transport systems

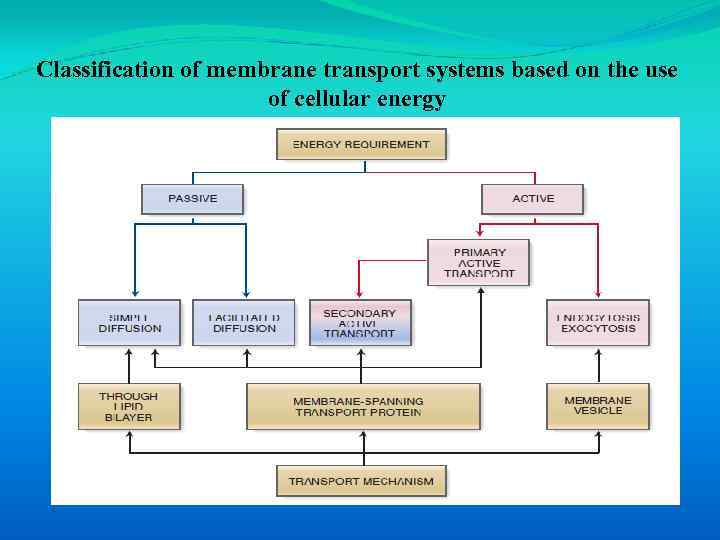

Classification of membrane transport systems based on the use of cellular energy

Classification of membrane transport systems based on the use of cellular energy

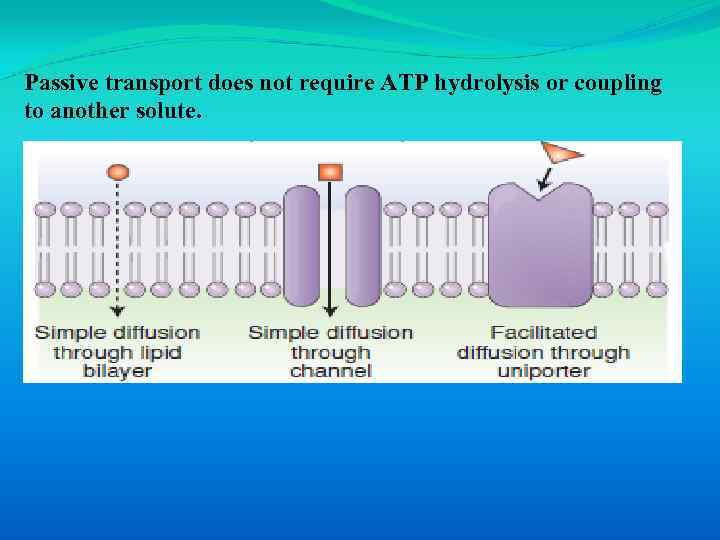

Passive transport does not require ATP hydrolysis or coupling to another solute.

Passive transport does not require ATP hydrolysis or coupling to another solute.

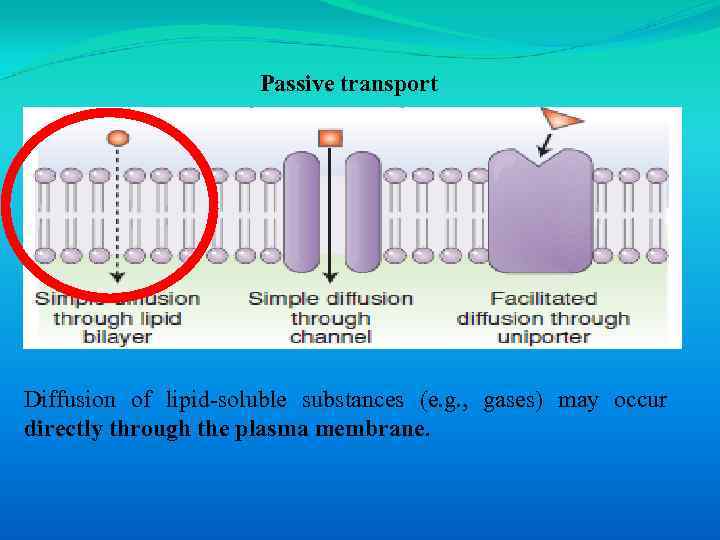

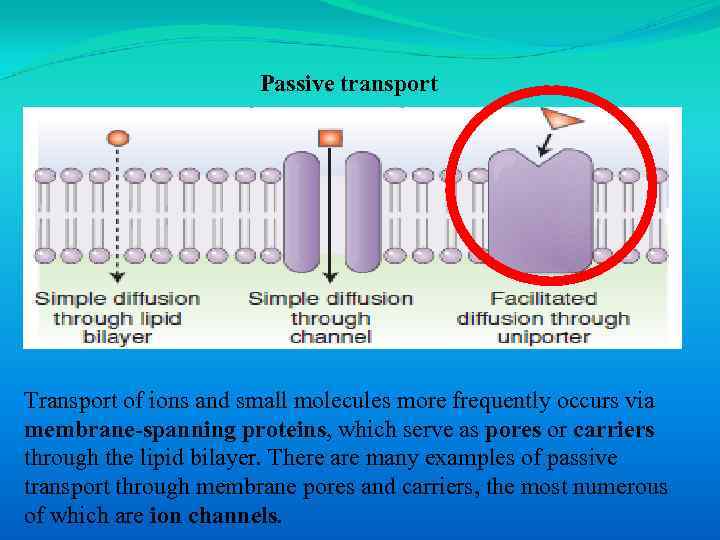

Passive transport Diffusion of lipid-soluble substances (e. g. , gases) may occur directly through the plasma membrane.

Passive transport Diffusion of lipid-soluble substances (e. g. , gases) may occur directly through the plasma membrane.

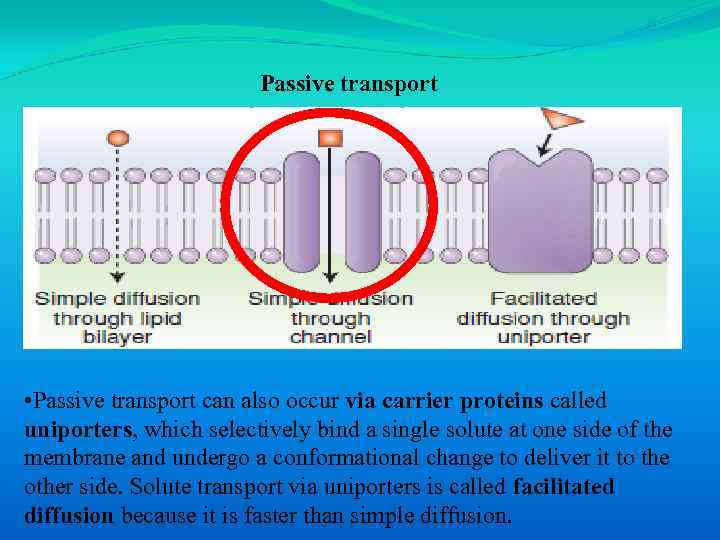

Passive transport • Passive transport can also occur via carrier proteins called uniporters, which selectively bind a single solute at one side of the membrane and undergo a conformational change to deliver it to the other side. Solute transport via uniporters is called facilitated diffusion because it is faster than simple diffusion.

Passive transport • Passive transport can also occur via carrier proteins called uniporters, which selectively bind a single solute at one side of the membrane and undergo a conformational change to deliver it to the other side. Solute transport via uniporters is called facilitated diffusion because it is faster than simple diffusion.

Passive transport Transport of ions and small molecules more frequently occurs via membrane-spanning proteins, which serve as pores or carriers through the lipid bilayer. There are many examples of passive transport through membrane pores and carriers, the most numerous of which are ion channels.

Passive transport Transport of ions and small molecules more frequently occurs via membrane-spanning proteins, which serve as pores or carriers through the lipid bilayer. There are many examples of passive transport through membrane pores and carriers, the most numerous of which are ion channels.

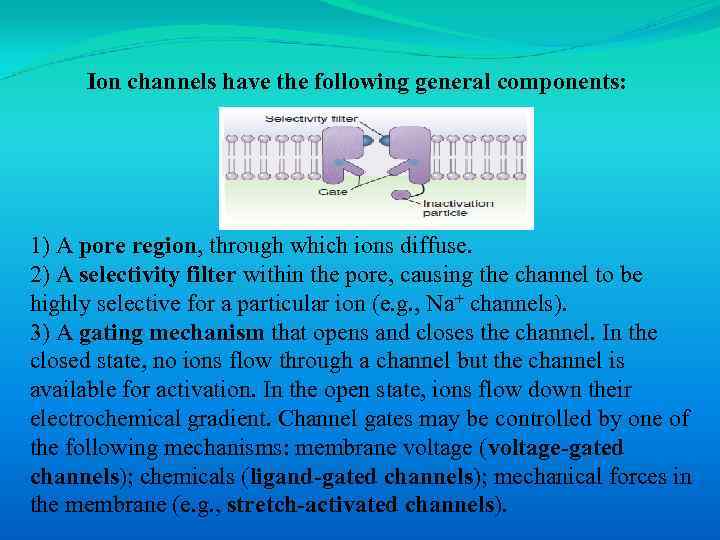

Ion channels have the following general components: 1) A pore region, through which ions diffuse. 2) A selectivity filter within the pore, causing the channel to be highly selective for a particular ion (e. g. , Na+ channels). 3) A gating mechanism that opens and closes the channel. In the closed state, no ions flow through a channel but the channel is available for activation. In the open state, ions flow down their electrochemical gradient. Channel gates may be controlled by one of the following mechanisms: membrane voltage (voltage-gated channels); chemicals (ligand-gated channels); mechanical forces in the membrane (e. g. , stretch-activated channels).

Ion channels have the following general components: 1) A pore region, through which ions diffuse. 2) A selectivity filter within the pore, causing the channel to be highly selective for a particular ion (e. g. , Na+ channels). 3) A gating mechanism that opens and closes the channel. In the closed state, no ions flow through a channel but the channel is available for activation. In the open state, ions flow down their electrochemical gradient. Channel gates may be controlled by one of the following mechanisms: membrane voltage (voltage-gated channels); chemicals (ligand-gated channels); mechanical forces in the membrane (e. g. , stretch-activated channels).

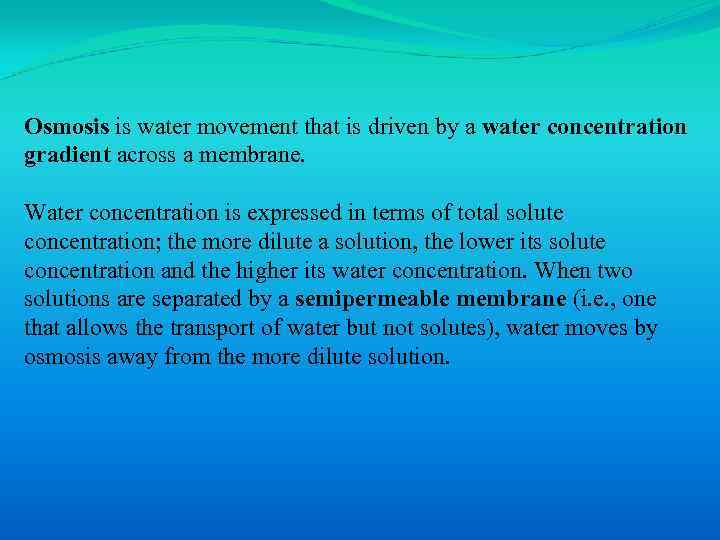

Osmosis is water movement that is driven by a water concentration gradient across a membrane. Water concentration is expressed in terms of total solute concentration; the more dilute a solution, the lower its solute concentration and the higher its water concentration. When two solutions are separated by a semipermeable membrane (i. e. , one that allows the transport of water but not solutes), water moves by osmosis away from the more dilute solution.

Osmosis is water movement that is driven by a water concentration gradient across a membrane. Water concentration is expressed in terms of total solute concentration; the more dilute a solution, the lower its solute concentration and the higher its water concentration. When two solutions are separated by a semipermeable membrane (i. e. , one that allows the transport of water but not solutes), water moves by osmosis away from the more dilute solution.

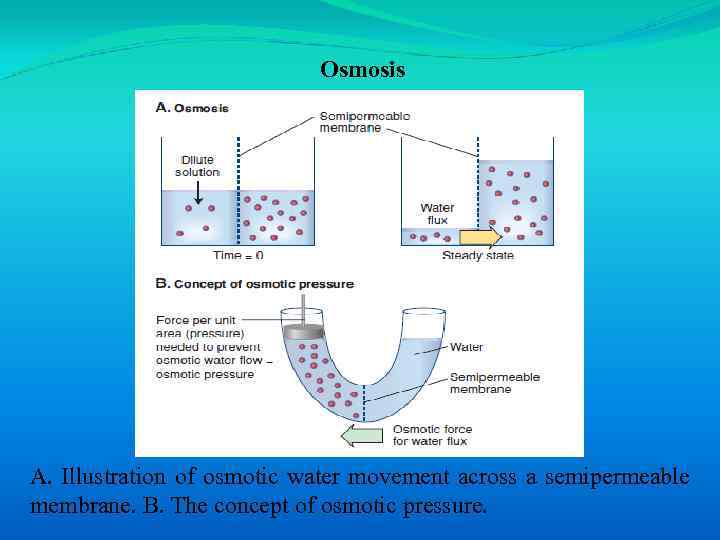

Osmosis A. Illustration of osmotic water movement across a semipermeable membrane. B. The concept of osmotic pressure.

Osmosis A. Illustration of osmotic water movement across a semipermeable membrane. B. The concept of osmotic pressure.

Osmolarity is an expression of the osmotic strength of a solution and is the total solute concentration. Two solutions of the same osmolarity are termed isosmotic. A solution with a greater osmolarity than a reference solution is said to be hyperosmotic, and a solution of lower osmolarity is described as hyposmotic.

Osmolarity is an expression of the osmotic strength of a solution and is the total solute concentration. Two solutions of the same osmolarity are termed isosmotic. A solution with a greater osmolarity than a reference solution is said to be hyperosmotic, and a solution of lower osmolarity is described as hyposmotic.

An isotonic solution has the some effective osmolarity as the cells and causes no net water movement; a hypotonic solution has a smaller effective osmolarity than the cells and causes cells to swell; a hypertonic solution has a larger effective osmolarity than the cells and causes cells to shrink. For example, if a patient is intravenously infused with a hypotonic solution, the ECF tonicity is initially decreased and water moves into the ICF by osmosis (cells swell). Conversely, if a hypertonic solution is infused, the ECF tonicity initially increases and water moves out of the ICF (cells shrink).

An isotonic solution has the some effective osmolarity as the cells and causes no net water movement; a hypotonic solution has a smaller effective osmolarity than the cells and causes cells to swell; a hypertonic solution has a larger effective osmolarity than the cells and causes cells to shrink. For example, if a patient is intravenously infused with a hypotonic solution, the ECF tonicity is initially decreased and water moves into the ICF by osmosis (cells swell). Conversely, if a hypertonic solution is infused, the ECF tonicity initially increases and water moves out of the ICF (cells shrink).

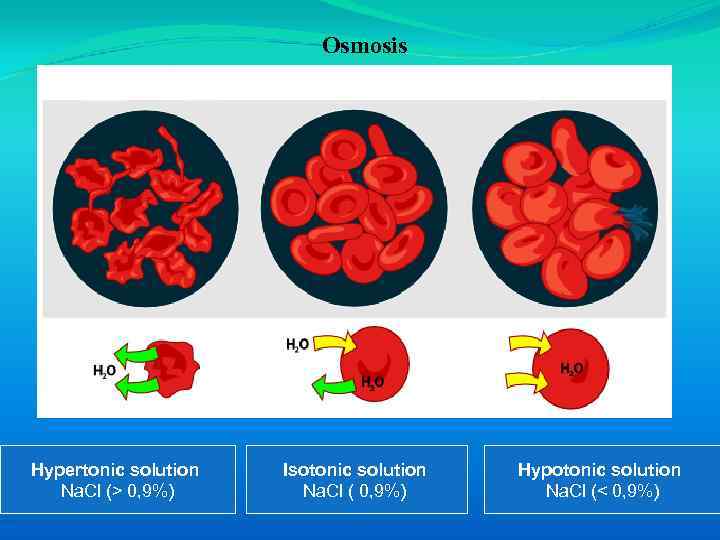

Osmosis Hypertonic solution Na. Cl (> 0, 9%) Isotonic solution Na. Cl ( 0, 9%) Hypotonic solution Na. Cl (< 0, 9%)

Osmosis Hypertonic solution Na. Cl (> 0, 9%) Isotonic solution Na. Cl ( 0, 9%) Hypotonic solution Na. Cl (< 0, 9%)

Active transport requires adenosine triphosphate (ATP) hydrolysis. There are three types of active transport : 1. Primary active transport 2. Secondary active transport 3. Vesicular transport

Active transport requires adenosine triphosphate (ATP) hydrolysis. There are three types of active transport : 1. Primary active transport 2. Secondary active transport 3. Vesicular transport

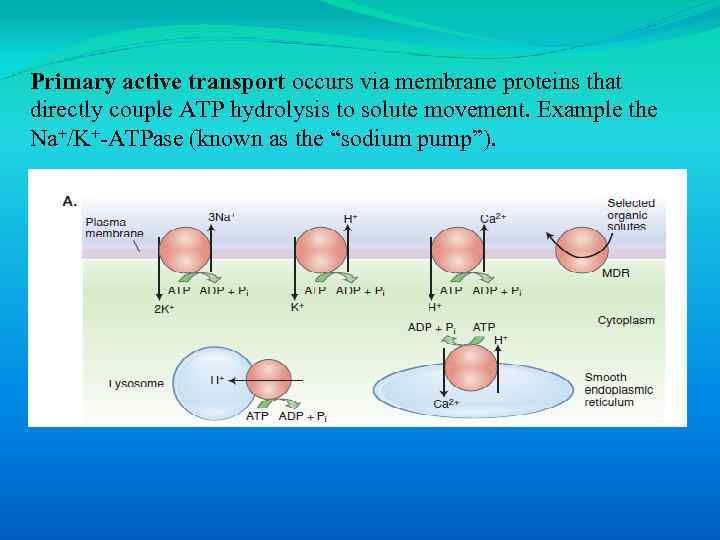

Primary active transport occurs via membrane proteins that directly couple ATP hydrolysis to solute movement. Example the Na+/K+-ATPase (known as the “sodium pump”).

Primary active transport occurs via membrane proteins that directly couple ATP hydrolysis to solute movement. Example the Na+/K+-ATPase (known as the “sodium pump”).

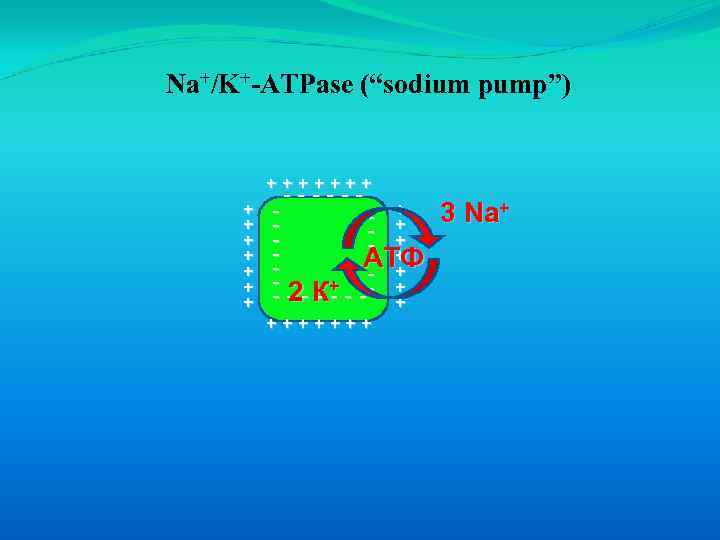

Na+/K+-ATPase (“sodium pump”) +++++++ + + + ------ - + 3 Na+ - + - + АТФ - 2 К+ - - - - -- + + +++++++

Na+/K+-ATPase (“sodium pump”) +++++++ + + + ------ - + 3 Na+ - + - + АТФ - 2 К+ - - - - -- + + +++++++

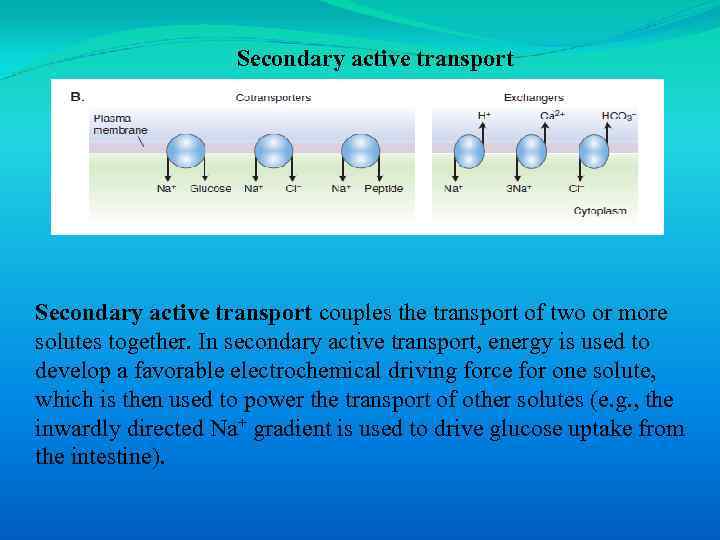

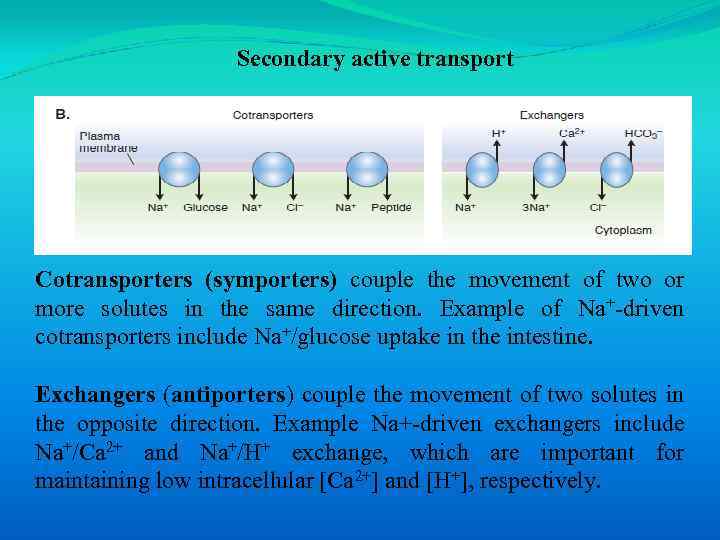

Secondary active transport couples the transport of two or more solutes together. In secondary active transport, energy is used to develop a favorable electrochemical driving force for one solute, which is then used to power the transport of other solutes (e. g. , the inwardly directed Na+ gradient is used to drive glucose uptake from the intestine).

Secondary active transport couples the transport of two or more solutes together. In secondary active transport, energy is used to develop a favorable electrochemical driving force for one solute, which is then used to power the transport of other solutes (e. g. , the inwardly directed Na+ gradient is used to drive glucose uptake from the intestine).

Secondary active transport Cotransporters (symporters) couple the movement of two or more solutes in the same direction. Example of Na+-driven cotransporters include Na+/glucose uptake in the intestine. Exchangers (antiporters) couple the movement of two solutes in the opposite direction. Example Na+-driven exchangers include Na+/Ca 2+ and Na+/H+ exchange, which are important for maintaining low intracellular [Ca 2+] and [H+], respectively.

Secondary active transport Cotransporters (symporters) couple the movement of two or more solutes in the same direction. Example of Na+-driven cotransporters include Na+/glucose uptake in the intestine. Exchangers (antiporters) couple the movement of two solutes in the opposite direction. Example Na+-driven exchangers include Na+/Ca 2+ and Na+/H+ exchange, which are important for maintaining low intracellular [Ca 2+] and [H+], respectively.

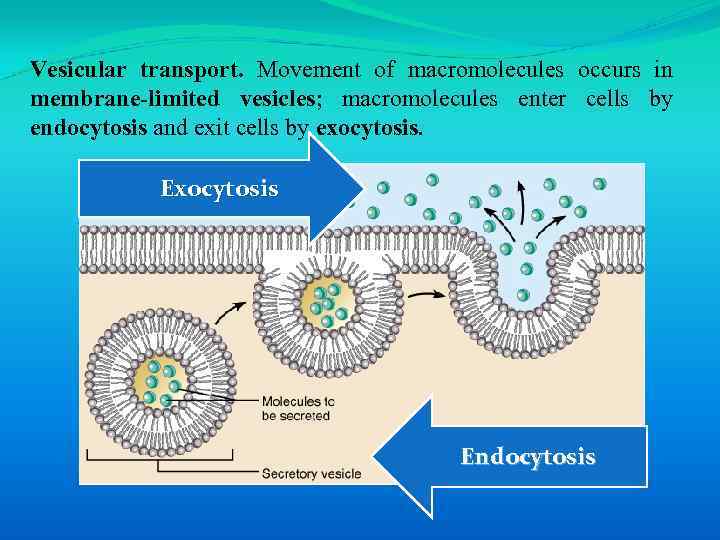

Vesicular transport. Movement of macromolecules occurs in membrane-limited vesicles; macromolecules enter cells by endocytosis and exit cells by exocytosis. Exocytosis Endocytosis

Vesicular transport. Movement of macromolecules occurs in membrane-limited vesicles; macromolecules enter cells by endocytosis and exit cells by exocytosis. Exocytosis Endocytosis

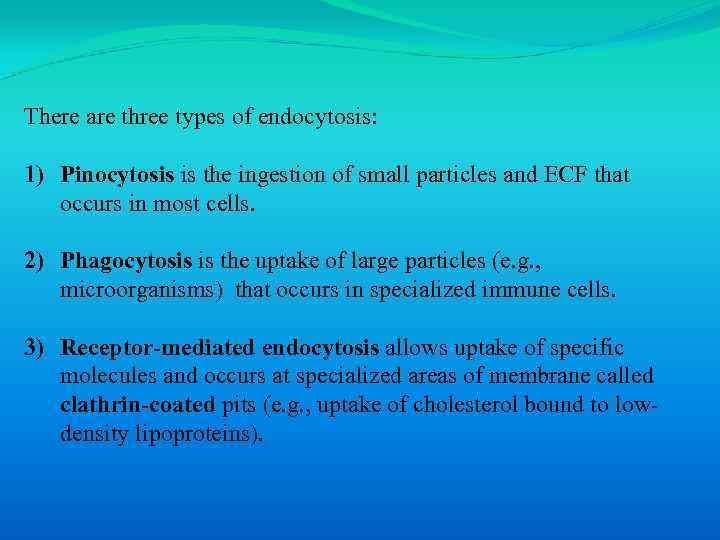

There are three types of endocytosis: 1) Pinocytosis is the ingestion of small particles and ECF that occurs in most cells. 2) Phagocytosis is the uptake of large particles (e. g. , microorganisms) that occurs in specialized immune cells. 3) Receptor-mediated endocytosis allows uptake of specific molecules and occurs at specialized areas of membrane called clathrin-coated pits (e. g. , uptake of cholesterol bound to lowdensity lipoproteins).

There are three types of endocytosis: 1) Pinocytosis is the ingestion of small particles and ECF that occurs in most cells. 2) Phagocytosis is the uptake of large particles (e. g. , microorganisms) that occurs in specialized immune cells. 3) Receptor-mediated endocytosis allows uptake of specific molecules and occurs at specialized areas of membrane called clathrin-coated pits (e. g. , uptake of cholesterol bound to lowdensity lipoproteins).

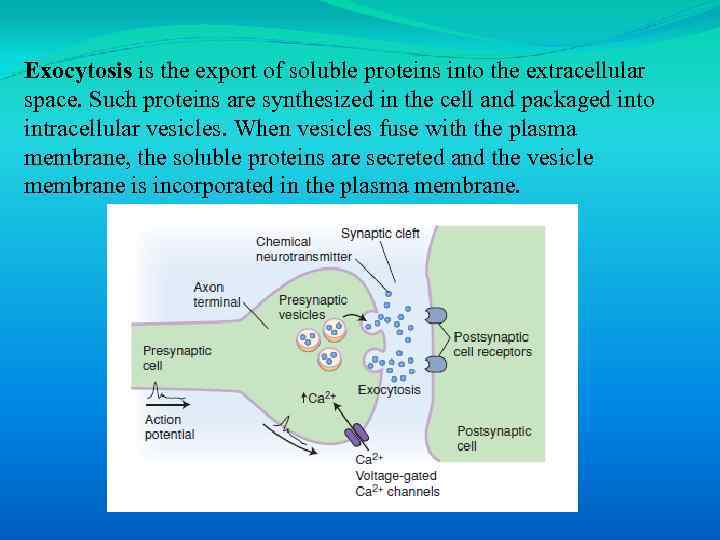

Exocytosis is the export of soluble proteins into the extracellular space. Such proteins are synthesized in the cell and packaged into intracellular vesicles. When vesicles fuse with the plasma membrane, the soluble proteins are secreted and the vesicle membrane is incorporated in the plasma membrane.

Exocytosis is the export of soluble proteins into the extracellular space. Such proteins are synthesized in the cell and packaged into intracellular vesicles. When vesicles fuse with the plasma membrane, the soluble proteins are secreted and the vesicle membrane is incorporated in the plasma membrane.

1. 4. Membrane potentials

1. 4. Membrane potentials

Ionic gradients are responsible for the generation of a resting membrane potential of cells in which the inside of the cell is electrically negative with respect to the outside

Ionic gradients are responsible for the generation of a resting membrane potential of cells in which the inside of the cell is electrically negative with respect to the outside

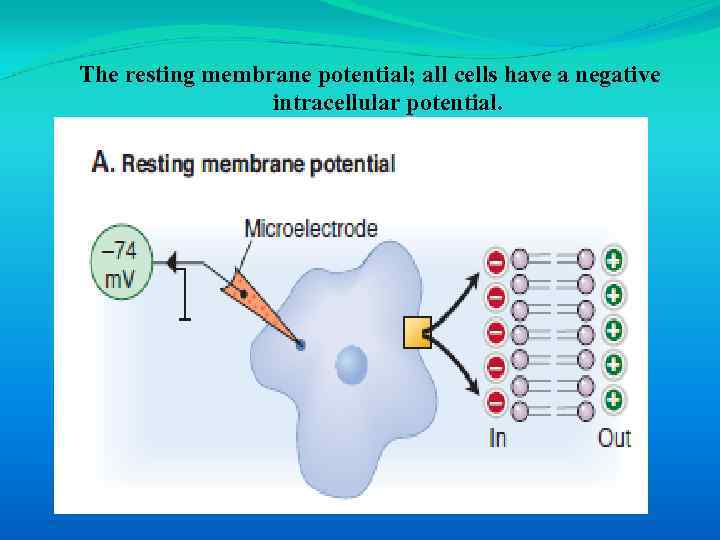

The resting membrane potential; all cells have a negative intracellular potential.

The resting membrane potential; all cells have a negative intracellular potential.

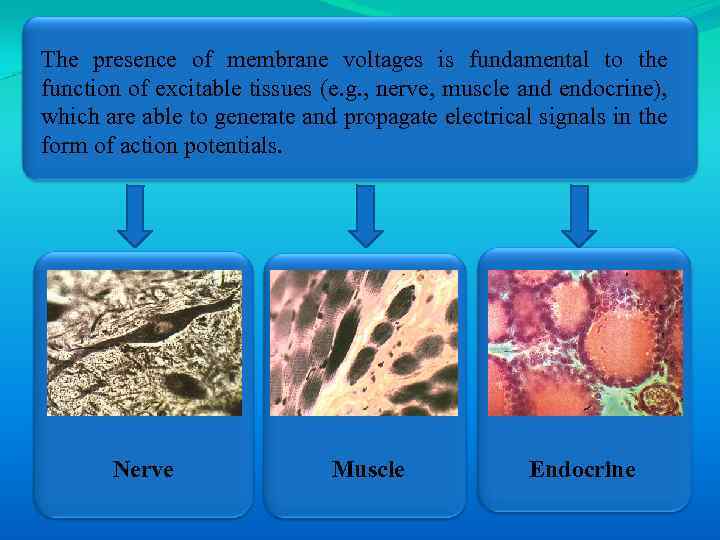

The presence of membrane voltages is fundamental to the function of excitable tissues (e. g. , nerve, muscle and endocrine), which are able to generate and propagate electrical signals in the form of action potentials. Nerve Muscle Endocrine

The presence of membrane voltages is fundamental to the function of excitable tissues (e. g. , nerve, muscle and endocrine), which are able to generate and propagate electrical signals in the form of action potentials. Nerve Muscle Endocrine

1. 4. 1. Ionic basis of membrane potentials

1. 4. 1. Ionic basis of membrane potentials

Membrane potentials arise because cell membranes contain ion channels that provide selective ion permeability and because there are stable ion diffusion gradients across the membrane.

Membrane potentials arise because cell membranes contain ion channels that provide selective ion permeability and because there are stable ion diffusion gradients across the membrane.

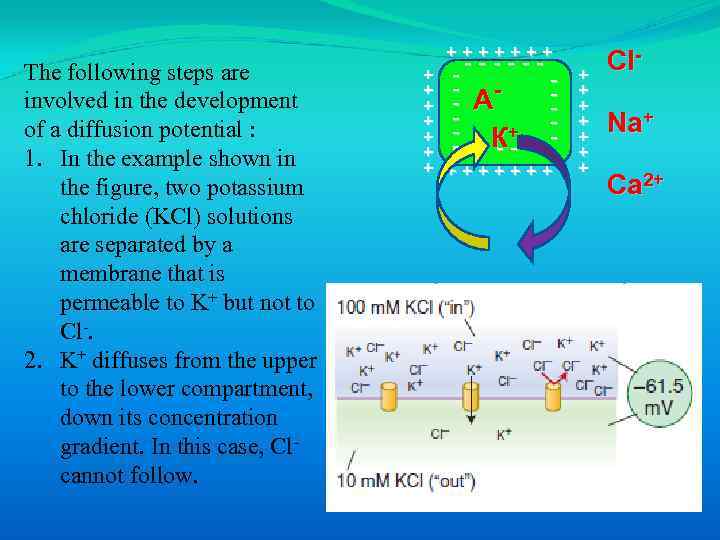

The following steps are involved in the development of a diffusion potential : 1. In the example shown in the figure, two potassium chloride (KCl) solutions are separated by a membrane that is permeable to K+ but not to Cl-. 2. K+ diffuses from the upper to the lower compartment, down its concentration gradient. In this case, Clcannot follow. +++++++ ------ - А - К+ - - - -- + + + +++++++ + + + Cl. Na+ Ca 2+

The following steps are involved in the development of a diffusion potential : 1. In the example shown in the figure, two potassium chloride (KCl) solutions are separated by a membrane that is permeable to K+ but not to Cl-. 2. K+ diffuses from the upper to the lower compartment, down its concentration gradient. In this case, Clcannot follow. +++++++ ------ - А - К+ - - - -- + + + +++++++ + + + Cl. Na+ Ca 2+

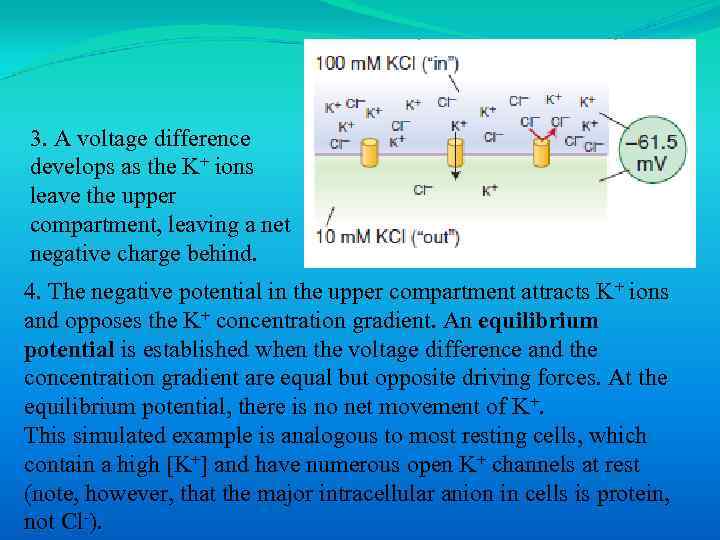

3. A voltage difference develops as the K+ ions leave the upper compartment, leaving a net negative charge behind. 4. The negative potential in the upper compartment attracts K+ ions and opposes the K+ concentration gradient. An equilibrium potential is established when the voltage difference and the concentration gradient are equal but opposite driving forces. At the equilibrium potential, there is no net movement of K+. This simulated example is analogous to most resting cells, which contain a high [K+] and have numerous open K+ channels at rest (note, however, that the major intracellular anion in cells is protein, not Cl-).

3. A voltage difference develops as the K+ ions leave the upper compartment, leaving a net negative charge behind. 4. The negative potential in the upper compartment attracts K+ ions and opposes the K+ concentration gradient. An equilibrium potential is established when the voltage difference and the concentration gradient are equal but opposite driving forces. At the equilibrium potential, there is no net movement of K+. This simulated example is analogous to most resting cells, which contain a high [K+] and have numerous open K+ channels at rest (note, however, that the major intracellular anion in cells is protein, not Cl-).

1. 4. 2. Resting membrane potential

1. 4. 2. Resting membrane potential

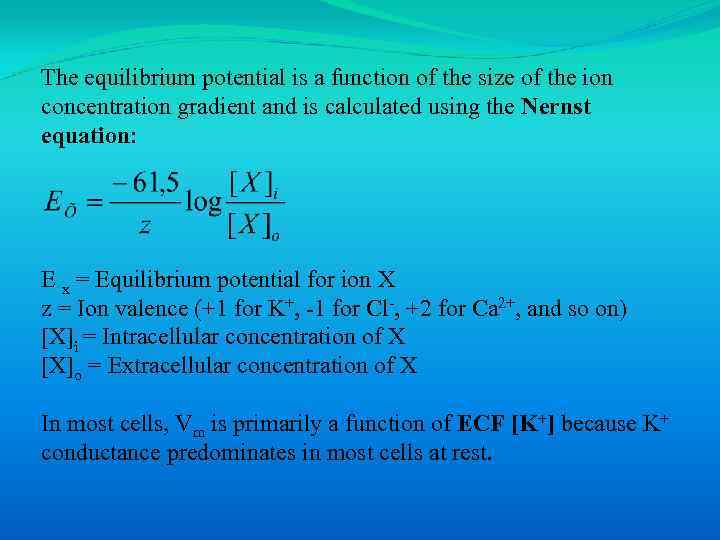

The equilibrium potential is a function of the size of the ion concentration gradient and is calculated using the Nernst equation: E x = Equilibrium potential for ion Х z = Ion valence (+1 for K+, -1 for Cl-, +2 for Ca 2+, and so on) [X]i = Intracellular concentration of X [X]o = Extracellular concentration of X In most cells, Vm is primarily a function of ECF [K+] because K+ conductance predominates in most cells at rest.

The equilibrium potential is a function of the size of the ion concentration gradient and is calculated using the Nernst equation: E x = Equilibrium potential for ion Х z = Ion valence (+1 for K+, -1 for Cl-, +2 for Ca 2+, and so on) [X]i = Intracellular concentration of X [X]o = Extracellular concentration of X In most cells, Vm is primarily a function of ECF [K+] because K+ conductance predominates in most cells at rest.

The measured membrane potential (Vm) will usually be a composite of several diffusion potentials because the membrane is usually permeable to more than one ion.

The measured membrane potential (Vm) will usually be a composite of several diffusion potentials because the membrane is usually permeable to more than one ion.

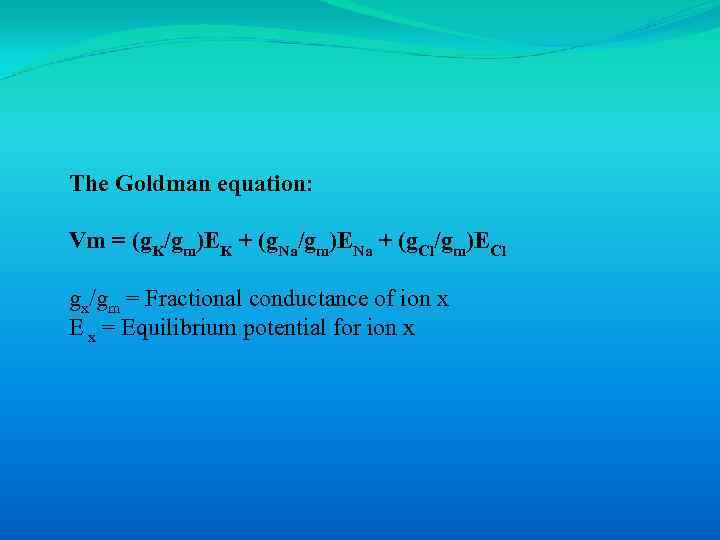

The Goldman equation: Vm = (g. K/gm)EK + (g. Na/gm)ENa + (g. Cl/gm)ECl gx/gm = Fractional conductance of ion x E x = Equilibrium potential for ion x

The Goldman equation: Vm = (g. K/gm)EK + (g. Na/gm)ENa + (g. Cl/gm)ECl gx/gm = Fractional conductance of ion x E x = Equilibrium potential for ion x

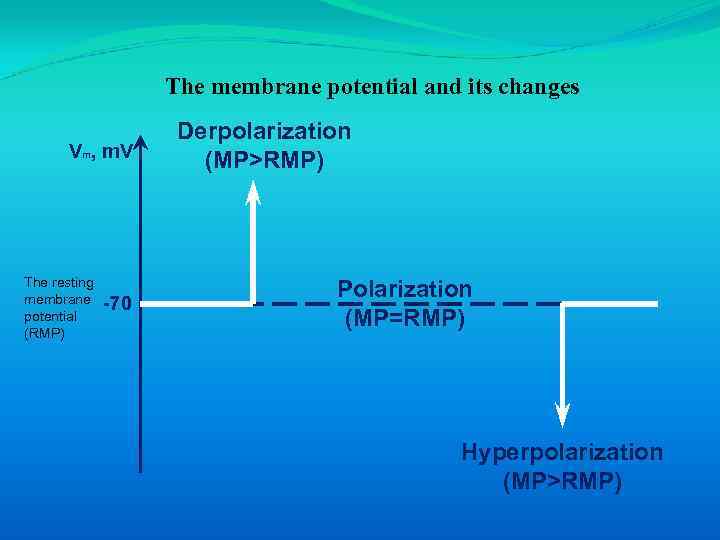

The membrane potential and its changes Vm, m. V The resting membrane potential (RMP) -70 Derpolarization (MP>RMP) Polarization (MP=RMP) Hyperpolarization (MP>RMP)

The membrane potential and its changes Vm, m. V The resting membrane potential (RMP) -70 Derpolarization (MP>RMP) Polarization (MP=RMP) Hyperpolarization (MP>RMP)

• Depolarization is a change to a less negative membrane potential (membrane potential difference is decreased). • Hyperpolarization occurs when the membrane potential becomes more negative (membrane potential difference is increased). Repolarization is the return of the membrane potential toward Vm following either depolarization or hyperpolarization.

• Depolarization is a change to a less negative membrane potential (membrane potential difference is decreased). • Hyperpolarization occurs when the membrane potential becomes more negative (membrane potential difference is increased). Repolarization is the return of the membrane potential toward Vm following either depolarization or hyperpolarization.

1. 5. Action potential 1. 6. Refractory periods

1. 5. Action potential 1. 6. Refractory periods

Excitable tissues (i. e. , neurons and muscle) are characterized by their ability to respond to a stimulus by rapidly generating and propagating electrical signals. The signal assumes the form of an action potential, which is a constant electrical signal that can be propagated over long distances without decay.

Excitable tissues (i. e. , neurons and muscle) are characterized by their ability to respond to a stimulus by rapidly generating and propagating electrical signals. The signal assumes the form of an action potential, which is a constant electrical signal that can be propagated over long distances without decay.

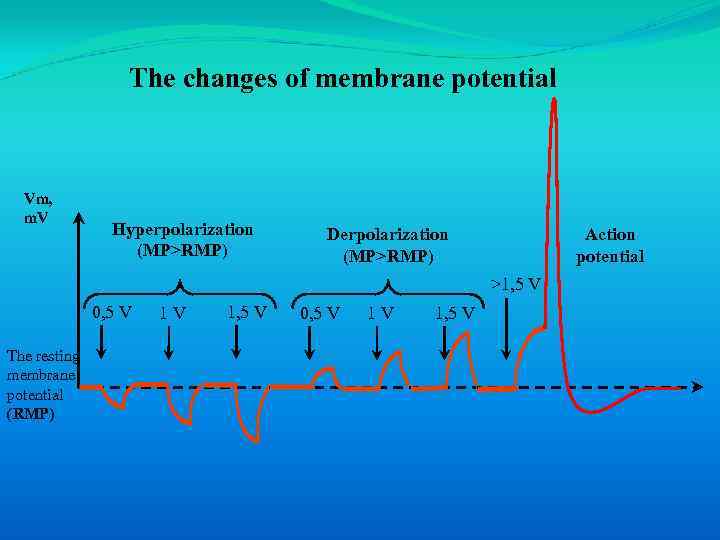

The changes of membrane potential Vm, m. V Hyperpolarization (MP>RMP) Derpolarization (MP>RMP) Action potential >1, 5 V 0, 5 V The resting membrane potential (RMP) 1 V 1, 5 V 0, 5 V 1 V 1, 5 V

The changes of membrane potential Vm, m. V Hyperpolarization (MP>RMP) Derpolarization (MP>RMP) Action potential >1, 5 V 0, 5 V The resting membrane potential (RMP) 1 V 1, 5 V 0, 5 V 1 V 1, 5 V

An action potential is an all-or-none impulse that occurs when an excitable cell membrane is depolarized beyond a threshold voltage.

An action potential is an all-or-none impulse that occurs when an excitable cell membrane is depolarized beyond a threshold voltage.

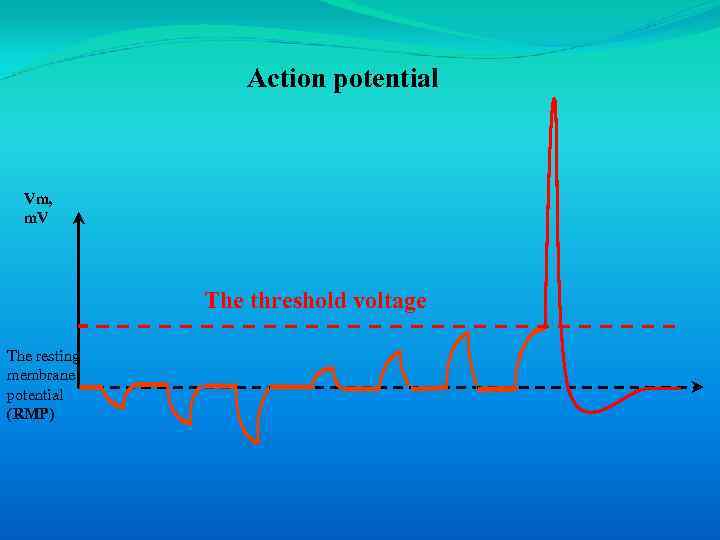

Action potential Vm, m. V The threshold voltage The resting membrane potential (RMP)

Action potential Vm, m. V The threshold voltage The resting membrane potential (RMP)

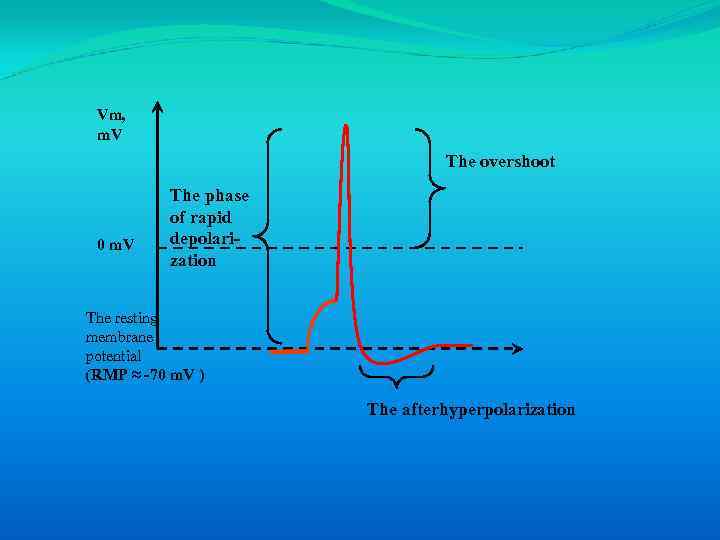

Vm, m. V The overshoot 0 m. V The phase of rapid depolarization The resting membrane potential (RMP ≈ -70 m. V ) The afterhyperpolarization

Vm, m. V The overshoot 0 m. V The phase of rapid depolarization The resting membrane potential (RMP ≈ -70 m. V ) The afterhyperpolarization

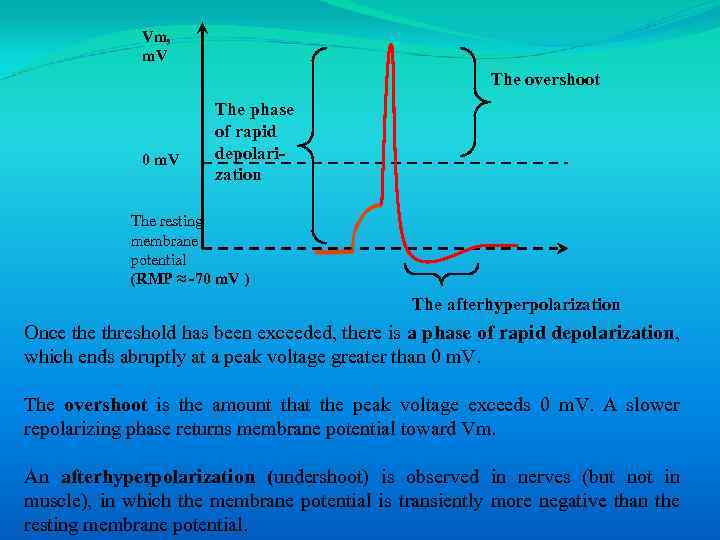

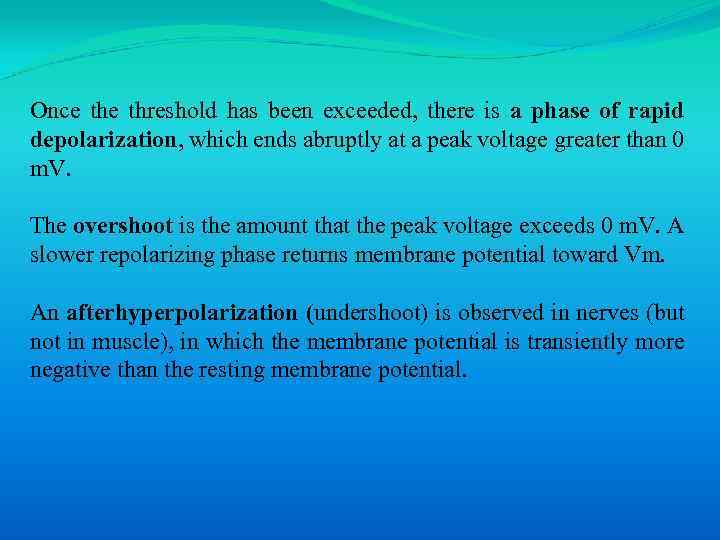

Vm, m. V The overshoot 0 m. V The phase of rapid depolarization The resting membrane potential (RMP ≈ -70 m. V ) The afterhyperpolarization Once threshold has been exceeded, there is a phase of rapid depolarization, which ends abruptly at a peak voltage greater than 0 m. V. The overshoot is the amount that the peak voltage exceeds 0 m. V. A slower repolarizing phase returns membrane potential toward Vm. An afterhyperpolarization (undershoot) is observed in nerves (but not in muscle), in which the membrane potential is transiently more negative than the resting membrane potential.

Vm, m. V The overshoot 0 m. V The phase of rapid depolarization The resting membrane potential (RMP ≈ -70 m. V ) The afterhyperpolarization Once threshold has been exceeded, there is a phase of rapid depolarization, which ends abruptly at a peak voltage greater than 0 m. V. The overshoot is the amount that the peak voltage exceeds 0 m. V. A slower repolarizing phase returns membrane potential toward Vm. An afterhyperpolarization (undershoot) is observed in nerves (but not in muscle), in which the membrane potential is transiently more negative than the resting membrane potential.

Once threshold has been exceeded, there is a phase of rapid depolarization, which ends abruptly at a peak voltage greater than 0 m. V. The overshoot is the amount that the peak voltage exceeds 0 m. V. A slower repolarizing phase returns membrane potential toward Vm. An afterhyperpolarization (undershoot) is observed in nerves (but not in muscle), in which the membrane potential is transiently more negative than the resting membrane potential.

Once threshold has been exceeded, there is a phase of rapid depolarization, which ends abruptly at a peak voltage greater than 0 m. V. The overshoot is the amount that the peak voltage exceeds 0 m. V. A slower repolarizing phase returns membrane potential toward Vm. An afterhyperpolarization (undershoot) is observed in nerves (but not in muscle), in which the membrane potential is transiently more negative than the resting membrane potential.

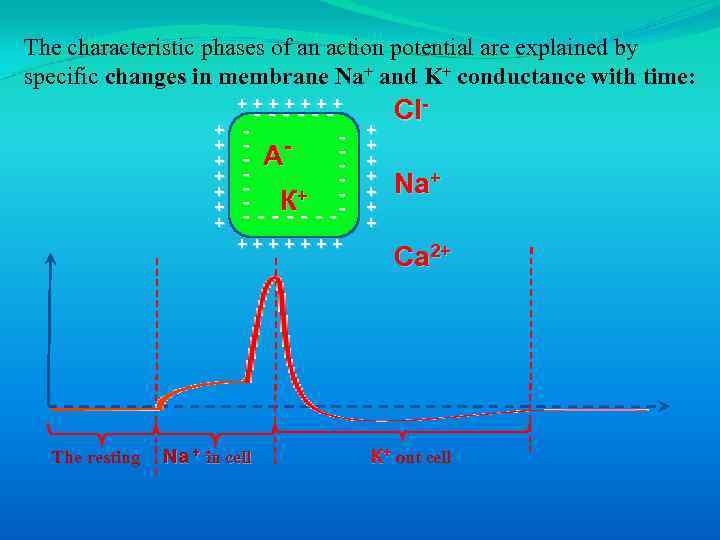

The characteristic phases of an action potential are explained by specific changes in membrane Na+ and K+ conductance with time: +++++++ + + + ------ - А - К+ - - - -- +++++++ The resting Na + in cell + + + + Cl. Na+ Ca 2+ К+ out cell

The characteristic phases of an action potential are explained by specific changes in membrane Na+ and K+ conductance with time: +++++++ + + + ------ - А - К+ - - - -- +++++++ The resting Na + in cell + + + + Cl. Na+ Ca 2+ К+ out cell

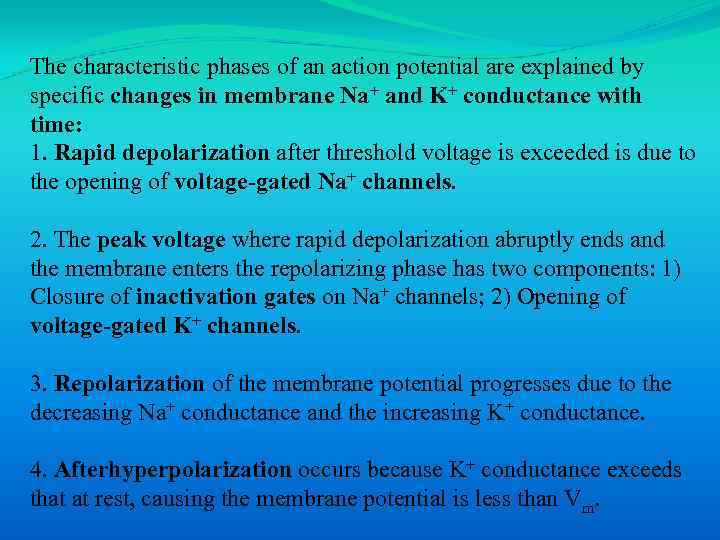

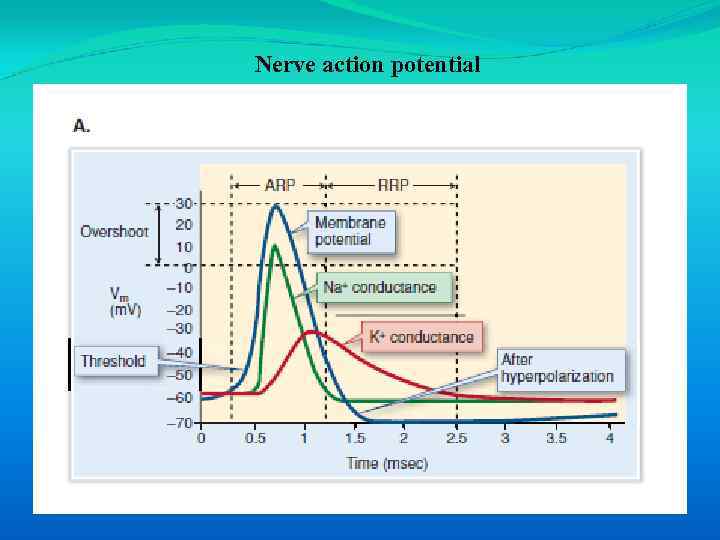

The characteristic phases of an action potential are explained by specific changes in membrane Na+ and K+ conductance with time: 1. Rapid depolarization after threshold voltage is exceeded is due to the opening of voltage-gated Na+ channels. 2. The peak voltage where rapid depolarization abruptly ends and the membrane enters the repolarizing phase has two components: 1) Closure of inactivation gates on Na+ channels; 2) Opening of voltage-gated K+ channels. 3. Repolarization of the membrane potential progresses due to the decreasing Na+ conductance and the increasing K+ conductance. 4. Afterhyperpolarization occurs because K+ conductance exceeds that at rest, causing the membrane potential is less than Vm.

The characteristic phases of an action potential are explained by specific changes in membrane Na+ and K+ conductance with time: 1. Rapid depolarization after threshold voltage is exceeded is due to the opening of voltage-gated Na+ channels. 2. The peak voltage where rapid depolarization abruptly ends and the membrane enters the repolarizing phase has two components: 1) Closure of inactivation gates on Na+ channels; 2) Opening of voltage-gated K+ channels. 3. Repolarization of the membrane potential progresses due to the decreasing Na+ conductance and the increasing K+ conductance. 4. Afterhyperpolarization occurs because K+ conductance exceeds that at rest, causing the membrane potential is less than Vm.

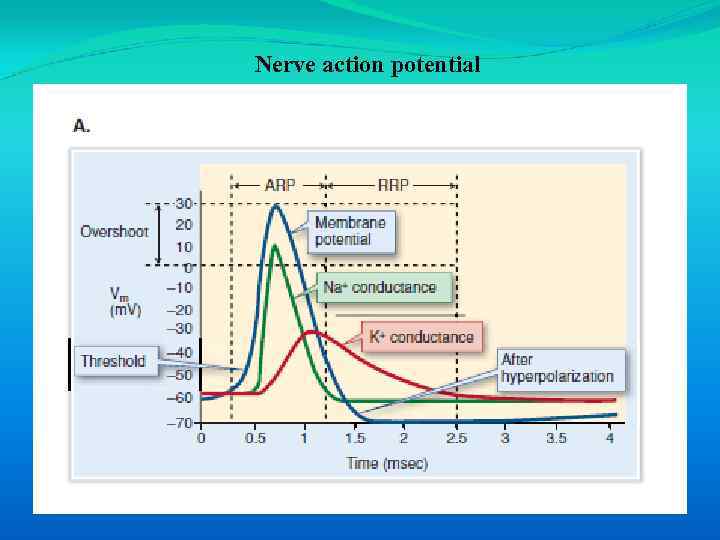

Nerve action potential

Nerve action potential

1. 6. Refractory periods

1. 6. Refractory periods

In the nervous system, it is necessary to encode the intensity of a stimulus rather than merely indicating whether or not a stimulus is present (e. g. , how loud is a sound? ). Because individual action potentials all have the same amplitude and action potentials never summate, the stimulus intensity must be encoded by action potential frequency. The maximum action potential frequency is limited because a finite period of time must elapse after one action potential before a second one can be triggered.

In the nervous system, it is necessary to encode the intensity of a stimulus rather than merely indicating whether or not a stimulus is present (e. g. , how loud is a sound? ). Because individual action potentials all have the same amplitude and action potentials never summate, the stimulus intensity must be encoded by action potential frequency. The maximum action potential frequency is limited because a finite period of time must elapse after one action potential before a second one can be triggered.

• The absolute refractory period (ARP) is the time from the beginning of one action potential when it is impossible to stimulate another action potential. The absolute refractory period results from closure of inactivation gates in Na+ channels. • The relative refractory period (RRP) is the time after the absolute refractory period when another impulse can be evoked, but only if a stronger stimulus is applied. A stronger stimulus is needed because a small number of Na+ channels have now recovered from inactivation and the membrane is less excitable due to high K+ conductance.

• The absolute refractory period (ARP) is the time from the beginning of one action potential when it is impossible to stimulate another action potential. The absolute refractory period results from closure of inactivation gates in Na+ channels. • The relative refractory period (RRP) is the time after the absolute refractory period when another impulse can be evoked, but only if a stronger stimulus is applied. A stronger stimulus is needed because a small number of Na+ channels have now recovered from inactivation and the membrane is less excitable due to high K+ conductance.

Nerve action potential

Nerve action potential

1. 7. Action potential propagation

1. 7. Action potential propagation

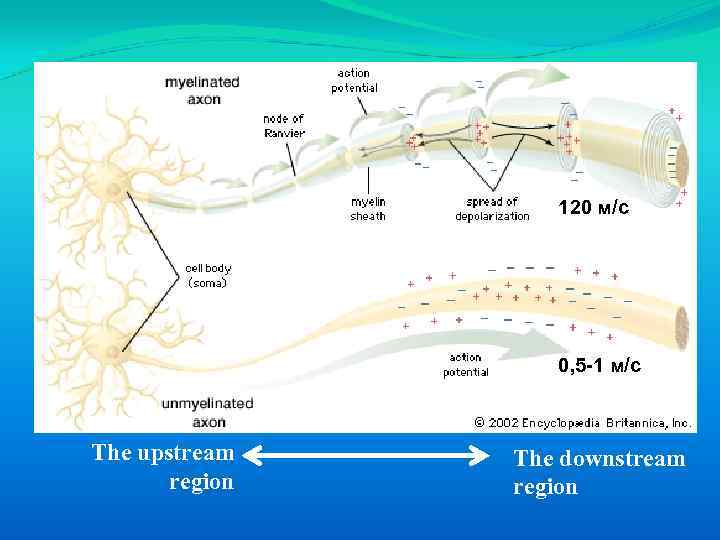

120 м/с 0, 5 -1 м/с The upstream region The downstream region

120 м/с 0, 5 -1 м/с The upstream region The downstream region

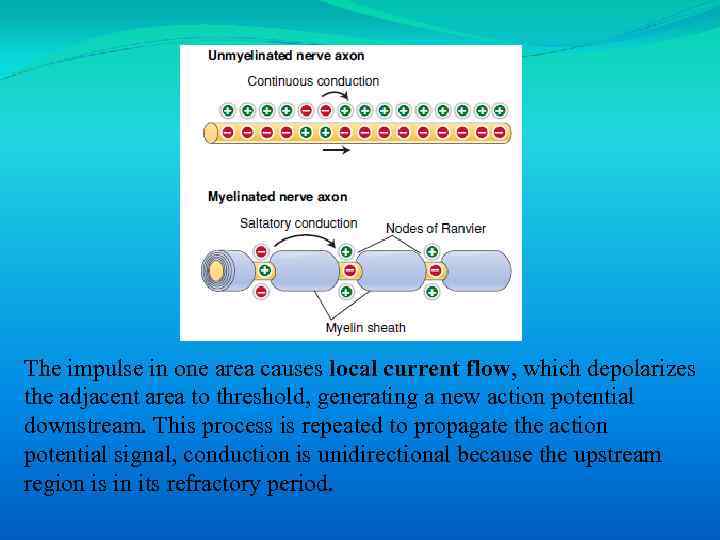

The impulse in one area causes local current flow, which depolarizes the adjacent area to threshold, generating a new action potential downstream. This process is repeated to propagate the action potential signal, conduction is unidirectional because the upstream region is in its refractory period.

The impulse in one area causes local current flow, which depolarizes the adjacent area to threshold, generating a new action potential downstream. This process is repeated to propagate the action potential signal, conduction is unidirectional because the upstream region is in its refractory period.

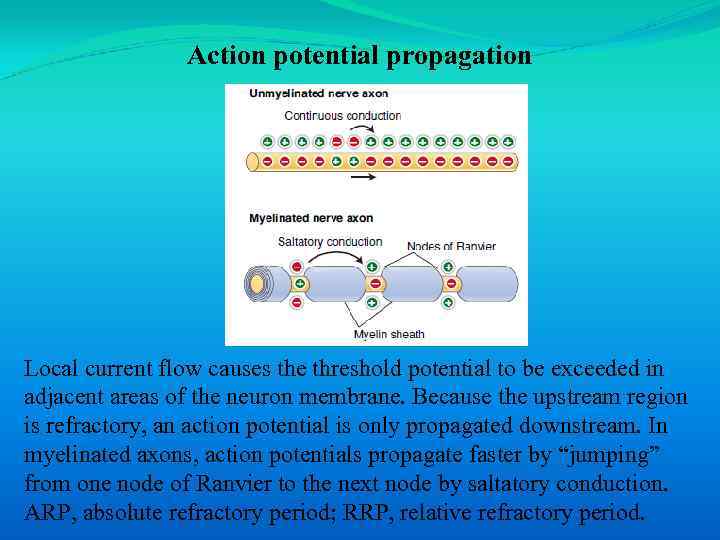

Action potential propagation Local current flow causes the threshold potential to be exceeded in adjacent areas of the neuron membrane. Because the upstream region is refractory, an action potential is only propagated downstream. In myelinated axons, action potentials propagate faster by “jumping” from one node of Ranvier to the next node by saltatory conduction. ARP, absolute refractory period; RRP, relative refractory period.

Action potential propagation Local current flow causes the threshold potential to be exceeded in adjacent areas of the neuron membrane. Because the upstream region is refractory, an action potential is only propagated downstream. In myelinated axons, action potentials propagate faster by “jumping” from one node of Ranvier to the next node by saltatory conduction. ARP, absolute refractory period; RRP, relative refractory period.

The speed of action potential conduction is faster in larger diameter fibers because they have lower electrical resistance than small diameter fibers. Conduction speed is also increased by the myelination of nerve axons. Myelin consists of glial cell plasma membrane, concentrically wrapped around the nerve. In the peripheral nerves, the myelin sheath is interrupted at regular intervals by uncovered nodes of Ranvier. Action potentials are propagated from node-to-node rather than conducting along the whole nerve membrane because voltage-gated Na+ channels are only expressed at nodes of Ranvier. This process call saltatory conduction

The speed of action potential conduction is faster in larger diameter fibers because they have lower electrical resistance than small diameter fibers. Conduction speed is also increased by the myelination of nerve axons. Myelin consists of glial cell plasma membrane, concentrically wrapped around the nerve. In the peripheral nerves, the myelin sheath is interrupted at regular intervals by uncovered nodes of Ranvier. Action potentials are propagated from node-to-node rather than conducting along the whole nerve membrane because voltage-gated Na+ channels are only expressed at nodes of Ranvier. This process call saltatory conduction

1. 8. Synaptic transmission

1. 8. Synaptic transmission

Synapses are specialized cell-to-cell contacts that allow the information encoded by action potentials to pass to another cell. Synapses occur at the junction between the processes of two neurons or between a neuron and an effector cell (e. g. , a muscle or gland).

Synapses are specialized cell-to-cell contacts that allow the information encoded by action potentials to pass to another cell. Synapses occur at the junction between the processes of two neurons or between a neuron and an effector cell (e. g. , a muscle or gland).

There are two types of synapses: 1. Electrical synapses. 2. Chemical synapses.

There are two types of synapses: 1. Electrical synapses. 2. Chemical synapses.

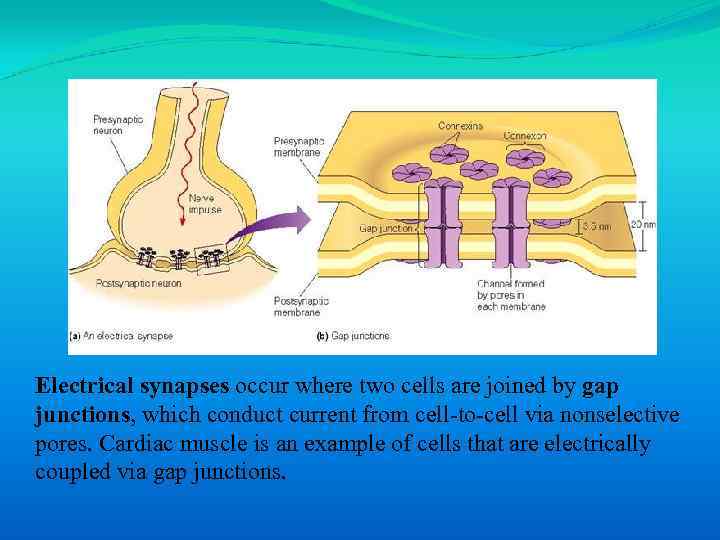

Electrical synapses occur where two cells are joined by gap junctions, which conduct current from cell-to-cell via nonselective pores. Cardiac muscle is an example of cells that are electrically coupled via gap junctions.

Electrical synapses occur where two cells are joined by gap junctions, which conduct current from cell-to-cell via nonselective pores. Cardiac muscle is an example of cells that are electrically coupled via gap junctions.

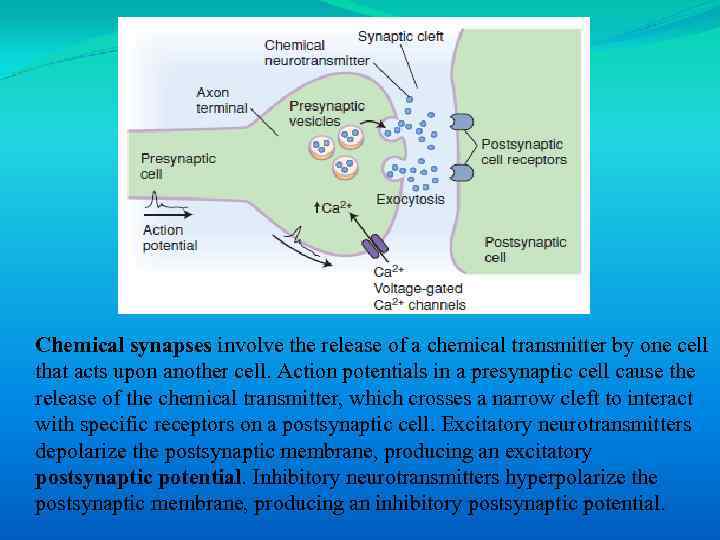

Chemical synapses involve the release of a chemical transmitter by one cell that acts upon another cell. Action potentials in a presynaptic cell cause the release of the chemical transmitter, which crosses a narrow cleft to interact with specific receptors on a postsynaptic cell. Excitatory neurotransmitters depolarize the postsynaptic membrane, producing an excitatory postsynaptic potential. Inhibitory neurotransmitters hyperpolarize the postsynaptic membrane, producing an inhibitory postsynaptic potential.

Chemical synapses involve the release of a chemical transmitter by one cell that acts upon another cell. Action potentials in a presynaptic cell cause the release of the chemical transmitter, which crosses a narrow cleft to interact with specific receptors on a postsynaptic cell. Excitatory neurotransmitters depolarize the postsynaptic membrane, producing an excitatory postsynaptic potential. Inhibitory neurotransmitters hyperpolarize the postsynaptic membrane, producing an inhibitory postsynaptic potential.

Chemical synapses have the following functional characteristics: • Presynaptic terminals contain neurotransmitter chemicals stored in vesicles. The amount of acetylcholine within a single presynaptic vesicle is called a quantum. Action potentials in a presynaptic terminal cause Ca 2+ entry through voltage-gated Ca 2+ channels, triggering the release of neurotransmitter by exocytosis. • There is always a delay between the arrival of an action potential in the presynaptic terminal and the onset of a response in the postsynaptic cell. • Transmitter action is rapidly terminated. One of three processes can remove transmitter molecules from the synaptic cleft: diffusion, enzymatic degradation by extracellular enzyme (in the case of acetylcholine), or uptake of transmitter into the nerve ending or other cell (usually most important).

Chemical synapses have the following functional characteristics: • Presynaptic terminals contain neurotransmitter chemicals stored in vesicles. The amount of acetylcholine within a single presynaptic vesicle is called a quantum. Action potentials in a presynaptic terminal cause Ca 2+ entry through voltage-gated Ca 2+ channels, triggering the release of neurotransmitter by exocytosis. • There is always a delay between the arrival of an action potential in the presynaptic terminal and the onset of a response in the postsynaptic cell. • Transmitter action is rapidly terminated. One of three processes can remove transmitter molecules from the synaptic cleft: diffusion, enzymatic degradation by extracellular enzyme (in the case of acetylcholine), or uptake of transmitter into the nerve ending or other cell (usually most important).

Neurotransmitter molecules interact with receptors on the postsynaptic cell membrane to induce either excitatory (depolarizing) or inhibitory (hyperpolarizing) postsynaptic potentials.

Neurotransmitter molecules interact with receptors on the postsynaptic cell membrane to induce either excitatory (depolarizing) or inhibitory (hyperpolarizing) postsynaptic potentials.

1. 9. Skeletal muscle

1. 9. Skeletal muscle

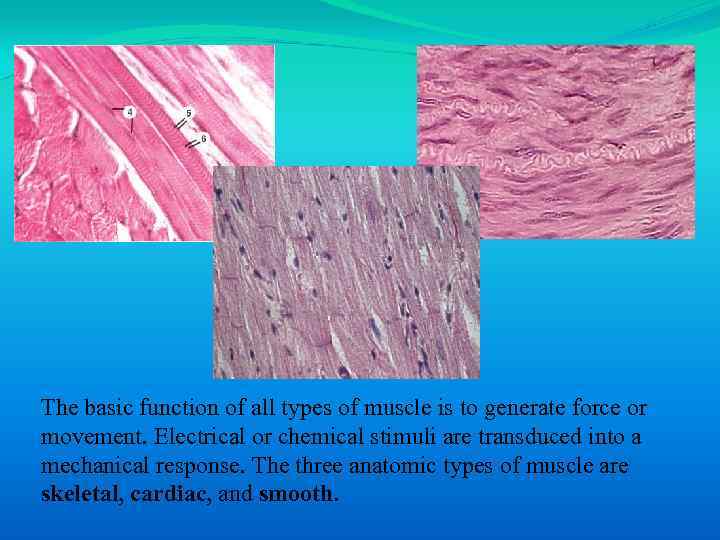

The basic function of all types of muscle is to generate force or movement. Electrical or chemical stimuli are transduced into a mechanical response. The three anatomic types of muscle are skeletal, cardiac, and smooth.

The basic function of all types of muscle is to generate force or movement. Electrical or chemical stimuli are transduced into a mechanical response. The three anatomic types of muscle are skeletal, cardiac, and smooth.

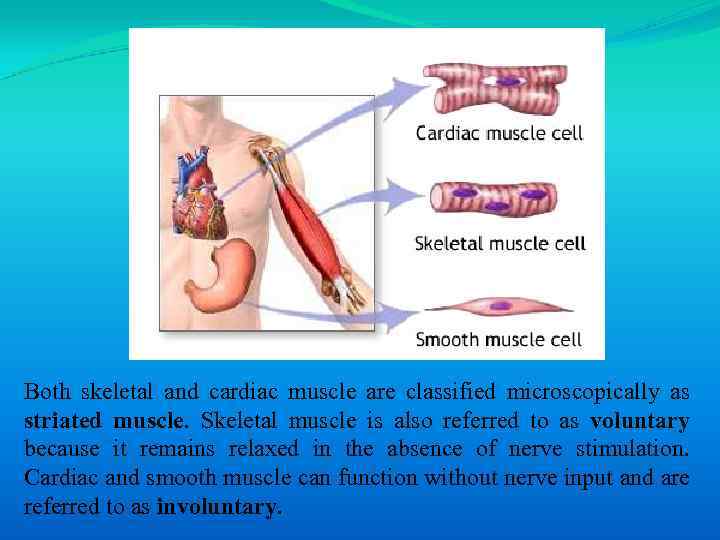

Both skeletal and cardiac muscle are classified microscopically as striated muscle. Skeletal muscle is also referred to as voluntary because it remains relaxed in the absence of nerve stimulation. Cardiac and smooth muscle can function without nerve input and are referred to as involuntary.

Both skeletal and cardiac muscle are classified microscopically as striated muscle. Skeletal muscle is also referred to as voluntary because it remains relaxed in the absence of nerve stimulation. Cardiac and smooth muscle can function without nerve input and are referred to as involuntary.

1. 9. 1. Neuromuscular junction

1. 9. 1. Neuromuscular junction

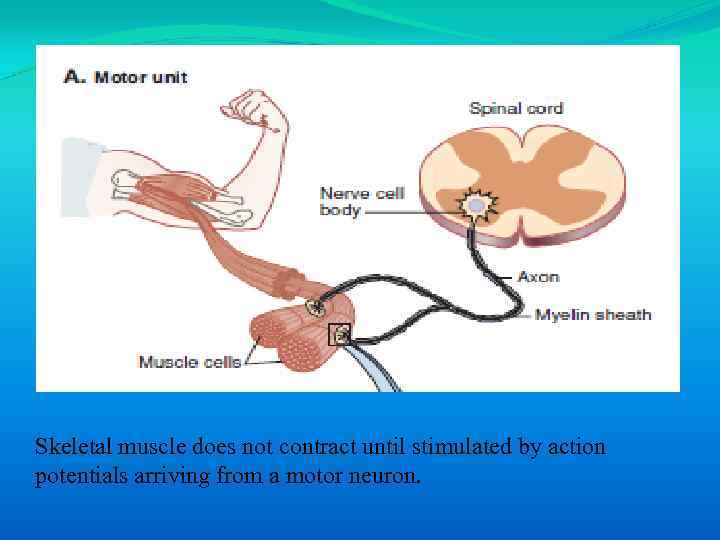

Skeletal muscle does not contract until stimulated by action potentials arriving from a motor neuron.

Skeletal muscle does not contract until stimulated by action potentials arriving from a motor neuron.

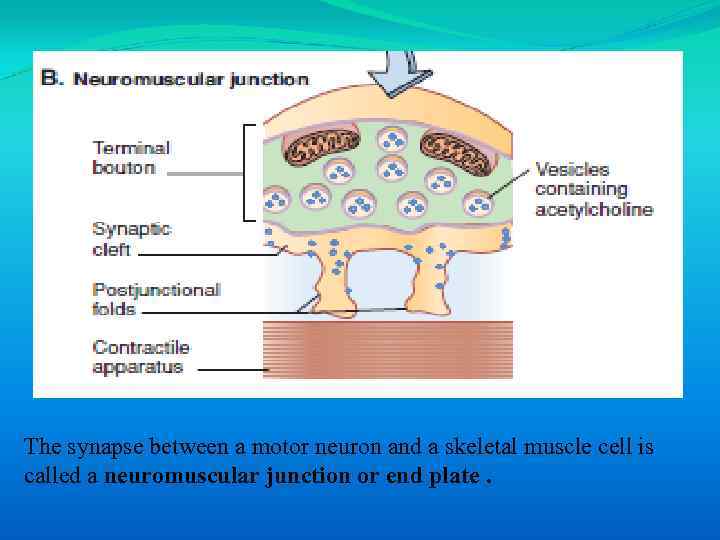

The synapse between a motor neuron and a skeletal muscle cell is called a neuromuscular junction or end plate.

The synapse between a motor neuron and a skeletal muscle cell is called a neuromuscular junction or end plate.

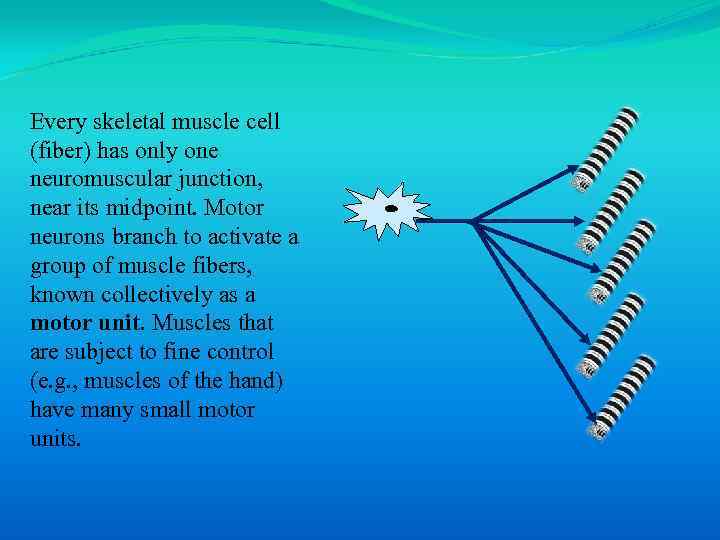

Every skeletal muscle cell (fiber) has only one neuromuscular junction, near its midpoint. Motor neurons branch to activate a group of muscle fibers, known collectively as a motor unit. Muscles that are subject to fine control (e. g. , muscles of the hand) have many small motor units.

Every skeletal muscle cell (fiber) has only one neuromuscular junction, near its midpoint. Motor neurons branch to activate a group of muscle fibers, known collectively as a motor unit. Muscles that are subject to fine control (e. g. , muscles of the hand) have many small motor units.

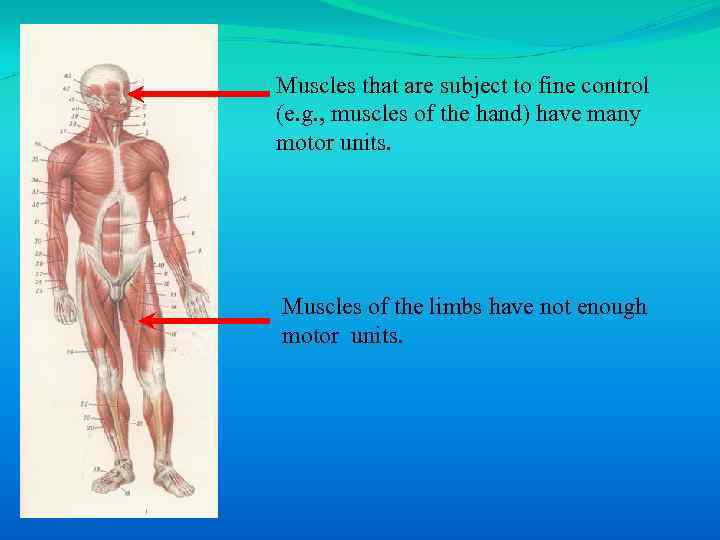

Muscles that are subject to fine control (e. g. , muscles of the hand) have many motor units. Muscles of the limbs have not enough motor units.

Muscles that are subject to fine control (e. g. , muscles of the hand) have many motor units. Muscles of the limbs have not enough motor units.

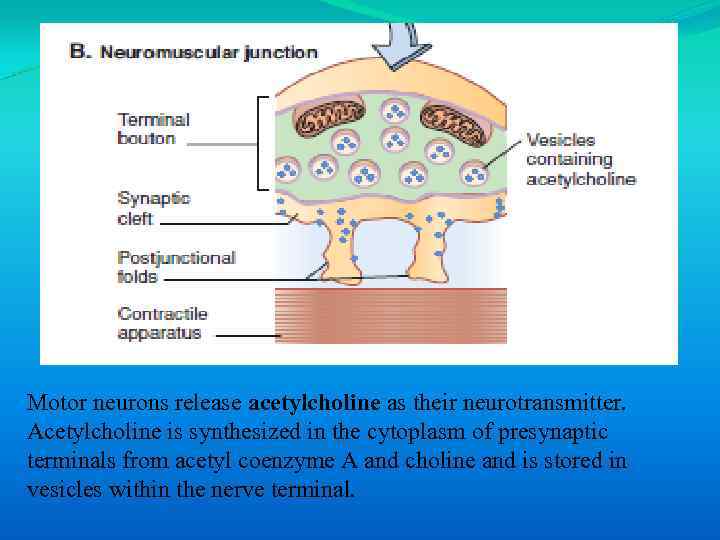

Motor neurons release acetylcholine as their neurotransmitter. Acetylcholine is synthesized in the cytoplasm of presynaptic terminals from acetyl coenzyme A and choline and is stored in vesicles within the nerve terminal.

Motor neurons release acetylcholine as their neurotransmitter. Acetylcholine is synthesized in the cytoplasm of presynaptic terminals from acetyl coenzyme A and choline and is stored in vesicles within the nerve terminal.

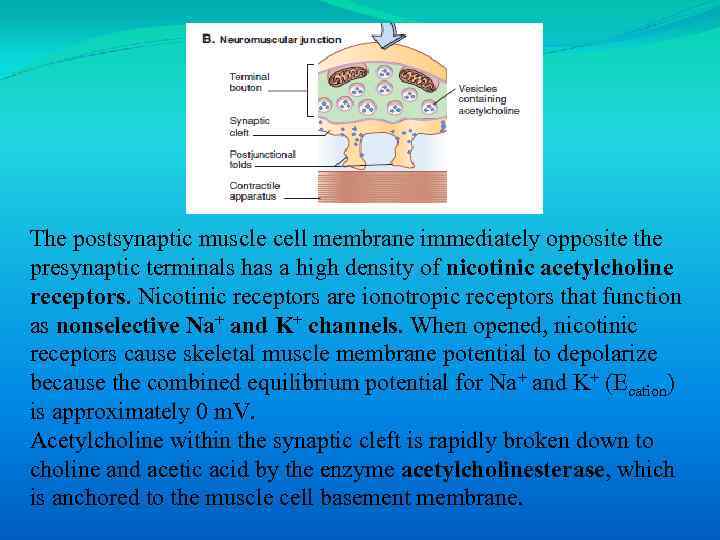

The postsynaptic muscle cell membrane immediately opposite the presynaptic terminals has a high density of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Nicotinic receptors are ionotropic receptors that function as nonselective Na+ and K+ channels. When opened, nicotinic receptors cause skeletal muscle membrane potential to depolarize because the combined equilibrium potential for Na+ and K+ (Ecation) is approximately 0 m. V. Acetylcholine within the synaptic cleft is rapidly broken down to choline and acetic acid by the enzyme acetylcholinesterase, which is anchored to the muscle cell basement membrane.

The postsynaptic muscle cell membrane immediately opposite the presynaptic terminals has a high density of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Nicotinic receptors are ionotropic receptors that function as nonselective Na+ and K+ channels. When opened, nicotinic receptors cause skeletal muscle membrane potential to depolarize because the combined equilibrium potential for Na+ and K+ (Ecation) is approximately 0 m. V. Acetylcholine within the synaptic cleft is rapidly broken down to choline and acetic acid by the enzyme acetylcholinesterase, which is anchored to the muscle cell basement membrane.

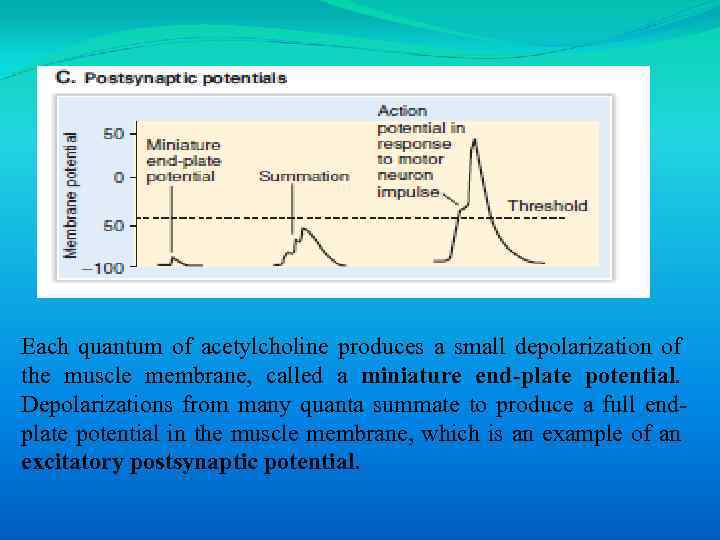

Each quantum of acetylcholine produces a small depolarization of the muscle membrane, called a miniature end-plate potential. Depolarizations from many quanta summate to produce a full endplate potential in the muscle membrane, which is an example of an excitatory postsynaptic potential.

Each quantum of acetylcholine produces a small depolarization of the muscle membrane, called a miniature end-plate potential. Depolarizations from many quanta summate to produce a full endplate potential in the muscle membrane, which is an example of an excitatory postsynaptic potential.

The generation of action potentials in the skeletal muscle cell membrane (sarcolemma) triggers a sequence of events that result in force development by the muscle. The unique ability of muscle to generate force when stimulated results from the presence of motor proteins inside muscle cells.

The generation of action potentials in the skeletal muscle cell membrane (sarcolemma) triggers a sequence of events that result in force development by the muscle. The unique ability of muscle to generate force when stimulated results from the presence of motor proteins inside muscle cells.

1. 9. 2. Sarcomeres

1. 9. 2. Sarcomeres

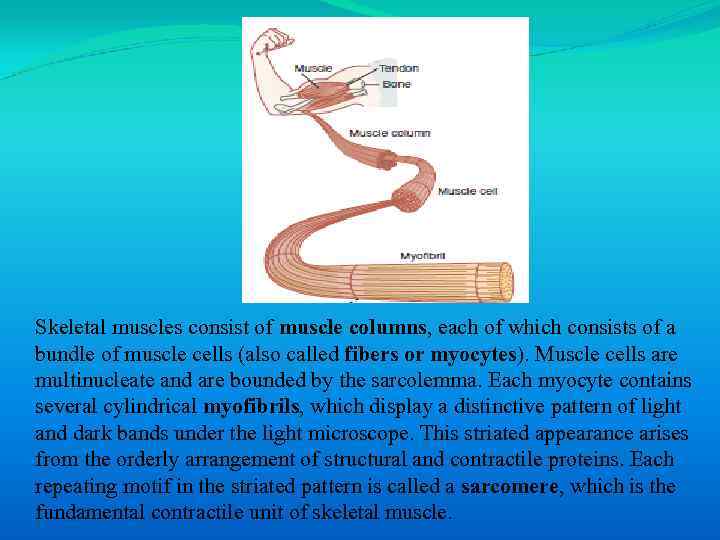

Skeletal muscles consist of muscle columns, each of which consists of a bundle of muscle cells (also called fibers or myocytes). Muscle cells are multinucleate and are bounded by the sarcolemma. Each myocyte contains several cylindrical myofibrils, which display a distinctive pattern of light and dark bands under the light microscope. This striated appearance arises from the orderly arrangement of structural and contractile proteins. Each repeating motif in the striated pattern is called a sarcomere, which is the fundamental contractile unit of skeletal muscle.

Skeletal muscles consist of muscle columns, each of which consists of a bundle of muscle cells (also called fibers or myocytes). Muscle cells are multinucleate and are bounded by the sarcolemma. Each myocyte contains several cylindrical myofibrils, which display a distinctive pattern of light and dark bands under the light microscope. This striated appearance arises from the orderly arrangement of structural and contractile proteins. Each repeating motif in the striated pattern is called a sarcomere, which is the fundamental contractile unit of skeletal muscle.

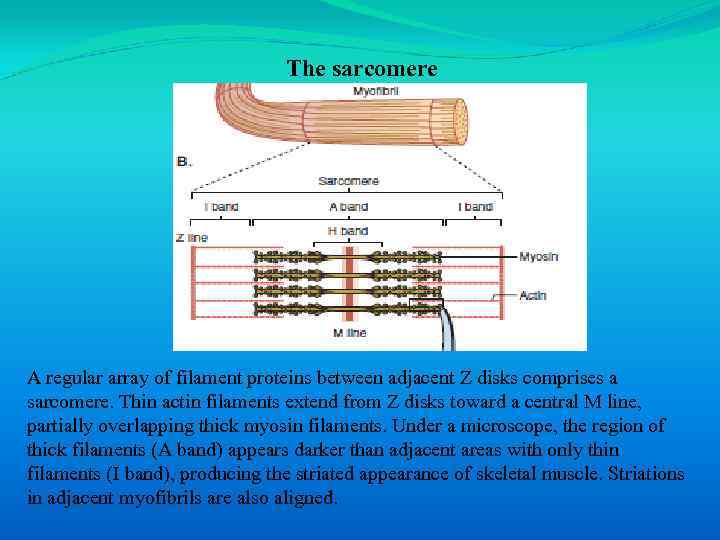

The sarcomere A regular array of filament proteins between adjacent Z disks comprises a sarcomere. Thin actin filaments extend from Z disks toward a central M line, partially overlapping thick myosin filaments. Under a microscope, the region of thick filaments (A band) appears darker than adjacent areas with only thin filaments (I band), producing the striated appearance of skeletal muscle. Striations in adjacent myofibrils are also aligned.

The sarcomere A regular array of filament proteins between adjacent Z disks comprises a sarcomere. Thin actin filaments extend from Z disks toward a central M line, partially overlapping thick myosin filaments. Under a microscope, the region of thick filaments (A band) appears darker than adjacent areas with only thin filaments (I band), producing the striated appearance of skeletal muscle. Striations in adjacent myofibrils are also aligned.

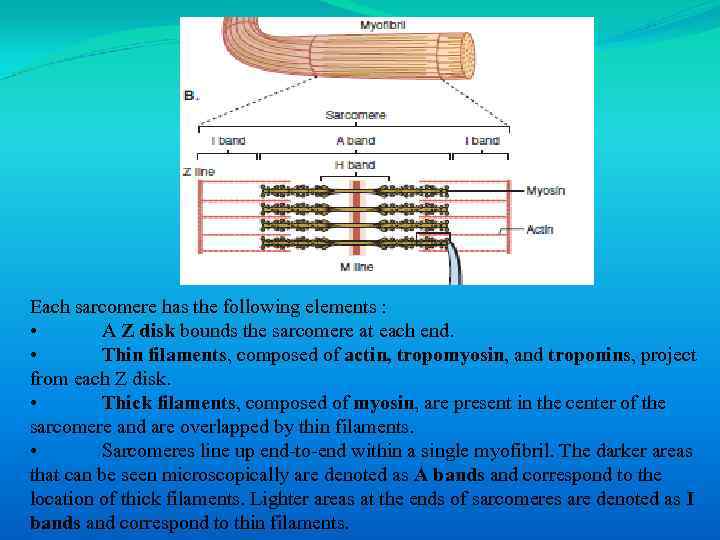

Each sarcomere has the following elements : • A Z disk bounds the sarcomere at each end. • Thin filaments, composed of actin, tropomyosin, and troponins, project from each Z disk. • Thick filaments, composed of myosin, are present in the center of the sarcomere and are overlapped by thin filaments. • Sarcomeres line up end-to-end within a single myofibril. The darker areas that can be seen microscopically are denoted as A bands and correspond to the location of thick filaments. Lighter areas at the ends of sarcomeres are denoted as I bands and correspond to thin filaments.

Each sarcomere has the following elements : • A Z disk bounds the sarcomere at each end. • Thin filaments, composed of actin, tropomyosin, and troponins, project from each Z disk. • Thick filaments, composed of myosin, are present in the center of the sarcomere and are overlapped by thin filaments. • Sarcomeres line up end-to-end within a single myofibril. The darker areas that can be seen microscopically are denoted as A bands and correspond to the location of thick filaments. Lighter areas at the ends of sarcomeres are denoted as I bands and correspond to thin filaments.

1. 9. 3. Molecular components of sarcomeres

1. 9. 3. Molecular components of sarcomeres

The orderly array of thin and thick myofilaments produces the characteristic striations of skeletal muscle. Thin filaments are composed of actin, with the associated proteins tropomyosin and troponins; thick filaments are composed of myosin.

The orderly array of thin and thick myofilaments produces the characteristic striations of skeletal muscle. Thin filaments are composed of actin, with the associated proteins tropomyosin and troponins; thick filaments are composed of myosin.

Thin filaments have three major components : 1. 2. 3.

Thin filaments have three major components : 1. 2. 3.

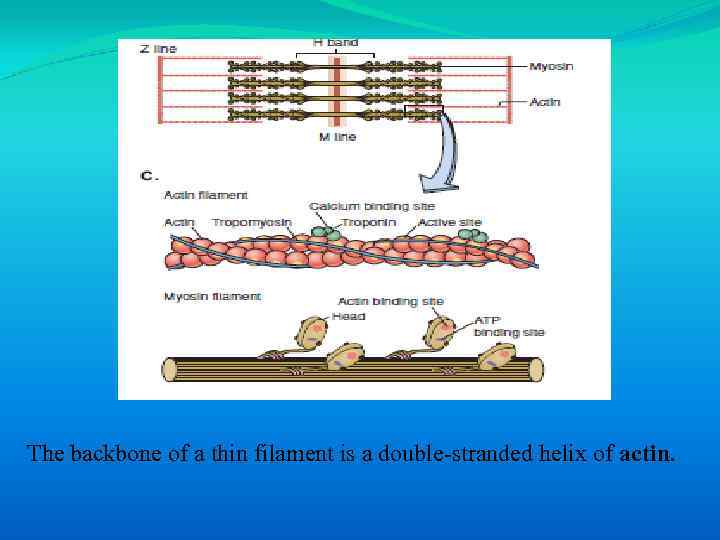

The backbone of a thin filament is a double-stranded helix of actin.

The backbone of a thin filament is a double-stranded helix of actin.

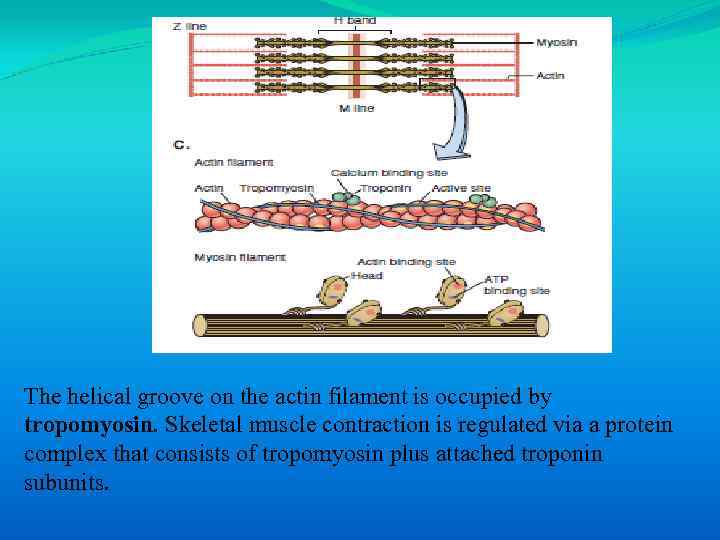

The helical groove on the actin filament is occupied by tropomyosin. Skeletal muscle contraction is regulated via a protein complex that consists of tropomyosin plus attached troponin subunits.

The helical groove on the actin filament is occupied by tropomyosin. Skeletal muscle contraction is regulated via a protein complex that consists of tropomyosin plus attached troponin subunits.

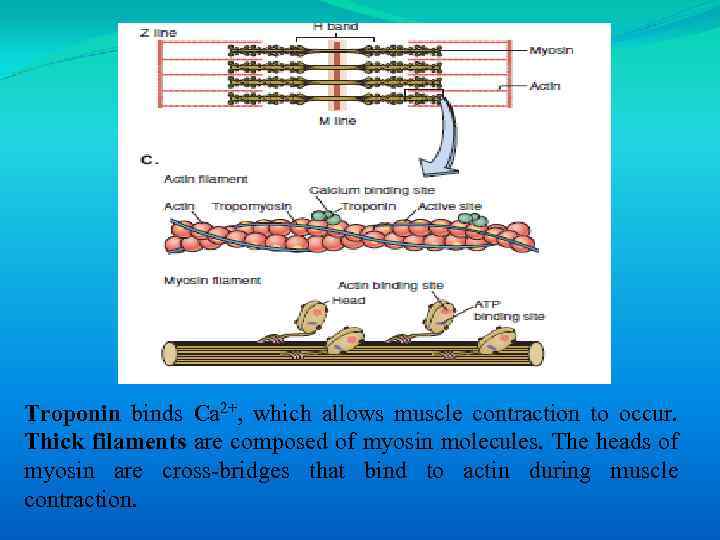

Troponin binds Ca 2+, which allows muscle contraction to occur. Thick filaments are composed of myosin molecules. The heads of myosin are cross-bridges that bind to actin during muscle contraction.

Troponin binds Ca 2+, which allows muscle contraction to occur. Thick filaments are composed of myosin molecules. The heads of myosin are cross-bridges that bind to actin during muscle contraction.

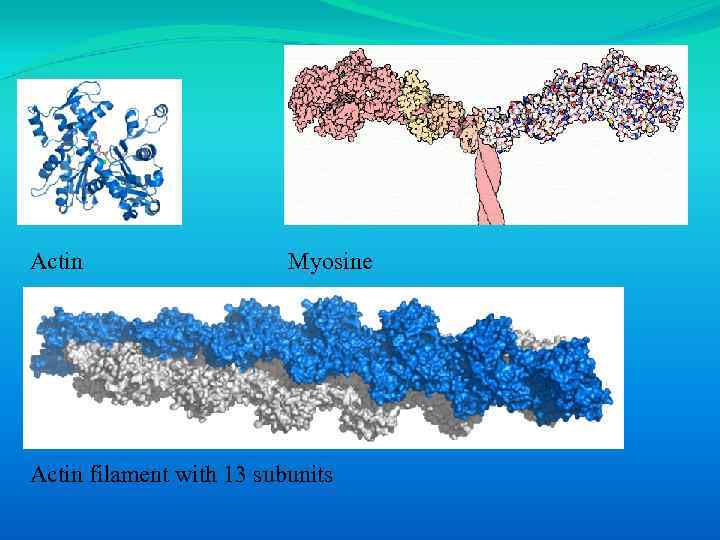

Actin Myosine Actin filament with 13 subunits

Actin Myosine Actin filament with 13 subunits

1. 9. 4. Sliding filament theory

1. 9. 4. Sliding filament theory

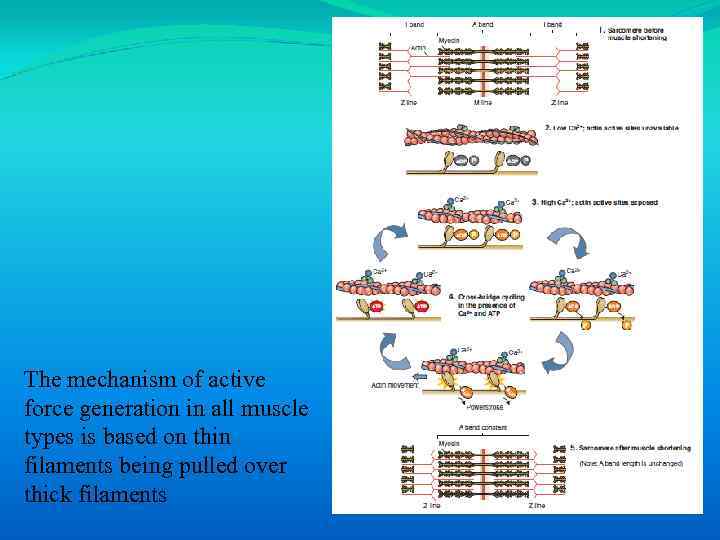

The mechanism of active force generation in all muscle types is based on thin filaments being pulled over thick filaments

The mechanism of active force generation in all muscle types is based on thin filaments being pulled over thick filaments

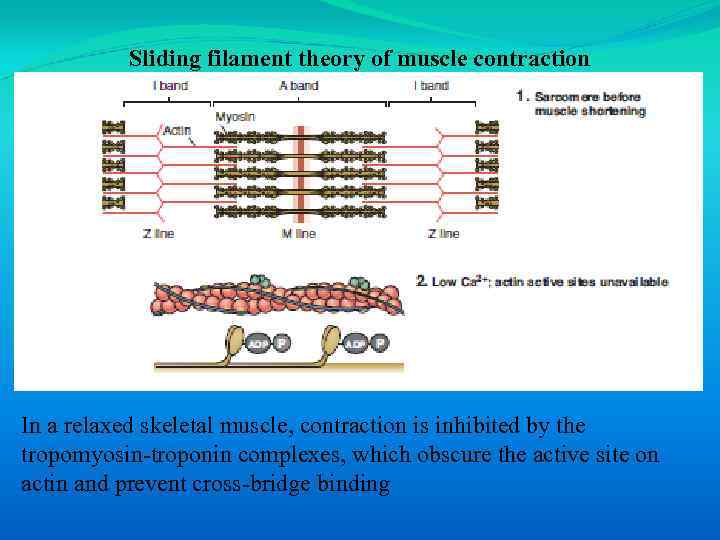

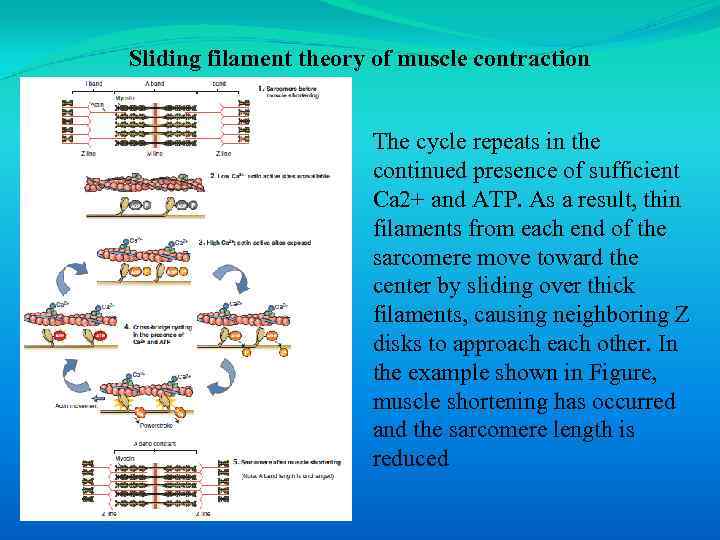

Sliding filament theory of muscle contraction In a relaxed skeletal muscle, contraction is inhibited by the tropomyosin-troponin complexes, which obscure the active site on actin and prevent cross-bridge binding

Sliding filament theory of muscle contraction In a relaxed skeletal muscle, contraction is inhibited by the tropomyosin-troponin complexes, which obscure the active site on actin and prevent cross-bridge binding

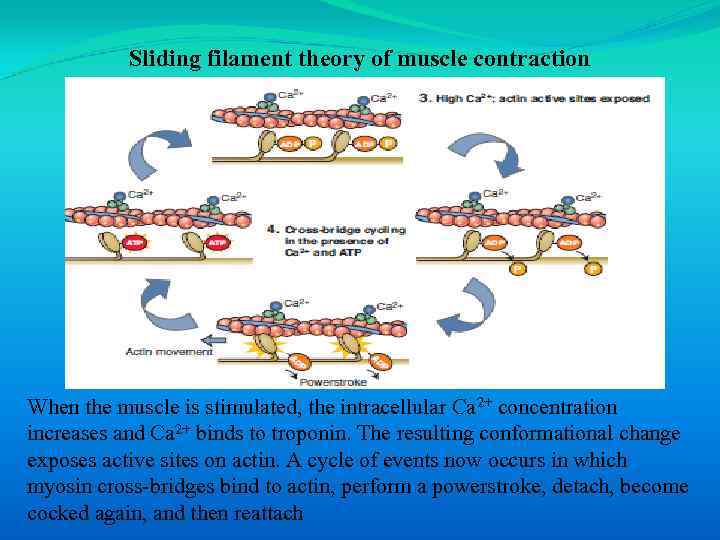

Sliding filament theory of muscle contraction When the muscle is stimulated, the intracellular Ca 2+ concentration increases and Ca 2+ binds to troponin. The resulting conformational change exposes active sites on actin. A cycle of events now occurs in which myosin cross-bridges bind to actin, perform a powerstroke, detach, become cocked again, and then reattach

Sliding filament theory of muscle contraction When the muscle is stimulated, the intracellular Ca 2+ concentration increases and Ca 2+ binds to troponin. The resulting conformational change exposes active sites on actin. A cycle of events now occurs in which myosin cross-bridges bind to actin, perform a powerstroke, detach, become cocked again, and then reattach

Sliding filament theory of muscle contraction The cycle repeats in the continued presence of sufficient Ca 2+ and ATP. As a result, thin filaments from each end of the sarcomere move toward the center by sliding over thick filaments, causing neighboring Z disks to approach each other. In the example shown in Figure, muscle shortening has occurred and the sarcomere length is reduced

Sliding filament theory of muscle contraction The cycle repeats in the continued presence of sufficient Ca 2+ and ATP. As a result, thin filaments from each end of the sarcomere move toward the center by sliding over thick filaments, causing neighboring Z disks to approach each other. In the example shown in Figure, muscle shortening has occurred and the sarcomere length is reduced

Muscle contraction only occurs after an increase in cytosolic Ca 2+, which follows the generation of a muscle action potential. In skeletal muscle, the source of Ca 2+ is the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR). To return a muscle to the relaxed state, Ca 2+ uptake occurs in the longitudinal tubules via Ca 2+-ATPases of the SR.

Muscle contraction only occurs after an increase in cytosolic Ca 2+, which follows the generation of a muscle action potential. In skeletal muscle, the source of Ca 2+ is the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR). To return a muscle to the relaxed state, Ca 2+ uptake occurs in the longitudinal tubules via Ca 2+-ATPases of the SR.

1. 9. 5. Force of contraction

1. 9. 5. Force of contraction

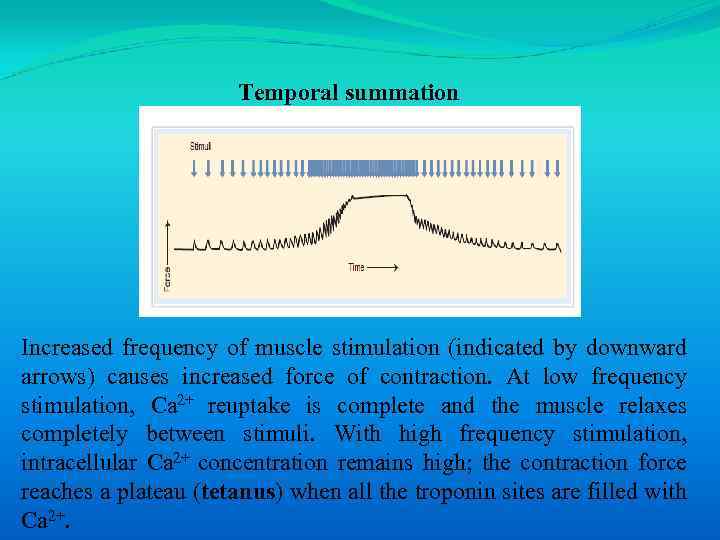

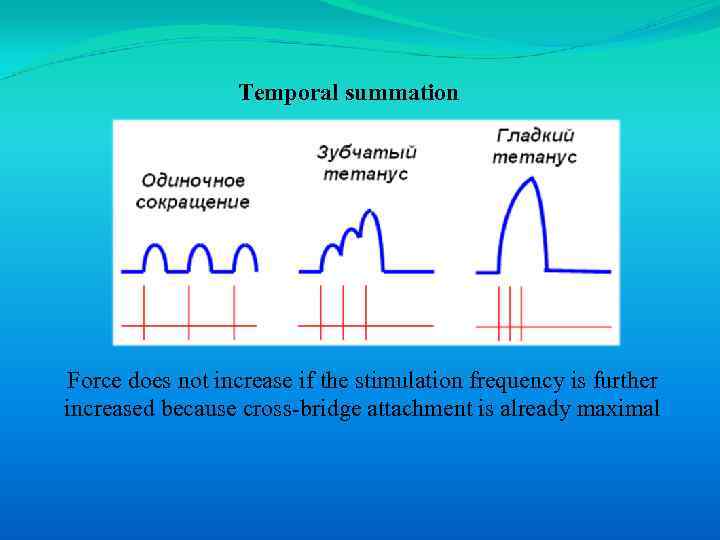

Temporal summation Increased frequency of muscle stimulation (indicated by downward arrows) causes increased force of contraction. At low frequency stimulation, Ca 2+ reuptake is complete and the muscle relaxes completely between stimuli. With high frequency stimulation, intracellular Ca 2+ concentration remains high; the contraction force reaches a plateau (tetanus) when all the troponin sites are filled with Ca 2+.

Temporal summation Increased frequency of muscle stimulation (indicated by downward arrows) causes increased force of contraction. At low frequency stimulation, Ca 2+ reuptake is complete and the muscle relaxes completely between stimuli. With high frequency stimulation, intracellular Ca 2+ concentration remains high; the contraction force reaches a plateau (tetanus) when all the troponin sites are filled with Ca 2+.

Temporal summation Force does not increase if the stimulation frequency is further increased because cross-bridge attachment is already maximal

Temporal summation Force does not increase if the stimulation frequency is further increased because cross-bridge attachment is already maximal

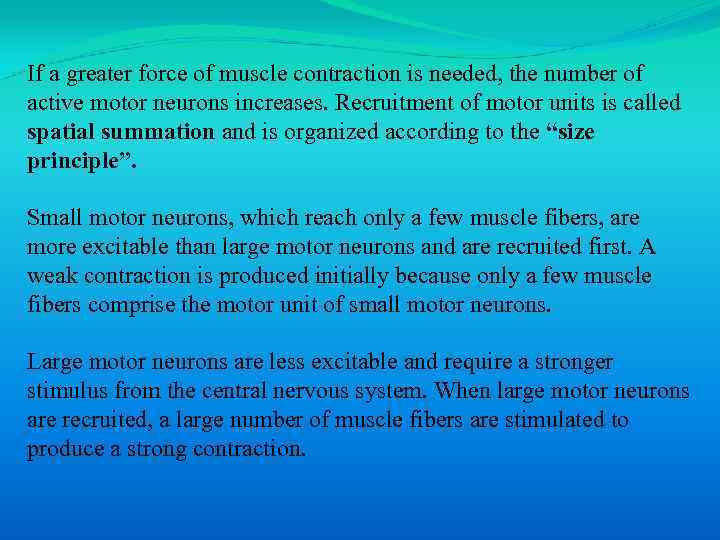

If a greater force of muscle contraction is needed, the number of active motor neurons increases. Recruitment of motor units is called spatial summation and is organized according to the “size principle”. Small motor neurons, which reach only a few muscle fibers, are more excitable than large motor neurons and are recruited first. A weak contraction is produced initially because only a few muscle fibers comprise the motor unit of small motor neurons. Large motor neurons are less excitable and require a stronger stimulus from the central nervous system. When large motor neurons are recruited, a large number of muscle fibers are stimulated to produce a strong contraction.

If a greater force of muscle contraction is needed, the number of active motor neurons increases. Recruitment of motor units is called spatial summation and is organized according to the “size principle”. Small motor neurons, which reach only a few muscle fibers, are more excitable than large motor neurons and are recruited first. A weak contraction is produced initially because only a few muscle fibers comprise the motor unit of small motor neurons. Large motor neurons are less excitable and require a stronger stimulus from the central nervous system. When large motor neurons are recruited, a large number of muscle fibers are stimulated to produce a strong contraction.

1. 9. 6. Skeletal muscle diversity

1. 9. 6. Skeletal muscle diversity

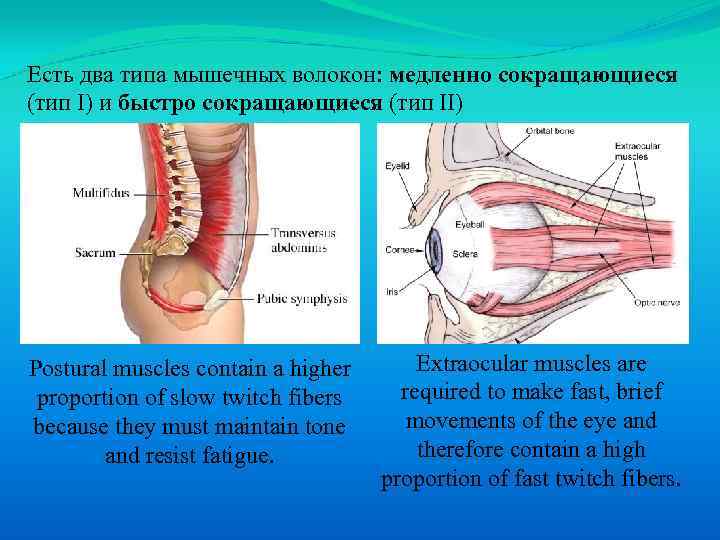

Есть два типа мышечных волокон: медленно сокращающиеся (тип I) и быстро сокращающиеся (тип II) Postural muscles contain a higher proportion of slow twitch fibers because they must maintain tone and resist fatigue. Extraocular muscles are required to make fast, brief movements of the eye and therefore contain a high proportion of fast twitch fibers.

Есть два типа мышечных волокон: медленно сокращающиеся (тип I) и быстро сокращающиеся (тип II) Postural muscles contain a higher proportion of slow twitch fibers because they must maintain tone and resist fatigue. Extraocular muscles are required to make fast, brief movements of the eye and therefore contain a high proportion of fast twitch fibers.

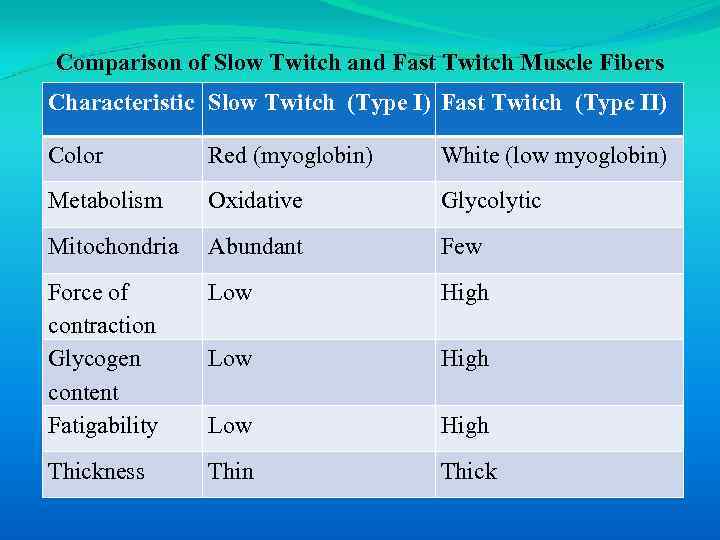

Comparison of Slow Twitch and Fast Twitch Muscle Fibers Characteristic Slow Twitch (Type I) Fast Twitch (Type II) Color Red (myoglobin) White (low myoglobin) Metabolism Oxidative Glycolytic Mitochondria Abundant Few Force of contraction Glycogen content Fatigability Low High Thickness Thin Thick

Comparison of Slow Twitch and Fast Twitch Muscle Fibers Characteristic Slow Twitch (Type I) Fast Twitch (Type II) Color Red (myoglobin) White (low myoglobin) Metabolism Oxidative Glycolytic Mitochondria Abundant Few Force of contraction Glycogen content Fatigability Low High Thickness Thin Thick

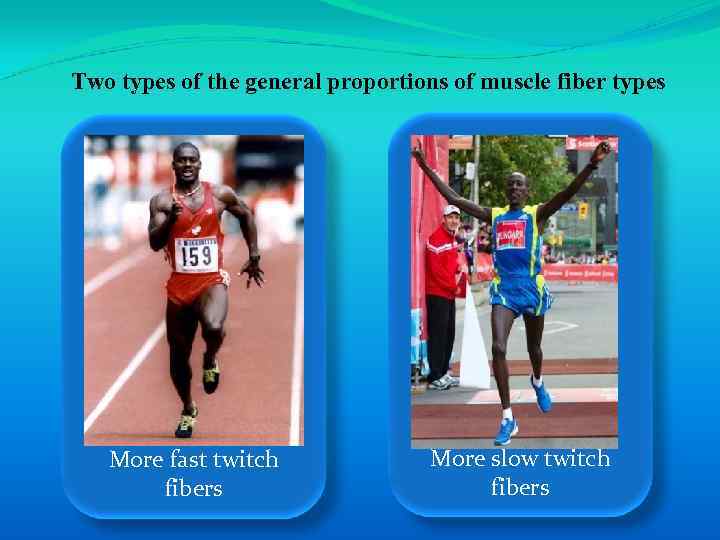

Two types of the general proportions of muscle fiber types More fast twitch fibers More slow twitch fibers

Two types of the general proportions of muscle fiber types More fast twitch fibers More slow twitch fibers

1. 10. Smooth muscle

1. 10. Smooth muscle

Smooth muscle lines the walls of most hollow organs, including organs of the vascular, gastrointestinal, respiratory, urinary, and reproductive systems.

Smooth muscle lines the walls of most hollow organs, including organs of the vascular, gastrointestinal, respiratory, urinary, and reproductive systems.

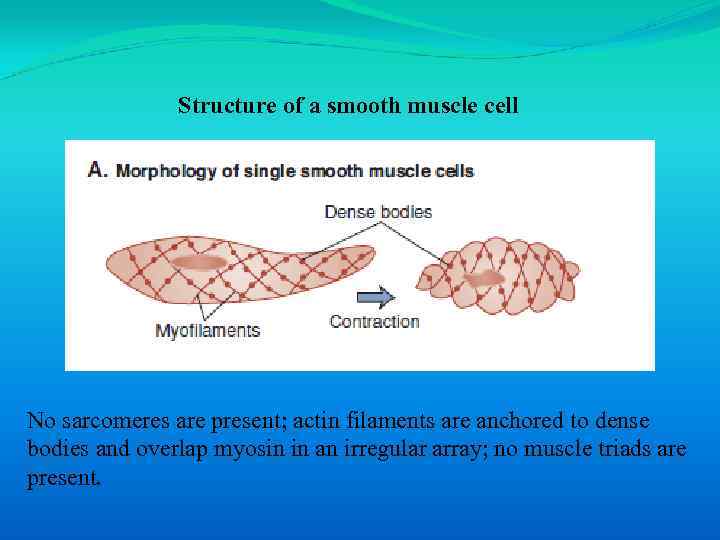

Structure of a smooth muscle cell No sarcomeres are present; actin filaments are anchored to dense bodies and overlap myosin in an irregular array; no muscle triads are present.

Structure of a smooth muscle cell No sarcomeres are present; actin filaments are anchored to dense bodies and overlap myosin in an irregular array; no muscle triads are present.

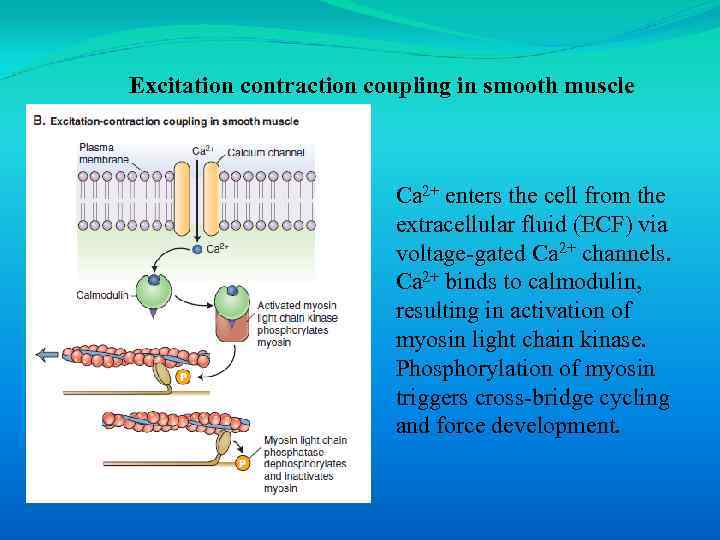

Excitation contraction coupling in smooth muscle Ca 2+ enters the cell from the extracellular fluid (ECF) via voltage-gated Ca 2+ channels. Ca 2+ binds to calmodulin, resulting in activation of myosin light chain kinase. Phosphorylation of myosin triggers cross-bridge cycling and force development.

Excitation contraction coupling in smooth muscle Ca 2+ enters the cell from the extracellular fluid (ECF) via voltage-gated Ca 2+ channels. Ca 2+ binds to calmodulin, resulting in activation of myosin light chain kinase. Phosphorylation of myosin triggers cross-bridge cycling and force development.

An important feature of some smooth muscles (e. g. , sphincters) is the ability to maintain force over long periods. The maintenance of muscle tone without high rates of ATP consumption is possible because cross-bridges can remain attached to actin for extended periods.

An important feature of some smooth muscles (e. g. , sphincters) is the ability to maintain force over long periods. The maintenance of muscle tone without high rates of ATP consumption is possible because cross-bridges can remain attached to actin for extended periods.

Thank you for your attention!

Thank you for your attention!