cc83805d77ed9ca0698b7a2b4d84f657.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 14

Changing Environmental Behaviour: Fiscal Incentives, 'Nudge' and Environmental Citizenship Andrew Dobson (Keele University, UK) Lancaster February 23 rd 2015

We need to reduce the size of ‘our’ carbon footprint … … but how? 1. Fiscal incentives and disincentives 2. ‘Nudge’ theory 3. Environmental citizenship

Fiscal incentives and disincentives - how do they work? Impose a fine or a charge, or offer a reward, and behaviour will change £ 500 p. a. car tax Buy a car but which one? £ 0 p. a. car tax

Fiscal incentives/disincentives - two examples e. g. London’s congestion charge, Irish Republic’s Plastic bag environmental levy (2002) • 36% reduction in congestion in centre of London • 1 billion plastic bags removed from circulation

Two advantages of fiscal dis/incentives 1. They can work fast 2. They require no environmental/sustainability commitment Four potential problems with fiscal dis/incentives 1. The direction of the political wind 2. Respond to fiscal prompt, not to reasons underlying it (no opportunity for ‘social learning’, no room for ethics) 3. Size of price and charge rises - political will? 4. One-eyed model of human motivation

‘Nudge’ - what is it, and how does it work? Think about your favourite supermarket This is called ‘choice architecture’ (2008) ‘libertarian paternalism’ (pp. 5 -6)

Behaviour change options: 1. Legislation (can be expensive and inappropriate) 2. Incentives (depends on people making rational decisions) 3. Information (ditto)

Nudge ‘goes with the grain of how we think and act’ … ‘our inbuilt responses to the world’ … ‘It turns our behaviour is a lot more “automatic” and somewhat less “reflective” than we have previously thought’ Potentially dangerous: ‘inbuilt responses’ have been used to justify all sorts of reactionary politics No opportunity for social learning – no reasons given, explicitly No room for norms, values, ethics – this misunderstands sustainability (‘category mistake’)

Towards environmental citizenship: ‘The question of sustainable behaviour cannot be reduced to a discussion of balancing carrots and sticks. The citizen that sorts her garbage or that prefers ecological goods will often do this because she is committed to ecological values and ends. The citizen may not, that is, act in sustainable ways solely out of economic or practical incentives: people sometimes choose to do good for other reasons than fear (of punishment or loss) or desire (for economic rewards and social status). People sometimes do good because they want to be virtuous’. (Ludwig Beckman, ‘Virtue, Sustainability and Liberal Values’, 2001)

Characteristics of environmental citizenship (1) • a recognition that self-interested behaviour will not always protect or sustain public goods such as the environment. Thus environmental citizens make a commitment to the common good. • a recognition that environmental responsibilities follow from environmental rights as a matter of natural justice.

Characteristics of environmental citizenship (2) • a recognition that rights and responsibilities transcend national and generational boundaries • working for all of the above in private and in public (agitation!)

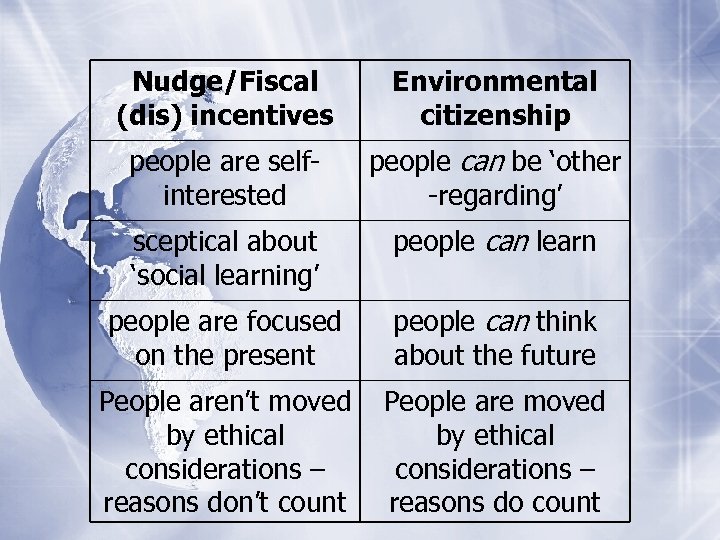

Nudge/Fiscal (dis) incentives Environmental citizenship people are selfinterested people can be ‘other -regarding’ sceptical about ‘social learning’ people can learn people are focused on the present people can think about the future People aren’t moved by ethical considerations – reasons don’t count People are moved by ethical considerations – reasons do count

The ‘crowding-out’ phenomenon … • are citizen- and consumer-type motivations in conflict with one another at the level of policy design? • ‘monetary incentives can “crowd out” other sorts of motivation, often called “intrinsic” motivation’ • example from old people’s care home • people were ‘demoralised by the incentive structure even ‘de-moralised’? • ‘once crowded out, the intrinsic motivation rarely returns when the monetary incentive is removed’ NB key role of ‘environmental champions’

So how do we reduce carbon footprints? • by focussing on people’s self-interest and giving them financial incentives and disincentives? • by changing the context in which people’s choices are made ‘choice architecture’? • by relying on people’s capacity to think of others, to think of the future, and to act in the name of justice? • by moving further ‘upstream’ where the hydrocarbons come out of the ground?

cc83805d77ed9ca0698b7a2b4d84f657.ppt