457ea78bac94f9004d11a2427d527341.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 41

Challenges in Combinatorial Scientific Computing John R. Gilbert University of California, Santa Barbara Grand Challenges in Data-Intensive Discovery October 28, 2010 1 Support: NSF, DOE, Intel, Microsoft

Combinatorial Scientific Computing “I observed that most of the coefficients in our matrices were zero; i. e. , the nonzeros were ‘sparse’ in the matrix, and that typically the triangular matrices associated with the forward and back solution provided by Gaussian elimination would remain sparse if pivot elements were chosen with care” - Harry Markowitz, describing the 1950 s work on portfolio theory that won the 1990 Nobel Prize for Economics 2

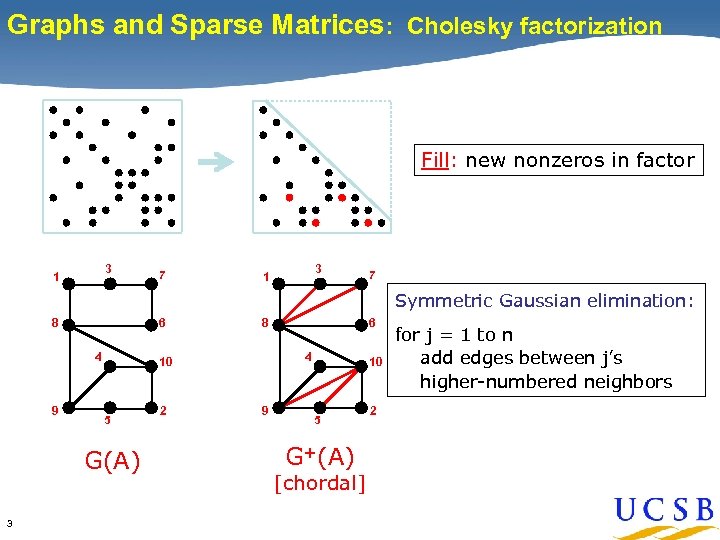

Graphs and Sparse Matrices: Cholesky factorization Fill: new nonzeros in factor 3 1 7 Symmetric Gaussian elimination: 6 8 4 9 G(A) 3 4 10 5 2 6 8 9 10 5 G+(A) [chordal] 2 for j = 1 to n add edges between j’s higher-numbered neighbors

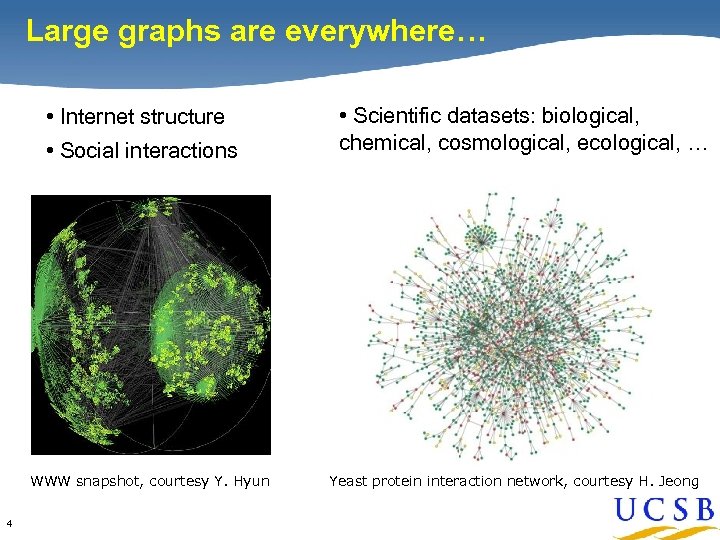

Large graphs are everywhere… • Internet structure • Social interactions WWW snapshot, courtesy Y. Hyun 4 • Scientific datasets: biological, chemical, cosmological, ecological, … Yeast protein interaction network, courtesy H. Jeong

The Challenge of the Middle 5

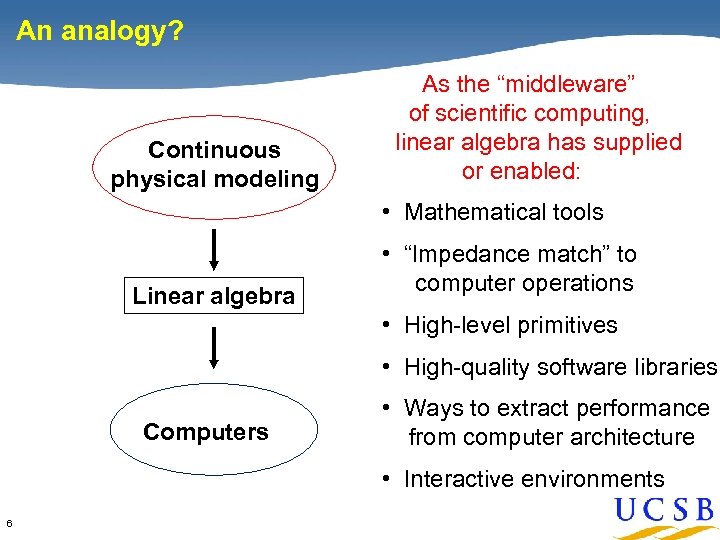

An analogy? Continuous physical modeling As the “middleware” of scientific computing, linear algebra has supplied or enabled: • Mathematical tools Linear algebra • “Impedance match” to computer operations • High-level primitives • High-quality software libraries Computers • Ways to extract performance from computer architecture • Interactive environments 6

An analogy? Continuous physical modeling Discrete structure analysis Linear algebra Graph theory Computers 7 Computers

An analogy? Well, we’re not there yet …. Mathematical tools ? “Impedance match” to computer operations Discrete structure analysis ? High-level primitives ? High-quality software libs Graph theory ? Ways to extract performance from computer architecture ? Interactive environments 8 Computers

The Case for Primitives 9

![All-Pairs Shortest Paths on a GPU [Buluc et al. ] Based on R-Kleene algorithm All-Pairs Shortest Paths on a GPU [Buluc et al. ] Based on R-Kleene algorithm](https://present5.com/presentation/457ea78bac94f9004d11a2427d527341/image-10.jpg)

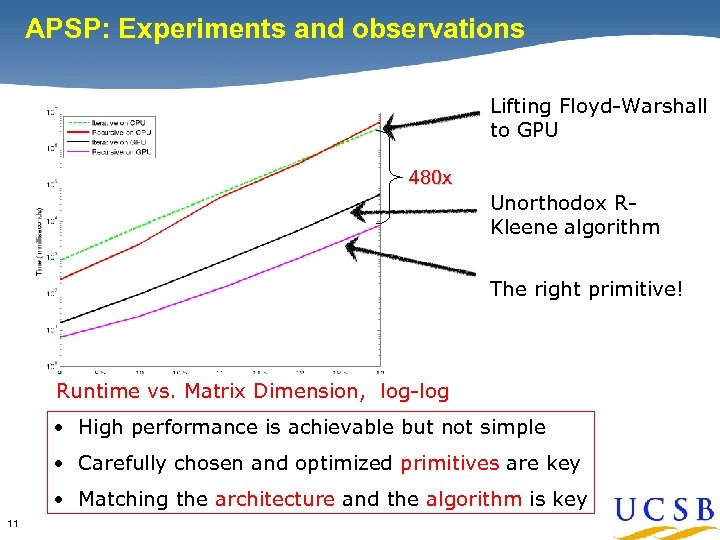

All-Pairs Shortest Paths on a GPU [Buluc et al. ] Based on R-Kleene algorithm Well suited for GPU architecture: • In-place computation => low memory bandwidth • Few, large Mat. Mul calls => low GPU dispatch overhead A A D B + is “min”, A = A*; D × is “add” % recursive call • Recursion stack on host CPU, B = AB; C = CA; not on multicore GPU D = D + CB; • Careful tuning of GPU code • 10 B C C Fast matrix-multiply kernel D = D*; % recursive call B = BD; C = DC; A = A + BC;

APSP: Experiments and observations The Case for Primitives Lifting Floyd-Warshall to GPU 480 x Unorthodox RKleene algorithm The right primitive! Runtime vs. Matrix Dimension, log-log • High performance is achievable but not simple • Carefully chosen and optimized primitives are key • Matching the architecture and the algorithm is key 11

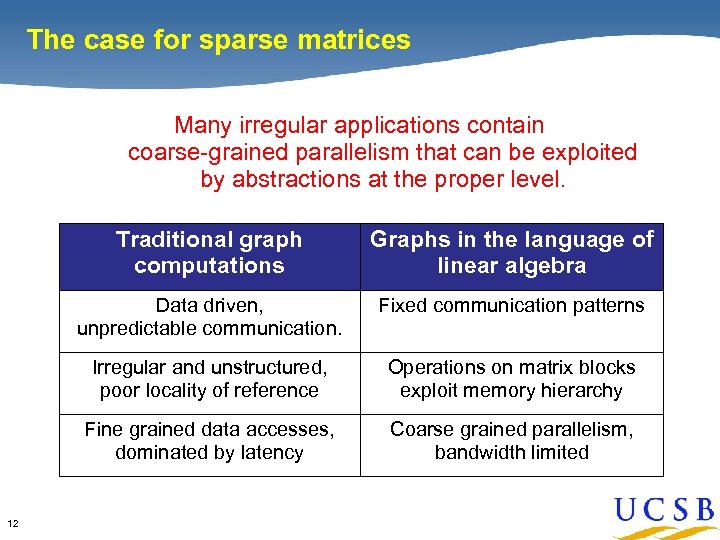

The case for sparse matrices The Case for Sparse Matrices Many irregular applications contain coarse-grained parallelism that can be exploited by abstractions at the proper level. Traditional graph computations Data driven, unpredictable communication. Fixed communication patterns Irregular and unstructured, poor locality of reference Operations on matrix blocks exploit memory hierarchy Fine grained data accesses, dominated by latency 12 Graphs in the language of linear algebra Coarse grained parallelism, bandwidth limited

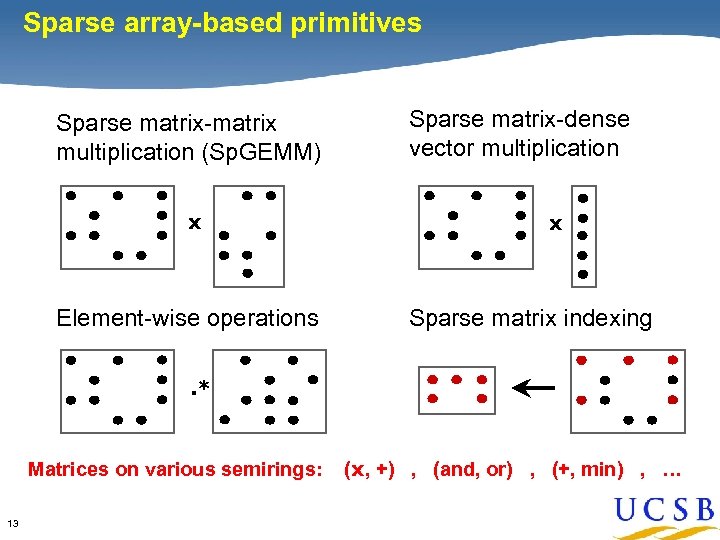

Sparse array-based primitives Identification of Primitives Sparse matrix-matrix multiplication (Sp. GEMM) x Element-wise operations Sparse matrix-dense vector multiplication x Sparse matrix indexing . * Matrices on various semirings: 13 (x, +) , (and, or) , (+, min) , …

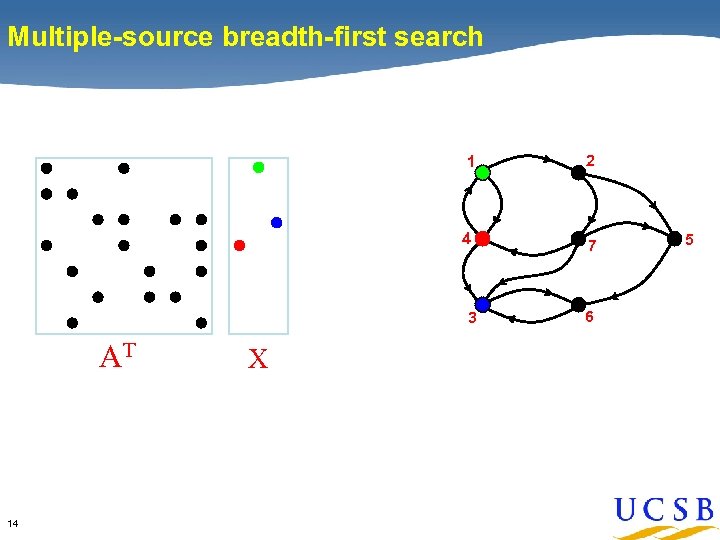

Multiple-source breadth-first search 1 2 4 7 3 AT 14 X 6 5

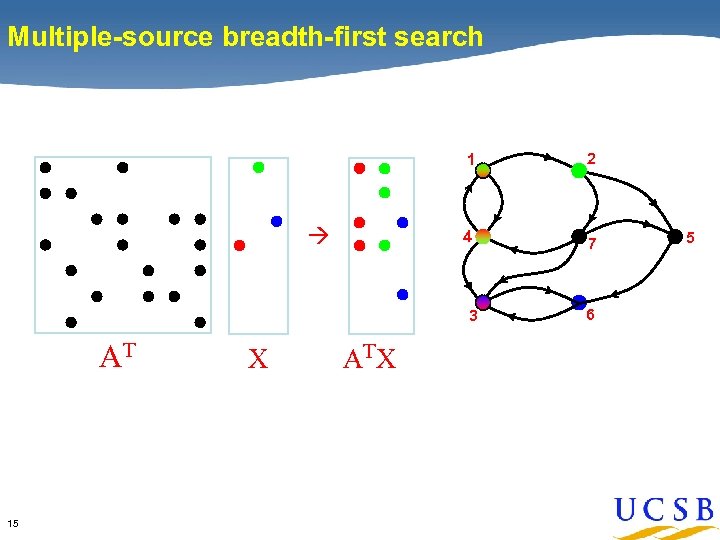

Multiple-source breadth-first search 1 4 2 7 3 AT 15 X AT X 6 5

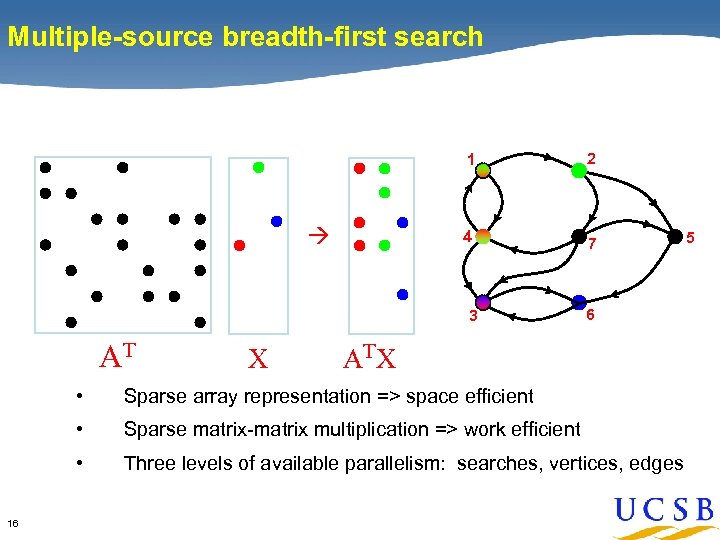

Multiple-source breadth-first search 1 4 2 7 3 AT X 6 AT X • • Sparse matrix-matrix multiplication => work efficient • 16 Sparse array representation => space efficient Three levels of available parallelism: searches, vertices, edges 5

A Few Examples 17

![Combinatorial BLAS [Buluc, G] A parallel graph library based on distributed-memory sparse arrays and Combinatorial BLAS [Buluc, G] A parallel graph library based on distributed-memory sparse arrays and](https://present5.com/presentation/457ea78bac94f9004d11a2427d527341/image-18.jpg)

Combinatorial BLAS [Buluc, G] A parallel graph library based on distributed-memory sparse arrays and algebraic graph primitives Typical software stack Betweenness Centrality (BC) What fraction of shortest paths pass through this node? Brandes’ algorithm 18

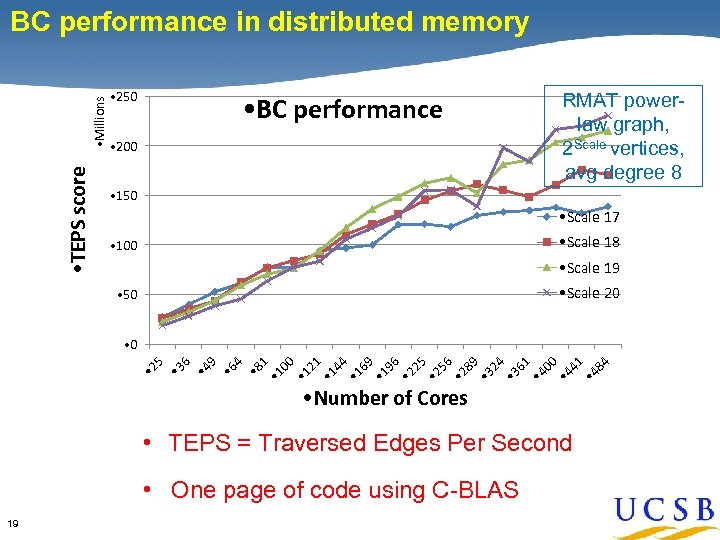

• TEPS score • Millions BC performance in distributed memory • 250 • BC performance • 200 RMAT powerlaw graph, 2 Scale vertices, avg degree 8 • 150 • Scale 17 • Scale 18 • 100 • Scale 19 • Scale 20 • 50 • 8 1 • 1 00 • 1 21 • 1 44 • 1 69 • 1 96 • 2 25 • 2 56 • 2 89 • 3 24 • 3 61 • 4 00 • 4 41 • 4 84 4 • 6 9 • 4 6 • 3 • 2 5 • 0 • Number of Cores • TEPS = Traversed Edges Per Second • One page of code using C-BLAS 19

![KDT: A toolbox for graph analysis and pattern discovery [G, Reinhardt, Shah] Layer 1: KDT: A toolbox for graph analysis and pattern discovery [G, Reinhardt, Shah] Layer 1:](https://present5.com/presentation/457ea78bac94f9004d11a2427d527341/image-20.jpg)

KDT: A toolbox for graph analysis and pattern discovery [G, Reinhardt, Shah] Layer 1: Graph Theoretic Tools • • Global structure of graphs • Graph partitioning and clustering • Graph generators • Visualization and graphics • Scan and combining operations • 20 Graph operations Utilities

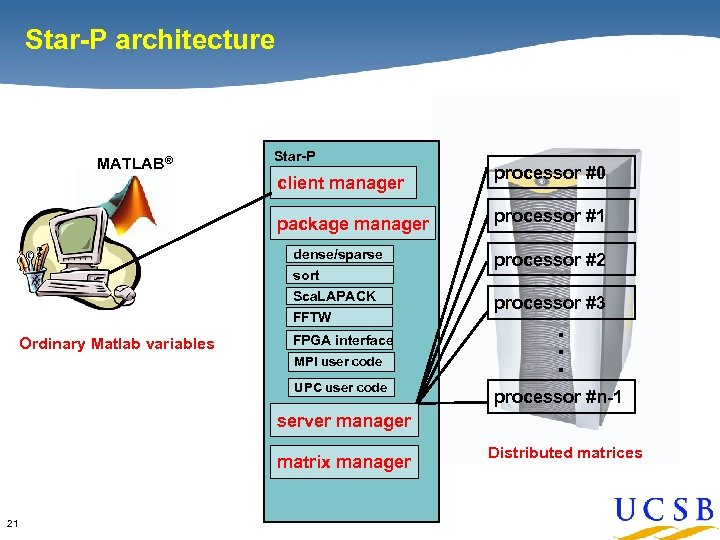

Star-P architecture MATLAB® Star-P client manager package manager processor #0 processor #1 processor #2 Sca. LAPACK processor #3 FFTW Ordinary Matlab variables FPGA interface MPI user code UPC user code . . . dense/sparse sort processor #n-1 server manager matrix manager 21 Distributed matrices

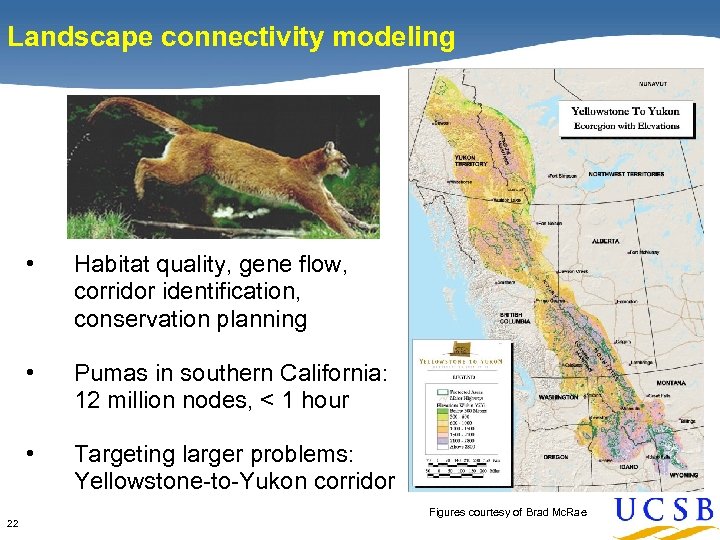

Landscape connectivity modeling • • Pumas in southern California: 12 million nodes, < 1 hour • 22 Habitat quality, gene flow, corridor identification, conservation planning Targeting larger problems: Yellowstone-to-Yukon corridor Figures courtesy of Brad Mc. Rae

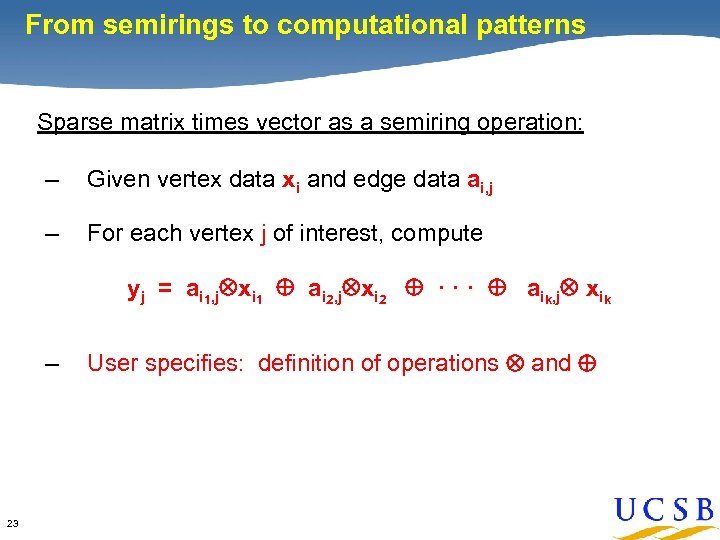

From semirings to computational patterns Sparse matrix times vector as a semiring operation: – Given vertex data xi and edge data ai, j – For each vertex j of interest, compute yj = ai 1, j xi 1 ai 2, j xi 2 · · · aik, j xik – 23 User specifies: definition of operations and

From semirings to computational patterns Sparse matrix times vector as a computational pattern: – – For each vertex of interest, combine data from neighboring vertices and edges – 24 Given vertex data and edge data User specifies: desired computation on data from neighbors

Sp. GEMM as a computational pattern • Explore length-two paths that use specified vertices • Possibly do some filtering, accumulation, or other computation with vertex and edge attributes • E. g. “friends of friends” (think Facebook) • May or may not want to form the product graph explicitly • Formulation as semiring matrix multiplication is often possible but sometimes clumsy • Same data flow and communication patterns as in Sp. GEMM 25

Graph BLAS: A pattern-based library • • Common framework integrates algebraic (edge-based), visitor (traversal-based), and map-reduce patterns. • 2 D compressed sparse block structure supports userdefined edge/vertex/attribute types and operations. • “Hypersparse” kernels tuned to reduce data movement. • 26 User-specified operations and attributes give the performance benefits of algebraic primitives with a more intuitive and flexible interface. Initial target: manycore and multisocket shared memory.

The Challenge of Architecture and Algorithms 27

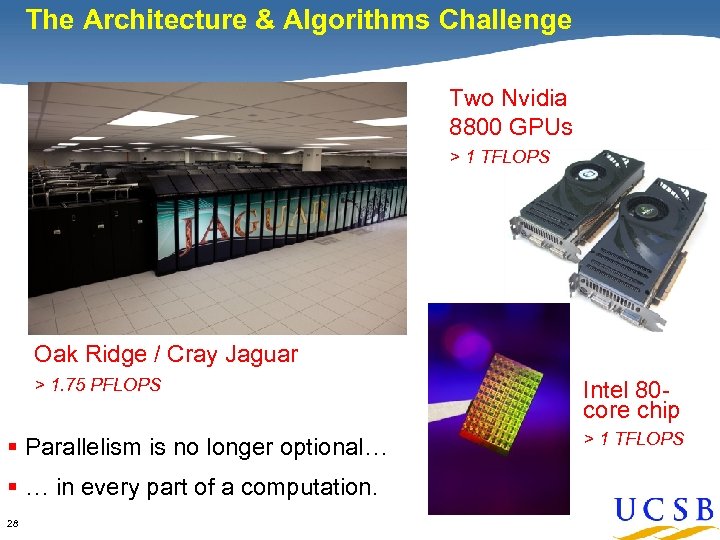

The Architecture & Algorithms Challenge Two Nvidia 8800 GPUs > 1 TFLOPS Oak Ridge / Cray Jaguar > 1. 75 PFLOPS § Parallelism is no longer optional… § … in every part of a computation. 28 Intel 80 core chip > 1 TFLOPS

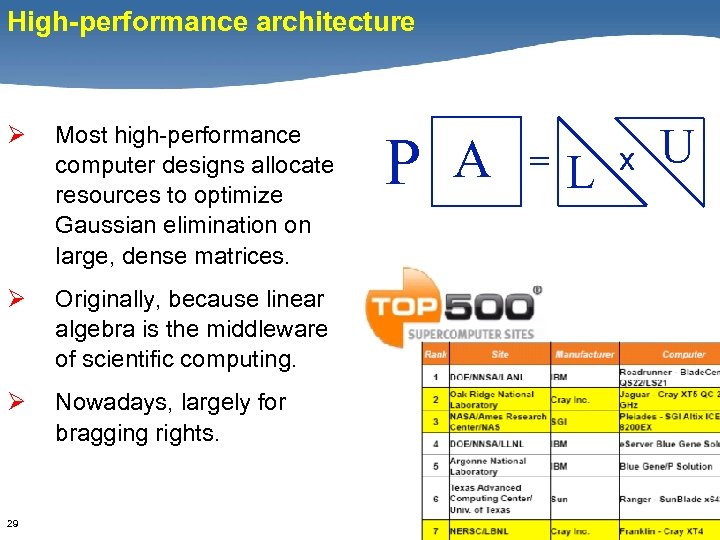

High-performance architecture Ø Most high-performance computer designs allocate resources to optimize Gaussian elimination on large, dense matrices. Ø Originally, because linear algebra is the middleware of scientific computing. Ø Nowadays, largely for bragging rights. 29 P A = L x U

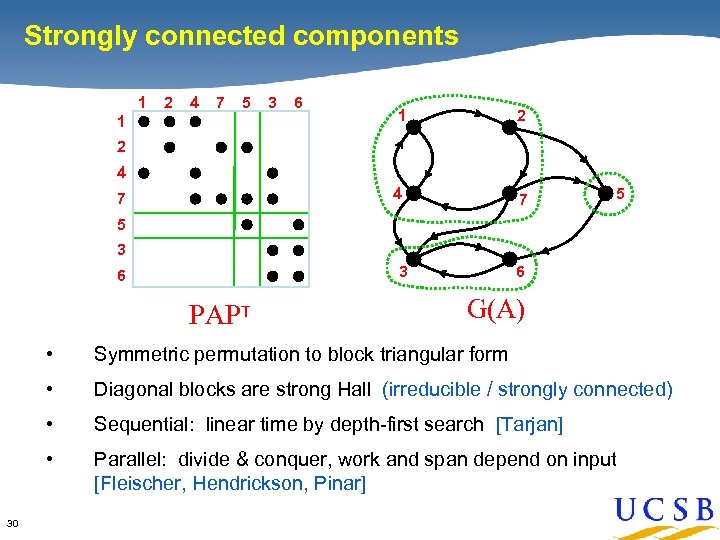

Strongly connected components 1 2 4 7 5 3 6 1 2 4 1 7 2 4 7 5 5 3 6 PAPT G(A) • • Diagonal blocks are strong Hall (irreducible / strongly connected) • Sequential: linear time by depth-first search [Tarjan] • 30 Symmetric permutation to block triangular form Parallel: divide & conquer, work and span depend on input [Fleischer, Hendrickson, Pinar]

The memory wall blues Ø Most of memory is hundreds or thousands of cycles away from the processor that wants it. Ø You can buy more bandwidth, but you can’t buy less latency. (Speed of light, for one thing. ) 31

The memory wall blues Ø Most of memory is hundreds or thousands of cycles away from the processor that wants it. Ø You can buy more bandwidth, but you can’t buy less latency. (Speed of light, for one thing. ) Ø You can hide latency with either locality or parallelism. 32

The memory wall blues Ø Most of memory is hundreds or thousands of cycles away from the processor that wants it. Ø You can buy more bandwidth, but you can’t buy less latency. (Speed of light, for one thing. ) Ø You can hide latency with either locality or parallelism. Ø Most interesting graph problems have lousy locality. Ø Thus the algorithms need even more parallelism! 33

Architectural impact on algorithms Full matrix multiplication: C = A * B C = 0; for i = 1 : n for j = 1 : n for k = 1 : n C(i, j) = C(i, j) + A(i, k) * B(k, j); O(n 3) operations 34

![Architectural impact on algorithms Naïve 3 -loop matrix multiply [Alpern et al. , 1992]: Architectural impact on algorithms Naïve 3 -loop matrix multiply [Alpern et al. , 1992]:](https://present5.com/presentation/457ea78bac94f9004d11a2427d527341/image-35.jpg)

Architectural impact on algorithms Naïve 3 -loop matrix multiply [Alpern et al. , 1992]: 12000 would take 1095 years T = N 4. 7 Size 2000 took 5 days Naïve algorithm is O(N 5) time under UMH model. BLAS-3 DGEMM and recursive blocked algorithms are O(N 3). 35 Diagram from Larry Carter

The architecture & algorithms challenge Ø Ø 36 A big opportunity exists for computer architecture to influence combinatorial algorithms. (Maybe even vice versa. )

A novel architectural approach: Cray MTA / XMT • • Per-tick context switching • Uniform (sort of) memory access time • 37 Hide latency by massive multithreading But the economic case is still not completely clear.

A Few Other Challenges 38

The Productivity Challenge Raw performance isn’t always the only criterion. Other factors include: • • Interactive response for data exploration and viz • Rapid prototyping • 39 Seamless scaling from desktop to HPC Just plain programmability

The Education Challenge Ø How do you teach this stuff? Ø Where do you go to take courses in Ø Graph algorithms … Ø … on massive data sets … Ø … in the presence of uncertainty … Ø … analyzed on parallel computers … Ø … applied to a domain science? 40

Final thoughts • • Linear algebra and combinatorics can support each other in computation as well as in theory. • A big opportunity exists for computer architecture to influence combinatorial algorithms. • 41 Combinatorial algorithms are pervasive in scientific computing and will become more so. This is a great time to be doing research in combinatorial scientific computing!

457ea78bac94f9004d11a2427d527341.ppt