47f7ee882649ab1bfa3147ef89b74742.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 52

Ch 3: Productivity, Output, and Employment Abel & Bernake: Macro Ch 3 Varian: Ch 10, Ch 19 1

Chapter Outline The Production Function p The Demand for Labor p The Supply of Labor p Labor Market Equilibrium p Unemployment p Relating Output and Unemployment: Okun’s Law p 2

The production function describe relationship between inputs and output. p Real Output (Y) p Inputs: factors of production 生產要素 Y = AF(K, N) (3. 1) p K = capital: tools, machines, and structures N = labor: physical and mental efforts of workers F(.) reflects the economy’s level of technology A= “total factor productivity” (the effectiveness with which capital and labor are used) 3

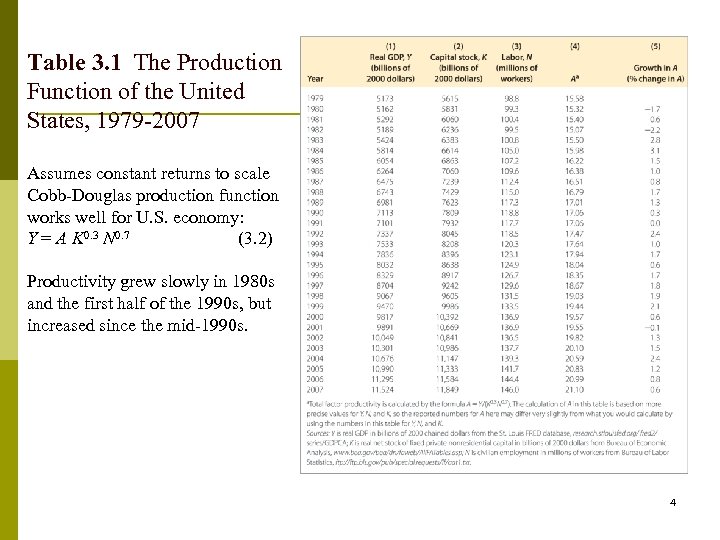

Table 3. 1 The Production Function of the United States, 1979 -2007 Assumes constant returns to scale Cobb-Douglas production function works well for U. S. economy: Y = A K 0. 3 N 0. 7 (3. 2) Productivity grew slowly in 1980 s and the first half of the 1990 s, but increased since the mid-1990 s. 4

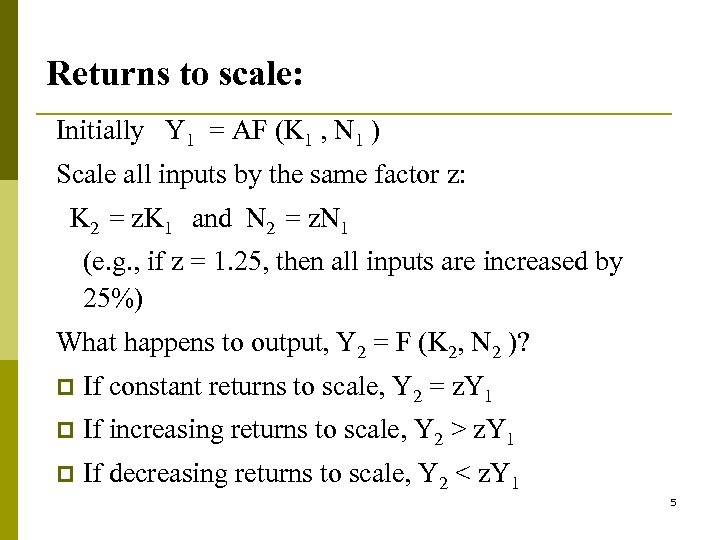

Returns to scale: Initially Y 1 = AF (K 1 , N 1 ) Scale all inputs by the same factor z: K 2 = z. K 1 and N 2 = z. N 1 (e. g. , if z = 1. 25, then all inputs are increased by 25%) What happens to output, Y 2 = F (K 2, N 2 )? p If constant returns to scale, Y 2 = z. Y 1 p If increasing returns to scale, Y 2 > z. Y 1 p If decreasing returns to scale, Y 2 < z. Y 1 5

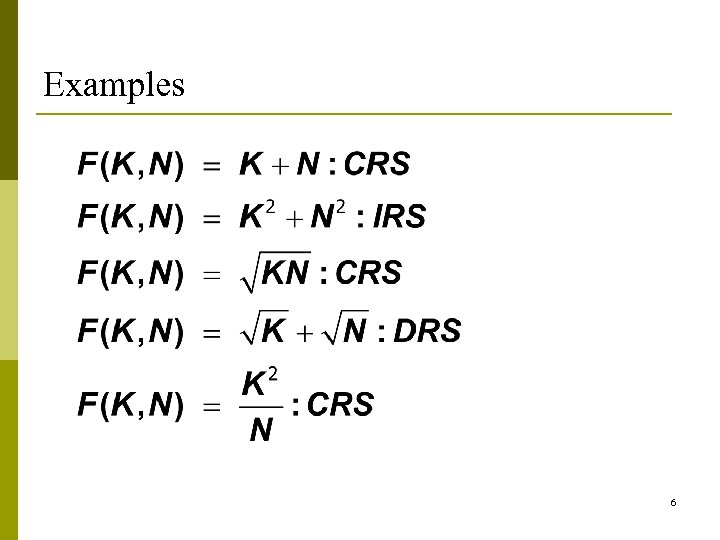

Examples 6

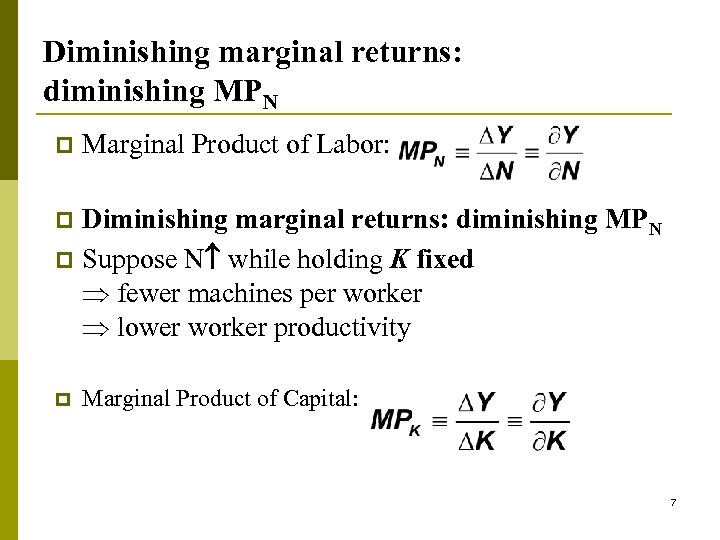

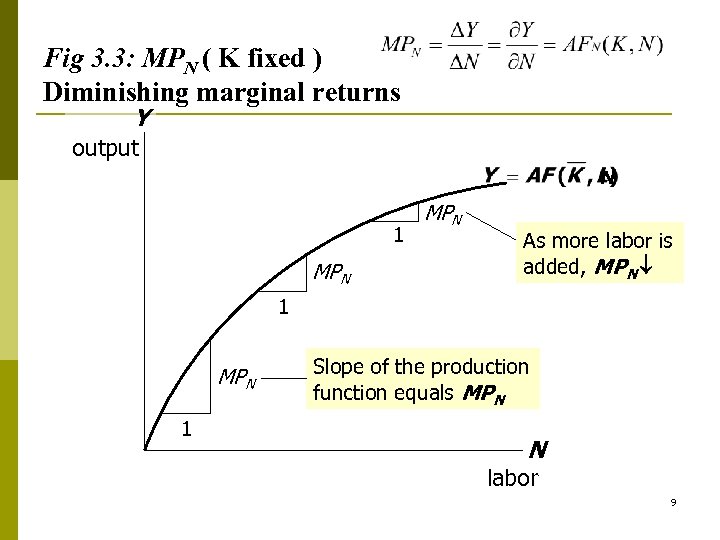

Diminishing marginal returns: diminishing MPN p Marginal Product of Labor: Diminishing marginal returns: diminishing MPN p Suppose N while holding K fixed fewer machines per worker lower worker productivity p p Marginal Product of Capital: 7

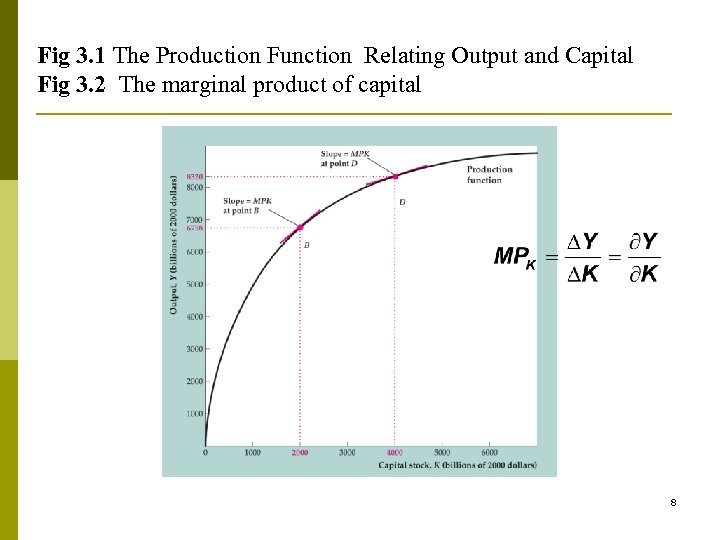

Fig 3. 1 The Production Function Relating Output and Capital Fig 3. 2 The marginal product of capital 8

Fig 3. 3: MPN ( K fixed ) Diminishing marginal returns Y output N 1 MPN As more labor is added, MPN 1 MPN 1 Slope of the production function equals MPN N labor 9

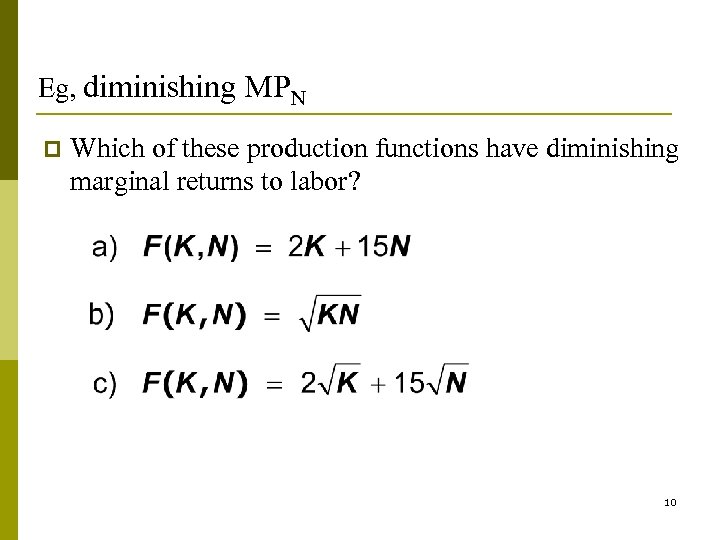

Eg, diminishing MPN p Which of these production functions have diminishing marginal returns to labor? 10

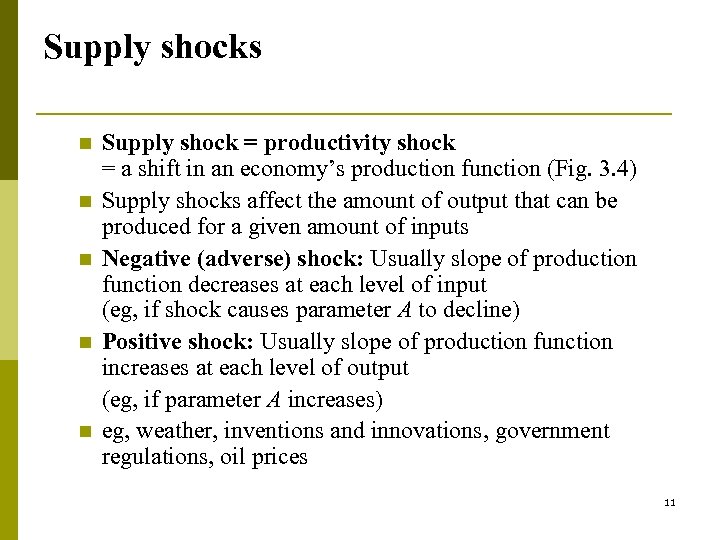

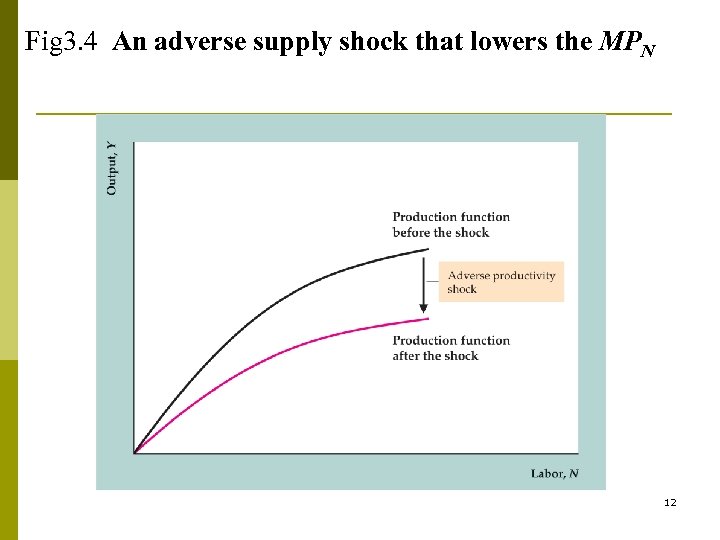

Supply shocks n n n Supply shock = productivity shock = a shift in an economy’s production function (Fig. 3. 4) Supply shocks affect the amount of output that can be produced for a given amount of inputs Negative (adverse) shock: Usually slope of production function decreases at each level of input (eg, if shock causes parameter A to decline) Positive shock: Usually slope of production function increases at each level of output (eg, if parameter A increases) eg, weather, inventions and innovations, government regulations, oil prices 11

Fig 3. 4 An adverse supply shock that lowers the MPN 12

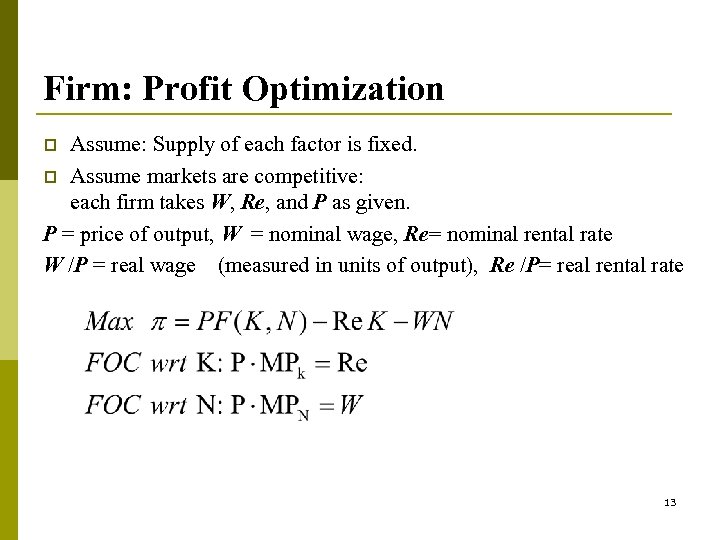

Firm: Profit Optimization Assume: Supply of each factor is fixed. p Assume markets are competitive: each firm takes W, Re, and P as given. P = price of output, W = nominal wage, Re= nominal rental rate W /P = real wage (measured in units of output), Re /P= real rental rate p 13

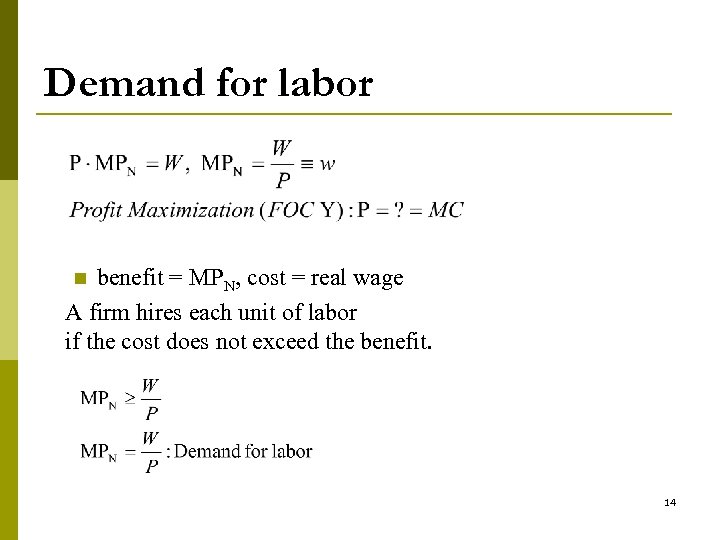

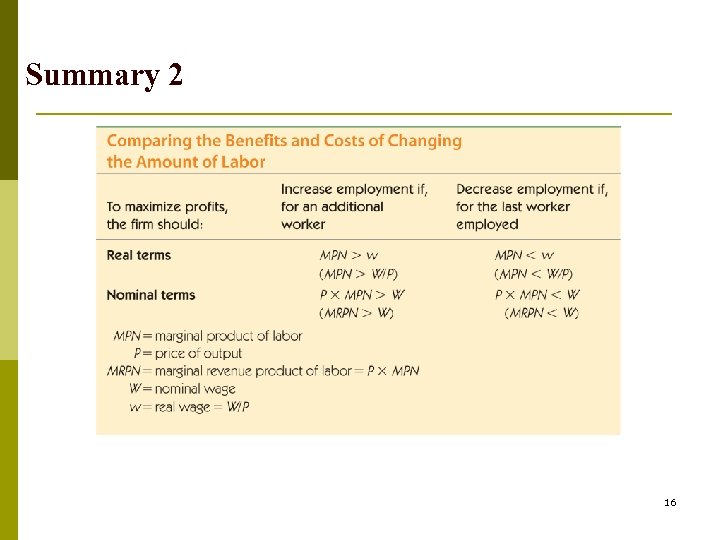

Demand for labor benefit = MPN, cost = real wage A firm hires each unit of labor if the cost does not exceed the benefit. n 14

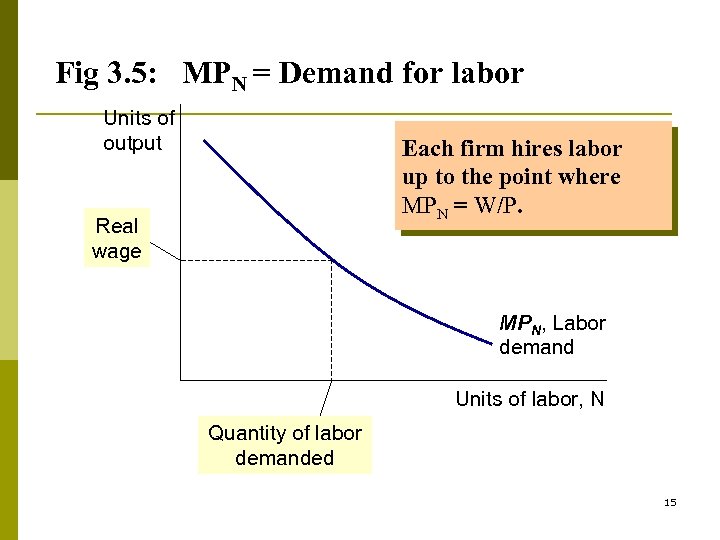

Fig 3. 5: MPN = Demand for labor Units of output Each firm hires labor up to the point where MPN = W/P. Real wage MPN, Labor demand Units of labor, N Quantity of labor demanded 15

Summary 2 16

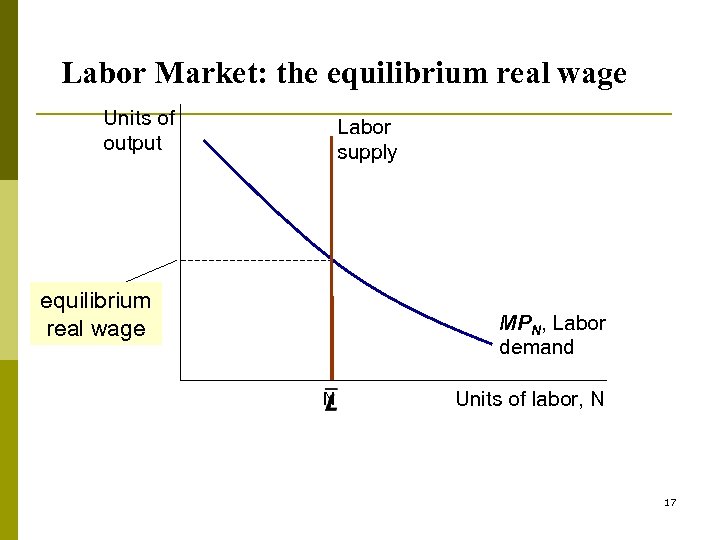

Labor Market: the equilibrium real wage Units of output Labor supply equilibrium real wage MPN, Labor demand N Units of labor, N 17

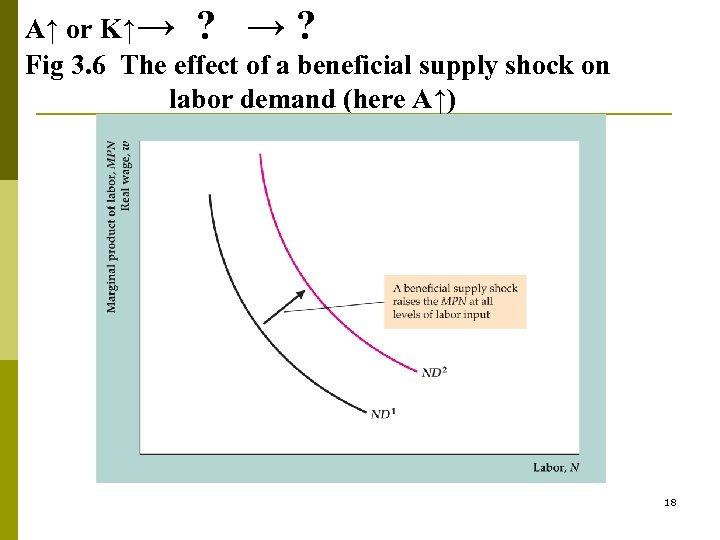

A↑ or K↑→ ? Fig 3. 6 The effect of a beneficial supply shock on labor demand (here A↑) 18

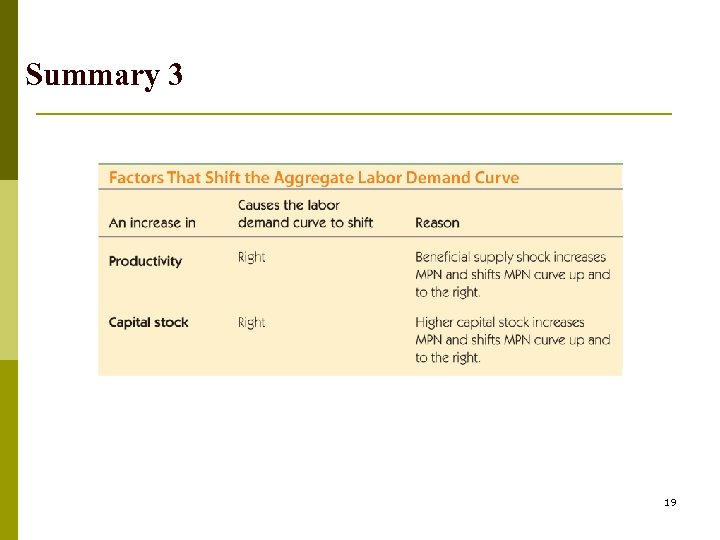

Summary 3 19

The Supply of Labor Aggregate supply of labor is the horizontal sum of individuals’ labor supply p Labor supply of individuals depends on consumption-leisure choice p 20

Individual: Utility Optimization p The consumption-leisure trade-off Max U(C, L) St. time constraint: L + h = T budget constraint: C ≦ wh + V U: utility, C: consumption, L: leisure, h: working hours, T: time endowment, w: real wage rate, V: nonlabor income, p w: price of leisure, opportunity cost of leisure p Constraint combined: C ≦ w(T-L) + V p Trade-off: more h, less L, but more income and more C 21

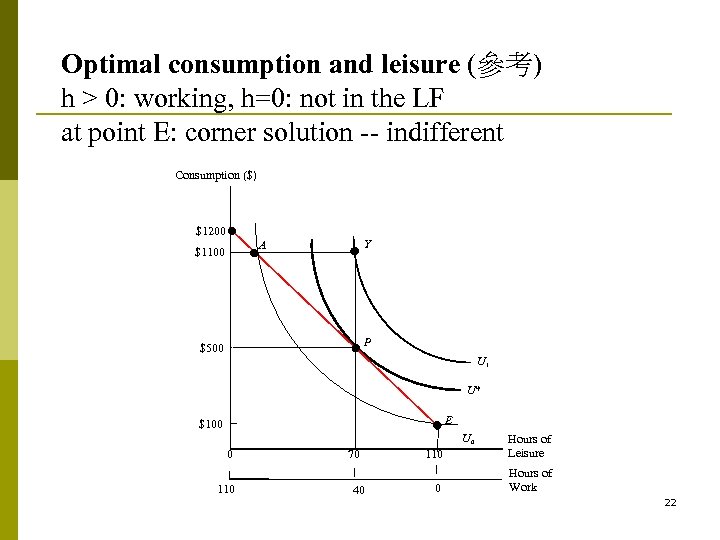

Optimal consumption and leisure (參考) h > 0: working, h=0: not in the LF at point E: corner solution -- indifferent Consumption ($) $1200 Y A $1100 P $500 U 1 U* E $100 U 0 0 110 70 40 110 Hours of Leisure 0 Hours of Work 22

A pure income effect (IE): V↑ Winning a lottery : V↑ n A pure income effect: Demand for normal goods increase: C↑, L↑ p Winning the lottery: no SE because it doesn’t affect the reward for working n p L↑=> h↓ 23

An increase in real wages: w↑ An increase in the real wage : w↑ p Substitution effect (SE): w↑: price of leisure ↑ Use cheaper C to substitute more costly L => C↑, L↓ => h↑ p Income effect (IE): w↑for same h => income ↑ => C↑, L ↑ => h ↓ p w↑total effect: has offsetting IE and SE h ↑ if SE > IE h ↓ if SE < IE p 24

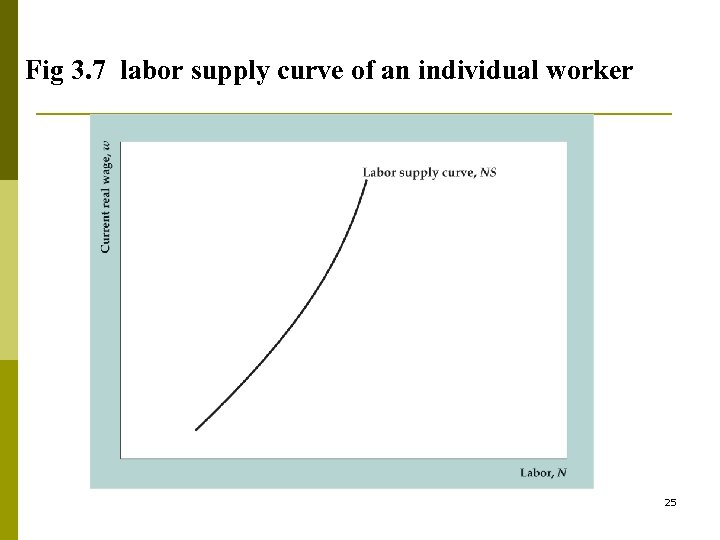

Fig 3. 7 labor supply curve of an individual worker 25

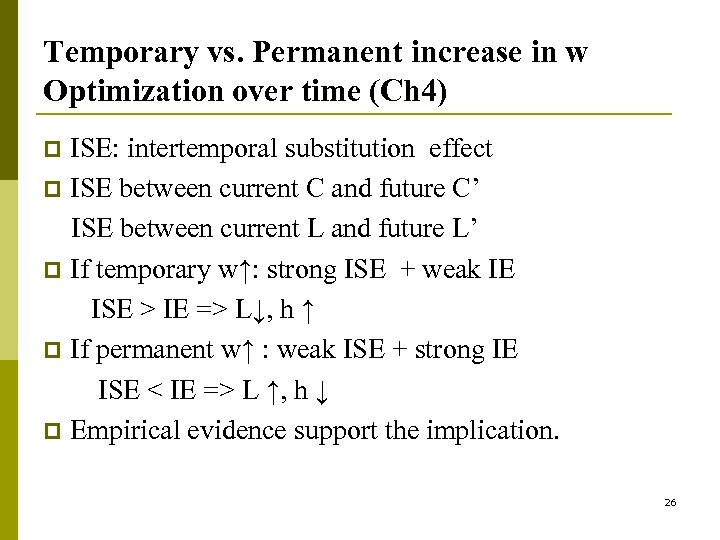

Temporary vs. Permanent increase in w Optimization over time (Ch 4) ISE: intertemporal substitution effect p ISE between current C and future C’ ISE between current L and future L’ p If temporary w↑: strong ISE + weak IE ISE > IE => L↓, h ↑ p If permanent w↑ : weak ISE + strong IE ISE < IE => L ↑, h ↓ p Empirical evidence support the implication. p 26

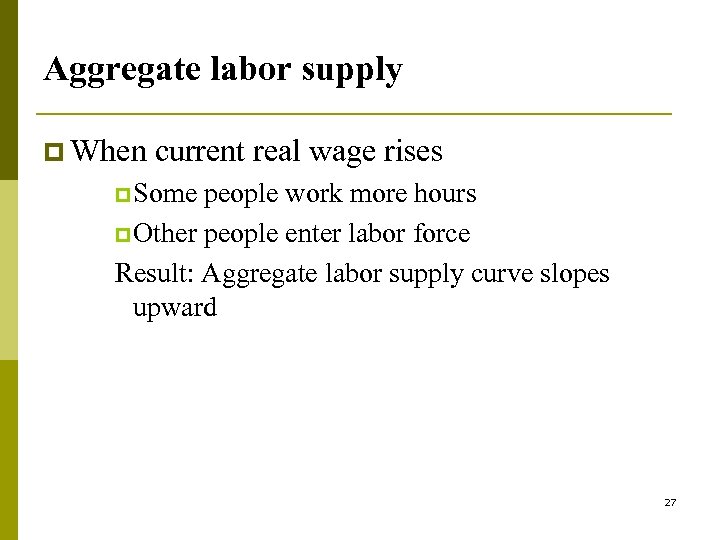

Aggregate labor supply p When current real wage rises p Some people work more hours p Other people enter labor force Result: Aggregate labor supply curve slopes upward 27

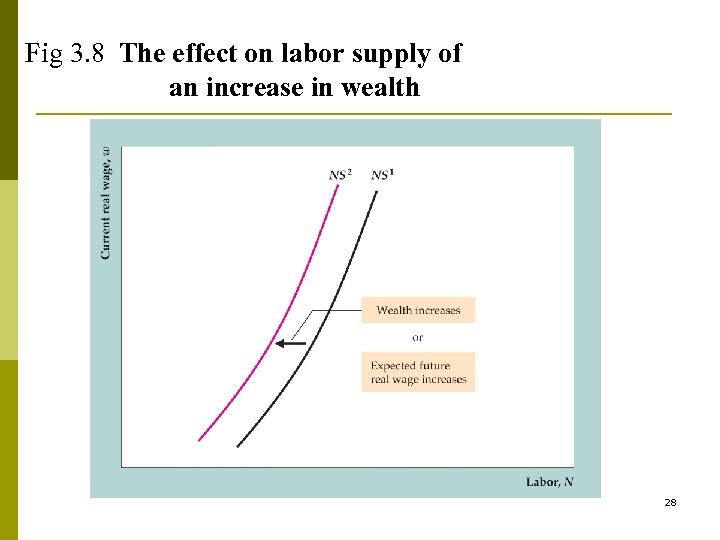

Fig 3. 8 The effect on labor supply of an increase in wealth 28

Factors that shifts aggregate labor supply n Factors increasing labor supply p Decrease in wealth p Decrease in expected future real wage p Increase in working-age population (higher birth rate, immigration) p Increase in labor force participation (increased female labor participation, elimination of mandatory retirement) 29

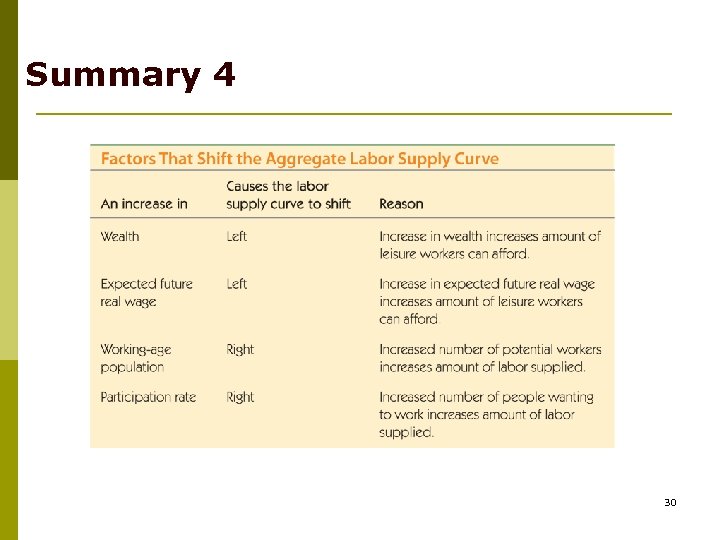

Summary 4 30

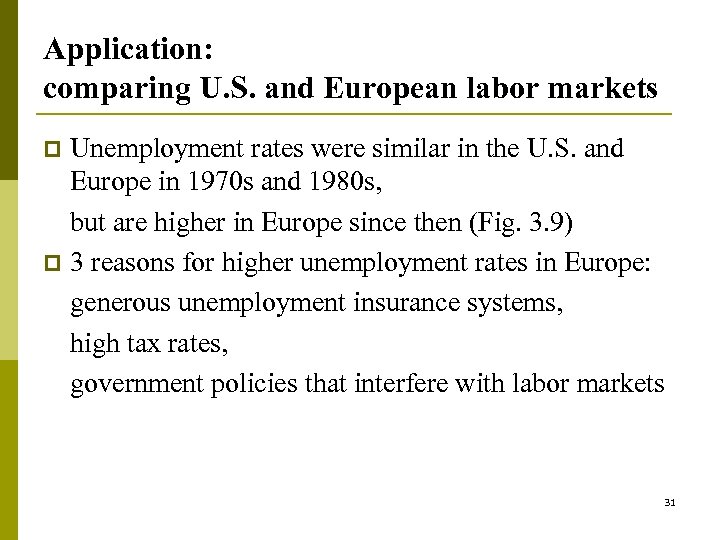

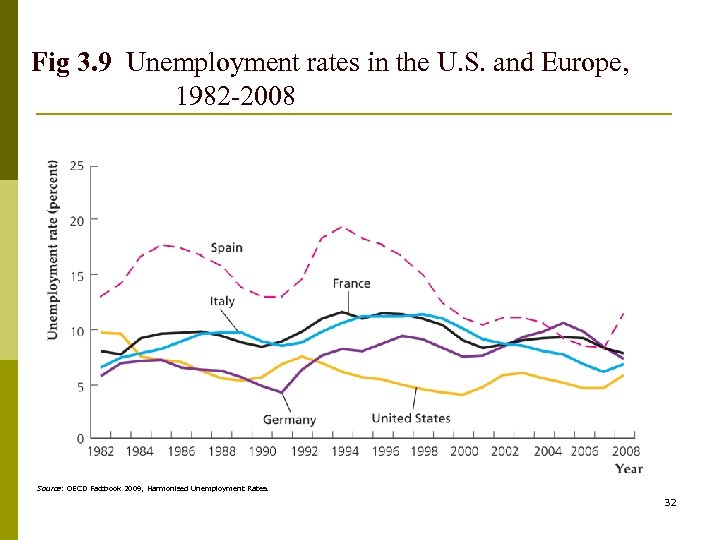

Application: comparing U. S. and European labor markets Unemployment rates were similar in the U. S. and Europe in 1970 s and 1980 s, but are higher in Europe since then (Fig. 3. 9) p 3 reasons for higher unemployment rates in Europe: generous unemployment insurance systems, high tax rates, government policies that interfere with labor markets p 31

Fig 3. 9 Unemployment rates in the U. S. and Europe, 1982 -2008 Source: OECD Factbook 2009, Harmonised Unemployment Rates. 32

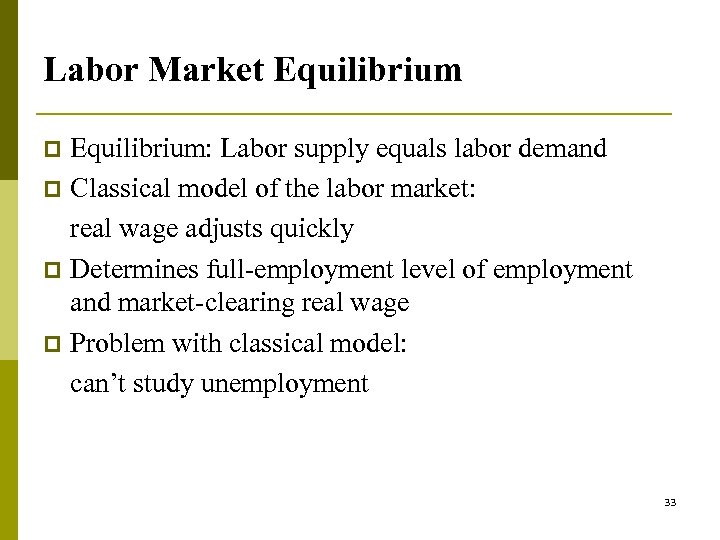

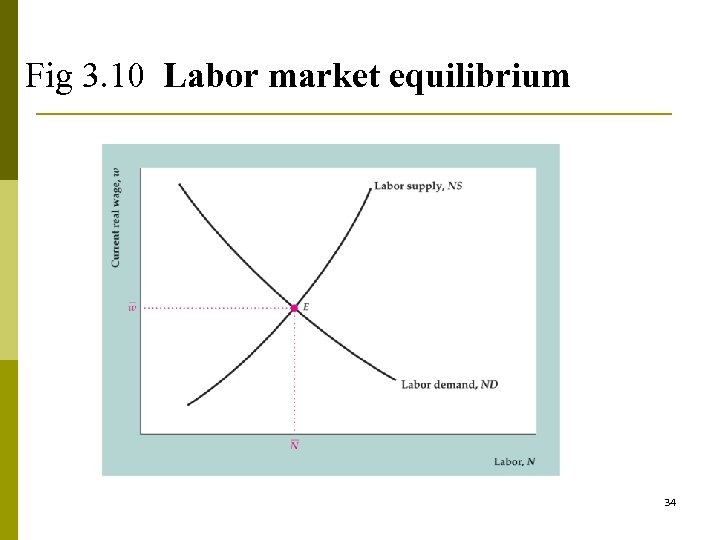

Labor Market Equilibrium: Labor supply equals labor demand p Classical model of the labor market: real wage adjusts quickly p Determines full-employment level of employment and market-clearing real wage p Problem with classical model: can’t study unemployment p 33

Fig 3. 10 Labor market equilibrium 34

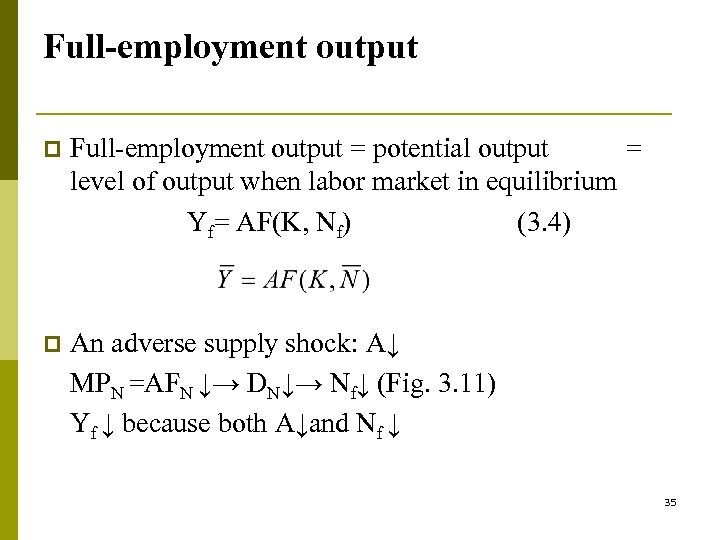

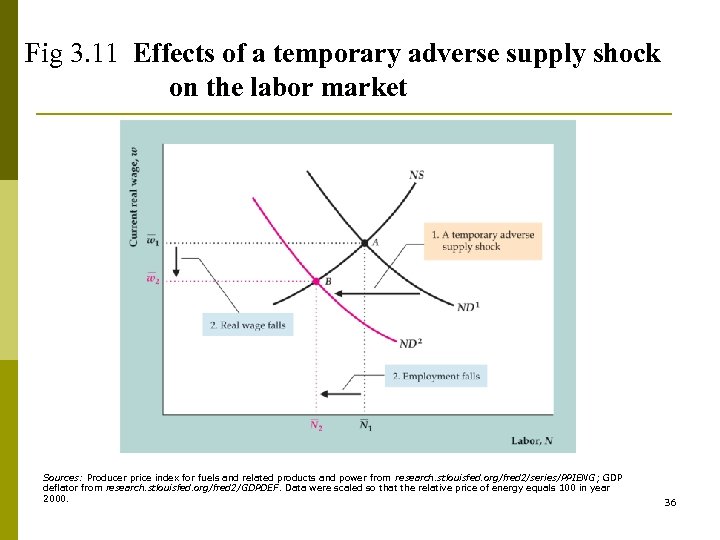

Full-employment output p Full-employment output = potential output = level of output when labor market in equilibrium Yf= AF(K, Nf) (3. 4) p An adverse supply shock: A↓ MPN =AFN ↓→ DN↓→ Nf↓ (Fig. 3. 11) Yf ↓ because both A↓and Nf ↓ 35

Fig 3. 11 Effects of a temporary adverse supply shock on the labor market Sources: Producer price index for fuels and related products and power from research. stlouisfed. org/fred 2/series/PPIENG ; GDP deflator from research. stlouisfed. org/fred 2/GDPDEF. Data were scaled so that the relative price of energy equals 100 in year 2000. 36

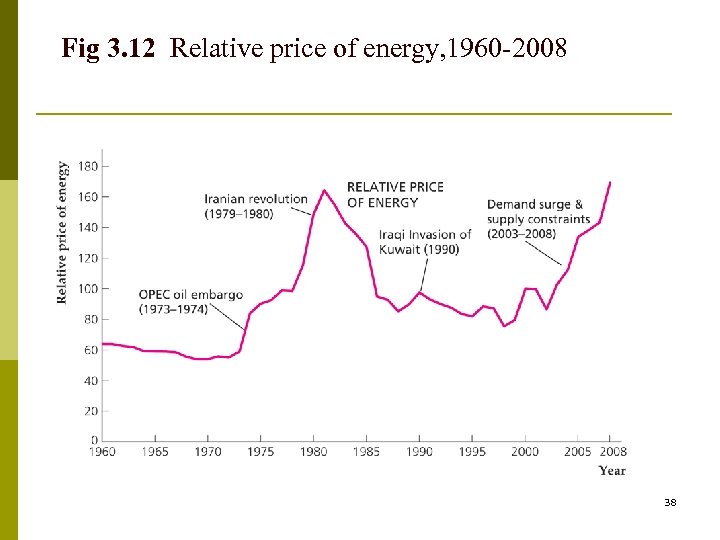

Application: output, employment, and the real wage during oil price shocks p Sharp oil price increases in 1973– 1974, 1979– 1980, 2003– 2008 (Fig. 3. 12) n Adverse supply shock—lowers labor demand, employment, the real wage, and the fullemployment level of output n First two cases: U. S. economy entered recessions n Research result: 10% increase in price of oil reduces GDP by 0. 4 percentage points 37

Fig 3. 12 Relative price of energy, 1960 -2008 38

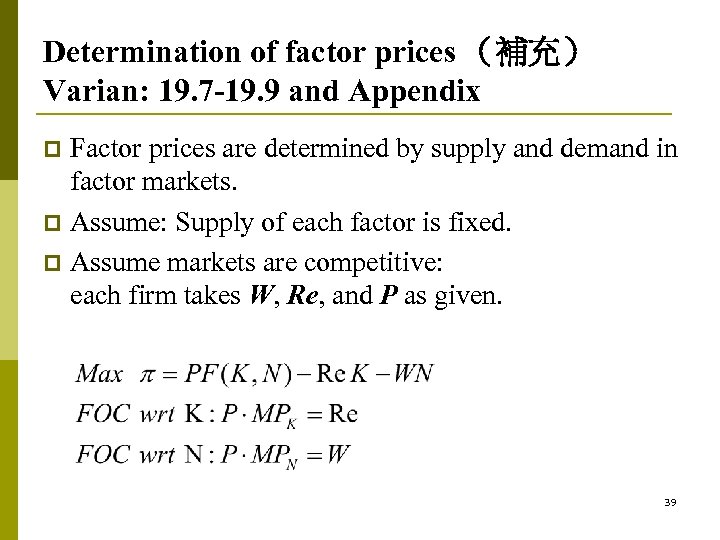

Determination of factor prices (補充) Varian: 19. 7 -19. 9 and Appendix Factor prices are determined by supply and demand in factor markets. p Assume: Supply of each factor is fixed. p Assume markets are competitive: each firm takes W, Re, and P as given. p 39

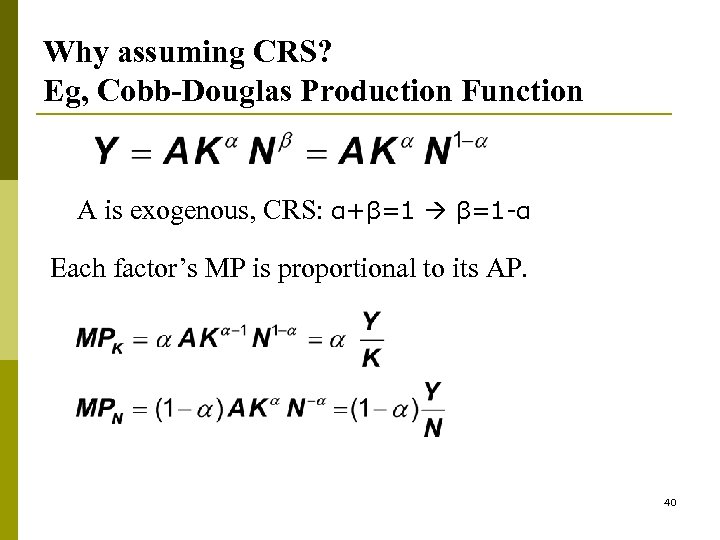

Why assuming CRS? Eg, Cobb-Douglas Production Function A is exogenous, CRS: α+β=1 β=1 -α Each factor’s MP is proportional to its AP. 40

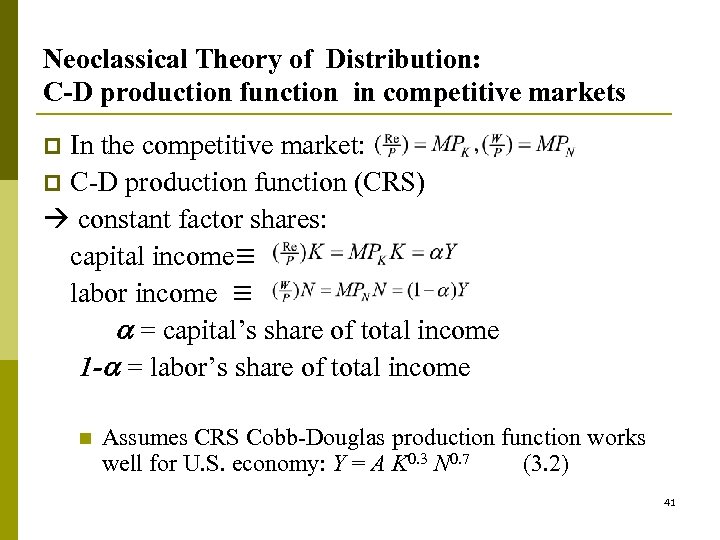

Neoclassical Theory of Distribution: C-D production function in competitive markets In the competitive market: p C-D production function (CRS) constant factor shares: capital income≡ labor income ≡ = capital’s share of total income 1 - = labor’s share of total income p n Assumes CRS Cobb-Douglas production function works well for U. S. economy: Y = A K 0. 3 N 0. 7 (3. 2) 41

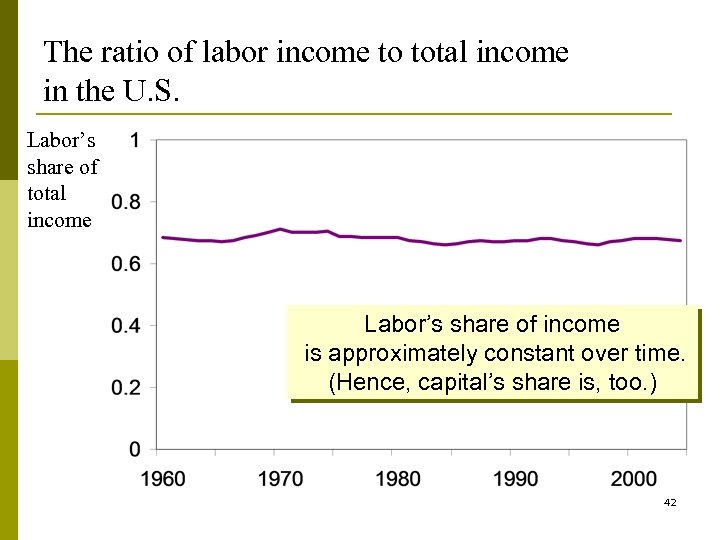

The ratio of labor income to total income in the U. S. Labor’s share of total income Labor’s share of income is approximately constant over time. (Hence, capital’s share is, too. ) 42

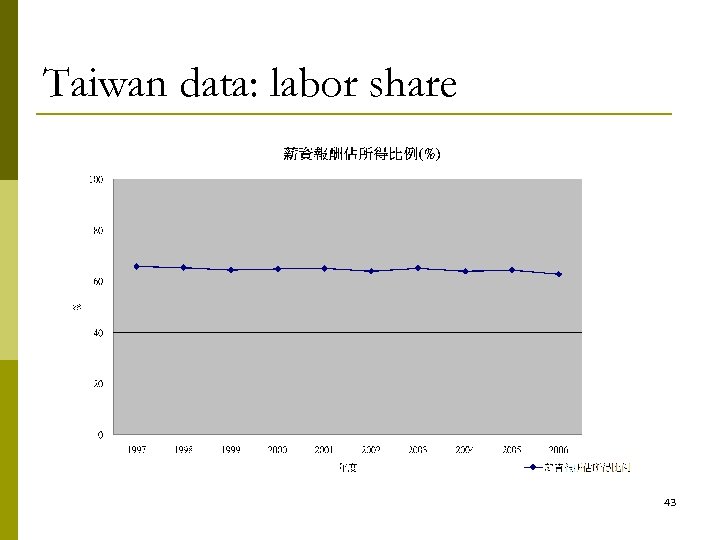

Taiwan data: labor share 43

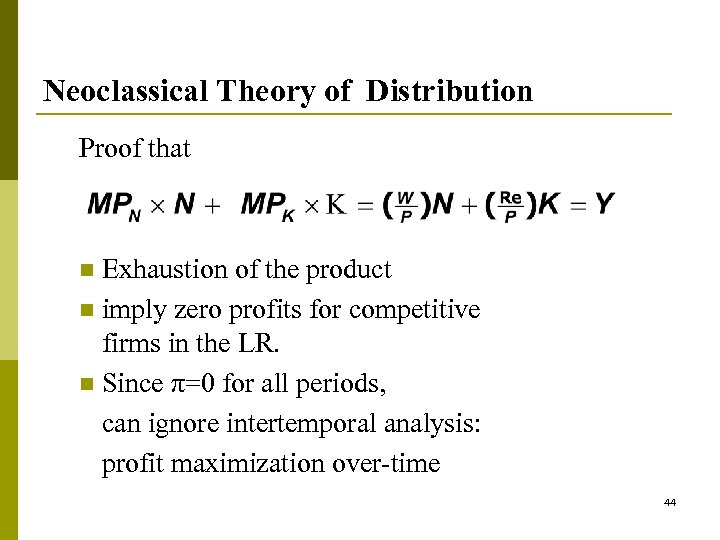

Neoclassical Theory of Distribution Proof that Exhaustion of the product n imply zero profits for competitive firms in the LR. n Since π=0 for all periods, can ignore intertemporal analysis: profit maximization over-time n 44

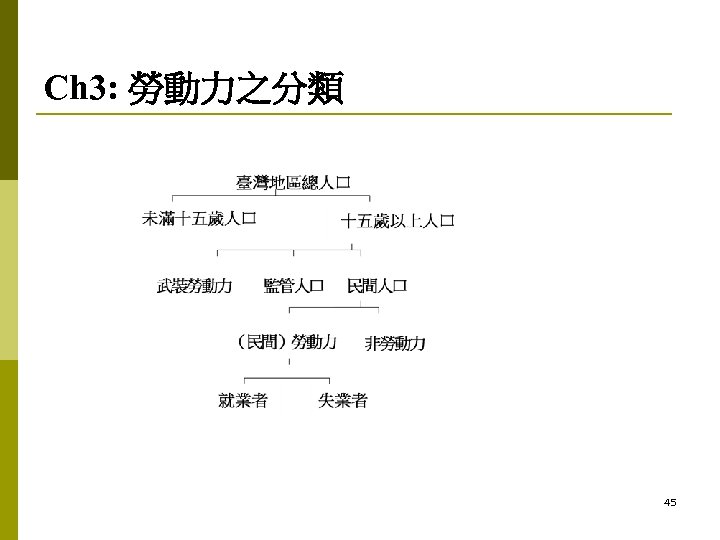

Ch 3: 勞動力之分類 45

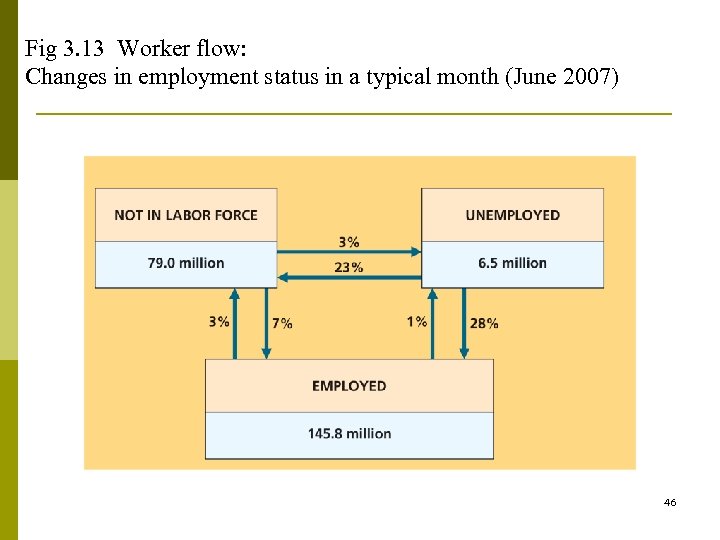

Fig 3. 13 Worker flow: Changes in employment status in a typical month (June 2007) 46

Duration of Unemployment 失業期間 Duration of unemployment (length of unemployment spell) n Most unemployment spells are of short duration n Most unemployed people on a given date are experiencing unemployment spells of long duration 47

3 types of unemployment p Frictional unemployment 摩擦性失業 Search activity of firms and workers due to heterogeneity. Matching process takes time. p Structural unemployment結構性失業 Reallocation of workers (lack of new skill) out of shrinking industries or depressed regions: matching takes a long time p Cyclical unemployment景氣性失業 48

The natural rate of unemployment p The natural rate of unemployment ( ) when output and employment are at full-employment levels n n = frictional + structural unemployment Cyclical unemployment: difference between actual unemployment rate and natural rate of unemployment, 49

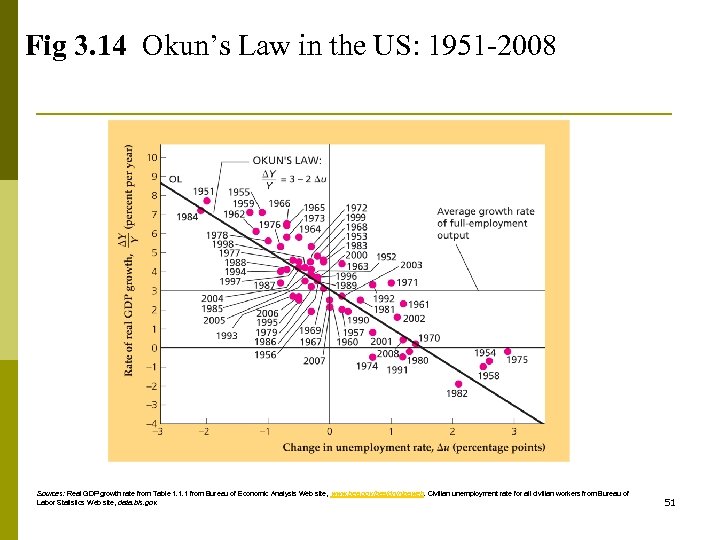

Okun’s Law: Relating Output and Unemployment p Relationship between output (relative to full-employment output) and cyclical unemployment (3. 5) Alternative formulation: if average growth rate of full-employment output is 3%: Y/Y = 3 – 2 u (3. 6) p 50

Fig 3. 14 Okun’s Law in the US: 1951 -2008 Sources: Real GDP growth rate from Table 1. 1. 1 from Bureau of Economic Analysis Web site, www. bea. gov/bea/dn/nipaweb. Civilian unemployment rate for all civilian workers from Bureau of Labor Statistics Web site, data. bls. gov. 51

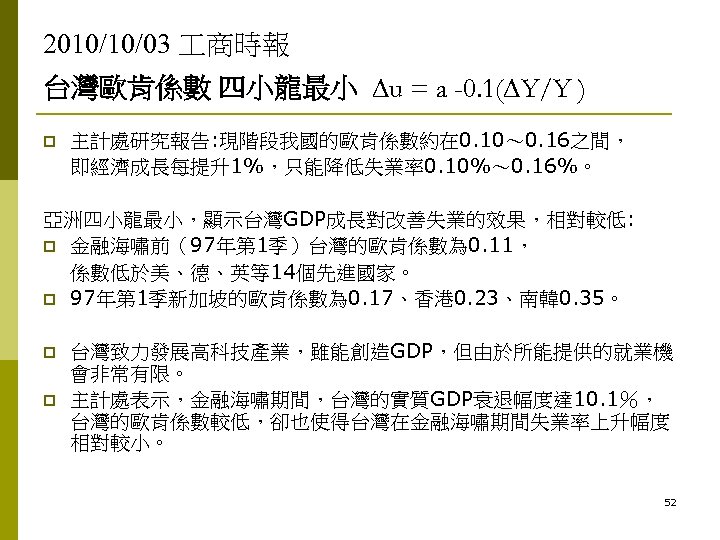

2010/10/03 商時報 台灣歐肯係數 四小龍最小 u = a -0. 1( Y/Y ) p 主計處研究報告: 現階段我國的歐肯係數約在 0. 10~ 0. 16之間, 即經濟成長每提升1%,只能降低失業率0. 10%~ 0. 16%。 亞洲四小龍最小,顯示台灣GDP成長對改善失業的效果,相對較低: p 金融海嘯前(97年第 1季)台灣的歐肯係數為 0. 11, 係數低於美、德、英等14個先進國家。 p 97年第 1季新加坡的歐肯係數為 0. 17、香港 0. 23、南韓 0. 35。 p p 台灣致力發展高科技產業,雖能創造GDP,但由於所能提供的就業機 會非常有限。 主計處表示,金融海嘯期間,台灣的實質GDP衰退幅度達 10. 1%, 台灣的歐肯係數較低,卻也使得台灣在金融海嘯期間失業率上升幅度 相對較小。 52

47f7ee882649ab1bfa3147ef89b74742.ppt