153e03a9ab7dc07a2deed79a38405afc.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 110

Ch. 2 Internet Law in Hong Kong Source : 1. Cyber-crime, The Challenge in Asia Ed. By R. Broadhurst & Peter Grabosky 2. Report on Computer Related Crime, 2001 Inter-departmental Working Group, HKSAR 3. Internet Law in Hong Kong Claire Wright, Will Mc. Auliffe, Anna Gamvros 4. http: //www. infosec. gov. hk/english/crime. html 1

Ch. 2 Internet Law in Hong Kong Source : 1. Cyber-crime, The Challenge in Asia Ed. By R. Broadhurst & Peter Grabosky 2. Report on Computer Related Crime, 2001 Inter-departmental Working Group, HKSAR 3. Internet Law in Hong Kong Claire Wright, Will Mc. Auliffe, Anna Gamvros 4. http: //www. infosec. gov. hk/english/crime. html 1

2. 1 Governance in the Digital Age Policing the Internet in Hong Kong, an Economic City v Hong Kong is an economic city, an international centre of financial and commercial flows between East and West. Its geographical location has made it a trading centre since the nineteenth century and over the years. Hong Kong people have themselves developed a reputation for their entrepreneurial skills and business savvy. Because of this, the Internet has taken root and grown in Hong Kong. v 2

2. 1 Governance in the Digital Age Policing the Internet in Hong Kong, an Economic City v Hong Kong is an economic city, an international centre of financial and commercial flows between East and West. Its geographical location has made it a trading centre since the nineteenth century and over the years. Hong Kong people have themselves developed a reputation for their entrepreneurial skills and business savvy. Because of this, the Internet has taken root and grown in Hong Kong. v 2

2. 1. 1 Public Understanding of Cyber-crime The Hong Kong media tend largely to write on the good news about new technology businesses rather than the bad. v By contrast, the UK media coverage has covered both sides of the story, cyber-entrepreneurship heroism, as well as cautionary tales of the downside of technological advancement. v As a result, stories about cyber-criminality (such as fraud and child pornography) have received a wider coverage and debate in the UK than in Hong Kong. v 3

2. 1. 1 Public Understanding of Cyber-crime The Hong Kong media tend largely to write on the good news about new technology businesses rather than the bad. v By contrast, the UK media coverage has covered both sides of the story, cyber-entrepreneurship heroism, as well as cautionary tales of the downside of technological advancement. v As a result, stories about cyber-criminality (such as fraud and child pornography) have received a wider coverage and debate in the UK than in Hong Kong. v 3

2. 1. 1 Public Understanding of Cyber-crime There a number of factors contributing to this absence of a Hong Kong discourse on the darker side of the Internet. One is the Hong Kong press. The Hong Kong media are primarily market-driven, reflecting the culture and ethos of the society. This is the result of the corporatization of many local newspaper. v A few of the most popular Chinese language newspapers now dominate the market and set the rules of the game. They have been able to exert immense influence over matters such as output 4 level, technology, and styles of news reporting. v

2. 1. 1 Public Understanding of Cyber-crime There a number of factors contributing to this absence of a Hong Kong discourse on the darker side of the Internet. One is the Hong Kong press. The Hong Kong media are primarily market-driven, reflecting the culture and ethos of the society. This is the result of the corporatization of many local newspaper. v A few of the most popular Chinese language newspapers now dominate the market and set the rules of the game. They have been able to exert immense influence over matters such as output 4 level, technology, and styles of news reporting. v

2. 1. 1 Public Understanding of Cyber-crime Bureaucratic controls of the press in HK have been weak, partly because of the government’s laissezfaire policy but also because control of the press raises issues of political censorship to which the HK public (esp. after 1997) is sensitive. v Another factor for the relative lack of serious investigative journalism in HK is that, HK had been a British colony for 154 years until its sovereignty reverted to Mainland China on 1 July 1997. Most citizens in Hong Kong have their normative orientation living in Hong Kong as a short term and materialistic, valuing social stability above political participation and securing their families’ longerterm futures. 5 v

2. 1. 1 Public Understanding of Cyber-crime Bureaucratic controls of the press in HK have been weak, partly because of the government’s laissezfaire policy but also because control of the press raises issues of political censorship to which the HK public (esp. after 1997) is sensitive. v Another factor for the relative lack of serious investigative journalism in HK is that, HK had been a British colony for 154 years until its sovereignty reverted to Mainland China on 1 July 1997. Most citizens in Hong Kong have their normative orientation living in Hong Kong as a short term and materialistic, valuing social stability above political participation and securing their families’ longerterm futures. 5 v

2. 1. 1 Public Understanding of Cyber-crime One legacy has been the lack of lively public debate around controversial issues. Thus while the character of the media discourages critical journalism of the Internet, this civic apathy discourages public debate about such issues as the Internet and its impact on public and private life. v Public understanding of cyber-crime is limited and discussion of how it should be policed is virtually non-exist. v 6

2. 1. 1 Public Understanding of Cyber-crime One legacy has been the lack of lively public debate around controversial issues. Thus while the character of the media discourages critical journalism of the Internet, this civic apathy discourages public debate about such issues as the Internet and its impact on public and private life. v Public understanding of cyber-crime is limited and discussion of how it should be policed is virtually non-exist. v 6

2. 1. 2 Understanding the impact of cyber-crime In Hong Kong the media provided ad hoc reports on cyber-crime from time to time but responses to these reports vary, from major to little or no reaction. The strongest reaction has tended to come from the publicly funded police organization (HK Police) and a few politicians. There is also little or no response from academia, and even less from the established civic pressure groups. Almost no debate has been taking place in public. v Local understanding of the impact of cyber-crime is fairly shallow. Viewpoints are very often limited to brief reports about privacy issues. . v 7

2. 1. 2 Understanding the impact of cyber-crime In Hong Kong the media provided ad hoc reports on cyber-crime from time to time but responses to these reports vary, from major to little or no reaction. The strongest reaction has tended to come from the publicly funded police organization (HK Police) and a few politicians. There is also little or no response from academia, and even less from the established civic pressure groups. Almost no debate has been taking place in public. v Local understanding of the impact of cyber-crime is fairly shallow. Viewpoints are very often limited to brief reports about privacy issues. . v 7

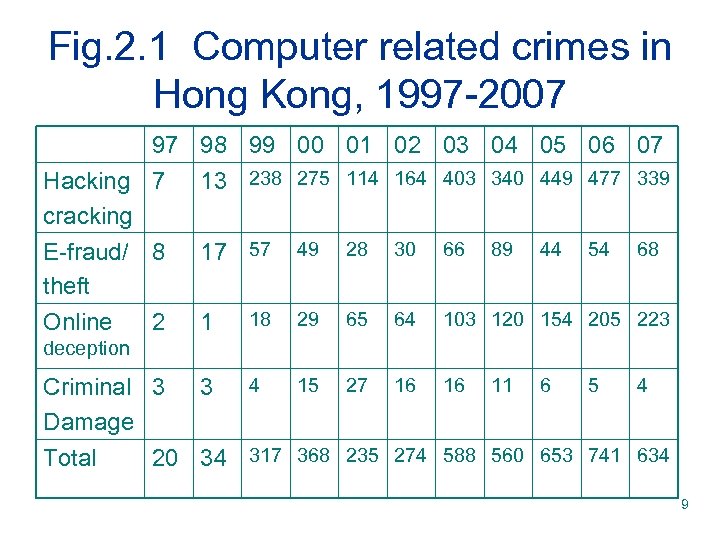

2. 1. 2 Understanding the impact of cyber-crime This is not because HK has no cyber-crime. v Internet virus/ intrusion, illegal Internet gambling, hacking / cracking (unauthorized access to a computer with criminal or dishonest intent) and the like form the majority of computer-related crimes reported to the police in Hong Kong. v Fig. 2. 1 shows the statistic reported by HKP v 8

2. 1. 2 Understanding the impact of cyber-crime This is not because HK has no cyber-crime. v Internet virus/ intrusion, illegal Internet gambling, hacking / cracking (unauthorized access to a computer with criminal or dishonest intent) and the like form the majority of computer-related crimes reported to the police in Hong Kong. v Fig. 2. 1 shows the statistic reported by HKP v 8

Fig. 2. 1 Computer related crimes in Hong Kong, 1997 -2007 97 98 99 00 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 Hacking 7 cracking E-fraud/ 8 theft 13 238 275 114 164 403 340 449 477 339 Online 1 2 17 57 49 28 30 66 89 44 54 68 18 29 65 64 103 120 154 205 223 deception 15 27 16 16 11 6 5 4 Criminal 3 3 4 Damage Total 20 34 317 368 235 274 588 560 653 741 634 9

Fig. 2. 1 Computer related crimes in Hong Kong, 1997 -2007 97 98 99 00 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 Hacking 7 cracking E-fraud/ 8 theft 13 238 275 114 164 403 340 449 477 339 Online 1 2 17 57 49 28 30 66 89 44 54 68 18 29 65 64 103 120 154 205 223 deception 15 27 16 16 11 6 5 4 Criminal 3 3 4 Damage Total 20 34 317 368 235 274 588 560 653 741 634 9

2. 1. 2 Understanding the impact of cybercrime The upward trend of cases of online deception is obvious, from 2 cases in 1997 to 223 in 2007. Although such as an increase is no crime wave, the key point is that it has drawn little or no analysis, perhaps because criminological research in HK is still in its infancy. There is little indigenous research on computer crime, Internet governance and regulation in HK. v Only in 1999 did the HKU establish a Centre for Criminology to promote and coordinate indigenous studies of crime and crime justice. v 10

2. 1. 2 Understanding the impact of cybercrime The upward trend of cases of online deception is obvious, from 2 cases in 1997 to 223 in 2007. Although such as an increase is no crime wave, the key point is that it has drawn little or no analysis, perhaps because criminological research in HK is still in its infancy. There is little indigenous research on computer crime, Internet governance and regulation in HK. v Only in 1999 did the HKU establish a Centre for Criminology to promote and coordinate indigenous studies of crime and crime justice. v 10

2. 1. 2 Understanding the impact of cybercrime There are two perspectives to view cyber crime : v (1) From a criminological perspective and v (2) from the computer security perspective. v 11

2. 1. 2 Understanding the impact of cybercrime There are two perspectives to view cyber crime : v (1) From a criminological perspective and v (2) from the computer security perspective. v 11

2. 1. 3 Electronic governance in Hong Kong v v v The three prevailing principles grasped the HKSAR government are : 1. a free trading port, 2. maintain stability and prosperity, and 3. a follower of global trend. In many ways, Hong Kong Internet governance mirrors its administrative governance. In the beginning, the desire to exercise control over the Internet came from the commercial sector rather than the government. The government primarily adopted a laissez-faire attitude, unless a potential risk was perceived to threaten social order and merited government intervention. This policy on the Internet is in line with the government’s overall governing principle of laissez-faire and in the maintenance of HK’s free trade port status. 12

2. 1. 3 Electronic governance in Hong Kong v v v The three prevailing principles grasped the HKSAR government are : 1. a free trading port, 2. maintain stability and prosperity, and 3. a follower of global trend. In many ways, Hong Kong Internet governance mirrors its administrative governance. In the beginning, the desire to exercise control over the Internet came from the commercial sector rather than the government. The government primarily adopted a laissez-faire attitude, unless a potential risk was perceived to threaten social order and merited government intervention. This policy on the Internet is in line with the government’s overall governing principle of laissez-faire and in the maintenance of HK’s free trade port status. 12

2. 1. 3 Electronic governance in Hong Kong Gradually, as the Internet has grown, the government has come to see it as a source of prosperity on the one hand, and a potential threat to law and order on the other. As a result, the HK government has sought to control the Internet via legislative and regulatory measures. v HK is largely a follower of global trends, partly because it has never been exercised as a major political power and partly because of its small size and position as a former colony. HK government has incorporated existing international rules on Internet governance and introduced compulsory licensing for HK ISPs. v 13

2. 1. 3 Electronic governance in Hong Kong Gradually, as the Internet has grown, the government has come to see it as a source of prosperity on the one hand, and a potential threat to law and order on the other. As a result, the HK government has sought to control the Internet via legislative and regulatory measures. v HK is largely a follower of global trends, partly because it has never been exercised as a major political power and partly because of its small size and position as a former colony. HK government has incorporated existing international rules on Internet governance and introduced compulsory licensing for HK ISPs. v 13

2. 1. 3 Electronic governance in Hong Kong v The first HK government policy document on IT (“Digital 21 Information Technology”) in 1998 did state that ‘the government is committed to enhancing the community’s awareness and knowledge of IT, promoting the wider use of IT in the community and improving public access to online services. ’ http: //www. info. gov. hk/digital 21/eng/D 21 SAC/if. htm v The HK government saw its job as no more than promoting the use of IT within the community from a distance. The idea that it might play a bigger role in the setting of international technical, commercial and legal standards has largely been ignored. 14

2. 1. 3 Electronic governance in Hong Kong v The first HK government policy document on IT (“Digital 21 Information Technology”) in 1998 did state that ‘the government is committed to enhancing the community’s awareness and knowledge of IT, promoting the wider use of IT in the community and improving public access to online services. ’ http: //www. info. gov. hk/digital 21/eng/D 21 SAC/if. htm v The HK government saw its job as no more than promoting the use of IT within the community from a distance. The idea that it might play a bigger role in the setting of international technical, commercial and legal standards has largely been ignored. 14

2. 1. 3 Electronic governance in Hong Kong v Again, in the latest policy consultation paper (‘ 2004 Digital 21 Strategy’), the emphasis is on how the HK government can be a good middleman or a facilitator: ‘Our conviction is that the government should be an effective facilitator to enhance the innovative capability of both industry and the community, promote the development of industry and enterprises and, in this process, encourage investment and innovation in IT. ’ What is missing is any overall strategy for integrating the Internet and IT. Thus, by default, governance is left to the Internet and IT industries themselves – in other words, self-regulation. 15

2. 1. 3 Electronic governance in Hong Kong v Again, in the latest policy consultation paper (‘ 2004 Digital 21 Strategy’), the emphasis is on how the HK government can be a good middleman or a facilitator: ‘Our conviction is that the government should be an effective facilitator to enhance the innovative capability of both industry and the community, promote the development of industry and enterprises and, in this process, encourage investment and innovation in IT. ’ What is missing is any overall strategy for integrating the Internet and IT. Thus, by default, governance is left to the Internet and IT industries themselves – in other words, self-regulation. 15

2. 1. 3 Electronic governance in Hong Kong There are several key ordinances but most of them deal with cyber-crime by adapting existing laws to the cyber-age, rather than by drafting new legislation specifically designed to police the Internet. The exception is the Electronic Transactions Ordinance (Cap. 553) which deals with electronic commerce. This ordinance is largely regarded as a means of facilitating the HK Post Office’s electronic certificate and electronic surveillance. v The most important ordinance is the Computer Crimes Ordinance introduced in 1993. It is composed of several different ordinances, including the Telecommunication Ordinance (Cap. 210). v 16

2. 1. 3 Electronic governance in Hong Kong There are several key ordinances but most of them deal with cyber-crime by adapting existing laws to the cyber-age, rather than by drafting new legislation specifically designed to police the Internet. The exception is the Electronic Transactions Ordinance (Cap. 553) which deals with electronic commerce. This ordinance is largely regarded as a means of facilitating the HK Post Office’s electronic certificate and electronic surveillance. v The most important ordinance is the Computer Crimes Ordinance introduced in 1993. It is composed of several different ordinances, including the Telecommunication Ordinance (Cap. 210). v 16

2. 1. 3 Electronic governance in Hong Kong v In the late 1990 s, other legislation was amended to embrace the advancement of Internet technology including the Copyright Ordinance (Cap. 528), pertaining to illegal copies of Internet material; the Control of Obscene and Indecent Articles Ordinance (Cap. 390) concerning the distribution of pornographic material on the Internet; and the Gambling Ordinance (Cap. 148), which prohibits gambling on the Internet other than under the auspices of the HK Jockey Club. 17

2. 1. 3 Electronic governance in Hong Kong v In the late 1990 s, other legislation was amended to embrace the advancement of Internet technology including the Copyright Ordinance (Cap. 528), pertaining to illegal copies of Internet material; the Control of Obscene and Indecent Articles Ordinance (Cap. 390) concerning the distribution of pornographic material on the Internet; and the Gambling Ordinance (Cap. 148), which prohibits gambling on the Internet other than under the auspices of the HK Jockey Club. 17

2. 1. 3 Electronic governance in Hong Kong Lastly, the Personal Data (Privacy) Ordinance (Cap. 468) was introduced in 1996 and became law the same year. This ordinance is not specifically designed for the Internet but it does cover personal data held in a computer system as a record, as well as other types of traditional records such as those on paper. v The HK government has also established the office of Privacy Commissioner for Personal Data, a statutory body entrusted with the task of protecting the personal data privacy of individuals and ensuring compliance with the Privacy Ordinance. The HK Privacy Law operates as a semi-regulatory 18 regime. v

2. 1. 3 Electronic governance in Hong Kong Lastly, the Personal Data (Privacy) Ordinance (Cap. 468) was introduced in 1996 and became law the same year. This ordinance is not specifically designed for the Internet but it does cover personal data held in a computer system as a record, as well as other types of traditional records such as those on paper. v The HK government has also established the office of Privacy Commissioner for Personal Data, a statutory body entrusted with the task of protecting the personal data privacy of individuals and ensuring compliance with the Privacy Ordinance. The HK Privacy Law operates as a semi-regulatory 18 regime. v

2. 1. 3 Electronic governance in Hong Kong The above ordinances form the key components of electronic governance in HK. They confer on the publicly funded regulatory agencies (including the police) the authority to act, maintain law and order and control crime in cyberspace. But still, the policing of cyberspace is not a high priority of HK government. v Five main groups v Ø 1. Ø 2. Ø 3. Ø 4. Ø 5. Internet users and Internet user group; Internet service providers, Private Police Agencies State-funded non-public police organization, State funded police organization 19

2. 1. 3 Electronic governance in Hong Kong The above ordinances form the key components of electronic governance in HK. They confer on the publicly funded regulatory agencies (including the police) the authority to act, maintain law and order and control crime in cyberspace. But still, the policing of cyberspace is not a high priority of HK government. v Five main groups v Ø 1. Ø 2. Ø 3. Ø 4. Ø 5. Internet users and Internet user group; Internet service providers, Private Police Agencies State-funded non-public police organization, State funded police organization 19

2. 1. 4 Internet Users and User Groups in HK v These five groups police cyberspace by maintaining various types and levels of order. They form a multi-tiered structure of governance within cyberspace. It progresses from maintaining order to the enforcement of law. 20

2. 1. 4 Internet Users and User Groups in HK v These five groups police cyberspace by maintaining various types and levels of order. They form a multi-tiered structure of governance within cyberspace. It progresses from maintaining order to the enforcement of law. 20

2. 1. 4 Internet Users and User Groups in HK (1) Internet users and user groups v Theoretically this is the largest group of individuals exercising control over cyberspace. Because of the culture and social norms of HK, Internet users and user groups have little power or influence and are rarely engaged in policing the Internet. v For example, the HK Linux User Group and HK Telecommunications User Group are forums for the dissemination of information and simply share experience, they are not a proactive lobby or pressure group that issues political statements in an attempt to influence the lawmaking process or win public support. v 21

2. 1. 4 Internet Users and User Groups in HK (1) Internet users and user groups v Theoretically this is the largest group of individuals exercising control over cyberspace. Because of the culture and social norms of HK, Internet users and user groups have little power or influence and are rarely engaged in policing the Internet. v For example, the HK Linux User Group and HK Telecommunications User Group are forums for the dissemination of information and simply share experience, they are not a proactive lobby or pressure group that issues political statements in an attempt to influence the lawmaking process or win public support. v 21

2. 1. 4 Internet Users and User Groups in HK (1) Internet users and user groups v In HK, individual and family interests are valued above societal or collective interests. Social aloofness and political passivity are deeply rooted. The fact that HK people are excluded from politics by this absence of democracy reinforces such social values. In terms of political participation and civic duties, the HK Chinese do not believe that an individual or group will have any impact on the decision-making process. Adaptation rather than active intervention thus becomes the guiding principle of their relationship with the government. v 22

2. 1. 4 Internet Users and User Groups in HK (1) Internet users and user groups v In HK, individual and family interests are valued above societal or collective interests. Social aloofness and political passivity are deeply rooted. The fact that HK people are excluded from politics by this absence of democracy reinforces such social values. In terms of political participation and civic duties, the HK Chinese do not believe that an individual or group will have any impact on the decision-making process. Adaptation rather than active intervention thus becomes the guiding principle of their relationship with the government. v 22

2. 1. 4 Internet Users and User Groups in HK (2) Internet service providers v The position of ISPs is rather fluid. While they are physically located in one particular jurisdiction, they have a transnational function. v There is an Internet Service Provider Association set up by the industry, it largely provides a forum for discussion, promotes the development of the industry and protects members’ interests, and provides and maintains Codes of Practice for ISP members. v 23

2. 1. 4 Internet Users and User Groups in HK (2) Internet service providers v The position of ISPs is rather fluid. While they are physically located in one particular jurisdiction, they have a transnational function. v There is an Internet Service Provider Association set up by the industry, it largely provides a forum for discussion, promotes the development of the industry and protects members’ interests, and provides and maintains Codes of Practice for ISP members. v 23

2. 1. 4 Internet Users and User Groups in HK v v (3) Private Police Agencies With the wide spread growth of Internet commerce in the late 1990 s in HK, organizations such as computer consultants and large management consulting firms sought to expand their business. They gradually become involved in the investigation of security problems and the policing of cyberspace. The scope of these firms mainly falls into 4 categories : 1. anti-fraud work: mainly for insurance, including factual and surveillance work 2. legal work: background and factual work for lawyers in civil and criminal cases. 3. commercial inquiry: companies hiring investigations to carry out various tasks, such as debugging, liability investigations, workplace investigations into theft or harassment and pre-employment checks 4. domestic investigations 24

2. 1. 4 Internet Users and User Groups in HK v v (3) Private Police Agencies With the wide spread growth of Internet commerce in the late 1990 s in HK, organizations such as computer consultants and large management consulting firms sought to expand their business. They gradually become involved in the investigation of security problems and the policing of cyberspace. The scope of these firms mainly falls into 4 categories : 1. anti-fraud work: mainly for insurance, including factual and surveillance work 2. legal work: background and factual work for lawyers in civil and criminal cases. 3. commercial inquiry: companies hiring investigations to carry out various tasks, such as debugging, liability investigations, workplace investigations into theft or harassment and pre-employment checks 4. domestic investigations 24

2. 1. 4 Internet Users and User Groups in HK (3) Private Police Agencies v The work of these agencies often duplicates or supplements the work of the HK Police Technology Crime Division, especially in areas related to computer forensics and investigation. Nonetheless, their importance cannot be underestimated in taming cyber crimes, especially in the trans-border dimension. v However, private police activity in computer investigative work is considered extensive and likely to grow, in particular, on the civil litigation side. This is mostly of a proactive and preventive kind, with a focus on prevention and to protection of property, whereas the HKP focus more on determine and criminal investigation. 25 v

2. 1. 4 Internet Users and User Groups in HK (3) Private Police Agencies v The work of these agencies often duplicates or supplements the work of the HK Police Technology Crime Division, especially in areas related to computer forensics and investigation. Nonetheless, their importance cannot be underestimated in taming cyber crimes, especially in the trans-border dimension. v However, private police activity in computer investigative work is considered extensive and likely to grow, in particular, on the civil litigation side. This is mostly of a proactive and preventive kind, with a focus on prevention and to protection of property, whereas the HKP focus more on determine and criminal investigation. 25 v

2. 1. 4 Internet Users and User Groups in HK v (3) Private Police Agencies v As an important financial and commercial centre, there is a need for organizations to handle Internet-related fraud cases in a cost-effective manner. Private policing is already playing a substantial role in the territory, in particular in providing surveillance of private property and security guard services at warehouses, shopping malls, and housing estates. As a result, the business sector is open to the idea of private policing and its role in servicing industries’ security needs. 26

2. 1. 4 Internet Users and User Groups in HK v (3) Private Police Agencies v As an important financial and commercial centre, there is a need for organizations to handle Internet-related fraud cases in a cost-effective manner. Private policing is already playing a substantial role in the territory, in particular in providing surveillance of private property and security guard services at warehouses, shopping malls, and housing estates. As a result, the business sector is open to the idea of private policing and its role in servicing industries’ security needs. 26

2. 1. 4 Internet Users and User Groups in HK (4) State-funded, non-public police organizations v The next level of response to Internet crimes in HK comes from government agencies. In HK, there is only one hybrid organization, the Hong Kong Computer Emergency Response Team Co-ordination Centre (HKCERT/CC) funded by the HK government and located at the Hong Kong Productivity Council. The objective and function of HKCERT/CC is to provide a centralized 24/7 reporting contact on computer and network security. It also responds to local enterprises and Internet users in case of security, particularly malicious code incidents. It coordinates response and recovery actions for reported incidents to help monitor and disseminate information on security related issues. 27 v

2. 1. 4 Internet Users and User Groups in HK (4) State-funded, non-public police organizations v The next level of response to Internet crimes in HK comes from government agencies. In HK, there is only one hybrid organization, the Hong Kong Computer Emergency Response Team Co-ordination Centre (HKCERT/CC) funded by the HK government and located at the Hong Kong Productivity Council. The objective and function of HKCERT/CC is to provide a centralized 24/7 reporting contact on computer and network security. It also responds to local enterprises and Internet users in case of security, particularly malicious code incidents. It coordinates response and recovery actions for reported incidents to help monitor and disseminate information on security related issues. 27 v

2. 1. 4 Internet Users and User Groups in HK v v (5) State-funded police The last and the strongest group of organizations involved in policing cyberspace in HK is the state-funded public police. The HKP is one of the world’s largest urban police forces, with one police officer for every 244 citizens. In addition to the main body of officers in the HKP, the Immigration Department, the Independent Commission Against Corruption (ICAC) and the Customs and Excise Department all have a role in policing the Internet from the perspective of their own legislative mandates. With regard to computer crimes, there are several specialist groups within the police with an interest in the Internet. For example, in HK, a computer crime unit (now the Technology Crime Division) has been set up to investigate broad issues of Internet-related crime. 28

2. 1. 4 Internet Users and User Groups in HK v v (5) State-funded police The last and the strongest group of organizations involved in policing cyberspace in HK is the state-funded public police. The HKP is one of the world’s largest urban police forces, with one police officer for every 244 citizens. In addition to the main body of officers in the HKP, the Immigration Department, the Independent Commission Against Corruption (ICAC) and the Customs and Excise Department all have a role in policing the Internet from the perspective of their own legislative mandates. With regard to computer crimes, there are several specialist groups within the police with an interest in the Internet. For example, in HK, a computer crime unit (now the Technology Crime Division) has been set up to investigate broad issues of Internet-related crime. 28

2. 1. 4 Internet Users and User Groups in HK (5) State-funded police v However, the HKP only become involved in such matters when an Internet crime is reported. Their approach is thus reactive rather than proactive. The criminal justice process will only be invoked when a crime has been reported and determined to be so by the police. The private police agencies have a more flexible approach. They tend to seek compliance by using alternative dispute resolution methods, and invoke the criminal law only when these other alternatives fail. v 29

2. 1. 4 Internet Users and User Groups in HK (5) State-funded police v However, the HKP only become involved in such matters when an Internet crime is reported. Their approach is thus reactive rather than proactive. The criminal justice process will only be invoked when a crime has been reported and determined to be so by the police. The private police agencies have a more flexible approach. They tend to seek compliance by using alternative dispute resolution methods, and invoke the criminal law only when these other alternatives fail. v 29

2. 1. 5 Electronic Crime Victimization in HK v v v The study of cyber crime victims in HK can be problematic due to the lack of accurate information. Available statistics come from the law enforcement authorities and there is little independent scholarship work on the subject to offer alternative explanations of overall crime trends. Work on victimization is relatively neglected and work on cyber crime victimization is non-existent. There is also always a problem gaining such data from the private sector, since companies strive to protect their reputations and share prices by ensuring that news of such victimization is kept secret. However, the situation has improved recently with the establishment of HKCERT, which reports the number of computer systems compromised. 30

2. 1. 5 Electronic Crime Victimization in HK v v v The study of cyber crime victims in HK can be problematic due to the lack of accurate information. Available statistics come from the law enforcement authorities and there is little independent scholarship work on the subject to offer alternative explanations of overall crime trends. Work on victimization is relatively neglected and work on cyber crime victimization is non-existent. There is also always a problem gaining such data from the private sector, since companies strive to protect their reputations and share prices by ensuring that news of such victimization is kept secret. However, the situation has improved recently with the establishment of HKCERT, which reports the number of computer systems compromised. 30

2. 2 Law Enforcement in Cyberspace – introduction On 1 st April 2003, at the height of the SARS crisis in Hong Kong, a 14 -year old F. 3 school boy prepared a bogus news report stating that Hong Kong had been declared an infected port, that its stock market index (the Hang Seng Index) had collapsed, and that the Chief Executive, Tung Chee-hwa, had resigned. He placed this ‘news report’ on his website and, significantly, added the logo of a popular Chinese-language Hong Kong newspaper, copied from the latter’s website. v The HK government was forced to issue a denial; it also sent out millions of text messages to mobile phone users denying the rumors. v 31

2. 2 Law Enforcement in Cyberspace – introduction On 1 st April 2003, at the height of the SARS crisis in Hong Kong, a 14 -year old F. 3 school boy prepared a bogus news report stating that Hong Kong had been declared an infected port, that its stock market index (the Hang Seng Index) had collapsed, and that the Chief Executive, Tung Chee-hwa, had resigned. He placed this ‘news report’ on his website and, significantly, added the logo of a popular Chinese-language Hong Kong newspaper, copied from the latter’s website. v The HK government was forced to issue a denial; it also sent out millions of text messages to mobile phone users denying the rumors. v 31

2. 2 Law Enforcement in Cyberspace – introduction v Initially arrested for allegedly gaining access to a computer with criminal or dishonest intent, carrying a possible sentence of five years’ imprisonment, the boy was subsequently charged with the distinctly non-cyber summary offence of ‘knowingly furnishing any information which is false concerning any [infectious] disease or death’, contrary to Regulation 7 of the Prevention of the Spread of Infectious Diseases Regulations, which carries a maximum penalty of a fine of HK 2500. 32

2. 2 Law Enforcement in Cyberspace – introduction v Initially arrested for allegedly gaining access to a computer with criminal or dishonest intent, carrying a possible sentence of five years’ imprisonment, the boy was subsequently charged with the distinctly non-cyber summary offence of ‘knowingly furnishing any information which is false concerning any [infectious] disease or death’, contrary to Regulation 7 of the Prevention of the Spread of Infectious Diseases Regulations, which carries a maximum penalty of a fine of HK 2500. 32

2. 2 Law Enforcement in Cyberspace – introduction v Why was this conduct not prosecuted as a computer crime, given its significant cyber elements, the use of the Internet and the World Wide Web? The answer, surprising perhaps, given HK’s technologically savvy, highly ‘wired’ community, was simply that, in the absence of a provable criminal or dishonest intent, no existing ‘computer crime’ under HK law readily covered this conduct. The reason for this largely lies in the fact that HK’s current body of cyber-crimes were enacted in 1993 and reflect a view of computer criminality current at that time, rather than in today’s Internet-driven information society. 33

2. 2 Law Enforcement in Cyberspace – introduction v Why was this conduct not prosecuted as a computer crime, given its significant cyber elements, the use of the Internet and the World Wide Web? The answer, surprising perhaps, given HK’s technologically savvy, highly ‘wired’ community, was simply that, in the absence of a provable criminal or dishonest intent, no existing ‘computer crime’ under HK law readily covered this conduct. The reason for this largely lies in the fact that HK’s current body of cyber-crimes were enacted in 1993 and reflect a view of computer criminality current at that time, rather than in today’s Internet-driven information society. 33

2. 3 Historical Development of Internet Law in Hong Kong v v HK enacted its first piece of legislation expressly directed at computer-related crime, the Computer Crimes Ordinance in 1993. This Ordinance, despite its name, was neither a comprehensive response to the computer crime problem nor was it intended to provide HK with a stand-alone, computer-specific legislative framework. Rather, ti attempted to deal with HK’s most immediate needs by filling clear legislative gaps. This does not mean that HK has ignored the technological advances since 1993, or failed to address the new criminal opportunities and methodologies created by the Internet age and information society and the development of cyberspace, but there has been relatively little in the way of further cyber-crime legislation. 34

2. 3 Historical Development of Internet Law in Hong Kong v v HK enacted its first piece of legislation expressly directed at computer-related crime, the Computer Crimes Ordinance in 1993. This Ordinance, despite its name, was neither a comprehensive response to the computer crime problem nor was it intended to provide HK with a stand-alone, computer-specific legislative framework. Rather, ti attempted to deal with HK’s most immediate needs by filling clear legislative gaps. This does not mean that HK has ignored the technological advances since 1993, or failed to address the new criminal opportunities and methodologies created by the Internet age and information society and the development of cyberspace, but there has been relatively little in the way of further cyber-crime legislation. 34

2. 3 Historical Development of Internet Law in Hong Kong v v Legislation against the making and dissemination of child pornography – including online and electronic child pornography – has been enacted, as has legislation dealing with the ‘wiretapping’ of computer networks. A draft order aimed at expending criminal jurisdiction over computer crimes is also presently before the legislature. But most of the existing legislation remains rooted in concepts and ‘crimes’ formulated in the early 1990 s, before the use of the Internet exploded and gave rise to today’s information society. Instead of a proactive legislative program, the HK government has given priority to strengthening its law enforcement resources and capabilities in dealing with computer crime and gaining the cooperation of the private sector in the fight against computer crime, while simultaneously promoting public education about the 35 Internet and computer crime.

2. 3 Historical Development of Internet Law in Hong Kong v v Legislation against the making and dissemination of child pornography – including online and electronic child pornography – has been enacted, as has legislation dealing with the ‘wiretapping’ of computer networks. A draft order aimed at expending criminal jurisdiction over computer crimes is also presently before the legislature. But most of the existing legislation remains rooted in concepts and ‘crimes’ formulated in the early 1990 s, before the use of the Internet exploded and gave rise to today’s information society. Instead of a proactive legislative program, the HK government has given priority to strengthening its law enforcement resources and capabilities in dealing with computer crime and gaining the cooperation of the private sector in the fight against computer crime, while simultaneously promoting public education about the 35 Internet and computer crime.

2. 3 Historical Development of Internet Law in Hong Kong v v For example, since 1993 HK has been the establishment of specialist computer crime and crime prevention units within the HK Police (including a Computer Crime Section set up in 1993, and a Technology Crime Division set up in 2001), the Independent Commission Against Corruption, the Customs and Excise Department (which has set up an Anti-Internet Piracy Team), and the Prosecutions Division at the Department of Justice. Computer forensic has received attention with the formation in 1998 of a Computer Forensics Examination Working Group (involving the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, the Police and the ICAC) and the establishment of professional computer forensic training programs. The protection of HK’s computer infrastructure gained added impetus with the establishment in early 2001 of a government-funded 36 Computer Emergency Response Team (HKCERT)

2. 3 Historical Development of Internet Law in Hong Kong v v For example, since 1993 HK has been the establishment of specialist computer crime and crime prevention units within the HK Police (including a Computer Crime Section set up in 1993, and a Technology Crime Division set up in 2001), the Independent Commission Against Corruption, the Customs and Excise Department (which has set up an Anti-Internet Piracy Team), and the Prosecutions Division at the Department of Justice. Computer forensic has received attention with the formation in 1998 of a Computer Forensics Examination Working Group (involving the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, the Police and the ICAC) and the establishment of professional computer forensic training programs. The protection of HK’s computer infrastructure gained added impetus with the establishment in early 2001 of a government-funded 36 Computer Emergency Response Team (HKCERT)

2. 3 Historical Development of Internet Law in Hong Kong v v Furthermore, in early 2000, responding to renewed concerns about reported increases in computer-related crime, the HKSAR government convened an Interdepartmental Working Group (WG) to review the effect of changes introduced by the 1993 Computer Crimes Ordinance, and to consider future developments. In its Report, the WG expressed confidence that the thrust of the legislative changes effected by the Computer Crimes Ordinance in 1993 (particularly the two new offences of unauthorized access to computer by tele -communication (S 27 A, Telecommunications Ordinance) and access to computer with criminal and dishonest intent (S 161, Crimes Ordinance)) remains on the right lines that the changes have enabled the successful prosecution of most instances of reported computer crime, and that the changes should be retained. 37

2. 3 Historical Development of Internet Law in Hong Kong v v Furthermore, in early 2000, responding to renewed concerns about reported increases in computer-related crime, the HKSAR government convened an Interdepartmental Working Group (WG) to review the effect of changes introduced by the 1993 Computer Crimes Ordinance, and to consider future developments. In its Report, the WG expressed confidence that the thrust of the legislative changes effected by the Computer Crimes Ordinance in 1993 (particularly the two new offences of unauthorized access to computer by tele -communication (S 27 A, Telecommunications Ordinance) and access to computer with criminal and dishonest intent (S 161, Crimes Ordinance)) remains on the right lines that the changes have enabled the successful prosecution of most instances of reported computer crime, and that the changes should be retained. 37

2. 3 Historical Development of Internet Law in Hong Kong v v At the same time, the WG recognized that new initiative have becoming necessary. Accordingly, it made a series of recommendations covering a broad range of cybercrime issues, including further amendments to HK’s existing substantive and procedural law. Mindful of the criticisms leveled at it in 1993, the Administration undertook consultation with interested parties over several months before bringing the Report and its recommendations (in some instances with amendments in the light of comments during public consultation) before the Chief Executive in Council (Exco) in July 2001. Exco broadly approved most of the recommendations and adopted a Tentative Implementation Plan setting out short, medium and long-term actions to be taken to implement the WG’s Report. 38

2. 3 Historical Development of Internet Law in Hong Kong v v At the same time, the WG recognized that new initiative have becoming necessary. Accordingly, it made a series of recommendations covering a broad range of cybercrime issues, including further amendments to HK’s existing substantive and procedural law. Mindful of the criticisms leveled at it in 1993, the Administration undertook consultation with interested parties over several months before bringing the Report and its recommendations (in some instances with amendments in the light of comments during public consultation) before the Chief Executive in Council (Exco) in July 2001. Exco broadly approved most of the recommendations and adopted a Tentative Implementation Plan setting out short, medium and long-term actions to be taken to implement the WG’s Report. 38

2. 3 Historical Development of Internet Law in Hong Kong v v v A dedicated inter-departmental Task Force on Computer Related Crime has been established to follow up on this Implement Plan. Recently, delivering the keynote speech at an IEE Symposium, “Internet law in Hong Kong”, the Secretary of Justice, Elsie Leung Oi See, reiterated the Administration’s view that ‘the Computer Crimes Ordinance remains broadly adequate to deal with illicit acts such as hacking, the spreading of computer viruses and criminal damage of computer data. ’ The government, she affirmed, nonetheless remained committed, in accordance with the tentative implement plan formulated in July 2001, to a threefold strategy for enhancing HK’s cyber-crime readiness : 39

2. 3 Historical Development of Internet Law in Hong Kong v v v A dedicated inter-departmental Task Force on Computer Related Crime has been established to follow up on this Implement Plan. Recently, delivering the keynote speech at an IEE Symposium, “Internet law in Hong Kong”, the Secretary of Justice, Elsie Leung Oi See, reiterated the Administration’s view that ‘the Computer Crimes Ordinance remains broadly adequate to deal with illicit acts such as hacking, the spreading of computer viruses and criminal damage of computer data. ’ The government, she affirmed, nonetheless remained committed, in accordance with the tentative implement plan formulated in July 2001, to a threefold strategy for enhancing HK’s cyber-crime readiness : 39

2. 3 Historical Development of Internet Law in Hong Kong (1) strengthen the existing regulatory regime; v (2) increase the involvement of the community in the prevention and detection of computer-related crimes; v (3) improve co-ordination and institutional arrangements to prevent cyber attacks and promote cyber security. v v In formulating contemporaneous international developments, such as the Council of Europe’s Convention on cyber-crime. This has already occasioned the enactment of legislation dealing with child pornography, but it will also likely lead to further proposals for change. 40

2. 3 Historical Development of Internet Law in Hong Kong (1) strengthen the existing regulatory regime; v (2) increase the involvement of the community in the prevention and detection of computer-related crimes; v (3) improve co-ordination and institutional arrangements to prevent cyber attacks and promote cyber security. v v In formulating contemporaneous international developments, such as the Council of Europe’s Convention on cyber-crime. This has already occasioned the enactment of legislation dealing with child pornography, but it will also likely lead to further proposals for change. 40

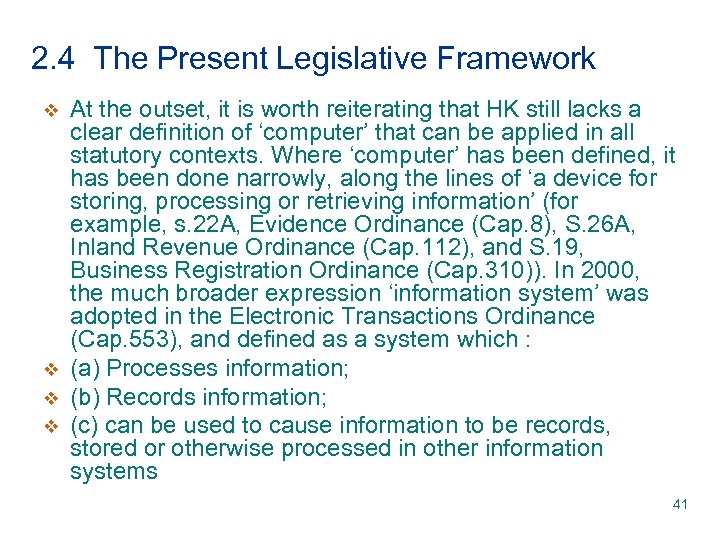

2. 4 The Present Legislative Framework v v At the outset, it is worth reiterating that HK still lacks a clear definition of ‘computer’ that can be applied in all statutory contexts. Where ‘computer’ has been defined, it has been done narrowly, along the lines of ‘a device for storing, processing or retrieving information’ (for example, s. 22 A, Evidence Ordinance (Cap. 8), S. 26 A, Inland Revenue Ordinance (Cap. 112), and S. 19, Business Registration Ordinance (Cap. 310)). In 2000, the much broader expression ‘information system’ was adopted in the Electronic Transactions Ordinance (Cap. 553), and defined as a system which : (a) Processes information; (b) Records information; (c) can be used to cause information to be records, stored or otherwise processed in other information systems 41

2. 4 The Present Legislative Framework v v At the outset, it is worth reiterating that HK still lacks a clear definition of ‘computer’ that can be applied in all statutory contexts. Where ‘computer’ has been defined, it has been done narrowly, along the lines of ‘a device for storing, processing or retrieving information’ (for example, s. 22 A, Evidence Ordinance (Cap. 8), S. 26 A, Inland Revenue Ordinance (Cap. 112), and S. 19, Business Registration Ordinance (Cap. 310)). In 2000, the much broader expression ‘information system’ was adopted in the Electronic Transactions Ordinance (Cap. 553), and defined as a system which : (a) Processes information; (b) Records information; (c) can be used to cause information to be records, stored or otherwise processed in other information systems 41

2. 4 The Present Legislative Framework v (d) can be used to retrieve information, whether v In its 2000 Report on Computer related crime, the WG recommended that the expression ‘information system’ should be adopted instead of ‘computer’ in existing and future legislation. the information is recorded or stored in the system itself or in other information systems (whenever situated). 42

2. 4 The Present Legislative Framework v (d) can be used to retrieve information, whether v In its 2000 Report on Computer related crime, the WG recommended that the expression ‘information system’ should be adopted instead of ‘computer’ in existing and future legislation. the information is recorded or stored in the system itself or in other information systems (whenever situated). 42

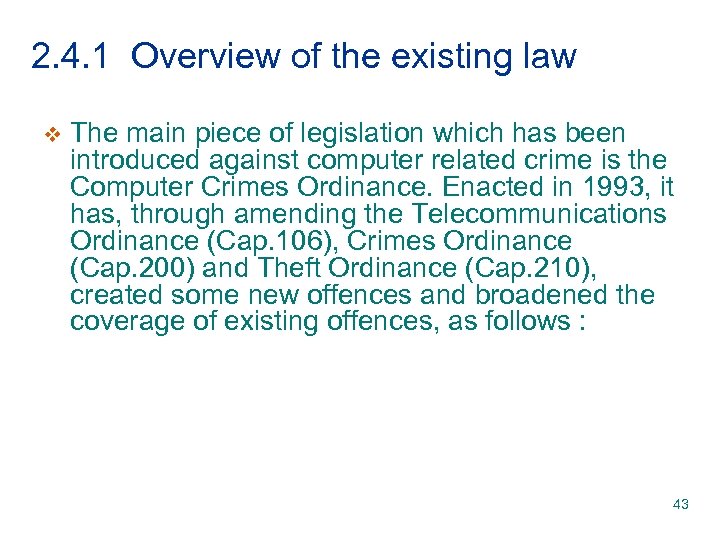

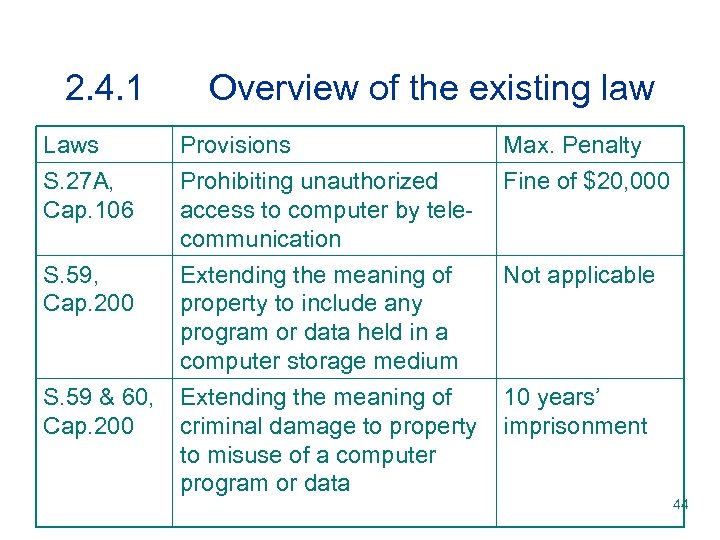

2. 4. 1 Overview of the existing law v The main piece of legislation which has been introduced against computer related crime is the Computer Crimes Ordinance. Enacted in 1993, it has, through amending the Telecommunications Ordinance (Cap. 106), Crimes Ordinance (Cap. 200) and Theft Ordinance (Cap. 210), created some new offences and broadened the coverage of existing offences, as follows : 43

2. 4. 1 Overview of the existing law v The main piece of legislation which has been introduced against computer related crime is the Computer Crimes Ordinance. Enacted in 1993, it has, through amending the Telecommunications Ordinance (Cap. 106), Crimes Ordinance (Cap. 200) and Theft Ordinance (Cap. 210), created some new offences and broadened the coverage of existing offences, as follows : 43

2. 4. 1 Laws S. 27 A, Cap. 106 S. 59, Cap. 200 S. 59 & 60, Cap. 200 Overview of the existing law Provisions Prohibiting unauthorized access to computer by telecommunication Extending the meaning of property to include any program or data held in a computer storage medium Extending the meaning of criminal damage to property to misuse of a computer program or data Max. Penalty Fine of $20, 000 Not applicable 10 years’ imprisonment 44

2. 4. 1 Laws S. 27 A, Cap. 106 S. 59, Cap. 200 S. 59 & 60, Cap. 200 Overview of the existing law Provisions Prohibiting unauthorized access to computer by telecommunication Extending the meaning of property to include any program or data held in a computer storage medium Extending the meaning of criminal damage to property to misuse of a computer program or data Max. Penalty Fine of $20, 000 Not applicable 10 years’ imprisonment 44

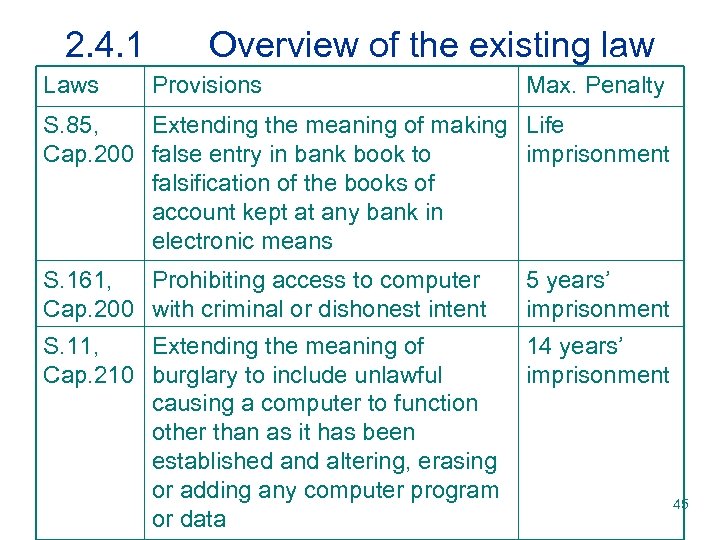

2. 4. 1 Laws Overview of the existing law Provisions Max. Penalty S. 85, Extending the meaning of making Life Cap. 200 false entry in bank book to imprisonment falsification of the books of account kept at any bank in electronic means S. 161, Prohibiting access to computer Cap. 200 with criminal or dishonest intent 5 years’ imprisonment S. 11, Extending the meaning of Cap. 210 burglary to include unlawful causing a computer to function other than as it has been established and altering, erasing or adding any computer program or data 14 years’ imprisonment 45

2. 4. 1 Laws Overview of the existing law Provisions Max. Penalty S. 85, Extending the meaning of making Life Cap. 200 false entry in bank book to imprisonment falsification of the books of account kept at any bank in electronic means S. 161, Prohibiting access to computer Cap. 200 with criminal or dishonest intent 5 years’ imprisonment S. 11, Extending the meaning of Cap. 210 burglary to include unlawful causing a computer to function other than as it has been established and altering, erasing or adding any computer program or data 14 years’ imprisonment 45

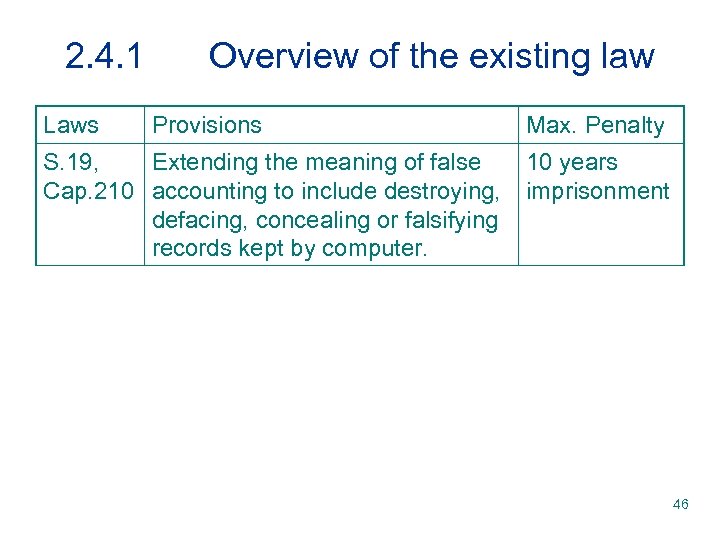

2. 4. 1 Laws Overview of the existing law Provisions S. 19, Extending the meaning of false Cap. 210 accounting to include destroying, defacing, concealing or falsifying records kept by computer. Max. Penalty 10 years imprisonment 46

2. 4. 1 Laws Overview of the existing law Provisions S. 19, Extending the meaning of false Cap. 210 accounting to include destroying, defacing, concealing or falsifying records kept by computer. Max. Penalty 10 years imprisonment 46

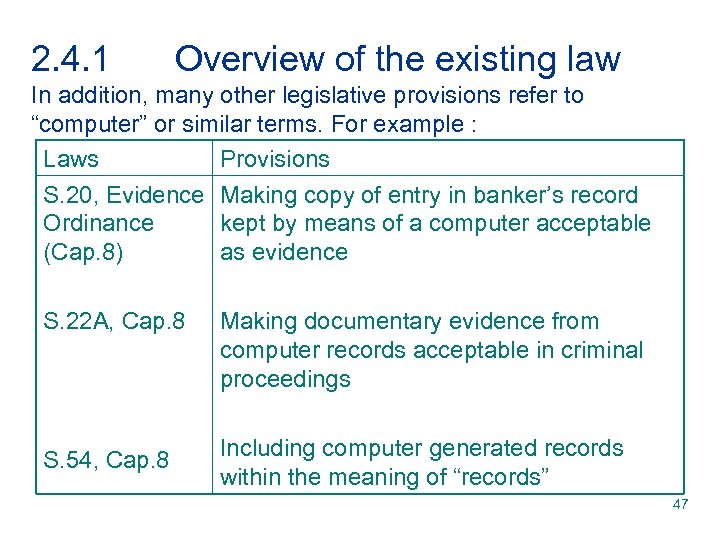

2. 4. 1 Overview of the existing law In addition, many other legislative provisions refer to “computer” or similar terms. For example : Laws Provisions S. 20, Evidence Making copy of entry in banker’s record Ordinance kept by means of a computer acceptable (Cap. 8) as evidence S. 22 A, Cap. 8 Making documentary evidence from computer records acceptable in criminal proceedings S. 54, Cap. 8 Including computer generated records within the meaning of “records” 47

2. 4. 1 Overview of the existing law In addition, many other legislative provisions refer to “computer” or similar terms. For example : Laws Provisions S. 20, Evidence Making copy of entry in banker’s record Ordinance kept by means of a computer acceptable (Cap. 8) as evidence S. 22 A, Cap. 8 Making documentary evidence from computer records acceptable in criminal proceedings S. 54, Cap. 8 Including computer generated records within the meaning of “records” 47

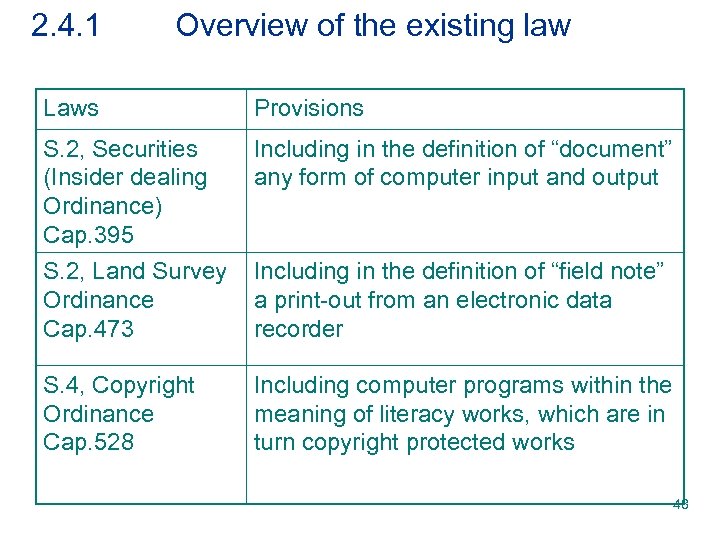

2. 4. 1 Overview of the existing law Laws Provisions S. 2, Securities (Insider dealing Ordinance) Cap. 395 Including in the definition of “document” any form of computer input and output S. 2, Land Survey Ordinance Cap. 473 Including in the definition of “field note” a print-out from an electronic data recorder S. 4, Copyright Ordinance Cap. 528 Including computer programs within the meaning of literacy works, which are in turn copyright protected works 48

2. 4. 1 Overview of the existing law Laws Provisions S. 2, Securities (Insider dealing Ordinance) Cap. 395 Including in the definition of “document” any form of computer input and output S. 2, Land Survey Ordinance Cap. 473 Including in the definition of “field note” a print-out from an electronic data recorder S. 4, Copyright Ordinance Cap. 528 Including computer programs within the meaning of literacy works, which are in turn copyright protected works 48

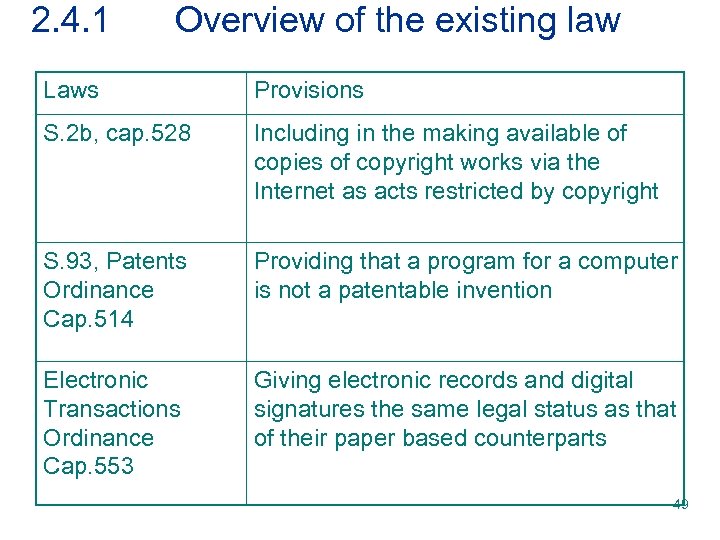

2. 4. 1 Overview of the existing law Laws Provisions S. 2 b, cap. 528 Including in the making available of copies of copyright works via the Internet as acts restricted by copyright S. 93, Patents Ordinance Cap. 514 Providing that a program for a computer is not a patentable invention Electronic Transactions Ordinance Cap. 553 Giving electronic records and digital signatures the same legal status as that of their paper based counterparts 49

2. 4. 1 Overview of the existing law Laws Provisions S. 2 b, cap. 528 Including in the making available of copies of copyright works via the Internet as acts restricted by copyright S. 93, Patents Ordinance Cap. 514 Providing that a program for a computer is not a patentable invention Electronic Transactions Ordinance Cap. 553 Giving electronic records and digital signatures the same legal status as that of their paper based counterparts 49

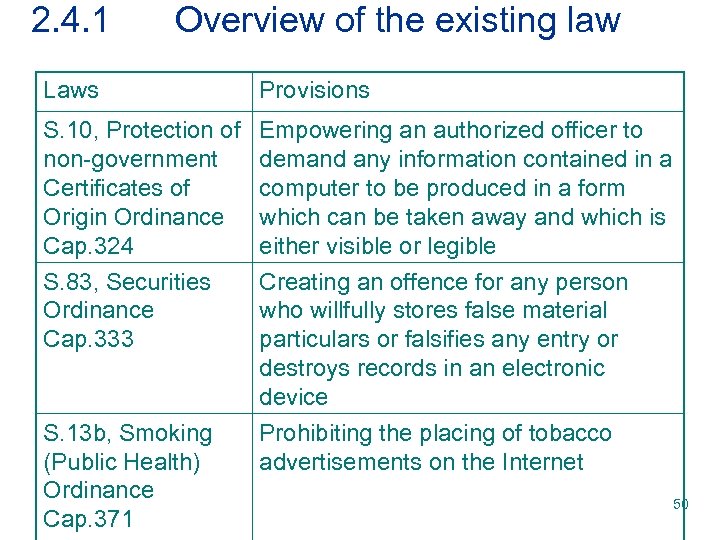

2. 4. 1 Overview of the existing law Laws Provisions S. 10, Protection of non-government Certificates of Origin Ordinance Cap. 324 Empowering an authorized officer to demand any information contained in a computer to be produced in a form which can be taken away and which is either visible or legible S. 83, Securities Ordinance Cap. 333 Creating an offence for any person who willfully stores false material particulars or falsifies any entry or destroys records in an electronic device Prohibiting the placing of tobacco advertisements on the Internet S. 13 b, Smoking (Public Health) Ordinance Cap. 371 50

2. 4. 1 Overview of the existing law Laws Provisions S. 10, Protection of non-government Certificates of Origin Ordinance Cap. 324 Empowering an authorized officer to demand any information contained in a computer to be produced in a form which can be taken away and which is either visible or legible S. 83, Securities Ordinance Cap. 333 Creating an offence for any person who willfully stores false material particulars or falsifies any entry or destroys records in an electronic device Prohibiting the placing of tobacco advertisements on the Internet S. 13 b, Smoking (Public Health) Ordinance Cap. 371 50

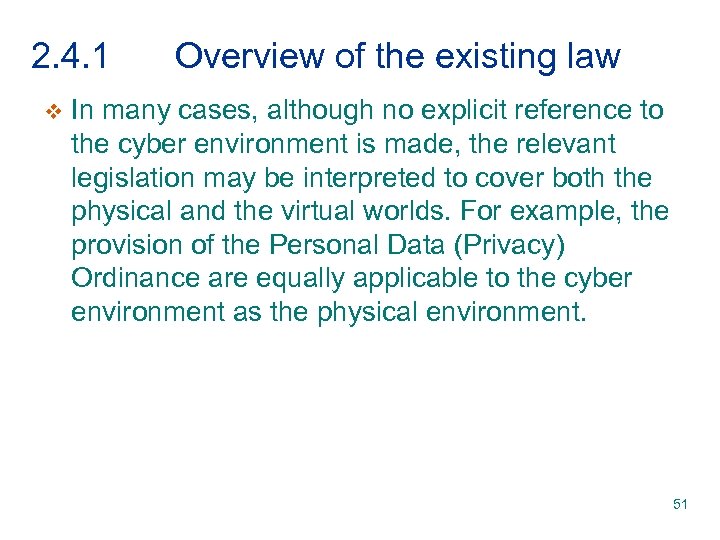

2. 4. 1 v Overview of the existing law In many cases, although no explicit reference to the cyber environment is made, the relevant legislation may be interpreted to cover both the physical and the virtual worlds. For example, the provision of the Personal Data (Privacy) Ordinance are equally applicable to the cyber environment as the physical environment. 51

2. 4. 1 v Overview of the existing law In many cases, although no explicit reference to the cyber environment is made, the relevant legislation may be interpreted to cover both the physical and the virtual worlds. For example, the provision of the Personal Data (Privacy) Ordinance are equally applicable to the cyber environment as the physical environment. 51

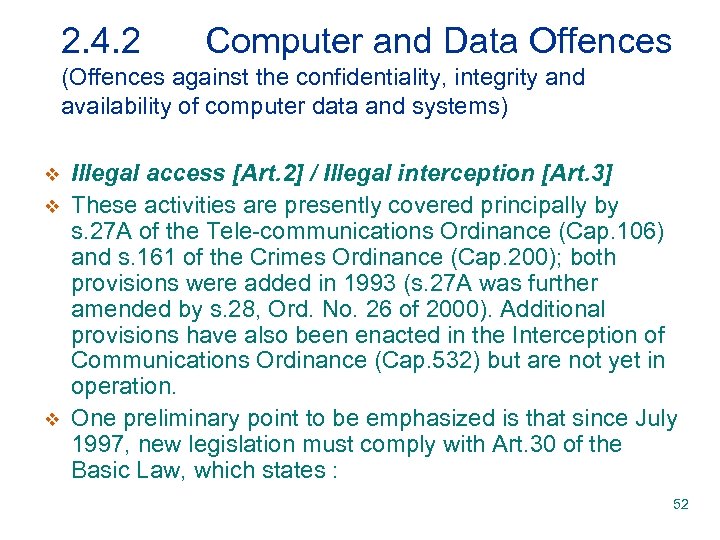

2. 4. 2 Computer and Data Offences (Offences against the confidentiality, integrity and availability of computer data and systems) v v v Illegal access [Art. 2] / Illegal interception [Art. 3] These activities are presently covered principally by s. 27 A of the Tele-communications Ordinance (Cap. 106) and s. 161 of the Crimes Ordinance (Cap. 200); both provisions were added in 1993 (s. 27 A was further amended by s. 28, Ord. No. 26 of 2000). Additional provisions have also been enacted in the Interception of Communications Ordinance (Cap. 532) but are not yet in operation. One preliminary point to be emphasized is that since July 1997, new legislation must comply with Art. 30 of the Basic Law, which states : 52

2. 4. 2 Computer and Data Offences (Offences against the confidentiality, integrity and availability of computer data and systems) v v v Illegal access [Art. 2] / Illegal interception [Art. 3] These activities are presently covered principally by s. 27 A of the Tele-communications Ordinance (Cap. 106) and s. 161 of the Crimes Ordinance (Cap. 200); both provisions were added in 1993 (s. 27 A was further amended by s. 28, Ord. No. 26 of 2000). Additional provisions have also been enacted in the Interception of Communications Ordinance (Cap. 532) but are not yet in operation. One preliminary point to be emphasized is that since July 1997, new legislation must comply with Art. 30 of the Basic Law, which states : 52

2. 4. 2 Computer and Data Offences “The freedom and privacy of communication of Hong Kong residents shall be protected by law. No department or individual may, on any grounds, infringe upon the freedom and privacy of communication of residents except that the relevant authorities may inspect communication in accordance with legal procedures to meet the needs of public security or of investigation into criminal offences. ” v This requires the government to balance the needs of law enforcement with the rights of its citizens to protection of their privacy, not always an easy balancing act. v 53

2. 4. 2 Computer and Data Offences “The freedom and privacy of communication of Hong Kong residents shall be protected by law. No department or individual may, on any grounds, infringe upon the freedom and privacy of communication of residents except that the relevant authorities may inspect communication in accordance with legal procedures to meet the needs of public security or of investigation into criminal offences. ” v This requires the government to balance the needs of law enforcement with the rights of its citizens to protection of their privacy, not always an easy balancing act. v 53

2. 4. 2. v v v Computer and Data Offences Telecommunications Ordinance (Cap. 106) Section 27 A(1) – This section deals with unauthorized access to a computer by telecommunication, that is, hacking. It provides: ‘Any person who, by telecommunications, knowingly causes a computer to perform any function to obtain unauthorized access to any program held in a computer commits an offence and is liable on conviction to a fine of HK$20, 000. ‘Telecommunications’ is defined in the Ordinance (s. 2) as ‘any transmission, emission or reception of communication by means of guided or unguided electromagnetic energy or both, other than any transmission or emission intended to be received or perceived directly by the human eye. ’ 54

2. 4. 2. v v v Computer and Data Offences Telecommunications Ordinance (Cap. 106) Section 27 A(1) – This section deals with unauthorized access to a computer by telecommunication, that is, hacking. It provides: ‘Any person who, by telecommunications, knowingly causes a computer to perform any function to obtain unauthorized access to any program held in a computer commits an offence and is liable on conviction to a fine of HK$20, 000. ‘Telecommunications’ is defined in the Ordinance (s. 2) as ‘any transmission, emission or reception of communication by means of guided or unguided electromagnetic energy or both, other than any transmission or emission intended to be received or perceived directly by the human eye. ’ 54

2. 4. 2. v v v Computer and Data Offences Telecommunications Ordinance (Cap. 106) Section 27 A(1) requires proof that the person who caused a computer to perform any function enabling unauthorized access did so ‘knowingly’; however, under subsection 2(a), his intent need not be directed at (i) any particular program or data, (ii) a program or data of a particular kind, or (iii) a program or data held in a particular computer (s. 27 A(2)(a)). Section 27 A(2)(b) further declares that access is unauthorized if the hacker is not entitled to control access of the kind in question to the program or data held in the computer, and (i) has not been authorized to obtain access of the kind in question to the program or data held in the computer by any person who is so entitled, (ii) does not believe that he has been so authorized and 55

2. 4. 2. v v v Computer and Data Offences Telecommunications Ordinance (Cap. 106) Section 27 A(1) requires proof that the person who caused a computer to perform any function enabling unauthorized access did so ‘knowingly’; however, under subsection 2(a), his intent need not be directed at (i) any particular program or data, (ii) a program or data of a particular kind, or (iii) a program or data held in a particular computer (s. 27 A(2)(a)). Section 27 A(2)(b) further declares that access is unauthorized if the hacker is not entitled to control access of the kind in question to the program or data held in the computer, and (i) has not been authorized to obtain access of the kind in question to the program or data held in the computer by any person who is so entitled, (ii) does not believe that he has been so authorized and 55

2. 4. 2. v v v Computer and Data Offences Telecommunications Ordinance (Cap. 106) (iii) does not believe that authorization would have been given if application had been made to the appropriate authority (s 27 A (2)(b)). Proceedings for an offence under this section must be commenced within three years of commission of the offence or six months of its discovery by the prosecutor, whichever period expires (s. 27 A(4)). In 2000, the Inter-departmental WG on computer Related Crime described the HK$20, 000 penalty under s. 27 A as ‘a woefully inadequate deterrent’, given the ‘very significant damage that hacking may bring about (Report, para. 2. 7); it duly recommended the addition of a custodial term, but this has yet to be implemented. In addition, the WG recommended that unauthorized access to a computer by any means and just by telecommunication, should be made unlawful by any means, and not just by telecommunication, should be made unlawful. Similarly, this has yet to be implemented. 56

2. 4. 2. v v v Computer and Data Offences Telecommunications Ordinance (Cap. 106) (iii) does not believe that authorization would have been given if application had been made to the appropriate authority (s 27 A (2)(b)). Proceedings for an offence under this section must be commenced within three years of commission of the offence or six months of its discovery by the prosecutor, whichever period expires (s. 27 A(4)). In 2000, the Inter-departmental WG on computer Related Crime described the HK$20, 000 penalty under s. 27 A as ‘a woefully inadequate deterrent’, given the ‘very significant damage that hacking may bring about (Report, para. 2. 7); it duly recommended the addition of a custodial term, but this has yet to be implemented. In addition, the WG recommended that unauthorized access to a computer by any means and just by telecommunication, should be made unlawful by any means, and not just by telecommunication, should be made unlawful. Similarly, this has yet to be implemented. 56

2. 4. 2. v v Computer and Data Offences Telecommunications Ordinance (Cap. 106) Other offences : Several additional sections of the Tele-communications Ordinance deal with offences involving the interception, alteration and such like of ‘messages’; a ‘message’ being ‘any communication sent or received by telecommunications or given to a telecommunications officer to be sent by telecommunications or to be delivered’ (s. 2). Section 24 makes it an offence for a ‘telecommunications officer’ (‘any person employed in connection with a telecommunications service’, s. 2), or any other person having ‘official duties in connection with a telecommunications service’ to (a) willfully destroy, secrete or alter a message, (b) knowingly forge or utter a message, (c) willfully intercept, detain or delay, or willfully abstain from transmitting a message, or (d) copy a message or disclose a message or its purport to any 57 person other than its addressee.

2. 4. 2. v v Computer and Data Offences Telecommunications Ordinance (Cap. 106) Other offences : Several additional sections of the Tele-communications Ordinance deal with offences involving the interception, alteration and such like of ‘messages’; a ‘message’ being ‘any communication sent or received by telecommunications or given to a telecommunications officer to be sent by telecommunications or to be delivered’ (s. 2). Section 24 makes it an offence for a ‘telecommunications officer’ (‘any person employed in connection with a telecommunications service’, s. 2), or any other person having ‘official duties in connection with a telecommunications service’ to (a) willfully destroy, secrete or alter a message, (b) knowingly forge or utter a message, (c) willfully intercept, detain or delay, or willfully abstain from transmitting a message, or (d) copy a message or disclose a message or its purport to any 57 person other than its addressee.

2. 4. 2. v v v Computer and Data Offences Telecommunications Ordinance (Cap. 106) Section 25 makes it an offence for a person who is not a telecommunications officer, or who has official duties in connection with a telecommunications service, or who has been entrusted by a telecommunications officer to deliver a message, to willfully secrete, detain or delay a message intended for delivery to some other person, or to refuse or neglect to deliver up a message in his possession when required by a telecommunications officer to do so. Section 27 makes it an offence for any person to damage, remove or interfere with a ’communications installation’ ‘with intent’ (a) to prevent or obstruct the transmission or delivery of a message, or (b) to intercept or discover the content of a message. 58

2. 4. 2. v v v Computer and Data Offences Telecommunications Ordinance (Cap. 106) Section 25 makes it an offence for a person who is not a telecommunications officer, or who has official duties in connection with a telecommunications service, or who has been entrusted by a telecommunications officer to deliver a message, to willfully secrete, detain or delay a message intended for delivery to some other person, or to refuse or neglect to deliver up a message in his possession when required by a telecommunications officer to do so. Section 27 makes it an offence for any person to damage, remove or interfere with a ’communications installation’ ‘with intent’ (a) to prevent or obstruct the transmission or delivery of a message, or (b) to intercept or discover the content of a message. 58

2. 4. 2. Computer and Data Offences Telecommunications Ordinance (Cap. 106) v Finally, s. 28 criminalizes the transmission by tele -communications of false distress message, knowing or believing the message to be false and intending its transmission to deceive. v Breaches of ss. 24, 25, 27 or 28 are all punishable upon summary conviction with a fine of HK$20 000 (at level 3 in the case of s. 28) and imprisonment for up to two years. v 59

2. 4. 2. Computer and Data Offences Telecommunications Ordinance (Cap. 106) v Finally, s. 28 criminalizes the transmission by tele -communications of false distress message, knowing or believing the message to be false and intending its transmission to deceive. v Breaches of ss. 24, 25, 27 or 28 are all punishable upon summary conviction with a fine of HK$20 000 (at level 3 in the case of s. 28) and imprisonment for up to two years. v 59

2. 4. 2. v v Computer and Data Offences Section 161, Crimes Ordinance (Cap. 200) Section 161 deals with accessing a computer with criminal or dishonest intent. Sub-section 161 (1) creates a more serious offence, and is punishable on conviction on indictment to imprisonment for five years. It reads : (1) Any person who obtains access to a computer – (a) with intent to commit an offence (b) with a dishonest intent to deceive (c) with a view to dishonest gain for himself or another (d) with a dishonest intent to cause loss to another whether on the same occasion as he obtains such access or on any future occasion, commits an offence … Section 161 has been considered by the courts on several occasions. In Hung Hak Sing (1995), Hung was charged under s. 161 (1)c with obtaining access to the Immigration Department’s computer system. 60

2. 4. 2. v v Computer and Data Offences Section 161, Crimes Ordinance (Cap. 200) Section 161 deals with accessing a computer with criminal or dishonest intent. Sub-section 161 (1) creates a more serious offence, and is punishable on conviction on indictment to imprisonment for five years. It reads : (1) Any person who obtains access to a computer – (a) with intent to commit an offence (b) with a dishonest intent to deceive (c) with a view to dishonest gain for himself or another (d) with a dishonest intent to cause loss to another whether on the same occasion as he obtains such access or on any future occasion, commits an offence … Section 161 has been considered by the courts on several occasions. In Hung Hak Sing (1995), Hung was charged under s. 161 (1)c with obtaining access to the Immigration Department’s computer system. 60

2. 4. 2. Computer and Data Offences Section 161, Crimes Ordinance (Cap. 200) v The prosecution alleged that he acted at the request of a friend of his, a senior customs officer (who was party to a separate criminal conspiracy), to discover whether certain people were on the customs watch list. The prosecution alleged but failed to prove that Hung expected to be paid for his acts; seemingly Hung acted out of friendship and without knowledge of the separate conspiracy. Hung’s conviction was quashed by the Court of Appeal, on the ground that, even if ‘gain’ included the mere fact of obtaining information, the prosecution had failed to prove that Hung acted ‘with a view to dishonest gain’. v 61

2. 4. 2. Computer and Data Offences Section 161, Crimes Ordinance (Cap. 200) v The prosecution alleged that he acted at the request of a friend of his, a senior customs officer (who was party to a separate criminal conspiracy), to discover whether certain people were on the customs watch list. The prosecution alleged but failed to prove that Hung expected to be paid for his acts; seemingly Hung acted out of friendship and without knowledge of the separate conspiracy. Hung’s conviction was quashed by the Court of Appeal, on the ground that, even if ‘gain’ included the mere fact of obtaining information, the prosecution had failed to prove that Hung acted ‘with a view to dishonest gain’. v 61

2. 4. 2. v v v Computer and Data Offences Section 161, Crimes Ordinance (Cap. 200) In HKSAR v Tong Ka Kin (1996), Duffy J adopted a broad view of ‘with a dishonest intent to cause loss’ under (d), holding that it was enough for the prosecution to establish that the defendant’s conduct, in giving out details of customer’s accounts at the telecom company where he was a customer services officer, involved potential loss to subscribers or the company, rather that any actual loss to a particular subscriber. In HKSAR v Tsun Shi Lun (1992), a hospital technical assistant was prosecuted for accessing the hospital’s computer, printing out an x-ray report to the Secretary of Justice, and later anonymously facing copies of it to two newspapers, allegedly to correct what he considered was a mis-impression given to the public by the government as to the state of the secretary’s health. Tsun was charged under s. 161 (1)c. 62

2. 4. 2. v v v Computer and Data Offences Section 161, Crimes Ordinance (Cap. 200) In HKSAR v Tong Ka Kin (1996), Duffy J adopted a broad view of ‘with a dishonest intent to cause loss’ under (d), holding that it was enough for the prosecution to establish that the defendant’s conduct, in giving out details of customer’s accounts at the telecom company where he was a customer services officer, involved potential loss to subscribers or the company, rather that any actual loss to a particular subscriber. In HKSAR v Tsun Shi Lun (1992), a hospital technical assistant was prosecuted for accessing the hospital’s computer, printing out an x-ray report to the Secretary of Justice, and later anonymously facing copies of it to two newspapers, allegedly to correct what he considered was a mis-impression given to the public by the government as to the state of the secretary’s health. Tsun was charged under s. 161 (1)c. 62

2. 4. 2. v v Computer and Data Offences Section 161, Crimes Ordinance (Cap. 200) He argued that his conduct did not fall within (c) since it was done neither with a view to gain for himself, nor dishonestly. Both arguments were rejected in the Court of First Instance. Chan CJHC held that the legislative objective in enacting s. 161 (1)c was to criminalize the fact of access to a computer in itself, provided it was dishonest; accordingly, it was not restricted to acts that could be proved to be preparatory to the commission of a crime or fraud. Following Hung Hak Sing, above, Chan CJHC held that ‘gain’ included obtaining information not available prior to access, including transient information such as that read on a computer screen. As regards ‘dishonesty’, the court applied the Ghosh test, concluding that the only reasonable inference to be drawn from the facts was that Tsun knew and must have realized it was dishonest conduct to access the computer, print out a copy of the report, leak it to the press. At trial, he was put into prison for 6 months; on appeal, 100 hours 63 community service was substituted.