387a976b48e0e361bc2f019508f570eb.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 36

CAS LX 502 14 a. Discourse Representation Theory 10. 9

CAS LX 502 14 a. Discourse Representation Theory 10. 9

Meaning in discourse • The formal stuff we have concerned ourselves with so far has primarily been concerned with evaluation of the truth conditions of sentences. • In connected discourse, there is more going on, we need to take the discourse context into account.

Meaning in discourse • The formal stuff we have concerned ourselves with so far has primarily been concerned with evaluation of the truth conditions of sentences. • In connected discourse, there is more going on, we need to take the discourse context into account.

![For example • x[delegate(x) arrived(x)] • ‘A delegate arrived. ’ • [ x[ [delegate(x) For example • x[delegate(x) arrived(x)] • ‘A delegate arrived. ’ • [ x[ [delegate(x)](https://present5.com/presentation/387a976b48e0e361bc2f019508f570eb/image-3.jpg) For example • x[delegate(x) arrived(x)] • ‘A delegate arrived. ’ • [ x[ [delegate(x) arrived(x)]]] ‘It is not the case that every delegate failed to arrive. ’ • A delegate arrived. She registered. • #It is not the case that every delegate failed to arrive. She registered.

For example • x[delegate(x) arrived(x)] • ‘A delegate arrived. ’ • [ x[ [delegate(x) arrived(x)]]] ‘It is not the case that every delegate failed to arrive. ’ • A delegate arrived. She registered. • #It is not the case that every delegate failed to arrive. She registered.

Updating the context • Somehow A delegate arrived has updated the discourse context to provide an individual referent that can later be referred to by the pronoun She. • It is not the case that every delegate failed to arrive does not update the context in the same way. It does not introduce a referent. • Indefinite noun phrases like a delegate can introduce discourse referents.

Updating the context • Somehow A delegate arrived has updated the discourse context to provide an individual referent that can later be referred to by the pronoun She. • It is not the case that every delegate failed to arrive does not update the context in the same way. It does not introduce a referent. • Indefinite noun phrases like a delegate can introduce discourse referents.

Lifespan of a referent • Pati bought an i. Podj. Hei brings itj everywhere. • An i. Pod introduces a discourse referent that the pronoun it can later refer to. • #Pat didn’t buy an i. Podj. He likes itj though. • If introduced in a negative clause, any discourse referent there might have been is not available later.

Lifespan of a referent • Pati bought an i. Podj. Hei brings itj everywhere. • An i. Pod introduces a discourse referent that the pronoun it can later refer to. • #Pat didn’t buy an i. Podj. He likes itj though. • If introduced in a negative clause, any discourse referent there might have been is not available later.

Discourse Representation Theory • DRT is a formal system to model the progression of meanings and referents in discourse. • It is a system that keeps track of what referents are introduced and what can refer back to them. • In the previous case, the negated sentence is the limit of the “reach” of the discourse referent introduced by an i. Pod. Negation blocks outside reference. • It is not the case that [Pat bought an i. Pod].

Discourse Representation Theory • DRT is a formal system to model the progression of meanings and referents in discourse. • It is a system that keeps track of what referents are introduced and what can refer back to them. • In the previous case, the negated sentence is the limit of the “reach” of the discourse referent introduced by an i. Pod. Negation blocks outside reference. • It is not the case that [Pat bought an i. Pod].

Donkey science • DRT is a response to the fairly famous problem with “donkey anaphora” of the following sort: • If a farmeri owns a donkeyj, hei pets itj. • It turns out that trying to write the truth conditions for this without the idea of introducing discourse referents is basically impossible.

Donkey science • DRT is a response to the fairly famous problem with “donkey anaphora” of the following sort: • If a farmeri owns a donkeyj, hei pets itj. • It turns out that trying to write the truth conditions for this without the idea of introducing discourse referents is basically impossible.

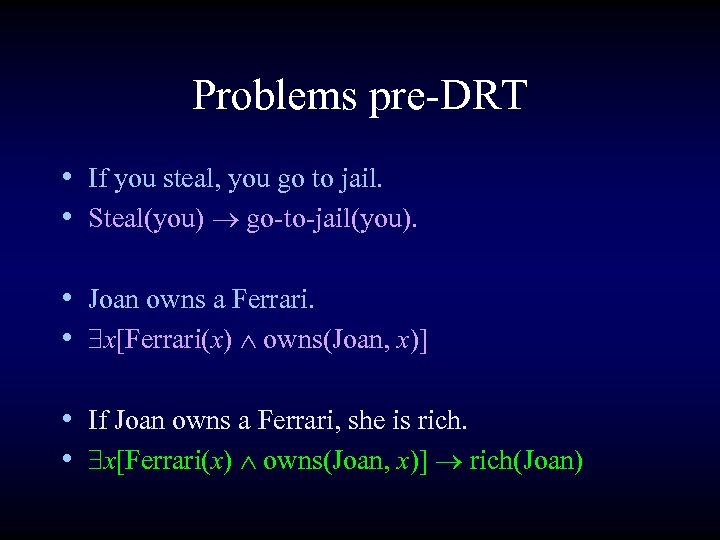

Problems pre-DRT • If you steal, you go to jail. • Steal(you) go-to-jail(you). • Joan owns a Ferrari. • x[Ferrari(x) owns(Joan, x)] • If Joan owns a Ferrari, she is rich. • x[Ferrari(x) owns(Joan, x)] rich(Joan)

Problems pre-DRT • If you steal, you go to jail. • Steal(you) go-to-jail(you). • Joan owns a Ferrari. • x[Ferrari(x) owns(Joan, x)] • If Joan owns a Ferrari, she is rich. • x[Ferrari(x) owns(Joan, x)] rich(Joan)

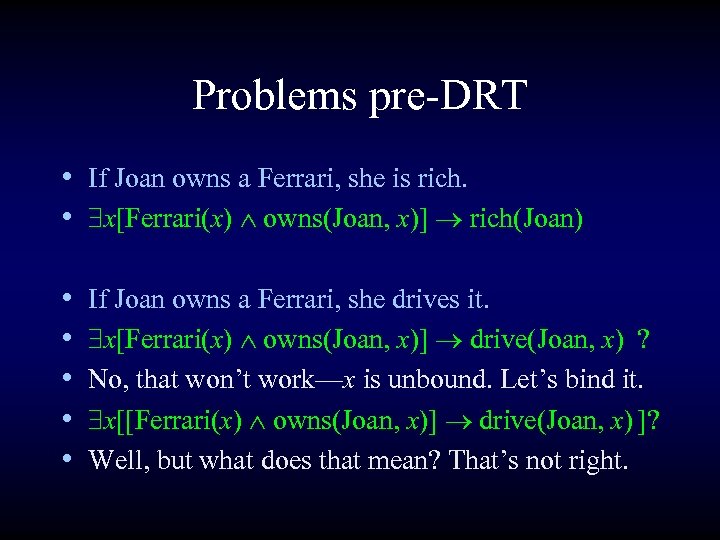

Problems pre-DRT • If Joan owns a Ferrari, she is rich. • x[Ferrari(x) owns(Joan, x)] rich(Joan) • • • If Joan owns a Ferrari, she drives it. x[Ferrari(x) owns(Joan, x)] drive(Joan, x) ? No, that won’t work—x is unbound. Let’s bind it. x[[Ferrari(x) owns(Joan, x)] drive(Joan, x) ]? Well, but what does that mean? That’s not right.

Problems pre-DRT • If Joan owns a Ferrari, she is rich. • x[Ferrari(x) owns(Joan, x)] rich(Joan) • • • If Joan owns a Ferrari, she drives it. x[Ferrari(x) owns(Joan, x)] drive(Joan, x) ? No, that won’t work—x is unbound. Let’s bind it. x[[Ferrari(x) owns(Joan, x)] drive(Joan, x) ]? Well, but what does that mean? That’s not right.

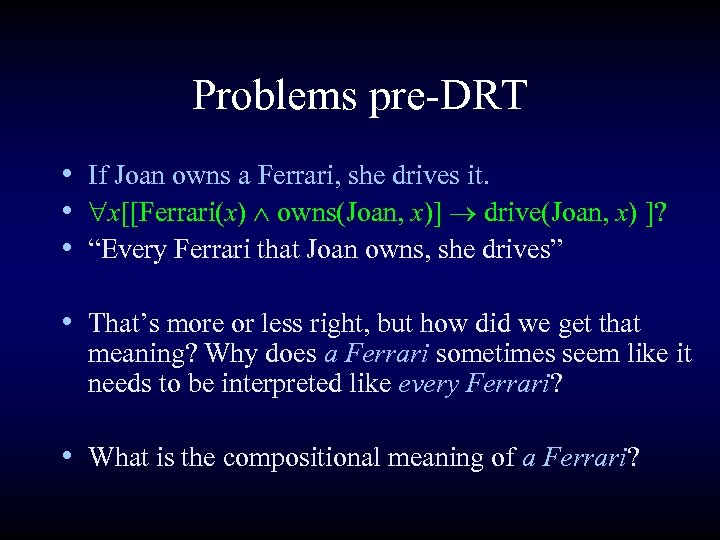

Problems pre-DRT • If Joan owns a Ferrari, she drives it. • x[[Ferrari(x) owns(Joan, x)] drive(Joan, x) ]? • “Every Ferrari that Joan owns, she drives” • That’s more or less right, but how did we get that meaning? Why does a Ferrari sometimes seem like it needs to be interpreted like every Ferrari? • What is the compositional meaning of a Ferrari?

Problems pre-DRT • If Joan owns a Ferrari, she drives it. • x[[Ferrari(x) owns(Joan, x)] drive(Joan, x) ]? • “Every Ferrari that Joan owns, she drives” • That’s more or less right, but how did we get that meaning? Why does a Ferrari sometimes seem like it needs to be interpreted like every Ferrari? • What is the compositional meaning of a Ferrari?

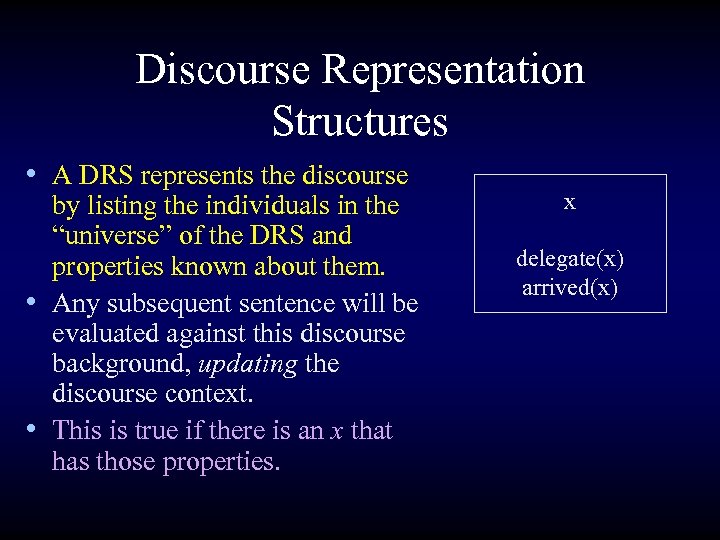

Discourse Representation Structures • A DRS represents the discourse by listing the individuals in the “universe” of the DRS and properties known about them. • Any subsequent sentence will be evaluated against this discourse background, updating the discourse context. • This is true if there is an x that has those properties. x delegate(x) arrived(x)

Discourse Representation Structures • A DRS represents the discourse by listing the individuals in the “universe” of the DRS and properties known about them. • Any subsequent sentence will be evaluated against this discourse background, updating the discourse context. • This is true if there is an x that has those properties. x delegate(x) arrived(x)

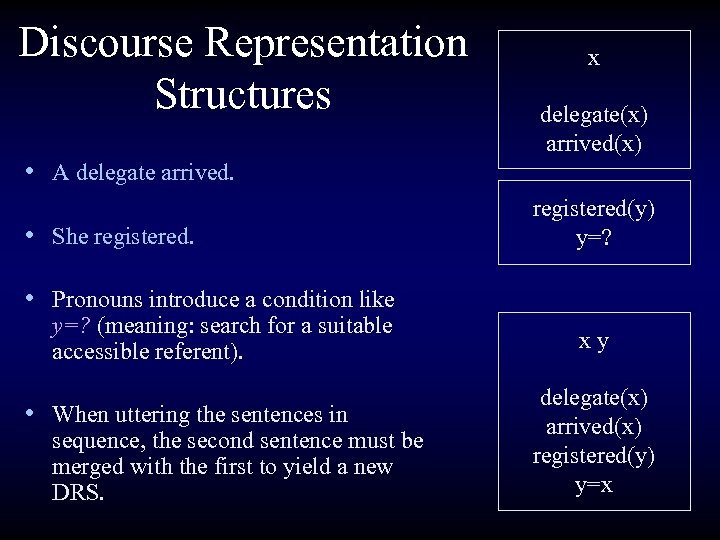

Discourse Representation Structures x delegate(x) arrived(x) • A delegate arrived. • She registered(y) y=? • Pronouns introduce a condition like y=? (meaning: search for a suitable accessible referent). • When uttering the sentences in sequence, the second sentence must be merged with the first to yield a new DRS. xy delegate(x) arrived(x) registered(y) y=x

Discourse Representation Structures x delegate(x) arrived(x) • A delegate arrived. • She registered(y) y=? • Pronouns introduce a condition like y=? (meaning: search for a suitable accessible referent). • When uttering the sentences in sequence, the second sentence must be merged with the first to yield a new DRS. xy delegate(x) arrived(x) registered(y) y=x

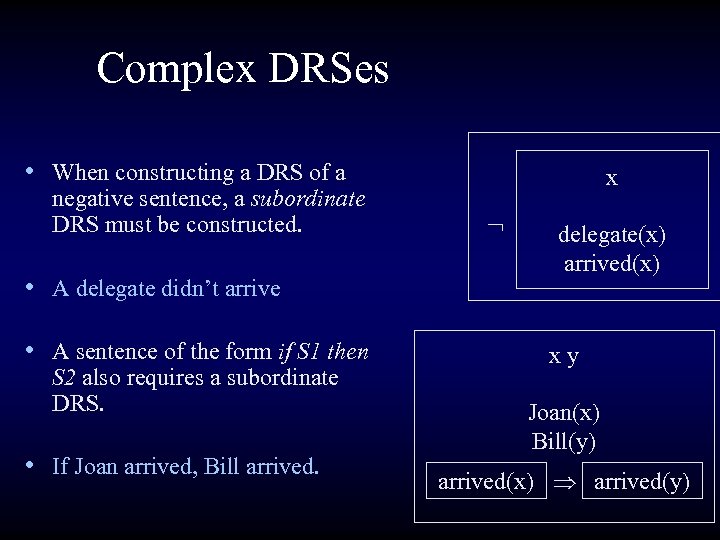

Complex DRSes • When constructing a DRS of a negative sentence, a subordinate DRS must be constructed. • A delegate didn’t arrive • A sentence of the form if S 1 then S 2 also requires a subordinate DRS. • If Joan arrived, Bill arrived. x delegate(x) arrived(x) xy Joan(x) Bill(y) arrived(x) arrived(y)

Complex DRSes • When constructing a DRS of a negative sentence, a subordinate DRS must be constructed. • A delegate didn’t arrive • A sentence of the form if S 1 then S 2 also requires a subordinate DRS. • If Joan arrived, Bill arrived. x delegate(x) arrived(x) xy Joan(x) Bill(y) arrived(x) arrived(y)

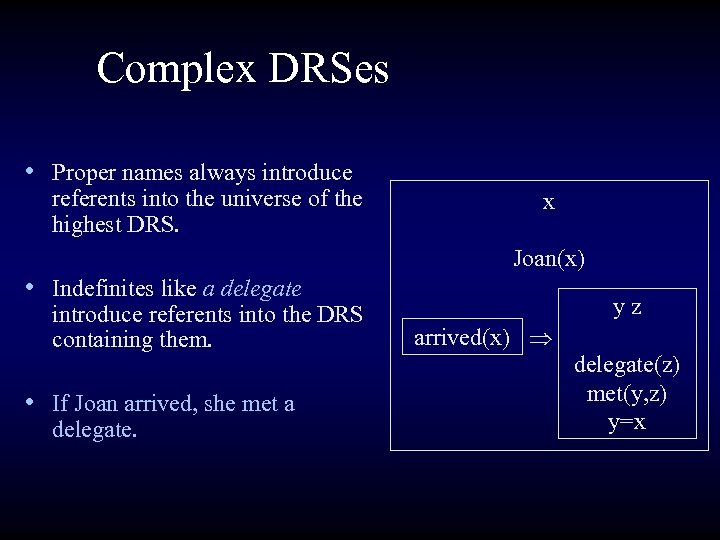

Complex DRSes • Proper names always introduce referents into the universe of the highest DRS. x Joan(x) • Indefinites like a delegate introduce referents into the DRS containing them. • If Joan arrived, she met a delegate. yz arrived(x) delegate(z) met(y, z) y=x

Complex DRSes • Proper names always introduce referents into the universe of the highest DRS. x Joan(x) • Indefinites like a delegate introduce referents into the DRS containing them. • If Joan arrived, she met a delegate. yz arrived(x) delegate(z) met(y, z) y=x

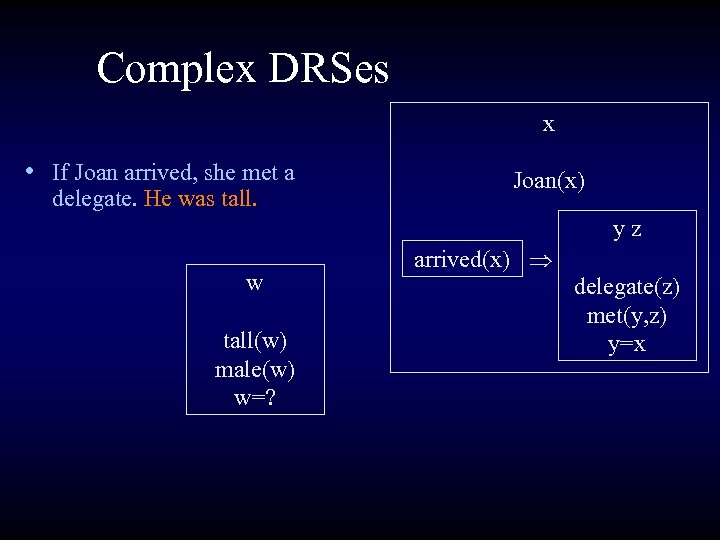

Complex DRSes x • If Joan arrived, she met a delegate. He was tall. Joan(x) yz w tall(w) male(w) w=? arrived(x) delegate(z) met(y, z) y=x

Complex DRSes x • If Joan arrived, she met a delegate. He was tall. Joan(x) yz w tall(w) male(w) w=? arrived(x) delegate(z) met(y, z) y=x

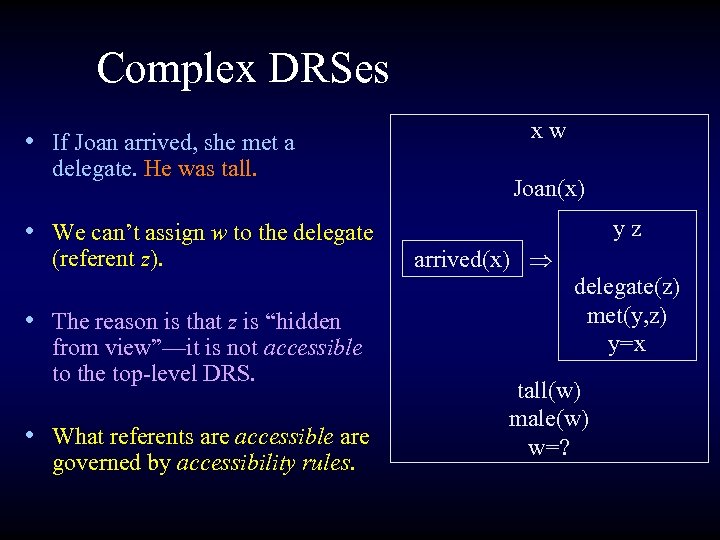

Complex DRSes • If Joan arrived, she met a delegate. He was tall. • We can’t assign w to the delegate (referent z). • The reason is that z is “hidden from view”—it is not accessible to the top-level DRS. • What referents are accessible are governed by accessibility rules. xw Joan(x) yz arrived(x) delegate(z) met(y, z) y=x tall(w) male(w) w=?

Complex DRSes • If Joan arrived, she met a delegate. He was tall. • We can’t assign w to the delegate (referent z). • The reason is that z is “hidden from view”—it is not accessible to the top-level DRS. • What referents are accessible are governed by accessibility rules. xw Joan(x) yz arrived(x) delegate(z) met(y, z) y=x tall(w) male(w) w=?

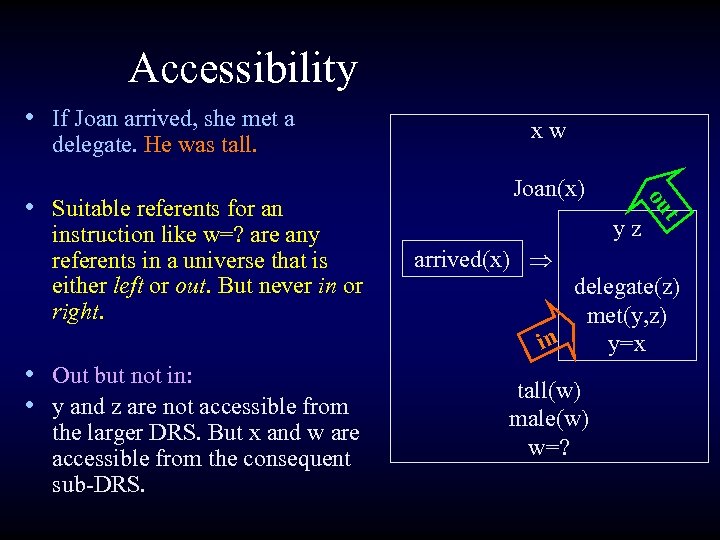

Accessibility • If Joan arrived, she met a delegate. He was tall. instruction like w=? are any referents in a universe that is either left or out. But never in or right. • Out but not in: • y and z are not accessible from the larger DRS. But x and w are accessible from the consequent sub-DRS. Joan(x) yz arrived(x) t ou • Suitable referents for an xw delegate(z) met(y, z) in y=x tall(w) male(w) w=?

Accessibility • If Joan arrived, she met a delegate. He was tall. instruction like w=? are any referents in a universe that is either left or out. But never in or right. • Out but not in: • y and z are not accessible from the larger DRS. But x and w are accessible from the consequent sub-DRS. Joan(x) yz arrived(x) t ou • Suitable referents for an xw delegate(z) met(y, z) in y=x tall(w) male(w) w=?

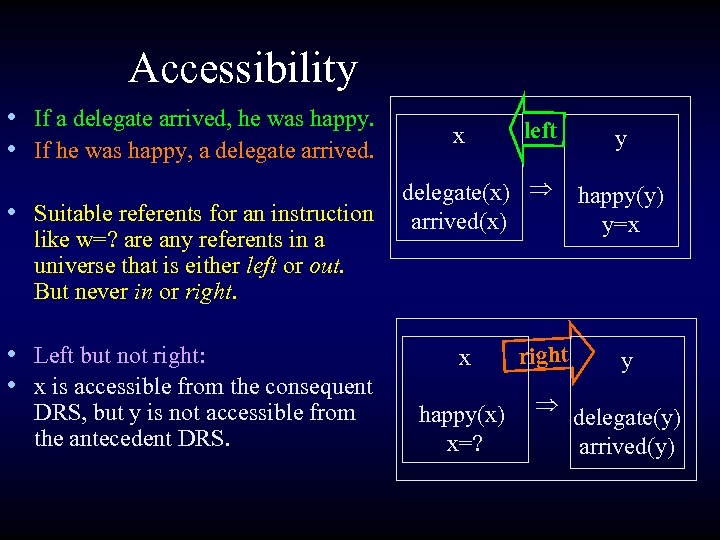

Accessibility • If a delegate arrived, he was happy. • If he was happy, a delegate arrived. • Suitable referents for an instruction like w=? are any referents in a universe that is either left or out. But never in or right. • Left but not right: • x is accessible from the consequent DRS, but y is not accessible from the antecedent DRS. x left delegate(x) arrived(x) x happy(x) x=? right y happy(y) y=x y delegate(y) arrived(y)

Accessibility • If a delegate arrived, he was happy. • If he was happy, a delegate arrived. • Suitable referents for an instruction like w=? are any referents in a universe that is either left or out. But never in or right. • Left but not right: • x is accessible from the consequent DRS, but y is not accessible from the antecedent DRS. x left delegate(x) arrived(x) x happy(x) x=? right y happy(y) y=x y delegate(y) arrived(y)

Sue bought a car. It is fast.

Sue bought a car. It is fast.

If a boy is hungry, he eats.

If a boy is hungry, he eats.

If a boy is tired, he doesn’t play.

If a boy is tired, he doesn’t play.

Pat didn’t buy a textbook. • We’ve been sort of overlooking the fact that a sentence like Pat didn’t buy a textbook is actually ambiguous. • It could mean that Pat bought no textbooks. This is basically what our DRSes predict. • It could also mean that there is a textbook Pat failed to buy.

Pat didn’t buy a textbook. • We’ve been sort of overlooking the fact that a sentence like Pat didn’t buy a textbook is actually ambiguous. • It could mean that Pat bought no textbooks. This is basically what our DRSes predict. • It could also mean that there is a textbook Pat failed to buy.

Unusually wide scope • A phrase like a textbook is a quantifier, and so we expect that it could undergo QR. • Assuming that negation is also a quantifier that can undergo QR (we didn’t treat this in our fragment), we expect the normal interaction between two quantifiers: • A textbook > Not • There is a textbook such that Pat didn’t buy it. • Not > A textbook • It is not the case that there is a textbook that Pat bought.

Unusually wide scope • A phrase like a textbook is a quantifier, and so we expect that it could undergo QR. • Assuming that negation is also a quantifier that can undergo QR (we didn’t treat this in our fragment), we expect the normal interaction between two quantifiers: • A textbook > Not • There is a textbook such that Pat didn’t buy it. • Not > A textbook • It is not the case that there is a textbook that Pat bought.

Unusually wide scope • However, QR is usually limited to its own S: • A fish said [S that Loren likes every book]. • A > every • There is a fish x such that x said that for every book y, Loren likes y. • *Every > A • For every book y, there is a fish x such that x said that for every book y, Loren likes y.

Unusually wide scope • However, QR is usually limited to its own S: • A fish said [S that Loren likes every book]. • A > every • There is a fish x such that x said that for every book y, Loren likes y. • *Every > A • For every book y, there is a fish x such that x said that for every book y, Loren likes y.

![Unusually wide scope • Tracy drinks tea [S if every student calls]. • If Unusually wide scope • Tracy drinks tea [S if every student calls]. • If](https://present5.com/presentation/387a976b48e0e361bc2f019508f570eb/image-25.jpg) Unusually wide scope • Tracy drinks tea [S if every student calls]. • If > Every • If, for every student x, x calls, then Tracy drinks tea. • *Every > If • For every student x, if x calls, then Tracy drinks tea. • Pat didn’t say [S that Tracy bought every textbook]. • Not > Every • *Every > Not

Unusually wide scope • Tracy drinks tea [S if every student calls]. • If > Every • If, for every student x, x calls, then Tracy drinks tea. • *Every > If • For every student x, if x calls, then Tracy drinks tea. • Pat didn’t say [S that Tracy bought every textbook]. • Not > Every • *Every > Not

![Unusually wide scope • Every fish said [S that Loren likes a book]. • Unusually wide scope • Every fish said [S that Loren likes a book]. •](https://present5.com/presentation/387a976b48e0e361bc2f019508f570eb/image-26.jpg) Unusually wide scope • Every fish said [S that Loren likes a book]. • Tracy drinks tea [S if a student calls]. • With indefinite quantifiers like a book and a student, it seems to be possible to interpret them with widest scope, even when QR can’t normally provide widest scope—and it usually feels like it has a meaning like “a certain. ”

Unusually wide scope • Every fish said [S that Loren likes a book]. • Tracy drinks tea [S if a student calls]. • With indefinite quantifiers like a book and a student, it seems to be possible to interpret them with widest scope, even when QR can’t normally provide widest scope—and it usually feels like it has a meaning like “a certain. ”

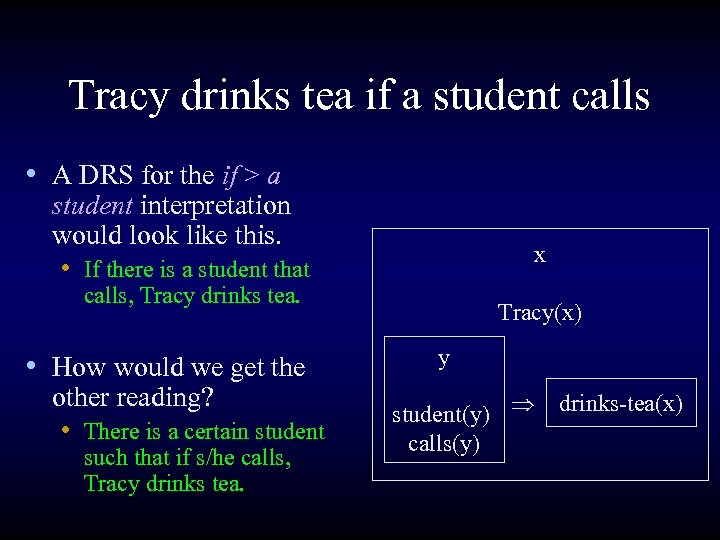

Tracy drinks tea if a student calls • A DRS for the if > a student interpretation would look like this. • If there is a student that x calls, Tracy drinks tea. • How would we get the other reading? • There is a certain student such that if s/he calls, Tracy drinks tea. Tracy(x) y student(y) calls(y) drinks-tea(x)

Tracy drinks tea if a student calls • A DRS for the if > a student interpretation would look like this. • If there is a student that x calls, Tracy drinks tea. • How would we get the other reading? • There is a certain student such that if s/he calls, Tracy drinks tea. Tracy(x) y student(y) calls(y) drinks-tea(x)

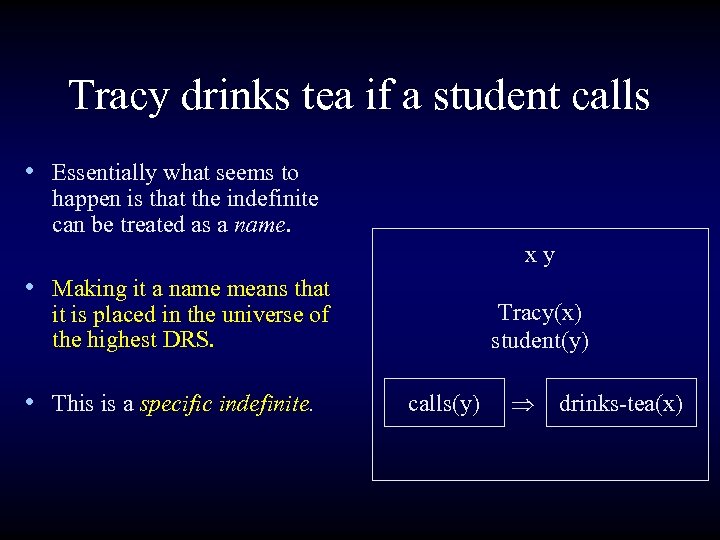

Tracy drinks tea if a student calls • Essentially what seems to happen is that the indefinite can be treated as a name. xy • Making it a name means that Tracy(x) student(y) it is placed in the universe of the highest DRS. • This is a specific indefinite. calls(y) drinks-tea(x)

Tracy drinks tea if a student calls • Essentially what seems to happen is that the indefinite can be treated as a name. xy • Making it a name means that Tracy(x) student(y) it is placed in the universe of the highest DRS. • This is a specific indefinite. calls(y) drinks-tea(x)

![Every • • • Every delegate arrived. Our translation of this was: x[delegate(x) arrived(x)] Every • • • Every delegate arrived. Our translation of this was: x[delegate(x) arrived(x)]](https://present5.com/presentation/387a976b48e0e361bc2f019508f570eb/image-29.jpg) Every • • • Every delegate arrived. Our translation of this was: x[delegate(x) arrived(x)] That is, being a delegate implies having arrived. We can write this as a DRS using the normal x rule for writing arrived(x) conditionals. delegate(x)

Every • • • Every delegate arrived. Our translation of this was: x[delegate(x) arrived(x)] That is, being a delegate implies having arrived. We can write this as a DRS using the normal x rule for writing arrived(x) conditionals. delegate(x)

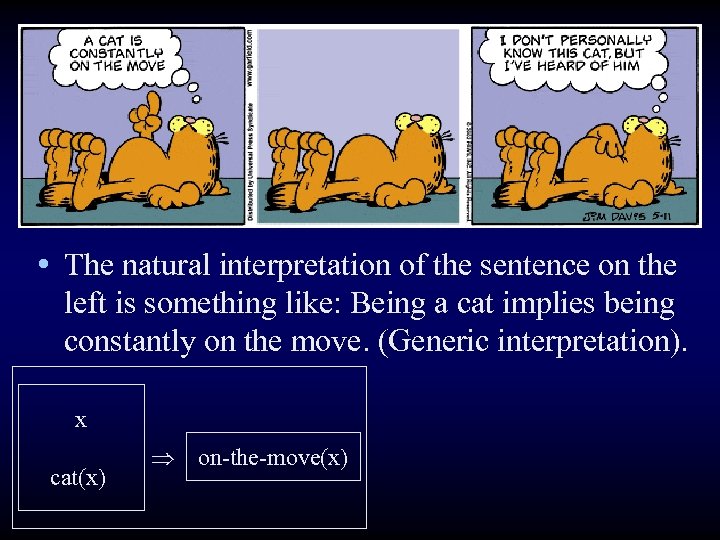

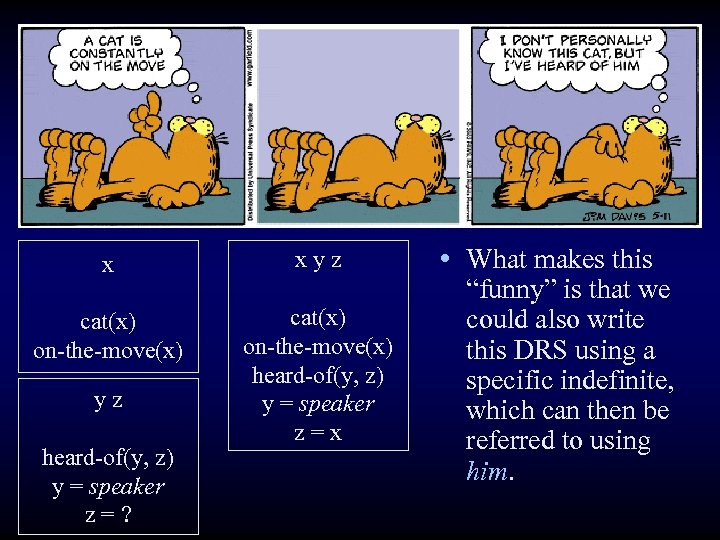

• The natural interpretation of the sentence on the left is something like: Being a cat implies being constantly on the move. (Generic interpretation). x cat(x) on-the-move(x)

• The natural interpretation of the sentence on the left is something like: Being a cat implies being constantly on the move. (Generic interpretation). x cat(x) on-the-move(x)

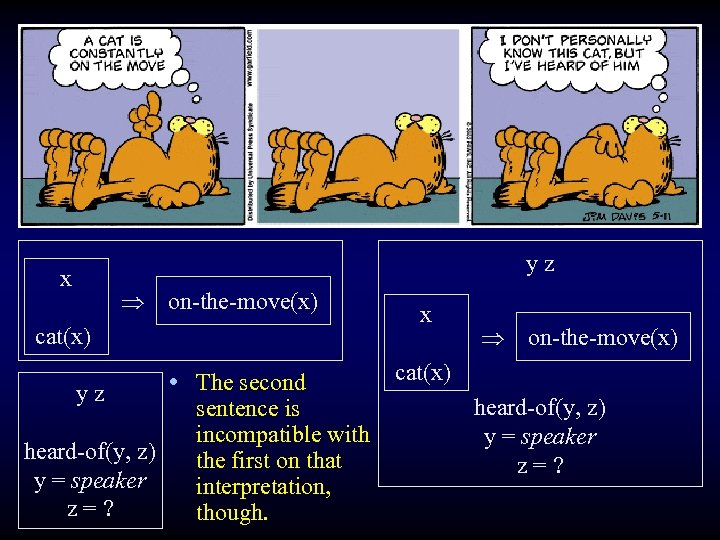

yz x on-the-move(x) cat(x) yz heard-of(y, z) y = speaker z=? • The second sentence is incompatible with the first on that interpretation, though. x on-the-move(x) cat(x) heard-of(y, z) y = speaker z=?

yz x on-the-move(x) cat(x) yz heard-of(y, z) y = speaker z=? • The second sentence is incompatible with the first on that interpretation, though. x on-the-move(x) cat(x) heard-of(y, z) y = speaker z=?

x xyz cat(x) on-the-move(x) heard-of(y, z) y = speaker z=x yz heard-of(y, z) y = speaker z=? • What makes this “funny” is that we could also write this DRS using a specific indefinite, which can then be referred to using him.

x xyz cat(x) on-the-move(x) heard-of(y, z) y = speaker z=x yz heard-of(y, z) y = speaker z=? • What makes this “funny” is that we could also write this DRS using a specific indefinite, which can then be referred to using him.

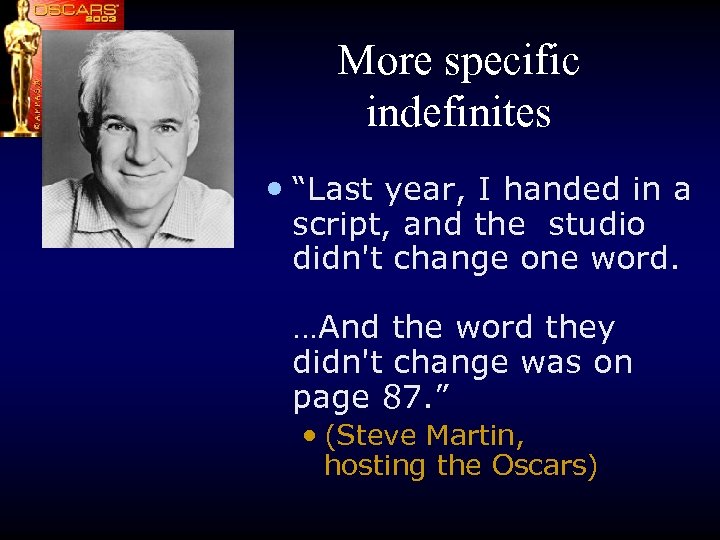

More specific indefinites • “Last year, I handed in a script, and the studio didn't change one word. …And the word they didn't change was on page 87. ” • (Steve Martin, hosting the Oscars)

More specific indefinites • “Last year, I handed in a script, and the studio didn't change one word. …And the word they didn't change was on page 87. ” • (Steve Martin, hosting the Oscars)

DRT • Discourse Representation Theory is a system to account for how we track referents through a discourse—how they are introduced, when they can serve as antecedents for pronouns in later sentences. • The Discourse Representation Structure is a picture of the discourse environment at a given point, updated with each further utterance by merging the information in the new utterance with the information in the discourse environment.

DRT • Discourse Representation Theory is a system to account for how we track referents through a discourse—how they are introduced, when they can serve as antecedents for pronouns in later sentences. • The Discourse Representation Structure is a picture of the discourse environment at a given point, updated with each further utterance by merging the information in the new utterance with the information in the discourse environment.

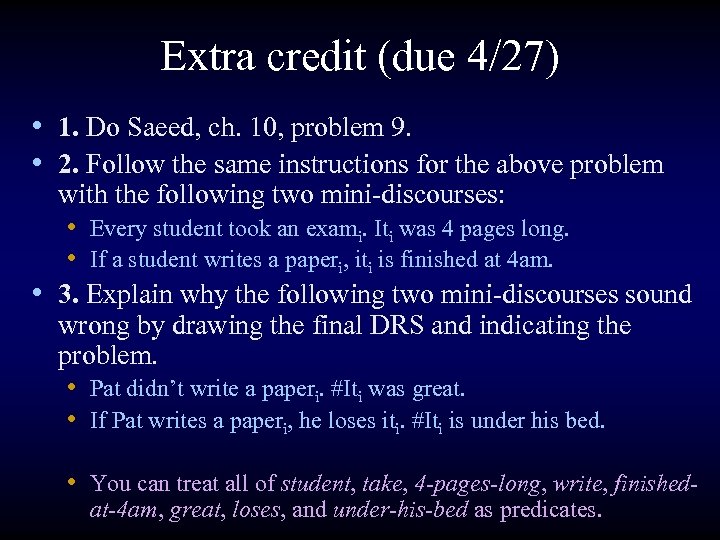

Extra credit (due 4/27) • 1. Do Saeed, ch. 10, problem 9. • 2. Follow the same instructions for the above problem with the following two mini-discourses: • Every student took an exami. Iti was 4 pages long. • If a student writes a paperi, iti is finished at 4 am. • 3. Explain why the following two mini-discourses sound wrong by drawing the final DRS and indicating the problem. • Pat didn’t write a paperi. #Iti was great. • If Pat writes a paperi, he loses iti. #Iti is under his bed. • You can treat all of student, take, 4 -pages-long, write, finishedat-4 am, great, loses, and under-his-bed as predicates.

Extra credit (due 4/27) • 1. Do Saeed, ch. 10, problem 9. • 2. Follow the same instructions for the above problem with the following two mini-discourses: • Every student took an exami. Iti was 4 pages long. • If a student writes a paperi, iti is finished at 4 am. • 3. Explain why the following two mini-discourses sound wrong by drawing the final DRS and indicating the problem. • Pat didn’t write a paperi. #Iti was great. • If Pat writes a paperi, he loses iti. #Iti is under his bed. • You can treat all of student, take, 4 -pages-long, write, finishedat-4 am, great, loses, and under-his-bed as predicates.