3e3ae83205112c3171a4998dfd30988b.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 113

Carnegie Mellon Processes Slides adapted from: Randy Bryant of Carnegie Mellon University

Carnegie Mellon Processes ¢ Definition: A process is an instance of a running program. § One of the most profound ideas in computer science § Not the same as “program” or “processor” ¢ Process provides each program with two key abstractions: § Logical control flow Each program seems to have exclusive use of the CPU § Private virtual address space § Each program seems to have exclusive use of main memory § ¢ How are these Illusions maintained? § Process executions interleaved (multitasking) § Address spaces managed by virtual memory system

Carnegie Mellon What is a process? ¢ A process is the OS's abstraction for execution § A process represents a single running application on the system ¢ Process has three main components: 1. Address space The memory that the process can access § Consists of various pieces: the program code, static variables, heap, stack, etc. 2. Processor state § The CPU registers associated with the running process § Includes general purpose registers, program counter, stack pointer, etc. 3. OS resources § Various OS state associated with the process § Examples: open files, network sockets, etc. §

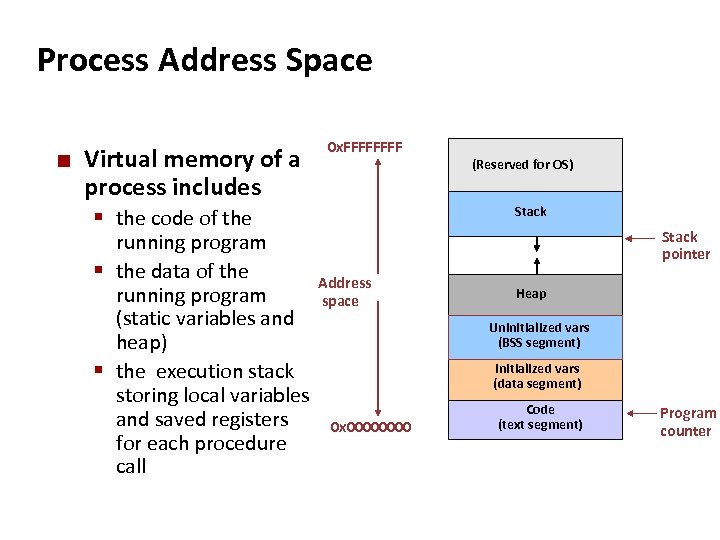

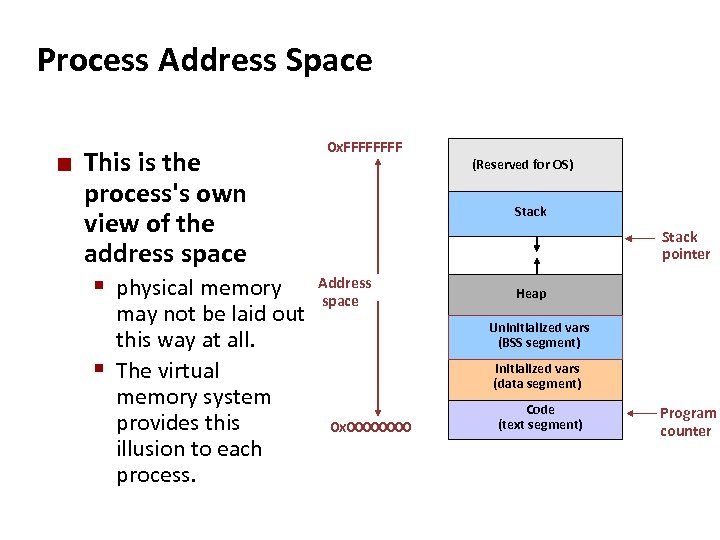

Carnegie Mellon Process Address Space ¢ Virtual memory of a process includes § the code of the 0 x. FFFF running program § the data of the Address running program space (static variables and heap) § the execution stack storing local variables and saved registers 0 x 0000 for each procedure call (Reserved for OS) Stack pointer Heap Uninitialized vars (BSS segment) Initialized vars (data segment) Code (text segment) Program counter

Carnegie Mellon Process Address Space ¢ This is the process's own view of the address space § physical memory may not be laid out this way at all. § The virtual memory system provides this illusion to each process. 0 x. FFFF (Reserved for OS) Stack pointer Address space Heap Uninitialized vars (BSS segment) Initialized vars (data segment) 0 x 0000 Code (text segment) Program counter

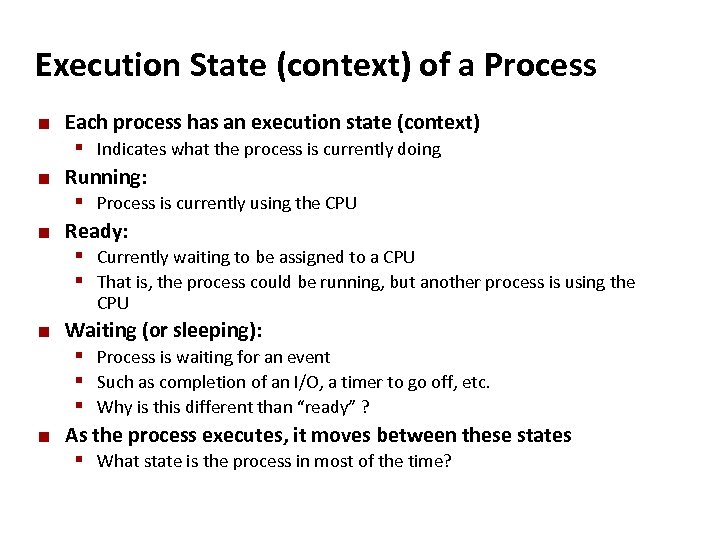

Carnegie Mellon Execution State (context) of a Process ¢ ¢ ¢ Each process has an execution state (context) § Indicates what the process is currently doing Running: § Process is currently using the CPU Ready: § Currently waiting to be assigned to a CPU § That is, the process could be running, but another process is using the CPU ¢ ¢ Waiting (or sleeping): § Process is waiting for an event § Such as completion of an I/O, a timer to go off, etc. § Why is this different than “ready” ? As the process executes, it moves between these states § What state is the process in most of the time?

Carnegie Mellon Process State (Context) Transitions ¢ What causes schedule and unschedule transitions? New create Ready unschedule Terminated kill or exit I/O done schedule Running Waiting I/O, page fault, etc.

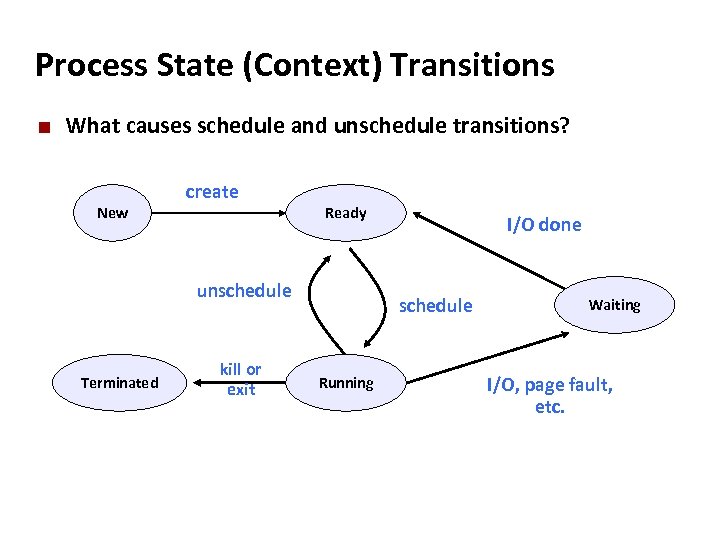

Carnegie Mellon Process Control Block ¢ ¢ OS maintains a Process Control Block (PCB) for each process The PCB is a big data structure with many fields: § Process ID § User ID § Execution state ready, running, or waiting Saved CPU state § CPU registers saved the last time the process was suspended. OS resources § Open files, network sockets, etc. Memory management info Scheduling priority § Give some processes higher priority than others Accounting information § Total CPU time, memory usage, etc. § § §

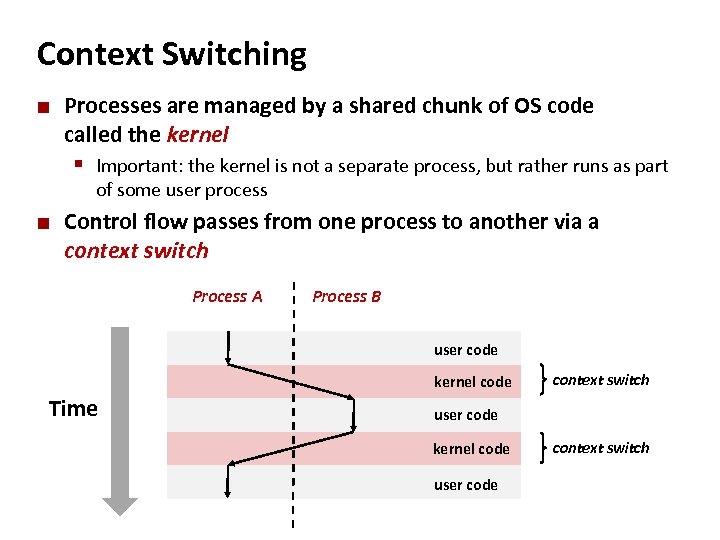

Carnegie Mellon Context Switching ¢ Processes are managed by a shared chunk of OS code called the kernel § Important: the kernel is not a separate process, but rather runs as part of some user process ¢ Control flow passes from one process to another via a context switch Process A Process B user code kernel code Time context switch user code kernel code user code context switch

Carnegie Mellon Context Switching in Linux Process A time Process A is happily running along. . .

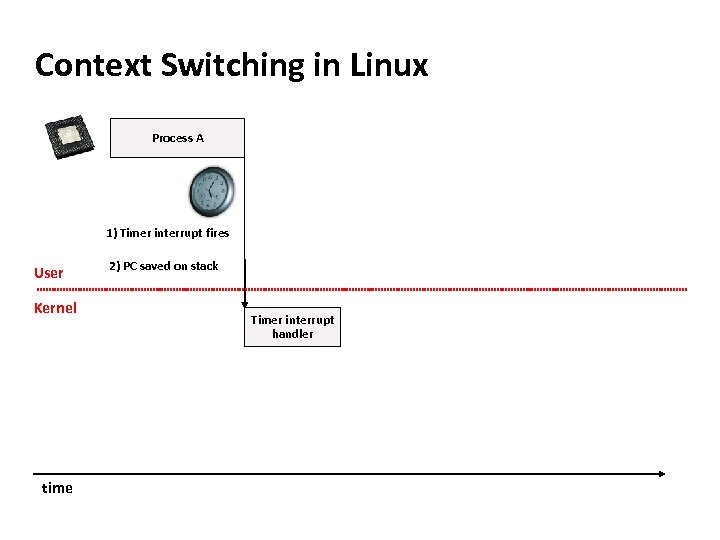

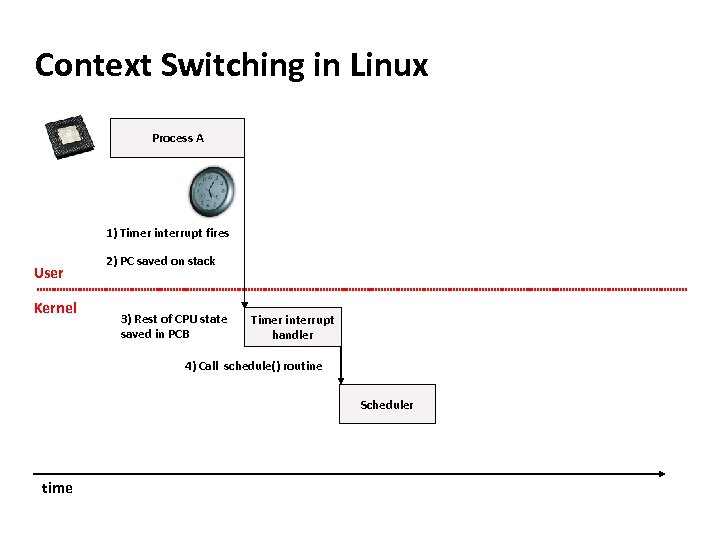

Carnegie Mellon Context Switching in Linux Process A 1) Timer interrupt fires User Kernel time 2) PC saved on stack Timer interrupt handler

Carnegie Mellon Context Switching in Linux Process A 1) Timer interrupt fires User Kernel 2) PC saved on stack 3) Rest of CPU state saved in PCB Timer interrupt handler 4) Call schedule() routine Scheduler time

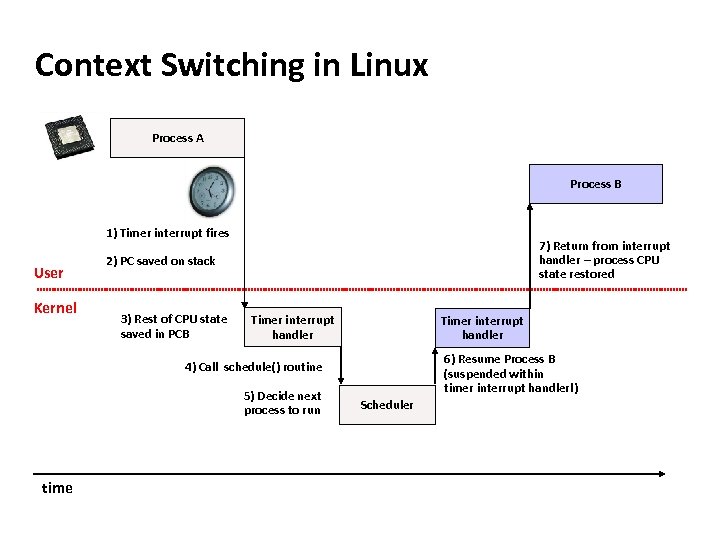

Carnegie Mellon Context Switching in Linux Process A Process B 1) Timer interrupt fires User Kernel 7) Return from interrupt handler – process CPU state restored 2) PC saved on stack 3) Rest of CPU state saved in PCB Timer interrupt handler 6) Resume Process B (suspended within timer interrupt handler!) 4) Call schedule() routine 5) Decide next process to run time Scheduler

Carnegie Mellon Context Switch Overhead ¢ Context switches are not cheap § Generally have a lot of CPU state to save and restore § Also must update various flags in the PCB § Picking the next process to run – scheduling – is also expensive ¢ Context switch overhead in Linux § About 5 -7 usec § This is equivalent to about 10, 000 CPU cycles!

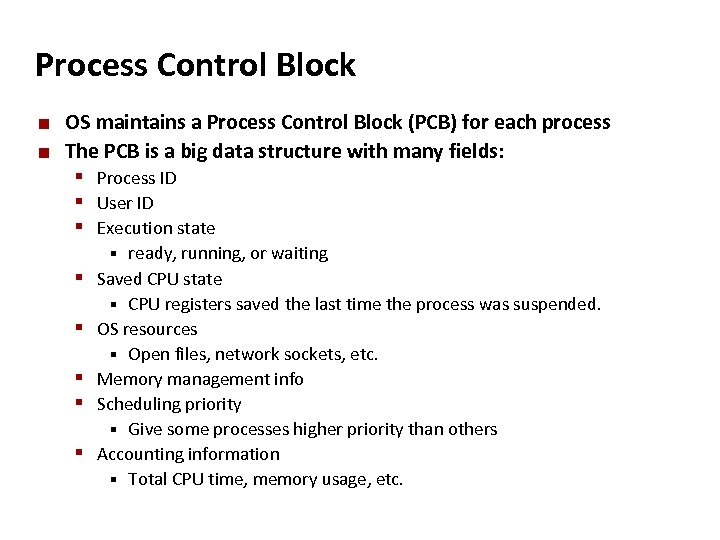

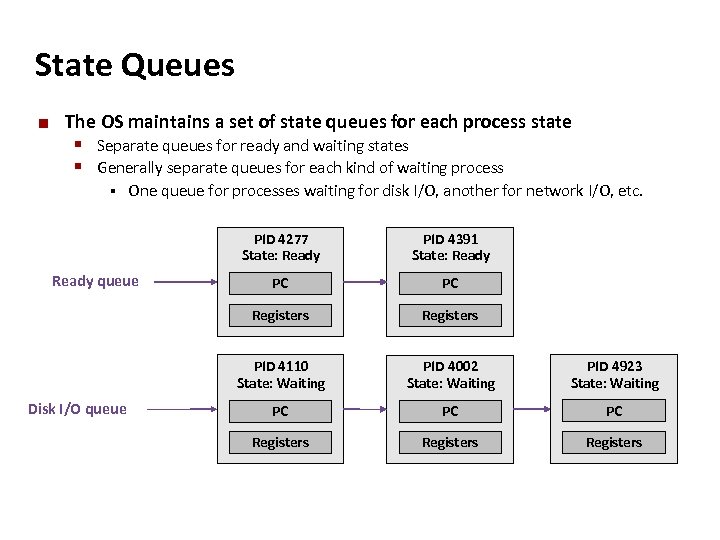

Carnegie Mellon State Queues ¢ The OS maintains a set of state queues for each process state § Separate queues for ready and waiting states § Generally separate queues for each kind of waiting process § One queue for processes waiting for disk I/O, another for network I/O, etc. PID 4277 State: Ready PC Registers PID 4110 State: Waiting Disk I/O queue PC Registers Ready queue PID 4391 State: Ready PID 4002 State: Waiting PID 4923 State: Waiting PC PC PC Registers

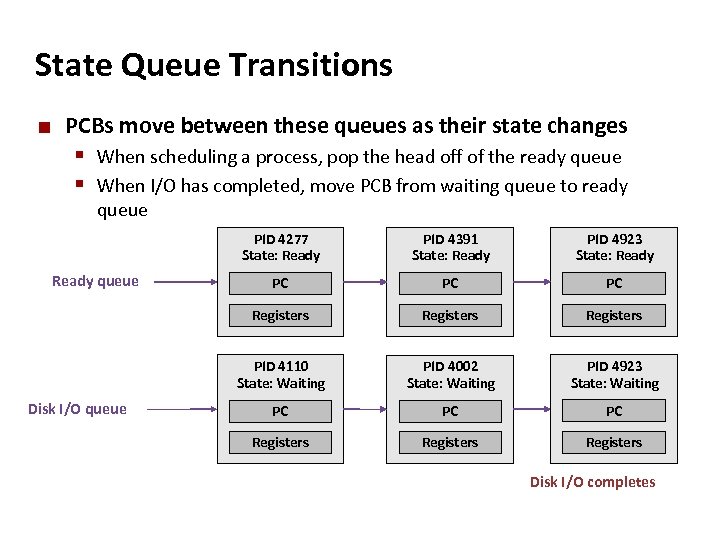

Carnegie Mellon State Queue Transitions ¢ PCBs move between these queues as their state changes § When scheduling a process, pop the head off of the ready queue § When I/O has completed, move PCB from waiting queue to ready queue PID 4277 State: Ready PC PC PC Registers PID 4110 State: Waiting Disk I/O queue PID 4923 State: Ready Registers Ready queue PID 4391 State: Ready PID 4002 State: Waiting PID 4923 State: Waiting PC PC PC Registers Disk I/O completes

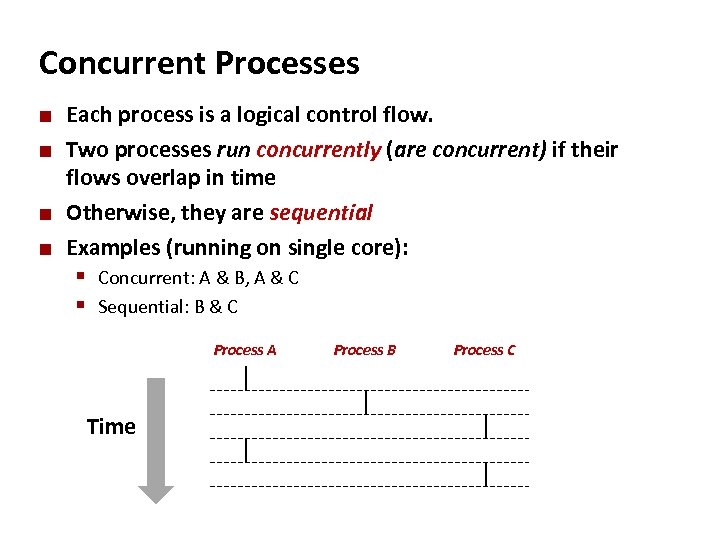

Carnegie Mellon Concurrent Processes ¢ ¢ Each process is a logical control flow. Two processes run concurrently (are concurrent) if their flows overlap in time Otherwise, they are sequential Examples (running on single core): § Concurrent: A & B, A & C § Sequential: B & C Process A Time Process B Process C

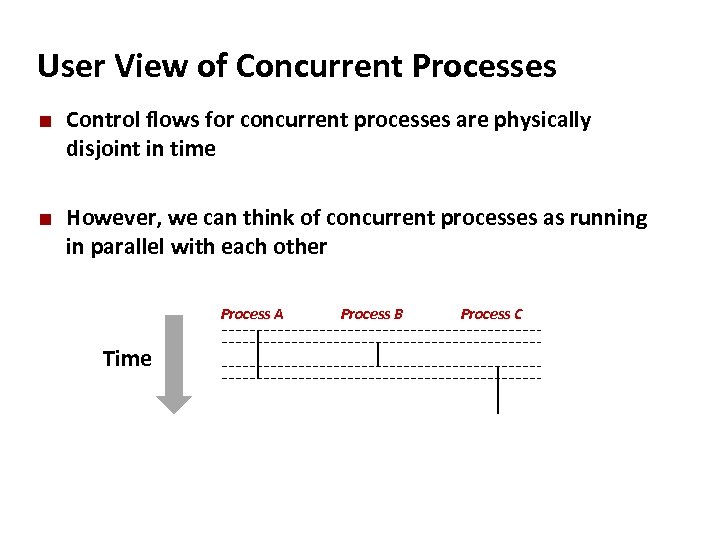

Carnegie Mellon User View of Concurrent Processes ¢ ¢ Control flows for concurrent processes are physically disjoint in time However, we can think of concurrent processes as running in parallel with each other Process A Time Process B Process C

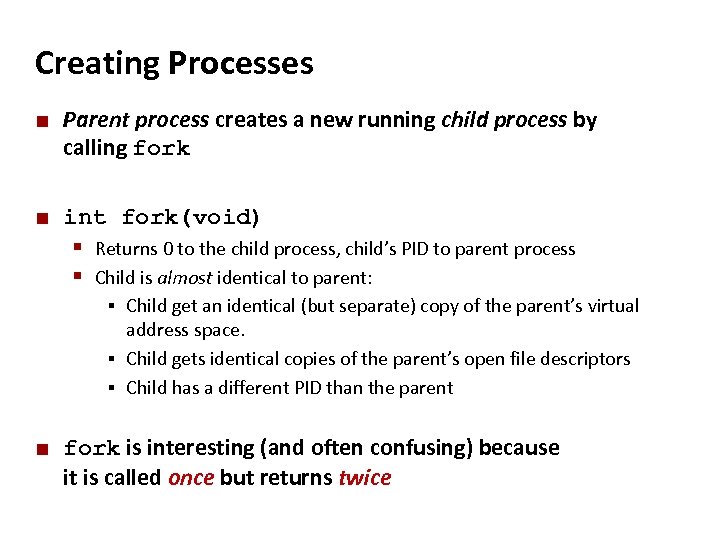

Carnegie Mellon Creating Processes ¢ ¢ Parent process creates a new running child process by calling fork int fork(void) § Returns 0 to the child process, child’s PID to parent process § Child is almost identical to parent: Child get an identical (but separate) copy of the parent’s virtual address space. § Child gets identical copies of the parent’s open file descriptors § Child has a different PID than the parent § ¢ fork is interesting (and often confusing) because it is called once but returns twice

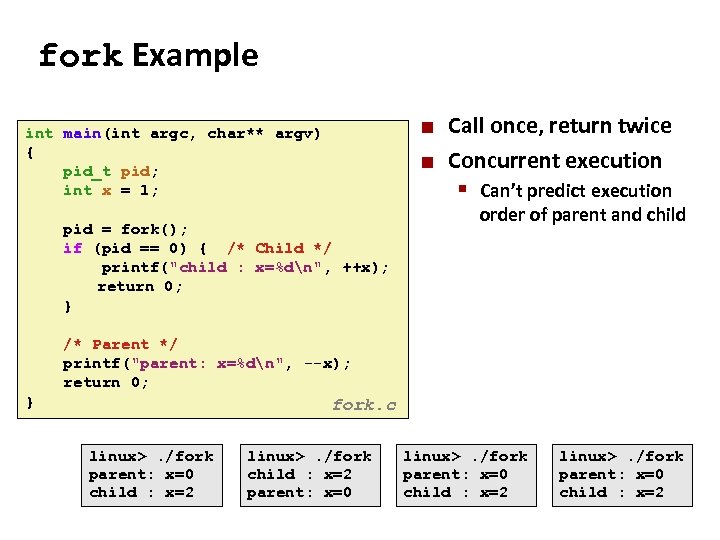

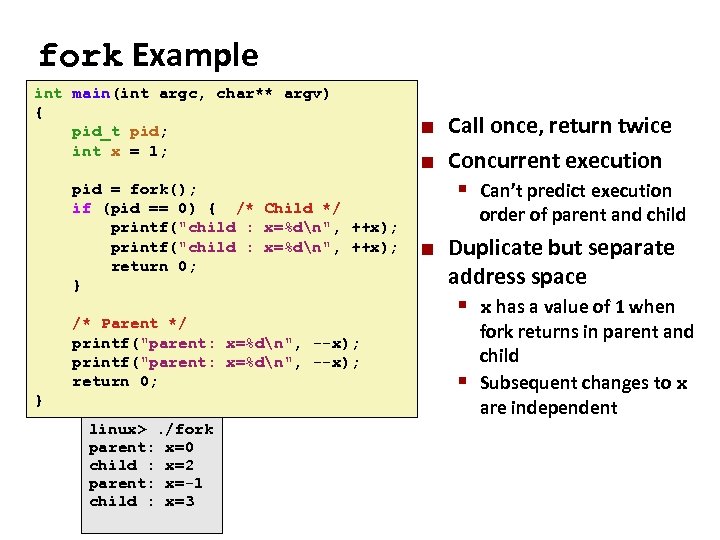

Carnegie Mellon fork Example int main(int argc, char** argv) { pid_t pid; int x = 1; pid = fork(); if (pid == 0) { /* Child */ printf("child : x=%dn", ++x); return 0; } ¢ ¢ Call once, return twice Concurrent execution § Can’t predict execution order of parent and child /* Parent */ printf("parent: x=%dn", --x); return 0; } fork. c linux>. /fork parent: x=0 child : x=2 linux>. /fork child : x=2 parent: x=0 linux>. /fork parent: x=0 child : x=2

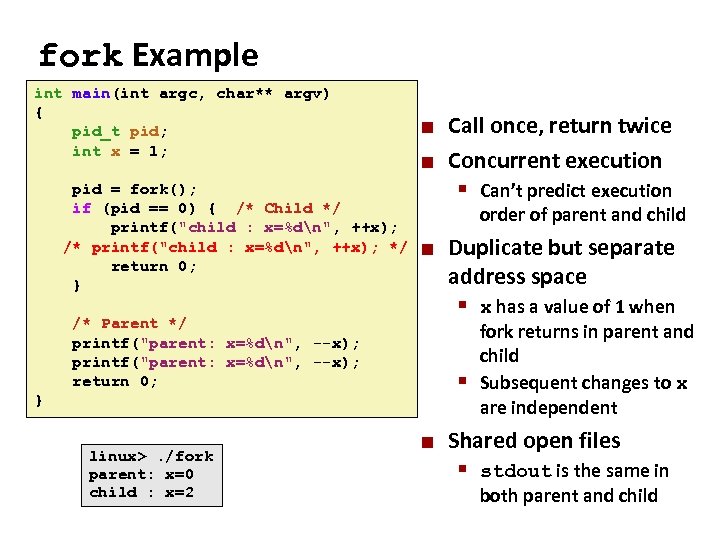

Carnegie Mellon fork Example int main(int argc, char** argv) { pid_t pid; int x = 1; ¢ ¢ Call once, return twice Concurrent execution pid = fork(); § Can’t predict execution if (pid == 0) { /* Child */ order of parent and child printf("child : x=%dn", ++x); ¢ Duplicate but separate return 0; address space } /* Parent */ printf("parent: x=%dn", --x); return 0; } fork. c linux>. /fork parent: x=0 linux>. /fork child : x=2 parent: x=0 parent: x=-1 child : x=2 child : x=3 § x has a value of 1 when fork returns in parent and child § Subsequent changes to x are independent

Carnegie Mellon fork Example int main(int argc, char** argv) { pid_t pid; int x = 1; ¢ ¢ Call once, return twice Concurrent execution pid = fork(); § Can’t predict execution if (pid == 0) { /* Child */ order of parent and child printf("child : x=%dn", ++x); /* printf("child : x=%dn", ++x); */ ¢ Duplicate but separate return 0; address space } § x has a value of 1 when /* Parent */ printf("parent: x=%dn", --x); return 0; } fork. c linux>. /fork parent: x=0 child : x=2 fork returns in parent and child § Subsequent changes to x are independent ¢ Shared open files § stdout is the same in both parent and child

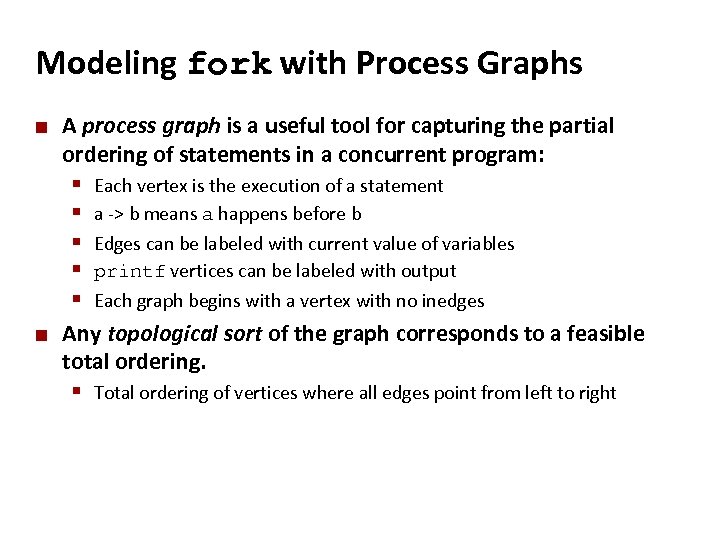

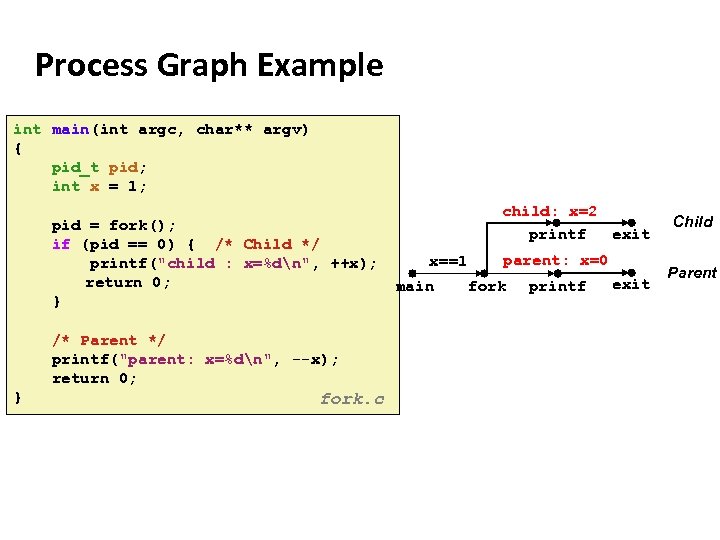

Carnegie Mellon Modeling fork with Process Graphs ¢ A process graph is a useful tool for capturing the partial ordering of statements in a concurrent program: § § § ¢ Each vertex is the execution of a statement a -> b means a happens before b Edges can be labeled with current value of variables printf vertices can be labeled with output Each graph begins with a vertex with no inedges Any topological sort of the graph corresponds to a feasible total ordering. § Total ordering of vertices where all edges point from left to right

Carnegie Mellon Process Graph Example int main(int argc, char** argv) { pid_t pid; int x = 1; child: x=2 printf exit pid = fork(); if (pid == 0) { /* Child */ parent: x=0 x==1 printf("child : x=%dn", ++x); return 0; exit main fork printf } /* Parent */ printf("parent: x=%dn", --x); return 0; } fork. c Child Parent

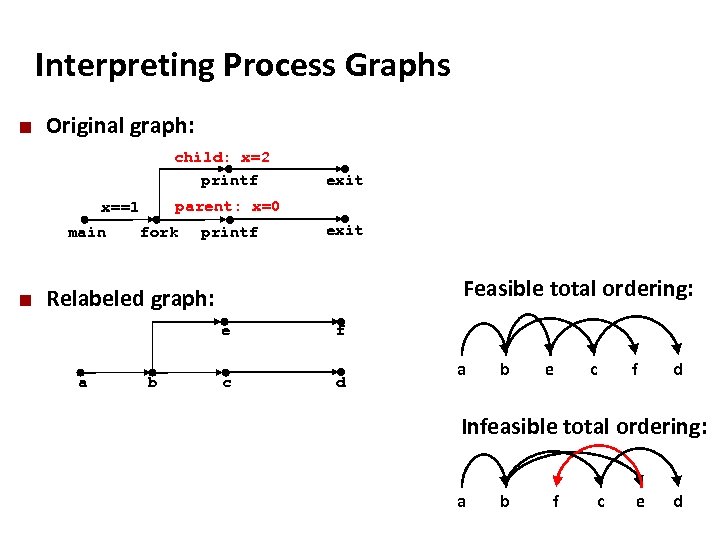

Carnegie Mellon Interpreting Process Graphs ¢ Original graph: child: x=2 printf parent: x=0 x==1 main ¢ exit fork printf exit Feasible total ordering: Relabeled graph: e a b f c d a b e c f d Infeasible total ordering: a b f c e d

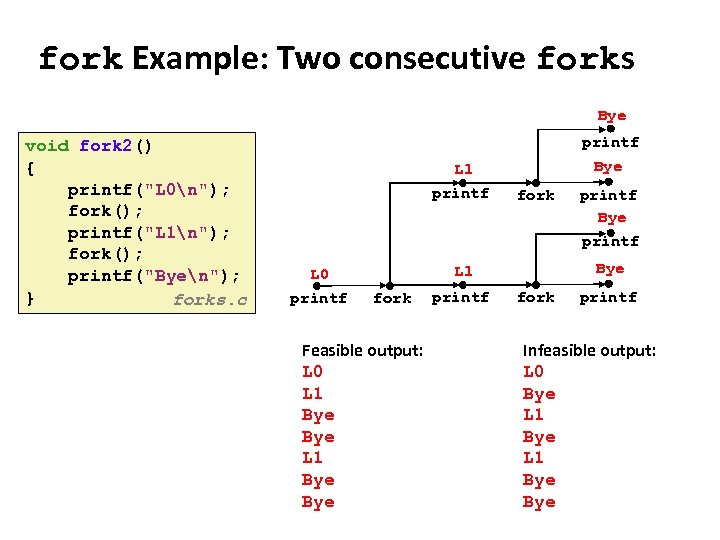

Carnegie Mellon fork Example: Two consecutive forks Bye void fork 2() { printf("L 0n"); fork(); printf("L 1n"); fork(); printf("Byen"); } forks. c printf L 1 printf L 0 printf Bye fork Bye L 1 fork Feasible output: L 0 L 1 Bye Bye printf fork printf Infeasible output: L 0 Bye L 1 Bye

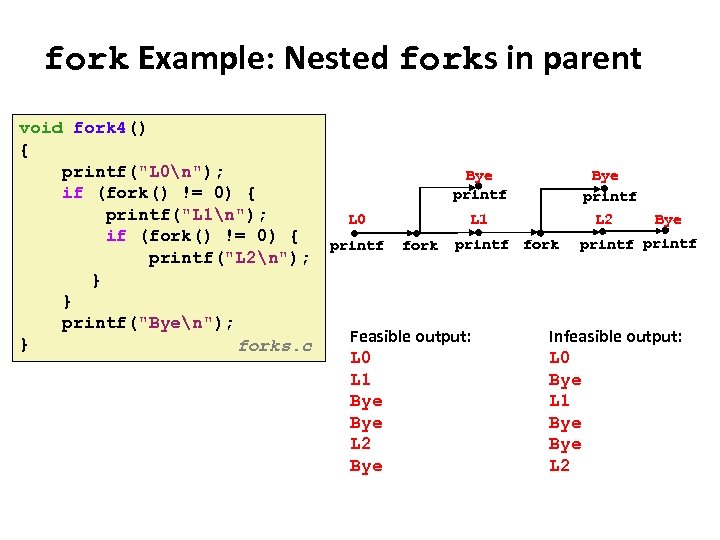

Carnegie Mellon fork Example: Nested forks in parent void fork 4() { printf("L 0n"); Bye if (fork() != 0) { printf printf("L 1n"); L 0 L 1 L 2 Bye if (fork() != 0) { printf fork printf printf("L 2n"); } } printf("Byen"); Feasible output: Infeasible output: } forks. c L 0 L 1 Bye Bye L 2

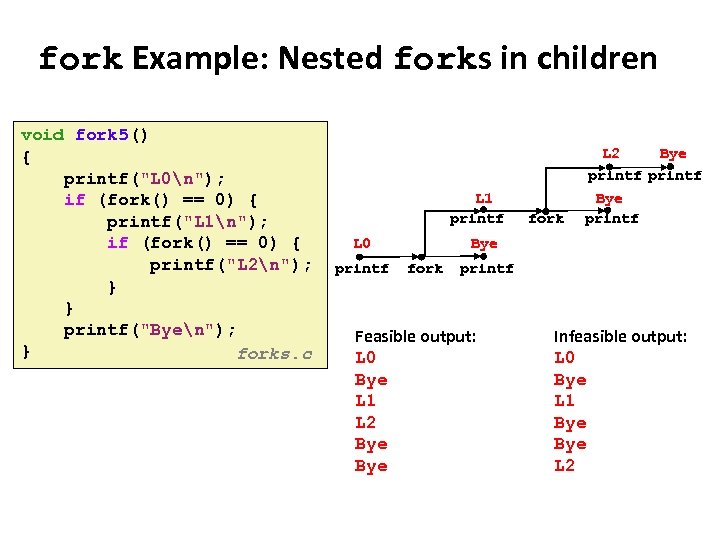

Carnegie Mellon fork Example: Nested forks in children void fork 5() { printf("L 0n"); if (fork() == 0) { printf("L 1n"); if (fork() == 0) { printf("L 2n"); } } printf("Byen"); } forks. c L 2 Bye printf L 1 printf L 0 printf fork Bye printf Bye fork printf Feasible output: L 0 Bye L 1 L 2 Bye Infeasible output: L 0 Bye L 1 Bye L 2

Carnegie Mellon Why have fork() at all? ¢ ¢ ¢ Why make a copy of the parent process? Don't you usually want to start a new program instead? Where might “cloning” the parent be useful? § Web server – make a copy for each incoming connection § Parallel processing – set up initial state, fork off multiple copies to do work ¢ UNIX philosophy: System calls should be minimal. § Don't overload system calls with extra functionality if it is not always needed. § Better to provide a flexible set of simple primitives and let programmers combine them in useful ways.

Carnegie Mellon What if fork’ing gets out of control? void forkbomb() { while (1) fork(); } //takes over //the computer void main(){while(1); } this doesn’t take over computer

Carnegie Mellon Memory concerns OS aggressively tries to share memory between processes. § Especially processes that are fork()'d copies of each other Copies of a parent process do not actually get a private copy of the address space. . . §. . . though that is the illusion that each process gets. § Instead, they share the same physical memory, until one of them makes a change (COW: copy-on-write). The virtual memory system is behind these tricks. § We will discuss this in much detail later in the course

Carnegie Mellon Terminating Processes ¢ Process becomes terminated for one of three reasons: § Receiving a signal whose default action is to terminate (more later) § Returning from the main routine § Calling the exit function ¢ void exit(int status) § Terminates with an exit status of status § Convention: normal return status is 0, nonzero on error § Another way to explicitly set the exit status is to return an integer value from the main routine ¢ exit is called once but never returns. atexit() registers functions to be executed upon exit void cleanup(void) { printf("cleaning upn"); } void fork() { atexit(cleanup); fork(); exit(0); }

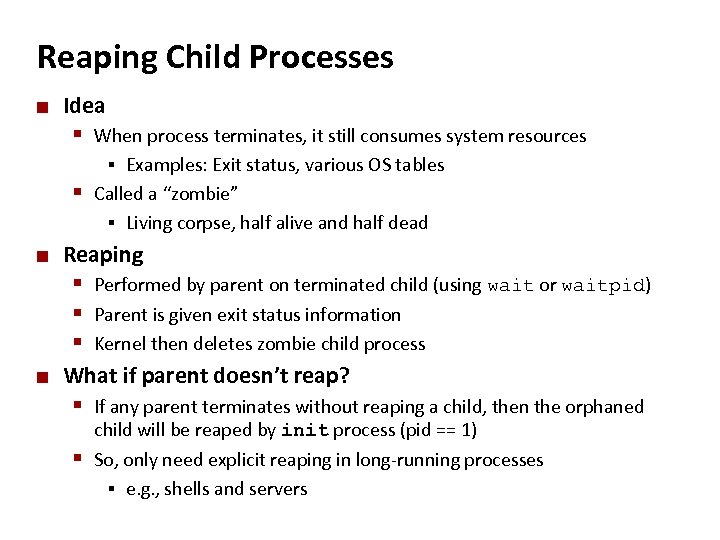

Carnegie Mellon Reaping Child Processes ¢ Idea § When process terminates, it still consumes system resources Examples: Exit status, various OS tables § Called a “zombie” § Living corpse, half alive and half dead § ¢ Reaping § Performed by parent on terminated child (using wait or waitpid) § Parent is given exit status information § Kernel then deletes zombie child process ¢ What if parent doesn’t reap? § If any parent terminates without reaping a child, then the orphaned child will be reaped by init process (pid == 1) § So, only need explicit reaping in long-running processes § e. g. , shells and servers

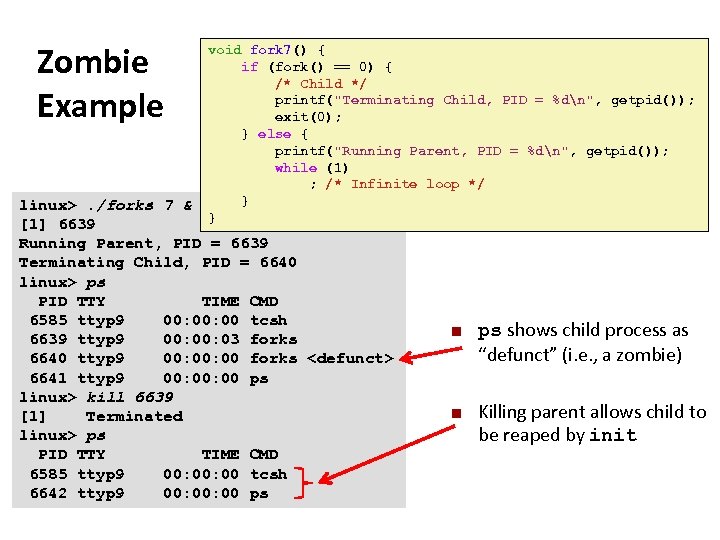

Carnegie Mellon Zombie Example void fork 7() { if (fork() == 0) { /* Child */ printf("Terminating Child, PID = %dn", getpid()); exit(0); } else { printf("Running Parent, PID = %dn", getpid()); while (1) ; /* Infinite loop */ } } forks. c linux>. /forks 7 & [1] 6639 Running Parent, PID = 6639 Terminating Child, PID = 6640 linux> ps PID TTY TIME CMD 6585 ttyp 9 00: 00 tcsh 6639 ttyp 9 00: 03 forks 6640 ttyp 9 00: 00 forks <defunct> 6641 ttyp 9 00: 00 ps linux> kill 6639 [1] Terminated linux> ps PID TTY TIME CMD 6585 ttyp 9 00: 00 tcsh 6642 ttyp 9 00: 00 ps ¢ ¢ ps shows child process as “defunct” (i. e. , a zombie) Killing parent allows child to be reaped by init

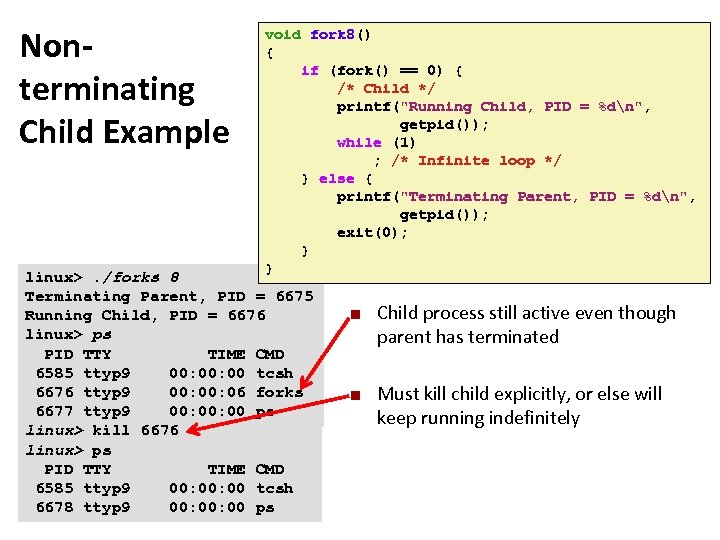

Carnegie Mellon Nonterminating Child Example void fork 8() { if (fork() == 0) { /* Child */ printf("Running Child, PID = %dn", getpid()); while (1) ; /* Infinite loop */ } else { printf("Terminating Parent, PID = %dn", getpid()); exit(0); } } forks. c linux>. /forks 8 Terminating Parent, PID = 6675 Running Child, PID = 6676 linux> ps PID TTY TIME CMD 6585 ttyp 9 00: 00 tcsh 6676 ttyp 9 00: 06 forks 6677 ttyp 9 00: 00 ps linux> kill 6676 linux> ps PID TTY TIME CMD 6585 ttyp 9 00: 00 tcsh 6678 ttyp 9 00: 00 ps ¢ ¢ Child process still active even though parent has terminated Must kill child explicitly, or else will keep running indefinitely

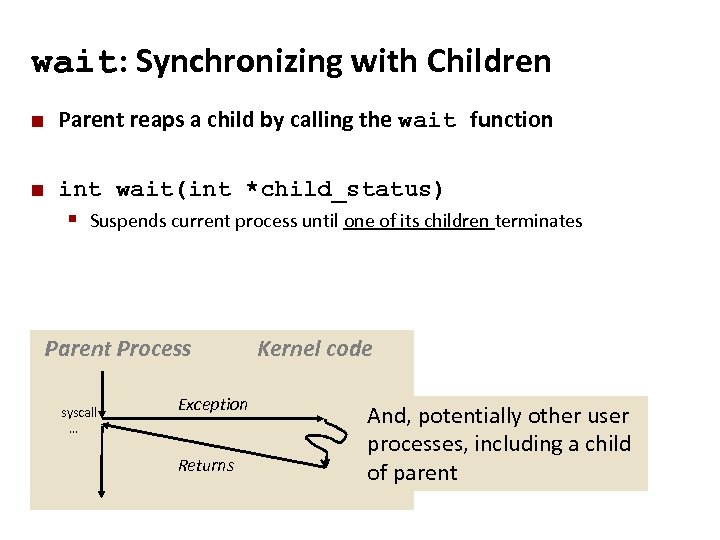

Carnegie Mellon wait: Synchronizing with Children ¢ Parent reaps a child by calling the wait function ¢ int wait(int *child_status) § Suspends current process until one of its children terminates Parent Process syscall … Exception Returns Kernel code And, potentially other user processes, including a child of parent

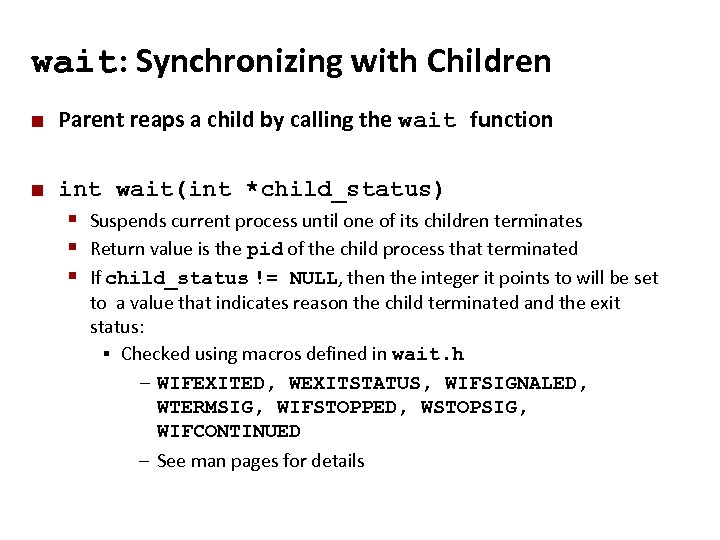

Carnegie Mellon wait: Synchronizing with Children ¢ Parent reaps a child by calling the wait function ¢ int wait(int *child_status) § Suspends current process until one of its children terminates § Return value is the pid of the child process that terminated § If child_status != NULL, then the integer it points to will be set to a value that indicates reason the child terminated and the exit status: § Checked using macros defined in wait. h – WIFEXITED, WEXITSTATUS, WIFSIGNALED, WTERMSIG, WIFSTOPPED, WSTOPSIG, WIFCONTINUED – See man pages for details

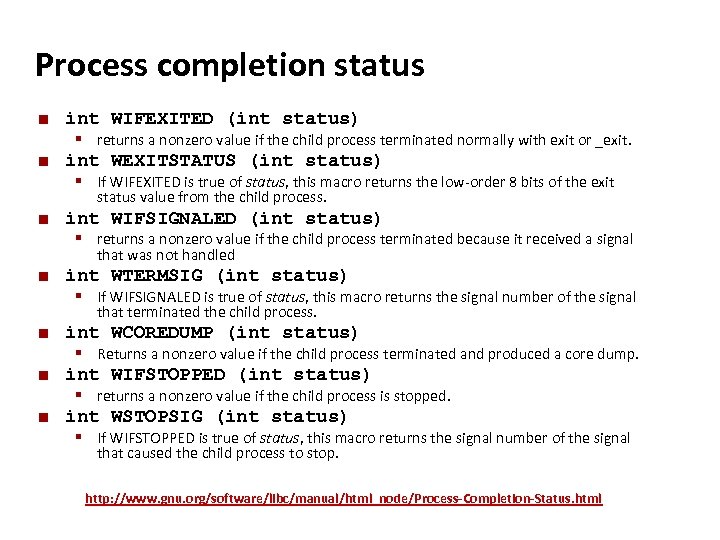

Carnegie Mellon Process completion status ¢ ¢ int WIFEXITED (int status) § returns a nonzero value if the child process terminated normally with exit or _exit. int WEXITSTATUS (int status) § If WIFEXITED is true of status, this macro returns the low-order 8 bits of the exit status value from the child process. ¢ int WIFSIGNALED (int status) § returns a nonzero value if the child process terminated because it received a signal that was not handled ¢ int WTERMSIG (int status) § If WIFSIGNALED is true of status, this macro returns the signal number of the signal that terminated the child process. ¢ ¢ ¢ int WCOREDUMP (int status) § Returns a nonzero value if the child process terminated and produced a core dump. int WIFSTOPPED (int status) § returns a nonzero value if the child process is stopped. int WSTOPSIG (int status) § If WIFSTOPPED is true of status, this macro returns the signal number of the signal that caused the child process to stop. http: //www. gnu. org/software/libc/manual/html_node/Process-Completion-Status. html

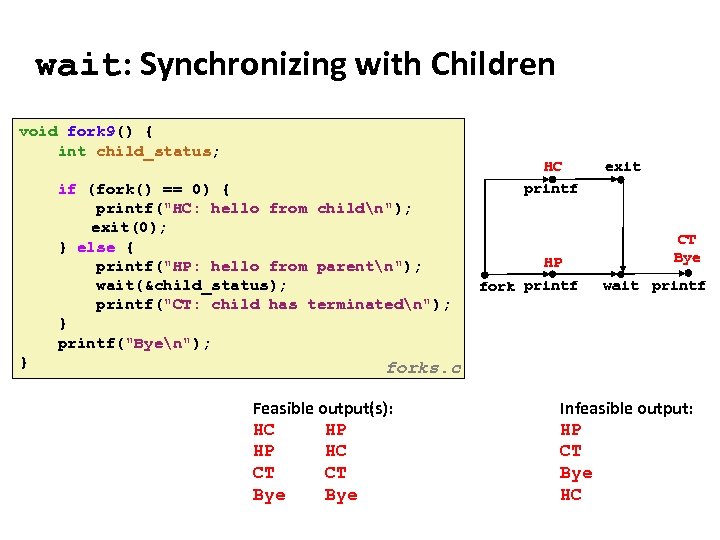

Carnegie Mellon wait: Synchronizing with Children void fork 9() { int child_status; if (fork() == 0) { printf("HC: hello from childn"); exit(0); } else { printf("HP: hello from parentn"); wait(&child_status); printf("CT: child has terminatedn"); } printf("Byen"); } forks. c Feasible output(s): Feasible output: HC HP HP HC CT CT Bye HC printf HP fork printf exit CT Bye wait printf Infeasible output: HP CT Bye HC

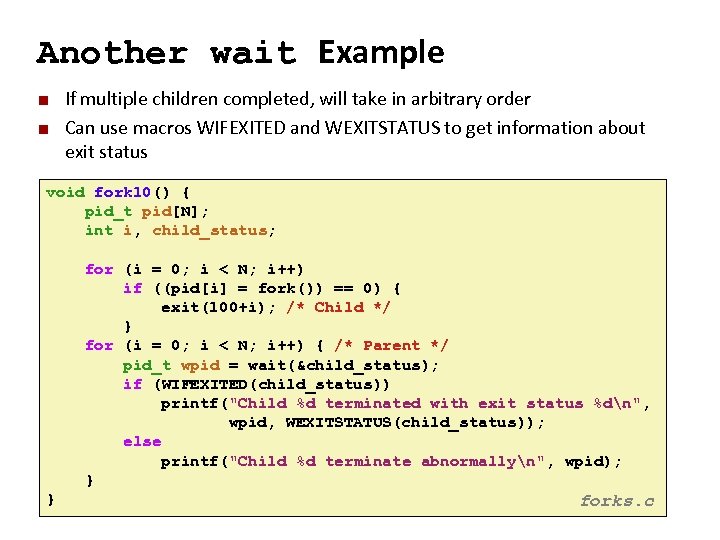

Carnegie Mellon Another wait Example ¢ ¢ If multiple children completed, will take in arbitrary order Can use macros WIFEXITED and WEXITSTATUS to get information about exit status void fork 10() { pid_t pid[N]; int i, child_status; for (i = 0; i < N; i++) if ((pid[i] = fork()) == 0) { exit(100+i); /* Child */ } for (i = 0; i < N; i++) { /* Parent */ pid_t wpid = wait(&child_status); if (WIFEXITED(child_status)) printf("Child %d terminated with exit status %dn", wpid, WEXITSTATUS(child_status)); else printf("Child %d terminate abnormallyn", wpid); } } forks. c

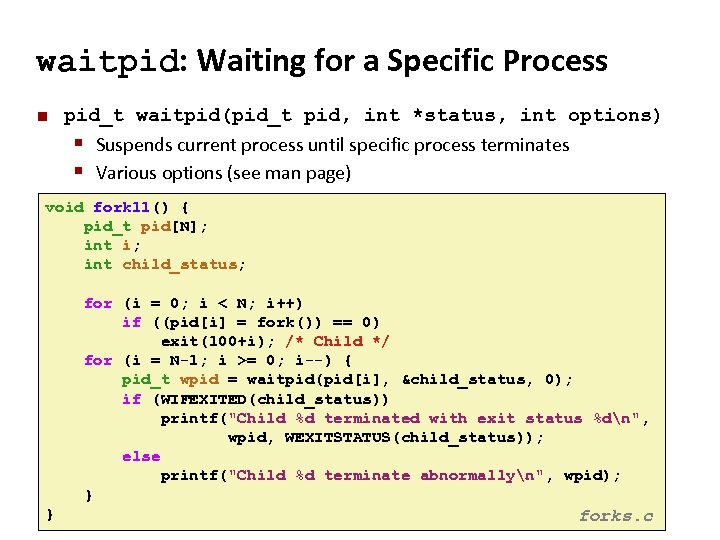

Carnegie Mellon waitpid: Waiting for a Specific Process ¢ pid_t waitpid(pid_t pid, int *status, int options) § Suspends current process until specific process terminates § Various options (see man page) void fork 11() { pid_t pid[N]; int i; int child_status; for (i = 0; i < N; i++) if ((pid[i] = fork()) == 0) exit(100+i); /* Child */ for (i = N-1; i >= 0; i--) { pid_t wpid = waitpid(pid[i], &child_status, 0); if (WIFEXITED(child_status)) printf("Child %d terminated with exit status %dn", wpid, WEXITSTATUS(child_status)); else printf("Child %d terminate abnormallyn", wpid); } } forks. c

![Carnegie Mellon execve: Loading and Running Programs ¢ int execve(char *filename, char *argv[], char Carnegie Mellon execve: Loading and Running Programs ¢ int execve(char *filename, char *argv[], char](https://present5.com/presentation/3e3ae83205112c3171a4998dfd30988b/image-42.jpg)

Carnegie Mellon execve: Loading and Running Programs ¢ int execve(char *filename, char *argv[], char *envp[]) ¢ Loads and runs in the current process: § Executable filename Can be object file or script file beginning with #!interpreter (e. g. , #!/bin/bash) § …with argument list argv § By convention argv[0]==filename § …and environment variable list envp § “name=value” strings (e. g. , USER=droh) § getenv, putenv, printenv § ¢ Overwrites code, data, and stack § Retains PID, open files and signal context ¢ Called once and never returns § …except if there is an error

Carnegie Mellon fork() and execve() ¢ execve() does not fork a new process! § Rather, it replaces the address space and CPU state of the current process § Loads the new address space from the executable file and starts it from main() § So, to start a new program, use fork() followed by execve()

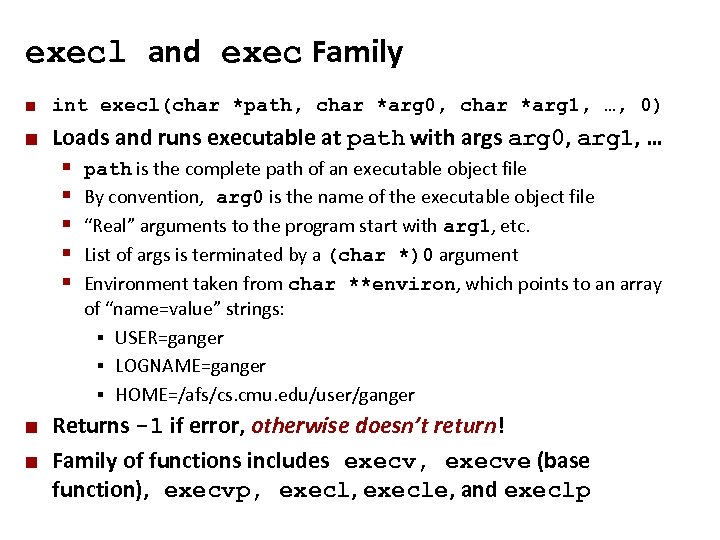

Carnegie Mellon execl and exec Family ¢ int execl(char *path, char *arg 0, char *arg 1, …, 0) ¢ Loads and runs executable at path with args arg 0, arg 1, … § § § ¢ ¢ path is the complete path of an executable object file By convention, arg 0 is the name of the executable object file “Real” arguments to the program start with arg 1, etc. List of args is terminated by a (char *)0 argument Environment taken from char **environ, which points to an array of “name=value” strings: § USER=ganger § LOGNAME=ganger § HOME=/afs/cs. cmu. edu/user/ganger Returns -1 if error, otherwise doesn’t return! Family of functions includes execv, execve (base function), execvp, execle, and execlp

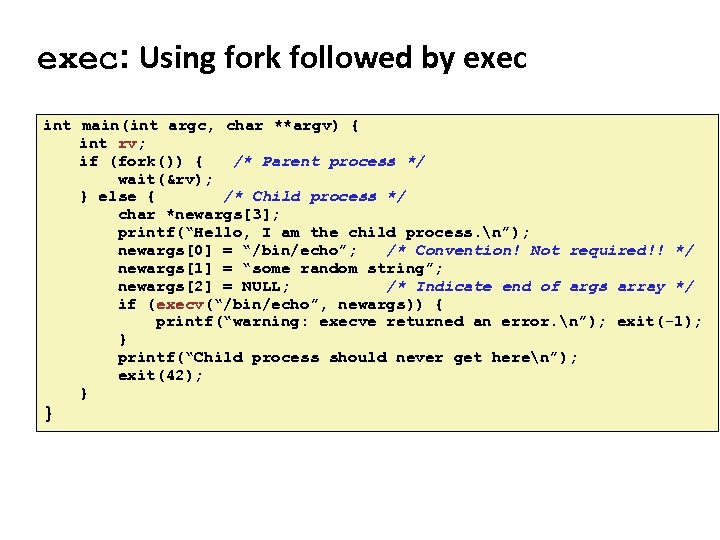

Carnegie Mellon exec: Using fork followed by exec int main(int argc, char **argv) { int rv; if (fork()) { /* Parent process */ wait(&rv); } else { /* Child process */ char *newargs[3]; printf(“Hello, I am the child process. n”); newargs[0] = “/bin/echo”; /* Convention! Not required!! */ newargs[1] = “some random string”; newargs[2] = NULL; /* Indicate end of args array */ if (execv(“/bin/echo”, newargs)) { printf(“warning: execve returned an error. n”); exit(-1); } printf(“Child process should never get heren”); exit(42); } }

![Carnegie Mellon Linux Process Hierarchy [0] init [1] … Login shell Child … Child Carnegie Mellon Linux Process Hierarchy [0] init [1] … Login shell Child … Child](https://present5.com/presentation/3e3ae83205112c3171a4998dfd30988b/image-46.jpg)

Carnegie Mellon Linux Process Hierarchy [0] init [1] … Login shell Child … Child Grandchild … Daemon e. g. httpd Login shell Child Grandchild Note: you can view the hierarchy using the Linux pstree command

Carnegie Mellon Summary ¢ Process § is an instance of program in execution § At any given time, a system has multiple active processes § Only one can execute at a time, though § Each process appears to have total control of processor + private memory space ¢ ¢ Spawning processes § Call to fork § One call, two returns Process completion § Call exit § One call, no return Reaping and waiting for Processes § Call wait or waitpid Loading and running Programs § Call execl (or variant) § One call, (normally) no return

Carnegie Mellon Inter-Process Communication: Intro + Pipes

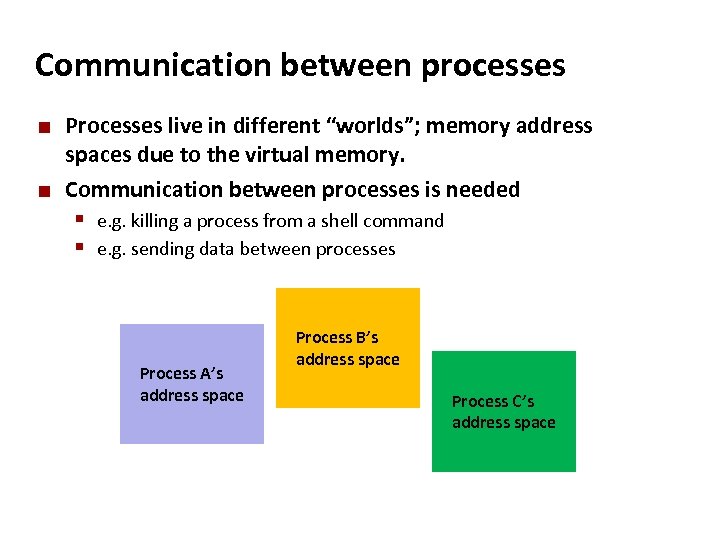

Carnegie Mellon Communication between processes ¢ ¢ Processes live in different “worlds”; memory address spaces due to the virtual memory. Communication between processes is needed § e. g. killing a process from a shell command § e. g. sending data between processes Process A’s address space Process B’s address space Process C’s address space

Carnegie Mellon Inter-process Communication (IPC) ¢ ¢ Cooperating processes or threads need inter-process communication (IPC) § Data transfer § Sharing data § Event notification § Resource sharing § Process control Processes may be running on one or more computers connected by a network. The method of IPC used may vary based on the bandwidth and latency of communication between the threads, and the type of data being communicated. IPC may also be referred to as inter-application communication.

Carnegie Mellon IPC mechanisms ¢ IPC mechanisms § Signals § Pipes Unnamed Pipes § Named Pipes of FIFOs Message Queues Shared Memory Mapped Files Semaphores (later) Remote processes, over network: § Remote Procedure Calls (RPC) § Sockets (in network course) § § §

Carnegie Mellon IPC – (Unnamed) Pipes ¢ ¢ A byte-stream among processes. Bytes written by a process is readable by another process in the other end. Applications: § in shell passing output of one program to another program § e. g. cat file 1 file 2 | sort ¢ Limitations: § § ¢ Processes need to be relatives (parent-child or siblings) cannot be used for broadcasting; Data in pipe is a byte stream – has no structure No way to distinguish between several readers or write Implementation: § Internal kernel buffers, socket buffers or STREAM interface.

Carnegie Mellon Pipes ¢ ¢ ¢ Created by a system call pipe(int *fd) Two file descriptors returned in pass by reference parameter. Bytes written on fd[1] by a process can be read on fd[0] by another, in the same order. Typical use: § § ¢ Pipe created by a process Process calls fork() File descriptors are inherited by child, so pipe is. Pipe used between parent and child A pipe provides a one-way flow of data § example: who | sort| lpr output of who is input to sort § output of sort is input to lpr §

Carnegie Mellon Pipes ¢ The difference between a file and a pipe: § pipe is a data structure in the kernel. Data is stored in kernel buffers temporarily. No random access (seek) on pipes. ¢ A pipe is created by using the pipe system call int pipe(int* filedes); filedes is an array of size 2 ¢ Two file descriptors are returned § filedes[0] is open for reading § filedes[1] is open for writing § Some systems implement bidirectional pipes, both ends are ¢ readable/writable. Typical buffer size is 512 bytes (Minimum limit defined by POSIX). Reads and writes may be blocked by the buffer.

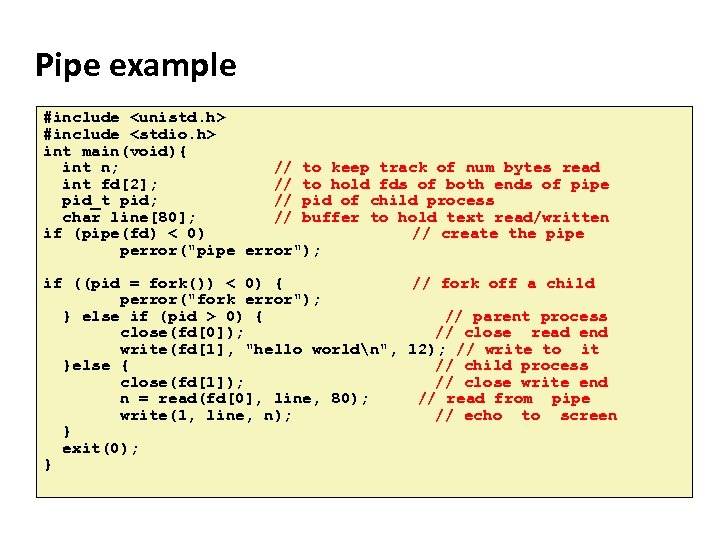

Carnegie Mellon Pipe example #include <unistd. h> #include <stdio. h> int main(void){ int n; // to keep track of num bytes read int fd[2]; // to hold fds of both ends of pipe pid_t pid; // pid of child process char line[80]; // buffer to hold text read/written if (pipe(fd) < 0) // create the pipe perror("pipe error"); if ((pid = fork()) < 0) { // fork off a child perror("fork error"); } else if (pid > 0) { // parent process close(fd[0]); // close read end write(fd[1], "hello worldn", 12); // write to it }else { // child process close(fd[1]); // close write end n = read(fd[0], line, 80); // read from pipe write(1, line, n); // echo to screen } exit(0); }

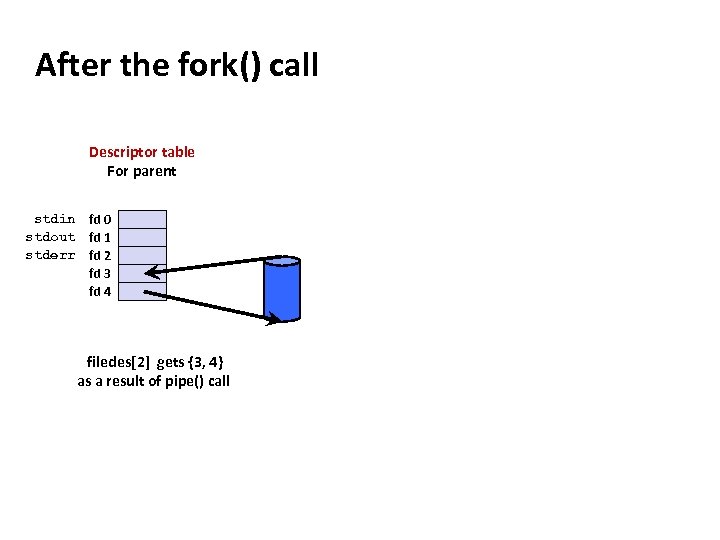

Carnegie Mellon After the fork() call Descriptor table For parent stdin fd 0 stdout fd 1 stderr fd 2 fd 3 fd 4 filedes[2] gets {3, 4} as a result of pipe() call

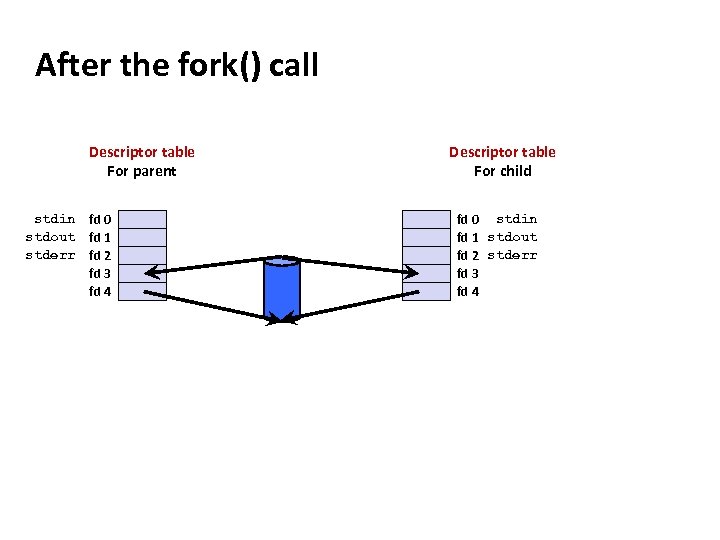

Carnegie Mellon After the fork() call Descriptor table For parent stdin fd 0 stdout fd 1 stderr fd 2 fd 3 fd 4 Descriptor table For child fd 0 stdin fd 1 stdout fd 2 stderr fd 3 fd 4

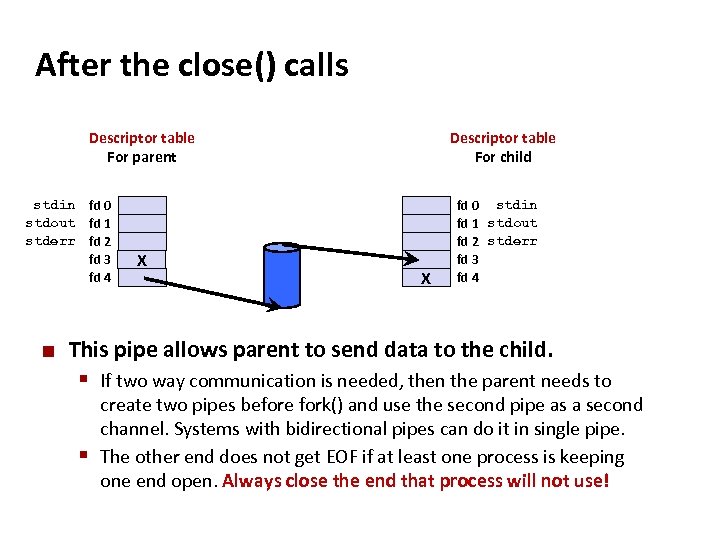

Carnegie Mellon After the close() calls Descriptor table For parent stdin fd 0 stdout fd 1 stderr fd 2 fd 3 fd 4 ¢ X Descriptor table For child X fd 0 stdin fd 1 stdout fd 2 stderr fd 3 fd 4 This pipe allows parent to send data to the child. § If two way communication is needed, then the parent needs to create two pipes before fork() and use the second pipe as a second channel. Systems with bidirectional pipes can do it in single pipe. § The other end does not get EOF if at least one process is keeping one end open. Always close the end that process will not use!

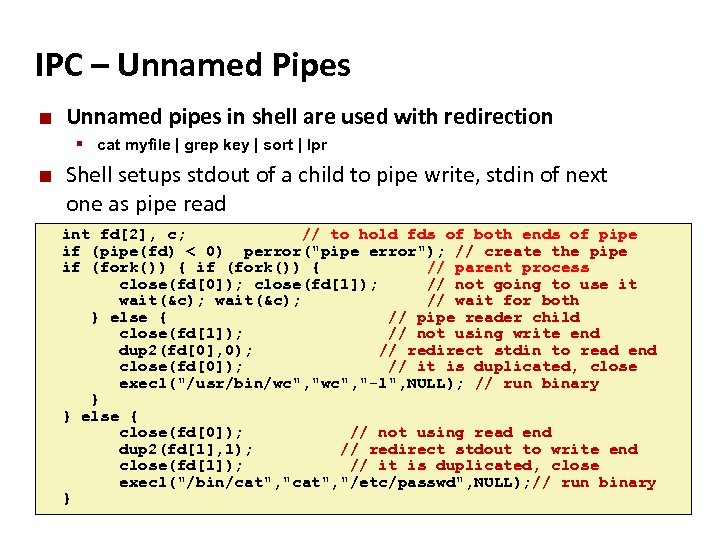

Carnegie Mellon IPC – Unnamed Pipes ¢ Unnamed pipes in shell are used with redirection § cat myfile | grep key | sort | lpr ¢ Shell setups stdout of a child to pipe write, stdin of next one as pipe read int fd[2], c; // to hold fds of both ends of pipe if (pipe(fd) < 0) perror("pipe error"); // create the pipe if (fork()) { // parent process close(fd[0]); close(fd[1]); // not going to use it wait(&c); // wait for both } else { // pipe reader child close(fd[1]); // not using write end dup 2(fd[0], 0); // redirect stdin to read end close(fd[0]); // it is duplicated, close execl("/usr/bin/wc", "-l", NULL); // run binary } } else { close(fd[0]); // not using read end dup 2(fd[1], 1); // redirect stdout to write end close(fd[1]); // it is duplicated, close execl("/bin/cat", "/etc/passwd", NULL); // run binary }

Carnegie Mellon IPC - Named Pipes or FIFOs ¢ ¢ ¢ ¢ Pipes are restricted to processes of same family (parent/child, siblings). Relies on file descriptor inheritance. FIFOs are pipes named as a path on the file system. They can be accessed by any process that “knows the name” Pipes are temporary. They disappear when last process closes. FIFOs or named pipes, are special files that persist even after all processes have closed them A FIFO has a name and permissions just like an ordinary file and appears in a directory listing Any process with the appropriate permissions can access a FIFO A user creates a FIFO by executing the mkfifo command from a command shell or by calling the mkfifo() system call within a program

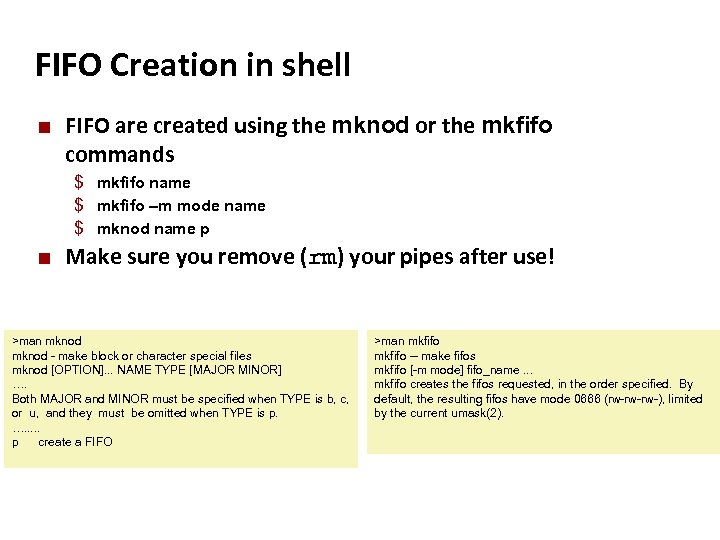

Carnegie Mellon FIFO Creation in shell ¢ FIFO are created using the mknod or the mkfifo commands $ mkfifo name $ mkfifo –m mode name $ mknod name p ¢ Make sure you remove (rm) your pipes after use! >man mknod - make block or character special files mknod [OPTION]. . . NAME TYPE [MAJOR MINOR] …. Both MAJOR and MINOR must be specified when TYPE is b, c, or u, and they must be omitted when TYPE is p. …. . . p create a FIFO >man mkfifo -- make fifos mkfifo [-m mode] fifo_name. . . mkfifo creates the fifos requested, in the order specified. By default, the resulting fifos have mode 0666 (rw-rw-rw-), limited by the current umask(2).

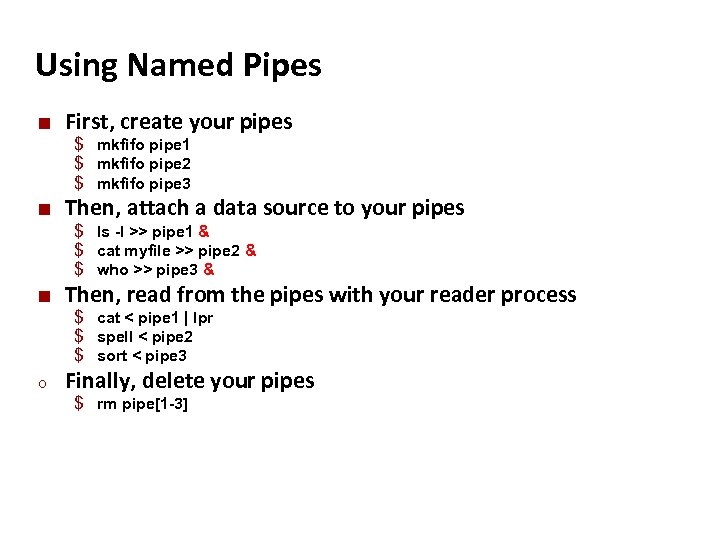

Carnegie Mellon Using Named Pipes ¢ First, create your pipes $ mkfifo pipe 1 $ mkfifo pipe 2 $ mkfifo pipe 3 ¢ Then, attach a data source to your pipes $ ls -l >> pipe 1 & $ cat myfile >> pipe 2 & $ who >> pipe 3 & ¢ Then, read from the pipes with your reader process $ cat < pipe 1 | lpr $ spell < pipe 2 $ sort < pipe 3 o Finally, delete your pipes $ rm pipe[1 -3]

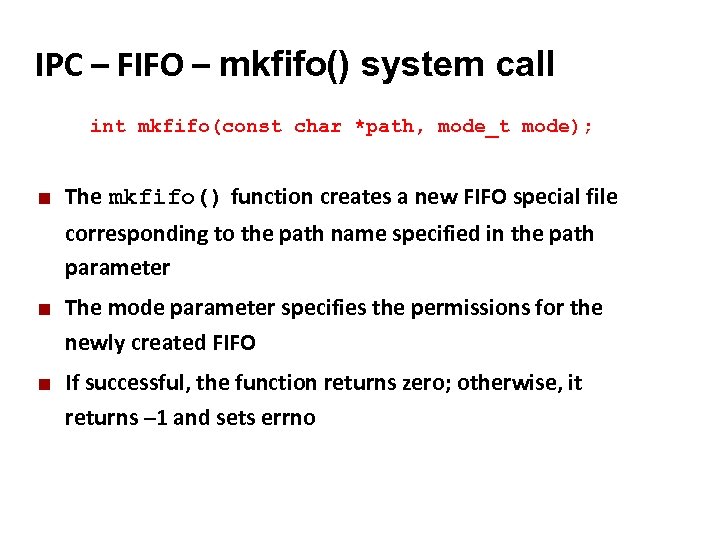

Carnegie Mellon IPC – FIFO – mkfifo() system call int mkfifo(const char *path, mode_t mode); ¢ The mkfifo() function creates a new FIFO special file corresponding to the path name specified in the path parameter ¢ ¢ The mode parameter specifies the permissions for the newly created FIFO If successful, the function returns zero; otherwise, it returns – 1 and sets errno

Carnegie Mellon Inter-Process Communication: Signals Slides adapted from: Randy Bryant of Carnegie Mellon University

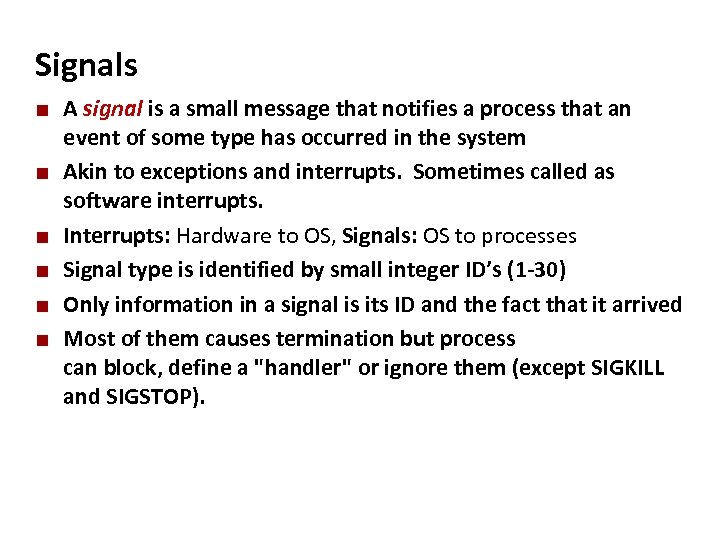

Carnegie Mellon Signals ¢ ¢ ¢ A signal is a small message that notifies a process that an event of some type has occurred in the system Akin to exceptions and interrupts. Sometimes called as software interrupts. Interrupts: Hardware to OS, Signals: OS to processes Signal type is identified by small integer ID’s (1 -30) Only information in a signal is its ID and the fact that it arrived Most of them causes termination but process can block, define a "handler" or ignore them (except SIGKILL and SIGSTOP).

Carnegie Mellon Signals ID Name Default Action Corresponding Event 1 SIGHUP Terminate Terminal line close 2 SIGINT Terminate User typed ctrl-c 3 SIGQUIT Terminate Ctrl+ 4 SIGILL Terminate Illegal instruction on CPU 8 SIGFPE Terminate Floating point exception 9 SIGKILL Terminate 11 SIGSEGV Terminate Segmentation violation 13 SIGPIPE Terminate Write on a closed pipe 14 SIGALRM Terminate User timer 15 SIGTERM Terminate process (can be overwritten) 17 SIGCHLD Ignore Child stopped or terminated 19 SIGSTOP Suspend process execution 18 SIGCONT Continue suspended proces 10 SIGUSR 1 12 SIGUSR 2 Ignore User defined Thumbnail. Kill program (cannot override or ignore)

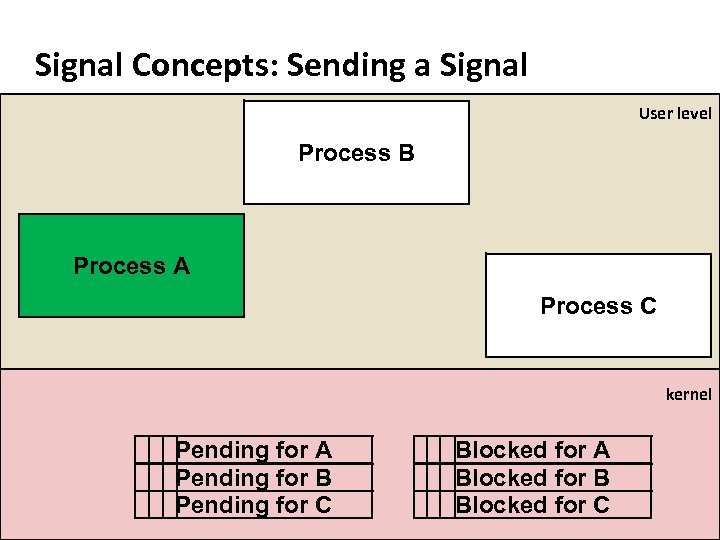

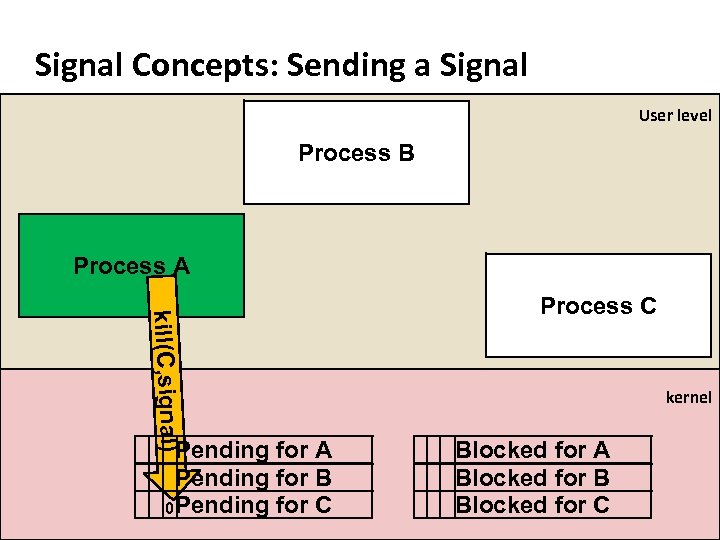

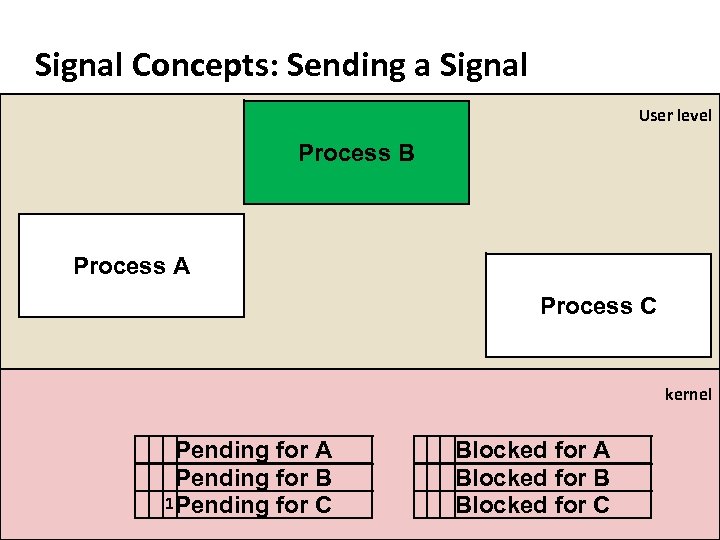

Carnegie Mellon Signal Concepts: Sending a Signal ¢ ¢ Kernel sends (delivers) a signal to a destination process by updating some state in the context of the destination process Signals can be initiated by: § Hardware event, interrupt: SIGFPE, SIGSEGV, SIGILL. § OS event: SIGPIPE, SIGHUP, SIGCHLD, SIGALRM, User input § Process request: kill() system call ¢ ¢ PCB stores signal delivery status and setup for a process. Each is a bitmap, a bit per signal: § Pending: Signal is sent to the process, waiting to be delivered § Block: Delivery of signal is to be blocked by the process

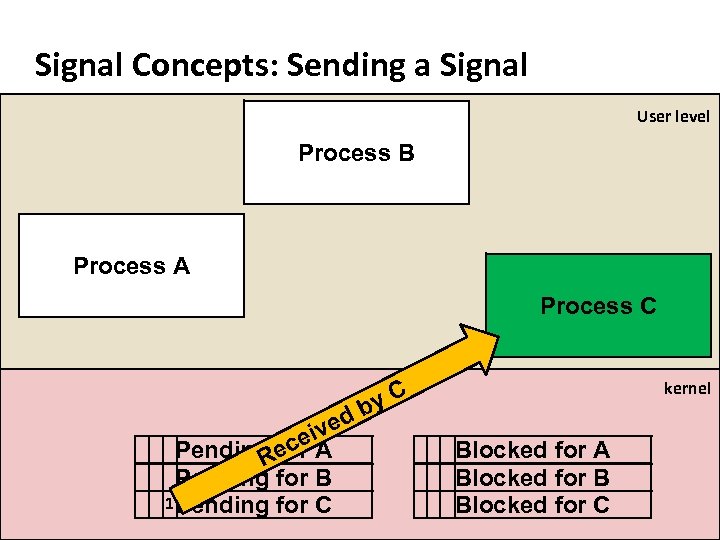

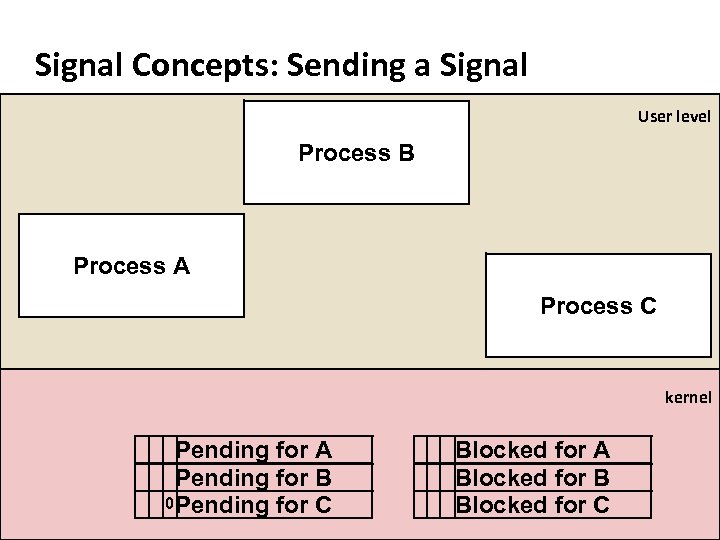

Carnegie Mellon Signal Concepts: Sending a Signal User level Process B Process A Process C kernel Pending for A Pending for B Pending for C Blocked for A Blocked for B Blocked for C

Carnegie Mellon Signal Concepts: Sending a Signal User level Process B Process A kill(C, signal) Pending for A Pending for B 0 Pending for C Process C kernel Blocked for A Blocked for B Blocked for C

Carnegie Mellon Signal Concepts: Sending a Signal User level Process B Process A Process C kernel Pending for A Pending for B 1 Pending for C Blocked for A Blocked for B Blocked for C

Carnegie Mellon Signal Concepts: Sending a Signal User level Process B Process A Process C kernel db ve ei. A c Pending for Re Pending for B 1 Pending for C y. C Blocked for A Blocked for B Blocked for C

Carnegie Mellon Signal Concepts: Sending a Signal User level Process B Process A Process C kernel Pending for A Pending for B 0 Pending for C Blocked for A Blocked for B Blocked for C

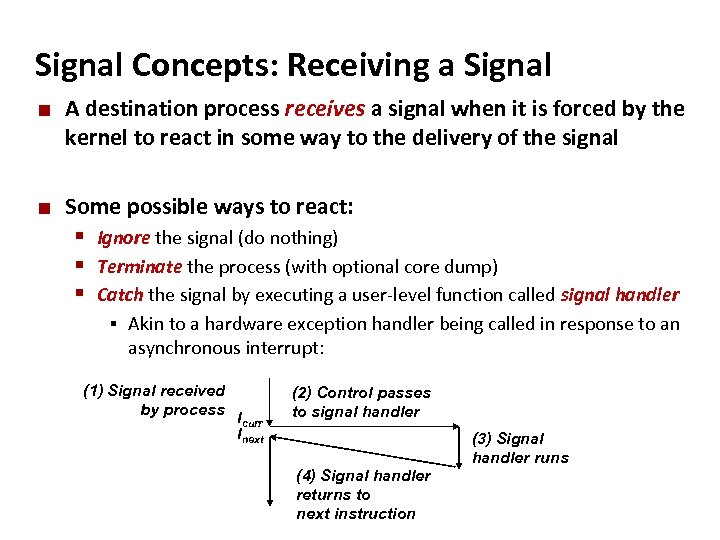

Carnegie Mellon Signal Concepts: Receiving a Signal ¢ ¢ A destination process receives a signal when it is forced by the kernel to react in some way to the delivery of the signal Some possible ways to react: § Ignore the signal (do nothing) § Terminate the process (with optional core dump) § Catch the signal by executing a user-level function called signal handler § Akin to a hardware exception handler being called in response to an asynchronous interrupt: (1) Signal received by process Icurr Inext (2) Control passes to signal handler (4) Signal handler returns to next instruction (3) Signal handler runs

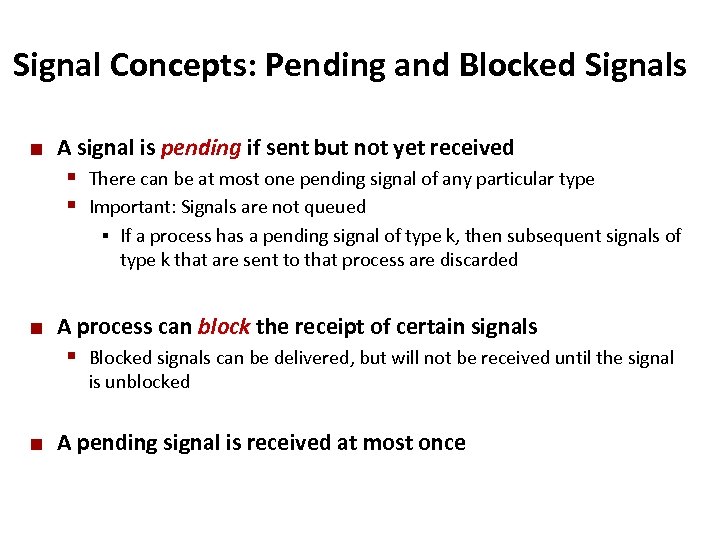

Carnegie Mellon Signal Concepts: Pending and Blocked Signals ¢ A signal is pending if sent but not yet received § There can be at most one pending signal of any particular type § Important: Signals are not queued § ¢ If a process has a pending signal of type k, then subsequent signals of type k that are sent to that process are discarded A process can block the receipt of certain signals § Blocked signals can be delivered, but will not be received until the signal is unblocked ¢ A pending signal is received at most once

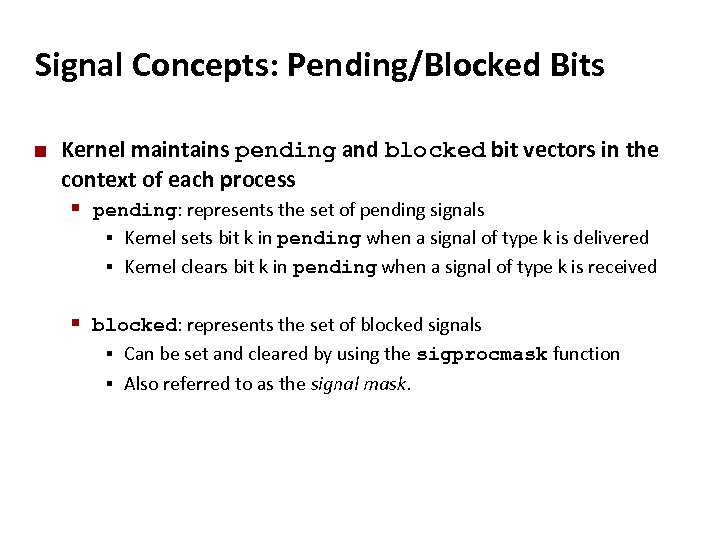

Carnegie Mellon Signal Concepts: Pending/Blocked Bits ¢ Kernel maintains pending and blocked bit vectors in the context of each process § pending: represents the set of pending signals Kernel sets bit k in pending when a signal of type k is delivered § Kernel clears bit k in pending when a signal of type k is received § § blocked: represents the set of blocked signals Can be set and cleared by using the sigprocmask function § Also referred to as the signal mask. §

![Carnegie Mellon Sending Signals with kill Function void fork 12() { pid_t pid[N]; int Carnegie Mellon Sending Signals with kill Function void fork 12() { pid_t pid[N]; int](https://present5.com/presentation/3e3ae83205112c3171a4998dfd30988b/image-76.jpg)

Carnegie Mellon Sending Signals with kill Function void fork 12() { pid_t pid[N]; int i; int child_status; for (i = 0; i < N; i++) if ((pid[i] = fork()) == 0) { /* Child: Infinite Loop */ while(1) ; } for (i = 0; i < N; i++) { printf("Killing process %dn", pid[i]); kill(pid[i], SIGINT); } for (i = 0; i < N; i++) { pid_t wpid = wait(&child_status); if (WIFEXITED(child_status)) printf("Child %d terminated with exit status %dn", wpid, WEXITSTATUS(child_status)); else printf("Child %d terminated abnormallyn", wpid); } } forks. c

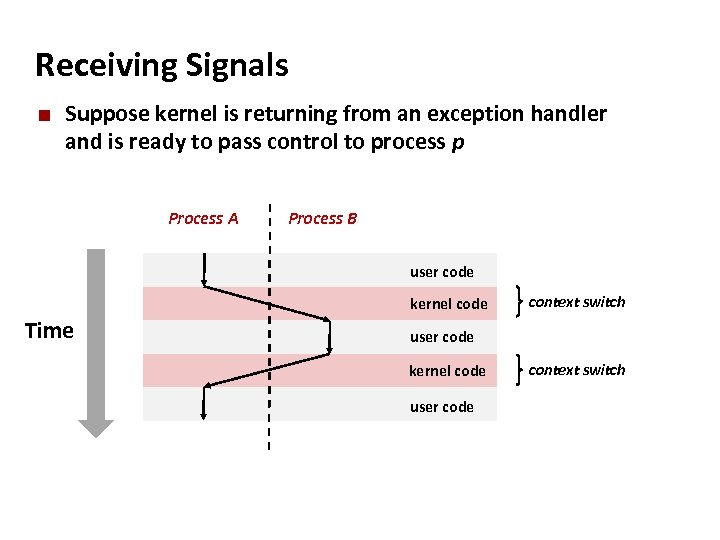

Carnegie Mellon Receiving Signals ¢ Suppose kernel is returning from an exception handler and is ready to pass control to process p Process A Process B user code kernel code Time context switch user code kernel code user code context switch

Carnegie Mellon Receiving Signals ¢ ¢ Suppose kernel is returning from an exception handler and is ready to pass control to process p Kernel computes pnb = pending & ~blocked § The set of pending nonblocked signals for process p ¢ If (pnb == 0) § Pass control to next instruction in the logical flow for p ¢ Else § Choose least nonzero bit k in pnb and force process p to receive signal k § The receipt of the signal triggers some action by p § Repeat for all nonzero k in pnb § Pass control to next instruction in logical flow for p

Carnegie Mellon Default Actions ¢ Each signal type has a predefined default action, which is one of: § The process terminates § The process stops until restarted by a SIGCONT signal § The process ignores the signal

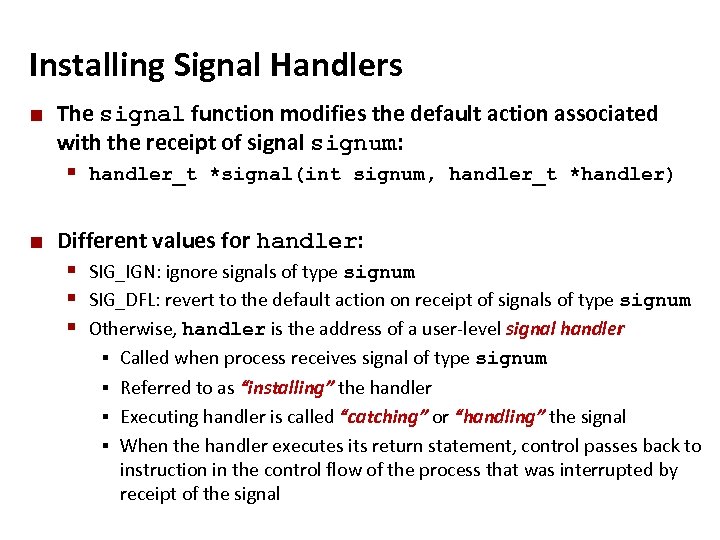

Carnegie Mellon Installing Signal Handlers ¢ The signal function modifies the default action associated with the receipt of signal signum: § handler_t *signal(int signum, handler_t *handler) ¢ Different values for handler: § SIG_IGN: ignore signals of type signum § SIG_DFL: revert to the default action on receipt of signals of type signum § Otherwise, handler is the address of a user-level signal handler Called when process receives signal of type signum § Referred to as “installing” the handler § Executing handler is called “catching” or “handling” the signal § When the handler executes its return statement, control passes back to instruction in the control flow of the process that was interrupted by receipt of the signal §

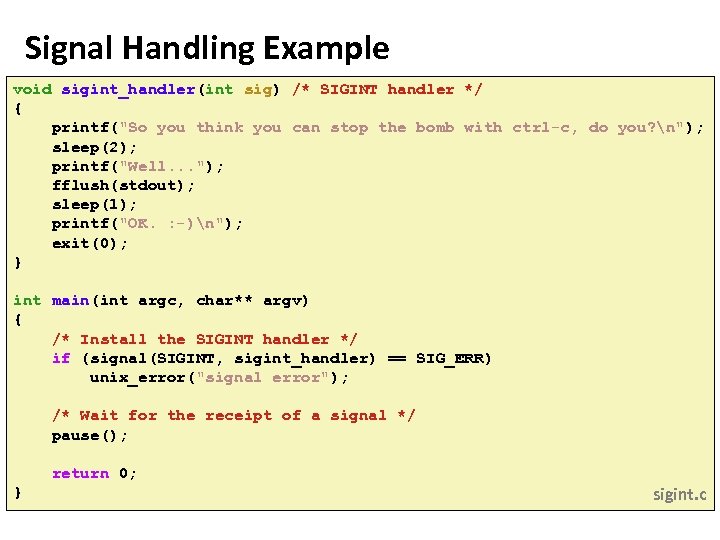

Carnegie Mellon Signal Handling Example void sigint_handler(int sig) /* SIGINT handler */ { printf("So you think you can stop the bomb with ctrl-c, do you? n"); sleep(2); printf("Well. . . "); fflush(stdout); sleep(1); printf("OK. : -)n"); exit(0); } int main(int argc, char** argv) { /* Install the SIGINT handler */ if (signal(SIGINT, sigint_handler) == SIG_ERR) unix_error("signal error"); /* Wait for the receipt of a signal */ pause(); return 0; } sigint. c

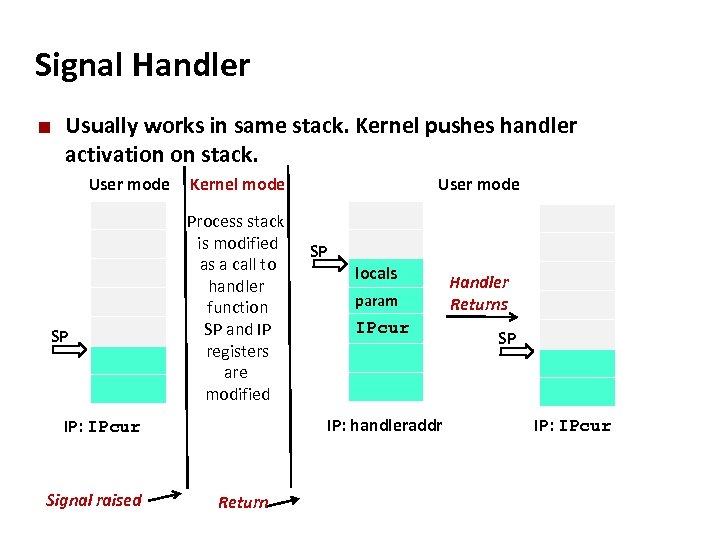

Carnegie Mellon Signal Handler ¢ Usually works in same stack. Kernel pushes handler activation on stack. User mode SP Kernel mode Process stack is modified as a call to handler function SP and IP registers are modified SP locals param IPcur IP: handleraddr IP: IPcur Signal raised User mode Return Handler Returns SP IP: IPcur

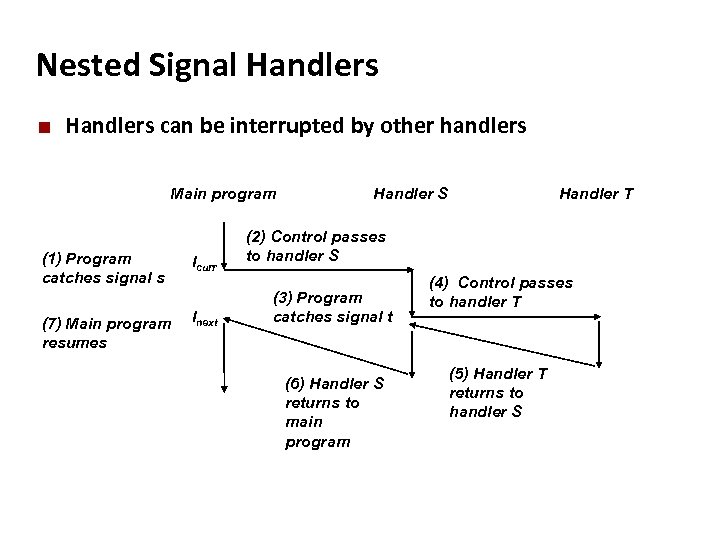

Carnegie Mellon Nested Signal Handlers ¢ Handlers can be interrupted by other handlers Main program (1) Program catches signal s (7) Main program resumes Icurr Inext Handler S Handler T (2) Control passes to handler S (3) Program catches signal t (6) Handler S returns to main program (4) Control passes to handler T (5) Handler T returns to handler S

Carnegie Mellon Blocking and Unblocking Signals ¢ Implicit blocking mechanism § Kernel blocks any pending signals of type currently being handled. § E. g. , A SIGINT handler can’t be interrupted by another SIGINT ¢ Explicit blocking and unblocking mechanism § sigprocmask function ¢ Supporting functions § § sigemptyset – Create empty set sigfillset – Add every signal number to set sigaddset – Add signal number to set sigdelset – Delete signal number from set

Carnegie Mellon Safe Signal Handling ¢ Handlers are tricky because they are concurrent with main program and share the same global data structures. § Shared data structures can become corrupted. ¢ Pending signals are not queued § For each signal type, one bit indicates whether or not signal is pending… § …thus at most one pending signal of any particular type. § You can’t use signals to count events, such as children terminating. ¢ Waiting for Signals § int sigsuspend(const sigset_t *mask)

Carnegie Mellon Inter-Process Communication: Shared memory

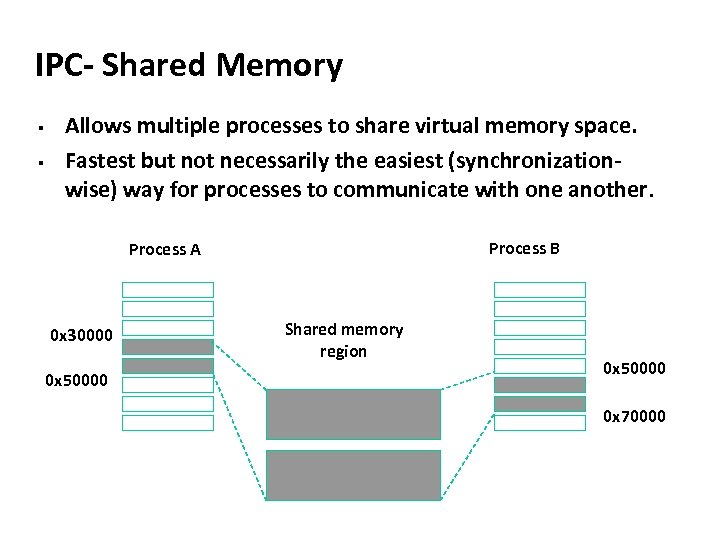

Carnegie Mellon IPC- Shared Memory § § Allows multiple processes to share virtual memory space. Fastest but not necessarily the easiest (synchronizationwise) way for processes to communicate with one another. Process B Process A 0 x 30000 0 x 50000 Shared memory region 0 x 50000 0 x 70000

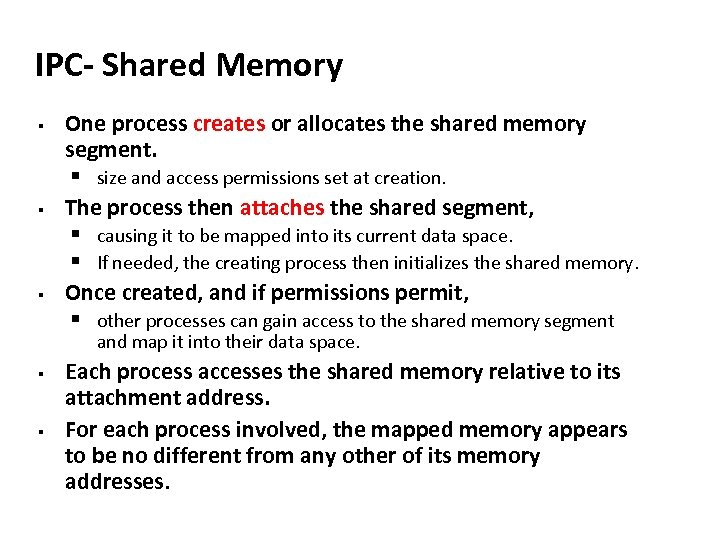

Carnegie Mellon IPC- Shared Memory § One process creates or allocates the shared memory segment. § size and access permissions set at creation. § The process then attaches the shared segment, § causing it to be mapped into its current data space. § If needed, the creating process then initializes the shared memory. § Once created, and if permissions permit, § other processes can gain access to the shared memory segment and map it into their data space. § § Each process accesses the shared memory relative to its attachment address. For each process involved, the mapped memory appears to be no different from any other of its memory addresses.

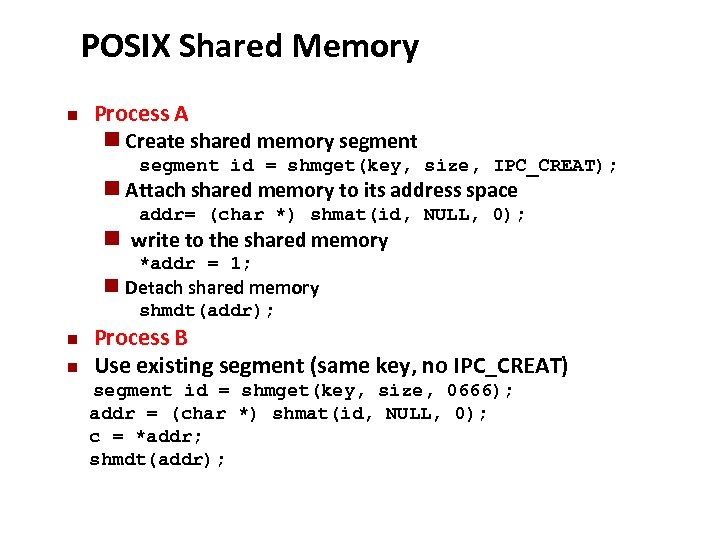

Carnegie Mellon POSIX Shared Memory n Process A n Create shared memory segment id = shmget(key, size, IPC_CREAT); n Attach shared memory to its address space addr= (char *) shmat(id, NULL, 0); n write to the shared memory *addr = 1; n Detach shared memory shmdt(addr); n n Process B Use existing segment (same key, no IPC_CREAT) segment id = shmget(key, size, 0666); addr = (char *) shmat(id, NULL, 0); c = *addr; shmdt(addr);

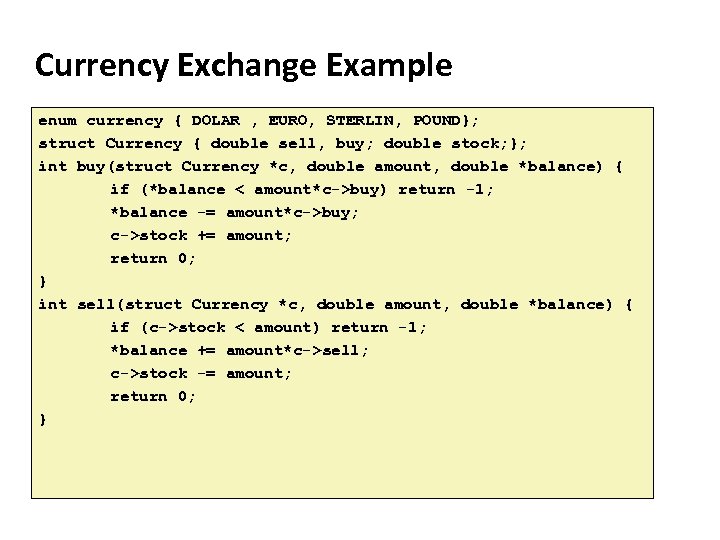

Carnegie Mellon Currency Exchange Example enum currency { DOLAR , EURO, STERLIN, POUND}; struct Currency { double sell, buy; double stock; }; int buy(struct Currency *c, double amount, double *balance) { if (*balance < amount*c->buy) return -1; *balance -= amount*c->buy; c->stock += amount; return 0; } int sell(struct Currency *c, double amount, double *balance) { if (c->stock < amount) return -1; *balance += amount*c->sell; c->stock -= amount; return 0; }

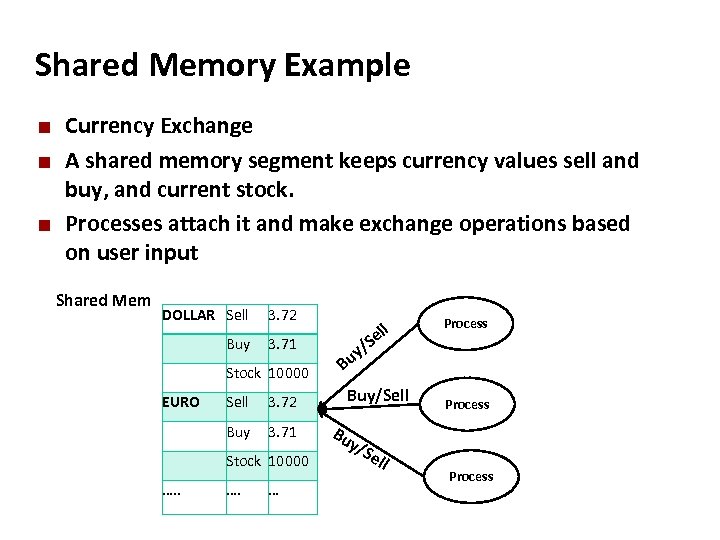

Carnegie Mellon Shared Memory Example ¢ ¢ ¢ Currency Exchange A shared memory segment keeps currency values sell and buy, and current stock. Processes attach it and make exchange operations based on user input Shared Mem DOLLAR Sell 3. 72 Buy 3. 71 ll Se y/ Stock 10000 Bu Sell 3. 72 Buy/Sell Buy EURO 3. 71 Stock 10000 …. . Process …. … Process Bu y/S e ll Process

![Carnegie Mellon #include "exchange. h” struct Currency init[4] ={ {3. 73, 3. 72, 10000}, Carnegie Mellon #include "exchange. h” struct Currency init[4] ={ {3. 73, 3. 72, 10000},](https://present5.com/presentation/3e3ae83205112c3171a4998dfd30988b/image-92.jpg)

Carnegie Mellon #include "exchange. h” struct Currency init[4] ={ {3. 73, 3. 72, 10000}, {3. 932, 3. 944, 10000}, {4. 551, 4. 552, 10000}, {3. 24, 3. 25, 5000}}; struct Currency *curshared; int main() { int key, i; // create a shared memory for 4 Currency structures key = shmget(EXCHKEY, sizeof(struct Currency)*4, IPC_CREAT|0600); if (key < 0) { perror("shmget") ; return 1; } // attach it and get result in curshared pointer curshared = (struct Currency *) shmat( key, NULL, 0); for (i = 0; i < 4; i++) curshared[i] = init[i]; shmdt((void *) curshared); return 0; }

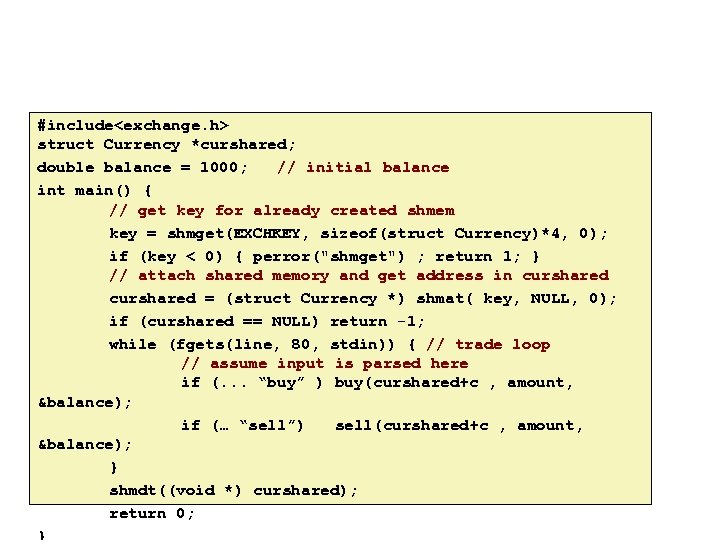

Carnegie Mellon #include<exchange. h> struct Currency *curshared; double balance = 1000; // initial balance int main() { // get key for already created shmem key = shmget(EXCHKEY, sizeof(struct Currency)*4, 0); if (key < 0) { perror("shmget") ; return 1; } // attach shared memory and get address in curshared = (struct Currency *) shmat( key, NULL, 0); if (curshared == NULL) return -1; while (fgets(line, 80, stdin)) { // trade loop // assume input is parsed here if (. . . “buy” ) buy(curshared+c , amount, &balance); if (… “sell”) sell(curshared+c , amount, &balance); } shmdt((void *) curshared); return 0;

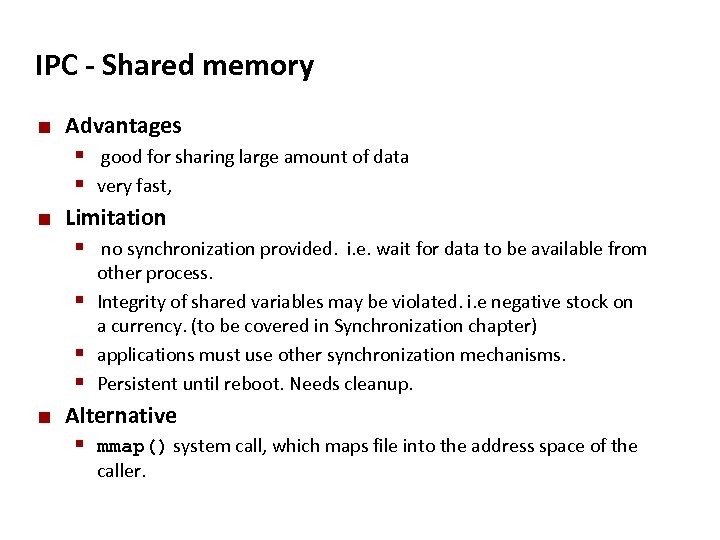

Carnegie Mellon IPC - Shared memory ¢ Advantages § good for sharing large amount of data § very fast, ¢ Limitation § no synchronization provided. i. e. wait for data to be available from other process. § Integrity of shared variables may be violated. i. e negative stock on a currency. (to be covered in Synchronization chapter) § applications must use other synchronization mechanisms. § Persistent until reboot. Needs cleanup. ¢ Alternative § mmap() system call, which maps file into the address space of the caller.

Carnegie Mellon Exceptional Control Flow Slides adapted from: Gregory Kesden and Markus Püschel of Carnegie Mellon University

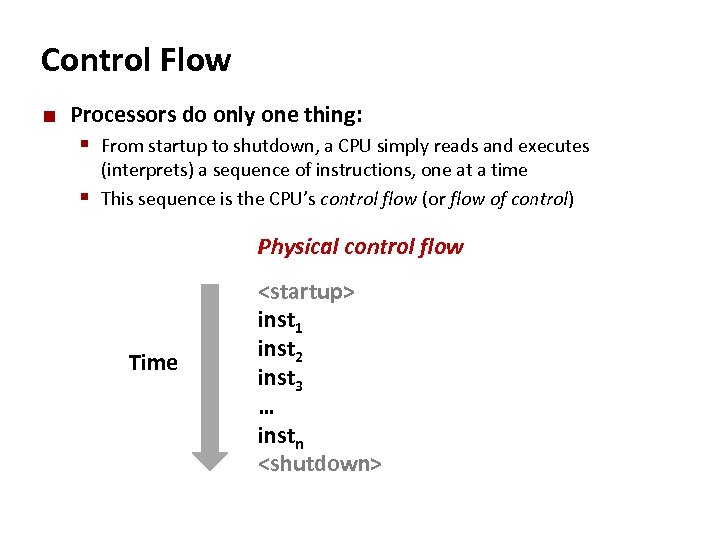

Carnegie Mellon Control Flow ¢ Processors do only one thing: § From startup to shutdown, a CPU simply reads and executes (interprets) a sequence of instructions, one at a time § This sequence is the CPU’s control flow (or flow of control) Physical control flow Time <startup> inst 1 inst 2 inst 3 … instn <shutdown>

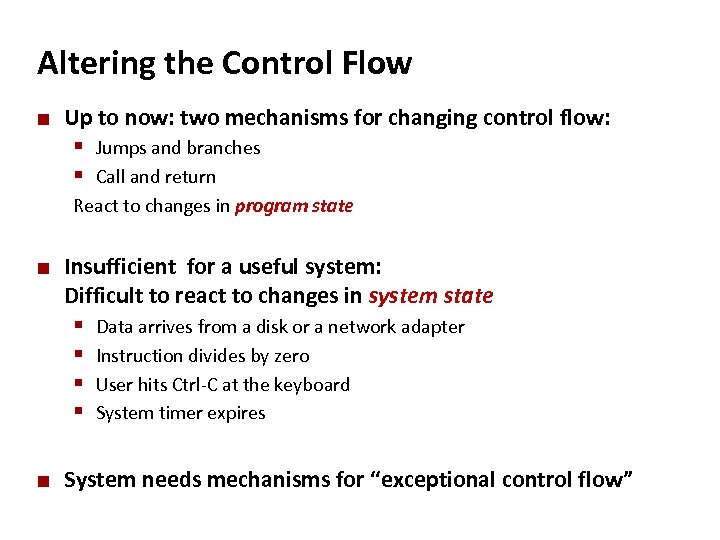

Carnegie Mellon Altering the Control Flow ¢ Up to now: two mechanisms for changing control flow: § Jumps and branches § Call and return React to changes in program state ¢ Insufficient for a useful system: Difficult to react to changes in system state § § ¢ Data arrives from a disk or a network adapter Instruction divides by zero User hits Ctrl-C at the keyboard System timer expires System needs mechanisms for “exceptional control flow”

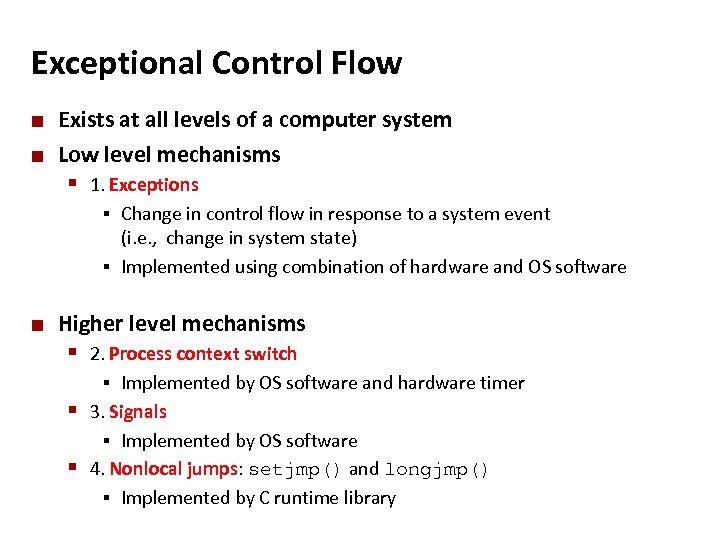

Carnegie Mellon Exceptional Control Flow ¢ ¢ Exists at all levels of a computer system Low level mechanisms § 1. Exceptions Change in control flow in response to a system event (i. e. , change in system state) § Implemented using combination of hardware and OS software § ¢ Higher level mechanisms § 2. Process context switch Implemented by OS software and hardware timer § 3. Signals § Implemented by OS software § 4. Nonlocal jumps: setjmp() and longjmp() § Implemented by C runtime library §

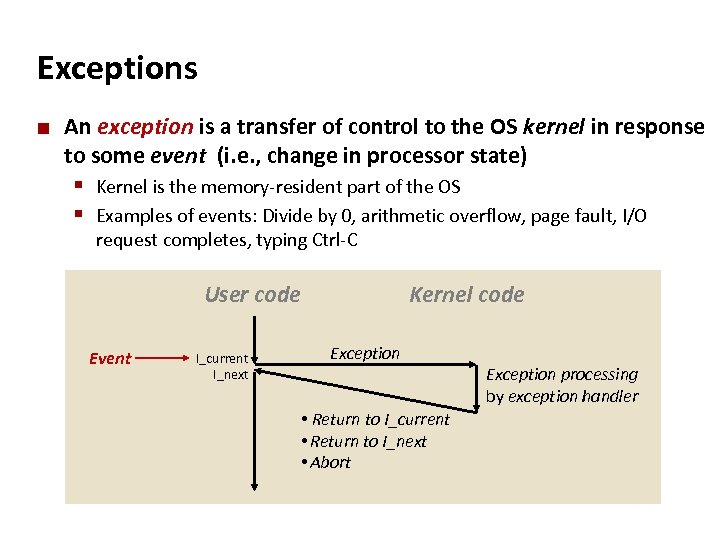

Carnegie Mellon Exceptions ¢ An exception is a transfer of control to the OS kernel in response to some event (i. e. , change in processor state) § Kernel is the memory-resident part of the OS § Examples of events: Divide by 0, arithmetic overflow, page fault, I/O request completes, typing Ctrl-C User code Event I_current I_next Kernel code Exception • Return to I_current • Return to I_next • Abort Exception processing by exception handler

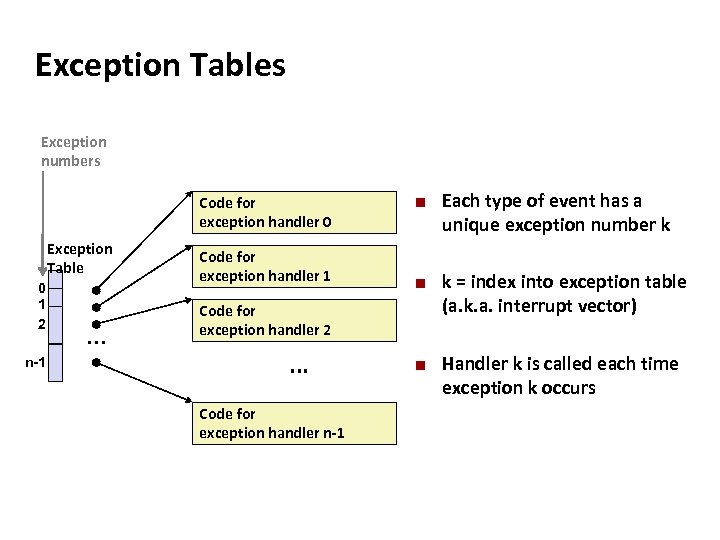

Carnegie Mellon Exception Tables Exception numbers Code for exception handler 0 Exception Table 0 1 2 n-1 . . . Code for exception handler 1 ¢ ¢ Code for exception handler 2 . . . Code for exception handler n-1 ¢ Each type of event has a unique exception number k k = index into exception table (a. k. a. interrupt vector) Handler k is called each time exception k occurs

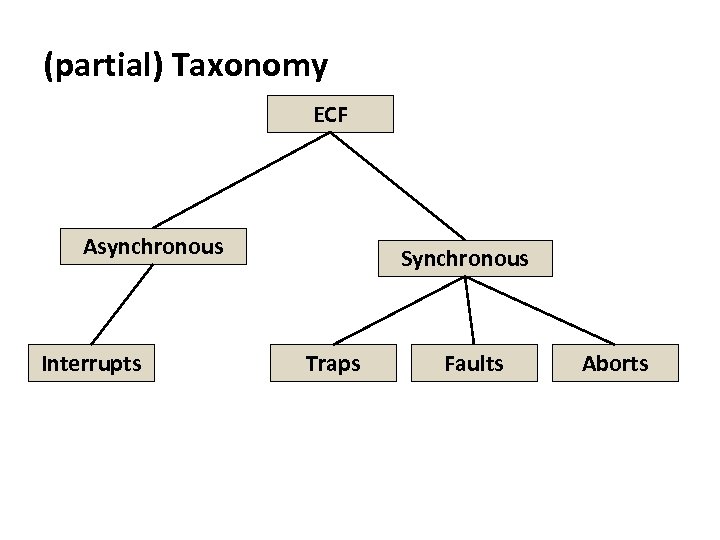

Carnegie Mellon (partial) Taxonomy ECF Asynchronous Interrupts Synchronous Traps Faults Aborts

Carnegie Mellon Asynchronous Exceptions (Interrupts) ¢ Caused by events external to the processor § Indicated by setting the processor’s interrupt pin § Handler returns to “next” instruction ¢ Examples: § Timer interrupt Every few ms, an external timer chip triggers an interrupt § Used by the kernel to take back control from user programs § I/O interrupt from external device § Hitting Ctrl-C at the keyboard § Arrival of a packet from a network § Arrival of data from a disk §

Carnegie Mellon Synchronous Exceptions ¢ Caused by events that occur as a result of executing an instruction: § Traps Intentional § Examples: system calls, breakpoint traps, special instructions § Returns control to “next” instruction § Faults § Unintentional but possibly recoverable § Examples: page faults (recoverable), protection faults (unrecoverable), floating point exceptions § Either re-executes faulting (“current”) instruction or aborts § Aborts § Unintentional and unrecoverable § Examples: illegal instruction, parity error, machine check § Aborts current program §

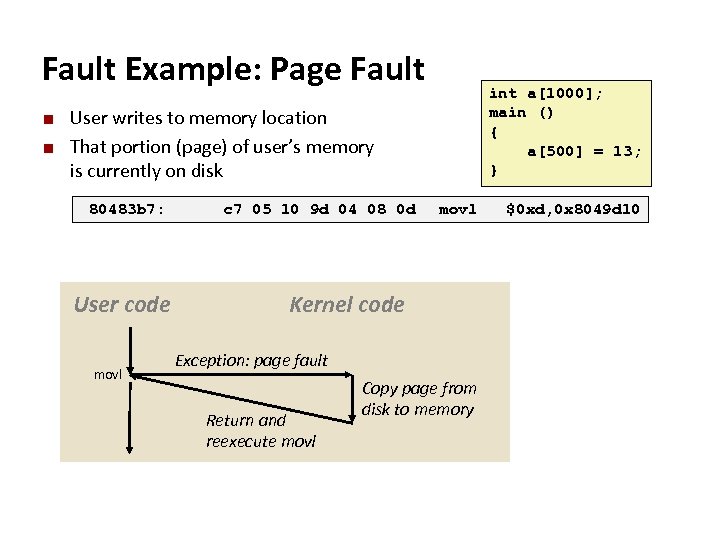

Carnegie Mellon Fault Example: Page Fault ¢ ¢ User writes to memory location That portion (page) of user’s memory is currently on disk 80483 b 7: User code movl int a[1000]; main () { a[500] = 13; } c 7 05 10 9 d 04 08 0 d movl $0 xd, 0 x 8049 d 10 Kernel code Exception: page fault Return and reexecute movl Copy page from disk to memory

![Carnegie Mellon Fault Example: Invalid Memory Reference int a[1000]; main () { a[5000] = Carnegie Mellon Fault Example: Invalid Memory Reference int a[1000]; main () { a[5000] =](https://present5.com/presentation/3e3ae83205112c3171a4998dfd30988b/image-105.jpg)

Carnegie Mellon Fault Example: Invalid Memory Reference int a[1000]; main () { a[5000] = 13; } 80483 b 7: c 7 05 60 e 3 04 08 0 d movl $0 xd, 0 x 804 e 360 User code movl Kernel code Exception: page fault Detect invalid address Signal process ¢ ¢ Sends SIGSEGV signal to user process User process exits with “segmentation fault”

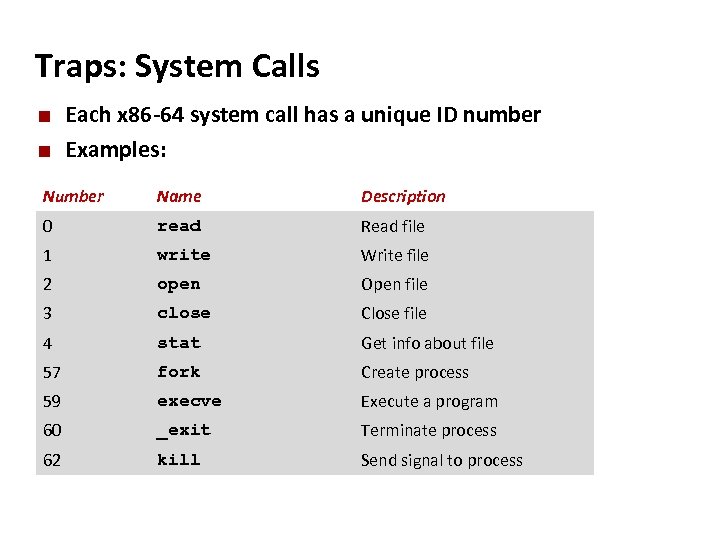

Carnegie Mellon Traps: System Calls ¢ ¢ Each x 86 -64 system call has a unique ID number Examples: Number Name Description 0 read Read file 1 write Write file 2 open Open file 3 close Close file 4 stat Get info about file 57 fork Create process 59 execve Execute a program 60 _exit Terminate process 62 kill Send signal to process

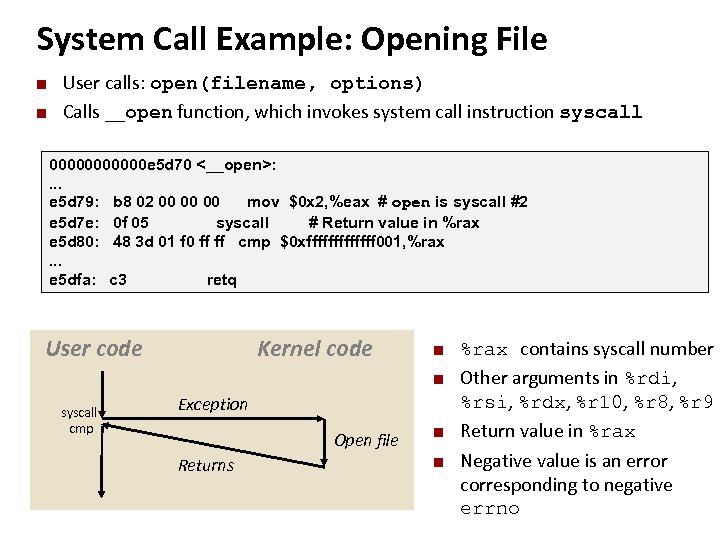

System Call Example: Opening File ¢ ¢ Carnegie Mellon User calls: open(filename, options) Calls __open function, which invokes system call instruction syscall 000000 e 5 d 70 <__open>: . . . e 5 d 79: b 8 02 00 00 00 mov $0 x 2, %eax # open is syscall #2 e 5 d 7 e: 0 f 05 syscall # Return value in %rax e 5 d 80: 48 3 d 01 f 0 ff ff cmp $0 xfffffff 001, %rax. . . e 5 dfa: c 3 retq User code Kernel code ¢ ¢ syscall cmp Exception Open file Returns ¢ ¢ %rax contains syscall number Other arguments in %rdi, %rsi, %rdx, %r 10, %r 8, %r 9 Return value in %rax Negative value is an error corresponding to negative errno

Carnegie Mellon System call ¢ ¢ ¢ Applications should be prevented to directly access hardware such as § Physical memory, § disk, § network, § halt But nevertheless, they need to access these resources in a controlled way: § Read/write their own memory § Access the files that they have permission § Access the network for its own communications § Halt Processors run at different security levels: § User level: § Kernel-level:

Carnegie Mellon System calls ¢ Programming interface to the services provided by the OS § A set of functions (“API” (Application Programming Interface)) provided by the OS to the user applications § Allow the user applications to access hardware in a controlled way ¢ System calls are functions that can directly access hardware

Carnegie Mellon Library example

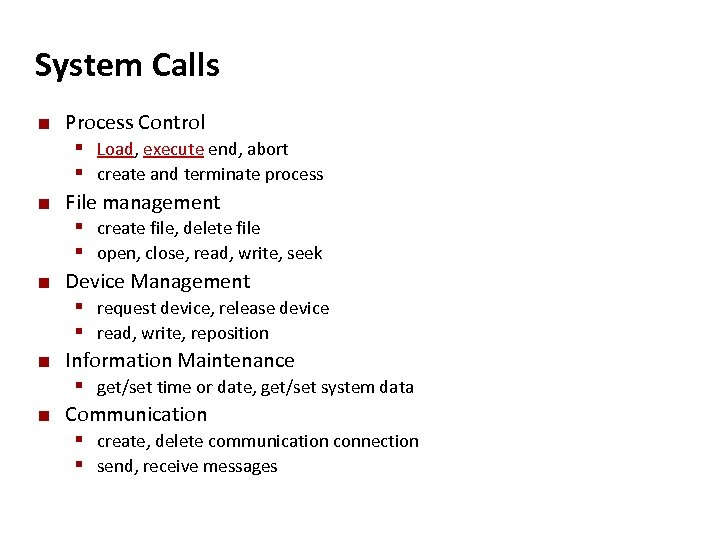

Carnegie Mellon System Calls ¢ ¢ ¢ Process Control § Load, execute end, abort § create and terminate process File management § create file, delete file § open, close, read, write, seek Device Management § request device, release device § read, write, reposition Information Maintenance § get/set time or date, get/set system data Communication § create, delete communication connection § send, receive messages

Carnegie Mellon Most common System API ¢ Most common system API § POSIX API (most versions of UNIX, Linux, and Mac OS X) § Win 32 API for Windows ¢ On Unix, Unix-like and other POSIX-compliant operating systems, popular system calls are open, read, write, close, wait, exec, fork, exit, and kill

Carnegie Mellon Most common System API ¢ ¢ Most common system API § POSIX API (most versions of UNIX, Linux, and Mac OS X) § Win 32 API for Windows POSIX (IEEE 1003. 1, ISO/IEC 9945) § Very widely used standard based on (and including) C-language § Defines both system calls and § compulsory system programs together with their functionality and command-line format § – E. g. ls –w dir prints the list of files in a directory in a ‘wide’ format § Complete specification is at http: //www. opengroup. org/onlinepubs/9699919799/nframe. html ¢ Win 32 (Microsoft Windows based systems) § Specifies system calls together with many Windows GUI routines § VERY complex, no really complete specification

3e3ae83205112c3171a4998dfd30988b.ppt