British History Part 2 – After the Normans

British History Part 2 – After the Normans

Late British History After the Normans, British history can be divided into “Dynasties” Anglo-Normans (1066 – 1215) Middle Ages (1216 – 1347) Late Medieval (1348 – 1484) Tudors (1485 – 1602) Stuarts (1603 – 1713) Georgians (1714 – 1836) Victorians (1837 – 1900)

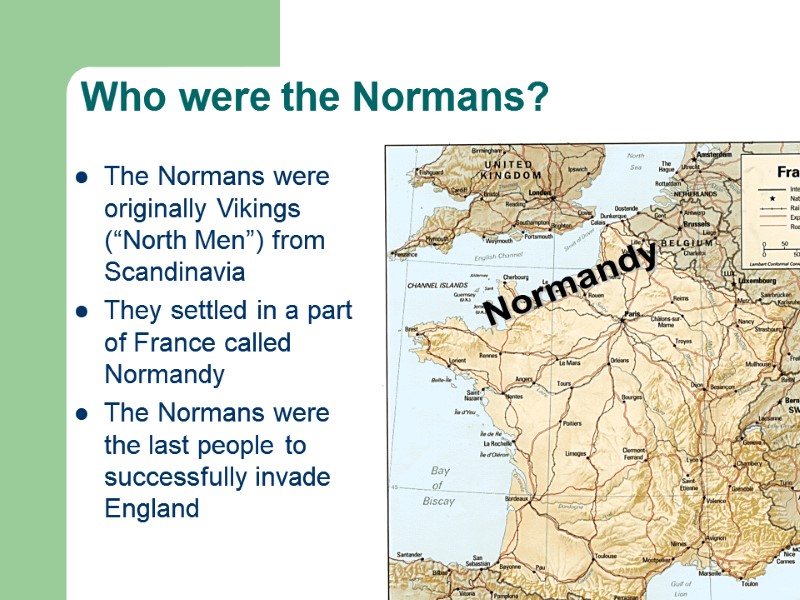

Who were the Normans? The Normans were originally Vikings (“North Men”) from Scandinavia They settled in a part of France called Normandy The Normans were the last people to successfully invade England Normandy

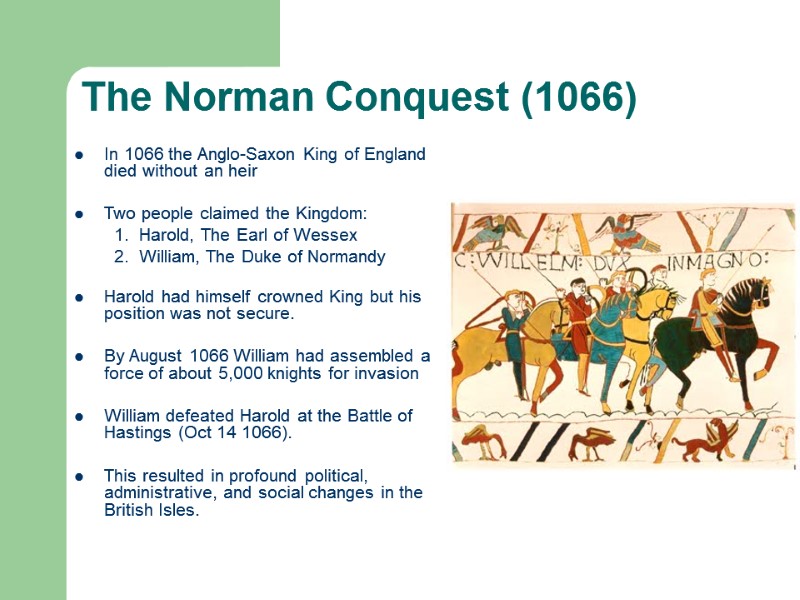

The Norman Conquest (1066) In 1066 the Anglo-Saxon King of England died without an heir Two people claimed the Kingdom: Harold, The Earl of Wessex William, The Duke of Normandy Harold had himself crowned King but his position was not secure. By August 1066 William had assembled a force of about 5,000 knights for invasion William defeated Harold at the Battle of Hastings (Oct 14 1066). This resulted in profound political, administrative, and social changes in the British Isles.

William the Conqueror William was crowned in Westminster Abbey on Christmas Day 1066. However, native revolts continued until 1071. England was divided among 180 Norman “tenants in chief” (basically “Lords”) William brought about many changes in British culture

Anglo-Normans (1066 – 1215) Military conquest followed by settlement and firm administration led to the Normanisation of England, Wales and lowland Scotland. William's victory brought England into closer contact with western Europe. Cultural and economic links with France and continental Europe were re-established. Stone castles became a common sight, serving as administrative centres as well as military and economic strongpoints.

What the Normans did… There were considerable changes in the social structure of the British kingdoms as a new aristocracy was introduced However, the Anglo-Saxon central and local governments and judicial system were retained The “English” language disappeared in official documents, it was replaced by Latin, then by Norman-French. Written English slowly reappeared in the 13th century.

Knights & Feudalism Feudalism originated in France, and was brought to England by the Normans The obligations and relations between lord, vassal and fief form the basis of feudalism Lords (Land owners), Vassals (Knights) Fiefs (Land). In exchange for use of the fief, the vassal would provide military service to the lord. Knights were supported by peasants who worked to produce food and ideologically supported by the church.

The Domesday Book (1086) The Domesday Book was the result of a great survey by William I He sent officials to 13,418 places to find out who lived there and what they owned. The purpose of the survey was for tax collection, or possibly as a way of resolving disputed titles and lands. Domesday was the most complete record of any country at that time and continued to be consulted on legal and administrative matters into the Middle Ages.

The Middle Ages (1216-1347) During the thirteenth century, England and Scotland developed clearer self-identities. In England's case, this was as a result of the loss of most of her continental possessions which focused the monarchy's attention closer to home. There were large constitutional changes and the period saw the beginning of parliament to advise the king. Wales was conquered by the military campaigns of Edward I but his wars in France, Scotland and Ireland were less successful.

The Beginning of Parliament 1236 - 1307 The first reference to a 'parliament' was made in 1236 In 1254, the first meeting of a parliament took place Representatives were two knights from each shire. Parliament developed through the reign of Edward I to a role beyond that of 'high court'.

Late Medieval (1348 – 1484) This period was dominated by the long period of conflict known as the Hundred Years' War Profound social and economic changes were brought about by the Black Death (bubonic plague). The popular and successful Edward III reigned for fifty years, presiding over a mixed period of success for England in France. Parliament continued to develop and English rather than French became the language of daily use. A new dynasty - the Stewarts - was established Scotland. They would eventually rule England

The Black Death (1348) In 1348, the bubonic plague arrived in Britain through the southern coast ports. Known as the Black Death, the disease was spread by fleas living in the fur of rats. The plague reached London by September 1348 and Scotland, Wales and Ireland in the winter of 1349. Between 10-30% of the population died The plague returned periodically until the seventeenth century. The first few outbreaks severely reduced the fertility and density of the population. Labour became scarcer Poorer land was simply abandoned, and many villages were never re-occupied.

Tudors (1485 – 1602) Known as the “Early Modern” period of British history. The Tudors ruled in England and the Stuarts in Scotland. In both realms, as the century progressed, there were new ways of approaching old problems. Henry VIII of England and James IV of Scotland were both cultured, educated Renaissance princes with a love of learning and architectural splendour. Henry broke away from the Catholic Church to form the Church of England (of which he had himself proclaimed Head). The early modern period was an era where women exercised more influence: Catherine de Medici in France, Elizabeth and Mary in England and Mary in Scotland ruled as their male counterparts had done before them.

Circumnavigation of the globe 1578 - 1580 On 13 December 1577, Francis Drake, on board his ship the Pelican, left Plymouth on a voyage that would take him round the world. In August 1578, Drake passed through the Magellan Strait (the south of South America) and entered the Pacific Ocean. By June 1579, Drake had landed on the coast of modern California (which he claimed for England as 'New Albion'). On 26 September 1580, the navigator returned to Plymouth in his ship, renamed as the Golden Hind. The following April, Drake was knighted by Elizabeth I on board ship.

The Stuarts (1603 – 1713) King Charles I was unable to work with Parliament so he attempted to rule without it. This lead to a civil war, and the execution of Charles I. England became a republic (no Kings or Queens) for a short time until the restoration of the monarchy 1660. Shortly afterwards, a devastating plague swept through the country followed by the Great Fire of London 1666. Compromise between the crown and Parliament finally achieved a balanced government and the two kingdoms of England and Scotland were joined in the 1707 Act of Union.

The Gunpowder Plot (1605) On 5 November 1605, a plot was discovered to blow up parliament with gunpowder stored in the cellar. Guy Fawkes was one of the conspirators. He was captured and executed. King James I declared 5 November a day of national celebration. “Guy Fawkes Day” is still celebrated today

The Rise of the Industrial Revolution From 1430, people in Europe discovered sea routes to Asia and America. England made great gains from overseas trade. England became wealthy and people invested in the making of machines and setting up factories. The large overseas market encouraged people to produce more products quicker and of better quality, so they invested in the production of machines in England. A banking system developed - the banks lent money to “industrialists” who used the money for industrial development, which led to the Industrial Revolution. The fast growth of science and technology since the 17th century helped the rise of the Industrial Revolution. It led to population growth, the basis for the invention of machines and the Agricultural Revolution.

Why the Industrial Revolution started in Britain Britain was able to succeed in the Industrial Revolution because of its plentiful resources. Britain had a dense population for its small geographical size. The agricultural revolution made a supply of labour readily available (urbanisation). Local supplies of coal, iron, lead, copper, tin, limestone and water power, resulted in excellent conditions for the development and expansion of industry. The stable political situation in Great Britain from around 1688

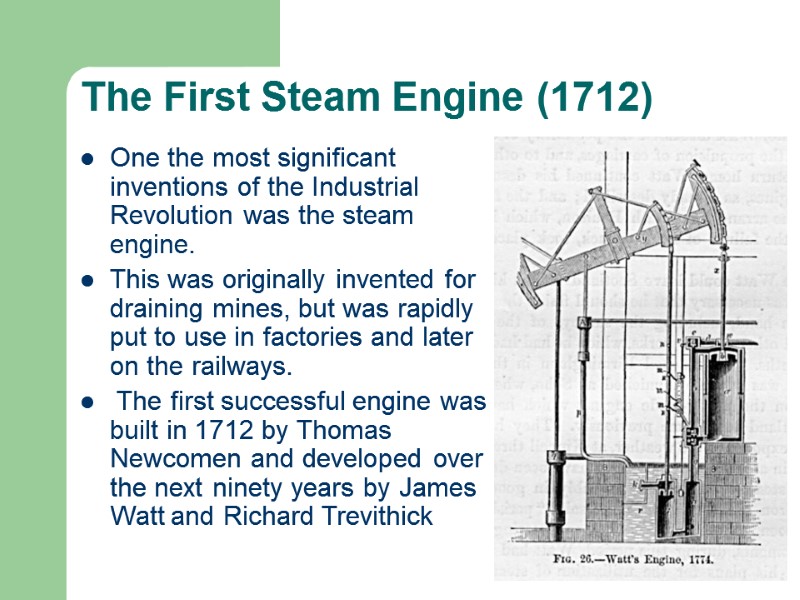

The First Steam Engine (1712) One the most significant inventions of the Industrial Revolution was the steam engine. This was originally invented for draining mines, but was rapidly put to use in factories and later on the railways. The first successful engine was built in 1712 by Thomas Newcomen and developed over the next ninety years by James Watt and Richard Trevithick

The Georgians (1714 – 1836) With these changes came increased population and increased wealth (for some). Politically, the Georgian period was a period of confrontation. Britain became involved in conflicts with India, her American colonies and continental Europe. Because of its financial, naval and military strength, the British government tended to prevail. The Georgian period was one of change. There was a new dynasty and the infrastructure of Britain was changing. Agricultural developments were followed by industrial innovation. This, in turn, led to urbanisation and the need for better communications. Britain became the world's first modern society.

The Napoleonic wars 1803 - 1815 Britain, Prussia, Russia, Austria and Sweden formed a new coalition, which defeated Napoleon. He returned to Paris in 1815, but was finally defeated at Waterloo by Wellington and his Prussian allies, on 18 June. After the French Revolution, Napoleon I of France began a series of European wars. He wanted to rule all of Europe. In 1805, Napoleon's planned invasion of Britain from France failed at Trafalgar. Napoleon then decided to invade Russia but was defeated by the Russian resistance, losing some 380,000 men.

Colonisation of the Antipodes - penal colonies 1788 The majority of these convicts were young men, many of whom had committed only petty crimes. New South Wales opened to free settlers in 1819. By 1858, transportation of convicts was abolished. The colonisation of Australia and New Zealand began with the desire to find a place to put prisoners after the original American colonies were lost. The first shipload of British convicts landed in Australia in 1788, on the site of the future city of Sydney.

The union with Ireland and adoption of the Union Flag 1801 After bribery of the Commons and gentry, Britain and Ireland were formally united, with seats for 132 Irish members in Parliament The red cross of St Patrick was incorporated in the Union flag to give the present flag of the United Kingdom Because of fighting between Catholics and Protestants in Ireland, the Prime Minister, William Pitt, concluded that direct rule from London was the only solution.

The Victorians (1837 – 1900) During Queen Victoria's reign, the revolution in industrial practices continued to change British life. With it came increased urbanisation and a burgeoning communications network (Railways, canals, telegraph). The industrial expansion also brought wealth and, in the nineteenth century, Britain became a champion of Free Trade across her massive Empire. Both industrialisation and trade were glorified in the Great Exhibitions, However by 1900, Britain's industrial advantage was being challenged successfully by other nations such as the USA and Germany. The Empire witnessed renewed conflict, although Victoria' reign can be seen as the imperial Golden Age

Irish famine 1845 - 1850 When the potato crop failed (a staple of the Irish diet), over 1,000,000 Irish citizens died. A further 1-2,000,000 emigrated (mainly to Britain and the United States). The Irish rural economy had come to rely on the potato too much as a cheap and available source of food. The crisis was not helped by poor weather, epidemic disease and a slow response from the British government.

Education Act 1870 This ‘act’ provided mass education on a scale not seen before. The State became more involved in the running of schools. Elected school boards were given powers to enforce attendance of most children below the age of thirteen By 1874, over 5,000 new schools had been founded.

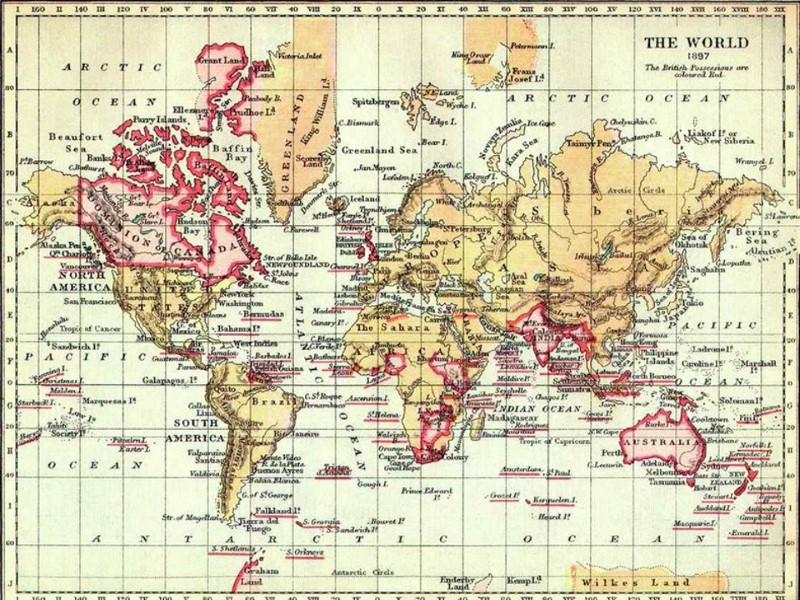

The British Empire The British Empire was the world's first global power It was a product of the “European Age of Exploration” following the discovery of the Americas in the 15th century. By 1921, the British Empire governed a population of about 470–570 million people (1/4 of the world's population) It covered about 37 million square kilometers, almost a third of the world's total land area.

11598-after_the_normans.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 29