ddccb693fa0039b2c924dee90e43fd5e.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 21

British blue notes and backbeats ─ musicological missing links ─ Philip Tagg Faculté de musique, Université de Montréal (November 2004) An example of how musicology can contribute to the defalsification of canonic consensus in the history of North American popular music

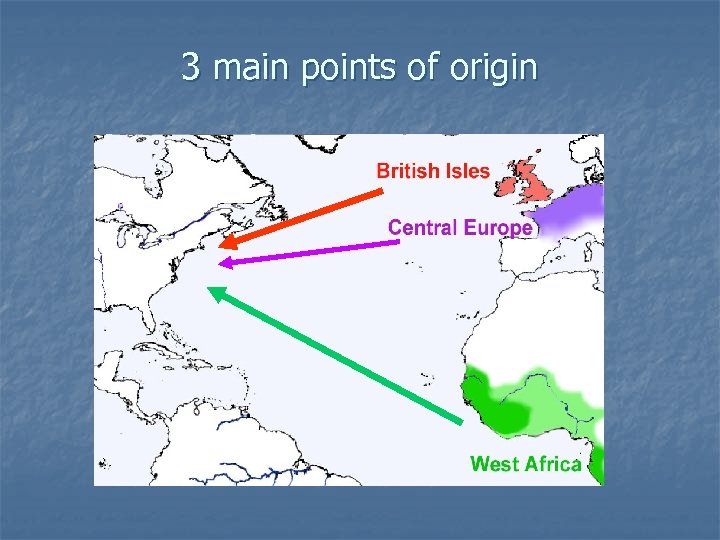

3 main points of origin

The problem n n n Identification of the ‘corporeal’ with African music Identification of the ‘cerebral’ with European music Identification of pitches outside the twelve-note tempered scale as foreign (to ‘us’), ergo African Identification of pitches within the twelve-note tempered scale as European Identification of rhythmic complexity and of improvisation as African Identification of rhythmic simplicity and lack of improvisation as European

Presentation overview 1. General patterns of migration/deportation • West African • British 2. Musicological zoom-in • British blue notes • British backbeats and cross-rhythm • Melismatic ornamentation 3. Conclusions and consequences

![Deporting Africans (1) Map source - http: //www. ev-stift-gymn. guetersloh. de/uforum/black_history/slavery/triangle_trade. html [040506] Deporting Africans (1) Map source - http: //www. ev-stift-gymn. guetersloh. de/uforum/black_history/slavery/triangle_trade. html [040506]](https://present5.com/presentation/ddccb693fa0039b2c924dee90e43fd5e/image-5.jpg)

Deporting Africans (1) Map source - http: //www. ev-stift-gymn. guetersloh. de/uforum/black_history/slavery/triangle_trade. html [040506]

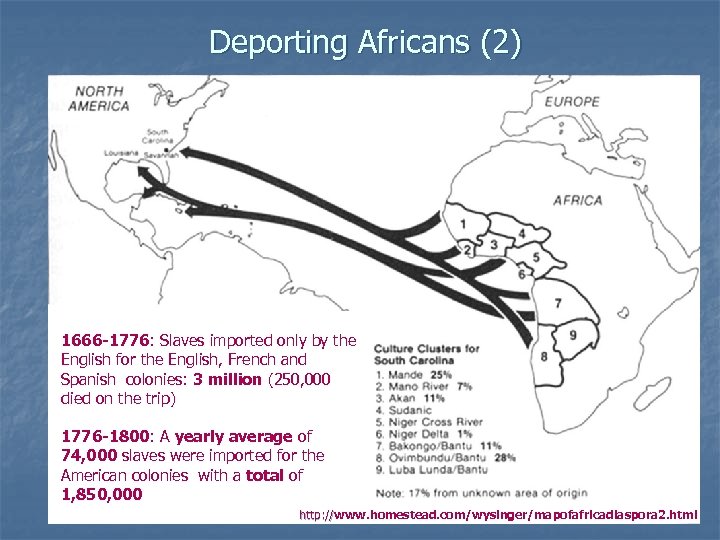

Deporting Africans (2) 1666 -1776: Slaves imported only by the English for the English, French and Spanish colonies: 3 million (250, 000 died on the trip) 1776 -1800: A yearly average of 74, 000 slaves were imported for the American colonies with a total of 1, 850, 000 http: //www. homestead. com/wysinger/mapofafricadiaspora 2. html http: //

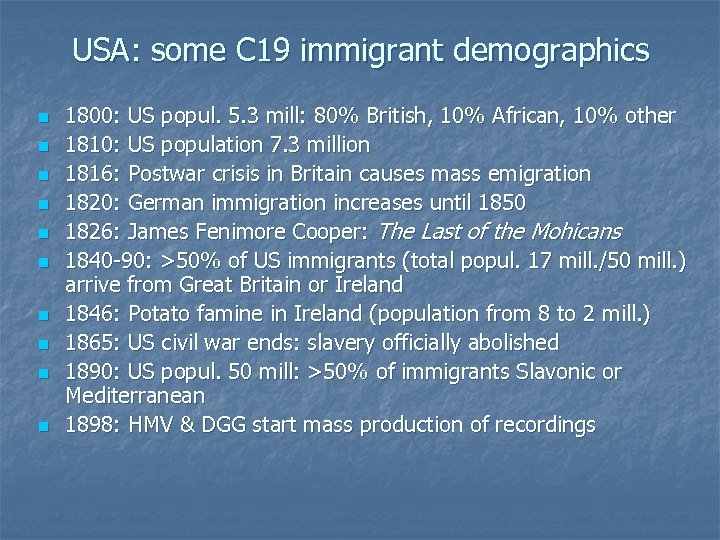

USA: some C 19 immigrant demographics n n n n n 1800: US popul. 5. 3 mill: 80% British, 10% African, 10% other 1810: US population 7. 3 million 1816: Postwar crisis in Britain causes mass emigration 1820: German immigration increases until 1850 1826: James Fenimore Cooper: The Last of the Mohicans 1840 -90: >50% of US immigrants (total popul. 17 mill. /50 mill. ) arrive from Great Britain or Ireland 1846: Potato famine in Ireland (population from 8 to 2 mill. ) 1865: US civil war ends: slavery officially abolished 1890: US popul. 50 mill: >50% of immigrants Slavonic or Mediterranean 1898: HMV & DGG start mass production of recordings

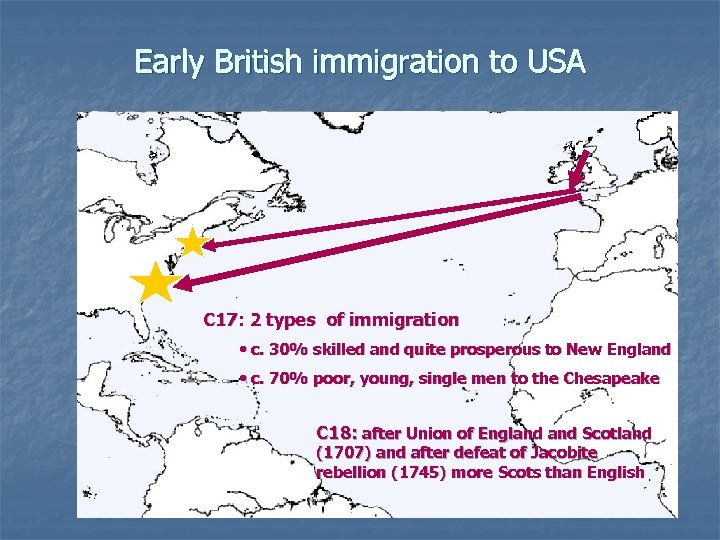

Early British immigration to USA C 17: 2 types of immigration • c. 30% skilled and quite prosperous to New England • c. 70% poor, young, single men to the Chesapeake C 18: after Union of England Scotland (1707) and after defeat of Jacobite rebellion (1745) more Scots than English

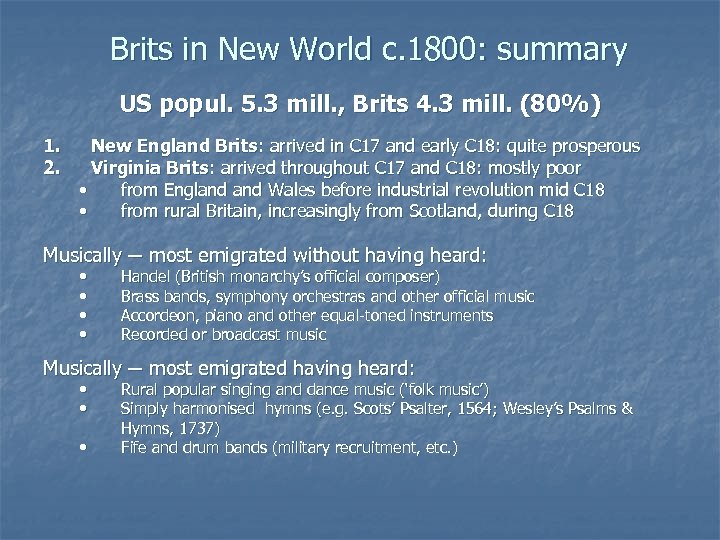

Brits in New World c. 1800: summary US popul. 5. 3 mill. , Brits 4. 3 mill. (80%) 1. 2. New England Brits: arrived in C 17 and early C 18: quite prosperous Virginia Brits: arrived throughout C 17 and C 18: mostly poor • from England Wales before industrial revolution mid C 18 • from rural Britain, increasingly from Scotland, during C 18 Musically ─ most emigrated without having heard: • • Handel (British monarchy’s official composer) Brass bands, symphony orchestras and other official music Accordeon, piano and other equal-toned instruments Recorded or broadcast music Musically ─ most emigrated having heard: • • • Rural popular singing and dance music (‘folk music’) Simply harmonised hymns (e. g. Scots’ Psalter, 1564; Wesley’s Psalms & Hymns, 1737) Fife and drum bands (military recruitment, etc. )

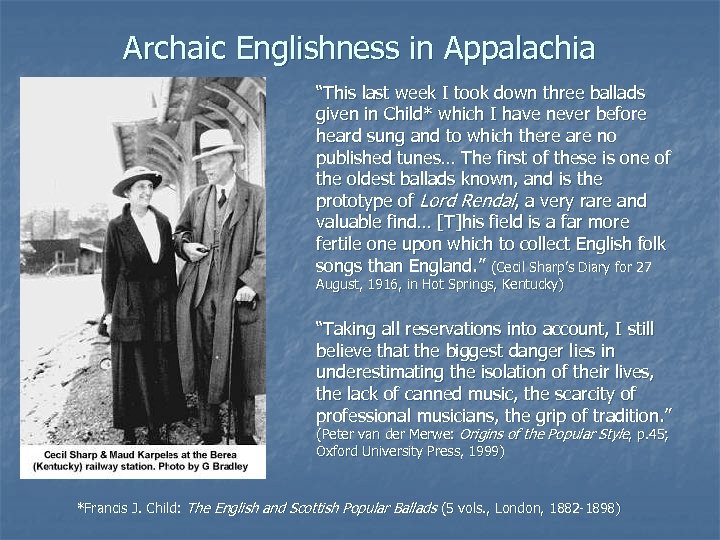

Archaic Englishness in Appalachia “This last week I took down three ballads given in Child* which I have never before heard sung and to which there are no published tunes… The first of these is one of the oldest ballads known, and is the prototype of Lord Rendal, a very rare and valuable find… [T]his field is a far more fertile one upon which to collect English folk songs than England. ” (Cecil Sharp’s Diary for 27 August, 1916, in Hot Springs, Kentucky) “Taking all reservations into account, I still believe that the biggest danger lies in underestimating the isolation of their lives, the lack of canned music, the scarcity of professional musicians, the grip of tradition. ” (Peter van der Merwe: Origins of the Popular Style, p. 45; Oxford University Press, 1999) *Francis J. Child: The English and Scottish Popular Ballads (5 vols. , London, 1882 -1898)

British ‘blue’ notes - examples 1. Weaving song from The Hebrides (1930 s) Blue’ notes (3 rds) at 8, 13 and 17”, then pasted consecutively 2. The Lost Soul (Doc Watson Family, Kentucky, c. 1960) Listen for the woman singing at the highlighted words… What an awful day when the judgement comes And the sinners hear their eternal doom! (their eternal doom!) At the sad decree (at the sad decree) they’ll depart for ay (x 2) Into endless woe (into endless woe), endless woe and gloom. 3. Darling Corey (Doc Watson, Kentucky, c. 1960) Banjo and fiddle in straight D major (with f#). Listen for vocal line’s ‘blue’ notes (f 8 ) at the highlighted words… Wake up, wake up, Darling Corey, what makes you sleep so sound? up Them highway robbers are a-coming, they’re a-ringing around your town.

European (incl. British) backbeats (the TAC in BOOM-TAC) The emphatic backbeat, conventionlally held by rock historians to be an African-American trait, is just as common in music of British and Central European origin. * n Johan Strauss (I): polka c. 1840 (recording not yet available) n Band of the Royal Welch Fusiliers (fife and drum section): God Bless the Prince of Wales (Trad. , rec. c. 1990) *Garry Tamlyn: The Big Beat: Origins and development of snare backbeat and other accompanimental rhythms in Rock 'n' Roll. Ph. D thesis, University of Liverpool, 1998.

British cross rhythm: Scotch snaps Pattern of 2 syllables/notes of which the first is short and accentuated, the second unaccentuated, in British, especially Scottish, English, as in ‘do it’, ‘get it’, ‘matter’, ‘pretty’, ‘Annie’, ‘Peter’, ‘Philip’, ‘David’, ‘Scottish’, etc. , i. e. an inverted dotting (= | e q. |, not | q. e |). 1. Strathspey (Trad. Scottish. , Farquhar Mc. Rae, fiddle; rec. c. 1960). Numerous snaps and straight dottings throughout: impossible to tell position of downbeat until end of first 8 -bar period. 2. Sally Good’n (Trad. Appalachian, Fiddlin’ Eck Robertson, rec. 1926). Snaps at end of each phrase (‘Sally Good’n’, ‘wouldn’t’, ‘couldn’t’, etc. ) 3. Randall Collins (Trad. Appalachian, Norman Blake, rec. 1972). Fifteen dollars is my game, fifteen is my draw, Randall Collins, it is my name in the state of Arkansas. Guitar solo: SNAP SNAP — plus … • “Fifteen” (1 st time) anticipates downbeat (syncopation) • “Randall Collins, it is my name” sung in 6/8 time against 4/4 (cross rhythm) — and with ‘blue’ note —

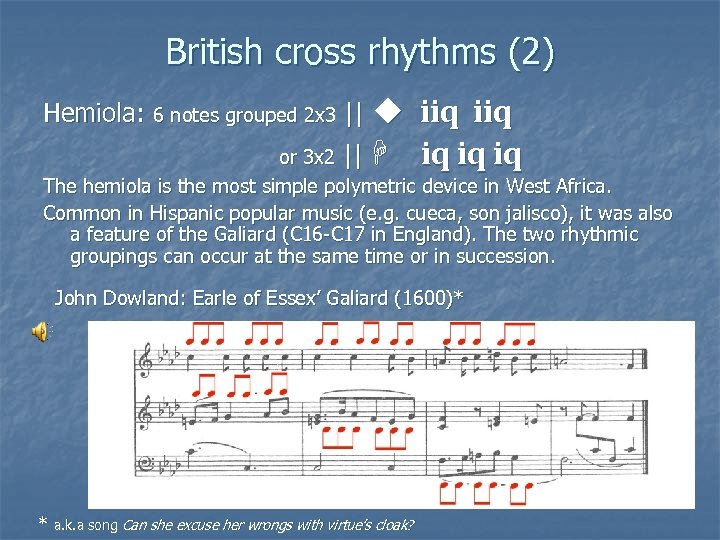

British cross rhythms (2) iiq or 3 x 2 || H iq iq iq Hemiola: 6 notes grouped 2 x 3 || u The hemiola is the most simple polymetric device in West Africa. Common in Hispanic popular music (e. g. cueca, son jalisco), it was also a feature of the Galiard (C 16 -C 17 in England). The two rhythmic groupings can occur at the same time or in succession. John Dowland: Earle of Essex’ Galiard (1600)* * a. k. a song Can she excuse her wrongs with virtue’s cloak?

British melismas Melismatic singing: several notes to same syllable; opposite of syllabic singing (= 1 note per syllable). Improvising florid pentatonic melismas is common in gospel music and conventionally regarded as a typically African(-American) practice. Hebridean home worship (in Gaelic, rec. c. 1960) n n n Lead singer (precentor) melismatically embellishes basic hymn melody. Other singers follow her lead, each producing different but related melodic lines at the same time (heterophony). Individual’s relationship to God essential in radical Protestantism, therefore varying improvised interpretations of same melody. Amazing Grace (rec. Kentucky 1950 s) n n n Lead singer (precentor) summarises each line of hymn in advance for illiterate congregation who follow with complete phrase. Melismatic (and pentatonic) embellishment — ‘snaking the voice’ — by all (no heterophony). Personal relationship to God essential in radical Protestantism (and in U. S. Constitution), therefore embellished melody.

Conclusions n n n n The majority of C 17 and C 18 British immigrants to the USA were poor and from rural areas. They left Britain before the industrial revolution. They settled in the Virginias, the Scots, who emigrated in the mid-to-late C 18, mostly in the hinterland of the southern Appalachians. For at least 150 years they lived in relative isolation from urban cultures. They were unlikely to have been exposed to much music of Central European origin but did come into contact with the music of slaves deported from West Africa. The music of poor rural Brits shared more traits in common with the music of the slave population than with the Central Europeans who sometimes confused ‘Scotch’ and ‘nigger’ melodies (‘blue’ notes, snaps, cross-rhythmic devices, melismas, etc. ). Acculturation between British and African traditions is at the basis of the second wave* of globally diffused North American popular music (from 1940 s, especially after 1955 — R&B, country, rock, etc. ). *First wave: Central European and jazz-influenced popular musics, 1890 -1960.

Ideological and epistemological consequences - 1 n n n Conventional discourses about N. American popular music characterise cultural traditions (incl. musical) according to hegemonic categories institutionalised during the slave trade which provided the economic basis for the foundation of the USA. By so doing, these conventional discourses exaggerate racial difference at the expense of social and cultural similarity. The consequent confusion of racial with cultural traits leads to the identification of false ‘others’, characterisable in either derogatory (racist) or ostensibly positive terms (inverted racism). Positing false ‘otherness’ impedes identification of ‘otherness’ in terms of oppression and alienation in the context of the hegemonic ‘home’ culture (divide et impera). Rationalism, hijacked by capitalism since C 18, was not applied systematically to ‘irrational’ aspects of human organisation (theories of society, the individual, emotions, body, gender, etc. ) until C 20. We still have to create alternative discourses to deal with the sociocultural realities of shared subjectivities.

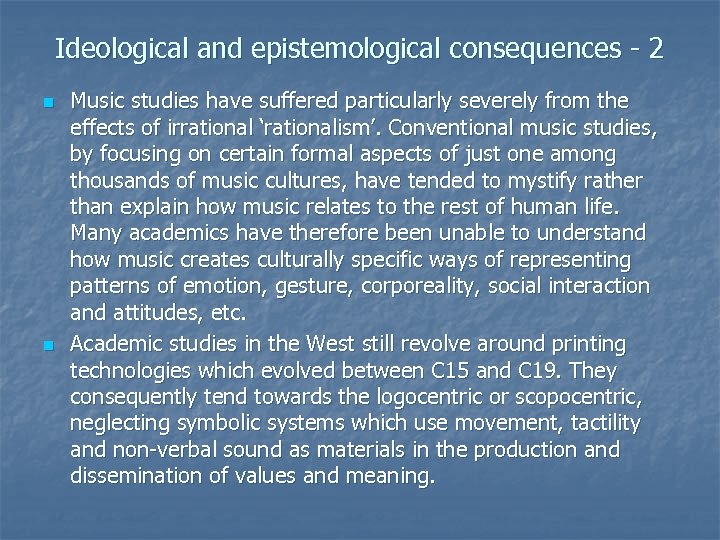

Ideological and epistemological consequences - 2 n n Music studies have suffered particularly severely from the effects of irrational ‘rationalism’. Conventional music studies, by focusing on certain formal aspects of just one among thousands of music cultures, have tended to mystify rather than explain how music relates to the rest of human life. Many academics have therefore been unable to understand how music creates culturally specific ways of representing patterns of emotion, gesture, corporeality, social interaction and attitudes, etc. Academic studies in the West still revolve around printing technologies which evolved between C 15 and C 19. They consequently tend towards the logocentric or scopocentric, neglecting symbolic systems which use movement, tactility and non-verbal sound as materials in the production and dissemination of values and meaning.

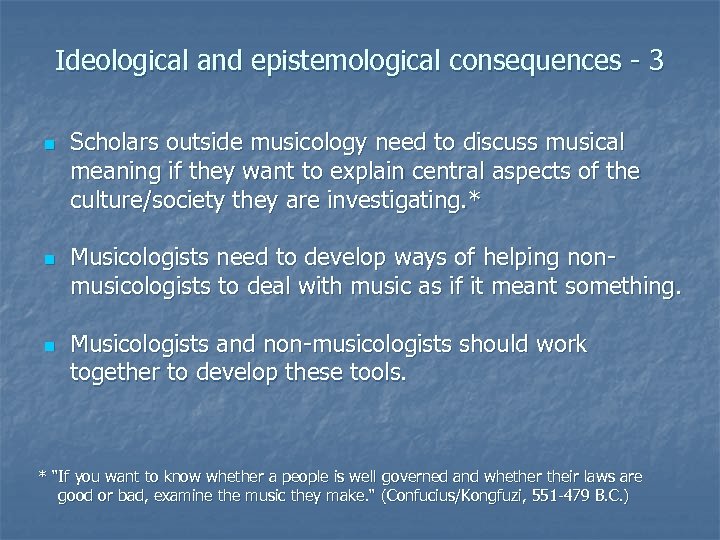

Ideological and epistemological consequences - 3 n n n Scholars outside musicology need to discuss musical meaning if they want to explain central aspects of the culture/society they are investigating. * Musicologists need to develop ways of helping nonmusicologists to deal with music as if it meant something. Musicologists and non-musicologists should work together to develop these tools. * “If you want to know whether a people is well governed and whether their laws are good or bad, examine the music they make. “ (Confucius/Kongfuzi, 551 -479 B. C. )

Verbal references African diaspora http: //www. homestead. com/wysinger/mapofafricadiaspora 2. html Hamm, Charles (1979): Yesterdays. Popular Song in America; New York: Norton Merwe, Peter van der (1989): Origins of the Popular Style; OUP Slave trade (Evangelishe Stift, Gütersloh, Germany) http: //www. ev-stift-gymn. guetersloh. de/uforum/black_history/slavery/triangle_trade. htm Slave Trade (Port Cities: Liverpool, UK) http: //www. mersey-gateway. org/server. php? show=nav. 00100 c Slave trade today (BBC) http: //news. bbc. co. uk/2/hi/africa/3589646. stm Tagg, Philip (1989): "Open Letter about 'Black Music', 'Afro-American Music' and 'European Music'"; Popular Music, 8/3: 285 -298. — Background dates to the history of English-language popular music [041110] http: //www. tagg. org/udem/histanglo/yearpmushist. pdf — Histoire de la musique populaire anglophone (MUL 1121) [041110] http: //www. tagg. org/udem/histanglo. htm — Popular Music Studies: a brief introduction [041110]

Musical references Amazing Grace (mel. US Trad. , printed in Virginia Harmony, 1831) The Folk Box; Elektra/Folkways Elektra EKL-9001 (1964). The Band Drums 1 st Battalion of the The Royal Welch Fusiliers: God Bless The Prince Of Wales (Trad. , n. d. ) The Band Drums 1 st Battalion of the The Royal Welch Fusiliers. RS/1 (c. 1990) Blake, Norman: Randall Collins (US Trad. ) Home In Sulphur Springs. Rounder 0012 (1972). Dowland, John: Earle of Essex Galliard (c. 1610) The Elizabethan Collection. Boots Classical Collection DDD 143 (1988) Hebridean Weaving Song & Hebridean Home Worship (Scottish Trad. ) Musique Celtique Îles Hebrides (ed. T Knudsen). International Folk Music Council: Anthologie de la musique populaire, OCORA OCR 45 (1970). Mc. Rae, Farquhar (fiddle): Strathspey (Scottish Trad. ); unidentified recording c. 1960 Robertson, "Fiddlin'" Eck: Sally Goodin (US Trad. , rec 1926) Southern Dance Music, Vol. 2, Old-Timey LP 101 (1965). Watson, Doc: Darling Corey (US Trad. ) The Doc Watson Family. Smithsonian Folkways SF 40012 (1990). Watson, Doc & "Family": The Lost Soul (US Trad. ) Doc Watson and Clarence Ashley: The Original Folkways Recordings 1960 -1962. Smithsonian Folkways SF 40029/30 (1994).

ddccb693fa0039b2c924dee90e43fd5e.ppt