d6ed415b3f8ddfa881cdbbc7d7a00f47.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 27

Boundary Crossing: Transitioning students to work through authentic employmentbased training in an Australian senior secondary VET program. Terry O’Hanlon-Rose Australian Technical College Alan Roberts Queensland University of Technology

Transitioning young people to work Value in learning at and from work Vocational educators have long recognised the importance of connecting school to work (Billett, 2007; B. Brown, 1998; Misko, 2008; Toner, 2005) A common challenge among OECD countries has been to develop education and training pathways that can accommodate the growing diversity of student needs and interests in the upper secondary level of schooling OECD Thematic Review Transition from Initial Education to Working Life (2000)

Education Reform has been observed as playing a part of economic growth strategies as means to stimulate human capital development (Akçomak & Weel, 2007: UNU Merit Working Paper How do social capital and government support affect innovation and growth? Evidence from the EU regional support programmes). “There is a positive interrelationship between levels of education, measures of social capital, and effectiveness of government support programmes. ” (Akçomak & Weel, 2007; p 1) Human capital and skill shortages and skills development

The Australian Response Recent responses in Australia to skills development at the upper secondary level include a flexible VET in Schools program: VET in Schools program – incorporating non-waged training which complies with AQF requirements School-based Apprenticeships and Traineeships involving a mix of school attendance and a contract of training (waged) employment Usually students attend vocational training or work 1 or 2 days per week Other work-based learning such as Learning of traditional subjects in a work-based environment Work experience Locally developed programs In 2006, Australian Technical Colleges were created with the aim to develop stronger pathways for school students in identified skill shortage areas. They are seen as building on the success of VETi. S and Strengthening the VET in Schools (VETi. S) program in Australia (Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations, 2005)

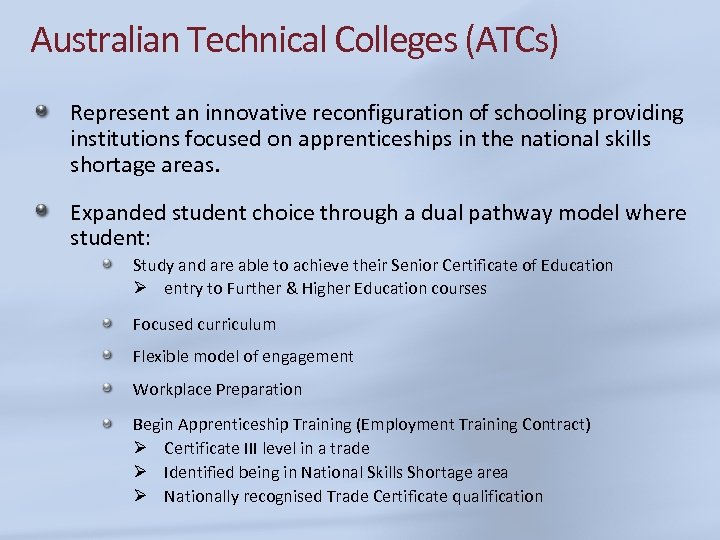

Australian Technical Colleges (ATCs) Represent an innovative reconfiguration of schooling providing institutions focused on apprenticeships in the national skills shortage areas. Expanded student choice through a dual pathway model where student: Study and are able to achieve their Senior Certificate of Education Ø entry to Further & Higher Education courses Focused curriculum Flexible model of engagement Workplace Preparation Begin Apprenticeship Training (Employment Training Contract) Ø Certificate III level in a trade Ø Identified being in National Skills Shortage area Ø Nationally recognised Trade Certificate qualification

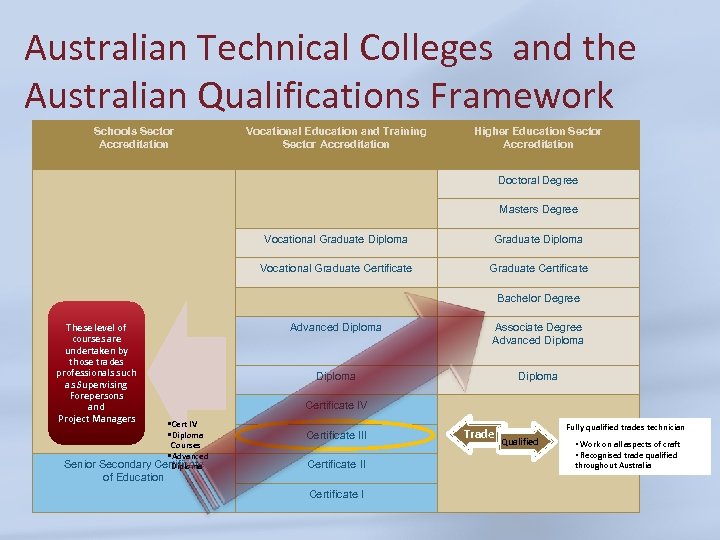

Australian Technical Colleges and the Australian Qualifications Framework Schools Sector Accreditation Vocational Education and Training Sector Accreditation Higher Education Sector Accreditation Doctoral Degree Masters Degree Vocational Graduate Diploma Vocational Graduate Certificate Bachelor Degree These level of courses are undertaken by those trades professionals such as Supervising Forepersons and Project Managers Advanced Diploma Associate Degree Advanced Diploma Certificate IV • Cert IV • Diploma Courses • Advanced Senior Secondary Certificate Diploma of Education Certificate III Certificate I Trade Fully qualified trades technician Qualified • Work on all aspects of craft • Recognised trade qualified throughout Australia

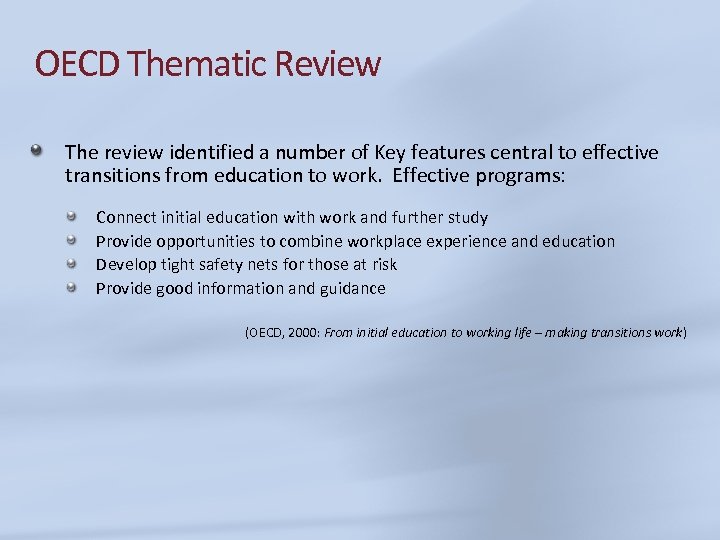

OECD Thematic Review The review identified a number of Key features central to effective transitions from education to work. Effective programs: Connect initial education with work and further study Provide opportunities to combine workplace experience and education Develop tight safety nets for those at risk Provide good information and guidance (OECD, 2000: From initial education to working life – making transitions work)

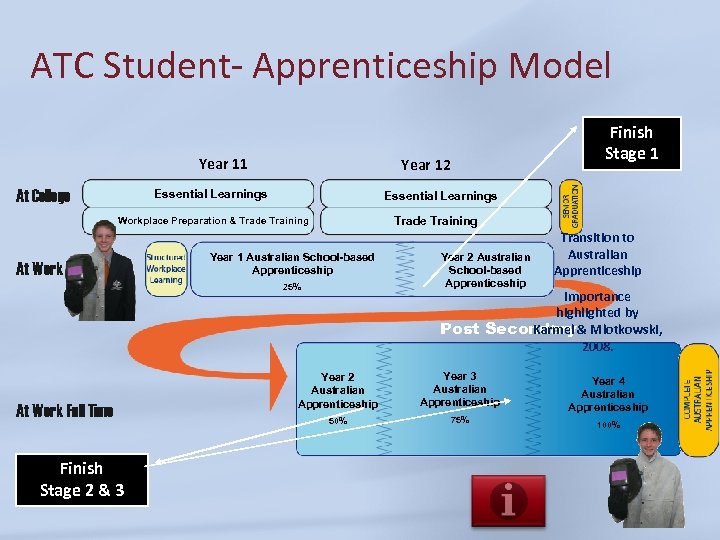

ATC Student- Apprenticeship Model Year 11 At College Year 12 Essential Learnings Trade Training Workplace Preparation & Trade Training At Work Year 1 Australian School-based Apprenticeship 25% At Work Full Time Finish Stage 2 & 3 Finish Stage 1 Year 2 Australian School-based Apprenticeship Transition to Australian Apprenticeship Importance highlighted by Post Secondary& Mlotkowski, Karmel 2008. Year 2 Australian Apprenticeship Year 3 Australian Apprenticeship 50% 75% Year 4 Australian Apprenticeship 100%

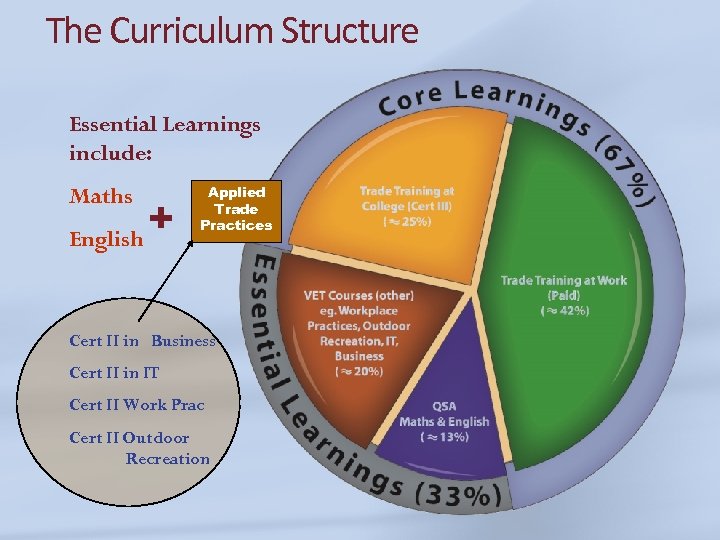

The Curriculum Structure Essential Learnings include: Maths English + Applied Trade Practices Cert II in Business Cert II in IT Cert II Work Prac Cert II Outdoor Recreation

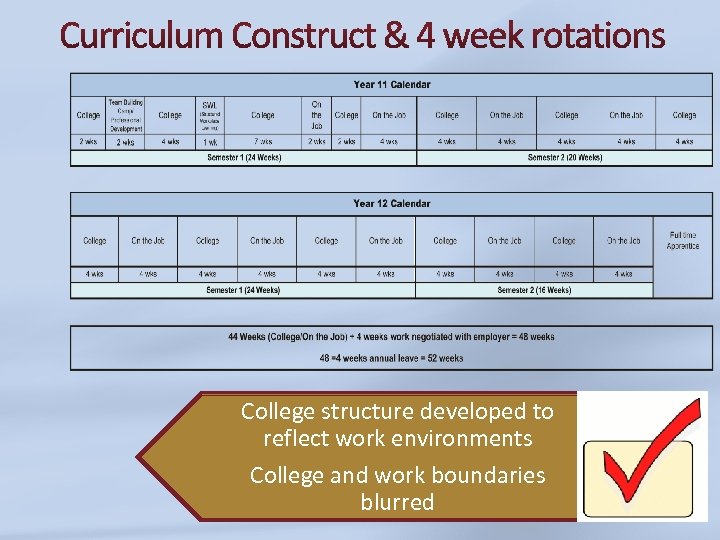

College structure developed to reflect work environments College and work boundaries blurred

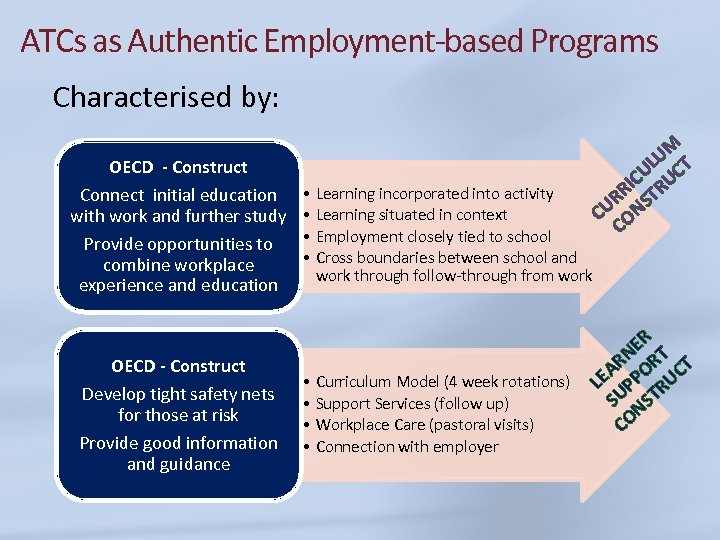

ATCs as Authentic Employment-based Programs Characterised by: OECD - Construct Connect initial education with work and further study Provide opportunities to combine workplace experience and education OECD - Construct Develop tight safety nets for those at risk Provide good information and guidance • Learning incorporated into activity • Learning situated in context • Employment closely tied to school • Cross boundaries between school and work through follow-through from work • Curriculum Model (4 week rotations) • Support Services (follow up) • Workplace Care (pastoral visits) • Connection with employer UM T UL UC C RI TR UR NS C O C ER T RN OR CT A LE PP RU SU NST CO

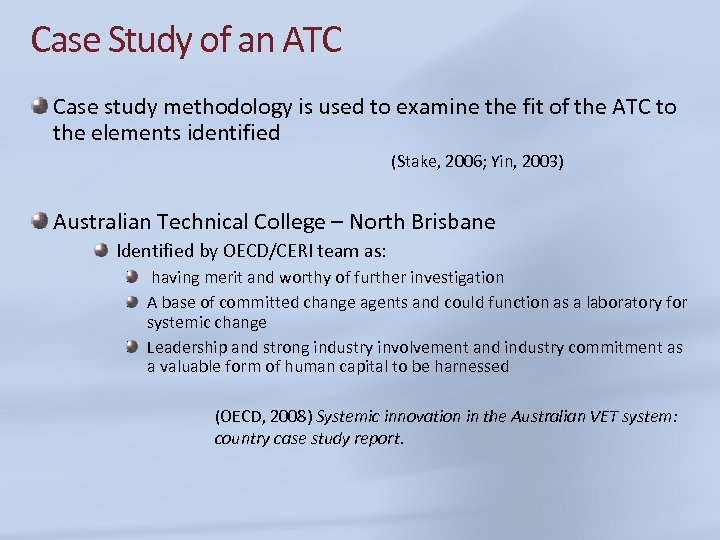

Case Study of an ATC Case study methodology is used to examine the fit of the ATC to the elements identified (Stake, 2006; Yin, 2003) Australian Technical College – North Brisbane Identified by OECD/CERI team as: having merit and worthy of further investigation A base of committed change agents and could function as a laboratory for systemic change Leadership and strong industry involvement and industry commitment as a valuable form of human capital to be harnessed (OECD, 2008) Systemic innovation in the Australian VET system: country case study report.

Quantitative Surveys administered to employers of students undertaking an Australian Qualifications Framework Certificate III (trade qualification) at the Australian Technical College – North Brisbane. Online Surveys administered to students at the Australian Technical College – north Brisbane To eliminate potential bias, an independent researcher was engaged to administer the surveys. Qualitative Twelve students were purposively selected and interviewed to provide qualitative feedback on their experiences at the ATC.

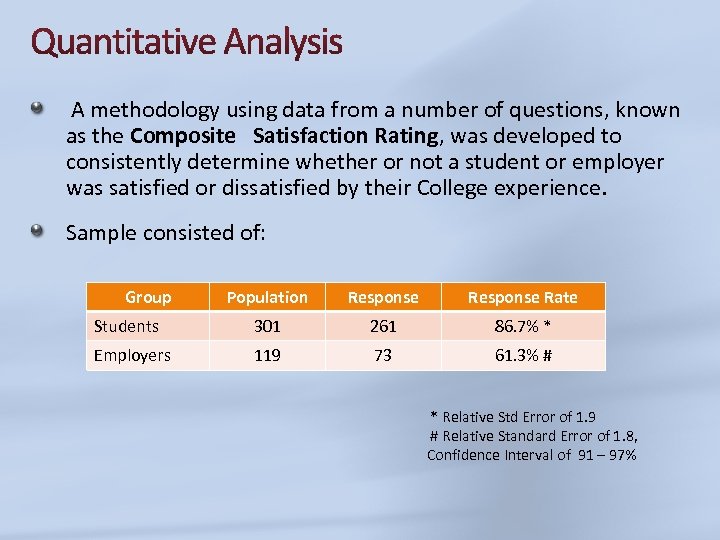

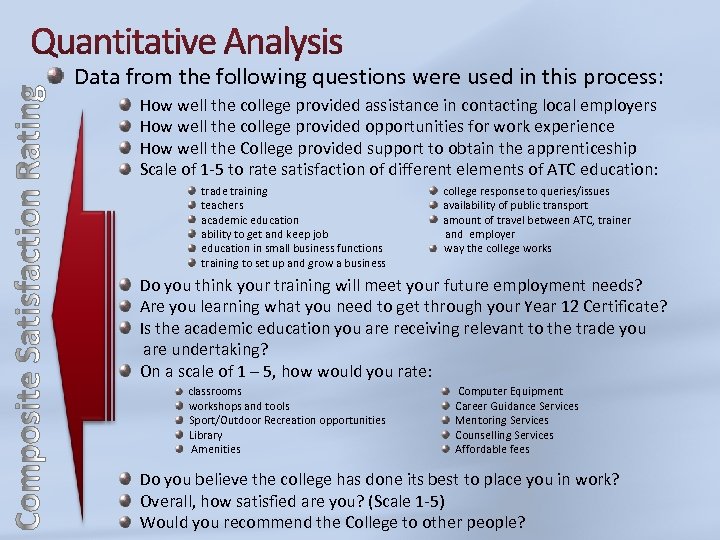

A methodology using data from a number of questions, known as the Composite Satisfaction Rating, was developed to consistently determine whether or not a student or employer was satisfied or dissatisfied by their College experience. Sample consisted of: Group Population Response Rate Students 301 261 86. 7% * Employers 119 73 61. 3% # * Relative Std Error of 1. 9 # Relative Standard Error of 1. 8, Confidence Interval of 91 – 97%

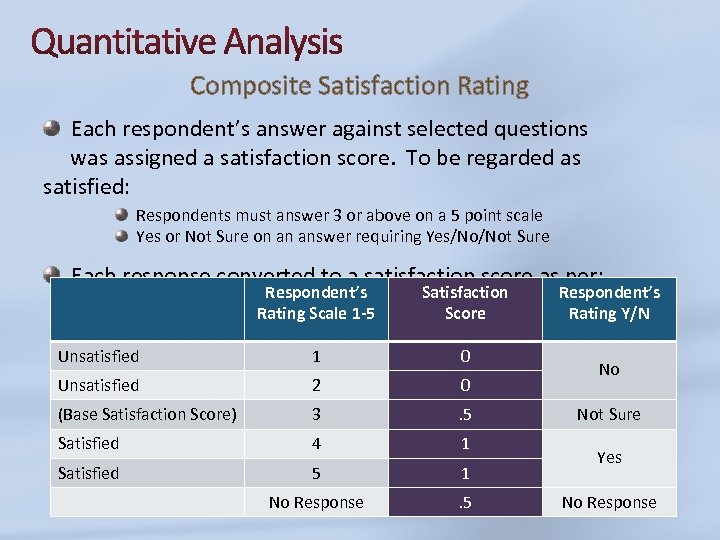

Composite Satisfaction Rating Each respondent’s answer against selected questions was assigned a satisfaction score. To be regarded as satisfied: Respondents must answer 3 or above on a 5 point scale Yes or Not Sure on an answer requiring Yes/No/Not Sure Each response converted to a satisfaction score as per: Respondent’s Rating Scale 1 -5 Satisfaction Score Unsatisfied 1 0 Unsatisfied 2 0 (Base Satisfaction Score) 3 . 5 Satisfied 4 1 Satisfied 5 1 No Response . 5 Respondent’s Rating Y/N No Not Sure Yes No Response

Twelve students were purposively selected and interviewed to provide qualitative feedback on their experiences at the ATC. School activity is authenticated by the trade related learning which is connected to apprentices’ work in order to operate effectively. (Tanggaard, 2007, p. 453) The interview transcript is a typical example of the 12 interviews and demonstrates the concept of “boundary crossing” between work and school, evidenced through the apprentice acknowledging that there are different situations in which he learns.

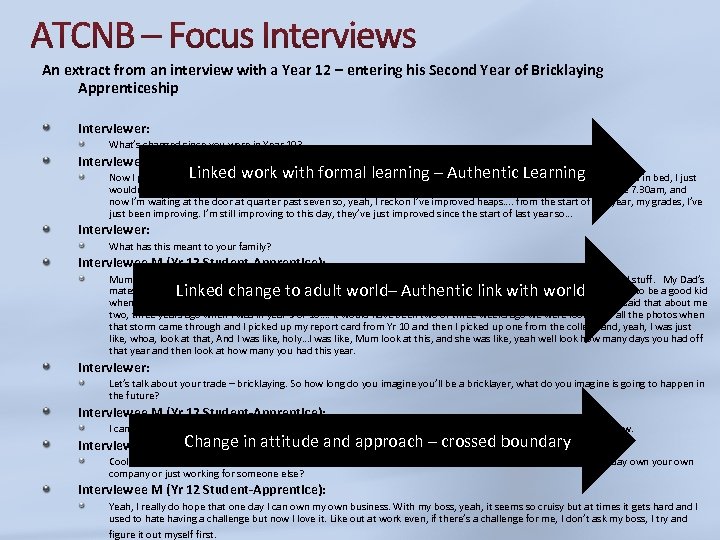

An extract from an interview with a Year 12 – entering his Second Year of Bricklaying Apprenticeship Interviewer: What’s changed since you were in Year 10? Interviewee M (Yr 12 Student-Apprentice): Linked work with formal learning – Authentic Learning Now I pretty much jump out of bed because I just want to get to college. And towards the end of Grade 10 I just stayed in bed, I just wouldn’t go or if I did go I’d rock up and like 9. 30 am. Mum’s a teacher and she’d always be like, we’re leaving before 7. 30 am, and now I’m waiting at the door at quarter past seven so, yeah, I reckon I’ve improved heaps…. from the start of last year, my grades, I’ve just been improving. I’m still improving to this day, they’ve just improved since the start of last year so… Interviewer: What has this meant to your family? Interviewee M (Yr 12 Student-Apprentice): Mum, she thinks I’m changing so much and Dad has also noticed it heaps, like with my shaving and my grooming and stuff. My Dad’s mates say I’m growing up real quick and I’m mature for my age, and they say to my Dad when I’m gone, oh he’s going to be a good kid when he gets older, like a good man when he’s older, he’s so mature for his age. And I don’t think they would have said that about me two, three years ago when I was in year 9 or 10…. it would have been two or three weeks ago we were looking at all the photos when that storm came through and I picked up my report card from Yr 10 and then I picked up one from the college and, yeah, I was just like, whoa, look at that, And I was like, holy…I was like, Mum look at this, and she was like, yeah well look how many days you had off that year and then look at how many you had this year. Linked change to adult world– Authentic link with world Interviewer: Let’s talk about your trade – bricklaying. So how long do you imagine you’ll be a bricklayer, what do you imagine is going to happen in the future? Interviewee M (Yr 12 Student-Apprentice): I can see myself doing it until I have to retire, until they make me retire I think. Just, yeah, I think it’s in my blood now. Interviewer: Change in attitude and approach – crossed boundary Cool, and so do you think with your other experience in business IT and workplace practices, that you might one day own your own company or just working for someone else? Interviewee M (Yr 12 Student-Apprentice): Yeah, I really do hope that one day I can own my own business. With my boss, yeah, it seems so cruisy but at times it gets hard and I used to hate having a challenge but now I love it. Like out at work even, if there’s a challenge for me, I don’t ask my boss, I try and figure it out myself first.

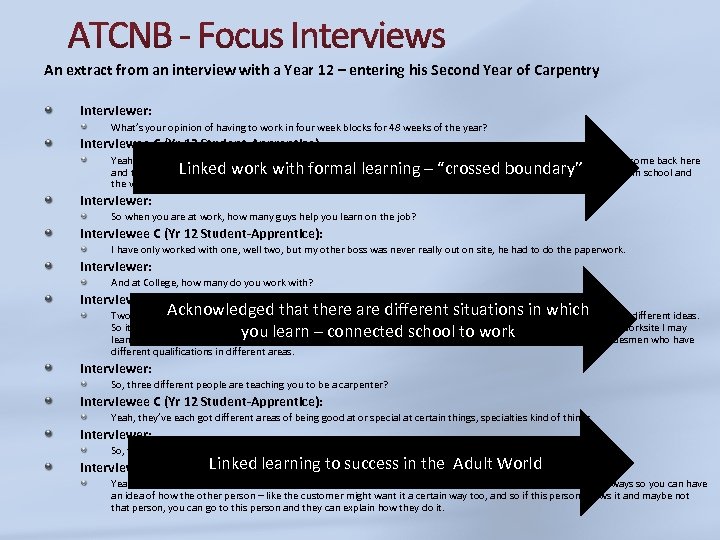

An extract from an interview with a Year 12 – entering his Second Year of Carpentry Interviewer: What’s your opinion of having to work in four week blocks for 48 weeks of the year? Interviewee C (Yr 12 Student-Apprentice): Yeah, I think that’s a really good idea as you actually learn things in that 4 weeks. You learn how to do the job, then come back here and they’re teaching you theory side, and also the practical. So you are still learning about it from both sides, from school and the workforce. And with the 4 weeks you get a lot more time at the practical hands out there and you’re learning. Linked work with formal learning – “crossed boundary” Interviewer: So when you are at work, how many guys help you learn on the job? Interviewee C (Yr 12 Student-Apprentice): I have only worked with one, well two, but my other boss was never really out on site, he had to do the paperwork. Interviewer: And at College, how many do you work with? Interviewee C (Yr 12 Student-Apprentice): Acknowledged that there are different situations in which you learn – connected school to work Two and it’s good to get different sort of people cause Mr X and Mr Y, they’re both different teachers and they have different ideas. So it’s good to learn from different people – three different people. So when I am here I learn this way, but at the worksite I may learn a different way, and a quicker, maybe easier, different or better looking way. So it’s good to learn from tradesmen who have different qualifications in different areas. Interviewer: So, three different people are teaching you to be a carpenter? Interviewee C (Yr 12 Student-Apprentice): Yeah, they’ve each got different areas of being good at or special at certain things, specialties kind of things. Interviewer: So, that helps you get …. Linked learning Interviewee C (Yr 12 Student-Apprentice): to success in the Adult World Yeah, a bigger understanding of different things. Like not just about a set one thing, you’re learning in different ways so you can have an idea of how the other person – like the customer might want it a certain way too, and so if this person knows it and maybe not that person, you can go to this person and they can explain how they do it.

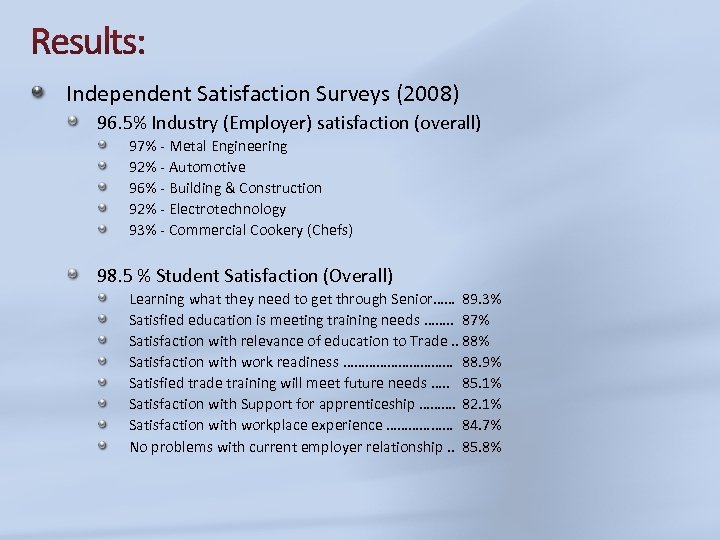

Independent Satisfaction Surveys (2008) 96. 5% Industry (Employer) satisfaction (overall) 97% - Metal Engineering 92% - Automotive 96% - Building & Construction 92% - Electrotechnology 93% - Commercial Cookery (Chefs) 98. 5 % Student Satisfaction (Overall) Learning what they need to get through Senior…… 89. 3% Satisfied education is meeting training needs ……. . 87% Satisfaction with relevance of education to Trade. . 88% Satisfaction with work readiness …………… 88. 9% Satisfied trade training will meet future needs …. . 85. 1% Satisfaction with Support for apprenticeship ………. 82. 1% Satisfaction with workplace experience ……………… 84. 7% No problems with current employer relationship. . 85. 8%

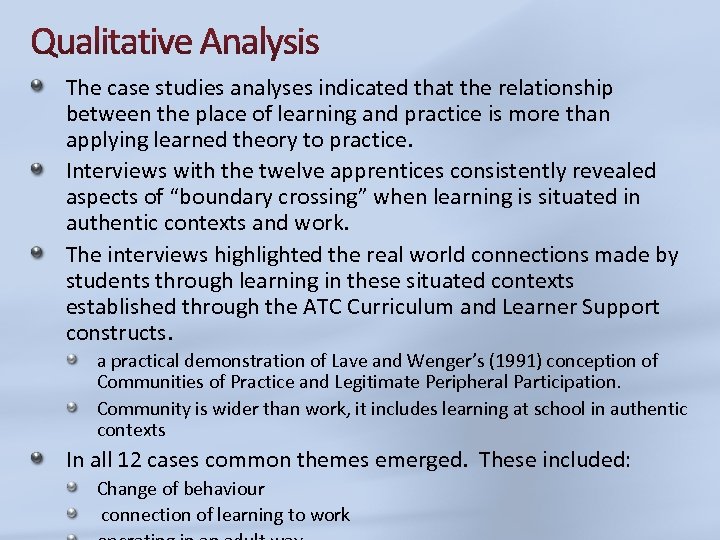

The case studies analyses indicated that the relationship between the place of learning and practice is more than applying learned theory to practice. Interviews with the twelve apprentices consistently revealed aspects of “boundary crossing” when learning is situated in authentic contexts and work. The interviews highlighted the real world connections made by students through learning in these situated contexts established through the ATC Curriculum and Learner Support constructs. a practical demonstration of Lave and Wenger’s (1991) conception of Communities of Practice and Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Community is wider than work, it includes learning at school in authentic contexts In all 12 cases common themes emerged. These included: Change of behaviour connection of learning to work

A Destination Survey of the 2008 Year 12 Cohort was conducted with the following Post Year 12 Outcomes: 98. 25% employed or in further study 92% as full-time apprentice 6% as part-time or full-time study/work 1. 75 % unemployed

The aim of future study is to determine the effectiveness of the different construct approaches to implementing employmentbased training n the Senior Curriculum How does the VETi. S delivery model impact on: Continuation of the apprenticeship Engaging in further education or training Attitudes of employers, students and staff

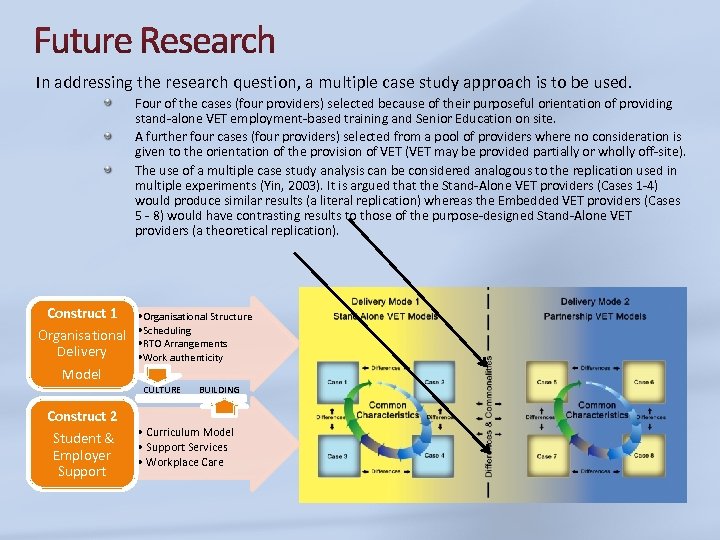

In addressing the research question, a multiple case study approach is to be used. Four of the cases (four providers) selected because of their purposeful orientation of providing stand-alone VET employment-based training and Senior Education on site. A further four cases (four providers) selected from a pool of providers where no consideration is given to the orientation of the provision of VET (VET may be provided partially or wholly off-site). The use of a multiple case study analysis can be considered analogous to the replication used in multiple experiments (Yin, 2003). It is argued that the Stand-Alone VET providers (Cases 1 -4) would produce similar results (a literal replication) whereas the Embedded VET providers (Cases 5 - 8) would have contrasting results to those of the purpose-designed Stand-Alone VET providers (a theoretical replication). Construct 1 Organisational Delivery Model • Organisational Structure • Scheduling • RTO Arrangements • Work authenticity CULTURE Construct 2 Student & Employer Support BUILDING • Curriculum Model • Support Services • Workplace Care

questions

Recent Australian experience The delivery of VETi. S programs places significant burdens on schools, teachers and students because it entails working in environments of adult learning and workplace disciplines and expectations which are far from the normal experience of schools and their personnel (Barnett & Ryan, 2005; Jung et al. , 2004). Lack of flexibility in the school timetabling practices is one of the frequently identified problems of the limitations of schools to implement VETi. S programs (Jung et al. , 2004). Lamb & Vickers (2006) analysed data from LSAY and concluded that VET programs in Schools which were closely aligned with VET system (TAFEs and Private RTOs) resulted in smoother transitions to work Karmel and Mlotkowski (2008) analysed data on school-based apprentices and found that the lowest completion rates of the School-based apprenticeships were in the trades and they further suggested that drop-out after completion of school is relatively high for school-based apprenticeships.

No comprehensive data are available as to the lifespan of participation of employers in VET-in-Schools and industry partnership arrangements but case study evidence by Malley, Keating, Robinson, & Hawke (2001) shows that a high rate of employer turnover is an ongoing issue for many school industry programs. One measure of judgement of the value of school-based apprenticeships to the employer is the longevity of the employer partnership. This is an area where there is little research, highlighting a gap which is explored in this study. Current research concentrates on assessing the most cost-effective delivery of school-based apprenticeships using a cost inputs model with little research concerned with the employment or long-term outcomes of such programs. In 2003, DEST engaged the consortium of The Allen Consulting Group, Deloitte and NCVER to undertake a project that analysed the costs of delivery of vocational education and training (VET) in Schools, including an analysis of cost efficiencies (Allen Consulting Group & Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu, 2003). No comparative analyses of the most effective delivery method of School-based Apprenticeships which compares outcomes of the different delivery options such as those explored by the ATCs has been done.

Data from the following questions were used in this process: How well the college provided assistance in contacting local employers How well the college provided opportunities for work experience How well the College provided support to obtain the apprenticeship Scale of 1 -5 to rate satisfaction of different elements of ATC education: trade training teachers academic education ability to get and keep job education in small business functions training to set up and grow a business college response to queries/issues availability of public transport amount of travel between ATC, trainer and employer way the college works Do you think your training will meet your future employment needs? Are you learning what you need to get through your Year 12 Certificate? Is the academic education you are receiving relevant to the trade you are undertaking? On a scale of 1 – 5, how would you rate: classrooms workshops and tools Sport/Outdoor Recreation opportunities Library Amenities Computer Equipment Career Guidance Services Mentoring Services Counselling Services Affordable fees Do you believe the college has done its best to place you in work? Overall, how satisfied are you? (Scale 1 -5) Would you recommend the College to other people?

d6ed415b3f8ddfa881cdbbc7d7a00f47.ppt