6ecb5ecd5ab0bad56b4fdfa429938e74.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 75

Book 1: Instruction and Academic Interventions Practical Guidelines for the Education of English Language Learners

The Center on Instruction is operated by RMC Research Corporation in partnership with the Florida Center for Reading Research at Florida State University; Horizon Research, Inc. ; RG Research Group; the Texas Institute for Measurement, Evaluation, and Statistics at the University of Houston; and the Vaughn Gross Center for Reading and Language Arts at the University of Texas at Austin. The contents of this Power. Point were developed under cooperative agreement S 283 B 050034 with the U. S. Department of Education. However, these contents do not necessarily represent the policy of the Department of Education, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government. 2007 The Center on Instruction requests that no changes be made to the content or appearance of this product. To download a copy of this document, visit www. centeroninstruction. org

Practical Guidelines for the Education of English Language Learners Authors David J. Francis, Mabel Rivera Center on Instruction English Language Learners Strand Texas Institute for Measurement, Evaluation, and Statistics University of Houston Nonie K. Lesaux, Michael J. Kieffer Graduate School of Education Harvard University Héctor Rivera Center on Instruction English Language Learners Strand Texas Institute for Measurement, Evaluation, and Statistics University of Houston

Practical Guidelines for the Education of English Language Learners Research-based Recommendations for Instruction and Academic Interventions Research-based Recommendations for Serving Adolescent Newcomers Research-based Recommendations for the Use of Accommodations in Large-scale Assessments

Book 1: Instruction and Intervention Foreword Overview Reading Conceptual Framework Recommendations Mathematics Conceptual Framework Considerations

Seminal Research Reviews August, D. L. , & Shanahan, T. (Eds. ). (2006). Developing literacy in a second language: Report of the National Literacy Panel. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Genessee, F. , Lindholm-Leary, K. , Saunders, W. M. , & Christian, D. (Eds. ). (2006). Educating English language learners: A synthesis of research evidence. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Instruction and Intervention: Outline Demographics Current Policies and Achievement Conceptual Framework Research-Based Recommendations for Instruction and Intervention Strategies for Effective Instruction

Demographics

Who are English Language Learners? • National-origin-minority students with limited proficiency of English; • Heterogeneous; • Membership defined by limited proficiency in English language use, which directly affects learning and assessment; • Membership is expected to be temporary.

Frequently Used Terms Language Minority Student (LM): a child who hears and/or speaks a language other than English at home. Limited English Proficient (LEP) : an LM students whose limited command of English prevents independent participation in instruction (federal term). English Language Learner (ELL): an LM student designated locally (i. e. , by the state) as limited English Proficient.

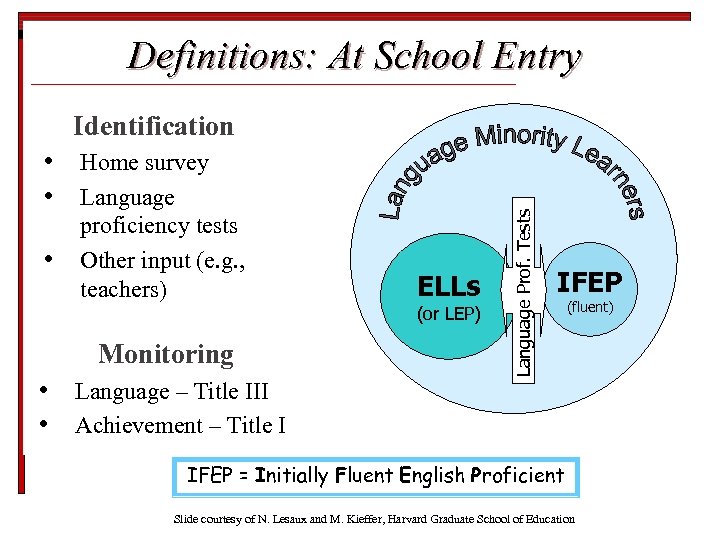

Definitions: At School Entry • • • Home survey Language proficiency tests Other input (e. g. , teachers) ELLs (or LEP) Monitoring • • Language Prof. Tests Identification IFEP (fluent) Language – Title III Achievement – Title I IFEP = Initially Fluent English Proficient Slide courtesy of N. Lesaux and M. Kieffer, Harvard Graduate School of Education

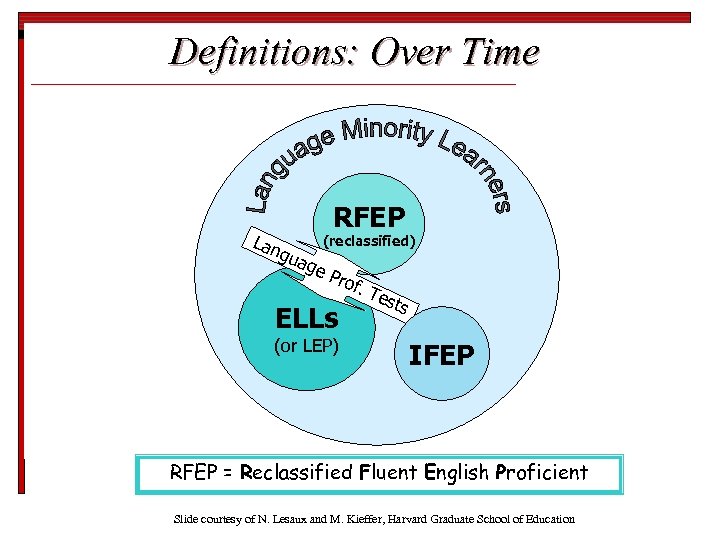

Definitions: Over Time Lan RFEP (reclassified) gua g e. P rof. ELLs (or LEP) Tes ts IFEP RFEP = Reclassified Fluent English Proficient Slide courtesy of N. Lesaux and M. Kieffer, Harvard Graduate School of Education

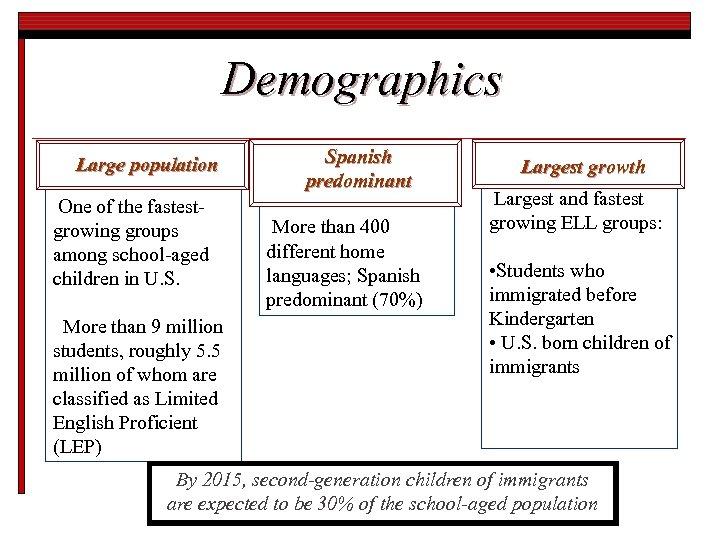

Demographics Large population One of the fastestgrowing groups among school-aged children in U. S. More than 9 million students, roughly 5. 5 million of whom are classified as Limited English Proficient (LEP) Spanish predominant More than 400 different home languages; Spanish predominant (70%) Largest growth Largest and fastest growing ELL groups: • Students who immigrated before Kindergarten • U. S. born children of immigrants By 2015, second-generation children of immigrants are expected to be 30% of the school-aged population

Learning challenges ELLs face unique learning challenges: • to develop the content-related knowledge and skills defined by state standards; • • • while simultaneously acquiring a second (or third) language; at a time when their first language is not fully developed (e. g. , young children); to demonstrate their learning on assessments in English, their second language.

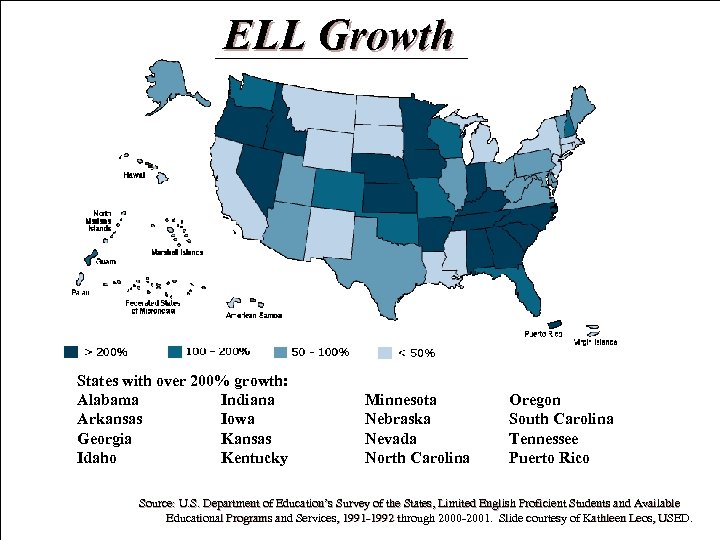

ELL Growth States with over 200% growth: Alabama Indiana Arkansas Iowa Georgia Kansas Idaho Kentucky Minnesota Nebraska Nevada North Carolina Oregon South Carolina Tennessee Puerto Rico Source: U. S. Department of Education’s Survey of the States, Limited English Proficient Students and Available Educational Programs and Services, 1991 -1992 through 2000 -2001. Slide courtesy of Kathleen Leos, USED.

ELL Performance Outcomes • Some states have begun to look at the performance of ELLs on state tests after they have gained proficiency in English. • Although some reclassified ELLs do well, many students who have lost the formal LEP designation continue to struggle with: • academic text, • content-area knowledge, and • oral language skills.

Current Policy and Academic Achievement

English Language Learners and the No Child Left Behind Act ELLs present unique challenges to: • • Teachers, Administrators, Assessment systems, and Accountability systems.

English Language Learners and the No Child Left Behind Act NCLB: • • High standards of learning and instruction for all students; English Language Learners one of five areas of concentration to advance student achievement; Increased awareness of the academic needs and achievement of ELLs; Schools, districts, and states held accountable for teaching English and content knowledge to ELLs.

English Language Learners and the No Child Left Behind Act Under NCLB, state education agencies are held accountable for the progress of ELLs in two ways: • Adequate Yearly Progress (AYP) expectations for reading and mathematics under Title I, and • Annual Measurable Achievement Objectives (AMAO) under Title III, demonstrating satisfactory progress in learning English and attaining English proficiency.

Academic Performance Indicators for ELLs On 4 th grade National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), ELLs were: • • only 1/4 as likely to score proficient or above in Reading as their native English speaking peers and only 1/3 as likely to score proficient or above in Math as their native English-speaking peers.

Conceptual Framework: Reading

Guiding Principle #1 The crucial application for reading skills is to learn new concepts and develop new knowledge across a range of content areas. • Applies to all learners, not only ELLs; • Reading difficulties affect a learner’s knowledge base and vocabulary needed for text comprehension and independent writing in content areas.

Guiding Principle #2 To plan for effective instruction, educators must clearly understand the specific sources of difficulty or weaknesses in ELLs. Effective instruction requires careful assessment to: • • identify the specific source of difficulty and select the appropriate instructional approach or intervention.

Word Reading To master word reading, children must make a connection between sounds and letters. • Learners recognize systematic relationships between phonemes and letters from already mastered patterns in order to decode unfamiliar words. Like native English speakers, 5 -15 % of ELLs have difficulty acquiring sound-symbol correspondences and experience word reading difficulties. • ELLs with phonemic and phonological awareness difficulties typically also experience these difficulties in their native language. • ELLs with code-based difficulty must receive early systematic, explicit instruction.

Guiding Principle #3 ELLs often lack the necessary academic language for comprehending and analyzing text. • • Many ELLs who struggle academically have welldeveloped conversational English skills. Challenging academic language appears in higher grades’ reading materials, often long after ELLs stopped receiving special language support.

Academic Language: The Key to Academic Success Academic language: the vocabulary and semantics of a particular content-area literacy. • • Fundamental to academic success in all domains; A primary source of ELLs’ difficulties with academic content across grades and domains; Often still a challenge after students achieve proficiency on state language proficiency tests; Influences ELLs’ performance on all assessments.

Conversational vs. Academic Language Skills ELLs with good conversational skills often lack sufficient academic language skills to succeed in school. Research has shown that good conversational English skills may be accompanied by limited academic language skills in ELLs. The language of print differs from conversational language. • • Many elementary and middle school students—ELLs, reclassified ELLs, and native English speakers—in urban schools have academic vocabulary scores below the 20 th percentile. ELLs who are considered as no longer needing support instruction in English still lack skills that enable them to understand manipulate content vocabulary.

Components of Academic Language • Vocabulary used across academic disciplines: • Breadth – knowing the meanings of many words, • • including many words for the same, or related, concepts; Depth – knowing multiple meanings, both common and uncommon, for a given word; Understanding complex sentence structures and syntax typical of formal writing styles; Written vocabulary (distinct from oral vocabulary); Understanding the structure of argument, academic discourse, and expository texts (how to participate in a debate, or how to organize a lab report).

Components of Academic Language Other aspects of academic language relate to the text: • Organization of expository paragraphs; • Function of connectives (such as therefore and in contrast); • Wide range of vocabulary that appears far more often in text than in oral conversation; • Specific academic vocabulary—the words necessary to learn and talk about academic subjects (analyze, abstract, estimate, observe).

Why do students fail to acquire academic language? • Lack of exposure to appropriate books and to people who use academic language; • Lack of opportunities to learn and use academic language; • Lack of systematic, explicit instruction and sufficient and supportive feedback. (Scarcella, 2003)

What does it mean to know a word? Five Levels of Word Knowledge: • • • No knowledge; General sense; Narrow, context-bound knowledge; Enough knowledge to understand but not enough to recall and use appropriately; Rich, decontextualized knowledge of a word’s meaning, its relationship to other words, and metaphorical use. Students should leave high school with a working understanding of about 50, 000 words (Graves, 2006).

Guiding Principle #4 The great majority of ELLs experiencing reading difficulties struggle with skills related to fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension. Explicit instruction focused on these skills is critical.

Guiding Principle #5 When planning instruction and intervention, consider the function of the instruction: • • • Prevention—to avoid the onset of possible learning difficulties; Augmentation—to boost skills with supplemental instruction; Remediation— to correct existing deficiencies.

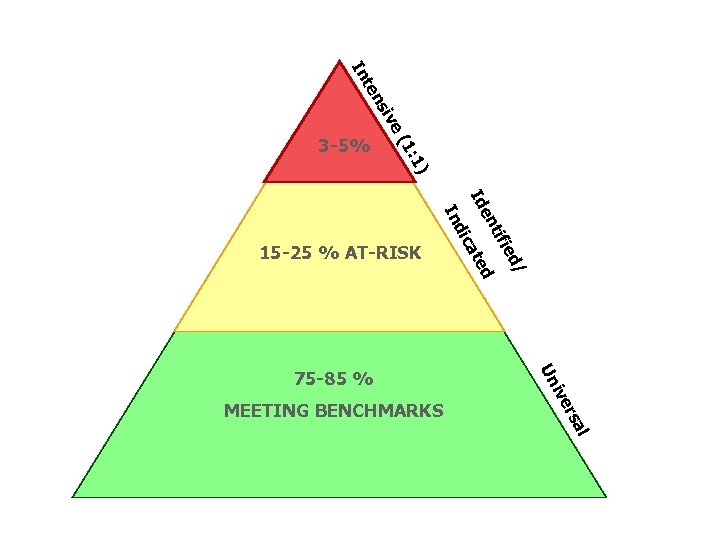

ive ns te In ) : 1 (1 3 -5% en Id l rsa ive MEETING BENCHMARKS Un 75 -85 % / ied tif d te ica d In 15 -25 % AT-RISK

Research-Based Recommendations for Reading Instruction and Intervention

Recommendation #1 ELLs need early, explicit, and intensive instruction in phonological awareness and phonics in order to build decoding skills.

Recommendation #1 (cont’d) • • • Do not wait until oral language proficiency is at the same level as native peers; start early. Carefully match the code-based intervention to the child’s source of difficulty. These skills are highly correlated (i. e. , above. 9) across alphabetic languages.

Support Word Reading Formats for explicit, intensive, and systematic instruction and intervention in phonological awareness and phonics for ELLs: • • • Class-wide instruction to prevent the majority of difficulties; Supplemental, small-group intervention for at-risk learners experiencing difficulties; and Intensive, 1: 1 remedial support for children with sustained difficulties.

Recommendation #2 K-12 classrooms across the nation must increase opportunities for ELLs to develop sophisticated vocabulary knowledge.

Effective Vocabulary Instruction • • Explicit—direct instruction of meaning along with word-learning strategies; Systematic—teaching words in a logical order of difficulty and relevance; Extensive—incorporating vocabulary across the curriculum; and Intensive—teaching multiple meanings of words, relations to other words, and different forms of words.

Effective Vocabulary Instruction Must occur in all classrooms and be consistent with grade-level instruction: • • In primary grades, read-aloud books and extended talk; In upper elementary grades, increased academic vocabulary through texts and word-learning strategies.

Recommendation #3 Reading instruction in K-12 classrooms must equip ELLs with strategies and knowledge to comprehend analyze challenging narrative and expository texts.

Strategies for Improving Comprehension • • • Small-group oral reading; Small group discussion, small-group work; Previewing to: • Generate interest in topic; • Build background knowledge; • Predicting, clarifying, and summarizing.

Effective Comprehension Instruction Kindergarten through 2 nd grade— Instruction should focus on books that are read aloud and discussed to: • • Give ELLs opportunities to develop and extend language through structured talk and Use modeling and explicit comprehension strategies (predicting, monitoring, and summarizing). Upper Elementary grades— Focus on teaching academic language and sentence structure. Middle and High School grades— Increase variety of more sophisticated content-are texts with an emphasis on strategies for comprehension and word learning.

Effective Comprehension Instruction Teach students to make predictions consciously before reading: • • Ask students to recall what they know about the type of text to be read; Scaffold and support discussions of predictions to help students gain understanding.

Effective Comprehension Instruction Teach students to monitor their understanding and ask questions during reading: • • Ask students questions during reading to cue them to recognize when their comprehension breaks down; Ask students to explain their processes for making meaning in order to increase opportunities to produce language.

Effective Reading Comprehension Teach students to summarize what they have read after the reading activity. Summarization requires the ability to synthesize information and to differentiate between more and less important information.

Recommendation #4 Instruction and intervention to promote ELLs’ reading fluency must focus on vocabulary development and increased exposure to print.

Small-group Oral Reading • • Students read aloud, stumble, get corrective feedback, keep going; Student practice reading with appropriate phrasing and expression, and are able to process for meaning and understanding; • Students discuss comprehension in a group.

Repeated Reading Interventions Empirically-based intervention where students practice reading instructional level expository or narrative passages orally. • Students re-read the passage until they: • • meet their oral reading fluency goal; read the passage with very few errors; and read with acceptable phrasing and expression. Since ELLs benefit from oral discussions: • • Pre-teach vocabulary words; and Lead discussion about words and meaning.

Repeated Reading Interventions Corrective feedback: • Immediate and positive feedback supports students who are not secure about pronunciation of difficult words; • Teachers may collect data on students’ miscues to provide individual support during small-group or one-on-one discussions.

Repeated Reading Interventions Discussions and questioning: • Maintains student engagement; • Promotes comprehension strategies and vocabulary development (students learn to monitor their understanding); • Provides opportunity to clarify doubts and explore different angles for meaning.

Repeated Reading Interventions • • • Provides increased, structured exposure to print that eventually becomes familiar; After reading a few times, students focus on correct pronunciation and on increasing their fluency; and Fosters increased engagement and motivation: • active learning activity with feedback, • opportunity to serve as models and to learn from others.

Recommendation #5 ELLs need significant opportunities to engage in structured, academic talk across all K-12 classrooms.

Recommendation #5 (cont’d) Academic language learning is facilitated through production and interaction and: • • • depends on the ability to practice and produce language; is optimized when connected to reading and writing activities; and needs to be modeled and taught explicitly.

Structured Academic Talk Reading aloud and shared readings provide: • practice and modeling in effective language use and appropriate expression; and • a platform for structured discussion, with scaffolds, to promote language development.

The SIOP Model Sheltered Instruction for Academic Achievement (Echevarria, Vogt, & Short, 2004) Making grade-level academic content (science, social studies, math) more accessible to ELLs and at the same time promoting their English language development.

Recommendation #6: Independent reading is only beneficial when: • it is structured and purposeful; and • there is a good reader-text match.

Independent Reading A good reader-text match is critical. • • Encountering too many unfamiliar words is not a useful way to build vocabulary or comprehension. A good match requires 90 -95% accuracy.

Planning Independent Reading • Are the reader’s ability and the text characteristics well-matched? Can the reader read the text with 90% accuracy? • Does the ratio of known to unknown words support vocabulary knowledge development during independent reading? • Is there a relationship between the content of texts for independent reading and the content and material being covered in the class? • Is there a plan for a follow-up activity or discussion after independent reading? • Do the teacher and the ELL share an understanding of the purpose or goal guiding that particular session of independent reading?

Conceptual Framework: Mathematics

Mathematics Proficiency: Guiding Principles Proficiency in mathematics is multi-faceted and draws on many skills, including reading and language skills. The misconception that math is a “universal language” is pervasive.

Conclusion These recommendations apply whether the instruction serves a preventative, augmentative, or remedial function, and in class-wide or small-group service delivery models and are based on a limited body of literature.

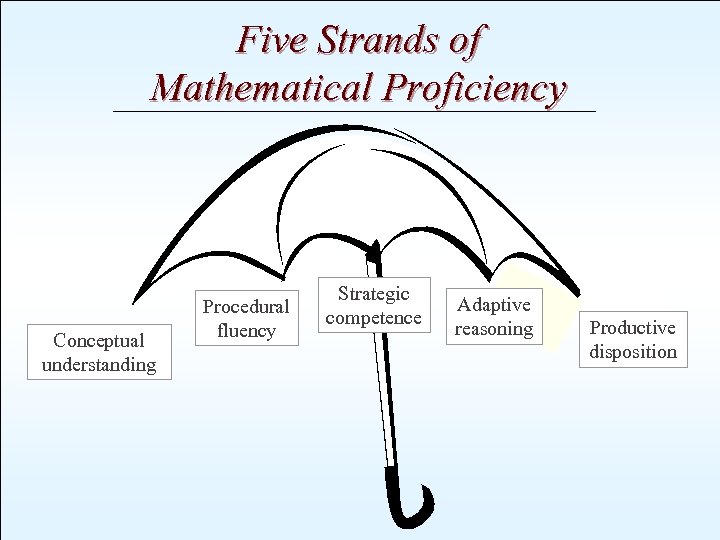

Five Strands of Mathematical Proficiency Conceptual understanding Procedural fluency Strategic competence Adaptive reasoning Productive disposition

1. Conceptual Understanding Comprehension of mathematical concepts, operations, and relations promotes an understanding of math concepts and, in turn, the retention of facts and methods. Indicator: A student is able to represent mathematical situations in different ways and for different purposes. Example: Drawing a picture or using concrete materials to show fractional quantities of different sizes for solving: ¾+½ =?

2. Procedural Fluency Students need to understanding procedures and know when and how to use them appropriately, with flexibility, accuracy, and efficiency. Indicator: Student can perform basic computations without depending on tables or other aids. Example: A good conceptual understanding of place value in the base-10 system that supports fluency in multi-digit computation: 1 345 + 965 0

3. Strategic Competence This encompasses the ability to formulate, represent, and solve mathematical problems. Students learn a variety of strategies and must select the appropriate strategy to solve a specific problem. Indicator: A student can select an efficient strategy to solve a problem and ignore irrelevant information. Example: The 5 th grade sold 24 cupcakes on Tuesday. This is 13 fewer cupcakes than Monday and 5 more than Wednesday. How many cupcakes did the 5 th grade sell for their 3 rd monthly bake sale?

4. Adaptive Reasoning Relates to the capacity of thinking logically about the relationships among concepts and situations. It involves logical thought, reflection, explanation, and justification. Indicator: A student’s adaptive reasoning enables him to explain and justify his work Example: Tom has 25¢. He wants to buy a ball that costs 39¢. If his dad helps him pay for it, then how much money would Tom owe his dad?

5. Productive Disposition Students are inclined to see mathematics as sensible, useful, and worthwhile experience. Indicator: A student believes that mathematics should make sense and perseveres in looking for the correct answer. Example: A positive classroom environment that provides challenging tasks along with effective instruction in order to promote confidence and avoid stereotypical threats.

Research-Based Recommendations for Mathematics Instruction and Intervention

Recommendation #1 ELLs need early, explicit, and intensive instruction and intervention in basic mathematics concepts and skill.

Recommendation #2 Academic language is as central to mathematics as it is to other academic areas. Academic language represents a significant source of difficulty for many ELLs who struggle with mathematics.

Recommendation #3 ELLs need academic language support to understand solve the word problems that are often used for mathematics assessment and instruction.

Conclusions These recommendations apply whether the instruction is preventative, augmentative, or remedial; delivered class-wide or in small groups; or based on a limited body of literature.

6ecb5ecd5ab0bad56b4fdfa429938e74.ppt