Blood diseases.pptx

- Количество слайдов: 25

BLOOD DISEASES 4 MPS Bozha Juliana Shumilo Toma

Blood is a bodily fluid in animals that delivers necessary substances such as nutrients and oxygen to the cells and transports metabolic waste products away from those same cells. In vertebrates, it is composed of blood cells suspended in blood plasma. Plasma, which constitutes 55% of blood fluid, is mostly water (92% by volume), and contains dissipated proteins, glucose, mineral ions, hormones, carbon dioxide , and blood cells themselves. Albumin is the main protein in plasma, and it functions to regulate the colloidal osmotic pressure of blood. The blood cells are mainly red blood cells (also called erythrocytes) and white blood cells, including leukocytes and platelets. The most abundant cells in blood are red blood cells. These contain hemoglobin, an iron-containing protein, which facilitates transportation of oxygen by reversibly binding to this respiratory gas and greatly increasing its solubility in blood. In contrast, carbon dioxide is almost entirely transported extracellularly dissolved in plasma as bicarbonate ion.

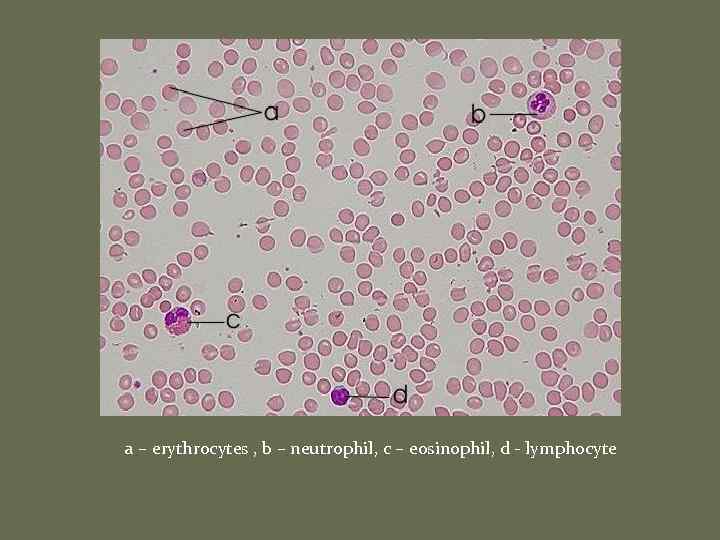

a – erythrocytes , b – neutrophil, c – eosinophil, d - lymphocyte

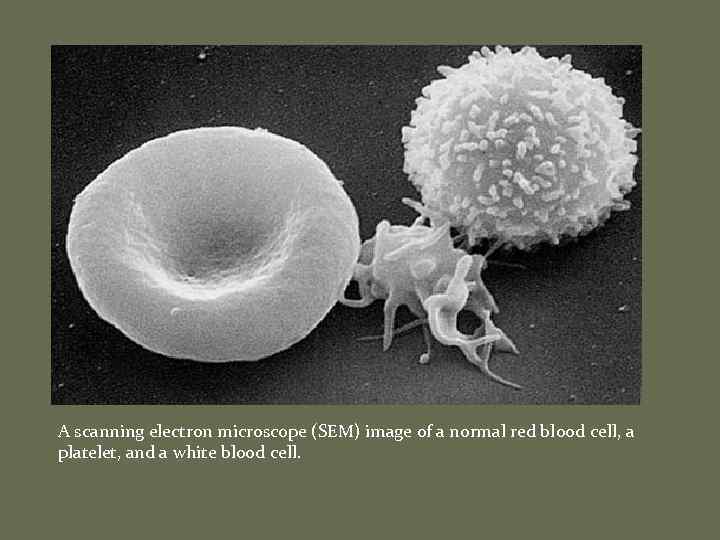

A scanning electron microscope (SEM) image of a normal red blood cell, a platelet, and a white blood cell.

Functions Blood performs many important functions within the body including: Supply of oxygen to tissues (bound to hemoglobin, which is carried in red cells) Supply of nutrients such as glucose, amino acids, and fatty acids (dissolved in the blood or bound to plasma proteins (e. g. , blood lipids)) Removal of waste such as carbon dioxide, urea, and lactic acid Immunological functions, including circulation of white blood cells, and detection of foreign material by antibodies Coagulation, which is one part of the body's self-repair mechanism (blood clotting after an open wound in order to stop bleeding) Messenger functions, including the transport of hormones and the signaling of tissue damage Regulation of body p. H Regulation of core body temperature Hydraulic functions

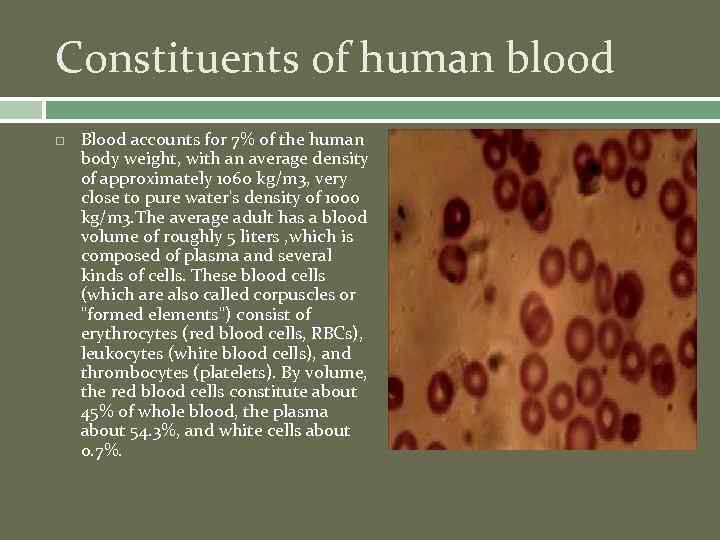

Constituents of human blood Blood accounts for 7% of the human body weight, with an average density of approximately 1060 kg/m 3, very close to pure water's density of 1000 kg/m 3. The average adult has a blood volume of roughly 5 liters , which is composed of plasma and several kinds of cells. These blood cells (which are also called corpuscles or "formed elements") consist of erythrocytes (red blood cells, RBCs), leukocytes (white blood cells), and thrombocytes (platelets). By volume, the red blood cells constitute about 45% of whole blood, the plasma about 54. 3%, and white cells about 0. 7%.

Hematological disorders Anemia Insufficient red cell mass (anemia) can be the result of bleeding, blood disorders like thalassemia, or nutritional deficiencies; and may require blood transfusion. Several countries have blood banks to fill the demand for transfusable blood. A person receiving a blood transfusion must have a blood type compatible with that of the donor. Sickle-cell anemia Disorders of cell proliferation Leukemia is a group of cancers of the blood-forming tissues and cells. Non-cancerous overproduction of red cells (polycythemia vera) or platelets (essential thrombocytosis) may be premalignant. Myelodysplastic syndromes involve ineffective production of one or more cell lines. Disorders of coagulation Hemophilia is a genetic illness that causes dysfunction in one of the blood's clotting mechanisms. This can allow otherwise inconsequential wounds to be life-threatening, but more commonly results in hemarthrosis, or bleeding into joint spaces, which can be crippling. Ineffective or insufficient platelets can also result in coagulopathy (bleeding disorders). Hypercoagulable state (thrombophilia) results from defects in regulation of platelet or clotting factor function, and can cause thrombosis. Infectious disorders of blood Blood is an important vector of infection. HIV, the virus that causes AIDS, is transmitted through contact with blood, semen or other body secretions of an infected person. Hepatitis B and C are transmitted primarily through blood contact. Owing to blood-borne infections, bloodstained objects are treated as a biohazard. Bacterial infection of the blood is bacteremia or sepsis. Viral Infection is viremia. Malaria and trypanosomiasis are blood-borne parasitic infections.

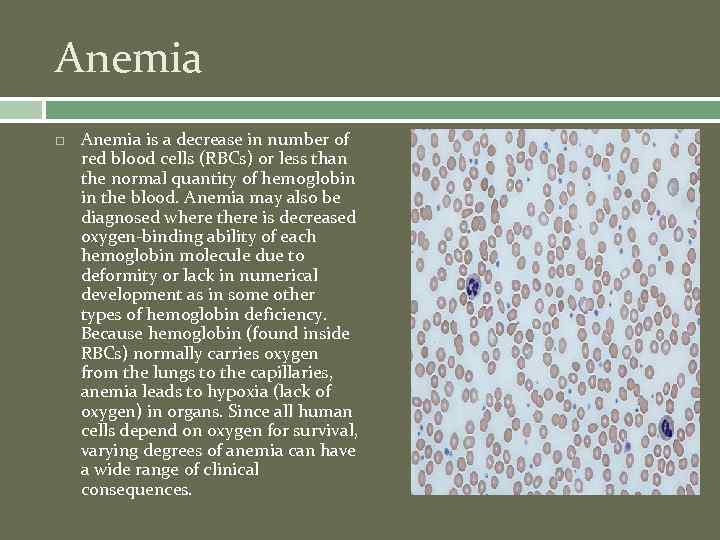

Anemia is a decrease in number of red blood cells (RBCs) or less than the normal quantity of hemoglobin in the blood. Anemia may also be diagnosed where there is decreased oxygen-binding ability of each hemoglobin molecule due to deformity or lack in numerical development as in some other types of hemoglobin deficiency. Because hemoglobin (found inside RBCs) normally carries oxygen from the lungs to the capillaries, anemia leads to hypoxia (lack of oxygen) in organs. Since all human cells depend on oxygen for survival, varying degrees of anemia can have a wide range of clinical consequences.

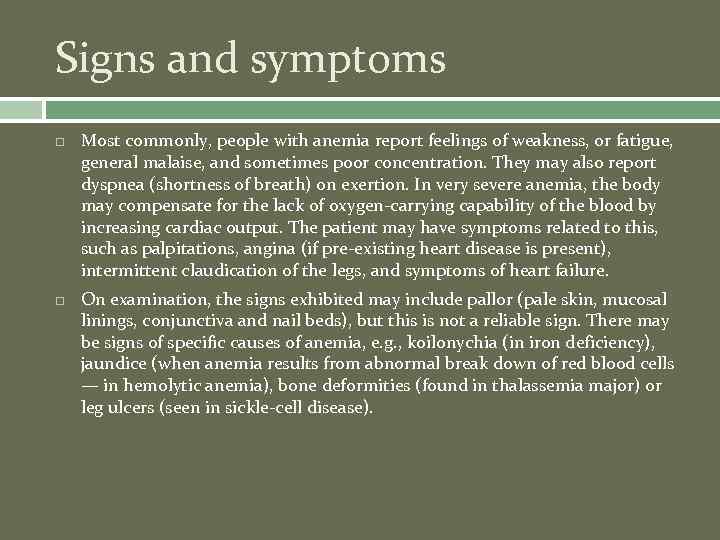

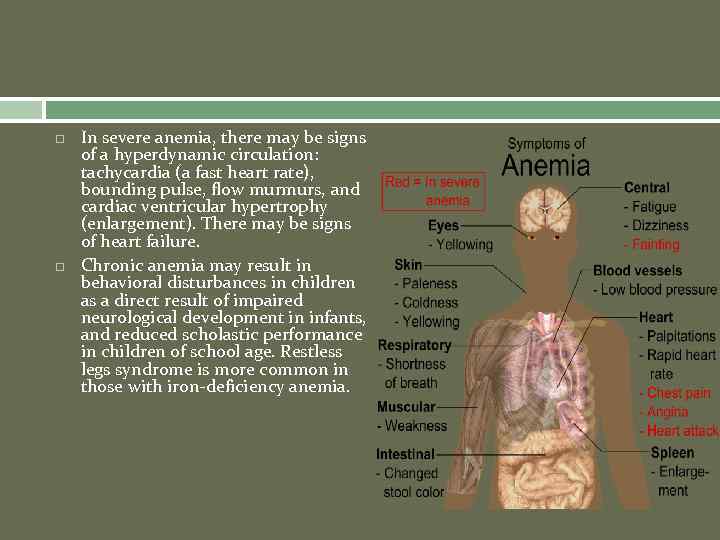

Signs and symptoms Most commonly, people with anemia report feelings of weakness, or fatigue, general malaise, and sometimes poor concentration. They may also report dyspnea (shortness of breath) on exertion. In very severe anemia, the body may compensate for the lack of oxygen-carrying capability of the blood by increasing cardiac output. The patient may have symptoms related to this, such as palpitations, angina (if pre-existing heart disease is present), intermittent claudication of the legs, and symptoms of heart failure. On examination, the signs exhibited may include pallor (pale skin, mucosal linings, conjunctiva and nail beds), but this is not a reliable sign. There may be signs of specific causes of anemia, e. g. , koilonychia (in iron deficiency), jaundice (when anemia results from abnormal break down of red blood cells — in hemolytic anemia), bone deformities (found in thalassemia major) or leg ulcers (seen in sickle-cell disease).

In severe anemia, there may be signs of a hyperdynamic circulation: tachycardia (a fast heart rate), bounding pulse, flow murmurs, and cardiac ventricular hypertrophy (enlargement). There may be signs of heart failure. Chronic anemia may result in behavioral disturbances in children as a direct result of impaired neurological development in infants, and reduced scholastic performance in children of school age. Restless legs syndrome is more common in those with iron-deficiency anemia.

Classification Red blood cell size In the morphological approach, anemia is classified by the size of red blood cells; this is either done automatically or on microscopic examination of a peripheral blood smear. The size is reflected in the mean corpuscular volume (MCV). If the cells are smaller than normal , the anemia is said to be microcytic; if they are normal size , normocytic; and if they are larger than normal , the anemia is classified as macrocytic. This scheme quickly exposes some of the most common causes of anemia; for instance, a microcytic anemia is often the result of iron deficiency. In clinical workup, the MCV will be one of the first pieces of information available, so even among clinicians who consider the "kinetic" approach more useful philosophically, morphology will remain an important element of classification and diagnosis. Limitations of MCV include cases where the underlying cause is due to a combination of factors - such as iron deficiency (a cause of microcytosis) and vitamin B 12 deficiency (a cause of macrocytosis) where the net result can be normocytic cells.

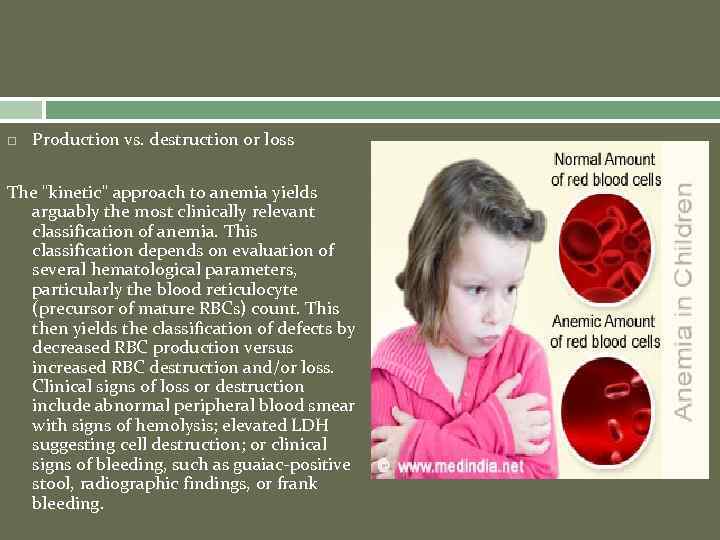

Production vs. destruction or loss The "kinetic" approach to anemia yields arguably the most clinically relevant classification of anemia. This classification depends on evaluation of several hematological parameters, particularly the blood reticulocyte (precursor of mature RBCs) count. This then yields the classification of defects by decreased RBC production versus increased RBC destruction and/or loss. Clinical signs of loss or destruction include abnormal peripheral blood smear with signs of hemolysis; elevated LDH suggesting cell destruction; or clinical signs of bleeding, such as guaiac-positive stool, radiographic findings, or frank bleeding.

![Heinz body anemia[edit] Heinz bodies form in the cytoplasm of RBCs and appear Heinz body anemia[edit] Heinz bodies form in the cytoplasm of RBCs and appear](https://present5.com/presentation/50307107_243425580/image-16.jpg)

Heinz body anemia[edit] Heinz bodies form in the cytoplasm of RBCs and appear as small dark dots under the microscope. Heinz body anemia has many causes, and some forms can be drug-induced. It is triggered in cats by eating onions[14] or acetaminophen (paracetamol). It can be triggered in dogs by ingesting onions or zinc, and in horses by ingesting dry red maple leaves. Hyperanemia is a severe form of anemia, in which the hematocrit is below 10%. Refractory anemia, an anemia which does not respond to treatment, is often secondary to myelodysplastic syndromes. Iron deficiency anemia may also be refractory as a clinical manifestation of gastrointestinal problems which disrupt iron absorption or cause occult bleeding.

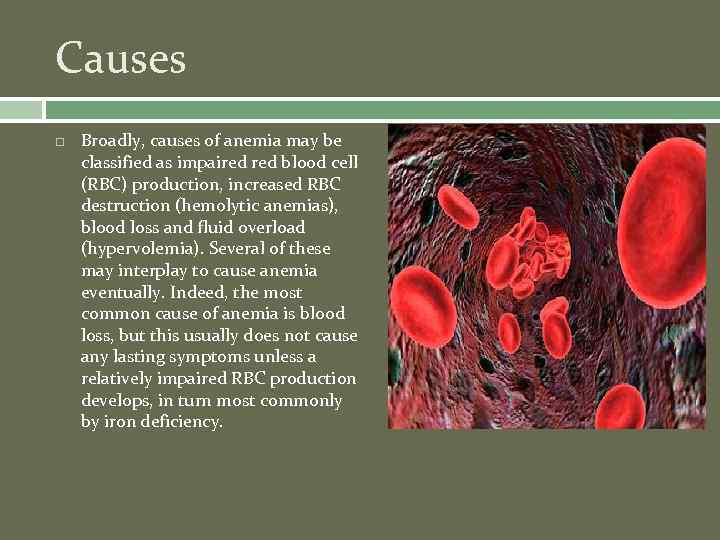

Causes Broadly, causes of anemia may be classified as impaired blood cell (RBC) production, increased RBC destruction (hemolytic anemias), blood loss and fluid overload (hypervolemia). Several of these may interplay to cause anemia eventually. Indeed, the most common cause of anemia is blood loss, but this usually does not cause any lasting symptoms unless a relatively impaired RBC production develops, in turn most commonly by iron deficiency.

![Impaired production Disturbance of proliferation and differentiation of stem cells Pure red cell aplasia[19] Impaired production Disturbance of proliferation and differentiation of stem cells Pure red cell aplasia[19]](https://present5.com/presentation/50307107_243425580/image-18.jpg)

Impaired production Disturbance of proliferation and differentiation of stem cells Pure red cell aplasia[19] Aplastic anemia[19] affects all kinds of blood cells. Fanconi anemia is a hereditary disorder or defect featuring aplastic anemia and various other abnormalities. Anemia of renal failure[19] by insufficient erythropoietin production Anemia of endocrine disorders Disturbance of proliferation and maturation of erythroblasts Pernicious anemia[19] is a form of megaloblastic anemia due to vitamin B 12 deficiency dependent on impaired absorption of vitamin B 12. Lack of dietary B 12 causes non-pernicious megaloblastic anemia Anemia of folic acid deficiency, [19] as with vitamin B 12, causes megaloblastic anemia Anemia of prematurity, by diminished erythropoietin response to declining hematocrit levels, combined with blood loss from laboratory testing, generally occurs in premature infants at two to six weeks of age.

![Iron deficiency anemia, resulting in deficient heme synthesis[19] thalassemias, causing deficient globin synthesis[19] Iron deficiency anemia, resulting in deficient heme synthesis[19] thalassemias, causing deficient globin synthesis[19]](https://present5.com/presentation/50307107_243425580/image-19.jpg)

Iron deficiency anemia, resulting in deficient heme synthesis[19] thalassemias, causing deficient globin synthesis[19] Congenital dyserythropoietic anemias, causing ineffective erythropoiesis Anemia of renal failure[19] (also causing stem cell dysfunction) Other mechanisms of impaired RBC production Myelophthisic anemia[19] or myelophthisis is a severe type of anemia resulting from the replacement of bone marrow by other materials, such as malignant tumors or granulomas. Myelodysplastic syndrome[19] anemia of chronic inflammation

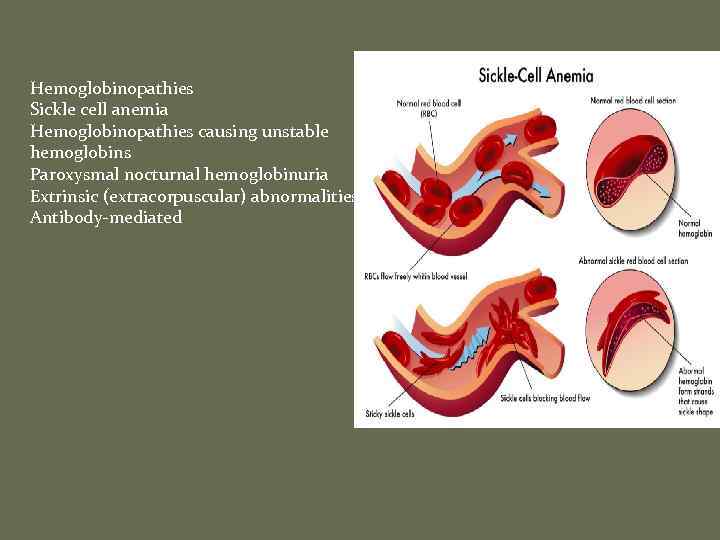

Increased destruction Anemias of increased red blood cell destruction are generally classified as hemolytic anemias. These are generally featuring jaundice and elevated lactate dehydrogenase levels. Intrinsic (intracorpuscular) abnormalities cause premature destruction. All of these, except paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria, are hereditary genetic disorders. Hereditary spherocytosis is a hereditary defect that results in defects in the RBC cell membrane, causing the erythrocytes to be sequestered and destroyed by the spleen. Hereditary elliptocytosis is another defect in membrane skeleton proteins. Abetalipoproteinemia, causing defects in membrane lipids Enzyme deficiencies Pyruvate kinase and hexokinase deficiencies, causing defect glycolysis Glucose-6 -phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency and glutathione synthetase deficiency, causing increased oxidative stress

Hemoglobinopathies Sickle cell anemia Hemoglobinopathies causing unstable hemoglobins Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria Extrinsic (extracorpuscular) abnormalities Antibody-mediated

Warm autoimmune hemolytic anemia is caused by autoimmune attack against red blood cells, primarily by Ig. G. It is the most common of the autoimmune hemolytic diseases. It can be idiopathic, that is, without any known cause, drug-associated or secondary to another disease such as systemic lupus erythematosus, or a malignancy, such as chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cold agglutinin hemolytic anemia is primarily mediated by Ig. M. It can be idiopathic or result from an underlying condition. Rh disease, one of the causes of hemolytic disease of the newborn Transfusion reaction to blood transfusions Mechanical trauma to red cells Microangiopathic hemolytic anemias, including thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura and disseminated intravascular coagulation Infections, including malaria Heart surgery Haemodialysis

Blood loss Anemia of prematurity from frequent blood sampling for laboratory testing, combined with insufficient RBC production Trauma[19] or surgery, causing acute blood loss Gastrointestinal tract lesions, causing either acute bleeds (e. g. variceal lesions, peptic ulcers or chronic blood loss (e. g. angiodysplasia) Gynecologic disturbances, also generally causing chronic blood loss From menstruation, mostly among young women or older women who have fibroids Fluid overload (hypervolemia) causes decreased hemoglobin concentration and apparent anemia: General causes of hypervolemia include excessive sodium or fluid intake, sodium or water retention and fluid shift into the intravascular space. Anemia of pregnancy is induced by blood volume expansion experienced in pregnancy.

Treatments for anemia depend on severity and cause. Oral iron Iron deficiency from nutritional causes is rare in men and postmenopausal women. The diagnosis of iron deficiency mandates a search for potential sources of loss, such as gastrointestinal bleeding from ulcers or colon cancer. Mild to moderate iron-deficiency anemia is treated by oral iron supplementation with ferrous sulfate, ferrous fumarate, or ferrous gluconate. When taking iron supplements, stomach upset and/or darkening of the feces are commonly experienced. The stomach upset can be alleviated by taking the iron with food; however, this decreases the amount of iron absorbed. Vitamin C aids in the body's ability to absorb iron, so taking oral iron supplements with orange juice is of benefit. In anemias of chronic disease, associated with chemotherapy, or associated with renal disease, some clinicians prescribe recombinant erythropoietin or epoetin alfa, to stimulate RBC production, although since there is also concurrent iron deficiency and inflammation present, parenteral iron is advised to be taken concurrently.

Parenteral iron In cases where oral iron has either proven ineffective, would be too slow (for example, preoperatively) or where absorption is impeded (for example in cases of inflammation), parenteral iron can be used. The body can absorb up to 6 mg iron daily from the gastrointestinal tract. In many cases the patient has a deficit of over 1, 000 mg of iron which would require several months to replace. This can be given concurrently with erythropoietin to ensure sufficient iron for increased rates of erythropoiesis. Blood transfusions Doctors attempt to avoid blood transfusion in general, since multiple lines of evidence point to increased adverse patient clinical outcomes with more intensive transfusion strategies. The physiological principle that reduction of oxygen delivery associated with anemia leads to adverse clinical outcomes is balanced by the finding that transfusion does not necessarily mitigate these adverse clinical outcomes. Blood does have risks associated, such as disease transmission and host incompatibility, even in cases where crossmatching was correctly undertaken. Transfusion of the stable but anemic hospitalized patient has been the subject of numerous clinical trials. [citation needed] Four randomized, controlled clinical trials have been conducted to evaluate aggressive versus conservative transfusion strategies in critically ill patients. All four of these studies failed to find a benefit with more aggressive transfusion strategies. And more recent studies have shown that transfusing patients worsens outcome. This is further substantiated by guidelines increasingly advising that transfusions should only be undertaken in cases of cardiovascular instability In addition, at least two retrospective studies have shown increases in adverse clinical outcomes in critically ill patients who underwent more aggressive transfusion strategies.

Blood diseases.pptx