3010e6474ddfb8acf4fab8ce2076cae0.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 162

bio-modeling

c o u r s e k k k k l a y o u t introduction molecular biology biotechnology bio. MEMS bioinformatics bio-modeling cells and e-cells transcription and regulation cell communication neural networks dna computing fractals and patterns the birds and the bees …. . and ants

i n t r o d u c t i o n

fa r a n d a w a y i n t h e p a s t k Newton’s equations of motions (17 th -18 th century) Molecular dynamics (MD) k Boltzmann’s statistics (19 th century) Monte Carlo (MC) k Schrödinger/Heisenberg’s quantum mechanics (20 th century)

birth of simulation in chemistry k 1950’s: do it by hand (or mechanical calculator)! k Tried to solve Newton’s equation of motion for small systems (e. g. three-atom system) k Didn’t take very long before they saw computers k 1970’s: Age of punchcards k 1980’s: Better IO devices Workstations dominated as research platforms

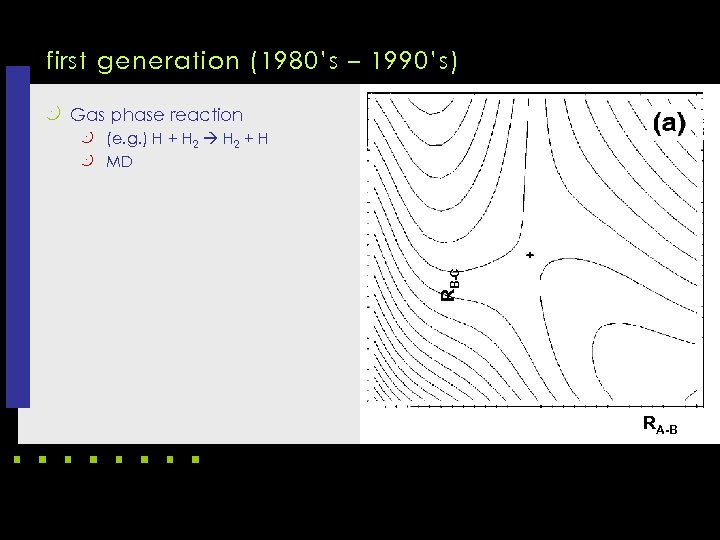

first generation (1980’s – 1990’s) k Gas phase reaction k (e. g. ) H + H 2 + H RB-C k MD RA-B

first generation (1980’s – 1990’s) k Liquid simulation k (e. g. ) Lennard-Jones Fluid k MD/MC

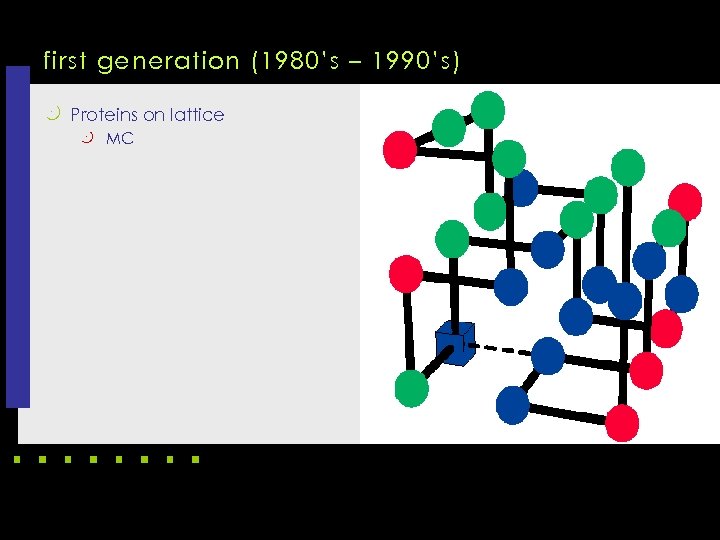

first generation (1980’s – 1990’s) k Proteins on lattice k MC

first generation (1980’s – 1990’s) k Quantum mechanical structure calculation (semi-empirical, ab initio, …)

revolution (~ 1995) k Workstation-like PCs k 100 hr Cray time 64 MB / 150 MHz Pentium k “Cheap and fast” k Impacts k Two directions 1) More accurate methods 2) Larger system k Start of bio-simulations

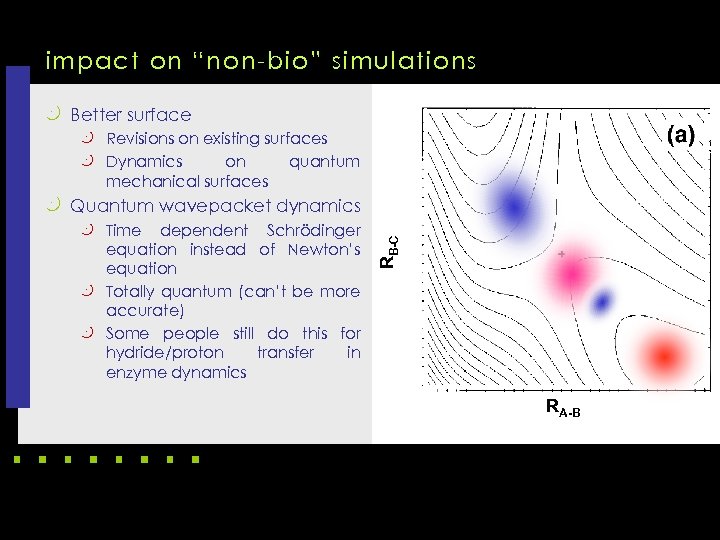

impact on “non-bio” simulations k Better surface k Revisions on existing surfaces k Dynamics on mechanical surfaces quantum k Time dependent Schrödinger equation instead of Newton’s equation k Totally quantum (can’t be more accurate) k Some people still do this for hydride/proton transfer in enzyme dynamics RB-C k Quantum wavepacket dynamics RA-B

Impacts on bio-simulations k Proteins got free from the lattice! Off lattice model (still, each residue as a bead) k United atom approach (e. g. CH 3 one atom) k All atom approach k k With water (explicit solvent) k Without water (implicit solvent) k What to look at? Kinetics: dynamic characteristics (e. g. folding simulation) k Thermodynamics: equilibrium characteristics (e. g. binding affinity of protein & drug) k

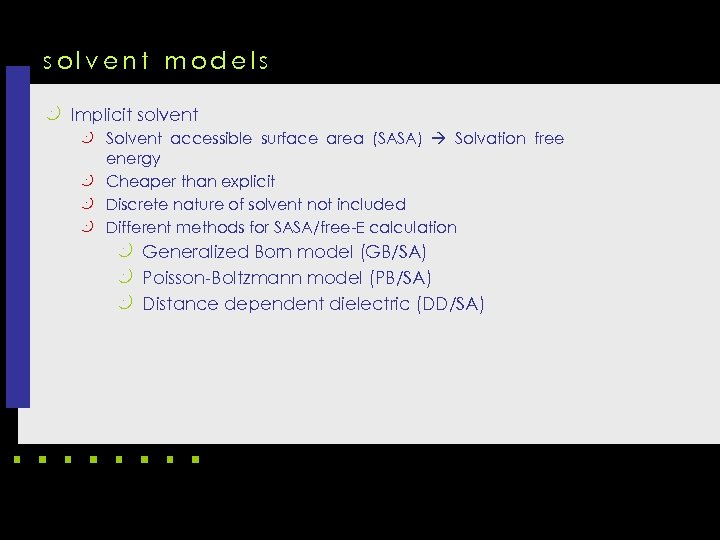

solvent models k Implicit solvent k Solvent accessible surface area (SASA) Solvation free energy k Cheaper than explicit k Discrete nature of solvent not included k Different methods for SASA/free-E calculation k Generalized Born model (GB/SA) k Poisson-Boltzmann model (PB/SA) k Distance dependent dielectric (DD/SA)

solvent models Explicit solvent k Water as individual molecules k Expensive calculation k Periodic boundary conditions usually necessary k Rigid/flexible, polarizable/non-polarizable k SPC, TIP 3 P, TIP 4 P, TIP 5 P, …

im p a c t s o n b i o - s i m u l a t i o n s k Proteins got free from the lattice! k Off lattice model (each residue as a bead) k United atom approach (e. g. CH 3 one atom) k All atom approach k With water (explicit solvent) k Without water (implicit solvent) k What to look at? k Kinetics: dynamic characteristics (e. g. folding simulation) k Thermodynamics: equilibrium characteristics (e. g. binding affinity of protein & drug) k Remember, proteins are still big!

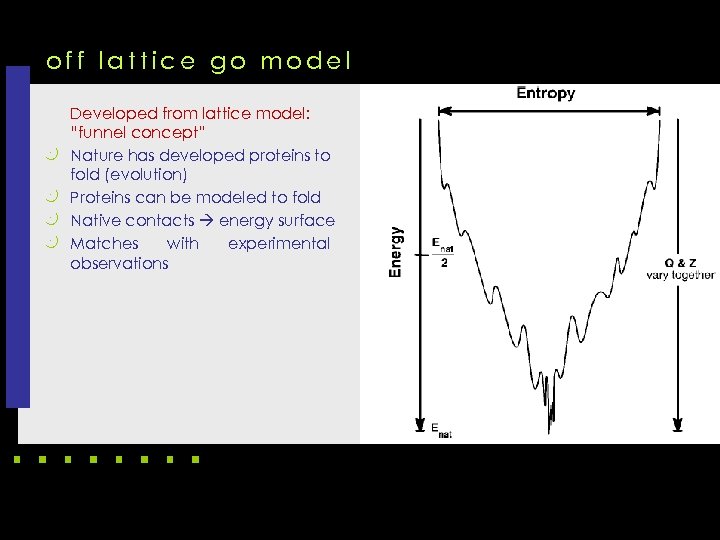

off lattice go model k k Developed from lattice model: “funnel concept” Nature has developed proteins to fold (evolution) Proteins can be modeled to fold Native contacts energy surface Matches with experimental observations

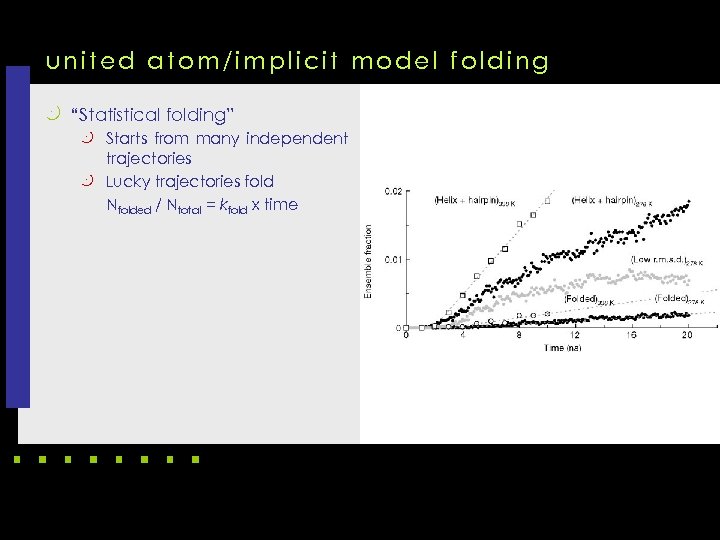

united atom/implicit model folding k “Statistical folding” k Starts from many independent trajectories k Lucky trajectories fold Nfolded / Ntotal = kfold x time

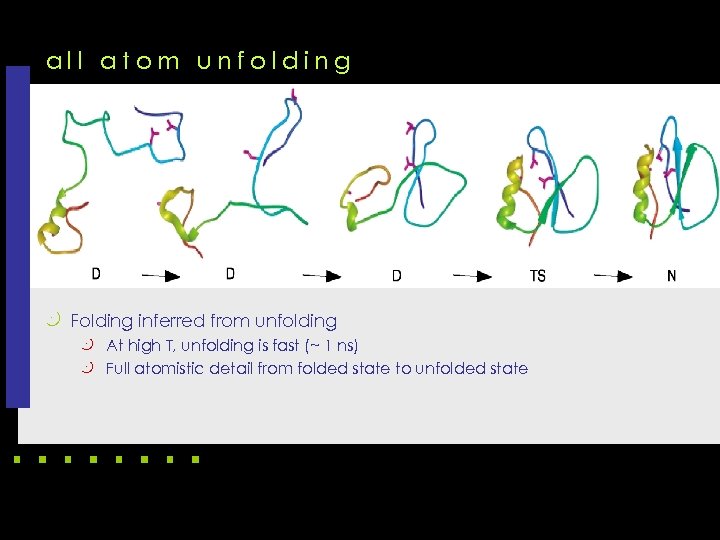

all atom unfolding k Folding inferred from unfolding k At high T, unfolding is fast (~ 1 ns) k Full atomistic detail from folded state to unfolded state

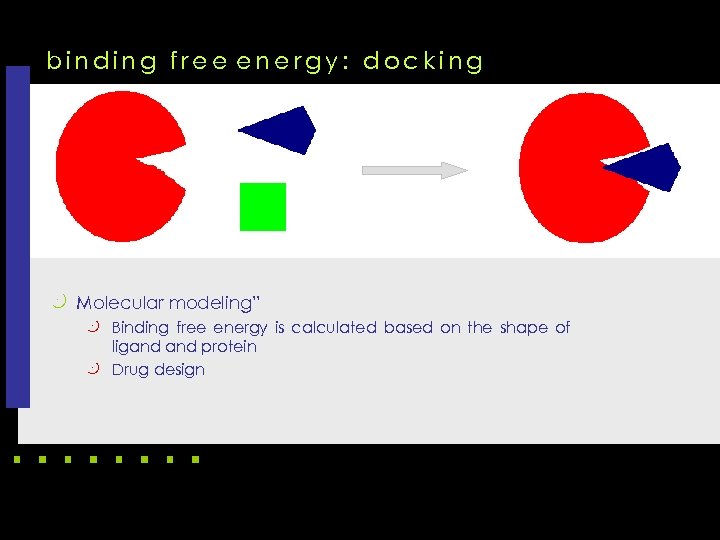

binding free energy: docking k Molecular modeling” k Binding free energy is calculated based on the shape of ligand protein k Drug design

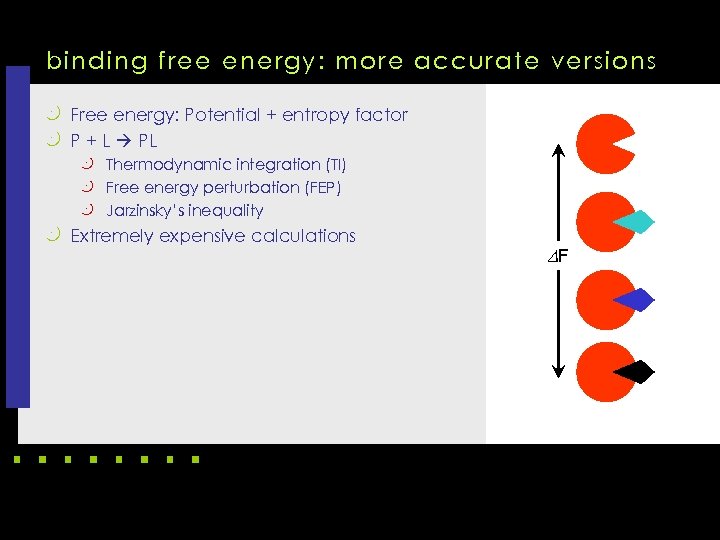

binding free energy: more accurate versions k Free energy: Potential + entropy factor k P + L PL k Thermodynamic integration (TI) k Free energy perturbation (FEP) k Jarzinsky’s inequality k Extremely expensive calculations DF

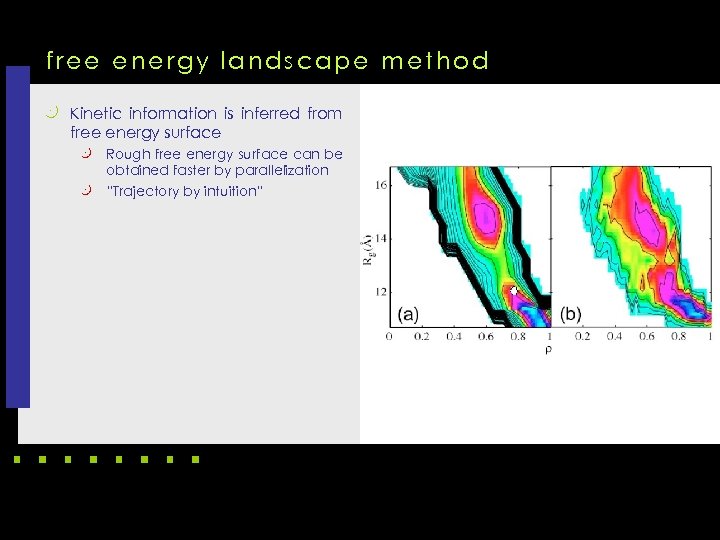

free energy landscape method k Kinetic information is inferred from free energy surface Rough free energy surface can be obtained faster by parallelization k “Trajectory by intuition” k

current limitation k Accuracies of models k Force field k Solvent models k Speed k For small proteins (<50 amino acids): 1 ns ~ 1 day k Biologically relevant event timescale > 1 ms k Size k Many proteins are not just large: they are huge!

responses to the challenges k Accuracy: Blend with quantum mechanical calculation k QM/MM, QM-trajectory method (e. g. CPMD) k Speed k E. g. Compute on video card k Size k E. g. Umbrella sampling

computational biology Biological Systems are complex, thus, a combination of experimental and computational approaches are needed.

computational biology k Computational Biology Bioinformatics k More than sequences, database searches, statistics or image analysis. k A part of Computational Science k Using mathematical modeling, simulation and visualization k Complementing theory and experiment

simplest chemical reaction A B k irreversible, one-molecule reaction k examples: all sorts of decay processes, e. g. radioactive, fluorescence, activated receptor returning to inactive state k any metabolic pathway can be described by a combination of processes of this type (including reversible reactions and, in some respects, multimolecule reactions)

simplest chemical reaction A B various levels of description: k homogeneous system, large numbers of molecules = ordinary differential equations, kinetics k small numbers of molecules = probabilistic equations, stochastics k spatial heterogeneity = partial differential equations, diffusion k small number of heterogeneously distributed molecules = single-molecule tracking (e. g. cytoskeleton modelling)

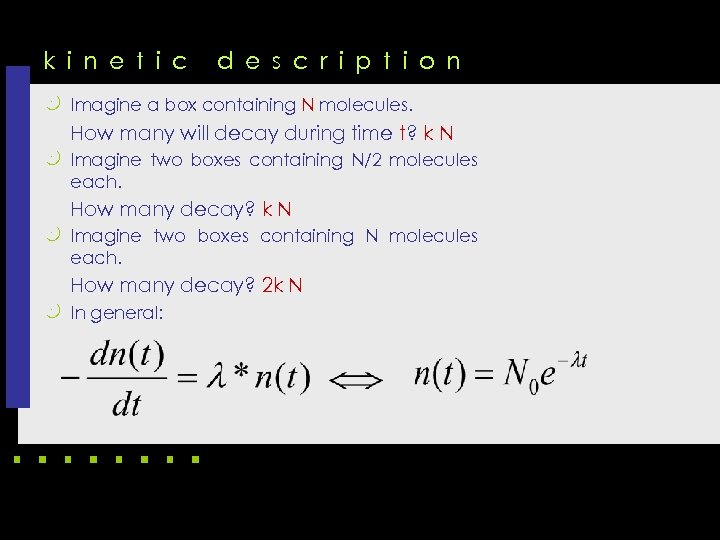

k i n e t i c d e s c r i p t i o n k Imagine a box containing N molecules. How many will decay during time t? k N k Imagine two boxes containing N/2 molecules each. How many decay? k N k Imagine two boxes containing N molecules each. How many decay? 2 k N k In general: differential equation (ordinary, linear, first-order) exact solution (in more complex cases replaced by a numerical approximation)

what is bio-modeling?

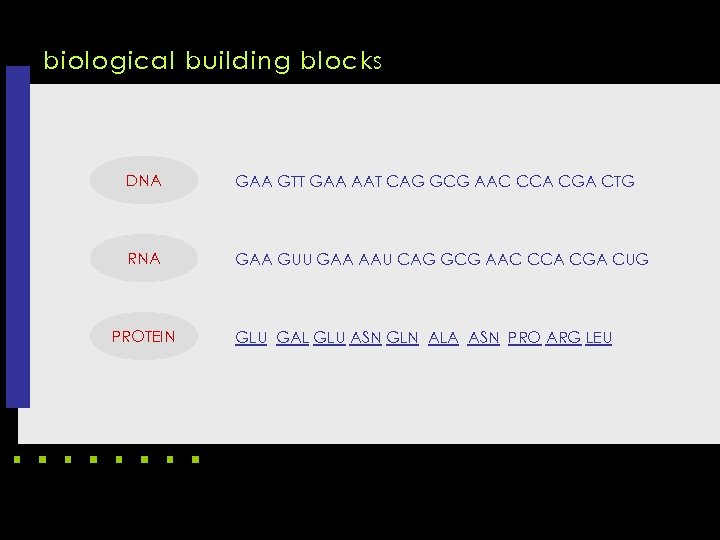

biological building blocks DNA GAA GTT GAA AAT CAG GCG AAC CCA CGA CTG RNA GAA GUU GAA AAU CAG GCG AAC CCA CGA CUG PROTEIN GLU GAL GLU ASN GLN ALA ASN PRO ARG LEU

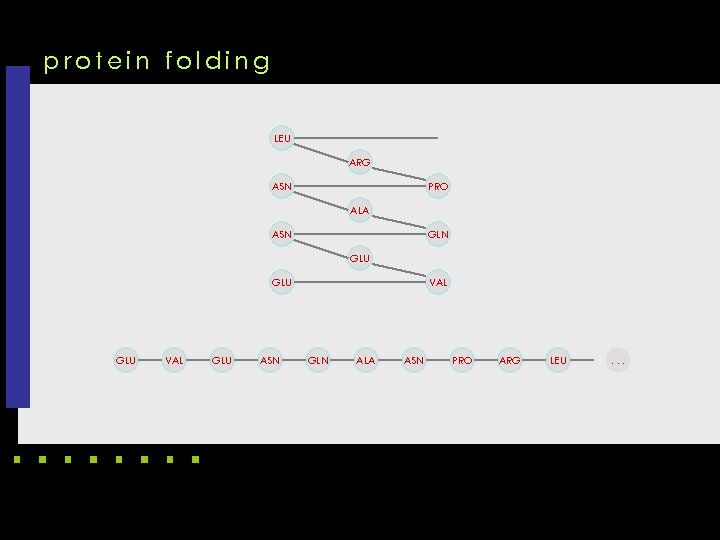

protein folding LEU ARG ASN PRO ALA ASN GLU GLU VAL GLU ASN VAL GLN ALA ASN PRO ARG LEU . . .

some fundamental questions k Question #1: Given a protein or DNA molecule, what is the geometric structure of the molecule? k Question #2: Why and how protein folds to a unique three-dimensional structure? k Question #3: Given a set of distances between pairs of atoms, how can we determine the coordinates of the atoms? k Question #4: Given the magnitudes of the structure factors of a protein, how can we determine the phases of the structure factors? k Question #5: Given two proteins, how can we compare their geometric structures? k Question #6: k …

methods for structure prediction and determination k k k k Protein X-ray Crystallography Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Potential Energy Minimization Molecular Dynamics Simulation Homology Modeling Fold Recognition Inverse Protein Folding

empirical structure determination k Two major experimental methods for determining protein structure k X-ray Crystallography k Requires growing a crystal of the protein (impossible for some, never easy) k Diffraction pattern can be inverse-Fourier transformed to characterize electron densities (Phase problem) k Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) imaging k Provides distance constraints, but can be hard to find a corresponding structure k Works only for relatively small proteins

X-ray crystallography k X-rays, since wavelength is near the distance between bonded carbon atoms k Maps electron density, not atoms directly k Crystal to get a lot of spatially aligned atoms k Have to invert Fourier transform to get structure, but only have amplitudes, not phases

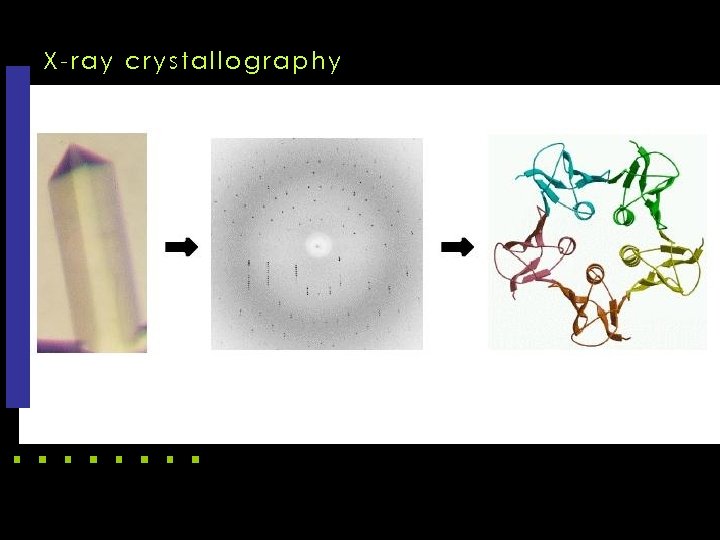

X-ray crystallography

X-ray crystallography computing k In X-ray crystallography, protein first needs to be purified and crystallized, which may take months or years to complete, if not failed. k After that, the protein crystal is put into an X-ray equipment to make an X-ray diffraction image. The diffraction image can be used to determine threedimensional structure of the protein. k The process is time consuming, and some proteins cannot even be crystallized.

X-ray crystallography computing k A mathematical problem, called the phase problem, needs to be solved before every crystal structure can be fully determined from the diffraction data. k 80% of the structures in PDB Data Bank were determined by using X-ray crystallography.

NMR structure determination k The NMR approach is based on the fact that nuclei spin and generate magnetic fields. When two nuclei are close their spins interact. The intensity of the interaction depends on the distance between the nuclei. Therefore, the distances between certain pairs of atoms can be estimated by measuring the intensities of the nuclei spin couplings. k The distance data obtained from the NMR experiment can be used to deduce the structural information for the molecule. One way of achieving such a goal is based on molecular distance geometry.

NMR structure determination k Not all distances between pairs of atoms can be detected. In practice, only lower and upper bounds for the distances can be obtained also. k Structure can be determined by solving a distance geometry problem with the distance data from the NMR experiments. k 15% of the structures in PDB Data Bank were determined by using NMR spectroscopy.

potential energy minimization Hypothesis Protein native structure has the lowest or almost lowest potential energy. It can therefore be located at the global energy minimum of protein.

potential energy minimization k A reasonably accurate potential energy function needs to be constructed. k Given such a function, a local minimum is easy to find, but a global one is hard, especially if the function has many local minima. No completely satisfactory algorithm has been developed yet for minimizing proteins. k Potential energy minimization has been used successfully for structure refinement though.

molecular dynamics Folding can be simulated by following the movement of the atoms in protein according to Newton’s second law of motion.

molecular dynamics k The step size has to be small in femto-second to achieve accuracy. k Current computing technology can make only picoseconds to microseconds of simulation, while protein folding may take seconds or even longer time. k Molecular dynamics simulation has been used successfully for the study of other types of dynamical behavior of protein.

li m i t a t i o n s o f M D s i m u l a t i o n s k Full atomic representation noise difficulty in discerning the dominant mechanisms of motion need for methods for filtering out the noise, such as Essential Dynamics. k Empirical force fields limited by the accuracy of the potentials. k Time steps constrained by fastest motion (vibrations in bond lengths occur in the femtoseconds (fs) time range and necessitate the use of timesteps of 1 -5 fs). k Inefficient sampling of the complete space of conformations. k Limited to small proteins (100 s of residues) and/or short times (subnanoseconds).

sequence structure alignment Homology Modeling Sequence to Sequence Fold Recognition Structure to Sequence Known Sequences / Structures Sequence Structure Alignment Inverse Protein Folding Sequence to Structure Ranking Sequences / Structures

sequence structure alignment k Scoring functions may not be able to distinguish between good and bad matches. k Computing the best alignment is NP-hard in general when gaps are allowed. k The results are not accurate and have only certain level of confidence.

what is biomolecular modeling? k Application of computational models to understand the structure, dynamics, and thermodynamics of biological molecules k The models must be tailored to the question at hand: Schrödinger equation is not the answer to everything! Reductionist view bound to fail! k This implies that biomolecular modeling must be both multidisciplinary and multiscale

an odd remark "Every attempt to employ mathematical methods in the study of chemical questions must be considered profoundly irrational and contrary to the spirit in chemistry. If mathematical analysis should ever hold a prominent place in chemistry - an aberration which is happily almost impossible - it would occasion a rapid and widespread degeneration of that science. " A. Comte (1830)

a Nobel remark 1992 Nobel Prize in Chemistry Rudolph Marcus (Theory of Electron Transfer) 1998 Nobel Prize in Chemistry John Pople (ab initio) Walter Kohn (DFT-density functional theory)

g rowth of biological databases 3 D structures growth http: //www. rcsb. org/pdb/holdings. html

molecular modeling

structure-property relationships “First Principles” • H = E (QM) • - d. E / dri = mi d 2 ri / dt 2(MD) • Folding simulations Molecular Model Mathematical model Predictions: • Structure • Properties Empirical Correlations {property} = k {Descriptors} ^ • E = Ebonded + Enonbonded (MM) ( ) • log 1 C = - k p 2 + k 'p + rs + k '' (QSAR) • Fold recognition

molecular geometry and molecular properties k Conformational energy (potential energy) k Evalence = Ebond + Eangle + Etorsion + Eoop k bond stretching(Ebond) k valence angle bending (Eangle) k dihedral angle torsion (Etorsion) k out-of-plane interactions (Eoop) k Enonbond = Evd. W + ECoulomb + Ehbond k van der Waals (Evd. W) k electrostatic (ECoulomb) k hydrogen bond (Ehbond) F. Melani Molecular Modeling in Chimica Farmaceutica

molecular geometry and molecular properties Force-field Σ Force fields conformational energy (potential energy) definition by k atoms type k atomic charges k constant of force, equlibrium values k energy equations F. Melani Molecular Modeling in Chimica Farmaceutica

molecular geometry and molecular properties standard force field F. Melani Molecular Modeling in Chimica Farmaceutica

molecular geometry and molecular properties F. Melani Molecular Modeling in Chimica Farmaceutica

molecular geometry and molecular properties bond-stretching ( Ebond ) Morse quadratic quartic Morse quadratic valence angle bending (Eangle ) quadratic dihedral angle torsion ( Etorsion ) F. Melani Molecular Modeling in Chimica Farmaceutica quartic

molecular geometry and molecular properties out-of-plane interactions ( Eoop ) F. Melani Molecular Modeling in Chimica Farmaceutica

molecular geometry and molecular properties nonbond term (Enonbond ) van der Waals ( Evd. W ) hydrogen bond ( Ehbond ) electrostatic ( Ecoulomb ) F. Melani Molecular Modeling in Chimica Farmaceutica

molecular geometry and molecular properties Example: H 2 O (potential energy ) k Koh, b 0 OH, KHOH, and 0 HOH are parameters of the forcefield k b is the current bond length of one O-H k b' is the length of the other O-H bond k is the H-O-H angle. F. Melani Molecular Modeling in Chimica Farmaceutica

molecular geometry and molecular properties DOCKING The objective: searching the orientations with low interaction energies. F. Melani Molecular Modeling in Chimica Farmaceutica

molecular geometry and molecular properties MEP electronic density F. Melani Molecular Modeling in Chimica Farmaceutica

molecular vibration

molecular vibration

protein structure

protein structure k Most proteins will fold spontaneously in water, so amino acid sequence alone should be enough to determine protein structure k However, the physics are daunting: k 20, 000+ protein atoms, plus equal amounts of water k Many non-local interactions k Can takes seconds (most chemical reactions take place ~1012 --1, 000, 000 x faster) k Empirical determinations advancing rapidly. of protein structure are

protein structure k Proteins are polymers of amino acids linked by peptide bonds. k Properties of proteins are determined by both the particular sequence of amino acids and by the conformation (fold) of the protein. k Flexibility in the bonds around C : k (phi) k (psi) k sidechain

protein structure k Protein structure is described in four levels k Primary structure: amino acid sequence k Secondary structure: local (in sequence) ordering into k ( )Helices: compressed, corkscrew structures k ( )Strands: extended, nearly straight structures k ( )Sheets: paired strands, reinforced by hydrogen bonds k parallel (same direction) or antiparallel sheets k Coils, Turns & Loops: changes in direction k Tertiary structure: global ordering (all angles/atoms) k Quaternary structures: multiple, disconnected amino acid chains interacting to form a larger structure

helices

2 types of sh e e t s anti-parallel

tu r n s

combining secondary structures t o m a k e m otifs DNA-binding helix-turn-helix Calcium-binding motif

24 ways to arrange adjacent hairpins

alpha/beta domains Triosephosphate isomerase Dehydrogenase

Ramanchandran plot

Ramanchandran plot always glycine

protein structure cartoons

protein structure representations

protein structure representations

protein structure representations

protein structure representations

protein structure representations

protein structure k Proteins are created linearly and then assume their tertiary structure by “folding. ” k Exact mechanism is still unknown k Proteins assume the lowest energy structure k Or sometimes an ensemble of low energy structures. k Hydrophobic collapse drives process k Local (secondary) structure proclivities k Internal stabilizers: k Hydrogen bonds, disulphide bonds, salt bridges.

C a M K i n a s e II structure serine-threonine protein kinase calmodulin regulation multimer formation 12 subunits with the catalytic domains facing out

sequence comparison unc-43 ----------MQLQQINS GAFSVVRRCVHKTTGLEFAAKIINTKKLSARD r. Ca. MKII -------MATITCTRFTEEYQLFEELGK GAFSVVRRCVKVLAGQEYPAKIINTKKLSARD h. Ca. MKI MLGAVEGPRWKQAEDIRDIYDFRDVLGT GAFSEVILAEDKRTQKLVAIKCIAKEALEGKE r. Ca. MKI MPGAVEGPRWKQAEDIRDIYDFRDVLGT GAFSEVILAEDKRTQKLVAIKCIAKKALEGKE . . **** *. . * * *. . unc-43 FQKLEREARICRKLQHPNIVRLHDSIQEESFHYLVFDLVTGGELFEDIVAREFYSEADAS r. Ca. MKII HQKLEREARICRLLKHPNIVRLHDSISEEGHHYLIFDLVTGGELFEDIVAREYYSEADAS h. Ca. MKI GS-MENEIAVLHKIKHPNIVALDDIYESGGHLYLIMQLVSGGELFDRIVEKGFYTERDAS r. Ca. MKI GS-MENEIAVLHKIKHPNIVALDDIYESGGHLYLIMQLVSGGELFDRIVEKGFYTERDAS . * *. . ***** * * **. *****. . *. * *** unc-43 HCIQQILESIAYCHSNGIVHRDLKPENLLLASKAKGAAVKLADFGLAIEVN-DSEAWHGF r. Ca. MKII HCIQQILEAVLHCHQMGVVHRDLKPENLLLASKLKGAAVKLADFGLAIEVEGEQQRWFGF h. Ca. MKI RLIFQVLDAVKYLHDLGIVHRDLKPENLLYYSLDEDSKIMISDFGLSKMED-PGSVLSTA r. Ca. MKI RLIFQVLDAVKYLHDLGIVHRDLKPENLLYYSLDEDSKIMISDFGLSKMED-PGSVLSTA . * *. *. . . * *. ****** *. . ****. unc-43 AGTPGYLSPEVLKKDPYSKPVDIWACGVILYILLVGYPPFWDEDQHRLYAQIKAGAYDYP r. Ca. MKII AGTPGYLSPEVLRKDPYGKPVDLWACGVILYILLVGYPPFWDEDQHRLYQQIKARAYDFP h. Ca. MKI CGTPGYVAPEVLAQKPYSKAVDCWSIGVIAYILLCGYPPFYDENDAKLFEQILKAEYEFD r. Ca. MKI CGTPGYVAPEVLAQKPYSKAVDCWSIGVIAYILLCGYPPFYDENDAKLFEQILKAEYEFD . *****. **** ***** **. *. ** *. . unc-43 SPEWDTVTPEAKSLIDSMLTVNPKKRITADQALKV PWICNRERVASAIHRQDTVDCLKKF r. Ca. MKII SPEWDTVTPEAKDLINKMLTINPSKRITAAEALKH PWISHRSTVASCMHRQETVDCLKKF h. Ca. MKI SPYWDDISDSAKDFIRHLMEKDPEKRFTCEQALQH PWIAGDTALDKNIH-QSVSEQIKKN r. Ca. MKI SPYWDDISDSAKDFIRHLMEKDPEKRFTCEQALQH PWIAGDTALDKNIH-QSVSEQIKKN ** **. . ** * . . * ** *. . **. ***. . . * *. . ** unc-43 NARRKLKGAILTTMIATRNLSSKRSYRLTLGAEKLVISMKNIEYWQVLLNKIFATYKIKM r. Ca. MKII NARRKLKGAILTTMLATRNFSGG------------------KS h. Ca. MKI FAKSKWKQAFNATAVVRHMR--------------------r. Ca. MKI FAKSKWKQAFNATAVVRHMR-------------------- *. * * *. *. . …continued

…continued (overlapped) sequence comparison unc-43 SPEWDTVTPEAKSLIDSMLTVNPKKRITADQALKVPWICNRERVASAIHRQDTVDCLKKF r. Ca. MKII SPEWDTVTPEAKDLINKMLTINPSKRITAAEALKHPWISHRSTVASCMHRQETVDCLKKF h. Ca. MKI SPYWDDISDSAKDFIRHLMEKDPEKRFTCEQALQHPWIAGDTALDKNIH-QSVSEQIKKN r. Ca. MKI SPYWDDISDSAKDFIRHLMEKDPEKRFTCEQALQHPWIAGDTALDKNIH-QSVSEQIKKN ** **. . ** * . . * ** *. . ***. . . * *. . ** unc-43 NARRKLKGAILTTMIATRNLSSKRSYRLTLGAEKLVISMKNIEYWQVLLNKIFATYKIKM r. Ca. MKII NARRKLKGAILTTMLATRNFSGG------------------KS h. Ca. MKI FAKSKWKQAFNATAVVRHMR--------------------r. Ca. MKI FAKSKWKQAFNATAVVRHMR-------------------- *. * * *. *. . unc-43 KQCRNLLNKKEQGPPSTIKESSESS-QTIDDNDSEKGGGQLKHENTVVRADGATGIVSSS r. Ca. MKII G--G---NKKNDG----VKESSESTNTTIEDED------------- ***. * . ******. *. * unc-43 NSSTASKSSSTNLSAQKQDIVRVTQTLLDAISCKDFETYTRLCDTSMTCFEPEALGNLIE r. Ca. MKII ------TKVRKQEIIKVTEQLIEAISNGDFESYTKMCDPGMTAFEPEALGNLVE **. *. . *****. * unc-43 GIEFHRFYFD--GNRKNQ-VHTTMLNPNVHIIGEDAACVAYVKLTQFLDRNGEAHTRQSQ r. Ca. MKII GLDFHRFYFENLWSRNSKPVHTTILNPHIHLMGDESACIAYIRITQYLDAGGIPRTAQSE *. . ******. *. . ** * * **. unc-43 ESRVWSKKQGRWVCVHVHRSTQPSTNTTVSEF r. Ca. MKII ETRVWHRRDGKWQIVHFHRSGAPSVLPH--- *. ***. . *. * **. *** **

Protein t r u c t u r e p r o t e i n s structure basics k proteins consist mostly of a-helices, b-sheets, and turns. k the a-helices and b-sheets typically form the framework of the protein. k the turns and other atypical structures often play important binding and catalytic roles. k the core of the protein is hydrophobic, whereas the surface is usually polar or charged. k most turns and kinks have glycines and prolines

protein structure alpha helix

protein structure three-stranded antiparallel b-sheet

protein structure three-stranded antiparallel b-sheet, space filled

protein structure substrate binding cleft r. Ca. MKII SPEWDTVTPEAKDLINKMLTINPSKRITAAEALKHPWISHRSTVASCMHRQETVDCLKKF r. Ca. MKI SPYWDDISDSAKDFIRHLMEKDPEKRFTCEQALQHPWIAGDTALDKNIH-QSVSEQIKKN 297 ** **. . *** * . . . * ** *. . ****. . . . * *. . ** r. Ca. MKII NARRKLKGAILTTMLATRN r. Ca. MKI FAKSKWKQAFNATAVVRHM 316 *. * * *. .

sliced protein red - charged blue - polar green - hydrophobic

protein structure r. Ca. MKII HQKLEREARICRLLKHPNIVRLHDSISEEGHHYLIFDLVTGGELFEDIVAREYYSEADAS r. Ca. MKI GS-MENEIAVLHKIKHPNIVALDDIYESGGHLYLIMQLVSGGELFDRIVEKGFYTERDAS 119 . * * . . . ****** * * ** *****. . *. * *** r. Ca. MKII HCIQQILEAVLHCHQMGVVHRDLKPENLLLASKLKGAAVKLADFGLAIEVEGEQQRWFGF r. Ca. MKI RLIFQVLDAVKYLHDLGIVHRDLKPENLLYYSLDEDSKIMISDFGLSKMED-PGSVLSTA 178 . * *. *. ** * *. ****** * . . ****. .

protein structure r. Ca. MKII HQKLEREARICRLLKHPNIVRLHDSISEEGHHYLIFDLVTGGELFEDIVAREYYSEADAS r. Ca. MKI GS-MENEIAVLHKIKHPNIVALDDIYESGGHLYLIMQLVSGGELFDRIVEKGFYTERDAS 119 . * * . . . ****** * * ** *****. . *. * *** r. Ca. MKII HCIQQILEAVLHCHQMGVVHRDLKPENLLLASKLKGAAVKLADFGLAIEVEGEQQRWFGF r. Ca. MKI RLIFQVLDAVKYLHDLGIVHRDLKPENLLYYSLDEDSKIMISDFGLSKMED-PGSVLSTA 178 . * *. *. ** * *. ****** * . . ****. .

protein structure r. Ca. MKII HCIQQILEAVLHCHQMGVVHRDLKPENLLLASKLKGAAVKLADFGLAIEVEGEQQRWFGF r. Ca. MKI RLIFQVLDAVKYLHDLGIVHRDLKPENLLYYSLDEDSKIMISDFGLSKMED-PGSVLSTA 178 . * *. *. ** * *. ****** *. . ****. . r. Ca. MKII AGTPGYLSPEVLRKDPYGKPVDLWACGVILYILLVGYPPFWDEDQHRLYQQIKARAYDFP r. Ca. MKI CGTPGYVAPEVLAQKPYSKAVDCWSIGVIAYILLCGYPPFYDENDAKLFEQILKAEYEFD 238

protein structure

protein structure prediction

protein model Goodsell, PDB

protein structure prediction k the 3 -D structure of proteins is used to understand protein function and design new drugs

protein structure prediction k Structural Predictions just from raw protein sequence? 1. ggcacgaggc acggctgtgc aggcacgcat gcaggccagc …. 2. atctgcacgt ggttatgctg ccggagtttg ggccgccact….

protein structure prediction 1 2

protein structure prediction 50 100 5. 0 KD Hydrophobicity -5. 0 10 Surface Prob. 0. 0 1. 2 Flexibility 0. 8 1. 7 Antigenic Index -1. 7 CF Turns CF Alpha Helices CF Beta Sheets GOR Turns GOR Alpha Helices GOR Beta Sheets Glycosylation Sites Particular structural features can be recognised in protein sequences

structure prediction Comparative modeling k Modeling the structure of a protein that has a high degree of sequence identity with a protein of known structure k Must be >30% identity to have reliable structure

statistical methods k Residue conformational preferences: k Glu, Ala, Leu, Met, Gln, Lys, Arg k Val, Ile, Tyr, Cys, Trp, Phe, Thr k Gly, Asn, Pro, Ser, Asp - helix strand turn k Chou-Fasman algorithm: k Identification of helix and sheet "nuclei" k helix - 4 out of 6 residues with high helix propensity k sheet - 3 out of 5 residues with high sheet propensity k Propagation until termination criteria met

structure prediction Threading/fold recognition k Uses known fold structures to predict folds in primary sequence.

i n v e r s e p r o t e i n fo l d i n g k based on the assumption that there is limited number of structural protein classes (folds). One attempts to assign a new protein sequence to one of these classes.

fold recognition/threading. . . MLDTNMKTQL KAYLEKLT KPVELIATL DDSAKSAEIKELL. . . structure library

fold recognition/threading. . . MLDTNMKTQL KAYLEKLT KPVELIATL DDSAKSAEIKELL. . .

structure prediction Ab initio k Predicting structure from primary sequence data k Generate as many conformations as possible, and assign an energy score to each one k When the search terminates (usually when resources run out), the one with the lowest energy score is selected k Usually not as robust nor practical, computationally intensive

fu n c t i o n p r e d i c t i o n k Key problem: predict the function of protein structures based on sequence and structure information k Function is loosely defined, and can be thought of at many levels k Atomic or molecular level k Pathways level k Network level k Etc. k Currently, relatively little progress has been made in function prediction, particularly for higher order processes

function prediction Experimentation k Experimentally determine the function of proteins and other structures k The “gold standard” of function determination k Expensive in terms of time and money current methods

function prediction Annotation transfer k When sequence or structure analysis yields correspondences between structures, the known properties and function of one is used to extrapolate the properties and function of the other k This method has been extremely successful, but its drawbacks include [Bork et al. , 1998]: k Similar sequence or structure does not always imply similar function k The annotated information about the “known” protein or its sequence or structure information in the database may be incomplete or incorrect k Generally, only molecular functions of a protein can be inferred by analogy (i. e. not higher level functions) k From a formal point of view, properties derived in this manner must be verified through experimentation current methods

simulation-based analysis k Simulation-based analysis tests hypotheses with in silico experiments, providing predictions to be tested by in vitro and in vivo studies. k faster and more economical. k Example: Folding@Home

Folding@Home k Simulates protein folds k Folds dictate the function of the protein k Unfolding was discovered by Christian Anfinsen k When folds do not fold properly, it leads to diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease, Mad Cow, Parkinson’s disease k If the fold of the protein is known then it can also be unfolded

Folding@Home k Runs on a distributed system k Runs as a screensaver k Downloadable at: http: //folding. stanford. edu

drug design

structured-based drug design

structured-based drug design Compound databases, Microbial broths, Plants extracts, Combinatorial Libraries Random screening synthesis 3 -D ligand Databases Docking Linking or Binding Receptor-Ligand Complex Lead molecule 3 -D QSAR Target Enzyme OR Receptor 3 -D structure by Crystallography, NMR, electron microscopy OR Homology Modeling Testing Redesign to improve affinity, specificity etc.

3 D QSAR k quantitative structure activity relationships to calculate and predict k charge distribution, solubility, k hydrophobicity, lipophilicity

a c t i v e s i t e s

drug target site Glutathione-GR

drug target site DHFR

multiple alignments of DHFR

binding site analysis k In the absence of a structure of target-ligand complex, it is not a trivial exercise to locate the binding site!!! k This is followed by Lead optimization.

lead optimisation Active site Lead Optimization

drug design factors affecting the affinity of a small molecule for a target protein LIGAND. wat n +PROTEIN. wat n LIGAND. PROTEIN. watp+(n+m-p) wat k HYDROGEN BONDING k HYDROPHOBIC EFFECT k ELECTROSTATIC INTERACTIONS k VAN DER WAALS INTERACTIONS k STRAIN IN THE LIGAND ( BOUND) k STRAIN IN THE PROTEIN

dif f e re n c e be t we e n in h ibit or an d dru g Extra requirement of a drug compared to an inhibitor k k k Selectivity Less Toxicity Bioavailability Slow Clearance Reach The Target Ease Of Synthesis Low Price Slow Or No Development Of Resistance Stability Upon Storage As Tablet Or Solution Pharmacokinetic Parameters No Allergies

t h e r m o d y n a m i c s o f r e c e p t o r -l i g a n d b i n d i n g k k k Proteins that interact with drugs are typically enzymes or receptors. Drug may be classified as: substrates/inhibitors (for enzymes) agonists/antagonists (for receptors) Ligands for receptors normally bind via a non-covalent reversible binding. Enzyme inhibitors have a wide range of modes: non-covalent reversible, covalent reversible/irreversible or suicide inhibition. k Enzymes prefer to bind transition states (reaction intermediates) and may not optimally bind substrates as part of energy used for catalysis. k In contrast, inhibitors are designed to bind with higher affinity: their affi nities often exceed the corresponding substrate affinities by several orders of magnitude! k Agonists are analogous to enzyme substrates: part of the binding energy may be used for signal transduction, inducing a conformation or aggregation shift.

t h e r m o d y n a m i c s o f r e c e p t o r -l i g a n d b i n d i n g k To understand ‘what forces’ are responsible for ligands binding to Receptors/Enzymes, k It is worthwhile considering what forces drive protein folding – they share many common features. k The observed structure of Protein is generally a consequence of the hydrophobic effect! k Secondary amides form much stronger H-bonds to water than to other sec. Amides hydrophobic collapse k Proteins generally bury hydrophobic residues inside the core, while exposing hydrophilic residues to the exterior Saltbridges inside k Ligand building clefts in proteins often expose hydrophobic residues to solvent and may contain partially desolvated hydrophilic groups that are not paired: k The desolvation penalty is paid for by favourable (hydrophobic) interaction elsewhere in the structure.

docking m ethods k Docking of ligands to proteins is a formidable problem since it entails optimization of the 6 positional degrees of freedom. k Rigid vs Flexible k Speed vs Reliability k Manual Interactive Docking

GRID based docking methods k Grid Based methods k GRID (Goodford, 1985, J. Med. Chem. 28: 849) k GREEN (Tomioka & Itai, 1994, J. Comp. Aided. Mol. Des. 8: 347) k MCSS (Mirankar & Karplus, 1991, Proteins, 11: 29). k Functional groups are placed at regularly spaced (0. 30. 5 A) lattice points in the active site and their interaction energies are evaluated.

automated docking methods k Basic Idea is to fill the active site of the Target protein with a set of spheres. k Match the centre of these spheres as good as possible with the atoms in the database of small molecules with known 3 -D structures. k Examples: k DOCK, CAVEAT, AUTODOCK, LEGEND, ADAM, LINKOR, LUDI.

drug binding pocket of L. casei D H F R

p rediction & design of new drugs k Prediction of 3 -D Pf. DHFR using bacterial DHFR and homology modeling approach. k Search for the compounds using bifunctional basic groups that could form stable H-bonds in a plane with carboxyl group. k Optimize the structure of small molecules and then dock them on Pf. DHFR model. k Toyoda et. al. (1997). BBRC 235: 515 -519 could identify two compounds.

identifying new leads k These two compounds a triazinobenzimidazole & a pyridoindole were found to be active with high Ki against recombinant wild type DHFR. k Thus demonstrate use of molecular modeling in malarial drug design.

physiome project

virtual human

virtual human Simulation of complex models of cells, tissues and organs http: //www. physiome. org/

physiome project k “A worldwide effort to define the physiome by developing databases and models which will facilitate the understanding of the integrative functions of cells, organs and organisms. ” defenition Physiome is the quantitative and integrated description of the functional behavior of the physiological state of an individual or species.

physiome project main objective: “… to understand describe the human organism, its physiology and pathophysiology quantitatively, and to use this understanding to improve human health. ”

physiome project Specific Objectives: 1. To develop a database with observations of physiological phenomenon and interpret these in terms of mechanism (reductionism). 2. To integrate experimental information into quantitative descriptions of the functioning of humans and other organisms (modern integrative biology glued together via modeling). 3. To disseminate experimental data and integrative models for teaching and research.

physiome project Specific Objectives: 4. To foster collaboration amongst investigators worldwide, in an effort to speed up the discovery of how biological systems work. 5. To determine the most effective targets (molecules or systems) for therapy, either pharmaceutical or genomic. 6. To provide information for the design tissue-engineered, biocompatible implants.

physiome project Issues being addressed: 1. Markup language -- development of SBML (in Caltech) for representing biochemical networks and Cell. ML for electrophysiology, mechanics, energetics and general pathway. 2. Mathematical models -- development of models that are “anatomically based” and “biophysically based” to link gene, protein, cell, tissue , organ and whole body systems physiology.

physiome project Issues being addressed: 3. Web-accessible databases -- For easy data exchange, groups at MIT and UCSD are developing standards for this. Example databases: Genomic Databases, Protein Databases, Material Property Databases, Anatomical Model Databases, Clinical Databases 4. Development of new instrumentation 5. Development of Modeling tools, GUIs and webaccessible tools for visualization of complex models.

physiome project 1. Microcirculation A common functional system between organs; It provides an important coupling between cells, tissues, and organs. http: //www. bme. jhu. edu/news/microphys

physiome project 2. Musculo-skeletal system Continues to extend the database of parameterised bone geometry to individual muscles, ligaments and tendons. Anatomically a detailed model of Skeleton. Renderedfor b finite element mesh the bones and a subset of the muscles a http: //www. bioeng. auckland. ac. nz/projects/nerf/skeletal. php b

physiome project Computational model of the skull and torso. a b The layer of skeletal muscle is highlighted. The heart and lungs shown within the torso. a b

physiome project 3. Cardiome Project An attempt to provide an integrated model of the heart, incorporating electrical activation, mechanical contraction, energy supply and utilization, cell signaling and many other biochemical processes. Heart model with a textured epidermal surface

physiome project Fibrous-sheet architecture of the heart. Ribbons are drawn in the plane of the myocardial sheets a on the epicardial surface of the heart, b at midwall, and c on the endocardial surface. Note the large fibre angle changes. These fibre-sheet material axes are needed for computation of both myocardial activation and ventricular mechanics. a b heart structure c

physiome project The finite element model of the right and left ventricle of the heart showing various anatomical structures. Geometric information is carried at the nodes of the finite element mesh and interpolated with cubic Hermite basis functions. heart structure

physiome project Mechanics of the cardiac cycle, computed by large deformation finite element analysis, at a zero pressure state, b end-diastole, c mid-systole, d end-systole. Note the apex to base shortening and the twisting about the long axis. Also note the six generations of discretely modeled coronary vessels embedded within the myocardial elements which are used to compute coronary flow throughout the cardiac cycle. a b c ventricular mechanics d

physiome project The collagenous structure of the extra-cellular myocardial tissue matrix, as revealed by confocal microscopy. The material axes used for defining mechanical and electrical constitutive laws in the continuum modeling of the myocardium are based on these microstructurally defined axes. ventricular mechanics

physiome project Activation wave front computed on the finite element model using finite difference techniques based on grid points which move with the deforming myocardium. Bi-domain current conservation equations are solved with trans-membrane ionic currents. The stimulus in this case is a point on the left ventricular endocardial surface near the apex. The activation sequence is heavily influenced by the fibrous-sheet architecture of the myocardium. myocardial activation

physiome project Computed flow in the coronary vasculature coronary perfusion

physiome project Epicardial Fibers – FEM Model www. ccmb. jhu. edu ventricular fluid flow Endocardial Fibers – FEM Model

physiome project Human Torso model has been developed which includes the heart, lungs and the layers of skeletal muscle, fat and skin. Current flow from the heart into the torso is computed in order to predict the body surface potentials arising from activation of the myocardium.

physiome project 4. Lungs Development of models of the integrated function of various physical processes operating in the lung. 5. Bladder and Prostate An anatomically detailed model of the bladder and prostate is developed. 6. Circulation System A model of the circulation system is being developed based on the Visual Human Project dataset (http: //www. nlm. nih. gov/research/v isible)

future Development of Precision Models k Simulation requires the integration of multiple hierarchies of models that have different scales and qualitative properties k Some biological processes take place within milliseconds while others may take hours or days Example: Protein folding vs. Cell Mitosis

future Development of Precision Models k Biological processes can involve the interaction of different types of processes (i. e. biochemical networks coupled to protein transport, chromosome dynamics, cell migration or morphological changes in tissues)

future Development of Precision Models k Types of modeling: k Using differential equations and stochastic simulation k Many cell biological phenomena require calculation of structural dynamics k Deformation of elastic bodies k Spring-mass models and other physical processes

t h e e n d

3010e6474ddfb8acf4fab8ce2076cae0.ppt