4d7360dcbee0e80474bfa50befb955fa.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 122

BILINGUAL CODE-MIXING Kevser Yağlı Hülya Arbaş Merve Çizgen Pınar Akçay

BILINGUAL CODE-MIXING • What is Code-Mixing? • Interutterance and Intrautterance Codemixing • Adult Code-Mixing • Child Code-Mixing • Unitary Language-System Hypothesis

What is code-mixing? • Code-mixing is the use of elements from two languages in the same utterance or in the same stretch of conversation. e. g “Ama konuyu bu contextte ele almak zorundayız. ”

Types of Code-mixing • Intrautterance code-mixing: When the elements from two languages occur in the same utterance. e. g “Alguien se murio en ese cuarto that he sleeps in. ” (Someone died in that room. . ) (Zentella, 1999, p. 119)

Interutterance Code-Mixing • When the elements from two languages occur in two different utterances in the same conversation. e. g “Pa, me vas a comprar un jugo? It cos’ 25 cents. ” (Are you going to buy me orange juice? ) (Zentella, 1999, p. 118)

• The mixed elements can be whole words, phrases, clauses, or pragmatic patterns • Mixing can involve small units of language (sounds, morphemes, words) as well as larger chunks (phrases, whole clauses).

• “Estamos como marido y woman” (we are like man and. . ) • “I’m going with her a la esquina” (. . . to the corner) • “You know how to swim but no te tapa. ” (. . . it won’t be over your head) • “Donne moi le cheval; the horse!” (Give me the horse, . . ) Mixing at the phrase level: • Putzen Zaehne con jabon (brushing teeth with soap) (Genesee & Meisel, 1989)

• Semantic mixing: - You want to open the lights? - Televizyon-a bak-ıca-m (Turkish-German) (In TK: bak ‘look’ is not used to express ‘watching TV’) (Genesee &Meisel, 1989)

Do all bilinguals code-mix in the same amount? • Genesee et. al’s 1995 research • They worked with children who are learning French and English from their parents at home. • They have found that children mixed within utterances less than 10% of the time, but there are very large individual differences.

• Some of the children mixed as little as 2% of the time, while the others mixed much more frequently. (Genesee et. al, 1995) • WHY?

ADULT CODE-MIXING • Understanding how, when and why adults code-mix can help us better understand child BCM • Because the patterns we see in adults give an indication of the developmentally typical end point of child code-mixing.

• Like bilingual children, bilingual adults mix languages both within utterances and across utterances.

• However, they are more likely to code-mix in informal settings than in public settings. (Zentella, 1995) WHAT DOES IT IMPLY?

• It implies that mixing is a casual and improper way during speech. What do you think?

• Researchers say that; • When adults mix languages from one utterance to another, each utterance is grammatically well-formed according to the rules of the related language.

• However, when they mix within the utterances, the grammars of two languages are mixed, and the utterance might be probably incorrect.

• Researchers agree that in most cases, each language segment of a mixed utterance is well-formed according to the rules of tis respective language. When it is not, it is probably due to performance errors. Look at the previous examples.

• e. g “ I’m going with her a la esquire” (. . . to the corner) • This shift is correct according to both English and Spanish word order.

What about • “ Yo have been able to ensenar Maria leer (I teach. . . Maria to read) ensenar= to teach Double infinitivals!

Reasons for Code-mixing 1. The type of code-mixing depends on the level of proficiency of the bilingual adults. • Bilingual adults proficient in both languages code-switch from one language to the other flawlessly. • Learners in the process of developing proficiency lack the linguistic competence to code-mix flawlwessly and fluently.

• “ Yo have been able to ensenar Maria leer (I teach. . . Maria to read) ensenar= to teach Double infinitivals!

2. Filling lexical gaps in their languages is another reason for code-mixing.

Any difference between codemixing of fluent BLs vs SLLs? • Second language learners tend to show that they are going to switch, and they make a mistake. • They “FLAG” their mixing.

Flagging • It is a pragmatic strategy second language learners can use to isolate the mixed elements because they may not know how to integrate them grammatically. • It signals that the SL learner is about to mix and may make a mistake.

• e. g “Hier, je suis alle au hardware storehow do you say hardware store in French? ” (Yesterday I went to the. . . )

Other reasons for code-mixing in bilingual adults • To express that they are bilingual • As a show of intimacy of ethnic closeness to people who share the same culture • To narrate specific episodes that they experienced in bilingual environment. • To show respect for others who are more proficient in one or the other language. • To show that they are different form monolingual people around them.

Conclusions • BCM is a common feature of language use among bilingual adults. • There are social, cultural, and linguistic purposes for code-mixing. • So, adult BCM is not random; it is purposeful at certain times.

WHY DO BILINGUALCHILDREN CODE-MIX? • BCM is a cause for concern because many people, educationalists, and specialists believe that BCM indicates that the child is not developing typically or s/he is confused and can not seperate the two languages. (Leopold, 1949)

• According to this view, the child is actually like a monolingual child, not having seperated the two different language systems. • This view has been discussed and the focus is children between 2 -4 years of age.

Unitary Language System Hypothesis • As an answer to child BCM: “young bilingual children mix words and other elements form their two languages in the same utterance because their languages are not differentiated in the early stages of development. ”

• In order to test this hypothesis, we need to see how BC use language with others to see if they use their languages without regard to the language of their partners.

• Suggests that “Differentiation takes place later, around 3 years of age. ” • Views the BC’s code-mixing as a symptom of confusion and incompetence.

Genesee et. al’s 1995 study • They observed English-French bilingual children form Montreal during nauralistic interactions with their parents at home. • The parents were speaking different native languages (one-parent-one-language rule) • BC were observed in three cases: with fathers alone, with mothers alone, and with both parents.

• Aim: to see the children’s ability to keep their languages seperate in different language contexts. • Result: they used more French with their French-speaking parent than they did with the English-speaking parent. – when they were both present, the children used the appropriate language more for each parent

• Critiques of this study: most of the children tended to use one language more than the other with both parents, and this was their more proficient language in each case. • So, knowing that their parents knew both languages, the children made use of all their linguistic resources

Genesee et. al’s 1996 study • Aim: to examine the limits of bilingual children’s ability to use their developing languages appropriately • They observed a number of French. English BC during play sessions with monolingual peers. • The BC didn’t know the preferred language of their monolingual peers.

• In three of the four children, the language spoken by their peers was the less proficient language of the BC. • Three of the four children used more of the stranger’s language than they did with their parents. • They also used less of the language that was not known by the stranger.

• One of the children did not accommodote his language at all.

• In conclusion, despite the fact that these three children had no prior experience with this adult and they were compelled to use their less proficient language, they not only used the appropriate language but they also used it more frequently with the monolingual stranger than with the bilingual parent. • This finding also refutes the confusion hypothesis.

• Child BCM does not reflect any confusion or a unitary system of language in the initial stages. • Researchers now agree that Unitary Language System Hypothesis is not valid and bilingual children can differentiate their languages according to the speaker.

2. Gap Filling Hypothesis • Another alternative solution; • BCM serves to fill gaps in the developing child’s linguistic competence.

2. Gap Filling Hypothesis The simplest mixing occurs at lexical level. § According to the Lexical Gap Hypothesis, bilingual children mix words from language X when using language Y becuse they do not know the appropriate word in language Y.

2. Gap Filling Hypothesis Mixing syntactic patterns might also occur in order to fill syntactic gaps in the child’s knowledge of the target language.

2. Gap Filling Hypothesis There is considerable evidence for this explanation; First; as it is generally observed, young bilingual children mix more when they use their less proficient language.

2. Gap Filling Hypothesis Second; there is direct evidence that bilingual children are much more likely to mix words for which they do not know the translation equivalent in the target language.

2. Gap Filling Hypothesis The study by Genesee, Paradis, & Wolf (1995) serves for the second type of evidence. They requested to keep diaries from the parents of the two young bilingual children.

2. Gap Filling Hypothesis The results; The explanation was valid for both of the children. For the one boy, 100 % of the words he code-mixed with his father were words the boy did not know in his father’s language.

2. Gap Filling Hypothesis Another alternative solution; BCM serves to fill the gaps in the developing child’s linguistic competence.

2. Gap Filling Hypothesis For the other boy, as well, the majority words that he code-mixed were words for which he did not know the translation equivalent, in other words he did not have the translation equivalents for 65% of the words he code-mixed.

2. Gap Filling Hypothesis In some cases of lexical mixing, it might not be a matter of the child not knowing the appropriate word, but might not exist in the target language. French word “dodo”

2. Gap Filling Hypothesis In French-English bilingual families, French words such as; • Scholarity (years of schooling) • Bourse (fellowship or grant) • Formation (training) • Stage (internship) are commonly used by English speakers in Montreal.

2. Gap Filling Hypothesis Your examples? ?

2. Gap Filling Hypothesis Section Consent

2. Gap Filling Hypothesis Borrowing is a well-documented phenomenon by which language acquire new vocabulary. While English borrows many words related to the food and eating from French, the other languages borrow words related to computers and technology from English.

2. Gap Filling Hypothesis When bilingual child use code-switching strategy inappropriately with monolingual children, it is usually not because they have a language impairment, but they do not know the specific word in the target language or they simply fail to grasp that their interlocutor is monolingual.

3. Pragmatic Explanations The other explanation for BCM concerns the pragmatics of communication. Bilingual children code-mix for pragmatic effect – to emphasize what they are saying , to quote what someone else said, to protest, to narrate etc.

3. Pragmatic Explanations For some bilingual children, one of their languages may have more affective load than the other, and they may use that language to express emotion when they speak.

3. Pragmatic Explanations Mixing in order to quote what someone else said or when narrating events can be a way of rendering one’s discourse more authentic if the event or material being quoted took place in the other language.

3. Pragmatic Explanations Mixing speech or speaking styles is common in everyday discourse; it makes discourse colorful, authentic and varied.

What are your pragmatic codeswitches?

4. Social Norms Communities have different social norms with respect to appropriate kinds of mixing, when and where mixing occurs, and how often mixing is appropriate.

4. Social Norms The specific forms of code-mixing children learn are also shaped by social norms in their community. Puerto Rican community fluent form of mixing, several switches from Spanish to English and back again

Multiple Code - Switches “But I used to eat bofe (brain), the brain. And then they stopped selling it beacuse, tenian, este, le encontraron que tenia (they had, uh, they found out that) worms. I used to make some bofe! Despues yo hacia uno d’esos (then I would make one of those) concotions: the garlic con cebolla, y hacia un moho, y yo dejaba que se curare eso (with onion, and I’d make a sauce, and I’d let that sit) for a couple of hours. Then you be drinking and eating that shit. Wooh! It’s like eating anchovies when they drinking. Delicious!”

Multiple Code - Switches But the situation is different among French. English bilingual people in the Ottawa region of Canada. The French Canadians use a different form of mixing which tends to be less frequent and less fluent and it is often flagged to indicate that the discourse is bilingual.

Flagging The pattern and frequency of code mixing varies in a community from one family to another and from one invidual to another. Lanza’s study (1997) Siri the child Father Native Norwegian Mother Native English

Flagging Döpke’s study (1992) Study of German- English bilingual families in Australia. Some of the families she studied with were more successful in promoting the use of minority language (German) in a community that was otherwise dominated by English. Döpke attributed this success, in part, to the use of child-centered discourse styles by the parent who spoke the minority language.

Flagging These studies illustrate that children differ in their style and frequency of BCM as well as in their preference to code-mix or stick to one language as a result of the different discourse styles of their parents.

Flagging When the bilingual children persist in using the mixing patterns in inappropriate and uneffective settings, it means that there are some other factors at play; I. Code-mixing fills gaps in the child’s proficiency in the target language II. Code-mixing is pragmatic III. Code-mixing asserts the child’s identity as a bilingual person or a member of a different cultural group.

IS CHILD BILINGUAL CODE-MIXING GRAMATICALLY DEVIANT? Commonly held perception: code-mixing is an ungrammatical form of language. That’s why parents and others are often concerned about child BCM and avoid codemixing with children. 69

IS CHILD BILINGUAL CODE-MIXING GRAMATICALLY DEVIANT? Adult BCM is constrained by the grammars of both languages. The most proficient bilingual adults engage in the most sophisticated forms of mixing. Is children’s code-mixing grammatically constrained or deviant? 70

IS CHILD BILINGUAL CODE-MIXING GRAMATICALLY DEVIANT? Grammatical properties of intrautterances code mixing by children acquiring a variety of language pairs • English and French (Genesee&Sauve, 2000; Paradis, Nicholadis, &Genesee, 2000), • French and German (Köppe; Meisel, 1994), • English and Inuktitut (Allen, Genesee, Fish&Crago, 2002) • English and Norwegian (Lanza, 1997) • English and Estonian (Vihman, 1998) 71

IS CHILD BILINGUAL CODE-MIXING GRAMATICALLY DEVIANT? The vast majority of bilingual children’s code -mixing is systematic and, specifically, conforms to the grammatical constraints of the two participating languages. This is true for bilingual children as soon as they begin to use multiword utterances when grammatical constraints become evident in their language use. 72

IS CHILD BILINGUAL CODE-MIXING GRAMATICALLY DEVIANT? Bilingual children code-mix grammatically as soon as they begin to organize their language according to grammatical principles They learn how to codemix grammatically at the same time as they learn their two languages. 73

IS CHILD BILINGUAL CODE-MIXING GRAMATICALLY DEVIANT? Code-mix grammatically comes automatically with being a bilingual learner. They also learn the frequency or patterns of mixing that characterize their own families and communities. 74

IS CHILD BILINGUAL CODE-MIXING GRAMATICALLY DEVIANT? Common form of code-mixing: Mixing of single content words from one language into and utterance or sentence that is organized according to the grammar of the other language. This form of mixing is common because young children produce short, syntactically simple sentence. 75

IS CHILD BILINGUAL CODE-MIXING GRAMATICALLY DEVIANT? Why do children code-mix grammatically?

IS CHILD BILINGUAL CODE-MIXING GRAMATICALLY DEVIANT? When children mix single words, they usually treat the mixed word as if it were part of the host language and therefore produce grammatically correct constructions. Borrowing of single words: online, internet, check-in etc. 77

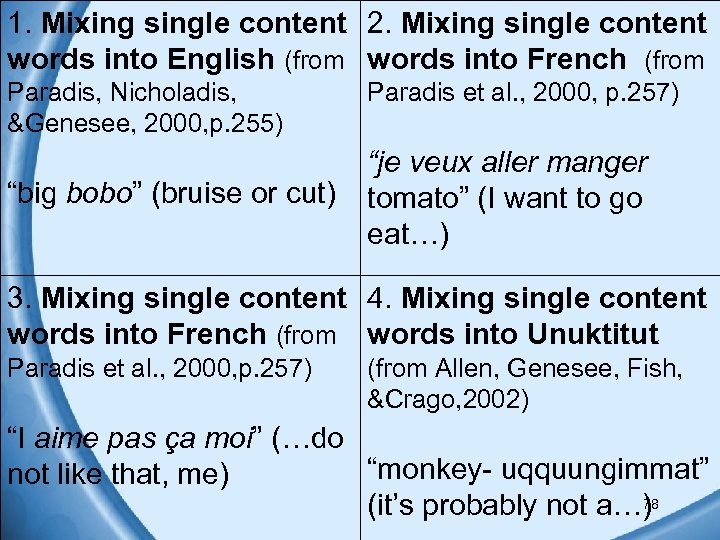

1. Mixing single content 2. Mixing single content words into English (from words into French (from Paradis, Nicholadis, &Genesee, 2000, p. 255) “big bobo” (bruise or cut) Paradis et al. , 2000, p. 257) “je veux aller manger tomato” (I want to go eat…) 3. Mixing single content 4. Mixing single content words into French (from words into Unuktitut Paradis et al. , 2000, p. 257) (from Allen, Genesee, Fish, &Crago, 2002) “I aime pas ça moi” (…do “monkey- uqquungimmat” not like that, me) 7 (it’s probably not a…)8

IS CHILD BILINGUAL CODE-MIXING GRAMATICALLY DEVIANT? In every case the English word has been inserted in the correct place, the word is being treated as a member of the host language. Code-mixing in simultaneous bilingual people indicates that their mixing is constrained and reflects their grammatical competence in both languages. 79

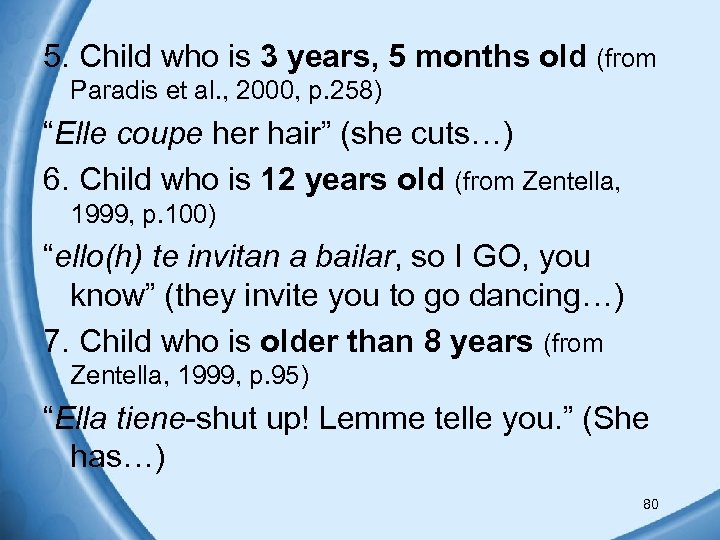

5. Child who is 3 years, 5 months old (from Paradis et al. , 2000, p. 258) “Elle coupe her hair” (she cuts…) 6. Child who is 12 years old (from Zentella, 1999, p. 100) “ello(h) te invitan a bailar, so I GO, you know” (they invite you to go dancing…) 7. Child who is older than 8 years (from Zentella, 1999, p. 95) “Ella tiene-shut up! Lemme telle you. ” (She has…) 80

IS CHILD BILINGUAL CODE-MIXING GRAMATICALLY DEVIANT? Not only do the forms of code-mixing become more sophisticated with age, but also they serve pragmatic functions. 81

Key Points and Clinical Implications Key Point 1 • BCM is a typical pattern of language use among bilingual children and adults. • Most child BCM is grammatical. Thus, BCM is best viewed as a reflection of the child’s developing linguistic competence. • In order to code-mix grammatically, BC must be acquiring both grammars. 82

Key Points and Clinical Implications • BCM should not be taken as evidence for language delay or impairment. • Children should not be reprimanded or discouraged from code-mixing. • Languge development specialists should not recommend that children use only one language. 83

Key Points and Clinical Implications Key Point 2 • BCM is a communicative resourse. • BCM is also a resource for fully proficient B people who want to talk about ideas, events, or things that are part of their unique lives as B individuals or that are best expressed in one or the other language. 84

Key Points and Clinical Implications • Most bilingual children will adapt to the communicative demands of monolingual social situations, given appropriate time and supportive encouragement. • Efforts to get the child to express herself monolingually should be positive. • Language enrichment in relevant areas should be provided. • The child should not be isolated from the 85 positive incentives.

Key Points and Clinical Implications Key Point 3 • BCM is shaped by social norms in the families and communities in which BC live. 86

Key Points and Clinical Implications • BC should not be singled out for special attention or referred for further examination because of suspicions of impaired or delay development. • Most BC will acquire the social norms appropriate to a new situation if they are given sufficient time and positive encouragement. 87

Key Points and Clinical Implications • The child should be provided with appropriate models that display appropriate behaviors and should be encouraged to adopt those behaviors. • Professionals should familiarize themselves with the patterns of language and social behavior. • New steps must be taken in the new setting to help the child adjust. 88

Key Points and Clinical Implications Key Point 4 • BCM may reflect the child’s cultural identity. • Language is a fundamental part of who s/he is. 89

Key Points and Clinical Implications • Professionals should provide BC with strategies for coping with challenges. • BC should be given assistance in acquiring the social skills and cultural understanding. • Steps should be taken to ensure that BC from minority cultures do not become isolated from other children. 90

Summary • BCM can provide useful insights about the language competence of bilingual children. • The prevalence of language impairment and delay is the same among bilingual children and monolingual children. • Overestimation of impairment and delay may result from overinterpretation of BCM as evidence for impairment. 91

Chapter 14 CODE-MIXING IN EARLY L 2 LEXICAL ACQUISITION Joanna ROKITA 92

Code-mixing in Early L 2 Lexical Acquisition Process of L 2 acquisition should be similar to the bilingual one, even though the rate of acqusition will be much slower. As code-mixing is a typical interlanguage feature in early SLA in naturalistic settings, early L 2 learners should pass through the same stage. 93

Code-mixing in Early L 2 Lexical Acquisition • Do early L 2 learners code-mix, and if so, • What are the reasons for code-mixing, • What type of code-mixing do they perform? 94

Code-mixing in Early L 2 Lexical Acquisition Appel and Muysken (1987: 115) Code-mixing: Intrasentential switch occuring in the mid-sentence. Code-switching: It is used to generalise all types of switches. 95

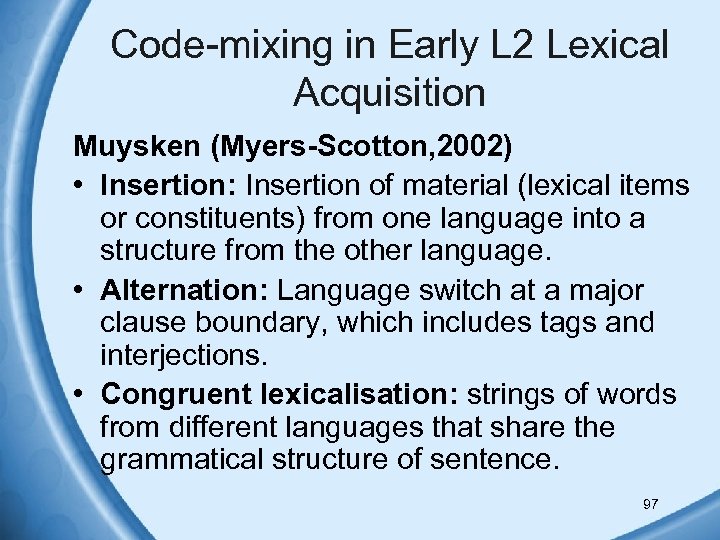

Code-mixing in Early L 2 Lexical Acquisition Muysken (Myers-Scotton, 2002) Code-mixing: All cases where lexical items and grammatical features from two languages appear in one sentence Code-switching: Rapid succession of several languages in a single speech event 96

Code-mixing in Early L 2 Lexical Acquisition Muysken (Myers-Scotton, 2002) • Insertion: Insertion of material (lexical items or constituents) from one language into a structure from the other language. • Alternation: Language switch at a major clause boundary, which includes tags and interjections. • Congruent lexicalisation: strings of words from different languages that share the grammatical structure of sentence. 97

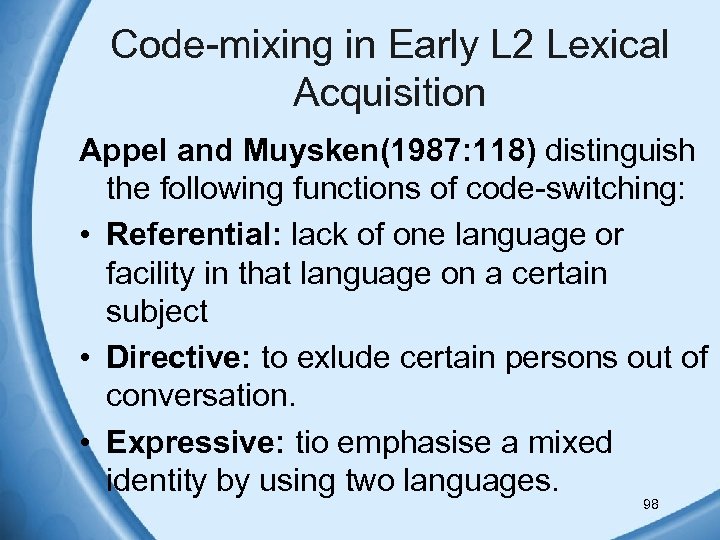

Code-mixing in Early L 2 Lexical Acquisition Appel and Muysken(1987: 118) distinguish the following functions of code-switching: • Referential: lack of one language or facility in that language on a certain subject • Directive: to exlude certain persons out of conversation. • Expressive: tio emphasise a mixed identity by using two languages. 98

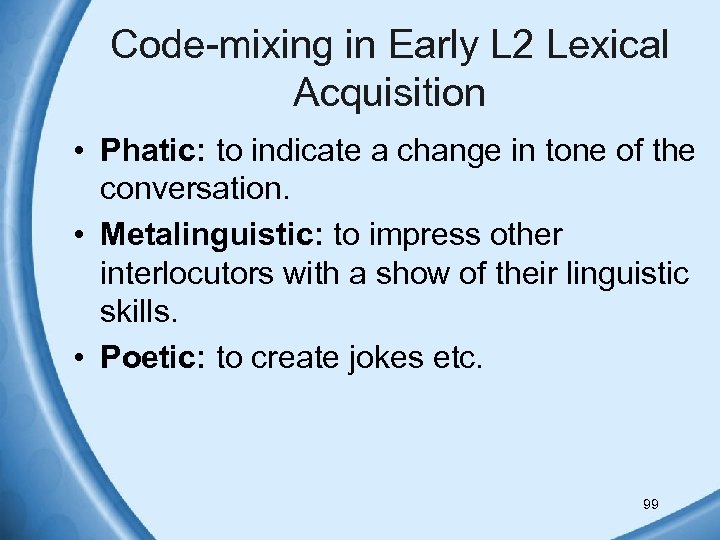

Code-mixing in Early L 2 Lexical Acquisition • Phatic: to indicate a change in tone of the conversation. • Metalinguistic: to impress other interlocutors with a show of their linguistic skills. • Poetic: to create jokes etc. 99

THE STUDY

The Background • A Helen Doron school • Roughly follows the principles of the Direct and TPR methods. • The language contact = one 30 -min class meeting per week. • To ensure regular exposure to L 2 parents need to play the course cassette to children twice a day = 30 -min L 2 contact every day.

• In principle mere background listening is supposed to be sufficient. • In reality parental support in the lang. interaction plays a beneficial role in L 2 acquisition. • i. e. Actively participating mothers in their English plays better retention of the course material & consequently acquire the language.

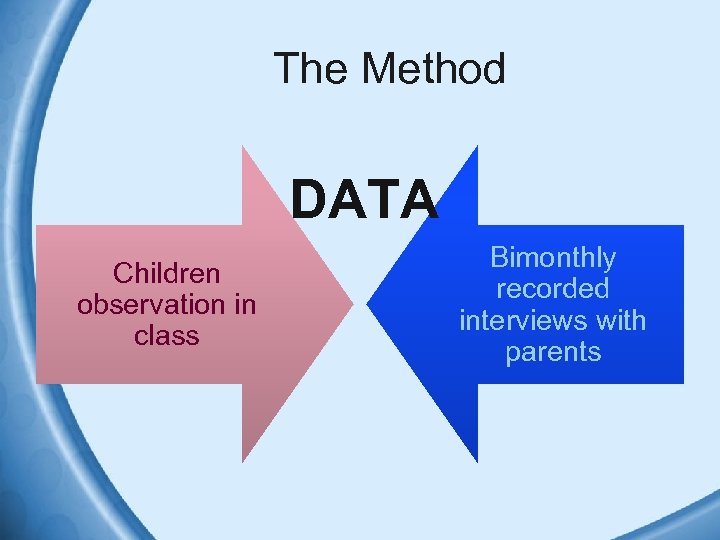

The Method DATA Children observation in class Bimonthly recorded interviews with parents

• Interview: parents were to recall any examples of their children’s L 2 performance. Rokita was mainly interested in the spontaneous, rather than elicited L 2 performance. Parental reports were the most suitable method for the study.

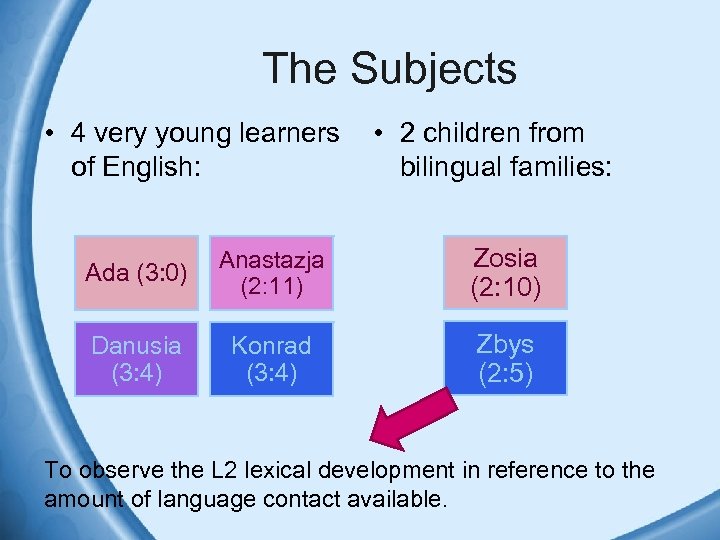

The Subjects • 4 very young learners of English: • 2 children from bilingual families: Ada (3: 0) Anastazja (2: 11) Zosia (2: 10) Danusia (3: 4) Konrad (3: 4) Zbys (2: 5) To observe the L 2 lexical development in reference to the amount of language contact available.

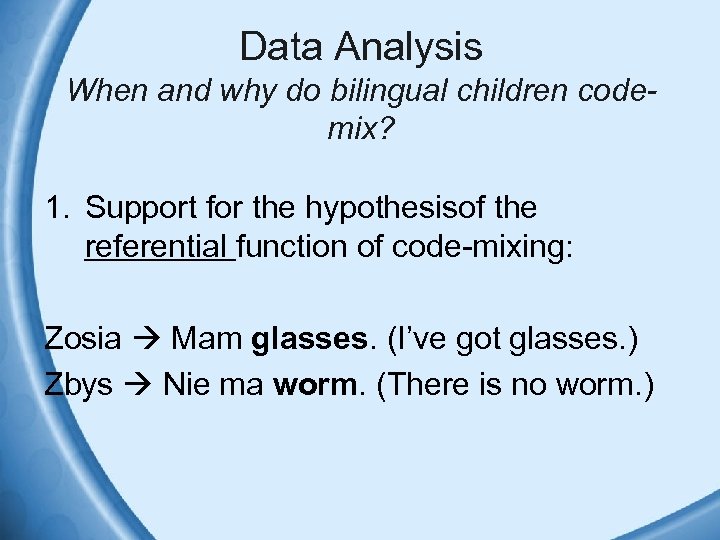

Data Analysis When and why do bilingual children codemix? 1. Support for the hypothesisof the referential function of code-mixing: Zosia Mam glasses. (I’ve got glasses. ) Zbys Nie ma worm. (There is no worm. )

• Dersi drop ettin mi? • Hocaya consent yolladım ama daha cevap gelmedi. • Save etmeyi unutma sakın! • Mail attım ben ona dün. • Facebook’taki resmimi like etmiş, gördün mü? What about you?

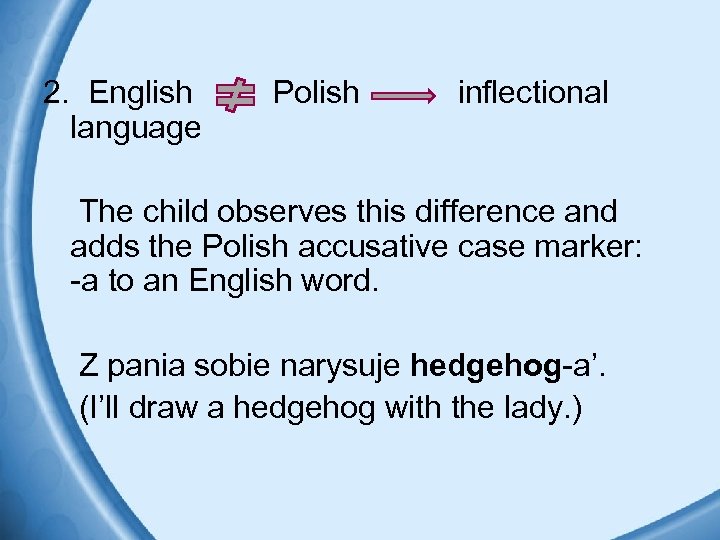

2. English language Polish inflectional The child observes this difference and adds the Polish accusative case marker: -a to an English word. Z pania sobie narysuje hedgehog-a’. (I’ll draw a hedgehog with the lady. )

Muysken’s classification of insertion • A content word is inserted morphological integration! The most advanced stage of code-mixing. The child is able to manipulate the word in accordance with grammar rules of the dominant language.

• Consent-imi aldım oley! • Buradaki suffix-i gördün mü? • Assigment-ın deadline-ı ne zaman?

3. The grammatical morpheme that is acquired first in L 2 seems to be the plural ending –s. To sa moje balon-s. Overgeneralisation The criterion of simplicity

4. Apart from content words, the rules of conjugation seem to be trasferred onto English verbs, as well. Mamisu, co ty do-isz? The 2 nd person singular morpheme.

5. Insertion is not the only type of codemixing. Alternation can also be observed in early bilingual production. Eeh, ubral sie bo jest zimno, /je/. Eeh, he put on clothes, because he’s cold, yeah.

Do early L 2 learners code-mix? 6. To jest moj daddy. This is my daddy. insertion type of code-mixing In the case of bilinguals The child does not know the equivalent in L 1. In the case of early L 2 learners The words are treated as synonymous. i. e. The child knows the word ‘tatus’ as well, and uses the two interchangeably.

7. ‘To jest moj bus’. (This is my bus. ) ‘duzy truck’ (a big truck) The Polish equivalents: ‘autobus’ & ‘ciezarowka’ Phonetic & morphological simplicity

8. C: Yummy! M: Co jest ‘yummy? ’ (What is yummy? ) C: A galaretka. (A jelly. ) The child has overextended the use of English articles to Polish nouns. This might be proof that at least partial acquisition has taken place.

9. Younger children seem to prefer to stick to formulae as the only type of insertion they make. Tatus jest the best. (Daddy is the best. ) They apply them in the same position in the sentence which does not require any inflectional adjustments. WHY?

Comparing code-mixing in young bilinguals and early L 2 learners • Code-mixing is common in the performance of bilingual C. • Examples of insertion are the most common, but rare examples of alternation can also be observed. • It is very rare to observe the examples of codemixing in early L 2 acquisition. • They are restricted to the simplest form of insertion. single words.

Bilingual Acquisition Early L 2 Acquisition • Lack of an appropriate word. • Assumed simplicity. • Attempt at discovering the grammar rules of L 2, by means of transfer from L 1 to L 2. • This proves that BC treat the two systems wholistically. • Use of a synonym. • A play with word. • Lexical or morphological simplicity. • Why is code-mixing in early L 2 acquisition uncommon?

Otworz mi to mamo! Daddy, help! (Open this for me, mummy! Daddy, help!) This demonsrates that children know which language to select to which speaker. Code-mixing is not caused by competence error. Code-mixing occurs due to lack of an appropriate word or it is assumed simplicity.

One significant similarity between codemixing in young bilinguals and early L 2 learners. . . applying the criterion of simplicity for the choice of language code, even though the L 2 word may be available. Phonologically easier Morphologically shorter

4d7360dcbee0e80474bfa50befb955fa.ppt