22fa29dcfa76cde18a11cec2cba49b38.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 55

Between adjective and noun: category / function mismatch, constructional overrides and coercion Peter LAUWERS Ghent University & University of Leuven Peter. lauwers@ugent. be Workshop on the Syntax and Semantics of Nounhood and Adjectivehood Peter Lauwers Barcelona, March, 24 -25, 2011

1. Introduction Peter Lauwers

Topic of this talk Nominalized adjectives (NAs): Adj N (1) simple. ADJ, beau. ADJ (1 a) le simple et le beau 'the simple and the beautiful' (1 b) Faire du beau avec du simple, ça c'est de l'art. ‘To make beautiful things (stuff) with simple things (stuff), that is what art is about’ Adjectivized nouns (ANs): N Adj (2) théâtre. N des costumes très ‘théâtre’ Peter Lauwers 'very theater-like costumes'

Structure of the talk 1. 2. Data: nominalized adjectives (= NAs) 3. Problematic accounts 4. A syntactic analysis in terms of categorial mismatch 5. Adjectivized nouns (= ANs) 6. Peter Lauwers Introduction Conclusions

2. The data: nominalized adjectives (NAs) Peter Lauwers

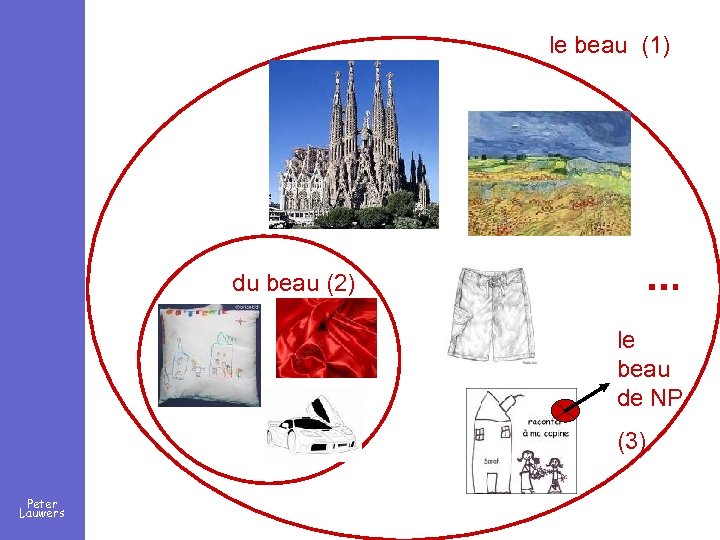

2. 1. NAs: introduction Meaning effects (I) le beau, le simple: ‘the beautiful’, ‘the simple', '(all) the beautiful (things)' = GENERIC [~ le fer 'iron'] (II) Faire du beau avec du simple, ça c'est de l'art. ‘To make beautiful things (stuff) with simple things (stuff), that is what art is about’ = a (not very precise) portion of le beau, instantiated in a particular situation = SPECIFIC, indefinite [~ du fer 'some iron'] Peter Lauwers (III) Le beau [de + NP]: e. g. le beau de l'histoire ('the beaut. thing of the story') ‘what is beautiful [in NP], the beautiful thing [of NP] = SPECIFIC, definite [~ le fer de la pioche 'iron of the pick']

le beau (1) du beau (2) le beau de NP (3) Peter Lauwers

Remarks l l Type 2: in French, not in English, not in Spanish Type 3: one reading vs. 2 readings in Spanish (Lapesa 1984; Bosque & Moreno 1990; Villalba-Bartra. Kaufmann 2009: 821) § a 'partitive' / 'individuating' reading (3) Lo (más / *muy) pequeño de la casa (es el dormitorio) <the (most / very) small of the house (is the bedroom)> 'The smallest part of the house' § a degree / qualitative reading (4) Lo (*más / muy) caro de la casa me impresionó. (la casa = cara) <the (most / very) expensive of the house impressed me> 'The high degree of expensiveness' (5) lo tacaño de Ernesto; lo cariñoso de la niña (Google) *l’avare d’Ernesto; *le mignon de la fille Peter Lauwers (6) Me sorprendió lo cara que era la casa.

![I will not be dealing with. . l [+ human] NAs: (7) les pauvres I will not be dealing with. . l [+ human] NAs: (7) les pauvres](https://present5.com/presentation/22fa29dcfa76cde18a11cec2cba49b38/image-9.jpg)

I will not be dealing with. . l [+ human] NAs: (7) les pauvres ('the poor') l elliptic NPs § anaphoric NPs (8 a) • Tu voulais de la colle? Oui, j’en ai acheté de la bonne [colle]. • You wanted gluei? Yes, I of it have bought good [ti]. Peter Lauwers § NPs obtained by truncation (based on shared knowledge): (8 b) la (ville) capitale 'the capital'

![Productivity l Adj. + HUMAN N (9) le bavard ‘the talkative [person]’, l’aveugle ‘the Productivity l Adj. + HUMAN N (9) le bavard ‘the talkative [person]’, l’aveugle ‘the](https://present5.com/presentation/22fa29dcfa76cde18a11cec2cba49b38/image-10.jpg)

Productivity l Adj. + HUMAN N (9) le bavard ‘the talkative [person]’, l’aveugle ‘the blind [person]’, l’absent ‘the absent [person]’ [+HUMAN] → *du bavard, *de l’aveugle, *de l’absent (*partitive article) l Adj. + INANIMATE N (10) le faux ‘the false’, le vrai ‘the truth’ [–ANIMATE] → *les faux, *les vrais (*plural) l Some combine with both: (11) l’inconnu ‘the unknown’ Peter Lauwers

2. 2. The categorial status of NAs Are NAs full-fledged nouns? Criteria: (i) (ii) Peter Lauwers Determiners (+ number) Range of possible modifiers

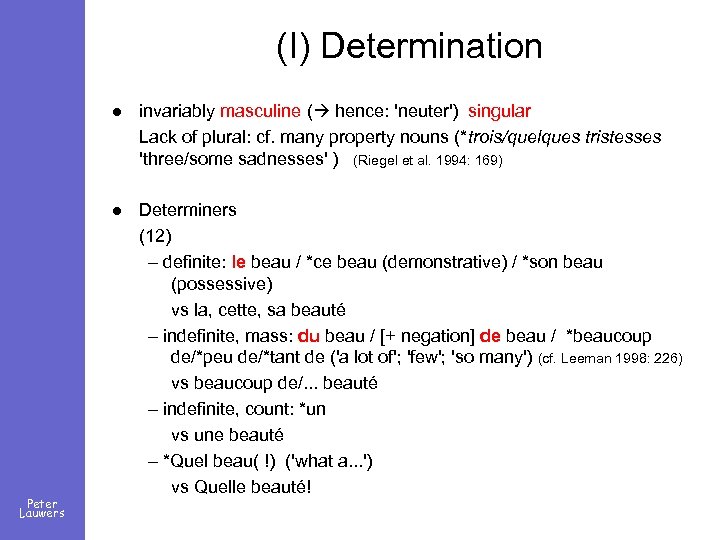

(I) Determination l l Peter Lauwers invariably masculine ( hence: 'neuter') singular Lack of plural: cf. many property nouns (*trois/quelques tristesses 'three/some sadnesses' ) (Riegel et al. 1994: 169) Determiners (12) – definite: le beau / *ce beau (demonstrative) / *son beau (possessive) vs la, cette, sa beauté – indefinite, mass: du beau / [+ negation] de beau / *beaucoup de/*peu de/*tant de ('a lot of'; 'few'; 'so many') (cf. Leeman 1998: 226) vs beaucoup de/. . . beauté – indefinite, count: *un vs une beauté – *Quel beau( !) ('what a. . . ') vs Quelle beauté!

![II. Modification ~ source category [ADJ] (i) Adverbs (of all kinds, except temporal/locative): (13) II. Modification ~ source category [ADJ] (i) Adverbs (of all kinds, except temporal/locative): (13)](https://present5.com/presentation/22fa29dcfa76cde18a11cec2cba49b38/image-13.jpg)

II. Modification ~ source category [ADJ] (i) Adverbs (of all kinds, except temporal/locative): (13) mettre sans cesse le facilement accessible en avant ‘to put incessantly forward what is easily accessible’ (ii) Subcategorized complements of the adjective (which are thus maintained !) (14) Construire un trajet de pensées porteuses de l’abolition d’un ordre établi, pour que l’humanité puisse être en mesure de s’émanciper, n’est-ce pas non plus fabriquer de l’utile à la société ? ‘To construct a collection of thoughts that support the abolition of the established order, in order to allow humanity to emancipate itself, isn’t it like producing things that are useful to society? ’ Adverb (i) + subcategorized PP (ii): Peter Lauwers (15) Il ne faut viser que le vraiment utile à la santé publique. (constructed example) ‘One should only aim at that which is really useful for public health. ’

![Modification ~ target category [N] (i) PP introduced by de: (16) Et le long Modification ~ target category [N] (i) PP introduced by de: (16) Et le long](https://present5.com/presentation/22fa29dcfa76cde18a11cec2cba49b38/image-14.jpg)

Modification ~ target category [N] (i) PP introduced by de: (16) Et le long plan de fin. . . souligne le dérisoire de cette histoire en ramenant les personnages à leur taille minuscule. ‘And the long zoom at the end. . . underlines the derisory character of this story by reducing the characters to their miniscule dimensions. ’ (ii) ungrounded restrictive relative clauses: (17) On n’est plus dans le superficiel qui prétend changer votre vie en 24 heures mais bien dans quelque chose de durable et d'accessible à tous. ‘This has nothing to do anymore with those superficial things that pretend to change your life within 24 hours but rather with something lasting and accessible to anyone. ’ Peter Lauwers

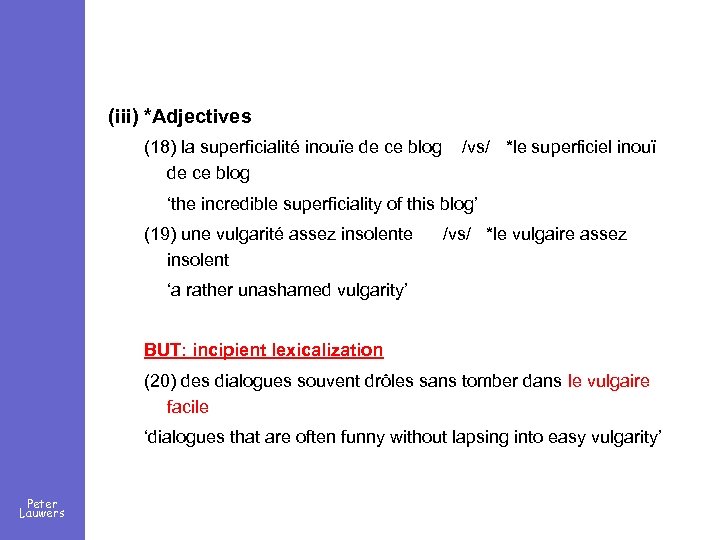

(iii) *Adjectives (18) la superficialité inouïe de ce blog /vs/ *le superficiel inouï de ce blog ‘the incredible superficiality of this blog’ (19) une vulgarité assez insolente /vs/ *le vulgaire assez insolent ‘a rather unashamed vulgarity’ BUT: incipient lexicalization (20) des dialogues souvent drôles sans tomber dans le vulgaire facile ‘dialogues that are often funny without lapsing into easy vulgarity’ Peter Lauwers

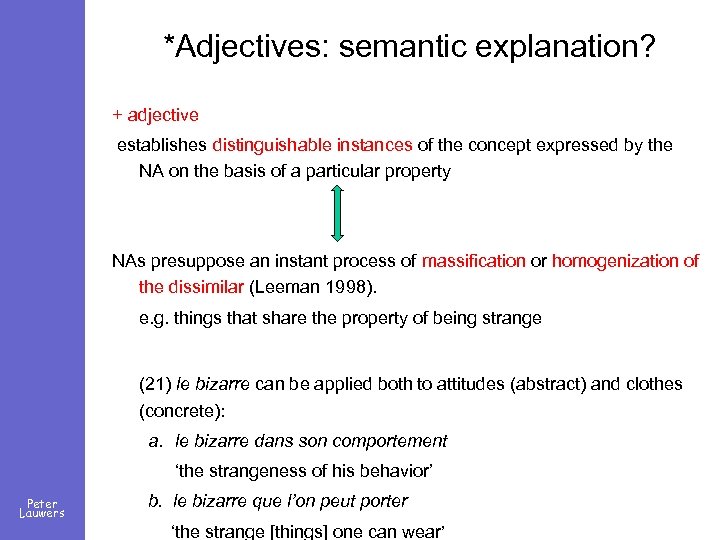

*Adjectives: semantic explanation? + adjective establishes distinguishable instances of the concept expressed by the NA on the basis of a particular property NAs presuppose an instant process of massification or homogenization of the dissimilar (Leeman 1998). e. g. things that share the property of being strange (21) le bizarre can be applied both to attitudes (abstract) and clothes (concrete): a. le bizarre dans son comportement ‘the strangeness of his behavior’ Peter Lauwers b. le bizarre que l’on peut porter ‘the strange [things] one can wear’

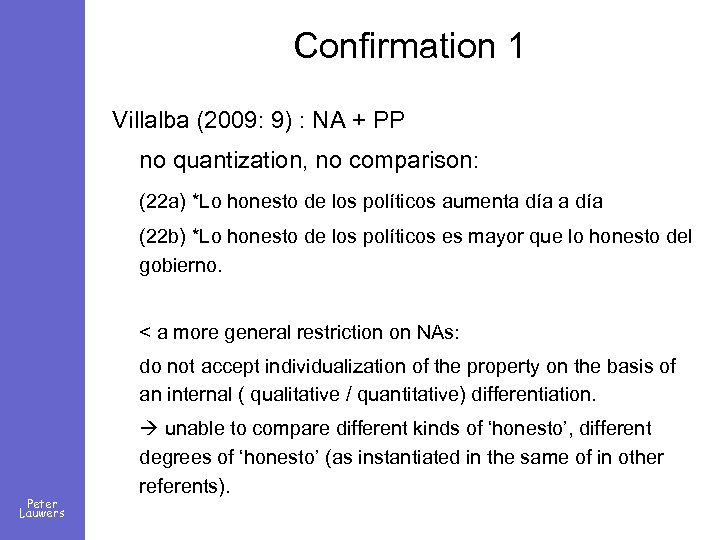

Confirmation 1 Villalba (2009: 9) : NA + PP no quantization, no comparison: (22 a) *Lo honesto de los políticos aumenta día (22 b) *Lo honesto de los políticos es mayor que lo honesto del gobierno. < a more general restriction on NAs: do not accept individualization of the property on the basis of an internal ( qualitative / quantitative) differentiation. Peter Lauwers unable to compare different kinds of ‘honesto’, different degrees of ‘honesto’ (as instantiated in the same of in other referents).

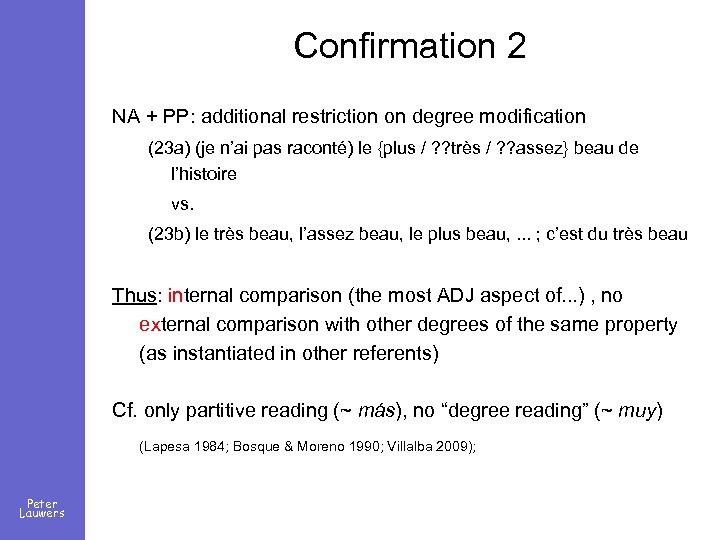

Confirmation 2 NA + PP: additional restriction on degree modification (23 a) (je n’ai pas raconté) le {plus / ? ? très / ? ? assez} beau de l’histoire vs. (23 b) le très beau, l’assez beau, le plus beau, . . . ; c’est du très beau Thus: internal comparison (the most ADJ aspect of. . . ) , no external comparison with other degrees of the same property (as instantiated in other referents) Cf. only partitive reading (~ más), no “degree reading” (~ muy) (Lapesa 1984; Bosque & Moreno 1990; Villalba 2009); Peter Lauwers

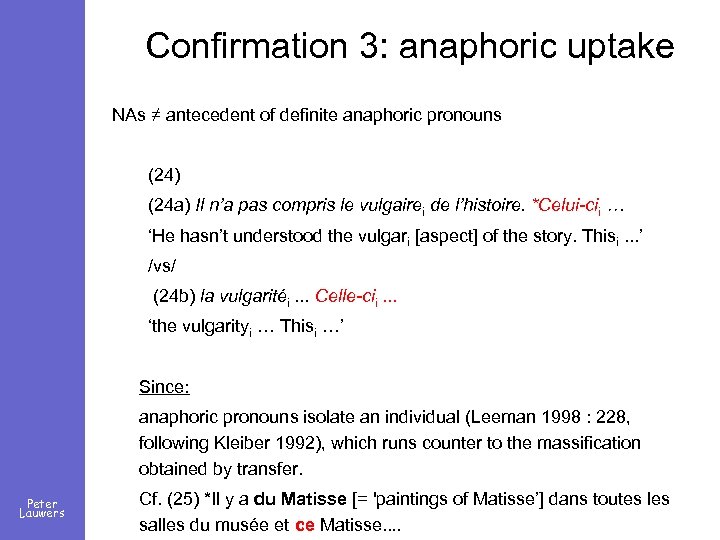

Confirmation 3: anaphoric uptake NAs ≠ antecedent of definite anaphoric pronouns (24) (24 a) Il n’a pas compris le vulgairei de l’histoire. *Celui-cii … ‘He hasn’t understood the vulgari [aspect] of the story. Thisi. . . ’ /vs/ (24 b) la vulgaritéi. . . Celle-cii. . . ‘the vulgarityi … Thisi …’ Since: anaphoric pronouns isolate an individual (Leeman 1998 : 228, following Kleiber 1992), which runs counter to the massification obtained by transfer. Peter Lauwers Cf. (25) *Il y a du Matisse [= 'paintings of Matisse’] dans toutes les salles du musée et ce Matisse. .

![Mixed patterns ~ ADJ/N (26) [Le plus sublime de cette répétition] était sans doute Mixed patterns ~ ADJ/N (26) [Le plus sublime de cette répétition] était sans doute](https://present5.com/presentation/22fa29dcfa76cde18a11cec2cba49b38/image-20.jpg)

Mixed patterns ~ ADJ/N (26) [Le plus sublime de cette répétition] était sans doute le début. ‘The most sublime part of this rehearsal was beyond any doubt the beginning. ’ (27) Les pigeons blasés, perchés sur le marché couvert, guettent la pourriture et [le trop mûr qu’on balance sur les trottoirs]. ‘the blasé pigeons, sitting on the roof of the indoor market place, on the lookout for rotten and for overripe things that are thrown on the footpath’ (F. Lasaygues, Vache noire, hannetons, 1985). Peter Lauwers

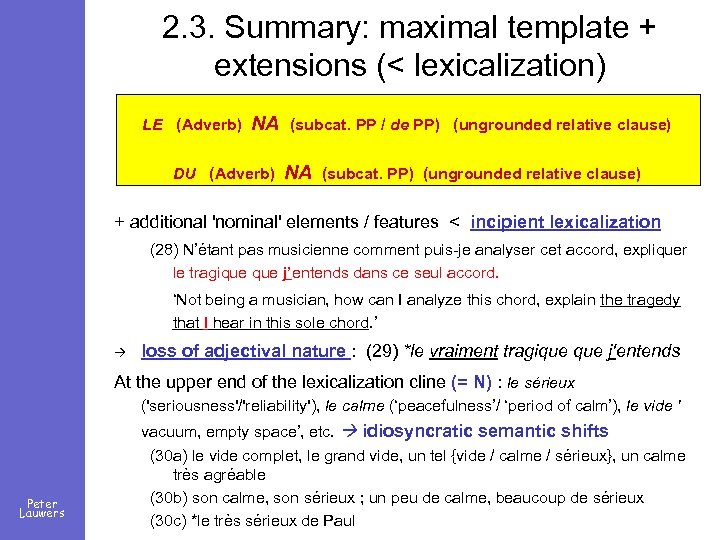

2. 3. Summary: maximal template + extensions (< lexicalization) LE (Adverb) NA (subcat. PP / de PP) (ungrounded relative clause) DU (Adverb) NA (subcat. PP) (ungrounded relative clause) + additional 'nominal' elements / features < incipient lexicalization (28) N’étant pas musicienne comment puis-je analyser cet accord, expliquer le tragique j’entends dans ce seul accord. ‘Not being a musician, how can I analyze this chord, explain the tragedy that I hear in this sole chord. ’ loss of adjectival nature : (29) *le vraiment tragique j'entends At the upper end of the lexicalization cline (= N) : le sérieux ('seriousness'/'reliability'), le calme (‘peacefulness’/ ‘period of calm’), le vide ' vacuum, empty space’, etc. idiosyncratic semantic shifts Peter Lauwers (30 a) le vide complet, le grand vide, un tel {vide / calme / sérieux}, un calme très agréable (30 b) son calme, son sérieux ; un peu de calme, beaucoup de sérieux (30 c) *le très sérieux de Paul

3. Problematic accounts Peter Lauwers

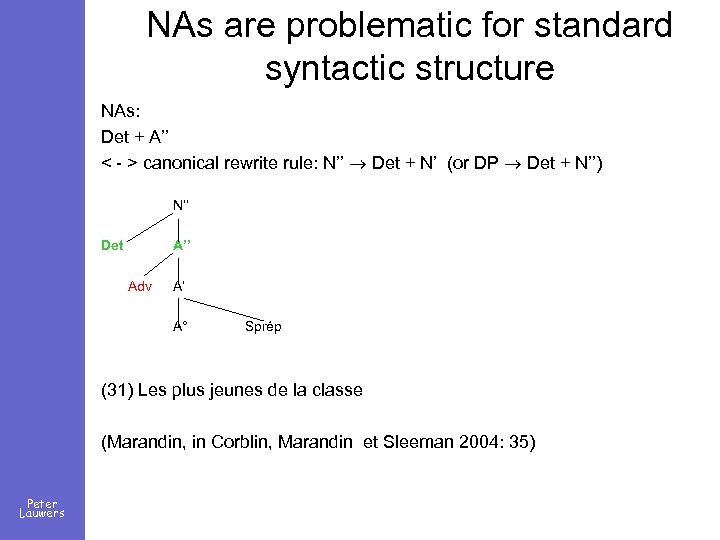

NAs are problematic for standard syntactic structure NAs: Det + A’’ < - > canonical rewrite rule: N’’ Det + N’ (or DP Det + N’’) N’’ Det A’’ Adv A’ A° Sprép (31) Les plus jeunes de la classe (Marandin, in Corblin, Marandin et Sleeman 2004: 35) Peter Lauwers

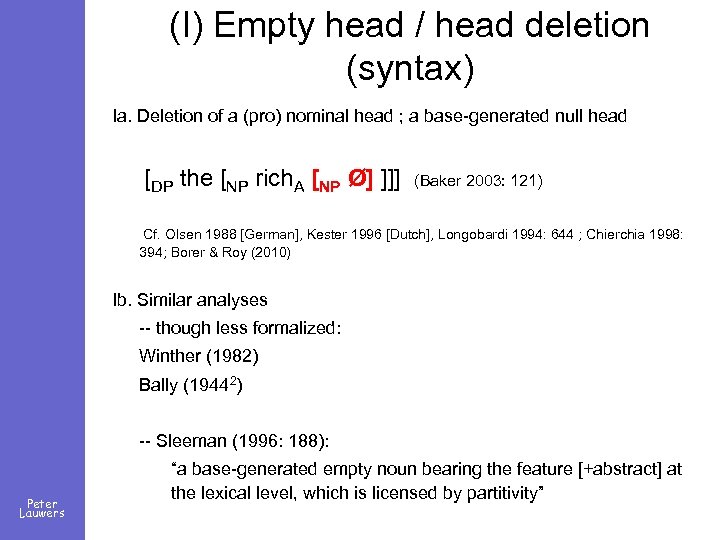

(I) Empty head / head deletion (syntax) Ia. Deletion of a (pro) nominal head ; a base-generated null head [DP the [NP rich. A [NP Ø] ]]] (Baker 2003: 121) Cf. Olsen 1988 [German], Kester 1996 [Dutch], Longobardi 1994: 644 ; Chierchia 1998: 394; Borer & Roy (2010) Ib. Similar analyses -- though less formalized: Winther (1982) Bally (19442) -- Sleeman (1996: 188): Peter Lauwers “a base-generated empty noun bearing the feature [+abstract] at the lexical level, which is licensed by partitivity”

![Null heads: empirical problems I. Which (pro)noun? A Noun? (32) ? le [truc] vulgaire Null heads: empirical problems I. Which (pro)noun? A Noun? (32) ? le [truc] vulgaire](https://present5.com/presentation/22fa29dcfa76cde18a11cec2cba49b38/image-25.jpg)

Null heads: empirical problems I. Which (pro)noun? A Noun? (32) ? le [truc] vulgaire / ? la [notion (de)] vulgaire / ? le [concept (de)] vulgaire ‘the vulgar thing’ / ‘the notion (of) vulgar’ / ‘the concept (of) vulgar’ A pronoun? (Winther 1982) (33) [+Human ANs]: ce + lui/elle + (qui est) malade ce […] malade [. . > un malade, les malades] <this him/her (who is) sick> → ‘this. . . sick [person]’ ‘a sick [person]’, ‘the sick’ But: What about [inanimate] ANs? (34) ce (+ ? ? ) + (qui est) beau *ce + beau (= ungrammatical !) Peter Lauwers II. Why no adjectives allowed?

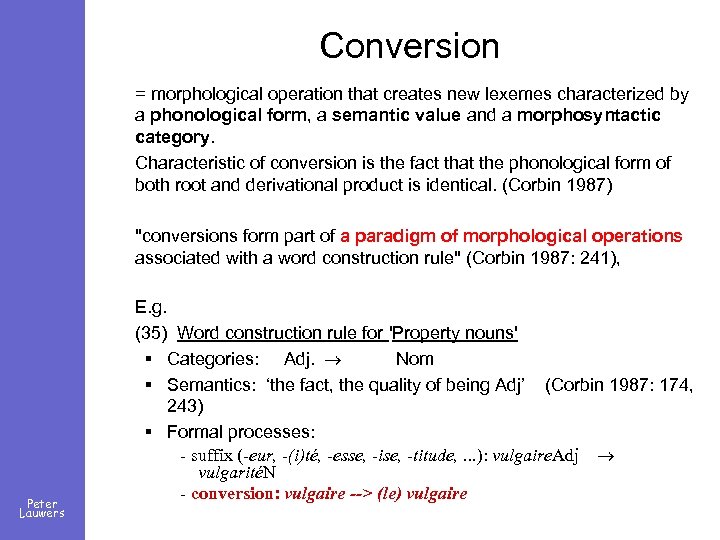

(II) Accounts based on full lexical recategorization: overview IIa. Morphological approaches l l "morphological derivation involves the systematic and massive acquisition of a categorial identity" (Kerleroux 1996: 189) traditional grammar: dérivation impropre (e. g. Nyrop 1908) French morphologists: conversion E. g. Fradin (2003): [le] bleu, [le] rouge, [le] calme, [le] sérieux. Corbin and Corbin, 1991 : 77; Kerleroux, 1996: 88 (although: Kerleroux, 1996: 204); 2000: 93; Apothéloz, 2002: 101; Fradin, 2003: 157 Peter Lauwers IIb. Lexicological approaches: relisting of lexical items (Lieber 2004) Cf. dictionaries: Entry ADJ. , then "masc. noun" IIIc. (pseudo-)syntactic approaches l standard treatment in Construction Grammar: a basically lexical mechanism (Fillmore & Kay 1995: Ch. 3): feature changing lexical constructions which modify the categorial specifications and “essentially create a new lexical item” (Fried & Östman 2004: 38) E. g. proper noun (Prague) > common noun (The Prague I remembered was completely different)

Conversion = morphological operation that creates new lexemes characterized by a phonological form, a semantic value and a morphosyntactic category. Characteristic of conversion is the fact that the phonological form of both root and derivational product is identical. (Corbin 1987) "conversions form part of a paradigm of morphological operations associated with a word construction rule" (Corbin 1987: 241), Peter Lauwers E. g. (35) Word construction rule for 'Property nouns' § Categories: Adj. Nom § Semantics: ‘the fact, the quality of being Adj’ (Corbin 1987: 174, 243) § Formal processes: - suffix (-eur, -(i)té, -esse, -ise, -titude, . . . ): vulgaire. Adj vulgaritéN - conversion: vulgaire --> (le) vulgaire

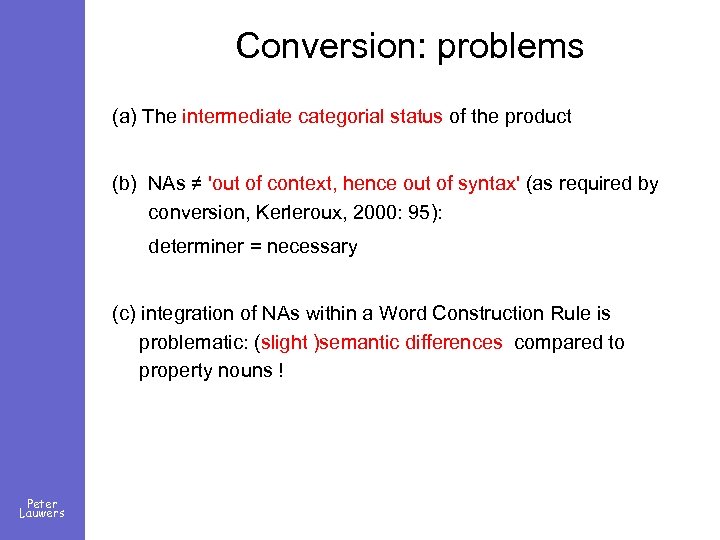

Conversion: problems (a) The intermediate categorial status of the product (b) NAs ≠ 'out of context, hence out of syntax' (as required by conversion, Kerleroux, 2000: 95): determiner = necessary (c) integration of NAs within a Word Construction Rule is problematic: (slight )semantic differences compared to property nouns ! Peter Lauwers

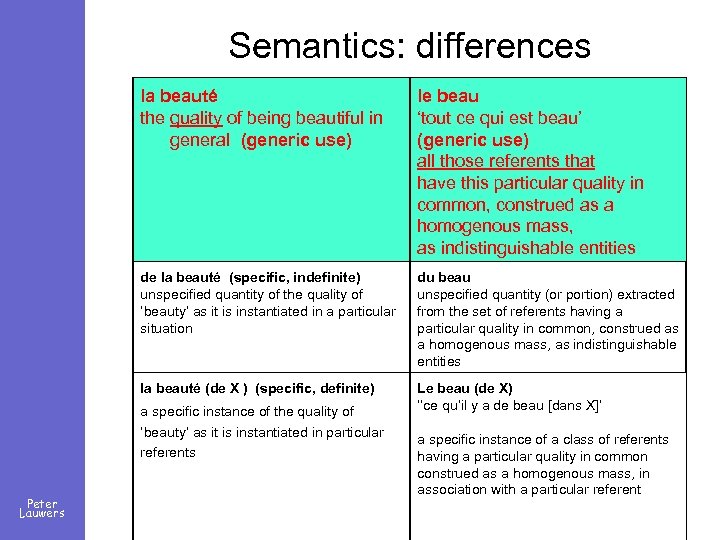

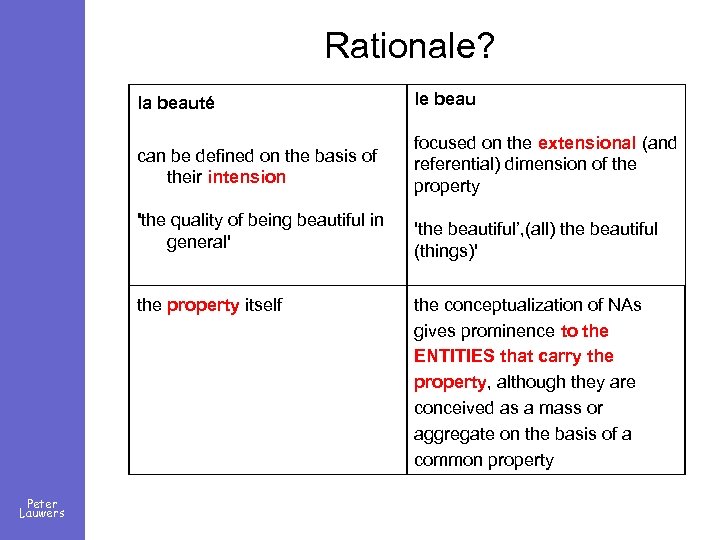

Semantics: differences la beauté the quality of being beautiful in general (generic use) le beau ‘tout ce qui est beau’ (generic use) all those referents that have this particular quality in common, construed as a homogenous mass, as indistinguishable entities de la beauté (specific, indefinite) unspecified quantity of the quality of ‘beauty’ as it is instantiated in a particular situation du beau unspecified quantity (or portion) extracted from the set of referents having a particular quality in common, construed as a homogenous mass, as indistinguishable entities la beauté (de X ) (specific, definite) Le beau (de X) ‘‘ce qu’il y a de beau [dans X]’ a specific instance of the quality of ‘beauty’ as it is instantiated in particular referents Peter Lauwers a specific instance of a class of referents having a particular quality in common construed as a homogenous mass, in association with a particular referent

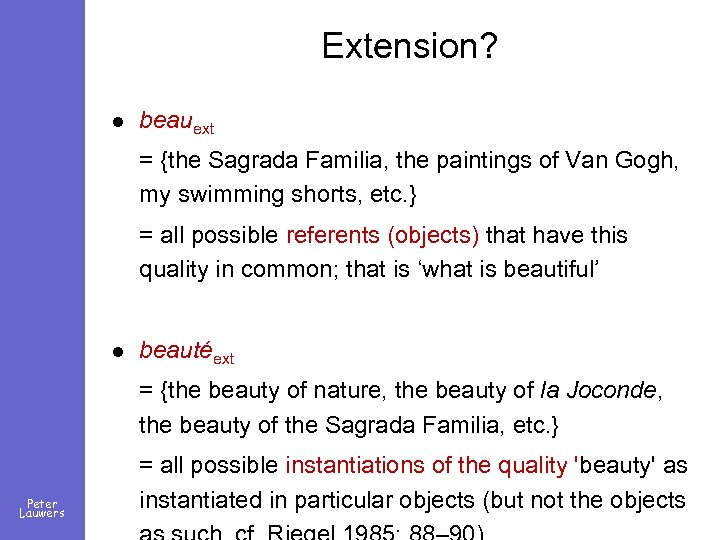

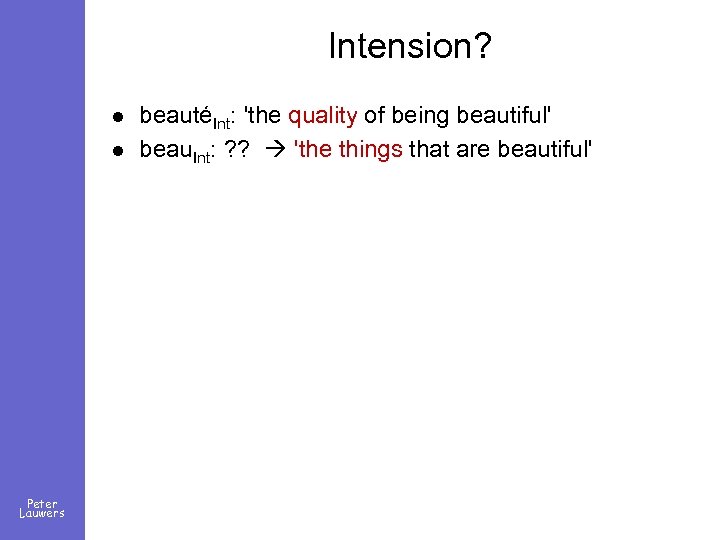

Extension? l beauext = {the Sagrada Familia, the paintings of Van Gogh, my swimming shorts, etc. } = all possible referents (objects) that have this quality in common; that is ‘what is beautiful’ l beautéext = {the beauty of nature, the beauty of la Joconde, the beauty of the Sagrada Familia, etc. } Peter Lauwers = all possible instantiations of the quality 'beauty' as instantiated in particular objects (but not the objects

Intension? l l Peter Lauwers beautéInt: 'the quality of being beautiful' beau. Int: ? ? 'the things that are beautiful'

Rationale? la beauté can be defined on the basis of their intension focused on the extensional (and referential) dimension of the property 'the quality of being beautiful in general' 'the beautiful’, (all) the beautiful (things)' the property itself Peter Lauwers le beau the conceptualization of NAs gives prominence to the ENTITIES that carry the property, although they are conceived as a mass or aggregate on the basis of a common property

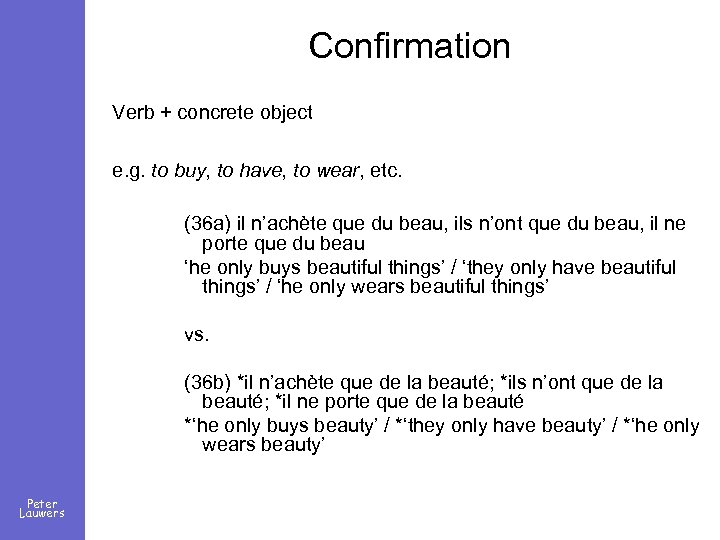

Confirmation Verb + concrete object e. g. to buy, to have, to wear, etc. (36 a) il n’achète que du beau, ils n’ont que du beau, il ne porte que du beau ‘he only buys beautiful things’ / ‘they only have beautiful things’ / ‘he only wears beautiful things’ vs. (36 b) *il n’achète que de la beauté; *ils n’ont que de la beauté; *il ne porte que de la beauté *‘he only buys beauty’ / *‘they only have beauty’ / *‘he only wears beauty’ Peter Lauwers

4. A syntactic analysis in terms of categorial mismatch Peter Lauwers

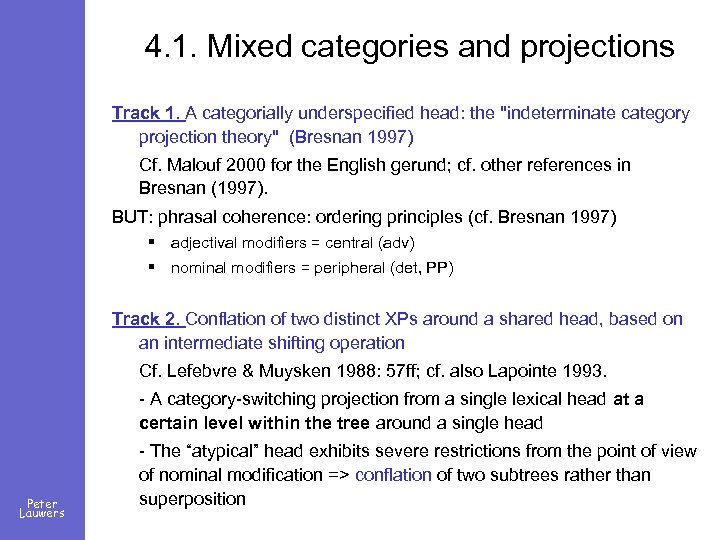

4. 1. Mixed categories and projections Track 1. A categorially underspecified head: the "indeterminate category projection theory" (Bresnan 1997) Cf. Malouf 2000 for the English gerund; cf. other references in Bresnan (1997). BUT: phrasal coherence: ordering principles (cf. Bresnan 1997) § adjectival modifiers = central (adv) § nominal modifiers = peripheral (det, PP) Track 2. Conflation of two distinct XPs around a shared head, based on an intermediate shifting operation Cf. Lefebvre & Muysken 1988: 57 ff; cf. also Lapointe 1993. - A category-switching projection from a single lexical head at a certain level within the tree around a single head Peter Lauwers - The “atypical” head exhibits severe restrictions from the point of view of nominal modification => conflation of two subtrees rather than superposition

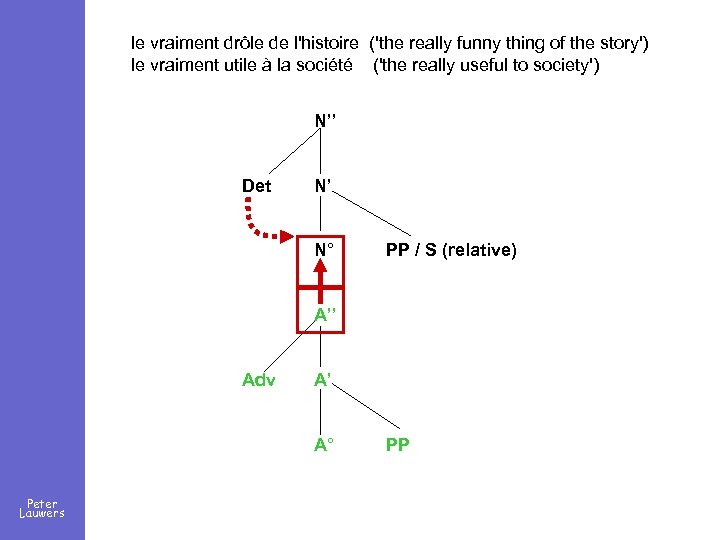

le vraiment drôle de l'histoire ('the really funny thing of the story') le vraiment utile à la société ('the really useful to society') N’’ Det N’ N° PP / S (relative) A’’ Adv A’ A° Peter Lauwers PP

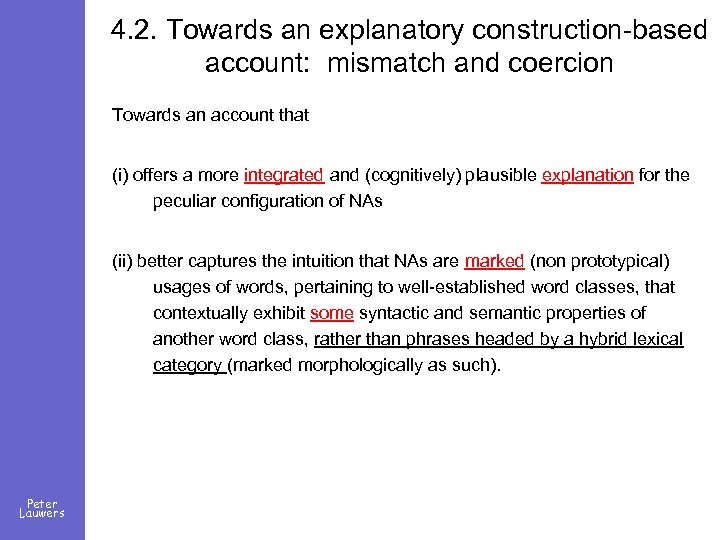

4. 2. Towards an explanatory construction-based account: mismatch and coercion Towards an account that (i) offers a more integrated and (cognitively) plausible explanation for the peculiar configuration of NAs (ii) better captures the intuition that NAs are marked (non prototypical) usages of words, pertaining to well-established word classes, that contextually exhibit some syntactic and semantic properties of another word class, rather than phrases headed by a hybrid lexical category (marked morphologically as such). Peter Lauwers

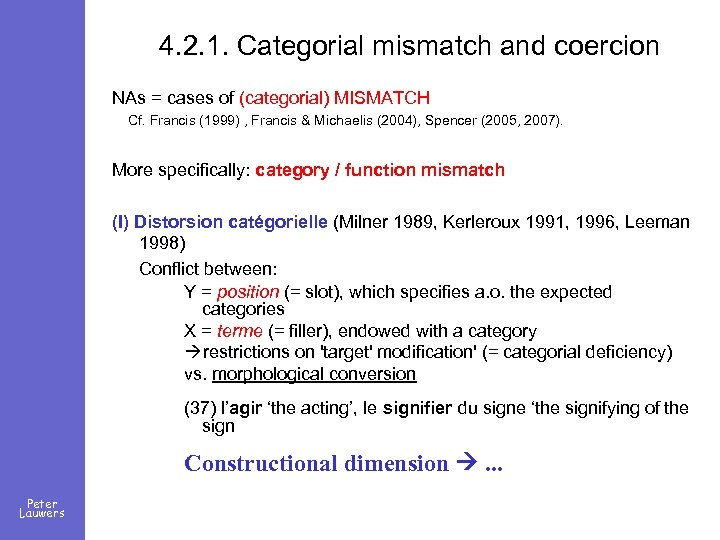

4. 2. 1. Categorial mismatch and coercion NAs = cases of (categorial) MISMATCH Cf. Francis (1999) , Francis & Michaelis (2004), Spencer (2005, 2007). More specifically: category / function mismatch (I) Distorsion catégorielle (Milner 1989, Kerleroux 1991, 1996, Leeman 1998) Conflict between: Y = position (= slot), which specifies a. o. the expected categories X = terme (= filler), endowed with a category restrictions on 'target' modification' (= categorial deficiency) vs. morphological conversion (37) l’agir ‘the acting’, le signifier du signe ‘the signifying of the sign Constructional dimension . . . Peter Lauwers

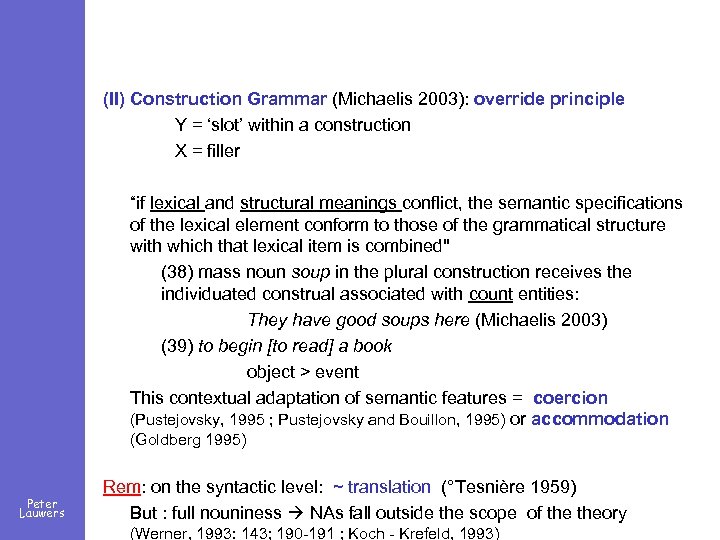

(II) Construction Grammar (Michaelis 2003): override principle Y = ‘slot’ within a construction X = filler “if lexical and structural meanings conflict, the semantic specifications of the lexical element conform to those of the grammatical structure with which that lexical item is combined" (38) mass noun soup in the plural construction receives the individuated construal associated with count entities: They have good soups here (Michaelis 2003) (39) to begin [to read] a book object > event This contextual adaptation of semantic features = coercion (Pustejovsky, 1995 ; Pustejovsky and Bouillon, 1995) or accommodation (Goldberg 1995) Peter Lauwers Rem: on the syntactic level: ~ translation (°Tesnière 1959) But : full nouniness NAs fall outside the scope of theory (Werner, 1993: 143; 190 -191 ; Koch - Krefeld, 1993)

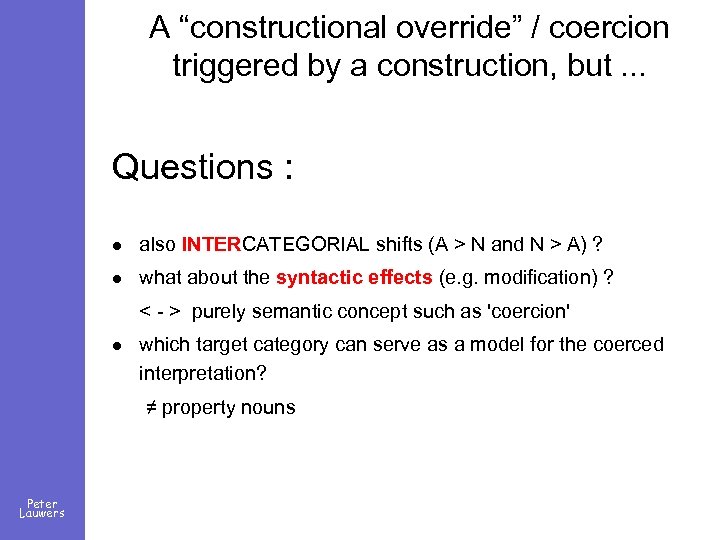

A “constructional override” / coercion triggered by a construction, but. . . Questions : l also INTERCATEGORIAL shifts (A > N and N > A) ? l what about the syntactic effects (e. g. modification) ? < - > purely semantic concept such as 'coercion' l which target category can serve as a model for the coerced interpretation? ≠ property nouns Peter Lauwers

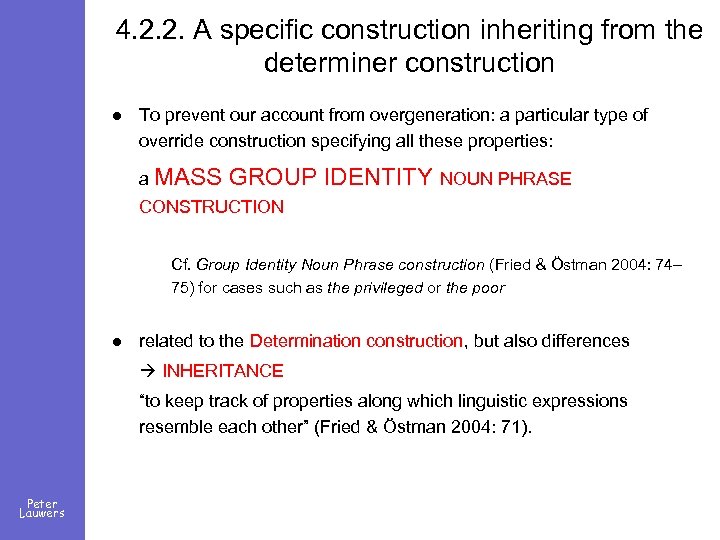

4. 2. 2. A specific construction inheriting from the determiner construction l To prevent our account from overgeneration: a particular type of override construction specifying all these properties: a MASS GROUP IDENTITY NOUN PHRASE CONSTRUCTION Cf. Group Identity Noun Phrase construction (Fried & Östman 2004: 74– 75) for cases such as the privileged or the poor l related to the Determination construction, but also differences INHERITANCE “to keep track of properties along which linguistic expressions resemble each other” (Fried & Östman 2004: 71). Peter Lauwers

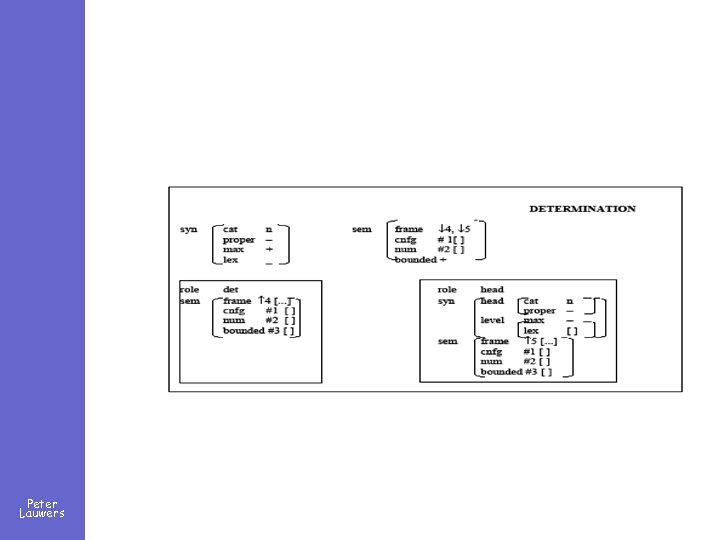

![Formalisme de C&G [Mass group identity NP] construction (Cx. G; ~ Fried & Östman Formalisme de C&G [Mass group identity NP] construction (Cx. G; ~ Fried & Östman](https://present5.com/presentation/22fa29dcfa76cde18a11cec2cba49b38/image-42.jpg)

Formalisme de C&G [Mass group identity NP] construction (Cx. G; ~ Fried & Östman 2004) Peter Lauwers

Peter Lauwers

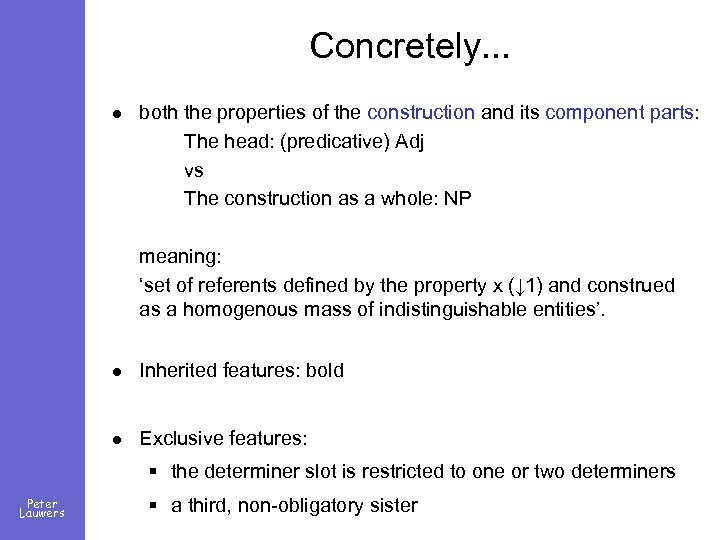

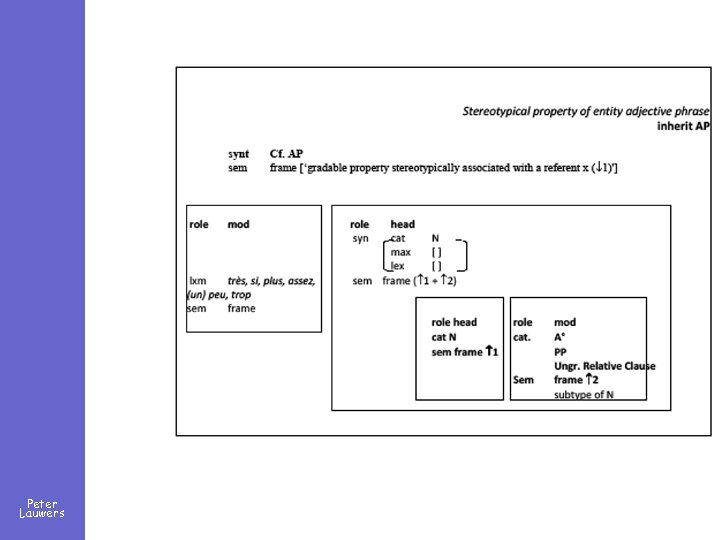

Concretely. . . l both the properties of the construction and its component parts: The head: (predicative) Adj vs The construction as a whole: NP meaning: ‘set of referents defined by the property x (↓ 1) and construed as a homogenous mass of indistinguishable entities’. l Inherited features: bold l Exclusive features: § the determiner slot is restricted to one or two determiners Peter Lauwers § a third, non-obligatory sister

5. Adjectivized nouns Peter Lauwers

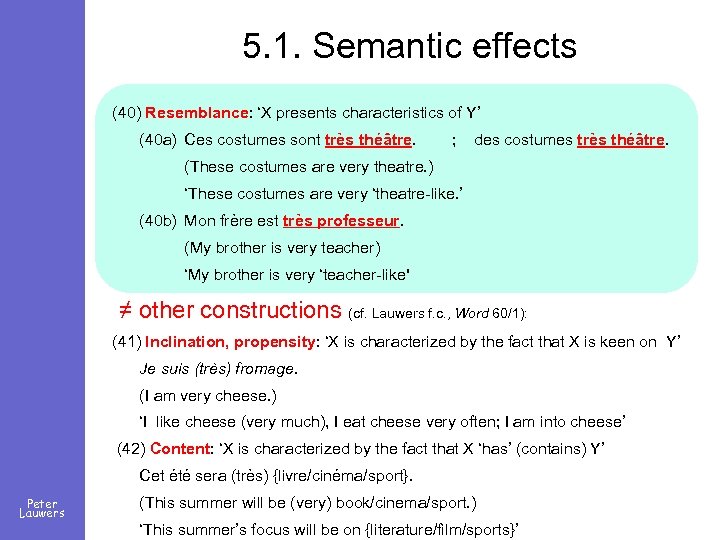

5. 1. Semantic effects (40) Resemblance: ‘X presents characteristics of Y’ (40 a) Ces costumes sont très théâtre. ; des costumes très théâtre. (These costumes are very theatre. ) ‘These costumes are very ‘theatre-like. ’ (40 b) Mon frère est très professeur. (My brother is very teacher) ‘My brother is very ‘teacher-like' ≠ other constructions (cf. Lauwers f. c. , Word 60/1): (41) Inclination, propensity: ‘X is characterized by the fact that X is keen on Y’ Je suis (très) fromage. (I am very cheese. ) ‘I like cheese (very much), I eat cheese very often; I am into cheese’ (42) Content: ‘X is characterized by the fact that X ‘has’ (contains) Y’ Cet été sera (très) {livre/cinéma/sport}. Peter Lauwers (This summer will be (very) book/cinema/sport. ) ‘This summer’s focus will be on {literature/film/sports}’

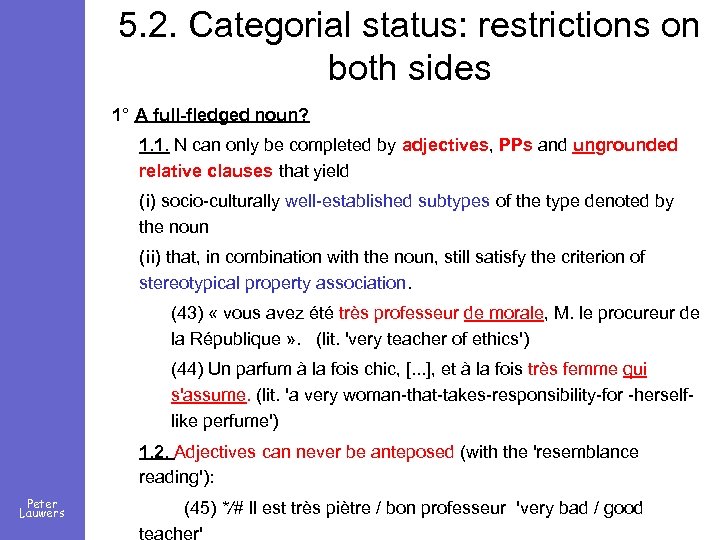

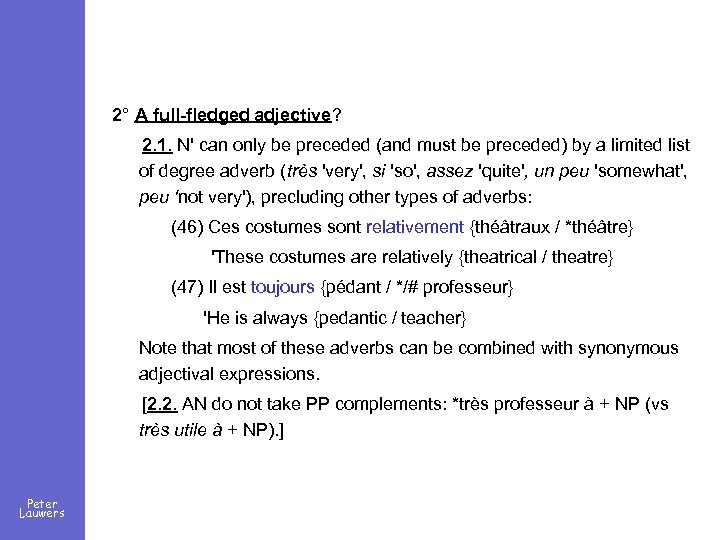

5. 2. Categorial status: restrictions on both sides 1° A full-fledged noun? 1. 1. N can only be completed by adjectives, PPs and ungrounded relative clauses that yield (i) socio-culturally well-established subtypes of the type denoted by the noun (ii) that, in combination with the noun, still satisfy the criterion of stereotypical property association. (43) « vous avez été très professeur de morale, M. le procureur de la République » . (lit. 'very teacher of ethics') (44) Un parfum à la fois chic, [. . . ], et à la fois très femme qui s'assume. (lit. 'a very woman-that-takes-responsibility-for -herselflike perfume') 1. 2. Adjectives can never be anteposed (with the 'resemblance reading'): Peter Lauwers (45) */# Il est très piètre / bon professeur 'very bad / good teacher'

2° A full-fledged adjective? 2. 1. N' can only be preceded (and must be preceded) by a limited list of degree adverb (très 'very', si 'so', assez 'quite', un peu 'somewhat', peu 'not very'), precluding other types of adverbs: (46) Ces costumes sont relativement {théâtraux / *théâtre} 'These costumes are relatively {theatrical / theatre} (47) Il est toujours {pédant / */# professeur} 'He is always {pedantic / teacher} Note that most of these adverbs can be combined with synonymous adjectival expressions. [2. 2. AN do not take PP complements: *très professeur à + NP (vs très utile à + NP). ] Peter Lauwers

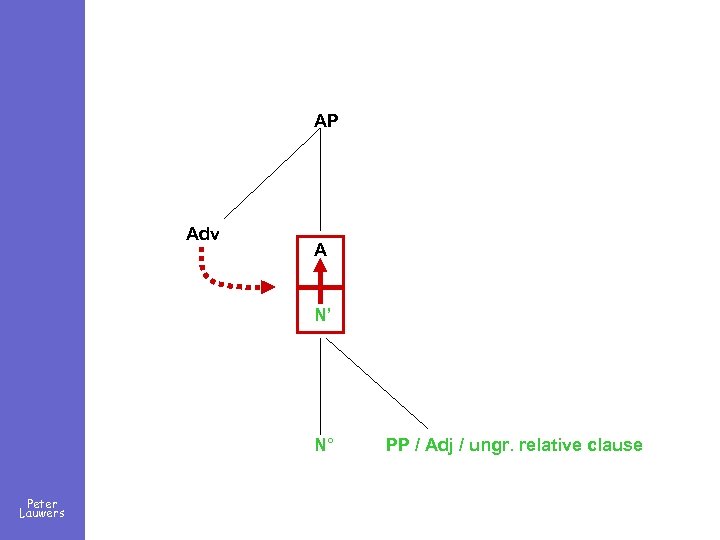

AP Adv A N’ N° Peter Lauwers PP / Adj / ungr. relative clause

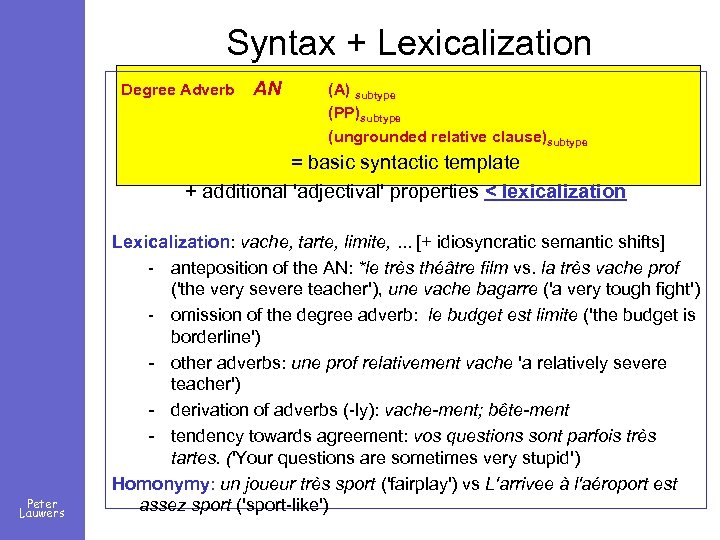

Syntax + Lexicalization Degree Adverb AN (A) subtype (PP)subtype (ungrounded relative clause)subtype = basic syntactic template + additional 'adjectival' properties < lexicalization Peter Lauwers Lexicalization: vache, tarte, limite, . . . [+ idiosyncratic semantic shifts] - anteposition of the AN: *le très théâtre film vs. la très vache prof ('the very severe teacher'), une vache bagarre ('a very tough fight') - omission of the degree adverb: le budget est limite ('the budget is borderline') - other adverbs: une prof relativement vache 'a relatively severe teacher') - derivation of adverbs (-ly): vache-ment; bête-ment - tendency towards agreement: vos questions sont parfois très tartes. ('Your questions are sometimes very stupid') Homonymy: un joueur très sport ('fairplay') vs L'arrivee à l'aéroport est assez sport ('sport-like')

Peter Lauwers

6. Conclusions l l due to the pressure exerted by a (syntactic) construction typical of another word class (= mismatch, constructional override) l without specific morphological marking (unlike gerunds, infinitives, etc. ) l [in Cx. G] a formalism based on a specific (shifting? ) construction that inherits features from a default target construction, to capture both restrictions and meaning effects, in order to prevent overgeneration. l Peter Lauwers forms with mixed morphological, semantic and syntactic properties with regard to the traditional word classes This target construction serves a model (attraction) l the remaining gap to the target category can be bridged through a gradient process of lexicalization

References Folia Linguistica (2008) “The nominalization of adjectives in French: from morphological conversion to categorial mismatch”, p. 135 -176. Word (f. c. ) "Copular constructions and adjectival uses of bare nouns in French: a case of syntactic recategorization? " l l l l Peter Lauwers Apothéloz, D. , 2002. La construction du lexique français: principes de morphologie dérivationnelle. Ophrys, Gap. Bally, Ch. , 19442. Linguistique générale et linguistique française. Francke, Bern. Borer, H. & Roy, I. 2010. “The name of the adjective”. In P. Cabredo Hofherr & O. Matushansky (eds). Adjectives. Formal analyses in syntax and semantics. 85 -114. Bresnan, J. , 1997. Mixed categories as head sharing constructions. In: M. Butt, T. Holloway King, Proceedings of the LFG 97 Conference. CSLI publications. Corbin, D. , 1987. Morphologie dérivationnelle et structuration du lexique. Niemeyer, Tübingen. Corbin, D. , Corbin, P. , 1991. Un traitement unifié du suffixe –er(e). Lexique 10, 61 -145. Corblin, F. , 1995. Les formes de reprise dans le discours. Anaphores et chaînes de référence. Presses universitaires de Rennes, Rennes. Corblin, F. , 1999. Les références mentionnelles: le premier, le dernier, celui-ci. In: A. Mettouchi, H. Quintin (eds), La référence. Statut et processus. Travaux linguistiques du CERLICO. Presses universitaires de Rennes, pp. 107123. Corblin, F. , Marandin, J. -M. , Sleeman, P. 2004. Nounless determiners, In: Handbook of French Semantics, CSLI Publications, pp. 23 -41. Cori, M. , Marandin, J. -M. , 1997. Un calcul de préférence en syntaxe. Revue Internationale de Systémique 11, 49 -67. Fillmore, Ch. , Kay, P. , 1993. Construction grammar coursebook. Unpublished ms. , Department of Linguistics, University of California, Berkeley. Fradin, B. , 2003. Nouvelles approches en morphologie. P. U. F. , Paris. Francis, E. J. , 1999. Variation within lexical categories. Ph. D thesis, University of Chicago. [UMI Dissertation Abstracts] Francis, E. J. , Michaelis, L. A. , 2004. Mismatch. Form-Function Incongruity and the Architecture of Grammar. CSLI Publications, Stanford. Fried, M. , Östman, J. -O. , 2004. Construction grammar: A thumbnail sketch. In: M. Fried, Östman, J. O. (eds), Construction Grammar in a Cross-Language Perspective. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: Benjamins, pp. 11 -86.

l l l l Peter Lauwers Goodman, N. , 1951. The structure of appearance. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA. Kerleroux, F. , 1996. La coupure invisible. Etudes de syntaxe et de morphologie. Presses universitaires du Septentrion, Paris. Kerleroux, F. , 2000. Identification d’un procédé morphologique: la conversion. Faits de Langue 14, 89 -100. Kester, E. -P. 1996. The Nature of Adjectival Inflection. Ph. D Dissertation, University of Utrecht. Kleiber, G. , 1992. À propos de du Mozart: une énigme référentielle. In: G. Gréciano, G. Kleiber (eds), Systèmes interactifs. Mélanges en l’honneur de Jean David. Klincksieck, Metz et Paris, pp. 241 -256. Koch, P. , Krefeld, T. , 1993. Gibt es Translationen? . Zeitschrift für Romanische Philologie 109, 149 -166. Lambertz, T. , 1995. Translation et dépendance. In: F. Madray-Lesigne, J. Richard-Zappella (eds), Lucien Tesnière aujourd'hui, Peeters, Louvain/Paris, pp. 221 -228. Leeman, D. , 1998. C’est du joli ! Remarques sur un emploi d’adjectif dit « substantivé » . In: A. Boone, D. Leeman (eds), Du percevoir au dire. Hommages à André Joly. L’Harmattan, Paris, pp. 221 -234. Lieber, R. , 2004. Morphology and lexical semantics. CUP, Cambridge. Marandin, J. -M. , 1997. Pas d’entité sans identité”: l’analyse des groupes nominaux DET + A. In: B. Fradin, J. -M. Marandin (eds), Mot et grammaires. Didier Erudition, Paris, pp. 129 -164. Michaelis, L. A. , 2003. Word meaning, sentence meaning, and syntactic meaning. In: H. Cuyckens – R. Dirven, J. R. Taylor (eds), Cognitive Approaches to Lexical Semantics. Berlin/New York: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 163 -209. Milner, J. -Cl. , 1989. Introduction à une science du langage. Seuil, Paris. Newmeyer, F. , 2004. Theoretical Implications of Grammatical Category – Grammatical Relation Mismatches. In: Francis, E. J. , Michaelis, L. A (eds), Mismatch. Form-Function Incongruity and the Architecture of Grammar. CSLI Publications, Stanford, pp. 149 -178.

l l l l l Nyrop, K. , 1908. Grammaire historique de la langue française. T. III. Gyldendal, Copenhague. Olsen, S. , 1988. Das « substantivierte » Adjektiv im Deutschen und Englischen: Attribuierung vs. syntaktische « Substantivierung » . Folia Linguistica 22, 337 -372. Pustejovsky, J. , 1995. The generative lexicon. MIT press, Cambridge, MA. Pustejovsky, J. , Bouillon, P. , 1995. Aspectual coercion and logical polysemy. Journal of Semantics 12(2), 133 -162. Rey-Debove, J. , 1997. Le métalangage. Etude linguistique du discours sur le langage. Colin, Paris. Riegel, M. , 1985. L’adjectif attribut. P. U. F, Paris. Riegel, M. , Pellat, Chr. , Rioul, R. , 1994. Grammaire méthodique du français. P. U. F, Paris. Sleeman, P. 1996. Licensing Empty Nouns in French. Ph. D Dissertation, University of Amsterdam. Spencer, A. 2005. Towards a typology of ‘mixed categories’. In Orgun & Sells (eds. ) Morphology and the Web of Grammar. CSLI, 95— 138. Tesnière, L. , 1959. Elements de linguistique structurale. Klincksieck, Paris. l Villalba, X. 2009. “Definite Adjective Nominalizations in Spanish”. In: M. T. Espinal, M. Leonetti & L. Mc. Nally (eds. ), Proceedings of the IV Nereus International Workshop “Definiteness and DP Structure in Romance Languages”. Arbeitspapier 124. Fachbereich Sprachwissenschaft, Universität Konstanz, 139 -153. l Villalba, X & Bartra-Kaufmann, A. 2009. "Predicate focus fronting in the Spanish determiner phrase”. Lingua 120. 4: 819 -849. Werner, E. , 1993. Translationstheorie und Dependenzmodell. Kritik und Reinterpretation des Ansatzes von Lucien Tesnière. Francke, Tübingen. Wilmet, M. , 2003. Grammaire critique du français. Duculot, Louvain-la-Neuve. Winther, A. , 1982. Un cas de dérivation non-affixale: la substantivation des adjectifs en français. Folia linguistica 16, 345 -364. Winther, A. , 1996. Un petit point de morpho-syntaxe: la formation des adjectifs substantivés en français. L’information grammaticale 68, 42 -46. l l Peter Lauwers

22fa29dcfa76cde18a11cec2cba49b38.ppt