6f581297178b393114137fe214617291.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 25

Berlin‘s Prenzlauer Berg: from “Careful Urban Renewal“ to Gentrification 29. 10. 2010, Matthias Bernt

… Gentrification as a perpetual motion machine? Slide 2 of 18 Footer

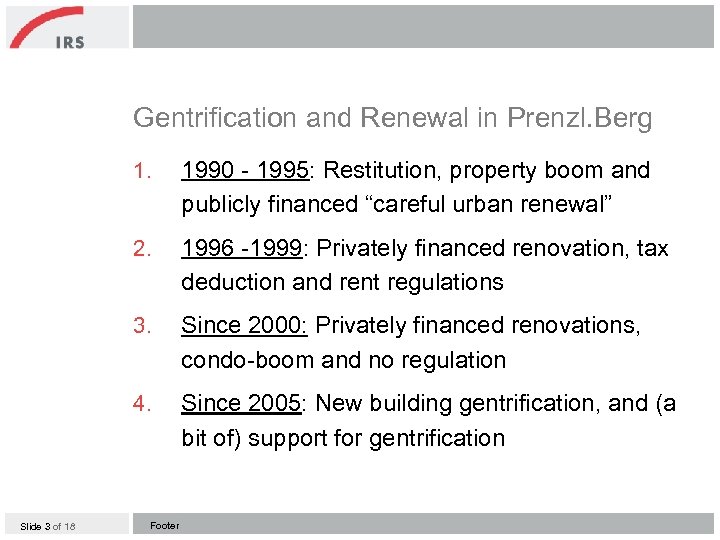

Gentrification and Renewal in Prenzl. Berg 1. 2. 1996 -1999: Privately financed renovation, tax deduction and rent regulations 3. Since 2000: Privately financed renovations, condo-boom and no regulation 4. Slide 3 of 18 1990 - 1995: Restitution, property boom and publicly financed “careful urban renewal” Since 2005: New building gentrification, and (a bit of) support for gentrification Footer

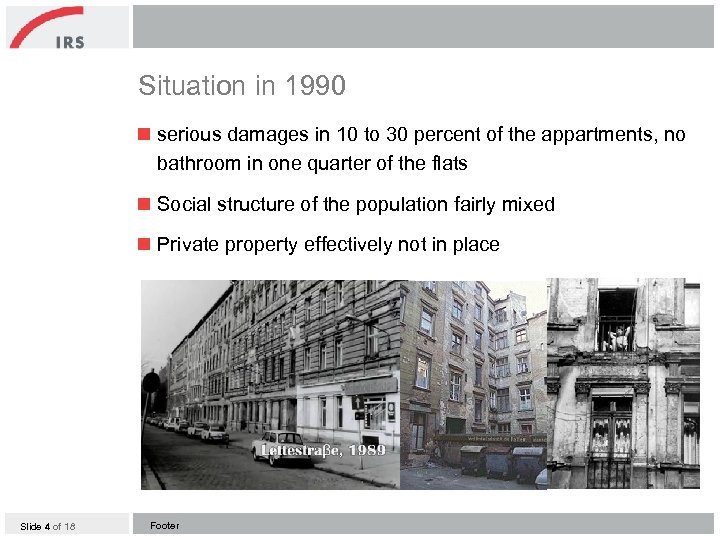

Situation in 1990 n serious damages in 10 to 30 percent of the appartments, no bathroom in one quarter of the flats n Social structure of the population fairly mixed n Private property effectively not in place Slide 4 of 18 Footer

Situation in 1990 n Strong tradition of Berlin as a „Tenant City“ n Welfarist Urban Renewal in West Berlin since 1964, „Reconstruction“ in East Berlin since 1972 – both implying state control on rents n Squatters movements in the 1980 ies, leading to „Careful Urban Renewal“ n „Wir Bleiben Alle“ neighbour- hood movements in East Berlin the early 1990 ies Slide 5 of 18 Footer

New challenges for Renewal n Loss of importance as a “showcase of the West”; reduction of federal support n At the same time, “Largest Urban Renewal Area of Europe”, strong need for additional ressources to deal with housing problems in East-Berlin n Speculative real estate bubble, inflating house prices n Restitution led to numerous problems, including absantee landlords, a fueling of speculative activities and, in the long run, a professionalization and commercialization of ownership structures Slide 6 of 18 Footer

1990 -1995: Publ. financed „Careful Urban Renewal“ n 1993: declaration of the first „Urban Renewal Areas“ in East-Berlin, enacting a series of regulations on building activities and sales prices n Acceptance of the idea that the state would set the agenda for the renewal process and regulate it in a way that wold be in line with the needs of the existing population Slide 7 of 18 Footer

„Guiding Principles of Careful Urban Renewal“ (1993) „… 3. The renovations must be oriented on the needs of the inhabitants (“Betroffene“). The renewal measures will be organized in a socially responsible way. (…) In the case of privately financed renovations, it is imperative to avoid negative consequences that would collide with the social intentions of urban renewal, as well as the preservation of the social structure. Recognising differences among the areas, it is mandatory to avoid: the displacement of low-income groups, the acceleration of processes of residential segregation and the implied consequen-ces of an unbalanced development and a destabilisation of the population in the affected areas, as well as individual hardships for adaptable households. In principle, the urban renewal should allow the inhabitants to stay in the area. The rent increa-ses shall therefore be oriented on the capacities of the inhabitants. “ Slide 8 of 18 Footer

„Guiding Principles of Careful Urban Renewal“ (1993) „… 3. The renovations must be oriented on the needs of the inhabitants (“Betroffene“). The renewal measures will be organized in a socially responsible way. (…) In the case of privately financed renovations, it is imperative to avoid negative consequences that would collide with the social intentions of urban renewal, as well as the preservation of the social structure. Re-cognising differences among the areas, it is mandatory to avoid: the displacement of low-income groups, the acceleration of processes of residential segregation and the implied consequences of an unbalanced development and a destabilisation of the population in the affected areas, as well as individual hardships for adaptable households. In principle, the urban renewal should allow the inhabitants to stay in the area. The rent increases shall therefore be oriented on the capacities of the inhabitants. “ Slide 9 of 18 Footer

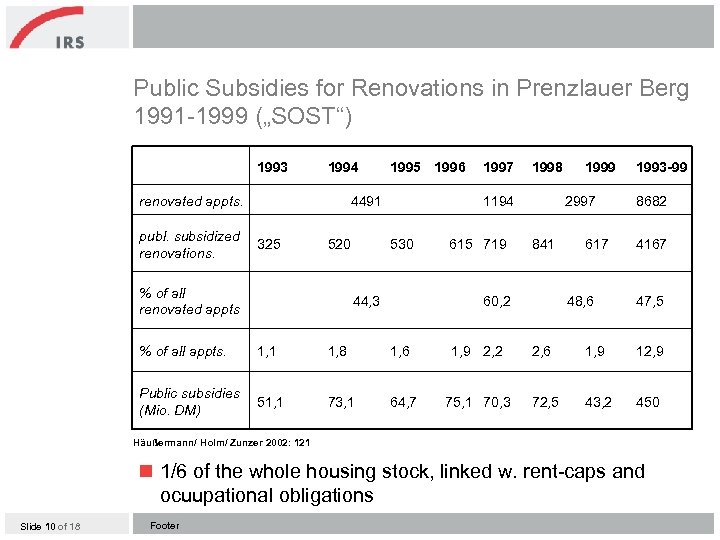

Public Subsidies for Renovations in Prenzlauer Berg 1991 -1999 („SOST“) 1993 1994 renovated appts. publ. subsidized renovations. 1995 1996 4491 325 520 % of all renovated appts 1997 1998 1194 530 44, 3 615 719 1999 2997 841 60, 2 617 48, 6 1993 -99 8682 4167 47, 5 % of all appts. 1, 1 1, 8 1, 6 1, 9 2, 2 2, 6 1, 9 12, 9 Public subsidies (Mio. DM) 51, 1 73, 1 64, 7 75, 1 70, 3 72, 5 43, 2 450 Häußermann/ Holm/ Zunzer 2002: 121 n 1/6 of the whole housing stock, linked w. rent-caps and ocuupational obligations Slide 10 of 18 Footer

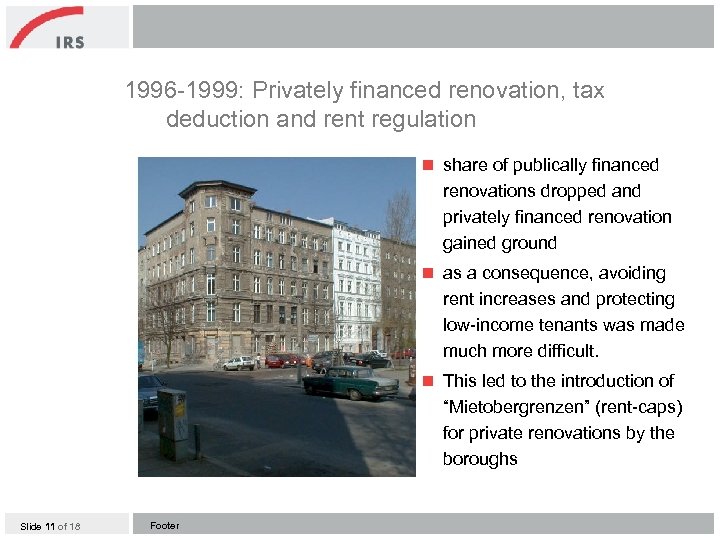

1996 -1999: Privately financed renovation, tax deduction and rent regulation n share of publically financed renovations dropped and privately financed renovation gained ground n as a consequence, avoiding rent increases and protecting low-income tenants was made much more difficult. n This led to the introduction of “Mietobergrenzen” (rent-caps) for private renovations by the boroughs Slide 11 of 18 Footer

1995 -2003: „Rent caps“ for Renovations n Based on specific permissions for building activities, included in the legal code for „Urban Renewal Areas“ n Limited the rent increase after renvoations n Several weaknesses in practice: n protection for tenants was very much dependent on their abilities to use the regulations, n no impact on rents for new contracts n Moreover, rent-caps were strongly contested. Thus, their duration was left unclear until 1998 and varied from borough to borough Slide 12 of 18 Footer

1990 -1995: Tax deductions n Financial base of most private renovations: special depreciation possibilities enshrined in the federal Fördergebietsgesetz n Estimated amount for Prenzl. Berg 700 Mio DM (until 1999) n Subsidies were not linked to any obligations, besides renovation activities n Tax-gvieaways made refurbishing old housing extremely lucrative for investors with a large taxable income, since the ‘costs’ of investment could be transformed into tax savings for the partners involved Slide 13 of 18 Footer

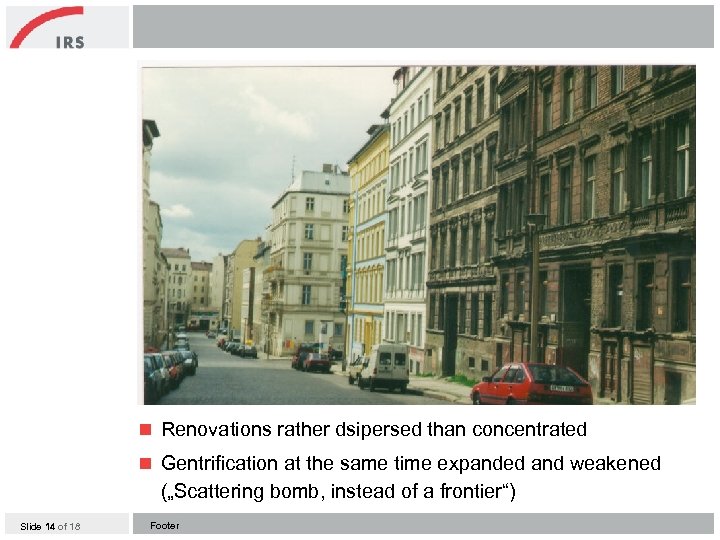

1996 1999 n Renovations rather dsipersed than concentrated n Gentrification at the same time expanded and weakened („Scattering bomb, instead of a frontier“) Slide 14 of 18 Footer

Since 2000: Condo-Boom and no regulations n Public subsidies abolished by new red-red government n Rent-caps declared illegal by Federal Adminstrative Court n Oppurtunities for tax-deductions considerably reduced Increasing importance of renovations, based on the transformation of rental housing into single-ownership. Slide 15 of 18 Footer

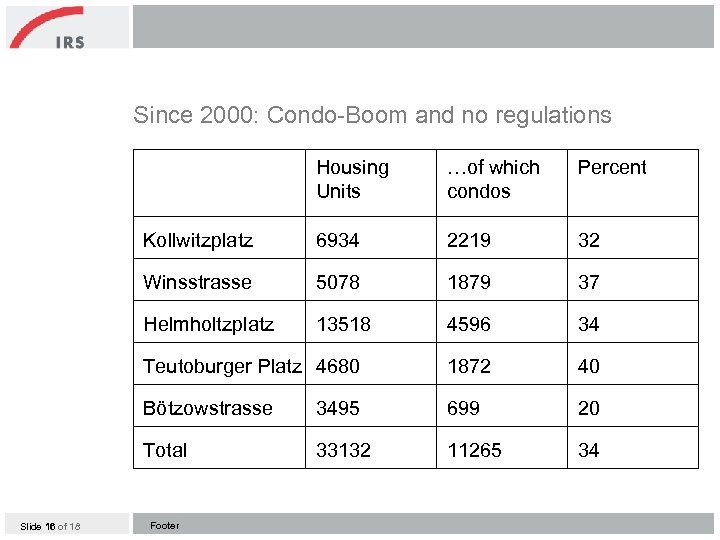

Since 2000: Condo-Boom and no regulations Housing Units Percent Kollwitzplatz 6934 2219 32 Winsstrasse 5078 1879 37 Helmholtzplatz 13518 4596 34 Teutoburger Platz 4680 1872 40 Bötzowstrasse 3495 699 20 Total Slide 16 of 18 …of which condos 33132 11265 34 Footer

Since 2000: Condo-Boom and no regulations n Based on the sale of still inhabited condos, before the start of renovation activities n Problems include: loss of security of tenure, change of the shape of appts. , high pressure on existing tenants n Remaining tenants‘ rate reduced to < 25 percent Slide 17 of 18 Footer

Since 2005: New Building Gentrification n Construction Boom for New Building Luxury Estates n Seven Projects with more than 500 appt. in Prenzlauer Berg alone, focussing on very affluent buyers n Prices vary between 2. 500 and 10. 000 Euro/ m 2 n Supported by Public Policies through reduced prices on public land architectural competitions n Moreover, after 2012, the status as an „Urban Renewal Area“ will be abolished for the majority of quarters, again considerably reducing legal oppurtunities for intervention Slide 18 of 18 Footer

Slide 19 of 18 Footer

Slide 20 of 18 Footer

Slide 21 of 18 Footer

Careful Urban Renewal 2. 0 Interview with Berlin‘s Mayor Wowereit in Berliner Zeitung (08. 14. 2010) Let‘s talk about gentrification. In some neighbourhoods in Prenzlauer Berg, 80 percent of the poulation have been displaced since the beginning of the 1990 ies. I‘m not telling anybody that he has to stay in his appartment and is not allowed to move to a suburb. Where one wants to live is his free decision. Not if you are displaced by high rents. Well, I wouldn‘t generalize on this issue. My feeling is that Berliners don‘t allow themselves to be displaced. … Slide 22 of 18 Footer

Careful Urban Renewal 2. 0 Does gentrification belong to a metropolis? . . of course, one needs to have an eye on recent developments. In this context, … we need to care about neighbourhoods which are characterized by a social lopsidedness. …Here we need to counteract problematic developments and take care that people with a decent income stay, or move into these neighbourhoods. This is not gentrification. It is a pure necessity, if you want to stabilize and upgrade these neighbourhoods. Slide 23 of 18 Footer

Conclusions n Whereas public subsidies played a main role in the 1980 ies and early 1990 ies, they were gradually replaced by “softer” forms of regulation and intervention into the housing market was completely given up n Altogether, the more gentrification became a problem, the more state intervention was downsized and control shifted to the market n Yet, this change did not a happen as a structural result of anonymous market forces, but as an outcome of changes in public policies. Slide 24 of 18 Footer

Conclusions n Gentrification is fundamentally a political process. Market forces cannot work without a regulatory framework – and how this is designed depends on political decisions n The resources to push or prevent gentrification are contingent; they are not built into the essence of urban development – but are a matter of political struggle Slide 25 of 18 Footer

6f581297178b393114137fe214617291.ppt