37245cedd6f871efe37b023c4db64779.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 17

Benefits of Developing Countries Access to the Scientific Public Domain: Clemente Forero-Pineda Universidad de los Andes, Universidad del Rosario Abelardo Duarte-Rey Universidad de los Andes Bogota, Colombia

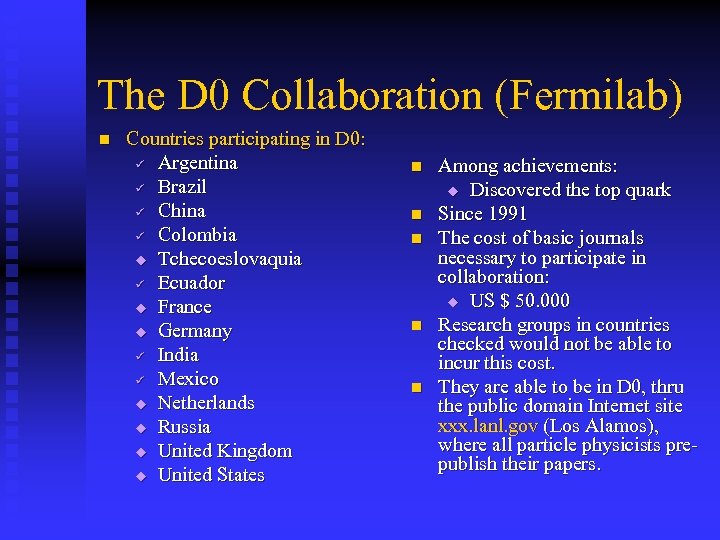

The D 0 Collaboration (Fermilab) n Countries participating in D 0: ü Argentina ü Brazil ü China ü Colombia u Tchecoeslovaquia ü Ecuador u France u Germany ü India ü Mexico u Netherlands u Russia u United Kingdom u United States n n n Among achievements: u Discovered the top quark Since 1991 The cost of basic journals necessary to participate in collaboration: u US $ 50. 000 Research groups in countries checked would not be able to incur this cost. They are able to be in D 0, thru the public domain Internet site xxx. lanl. gov (Los Alamos), where all particle physicists prepublish their papers.

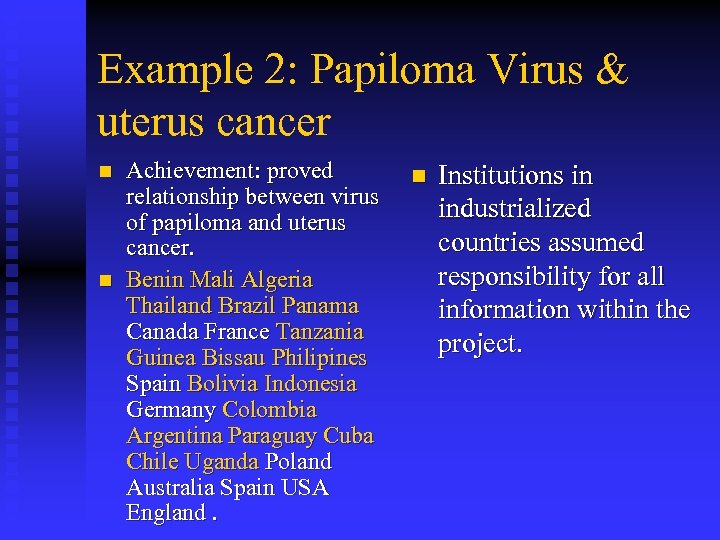

Example 2: Papiloma Virus & uterus cancer n n Achievement: proved relationship between virus of papiloma and uterus cancer. Benin Mali Algeria Thailand Brazil Panama Canada France Tanzania Guinea Bissau Philipines Spain Bolivia Indonesia Germany Colombia Argentina Paraguay Cuba Chile Uganda Poland Australia Spain USA England. n Institutions in industrialized countries assumed responsibility for all information within the project.

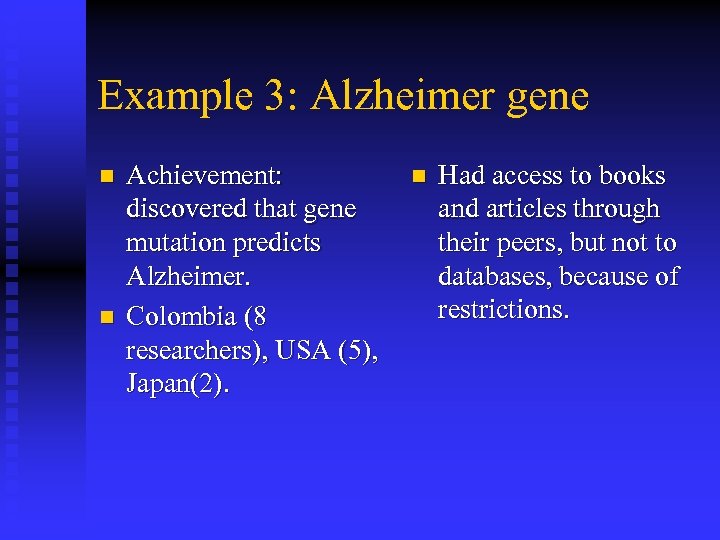

Example 3: Alzheimer gene n n Achievement: discovered that gene mutation predicts Alzheimer. Colombia (8 researchers), USA (5), Japan(2). n Had access to books and articles through their peers, but not to databases, because of restrictions.

Networking, cooperation and the value of information 1 (important, because access to info is critical for participation) n potential of questioning n “Putting information into theory and paradigms from the hands of a more the vantage point of more diverse population of diverse experimentation researchers” (David and environments. Foray 1995) n “Research about research”: n cooperation in research some projects demand large processes where partial number of cases and results “add-up” towards a diversity of environments for common scientific goal. meta-analysis. Despite controversy, evidence-based n wider set of peers capable medicine (Oxman et al. of reviewing publications 1993) is one example. or validating experiments in diverse environments.

Networking, cooperation and the value of information 2 n Sharing funding and execution of big-science projects, especially when these projects need locations in different geographical scenarios: u global warming, u Antarctica, u particle capturing at equatorial latitude. - - - Adressing a wider range of problems, not among priorities of developed countries. Malaria illustrates that priorities of larger scientific communities (and expenditures of financing agencies) may be skewed against the solution of problems of tropical countries. This bias may be offset by financial and scientific efforts from developing countries.

Two sides of the economic analysis of a regulation of intellectual property: n The Size of Overall Benefits n The Distribution of Benefits We will compare intellectual property (monopoly for the commercial exploitation) with public domain institutions to regulate exchange of information useful in research.

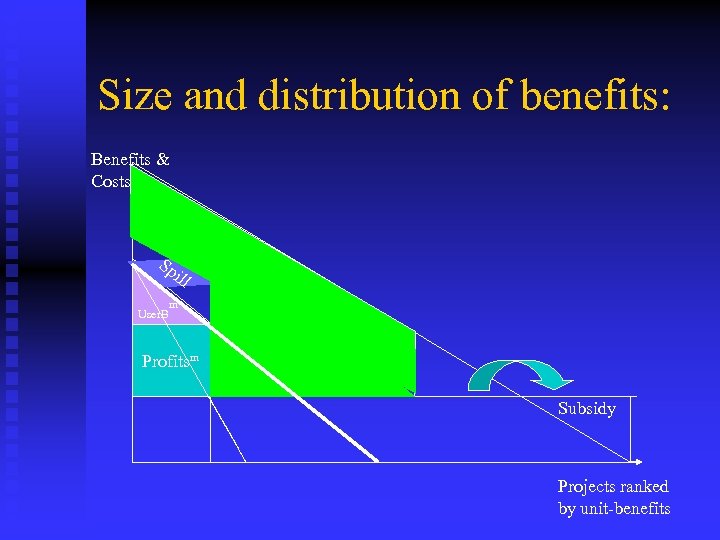

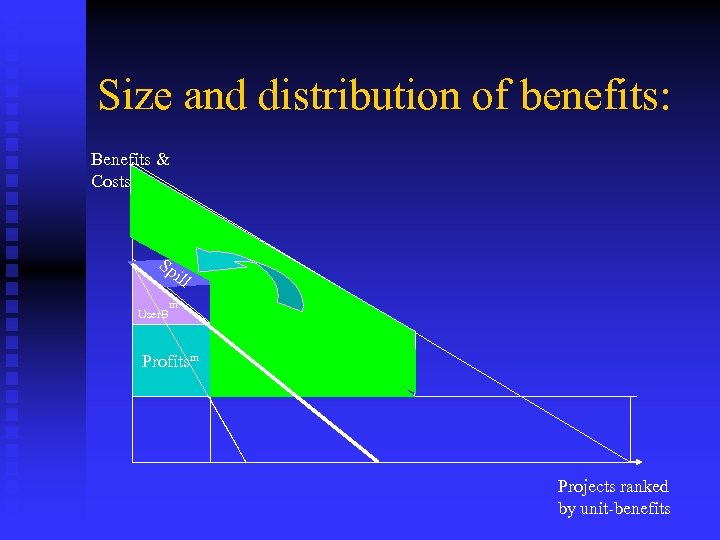

Size and distribution of benefits: Benefits & Costs Sp il l User. B m Profitsm Subsidy Projects ranked by unit-benefits

Under Public Domain: n n n Public financing of production of information is necessary (Governments, donations or community resources). When social benefits are considerably larger than private benefits, public domain is worthwhile (characteristic of information goods). Under a regime of public domain, users of information take all the benefits. Under IPR, benefits are shared between producer and user of information.

Besides, there are transaction costs: n n n Under monopoly (IPR), the social costs of running a protection system (justice). Under public domain, the costs of giving incentives to producers of that information. Other benefits of public domain: u u u As research is risky, if scientists have to pay for the information, they are prone not to buy it. Valuing information and deciding whether to buy it or not is difficult, because he does not know its true value. This reduces research below the social optimum. Under public domain, there is no economic risk for the scientist associated with the access to information. When social benefits are larger than private benefits, the signals emitted by the price system are not reliable.

An extreme case of the public domain: “cheap-talk” n n n In the analyses of Silicon Valley, it was observed that companies encouraged their employees to share secrets with competition. Even in industry, opening access to databases is common practice: u Celera/Berkeley Drosophila Genome Project (“used to validate gene sequencing methods” – Maurer 2002). u “Ensembl” database. u Merck’s strategy against “short-snippet” patenting of human genetic code by too many small firms. Made public database u Sometimes, firms publish in journals. (Coffman et al. ). In all these cases, beyond a social value of the public domain, a private value to the producer of databases is detected. (The owner of the information can appropriate the benefits from the access of others to this information).

Institutional analysis n n n Often, the economic optimum is not attainable, and participants do not have incentives to cooperate in sharing the information, though social benefits of cooperation are large. (Many examples have been given in this workshop). Perhaps there is a cultural element, but institutional and incentive reasons ought to be addressed. In most cases, there are no individual incentives for sharing data (e. g. , absence of data journals).

Institutional obstacles for sharing data n n n Two reward systems coexist side-by-side (Dasgupta, David): u the reward system of science, where the rule of priority is central. u The market system, where profit is the reward. The neighborhood of the market (the potential for commercializing knowledge) is in part responsible for mistrust in scientific exchange. This neighborhood is increasingly closer. International exchanges of information are particularly prone to the failure to create “scientific commons”. No enforcement authority for the international exchange of information exists in general. As a consequence:

Data-release strategies in science n n The suspicion that agreements will not be honoured is harmful. When the “science commons” fail, because of a lack of incentives, scientists develop strategies for the partial disclosure of data. u u u n n n Strategies to “dosify” or “sequence” the disclosure of information are used. Planned obsolescence of data is practised. Conditioned and limited use of information. Scientists producing information become eager to learn about these strategies. Social benefits of the creation of knowledge decrease. Developing countries are particularly affected.

Size and distribution of benefits: Benefits & Costs Sp il l User. B m Profitsm Projects ranked by unit-benefits

International agreements n n Biodiversity is an area where all these problems show. Some countries are net providers of biodiversity information, others are net users. Two ways around: u Information-exchange negotiations across different areas. u Collaboration projects. The commercial value of one country’s biodiversity depends on the bio-diversity agreements of its neighbours. As a consequence of these “science-commons failures”, very few biodiversity or ethnic knowledge agreeements have become operative.

Conclusion Not all failures to exchange information can be blamed on the “culture of scientists”. n These are by enlarge originated in: u Formal and informal scientific institutions. u The close neighborhood of the market. u The lack of incentives to share or publish data. n

37245cedd6f871efe37b023c4db64779.ppt