10 Hormone Replacement Therapy and BC.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 71

BELARUS – MINSK BELARUSIAN STATE MEDICAL UNIVERSITY Dr. Isaac Roisman M. D. , Dip. Surg. , M. Surg. , D. Sc. Dr. Akram Hasson Ph. D. Carmel College, Haifa, Israel

Dr. Akram Hasson Ph. D. Parliament Member – Knesset Member President of Carmel College Former Mayor of Carmel City

Hormone Replacement Therapy (HRT) and Breast Cancer Lecturers: Dr. Isaac Roisman M. D. , Dip. Surg. , M. Surg. , D. Sc. Dr. Akram Hasson Ph. D. Carmel College, Haifa, Israel

Hormone Replacement Therapy (HRT) and Breast Cancer • Hormone Replacement Therapy (HRT) is the term used for the administration of estrogen, or estrogen plus progestin, to women who have reached menopause. Estrogen is most commonly given with progestin to women who still have a uterus, because as early as 1975 investigators had found that estrogen, taken alone, increased the incidence of uterine cancer. This increased risk is eliminated when progestin is added. (2 b) Estrogen replacement therapy (ERT) alone is thus generally given only to women who have had hysterectomies.

• The majority of American women do not take any form of HRT during or after menopause; of those who do, most take it for fewer than 5 years. Minorities of women – percentages vary across community studies; take HRT for the rest of their lives. HRT is highly effective in alleviating the most common menopausal symptoms, including hot flashes, night sweats, emotional liability, palpitations, insomnia, uncomfortable and frequent urination, and painful sexual intercourse. • For over 70 years, women have used oestrogen based hormone replacement therapy (HRT) to relieve distressing symptoms associated with menopause. [1, 2] • Doubt over the long-term safety of HRT led to Women's Health Institute (WHI) a large perspective double blind placebo control trial that was used enquire oestrogen (Premerin, Wyeth) and progesterone acetate. (Provera, Pfizer) [3]

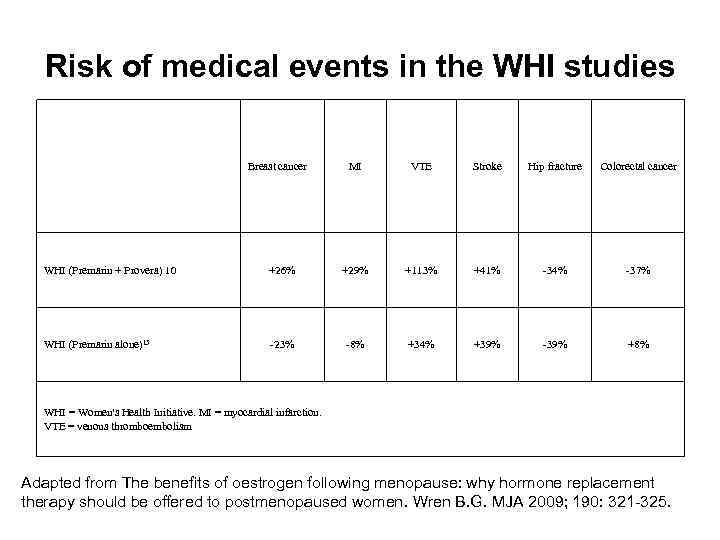

• In the United Kingdom, a large cohort study, the Million Women Study (MWS) was published in 2003. It also received wide media exposure because it found that HRT increased the risk of breast cancer in trial participants. • The initial WHI study and the MWS found that oestrogen-based HRT increased women's risk of breast cancer; the WHI study also reported that HRT increased the risk of myocardial infarction, stroke and dementia. [4, 5]

Risk of medical events in the WHI studies Breast cancer MI VTE Stroke Hip fracture Colorectal cancer WHI (Premarin + Provera) 10 +26% +29% +113% +41% -34% -37% WHI (Premarin alone)15 -23% -8% +34% +39% -39% +8% WHI = Women's Health Initiative. MI = myocardial infarction. VTE = venous thromboembolism Adapted from The benefits of oestrogen following menopause: why hormone replacement therapy should be offered to postmenopaused women. Wren B. G. MJA 2009; 190: 321 -325.

The Million Women Study • From 1996 to 2001, all women due to have a routine mammogram in the UK were invited to enter a study to determine factors that may increase the risk of breast cancer. The results suggested that women who were taking some form of hormone therapy has an increased risk of breast cancer, whereas women who has ceased HRT 12 or more months previously had no increased risk. • Major criticisms were: just over 50% of invited women eventually had a mammogram, suggesting there could have been self selection bias in the study population; the number of women in the UK using HRT were overrepresented in the study (32% v 19%); the average time from beginning therapy to diagnosis of cancer was brief (1. 2 years), suggesting to clinicians that, in many cases, cancer had been present before initiating treatment and that hormones had accelerated its growth, rather than causing it. [7]

Reduction in breast cancer • The number of women diagnosed with breast cancer in the US fell by between 6% and 8% from 2000 to 2004. [8, 9] It has been suggested that the fall was due to a 40% reduction in the use of HRT following publication of the WHI studies and the MWS, and it was claimed that this was further proof that hormones increased the risk of breast cancer. • Clinical experience, [10] however, suggests that the mutations that result in breast cancer begin to accumulate during the premenopausal years and having developed in a cell, persist in that cell until mutations in immunoglobulin's, and other adhesion proteins allow invasive cancer to occur, sometimes many years later. Hormones promote rapid growth of a pre-existing breast disease. If hormones were responsible for promoting breast cancer, the first evidence of a reduction in breast cancer incidence would not be detected for at list 1 -2 years after women had ceased hormone therapy.

According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), breast cancer accounted for 4% of female deaths in Australia in 2006, [11] and clinical reports from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare confirm that almost 25% of breast cancers occur in women under the age of 54 years. Evidence that the changes resulting in breast cancer begin in young women has been confirmed by reports from a number of post-mortem studies on women who have died from non-malignant causes.

![At least 90 aberrant genetic mutations are implicated in breast cancer. [12, 13] It At least 90 aberrant genetic mutations are implicated in breast cancer. [12, 13] It](https://present5.com/presentation/11382396_344121787/image-13.jpg)

At least 90 aberrant genetic mutations are implicated in breast cancer. [12, 13] It is now accepted that most mutation are either inherited of occur spontaneously during mitosis. Based on epidemiological studies, there are claims that HRT is a mutagen that leads to breast cancer. A complex hypothesis has been proposed, which stated that oestradiol is converted by specific enzymes into catechol oestradiol, which, through futher bio chemical metabolism to quinone intermediates, is asserted to be a weak mutagen. Synthetic progestogens have also been blamed, based on epidemiological evidence reporting an increased incidence of detected invasive breast cancers when combined oestrogenand progestogens have been used, but there is no biological evidence to support either oestradiol or progestogens as a mutagen that leads to breast cancer.

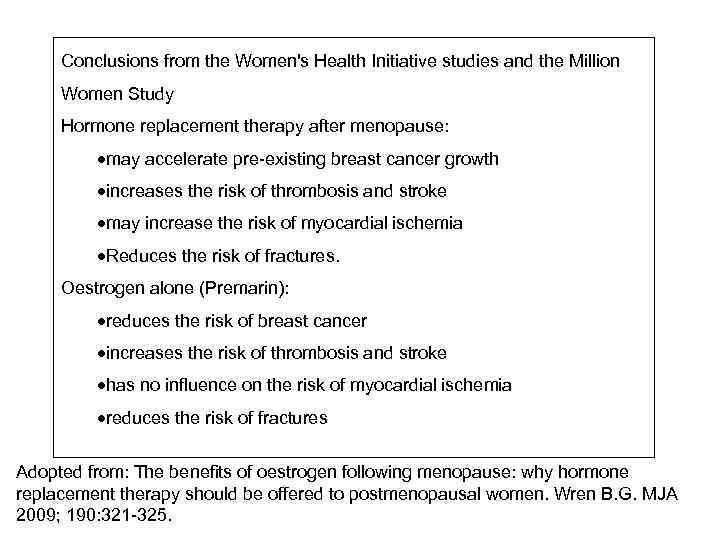

Conclusions from the Women's Health Initiative studies and the Million Women Study Hormone replacement therapy after menopause: may accelerate pre-existing breast cancer growth increases the risk of thrombosis and stroke may increase the risk of myocardial ischemia Reduces the risk of fractures. Oestrogen alone (Premarin): reduces the risk of breast cancer increases the risk of thrombosis and stroke has no influence on the risk of myocardial ischemia reduces the risk of fractures Adopted from: The benefits of oestrogen following menopause: why hormone replacement therapy should be offered to postmenopausal women. Wren B. G. MJA 2009; 190: 321 -325.

An earlier prospective, randomized, double-blind study had found no increased risk of breast cancer in women on HRT. Even after 22 years, but this small study never made headlines. The WHI research has cost nearly a billion dollars; the investigators consist of eminent physicians, statisticians, and epidemiologists across the country and the findings have been published in medicine's most prestigious journals. Accordingly, the WHI's findings received, and continue to receive, worldwide attention. It is no wonder that its claims of the dangers of HRT caused the prescription rate for HRT to fall by some 50%.

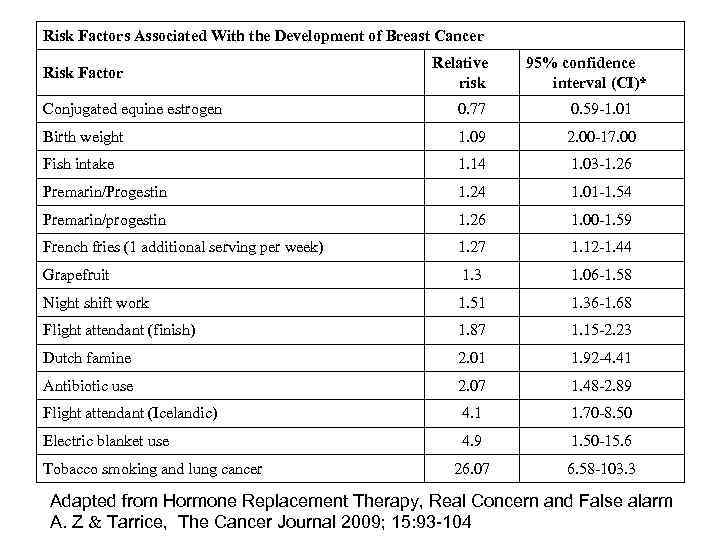

Risk Factors Associated With the Development of Breast Cancer Risk Factor Relative risk 95% confidence interval (CI)* Conjugated equine estrogen 0. 77 0. 59 -1. 01 Birth weight 1. 09 2. 00 -17. 00 Fish intake 1. 14 1. 03 -1. 26 Premarin/Progestin 1. 24 1. 01 -1. 54 Premarin/progestin 1. 26 1. 00 -1. 59 French fries (1 additional serving per week) 1. 27 1. 12 -1. 44 Grapefruit 1. 3 1. 06 -1. 58 Night shift work 1. 51 1. 36 -1. 68 Flight attendant (finish) 1. 87 1. 15 -2. 23 Dutch famine 2. 01 1. 92 -4. 41 Antibiotic use 2. 07 1. 48 -2. 89 Flight attendant (Icelandic) 4. 1 1. 70 -8. 50 Electric blanket use 4. 9 1. 50 -15. 6 26. 07 6. 58 -103. 3 Tobacco smoking and lung cancer Adapted from Hormone Replacement Therapy, Real Concern and False alarm A. Z Tarrice, The Cancer Journal 2009; 15: 93 -104

Cuzick J. demonstrated that Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) has had a chequered history ever since it's initial use to manage menopausal symptoms. It is clear that it has many other effects and here we review its impact on the risk of breast cancer. A clear risk is seen for current uses of combined oestrogen/progestagen pills, but this returns to normal shortly after treatment cessation. The role of oestrogen only replacement therapy is less clear, but most studies find a weaker, but still positive, association in current users. Recent sharp reductions in HRT use have been correlated with declines in breast cancer incidence in the USA, but not so clearly elsewhere.

• Cuzick SS. Haglong KW, Kaye JA et al demonstrated the relation of various estrogen-containing hormone therapies to the risk of breast cancer, emphasizing the use of the combination of estrogen and testosterone. [15] • The results identify 4, 515 cases and 18, 058 matched controls. The OR for users of estrogen alone compared with the nonusers was 0. 96 (95% confidence interval (CI) 0. 88 -1. 06; 667 cases and 2, 900 controls); for users of conjugated estrogen plus progestin, it was 1. 44 (95% CI 1. 31 -1. 58; 712 cases and 2, 087 controls); and for users of esterified estrogen with methyltestosterone and esterified estrogen with methyltestosterone plus progestin, the Ors were 1. 08 (95% CI 0. 86 -1. 36; 98 cases and 380 controls) and 1. 69 (95% CI 1. 03 -2. 79; 22 cases and 55 controls), respectively. There was an increased risk among conjugated estrogen plus progestin users of 48 months or more (OR 3. 10, 95% CI 2. 38 -4. 04; 111 cases and 149 controls).

They concluded that there is no materially increased risk of breast cancer in users of estrogen alone or esterified estrogen with methyltestosterone compared with nonusers. There is an increased risk among those using conjugated estrogen plus progestin. In particular, the risk of breast cancer in women who used conjugated estrogen plus progestin for 4 or more years is approximately three times higher than in women who are not exposed to hormone therapy, so that the background incidence rate for women aged 50 to 64 years, which is around 3 per 1, 000, would be increased to approximately 9 per 1, 000 in women aged 50 to 64 years who have taken conjugated estrogen plus progestin for 48 months or more.

![• Lyytinen et al [16] estimated the risk for breast cancer in Finnish • Lyytinen et al [16] estimated the risk for breast cancer in Finnish](https://present5.com/presentation/11382396_344121787/image-21.jpg)

• Lyytinen et al [16] estimated the risk for breast cancer in Finnish women using postmenopausal estradiol (E 2) - progestogen therapy. • The methods: All Finnish women over 50 years using E 2 -progestogen therapy for at least 6 months in 1994 -2005 (N=221, 551) were identified from the national medical reimbursement register and followed up for breast cancer incidence (n=6, 211 cases) through the Finnish Cancer Registry to the end of 2005. The risk for breast cancer in E 2 -progestogen therapy users was compared with that in the general population.

The results: The standardized incidence ratio for all types of breast cancer was not elevated within the first 3 years of use, but it rose to 1. 31 (95% confidence interval 1. 20 -1. 42) for the use from 3 -5 years and to 2. 07 (1. 842. 30) with 10 or more years of use. Exposure to sequential progestogen for 5 years or more was accompanied with a lower risk elevation (1. 78, 1. 641. 90) than exposure to continuous use (2. 44, 2. 17 -2. 72). Oral and transdermal use of E 2 -progestogen therapy was associated with comparable risk elevations for breast cancer. The use of norethisterone acetate was accompanied with a higher risk after 5 years of use (2. 03, 1. 882. 18) than that of medroxyprogesterone acetate (1. 64, 1. 49 -1. 79).

• They concluded that the use of E 2 -progestogen therapy is associated with an increased risk for breast cancer after 3 years of use. The risk is lower for sequential than for continuous use, but comparable for oral and transdermal use. The risk elevation may not be uniform for all progestogens. • Chlelowskie et al [17] reported the release of the 2002 report of the Women's Health Initiative (WHI) trial of estrogen plus progestin, the use of menopausal hormone therapy in the United States decreased substantially. Subsequently, the incidence of breast cancer also dropped, suggesting a cause-and-effect relation between hormone treatment and breast cancer. However, the cause of this decrease remains controversial.

Methods: they analyzed the results of the WHI randomized clinical trial in which one study group received 0. 625 mg of conjugated equine estrogens plus 2. 5 mg of medroxyprogesterone acetate daily and another group received placebo and examined temporal trends in breast cancer diagnosis in the WHI observational study cohort. Risk factors for breast cancer, frequency of mammography, and time specific incidence of breast cancer were assessed in relation to combined hormone use. They concluded that the increased risk of breast cancer associated with the use of estrogen plus progestin declined markedly soon after discontinuation of combined hormone therapy and was unrelated to changes in frequency of mammography.

![• Brinton et al [18] showed that results from the Women's Health Initiative • Brinton et al [18] showed that results from the Women's Health Initiative](https://present5.com/presentation/11382396_344121787/image-26.jpg)

• Brinton et al [18] showed that results from the Women's Health Initiative trial raise new questions regarding the effects of estrogen therapy (ET) and estrogen plus progestin therapy (EPT) on breast cancer risk. • They analyzed data from 126, 638 females, ages 50 to 71 years at baseline, who completed two questionnaires (1995 -1996 and 1996 -1997) as part of the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Cohort Study and in whom 3, 657 incident breast cancers were identified through June 30, 2002. Hormone associated relative risks (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) of breast cancer were estimated via multivariable regression models.

And the results: Among thin women (body mass index < 25 kg/mw), ET use was associated with a significant 60%excess risk after 10 year of use. EPT was associated with a significantly increased risk among women with intact uteri, with the highest risk among current, long-term (> or = 10 years) users (RR, 2. 44; 95% CI, 2. 13 -2. 79). These risks were slightly higher when progestins were prescribed continuously than sequentially (< 15 days/mo; respective RRs of 2. 76 versus 2. 01). EPT associations were strongest in thin women, but elevated risks persisted among heavy women. EPT use was strongly related to estrogen receptor (ER) – positive tumors, requiring consideration of this variable when assessing relationships according to other clinical features. For instance, ER-ductal tumors were unaffected by EPT use, but all histologic subgroups of ER+ tumors were increased, especially low-grade and mixed ductal-lobular tumors.

• They concluded that both ET and EPT were associated with breast cancer risks with the magnitude of increase varying according to body mass and clinical characteristics of the tumors. • Hulka et al [19] said that North America and Northern Europe, breast cancer incidence rates begin increasing in the early reproductive years and continue climbing into the late seventies, whereas rates plateau after menopause in Japan and less developed countries. Female gender, age and country of birth are the strongest determinates of disease risk. Family history and mutations in the BRCA 1 and BRCA 2 genes are important correlates of lifetime risk. Genetic polymorphism associated with estrogen synthesis and metabolisms are currently under study. In postmenopausal women, increased breast density on mammograms increases risk. Current use of oral contraceptives and prolonged, current or recent use of hormone replacement therapy moderately increase risk.

The incidence and mortality rated from breast cancer vary greatly around the world, exhibiting at least a 10 -fold variation (10 -110 new cases per 100, 000 women per year). In general the rates are highest in the developed countries of North America and Northern Europe and lowest in less developed countries of the Far East, Africa and South America. Japan is an exception, being a highly developed country with low breast cancer rates. However, rates have been rising in Japan over the last few decades, although this is not reflected in older women who have experienced lower breast cancer rates throughout their life times.

The United Stated experienced a marked increase in breast cancer incidence during the 1980 s with a small decline during the 1990 s to about 110 per 100, 000 women annually. Since 1989, there has been a decline in mortality rates averaging 1. 8% per year. The increased incidence rates of the 1980 s are attributed to the introduction and widespread acceptance of screening mammography. The initial effect of a screening program is an increase in the number of cases detected. After the pool of prevalent cases has been detected and treated, the incidence rate should decline, since only newly arising cases are available for mammographic detection. The decline in breast cancer mortality has been attributed to both the earlier stage at diagnosis associated with screening and the use of adjuvant therapies. For the USA, 175, 000 new cases of invasive breast cancer and 43, 300 deaths are predicted for 1999 [19].

Endogenous estrogens • Although there are many hormonally relevant factors, only two appear in the relative risk category 2. 1 -4. 0. Bilateral oophorectomy has a significant impact on breast cancer risk. The earlier in life that the ovaries are removed, the greater the risk reduction. This was one of the first observations suggesting a hormonal role in breast cancer etiology. • Bone density is the other factor in this risk category. In postmenopausal women, those with a high bone density are also at the highest risk of breast cancer. Since estrogens of either exogenous or endogenous origin are known to help retain bone mass, the inference is made that bone density and breast cancer risk are correlated as a function of the amount of estrogen available to the target tissues.

• Other well-established breast cancer risk factors are associated with endogenous female hormones, but the magnitude of the relative risk estimates is in the 1. 1 -2. 0 range. A younger age at menarche and older age at menopause suggest that the risk of breast cancer is directly related to the length of exposure time to cycling ovarian hormones. A younger age at menopause is protective regardless of whether the menopause was natural or surgical. • Pregnancy is generally thought to reduce the risk of breast cancer in subsequent years. The younger a woman is at her first full-term pregnancy, the lower her risk of breast cancer, and additional pregnancies further reduce her risk.

Exogenous estrogens The relationship of exogenous hormones, primarily hormonal contraceptives and hormone replacement therapy, to breast cancer has been researched extensively. The lack of total consistency among studies may be attributed in part to the fact that these exposures are not static. Changes in patterns of use, reduction in hormone dose, and temporal considerations all contribute to the difficulty in comparing the many studies.

Menopausal hormone therapy has not remained the same over the years. Unopposed estrogen therapy was commonly used until the mid-to late 1970 s, when its association with endometrial cancer was discovered. Use of menopausal estrogens in the United States declined at that point. Since the 1980 s, there has been resurgence in use due to the recognition of the benefits in preventing osteoporosis and heart disease in addition to the long -recognized benefits in relieving hot flushes and other symptoms of menopause. However, current recommendations are for women with an intact uterus to take a progestin along with estrogen to protect the endometrium. Conjugated equine estrogen (Premarin ) has been the most commonly prescribed estrogen in the United States for decades, but the average estrogen dose has been reduced from 1. 25 mg to 0. 625 mg for most women. Outside of the United States, other types of estrogens (e. g estradiol, estriol) have been used more commonly.

The evidence suggests that menopausal estrogens are associated with a modest increase in breast cancer risk. Long-term use (5 years or more) among current or recent users appears to be associated with a 30 -50% increase in breast cancer risk. Reports from both the Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer and the US Nurses Health Study support these risk estimates. Among current users in the Nurses Health Study, older women (aged 60 -64) who had used estrogens for at least 5 had double the risk of women who reported no hormone use. Both study groups found a higher proportion of localized disease among hormone users that among non-users. Other reports have suggested that the risk from exogenous hormones may be somewhat higher in certain subgroups such as women with a family history of breast cancer.

• HRT is mainly indicated to alleviate climacteric symptoms as well as to strengthen bone. Previous epidemiological findings on HRT and the risk of EOC are contradictory. In a few studies HRT appeared to reduce the risk of EOC, whereas other studies demonstrated no associations, or moderately increased risks of EOC among HTR users. In several studies where a positive association between HRT ever-use and EOC risk was seen, no clear trends with duration appeared. However, other studies indicated elevated EOC risks after longer duration of HRT use, and excess risk that declined after discontinuation of use [20]. • In a recent well conducted cohort study of 44, 241 US women, a RR for ovarian cancer of 1. 6 (95% CI 1. 2 -2. 0) was reported among ever-users compared with never users of estrogen replacement therapy (ERT), and the largest risk was seen among those who had used ERT for 20 years or more (RR 3. 2; 95% CI 1. 7 -5. 7).

● One of the studies evaluated the risk of EOC in relation to sequential or continuous progestin regimens in HRT. This study demonstrated an increased risk of EOC among ever-users compared with never-users of HRT containing estrogens opposed by sequential progestins (OR 1. 53; 95% CI 1. 15 -2. 05), and the highest risks were observed among those who had used this type of HRT in excess of 10 years. Ever-use of estrogens continuously combined with progetins was unrelated to EOC risk (OR 1. 02; 95% CI 0. 73 -1. 43). In the Women's Health Initiative (WHI) study, the hazard ratio for the increased risk of ovarian cancer was 1. 58 (95% CI 0. 74 -3. 24) in women who were randomly assigned to either a fixed combination of 0. 625 mg conjugated estrogen plus 2. 5 mg medroxyprogesterone acetate or the placebo [21]. The risk estimate was based upon 32 incident ovarian cancers (20 in the treatment group and 12 in the placebo group) that occurred during a mean follow-up of 5. 6 years.

Although statistically not significant, the WHI authors suggested that the risk of ovarian cancer is increased among users of this type of HRT regimen. In a population based study in Washington State, 812 women with ovarian cancer and 1313 controls were interviewed about the use of HRT and other characteristics. The risk of EOC was increased among current or recent (within the last three years) users of unopposed estrogen for five or more years (OR 1. 6, 95% CI 1. 1 -2. 5 and OR 1. 8, 95% CI 0. 8 -3. 7, respectively). However no increase in risk was noted among women who used combined estrogen and progestins therapy regardless of duration (OR 1. 1, 95% CI 0. 8 -1. 5).

Some studies suggest that the effect of ERT on EOC risk is modified by hysterectomy, with an excess risk of EOC among ERT users present only among women with an intact uterus but not in hysterectomized women [22]. However, the US cohort data reported an elevated risk of EOC among both hysterectomized and nonhysterectomyzed subjects. The responsiveness to HRT may differ depending on the histological type of EOC, serous being the most common, followed by mucinous and then endometroid and clear cell. Elevated risks of the less common endometrioid EOC, in particular have been reported by most but not all studies examining this association. Some but not other indicated an elevated risk of serous EOC among ERT users, while most previous research indicates that HRT is unrelated to the risk of mucinous EOC, although positive associations have been observed.

In one of these studies, based on a cohort of more that 200, 000 postmenopausal women, an RR of 2. 20 (95% CI 1. 53 -3. 17) for fatal EOC appeared among those who had used ERT longer than 10 years compared with nonusers. However, it has also been reported that HRT is not related to the risk of recurrent EOC. Only a handful of studies have reported no association between the use of HRT and the risk of BOT.

The potential carcinogenic effect of HRT compounds could be explained by retrograde bleeding through the Fallopian tubes. This suggestions supported by the absence of an elevated risk of EOC among hysterectomized women using ERT [23]. An additional, perhaps more likely, mechanism to explain an increased risk of EOC among HRT users includes a direct hormonal action on steroid receptors [24]. Estrogen is a well-known endometrial lining carcinogen. Although the explanation for the increased risk with HRT/ERT is not clear, this should nevertheless be considered as part of the overall discussion of risk and benefits of treatment.

Established risk factors for breast cancer include low parity, late age at first pregnancy, obesity and high alcohol consumption. The mechanisms by which such risk factors relate to breast cancer are unclear at present, although may involve alteration in exposure to estrogen. In postmenopausal women, production of estrogens occurs primarily via the aromatization of androgens in the periphery in contrast to the predominantly ovarian production seen in premenopausal women. Increased levels of estrogens have been associated with an increased risk of developing breast cancer in postmenopausal women. Indeed, a large proportion of breast cancers in postmenopausal women express estrogen receptors and are stimulated by estrogens to proliferate. Consequently, estrogen deprivation has proven to be effective in the treatment of breast cancer. [25]

The incidence of breast cancer (ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) and invasive breast cancer) has risen substantially over the past 20 years, in parallel with increasing use of screening mammography. While DCIS overdiagnosis is well accepted as a consequence of mammography screening, overdiagnosis of invasive breast cancer is more controversial and more counterintuitive. However, it is plausible that overdiagnosis of invasive breast cancer could occur through extension of the "length time" effect of screening which is the tendency of screening to detect less aggressive or even inconsequential cancers while more active cancers occur as interval cases. Overdiagnosis is important because it results in overtreatment, including surgery, radiotherapy and endocrine therapy of women who would not be diagnosed or treated for breast cancer without screening. In addition, it has psycho-social consequences including anxiety, depression, labeling and impacts on insurance status [26].

The levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (IUS) was launched in Austria over a decade ago, and has since become the most widespread form of long acting contraception. The levonorgestrel-releasing IUS is currently approved for contraception, the treatment of hypermenorrhoea, and endometrial protection during oestrogen replacement therapy. In addition, the levonorgestrel-releasing IUS can improve outcomes in the treatment of pain related to endometriosis and adenomyosis of the uterus.

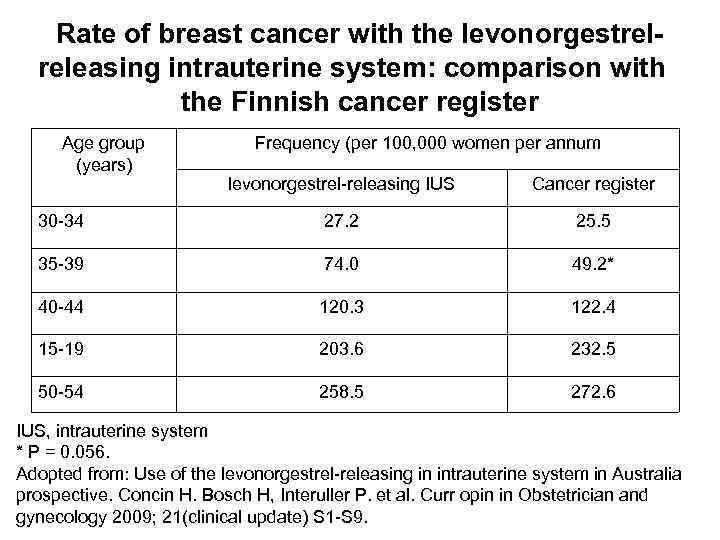

The proportion of women over the age of 40 years desiring long-acting contraception is on the increase, whereas the risk of developing breast cancer increases with age from 40 years. To assess whether the use of the levonorgestrel-releasing IUS affects the incidence of breast cancer, an extensive survey was conducted in Finland involving 17, 360 women regularly using the levonorgestrel-releasing IUS for contraception (average at insertion 35. 4 years). When stratified by age, point estimates of breast cancer incidence were lower among levonorgestrel-releasing IUS users compared with the overall Finnish female population in three age groups (40 -44 years, 45 -49 years and 50 -54 years). Conversely, in two age groups breast cancer incidence was nominally higher in levonorgestrelreleasing IUS users than the average population (30 -34 years and 35 -39 years).

Rate of breast cancer with the levonorgestrelreleasing intrauterine system: comparison with the Finnish cancer register Age group (years) Frequency (per 100, 000 women per annum levonorgestrel-releasing IUS Cancer register 30 -34 27. 2 25. 5 35 -39 74. 0 49. 2* 40 -44 120. 3 122. 4 15 -19 203. 6 232. 5 50 -54 258. 5 272. 6 IUS, intrauterine system * P = 0. 056. Adopted from: Use of the levonorgestrel-releasing in intrauterine system in Australia prospective. Concin H. Bosch H, Interuller P. et al. Curr opin in Obstetrician and gynecology 2009; 21(clinical update) S 1 -S 9.

On the basis of the 95% confidence intervals, the authors found no evidence of any differences in breast cancer incidence between levonorgestrel-releasing IUS users and the overall Finnish female population in any age groups. The authors thus concluded that the data did not support a causal relationship between use of the levonorgestrel-releasing IUS and breast cancer. More recent date from a large, community-based, case-control study in Germany and Finland, involving women with breast cancer bearing levonorgestrelreleasing or copper IUD, support this view [27].

Very few data are available on the use of the levonorgestrel-releasing IUS after diagnosis with breast cancer. One study conducted in women with a history of invasive breast cancer compared breast cancer recurrence in a group of patients who had used the levonorgestrel-releasing IUS during a subsequent disease-free period (n=86) with recurrence among controls (n=120) matched for age at diagnosis, tumor stage, tumor grade and treatment modalities. Two subgroups of levonorgestrel-releasing IUS users were identified: patients who had been using the levonorgestrel-releasing IUS before the diagnosis of cancer and who did not have their levonorgestrel-releasing IUS removed after diagnosis (subgroup A); and patients who started using the levonorgestrel-releasing IUS subsequent to diagnosis, following completion of breast cancer treatment of while using adjuvant antihormonal therapy (subgroup B).

The authors found no evidence of a higher risk of recurrence in the overall population of levonorgestrel-releasing IUS users compared with matched controls (adjusted hazard ration 1. 86; not statistically significant). When survival curves for recurrence were analyzed in the two subgroups of levonorgestrel-releasing IUS users, patients in subgroup B had a survival curve similar to matched controls, whereas patients in subgroup A had a higher risk of recurrence compared with controls (P= 0. 048). Patients in subgroup A also demonstrated higher nodal involvement at initial diagnosis compared with subgroup B (47. 3% versus 29. 3%), whereas all cases of recurrence were associated with distal metastasis. In contrast, 70% of recurrences in subgroup B were local and susceptible to treatment. The authors concluded that patients who developed breast cancer while using the levonorgestrel-releasing IUS had less favorable disease characteristics and hypothesized that tumors exposed to levonorgestrel during development are more aggressive.

• Evaluation of this study poses problems because of the small number of cases and the lack of information regarding the HER 2/neu status; however, date from cell-line experiments offer support for the authors' hypothesis. Levonorgestrel has been shown to stimulate breast • cancer cell proliferation in vitro. This effect has been linked to activity at the oestrogen receptor as it was not blocked by the progesterone antagonists RU 38486 and Org 31710, but was blocked by the oestrogen antagonists' 4 hydroxytamoxifen and ICI 164. 384. It is worth noting, however, that combined E 2 and levonorgestrel administration was found to inhibit E 2 induced cell growth significantly in those studies.

On the basis of the available evidence, the use of the levonorgestrelreleasing IUS for up to 5 years after a diagnosis of breast cancer is classified as an unacceptable risk according to the WHO (2009). Even in women who are relapse-free 5 years after diagnosis, the WHO considers the possible risk to outweigh the advantages. Physicians should take into account the WHO recommendation, and the information given in the levonorgestrel-releasing IUS summary of product characteristics, when making therapy decisions for women with a history of breast cancer. Any decision should also be taken in consultation with the patient's oncologist and after a thorough patient briefing [27].

![• Verkooijen HM. et al [28] reported inconsistent findings on a possible association • Verkooijen HM. et al [28] reported inconsistent findings on a possible association](https://present5.com/presentation/11382396_344121787/image-55.jpg)

• Verkooijen HM. et al [28] reported inconsistent findings on a possible association between HRT and breast cancer risk, a report from the Nurses' Health Study was the first large study to find a significantly increased risk of breast cancer both for estrogen-only HRT (RR = 1. 32) and for combined HRT (estrogen plus progestagen) (RR = 1. 41). Subsequently, a comprehensive overview of all the available case-control and cohort data from 51 studies, involving 17, 949 women with breast cancer and 35, 916 controls, showed that the increased risk of breast cancer was confined to current and recent use of HRT. Among these current and recent users, breast cancer risks increased after more that 15 years of use. The excess risk was reduced after cessation of use of HRT and largely disappeared after about 5 years.

The Women's Health Initiative, which was launched in 1991, involved a cohort study and two randomized trials of HRT – one with estrogen alone versus placebo in hysterectomized women, and one with combined (estrogen plus progestagen) HRT versus placebo for women with an intact uterus – and aimed to evaluate the effect of HRT on the risk of coronary heart disease, breast cancer, fractures, stroke, pulmonary embolism, colorectal cancer, endometrial cancer and all cause mortality in women aged 50 -79 years. The combined HRT trial was stopped early, because the overall health effects of HRT became significantly inferior for the treated group.

Overall breast cancer risk was significantly increased in the combined HRT trial (hazard ration (HR) = 1. 24), and this risk was similar across age groups, increased with duration of use and was most apparent in women who had used HRT before entry into the trial [13]. The estrogen-only trial was stopped in 2004, after it showed no net health benefit: estrogen-only HRT increased the risk of stroke and had no beneficial effect on the risk of cardiovascular disease, although it did reduce the risk of hip fractures. Initial results suggested a reduced risk of breast cancer associated with estrogenonly HRT, but after additional control for other factors, in particular time from menopause to first use of postmenopausal hormone therapy, there was little indication of a reduction in breast cancer risk among hysterectomized women who initiated estrogen-only HRT after menopause [28].

• Combined HRT, which can be administered continuously or sequentially, is generally taken orally, but can also be delivered by injection, transdermal patch or implanted preparations [8, 11]. Even though the estimated risk of breast cancer may vary between methods of delivery, all are associated with an increased risk of breast cancer [28]. • In parallel to the rise in HRT use during the 1980 s and 1990 s, the incidence rates of invasive lobular carcinoma increased disproportionately compared with rates of ductal cancer in some populations, particularly in postmenopausal women. This observation generated the hypothesis that HRT use is particularly associated with lobular breast cancer subtypes (pure lobular or ducto-lobular breast cancer). Several studies have now consistently shown that the use of combined HRT is associated with a significant 2 -4 fork increased risk of lobular or ducto-lobular carcinoma. In contrast, the association between combined HRT and ductal carcinoma is less consistent: i. e some studies showed no association, while others showed weak associations.

![Rosenberg L. et al [29] considered that obesity has repeatedly been associated with breast Rosenberg L. et al [29] considered that obesity has repeatedly been associated with breast](https://present5.com/presentation/11382396_344121787/image-60.jpg)

Rosenberg L. et al [29] considered that obesity has repeatedly been associated with breast tumors of larger size, lymph node positivity, and poor prognosis, although some studies have produced contrasting findings. However, many studies lack information on the use of hormone replacement therapy (HRT) and mammography examinations before diagnosis. Use of HRT interacts, or rather competes, with obesity on breast cancer risk among postmenopausal women, probably by sharing hormonal carcinogenic pathways. The HRT effect on risk is most pronounced in lean postmenopausal women, in whom the endogenous production of oestrogen is the lowest. Obese women might benefit more from mammographic screening than normal weight women because of larger breasts, more difficult to palpate, and a lower mammographic breast density, and thereby a higher sensitivity of the mammography.

• Overall, obese compared with normal weight women had an increased risk of breast cancer death (HR 1. 4, 95% CI 1. 1 -1. 9; Table 3). When they stratified by the use of HRT, we found no association between BMI and survival among never HRT users (HR 1. 1, 95% CI 0. 8 -1. 6; Table 3), whereas this association was clearly evident among oestrogen-progestin users when comparing obese with normal weight women (HR 3. 7, 95% CI 1. 9 -7. 2). In these analyses, evidence of heterogeneity was found for use of HRT (P = 0. 0029). On the other hand, the influence of BMI on survival was similar whether diagnosed by mammography screening or nor (P= 0. 98). • Opposite to what said till now, Bleving et al , published in 2009, a time line of relevant events and studies.

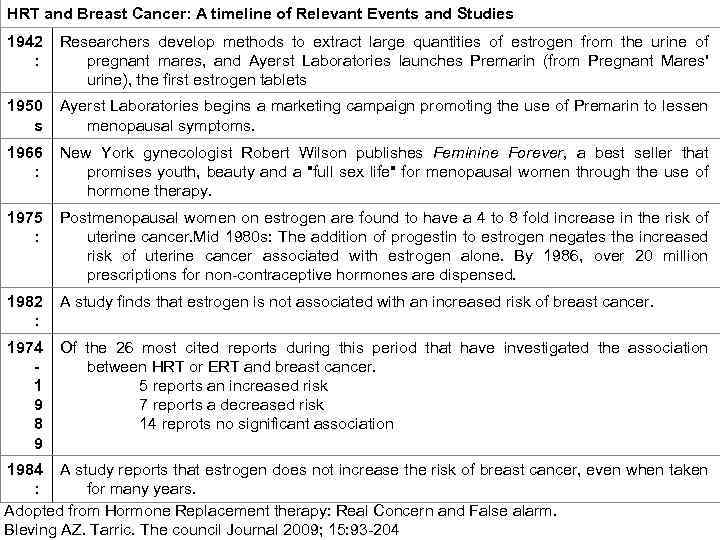

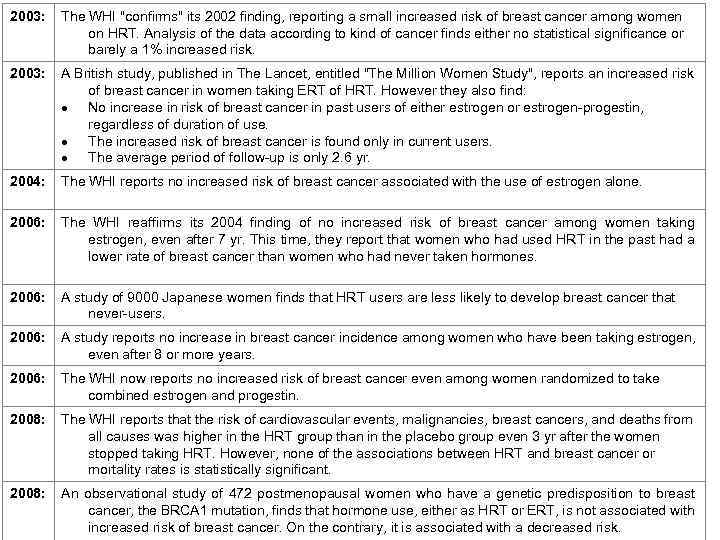

HRT and Breast Cancer: A timeline of Relevant Events and Studies 1942 : Researchers develop methods to extract large quantities of estrogen from the urine of pregnant mares, and Ayerst Laboratories launches Premarin (from Pregnant Mares' urine), the first estrogen tablets 1950 s Ayerst Laboratories begins a marketing campaign promoting the use of Premarin to lessen menopausal symptoms. 1966 : New York gynecologist Robert Wilson publishes Feminine Forever, a best seller that promises youth, beauty and a "full sex life" for menopausal women through the use of hormone therapy. 1975 : Postmenopausal women on estrogen are found to have a 4 to 8 fold increase in the risk of uterine cancer. Mid 1980 s: The addition of progestin to estrogen negates the increased risk of uterine cancer associated with estrogen alone. By 1986, over 20 million prescriptions for non-contraceptive hormones are dispensed. 1982 : A study finds that estrogen is not associated with an increased risk of breast cancer. 1974 1 9 8 9 Of the 26 most cited reports during this period that have investigated the association between HRT or ERT and breast cancer. 5 reports an increased risk 7 reports a decreased risk 14 reprots no significant association 1984 A study reports that estrogen does not increase the risk of breast cancer, even when taken : for many years. Adopted from Hormone Replacement therapy: Real Concern and False alarm. Bleving AZ. Tarric. The council Journal 2009; 15: 93 -204

2003: The WHI "confirms" its 2002 finding, reporting a small increased risk of breast cancer among women on HRT. Analysis of the data according to kind of cancer finds either no statistical significance or barely a 1% increased risk. 2003: A British study, published in The Lancet, entitled "The Million Women Study", reports an increased risk of breast cancer in women taking ERT of HRT. However they also find: No increase in risk of breast cancer in past users of either estrogen or estrogen-progestin, regardless of duration of use. The increased risk of breast cancer is found only in current users. The average period of follow-up is only 2. 6 yr. 2004: The WHI reports no increased risk of breast cancer associated with the use of estrogen alone. 2006: The WHI reaffirms its 2004 finding of no increased risk of breast cancer among women taking estrogen, even after 7 yr. This time, they report that women who had used HRT in the past had a lower rate of breast cancer than women who had never taken hormones. 2006: A study of 9000 Japanese women finds that HRT users are less likely to develop breast cancer that never-users. 2006: A study reports no increase in breast cancer incidence among women who have been taking estrogen, even after 8 or more years. 2006: The WHI now reports no increased risk of breast cancer even among women randomized to take combined estrogen and progestin. 2008: The WHI reports that the risk of cardiovascular events, malignancies, breast cancers, and deaths from all causes was higher in the HRT group than in the placebo group even 3 yr after the women stopped taking HRT. However, none of the associations between HRT and breast cancer or mortality rates is statistically significant. 2008: An observational study of 472 postmenopausal women who have a genetic predisposition to breast cancer, the BRCA 1 mutation, finds that hormone use, either as HRT or ERT, is not associated with increased risk of breast cancer. On the contrary, it is associated with a decreased risk.

Update

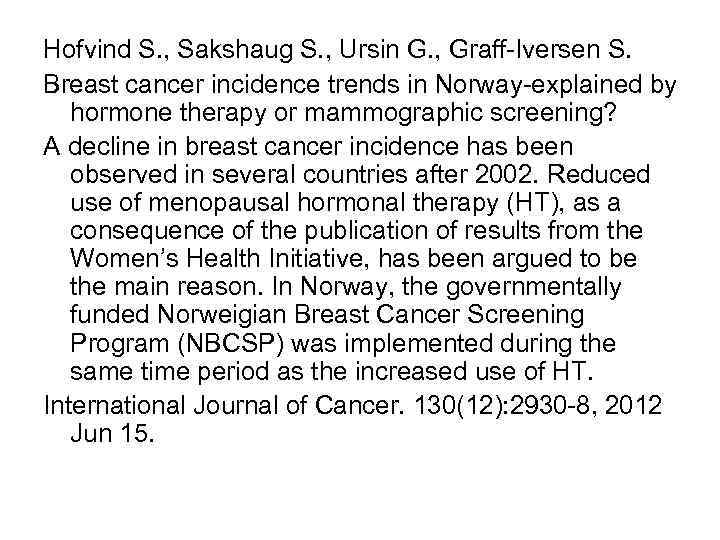

Hofvind S. , Sakshaug S. , Ursin G. , Graff-Iversen S. Breast cancer incidence trends in Norway-explained by hormone therapy or mammographic screening? A decline in breast cancer incidence has been observed in several countries after 2002. Reduced use of menopausal hormonal therapy (HT), as a consequence of the publication of results from the Women’s Health Initiative, has been argued to be the main reason. In Norway, the governmentally funded Norweigian Breast Cancer Screening Program (NBCSP) was implemented during the same time period as the increased use of HT. International Journal of Cancer. 130(12): 2930 -8, 2012 Jun 15.

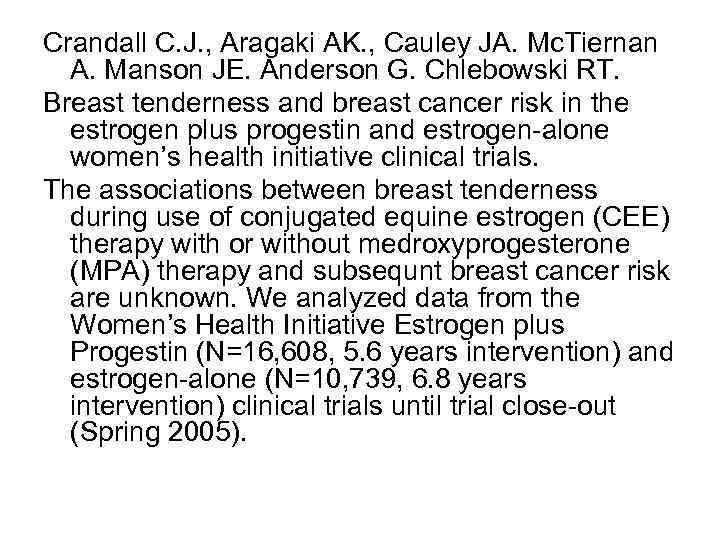

Crandall C. J. , Aragaki AK. , Cauley JA. Mc. Tiernan A. Manson JE. Anderson G. Chlebowski RT. Breast tenderness and breast cancer risk in the estrogen plus progestin and estrogen-alone women’s health initiative clinical trials. The associations between breast tenderness during use of conjugated equine estrogen (CEE) therapy with or without medroxyprogesterone (MPA) therapy and subsequnt breast cancer risk are unknown. We analyzed data from the Women’s Health Initiative Estrogen plus Progestin (N=16, 608, 5. 6 years intervention) and estrogen-alone (N=10, 739, 6. 8 years intervention) clinical trials until trial close-out (Spring 2005).

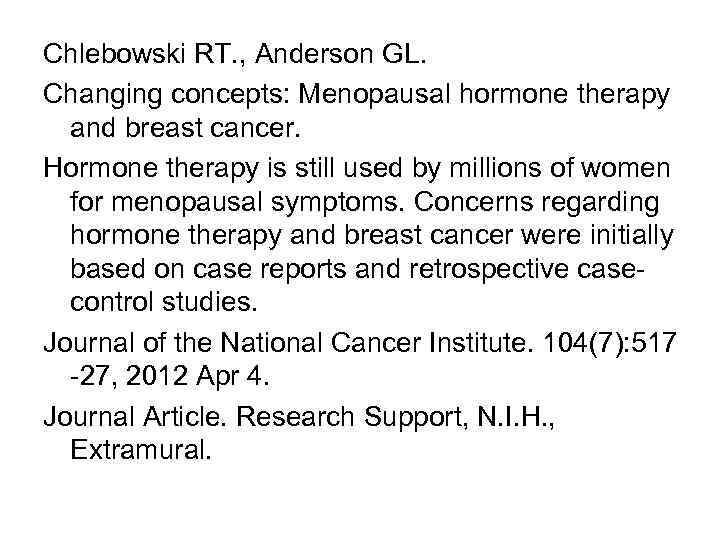

Chlebowski RT. , Anderson GL. Changing concepts: Menopausal hormone therapy and breast cancer. Hormone therapy is still used by millions of women for menopausal symptoms. Concerns regarding hormone therapy and breast cancer were initially based on case reports and retrospective casecontrol studies. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 104(7): 517 -27, 2012 Apr 4. Journal Article. Research Support, N. I. H. , Extramural.

Summary • Over 70 years, women have used hormone replacement therapy. Many studies received media exposure because it found that hormone replacement therapy increased the risk of breast cancer, but some ignored these statements. • The authors think that hormone replacement therapy has increased the risk of breast cancer.

UPDATE

THANK YOU FOR YOUR ATTENTION AND GOD BLESS YOUR COUNTRY !

10 Hormone Replacement Therapy and BC.ppt