BF_3.pptx

- Количество слайдов: 21

Behavioral Finance Utevskaya Marina Valerievna Ph. D Saint-Petersburg State University of Economics Associate Professor, Corporate Finance and Business Evaluation Department Director of International Master Program “Corporate Finance, Control and Risks”

PART III 2

Role of Investor Behavior • Bounded Rationality: “satisficing” behavior. Information processing limitations. Example: memory limitations. • Investor Sentiment: beliefs based on heuristics rather than Bayesian rationality. • Investors may react to “irrelevant information” and hence may trade on “noise” rather than information.

“Irrational” Behavior of Professional Money Managers • May choose a portfolio very close to the benchmark against which they are evaluated (for example: S&P 500 index). • Herding: may select stocks that other managers select to avoid “falling behind” and “looking bad”. • Window-dressing: add to the portfolio stocks that have done well in the recent past and sell stocks that have recently done poorly.

An Example • Initial endowment: $300. Consider a choice between: • a sure gain of $100 • a 50% chance to gain $200, a 50% chance to gain $0. • Initial endowment: $500. Consider a choice between: • a sure loss of $100 • a 50% chance to lose $200, a 50% chance to lose $0.

Reversal in Choice • Case 1: 72% chose option 1, 28% chose option 2. • Case 2: 36% chose option 1, 64% chose option 2. => A reversal in Choice • Problem framed as a gain: decision maker is risk averse. • Problem framed as a loss: decision maker is risk seeking.

Allais Paradox The Allais paradox is a choice problem designed by Maurice Allais (1953) to show an inconsistency of actual observed choices with the predictions of expected utility theory. The Allais paradox arises when comparing participants' choices in two different experiments, each of which consists of a choice between two gambles, A and B.

Kahneman Framework of “two minds” • to describe the way people make decisions • an “intuitive” mind: rapid judgments with great ease and with no conscious input • “reflective” mind: slow, analytical and requires conscious effort 8 Behavioral Finance, St. Petersburg, 2014

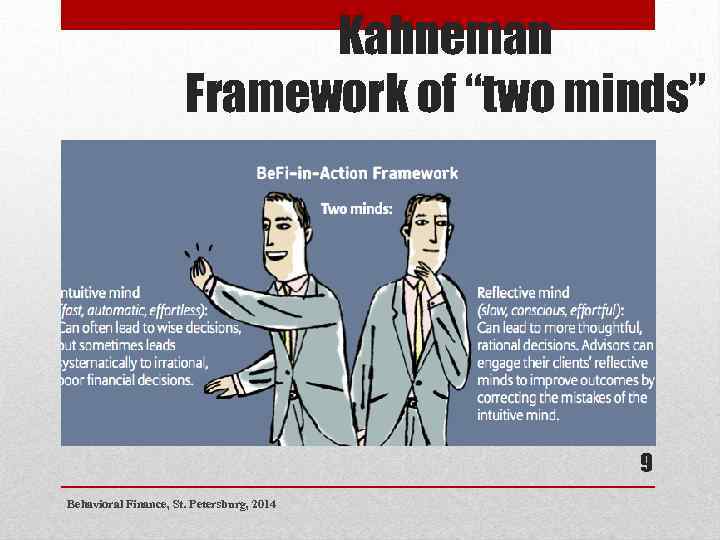

Kahneman Framework of “two minds” 9 Behavioral Finance, St. Petersburg, 2014

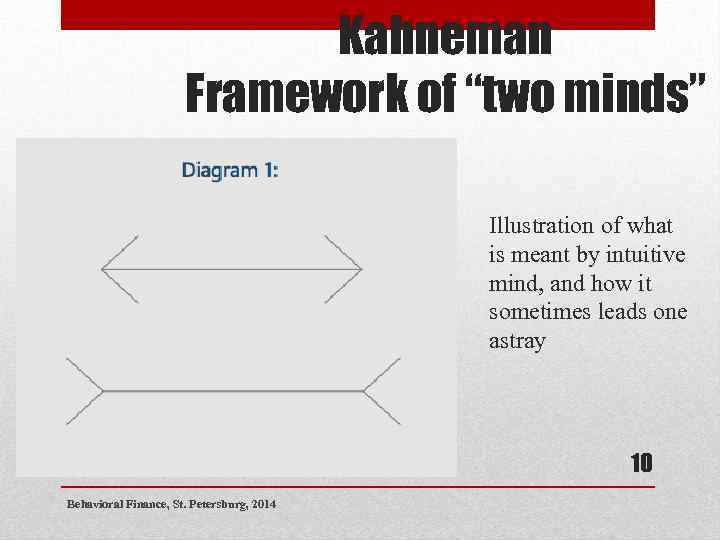

Kahneman Framework of “two minds” Illustration of what is meant by intuitive mind, and how it sometimes leads one astray 10 Behavioral Finance, St. Petersburg, 2014

Kahneman Framework of “two minds” • One of the insights that earned Kahneman the Nobel Prize 1 is that we humans are sometimes as susceptible to “cognitive illusions” as we are to optical illusions. • These illusions, also known as biases, result from the use of heuristics, or, more simply, mental shortcuts. • Kahneman’s discovery that under certain circumstances intuition can systematically lead to incorrect decisions and judgments changed psychologists’ understanding of decision making, and, ultimately, economists’, too. 11 Behavioral Finance, St. Petersburg, 2014

Kahneman Framework of “two minds” • Behavioral economics showed instead that we are not as logical as we might think, we do care about others, and we are not as disciplined as we would like to be. • It is not that people are irrational in the colloquial sense, but that by the nature of how our intuitive mind works we are susceptible to mental shortcuts that lead to erroneous decisions. • Our intuitive mind delivers the products of these mental shortcuts to us, and we accept them. It’s hard to help ourselves. 12 Behavioral Finance, St. Petersburg, 2014

Kahneman Framework of “two minds” • Loss aversion: • described by Prospect Theory (Kahneman and Tversky, 1979) • losses loom larger than equal-sized gains • loss aversion affects many of our decisions, including financial ones 13 Behavioral Finance, St. Petersburg, 2014

Kahneman Framework of “two minds” • EXAMPLE • Selling a losing stock is extremely unpalatable because it brings the reality of loss very much to mind. • People often sell winning stocks too soon because the act of selling a winning stock realizes a gain, and that gives us pleasure. • The mistake people are making here is one of mental accounting: instead of looking at their portfolio “as a whole” they look at each stock separately, and make decisions based on these separately perceived realities. 14 Behavioral Finance, St. Petersburg, 2014

Kahneman Framework of “two minds” • Loss aversion also makes people reluctant to make decisions for change because they focus on what they could lose more than on what they might gain. This is called “inertia, ” or the status quo bias (Samuelson and Zeckhauser, 1988). • Inertia is at play when people know they should be doing certain things that are in their best interests (saving for retirement, dieting to lose weight, or exercising), but find it hard to do today. 15 Behavioral Finance, St. Petersburg, 2014

Kahneman Framework of “two minds” • “We make intuitive judgments all the time, but it’s very hard for us to tell which ones are right and which ones are wrong” says Nicholas Barberis, a behavioral finance researcher at the Yale School of Management 16 Behavioral Finance, St. Petersburg, 2014

SMar. T • Richard Thaler • Save More Tomorrow. TM program (SMar. T) • An alarmingly large proportion of employees fail to participate in their company’s defined contribution retirement plan, often forgoing matching funds (free money) from employers • SMar. T effectively removes psychological obstacles to saving in the short and longer term, and helps people overcome them with very little effort on their part 17 Behavioral Finance, St. Petersburg, 2014

SMar. T There are four ingredients to the program: 1. Employees are invited to pre-commit to increase their saving rate in the future. Because of procrastination, most people find it easier to imagine doing the right things in the future, similar to our New Year resolutions to start exercising and dieting next year. 2. For those employees who do enroll, their first increase in savings coincides with a pay raise so that their take- home pay does not go down. This avoids triggering the mind’s hypersensitivity to loss, or loss aversion. 18 Behavioral Finance, St. Petersburg, 2014

SMar. T 3. The contribution rate continues to increase automati- cally with each successive pay raise until a previously agreed upon ceiling is reached. Here, inertia is working in people’s best interest, ensuring that people stay in the plan and the contribution rate increases. 4. Employees may opt out of the plan at any time they choose, though experience shows that people rarely do. This provision makes them more comfortable about joining in the first place. 19 Behavioral Finance, St. Petersburg, 2014

SMar. T • In the first case study of SMar. T, employees at a midsize manufacturing company increased their contribution to their retirement fund from 3. 5 percent to 13. 6 percent of salary over a three-and-a-half-year period (Thaler and Benartzi, 2004). This is a remarkable improvement in saving behavior. As a result, the program is now offered by more than half of the large employers in the United States, and a variant of the program was incorporated in the Pension Protection Act of 2006 (Hewitt, 2010). 20 Behavioral Finance, St. Petersburg, 2014

SMar. T • “The lesson of the experience with the SMar. T program, therefore, is general and powerful: the strategic application of a few key psychological principles can dramatically improve people’s financial decisions. ” • Financial advisors can take advantage of such insights in their own practices to help their clients make better decisions which, ultimately, should lead to better financial outcomes. 21 Behavioral Finance, St. Petersburg, 2014

BF_3.pptx