b6fcc0ec539a692dca6d6b7e2b0d29be.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 84

Automatic Refinement and Vacuity Detection for Symbolic Trajectory Evaluation Rachel Tzoref and Orna Grumberg CAV’ 06 1

Symbolic Trajectory Evaluation (STE) A powerful technique for hardware model checking that can handle • much larger hardware designs • relatively simple specification language Widely used in industry, e. g. , Intel, Freescale 2

STE is given • A circuit M • A specification A C, where – Antecedent A imposes constraints on M – Consequent C imposes requirements on M A and C are formulas in a restricted temporal logic (called TEL) 3

STE • Works on the gate-level representation of the circuit • Combines symbolic simulation and abstraction 4

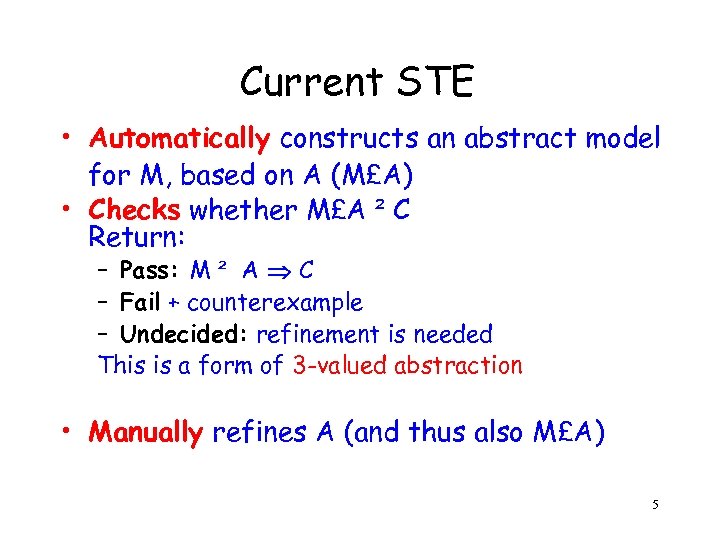

Current STE • Automatically constructs an abstract model for M, based on A (M£A) • Checks whether M£A ² C Return: – Pass: M ² A C – Fail + counterexample – Undecided: refinement is needed This is a form of 3 -valued abstraction • Manually refines A (and thus also M£A) 5

Agenda • • • Model checking Symbolic Trajectory Evaluation Basic Concepts Automatic Refinement for STE Vacuity in STE 6

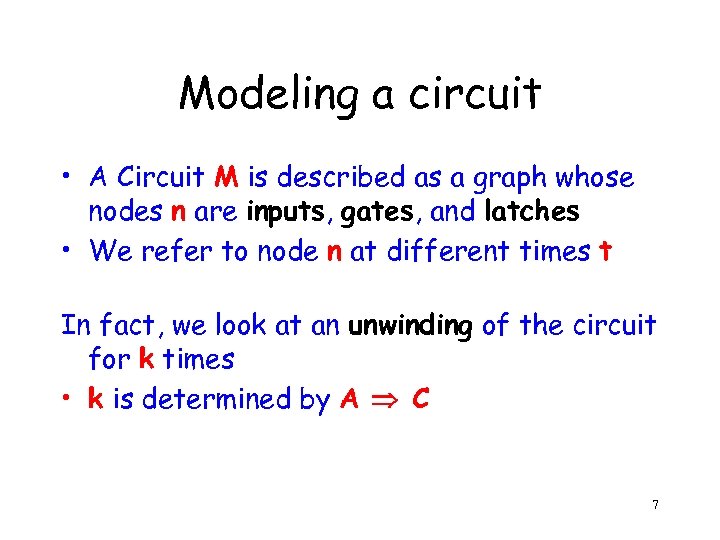

Modeling a circuit • A Circuit M is described as a graph whose nodes n are inputs, gates, and latches • We refer to node n at different times t In fact, we look at an unwinding of the circuit for k times • k is determined by A C 7

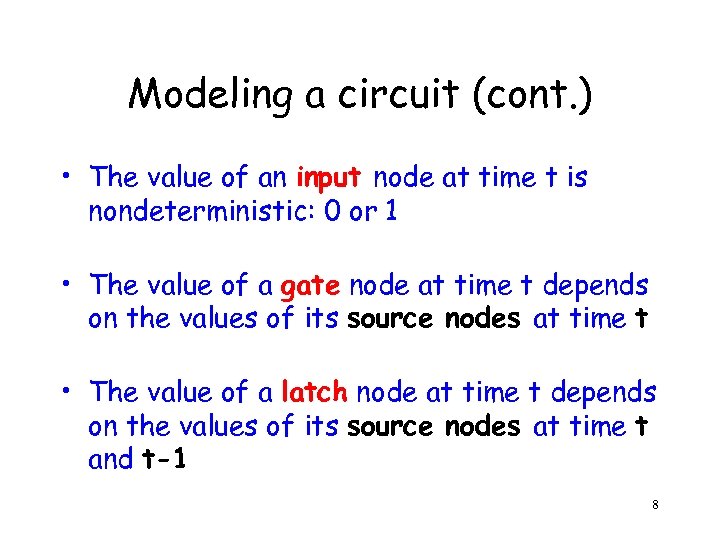

Modeling a circuit (cont. ) • The value of an input node at time t is nondeterministic: 0 or 1 • The value of a gate node at time t depends on the values of its source nodes at time t • The value of a latch node at time t depends on the values of its source nodes at time t and t-1 8

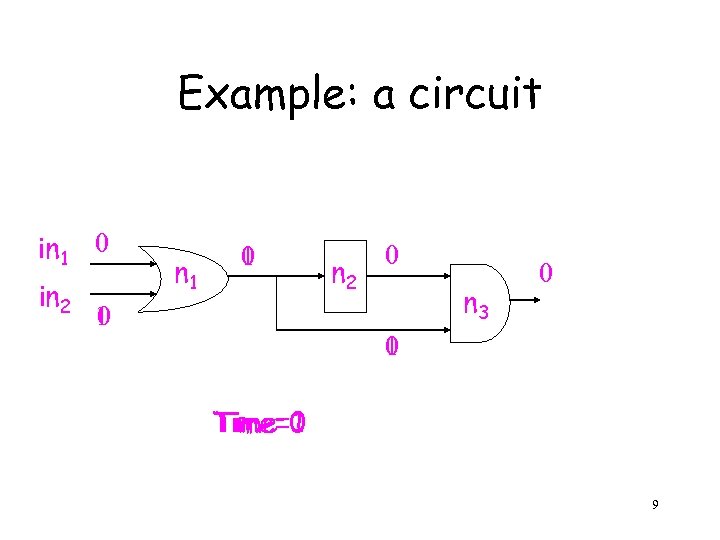

Example: a circuit in 1 0 in 2 n 1 0 1 1 0 n 2 0 n 3 0 0 1 Time=0 Time=1 9

Simulation Based Verification • Assigns values to the inputs of the model over time (as in the example) • Compares the output values to the expected ones according to the specification • Main drawback: the model is verified only for those specific combinations of inputs that were tested 10

Symbolic Simulation • Assigns the inputs of the model with Symbolic Variables over {0, 1} x x y y • Checks all possible combinations of inputs at once • Main drawback: representations of such Boolean expressions (e. g. by BDDs) are exponential in the number of inputs 11

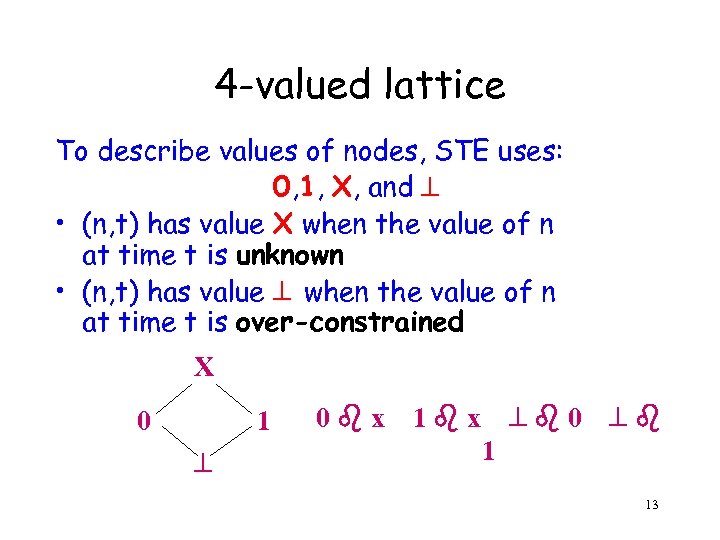

STE solution • Adds an “unknown’’ value X, in addition to 0, 1, and symbolic variables • Needs also an “over-constrained” value 12

4 -valued lattice To describe values of nodes, STE uses: 0, 1, X, and • (n, t) has value X when the value of n at time t is unknown • (n, t) has value when the value of n at time t is over-constrained X 0 1 0 x 0 1 x 1 13

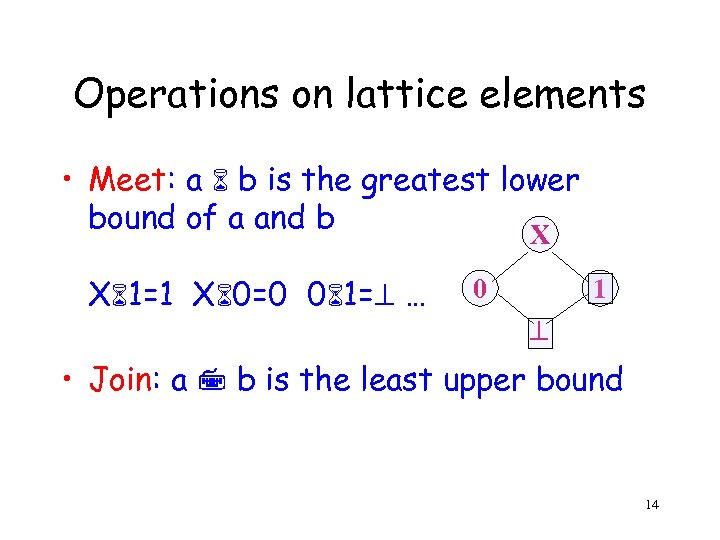

Operations on lattice elements • Meet: a b is the greatest lower bound of a and b X X 1=1 X 0=0 0 1= … 0 1 • Join: a b is the least upper bound 14

Lattice Semantics • X is used to obtain abstraction • is used to denote a contradiction between a circuit behavior and the constraints imposed by the antecedent A • Note: the values of concrete circuit node are only 0 and 1. 15

Quaternary operations • X 1 = 1 X 0 = X X X = X • X 1 = X X 0 = 0 X X = X • : X = X • Any Boolean expression containing has the value 16

Symbolic execution • STE combines abstraction with symbolic simulation to represent multiple executions at once • Given a set of symbolic variables V, the nodes of the circuit are mapped to symbolic expressions over V {0, 1, X, } 17

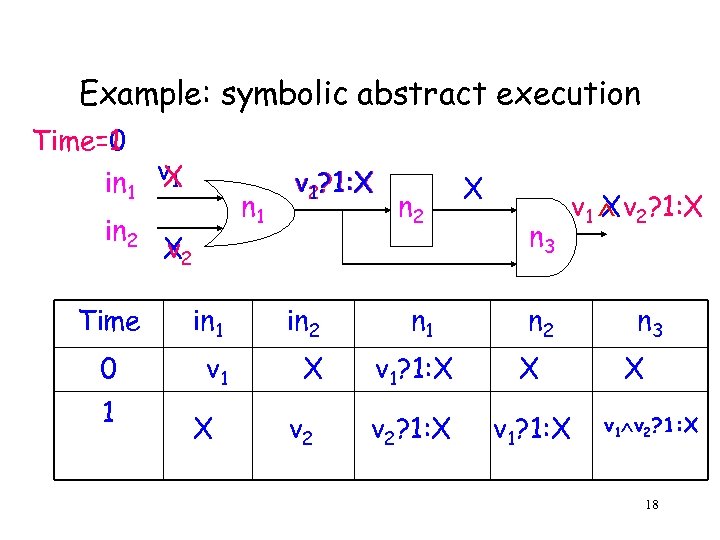

Example: symbolic abstract execution Time=1 Time=0 in 1 in 2 Time 0 1 v 1 X n 1 X 2 v v 2? 1: X 1 in 2 v 1 X X v 2 n 1 X n 3 n 2 v 1? 1: X X v 2? 1: X v 1 v 2? 1: X X n 3 X v 1 v 2? 1: X 18

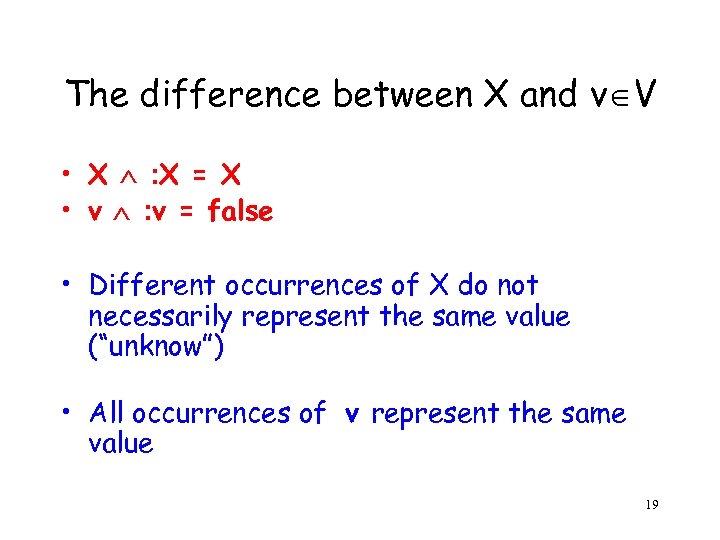

The difference between X and v V • X : X = X • v : v = false • Different occurrences of X do not necessarily represent the same value (“unknow”) • All occurrences of v represent the same value 19

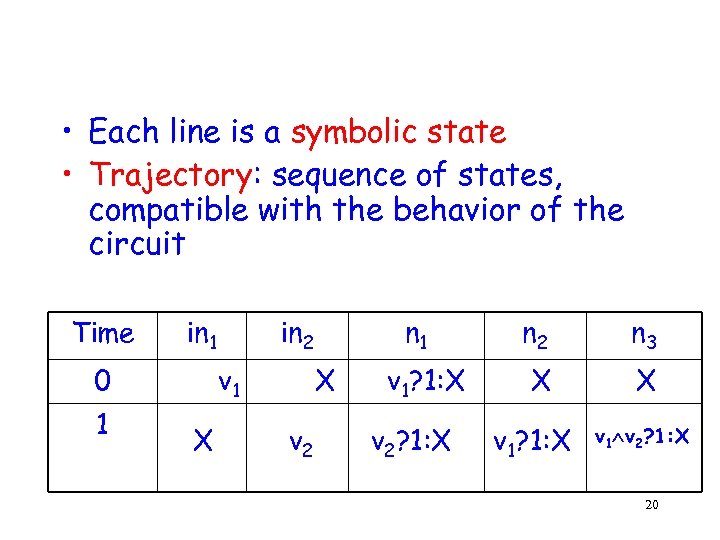

• Each line is a symbolic state • Trajectory: sequence of states, compatible with the behavior of the circuit Time in 1 0 1 in 2 v 1 X n 1 X v 2 v 1? 1: X v 2? 1: X n 2 n 3 X X v 1? 1: X v 1 v 2? 1: X 20

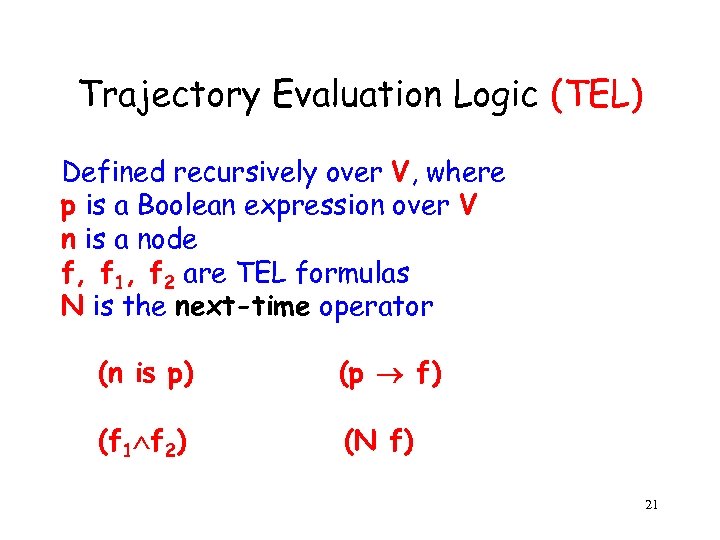

Trajectory Evaluation Logic (TEL) Defined recursively over V, where p is a Boolean expression over V n is a node f, f 1, f 2 are TEL formulas N is the next-time operator (n is p) (p f) (f 1 f 2) (N f) 21

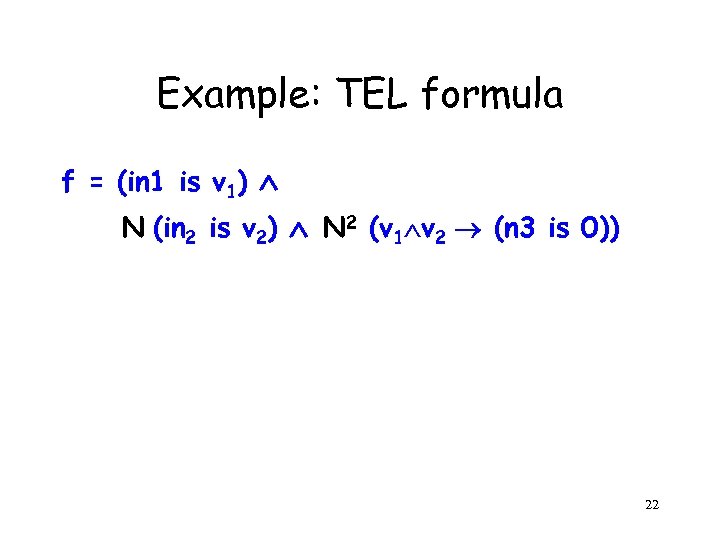

Example: TEL formula f = (in 1 is v 1) N (in 2 is v 2) N 2 (v 1 v 2 (n 3 is 0)) 22

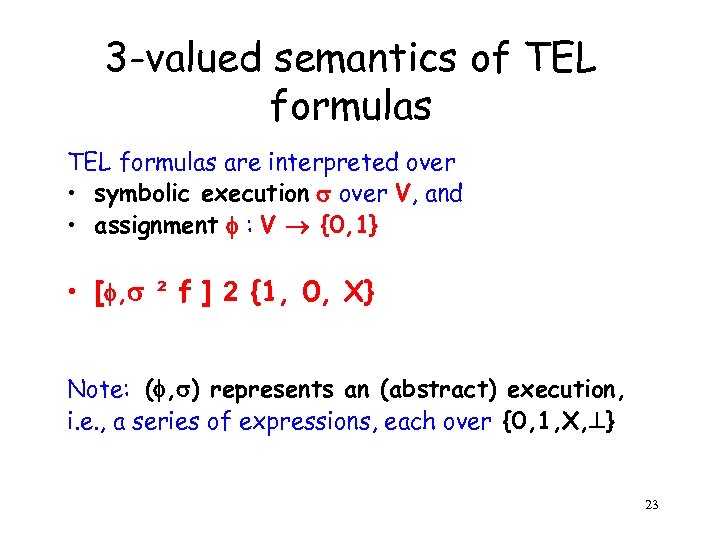

3 -valued semantics of TEL formulas are interpreted over • symbolic execution over V, and • assignment : V {0, 1} • [ , ² f ] 2 {1, 0, X} Note: ( , ) represents an (abstract) execution, i. e. , a series of expressions, each over {0, 1, X, } 23

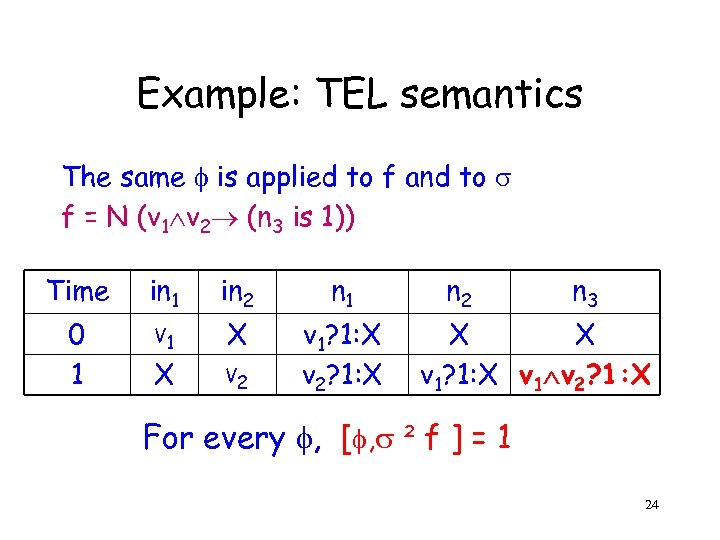

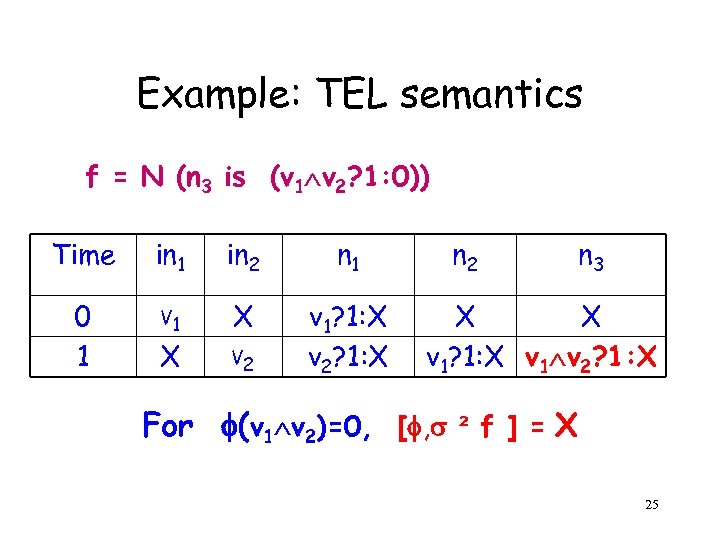

Example: TEL semantics The same is applied to f and to f = N (v 1 v 2 (n 3 is 1)) Time in 1 in 2 n 1 0 1 V 1 X v 1? 1: X v 2? 1: X X V 2 n 3 X X v 1? 1: X v 1 v 2? 1: X For every , [ , ² f ] = 1 24

Example: TEL semantics f = N (n 3 is (v 1 v 2? 1: 0)) Time in 1 in 2 n 1 0 1 V 1 X v 1? 1: X v 2? 1: X X V 2 n 3 X X v 1? 1: X v 1 v 2? 1: X For (v 1 v 2)=0, [ , ² f ] = X 25

![TEL Semantics • For every TEL formula f, [ , ² f] = iff TEL Semantics • For every TEL formula f, [ , ² f] = iff](https://present5.com/presentation/b6fcc0ec539a692dca6d6b7e2b0d29be/image-26.jpg)

TEL Semantics • For every TEL formula f, [ , ² f] = iff i, n: (i)(n) = A sequence that contains does not satisfy any formula 26

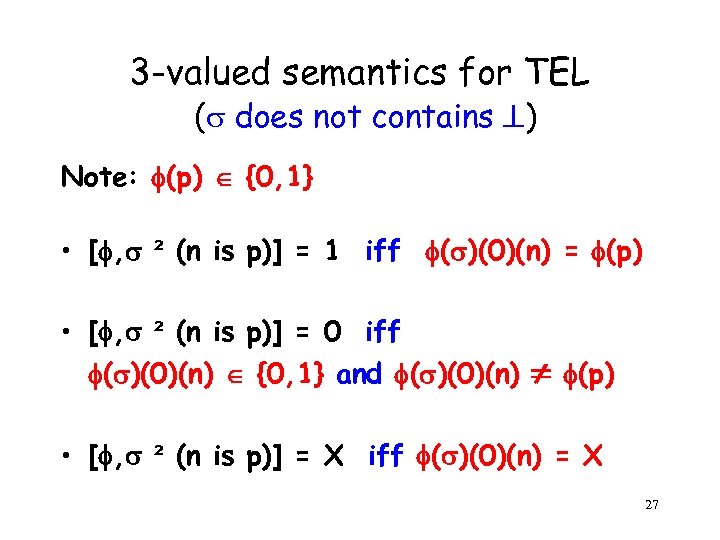

3 -valued semantics for TEL ( does not contains ) Note: (p) {0, 1} • [ , ² (n is p)] = 1 iff ( )(0)(n) = (p) • [ , ² (n is p)] = 0 iff ( )(0)(n) {0, 1} and ( )(0)(n) (p) • [ , ² (n is p)] = X iff ( )(0)(n) = X 27

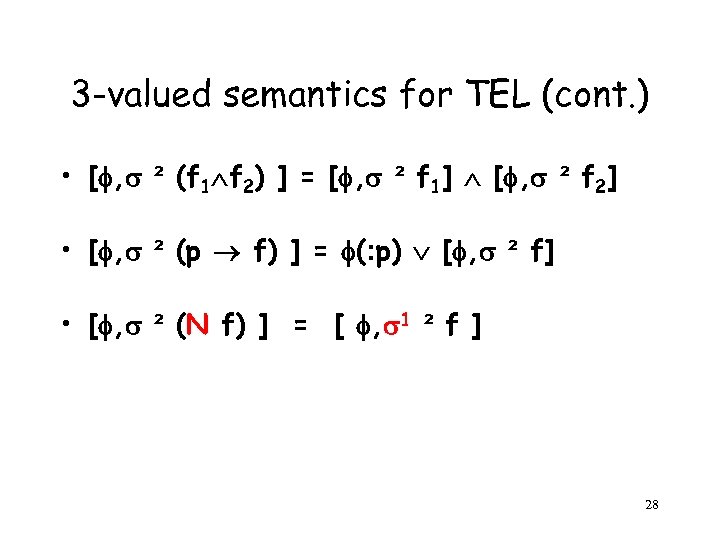

3 -valued semantics for TEL (cont. ) • [ , ² (f 1 f 2) ] = [ , ² f 1] [ , ² f 2] • [ , ² (p f) ] = (: p) [ , ² f] • [ , ² (N f) ] = [ , 1 ² f ] 28

![3 -valued semantics for TEL (cont. ) [ ² f ] = 0 iff 3 -valued semantics for TEL (cont. ) [ ² f ] = 0 iff](https://present5.com/presentation/b6fcc0ec539a692dca6d6b7e2b0d29be/image-29.jpg)

3 -valued semantics for TEL (cont. ) [ ² f ] = 0 iff for some , [ , ² f]=0 [ ² f ] = X iff for all , [ , ² f] 0 and for some , [ , ² f]=X 29

![3 -valued semantics for TEL (cont. ) [ ² f ] = 1 iff 3 -valued semantics for TEL (cont. ) [ ² f ] = 1 iff](https://present5.com/presentation/b6fcc0ec539a692dca6d6b7e2b0d29be/image-30.jpg)

3 -valued semantics for TEL (cont. ) [ ² f ] = 1 iff for all , [ , ² f] {0, X} and for some , [ , ² f]=1 [ ² f ] = iff for all , [ , ² f]= 30

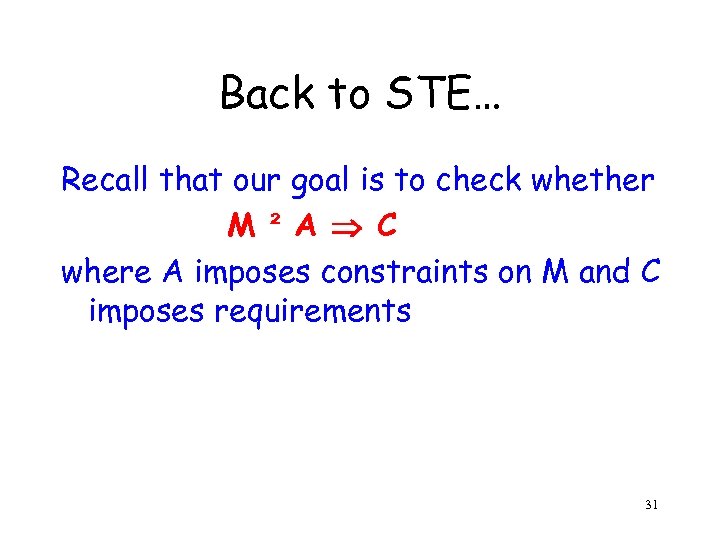

Back to STE… Recall that our goal is to check whether M ² A C where A imposes constraints on M and C imposes requirements 31

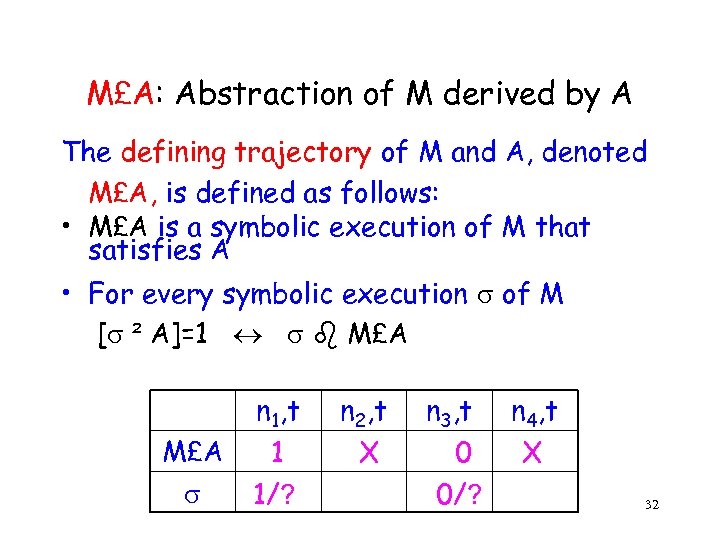

M£A: Abstraction of M derived by A The defining trajectory of M and A, denoted M£A, is defined as follows: • M£A is a symbolic execution of M that satisfies A • For every symbolic execution of M [ ² A]=1 M£A n 1, t 1 1/? n 2, t X n 3, t 0 0/? n 4, t X 32

![M£A (cont. ) • [Seger&Bryant] show that every circuit M and TEL formula f M£A (cont. ) • [Seger&Bryant] show that every circuit M and TEL formula f](https://present5.com/presentation/b6fcc0ec539a692dca6d6b7e2b0d29be/image-33.jpg)

M£A (cont. ) • [Seger&Bryant] show that every circuit M and TEL formula f has such M£f • M£A is the abstraction of all executions of M that satisfy A and therefore should also satisfy C • If M£A satisfies C then all executions that satisfy A also satisfy C 33

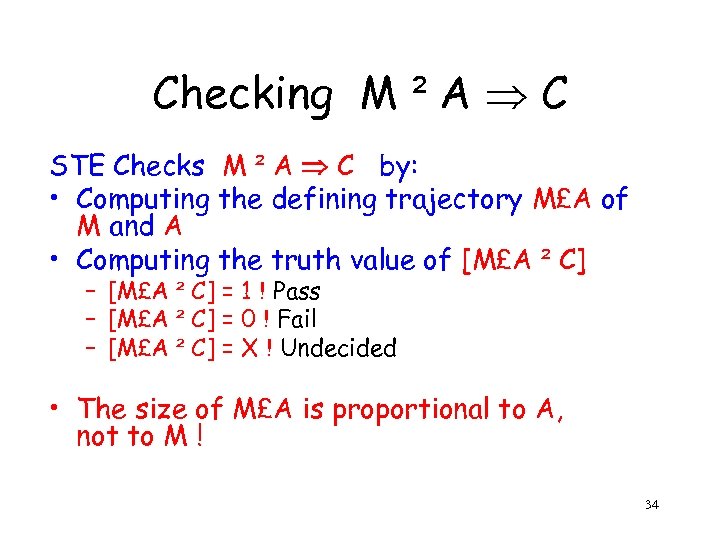

Checking M ² A C STE Checks M ² A C by: • Computing the defining trajectory M£A of M and A • Computing the truth value of [M£A ² C] – [M£A ² C] = 1 ! Pass – [M£A ² C] = 0 ! Fail – [M£A ² C] = X ! Undecided • The size of M£A is proportional to A, not to M ! 34

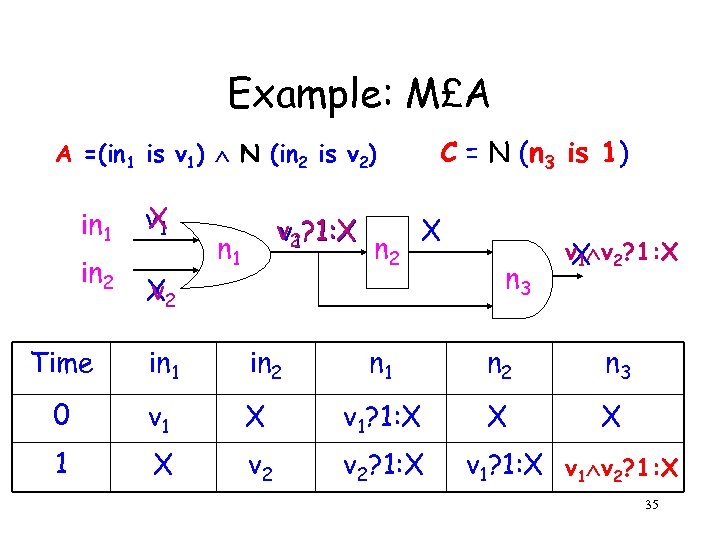

Example: M£A C = N (n 3 is 1) A =(in 1 is v 1) N (in 2 is v 2) in 1 in 2 v 1 X X 2 v v 2? 1: X v 1 n 1 Time in 1 in 2 0 v 1 1 X n 2 X n 3 v 1 v 2? 1: X X n 1 n 2 n 3 X v 1? 1: X X X v 2? 1: X v 1 v 2? 1: X 35

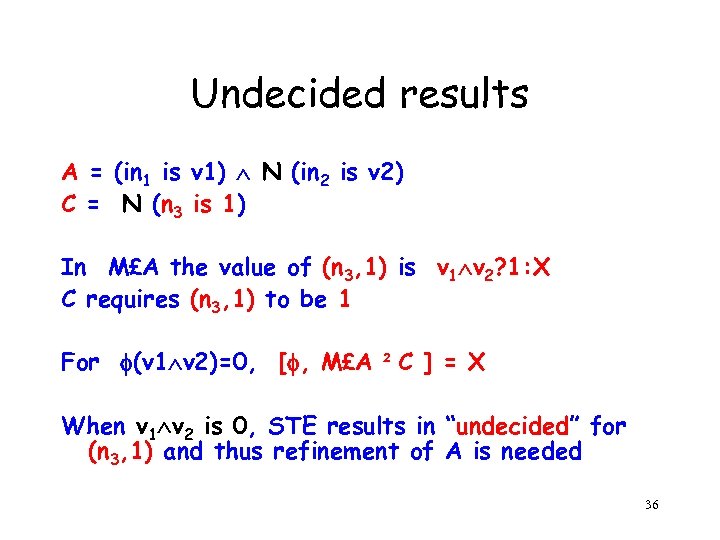

Undecided results A = (in 1 is v 1) N (in 2 is v 2) C = N (n 3 is 1) In M£A the value of (n 3, 1) is v 1 v 2? 1: X C requires (n 3, 1) to be 1 For (v 1 v 2)=0, [ , M£A ² C ] = X When v 1 v 2 is 0, STE results in “undecided” for (n 3, 1) and thus refinement of A is needed 36

Agenda • • • Model checking Symbolic Trajectory Evaluation Basic Concepts Automatic Refinement for STE Vacuity in STE 37

Important observation Refinement • should provide a more precise description of the circuit • without changing the specification given by the user Can be done by replacing X with new symbolic variables in A 38

Our Automatic Refinement Methodology • Choose for refinement a set Iref of inputs at specific times that do not appear in A • For each (n, t) Iref , vn, t is a fresh variable, not in V • The refined antecedent is: Anew = A (n, t) Iref Nt(n is vn, t) 39

Refinement (cont. ) Anew has the property that: M ² A C M ² Anew C Here we refer to the value of A C / Anew C over the concrete behaviors of M 40

Goal: Add a small number of constraints to A, keeping M£A relatively small, while eliminating as many undecided results as possible Remark: Eliminating only some of the undecided results may still reveal “fail”. For “pass”, all of them need to be eliminated 41

Choose a refinement goal We choose one refinement goal (root, tt) • A node that appears in the consequent C • Truth value is X • Has minimal t and depends on minimal number of inputs We will examine at once all executions in which (root, tt) is undecided 42

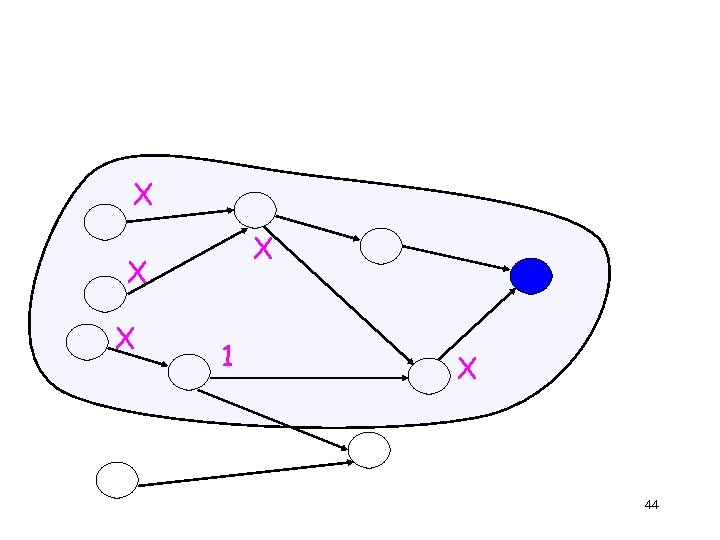

Choosing Iref for (root, tt) Naïve (syntactic) solution: Choose all (n, t) from which (root, tt) is reachable in the unwound graph of the circuit Will guarantee elimination of all undecided results for (root, tt) 43

X X 1 X 44

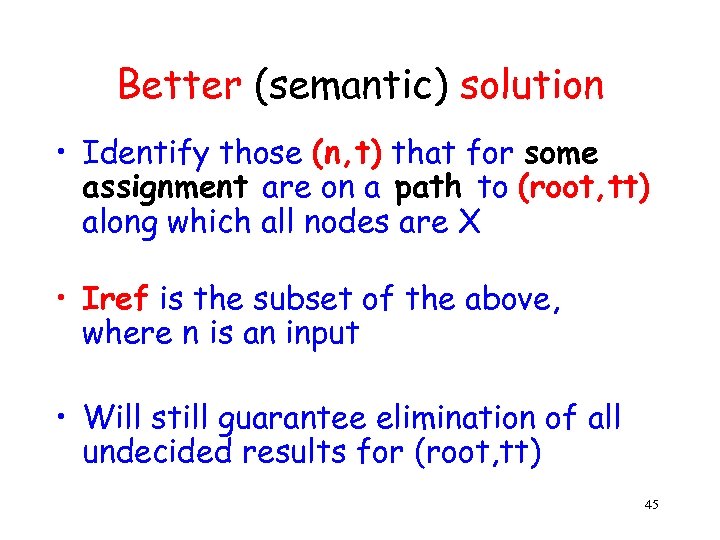

Better (semantic) solution • Identify those (n, t) that for some assignment are on a path to (root, tt) along which all nodes are X • Iref is the subset of the above, where n is an input • Will still guarantee elimination of all undecided results for (root, tt) 45

Heuristics for smaller Iref Choose a subset of Iref based on circuit topology and functionality, such as: • Prefer inputs that influence (root, tt) along several paths • Give priority to control nodes over data nodes • And more 46

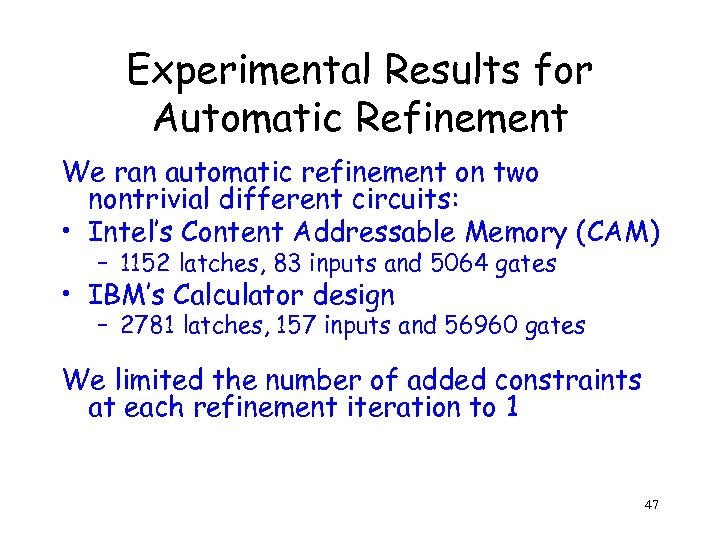

Experimental Results for Automatic Refinement We ran automatic refinement on two nontrivial different circuits: • Intel’s Content Addressable Memory (CAM) – 1152 latches, 83 inputs and 5064 gates • IBM’s Calculator design – 2781 latches, 157 inputs and 56960 gates We limited the number of added constraints at each refinement iteration to 1 47

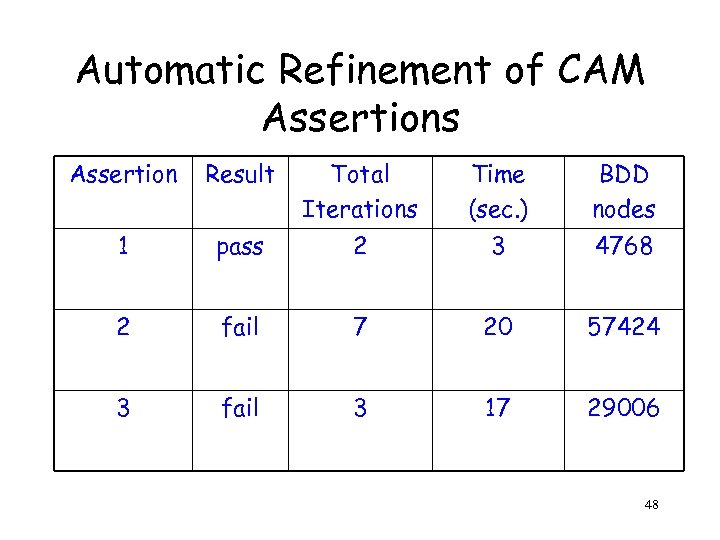

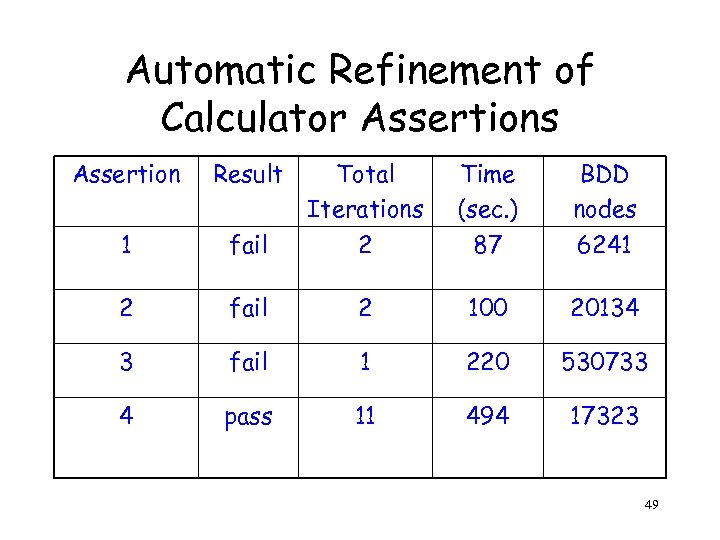

Automatic Refinement of CAM Assertions Assertion Result Total Iterations Time (sec. ) BDD nodes 1 pass 2 3 4768 2 fail 7 20 57424 3 fail 3 17 29006 48

Automatic Refinement of Calculator Assertions Assertion Result Total Iterations Time (sec. ) BDD nodes 1 fail 2 87 6241 2 fail 2 100 20134 3 fail 1 220 530733 4 pass 11 494 17323 49

Agenda • • • Model checking Symbolic Trajectory Evaluation Basic Concepts Automatic Refinement for STE Vacuity in STE 50

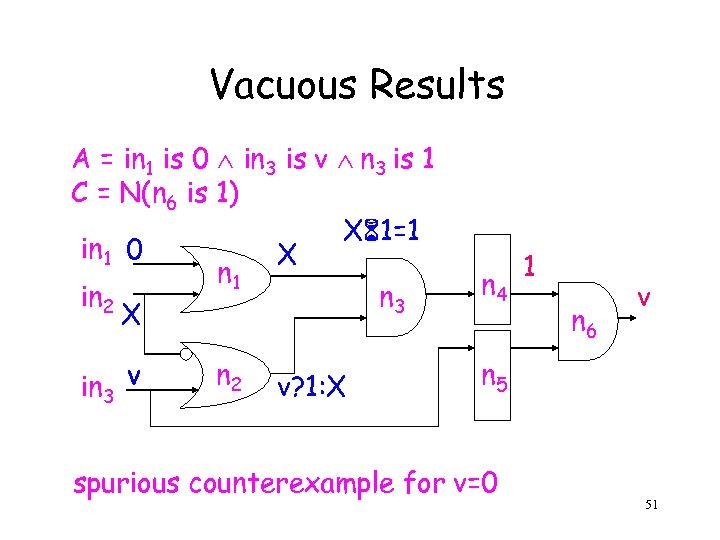

Vacuous Results A = in 1 is 0 in 3 is v n 3 is 1 C = N(n 6 is 1) X 1=1 in 1 0 X n 1 n 3 in 2 X in 3 v n 2 v? 1: X n 4 1 n 6 v n 5 spurious counterexample for v=0 51

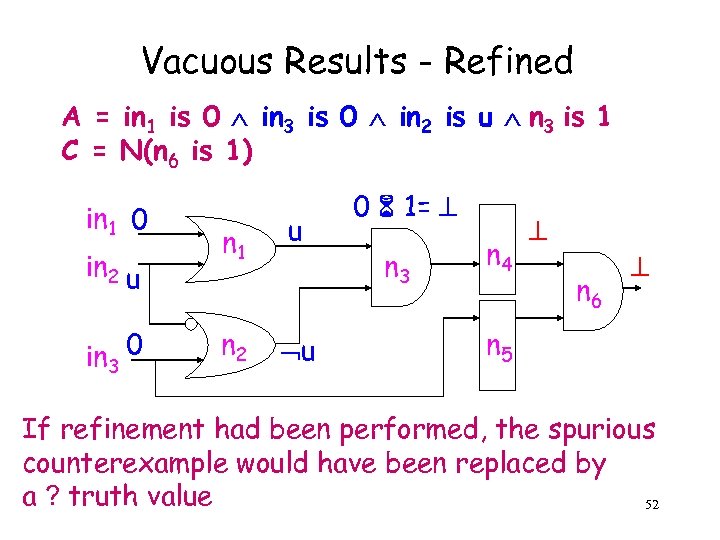

Vacuous Results - Refined A = in 1 is 0 in 3 is 0 in 2 is u n 3 is 1 C = N(n 6 is 1) in 1 0 in 2 u in 3 0 n 1 n 2 u u 0 1= n 3 n 4 n 6 n 5 If refinement had been performed, the spurious counterexample would have been replaced by a ? truth value 52

Antecedent failure • When Mx. A contains it is called antecedent failure • Antecedent failures can be viewed as explicit vacuity Our goal is to reveal hidden vacuity 53

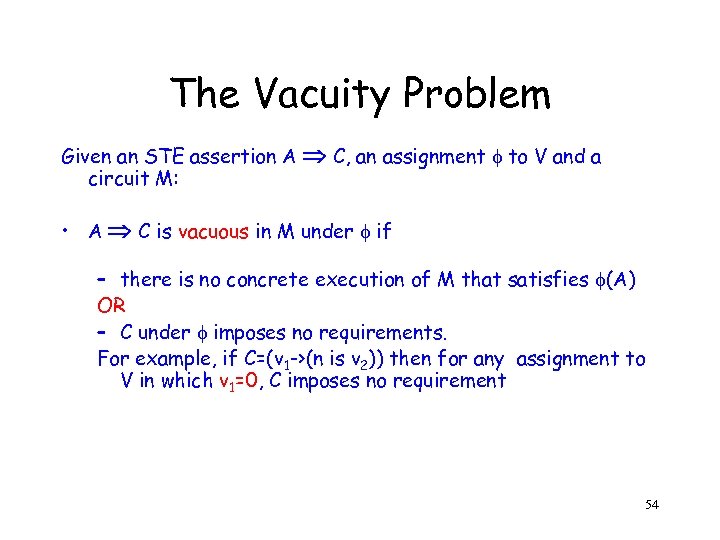

The Vacuity Problem Given an STE assertion A circuit M: C, an assignment to V and a • A C is vacuous in M under if – there is no concrete execution of M that satisfies (A) OR – C under imposes no requirements. For example, if C=(v 1 ->(n is v 2)) then for any assignment to V in which v 1=0, C imposes no requirement 54

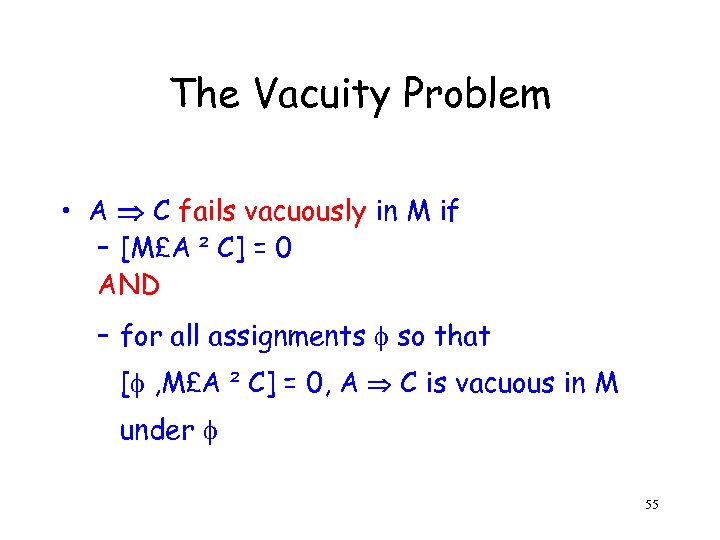

The Vacuity Problem • A C fails vacuously in M if – [M£A ² C] = 0 AND – for all assignments so that [ , M£A ² C] = 0, A C is vacuous in M under 55

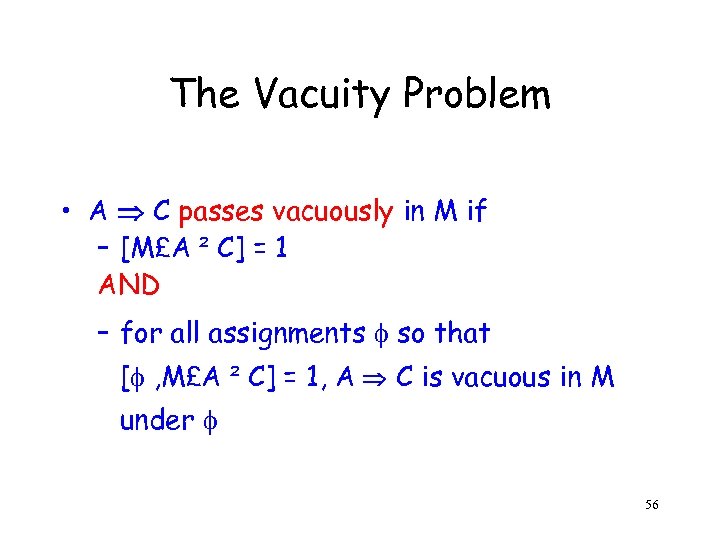

The Vacuity Problem • A C passes vacuously in M if – [M£A ² C] = 1 AND – for all assignments so that [ , M£A ² C] = 1, A C is vacuous in M under 56

Observation • Vacuity can only occur when A contains constraints on internal nodes (gates, latches) • Constraints on inputs can always be satisfied by M since input values are nondeterministic 57

Detecting (non-)vacuity Given a circuit M, an STE assertion A C and an STE result (either fail or pass), our purpose is to find an assignment to V and an execution of M that satisfies all the constraints in (A) 58

Detecting (non-)vacuity • In case of pass, should also impose requirements in C • In case of fail, the execution should constitute a counterexample 59

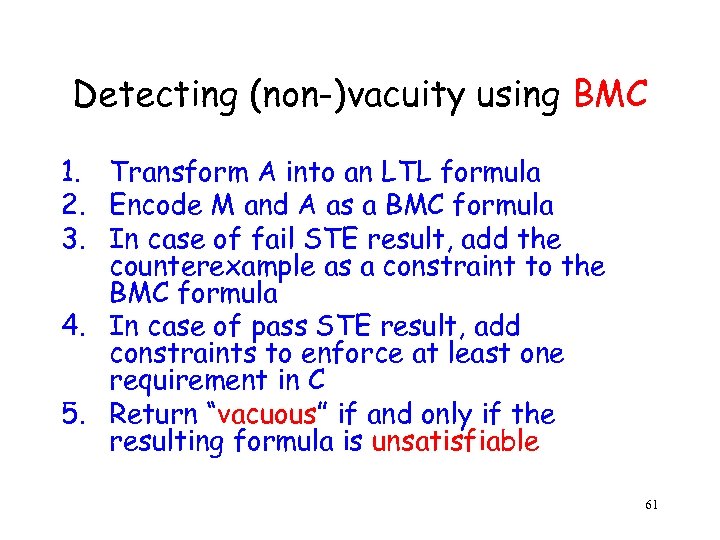

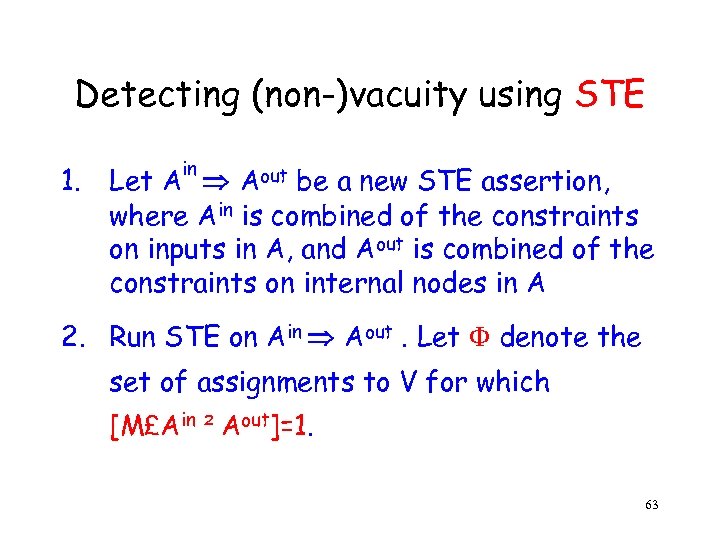

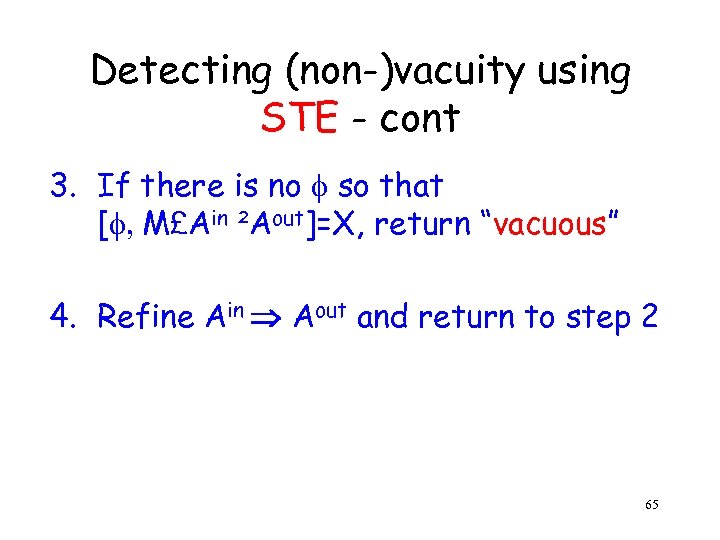

Detecting (non-)vacuity We developed two different algorithms for detecting vacuity / non-vacuity: • An algorithm that uses BMC and runs on the concrete circuit. • An algorithm that uses STE and automatic refinement. 60

Detecting (non-)vacuity using BMC 1. Transform A into an LTL formula 2. Encode M and A as a BMC formula 3. In case of fail STE result, add the counterexample as a constraint to the BMC formula 4. In case of pass STE result, add constraints to enforce at least one requirement in C 5. Return “vacuous” if and only if the resulting formula is unsatisfiable 61

Detecting (non-)vacuity using BMC Main Drawback: no abstraction is used We would like to detect vacuity while utilizing STE abstraction 62

Detecting (non-)vacuity using STE in 1. Let A Aout be a new STE assertion, where Ain is combined of the constraints on inputs in A, and Aout is combined of the constraints on internal nodes in A 2. Run STE on Ain Aout. Let denote the set of assignments to V for which [M£Ain ² Aout]=1. 63

![Detecting (non-)vacuity using STE cont 1. In case [M£A ² C]=1: If there is Detecting (non-)vacuity using STE cont 1. In case [M£A ² C]=1: If there is](https://present5.com/presentation/b6fcc0ec539a692dca6d6b7e2b0d29be/image-64.jpg)

Detecting (non-)vacuity using STE cont 1. In case [M£A ² C]=1: If there is an assignment in that imposes a requirement in C, return “pass non vacuously” 2. In case [M£A ² C]=0: If there exists 2 and ’ so that [ ’, M£A ² C]=0 and ( ’ is satisfiable) , return “fail non vacuously” 64

Detecting (non-)vacuity using STE - cont 3. If there is no so that [ , M£Ain ²Aout]=X, return “vacuous” 4. Refine Ain Aout and return to step 2 65

Conclusion and future work • We implemented our automated refinement and tested it on several circuits and specifications • Generalized STE (GSTE) extends STE by providing a specification language which is as expressive as -regular languages. A non-trivial future work is to suggest an automatic refinement for GSTE 66

Conclusion and future work • We defined the vacuity problem for STE and proposed methods for vacuity detection • Vacuity definition and detection is also required for GSTE 67

References Model Checking • Model checking E. Clarke, O. Grumberg, D. Peled, MIT Press, 1999. Abstraction-refinement in model checking • Counterexample-guided abstraction refinement for symbolic model checking E. Clarke, O. Grumberg, S. Jha, Y. Lu, H. Veith, JACM 50(5): 752 -794 (2003) Vacuity in model checking • Efficient detection of vacuity in temporal model checking I. Beer, S. Ben-David, C. Eisner, Y. Rodeh, Formal Methods in System Design, 18, 2001. 68

References STE • Formal verification by symbolic evaluation of partiallyordered trajectories C-J. Seger and R. Bryant, Formal Methods in System Design, 6(2), 1995. FORTE • An industrially effective environment formal hardware verification C-J Seger, R. Jones, J. O’Leary, T. Melham, M. Aagaard, C. Barrett, D. Syme, IEEE transactions on Computer-Aided Design of Integrated Circuits and Systems, 24(9), 2005 • FORTE http: //www. intel. com/software/products/opensource/tools 1 /verification 69

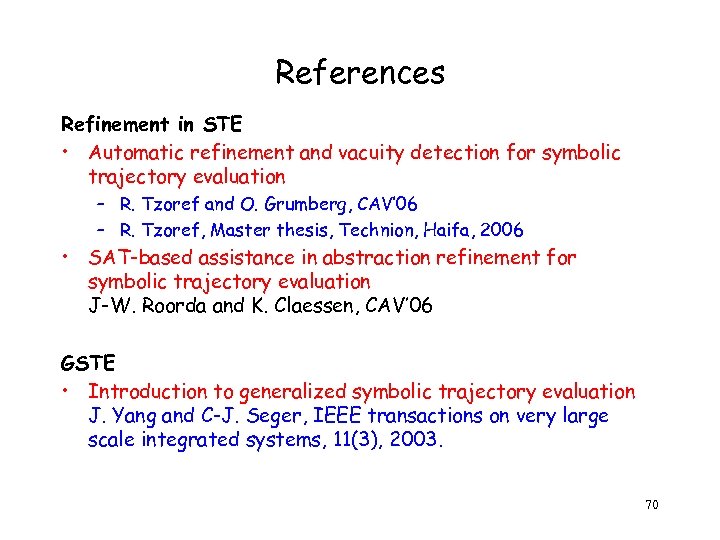

References Refinement in STE • Automatic refinement and vacuity detection for symbolic trajectory evaluation – R. Tzoref and O. Grumberg, CAV’ 06 – R. Tzoref, Master thesis, Technion, Haifa, 2006 • SAT-based assistance in abstraction refinement for symbolic trajectory evaluation J-W. Roorda and K. Claessen, CAV’ 06 GSTE • Introduction to generalized symbolic trajectory evaluation J. Yang and C-J. Seger, IEEE transactions on very large scale integrated systems, 11(3), 2003. 70

THE END 71

Model Checking § Emerging as an industrial standard tool for hardware design: Intel, IBM, Cadence, Synopsys, … § Recently applied successfully also for software verification: SPIN (Bell Labs), Java Path. Finder (NASA), Zing (Microsoft), Bandera (Kansas University), TVLA (Tel Aviv University), … 72

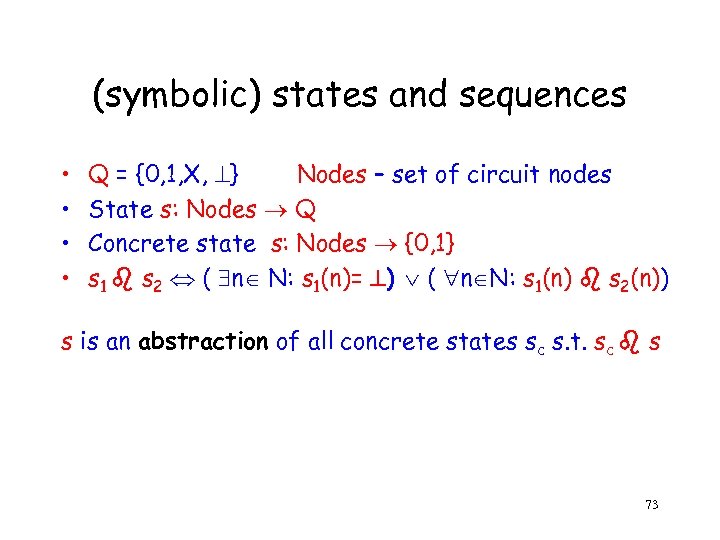

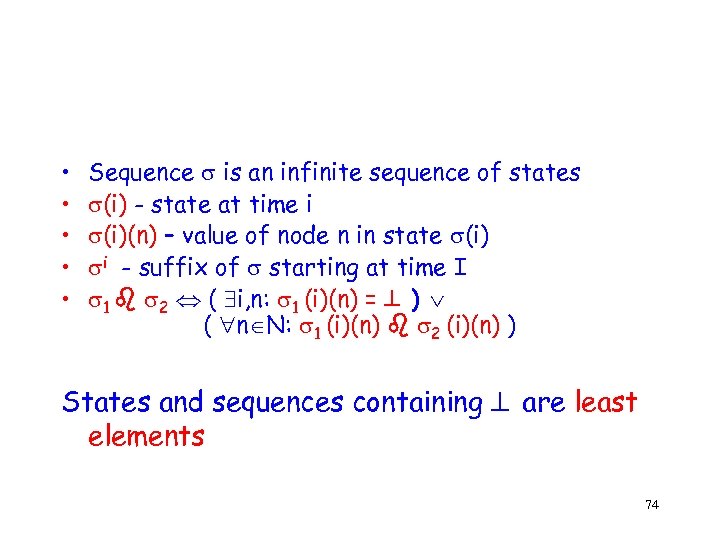

(symbolic) states and sequences • • Q = {0, 1, X, } Νodes – set of circuit nodes State s: Nodes Q Concrete state s: Nodes {0, 1} s 1 s 2 ( n N: s 1(n)= ) ( n N: s 1(n) s 2(n)) s is an abstraction of all concrete states sc s. t. sc s 73

• • • Sequence is an infinite sequence of states (i) - state at time i (i)(n) – value of node n in state (i) i - suffix of starting at time I 1 2 ( i, n: 1 (i)(n) = ) ( n N: 1 (i)(n) 2 (i)(n) ) States and sequences containing are least elements 74

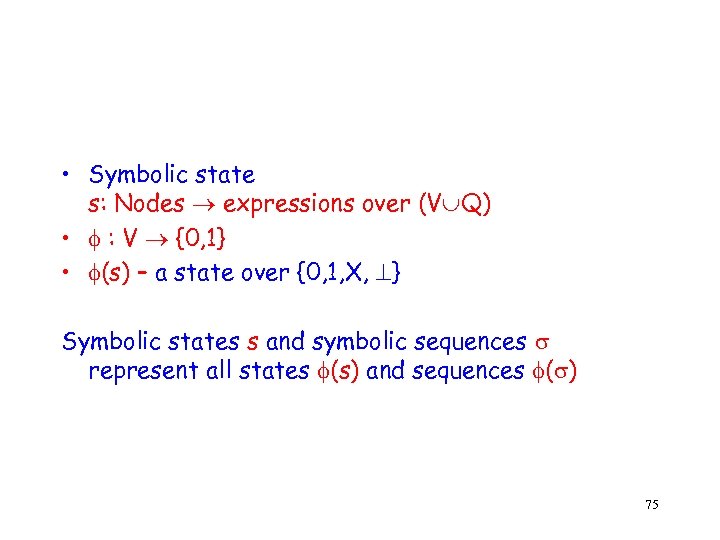

• Symbolic state s: Nodes expressions over (V Q) • : V {0, 1} • (s) – a state over {0, 1, X, } Symbolic states s and symbolic sequences represent all states (s) and sequences ( ) 75

![explanation [ ² f ] = iff for all , [ , ² f]= explanation [ ² f ] = iff for all , [ , ² f]=](https://present5.com/presentation/b6fcc0ec539a692dca6d6b7e2b0d29be/image-76.jpg)

explanation [ ² f ] = iff for all , [ , ² f]= • If for all assignments , ( , ) contains (a contradiction) then does not satisfy f. • Otherwise, we ignore those ( , ) which contain and decide the value of f based on the others 76

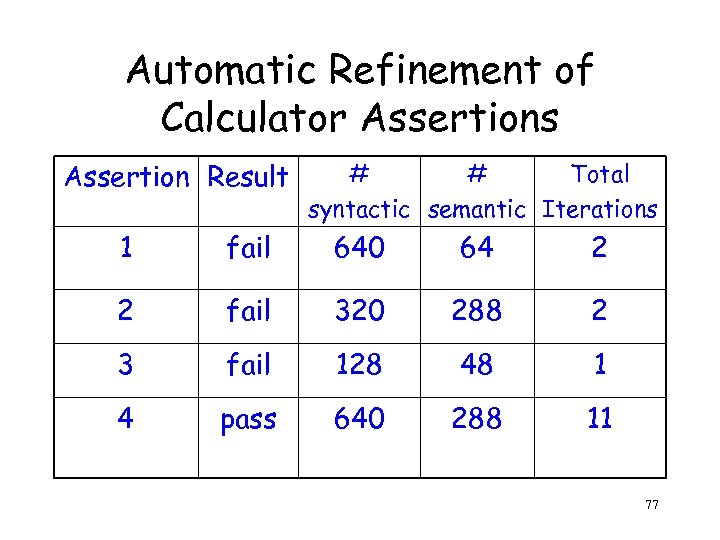

Automatic Refinement of Calculator Assertions Assertion Result # # Total syntactic semantic Iterations 1 fail 640 64 2 2 fail 320 288 2 3 fail 128 48 1 4 pass 640 288 11 77

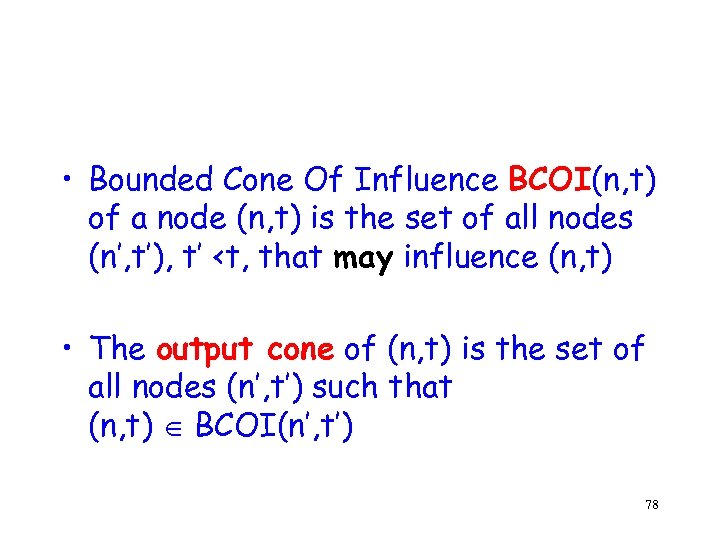

• Bounded Cone Of Influence BCOI(n, t) of a node (n, t) is the set of all nodes (n’, t’), t’ <t, that may influence (n, t) • The output cone of (n, t) is the set of all nodes (n’, t’) such that (n, t) BCOI(n’, t’) 78

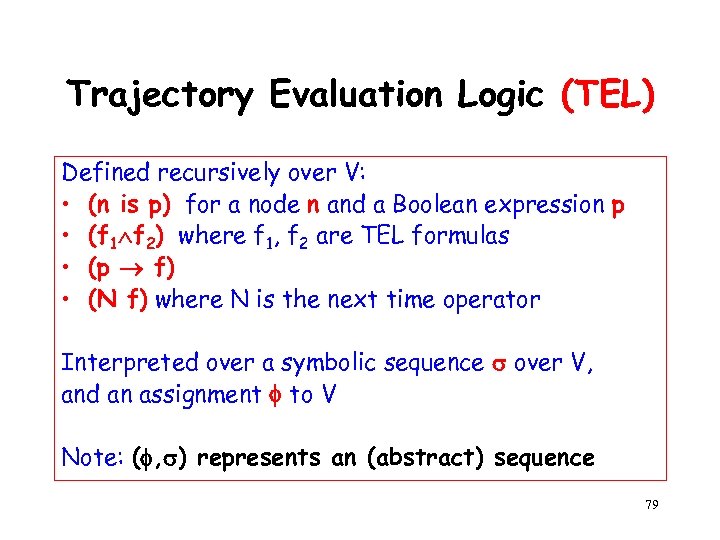

Trajectory Evaluation Logic (TEL) Defined recursively over V: • (n is p) for a node n and a Boolean expression p • (f 1 f 2) where f 1, f 2 are TEL formulas • (p f) • (N f) where N is the next time operator Interpreted over a symbolic sequence over V, and an assignment to V Note: ( , ) represents an (abstract) sequence 79

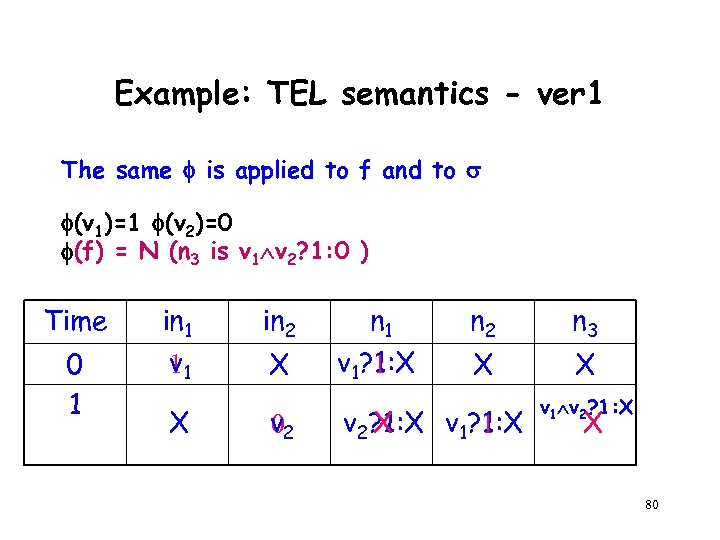

Example: TEL semantics - ver 1 The same is applied to f and to (v 1)=1 (v 2)=0 (f) = N (n 3 is v 1 v 2? 1: 0 ) Time 0 1 in 1 v 11 X in 2 X v 2 0 n 1 v 1? 1: X 1 n 2 n 3 X X v 2? 1: X v 1? 1: X X 1 v 2? 1: X X 80

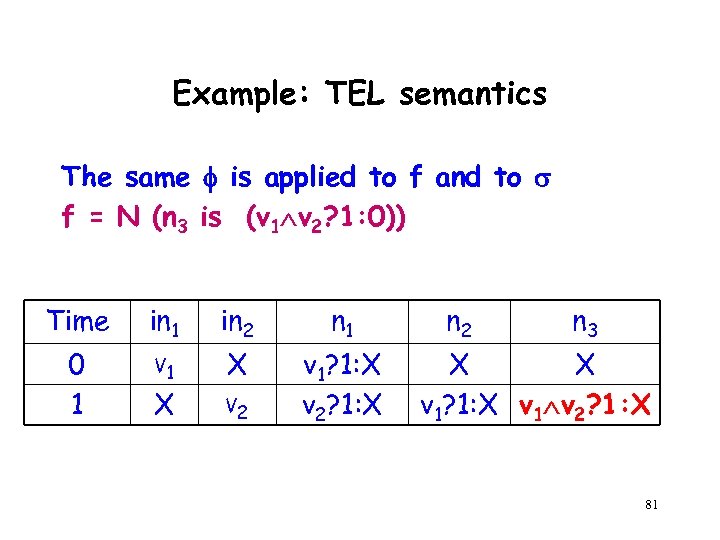

Example: TEL semantics The same is applied to f and to f = N (n 3 is (v 1 v 2? 1: 0)) Time in 1 in 2 n 1 0 1 V 1 X v 1? 1: X v 2? 1: X X V 2 n 3 X X v 1? 1: X v 1 v 2? 1: X 81

Agenda • • • Motivation Basic Concepts Symbolic Trajectory Evaluation Automatic Refinement for STE Vacuity in STE 82

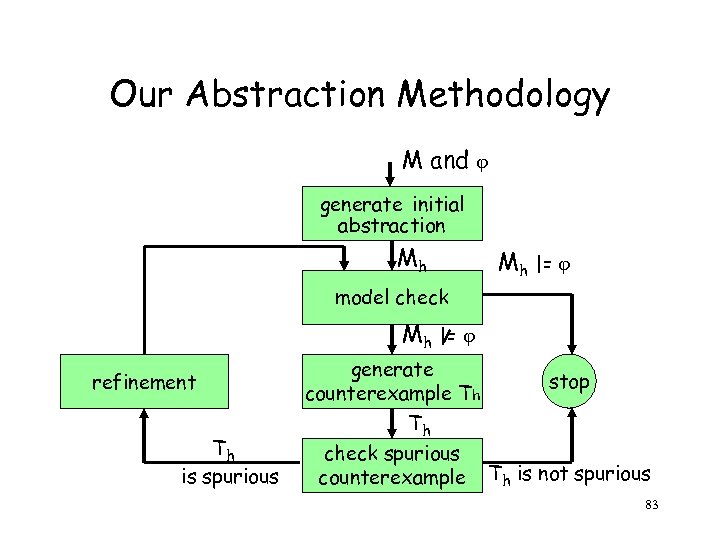

Our Abstraction Methodology M and generate initial abstraction Mh Mh |= model check Mh |= refinement Th is spurious generate counterexample Th Th check spurious counterexample stop Th is not spurious 83

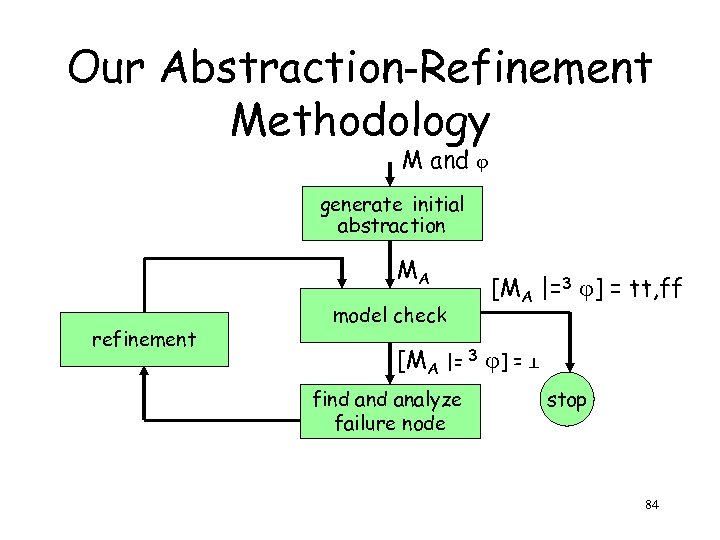

Our Abstraction-Refinement Methodology M and generate initial abstraction MA refinement model check [MA |=3 ] = tt, ff [MA |= 3 ] = ⊥ find analyze failure node stop 84

b6fcc0ec539a692dca6d6b7e2b0d29be.ppt